- 1Department of Public Administration, Universitas Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa, Serang, Banten, Indonesia

- 2Department of Government, Universitas Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa, Serang, Banten, Indonesia

- 3Department of Politics, Universitas Padjajaran, Bandung, West Java, Indonesia

The decision to relocate the nation’s capital from Jakarta is not without reason. Jakarta, the nation’s capital, is regarded as less than ideal, with numerous issues such as flooding, air pollution, poor water quality, and political and environmental sustainability. This research will be based on the framework of ecological citizenship to investigate active citizens. The lesson from other countries that relocate their capital city as a comparison. This research uses a qualitative research method with a literature study type of research. reviewing several previous studies on citizenship and academic texts on moving the nation’s capital, studies on moving the capital, and legislation on the nation’s capital. This research tries to find how the possibility of environment sustainability in the new capital project. Ecological concerns have not been on the agenda of public discussion. Moreover, this research provides more information on the opportunity of ecological citizenship community in Indonesia’s new capital city project, in the context of the sustainability agenda.

1 Introduction

The relocation of Indonesia’s capital city from Jakarta has been a long-planned project since the 1960s when President Soekarno was in power. However, due to changes in leadership from one president to the next, this has never become a reality. In 2019, the government of President Jokowi officially announced a plan to relocate the country’s capital from Jakarta to East Kalimantan (Minister of National Development Planning, 2019).

The decision to relocate the nation’s capital from Jakarta is not without reason. Jakarta, the nation’s capital, is regarded as less than ideal, with numerous issues such as flooding, air pollution, poor water quality, and political and environmental sustainability (Steinberg, 2007). Aside from environmental issues and conditions that are perceived to be worsening, Jakarta is also perceived to have a lack of capacity to manage existing problems (Teo et al., 2020b). Other debates that have become strong reasons for the government to relocate the capital from Jakarta include: approximately 57% of Indonesia’s population is concentrated on the Java island; approximately 58.49% of Indonesia’s economic concentration is concentrated on the Java island; the water crisis that occurred in Jakarta and East Java; the largest land conversion occurred on the Java island, approximately 44% in 2020; and urbanism. Jakarta’s environmental quality is deteriorating (flooding, land subsidence, sea-level rise, river water quality that is polluted by up to 96%, congestion, and other transportation problems that cost up to 56 trillion per year) (Minister of National Development Planning, 2019).

The public is also concerned about the funding required to relocate the capital city to East Kalimantan. The first scenario requires at least 466 trillion (32.9 billion USD) in development costs, while the second scenario requires 323 trillion (22.8 billion USD). Despite the fact that the Jokowi government claims that this relocation will increase economic equality outside of Java by around 50% (Minister of National Development Planning, 2019).

For the time being, what some environmental activists are concerned about is the possibility that relocating the capital will only exacerbate existing problems in East Kalimantan (Sloan et al., 2019; Shimamura and Mizunoya, 2020; van de Vuurst and Escobar, 2020; Teo et al., 2020a,b). Penajam Paser, as the center area for the development of the government place for the new capital, is close to several existing cities such as Samarinda, Balikpapan, and Kutai Kartanegara, and in some existing cities, environmental damage has been caused by mining activities that began in the early 2000s (interview with informant1) (Siburian, 2012, 2015).

For example, several major floods occurred in Samarinda in early 2020, as reported by floodlist.com (Indonesia—Samarinda Floods Again, Thousands Affected) and the Jakarta Post.2 The same thing occurred in Balikpapan and Kutai Kartanegara, which have a high risk of natural disasters due to the massive mining activities that take place there (Saputra et al., 2023; Suling et al., 2023). Environmental damage has also begun to impact the Balik and Dayak tribal areas, as indigenous residents in the Paser area are behind the jargon of green city development3. This condition is a problem arising from land conversion, namely changing open areas to built-up areas. The land area that will be used as the new capital city reaches 180,965 hectares. In short, the National Capital Region (IKN) is divided into three rings. The first ring covers an area of 5,644 hectares, which the government calls the Core Central Government Area; the second ring covers 42,000 hectares, which the government calls the National Capital Region (IKN); and the third ring covers 133,321 hectares, which the government calls the National Capital Expansion Area (Bappenas, 2019).

2 The politics of citizenship

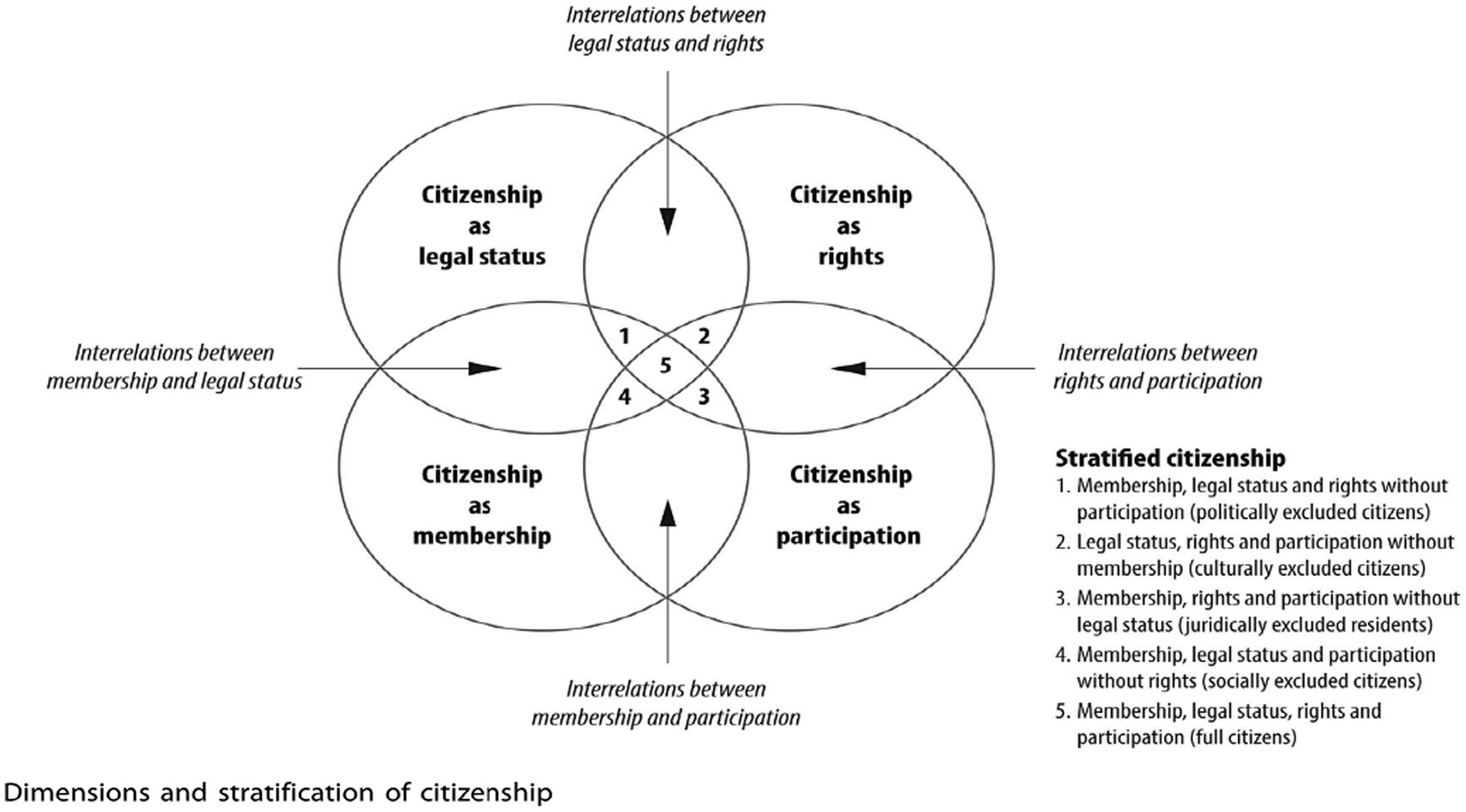

This qualitative research aims to investigate the problems of the relocation of the new capital city of Indonesia. This qualitative research method attempts to elaborate on the meaning of the phenomenon and describe it in this research using the model of citizenship as an approach to perceive the actor of green discourse in the new capital city project. Understanding the project of relocating Indonesia’s new capital and its relationship to the potential for environmental degradation. This research will attempt to use qualitative methods while focussing on actors involved in exclusion and inclusion on the agenda of public engagement and contestation. The Politics of Citizenship is a contestation arena in which members, legal status, rights, and participation are contested. Citizens are at risk of exclusion as well as inclusion in this contest, as seen in Figure 1 (Stokke, 2017). Citizenship politics is also linked to the issue of distribution and redistribution in democratization in order to address problems of inequality. It is to see how to understand the context of civil rights that has evolved into political rights in the tradition of citizenship as a framework (Betts, 1990). In this context, citizenship is more easily understood as membership.

Figure 1. Dimensions and stratification of citizenship. Source: Stokke (2017).

Using library research, this article uses official state documents to see the movements of actors in the transmission of Indonesia’s capital city. Several documents were reviewed: the Document for Preparing a Strategic Environmental Study for the National Capital Masterplan for Fiscal Year 2020; the Academic Text of the Draft Law on Capital State Cities; the Pocket Book on the Transfer of State Capitals; and Law Number 3 of 2022 concerning State Capitals. So, this research will answer questions related to the New National Capital regarding: How does the New National Capital impact environmental degradation? Regarding citizenship, this research also discusses how actors play a role in the distribution of democracy to overcome the gaps that occur.

Citizenship politics has many aspects to each issue. It can, however, be divided into two broad categories: membership and legal status issues, and rights and participation. In this framework, citizenship is very closely related to power relations in an existing contestation, whether it is a contestation of exclusion and inclusion in a democratic and political institution, or whether it is a contestation of class, gender, civil, labor, or others (Betts, 1990). Furthermore, if we include the citizenship debate, we can see how the contestation is influenced by a latent ideology, namely how liberalism and communitarianism affect citizenship as a framework (Hikmawan et al., 2021). As a result, membership engagement and political behavior will differ. Individual rights and civic republicanism debates are framed by various forms of citizenship, including differentiated citizenship (Young, 1990, 2000, 2011). Citizenship is sought in this case as a framework for analyzing oppression and exclusion in various forms of membership.

3 A lesson and opportunity

Aside from environmental damage, it is also feared that potential conflicts will arise in the new capital. Penajam Paser, the site of the new capital’s construction, is an area with ancestral customs and environmental activities, namely customary lands that may be impacted by the project’s construction. Even Kutai Kartanegara, one of Indonesia’s oldest kingdoms, is concerned about the potential consequences (interview with informant). The question is whether the central government has taken inclusive steps to avoid ethnic conflict between newcomers and residents, as happened in Sampan, Madura.

In examining the potential problems that may exist, in this case, environmental damage and the impact of environmental conflicts that may arise during the process of relocating the new capital to East Kalimantan, it is worth reconsidering whether environmental issues are of concern to the people of Indonesia, particularly East Kalimantan. Or is the government’s discourse for economic equality as well as equitable development, which is the discourse of President Jokowi’s government in relocating the capital, covering all forms of damage that are currently occurring as well as the potential that will arise later? Of course, this is intriguing enough to warrant further investigation.

In answering this question, it is interesting to look at ecological citizenship as an effort to understand the potential damage that exists from various sources of local actors who are involved and to see the scope of the government’s environmental governance agenda. Do not allow the agenda of relocating the capital to become merely a matter of development and business project effort.

This research is based on existing environmental concerns and issues. Furthermore, the ecological citizenship approach enables us to see the involvement of public engagement relations and environmental governance, which has become a government discourse (Smith, 2003; Dobson, 2004; Dobson and Eckersley, 2006).

The most difficult challenge of ecological citizenship is distinguishing between what is on the agenda of the Jokowi Government in terms of economic equality and how this discourse must be accompanied by sustainability in existing environmental issues. Even with the “Smart Green, Beautiful, and Sustainable” discourse, the relocation of the new capital must be on the agenda with the Indonesian people, not just for the sake of the economy, let alone the interests of a few elite groups for the sake of the business project.

In general, ecological awareness has not been on the agenda of Indonesian people, and it is very rare to come up in public discussion; only a few local activists are active in mining cases in East Kalimantan, the majority of which are owned by the national political elite, and they are now turning to the issue of relocating the capital. One of the concerns expressed by local environmental activists such as “JATAM” is that there may be a link between the damage caused by large mining corporations owned by national elites and efforts to relocate the new capital to conceal the damage. Of course, this suspicion assumption necessitates additional data and research.

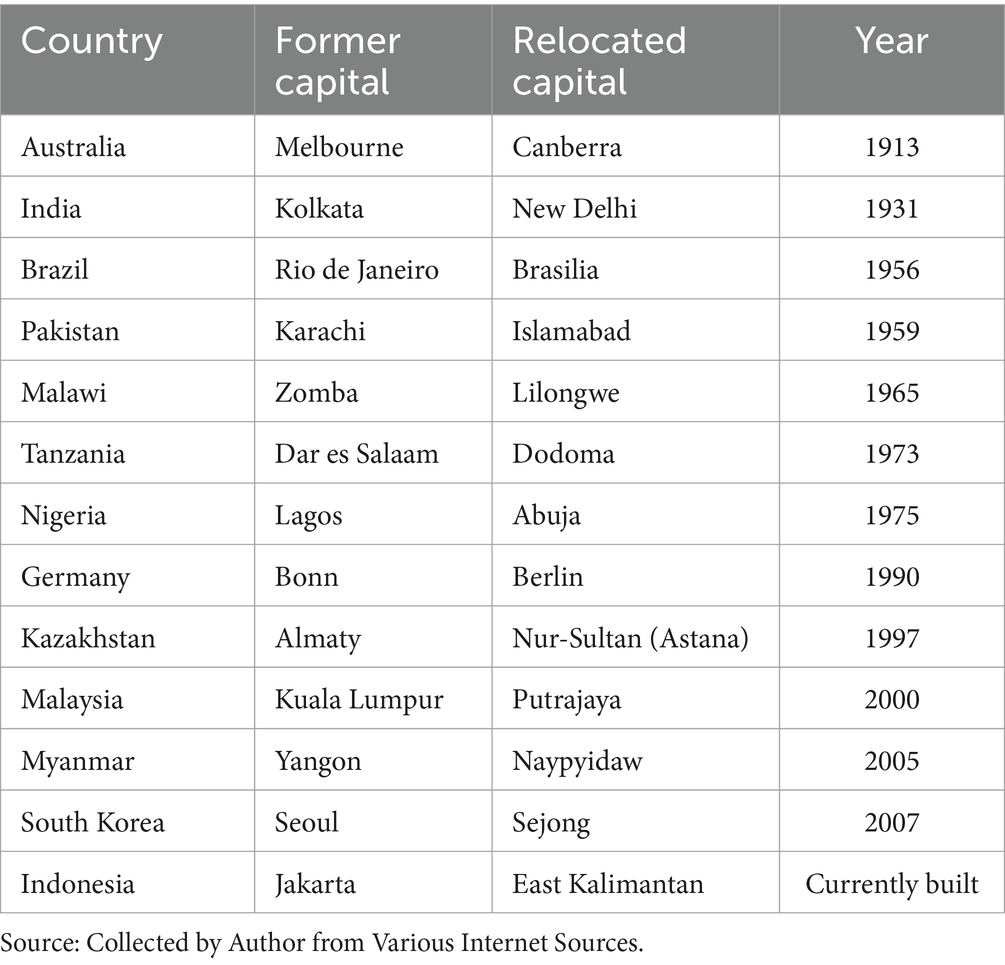

Indonesia is not the only country that has had its capital city relocated. As shown in Table 1, some countries’ capital cities have been relocated.

The case of Brazil teaches us about how relocating the capital can alter the way civil society and elites interact with one another. Brasília has been the federal capital of Brazil since 1960. The relocation of Brazil’s old capital, Rio de Janeiro, was intended to redistribute development outcomes and promote a more modern vision of the country. However, as time passed, relocation to Brasilia began to exacerbate land conflicts between poor landless migrants who had relocated to the new capital and state authorities. This case demonstrated that the establishment of a new capital city does not necessarily result in more equitable development (Anugrah, 2019).

While Jokowi’s decision to relocate the capital has garnered considerable attention in Indonesia, there are already numerous examples of countries that have chosen to relocate their administrative center to a new location around the world. According to Potter (2017), almost 30% of countries have their capital outside of their largest city, and 11 countries have shifted capitals since 1960. The reason for the relocation of the capital city is most likely a civil–society conflict (Potter, 2017). However, various factors may influence such decisions. While the reason for relocating the capital city in Canberra, Australia, was to preserve a political symbol for the nation, in other cases, governments attempted to create a balance of power in the face of a divided population, such as when the United States established Washington City, or in the case of Naypyidaw, Myanmar, the decision was forced by the threat of civil unrest (Campante et al., 2013).

Instead, the Myanmar government designated Naypyidaw as their new political capital in 2005. In the case of Myanmar, we can see how the relocation of the capital will cause a number of issues if the impact is not properly calculated. Myanmar, for example, relocated its capital from Yangon to Naypyidaw. Analysts disagree on what prompted the military government to relocate the capital: whether it was to promote the idea of state-led ethnic and racial unity and rural development, to bury memories of popular unrest in Yangon, to avoid growing pro-democracy protests, or a combination of these factors (Anugrah, 2019). The Myanmar government stated that the relocation to Naypyidaw, which was built from the ground up in the middle of rice paddies and sugar cane fields, was similar to building Canberra or Brasilia, an administrative capital away from the traffic jams and overcrowding of Yangon, their previous capital. The city itself was divided into several zones, each with its own distinct design. In addition, the city is home to a military base, which is inaccessible to citizens or other personnel without written permission. The government has set aside two hectares of land each for foreign embassies and United Nations missions’ headquarters. In 2017, the Chinese embassy formally opened its interim liaison office, the first foreign office permitted to open in Naypyidaw. However, as in the case of Putrajaya in Malaysia, many foreign embassies are hesitant to relocate to this new city. State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi presided over a meeting at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Naypyidaw in February 2018, where she urged foreign governments to relocate their embassies to the capital. In fact, in 2019, several reports on Myanmar pointed out that many government-owned buildings and houses are facing a state of decay because of neglect, and no officials are living or working in those buildings.4

Because of its proximity and cultural affinity with Indonesia, it is worth devoting a few lines to the Malaysian case. The Malaysian government, led by Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohammad, planned to relocate the capital to a new city called Putrajaya in the mid-1980s. The city was divided into two sections by the master plan: the core and the periphery. The core was designed to be, and still is, the administrative and symbolic heart of the city and country, showcasing Putrajaya’s identity through grand civic structures. Hotels, shopping malls, commercial offices, exhibition and convention centers, private colleges, a private hospital, and various tourist attractions are also located in the core. While the periphery is designed to house 14 residential neighborhoods with 67,000 housing units, each neighborhood contains a variety of housing for a range of incomes, such as detached homes, rowhouses, shophouses, and high-rise apartments. There are numerous commercial clusters throughout the city where residents can walk to buy groceries at a wet market, supermarket, or corner shop, as well as a mosque. Furthermore, because it is located in the heart of Borneo, the new capital city of Putrajaya has the potential to create a forest management problem (Sloan et al., 2019). This development condition will trigger the problem of forest degradation, indicated by the decline in forest cover in the Kalimantan region, one of which is caused by the use of land in forest areas, even though the IKN region is part of Kalimantan Island, whose spatial planning direction is to realize the sustainability of biodiversity conservation areas and protected areas with wet tropical forest vegetation covering at least 45% of the area of Kalimantan Island as the Lungs of the World.

This ambitious project also aims to demonstrate Malaysia’s modernisation and new Muslim identity (Moser, 2010). Unfortunately, despite its great design, large budget, and explicit goal of creating a “garden city,” Putrajaya has been unable to attract people other than civil servants and tourists who come to visit it because the city does not allow people to commute around it (Moser, 2010). However, if we look deeper, the issue is more complex than mere connectivity: the development of Putrajaya is a clear example of central planning, as described in the preceding paragraphs, and we have learned that a city is rather a spontaneous command arising from human interaction; it is not surprising that it has been unable to become a vibrant urban context; even international diplomacy has refused to move. Indeed, a city is made up of cultural, political, and economic elements that cannot be separated. To encourage people to relocate to Putrajaya, the Malaysian government enacted various housing incentives and subsidies, including the construction of thousands of affordable homes and the support of the city with mass transportation projects to attract workers from Kuala Lumpur to live in Putrajaya and commute to Kuala Lumpur. However, the anticipated results have yet to be revealed.

South Korea’s experience differs from that of Malaysia’s Putrajaya. The democratic process of relocating the capital city from Seoul to Sejong. Parties took part in the vote and made the decision (Cowley, 2014; Hackbarth and de Vries, 2021). Furthermore, the project includes industry and universities in the planning of relocating the capital city (Lee, 2011; Hackbarth and de Vries, 2021). In contrast to the Malaysian process, Putrajaya was decided by the prime minister and has since become a private project. In this case, Indonesia is more akin to what Malaysia has done by relocating its capital city. President Jokowi himself made the decision to move the capital from Jakarta to East Kalimantan.

Another similarity between Sejong and Putrajaya in the process of relocating the capital is that both prioritize the ecological concept for the new capital. However, there are significant differences in several areas. For example, Putrajaya has several issues with public transportation, which increases the use of private transportation. Meanwhile, Sejong prefers smart public transportation, making it accessible to both residents and visitors (Kang, 2012).

It is demonstrated in some of the preceding literature that explaining new capital can be done using various approaches. Furthermore, several studies have been conducted that reflect this approach to explaining environmental impacts as well as social and economic conflicts. Furthermore, several studies have attempted to explain Sejong and Putrajaya as the new capital through urban city, smart city, land use and conservation, and migration aspects (Moser, 2010; Lee, 2011; Kang, 2012; Cowley, 2014; Sloan et al., 2019).

There are fundamental differences between what I will do in the research on the case of the new capital in East Kalimantan, Indonesia, and what has been done in previous studies. In this research, I will investigate how the contestation arose during the process of relocating the capital city to East Kalimantan. Furthermore, this research focusses on the search for and analysis of a transformation of ecological citizenship, which will see the contestation of actors involved in the discourse of environmental sustainability in the development of new capital in Indonesia.

4 Is it possible for sustainability

Ecological citizenship refers to the relationship between citizenship and the environment, including human beings and non-human natural beings (Smith, 2003, 2004; Dobson, 2004; Dobson and Eckersley, 2006; Carme, 2008). The ecological citizenship framework focusses on contesting actors in an arena, namely the relationship between humans and nature. Developmentalism has become an unavoidable reality in today’s democracy. Every country must strike a balance between using natural resources in its activities and maintaining current sustainability. In this context, ecological citizenship is a framework that sees membership as a contestation of political rights, public engagement, and personal duties and ethics. The framework offered (Dobson and Eckersley, 2006) for understanding environmental sustainability is in line with what is understood (Smith, 2004), namely how the environment must be included in democratic policy institutions that are aware of the existence of the environment.

Dobson sees ecological citizenship as more than just imagination or an abstract concept in this context. It is, however, a result of an attempt to establish democratic institutions for the distribution of equality in the environment. The current debate takes place in a liberal democratic arena in which the environment is viewed as a potential benefit that can be reduced through citizen or full membership involvement. Furthermore, the question that arises is how ecological citizenship can be used to build a democratic institution that is large and inclusive.

Dobson also believes that in the case of urban politics, ecological citizenship is transformed from cosmopolitanism, which focusses on the distribution and redistribution of democratic institutions for environmental equality, to post-cosmopolitanism, which focusses on commitment to citizens beyond the state (Dobson, 2004). Of course, this occurs because Dobson recognizes that in a liberal democracy, the opportunity to exploit the environment for economic gain is greater than that of ecological citizenship itself in terms of environmental sustainability.

As a result, ecological citizenship is a contingency in which citizens are seen as plural and “differentiated.” This is a term coined by Iris Marion Young, who contends that the primary form of citizen groups is “difference” (Young, 1990, 2000, 2011; Appiah et al., 2007). The commitment that post-cosmopolitanism bases on Dobson’s frame of ecological citizenship is insufficient to accommodate different types of citizens who have different perspectives on their environment. In the sense that the environment is not only viewed scientifically as a need for sustainability in order to avoid climate change but also from an ethical standpoint, which sees an existence coexisting with human beings.

The “Differentiated Ecological Citizenship” model is a way of thinking about diversity and sustainability. The deadlock in Dobson’s post-cosmopolitanism is seeing citizens as homogeneous, rather than heterogeneous, with a commitment, obligations, and rights to preserve the environment, as a form of anticipation of developmentalism in liberal democracy. This viewpoint limits the need for diversity among environmental citizens. It is “indigenous people” in its most extreme form in understanding the relational diversity of membership in seeing its environment. They see that threats to environmental damage, such as the global community’s concern about climate change and ecosystem balance, are not on the agenda. They have a better understanding that the environment is an inseparable component of life that cannot be exploited. In the context of democracy, the diversity of thoughts on the form of citizens who are excluded in a rationalistic framework.

As a result, this research, which views ecological citizenship as a form of contingency, has the potential to broaden the definition of ecological citizenship beyond what Dobson offers in a post-cosmopolitanism framework of ecological citizenship. By combining the context of a new capital’s relocation in Indonesia with the plural groups of citizenship in Indonesia, culture, race, religion, and identity can all differ from one group to the next. In this context, broadening the definition of ecological citizenship becomes an urgent necessity in order to accommodate all of the competing membership forms that exist. The expansion of this form also allows for inclusiveness in the contestation and public discourse surrounding the development of a new capital city in East Kalimantan. This research also demonstrates the academic contribution to the theory of ecological citizenship. As an example of a practical contribution. This research examines the various forms of ecological citizenship in Indonesia. Specifically, providing an analysis of ecological citizenship participation in Indonesia.

5 Activism for sustainability

One of the most interesting findings from the researcher’s interviews with local informants is information about the daily relationships of environmental activists, aside from WALHI and Greenpeace, as representatives of environmental NGOs, namely JATAM (Jaringan Advokasi Tambang/Mining Advocacy Networks).5 JATAM is a non-governmental organization (NGO) in East Kalimantan concerned with environmental issues. Pradarma Rupang is the JATAM Kaltim Disseminator, and he is involved in research, advocacy, and protests against mining policies and activities carried out by large corporations in East Kalimantan (interview with informant).6

According to several JATAM reports, since the central government’s decision to relocate the national capital to Penajam Paser, massive changes in land ownership have occurred, with large-scale investments made by investors from outside Kalimantan, the majority of which were dominated by large corporations from Jakarta and Surabaya, to acquire land around Penajam Paser. This, of course, has caused land prices in East Kalimantan to increase. Eventually, these lands will be converted into commercial activities, which is expected to worsen the situation in East Kalimantan, adding to environmental activists’ concerns.

The East Kalimantan Provincial Government also faces numerous challenges in issuing permits to companies seeking to exploit nature. The local government has granted at least 161 exploitation permits, and another issue is that there are 2.4 million hectares of abandoned areas as a result of approximately 800 land exploitation permits that have been abandoned with no effort to improve the environment.7 BAPPENAS claims that the new national capital will be an ideal city, with a minimum of 50% green open space integrated with the environmental landscape in accordance with the framework of the forest city development concept that the government always campaigns for. However, this plan has not been presented in the form of a concrete development program, so it is not clear how the government plans to build urban housing without disturbing the local ecosystem (News.mongabay.com, 2019). What has happened is a large-scale project in Kalimantan, making the forests where animals live fragmented, including eliminating corridors that are vital for animals (Alamgir et al., 2019).

The current urgency of ecological citizenship is the most visible form of a shared issue in placing the environment not only as a discourse for a development project that began in 2021 despite the COVID-19 pandemic and is scheduled to be completed in 2024, coinciding with the end of Jokowi’s presidential term, but as an initial effort to fully understand the formation of public engagement as a way of anticipating the potentials that could occur if environmental sustainability is not prioritized in the relocation of the new capital. This research also attempts to map a variety of current and future issues, such as conflict between indigenous peoples over land and their sustainability, economic conflicts between migrants and local communities, and environmental damage caused by converting land into business activities to meet the needs of more than 800,000 bureaucrats who will migrate, and to address the impact of flooding caused by environmental damage in surrounding cities such as Samarinda, Balikpapan, and Kutai Kartanegara, which has yet to be resolved, as well as the issue of the need for clean water that has emerged later.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided written informed consent for participation in the study.

Author contributions

LA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to show their gratitude towards the supervisors and colleagues who have been a part of this writing journey for their endless support and assistance during the process of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The author conducted an interview by phone with a local researcher at Mulawarman University.

2. ^See http://floodlist.com/asia/indonesia-floods-samarinda-may-2020 and https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/01/15/more-than-7000-affected-by-flooding-landslides-in-samarinda.html.

3. ^Ekuatorial.com, 2022.

4. ^See the reports from By NANDA and YE MON in December 2019. https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/official-residences-in-nay-pyi-taw-left-to-ruin/.

5. ^One of the local environmental activism in east Kalimantan (see https://www.jatam.org/tentang-kami).

6. ^Interview with a local researcher at Mulawarman University.

7. ^See https://www.liputan6.com/regional/read/4047118/catatan-aktivis-lingkungan-soal-ibu-kota-baru-di-kaltim.

References

Alamgir, M., Campbell, M., Sloan, S., Suhardiman, A., Surpiatna, J., and Laurance, W. F. (2019). High risk infrastructure projects pose imminent threats to forests in Indonesia Borneo. Sci. Rep. 9:140. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36594-8

Anugrah, I. (2019). Out of sight, out of mind? Political accountability and Indonesia’s new capital plan. Available at:https://www.newmandala.org/out-of-sight-out-of-mind-political-accountability-and-indonesias-new-capital-plan/.

Appiah, K. A., Benhabib, S., Young, I. M., and Fraser, N. (2007). Justice, governance, cosmopolitanism, and the politics of difference: Reconfiguration in a transnational world. Cambridge, MA.W.E.B. Du Bois Lectures.

Bappenas. (2019). Dampak Ekonomi dan Skema Pembiayaan Pemindahan Ibu Kota Negara. Dialog Nasional II: Menuju Ibu Kota Masa Depan: Smart, Green and Beautiful.

Betts, K. (1990). Book reviews: CITIZENSHIP. J.M. Barbalet. Milton Keynes. J. Sociol. 26, 291–294. doi: 10.1177/144078339002600233

Campante, F. R., Do, Q. A., and Guimaraes, B. (2013). Isolated capital cities and misgovernance: theory and evidence. Available at:https://ssrn.com/abstract=2210254

Carme, M. E. (2008). Promoting ecological citizenship: rights, duties and political agency. ACME 7, 113–134.

Dobson, A., and Eckersley, R. (2006). Political theory and the ecological challenge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hackbarth, T. X., and de Vries, W. T. (2021). An evaluation of massive land interventions for the relocation of capital cities. Urban Sci. 5:25. doi: 10.3390/urbansci5010025

Hikmawan, M. D., Indriyany, I. A., and Hamid, A. (2021). Resistance against corporation by the religion-based environmental movement in water resources conflict in Pandeglang, Indonesia. Otoritas 11, 19–32. doi: 10.26618/ojip.v11i1.3305

Kang, J. (2012). A study on the future sustainability of Sejong, South Korea’s multifunctional administrative city, focusing on implementation of transit oriented development, Uppsala University. Uppsala

Lee, D. (2011). Political leadership during a policy shift: the effort to revise the Sejong City plan. Korean J. Policy Stud. 26, 1–19. doi: 10.52372/kjps26101

Minister of National Development Planning . (2019). Dampak ekonomi dan skema pembiayaan pemindahan ibu kota negara. Dialog Nasional ii: menuju ibu kota masa depan: smart, green and beautiful. Jakarta: Kementerian PPN/Bappenas.

Moser, S. (2010). Putrajaya: Malaysia’s new federal administrative capital. Cities 27, 285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2009.11.002

News.mongabay.com . (2019). Available at: https://news.mongabay.com/2019/08/red-flags-as-indonesia-eyes-relocating-its-capital-city-to-borneo/

Potter, A. (2017). Locating the government: capital cities and civil conflict. Res. Politics. 4:2053168017734077:205316801773407. doi: 10.1177/2053168017734077

Saputra, T., Zuhdi, S., Kusumawardani, F., and Novaria, R. (2023). The effect of economic development on illegal gold Mining in Kuantan Singingi, Indonesia. J. Gov. 8, 31–42. doi: 10.31506/jog.v8i1.16883

Shimamura, T., and Mizunoya, T. (2020). Sustainability prediction model for capital city relocation in Indonesia based on inclusive wealth and system dynamics. Sustainability 12, 1–25. doi: 10.3390/su12104336

Siburian, R. (2012). Pertambangan Batu Bara: Antara Mendulang Rupiah Dan Menebar Potensi Konflik. J. Masy.Indones. 38, 69–92. doi: 10.14203/jmi.v38i1.297

Siburian, R. (2015). “Emas Hitam”: Degradasi Lingkungan dan Pemarginalan Sosial “black gold”: environmental degradation and social marginalization. J. Penelit. Kesejaht. Sos. 14, 1–19.

Sloan, S., Campbell, M. J., Alamgir, M., Lechner, A. M., Engert, J., and Laurance, W. F. (2019). Trans-national conservation and infrastructure development in the heart of Borneo. PLoS One 14, e0221947–e0221922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221947

Smith, G. (2004). “Liberal democracy and sustainability” in Environmental politics. eds. M. Wissenburg and Y. Levy (London: Routledge), 386–409.

Steinberg, F. (2007). Jakarta: environmental problems and sustainability. Habitat Int. 31, 354–365. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2007.06.002

Stokke, K. (2017). Politics of citizenship: towards an analytical framework. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. 71, 193–207. doi: 10.1080/00291951.2017.1369454

Suling, C. F., Purnomo, E. P., Hubacek, K., and Anand, P. (2023). The influence of “renewable energy directive II” policy for the sustainability of palm oil industry in Indonesia. J. Gov. 8, 330–347. doi: 10.31506/jog.v8i3.19930

Teo, H. C., Lechner, A. M., Sagala, S., and Arceiz, A. C. (2020a). Environmental implications of Indonesia's new planned capital in East Kalimantan, Borneo Island, Resilience Development Initiative. Jawa Barat

Teo, H. C., Lechner, A. M., Sagala, S., and Campos-Arceiz, A. (2020b). Environmental impacts of planned capitals and lessons for Indonesia’s new capital. Land 9, 1–17. doi: 10.3390/land9110438

van de Vuurst, P., and Escobar, L. E. (2020). Perspective: climate change and the relocation of Indonesia’s capital to Borneo. Front. Earth Sci. 8, 1–6. doi: 10.3389/feart.2020.00005

Young, I. M. (1990). Justice and the politics of difference Iris. Princeton University Press. New Jersey

Keywords: new capital city, relocation, ecology, citizenship, sustainability, Indonesia

Citation: Agustino L, Hikmawan MD and Silas J (2024) Is it possible for sustainability? The case from the new capital city of Indonesia. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1362337. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1362337

Edited by:

Muhlis Madani, Muhammadiyah University of Makassar, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Ali Roziqin, Universitas Muhammadiyah Malang, IndonesiaAhmad Harakan, Muhammadiyah University of Makassar, Indonesia

Srirath Gohwong, Kasetsart University, Thailand

Copyright © 2024 Agustino, Hikmawan and Silas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Leo Agustino, bGVvLmFndXN0aW5vQHVudGlydGEuYWMuaWQ=

Leo Agustino

Leo Agustino M. Dian Hikmawan2

M. Dian Hikmawan2