- 1School of Transnational Governance, European University Institute, Florence, Italy

- 2Gobierno y Análisis Político A.C., Xalapa, Mexico

Democracy is a central concern in the EU narrative toward Latin America; still, the allocation of funds does not follow this narrative closely, resulting in a chronic lack of support for local CSOs. The allocated funds face misappropriation by local authorities and the indirect support of low- and non-democratic regimes, reflected in the affected countries’ drop in indices that measure Social Progress and Democracy. This situation is further aggravated by prioritizing projects that reflect EU-centered agendas and skew the critical aid needed for democracy resilience building. As a response, we bring forward recommendations for the EU to bridge the gap between its democracy policy narrative and execution in Latin America, focusing on the particular needs of the region’s democratic agents.

Introduction

One of the EU’s main foreign policy pillars is promoting and supporting democracy worldwide. The active advocacy of EU diplomats in defense of democratic activists and movements is not only usual but also expected from a world power with very high democratic scores. However, this seldom translates into practical policies that restrain autocrats and strengthen democratic agents. On the contrary, many aid and investment frameworks are structured around strategic benefits and ideological tenets that often overlook countries’ political regimes and human rights records.

This is especially true for Latin America, a region that has endured a stark backsliding of its democracies and the consolidation of its autocratic regimes in recent years. This article analyzes the EU’s democracy policy towards Latin American countries through the concrete mechanisms of the Directorate General of International Partnerships (DG INTPA), namely the Neighborhood, Development, and International Cooperation Instrument’s Multiannual Indicative Programs (MIPs) and the Latin America Investment Facility for the region between 2010 and 2023, that are paramount of the EU’s external action.1 These policies are examined using the Narrative Policy Framework (Shanahan et al., 2018) to identify their characters and morals and quantitative analysis to account for the characteristics of democracy promotion.

The narrative behind the EU’s democracy policy

The EU’s democracy policy in Latin America suffers from inefficiencies throughout the entire process, including its design, execution, and evaluation. In each case, this is also true for the broader global Thematic Program on Human Rights and Democracy (TPHRD). Still, it is particularly grave in Latin America, given that the region’s autocracies remained largely unchallenged by the EU establishment (Chaguaceda and Povse, 2024).

At the operational level, the policy deviates from the goal of upholding human rights to introduce specific policies, such as “addressing the impact of environmental degradation and climate change” and “support to transitional justice multistakeholder processes” (DG INTPA, 2021, p. 2). These objectives, while arguably necessary, can be perceived in the region as dabbling with internal political issues that exceed the preservation of universally recognized human rights, which gives rise to allegations of the EU’s misuse of its democracy policies to advance its own ideological agenda within the more extensive field of democracy resilience-building (Kurki, 2011).

Moreover, the evocation of “strategic intergovernmental partners” such as the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, the International Criminal Court, and the Inter-American Commission and Court of Human Rights (DG INTPA, 2021, p. 3) add to the claim of the inefficacy of this policy (Thomas, 2012), as none of these institutions have effective jurisdiction over any country. Instead, applying their rulings and recommendations depends exclusively on the executive powers of the political leadership where it happens (Staden Von, 2016).

In the third place, the policy’s selected performance indicators collide with its express goal of “[closing] the gap between the solemn declarations and commitments and their concrete implementation on the ground” (DG INTPA, 2021, p. 1), as they include, for instance, accounting for the “number of state ratifications of international human rights instruments [and] national and sub-national laws and public policies” (DG INTPA, 2021, p. 32) in the context of low state capacity and the prevalence of dead letter laws in Latin America (Mazzuca and Munck, 2020). Similarly, it measures its policies’ success according to the number of recipients of its own aid, turning it into a process-oriented policy instead of an impact- or outcome-oriented one (Targeted Evaluations Can Help Policymakers Set Priorities, 2018).

At the narrative level, the policy clearly identifies its “hero” and “victim” characters (Shanahan et al., 2018) as the EU in the first role as a “responsible global actor for human rights and democracy” and the rest of the world as its target (DG INTPA, 2021, p. 1). However, clarity fades when analyzing the rest of the policy attributes, including identifying the problem, as there is not a single definition of what the EU views as democracy or human rights for its external policy; instead, it draws from the minimalistic goals set in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—and its resulting acquis—but also from the internal political accords that shaped the European Council’s Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy (European External Action Service, 2024).

In this sense, the vague scope of the policy opens the door to adding a swath of goals that collide with the recipients’ immediate needs, as there are also no indications regarding the rights hierarchy and the necessary prioritization of goals required for successful policy implementation. On top of this, the non-antagonistic nature of the policy narrative produces the lack of a clearly defined “villain” (Shanahan et al., 2018) to help orient concrete actions on the ground, which leaves open the door for cooperation with non-democratic actors.

Finally, the “moral” of the policy2 and its diverse priorities and action plans3 reflect the same vagueness in its language, avoiding negative terms that should reflect a “doomsday scenario” (Shanahan et al., 2018) in the case of the failure of its goals that asserts its critical importance in recipient countries. In any case, the policy’s positiveness is shadowed by its grim (but accurate) depiction4 of a global reality that is nonetheless not addressed as adamantly as it deserves.

The democracy policy in Latin America: where is the money?

The TPHRD, as the EU’s main external democracy policy, allocates between 15 and 17% of its budget to Latin America and the Caribbean. However, the broad allocation of money for the region does not follow specific priorities and, even less so, specific programs, making it difficult to trace the funds geographically. For instance, it does not allocate funds to Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) and Peace, Stability, and Conflict Prevention in Latin America. Nonetheless, there are specific organizations that guarantee an allocation. Among them are the National Human Rights Institutions (i.e., Ombudsman offices that are politically instated in Latin America), which include functionaries of dictatorships such as Nicaragua and Venezuela and semi-democratic countries with several political prisoners, such as Bolivia (Amnesty International, 2024). The Ombudsmen in these countries not only do not protect and promote human rights and democracy, but they actively support their regime’s measures against them (Ávila, 2020).

Beyond these cases where democracy funds have been allocated to overtly antidemocratic agents, the region’s MIPs show a deficient level of investment to achieve the policy’s goals and, simultaneously, an apparent inconsistency with each country’s level of democracy resilience. This is shown in Figure 1, which aggregates all the funds allocated to specific countries for the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) 2021–2027,5 besides the global allocation of the TPHRD.

Figure 1. Democracy score change in Latin American countries by EU democracy policy expenditure (2020–2023). Source: authors based on data from DG INTPA (2021) and Economist Intelligence Unit (2024). Only countries with confirmed allocations are included. The values for the region are calculated using the cap set in the TPHRD.

It can be inferred that the allocations for the MIPs on democracy prioritized countries with lower levels of democracy during the policy design in 2020. However, this argument disregards the fact that DG INTPA already had investments in these countries during previous MIPs.6 Therefore, it was aware of the limited effect of its policies on a region already enduring a generalized democratic backsliding (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2024). Moreover, most of these funds were allocated under the broader category7 of Democratic Governance, Security, and Migration (DG INTPA, 2020b), which entails the need for at least some involvement of the non- or low-democratic governments of some countries where it was implemented.

The policy inefficacies that these built-in deficiencies could bring about have been confirmed by the worsening democratic backsliding in almost all countries with some democracy funds allocated by the MIPs. However, this trend is not unique to the thematic policy but also occurs around the broader Latin American Investment Facility (LAIF) that takes on development investments, including human rights non-political fund allocations.

The map in Figure 2 shows the per-capita investments under these concepts in Latin America between 2010 and 2023, indicating a clear unbalance in favor of non- and low-democratic countries, with the especially extreme case of Nicaragua. In these cases, it cannot be argued that lower democracy levels drove the fund allocations to try and improve them, as these funds are dedicated mainly to the betterment of basic living conditions, subject in almost all cases to the control of national governments. In this sense, it can be argued that the then-Directorate General for International Cooperation and DG DEVCO Development actively prioritized investments in a country that lacked the rule of law and had little assurance about the correct control and usage of the allocated funds (Moncada Bellorin, 2020).

Figure 2. Map of per Capita EU LAIF Investments in Latin America 2010–2023 (in EUR). Source: authors based on data from Latin American and Caribbean Investment Facility [LACIF] (2024) and World Bank (2024). The multi-country project amounts are divided equally between the participating countries. Venezuela is omitted because it is subject to EU sanctions.

Moreover, this indicates that dictators’ strategy to victimize their populations to accede to international funds that supplant domestic or foreign investments fleeing due to the erosion of the rule of law is successful in manipulating the EU (Dukalskis, 2021). This is particularly preoccupying, as it entails that no matter how much a democracy backslides, EU international aid in the form of investments or fund allocations will keep pouring in.

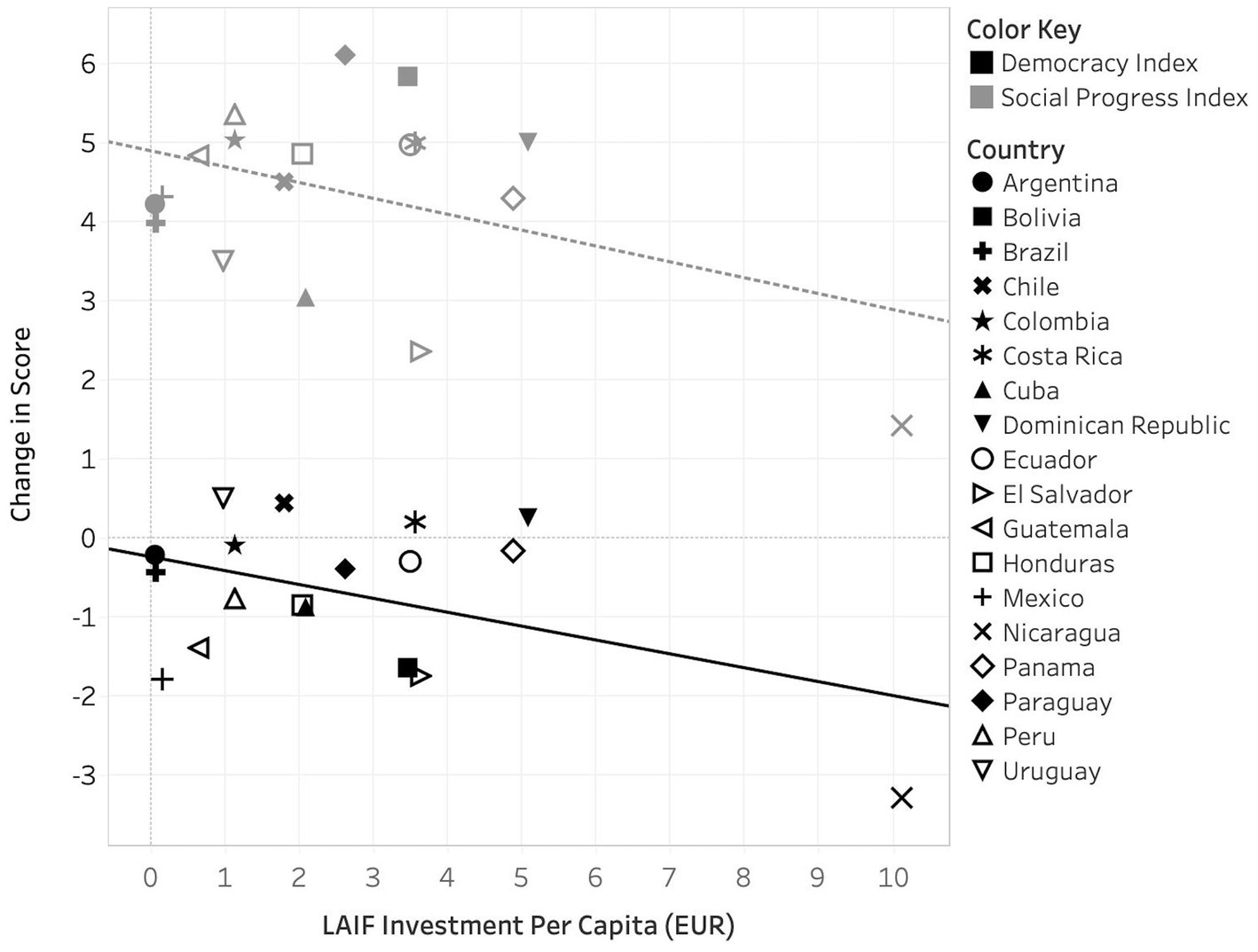

In the worst-case scenario, this incentivizes autocrats to worsen their populations’ living conditions. This is demonstrated in Figure 3, as not only is there a strong negative relationship8 between EU investments and the change in democracy levels, but also the evolution of social progress in the region; in this sense, after 14 years of investments the countries that received fewer investments from the EU are better off than those that were favored (Easterly, 2014).

Figure 3. Change in Democracy and Social Progress Scores in Latin American Countries by LACIF Investments (2010–2023). Source: authors based on data from LACIF, Economist Intelligence Unit (2024), Harmacek et al. (2024), and World Bank (2024). The multi-country project amounts are divided equally between the participating countries. Venezuela is omitted because it is subject to EU sanctions.

Aside from the Nicaraguan case—which only slid into an autocracy in recent years—the continuous flow of investments and aid into Cuba is perhaps the most perplexing case for EU external policy. Given its status as a non-sanctioned country by the European Commission,9 it has received a steady influx of development aid under the LAIF mechanism, but also under its own MIP that has allocated a record-breaking 91 million euros for the period 2021–2024 only to be used for “ecological transition [and] modernization of the economy” (DG INTPA, 2020a, p. 21). This puts the country in the most-favored position under the current MFF in Latin America measured per capita. However, its policy does not mention “authoritarianism,” “corruption,” or “humanitarian crisis” (DG INTPA, 2020a) for a country that is paramount to these concepts in Latin America (Amnesty International, 2024).

The contraposition of the narrative framework and the funds allocation aspects of the EU’s democracy policy in Latin America shows deep transversal flaws that require a comprehensive overhaul. In this sense, while the main goal to uphold democracy in the region is clear, there is a lack of accessory narrative that identifies the main challenges, especially the “villains” that contribute to democratic backsliding. This deficit in the early stages of the policy design later reflects on the ineffectiveness of the funds allocation that may go towards non-democratic actors.

Actionable recommendations

These circumstances are, however, an opportunity to revise the policy—if not also the global democracy policy and the broader Latin American policy. Addressing the issues set out in this article, we recommend:

1. To streamline the policy’s narrative, Latin American MIPs must be redesigned to prioritize democracy resilience building. As the DG INTPA democracy policy is detached from its geographically set MIPs, the first step in guaranteeing a framework where prioritizing goals can be achieved is aggregating the distinct policies of the Directorate-General into a single budget that can be more easily overseen. Within this budget, EU officials should allocate a more significant portion of funds to democracy-resilience-building projects at the national and regional levels that can guarantee the sustainability of the rest of the policies by institutional capacity and accountability building.

2. To make the policy narrative more less vague, there needs to be a clear identification of who the agents undermining democracy in Latin America are (“the villains”). This is set to be done by carrying out a system-level assessment of partners to identify illiberal or non-democratic influences in the region. This can be done by building a comprehensive and public standard to measure the democratic commitment of each partner, including essential caveats such as the affiliation with broadly recognized non-democratic state actors, the reported relationships with criminal para-political organizations (such as cartels), and the active involvement of vetted members of Latin American CSOs with undoubted democratic credentials.

3. To prevent non-democratic actors from having access to EU funds, the scope of the TPHRD must change to include only vetted CSOs to avoid any access to European funds by corrupt or non-democratic officials in Latin America. This goal can be achieved using the abovementioned standard to compose a database of trustworthy CSOs with the means (or potential) to implement projects in situ. Prioritizing non-state actors in funds allocation is critical to achieving a secure financial framework around democracy policy.

4. To avoid the stagnation of the longer-term MIPs, periodic reviews of fund allocation need to be held with the participation of vetted CSOs. Given the strong cooptation practices of non-democratic state actors in Latin America, a periodic review of the EU’s policy strategic partners must guarantee their commitment to democratic values. It is also necessary to assess the nature of the CSOs’ relationship with the state to prevent the spread of corruption and bad practices. Moreover, keeping an updated database of Latin American partners requires the periodic vetting of new CSOs, aiming to build as diverse a civil society environment as possible.

5. To limit non-democratic actors’ ability to undermine the policy’s implementation, institutional and diplomatic mechanisms must be established to support CSOs’ actions in non-democratic countries and guarantee their safety. Naturally, the policies’ scope cannot be reduced to only the redesign of fund allocation; on the contrary, a strong network of institutional support for the execution of funds and diplomatic pressure in situ and at international venues is vital for strengthening CSO’s capacity to influence the national political systems positively. This includes overtly speaking against non-democratic regimes without nuances and including the European private sector in policy design to secure and aid CSOs’ accounting and personal safety, among other urgent needs, given the bureaucratic, financial, and security-related challenges endured by activists in the region.

6. To facilitate the generation of more proactive policy analyses, data needs to be appropriately publicized, and the undermined trustability of the funds used under the various programs must be addressed. The current policy design system at DG INTPA precludes the input of civil society actors by reducing the availability and clarity of its policy process. It is necessary for a more assertive democratic policy to allow for the feedback of regional partners, as well as for the critical views from academia and other agents.

This list of recommendations is not exhaustive as to what is needed to reform the current EU democracy policy for Latin America. Still, its implementation is a sine qua non for further strengthening the efficacy of this policy.

Conclusion

As the main geopolitical bloc articulated around a founding democratic consensus, the European Union projects itself globally based on a confluence of interests and values. In its policy of cooperation towards Latin America—another mostly democratic region with growing authoritarian enclaves—European officials must attend to the demands for better planning, transparency, periodic evaluation, and good use of resources to provide timely support to their democratic counterparts in government and civil society. Otherwise, as we have pointed out in this text, the risk is the misuse of resources and their exploitation by regional authoritarian actors.

We have shown the paradox of a democratic Europe financing and legitimizing the allies of its enemies and the enemies of its allies, blind to its wrongdoings as perceived by the policy evaluations and evermore self-centered as indicated in its recent policies towards Latin America and the consequential fund allocations. We have laid out the core problems with the current gap between the main goal and execution of the EU’s democracy policy in its various forms towards the region and, in response to this grim outlook, offered actionable recommendations that can reduce the skewness of the funds’ allocations.

Supporting democracy in Latin America requires comprehensive strategies. On that path, possible actions are, among others, identifying activists, young leaders, officials, and academics to form networks of democratic reflection, solidarity, and advocacy; supporting persecuted scholars, intellectuals, and artists and denouncing their authoritarian counterparts before the international community; installing an agenda of coordination and cooperation with foundations and institutions, both governmental and non-governmental, as well as European and North American, so that they do not support militants of authoritarianism; and last but not least, confronting in public debates against illiberal discourses and ideologies to support and promote in the media fresh faces, recognizable and famous, that act as spokesmen for a democratic ideology. From this analysis and the alternatives presented, we hope to foster the EU’s officials’ strife towards efficacy when designing the future versions of the Bloc’s democracy policy towards Latin America.

Author contributions

MP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^These policies are selected due to their representativeness from the larger pool of Global Gateway (the EU’s external funding mechanism) projects and its predecessors, such as budget support and trust funds. The analysis does not include the international budgets of other dependencies in the European Commission (EC), such as the Directorate General for Education, Youth, Sport, and Culture, which manages the ERASMUS programs, and the Directorate General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations, due to data availability.

2. ^“To promote and protect human rights and fundamental freedoms, democracy and the rule of law worldwide," (DG INTPA, 2021, p. 1).

3. ^These invariable start with the verbs: “Enhance,” “facilitate,” “make strides,” “protect,” “empower,” “promote,” “strengthen,” “ensure,” “improve,” “safeguard,” and “develop” (DG INTPA, 2021, pp. 32–40).

4. ^“The crisis has further weakened overall respect for human rights and democracy, a trend to which no country is immune” (DG INTPA, 2021, p. 8).

5. ^In some cases, the sums refer to the partial allocation between 2021 and 2024; however, the sum allocated is close enough to the financial envelope for country allocations in the TPHRD (p. 31) to deduce that any new allocation after 2024 would have to be extra-budgetary.

6. ^The predecessor policy of the TPHRD was the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR) between 2014 and 2020. This article does not analyze it due to the lack of public information on its implementation in Latin America (Moran et al., 2017; DG DEVCO, 2017).

7. ^The EU-LAC Global Gateway Investment Agenda only features examples, so it is impossible to accurately indicate the allocated funds for concrete projects under the MIPs.

8. ^The correlation coefficients for the LAIF investments and the Democracy and Social Progress Indices scores are 0.44 and 0.42, respectively.

9. ^Data taken from https://www.sanctionsmap.eu/#/main.

References

Amnesty International. (2024). “Cuba: three years after the protests of 11–12 July 2021: authorities must release those unjustly imprisoned and repeal repressive laws.” Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/amr25/8266/2024/en/ (Accessed: 11 August 2024).

Ávila, M. (2020). Las ensordecedoras ausencias del Defensor del Pueblo. Available at: https://provea.org/opinion/las-ensordecedoras-ausencias-del-defensor-del-pueblo/ (Accessed 10, August 2024).

Chaguaceda, A., and Povse, M. (2024). ‘Democratic resilience facing autocratic influence in Latin America: recommendations on the EU’s potentialities and challenges,’ Forum 2000 [Preprint]. Available at: https://www.forum2000.cz/en/news/democratic-resilience-facing-autocratic-influence-in-latin-america-recommendatio (Accessed: 11 August 2024).

Dukalskis, A. (2021). Making the world safe for dictatorship. Oxford University Press. Available at: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=0v4hEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=international+investments+help+dictatorships&ots=VIh9e49teq&sig=PylHNTn5kkorX8iHGa00Gn_27U4 (Accessed: 11 August 2024).

Easterly, W. (2014). The tyranny of experts: Economists, dictators, and the forgotten rights of the poor. New York City, United States: Basic Books.

Economist Intelligence Unit. (2024). Democracy index 2023. Age of conflict. Available at: https://pages.eiu.com/rs/753-RIQ-438/images/Democracy-Index-2023-Final-report.pdf?version=0&mkt_tok=NzUzLVJJUS00MzgAAAGUPfFZR_AbBUPRsvTAVAomxryX8bG3KMtPFfzGjAbPQTSXbqIIPuVssap3cK52avTwqIvEKAKe2vXxFgL35l4CyCbgzmivnCLhvctMWKLRWdL0Fw (Accessed: 11 August 2024).

European Commission. Directorate General for International Cooperation and Development. (2017). Multi-Annual Action Program 2018–2020 for the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR) to be financed from the general budget of the European Union. Available at: https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/document/download/52ebe37f-b0c0-4fb3-9be2-f65c1763fe29_en?filename=eidhr-maap-implementing-decision-summary_en.pdf (Accessed: 11 August 2024).

European Commission. Directorate General for International Partnerships. (2020a). Multi-annual Indicative Program for the Republic of Cuba 2021–2027. Available at: https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/document/download/31833263-a4e0-4027-b987-83ac795275d9_en?filename=mip-2021-c2021-9130-cuba-annex_en.pdf (Accessed: 11 August 2024).

European Commission. Directorate General for International Partnerships. (2020b). The Americas and the Caribbean Regional Multiannual Indicative Program 2021–2027. Available at: https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/document/download/6a50dbc9-dec2-4a5b-8112-84bdffbc4684_en?filename=mip-2021-c2021-9356-americas-caribbean-annex_en.pdf&prefLang=es (Accessed: 11 August 2024).

European Commission. Directorate General for International Partnerships. (2021). ‘Thematic Program on Human Rights and Democracy Multi-Annual Indicative Programming 2021–2027’.

European External Action Service. (2024). EU Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy 2020–2024. Available at: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eu_action_plan_on_human_rights_and_democracy_2020-2024.pdf (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

Harmacek, J., Krylova, P., and Htitich, M. (2024). 2024 Social Progress Index. Social Progress Imperative. Available at: http://socialprogress.org (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

Kurki, M. (2011). Governmentality and EU democracy promotion: the European instrument for democracy and human rights and the construction of democratic civil societies. Int. Political Sociol. 5, 349–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-5687.2011.00139.x

Latin American and Caribbean Investment Facility. (2024). Project list. Available at: https://www.eulaif.eu/en/projects (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

Mazzuca, S. L., and Munck, G. L. (2020). A middle-quality institutional trap: democracy and state capacity in Latin America. Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/elements/politics-and-society-in-latin-america/5E56B8FA379251B944AFD8EEBD562759 (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

Moncada Bellorin, L. (2020). ‘Nicaragua: redes ilícitas y la reconfiguración cooptada del Estado’, Anhelos de un nuevo horizonte, ed. A. C. Ramos and U. López Baltodano and Bellorin, L. M. (San José de Costa Rica: Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales).

Moran, G., Devine, V., De Tollenaere, M., Visti, M., Rodríguez Ballesteros, L. P., Astre, A., et al. (2017). External Evaluation of the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights. Available at: https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/document/download/ecb668b4-3bfe-413a-834d-8ad23f2aa9c0_en (Accessed 10, August 2024).

Shanahan, E. A., Jones, M. D., Mcbeth, M. K., and Radaelli, C. M. (2018). ‘The narrative policy framework,’ in Theories of the policy process, ed C. M. Weible and P. A. Sabatier (Routledge), 173–213. Available at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429494284-6/narrative-policy-framework-elizabeth-shanahan-michael-jones-mark-mcbeth-claudio-radaelli (Accessed: 11 July 2024).

Staden Von, A. (2016). ‘Chapter 10: the political economy of the (non-)enforcement of international human rights pronouncements by states’, in The political economy of international law, ed. A. Fabbricotti (Elgaronline). Available at: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/edcoll/9781785364396/9781785364396.00020.xml (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

Targeted Evaluations Can Help Policymakers Set Priorities. (2018). Available at: http://pew.org/2tp9MUi (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

Thomas, D. C. (2012). Still punching below its weight? Coherence and effectiveness in European Union foreign policy. J. Common Market Stud. 50, 457–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5965.2011.02244.x

Keywords: EU-Latin America relations, democracy, policy narrative, fund allocation, democratic resilience, civil society organizations, non-democratic state actors

Citation: Povse M and Chaguaceda Noriega A (2024) The EU democracy policy in Latin America: narrative and funding. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1488950. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1488950

Edited by:

Vladimir Rouvinski, ICESI University, ColombiaReviewed by:

Cintia Quiliconi, Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences Headquarters Ecuador, EcuadorArie Marcelo Kacowicz, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel

Copyright © 2024 Povse and Chaguaceda Noriega. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Max Povse, bWF4LnBvdnNlQGV1aS5ldQ==; Armando Chaguaceda Noriega, aW52ZXN0aWdhY2lvbkBnb2JpZXJub3lhbmFsaXNpc3BvbGl0aWNvLm9yZw==

Max Povse

Max Povse Armando Chaguaceda Noriega

Armando Chaguaceda Noriega