94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 06 May 2024

Sec. Peace and Democracy

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1375198

In December 2022, Indonesia and Vietnam concluded the EEZ boundary lines that have been under negotiations for 12 years. Through this, it is expected that intrusions made by Vietnamese maritime constabulary forces into Indonesia’s North Natuna Seas can end. On the contrary, intrusions have risen in the first 8 months of 2023, indicating Vietnam’s intent to continue its maritime-based operations in the gray-zone areas of Indonesian waters. In making sense of this developing crisis, this article adopts secondary data from the Indonesia Open Justice Initiative between January 2023 and August 2023. In tracking the instances of intrusions, it utilizes an Automatic Identification System obtained from Marine Traffic. The analysis is made by framing the crisis under the maritime diplomatic framework, which concludes that Vietnam is persistent with its maritime diplomatic strategy of “paragunboat diplomacy” in showcasing effective occupancy in gray zone areas.

In December 2022, Indonesia and Vietnam concluded a 12-year-long negotiation to end the uncertainties to the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) boundaries between the two states (KEMLU, 2022). The finalization of the boundary lines is significant, considering that Vietnam and Indonesia have encountered crisis after crisis in the past decade due to the illegal intrusions conducted by Vietnamese fishing fleets and by the Vietnam Fisheries Resources Surveillance (VFRS) (Parameswaran, 2019; Darwis and Putra, 2022; Putra, 2023; Yeo, 2023). However, recent developments in 2023 suggest that illegal fishing in Indonesia’s North Natuna Seas continues. Furthermore, similar to patterns observed before the conclusion of the 2022 EEZ agreement between Indonesia and Vietnam, the VFRS continues to display its presence within Indonesia’s sea jurisdictions.

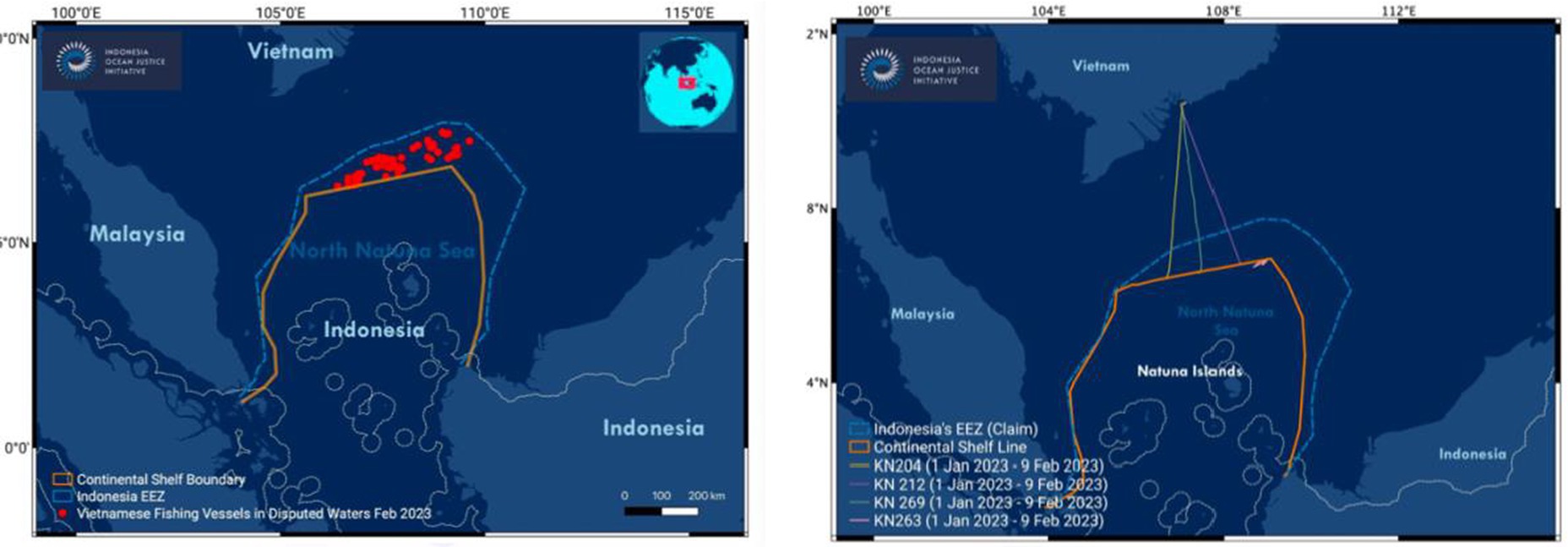

This article attempts to comprehend the recent developments in the North Natuna Seas. It observes the dynamics of illegal intrusions constructed by Vietnamese fishing vessels and the VFRS between January and August 2023, utilizing secondary data from the Indonesia Ocean Justice Initiative (IOJI). The data track illegal intrusions conducted by Vietnamese vessels through the Automatic Identification System (AIS) retrieved from the Marine Traffic. This article focuses on intrusions within Indonesia’s gray zone areas in the North Natuna Seas, which are the seas located between Indonesia’s EEZ and continental shelf line (see Figure 1 for the locations). In comprehending Vietnam’s sea-based maneuvers at sea, this study further adopts the conceptual framework of maritime diplomacy in understanding the motives and actions taken by Vietnam at sea. It argues that despite the conclusion to the EEZ boundaries between the two states, Vietnam is continuing its past maritime diplomatic pattern of “paragunboat diplomacy,” which is the utilization of civilian fleets (maritime constabulary forces, fishing fleets, fisheries surveillance vessels, and coast guards), to display physical effective occupancy in gray-zone (disputed) areas. Furthermore, the term gray zone areas used in this study is to represent an area with uncertain legal boundaries (McLaughlin, 2022). Consequently, in the case of the South China Sea, the gray zone areas lead to the conduct of state practices that are belligerent, coercive, and filled with ambiguity (as to the true intention of states) (Ormsbee, 2022). As Azad et al. (2022) recently argued, gray zone strategies are difficult to resolve, considering that it is unclear what international law is operational in those areas, and whether it falls under times of peace or war.

Figure 1. Vietnamese fishing vessels (left) and VFRS vessels (right) in the disputed zones of the North Natuna Seas, January 2023–February 2023. Source: Indonesia Open Justice Initiative (IOJI, 2023a,b).

Vietnam’s intrusions through its maritime-based fleets (fishing fleets and VFRS) are concerning. Despite the completed negotiations that initially started on May 21, 2010, there seems to be a high disregard within Vietnamese fleets toward the new EEZ boundaries. The establishment of Vietnam’s fishing fleets and the VFRS resulted from the 2009 National Assembly of Vietnam. Vis-à-vis tensions in the South China Sea, Vietnam decided to display effective occupancy over disputed waters by deploying its maritime constabulary forces (Jennings, 2021). Vietnam’s fishing fleets comprise 7,000 members (approximation) (Giang, 2018, 2022). Unfortunately, similar patterns of effective occupancy are currently displayed by Hanoi, causing significant doubt about the effectiveness of the recently concluded EEZ boundary lines.

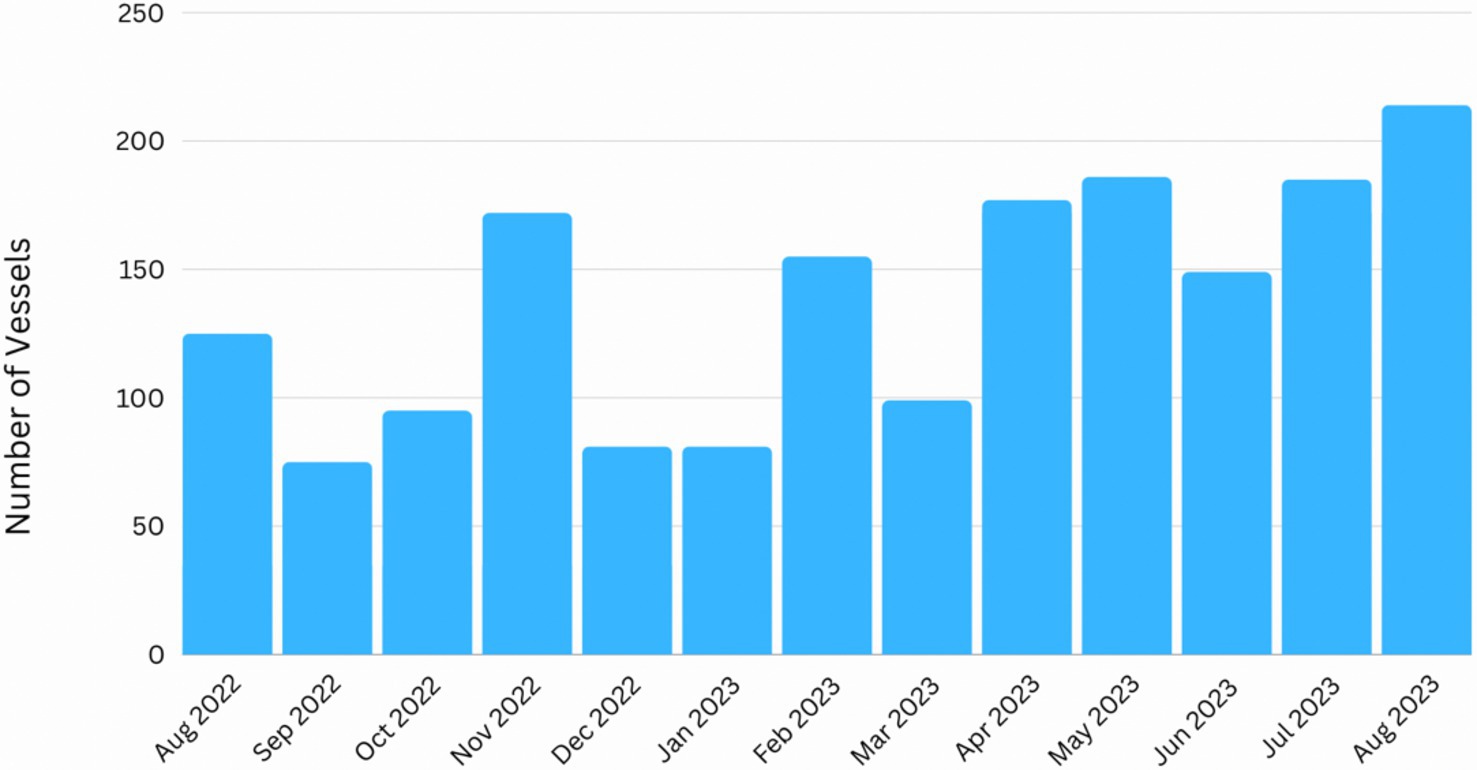

Data from IOJI showed that the number of intrusions conducted by Vietnam’s fishing fleets and VFRS is consistent with the numbers prior to the agreement. This is puzzling, as it shows that Vietnam is persistently adopting its traditional maritime diplomatic strategy of displaying effective occupancy in gray zone areas. Figure 2 depicts the number of Vietnam fishing vessels intruding Indonesia’s gray-zone areas in the North Natuna Seas. Unfortunately, this trend is increasing in numbers compared to the past year, showing a puzzling empirical pattern for Indonesian policymakers.

Figure 2. Vietnam fishing vessels in the disputed zones of the North Natuna Seas (August 2022–August 2023). Source: Indonesia Open Justice Initiative (IOJI, 2023a).

Figure 1 displays the areas in which Vietnamese fishing vessels conducted illegal fishing within Indonesia EEZ. Despite a relatively low number of intrusions in January 2023 (82), this number has consistently risen. This empirical fact indicates that Vietnam officials have disregarded the recent EEZ boundary agreement, as the same patterns of intrusions are conducted on a daily basis.

Meanwhile, the right side of Figure 1 showcases the unique patterns maintained by the VFRS, which reveals the possibility that Vietnamese constabulary forces are conducting maneuvers that indicate that their role is to crowd the seas. As IOJI reported, 12 VFRS vessels were deployed between January 2023 and August 2023 (IOJI, 2023a,b). Each deployed VFRS vessel continued its presence in the gray zone areas by staying between Indonesia’s EEZ and continental shelf line for approximately 2 weeks (IOJI, 2023b).

Actions taken by Vietnamese fishing vessels and the VFRS cause significant disadvantages for Indonesia. Indonesian fishermen lose that opportunity to utilize fishing resources in the North Natuna Seas due to the crowd of Vietnamese fleets in the gray zone areas. This violates the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) due to the Illegal, Unregulated, and Unreported Fishing (IUUF) occurring within Indonesia’s borders. It is not likely that Vietnamese officials are not aware of their activities in the North Natuna Seas, especially considering the involvement of VFRS within the waters, acting multiple times as a protector to the fishing fleets operating in those contested waters (Fadli, 2020; Sasmita, 2021; IOJI, 2022).

In making sense of this empirical puzzle, this article adopts the framework of maritime diplomacy. It argues regardless of the EEZ boundary agreement between Vietnam and Indonesia in 2022, Vietnam is persistent in displaying its effective occupancy in the gray zone areas as it is its strategy to adopt paragunboat diplomacy as its primary maritime diplomatic strategy. The following sections start with a framing of the crisis in 2023 under the maritime diplomatic framework and continue with evaluating future directions according to the author’s perspectives.

Vietnam’s utilization of fishing fleets and maritime fisheries surveillance vessels corresponds to the maritime diplomatic literature of paragunboat diplomacy. This term is used to represent a sea-based diplomatic strategy of state actors in which maritime constabulary forces (fishing militia, fisheries surveillance, coastguards, maritime paramilitary agencies, etc.) are utilized as a non-coercive alternative to navies (Le Mière, 2014). States refrain from using navies as civilian fleets; it advances the chances to de-escalate tensions while displaying effective occupancy in contested waters (Le Mière, 2014; Putra, 2023). The term “paragunboat diplomacy” was coined by Le Miere to showcase a rising trend of civilian fleets being deployed at sea for diplomatic purposes.

Vietnam’s introductions seem unorthodox, but this trend should not be taken for granted. This study argues that the continuous use of such maritime diplomatic strategies is carefully planned, corresponding to the maritime diplomatic literature on the evolution of maritime-based assets to further a state’s national interests. The management of international relations in the context of the North Natuna Seas is convoluted. This has been a center of political and geographic divide among Southeast Asian states, as there is a rising tendency to view the seas as containing untapped resources that may benefit Asian policymakers. As Le Miere argued, in such situations, states tend to utilize their maritime assets to further a diplomatic purpose (Le Mière, 2014).

Nevertheless, this differs from the conceptual framework of gunboat diplomacy used in naval studies during the World Wars. In gunboat diplomacy, the focus of analysis is the utilization of navies to achieve a particular diplomatic goal pre-determined by the state (Cable, 1994; Tarriela, 2018). It conducts coercive actions to compel adversaries (Mahan, 1898; Till, 2018, 2022). This study argues that instances of gunboat diplomacy are less relevant in contemporary affairs. The tensions between Vietnam and Indonesia at the North Natuna Seas can be comprehended by bridging a more contemporary understanding of maritime diplomacy, one that transcends discussions on navies by placing the maritime asset of civilian fleets at the core of its analysis.

As seen in the recent trends between January and August 2023, Vietnam has prioritized the strategies of intrusions by its fishing fleets and the VFRS. Their active presence and growing numbers in the gray-zone areas of the North Natuna Seas indicate a consistent pattern of maritime diplomatic strategy to display effective occupancy. As seen in Figure 1, with the VFRS conducting maneuvers that intentionally aim to be present in contested waters, Vietnam is employing what this article terms paragunboat diplomacy. The use of civilian fleets allows for an innocent strategy of crowding the seas to take place. Because of that, the rising number of fleets intruding into Indonesian waters only represents Vietnam’s strong intent to refrain from utilizing navies as its primary maritime diplomatic strategy and prefer non-escalating maritime assets such as fishing fleets and fisheries surveillance vessels.

At this point, an essential question is why Vietnamese officials implement this strategy. As can be seen in Figure 1, the gray zone areas between Indonesia’s EEZ boundary line and its continental shelf are vast. This study argues that Vietnam is attempting to solidify its sovereign claims in the contested waters by making its maritime assets present in those vast seas. As the maritime diplomacy literature explains, a significant reason why states adopt paragunboat diplomacy is that it allows a display of de facto sovereignty (Le Mière, 2011; Le Mière, 2014). This is especially relevant post-2022, as Vietnam is expected to halt its intrusions with the conclusion of the EEZ boundary lines between Vietnam and Indonesia. However, on the contrary, this has not been the case. The lack of precise coordinates indicating the EEZ boundary line may be a substantial cause of this strategy. However, it is predicted that this is Vietnam’s grand strategy to display effective occupancy in contested waters. Therefore, having explicit EEZ boundary line coordinates would not halt Vietnam’s intentions to adopt maritime diplomatic strategies that indicate its presence at sea.

A second reason why paragunboat diplomacy is essential for Hanoi’s maritime diplomatic strategy is due to the tactical flexibility it offers. In the past, using navies offered a strategic solution to compelling adversaries. However, the use of maritime diplomatic strategies aimed to compel is no longer perceived as ideal. Another can easily protest states if navies are utilized to conduct unfriendly maneuvers at sea. Paragunboat diplomacy offers a better alternative in the context of maritime diplomacy. By utilizing fishing fleets and fisheries surveillance vessels, Vietnam is deterring any possibility of escalated conflicts. This is due to the military flexibility it has by using such civilian fleets, compared to the static strategies that could be utilized with the use of navies. This is important for Vietnam, a claimant state to the South China Sea. By paragunboat diplomacy, Vietnam can escalate and de-escalate tensions in seconds. The continuous presence of the VFRS in the first 8 months in the North Natuna Seas indicates that Vietnam officials are comfortable with their positioning in those gray zone areas. There is no urgency to claim contested waters boldly, but being present in those seas shows that Vietnam is not letting go of its claims. This is a vital component of the strategic reason why paragunboat diplomacy is ideal for Vietnam.

In alignment with the tactical flexibility is also Vietnam’s defensive posturing generated with the use of fishing fleets and fisheries surveillance vessels. The use of navies tends to generate a coercive intent among adversaries, and its utilization tends to be interpreted as having offensive intentions. Using civilian fleets, Vietnam displays defensive posturing to dominate with its actions at sea. Defensive as its fleets do not contain offensive weaponry that may be interpreted as having offensive intentions. In addition, with the use of civilian maritime assets, instances of escalation are doubtful. For the fishing fleets captured by Indonesian officials, most have been released with a warning, a fine, or the worst-case scenario being the sinking of those illegal ships (Purba, 2019; KKP, 2020; Aprian, 2021; Bakamla, 2021). For other civilian vessels utilized, the possibility of escalation only consists of scenarios in which ships ram one another or the capturing of boats. With the fact that these vessels do not comprise a high-end armory for offensive purposes, it is less likely that escalation of conflict will occur. This is contrary to the worst-case scenario if Vietnam deploys gunboat diplomacy in Indonesia’s North Natuna Seas.

With the framing of the recent crisis involving intrusions into Indonesia’s North Natuna Seas under paragunboat diplomacy, this perspective contributes to the growing literature on the maritime diplomacy of civilian fleets. Le Miere first termed paragunboat diplomacy to showcase the rising number of maritime paramilitaries utilized as a foreign policy tool in the past decade (Le Mière, 2011). Following that, Basawantara also used this term to make sense of the non-military forces being used by Indonesia (Basawantara, 2020). The findings of this study correspond to a previously published article discussing Vietnam’s maritime diplomatic strategies vis-à-vis the North Natuna Seas (Darwis and Putra, 2022; Putra, 2023). Recent developments indicate that Vietnam’s paragunboat diplomacy is employed not because of a lack of legal instruments to clarify the EEZ boundary lines between the two nations but because Therefore, this study confirms that despite recent agreements, the strategy of intrusions by Vietnamese fishing fleets and the VFRS is currently taking place and is predicted to continue, as it is part of Vietnam’s overall maritime diplomatic strategy to display effective occupancy in contested waters.

The empirical puzzle raised for this article is the growing instance of intrusions conducted by Vietnam fishing fleets and VFRS in the early months of 2023. This is problematic as Indonesia and Vietnam recently concluded the 12-year negotiation to finalize the EEZ boundary line between the two states, which has been a center of contestation in the past decade. Contrary to existing predictions, Vietnam has continued its past strategy of deploying its maritime constabulary forces in the gray zone areas of Indonesia’s North Natuna Seas.

This article argues that in comprehending this recent development, consultation with the maritime diplomatic framework can reveal important insights. Within this literature, the use of maritime constabulary forces in gray zone areas is interpreted as a state’s intention to showcase effective occupancy over areas of contestation. Consequently, Vietnam’s recent maneuvers at sea between January 2023 and August 2023 indicate that it is attempting to display effective occupancy by deploying its civilian fleets. Within the literature, this is understood as paragunboat diplomacy. This form of diplomacy utilizes civilian maritime constabulary fleets (in the case of Vietnam, including fishing fleets and the VFRS). It intentionally operates in gray zone areas to display effective occupancy. A series of limited-coercive maneuvers are expected, as these maritime assets are utilized similarly to what academics term gunboat diplomacy during the past World Wars. A differentiating component, however, is that military fleets are not involved in countering harmful reactions to Hanoi.

The future possibilities in the gray zone areas of the North Natuna Seas seem grim. The recent developments show that the core issue between Vietnam and Indonesia in the gray zone areas relates to Vietnam’s maritime diplomatic intentions of effectively occupying areas of contestation. Therefore, despite concluding the 2022 EEZ boundary line, Vietnam cannot be expected to abandon its intrusions through its maritime constabulary forces. This is since Vietnam is attempting to be consistent with its maritime diplomatic strategy to crowd the seas using civilian fleets. Until the writing of this article, neither state had formally announced the coordinates of the EEZ lines, which could be interpreted as a reason why intrusions took place months after the conclusion of the EEZ agreement. However, this article finds that possibility highly unlikely, as these recent developments, if framed in maritime diplomatic contexts, indicate a long-term projection plan among Hanoi policymakers in the North Natuna Seas to continue its intrusions to display effective occupancy.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

BP: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization.

The author declares that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aprian, D. (2021). Curi Cumi di Laut Natuna Utara, 5 Kapal Nelayan Vietnam Ditangkap KKP Halaman all—Kompas.com, Kompas. Available at: https://regional.kompas.com/read/2021/04/12/143042178/curi-cumi-di-laut-natuna-utara-5-kapal-nelayan-vietnam-ditangkap-kkp?page=all (Accessed January 9, 2022).

Azad, T. M., Haider, M. W., and Sadiq, M. (2022). Understanding gray zone warfare from multiple perspectives. World Affairs 186, 81–104. doi: 10.1177/00438200221141101

Basawantara, A.A.G. (2020). Countering China’s Paragunboat Diplomacy in the South China Sea: The Responses of the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia. President University. Available at: http://repository.president.ac.id/xmlui/handle/123456789/4770 (Accessed February 17, 2023).

Darwis,, and Putra, B. A. (2022). Construing Indonesia’s maritime diplomatic strategies against Vietnam’s illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing in the north Natuna Sea. Asian Affairs 49, 172–192. doi: 10.1080/00927678.2022.2089524

Fadli, (2020). Bakamla nabs Vietnamese fishing boat crew after cat and mouse game in Natuna, The Jakarta Post. Available at: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/07/27/bakamla-nabs-vietnamese-fishing-boat-crew-after-cat-and-mouse-game-in-natuna.html (Accessed June 24, 2021).

Giang, N.K. (2018). Vietnam’s response to China’s militarised fishing fleet | East Asia Forum, East Asia Forum. Available at: https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2018/08/04/vietnams-response-to-chinas-militarised-fishing-fleet/ (Accessed February 16, 2023).

Giang, N.K. (2022). The Vietnamese Maritime Militia: Myths and Realities, RSIS. Available at: https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/idss/ip22040-the-vietnamese-maritime-militia-myths-and-realities/?doing_wp_cron=1698232906.2380630970001220703125 (Accessed October 25, 2023).

IOJI (2022). Illegal Fishing Threats in The North Natuna Sea By Vietnamese Fishing Boats 2021, Indian Ocean Justice Initiative. Available at: https://oceanjusticeinitiative.org/2022/03/20/illegal-fishing-threats-in-the-north-natuna-sea-by-vietnamese-fishing-boats-2021/ (Accessed April 9, 2022).

IOJI (2023a). Analisis Gangguan Keamanan Laut Di Wilayah Perairan Dan Yurisdiksi Indonesia Periode April Hingga Agustus 2023, Indonesia Ocean Justice Initiative. Available at: https://oceanjusticeinitiative.org/2023/12/29/analisis-gangguan-keamanan-laut-di-wilayah-perairan-dan-yurisdiksi-indonesia-periode-april-hingga-agustus-2023/ (Accessed January 22, 2024).

IOJI (2023b). Threats to maritime security in Indonesian waters Period January to March 2023. Jakarta.

Jennings, R. (2021). Analysts: Vietnam Expanding Fishing Militia In South China Sea, VOA. Available at: https://www.voanews.com/a/east-asia-pacific_analysts-vietnam-expanding-fishing-militia-south-china-sea/6205729.html (Accessed October 25, 2023).

KEMLU (2022). Indonesia, Vietnam to Enhance Bilateral, Regional Cooperations, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Republic of Indonesia.

KKP (2020). KKP Tangkap Lagi 2 Kapal Asing, Kali Ini di Samudera Pasifik, Kementerian Kelautan dan Perikanan Republik Indonesia. Available at: https://kkp.go.id/artikel/23700-kkp-tangkap-lagi-2-kapal-asing-kali-ini-di-samudera-pasifik (Accessed June 24, 2021).

Le Mière, C. (2011). Policing the waves: maritime paramilitaries in the Asia-Pacific. Survival 53, 133–146. doi: 10.1080/00396338.2011.555607

Mahan, A. T. (1898). The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company.

McLaughlin, R. (2022). The law of the sea and PRC gray-zone operations in the South China Sea. Am. J. Int. Law 116, 821–835. doi: 10.1017/AJIL.2022.49

Ormsbee, M. H. (2022). Gray dismay: a strategy to identify and counter gray-zone threats in the South China Sea. Small Wars J. 1.

Parameswaran, P. (2019). The Old Challenge in the New Indonesia-Vietnam South China Sea Clash—The Diplomat, thediplomat. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2019/05/the-old-challenge-in-the-new-indonesia-vietnam-south-china-sea-clash/ (Accessed January 5, 2022).

Purba, D.O. (2019). Ini Jumlah Kapal yang Ditenggelamkan Susi Selama Menjabat Menteri Kelautan dan Perikanan, Kompas. Available at: https://regional.kompas.com/read/2019/10/07/06122911/ini-jumlah-kapal-yang-ditenggelamkan-susi-selama-menjabat-menteri-kelautan?page=all (Accessed June 24, 2021).

Putra, B. A. (2023). Rise of constabulary maritime agencies in Southeast Asia: Vietnam’s Paragunboat diplomacy in the north Natuna seas. Sociol. Sci. 12:1–15. doi: 10.3390/socsci12040241

Sasmita, A. I. (2021). Diplomasi Maritim Indonesia dalam Kasus Illegal Fishing oleh Nelayan Vietnam Tahun 2018-2019. J. Hubungan Int. 14, 81–94. doi: 10.20473/JHI.V14I1.21645

Tarriela, J.T. (2018). Japan: From Gunboat Diplomacy to Coast Guard Diplomacy, The Diplomat. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2018/05/japan-from-gunboat-diplomacy-to-coast-guard-diplomacy/ (Accessed September 20, 2023).

Till, G. (2022). Order at sea: Southeast Asia’s maritime security, Lowy Institute. Available at: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/order-sea-southeast-asia-s-maritime-security (Accessed February 16, 2023).

Yeo, M. (2023). How a new Vietnam-Indonesia deal will affect South China Sea disputes, Defense News. Available at: https://www.defensenews.com/smr/defending-the-pacific/2023/02/13/how-a-new-vietnam-indonesia-deal-will-affect-south-china-sea-disputes/ (Accessed February 16, 2023).

Keywords: North Natuna Seas, Vietnam, maritime constabulary forces, exclusive economic zone, maritime borders

Citation: Putra BA (2024) Testing Indonesia’s decisiveness: Vietnam’s continuous presence in the North Natuna Seas. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1375198. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1375198

Received: 23 January 2024; Accepted: 23 April 2024;

Published: 06 May 2024.

Edited by:

Ilia Murtazashvili, University of Pittsburgh, United StatesReviewed by:

Miguel Borja Bernabé-Crespo, Autonomous University of Madrid, SpainCopyright © 2024 Putra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bama Andika Putra, YmFtYS5wdXRyYUBicmlzdG9sLmFjLnVr

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.