94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 09 August 2024

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1360265

This article is part of the Research TopicPopulism and the Border: Theoretically and Empirically Dissecting Strategies of Exclusion and the Recreation of IdentitiesView all 5 articles

Scholarly work on populism and borders have largely followed separate paths so far. This article aims at bringing together these two strands by means of an empirical analysis of individual attitudes on a re-bordering policy in the context of a national-populist mobilization against the free movement of persons. Recent contributions on border regions in affluent countries have highlighted an increased opposition to European integration that is fueled by political actors from the populist radical right. We hypothesize that border residents are more opposed to the free movement of persons than non-border residents the more they are exposed to the influx of cross-border workers. The empirical analysis draws on a representative post-vote survey from the so-called “VOTO studies” on a popular initiative by the radical right that demanded Switzerland’s termination of the free movement of persons with the European Union in 2020. In line with our hypothesis, we find a significant positive interaction effect between border residence and the share of cross-border commuters on the likelihood to vote in favor of this proposition. While border residence turns out to be insufficient to foster increased re-bordering attitudes, we show that the magnitude of incoming cross-border commuters makes a difference.

As Olivas Osuna (2022) has recently pointed out, the interdisciplinary literatures on populism and borders have followed largely separate paths so far. While the numerous scholars working on populism have neglected the explicit role played by (national) borders (Mazzoleni et al., 2023), border studies have only recently put emphasis on the politicization of borders in general and their populist mobilization in particular (Casaglia et al., 2020; Scott, 2020).

This article seeks to advance the academic literature by bringing together these two strands. More specifically, it aims to bridge the concept of national populism and the notion of the border (Mazzoleni et al., 2023). National populism basically refers to forms of elite contestation of mainstream politics by political actors in the name of a homogeneous people, understood as a national entity (Eatwell and Goodwin, 2018). The latter characteristic implies that national populists are not only opposed to those “on the top” (i.e., established elites) but also to those “outside” as Brubaker (2020) put it in a nutshell. It is precisely this exclusionary aspect that ultimately deals with the threatening “external outside” as well as with the “internal outside,” i.e., with the question of who is not considered to be part of a given national community. Yet these basic questions refer to border issues. Hence, national populism and borders – be they territorial, political, or social – are fundamentally intertwined (Olivas Osuna, 2022). It thus seems both obvious and promising for researchers to explicitly combine these two concepts in their theoretical and empirical work.

In this article, we will address the role played by national borders regarding individual attitudes in the framework of a national-populist mobilization against the free movement of persons. As we will outline in the next section, we argue that such manifestations must be appreciated in a broader political context, given that we conceive of them as a counter-mobilization by national populists against the de-bordering policies (Popescu, 2012) that had previously been enacted by established elites. This populist backlash refers to demands for a decisive re-bordering (i.e., policies of boundary closure or retrenchment) that mainly includes economic protectionism, political isolationism, and cultural retrenchment in order to restore national sovereignty. While not necessarily limited to a given party family, existing research suggests that such political demands are primarily articulated by political actors from the radical right (e.g., Kriesi et al., 2008; Casaglia et al., 2020).

Our empirical analysis focuses on a direct-democratic vote in Switzerland, a country almost entirely surrounded by EU member states. Our case is the so-called “limitation initiative,” a popular initiative launched by the radical right that aimed at Switzerland’s withdrawal from the free movement of persons treaty with the EU. Based on our reading of the state of the art, we hypothesize that border residents are more opposed to the free movement of persons than non-border residents the more they are exposed to the influx of cross-border workers. The data for our analyses stem from a post-vote survey that was conducted among a representative sample of 1,513 eligible voters in the weeks following the popular vote held in September 2020. In line with our expectations, we find a significant positive interaction effect between border residency and the share of cross-border commuters on the likelihood to accept the proposition under scrutiny. Accordingly, voters living at the border are shown to be more likely to oppose the free movement of persons than non-border residents, the higher the percentage of cross-border commuters in their municipality of residence.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. In the next section, we outline our argument about the backlash by national populists against the de-bordering policies enacted by established elites. Thereafter, we develop the hypothesis that posits a positive interaction effect of border residency and the share of cross-border commuters on the opposition toward the free movement of persons. We subsequently present the case study we selected for this article, followed by the data and the measures of the empirical analysis. After reporting the results of our bivariate and multivariate analyses, we discuss the main implications of our empirical findings in the article’s concluding part.

Populism is currently one of the most intensively researched phenomena in the social sciences. Motivated by the emergence of numerous successful populist actors in various democracies around the world, the study of populism has received unprecedented academic attention in recent years. While there is a heated definitional debate that notably revolves around the question whether populism shall be regarded as a discourse (Laclau, 1977), an ideology (Mudde, 2007), a communication style (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007), or a political strategy (Weyland, 2001), scholars seem to agree on the core characteristics (Katsambekis, 2022). Indeed, a common understanding has emerged according to which populism of any ideological stripe refers to a Manichean antagonism between two crucial social groups – the “good” people and the “bad” elites (Canovan, 1981, 2005). In line with these minimalist features, we take an actor perspective in this article by considering populism to be a political worldview that pits the former group against the latter.

Yet the vast literature has neglected the role of borders for political mobilizations by national-populist actors so far (Mazzoleni et al., 2023). Several scholars nevertheless regard economic, cultural and political processes of globalization as crucial determinants of the current surge of populism (Mény and Surel, 2000; Kübler and Kriesi, 2017; Steger, 2019). According to this line of reasoning, the populist challenge to mainstream politics comes about as a consequence of increased international economic competition (such as increased division of labor, neoliberal reforms at the domestic level, and liberalization of financial markets), growing cultural diversity (mainly due to growing levels of immigration from ever more distant places) and the supra-nationalization of politics (notably the European integration process). Taking a Rokkanean perspective, Kriesi et al. (2008) posited that globalization can be regarded as a critical juncture that creates potentials for populist mobilization in Western Europe.

More specifically, the hegemony of neoliberal, cosmopolitan and multicultural ideas by globalist elites have led to a decisive de-bordering over the last decades. However, the erosion and disappearance of national borders has increasingly met with sharp opposition, leading to a populist backlash. At the level of political actors, populists of various ideological stripes but especially those from the radical right have made the claim that de-bordering policies have ultimately benefited the elites to the detriment of the “pure people,” understood as homogeneous national communities (Mazzoleni et al., 2023).1

Rhetorically, national-populist actors typically put emphasis on “taking back control” of national borders (Kallis, 2018) in order to reclaim a “lost” territorial sovereignty that has slipped into the hands of multinational companies and foreign capital in economic terms, cosmopolitan elites in cultural terms and supranational institutions in political terms (Casaglia et al., 2020). In this context, Olivas Osuna (2022) has convincingly argued that borders and bordering practices are central elements of the populist worldview and its manifestations.

At the level of citizens, an increasing number of contributions also views the rise of populism as a rebellion against processes of globalization by voters whose situation has deteriorated as a direct consequence of the opening of national borders (e.g., Ford and Goodwin, 2014; Hobolt, 2016; Santana and Rama, 2018). In a similar vein, Spruyt et al. (2016) have argued that the sharp distinction between the ordinary people and the established elites renders populism in Western Europe a typical attitude of individuals who suffer from being overwhelmed and disoriented by these changes, particularly those who have been placed in a weak and vulnerable (economic) position, as they feel their voice does not matter (anymore) in the realm of politics. This widespread disenchantment with the effects of economic globalization, immigration and supranational integration translates itself into popular demands for re-bordering.

This article proposes to break new ground by considering the role played by border residence at the level of citizens when explaining attitudes towards the free movement of persons in the context of European integration. To that end, we will focus on a national-populist mobilization that called for a decisive re-bordering policy in a direct-democratic vote in Switzerland (see next section). In this section, we develop our hypothesis. Recent contributions that deal with the more affluent side of border regions have highlighted an increased opposition to European integration that is fueled by political actors from the populist radical right against the free movement of persons, which implies above all increased labor market competition by cross-border commuters. We will thus hypothesize that border residents are more opposed to the free movement of persons than non-border residents the more they are exposed to the influx of cross-border workers.

Borderlands can nowadays be regarded as sources of conflict (Mazzoleni and Mueller, 2017, p. 175). In the context of European integration, the latter are intrinsically linked to the elimination of internal borders, one of the EU’s guiding principles. Indeed, since its creation, the European Union has been driven by the idea that cross-border flows contribute to stability, prosperity, and territorial unity (Hajer, 2000; Decoville and Durand, 2016). It has therefore engaged in decisive de-bordering policies notably by lowering customs tariffs and encouraging the free movement of goods, capital, services, and people within the framework of the European Single Market. At the same time, it needs to be mentioned that such internal de-bordering was often accompanied by a re-bordering at the EU’s external borders, notably through tariffs and restrictive asylum rules (Schimmelfennig, 2021).

People who live in proximity to national borders experience the consequences of de-bordering policies on a daily basis (Kuhn, 2012; Durand et al., 2020). Due to this high degree of visibility, border residents are likely to develop pro-European or Eurosceptic attitudes depending on whether they perceive the opening of borders that allows for unrestricted movement as positive or negative (Dürrschmidt, 2006). As Bürkner aptly describes (Bürkner, 2020, p. 552), border regions can be regarded as “breeding grounds of Euroscepticism on the one hand and facilitators of its reduction on the other hand.”

Although such diverging expectations are present in the literature (see also Kuhn, 2011), the negative consequences have long remained marginal. On the contrary, the dominant discourse of a “Europe of flows” (Hajer, 2000) has put emphasis on the benefits of cross-border integration for participating countries in general and for border regions in particular. This may be due to the fact that survey research has rather consistently established that people living in borderlands are less inclined to hold Eurosceptic attitudes than residents in more central areas of a given country. As a matter of fact, Díez Medrano (2003, pp. 243–246) documents significant positive effects for residents of regions that border another EU member state, hence corroborating previous findings reported by Schmidberger (1997) and Gabel (1998). More recently, multilevel analyses of Eurobarometer data by Kuhn (2012) show that such positive effects apply to German border districts but not to French ones.

Based on transactionalist theories by Deutsch et al. (1957), Kuhn (2011, 2012) has argued that pro-European attitudes are fostered by the greater opportunity of border residents to engage in transnational networks and interactions; such people are prone to embracing European integration as a new source of opportunities. By contrast, individuals who interact less frequently with people beyond national borders may construe transformations as threats and are therefore more likely to develop higher levels of Euroscepticism. Contact theory (Allport, 1954) may provide another explanation for this finding: proximity affords further opportunities for direct contact that reduces prejudice through familiarity, likeability and trust under certain conditions. In other words, fears and prejudices toward unknown population groups can be reduced through regular contact and mutual exchange (see Cortina, 2020 for an application of this approach on attitudes towards the US-Mexico border wall).

While the dominant discourse has emphasized the benefits of cross-border integration, it has neglected some possible far-reaching negative consequences. However, this may change due to a recent encompassing empirical analysis that showed that living in a national border region in the EU is positively associated with Euroscepticism (Nasr and Rieger, 2023) as well as a couple of studies conducted by researchers involved in the field of European cross-border regions that highlight some problematic aspects of de-bordering policies. The latter suggest that the opening of borders may have a negative impact on living conditions of border residents and therefore foster Euroscepticism. Generally speaking, these instructive case studies draw the scholarly attention to negative externalities of de-bordering policies (Sohn, 2014).

Such externalities are arguably particularly pronounced in areas that are characterized by considerable economic disparities across borders. If a country offers significantly better employment opportunities and higher wage levels, it is likely to attract a large influx of labor immigrants and cross-border workers. While this influx may yield beneficial economic effects in terms of economic growth and competitiveness for the host country (e.g., Beerli et al., 2021), residents at the border may suffer from negative externalities in various issue domains (Decoville and Durand, 2019; Sohn, 2020; Sohn and Scott, 2020). In addition to increased competition on the labor market, these may above all be perceptible when it comes to transportation (e.g., car congestion, overcrowded public transport), housing (e.g., higher rents, lack of affordable housing), spatial planning (e.g., urban sprawl) and security (e.g., increased delinquency and drug-trafficking by non-residents). Taken together, residents on the more affluent side of a border region may thus come under increased “pressure” and “stress” as a consequence of enacted de-bordering policies.

As Sohn (2014) has noted in the cases of Luxembourg and Switzerland, increased cross-border interactions do not necessarily result in lowering disparities in terms of wealth. This is probably due to the fact that the areas on either side tend to specialize according to their comparative advantages (Durand et al., 2020), which are often rooted in their legal, fiscal, economic and symbolic peculiarities (Moullé and Reitel, 2014). In light of the persistence of territorial discontinuities, the “victims” of cross-border integration are likely to hold Eurosceptic attitudes by demanding “re-bordering” policies with the aim of protecting a secure and familiar “inside” from a dangerous and chaotic “outside” (Sohn, 2020). It is typically the populist radical right that mobilizes for the protection from the risks initiated by the “others” in order to “take back control” of the borders (Kallis, 2018; Lamour, 2020).

These considerations suggest that the specific configuration at a given border needs to be taken into account. More specifically, high levels of economic discrepancy may provide a potential for a backlash in terms of de-bordering policies, at least on the more affluent side of borderlands. This expectation is in line with a recent study by Vasilopoulou and Talving (2019) on individual attitudes within the EU that showed that citizens in richer member states are less likely to support the free movement of persons, a result the authors attribute to the fact that affluent countries tend to attract much more migrants and cross-border commuters than poorer ones.

To summarize, the state of the art suggests no direct effect between border residence and individual attitudes on the free movement of persons. While systematic empirical work on large-scale surveys points to a rather positive relationship between border residence and support for European integration in general, more recent research and, particularly, case studies from border regions suggest possible negative effects, especially as far as the issue of the free movement of persons on the more affluent side of borderlands is concerned. In these contexts, the magnitude of cross-border commuters appears to play a crucial mediating role, however. Based on these considerations, we hypothesize that border residents are more likely to be opposed to the free movement of persons than non-border residents the more they are exposed to the influx of cross-border workers. In other words, the sole fact to live at the border is not sufficient to foster increased attitudes against the free movement of persons. Indeed, individuals who live at the more affluent side of a given border that is characterized by a low level of influx of cross-border commuters – be it due to natural obstacles such as seas and mountains or for reasons that are related to the local labor market structure – can be expected to be largely spared the negative externalities that we have just described above. By contrast, opposition to the free movement of persons is likely to be much more pronounced by border residents who experience a large influx of cross-border commuters. It is thus the number of incoming cross-border commuters that is expected to make a difference. In statistical terms, we posit a positive interaction between border residence and the magnitude of cross-border commuters. Hence, our hypothesis reads as follows:

H: Border residents are more likely to oppose the free movement of persons than non-border residents the more they are exposed to the influx of cross-border commuters.

This article proposes to look at a specific national-populist mobilization. This choice is based on the fact that such instances have played a major role in the backlash against globalization in general and European integration in particular, as is probably best illustrated by the 2016 Brexit referendum. This event also suggests that the free movement of persons has become a sensitive issue in many parts of Western Europe since the turn of the millennium (Vasilopoulou and Talving, 2019; Lutz, 2021). As will be elaborated in the second part of this section, this article focuses on the context of Switzerland by considering the so-called “limitation initiative” that demanded Switzerland’s withdrawal from the free movement of persons treaty with the European Union in 2020.

While not being an EU member, it can nevertheless be argued that Switzerland takes part in the European integration process (Dardanelli and Mazzoleni, 2021). This is above all due to the bilateral agreements with the EU that include the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons (AFMP) that entered into force in 2002. There is a substantial gap between Switzerland and its four largest neighboring countries (Germany, France, Italy, and Austria) in terms of economic prosperity. Comparatively higher wage levels make Switzerland an attractive place for mobile workers from abroad, an economic disparity at the heart of Western Europe that presents a prime configuration for the study of bordering policies. The AFMP has boosted immigration from the EU/EFTA member states: in 2002, when the agreement came into force, just under 900,000 citizens from these countries lived in Switzerland. Since then, their number has increased by more than 60 per cent to 1.5 million. With slightly more than 20 per cent, Switzerland is currently only second to Luxembourg as the European country with the highest share of foreigners from the EU/EFTA zone in the labor force. In addition, the number of cross-border workers more than doubled between 2002 and 2023, rising from 165,000 to 390,000.

This sharp rise has been strongly politicized in Swiss politics in the past few decades. A crucial role has been played by the country’s largest party, the radical right Swiss People’s Party (SVP), with a vote share of 27.9 per cent in the most recent national elections (Bernhard, 2024). In this article, we take a closer look at a popular initiative by the populist radical right that basically demanded the withdrawal from the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons with the EU. This ballot measure was a response to the softened implementation of the popular initiative “against mass immigration” by the Swiss Parliament that was accepted at the ballot boxes in 2014. The SVP (together with the Campaign for an Independent and Neutral Switzerland (AUNS), a citizen group to which the party has close ties) launched the popular initiative “for moderate immigration,” commonly known as the “limitation initiative.” This proposition called for an independent regulation of immigration and thus ending the AFMP. The transitional provision formulated in the initiative stipulated that the agreement should be terminated by mutual agreement with the EU, if possible, within 12 months. Should this not be possible, the transitional provision required that the agreement be unilaterally terminated within 30 further days.

With the exception of the radical right, the remaining parties recommended voters rejecting the limitation initiative, a recommendation backed by the Federal Council and the most important interest groups (i.e., employers’ associations, labor unions and social movements). Initially planned in May 2020, the vote on the limitation initiative had to be postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. After a rather heated campaign, the popular initiative was rejected by 61.7 per cent of voters on 27 September 2020. Turnout stood at 59.5 per cent – an exceptionally high participation rate reached by no other ballot in the same year (on average, participation in direct-democratic votes was 49.3 per cent in 2020). As is usually the case in EU-related votes in contemporary Switzerland, the Eurosceptic share was highest in the Italian-speaking part. In this linguistic region, the limitation initiative was accepted by a margin of 53.2 per cent. By contrast, the proposition was rejected in the German-speaking part (by 60.5 per cent) and even more heavily in the French-speaking part (68.6 per cent).

To investigate our hypothesis, we rely on data from the so-called “VOTO studies”, i.e., CATI surveys that took place after each ballot at the federal level of Switzerland from September 2016 to September 2020. On behalf of the Federal Chancellery, these VOTO studies were conducted by the Swiss Centre of Expertise in the Social Sciences (FORS), the Centre for Democracy Studies Aarau (ZDA) at the University of Zurich, and LINK, a pollster from Lucerne (Switzerland). We use the data that were gathered in relation to the ballot held on 27 September 2020 (FORS/ZDA, 2020). The sample was randomly drawn by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO). 1,513 citizens participated in the post-vote survey (response rate: 45 per cent). There is an overrepresentation of respondents from two language minorities, i.e., the French- and the Italian-speaking parts of the country.2 For the sake of representativeness, we decided to apply a design weight that corrects for the stratified sampling structure in terms of language regions.

Let us now turn to the measurement of the indicators. The dependent variable refers to individual vote choice. We include those 1,163 respondents who reported either having accepted (code “1”) or rejected (code “0”) the limitation initiative. Non-voters as well as the small numbers of voters who voted blank, did not vote for this proposal (but other proposals on the same day), answered “I do not know” or did not respond to this question are excluded from our analysis.

Regarding the independent variable, we rely on a multiplication of two indicators – border residence status and the share of cross-border commuters. Both are measured on the municipal level. As to the former, we have a dichotomous measure that distinguishes between those respondents whose municipality of residence is located at a national border (code “1”) and those for whom this is not the case (code “0”). Border residents account for a substantial minority in this survey, as this status holds true for 11 per cent of respondents in our weighted sample. With respect to the latter, we integrate an indicator provided by the Federal Statistical Office that captures the share of cross-border commuters based on the total number of jobs per municipality. In our weighted sample, the share of cross-border commuters ranged from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 68.2 per cent, with a mean of 4.5 per cent of cross-border commuters per municipality.

Borrowing from previous work (notably Gabel, 1998; Kriesi et al., 2008; Kuhn, 2011, 2012; Sciarini, 2021), we include several control variables. We basically take into account socio-structural and political factors.

As to the former, we first take into consideration the effects of gender (woman = 1, man = 0), age and level of education (by relying on a 10-level classification of the Federal Statistical Office). Regarding these individual characteristics, Euroscepticism has previously been found to be most prevalent among lower educated citizens. Somewhat less consistently, this also tends to apply to men and elderly people.

Second, we control for the effect of unemployed status and nationality at birth. Whereas unemployed people are likely to be particularly Eurosceptic out of frustration with their current situation (see Dijkstra et al., 2020 for an aggregate-level analysis), respondents who held another nationality than the Swiss one at birth (i.e., respondents who were naturalized) are expected to be more resistant to Euroscepticism because of their personal migration/transnational background (Kuhn, 2011, 2012).

Third, the affiliation to language regions needs to be accounted for. Indeed, this aspect has played a crucial role in Switzerland in votes on European integration (Mazzoleni, 2021; Sciarini, 2021). In particular, Euroscepticism has turned out to be most pronounced in the Italian-speaking language region since the 1992 popular vote on a possible Swiss membership in the European Economic Area (EEA), and especially since the mid-2000s (Mazzoleni and Pilotti, 2015).

As far as the effects of individual political factors are concerned, we introduce five factors into our statistical models – political interest, trust in the government, ideology, party identification, and a specific political value orientation. Political interest is measured on an increasing four-level scale (“not at all interested,” “not very interested,” “somewhat interested,” “very interested”). Trust in government is measured on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 “no trust at all” to 10 “full trust.” Sciarini (2021) found that there is a slight positive relationship between the level of political interest and pro-European integration decisions in direct-democratic votes in Switzerland and a strong positive relationship between increasing trust in the government and pro-European vote decisions.

For political ideology, we use the respondents’ self-positioning on a left–right scale that ranges from 0 (“completely left”) to 10 (“completely right”). Scholarly work indicates that Euroscepticism generally increases the more Swiss citizens place themselves to the right of this scale (Sciarini, 2021). Yet this seems to be less obvious in other Western European countries.3

As to party identification we distinguish between eight categories: sympathizers with the six largest parties of the country (i.e., Swiss People’s Party (SVP), Social Democrats (SP), Liberals (FDP), Christian Democrats (CVP),4 Greens (GPS) and Green Liberals (GLP)), sympathizers with any other party (“others”) as well as “independents.” Followers of the SVP have been found to pronounce themselves for Eurosceptic positions more frequently than voters who favor one of the other large parties (Sciarini, 2021).5

Finally, we decided to include a basic political value orientation. Sciarini (2021) has shown that voting choices on EU-related issues are strongly influenced by citizens’ placement on the fundamental conflict between an open and a closed Switzerland, with those who favor the latter more likely to opt for Eurosceptic decisions. This value orientation was measured using a six-point answer scale that ranges from 1 “completely in favor of an open Switzerland” to 6 “completely in favor of a closed Switzerland.” In the theoretical context of our contribution, this indicator can be considered to capture the basic antagonism between de-bordering and re-bordering policy preferences (Popescu, 2012).

Table 1 provides an overview of the bivariate relations between the selected explanatory variables and voters’ choices regarding the limitation initiative. To make the key figures more intuitive, we formed categories for the share of cross-border commuters and age, and we reduced the numbers of categories for education,6 trust in government and left–right self-positioning. The variable measuring whether citizens are rather in favor of an open or a closed Switzerland (originally a 6-point answer scale, see above) was dichotomized for the sake of our bivariate analysis. As is visible from the last column, Cramér’s V tests indicate that the bivariate relationships between age, education, language region, trust in government, left–right self-placement, party identification and the basic value orientation “open vs. closed Switzerland” on the one hand and vote choice regarding the limitation initiative on the other are statistically significant. These are thus all possibly crucial determinants of vote choice for the present analysis, i.e., they serve as meaningful control variables. Apart from that, the directions of the control variables are consistent with previous research: the ballot measure of interest was more likely to be accepted by the elderly citizens and those with a lower education level. In addition, the acceptance rate was higher among respondents from the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland than among those from both the German and French language regions. Finally, when it comes to the political factors, the “yes” share increased the less trust citizens have in the federal government, the more their political ideology was to the right, among sympathizers of the SVP and citizens who are in favor of a closed Switzerland.

Most importantly, when looking at our independent variables, respondents who live in a border municipality were not more likely to vote in favor of the limitation initiative (34 per cent “yes” votes) than non-border residents (39 per cent) – it was rather the other way around. This bivariate relationship is however not significant. Neither was there a clear relationship between the share of cross-border commuters in a municipality and citizens’ vote decisions, as it seems that the yes share was higher in municipalities with (almost) no cross-border commuters and in those with quite a high share (>20 per cent). The bivariate relationship between the share of cross-border commuters and vote choice proved to be insignificant, too (see Table 1). Based on these bivariate analyses, there is thus already an indication that our two independent variables did not influence vote choice, when we take them as individual factors.

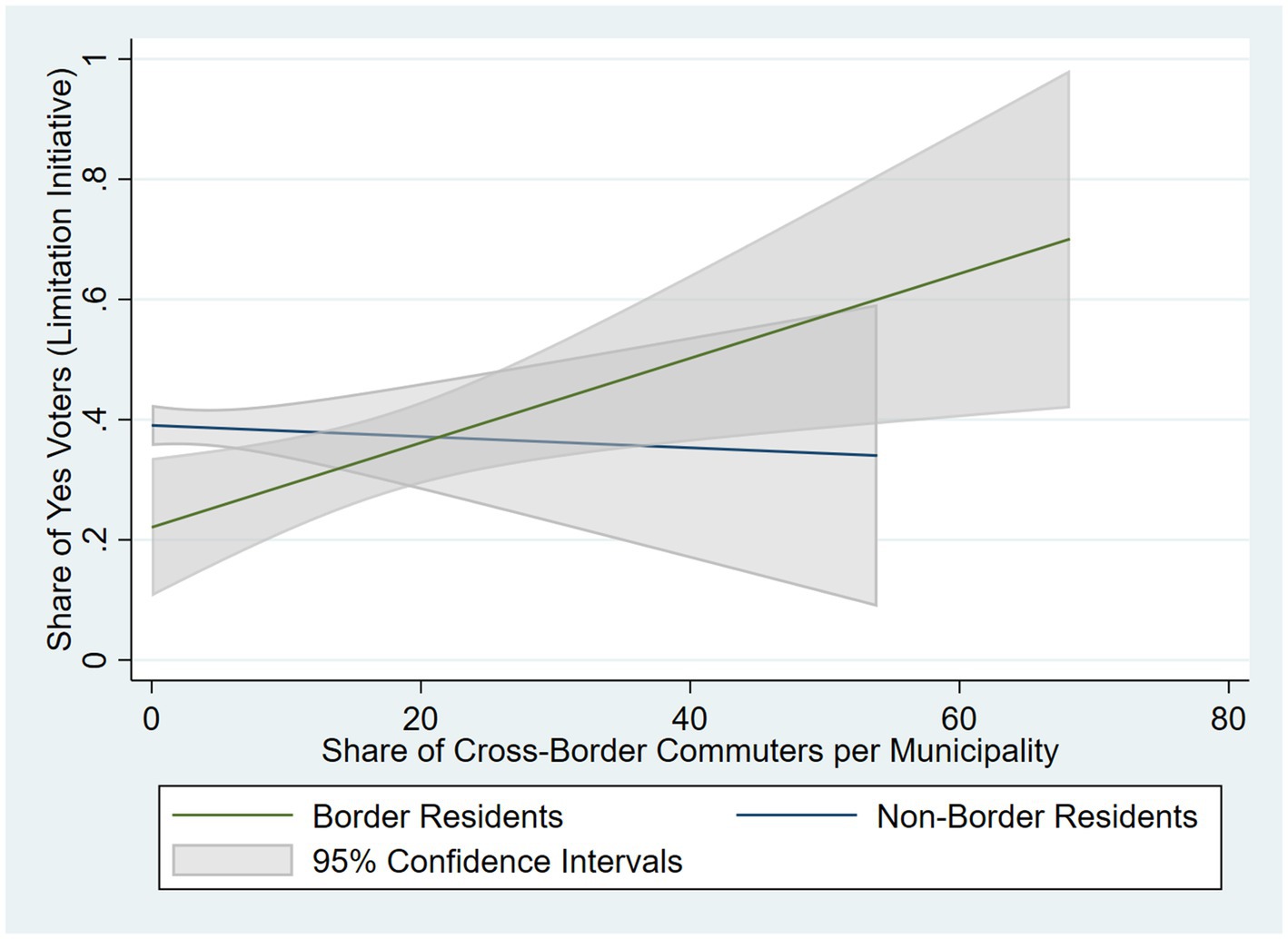

However, when we plot the relationship between a yes vote for the limitation initiative and the share of cross-border commuters in citizens’ municipalities for two distinct groups, border residents and non-border residents, it becomes clear that taken together, the two independent variables might very well have an influence on vote decisions. Figure 1 shows that the share of yes voters remains rather stable in the group of citizens who do not live in border municipalities (blue line) independently of the share of cross-border commuters in their municipality. On the contrary, there is a sharp increase in the share of yes voters the more cross-border commuters work in the municipality of citizens who live at the border (green line). This is first graphical indication for the interaction hypothesis we postulated above.

Figure 1. Share of yes voters (limitation initiative) according to share of cross-border commuters per municipality across two groups: border residents vs. non-border residents.

We now turn to the results of the multivariate analysis. We first calculated a probit model without interaction (see Model 1 in Table 2) and then a second model with the interaction between border residency and the share of cross-border commuters (see Model 2). In the following, we focus on our standard model, which is the full model with the interaction term (Model 2).

As is visible from Table 2, the coefficient for border residence status proves insignificant. Hence, the voting behavior between border residents and non-border residents did not differ on average. When looking at the share of cross-border commuters per municipality, it turns out that there is no direct effect of this share on citizens’ voting behavior, neither, as the corresponding regression coefficient is insignificant. Of particular importance is the interaction term between border residence and cross-border commuters. It turns out to be positively significant at the 5% error level. This means that – as compared to non-border residents – the likelihood of citizens living at the external border of Switzerland to accept the limitation initiative augmented with an increasing share of cross-border commuters who work in their respective municipalities of residence. This result is in line with our hypothesis.

Among the socio-structural control variables, voting decisions are found to be dependent on three characteristics – age, education, and language region affiliation. As is often the case in direct-democratic votes on European integration (in Switzerland), the elders were more inclined to vote in favor of the limitation initiative than the young. In addition, the likelihood to cast a “yes vote” declined with an increasing education level. In line with patterns from recent Swiss votes on EU matters, citizens from the Italian-speaking part proved to be particularly opposed to the European integration process. Hence, they were more prone to terminate the AFMP than those of the German- and the French-speaking parts. This positive relationship between Italian-speakers and a yes vote for the limitation initiative proves to be highly significant from a statistical point of view (p < 0.001).

As far as the political control variables are concerned, we report insignificant results only for political interest. By contrast, trust in government, political ideology, party identification and the preferences along the basic value orientation “open vs. closed Switzerland” appear as strong predictors of vote choice. The more a citizen trusts the government (i.e., the Federal Council), the less likely did she or he accept the limitation initiative. Regarding political ideology, citizens were more likely to support the limitation initiative the more they placed themselves to the right of the left–right scale. This statistical association proves to be highly significant (p < 0.001). This finding suggests that the rejection of the free movement of persons clearly leans to the right in Switzerland. In line with the literature on Euroscepticism, previous research at the level of elites has nevertheless shown that parties from the Swiss radical left are almost as strongly opposed to the free movement of persons as those from the radical right (e.g., Lauener and Bernhard, 2023). A familiar finding in the Swiss context refers to party identification. Compared to the sympathizers of the Swiss People’s Party (who serve as the reference category here), the remaining major partisan groups were significantly more inclined to reject the proposition launched by the Swiss radical right. Finally, regarding the basic value orientation that served as a measure for re-bordering vs. de-bordering preferences (see Popescu, 2012), we find that stronger preferences in favor of a closed Switzerland as opposed to an open Switzerland are very closely associated with accepting the termination of the AFMP with the EU.

Over the last few decades, de-bordering policies promoted by established elites have met with fierce opposition by political forces rooted in national populism. This backlash includes economic protectionism, political isolationism, and cultural retrenchment above all in the domain of immigration. It has been most visible in important events such as the election of Donald Trump to the presidency of the United States in 2016 and Brexit, that is, the accepted referendum on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union in the same year. National populists basically maintain that globalization has ultimately benefited the governing elites at the detriment of the people, thus urging the latter for “taking back control of the nation” in order to defend their own interests. We have argued that this populist backlash has led to a profound conflict between liberal cosmopolitans and national populists that manifests itself on bordering policies with the latter demanding for re-bordering practices.

Empirically, this article has aimed to contribute to the scant scholarly literature on the relationship between populism and borders by means of an analysis of a direct-democratic vote on a re-bordering policy. We have focused on the role played by national borders as a key determinant of voters’ choices on the so-called “limitation initiative,” a proposition by the Swiss populist radical right that aimed to terminate the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons with the EU. By addressing this territorial aspect within a populist mobilization, we have tried to echo increased academic interest in the analysis of both borders and populism. Using a representative post-vote survey conducted among around 1,500 Swiss citizens, we have shown that neither border residence nor the share of cross-border commuters taken individually had an influence on people’s vote choice regarding the limitation initiative. However, taken together, there is a significant positive interaction effect between border residence and cross-border commuters. This means that – compared to non-border residents – citizens who live in a municipality bordering another country had a higher likelihood of accepting the limitation initiative when the share of cross-border commuters in their municipality was higher. This result is in line with the interaction hypothesis that we postulated in the theory section.

To some extent, this finding might appear intriguing, given that the academic literature has so far predominantly drawn a positive picture between border residence and support for the European integration process from both theoretical and empirical perspectives. A plausible explanation for this result relates to the fact that, contrary to most studies on Euroscepticism, we have focused on a specific issue by selecting the controversial free movement of persons. As opposed to general attitudes about the EU, citizens who live at the borders are likely to form their opinions on this issue based much more on their everyday personal experience rather than on their political values. In line with previous research on the free movement of persons, we have argued that our result is attributable to the fact that Switzerland is economically much more attractive than its neighboring EU member states, leading to negative externalities in the Swiss borderlands. Citizens who live in municipalities at the border with a high share of cross-border commuters are more likely to suffer from these negative externalities such as increased labor market competition, wage dumping, pressure on the housing market as well as congested roads and trains.

Given that we used data of a single direct-democratic vote held in Switzerland, our study was limited to a single country context, which calls into question the generalizability of our research. Besides the fact that we focused on a single ballot measure on the free movement of persons, it may be that the frequency at which Swiss voters are called to vote on EU-related issues has favored individual preferences above all other factors. By contrast, the formation of public opinion may be less advanced in more representative democracies. However, prominent and controversial political debates on these issues have occurred in many European countries without referendums and initiatives, which may have led to well-established positions on these matters in other European countries, too. Hence, we plead for more comparative research. At the same time, opinions within countries may also be of great use, since preferences in specific borderland contexts may vary between individuals and groups. Based on diverging economic and cultural causes, some embrace a decisive re-bordering promoted by national populists while others are fiercely opposed. Finally, scholars may take a closer look at the effects of elite communication on citizens’ opinion formation. This would require a fine-grained analysis of the discourses national populists adopt when addressing bordering issues and of their variations over time (Roch, 2024).

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://www.swissubase.ch/en/catalogue/studies/12471/13712/overview.

LB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The publication of this article was generously funded by the University of Lausanne (UNIL).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^In the context of European integration, parties from the radical left have been shown to be rather Eurosceptical as well (Rooduijn and van Kessel, 2018 for an overview). However, the critique of this party family is above all directed at the neoliberal character of EU policies (de Vries and Edwards, 2009).

2. ^The objective of this stratified sample was to include around 300 respondents for each of these language regions in order to enable separate analyses. The number of respondents amounts to 826 for the German-, 390 for the French-, and 297 for the Italian-speaking part.

3. ^For instance, Lubbers and Scheepers (2010) have found a curvilinear relation between the left–right ideological placement and Euroscepticism in many net contributor EU member states.

4. ^In the beginning of 2021, the CVP merged with the Conservative Democratic Party of Switzerland (BDP), underwent a rebranding and is now called “The Centre.”

5. ^We were not able to form a separate category for the radical left due to an insufficient number of sympathizers for Communists, Trotskyists and Alternatives, which is important insofar as scholarship has put emphasis on the (increasing) Euroscepticism on the extreme left (Lubbers and Scheepers, 2010). Yet with the exception of some cantonal contexts (such as Geneva and Neuchâtel), the radical left remains very weak in Switzerland.

6. ^Three education levels (low, middle and high) were created out of the 10 original categories. The first four categories (1 = “incomplete compulsory school/primary school,” 2 = “compulsory school,” 3 = “transitional educational program,” 4 = “general training without maturity”) were coded into “low education level,” the four following categories (5 = “elementary vocational training or apprenticeship,” 6 = “maturity or teacher training school,” 7 = “postsecondary education, non-tertiary,” 8 = “vocational high school with federal or master certificate”) were subsumed as “middle education level” and the two last categories (9 = “university of applied science, university, ETH (also university of teacher education),” 10 = “doctorate, habilitation”) as “high education level.”

Beerli, A., Ruffner, J., Siegenthaler, M., and Peri, G. (2021). The abolition of immigration restrictions and the performance of firms and workers: evidence from Switzerland. Am. Econ. Rev. 111, 976–1012. doi: 10.1257/aer.20181779

Bernhard, L. (2024). The 2023 Swiss federal elections: the radical right did it again. West Eur. Polit. 47, 1435–1445. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2024.2303277

Brubaker, L. (2020). Populism and nationalism. Nations Nationalism 26, 44–66. doi: 10.1111/nana.12522

Bürkner, H.-J. (2020). Europeanisation versus Euroscepticism: do Borders matter? Geopolitics 25, 545–566. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2020.1723964

Casaglia, A., Coletti, R., Lizotte, C., Agnew, J., Mamadouh, V., and Minca, C. (2020). Interventions on European nationalist populism and bordering in time of emergencies. Polit. Geogr. 82:102238. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102238

Cortina, J. (2020). From a distance: geographic proximity, partisanship, and public attitudes toward the U.S.–Mexico Border Wall. Polit. Res. Q. 73, 740–754. doi: 10.1177/1065912919854135

Dardanelli, P., and Mazzoleni, O. (2021). Switzerland-EU relations: Lessons for the UK after Brexit? London New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

De Vries, C. E., and Edwards, E. E. (2009). Taking Europe to its extremes: extremist parties and public Euroscepticism. Party Polit. 15, 5–28. doi: 10.1177/1354068808097889

Decoville, A., and Durand, F. (2016). Building a cross-border territorial strategy between four countries: wishful thinking? Eur. Plan. Stud. 24, 1825–1843. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1195796

Decoville, A., and Durand, F. (2019). Exploring cross-border integration in Europe: how do populations cross borders and perceive their neighbours? Eur. Urban Regional Stud. 26, 134–157. doi: 10.1177/0969776418756934

Deutsch, K. W., Burrell, S. A., Kann, R. A., Maurice, L. J., Lichterman, M., Lindgren, R. E., et al. (1957). Political community and the North Atlantic area. New York: Greenwood Press.

Díez Medrano, J. (2003). Framing Europe: Attitudes to European integration in Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

Dijkstra, L., Poelman, H., and Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2020). The geography of EU discontent. Reg. Stud. 54, 737–753. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2019.1654603

Durand, F., Decoville, A., and Knippschild, R. (2020). Everything all right at the internal EU Borders? The ambivalent effects of cross-border integration and the rise of Euroscepticism. Geopolitics 25, 587–608. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2017.1382475

Dürrschmidt, J. (2006). So near yet so far: blocked networks, global links and multiple exclusion in the German-polish borderlands. Global Netw. 6, 245–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2006.00143.x

Eatwell, R., and Goodwin, M. (2018). National populism: the revolt against liberal democracy. London: Penguin.

Ford, R. A., and Goodwin, M. J. (2014). Revolt on the right: Explaining support for the radical right in Britain. London: Routledge.

FORS/ZDA (2020). VOTO - survey on the Swiss popular vote, 27 September 2020. FORS - Centre of expertise in the social sciences, Centre for Democracy Studies Aarau (ZDA). Lausanne: University of Zurich.

Gabel, M. (1998). Interests and integration: Market liberalization, public opinion, and European Union. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Hajer, M. A. (2000). “Transnational networks as transnational policy discourse: some observations on the politics of spatial development in Europe” in The revival of strategic spatial planning. eds. W. Salet and A. Faludi (Amsterdam: Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen), 125–142.

Hobolt, S. B. (2016). The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 23, 1259–1277. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785

Jagers, J., and Walgrave, S. (2007). Populism as a political communication style: an empirical study of political parties’ discourse in Belgium. Eur J Polit Res 46, 319–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x

Kallis, A. (2018). Populism, Sovereigntism, and the unlikely re-emergence of the territorial nation-state. Fudan J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 11, 285–302. doi: 10.1007/s40647-018-0233-z

Katsambekis, G. (2022). Constructing the “people” of populism: a critique of the ideational approach from a discursive perspective. J. Polit. Ideol. 27, 53–374. doi: 10.1080/13569317.2020.1844372

Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., and Frey, T. (2008). West European politics in the age of globalization. 1st Edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kübler, D., and Kriesi, H. (2017). How globalisation and mediatisation challenge our democracies. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 23, 231–245. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12265

Kuhn, T. (2011). Individual transnationalism, globalisation and euroscepticism: an empirical test of Deutsch’s transactionalist theory: individual transnationalism, globalisation and euroscepticism. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 50, 811–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.01987.x

Kuhn, T. (2012). Europa ante Portas: border residence, transnational interaction and Euroscepticism in Germany and France. Eur. Union Polit. 13, 94–117. doi: 10.1177/1465116511418016

Lamour, C. (2020). The league of leagues: Meta-populism and the ‘chain of equivalence’ in a cross-border alpine area. Polit. Geogr. 81:102207. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102207

Lauener, L., and Bernhard, L. (2023). “What drives elite opinions on European integration?” in National populism and borders: The politicization of cross-border mobilizations in Europe. eds. O. Mazzoleni, C. Biancalana, A. Pilotti, L. Bernhard, G. Yerly, and L. Lauener (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 96–118.

Lubbers, M., and Scheepers, P. (2010). Divergent trends of euroscepticism in countries and regions of the European Union. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 49, 787–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01915.x

Lutz, P. (2021). Loved and feared: citizens’ ambivalence towards free movement in the European Union. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 28, 268–288. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2020.1720782

Mazzoleni, O. (2021). “Regionalism and Euroscepticism: the case of Ticino” in Switzerland-EU relations: Lessons for the UK after Brexit? eds. P. Dardanelli and O. Mazzoleni (Abingdon: Routledge), 148–156.

Mazzoleni, O., Biancalana, C., Pilotti, A., Bernhard, L., Yerly, G., and Lauener, L. (2023). National Populism and Borders: The politicisation of cross-border mobilisations in Europe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Mazzoleni, O., and Mueller, S. (2017). Cross-border integration through contestation? Political parties and Media in the Swiss–Italian Borderland. J. Borderl. Stud. 32, 173–192. doi: 10.1080/08865655.2016.1195698

Mazzoleni, O., and Pilotti, A. (2015). The outcry of the periphery? An analysis of Ticino’s no to immigration. Swiss Political Sci Review 21, 63–75. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12147

Mény, Y., and Surel, Y. (2000). Par le peuple, pour le peuple: le populisme et les démocraties. Paris: Fayard.

Moullé, F., and Reitel, B. (2014). “A continuously ambivalent border: building cooperation strategies in the cross-border metropolises of Basel and Geneva” in Cross-border cooperation structures in Europe: Learning from the past, looking for the future. eds. L. Dominguez and I. Pires (Brussels: Peter Lang), 193–211.

Nasr, M., and Rieger, P. (2023). Bringing geography back in: borderlands and public support for the European Union. Eur. J. Polit. Res. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12652 [Epubh ahead of print].

Olivas Osuna, J. J. (2022). Populism and Borders: tools for constructing “the people” and legitimizing exclusion. J. Borderl. Stud. 39, 203–226. doi: 10.1080/08865655.2022.2085140

Popescu, G. (2012). Bordering and ordering the twenty-first century: Understanding borders. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Roch, J. (2024). De-centring populism: an empirical analysis of the contingent nature of populist discourses. Polit. Stud. 71, 003232172210901–003232172210966. doi: 10.1177/00323217221090108

Rooduijn, M., and van Kessel, S. (2018). “Populism and Euroskepticism in the European Union” in Oxford encyclopedia of European Union politics. ed. F. Laursen (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Santana, A., and Rama, J. (2018). Electoral support for left wing populist parties in Europe: addressing the globalization cleavage. Eur. Politics Soc. 19, 558–576. doi: 10.1080/23745118.2018.1482848

Schimmelfennig, F. (2021). Rebordering Europe: external boundaries and integration in the European Union. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 28, 311–330. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2021.1881589

Schmidberger, M. (1997). Regionen und europäische Legitimität. Der Einfluss des regionalen Umfeldes auf Bevölkerungseinstellungen zur EU. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Sciarini, P. (2021). “Explaining support for European integration in direct democracy votes” in Switzerland-EU relations: Lessons for the UK after Brexit? eds. P. Dardanelli and O. Mazzoleni (Abingdon: Routledge), 104–117.

Sohn, C. (2014). Modelling cross-border integration: the role of Borders as a resource. Geopolitics 19, 587–608. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2014.913029

Sohn, C. (2020). “Borders as resources: towards a centring of the concept” in A research agenda for border studies. ed. J. W. Scott (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing).

Sohn, C., and Scott, J. W. (2020). Ghost in the Genevan borderscape! On the symbolic significance of an “invisible” border. Trans. Inst. Br. Geog. 45, 18–32. doi: 10.1111/tran.12313

Spruyt, B., Keppens, G., and Van Droogenbroeck, F. (2016). Who supports populism and what attracts people to it? Polit. Res. Q. 69, 335–346. doi: 10.1177/1065912916639138

Steger, M. B. (2019). Mapping Antiglobalist Populism: Bringing Ideology Back In. Populism 2, 110–136. doi: 10.1163/25888072-02021033

Vasilopoulou, S., and Talving, L. (2019). Opportunity or threat? Public attitudes towards EU freedom of movement. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 26, 805–823. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2018.1497075

Weyland, K. (2001). Clarifying a contested concept: populism in the study of Latin American politics, vol. 34: Comparative Politics, 1–22. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/422412.pdf

Keywords: borders, direct democracy, European Union, free movement of persons, populism, radical right, Switzerland

Citation: Bernhard L and Lauener L (2024) It’s because of the cross-border commuters: opposing the free movement of persons in the Swiss borderlands with the European Union. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1360265. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1360265

Received: 22 December 2023; Accepted: 25 July 2024;

Published: 09 August 2024.

Edited by:

Jose Javier Olivas Osuna, National University of Distance Education (UNED), SpainReviewed by:

Juan Roch Gonzalez, Fundación de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, SpainCopyright © 2024 Bernhard and Lauener. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lukas Lauener, bHVrYXMubGF1ZW5lckBmb3JzLnVuaWwuY2g=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.