- 1Department of Social and Educational Policy, University of Peloponnese, Corinth, Greece

- 2Health Policy Institute, Athens, Greece

This study investigates Greek citizens’ attitudes toward the current healthcare system and their perspectives on healthcare reforms. Additionally, it explores the role of both endogenous and exogenous crises in accelerating the implementation of long-overdue structural reforms that might otherwise be challenging to achieve. To this end, the research examines the level of trust in institutions and the implementation of healthcare reforms following the fiscal crisis and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings reveal that while most Greek citizens recognize the necessity of structural reforms within the healthcare system, approximately half of the population views these changes negatively. The primary obstacles to successful reform are identified as a lack of political will and resistance from specific interest groups. The contradiction within Greek society concerning healthcare reform is largely driven by low levels of institutional trust and social capital. Although there is a clear need for radical reforms, public perception tends to be negative when these changes are framed within political discourse. However, when reforms align with the actual needs of society, citizens’ trust in institutions increases, thereby improving the likelihood of successful policy implementation. This underscores the critical role of institutional trust in facilitating significant healthcare policy transformations.

1 Introduction

In the complex and evolving healthcare landscape, the term “permacrisis” has emerged to encapsulate persistent challenges and systemic issues that extend beyond acute, short-lived disruptions. Unlike traditional crises, permacrisis in healthcare signifies a prolonged state of instability where inefficiencies, inequities, and inadequacies persist, undermining the sector’s ability to meet the evolving needs of patients and communities. This state of continuous disruption reflects the confluence of economic, social, technological, and political factors, which intertwine to create a complex web of challenges within healthcare systems (Agunsoye and Fotopoulou, 2023). Recent global events, such as the 2008 economic crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, are prime examples of permacrises that have significantly reshaped healthcare systems worldwide.

Permacrisis brings attention to the danger of “public health catastrophism,” where constant crisis management can overshadow the need for long-term systemic reforms (Chiolero, 2023). This state of prolonged crisis demands a paradigm shift. Instead of focusing solely on emergency responses, the sector must evolve toward resilient, adaptable, and sustainable healthcare systems. Healthcare systems are designed to meet the needs of citizens by improving their health, responding to reasonable expectations, and equitably collecting funds (World Health Organization, 2000). The continuous pressures of permacrisis in the past years have exposed the vulnerabilities of healthcare systems and highlighted the urgent need for reform that addresses both current and future challenges.

The notion of permacrisis has become increasingly relevant on a global scale, as healthcare systems in many countries have struggled to adapt to continuous disruptions in supply chains, workforce shortages, and diagnostic infrastructure (Grammatopoulos et al., 2023). Similarly, Burau et al. (2024) emphasize that post-pandemic healthcare reforms in Europe must focus on strengthening workforce capacities, which have been severely tested during the COVID-19 pandemic. The challenges presented by permacrisis demand reforms that go beyond immediate responses and build systems capable of withstanding future shocks. In addition to these global concerns, technological advances and climate change pose significant challenges to healthcare systems, which must adapt to address more frequent pandemics and the rise of climate-related diseases (Haines and Ebi, 2019).

In Greece, citizens have long sought structural changes within the healthcare system, but entrenched interest groups—through established clientelistic relationships—have played a decisive role in obstructing meaningful reform (Kouris et al., 2007; Skalkos, 2018). The prevalence of rent-seeking behaviors in Greek politics further exacerbated this issue, contributing to long-standing political inertia in healthcare reforms not necessarily during times of acute crises (Featherstone and Papadimitriou, 2008). However, significant crises in Greece, such as the 2011 economic recession and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, presented opportunities for reform by creating conditions in which politically unpopular yet necessary changes were implemented. These reforms, which under normal circumstances would have faced significant resistance from vested interest groups, were expedited due to the pressure of systemic collapse. Thus, political resistance to reform was subdued, allowing for the introduction of crucial but previously unachievable policies (Papadonikolaki and Souliotis, 2023).

Our study draws upon several key theoretical perspectives that explain the complexities of healthcare reform in Greece during prolonged crisis, or permacrisis. According to Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework (Kingdon, 1995), crises align problem, policy, and political streams, creating “windows of opportunity” for previously stalled reforms. Similarly, punctuated equilibrium theory suggests that external shocks disrupt periods of policy stability, triggering bursts of reform, as seen in Greece’s response to both the 2011 economic crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993).

Furthermore, institutional trust is vital for the success of reforms. Putnam’s social capital theory emphasizes that low levels of trust in institutions-evident in Greece-undermine public support for reforms, even when these are necessary (Putnam et al., 1993; Putnam, 1995). Lastly, clientelism and rent-seeking behaviors explain the resistance from vested interests, which obstruct healthcare reforms due to entrenched clientelistic relationships (Olson, 1982; Robinson and Acemoglu, 2012). These theoretical insights provide a framework for understanding the challenges and opportunities of healthcare reform in Greece during times of permacrisis.

In addition, the capacity of public administration to effectively implement reforms is essential for overcoming systemic challenges (Politt and Bouckaert, 2011). Moreover, Weber’s bureaucratic theory (Weber, 1922) underscores the importance of a well-functioning bureaucracy in executing policy decisions, which remains a challenge in Greece due to its historically clientelistic and politicized public sector. Lipsky suggests that the attitudes and behaviors of public administrators and frontline workers can significantly influence reform outcomes (Lipsky, 1980). In the Greek context, administrative inertia and resistance at various levels of governance have often diluted the impact of reforms. Consequently, building administrative capacity and fostering a culture of accountability and professionalism within the public sector are crucial for ensuring that healthcare reforms are successfully implemented and sustained, especially in periods of prolonged crisis (Kanavos and Souliotis, 2017).

In this context, the purpose of our research is twofold: First, to analyze Greek citizens’ perspectives on the healthcare system and its reforms during times of permacrisis, with a specific focus on how such crises can accelerate the implementation of reforms. Second, based on citizens’ perspectives, we aim to identify the most relevant factors that explain the political inertia characterizing the Greek healthcare system over the last decade. Our analysis also examines specific policies that, according to citizens, are more efficient and, therefore, more acceptable, providing insights into the types of reforms that could improve the system’s resilience in the face of future crises.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Ethics approval

Ethical review and approval were not required for the current study in accordance with the national legislation. The study was assessed by the Health Policy Institute’s (Research) Ethics Committee, which declared that the protocol did not fall under the scope of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (Ν. 4957/2022). The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

2.2 Study methodology

A telephone survey of 1,000 citizens was performed between October and November 2017 and repeated on a different sample of 1,000 citizens in the same period in 2019 and 2021, respectively. The three time periods were selected in order to cover the period right after Greece’s exit from the financial assistance programs, the period of political changes following national elections and the period after the COVID-19 pandemic crisis.

All samples were defined via a multistage selection process using a quota for municipality of residence, sex and age. The research was conducted based on personal telephone interviews in the respondents’ households. A structured questionnaire was used on a proportional and representative sample of the Panhellenic population in terms of the area of residence. During the interviews, participants were asked to reflect on the following aspects: (a) Health status; (b) Healthcare use; (c) Views on structural healthcare reforms; and (d) Prioritization on healthcare reform initiatives. All interviews were fully anonymized.

3 Results

The survey results are based on the complete responses of 3,000 participants interviewed in the period between October and November of 2017, 2019 and 2021, respectively, (1,000 respondents per period). These data provide insights into Greek citizens’ opinions, preferences, and priorities regarding the Greek healthcare system and its reform and their level of trust in institutions following the fiscal crisis and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

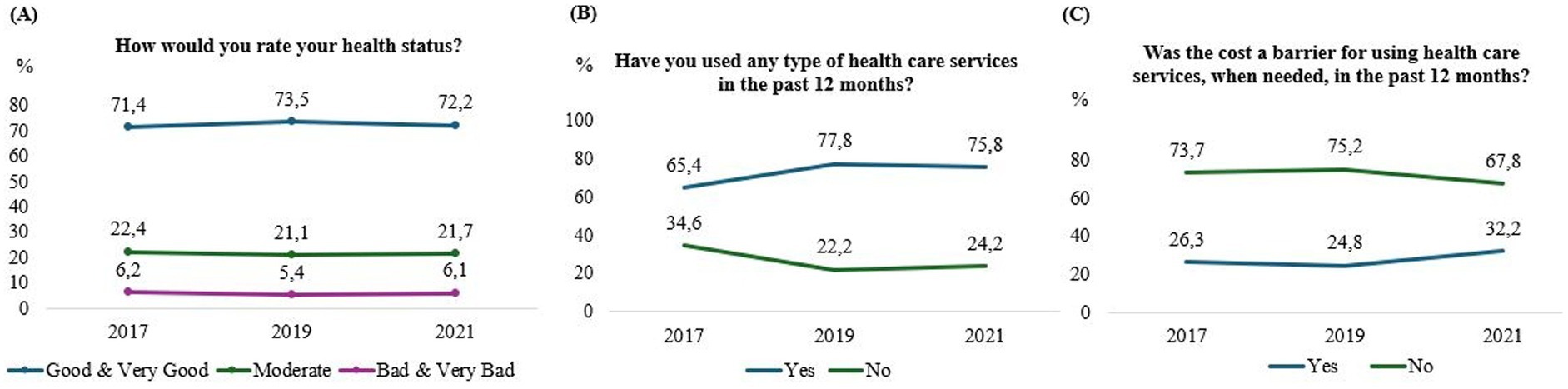

Across all survey periods, the majority of respondents rated their health status as “good” or “very good” (71.4% in 2017, 73.5% in 2019, and 72.2% in 2021) (Figure 1A). Of the respondents who required healthcare services in the year of their interview (65.4% in 2017, 77.8% in 2019, and 75.8% in 2021), nearly one in four reported being unable to access these services due to the high cost (26.3% in 2017, 24.8% in 2019, and 32.2% in 2021) (Figures 1B,C).

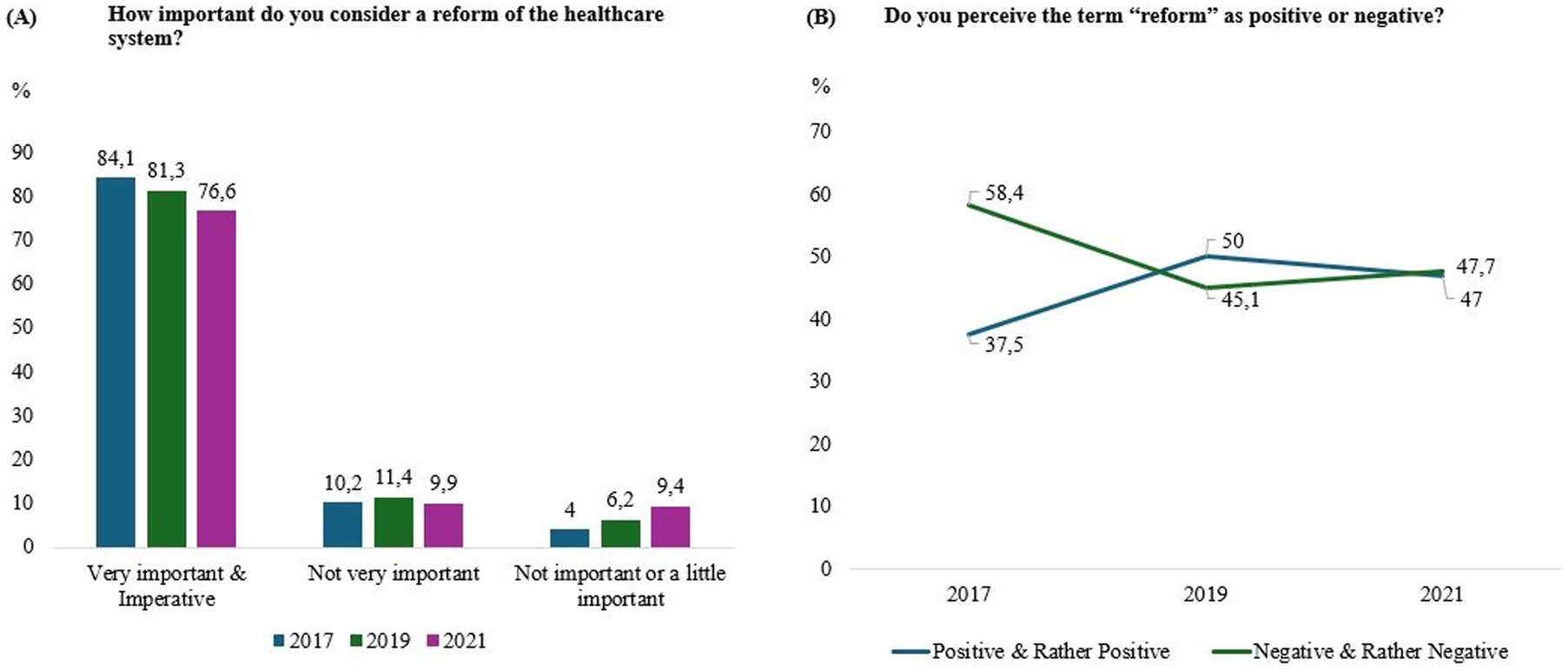

Our findings also reveal a paradox within the Greek healthcare system. While the central administration is often reluctant to implement reforms in the health sector, citizens consistently express a strong demand for such reforms (Souliotis, 2022). According to our survey, 80.7% of respondents viewed structural reform of the Greek healthcare system as imperative (84.1% in 2017, 81.3% in 2019, and 76.6% in 2021). At the same time however, approximately 50.8% of respondents perceive reform efforts negatively (58.4% in 2017, 45.1% in 2019, and 47.3% in 2021), reflecting low institutional trust shaped by previous experiences with healthcare interventions (Figures 2A,B).

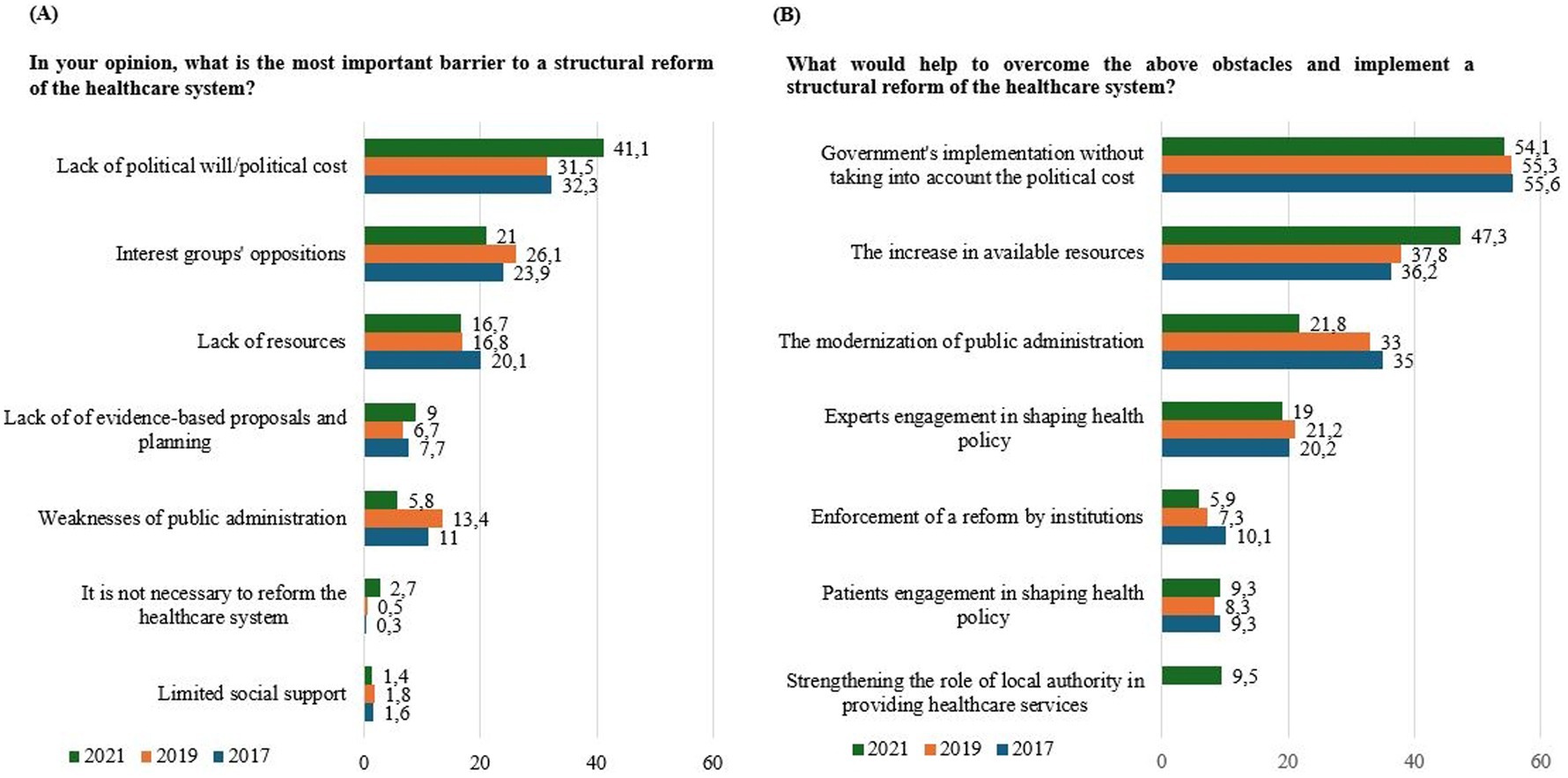

Another key insight concerns the reasons for Greece’s lack of healthcare reforms. As shown in Figure 3A, throughout the study period, the primary barrier to reform identified by respondents was the lack of political will, followed by resistance from professional and interest groups, and a shortage of public resources. Notably, the proportion of citizens identifying political cost as the main obstacle to reform increased from 32.3% in 2017 and 31.5% in 2019 to 41.1% in 2021. This suggests that political cost and opposition to reforms are closely linked, often outweighing the willingness to pursue political change (Souliotis, 2019). In parallel, respondents considered increased public funding (average 40.4%) and modernisation of public administration (average 29.9%) to be critical factors for the successful implementation of structural healthcare reforms (Figure 3B).

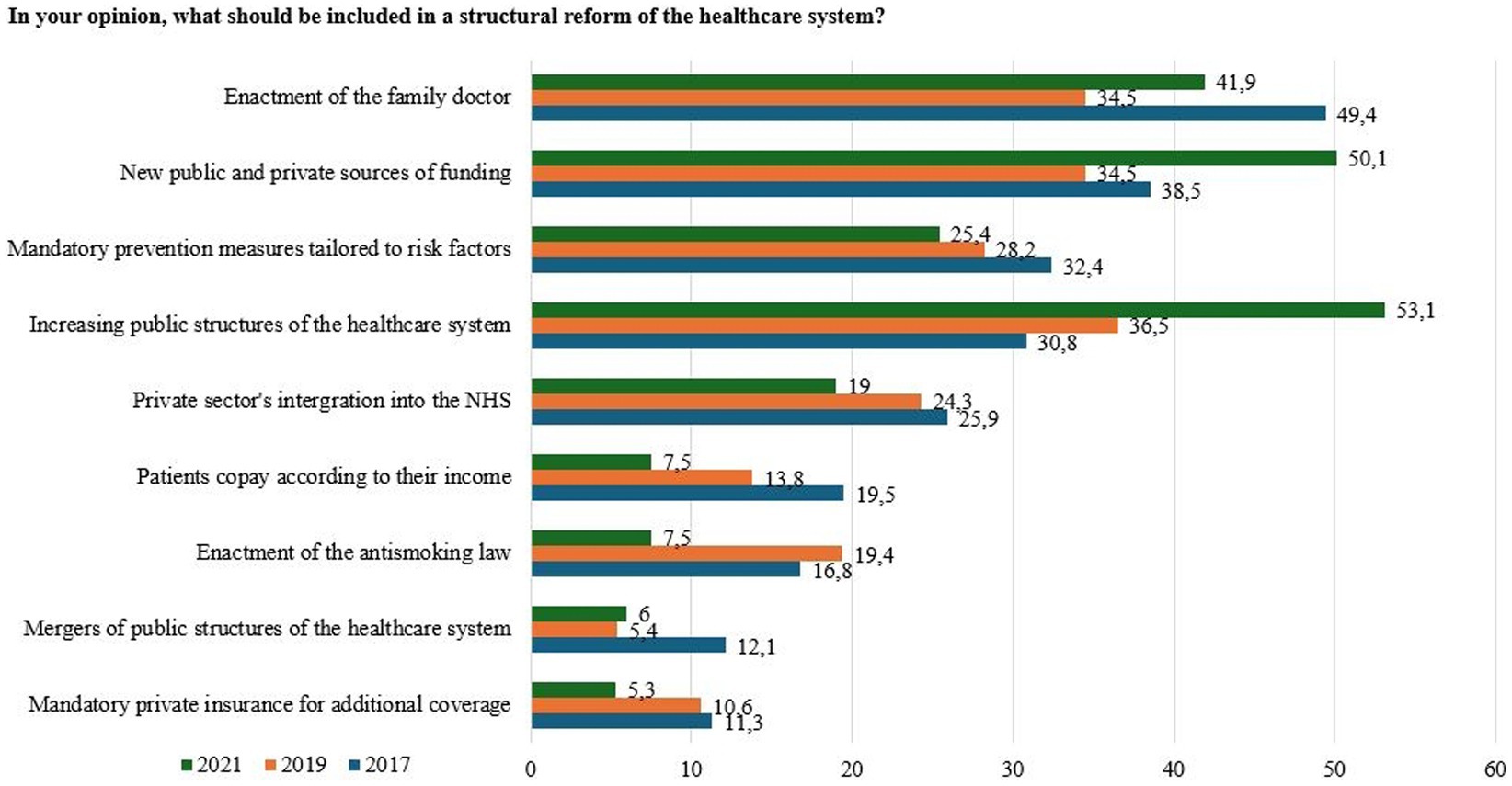

Finally, the survey explored specific policies that citizens believe would enhance the efficiency of healthcare services. Among the top priorities were the introduction of a family doctor system (49.4% in 2017, 34.5% in 2019, and 41.9% in 2021) and the establishment of new financing schemes, such as a combination of public and private funding sources (38.5% in 2017, 34.5% in 2019, and 50.1% in 2021). There was also an increasing demand for expanding public health infrastructure, rising from 30.8% in 2017 to 36.5% in 2019 and 53.1% in 2021 (Figure 4).

4 Discussion

The Greek National Healthcare System (ESY), established in 1983, has been plagued by dysfunction and inefficiency since its inception (Makrydimitris and Michalopoulos, 2000; Dimitrakopoulos, 2001; Spanou and Sotiropoulos, 2011; Kalavrezou and Jin, 2021). Despite numerous reform proposals, few have been legislated, and even fewer have been successfully implemented.

The capacity of the Greek public administration to execute healthcare reforms has been consistently characterized as limited, with reform efforts often driven by domestic stakeholders rather than comprehensive government-led initiatives (Spanou, 2020). Prior to the economic and COVID-19 pandemic crises of 2011 and 2020, healthcare system reforms were typically the result of partial legislative actions combined with independent stakeholder initiatives, rather than a rational, coordinated effort by health policy decision-makers (Tragakes and Polyzos, 1998).

Our findings highlight a paradox within the Greek healthcare system. Although Greek citizens consistently express a desire for healthcare reform, policymakers demonstrate indecision and a lack of political will. Interestingly, citizens advocate for necessary reforms regardless of the political cost, suggesting that public demand for change is vital. However, a significant portion of the population simultaneously views healthcare reforms negatively.

This contradiction reflects the absence of a cohesive framework within the political system and Greek society to implement effective structural reforms across public administration and public policy (Papadonikolaki and Souliotis, 2023). A counter-reform ideology has prevailed for extended periods, particularly in the complex healthcare sector, where prolonged political inertia has resulted in incomplete reforms or interventions that fail to deliver their intended outcomes. Resistance to necessary innovations has become instinctual, perpetuating uncertainty around reform efforts and frequently impeding their implementation, despite the clear benefits that many reforms could bring to the population (Rodrik, 1999).

Nevertheless, policy changes and even substantial reforms are more likely to be implemented during periods of crisis, as external pressures create momentum for structural change (Da Silva et al., 2017). Indeed, reform activity in Greece significantly increased following the onset of the first bailout program, driven by the need to maintain the country’s position within the European Union (Featherstone, 2015). The economic crisis of 2011 pushed critical issues onto the national policy agenda, accelerating the pace of healthcare reforms. Faced with the threat of economic collapse and the stringent conditions of international bailout agreements, Greece implemented reforms at an unprecedented rate, with external pressures playing a significant role in shaping these changes. The crisis created a “window of opportunity” (Cortell and Peterson, 1999) or served as a “device of change” (Hermann, 1963) to overcome longstanding institutional inertia and resistance. Additionally, the severity of the economic crisis galvanized public support for previously politically unfeasible reforms, as the imperative to avoid a Eurozone exit motivated policymakers and the public to endorse rapid reform initiatives.

Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 acted as a powerful catalyst, much like the economic crisis a decade earlier. The unprecedented public health emergency fostered widespread consensus on the urgent need for systemic change, compelling both policymakers and the public to acknowledge the inefficiencies within the existing healthcare system (Tragakes and Polyzos, 1998; Lampropoulou, 2021). This recognition spurred a series of reforms aimed at enhancing the resilience and efficiency of public services, including the digital transformation of healthcare services, collaboration between the public and private sectors, expansion of intensive care units, implementation of a universal vaccination program, and the increased role of health experts in shaping health policy.

Crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic expose the vulnerabilities of existing systems, prompting a revaluation of priorities and approaches. This disruption creates a window of opportunity for policymakers and stakeholders to advocate for and implement significant changes that may have previously been resisted. The pandemic can be viewed as a “policy punctuation,” accelerating the abandonment of outdated pathways and opening opportunities for policy innovation (Hogan et al., 2022). This concept aligns with Kingdon’s multiple streams framework, which suggests that crises create windows of opportunity, allowing policy entrepreneurs to advance previously unattainable reforms (Kingdon, 1995). The pandemic has facilitated the adoption of new policies and practices across various sectors, including healthcare, education, and labor markets, with the potential for long-term transformation as societies adapt to new realities (Hogan et al., 2022).

For Greece, both the economic and pandemic crises have served as wake-up calls, highlighting the need for sustained and comprehensive reform efforts to build a more resilient state apparatus. These crises accelerated the implementation of transformative changes that might otherwise have taken years to achieve. However, despite the willingness of the central administration and public demand for healthcare reforms, Greek citizens often perceive reforms negatively, mainly due to a lack of perceived political will and the entrenched clientelist relationships within the system. As a result, low institutional trust and social capital levels contribute to a vicious cycle that hinders the successful implementation of healthcare reforms.

It remains to be seen whether these crises have created the conditions for long-term policy disruptions (Moreira and Hick, 2021) or if the resulting reforms represent short-term, “accidental” changes (Boin and ‘t Hart, 2022).

4.1 Strengths and limitations

This study’s strengths include using a large and representative sample across three critical time periods, which provides a comprehensive overview of public sentiment during and after major crises (Paulus and Vazire, 2007). The study also highlights the impact of both economic and public health crises on reform acceptance, offering valuable insights for policymakers.

However, limitations include the potential for response bias due to the self-reported nature of the data, as well as the study’s focus on Greece, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other contexts (Sedikides and Strube, 1995; Razavi, 2001).

5 Conclusions and recommendations for further research

The findings of this study underscore the complexity of healthcare reforms in Greece, particularly in the context of prolonged periods of crisis, or permacrisis. While there is strong public support for structural reforms, there is a concurrent distrust in the ability of political institutions to implement these changes effectively. This paradox, where citizens demand reforms yet remain sceptical about their outcomes, points to the critical need for restoring institutional trust and addressing the systemic clientelist dynamics that have long hindered progress.

Crises, such as the 2011 economic collapse and the COVID-19 pandemic, have proven to be catalysts for reform, providing rare political and social opportunities to implement changes that would otherwise face resistance. However, the challenge moving forward is to ensure that these reforms are not merely reactionary but are sustained beyond times of crisis, fostering a resilient healthcare system capable of withstanding future disruptions. Furthermore, this study highlights the importance of aligning healthcare reforms with societal needs and addressing the underlying political and administrative barriers that contribute to reform failure. The Greek experience can serve as a valuable case study for other countries navigating similar challenges, offering lessons on how crises can open windows of opportunity for policy innovation, and how institutional trust is vital to the successful implementation of reforms.

Future research should explore how the momentum created during crises can be sustained in the long term, as well as investigate the potential for more participatory reform processes that engage citizens and healthcare professionals in shaping the future of healthcare systems. Such an approach may help bridge the gap between public demand for reform and institutional capacity for delivering meaningful change.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

KS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JP: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Health Policy Institute, for providing access to the database required for the analysis of this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agunsoye, A., and Fotopoulou, E. (2023). “Introduction: permacrisis, overlapping crises, inter-crises” in Heterodox economics and global emergencies. eds. A. Agunsoye, T. Dassler, E. Fotopoulou, and J. Mulberg (London: Routledge).

Baumgartner, F. R., and Jones, B. D. (1993). Agendas and instability in American politics : University of Chicago Press.

Boin, A., and ‘t Hart, P. (2022). From crisis to reform? Exploring three post-Covid pathways. Policy Soc. 41, 13–24. doi: 10.1093/polsoc/puab007

Burau, V., Mejsner, S. B., Falkenbach, M., Fehsenfeld, M., Kotherová, Z., Neri, S., et al. (2024). Post-COVID health policy responses to healthcare workforce capacities: a comparative analysis of health system resilience in six European countries. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 139:104962. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2023.104962

Chiolero, A. (2023). Permacrisis: be wary of public health catastrophism. Lancet (London, England) 401, 1848–1849. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00391-4

Cortell, A. P., and Peterson, S. (1999). Altered states: explaining domestic institutional change. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 29, 177–203. doi: 10.1017/S0007123499000083

Da Silva, A., Givone, A., and Sondermann, D. (2017). When do countries implement structural reforms? Frankfurt: Working paper series, ECB, no 2078.

Dimitrakopoulos, D. (2001). Learning and steering: changing implementation patterns and the Greek central government. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 8, 604–622. doi: 10.1080/1350176011006410

Featherstone, K. (2015). External conditionality and the debt crisis: the ‘troika’ and public administration reform in Greece. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 22, 295–314. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2014.955123

Featherstone, K., and Papadimitriou, D. (2008). The limits of Europeanization: reform capacity and policy conflict in Greece. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Grammatopoulos, D. K., Li, W., Young, L. S., and Anderson, N. R. (2023). UK diagnostics in the era of ‘permacrisis’: is it fit for purpose and able to respond to the challenges ahead? Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 61, e225–e226. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2023-0450

Haines, A., and Ebi, K. (2019). The imperative for climate action to protect health. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 263–273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1807873

Hermann, C. F. (1963). Some consequences of crisis which limit the viability of organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 8, 61–82. doi: 10.2307/2390887

Hogan, J., Howlett, M., and Murphy, M. (2022). Re-thinking the coronavirus pandemic as a policy punctuation: COVID-10 as a path-clearing policy accelerator. Policy Soc. 41, 40–52. doi: 10.1093/polsoc/puab009

Kalavrezou, N., and Jin, H. (2021). Healthcare reform in Greece: progress and reform priorities : International Monetary Fund Working Paper No. 2021/189.

Kanavos, P., and Souliotis, K. (2017). “Reforming health care in Greece: balancing fiscal adjustment with health care needs” in Beyond austerity: reforming the Greek economy. eds. C. Meghir, C. A. Pissarides, D. Vayanos, and N. Vettas (Cambridge: MIT Press), 359–402.

Kouris, G., Souliotis, K., and Philalithis, A. (2007). “Adventures” in the reform of the Greek health system: a historical review. Soc. Econ. Health 1, 35–67. [in Greek]

Lampropoulou, M. (2021). Public administration in the era of COVID-19: policy responses and reforms underway. ELIAMEP, Police Paper #74.

Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: dilemmas of the individual in public services. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Makrydimitris, A., and Michalopoulos, N. (2000). Experts’ reports on public administration, 1950–1998. Athens: Papazisis [in Greek].

Moreira, A., and Hick, R. (2021). COVID-19, the great recession and social policy: is this time different? Soc. Policy Adm. 55, 261–279. doi: 10.1111/spol.12679

Olson, M. (1982). The rise and decline of nations: economic growth, stagflation, and social rigidities : Yale University Press.

Papadonikolaki, J., and Souliotis, K. (2023). “Society, politics and health reform in Greece” in Health and society, changing relationships and pathways. eds. C. Oikonomou and M. Spyridakis (Athens: Dionikos). [in Greek].

Paulus, D. L., and Vazire, S. (2007). “The self-report method” in Handbook of research methods in personality psychology. eds. Robins, R. W., Fraley, R. C., and Krueger, R. F. (New York: The Guilford Press).

Politt, C., and Bouckaert, G. (2011). Public management reform: a comparative analysis - new public management, governance, and the neo-Weberian state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J. Democr. 6, 65–78. doi: 10.1353/jod.1995.0002

Putnam, R. D., Leonardi, R., and Nonetti, R. Y. (1993). Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Razavi, T. (2001). Self-report measures: an overview of concerns and limitations of questionnaire use in occupational stress research (discussion papers in accounting and management science, 01–175). Southampton, UK: University of Southampton, 23.

Robinson, J. A., and Acemoglu, D. (2012). Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. New York: Random House.

Rodrik, D. (1999). Where did all the growth go? External shocks, social conflict, and growth collapses. J. Econ. Growth 4, 385–412. doi: 10.1023/A:1009863208706

Sedikides, C., and Strube, M. J. (1995). The multiply motivated self. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 21, 1330–1335. doi: 10.1177/01461672952112010

Skalkos, D. P. (2018). Studying the political economy of reforms: the Greek case, 2010-2017. Theor. Appl. Econ. 25, 163–186.

Souliotis, K. (2022). Health policy in the entanglements of the economic and pandemic crisis: the Greek adventure. Nea Estia. 187, 315–326. [in Greek].

Spanou, C. (2020). External influence on structural reform: did policy conditionality strengthen reform capacity in Greece? Public Policy Admin. 35, 135–157. doi: 10.1177/0952076718772008

Spanou, C., and Sotiropoulos, D. (2011). The odyssey of administrative reforms in Greece, 1981–2009: a tale of two reform paths. Public Adm. 89, 723–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01914.x

Tragakes, E., and Polyzos, N. (1998). The evolution of health care reforms in Greece: charting a course of change. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 13, 107–130. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1751(199804/06)13:2<107::AID-HPM508>3.0.CO;2-O

Weber, M. (1922). Economy and society: an outline of interpretive sociology. Berkley: University of California Press.

Keywords: health reform, health policy, crisis, social capital, institutional trust, interest groups, political will

Citation: Souliotis K and Papadonikolaki J (2024) Resilient health reforms in times of permacrisis: the Greek citizens’ perspective. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1470412. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1470412

Edited by:

Stylianos Ioannis Tzagkarakis, Hellenic Open University, GreeceReviewed by:

Stamatina Douki, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, GreeceGeorgia Dimari, Ecorys, United Kingdom

Apostolos Kamekis, University of Crete, Greece

Copyright © 2024 Souliotis and Papadonikolaki. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kyriakos Souliotis, a3NvdWxpb3Rpc0B1b3AuZ3I=

Kyriakos Souliotis

Kyriakos Souliotis Jenny Papadonikolaki

Jenny Papadonikolaki