- 1Department of Government, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia

- 2Department of Political Science, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia

Indonesia’s transmigration areas are recognized for failing to fulfill advancement necessities, particularly spearheading progress in remote rural regions. Despite the dynamic characteristics, Village Community Organizations (VCOs) have made transmigration village development more progressive and promising. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the engagement of VCOs, such as economic, women, and youth organizations, in developing transmigration areas. This study uses qualitative methods with data collection techniques in the form of observation and in-depth interviews in nine villages in Indonesia. A community-driven development approach was used to analyze the development of transmigration villages. The study further identified three main factors: social capital, education, and support from the village government for VCO initiatives. These factors significantly influenced the actions to foster development within each transmigration village. The results provided significant insights into the crucial role of VCOs in empowering transmigration areas. This study recommends that policymakers apply this model to encourage greater community involvement, where strengthening resources in VCOs will increase community participation in sustaining rural development. The study further complemented previous publications by examining the role of VCOs, which was neglected in developing countries such as Indonesia.

1 Introduction

Following the new village development in 2014, Indonesia’s rural areas are moving toward significant changes in the nationwide advancement of the regions. The new mechanism for village development is regulated in Law No. 6/2014 or Village Law. An aspect of development is the inclusion of Village Community Organizations (VCOs) in various issues, such as enhancing village economy, empowering women, and engaging youth. The engagement will motivate community participation and represent a progressive step toward more inclusive development (Antlov, 2019; Mariana et al., 2017; World Bank, 2021). This marks a moment of change for transmigration areas, which various publications have identified with numerous problems (Simpson, 2021; Tirtosudarmo, 2018; O’Connor, 2004; Martin, 2014; Tachibana, 2016).

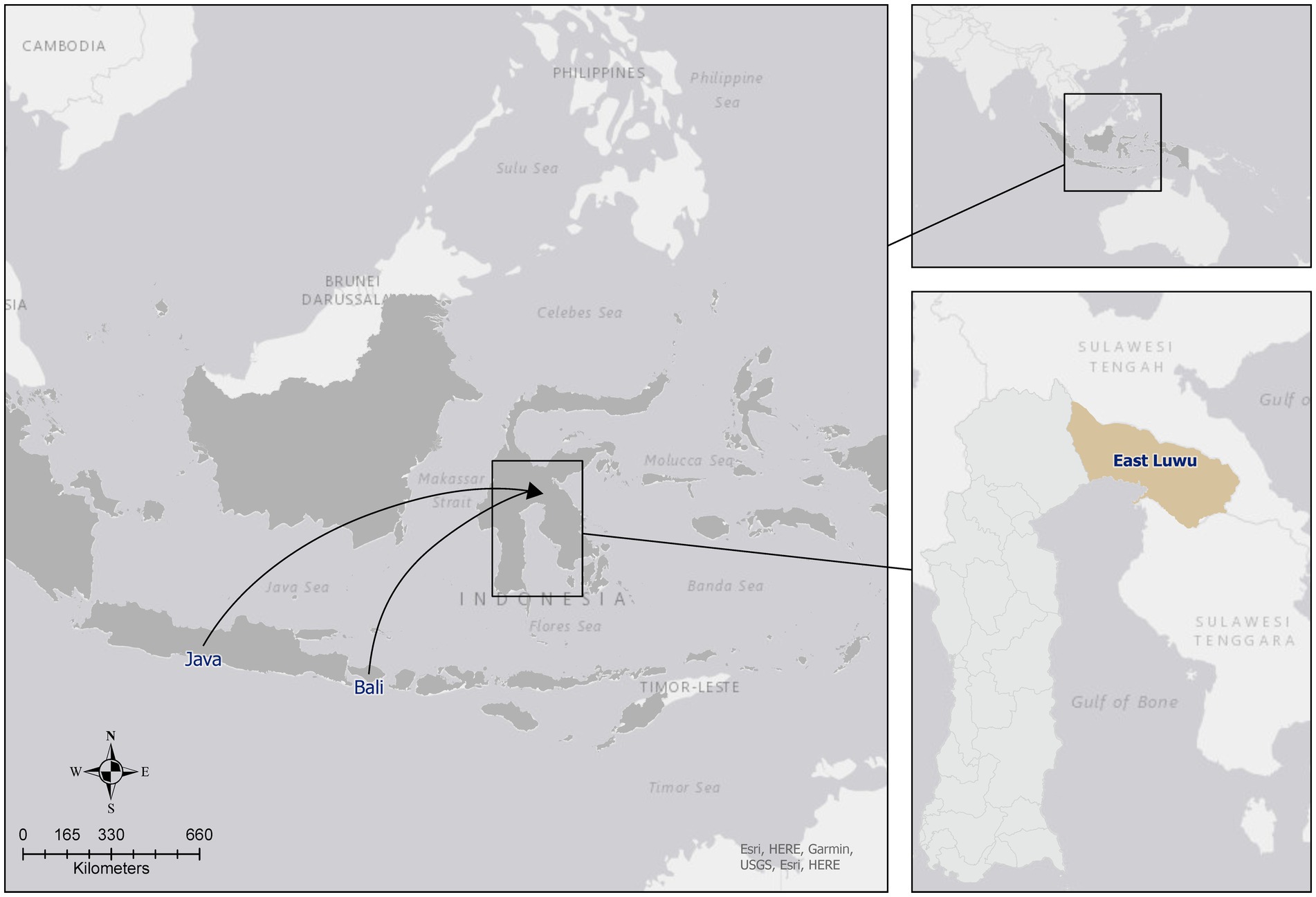

Transmigration areas are rural regions developed from the resettlement programs. The program is conducted in Indonesia and other developing countries to facilitate more equitable wealth distribution and strengthen the central government’s position in the periphery (Hoey, 2003; Van Der, 1985; MacAndrews, 1978). In Indonesia, transmigration is a government-established program to relocate residents from densely populated areas to more rural areas for development. The program began during Dutch colonial authority in the early twentieth century and was later continued by the government following independence. This initiative primarily relocates populations from the Java, Bali, and Lombok islands to Sumatra, Kalimantan, Papua, and Sulawesi. Transmigration areas offer a unique context for implementing the new village development initiatives through Village Law. Therefore, transmigration areas can also enhance development through the role of VCOs by obtaining the success experience of other areas (Kania et al., 2021; Kariono et al., 2020; Kushandajani, 2019; Diprose et al., 2021).

Recent literature on transmigration in Indonesia identifies the perceived failure of development (Simpson, 2021; Zaman, 2021), leading to negative effects (Warganegara and Waley, 2021; Lai et al., 2021). However, this study challenges the idea of transmigration as a failure in rural development in the country. Transmigration areas are currently experiencing significant changes in contemporary rural development. The role of community organizations and participation has also strengthened the areas alongside the position of the community. Conversely, investigation on this topic is scarce, specifically concerning the role of VCOs in neighborhood development, with few studies mainly from India (Montgomery, 1979; Meinzen-Dick and Raju, 2000). The role of VCOs has also not been internalized into village, leading to a disregard for the composition of development actors in the current transition. This study further contributes to the existing literature on transmigration village development. Additionally, transmigration villages still receive limited attention from rural development publications in Indonesia, specifically those on Sulawesi Island.

The study further explores the participation of VCOs in development of transmigration areas in Indonesia, such as PKK (Pembinaan Kesejahteraan Keluarga or Guidance for Family Welfare), Karang Taruna (voluntary youth organizations), and BUMDesa (village-owned enterprises). Furthermore, the community-driven development approach (Mansuri and Rao, 2013; Mansuri and Rao, 2004) is adopted as a theoretical framework to analyze transmigration village development. Mansuri and Rao (2004) also identified three key elements of community-driven development: participation, community, and social capital. Based on the framework, four models of village development are proposed following the results of the transmigration village case study: initiator, regulator, facilitator, and executor. These models are implemented by village government in collaboration with VCOs to stimulate development forward.

The results suggest that new village development in Indonesia offers essential insights into the role of VCOs in supporting the empowerment of transmigration areas beyond the state-centered methods. This discovery contributes to the existing literature on transmigration by emphasizing the potential role of VCOs in rural development in Indonesia. The study further offers new perspectives for future rural publications, particularly regarding the role of VCOs and the transition to developmentalism in developing countries. The study begins with an overview of rural development and transmigration in Indonesia, outlining the dynamics of transmigration advancement from colonialism to new developmentalism. It then emphasizes the development of new areas in the transmigration village, focusing on the progressive and promising changes in internal governance. The role of VCOs is subsequently explored, particularly in economic (BUMDesa), women (PKK), and youth (Karang Taruna) organizations. Finally, the implications of the results for mapping variations and challenges in transmigration village development in Indonesia are discussed.

2 Literature review: transmigration and rural development

Transmigration was a policy capable of accelerating equitable development in developing countries (Hoey, 2003; Van Der, 1985; MacAndrews, 1978). Through the distribution of populations and the structuring of new settlements, transmigration program evolved as the most significant and rapid migration mechanism in the history of rural development (MacAndrews, 1978). Certain publications even referred to the program as history’s most significant human relocation project (Simpson, 2021; Arndt, 1983; Dawson, 1994). Indonesia used transmigration program to develop remote areas across the country (Van Der, 1985). Upon introduction of the program, approximately 4 million individuals were relocated from densely populated areas in Java and Bali to the country’s outermost regions, including Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua (Leinbach, 1989). Indonesia had the highest number of relocated individuals in Southeast Asia (MacAndrews, 1978). Transmigration was expected to enhance rural development in Indonesia, with population movements from Java and Bali to the East Luwu regency, as depicted in Figure 1.

Various critics argued that Indonesia’s transmigration program failed to meet the expected development demands. Simpson (2021) asserted that the programs in several countries including Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, and the Philippines, were only a guise to reduce post-Cold War tensions. Tirtosudarmo (2018) further regarded transmigration as a skeptical policy of the government’s inability to control population growth. Even other studies acknowledged the reality that transmigration program became a field of corruption (O’Connor, 2004; Martin, 2014). Transmigration program subsequently triggered new problems, including the environmental damage caused by the resettlement (Holden and Hvoslef, 1995). The movement of numerous individuals to other areas led to an increased need for housing, prompting the conversion of forests into residential zones (Lai et al., 2021; Holden and Hvoslef, 1995; Whitten, 1987). Fearnside (1997) emphasized that newcomers to new areas needed alternative livelihoods for survival due to severely limited employment opportunities in transmigration areas. The only options were farming and gardening, forcing the extraction of the environment and deforestation. The limited infrastructure and supporting services sector also compounded the socio-economic challenges faced by migrants (Tachibana, 2016).

Other studies with similar conclusions viewed transmigration as a failed policy effort, emphasizing the mechanism of transferring poverty from the “poverty center” to the outermost areas as a key criticism (O’Connor, 2004). Additionally, transmigration was sometimes perceived as the act of neglecting citizens in the outermost regions (Simpson, 2021). This opinion originated from observations in the field, which showed a decrease in financial support for the continuation of the programs in destination areas following the reformation era. Therefore, the implication was that some villagers were progressively displaced in transmigration areas. Moreover, a significant discussion among transmigration critics centered on ethnic conflict, with transmigration program being implicated as a trigger for dispute in various locations (O’Connor, 2004; Fearnside, 1997; Barter and Côté, 2015; Elmhirst, 2002; Suyanto, 2007; Elmhirst, 2000). While the program aimed to strengthen national unity, it often prompted ethnic friction (Simpson, 2021) due to the marginalization of local community under the pretext of rural development (O’Connor, 2004). In essence, transmigration was expected to support development, intensify agriculture, and develop lagging outermost areas but the program was more prone to be labeled a failure based on dominant literatures.

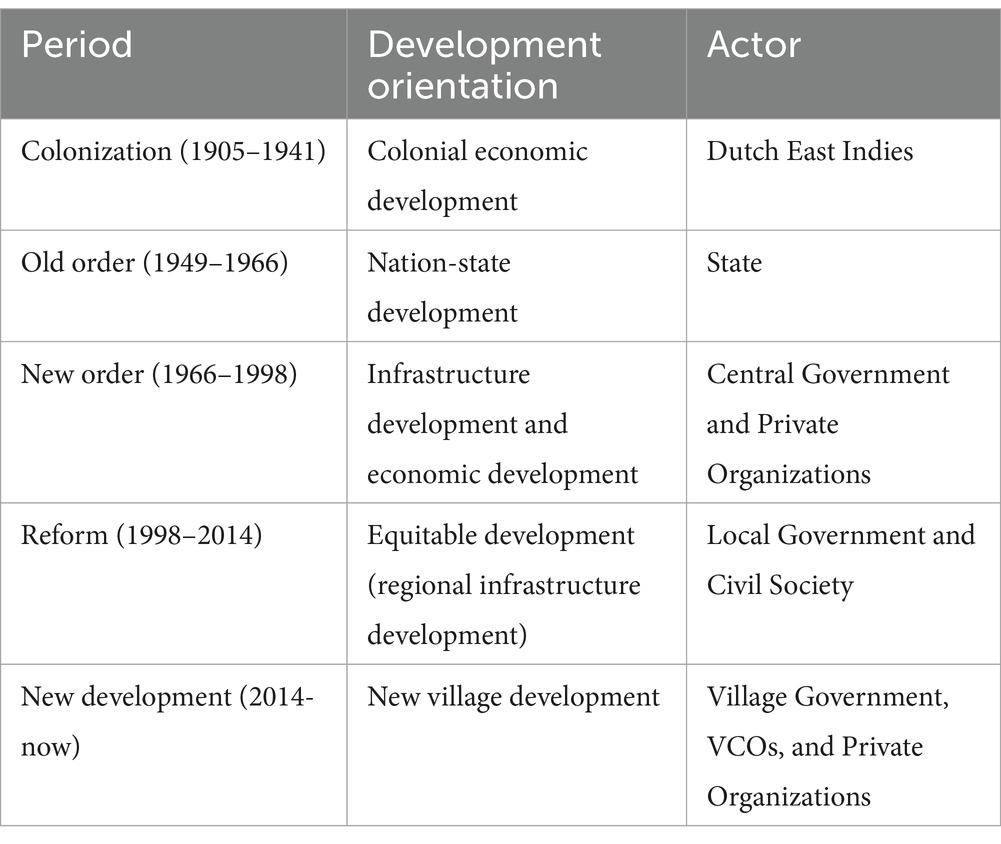

Throughout Indonesia’s history, transmigration has been closely connected to rural development evolving over four distinct periods with shifts in development orientation and actors as shown in Table 1. From 1905 to 1941, transmigration contributed to rural development commencing during the colonialization era (MacAndrews, 1978; Fearnside, 1997; Jones, 1979). During this phase, the Dutch East Indies with an economic development orientation played a regulatory role in development process. The forced planting policy was also connected to transmigration program, particularly for rubber plantations. The Dutch East Indies collaborated with transmigration through this policy to support economic development in remote Indonesian regions.

The period extending into the early independence era between 1949 and 1966 (the Old Order) witnessed development orientation primarily directed toward nation-state development, with the state serving as the predominant actor (Hoey, 2003). During this phase, the state assumed the sole role of regulator and held authoritative control over development, focusing more on integrating the nation’s territory than on physical advancement in rural areas. Furthermore, physical development in transmigration village occurred during the New Order period (1966–1998). In this period, development orientation toward prioritizing economic and infrastructure advancement, with the state and the private sector evolving as the main actors (Simpson, 2021). The highly centralized central government further dictated all development directions, exercising authoritarian control over the state’s role.

After the New Order, profound changes occurred during the Reform phase shifting development orientation from solely focusing on economic advancement to addressing infrastructure equity (Tirtosudarmo, 2018). The actors became more diverse, including the state, private sector, and civil society. In the context of development in transmigration areas, the state assumed roles as both regulator and facilitator. In the regulatory capacity, the state was empowered to oversee development according to respective needs through the government at the central and regional levels.

Decentralization was introduced as the main instrument in development process in the phase in contrast to the highly centralized predecessor. Subsequently, the facilitator role evolved to accommodate private sector and civil society engagement in rural development (Syukri, 2022). This transition marked a shift toward new developmentalism, expanding the actors in rural development beyond central and regional governments to include village governments, the private sector, and VCOs. The shift began a new era in rural development, characterized by increased emphasis on community engagement and sustainable practices. The revival of rural VCOs’ role in the progression process became evident during the new development era, characterized by the political reforms in village advancement as stipulated by the implementation of village Law.

3 Research methods

This study uses qualitative methods with data collection techniques such as observation and in-depth interviews (Miles et al., 2014). The observation process took place by observing several individuals and organizations in transmigrant villages in Indonesia. In conducting observations, the authors endeavored to maintain a balance between being an “insider” and an “outsider” in the daily activities of the villagers. Through observation, it is possible to learn both the explicit and the implicit aspects of people’s routine lives (DeWalt, 2014). In-depth interviews were conducted to explore information related to the government’s and villagers’ activities in accessing essential state services. The individuals who became research informants were those involved in organizing village communities. From this point, the research will expand to other informants (snowball sampling) to obtain comparisons. Interviews also took place with village government agencies involved and in direct contact with the community. In conducting the interviews, the authors were a “traveler.” The metaphor of the traveler understands the interviewer as a traveler on a journey that leads to a story to be told upon returning home (Kvale, 1996). The interviews were semi-structured and based on an interview guide outlining the main topics to be covered. However, this structure was flexible enough to tailor the topics to the interviewee. The interviews were also responsive to relevant issues from the informants, which could then be explored.

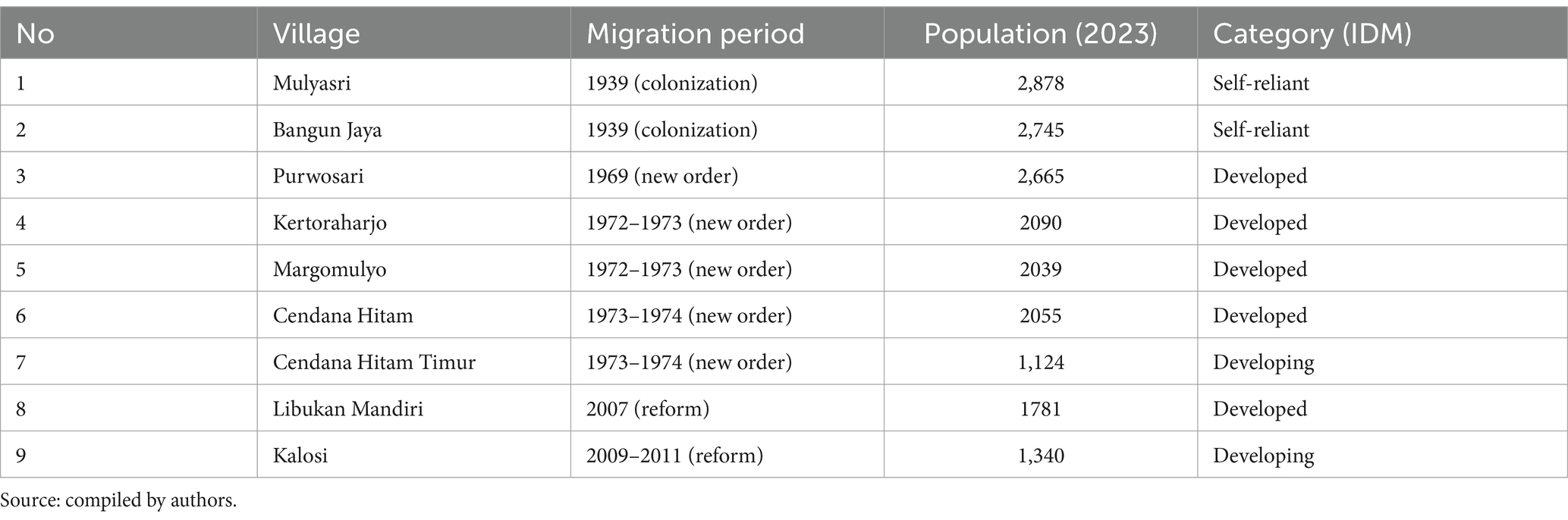

Two primary questions are raised: the investigative role of VCOs in influencing transmigration village development and the exploration of the variations in VCOs patterns concerning development challenges in each village. The study adopted in-depth interviews and direct observation of VCOs engagement to address the questions. Intensive two-month fieldwork is conducted in nine villages in East Luwu and South Sulawesi Provinces between 2022 and 2023 (see Table 2). These areas represent distinct periods of transmigration and development in South Sulawesi, including the pre-independence development (1939), the New Order development (1969–1974), and the post-democratic development eras (2007–2011). Additionally, the village development index category (IDM or Indeks Desa Membangun) is used to select the areas. Differences in transmigration periods and village development index aid in mapping variations in the advancement phases and resettlement across case study areas.

In-depth interviews were conducted with 85 key informants such as villagers, community organizations administrators, and village officials with an average of nine participants in each village. Direct observation focuses on daily political events, including interactions between VCOs, the government, and villagers, and examines village organizations’ profiles, roles, and programs. The interview results obtained from the field were categorized based on the research needs. This categorization process facilitates the formulation of answers to research questions because the research questions are used as a guide to select information that is relevant to the research. At the analysis stage, the data is described by discussing the field findings with theories or previous research results relevant to the research. This process is carried out to measure the extent to which the arguments and analysis built contribute to and have conceptual significance. In addition, the analysis process will also use secondary data from official government reports, such as reports from Indonesia Statistics and other agencies that have trusted credibility.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 New village development

Through Village Law, rural areas in Indonesia entered a new phase of village development. This phase was characterized by a shift toward the country’s new developmentalism, focusing on infrastructure and deregulation (Syukri, 2022; Warburton, 2016). The New Village Development in Indonesia characterized several distinct features. First, the government did not dominate the actors engaged in the development process (Antlov, 2019; World Bank, 2018). Development ideology followed the principles of neoliberalism, including various tools for good governance (Warburton, 2016). Furthermore, the community became engaged through the VCOs such as Karang Taruna, PKK, BUMDesa, and others. The VCOs provided a forum for expressing the political engagement of citizens, accessible at village level. Second, new village development strengthened the autonomy (Antlov et al., 2016; Nurlinah, 2020), empowering the authorities to prioritize personal needs over governmental interests. Through the inherent autonomy of village, the government and community were given the authority to decide the programs according to society’s needs.

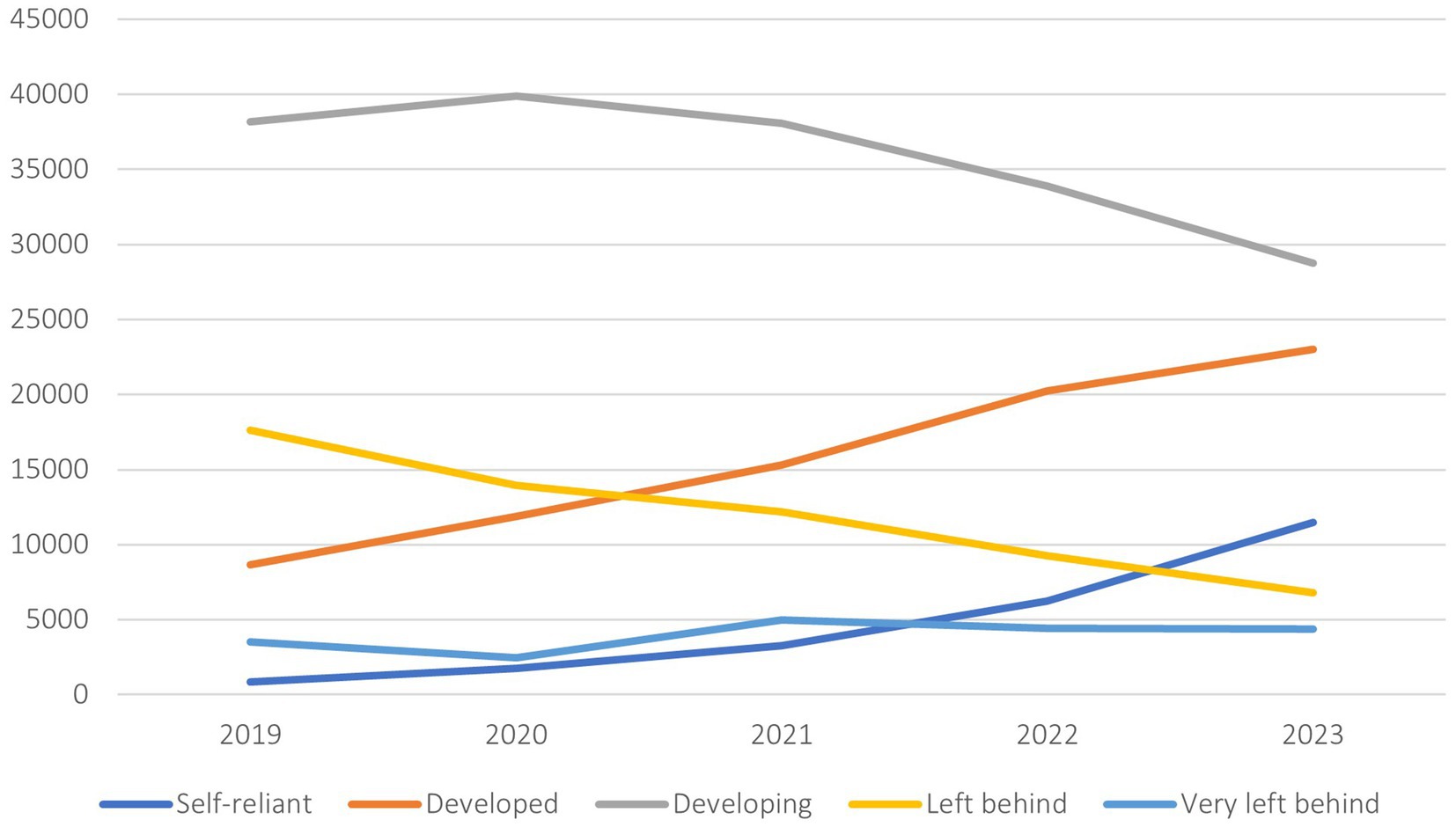

In the era of new village development, attention was shifted toward human resource development alongside infrastructure particularly crucial for remote rural regions such as transmigration areas. Human resource development was achieved by empowering all age groups, including women and youth. Rural economic development was another focal point facilitated by the establishment of Village-Owned Enterprises (BUMDesa). This development project was implemented in approximately 74,961 villages across the country. From 2019 to 2023, village development statistics showed an increasing trend in advancement as measured by IDM.1 Over the last 5 years, an increasing trend in the number of areas becoming self-reliant and developed was observed. A downward trend was also found in the number of developing and left behind areas. Additionally, the number of areas with very low development status remained stagnant with a slight decrease as shown in Figure 2. The statistical data showed that village development after Village Law suggested a positive trend.

Several studies initially reported doubts about village development (Lewis, 2015; Nurlinah et al., 2020; Nas and Nurlinah, 2019), including the failure of new developmentalism (Syukri, 2022) and decentralization (Haryanto et al., 2024). However, considerable attention was paid to developing these new areas, including increased economic development (Badaruddin et al., 2020) and rural democratization (World Bank, 2023). The rise of village entrepreneurship, women’s empowerment, and the democratization of village head elections were among the optimisms of new village development in many regions of Indonesia (Kania et al., 2021; Kariono et al., 2020; Kushandajani, 2019; Diprose et al., 2021; Berenschot et al., 2021).

The study analyzed new village development in nine transmigration areas to evaluate the extent of transformation in East Luwu, the northernmost district of South Sulawesi province. The nine areas were selected due to the diverse characteristics, such as the period of villagers’ migration to the area and the category based on IDM as detailed in Table 2. Transmigration village development reflected state efforts to democratize the process and enhance internal village governance within the decentralization paradigm (Antlov et al., 2016). This change in the internal governance signified a progressive and promising trajectory for transmigration areas in the context of new village development.

Four new village development models were identified in transmigration village. First, the paradigm included the village government as the initiator, stimulating community activities and promoting empowerment and human resource advancement. The government further initiated meetings by inviting various community stakeholders to discuss challenges faced. For instance, during the field visit, a meeting at village hall was observed to discuss issues related to BUMDesa. The village secretary also engaged with the youth to discuss Karang Taruna matters on another occasion. Furthermore, village head directly contacted the BUMDesa management to jointly address the vacant position of the treasurer in a different village, significantly impacting the region’s economic program plan. These instances showed how village governments took proactive steps to support village-level development, a practice that was not prevalent before the implementation of Village Law as discussed by an official in the province.

“This was not the first time having the activity in village. Whenever there was an unresolved problem, village government would initiate meetings or sometimes personally engage with several individuals to find solutions. Village collectively discussed the necessary steps to address the challenge promptly, ensuring the issue did not linger unresolved (Interview, Secretary of Mulyasari, July 3, 2023).”

Second, the community government acted as a regulator through the authority granted by Village Law. The authority allowed the issuance of regulations in the form of ordinances to address advancement necessities. In many areas, this opportunity accelerated development following the local community’s needs. For instance, the government served as a regulator by allocating incentives from village budget (APBDes) to various VCOs assisting in human resource development in Purwosari.

Third, community government adopted the facilitator model, actively supporting economic development for individuals and organizations. It further provided land for micro-business activities, fostering entrepreneurship within the region. In various instances observed during fieldwork, the government allocated spaces for cafes, sales outlets, and credit offices on village-owned land. For instance, unused land was repurposed into a market area for villagers in Kertoraharjo as explained by a participant during an interview.

“The shophouses along this road stand on village-owned land, village asset loaned by the government for commercial use. As long as the government hasn’t repurposed this land, community can use it for business activities. It’s considered village asset, including the public market (Interview, Secretary of BUMDesa Kertoraharjo, July 5, 2023).”

The pattern was consistently observed across transmigration area visited. Unused land assets were frequently entrusted to villagers for commercial purposes, providing indirect support that significantly fostered rural economy. Within this framework, village government’s role as a facilitator of rural economic development proved highly effective.

Finally, the model acted as an executor in overseeing development in village, particularly infrastructure projects. This marked a significant change for the governments, as rural infrastructure development was previously overseen by supra-village authorities such as district governments. The government showed remarkable flexibility in this new era of village development. It could initiate infrastructure projects independently without relying on directives from higher authorities and allocate resources according to community’s needs and demands.

Infrastructure development primarily supported agricultural activities, serving as a cornerstone for rural economic growth and sustainability. For example, village government constructed centers as venues for farmer forums and constructed farm roads to improve access to rice fields. The government also installed supporting infrastructure such as street lighting along village roads. Furthermore, an agricultural officer provided valuable insight into the infrastructure development efforts.

“Almost all farmer centres in the region received assistance from village government, ranging from full coverage to partial funding depending on village’s resources. Village government also supported farm road construction, among other initiatives (Interview, Agricultural Field Supervisor, August 4, 2022).”

The case study of transmigration areas in East Luwu prompted reflection on the concept of transmigration development failure. A distinct shift in development of the areas compared to previous models was observed. Specifically, the focus of development authority shifted away from supra-village governments toward greater autonomy for village administrations. This decentralization of power marked a significant change in village development landscape. Additionally, the active engagement of VCOs evolved as a crucial factor in fostering development. In rural governance, VCOs’ participation represented a significant and progressive stride toward village advancement.

4.2 VCOs’ participation

VCOs were community actors engaged in development process in Indonesia’s new village development era. Based on The Regulation of the Minister of Home Affairs No. 18/2018 on community and customary institutions, each village should have a minimum of six VCOs. However, only three VCOs were focused on in this study considering the contribution of human resources and rural economy development. Among these, PKK and Karang Taruna acted as VCOs and engaged in human resources development by empowering youth, women, and children while BumDesa concentrated on economic development as VCOs.

PKK primarily aimed to empower women and children, laying the foundation for the expanded role in the new village development era. The nature of PKK had changed significantly in the era of new village development, transforming into an empowerment platform for women. This role contradicted the previous era, where PKK was only a political instrument to disorganize the women’s movement (Wieringa, 1993). Currently, the VCOs’ pattern was to assemble women in transmigration villages, ensuring that family resilience was realized. Before the new development era, PKK only managed the Posyandu program, a primary health service initiative supported by community members and health workers. However, PKK became more progressive with various programs to increase women’s creativity in transmigration villages during the new development. These empowerment initiatives aimed to strengthen family resilience by fostering the growth of women’s groups within village.

PKK operated the programs across four main areas to empower women and enhance community resilience. First, it initiated religious activities and cooperation with village women’s groups regularly organizing weekly recitations and community service in all transmigration villages. Second, PKK launched programs to improve the skills of community. For instance, sewing training allowed certain villagers to develop economic businesses in Bangun Jaya village. Third, PKK managed a household resilience program through the Dasawisma initiative, which consisted of 10 to 20 households. Through this program, PKK mobilized villagers to provide food and health resources in the neighborhoods. Finally, PKK operated villagers’ health programs through Posyandu, addressing maternal health, stunting prevention, marriage guidance, and health for toddlers as well as older adults.

The VCOs played a role by forming PKK cadres to motivate women to be engaged in all development agendas in village. The label of PKK cadre provided a social incentive for women to volunteer. The VCO’s participation further increased the capacity of village women who previously had no structural skills to associate and organize. Consequently, PKK facilitated women’s empowerment by implementing various programs in village.

Karang Taruna further served as a platform for assembling youth to conduct coaching and development activities for the younger generation in village. It was also responsible for educating the village’s youth through various innovative and creative activities. In transmigration village, Karang Taruna assumed the role of an executor implementing technical policies at village level, particularly those related to youth development. Karang Taruna supported rural development by offering sports coaching, leadership training, and skills improvement programs for youth.

Karang Taruna’s contribution to development was minimal before Indonesia’s new village development era (Soehartono, 1991). During this period, there was no special allocation from village for the youth organizations leading to low activities and creativity due to lack of budget. Only with the introduction of village funds did youth empowerment activities begin to be included in the village budget. Karang Taruna management was established only after the introduction of village funds in 2015, executing youth empowerment policies through relevant programs established for village youth in the new village development era.

Karang Taruna creatively translates youth empowerment through sports activity programs, organizing annual soccer and volleyball tournaments for youth in Libukan Mandiri and Kalosi villages. Through sports activities, a platform was provided for the youth to channel hobbies and talents unavailable before the new village development era. Engagement in these activities ensured that Karang Taruna focused more on constructive matters within village. Additionally, youth empowerment was translated into leadership training programs, serving as a form of informal education. This activity facilitated the youth’s knowledge of various leadership and structural management matters, beneficial for the future of the youth in village.

BUMDesa evolved based on the 2014 Village Law aimed at strengthening the village economy to foster local autonomy by generating village revenue. The latest regulations governing BUMDesa were outlined in the Government Regulation of the Republic of Indonesia No. 11/2021. Furthermore, BUMDesa’s mission was to improve village economy by providing public services, increasing local own-source revenue (PAD), optimizing village economic resources, leveraging village assets, and developing digital economic ecosystems. The capacity to establish business units using six distinct models was held by BUMDesa, namely (1) a social business providing public services to community in exchange for financial benefits, (2) a business that rented out goods to fulfill community needs, and (3) a brokering business providing services to villagers. Other models included (4) a business that produced and traded certain community essential goods, sold on a broader market scale, (5) a financial business meeting the micro-scale businesses needs operated by villagers, and (6) a joint holding as the apex company developed by village, both at the local level and in rural areas.

BumDesa played a significant role in enhancing village economy, contributing to village budget and creating job opportunities. For instance, BUMDesa was established in 2018 and was sustained through various business units including credit services, water enterprises, and electricity token payment services in the case of Kertoraharjo village. This success translated into a substantial annual contribution of 75 million rupiahs to village treasury. Furthermore, BUMDesa in Bangun Jaya achieved self-sufficiency without relying on village government’s assistance. The businesses generated revenue of up to 1 billion rupiahs annually through diverse business units such as savings and loans, shops, tent rentals, as well as internet network provision.

Regarding job creation, BUMDesa Purwosari hired at least seven villagers in various capacities. The engaged villagers assisted in the administrative duties, treasury unit, and technical staff, with the wages depending on the profitability of the operations. Although the level of labor absorption remained limited, BUMDesa showed the roles in advancing rural economic development.

The evolution of VCOs in advancing transmigration areas provided new insights into the success story of new village development in Indonesia. The development changed the character of VCOs such as PKK and Karang Taruna, which were previously more inclined to be used by the government as political instruments to sustain the power of the governing regime. PKK was used to suppress the women’s movement while Karang Taruna controlled the youth within village. Consequently, the role of PKK and Karang Taruna remained inconspicuous within the framework of rural development from colonization to the reform era. The role and engagement of VCOs’ placed community participation as the foundation of village development. In transmigration areas, the presence of the VCOs created a platform for expressing desires and facilitating the implementation of villagers’ development proposals as input to village government’s general mechanisms.

Regarding BUMDesa, the VCO’s role and engagement evolved concurrently with the introduction of new village development ideas in Indonesia. BUMDesa played a significant role in developing the economy in the case study of nine transmigration areas. The study showed that with the VCOs’ participation, the increased economic independence of the nine areas motivated creativity and empowerment among villagers. Although each village in the case study had all three VCOs, the experiences and challenges in enhancing the development varied. This marked a significant departure from the era before new village development when the focus was solely on the centralized role of the state in regulating the economy. The advent of new village development had broadened the scope of actors engaged in the economic development through VCOs’ presence.

4.3 Variations and challenges

VCOs played a multifaceted role in enhancing development process in rural areas, with each VCOs making distinct contributions different from others. These varying contributions led to different impacts across village, with certain VCOs achieving considerable success in addressing development while others did not. The study further identified three main factors influencing the practice of VCOs in village development: social capital, education, and support from the village government. These factors influenced the different actions taken to create development in each transmigration village.

Social capital such as adat, played a significant role in determining the success of village development initiatives. Tradition (adat) significantly influenced VCOs activity in Javanese and Balinese transmigration areas. In predominantly Balinese regions, strong adat traditions correlated with higher VCOs engagement. However, VCOs activity tended to be lower in Javanese areas with fading adat traditions. For instance, adat affected the activity of Karang Taruna in the Kertoraharjo area, village where most of the population were Balinese migrants. This village had a tradition that youth should return to village after completing education or securing a job elsewhere. For example, Made Parta was village youth who had to return having completed the undergraduate education at a leading university in Bali and managed to secure a job. Conversely, the binding tradition that as a Balinese the eldest son could not leave home forced Parta to return to transmigration village where the parents currently live. Made Parta and other young men who also returned to village made organizations more active as it included many youths as explained in an interview with Parta.

“As the family’s son, there was no choice but to remain in village living there indefinitely. Contemplating the idea of contributing to village’s development considering the lifelong commitment to community, participation in local initiatives seemed inevitable. Eventually, Karang Taruna was introduced, offering an opportunity for participation (Interview, Made Parta, August 16, 2022).”

Young men were not obligated by customary requirements to remain in village in predominantly Javanese transmigration areas such as Margomulyo and Purwosari. However, many youths in village had a tradition of leaving, migrating to areas that provided more adequate employment opportunities, such as working in Palopo and Makassar or as nickel mine laborers in Morowali. Village secretary of Purwosari reported that over the last 3 years, approximately 80% of the youth opted to work outside village. Consequently, village officials expressed concern about the lack of youth participating in the Karang Taruna.

Transmigration areas with a Balinese majority had stronger collective ties than provinces dominated by Javanese villagers. These communal ties were primarily rooted in religious community activities. In Balinese, VCOs were commonly perceived as communal assets within the customary units. However, the collective was challenging to find in Javanese-majority transmigration areas. Individualism characterized the daily lives of Javanese villagers, where the existence of VCOs was not considered a common property but a few individuals’ property. For instance, the BUMDesa manager in the Javanese-majority Margomulyo village preferred to develop personal business rather than manage the BUMDesa.

In contrast to the Karang Taruna, PKK’s activity in the observed transmigration areas was better in Javanese-majority regions than in Balinese-majority provinces. The obedient attitude (manut) of Javanese women toward PKK symbolized motherhood and led to social sanctions for non-participation in activities. For instance, when a celebration occurred in village, someone would not get more visits than mothers who joined PKK including in the event of a disaster such as illness and grief. The concern of fellow mothers was not as good as when the person experiencing the disaster was part of PKK community. This condition indirectly bonded the kinship of the mothers influencing PKK activities to be more active. However, kinship was bridged mainly by the religious community for most Balinese transmigrant areas. The religious community mostly engaged in social activities including women and mothers, replacing the role of PKK.

The education of villagers further affected the performance of the VCOs. For instance, there were different variations in the role of Karang Taruna with some having a very significant role in village development while others were less visible. Youth organizations playing a significant role were also located in migrant areas with higher levels of education. In Kertoraharjo village, most Karang Taruna administrators were college graduates such as the chairman, secretary, and treasurer. However, youths were rarely engaged in Karang Taruna in areas with lower education levels. The low level of education implied that village youth opted to work as laborers as discussed in an interview with village secretary in Purwosari village.

“Karang Taruna was meant for youth organisations, catering to individuals in productive years. However, many educated youths felt compelled to seek employment often in places such as Morowali with limited job opportunities confined mainly to agriculture and odd jobs. This migration was driven by economic necessity, leaving behind a void in the revival of the Youth Organizations. (Interview, Purwosari Village Secretary, July 6, 2023).”

Similarly, for PKK, the level of education of women’s groups influenced their performance in supporting rural development. Most transmigration areas did not have adequate education for the members. A good education was only owned by a handful of certain individuals, such as the chairperson and secretary. Consequently, the performance of PKK was highly dependent on the chairperson and secretary as detailed in an interview with the Mulayasri village officials.

“Village PKK depended entirely on the presence of the chairwoman. When the chairwoman was active, it spurred the engagement of the members below. However, there was still a noticeable absence of initiative among the members to advance PKK forward (Bambang, Mulayasri Village Government Staff, July 4, 2023).”

The BUMDesa administrators were economics graduates in Kertoraharjo village who developed the program with impeccable governance using the educational background to document the VCO’s budget. However, finding active BUMDesa administrators in certain areas with low education levels was challenging. For instance, the BUMDesa remained inactive for over 2 years in Margomulyo village due to the absence of villagers with economic education to fill the treasurer role. This vacancy impeded BUMDesa’s activities, including the disbursement of operational funds.

The support from village government significantly impacted VCOs participation in development and also provided facilities. The success of BUMDesa Kertoraharjo in sustaining economic development was inseparable from the support provided by village government. For instance, village government provided a building for the BUMDesa office in a very strategic location. Additionally, the management explained that relatively large financial support from village government made survival easy for BUMDesa in Kertoraharjo compared to other transmigration areas.

“At the inception of the BUMDesa business, the village government received an injection of funds amounting to 100 million rupiah. Additionally, assistance in the form of an operational car unit was provided. This served as the initial capital for BUMDesa. The most valuable was the place of business that village government facilitated (Interview, I Nyoman Wibowo, Secretary of BUMDesa Kertoraharjo, July 5, 2023).”

The support from village government further influenced Karang Taruna’s role in developing youth potential. As in the Bangun Jaya and Kertoraharjo provinces, village government proactively opened communication spaces with Karang Taruna. The communication space was rarely found in other transmigration areas, allowing Karang Taruna to have a political channel in village’s development process. This included inputting village government on matters related to youth and village development in general.

Almost all village governments treated PKK in transmigration areas the same financially. The amount of allocation budgeted in the APBDes did not differ much from village to another. However, village governments provided support other than financial assistance in some cases. In Bangun Jaya village, the government provided a particular room for PKK secretariat which became a place for PKK activities such as meetings and coordination activities. PKK ideas were developed from this space in advancing communities, such as the use of home yards as medicinal plants for families in Bangun Jaya village.

The varied roles of VCOs in developing transmigration areas were inseparable from the complex situation in the field. Four challenges were identified, prompting the various variations that evolved in developing transmigration areas. First, the human resource factor became very dominant in determining the level of success of village organizations in development process of transmigration areas. A portrait of several BUMDesa and Karang Taruna successfully assisted development process in transmigration areas due to adequate human resources. Certain villages with inadequate human resources impacted the performance of VCOs in supporting development process. For instance, the role of the Karang Taruna organization was not significant due to limited human resources for youth in the Purwosari and Margomulyo regions. Similarly, mobilizing the BUMDesa was difficult due to human resources in Mulyasri village.

The influence of human resources on the role of village organizations in development process made organizations’ dependence on personal power very high. For instance, PKK was highly dependent on the personal power of the chairperson who determined the performance in supporting development process. PKK became active when the chairperson was active and vice versa. The high dependence on personalism further influenced village community’s uneven knowledge and human resource capabilities among women. As projected by Vedeld (2000), the dependence on personalities made it difficult for rural provinces to move collectively. Furthermore, village development was taken over by specific individuals and elites, which was dangerous for the sustainability of VCOs and the development of transmigration areas and others.

Second, salary was the next challenge identified as a factor determining the variation of VCOs in transmigration village development. Regarding the fieldwork, salary indirectly influenced villagers’ decision to participate in VCOs within village. Economic incentives were unevenly distributed among VCOs in transmigration areas, primarily benefiting structural apparatuses including RT and RW and some religious house administrators. The absence of salaries for VCOs such as Karang Taruna, PKK, and BUMDesa made villagers less interested in joining organizations. Based on the obtained observation, the salary motivated villagers to participate in village organizations. For example, the Posyandu cadre organizations had a solid structure at the village level and offered salaries to all cadres.

Third, there was increased awareness of the village’s future potential, particularly concerning BUMDesa. Primarily, the agricultural sector served as the sole resource for economic development within transmigration areas. However, this limited potential posed challenges to the sustainability of BUMDesa. In contrast to other sectors, agriculture lacked integration with BUMDesa businesses impeding profit orientation. Consequently, BUMDesa functioned more as a supplement to existing organizations than a profit-driven entity. Experiences and projections of the home village influenced the future expectations of BUMDesa development in transmigration areas. The average population in the areas originated from Java and Bali, which coincidentally have significant potential for tourism and services in Indonesia. This vision also evolved in transmigration areas, such as Mulyasri and Purwosari envisioning agricultural-based tourism for economic development. However, the existing conditions in transmigration areas did not support tourism due to the geographical isolation and focus on agriculture. Consequently, BUMDesa, when attempting to venture into tourism, often struggled to develop. Compared to Java and Bali, transmigration areas had smaller populations and limited economic turnover leading to few opportunities for service businesses.

Finally, certain VCOs’ success in transmigration areas was tied to the effective use of information technology, including social media. Empowering VCOs necessitated accommodating advancement in information technology. With the improved infrastructure extending into villages, the rapid dissemination of information among villagers underscored the need for VCOs to serve as filters and catalysts for empowerment. Information technology also has the potential to increase access to information, improve communication, and facilitate public services in villages. As the VCO in Bangun Jaya has done by accommodating advancements in information technology, it has improved access to information for residents while generating income for the village.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, new village development granted transmigration areas increased flexibility in pursuing advancement initiatives. It also expanded the role of VCOs to include empowerment, development, and guidance tasks designed for a responsive and contextual nature. This method provided sufficient clues about the actors engaged in rural development that were not state-centric, expanding the participation of stakeholders in village community through VCOs as political organizations, such as Karang Taruna, BUMDesa, and PKK. Transmigrants leveraged organizations and contributed to village development but the degree of success varied across each village. Despite these achievements, advancement levels varied significantly emphasizing the potential of VCOs in resource management and village development.

The new village development in Indonesia provided essential insights into the role of VCOs in supporting the empowerment of transmigration areas. This model fostered broader community engagement, exemplified by successes in East Luwu’s transmigration areas. However, there were some variations in realizing the model in transmigration areas, such as social capital, education, and support from village government. The variations are due to the complex challenges in each of the different villages including human resource capacity, low salaries for VCOs’ administrators, village potential influencing each area’s different levels of development, and accommodating advancement in information technology. Strengthening resources in VCOs should correlate with enhancing community participation. The results also complemented the past studies by observing the ignored roles of VCOs, particularly in transmigration’s responsibility in rural development in Indonesia. Additionally, attention to the role of village-level organizations in sustaining rural development was not studied widely. The study recommends that policymakers apply this model to encourage greater community involvement, where strengthening resources in VCOs will increase community participation in sustaining rural development. This would be a promising study theme to pursue in the future, particularly by examining how to understand the role of rural organizations in democratic transitions and political reforms in the Global South.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Fakultas Kesehatan Masyarakat, Hasanuddin University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

Nurlinah: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Haryanto: Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the editor of Frontiers in Political Science and two reviewers for their valuable comments on this paper. We also thank Sunardi for helping with the data collection, and Muhammad Ikhsan prepared the figures.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The Ministry of Villages has developed five village categories (IDM—Indeks Desa Membangun) based on their assessed level of welfare: self-reliant (mandiri), developed (maju), developing (berkembang), left behind (tertinggal), and very left behind (sangat tertinggal).

References

Antlov, H. (2019). Community development and the third wave of decentralisation in Indonesia: the politics of the 2014 village law. Swedish J Anthropol. 2, 17–31. doi: 10.33063/diva-409759

Antlov, H., Wetterberg, A., and Dharmawan, L. (2016). Village governance, community life, and the 2014 village law in Indonesia. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 52, 161–183. doi: 10.1080/00074918.2015.1129047

Arndt, H. (1983). Transmigration: achievements, problems, prospects. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 19, 50–73. doi: 10.1080/00074918312331334429

Badaruddin, B., Kariono, K., Ermansyah, E., and Sudarwati, L. (2020). Village community empowerment through village owned enterprise based on social capital in north Sumatera. Asia Pacific J Soc Work Dev. 31, 163–175. doi: 10.1080/02185385.2020.1765855

Barter, S. J., and Côté, I. (2015). Strife of the soil? Unsettling transmigrant conflicts in Indonesia. J Southeast Asian Stud. 46, 60–85. doi: 10.1017/S0022463414000617

Berenschot, W., Capri, W., and Dhian, D. (2021). A quiet revolution? Village head elections and the democratization of rural Indonesia. Crit. Asian Stud. 53, 126–146. doi: 10.1080/14672715.2021.1871852

Dawson, G. (1994). Development planning for women: the case of the Indonesian transmigration program. Womens Stud Int Forum. 17, 69–81. doi: 10.1016/0277-5395(94)90008-6

DeWalt, K. M. (2014). “Participant observation” in Handbook of methods in cultural anthropology. eds. H. R. Bernard and C. C. Gravlee (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield), 251–292.

Diprose, R., Savirani, A., Setiawan, K. M. P., and Francis, N. (2021). Gender, collective action and governance in rural Indonesia. Melbourne: The University of Melbourne.

Elmhirst, R. (2000). A Javanese diaspora? Gender and identity politics in Indonesia’s transmigration resettlement program. Womens Stud Int Forum. 23, 487–500. doi: 10.1016/S0277-5395(00)00108-4

Elmhirst, R. (2002). Daughters and displacement: migration dynamics in an Indonesian transmigration area. J. Dev. Stud. 38, 143–166. doi: 10.1080/00220380412331322541

Fearnside, P. M. (1997). Transmigration in Indonesia: lessons from its environmental and social impacts. Environ. Manag. 21, 553–570. doi: 10.1007/s002679900049

Haryanto,, Irwan, A. I. U., and Amaliah, Y. (2024). Elections, governance, and polarization in Indonesian villages. Asian Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 32, 175–193. doi: 10.1080/02185377.2024.2351400

Hoey, B. A. (2003). Nationalism in Indonesia: building imagined and intentional communities through transmigration. Ethnology 42, 109–126. doi: 10.2307/3773777

Holden, S., and Hvoslef, H. (1995). Transmigration settlements in Seberida, Sumatra: deterioration of farming systems in a rain forest environment. Agric. Syst. 49, 237–258. doi: 10.1016/0308-521X(94)00046-T

Jones, G. W. (1979). “Indonesia: the transmigration programme and development planning” in Migration and development in South-East Asia: a demographic perspective. ed. R. J. Pryor (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press), 212–221.

Kania, I., Anggadwita, G., and Alamanda, D. T. (2021). A new approach to stimulate rural entrepreneurship through village-owned enterprises in Indonesia. J. Enterpris. Commun. 15, 432–450. doi: 10.1108/JEC-07-2020-0137

Kariono,, Badaruddin,, and Humaizi, (2020). A study of women’s potential and empowerment for accelerating village development in Serdang Bedagai district, north Sumatera Province. Community Work Fam. 24, 603–615. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2020.1735302

Kushandajani,, and Alfirdaus, L. K. (2019). Women’s empowerment in village governance transformation in Indonesia: between hope and criticism. Int. J. Rural. Manag. 15, 137–157. doi: 10.1177/0973005219836576

Kvale, S. (1996). Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. California: SAGE Publications.

Lai, J. Y., Hamilton, A., and Staddon, S. (2021). Transmigrants experiences of recognitional (in)justice in Indonesia’s environmental impact assessment. Soc. Nat. Resour. 34, 1056–1074. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2021.1942350

Leinbach, T. R. (1989). The transmigration programme in Indonesian national development strategy: current status and future requirements. Habitat Int. 13, 81–93. doi: 10.1016/0197-3975(89)90023-4

Lewis, B. D. (2015). Decentralising to villages in Indonesia: money (and other) mistakes. Public Adm. Dev. 35, 347–359. doi: 10.1002/pad.1741

MacAndrews, C. (1978). Transmigration in Indonesia: prospects and problems. Asian Surv. 18, 458–472. doi: 10.2307/2643460

Mansuri, G., and Rao, V. (2004). Community-based and-driven development: a critical review. World Bank Res. Obs. 19, 1–39. doi: 10.1093/wbro/lkh012

Mansuri, G., and Rao, V. (2013). Localizing development: does participation work? Washington, DC: World Bank.

Mariana, D., Yudatama, I., Fitrianingrum, N., Angga, R. D., Pranawa, S., Yulianto, S., et al. (2017). Desa: Situs Baru Demokrasi Lokal. Yogyakarta: IRE Yogyakarta.

Martin, M. R. (2014). Inferior readings: the transmigration of 'Material' in Tamburlaine the great. Early Theatr. 17, 57–75. doi: 10.12745/et.17.2.1207

Meinzen-Dick, R., and Raju, K. V. (2000). What affects organization and collective action for managing resources? Evidence from canal irrigation systems in India. Food Policy 30, 1–26. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00130-9

Miles, M., Huberman, M., and Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. California: SAGE Publications.

Montgomery, J. D. (1979). The populist front in rural development: or shall we eliminate the bureaucrats and get on with the job? Public Adm. Rev. 39:58. doi: 10.2307/3110380

Nas, J., and Nurlinah, H. (2019). Indigenous village governance: lessons from Indonesia. Public Adm Issues 2019, 94–104. doi: 10.17323/1999-5431-2019-0-6-94-104

Nurlinah, N., and Haryanto, H. (2020). Institutional mechanisms and civic forum in coastal village governance in Indonesia. Public Policy Adm. 19, 76–85. doi: 10.5755/j01.ppaa.19.3.27832

Nurlinah,, Haryanto,, and Sunardi, (2020). New development, old migration, and governance at two villages in Jeneponto, Indonesia. World Dev. Perspect. 19, 100223–100210. doi: 10.1016/j.wdp.2020.100223

O’Connor, C. M. (2004). Effects of central decisions on local livelihoods in Indonesia: potential synergies between the programs of transmigration and industrial forest conversion. Popul. Environ. 25, 319–333. doi: 10.1023/B:POEN.0000036483.48822.2f

Simpson, B. (2021). Indonesian transmigration and the crisis of development, 1968–1985. Dipl. Hist. 45, 268–284. doi: 10.1093/dh/dhaa087

Soehartono, I. (1991). Karang Taruna (voluntary youth organizations) in Bandung, Indonesia: a planning study. New York: Columbia University.

Suyanto, S. (2007). Underlying cause of fire: different form of land tenure conflicts in Sumatra. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 12, 67–74. doi: 10.1007/s11027-006-9039-4

Syukri, M. (2022). Indonesia’s new developmental state: interrogating participatory village governance. J. Contemp. Asia 54, 2–23. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2022.2089904

Tachibana, T. (2016). “Livelihood strategies of transmigrant farmers in peatland of Central Kalimantan” in Tropical peatland ecosystems. eds. M. Osaki and N. Tsuji (Tokyo: Springer), 613–638.

Van Der, W. T. (1985). Transmigration in Indonesia: an evaluation of a population redistribution policy. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 4, 1–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00125539

Vedeld, T. (2000). Village politics: heterogeneity, leadership and collective action. J. Dev. Stud. 36, 105–134. doi: 10.1080/00220380008422648

Warburton, E. (2016). Jokowi and the new developmentalism. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 52, 297–320. doi: 10.1080/00074918.2016.1249262

Warganegara, A., and Waley, P. (2021). The political legacies of transmigration and the dynamics of ethnic politics: a case study from Lampung, Indonesia. Asian Ethn. 23, 676–696. doi: 10.1080/14631369.2021.1889356

Whitten, A. J. (1987). Indonesia’s transmigration program and its role in the loss of tropical rain forests. Conserv. Biol. 1, 239–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.1987.tb00038.x

Wieringa, S. E. (1993). Two Indonesian women’s organizations: Gerwani and the PKK. Bull. Concern Asian Sch. 25, 17–30. doi: 10.1080/14672715.1993.10416112

World Bank (2018). Participation, transparency and accountability in village law implementation: baseline findings from the sentinel villages study. Jakarta: The World Bank-Local Solutions to Poverty.

World Bank (2021). Delivering together: using Indonesia’s village law to optimize frontline service delivery. Jakarta: World Bank.

World Bank (2023). Village governance, politics, and participation in Indonesia. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Keywords: development, village community organizations, transmigration, village, Indonesia

Citation: Nurlinah and Haryanto (2024) Transmigration village development: the state and community organizations in rural Indonesia. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1441393. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1441393

Edited by:

A. K. M. Ahsan Ullah, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, BruneiReviewed by:

Syeda Naushin, University of Malaya, MalaysiaSulaimon Adigun Muse, Lagos State University of Education (LASUED), Nigeria

Copyright © 2024 Nurlinah and Haryanto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haryanto, aGFyeW11c2lAdW5oYXMuYWMuaWQ=

Nurlinah1

Nurlinah1 Haryanto

Haryanto