- Department of Political Science, Radboud University Nijmegen, Nijmegen, Netherlands

Democratic legitimacy is essential for democratic stability, as democracies rely on citizen support to survive. However, perceived legitimacy gaps can also be an important catalyst for change and potential democratic renewal, begging the question when challenges to legitimacy become problematic for democratic survival. Easton distinguished between citizen support for political authorities and the political system, and argued that if support for political authorities declined, such declining support could either be resolved by the current political authorities changing course, or by citizens electing new political authorities at the next elections. However, if dissatisfaction with political authorities would not be resolved, lacking support had the potential to eventually “spill-over” and undermine support for the political system as a whole. In most empirical research on legitimacy, the assumption is that such “spill-over” is visible only if declining levels of political trust and satisfaction with democracy start to undermine support for democracy as a political system. In this paper, we argue that “spill-over” can also manifest in a different way: through the politicization of political support. When politics is no longer (only) about substantive policy decisions, but rather (increasingly) about the system itself, agreement on the rules of the game, or even on democracy as “the only game in town”, is no longer self-evident. In this paper we further develop our theoretical argument about the connection between legitimacy and politicisation, and argue that European democracies appear to experience growing politicization of political support, in terms of the association of political support with citizens’ substantive issue positions and voting behaviour. The paper demonstrates empirical evidence of such politicization of political support in 17 European democracies with European Social Survey data from 2002–2022. The paper concludes by reflecting on the implications of the politicization of political support for democratic stability and renewal.

1 Introduction

Democratic legitimacy is essential for democratic stability and survival (Claassen, 2019). If democracy is not seen as the “only game in town” by citizens and elites, new democracies will have difficulties to consolidate and older democracies may be at risk of deconsolidation (Przeworksi 1991; Linz and Stepan, 1996; Foa and Mounk, 2016). However, not all political discontent is equally problematic for democratic survival. In his work on political support, Easton (1965, 1975) distinguished between citizen support for the political authorities and the political system, and argued that if support for political authorities declined, such declining support could either be resolved by the current political authorities changing course, or by citizens electing new political authorities at the next elections. Hence, representative democracies have an in-built sanctioning mechanism in the form of elections, to resolve dissatisfaction with political authorities. However, if dissatisfaction with political authorities would not be resolved, according to Easton such lacking support had the potential to eventually “spill-over” to support for the political system, undermining support for the political system as a whole.

In most empirical research on legitimacy, the assumption is that “spill-over” is visible when declining levels of support for political authorities and institutions, often measured as political trust and satisfaction with the way democracy works in practice, start to undermine support for democracy as an ideal political system (Norris, 1999, 2011; Dalton, 2004; Thomassen et al., 2017; Van Ham et al., 2017). However, empirically, there is very limited research into whether and how such spill-over actually occurs. While panel-data in European democracies often includes measures of political trust (Devine and Valgarðsson, 2023), or satisfaction with the way democracy works (Kolln and Aarts, 2021), similar data for support for democracy as the preferred system is not available, making causal identification of spill-over within individuals difficult.1 In addition, high levels of support for democracy as an ideal political system are often taken as an indication that spill-over has not happened, and support for democracy remains strong. However, research has demonstrated that citizens have different visions of democracy (Ferrin and Kriesi, 2016), including illiberal, technocratic and populist ones (Zorell and van Deth, 2020; Zaslove and Meijers, 2023), that citizens can support democratic and authoritarian systems simultaneously (Wuttke et al., 2022), and that citizens are quite willing to trade-off their support for democracy for partisan or policy gains under certain circumstances (Graham and Svolik, 2020; Krishnarajan, 2023). Hence, spill-over may manifest in different ways: people dissatisfied by the way democracy works may shift their visions of democracy towards more illiberal ones, they may increase their support for authoritarian leadership, or they may become more open towards trading-off democratic values for other benefits. None of these types of spill-over would become visible in declining support for democracy as an ideal political system. Indeed, the fact that democratic backsliding has occurred in democracies where support for democracy as an ideal political system was very high suggests spill-over may manifest empirically in different ways than previously theorized.

In this paper, we argue that “spill-over” can also manifest through the politicization of political support. Politicization occurs when a previously unpolitical issue enters the domain of mass politics (Hooghe and Marks, 2009), which in case of political support would mean that the political system itself becomes the object of political contestation. Concretely, we expect that increasing levels of dissatisfaction with political authorities and institutions, when not resolved, may eventually lead these institutions and the political system in which they operate to themselves become publicly and politically contested. Political competition then no longer revolves (only) around substantive policy decisions, but rather (increasingly) around the legitimacy of the system itself, meaning that agreement on democracy as “the only game in town” is no longer self-evident.

In the next section, we further elaborate on what it means when perceived legitimacy—or political support—becomes politicized, and why we expect European democracies to experience growing politicization of political support, in terms of the association of political support with citizens’ substantive issue positions and voting behaviour. The subsequent sections then outline the data and methods used to test politicization empirically, and demonstrate empirical evidence of the politicization of political support in 17 European democracies with European Social Survey data from 2002–2022. The paper concludes by reflecting on the potential consequences of the politicization of political support for democratic stability and renewal.

2 Legitimacy, spill-over, and democratic stability

Building on earlier theoretical work on legitimacy (Dahl, 1956; Easton, 1965; Gilley, 2006; Tyler, 2006), we define legitimacy as the normative justification of political authority (Van Ham and Thomassen, 2012; Thomassen and Van Ham, 2017). In this sense, legitimacy refers to “the belief that authorities, institutions and social arrangements are appropriate, proper and just” (Tyler, 2006: 376), or “a belief in the rightness of the decision or the process of decision making” (Dahl, 1956: 46), and “that it is right and proper to accept and obey the authorities and to abide by the requirements of the regime” (Easton, 1965: 451). As Easton further sets out, legitimacy beliefs thus “reflect the fact that in some vague or explicit way [a person] sees these objects as conforming to his own moral principles, his own sense of what is right and proper in the political sphere.” (Easton, 1965: 451).2 Legitimacy judgments by citizens thus require a comparison between their own normative principles of what constitutes “just” political authority, and their evaluations of the way “real-existing” authorities are functioning in practice. If norms and reality match, authority will be considered legitimate, and if norms and reality deviate, authority will be considered to suffer from a legitimacy “gap” or “deficit” (Norris, 2011).3

However, citizens have different normative ideals about what “ideal” democracy should be (Dalton et al., 2007; Ferrin and Kriesi, 2016). Citizens also have different experiences with democracy and therefore different evaluations of how “real” democracy works in practice. This implies that it is unlikely that ideals and reality will match for all citizens all the time, and that perceived legitimacy gaps or deficits are in fact, part and parcel of democracy. As Markoff (2011) describes, it is in fact precisely the distance between ideals and practice that historically has driven calls for improving and deepening democracy, making legitimacy deficits a “recurrent catalyst to change” (Markoff, 2011: 269).4 Therefore, in a democracy, it is likely that the legitimacy of political authority will always be contested by at least some citizens. As democracy is continually evolving and facing new challenges, it is also likely that this contestation is an ongoing process, as some legitimacy deficits are resolved and new legitimacy deficits emerge.

If there are always some citizens who identify legitimacy gaps, either because they have different democratic ideals in mind, or because they find democracy is not living up to its promises in practice, or both, when do legitimacy gaps become problematic for democratic stability?

In empirical research on perceived legitimacy gaps by citizens, there appear to be three, related, assumptions.

First, dissatisfaction with the political authorities is considered to be less problematic than dissatisfaction with the political system as a whole. In most empirical research on legitimacy, legitimacy beliefs by citizens are operationalised as political support for political authorities, political institutions, and the political system as a whole.5 Here, different objects or levels of political support are identified, ranging from the political authorities (i.e., the government currently in power), to the political institutions (i.e., the parliament, the judiciary, etc.) to the political system (i.e., democracy) (Norris, 1999, 2011; Dalton, 2004; Thomassen and Van Ham, 2017).6 As briefly mentioned in the introduction, the assumption is that low political support for political authorities may not necessarily present an immediate challenge to the stability of the political system as a whole, as political authorities can be replaced at elections (Easton, 1965; Kaase and Newton, 1995; Dalton, 2004). Low support for political institutions is already more problematic, but even here, support can potentially be regained by improving the performance or responsiveness of the specific institution that is considered wanting by citizens (Dalton, 2004; Norris, 2011). However, when there is low support for the political system as a whole, addressing the legitimacy deficits that citizens perceive may become more complex and require a complete overhaul of the democratic system. Dissatisfaction at the level of the political system therefore appears most likely to challenge democratic stability (Claassen, 2019; Claassen and Magalhães 2022).

Second, the source of dissatisfaction is considered to be important. As Easton’s discussion of specific versus diffuse support also indicated, if low political support is due to citizens’ being dissatisfied with the way authorities are functioning in practice, this may be less problematic than when dissatisfaction is due to their normative expectations not being met. Citizens may be willing to accept sub-standard performance by political authorities, at least temporarily, if they believe that authorities are following “normatively just” decision-making procedures. Indeed, the empirical literature on outcome acceptance and procedural fairness suggest that citizens are willing to accept outcomes that they themselves are not happy with as long as they believe decision-making procedures have been fair (Tyler, 2006; Magalhães, 2016; Werner and Marien, 2022). However, as Easton also warned, in practice the two are related: if citizens’ consider authorities to not function well for a long time, and democratic decision-making procedures such as elections are not able to resolve this dissatisfaction by bringing a new government to power that does resolve their concerns, low specific support may “spill-over” and also end up undermining citizens’ normative commitment to democracy (Claassen and Magalhães, 2022).

Third, the duration of dissatisfaction is considered to be important. As the above discussion already indicates, lacking political support appears to be especially problematic for democratic stability when it becomes persistent and does not get resolved (Easton, 1965; Kaase and Newton, 1995; Dalton, 2004; Norris, 2011; Van Ham and Thomassen, 2012). Thus, lacking political support is not problematic when it is temporary, and can get resolved through either governments’ changing course, voting in a new government in elections, or institutional and democratic reform. But when dissatisfaction with political authorities becomes endemic and structural, it may spill-over to higher levels of political support, undermining support for political institutions and the political system as a whole. As Dalton asks: “how long do citizens continue to like the game of democratic politics if they have lost confidence in the players and even how the game of democratic politics is now played?” (Dalton, 1999: 72).

Clearly, the three assumptions are related. In any of these scenarios, it is thought lacking support for political authorities, when not resolved, may spill over to support for political institutions and ultimately the political system. Thus, the more people experience lacking political support and the longer this lasts, the more likely it is that spill-over will occur and people will eventually withdraw their support for the democratic political system as a whole.

As argued in the introduction, both data limitations and conceptual issues make it difficult to empirically establish such spill-over effects. However, we argue that “spill-over” can also manifest in a different way: through the politicization of political support. This argument is developed in the next section.

3 The politicization of political support

Clearly, the assumptions in empirical research on the relation between citizens perceptions of legitimacy gaps and democratic stability point at the importance of resolving perceived legitimacy gaps. Ideally, citizens who feel democracy does not live up to their standards will point this out and seek to mobilise political parties and other citizens, leading to the perceived legitimacy gap to be addressed, and perhaps in the process inspire other, new groups of citizens, with new demands (Markoff, 2011).

A key institution of representative democracy to allow for citizen influence and resolve such perceived legitimacy gaps are elections. Elections function as a sanctioning mechanism, that enable citizens to hold their governments to account, which also creates incentives for those governments to be responsive to what citizens want (Powell, 2000). This provides a mechanism for citizens who are dissatisfied with how the political system is working to point out the legitimacy gaps they perceive, to mobilize around these issues in protests, media or by getting political parties involved, and either achieve policy change by pressuring governments who want to avoid electoral defeat to change course, or by voting governments out of office. Therefore, the core idea of representative democracy is that it has institutionalised mechanisms to resolve dissatisfaction through “normal” politics: for instance, by voting in new politicians or parties or by pressuring existing ones to be more responsive or to explain why certain decisions were made.

Paradoxically however, resolving perceived legitimacy gaps first requires them to become politicized. Legitimacy gaps need to be noticed and become part of the public debate in order to be picked up by political actors and get resolved. Politicization occurs as a result of “the demand for, or the act of, transporting an issue into the field of politics, making previously unpolitical matters political” (Zürn, 2019: pp. 977–978). When a specific political issue is politicized, it enters the domain of mass politics (Hooghe and Marks, 2009, p. 18) and becomes the object of public contestation. Politicization applies to newly emerging political issues, but we argue that it can also apply to political support itself. In this case, we would expect that political support itself becomes part of politics: as political parties seeking to mobilize disillusioned voters may campaign not only on substantive policy positions, but also on distrust of political institutions and promises to improve, fix, or overhaul the system. In these situations, positions regarding the political system and its institutions become one of the issues over which electoral competition is fought, and thus become related to political competition. Empirically, we would expect politicization of political support to be visible as an increasing association of political support with citizens’ substantive policy positions, and, to the extent that there are political parties who express this discontent, also with voting behaviour.

The politicization of political support is a manifestation of “spill-over”, as it is the political system itself that is being contested: citizens become divided in their support for the political system, and this divide aligns with existing political divides. Yet, with regard to the implications of such “spill-over” for democratic stability, it is crucial to establish whether the politicization of political support is structural or temporary. Since legitimacy gaps need to be politicized in order to be resolved, we would expect politicization to increase when legitimacy gaps become part of the public debate and political agenda and decrease if and when they are resolved. Empirically then, the degree of politicization of political support could vary over time, as legitimacy gaps become politicized and then get resolved.

However, we expect that the politicization of political support may have become a more structural phenomenon in Western democracies, for three reasons. First, the resolution of legitimacy gaps hinges on government being able to resolve them. The question is to what extent governments in European democracies have been able to solve or address perceived legitimacy gaps. The increasingly complex and often transnational issues that national governments need to deal with, such as migration and climate change, combined with the increasingly limited discretion of national governments due to shifts in power to transnational governance such as the EU as well as to (international) markets, may well limit the capacity of national governments to resolve legitimacy gaps (Mair, 2009, 2023).

Second, while globalization constrains national governments, it at the same time transforms public opinion by creating new demands and grievances among the mass public. Increasing pressure on traditional left-wing achievements such as the national welfare state generates dissatisfaction among citizens with strong left-egalitarian views, while open borders and an increasing influx of migrants unsettles those with culturally right-wing preferences. Thus, concerns related to globalization processes transform both the economic and cultural dimensions of the political space (Kriesi et al., 2008). To the extent that governments cannot adequately respond to these concerns, specific groups of citizens may experience structural legitimacy gaps in terms of their substantive representation (Hillen and Steiner, 2020; Hakhverdian and Schakel, 2022).

Third, the resolution of legitimacy gaps depends on political parties that are willing to address legitimacy gaps. The rise of radical left and right political parties in most European party systems that mobilize on political distrust appears to have succeeded in putting perceived legitimacy gaps on the political agenda. Yet, not only do they have limited access to government and therefore little possibility to translate their programmes into policy—radical parties may also choose to keep mobilizing on political discontent even after being elected into parliament as a more profitable electoral strategy in the long run (Rooduijn et al., 2016). Therefore, while politicization of political support may certainly vary in the short run, we expect a long-term trend of increasing politicization of political support in European democracies.

Based on this discussion, we therefore expect to find the following empirical patterns in terms of the politicization of political support:

H1. The association of citizens’ political support with their issue positions and vote choice has increased over time in Western democracies.

H2. The association of citizens’ political support with their issue positions and vote choice varies over time within countries.

In the subsequent sections, we investigate to what extent there is indeed evidence of increasing politicization of political support, both in terms of issue positions and vote choice.

4 Data and methods

The expectations about the politicization of political support are tested with data on political support in 17 European democracies using European Social Survey (ESS) data from 2002–2022. We test whether political support has become increasingly associated with citizens’ substantive issue positions and voting behaviour in this period.

As indicators of political support, we use two dependent variables: trust in parliament and satisfaction with democracy. Trust in parliament is measured on an 11-point scale ranging from “No trust at all” (0) to “Complete trust” (10) in the ESS. Satisfaction with the way democracy works in ones’ country is measured on an 11-point scale ranging from “Extremely dissatisfied” (0) to “Extremely satisfied” (10).

As measures of citizens’ substantive issue positions, we use three independent variables: citizens’ positions on EU unification, income differences, and immigration, to reflect both the economic and cultural dimensions of citizen’s substantive policy positions in Europe (Kriesi et al., 2008).

Citizens’ positions on European unification are measured by asking respondents whether they think “European unification should go further or already has gone too far”. Answer categories on this question vary on an 11-point scale from “Unification has already gone too far” (0) to “Unification should go further” (10).

Positions on income differences are measured by the question to what extent respondents agreed or disagreed on the statement: “Government should reduce differences in income levels”, with answer options ranging on a 5-point scale from “Agree strongly” (1) to “Disagree strongly” (5). This variable coding was reversed, so that higher scores indicate positions that are more in favour of governments reducing income differences.

Finally, citizen’s positions on immigration were measured by the extent to which they agreed with the statement: “Immigrants make my country a worse or better place to live”, with answers on an 11-point scale ranging from “Worse place to live” (0) to “Better place to live” (10).7

As measure for citizens’ vote choice, we use one independent variable: the question what party respondents voted for in the last national election. Only political parties for which 5 or more respondents indicated to have voted are included in the analysis.

The sample includes all democracies in Western Europe where the ESS has been held for a minimum of 3 waves, resulting in a total of 17 countries.8

First, to model the association between political support and issue positions over in time in each country, we run multi-level linear regression models for each country, with individual respondents (level 1) clustered within years in which the survey was held (level 2). To test whether the association between political support and issue positions has changed over time, the analyses include an interaction effect with the year in which the survey was held. This interaction effect allows us to model to what extent the association between political support and issue positions is subject to change over time. Analysing all countries separately, rather than in a pooled model, allows us to gauge to what extent these over-time developments are different across countries. As the main purpose of the analyses is to map changes over time in the association between political support and issue attitudes, the analyses do not include control variables but run simple bivariate models, followed by models with year of survey as an interaction variable (Achen, 2005). The results are presented in the results section in marginal effects graphs, all models are presented in the Appendix to the paper.

Second, to model the association between political support and vote choice, we analyse the relation between political support and vote choice separately for each year in each country, using linear regression models for each year and country. Since the political parties that respondents can vote for in elections change over time, the party choice set changes to such an extent that separate analyses are called for. Therefore, instead of testing whether the association between political support and vote choice changes over time, the analysis focuses on whether the proportion of variance in political support that is explained by vote choice changes over time. The results are visualized in the next section by graphs mapping variance explained per survey-year for each country. All models underlying the graphs are again presented in the Appendix to this paper.

5 Empirical evidence: politicization of political support?

This section evaluates whether there is empirical evidence for the increasing politicization of political support. If there is politicization of political support, this should become apparent in increasing associations over time between political support and issue positions, as well as between political support and vote choice.

5.1 Political support and issue positions

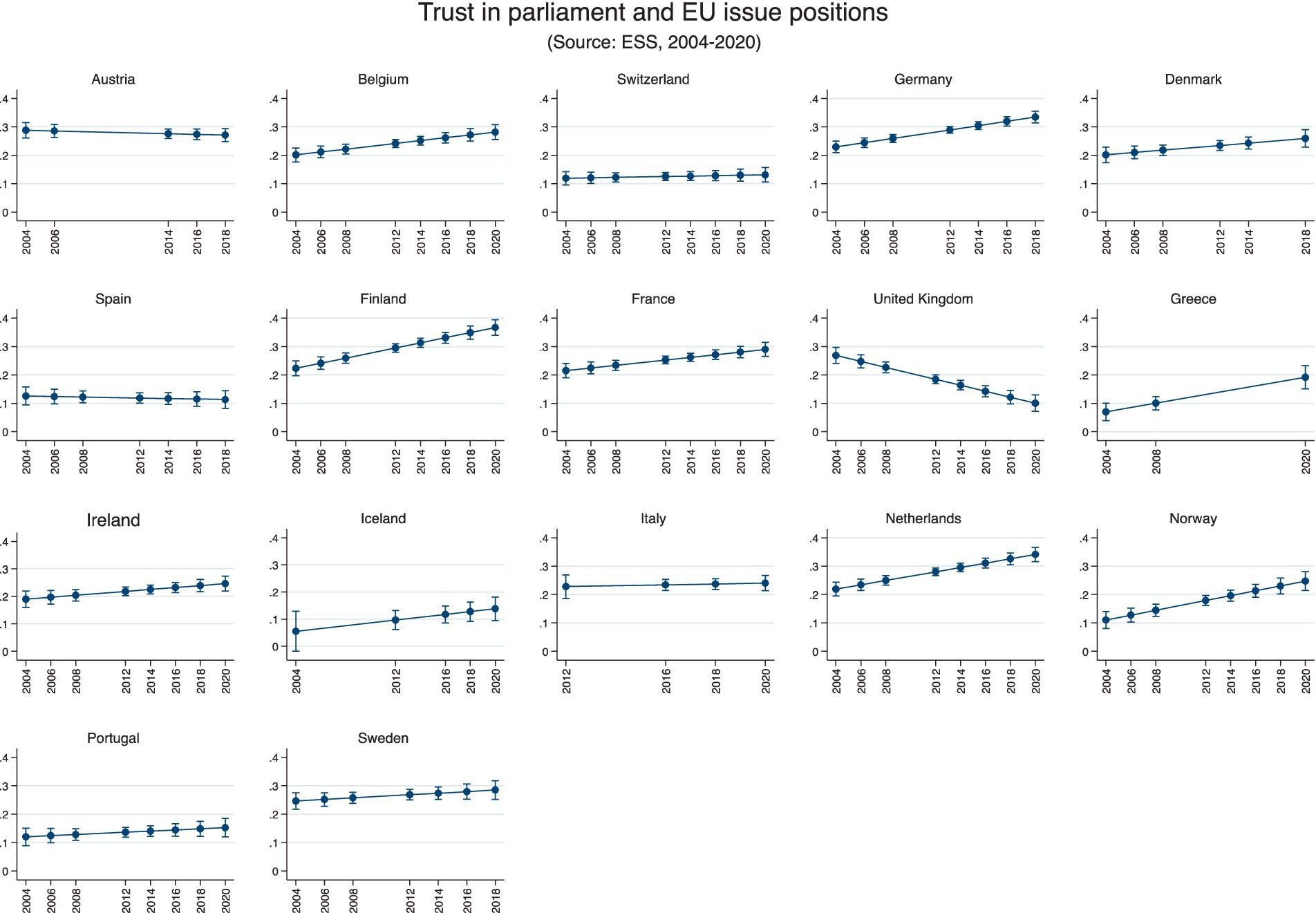

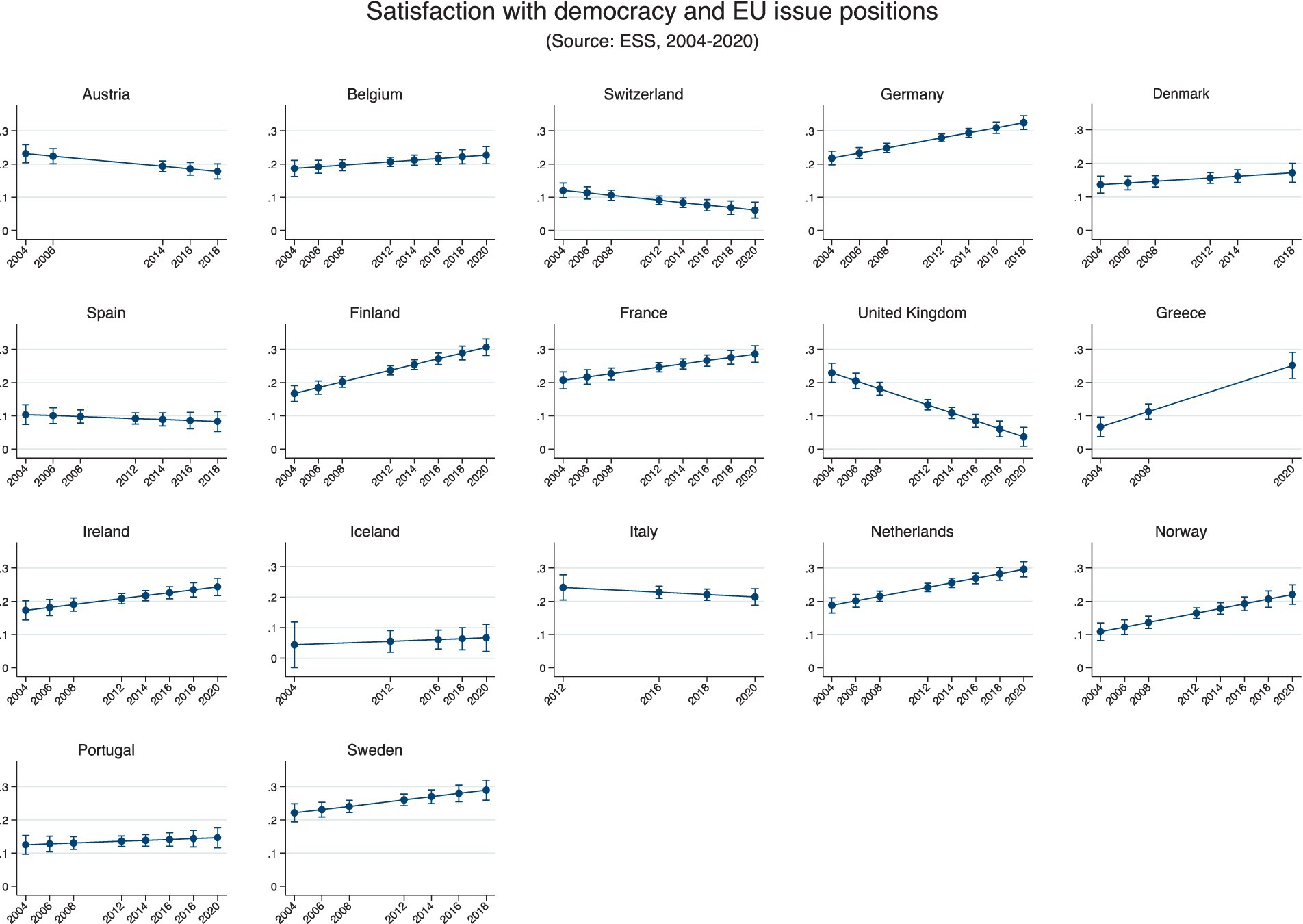

Starting with issue positions, Figures 1, 2 show the changes over time in the association between positions on EU unification and trust in parliament and satisfaction with democracy, respectively.

EU issue positions appear to have become significantly more strongly associated with trust in parliament in the majority of countries in our sample. As Figure 1 shows, in all 17 countries higher support for EU unification is associated with higher levels of trust in parliament (see also the Appendix for the models underlying results presented in Figure 1). In 14 out of 17 countries, this association has strengthened over time, indicating politicisation, in 10 of which significantly. There is variation in how strong the increase is, ranging from strong increases in countries like Finland, Norway, Germany and the Netherlands, to more moderate increases in countries like Ireland and Denmark. The 4 countries where trust and EU positions are associated but this relation does not become stronger over time, are Italy, Portugal, Spain and Switzerland.

In only 3 countries does the association appear to have weakened over time, of which only in one significantly. The only country where EU issue positions and trust in parliament have become less strongly associated is the UK, which could have to do with Brexit resolving some of the frustration with the EU among some voters, while simultaneously decreasing trust among pro-EU voters, further weakening the association. Overall however, in terms of EU issue positions there seems to be clear evidence of a growing association to political trust in quite a substantial number of countries.

Turning to satisfaction with democracy, Figure 2 shows how the association of EU issue positions with satisfaction with democracy has developed over time within the 17 countries in our sample. The association between support for EU unification and satisfaction with democracy is positive in all countries, and has strengthened over time in 12 out of the 17 countries in our sample (and significantly so in 9 countries). The association has weakened over time in 5 countries, of which in 3 countries significantly so. There is however quite some variation in how strong politicization is: with strong increases in the association between EU issue positions and satisfaction with democracy in Greece, Finland, Germany, Norway and the Netherlands; but a very sharp decrease in the UK.

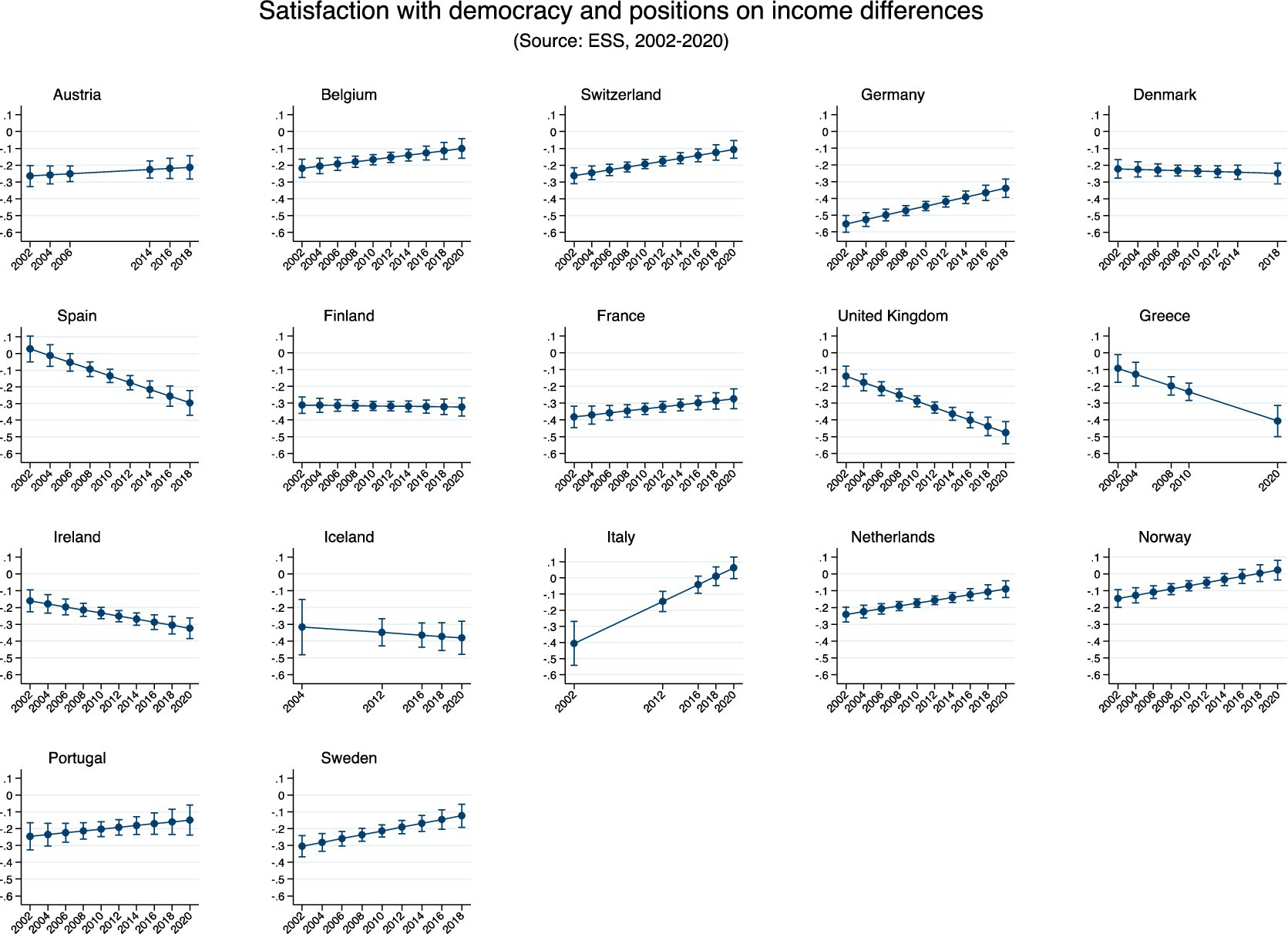

Turning to income differences, Figures 3, 4 show the results for models predicting trust in parliament and satisfaction with democracy by respondents’ positions on income differences.

Higher scores indicate respondents are more in favour of governments reducing income differences, and a positive coefficient therefore means people who are more in favour of reducing income differences are more trusting. However, as Figure 3 shows, the association between positions on income differences and political trust is negative in all countries: respondents who are more in favour of governments reducing income differences tend to have lower levels of trust in parliament.

Figure 3 shows how the association between positions on income differences and trust in parliament has changed over time in each country. If the coefficients become more negative over time, this would be evidence of increasing politicization. This appears to have occurred in 8 of the 17 countries in our sample, though only significantly so in 3 of these (United Kingdom, Ireland and Greece). In 9 out of 17 countries politicization has in fact decreased, with the association between trust in parliament and positions on income differences becoming weaker, though these trends are significant in only 5 countries.

Considering the effects of positions on income differences on satisfaction with democracy, Figure 4 shows an equally varied picture. Also here, associations are negative in all countries: respondents who are more in favour of government action to reduce income differences tend to be less satisfied with democracy. Yet, this association becomes stronger over time in only 7 countries of the 17 in our sample, and only significantly so in 4 countries. In most countries, 10 out of 17, politicization decreases over time (and in 8 significantly so). Clearly, when it comes to positions on income differences the findings are varied: increasing politicization in some countries such as the United Kingdom, Spain and Greece, and decreasing politicization in most other countries.

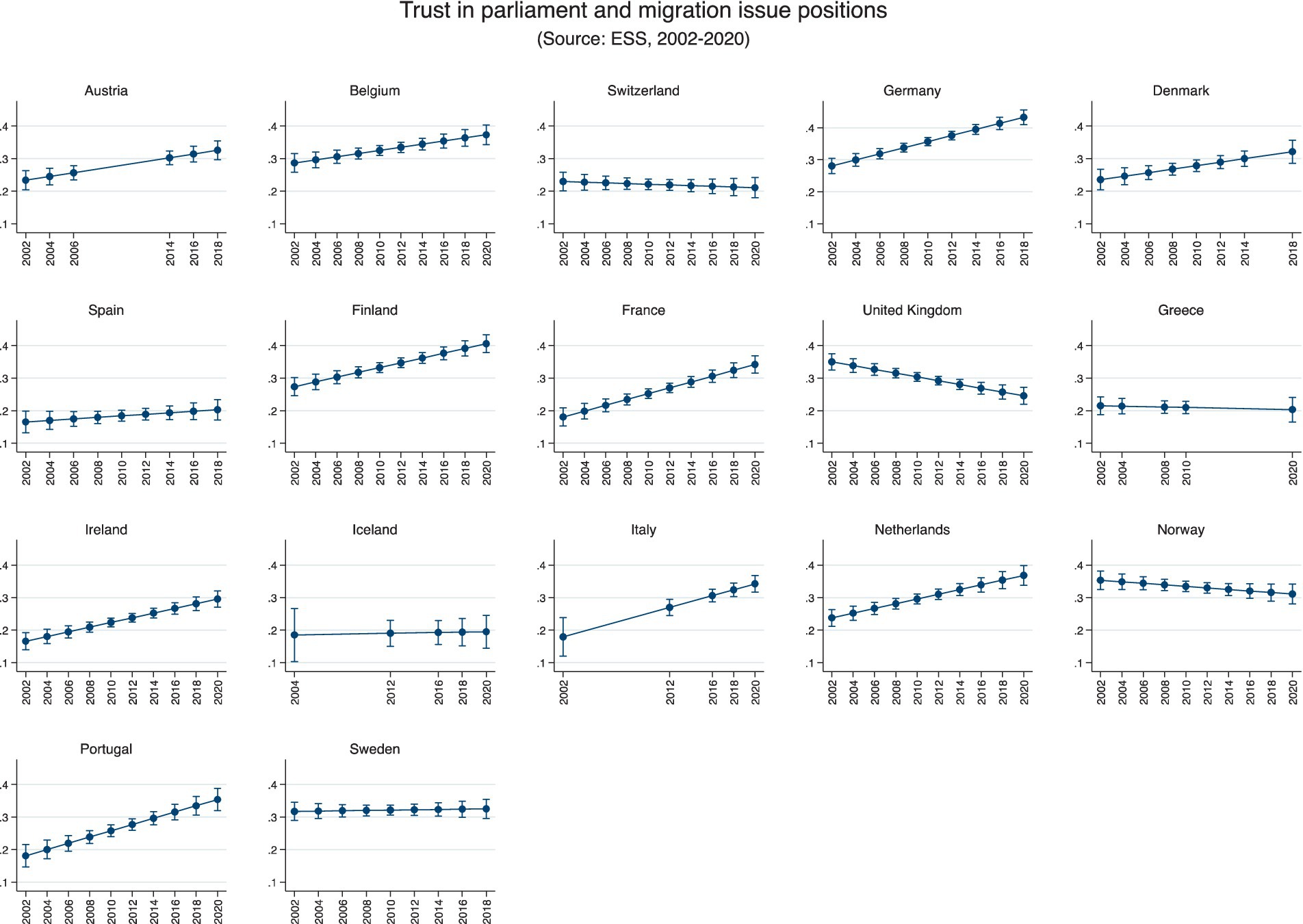

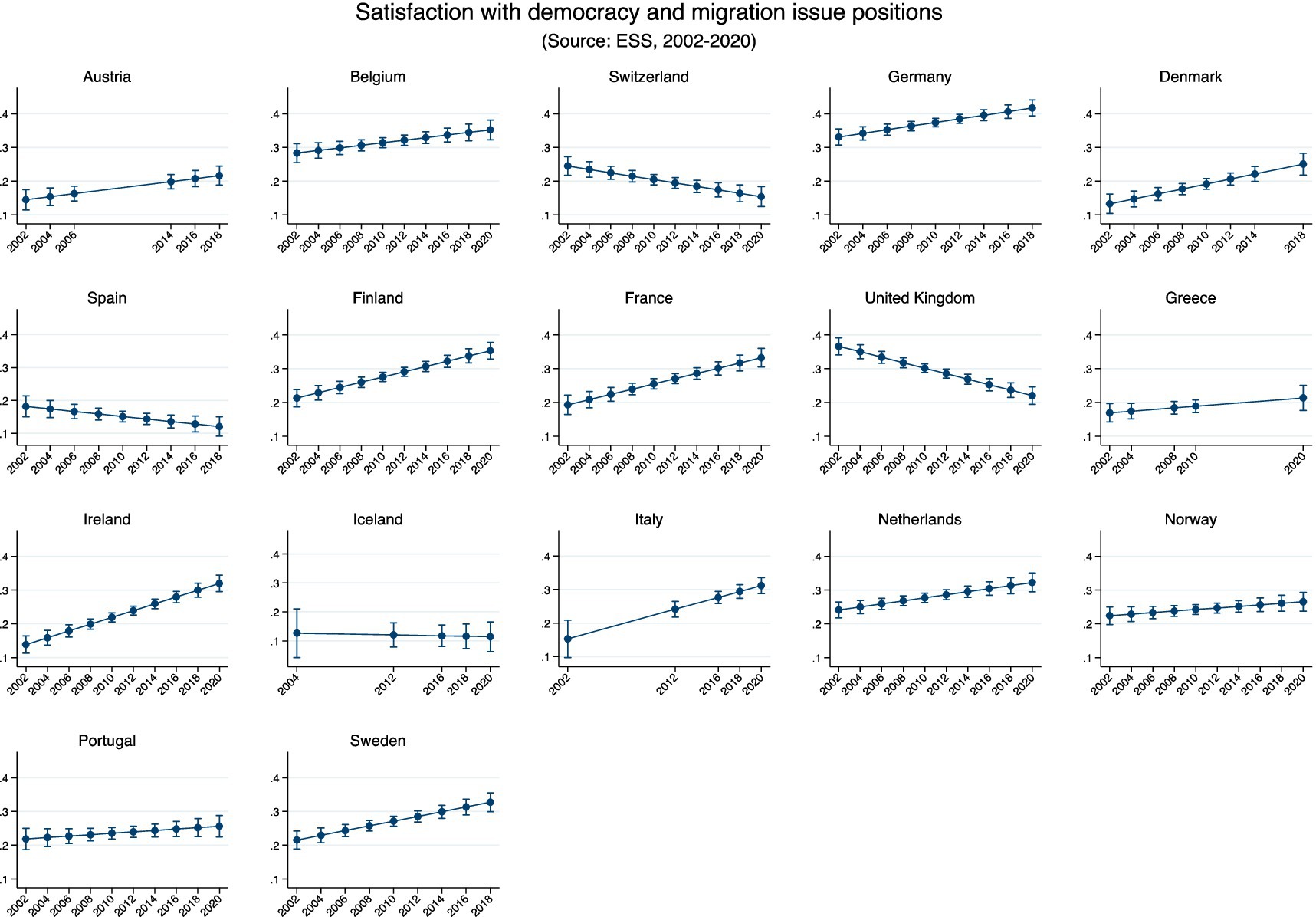

Finally, Figures 5, 6 show the effects of issue positions on immigration on trust in parliament and satisfaction with democracy, respectively. Higher scores on immigration positions mean respondents think immigration makes their country a better place to live, which is associated with higher trust in parliament and satisfaction with democracy in all countries, as indicated by the positive coefficients. Have these relationships changed over time?

Figure 5 shows that in 13 out of the 17 countries in our sample, the relation between issue positions on immigration and trust in parliament has become stronger, of which significantly so in 10 countries. The association has weakened in 4 countries, and significantly so in one country, the United Kingdom. Clearly, there appears to be quite some politicization in terms of the association between issue positions on immigration and trust in parliament. However, the degree of politicization differs substantially between countries, with the strongest politicization occurring in Portugal, Germany, Italy and France.

Turning to satisfaction with democracy, Figure 6 shows similar patterns of politicization. In 13 of the 17 countries in our sample, the association between issue positions on immigration and satisfaction with democracy has increased over time, and for 12 countries significantly so. Weakening politicization is apparent in 4 countries, and of these significantly so in 3 countries (United Kingdom, Switzerland and Spain).

As Figures 1–6 demonstrate, in terms of the associations of citizens’ substantive policy positions with trust in parliament and satisfaction with democracy, we find evidence for positions on the EU and immigration having become increasingly associated with political support over time in most European countries in our sample, indicating increasing politicisation. Citizens’ positions on income differences appear to have become less associated with political support, indicating decreasing politicisation.

5.2 Political support and vote choice

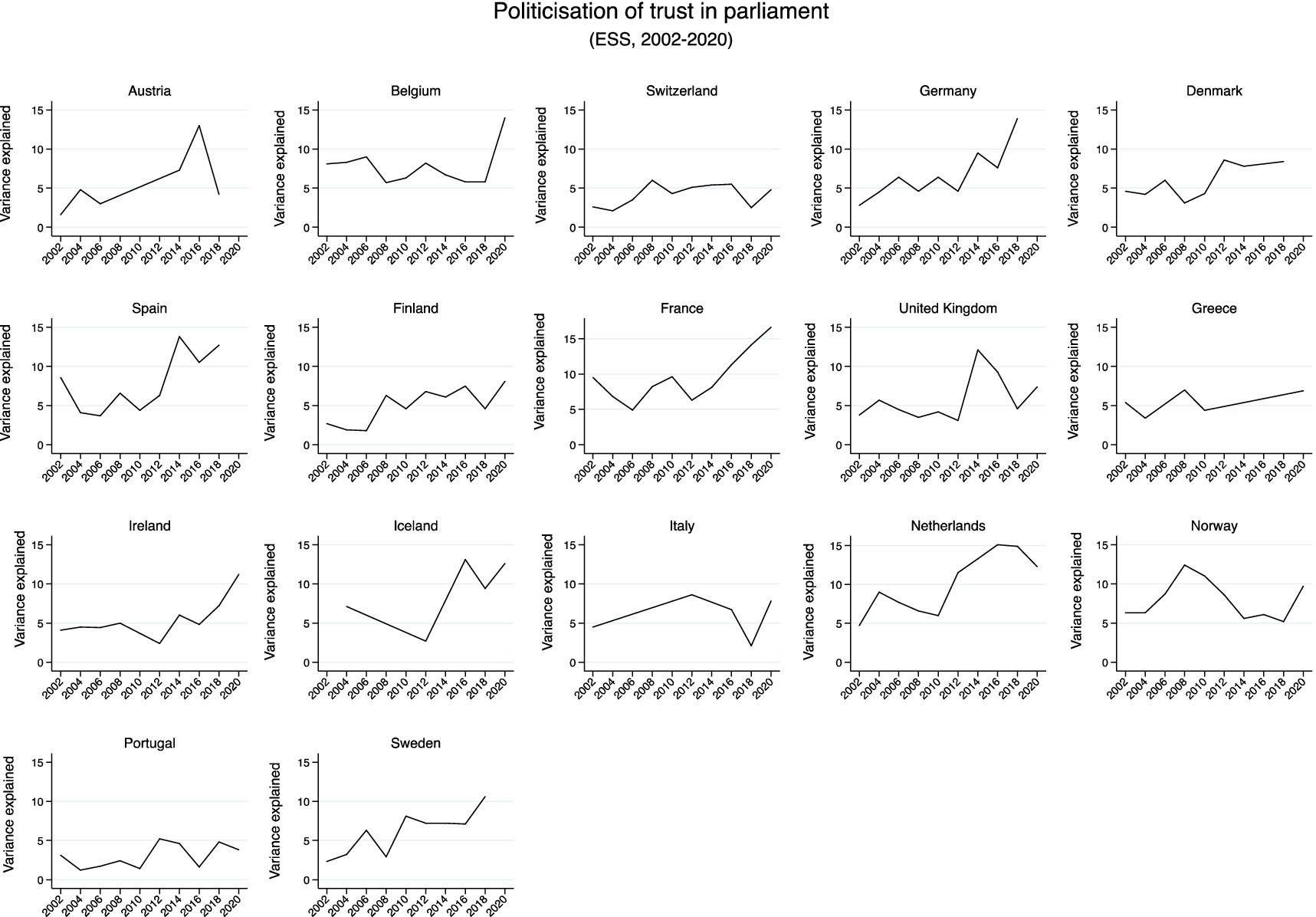

In addition to politicization occurring in terms of citizens’ substantive policy positions becoming more strongly intertwined with their political support, we also hypothesized that political support becomes increasingly related to vote choice, as a second indicator of politicization. Since the political parties that respondents can vote for in elections change over time, we analyse the relation between political support and vote choice separately for each year in each country. Figures 7, 8 below show the proportion of variance in trust in parliament and satisfaction with democracy respectively, that can be explained by vote choice in each election (for full models, see the Appendix).

As Figure 7 shows, politicization of trust in parliament in relation to vote choice appears to have occurred in at least 13 out of the 17 democracies in our sample, with sharp increases in countries such as Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden. Despite clear signs of politicization, what also becomes clear is that politicization can and does vary over time in different countries, as strong fluctuation in countries such as Austria, Norway and Italy shows. This suggests that when perceived legitimacy gaps are indeed addressed and resolved, politicization can decline again.

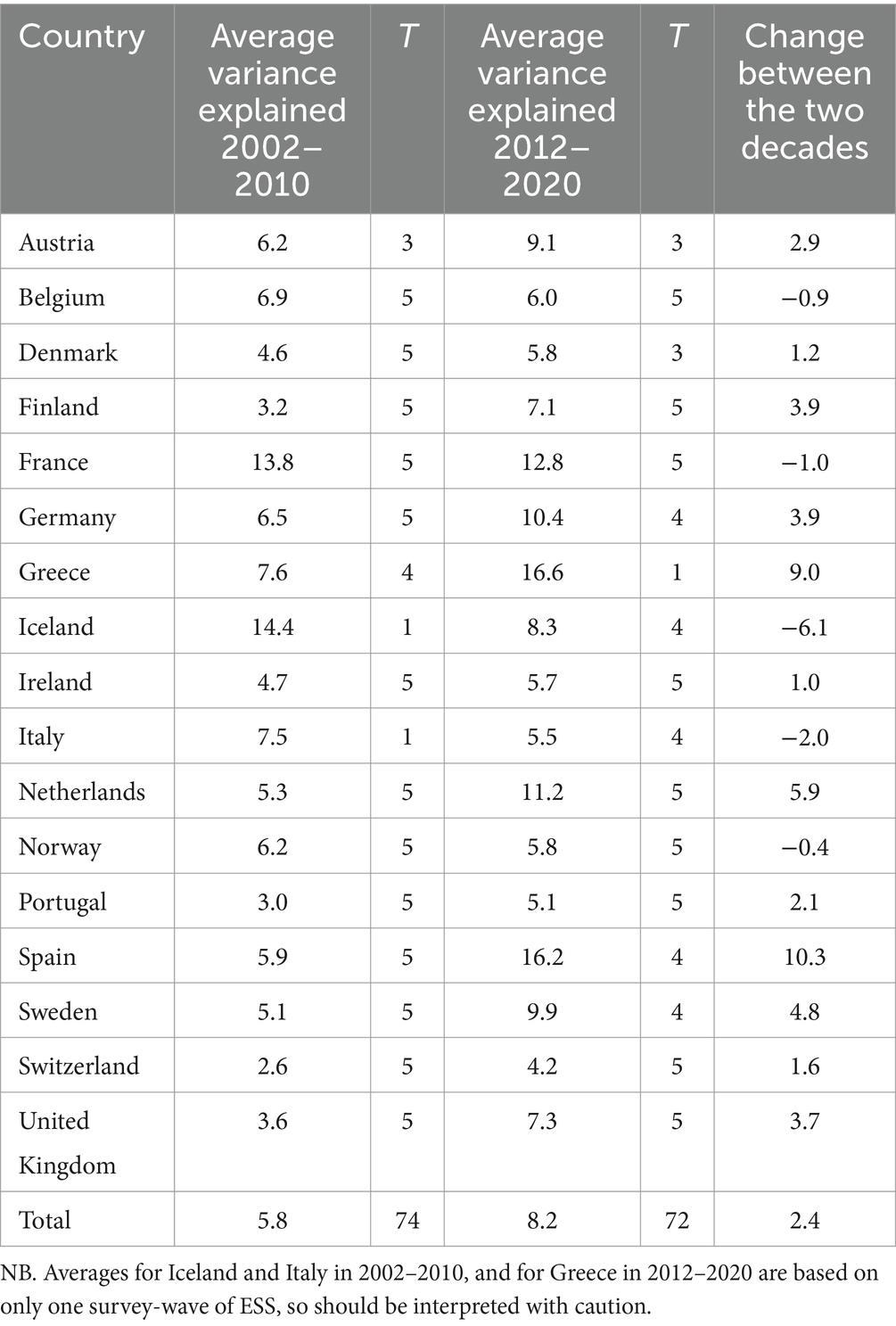

In order to get a sense of whether, despite this fluctuation, an overall long-term increase in politicization is noticeable, Table 1 shows average levels of politicization between 2002–2010, and 2012–2020, expressed as the proportion of variance in political trust that is explained by vote choice. An increase in politicization is visible in all countries except Norway. In all other countries, the proportion of explained variance increases by between 0.6 and 6.6%—and overall, this proportion increased from 5.2 to 8.0% in these two decades. This is indicative of an increasing politicization of political support across the board. The highest absolute levels of politicization are found in the Netherlands, France, Spain and Iceland. In 2020, the proportion of variance in political trust that could be explained by vote choice ranged from 12.3% in the Netherlands, to 12.6% in Iceland, to 16.6% in France. In Spain, where the last data are from 2018, this was 12.7%. In years prior to that, levels of politicization were even higher in some of these countries. The largest increases in these past two decades are found in the Netherlands and in Spain, with politicization doubling between 2002 and 2020.

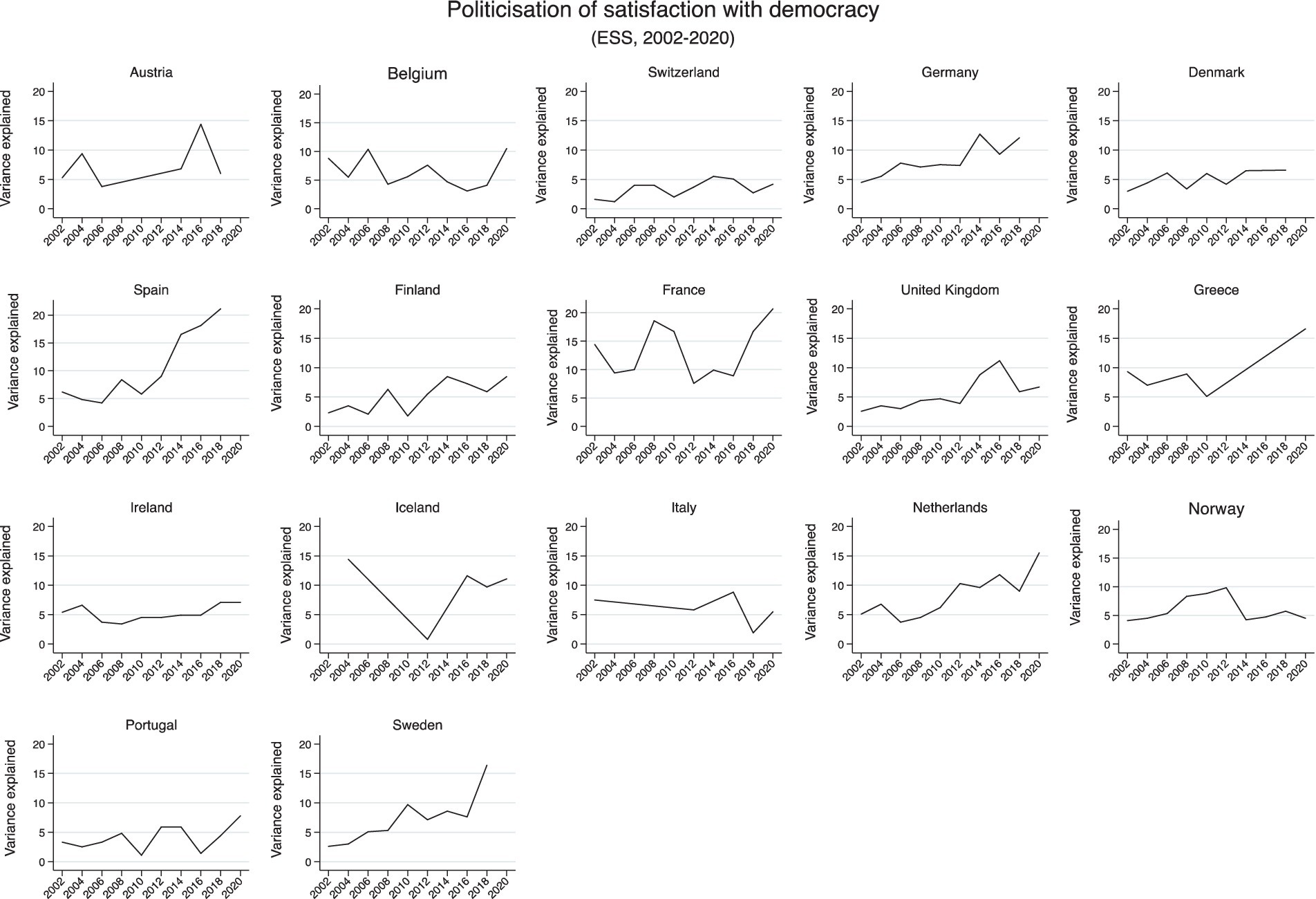

Turning to satisfaction with democracy, Figure 8 shows clear increases in politicization, in terms of the proportion of variance in satisfaction with democracy that is explained by vote choice, in at least 8 out of the 17 democracies in our sample. The other 9 countries appear to be more characterised by fluctuation in the degree of politicization. Indeed, when comparing average levels of politicization between 2002–2010, and 2012–2020, Table 2 shows that in 5 countries, average levels of politicization declined.

However, in all other countries in the sample, politicization increased on average, with the proportion of variation in satisfaction with democracy explained by vote choice increasing between 1.0 and 10.3%. Overall, politicization increased from 5.8 to 8.2% in these two decades. The highest absolute levels of politicization are found in Spain, Greece, France and the Netherlands, and to a lesser extent in Germany and Sweden. The largest increases in these past two decades are found in Spain and Greece.

6 Conclusion

As citizens have different ideals of what democracy should be, and different experiences with how democracy functions in practice, dissatisfaction with political authorities and institutions among at least some citizens may be part and parcel of democracy. However, a core idea of representative democracy is that democracy provides possibilities for citizens to express such dissatisfaction, either through protests or elections, and in doing so mobilise other citizens and political actors to resolve perceived legitimacy gaps. Ideally therefore, dissatisfaction with political authorities and institutions can be resolved by governments changing course, or by citizens electing a new government at the next elections.

However, if dissatisfaction is not resolved, it may very well spill over to higher levels of political support and end up undermining support for democracy itself. In this case, we would expect that political support itself becomes part of politics: as political parties seeking to mobilize disillusioned voters not only campaign on substantive policy positions, but also on distrust of political institutions and promises to improve, fix, or overhaul the system. In this case, political support becomes politicized, as the political system itself becomes the object of political competition. Such politicization is particularly problematic for the stability of democracy when it takes on a more structural character.

In this paper we investigated to what extent there is empirical evidence for the politicization of political support in 17 European democracies between 2002 and 2020. We expected politicization to have increased over time in this period, for several reasons. First of all, as national governments are faced with increasingly complex and often transnational issues, such as migration and climate change, their capacity to respond to potential citizen dissatisfaction about these issues may have declined. In addition, shifts in policy-making power to transnational governments such as the EU, as well as the increasing influence of globalised markets, may have limited discretion of national governments even further. Third, the rise of radical left and right political parties in most European party systems that mobilise on political distrust, may have further contributed to politicizing dissatisfaction.

In this paper we investigated politicization empirically by considering the association of political support with substantive issue positions on the one hand, and with vote choice on the other hand. When it comes to politicization in terms of citizens’ substantive issue positions becoming increasingly intertwined with their political support, we find politicization mainly on socio-cultural issues such as immigration and EU unification, and much less on socio-economic issues such as income differences. This is in line with research that has demonstrated the growing importance of socio-cultural issues for voters in European democracies (Kriesi et al., 2008; Van der Brug and van Spanje, 2009). It appears that citizens’ positions on the EU and immigration are increasingly strongly correlated with their political trust and satisfaction with democracy, with citizens that are against EU unification and immigration having become increasingly less trusting of political institutions and less satisfied with the way democracy works.

This dissatisfaction also appears to be increasingly translated into vote choice, as we find politicization in terms of citizens’ vote choice becoming increasingly strongly related to their political support in most countries in our sample. In the relatively short time-period in which ESS surveys have been fielded, the two decades from 2002 until 2022, the association between vote choice and political support has increased in most countries in our sample, from on average about 5 and 6% to more than 8%. In 3 and 5 countries respectively, more than 10% of the variation in trust in parliament and satisfaction with democracy is now explained by vote choice. Therefore, there appears to be quite some descriptive empirical evidence indicating substantial politicization of political support in European democracies. At the same time, it is important to note that we find significant variation in levels of politicization in different countries. Moreover, the fact that politicization varies over time in different countries, suggest that politicization can also decline.

These findings open up a range of follow-up questions that future research could address. A key question is what causes politicization. Is politicization driven by bottom-up processes of citizens feeling the political system is not living up to their standards, and if so, where precisely do citizens consider democracy to be under-performing? Is politicization driven by a lack of substantive or descriptive representation, by personal experiences in dealing with political authorities, or by (accurate or inaccurate) perceptions of institutional performance that are shaped by media reporting and elite cues? Alternatively, to what extent is politicization driven by top-down processes of political parties that mobilise on political distrust and critique the way democracy functions, and promise to fix the way the democratic system and its institutions work? A third important question is what causes fluctuations in politicization within countries over time: does this happen because perceived legitimacy gaps are actually resolved, or is it rather the product of the political agenda shifting its attention elsewhere and other issues becoming more salient? And relatedly, what are the consequences of increasing politicization of political support? Does politicization of support lead to democratic innovation and reform to resolve perceived legitimacy gaps? Or does politicization of support lead to further politicization, and eventually to increases in support for alternatives to democracy?

This leads us to a fourth and final line of inquiry. To what extent is increasing politicization of political support problematic for democratic stability? As we noted in the paper, paradoxically, legitimacy gaps need to be politicized in order to get resolved. When legitimacy gaps become politicised the goal should therefore be to resolve perceived legitimacy gaps and improve the perceived responsiveness of the democratic system and its institutions. But if political parties and actors who mobilize their voters on legitimacy gaps subsequently cannot solve them (i.e., due to diminished discretion of national governments, in combination with increased complexity, in many policy domains), or do not want to solve them (i.e., because mobilizing on distrust is electorally advantageous), then things may go from bad to worse; ultimately increasing support for alternatives to democracy.

The extent to which this happens, is of course an empirical question, and one that would require further research into the bottom-up and top-down processes that drive politicization of political support. Doing so should help to gain better insight into the conditions under which democracy itself becomes the object of political competition, and how it can come to be seen as “the only game in town” again.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by data are from European Social Survey, that operate with full ethics clearance. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EE: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^There is evidence based on cross-sectional data that dissatisfaction with the way democracy works is related to lower support for democracy (Auerbach and Petrova, 2022; Zaslove and Meijers, 2023), but over-time data would be needed to identify under what conditions and for which people spill-over occurs from support for political authorities to support for the political system.

2. ^Note that here we take citizens’ (subjective) own normative principles of what constitutes ‘just’ authority as the starting point for their legitimacy evaluations of political authority. However, as Wiesner and Harfst (2022) highlight, regime legitimacy can also be defined using external normative-theoretical principles. For a more in-depth discussion on the genealogy of the concept of legitimacy and these differences between normative-theoretical and empirical approaches, see Wiesner and Harfst, 2022.

3. ^Easton distinguished these two dimensions in his work on political support by referring to two types of political support: specific support which is evaluative and directed at the performance of an object and diffuse support which is more affective and directed at “what an object is or represents – to the general meaning it has for a person-, not of what it does” (Easton, 1975: 444). Easton expected that specific support among citizens might vary as political authorities change over time, but suggested relatively stable levels of diffuse support were important for democratic stability, and also warned that if low specific support became structural, this might well undermine more diffuse support.

4. ^“Claims that the people are sovereign are invitations for people to act; claims that the government serves the people are invitations for people to demand it do so; claims that the governors are the people’s representatives are invitations for those who feel unrepresented to point that out.” (Markoff, 2011: 258–259).

5. ^The political community (i.e., the demos) is often considered an important element of political support as well, but one that is outside the scope of this paper.

6. ^Empirically, support for political authorities is often measured by trust in or satisfaction with the government, politicians or political parties. Support for political institutions is mostly measured by trust in a variety of institutions, ranging from parliament to the judiciary to the media and the bureaucracy (Zmerli and van der Meer, 2017; Norris, 2022). And support for the political system is measured on the one hand, by satisfaction with the way democracy is functioning in practice (i.e., support for ‘real-existing’ democracy), and on the other, by support for democracy as an ideal political system (i.e., normative support for democracy) (Dalton, 2004; Norris, 2011; Ferrin, 2012).

7. ^A question on immigration policy, i.e., whether immigration levels should be decreased or increased in respondents’ country was not available in the ESS for the full period.

8. ^Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom.

References

Achen, C. H. (2005). Let’s put garbage-can regressions and garbage-can probits where they belong. Confl. Manag. Peace Sci. 22, 327–339. doi: 10.1080/07388940500339167

Auerbach, K., and Petrova, B. (2022). Authoritarian or simply disillusioned? Explaining democratic skepticism in central and Eastern Europe. Polit. Behav. 44, 1959–1983. doi: 10.1007/s11109-022-09807-0

Claassen, C. (2019). Does public support help democracy survive? Am. J. Polit. Sci. 64, 118–134. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12452

Claassen, C., and Magalhães, P. C. (2022). Effective government and evaluations of democracy. Comp. Pol. Stud. 55, 869–894. doi: 10.1177/00104140211036042

Dahl, R. A. (1956). A preface to democratic theory (Vol. 10). (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Dalton, R. J. (1999). “Political support in advanced industrial democracies” in Critical citizens: Global support for democratic government. ed. P. Norris (New York: Oxford University Press).

Dalton, R. J. (2004). Democratic challenges democratic choices. The erosion of political support in advanced industrial democracies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dalton, R. J., Shin, D. C., and Jou, W. (2007). Understanding democracy: data from unlikely places. J. Democr. 18, 142–156. doi: 10.1353/jod.2007.a223229

Devine, D., and Valgarðsson, V. O. (2023). Stability and change in political trust: evidence and implications from six panel studies. Eur J Polit Res 63, 478–497. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12606

Easton, D. (1975). A re-assessment of the concept of political support. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 5, 435–457. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400008309

Ferrin, M. (2012). What is democracy to citizens? Understanding perceptions and evaluations of democratic systems in contemporary Europe. PhD Thesis. Florence: European University Institute.

Ferrin, M., and Kriesi, H. (2016). How Europeans view and evaluate democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Foa, R., and Mounk, Y. (2016). The democratic disconnect. J. Democr. 27, 5–17. doi: 10.1353/jod.2016.0049

Gilley, B. (2006). The meaning and measure of state legitimacy. Results for 72 countries. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 45, 499–525.

Graham, M. H., and Svolik, M. W. (2020). Democracy in America? Partisanship, polarization, and the robustness of support for democracy in the United States. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 114, 392–409. doi: 10.1017/S0003055420000052

Hakhverdian, A., and Schakel, W. (2022). The political representation of left-nationalist voters. Acta Politica 57, 489–509. doi: 10.1057/s41269-021-00205-8

Hillen, S., and Steiner, N. D. (2020). The consequences of supply gaps in two-dimensional policy spaces for voter turnout and political support: the case of economically left-wing and culturally right-wing citizens in Western Europe. Eur J Polit Res 59, 331–353. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12348

Hooghe, L., and Marks, G. A. (2009). Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus. British J. Polit. Sci. 39, 1–23.

Kolln, A. K., and Aarts, K. (2021). What explains the dynamics of citizens’ satisfaction with democracy? An integrated framework for panel data. Elect. Stud. 69, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102271

Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., and Frey, T. (2008). West European politics in the age of globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krishnarajan, S. (2023). Rationalizing democracy: the perceptual bias and (un)democratic behavior. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 117, 474–496. doi: 10.1017/S0003055422000806

Linz, J. J., and Stepan, A. (1996). Problems of democratic transition and consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and post-communist Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Magalhães, P. C. (2016). Economic evaluations, procedural fairness, and satisfaction with democracy. Polit. Res. Q. 69, 522–534. doi: 10.1177/1065912916652238

Mair, P. (2009). Representative versus responsible government, MPIfG working paper, no. 09/8, max Planck Institute for the Study of societies, Cologne

Markoff, J. (2011). A moving target: democracy. Eur. J. Sociol./Arch. Eur. Sociol./Europäisches Archiv für Soziologie 52, 239–276. doi: 10.1017/S0003975611000105

Norris, P. (1999). Critical citizens: Global support for democratic governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norris, P. (2011). Democratic deficit. Critical citizens revisited. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Powell, G. B. (2000). Elections as instruments of democracy: Majoritarian and proportional visions. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Przeworksi, A. (1991). Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rooduijn, M., van der Brug, W., and de Lange, S. L. (2016). Expressing or fuelling discontent? The relationship between populist voting and political discontent. Elect. Stud. 43, 32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2016.04.006

Thomassen, J., Andeweg, R., and van Ham, C. (2017). Political trust and the decline of legitimacy debate, S. Zmerli and T. vander Meer (Eds.), The handbook on political trust. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing

Thomassen, J., and Van Ham, C. (2017). A legitimacy crisis of representative democracy?, C. Van Ham, J. Thomassen, K. Aarts, and R. Andeweg (Eds.) Myth and reality of the legitimacy crisis: Explaining trends and cross-National Differences in established democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tyler, T. R. (2006). Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 57, 375–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190038

Van der Brug, W., and van Spanje, J. (2009). Immigration, Europe and the new cultural dimension. Eur J Polit Res 48, 309–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.00841.x

Van Ham, C., and Thomassen, J. (2012). A legitimacy crisis of representative democracy?. Working paper, presented at expert meeting about the (presumed) legitimacy crisis of representative democracy in advanced industrial democracies, Netherlands Royal Academy of sciences, Amsterdam.

Van Ham, C., Thomassen, J., Aarts, K., and Andeweg, R. (2017). Myth and reality of the legitimacy crisis: Explaining trends and cross-National Differences in established democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Werner, H., and Marien, S. (2022). Process vs outcome? How to evaluate the effects of participatory processes on legitimacy perceptions. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 52, 429–436. doi: 10.1017/S0007123420000459

Wiesner, C., and Harfst, P. (2022). Conceptualizing legitimacy: what to learn from the controversies related to an “essentially contested concept”. Front. Polit. Sci. 4, 1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.867756

Wuttke, A., Gavras, K., and Schoen, H. (2022). Have Europeans grown tired of democracy? New evidence from eighteen consolidated democracies, 1981–2018. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 52, 416–428. doi: 10.1017/S0007123420000149

Zaslove, A., and Meijers, M. (2023). Populist democrats? Unpacking the relationship between populist and democratic attitudes at the citizen level. Polit. Stud. 77:173800. doi: 10.1177/00323217231173800

Zmerli, S., and van der Meer, T. (2017). The handbook on political trust. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Zorell, C. V., and van Deth, J. W. (2020). Understandings of democracy: new norms and participation in changing democracies. SocArXiv. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/bmrxf

Keywords: legitimacy, political support, spill-over, system support, politicization, political trust, satisfaction with democracy

Citation: van Ham C and van Elsas E (2024) When legitimacy becomes the object of politics: the politicization of political support in European democracies. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1363083. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1363083

Edited by:

Philipp Harfst, University of Göttingen, GermanyReviewed by:

Jessica Fortin-Rittberger, University of Salzburg, AustriaUrsula Hoffmann-Lange, University of Bamberg, Germany

Copyright © 2024 van Ham and van Elsas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carolien van Ham, Y2Fyb2xpZW4udmFuaGFtQHJ1Lm5s

Carolien van Ham

Carolien van Ham Erika van Elsas

Erika van Elsas