- Department of Marketing, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade (IIFT), Kolkata, India

Introduction: This study aims to understand the dominant factors of political marketing strategies to influence voters in the national and state elections in India. To identify them, we have reviewed literature of different nations (both developed and developing) across the world and India.

Methods: We have defined specific criteria and search terms to first identify the relevant studies that have focused on the influencing factors in the global and Indian political marketing landscape. After identifying these factors, we gleaned the key takeaways in terms of the influencing factors from all those studies and discussed the different emerging trends of shifting power from party brand to leadership brand in the national elections. We have also analyzed the impact of different factors such as party leader or candidate's personality, party policy and ideology, use of social media as a campaigning tool, and campaign messaging and platform on the national and state elections over the years

Results and discussions: We found that for the national elections, partly leadership and use of social media are critical factors, while for the state elections, party policy and ideology with on-ground campaigns have a significant influence on voters.

1 Introduction

Political marketing has been a popular topic of study in developed nations in the West since the 1950s (Carlson and Blake, 1946; Berelson et al., 1986). Over the years, many studies have covered the different aspects of political marketing like components of voter's choice—issues and policies, social imagery, emotional feelings, candidate image, current events, personal events, and epistemic issues (Newman and Sheth, 1985); use of different traditional marketing tools and techniques by political parties and candidates (Shama, 1976; Niffenegger, 1988; Kotler and Kotler, 1999); the role of the candidate's different traits—intelligence, leadership, honesty, caring, and experience to win any particular election (Fridkin and Kenney, 2011); the importance of proper messaging during the campaign marketing (Westlye, 1991; Kahn and Kenney, 1999); and the importance of targeted marketing to increase the voter turnout in favor of the candidate or the party (Clinton and Lapinski, 2004). Till the early 2000s, most of these studies were limited to mainly the developed economies, with the US and UK elections holding the center stage of all these studies. According to Henneberg (1996, p. 777), political marketing wants to “establish, maintain and enhance long-term voter relationships at a profit for society and political parties, so that the objectives of the individual political actors and organizations involved are met.” Political marketing is a combination of politics, marketing, and campaign messaging and examines political parties and voter behavior (Scammell, 1999, p. 718). At a macro level, political marketing can be conceptualized in terms of two major aspects: political party or candidate and voters. The behavior of the voters has been studied from the perspective of consumer behavior (Newman and Sheth, 1984). In a similar way, the political party, their candidates, and party policies combined have been categorized as a political brand (Reeves et al., 2006). There are multiple factors that can affect a voter's decision to select a political party and different marketing frameworks have been used to understand and measure the brand equity of a political party or the candidate (French and Smith, 2010). These factors vary significantly in terms of different regions, cultures, economy, age, and gender and one particular campaign messaging or promotion does not decide the election results (O'Shaughnessy and Henneberg, 2009). So, political parties and candidates also started to shift their strategy from engaging in a vigorous campaign before the elections to creating a regular and continuous relationship with the voters (Grossman, 2006). Though mostly these studies deal with the concept and execution strategies of political marketing in developed nations, this article would also discuss some prominent studies in developing countries, especially in South Asian countries like India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, just to highlight the need to adapt to a different framework to understand the factors affecting voter's decisions. In recent years, social media has come to assume an important part in the field of political marketing (Harris and Harrigan, 2015; Leclercq et al., 2016). One of the best examples of the adoption of social media in political marketing can be seen in Barak Obama's political promotion in 2008 (Moufahim and Lim, 2009). In the 2008 presidential elections in the United States, Obama first introduced Web 2.0 and social media to attract the young voters (French and Smith, 2010) and this consistent and continuous social media strategy helped Obama become one of the most powerful politicians in his time (Fraser and Dutta, 2009). This kind of brand-building exercise demands both credibility of the candidate and control over the campaign messaging (Milewicz and Milewicz, 2014). Interestingly, by assuming voters as consumers by adopting a branding perspective, the engagement of such consumers through different social networks like Facebook and Twitter can work as very impactful tools to create a greater bond between the candidate and their followers (Bijmolt et al., 2010; Libai et al., 2010). In recent times, politicians and political parties all over the world are using social media to reach out to the masses (Hong and Nadler, 2012). The technology-based media, on one spectrum, are heavily used in the national elections in both developed countries like Obama, Trump (Juma'h and Alnsour, 2018; Grover et al., 2019), Boris Johnson in the UK (Suzanne, 2019) and developing countries such as that adopted by Narendra Modi in India (Kapoor and Dwivedi, 2015; Rodrigues and Niemann, 2019) and Imran Khan in Pakistan (Ashraf, 2013). On another spectrum, local or state elections still rely on “voters originated marketings on candidates—word of mouth” (Argan and Argan, 2012), character, scholastic background, political position, and social relation of the candidate (Adams and Agomor, 2015).

2 Why political marketing is important, especially in India?

India is the world's largest democracy and maintains a federal-state structure since its independence in 1947. India has a total of 28 states and eight union territories. The Election Commission of India (ECI) serves as an autonomous body, vested with the responsibility of conducting elections at all levels in the Republic of India. There are two exclusive legislative bodies at the national level: Lok Sabha (lower house of the Indian Parliament) and Rajya Sabha (upper house of the Indian Parliament). While members of the Lok Sabha are directly elected by the voters, members Rajya Sabha are elected by the elected representatives of Lok Sabha and various state assemblies. While the national politics in India are dominated by two major parties—Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Indian National Congress (INC)—since the last 30 years (Cole et al., 2012), there are hundreds of regional parties in the country (Elections.in, 2014). Out of those regional parties, Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), Communist Party of India (CPI), Communist Party of India—Marxist (CPM), the National Congress Party (NCP), All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), the Samajvadi Party (SP), and the All India Trinamool Congress (AITMC) have a very strong presence and impact in their own regions (Calì and Sen, 2011). There have been many studies in the South Asian region to understand the differences in the voter's perspective, based on geography—urban and rural areas (Chowdhury and Naheed, 2022), demography (Banerjee and Ray Chaudhuri, 2018), but there are only limited studies to understand the voter's perspective differently for national and state elections.

3 Literature search and selection

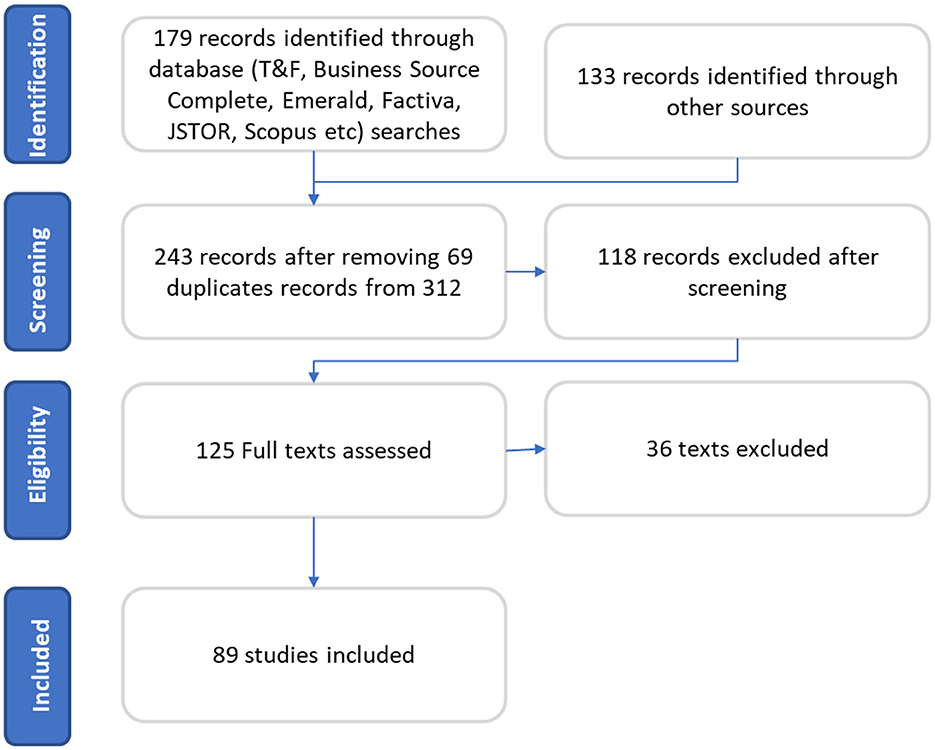

Political marketing, as a research subject, has been of interest to scholars since the 1950s. Over the years, the changing social, political, and economic landscape has given rise to different strategies of political marketing. Earlier, studies on political marketing were mainly carried out in mostly developed countries like the United States, UK, and other European countries. In the last few years, researchers have extended their horizons to developing nations like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and other African countries. However, all political marketing-related literature does not fall within the scope of our study as this study mainly focuses on the effect of different factors in the Indian political marketing landscape in the national and state elections. So, there is a need for a selected and systematic review of studies to focus on the relevant data and understand the critical factors that impact elections in India. The objective is to summarize evidence from past studies reliably and accurately. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework provides a 27-item checklist and four-phase data flow diagram to carry out this literature review systematically. This PRISMA approach is useful for authentic and reliable analysis in a systematic review. We followed the four-phase data flow diagram of PRISMA to systematically select literature at each stage (identification, screening, and eligibility) and finally ended with 89 relevant studies for this review. We reviewed all the 89 articles and gleaned key insights from them in terms of the critical factors that impact the voter's choice in the national and state elections.

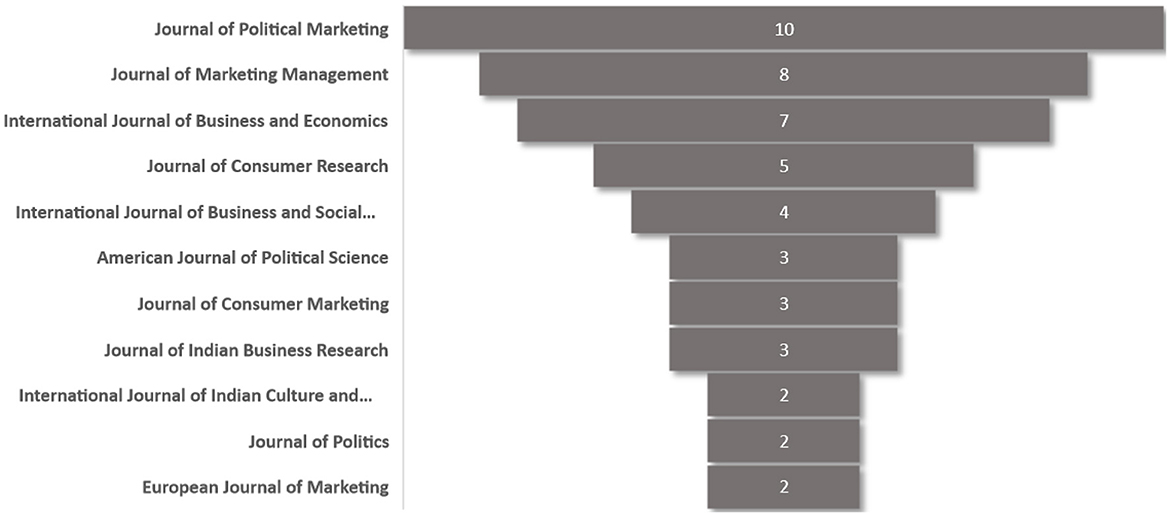

To start with, we searched keywords like “political marketing,” “party leader,” “voter behavior,” “election,” and “political party” in the following databases: Taylor & Francis, Scopus, SAGE, Google Scholar, Business Source Complete, Emerald, and ScienceDirect. We found a total 179 studies from the above search and selected an additional 133 studies from the reference list of earlier studies. In total, we located 312 studies in the identification stage following the PRISMA four-phase flow diagram. In the next screening phase, 69 duplicates were removed, and the number of studies came down to 243. The exclusion criteria were defined at the eligibility stage: (A) Not related to our study objective—the exclusion of those studies that do not focus on critical factors of political marketing (n = 76); (B) no proper study framework used—the studies that did not follow any proven framework for analysis (n = 31); and (C) no proper results demonstrated—no definitive or relevant conclusions are found from the study (n = 11). A total of 118 studies were excluded based on the above criteria. From the remaining 125 studies, we removed another 36 studies based on our inclusion criteria: (A) Published in peer-reviewed journals or in good conference related to political marketing discipline (20 articles published in non-peer-reviewed or different discipline journals were excluded); (B) mention of response bias in the primary survey method (11 articles did not mention how bias was handled in the survey questionnaire); (C) robust methodology is described to derive the conclusions (the conclusions are under-developed in five articles). Figure 1 demonstrates the entire process of PRISMA four-phase flow diagram. Based on the above inclusion criteria, finally 89 studies qualified for the review. Figure 2 shows the distribution of top-reviewed journals in these 89 studies.

4 Broad factors of political marketing

Multiple studies have argued the importance of different factors or variables that can influence a voter's decision to choose a political party or a candidate. Recent theory suggests that the voter prefers the party and the candidate who takes a firm position on issues similar to the voter's choice (Macdonald et al., 2001; Cho and Endersby, 2003). The credibility of the candidate is a very significant factor to the voters (Dumeresque, 2012) as it helps to establish a direct and emotional connect with the voters (Jain et al., 2017). The voter's decision is affected by many other influencing factors, apart from the candidates' stance, such as their preferred ideology or characteristics (Coughlin and Nitzan, 1981; Coughlin, 1992; Dow and Endersby, 2004).

Apart from the party leadership, voters are also influenced by the proposed party policy standards (ideology like left or right, social identification like caste-based politics) of the candidates or parties (Rabinowitz and Macdonald, 1989; Jessee, 2009) and whether their material self-interest is in line with the proposed policy standards or not (Sears et al., 1980; Sears and Funk, 1991). Humans are not cognitively able to consider all of the possible factors in a typical campaign and election simultaneously (Simon, 1979; Redlawsk and Lau, 2013) and therefore opinion about the past performance of any party can be significantly influential to form the voter's choice, especially when the ruling party seeks a re-election (Fiorina, 1981). The social context also plays an important role in a voter's decision regarding the political party and the candidate (Verba and Nie, 1972; Eliasoph, 1998). Social discrimination and standard influence voters to have relevant discussions in their own circles, which helps to increase their involvement with politics (Walsh, 2004). Gibson and Römmele (2009) found that telemarketing, opinion survey of voters, direct mail, Internet, more party offices, and research about opposition political party and candidates as influential indicators in Germany. Wring (1997) study indicated that survey, party policies and their fulfilments, election manifestos, direct mail, and public marketing with grassroot voters as some of the key influencing factors for voters.

In the context of South Asian countries, especially India, 2014 had been a landmark year when the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Narendra Modi, came to power after 10-year rule of the Indian National Congress (from 2004 to 2014). India is the world's largest democratic country, not just because it is the world's second most populous country but also because of the mammoth electoral process and the high level of voter engagement in all aspects of the elections (Tekwani and Shetty, 2007). The Lok Sabha elections, held once in 5 years, are the biggest voting exercise in India and in the world. Prabhu (2014), in his book Taking Pride in Public Relations, that “He [Shri Narendra Modi] won a historic election but public relations won as well.” For Lok Sabha elections in 2014, the entire concept of election campaigning and political marketing went through a complete change, a never-seen affair in the Indian election scenario. Almost all national and regional political parties micro-targeted various segments of voters by using the latest tools and technology by sending personalized messages through mobile phones and social media (Pathak and Patra, 2015). The National Democratic Alliance (NDA) (alliance of BJP and a few more parties) wanted to design their campaign messaging as a pro-development party and hence shared the Vision 2020 document (Deshpande and Iyer, 2004) based on the issue of abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu Kashmir, building Ram Mandir in Ayodhya, and enforcing a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) (Kumar, 2014). Malik and Singh (1992) mention the aggressive campaigning strategies adopted by Narendra Modi (like addressing 185 Bharat Vijay rallies across 295 constituencies of the country, creating “chai pe charcha” (“discussion at tea stall”) campaign to discuss the previous government's failure in commodity inflation and bad governance, reaching out to youth through social media with “Ab ki bar Modi Sarkar” (“Next time Modi Government”) slogan) as one of the many reasons for his victory. Social media helps to have transparent marketing between the candidates and their voters; one of the major issues revolving around effective reach and engagement is the wide social gap existing between the political candidates and the voters (Bligh and Kohles, 2009). With Narendra Modi's aggressive use of social media (like creating separate social media cell of BJP to run the digital campaign, frequent messages/tweets from his personal Facebook and Twitter handles, propagating one common slogan “Ab ki bar Modi Sarkar” (“Next time Modi Government”) from all party handles and party) in his prime ministerial campaign, and consequent historical win across the country, the impact of using of social media to reach voters has emerged as an important aspect of study.

Similarly, Gadekar (2011) studied the voter perception of Gujarat and Maharashtra, but the scope of the study was not the state elections of Gujarat and Maharashtra. The study focused only on the national elections. Along similar lines, Banerjee and Ray Chaudhuri (2018) studied the impact of demographic factors in a voter's decision in the Indian national elections. But they have also taken a particular state (West Bengal) population as the scope of their study and did not highlight whether there are any differences in the influencing factors while voting for state or national elections.

According to Aquirre and Hyman (2015) study, in terms of political advertisement or campaigning, TV or radio commercials, campaign messaging, language of the message, and key slogans of the campaign are a few more influencing indicators. Newman (1994) mentioned a few variables in his study such as the candidate's brand image to his voters, candidate's positioning and stance, extensive campaign in all spheres of society, and economic conditions of the candidate. McDonnell and Taylor (2014) argued that social and economic scenarios play a crucial role in politics and it should be taken into consideration while designing campaign marketing. Scammell (2007), in his study, reiterated the influence of a few indicators such as the candidate's leadership ability, performance of his/her party, key messaging/slogan of the campaign, party policies, and acceptance at all levels of the society. Ustaahmetoglu (2014) mentioned campaigning through mass media and door-to-door, use of celebrity figures, and massive postering as campaign strategies in their study. Deželan and Maksuti (2012) emphasized more on the influences of election posters and pointed out some key attributes of posters like colors, fonts, messages, photos, and the effect of the local language. Fishwick et al. (2014) emphasized the importance of marketing and messaging during campaign as the key influencer of the voter's decision.

Based on the above studies, party leadership and party policies are two most critical factors to influence voters, irrespective of type (national or state-level elections), geography (United States, UK, or Asia), and era (past or present). The dimensions of the campaign platform (TV, radio, Internet, newspaper, word of mouth, election rally, etc.), and content (target audience, key slogan etc.) also play a significant role. The prominence of different platforms and type of content differ with type, geography, and era. There is an ~35% increase of social media users from 2018 to 2022 (Basuroy, 2018) and party leadership's heavy use of social media to increase direct connect has made social media another important factor of political marketing. Also, especially in India, a party's affinity toward a particular caste or religion also becomes an important factor. Therefore, this study would further delve to find out effect of these five factors in detail in national and state elections of India.

5 Effect of party leader or candidate's personality

The party candidate' credibility is one of the most (Speed et al., 2015) important factors to decide the different campaigning strategies. The candidate becomes the primary marketing symbol with the voters and his/her attitude and utterings influence the voters significantly. Apart from the predetermined party policy and campaign messaging, the political candidate has to manage some nuanced interactive elements to increase his/her trustworthiness (Scammell, 2015). The hedonic dimensions help to gradually develop the emotion, trust, and loyalty (Needham, 2006) between the political candidates and the voters. In the current context, to build this long-term loyalty, political candidates need to set up a direct emotional connect with the voters. Political candidates try to uplift their personality (Jain et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2018) as more honest and modest than the opposition candidates to increase their credibility (Milewicz and Milewicz, 2014). The credibility of the political candidate is a very significant factor for the voters to decide (Dumeresque, 2012) and it helps to establish the direct and emotional connect with the voters (Jain et al., 2017). In the Indian context, BJP has won two Lok Sabha elections, in 2014 and 2019, with an absolute majority and established the “fourth party system” (Chhibber and Verma, 2019). However, some studies (Pathak, 2014; Jain and Ganesh, 2020) credited these landslide wins more to the party leader Narendra Modi and not the party (ideology or policy). To demystify the above argument, a few studies delinked the Lok Sabha and state elections to determine the greater influence among voters and between party and party leaders (Jaffrelot and Verniers, 2020). After a convincing win in the Uttar Pradesh (UP) state election in 2017, BJP's winning streak stopped and they lost almost 10 (till 2021) elections that took place in major states to regional parties (for example, Aam Admi Party (AAP) and AITMC) and the Indian National Congress (INC). Ideally, there remains a spill over effect between national and state elections (Nellis, 2014), but in this case, the situation is different. Since the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP has lost five state elections—Maharashtra, Jharkhand, Delhi, West Bengal, and Punjab. More pertinently, the difference in vote share of the BJP party between recent state elections and the 2019 Lok Sabha elections is ~20% (Election Commission of India, 2021), which is significantly high. In the state elections, party brands are largely characterized by valence politics on social or caste-based issues and by identity politics on religious issues (Adhikari et al., 2022). For example, in states like Uttar Pradesh or Bihar, there are state-level parties like Samajwadi Party or Rashtriya Janata Dal, which represent one or two specific castes. Similar parties (AIADMK and DMK) with caste identity also exist in the southern part of the country. Even in state or in lower-level elections, candidates are also chosen based on their caste or religious identity, and not individual characteristics (Singh, 2023). This makes it evident that voters are influenced by different factors in state elections and the Lok Sabha election. While in 2019 Lok Sabha election, party leader (Narendra Modi) is the branding element (Jain and Ganesh, 2020), the BJP party (ideology and policies) along with party leadership are the primary branding elements in the state elections (Jaffrelot and Verniers, 2020). In the recent Lok Sabha elections (2014 and 2019), though party ideologies hold a sway among different parties, BJP (and other alliance parties of NDA) is more dependent on the party leader (Narendra Modi) than party policy (Jain and Ganesh, 2020). In a democracy like India, traditionally political parties have been the main focal point of political branding than its leaders (Pathak and Patra, 2015). However, in the last two Lok Sabha elections (2014 and 2019), this situation has completely changed. According to Jain and Ganesh (2020), in both the elections, Narendra Modi has used seven approaches to create his personal leadership brand. Firstly, he projected himself an action-oriented leader with “#acchedin” or “good days” story. Secondly, he positioned himself as a global leader with good governance and economic growth model. Thirdly, he tried to synonymize himself with aspirations of the youth to connect with them. Fourthly, he used multiple digital initiatives to engage voters virtually. Fifthly, he opened a direct communication channel with voters through social media like Twitter and Facebook. Sixthly, Modi tried to deliver his speech in multiple languages, with the speak local, think global initiative. Finally, he created some high-energy slogans to amplify his brand energy. On the contrary, the Congress party, on one hand, tried to engage with the voters emphasizing on the party's 100-year legacy, but, on the other hand, the party tried to project Rahul Gandhi as a youth leader with global aspirations. Thus, the Narendra Modi brand has succeeded in both the elections as the BJP focused on the leader brand but the main rival, the Indian National Congress, tried to strike a balance between the party brand and the leader brand (Jain and Ganesh, 2020).

6 Effect of party policy or party legacy

After the Indian National Congress won a single-party majority in 1984 (with Rajiv Gandhi as the prime ministerial candidate), BJP become the second party to win the 2014 Lok Sabha election (Jaffrelot and Verniers, 2020) with a single-party majority. After a landslide victory for the BJP in 2019, Vaishnav and Jamie (2019) mentioned this phenomenon as the arrival of a fourth party system in India, following the earlier three-party systems of India since independence (Yadav, 1999). According to Yadav (1999), the first Indian party system was from independence to 1967 when the Congress dominated the elections both at the national and state levels. At that time, Congress was the only party of national significance and it not only dominated the national elections but also many state elections. Jawaharlal Nehru was the prime minister or strongest national-level political leader of the Congress at that time because of his nationwide influence, which was not limited to one or two states. However, there was no study to understand the influence of the Congress party or Jawaharlal Nehru separately on voter's minds. In the second phase, the Congress party mostly dominated from 1967 to 1989 with two major leaders—Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi. But at the state level, many regional parties started dominating with some state-level leaders overshadowing the dominance of the parties (Yadav, 1999). The third phase of the party system (ranging from 1990 to 2014) saw a decline in the influence of both leadership and party level in the national arena, but increased power and influence by state-level leaders. That resulted in multiple coalition governments where state parties supported national parties like the BJP and Congress to run the government at the national level (Yadav, 1999). In these three phases of the party system, parties have varied ideological influence, with first phase having maximum dominance of party ideology in the national and state-level elections. Though the second and third phases saw the rise of strong leaders nationally (for example, Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi, and Atal Bihari Vajpayee) and at state levels, very few studies have attempted to understand the influence of the attributes of parties or leaders separately. From 2014 to the current date, one party (Chhibber and Verma, 2019) and one leader (Jain and Ganesh, 2020) have dominated the Indian electoral system in the Lok Sabha election. According to Chhibber and Verma (2019), the 2019 Lok Sabha election established the rise of the second dominant party system of India, namely, the BJP, after Congress party remained the first dominant party system from independence to 1967. Chhibber and Verma (2019) mentioned this as an ideological shift of the Indian voters. On the other hand, Jain and Ganesh (2020) discussed the impact or credibility of a party leader's brand image with the example of Narendra Modi in both 2014 and 2019 Lok Sabha elections. According to their study, Narendra Modi has mostly used social media to directly connect with his followers and that helped him to build a credible, authentic yet personal political brand image, which overshadowed the party brand image. While in 2019 Lok Sabha election, party leader (Narendra Modi) is the branding element (Jain and Ganesh, 2020), in the state elections, BJP party itself (ideology and policies) along with party leadership are the primary branding elements (Jaffrelot and Verniers, 2020). It seems that, at the national level, party leader is the broad factor influencing the Indian voters more than the party itself. At the state level, party (ideology and policy) is the broad factor and National Election Studies (NES) data of 2014 and 2019 substantiate this observation. On the contrary, in the 1990s, when the BJP first became a political brand of national significance, party ideology was the primary driver to influence voter decisions (Malik and Singh, 1992). Although the BJP had formed the government twice in the 1990s, they were coalition governments with the support of other regional parties. In that era, contest was more between party brands (and not between leaders) where BJP's Hinduism and conservatism was pitted against Congress' liberal and tolerant mindset (Graham, 1990). Stereotypes and prejudice about the policy of any political party can unconsciously affect voter's decisions (Crawford et al., 2011; Lodge and Taber, 2013). Social or caste-based identifications with a political party and its policy can affect the voter's decision (Campbell et al., 1960).

7 Effect of social media

In recent times, politicians and political parties all over the world are using social media to reach out to the masses (Hong and Nadler, 2012). As the current generation uses social media (Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram) heavily, the political candidates also use these platforms (Jain et al., 2017) to increase their visibility. The 2004 Lok Sabha election in India first saw the major use of new media by both national parties: BJP and the Indian National Congress. Tekwani and Shetty (2007) noted that “with this election, the big difference was to be the technological one. After all, this was the major election in the new-technology India, the India of booming economic growth and a rising educated middle class.” There was very little opportunity to engage with voters through print media and TV. On the contrary, Internet was a cost-effective medium (Hara and Jo, 2007) and it provided an unlimited opportunity to reach out to the voters directly. In 2009, major candidates from both the parties showed inclination to the idea of using the Internet as a platform for political campaigning (Advani, 2009). But the 2014 elections changed the game completely. Not only in terms of margin and volume, this national election also saw some path-breaking strategies in terms of political marketing like focusing more on social media or digital campaign than on-ground campaign, keeping main slogan of the campaign in the name of party leader and not the party, targeting different age groups of voters with different campaign content, and engaging with the Indian diaspora of foreign countries. Almost all the national and regional political parties micro-targeted various segments of voters by using the latest tools and technology by sending personalized messages through mobile phones and social media (Pathak and Patra, 2015). India holds one of the biggest elections in the world, which includes numerous candidates and political parties seeking votes from approximately a billion citizens. Interestingly, 15 million voters in the age bracket of 18–19 years had voted for the first time in the 2019 Lok Sabha election and this age group is assumed to be more technologically equipped than other age groups. The above statistics prove that applying different tools and techniques across all the 542 parliamentary constituencies, by any political party, is a complex phenomenon and hence social media was used extensively (Hall, 2019) by all the parties to disseminate uniform campaign messaging. During the same period, Internet and social media had penetrated the Indian population significantly. In 2018, only 19.93% of the total population used social media channels. That number increased significantly to 53.71% in 2022 (Basuroy, 2018) (https://www.statista.com/statistics/240960/share-of-indian-population-using-social-networks/). Multiple studies (Kapoor and Dwivedi, 2015; Jain et al., 2017; Hall, 2019) pointed out that political parties used social media to influence a voter's decision regarding their preferred political brand. However, according to Sen (2016), the tremendous rise of BJP as the preferred national party after 2014 can be attributed to either Narendra Modi's own social media campaign or BJP party's social media campaign around Narendra Modi with slogan like “Ab ki bar Modi Sarkar.” Social media-based approach helped Narendra Modi to escalate from a regional branding (Gujarat Chief Minister) to a national-level branding as Prime Minister (Jungherr, 2016). Narendra Modi's live conversations through social media networks also influenced the young and tech-savvy voters significantly (Ghatak and Roy, 2014). Even in the 2019 Lok Sabha election, this trend continued and Narendra Modi's social media campaigns had a significant effect on the election outcome (Jain and Ganesh, 2020). Chhibber and Verma (2019) mentioned this as an ideological shift of the Indian voters, who primarily supported party identity and policy but shifted to the loyal voter base of a party leader, based on his digital and social media campaigns.

8 Effect of campaign messaging and platform

Apart from political candidate and party policy, effective campaign messaging holds a significant influence on the voter decision. As we do not have enough India-based studies to understand the effect of campaign platform on voter behavior in national and state elections, we have relied on studies in other developed and developing nations to review the effect of this factor. According to Aquirre and Hyman (2015), in terms of political advertisement or campaigning, TV or radio commercials, campaign messaging, language of the message, and key slogans of the campaign are a few more influencing indicators (Aquirre and Hyman, 2015). While campaigning, candidates cannot control two sources of information flow: one is the news media (TV, radio, print) and the opposition party campaign. The news media share a steady flow of information about all the candidates. Apart from that, a continuous and informative campaign by the opposition party also creates some image of the candidate's personality on the voters' mind. The opposition campaign is mostly negative and talks about the candidate's personal traits (Geer, 2008). While candidates often try to highlight his/her positive personality traits among the voters, the opposition tries to highlight the candidates' negative personality traits. News media is mostly factual or slightly biased and their information consists of both positive and negative traits (Fridkin and Kenney, 2011). However, information about the candidate's negative traits becomes more significant than his/her positive traits (Fiske, 1980). In the current era, platform for campaign messaging can be classified into two broad areas: proactive campaigning by the candidate through different platforms like Internet, TV, or live debate and word of mouth among the voters. Though Internet is gaining popularity, the importance of word-of-mouth marketing cannot be ignored to provide a continuous flow of information through personal experience. The importance of word-of-mouth marketing also lies in the fact that political marketers have very low credibility and reliability among all marketers (Adams et al., 2011). Also, a very small percentage of voters trust the political campaign messages (messages conveyed through other platforms like Facebook, Twitter, or TV as paid promotion and marketing effort) that are advocated (Hopkins, 2013). In this kind of scenario, word-of-mouth campaign messages, passing through a credible group of voters, can be more reliable and credible than other methods, and this method has the ability to change voters' mind to take a decision on any political party (Iyer et al., 2017). Wring (1997) study indicated that party policies and their fulfilments, election manifesto, direct mail, and public marketing with grassroots voters are some of the key influencing factors on voters. The above studies discussed multiple factors of the campaign platform affecting voter perception, but none of them gave an insight into the differential impact on the national and state elections.

9 Effect of caste and religion

Caste system has been dominant in the Indian political system since independence and many state-level parties have been formed with primary ideology of casteism (Singh and Saxena, 2003). Even within one religion, there were many social groups (with different caste) that prefer political parties solely on the party's inclination to a certain social group or groups (Suri, 2019). Due to a notable rise in educational opportunities and the implementation of caste-based reservations, the representation of Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) in government employment has significantly improved since independence. In the 1980s, the Mandal Commission highlighted the disadvantaged position of backward castes in education and government jobs, who were lagging behind SCs and STs. The introduction of reservations for backward castes has led to considerable progress since 1990. For instance, in 1959, SC representation was 1.18% in Class I, 2.38% in Class II, 6.95% in Class III, and 17.24% in Class IV positions, which increased to 13.38% in Class I positions by 2016. The representation of SCs and STs across all government services was 13.17% and 2.25%, respectively, in 1965, rising to 17.49% and 8.49%, respectively, in 2016, approximately aligning with their proportion of population. Despite this progress, Backward Castes (BCs), constituting about 20% of the population, still have a long path to cover in terms of representation in government positions (GoI, 2018, p. 49). For the same reason, the rise of backward castes like SC, ST, and OBC in the Indian political system is an important phenomenon (Yadav, 1999) and their increased involvement in the political landscape has been termed as a silent revolution (Jaffrelot, 2003), which had a significant impact in the state elections, if not in the national elections. However, BJP's political agenda was to divert the direction from caste-based state-level politics to religion-based national-level politics (Graham, 1990). In the last two decades, the BJP has increased its support base in various Hindu social groups of different castes (Suri, 2019). Though the BJP has registered a significant increase in vote share since 2014 in the state elections among the middle-level support states of the Hindi belt such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Haryana due to its Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) politics, its increased popularity in other state elections and national election are due to party's campaign content and party leader's (Narendra Modi) influence (Schakel et al., 2019). The above studies indicate that though caste and religion still play an important role among the lower strata of the society in the state elections, in the national election, party leader's (Narendra Modi) influence with targeted social media strategy plays an equal, if not more important, role to affect voter's opinion.

10 Discussion and findings

All the above studies discussed different factors affecting voter behavior in the national and state elections. Party and leadership are the most important elements of political branding (Needham, 2006), and it is difficult to quantify the effect of each of these elements. In this study, we adopted a systematic literature review method to study literature of different nations and India to find out the major driving force of voter behavior in respect to national and state elections. With respect to India, we have reviewed studies to understand the effect of four broad factors: (i) party leadership or candidate, (ii) party policy or legacy, (iii) use of social media, and (iv) campaign messaging and platform. Though traditionally India has witnessed party-based politics since independence, the trend has shifted to party leader-based politics (Chhibber and Verma, 2019) in the last 10 years in the national elections. If we analyse the journey of the Indian political landscape and the factors that affect its transition, we can say that for the initial 25 years, it was majorly dominated by one party brand in both national and state elections (Yadav, 1999). After that, with the emergence of state-level leaders, the control has shifted to the state-level party and their policies, which influenced both the national and state elections (Yadav, 1999). During this phase, even in the national election, mostly coalition governments (with multiple state-level parties) were formed and the major campaign platforms were door-to-door to campaign, on-ground campaign, and on-stage campaign, and the major voter-influencing factor was party-based policy and ideology (Malik and Singh, 1992). With the advent of social media, Narendra Modi began to dominate the national-level election since 2014 (Jain and Ganesh, 2020). While in the 2019 Lok Sabha election, party leader (Narendra Modi) is the major factor (Jain and Ganesh, 2020), in the state elections, the BJP party itself (ideology and policies), along with party leadership, are the primary factors (Jaffrelot and Verniers, 2020) to influence voters. It seems that, at the national level, party leader is the broad factor influencing the Indian voters more than the party itself. At the state level, party (ideology and policy) is the broad factor and NES. (2014, 2019) data substantiate this observation. On the contrary, in the 1990s, when the BJP first became a major political brand of national significance, party ideology was the primary driver to influence voter decisions (Malik and Singh, 1992). So, we can conclude that in the national elections, party leaders have become the dominant factor of any political brand in the last 15 years due to advent of new-age media like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. However, in the state elections, party policies still dominate and the preferred campaign platform is on-ground campaigning and word-of-mouth publicity. So, political marketers should consider this information while designing campaign strategies for the national and state elections. This study would also add value to theory of political marketing as there are very limited studies with a systematic literature review process and our study would be an example of how to use PRISMA's four-phase data flow framework.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. GD: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams, J., Ezrow, L., and Topcu, Z. (2011). Is anybody listening? Evidence that voters do not respond to European parties' policy statements during elections. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 55, 370–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00489.x

Adams, S., and Agomor, K. (2015). Democratic politics and voting behaviour. Int. Area Stu. Rev. 18:10.1177/2233865915587865 doi: 10.1177/2233865915587865

Adhikari, P., Mariam, S., and Thomson, R. (2022). Election pledges in India: comparisons with Western democracies. Commonwealth Compar. Polit. 60, 254–275. doi: 10.1080/14662043.2022.2087356

Advani, L. K. (2009). Electioneering: From Handbill to the Internet. The Post on His Blog. Available online at: http://blogs.siliconindia.com/LKAdvani/Electioneering_From_Handbill_to_the_Internet-bid-2436GwI910882.html (accessed April 8, 2009).

Aquirre, G. C., and Hyman, M. R. (2015). The marketing mix and the political marketplace. Bus. Outlook 13, 1–5.

Argan, M., and Argan, M. T. (2012). Word-of-mouth (wom): voters originated marketings on candidates during local elections. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 3, 70–77.

Ashraf, A. (2013). Impact of new media on dynamics of Pakistan politics. J. Polit. Stu. 20, 113–130.

Banerjee, S., and Ray Chaudhuri, B. (2018). Influence of voter demographics and newspaper in shaping political party choice in India: an empirical investigation. J. Polit. Market. 17, 90117. doi: 10.1080/15377857.2016.1147513

Basuroy, T. (2018). Social network penetration India 2018-2028, Statista. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/240960/share-of-indian-population-using-social-networks/

Berelson, B. R., Lazarsfeld, P. F., and McPhee, W. N. (1986). Voting: A Study of Opinion Formation in a Presidential Campaign. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bijmolt, T. H. A., Leeflang, P. S. H., Block, F., Eisenbeiss, M., Hardie, B. G. S., Lemmens, A., and Saffert, P. (2010). Analytics for customer engagement. J. Serv. Res. 13, 341–356. doi: 10.1177/1094670510375603

Bligh, M. C., and Kohles, J. C. (2009). The enduring allure of charisma: how Barack Obama won the historic 2008 presidential election. The Leadership Q. 20, 483–492. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.03.013

Calì, M., and Sen, K. (2011). Do effective state business relations matter for economic growth? Evidence from Indian states. World Dev. 39, 1542–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.02.004

Campbell, A., Philip, C., Warren, M., and Donald, S. (1960). The American Voter. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Carlson, O., and Blake, A. (1946). How to Get into Politics. New York, NY: Duell, Sloan and Pearce; Cambridge University Press, 210.

Chhibber, P., and Verma, R. (2019). The rise of the second dominant party system in India: BJP's new social coalition in 2019. Stu. Indian Polit. 7, 131–148. doi: 10.1177/2321023019874628

Cho, S., and Endersby, J. W. (2003). Issues, the spatial theory of voting, and British general elections: a comparison of proximity and directional models. Public Choice 114, 275–293. doi: 10.1023/A:1022616323373

Chowdhury, T. A., and Naheed, S. (2022). Multidimensional political marketing mix model for developing countries: an empirical investigation. J. Polit. Market. 21, 56–84. doi: 10.1080/15377857.2019.1577323

Clinton, J. D., and Lapinski, J. S. (2004). Targeted advertising and voter turnout: an experimental study of the 2000 presidential election. The J. Polit. 66, 69–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2508.2004.00142.x

Cole, S., Healy, A., and Werker, E. (2012). Do voters demand responsive governments? Evidence from Indian disaster relief. J. Dev. Econ. 97, 167–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.05.005

Coughlin, P., and Nitzan, S. (1981). Electoral outcomes with probabilistic voting and Nash social welfare maxima. J. Pub. Econ. 15, 113–121. doi: 10.1016/0047-2727(81)90056-6

Crawford, J. T., Jussim, L., Madon, S., Cain, T. R., and Stevens, S. T. (2011). The use of stereotypes and individuating information in political person perception. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 37, 529–542. doi: 10.1177/0146167211399473

Deshpande, R., and Iyer, L. (2004). Elections 2004: BJP rides on India Shining plank, Cong counters feel-good line. India Today. Available online at: https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/cover-story/story/20040322-game-plan-of-congress-bjp-in-elections-2004-790276-2004-03-21

Deželan, T., and Maksuti, A. (2012). Slovenian election posters as a medium of political communication: an informative or persuasive campaign tool?. Commun. Polit. Cult. 45, 140–159.

Dow, J. K., and Endersby, J. W. (2004). ‘Multinomial probit and multinomial logit: a comparison of choice models for voting research. Elector. Stud. 23, 107–22. doi: 10.1016/S0261-3794(03)00040-4

Dumeresque, D. (2012). Equality, inequalities and diversity: contemporary challenges and strategies. Strat. Dir. 28:05628iaa.003. doi: 10.1108/sd.2012.05628gaa.003

Election Commission of India (2021). List of Political Parties & Symbol MAIN Notification. Available online at: https://eci.gov.in/files/file/13711-list-of-political-parties-symbol-main-notification-dated23092021/

Eliasoph, N. (1998). Avoiding Politics: How Americans Produce Apathy in Everyday Life. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Fiorina, M. P. (1981). Retrospective Voting in American National Elections. New Haven, CT:Yale University Press.

Fishwick, C., Walsh, J., and Howard, E. (2014). Indian Elections: 10 Things We Have Learned So Far. The Guardian. Available online at: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/apr/11/10-things-we-learned-about-indian-election-modi-marriages (accessed April 11, 2014).

Fiske, S. T. (1980). Attention and weight in person perception: the impact of negative and extreme behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 38:889. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.38.6.889

Fraser, M., and Dutta, S. (2009). How Social Media Helped Barack Obama to Become the Most Powerful Man. Available online at: http://newsblaze.com/story/20090128105841zzzz.nb/topstory.html (accessed May 4, 2016).

French, A., and Smith, G. (2010). Measuring political brand equity: a consumer oriented approach. Eur. J. Market. 44, 460–477. doi: 10.1108/03090561011020534

Fridkin, K. L., and Kenney, P. J. (2011). The role of candidate traits in campaigns. The J. of Polit. 73, 61–73. doi: 10.1017/S0022381610000861

Gadekar, R. (2011). Web sites for e-electioneering in Maharashtra and Gujarat, India. Intern. Res. 21 435–457. doi: 10.1108/10662241111158317

Geer, J. G. (2008). In defense of Negativity: Attack Ads in Presidential Campaigns. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Ghatak, M., and Roy, S. (2014). Did Gujarat's growth rate accelerate under Modi?. Econ. Polit. Weekly 49, 12–15.

Gibson, R., and Römmele, A. (2009). Measuring the professionalization of political campaigning. Party Polit. 15, 265–293. doi: 10.1177/1354068809102245

GoI (2018). Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions. Annual Report, 2017–18. Available online at: https://dopt.gov.in/sites/default/files/DOPT-PG-AND-TRAINING-ANNUAL-REPORT-2017-18.pdf

Graham, B. D. (1990). Hindu Nationalism and Indian Politics: The Origins and Development of the Bharatiya Janata Party. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 55.

Grossman, V. (2006). On the ideology motive in political economy models. Int. J. Bus. Econ. 5, 75–82.

Grover, P., Kar, A. K., Dwivedi, Y. K., and Janssen, M. (2019). Polarization and acculturation in US Election 2016 outcomes–Can twitter analytics predict changes in voting preferences. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 145, 438–460. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2018.09.009

Hall, I. (2019). India's 2019 general election: national security and the rise of the watchmen. The Round Table 108, 507–519. doi: 10.1080/00358533.2019.1658360

Hara, N., and Jo, Y. (2007). Internet politics: a comparative analysis of US and South Korea presidential campaigns. First Monday 12:1. doi: 10.5210/fm.v12i9.2005

Harris, L., and Harrigan, P. (2015). Social media in politics: The ultimate voter engagement tool or simply an echo chamber? J. Polit. Market. 14, 251–283. doi: 10.1080/15377857.2012.693059

Henneberg, S. C. (1996). Conference Report: Second Conference on Political Marketing: Judge Institute of Management Studies. Cambridge: University of Cambridge.

Hong, S., and Nadler, D. (2012). Which candidates do the public discuss online in an election campaign?: the use of social media by 2012 presidential candidates and its impact on candidate salience. Gov. Inf. Q. 29, 455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2012.06.004

Hopkins, D. (2013). Political Ads: Not as Powerful as you (or Politicians) Think. Wonkblog. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/01/20/political-ads-not-as-powerful-as-you-orpoliticians-think (accessed January 20, 2013).

Iyer, P., Yazdanparast, A., and Strutton, D. (2017). Examining the effectiveness of wom/e-wom marketings across age-based cohorts: implications for political marketers. J. Consumer Market. 34, 646–663. doi: 10.1108/JCM-11-2015-1605

Jaffrelot, C. (2003). India's Silent Revolution: The Rise of the Low Castes in North Indian Politics. New Delhi: Permanent Black.

Jaffrelot, C., and Verniers, G. (2020). A new party system or a new political system? Contemp. South Asia 22, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/09584935.2020, 1765990.

Jain, V., and Ganesh, B. E. (2020). Understanding the magic of credibility for political leaders: a case of India and Narendra Modi. J. Polit. Market. 19, 15–33. doi: 10.1080/15377857.2019.1652222

Jain, V., Pich, C., Ganesh, B. E., and Armannsdottir, G. (2017). Exploring the influences of political branding: a case from the youth in India. J. Indian Bus. Res. 9, 190–211. doi: 10.1108/JIBR-12-2016-0142

Jessee, S. A. (2009). Spatial voting in the 2004 presidential election. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 103, 59–81. doi: 10.1017/S000305540909008X

Juma'h, A., and Alnsour, Y. (2018). Using social media analytics: the effect of President Trump's tweets on companies' performance. J. Acc. Manage. Inform. Syst. 17, 100–121. doi: 10.24818/jamis.2018.01005

Jungherr, A. (2016). Twitter use in election campaigns: a systematic literature review. Journal of Inf. Technol. Politics 13, 72–91. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2015.1132401

Kahn, K. F., and Kenney, P. J. (1999). Do negative campaigns mobilize or suppress turnout? Clarifying the relationship between negativity and participation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 93, 877–889. doi: 10.2307/2586118

Kapoor, K. K., and Dwivedi, Y. K. (2015). Metamorphosis of Indian electoral campaigns: Modi's social media experiment. Int. J. Indian Culture Bus. Manage. 11, 496–516. doi: 10.1504/IJICBM.2015.072430

Kim, Y., Park, I., and Kang, S. (2018). Age and gender differences in health risk perception. Cent. Eur. J. Publ. Health 26, 54–59. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a4920

Kotler, P., and Kotler, N. (1999). “Political marketing: generating effective candidates, campaigns and causes,” in Handbook of Political Marketing, ed. B. I. Newman (London: Sage), 3–18.

Kumar, R. (2014). Political communication and the electoral campaign: a case study of the 2014 national election. J. Polit. Gov. 3, 157–162.

Leclercq, T., Hammedi, W., and Poncin, I. (2016). Ten years of value cocreation: an integrative review. Recherche et Applications en Market. 31, 26–60. doi: 10.1177/2051570716650172

Libai, B., Bolton, R., Bügel, M. S., Ruyter, D., Götz, K., Risselada, O., et al. (2010). Customer-to-customer interactions: broadening the scope of word of mouth research. J. Serv. Res. 13, 267–282. doi: 10.1177/1094670510375600

Lodge, M., and Taber, C. S. (2013). The Rationalizing Voter. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Macdonald, S. E., Rabinowitz, G., and Listhaug, O. (2001). Sophistry versus science: on further efforts to rehabilitate the proximity model. J. Polit. 63, 482–500. doi: 10.1111/0022-3816.00075

Malik, Y. K., and Singh, V. B. (1992). Bharatiya Janata Party: An alternative to the Congress (I)?. Asian Survey 32, 318–336. doi: 10.2307/2645149

McDonnell, J., and Taylor, P. J. (2014). Value creation in political exchanges: a qualitative study. J. Polit. Market. 13, 213–232. doi: 10.1080/15377857.2014.929884

Milewicz, C., and Milewicz, M. (2014). The branding of candidates and parties: the U.S. news media and the legitimization of a new political term. J. Polit. Market. 13, 233–263. doi: 10.1080/15377857.2014.958364

Moufahim, M., and Lim, M. (2009). Towards a critical political marketing agenda? J. Market. Manage. 25, 763–776. doi: 10.1362/026725709X471613

Needham, C. (2006). Brands and political loyalty. J. Brand Manage. 13, 178–187. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540260

Nellis, M. (2014). Upgrading electronic monitoring, downgrading probation: reconfiguring ‘offender management' in England and Wales. Eur. J. Prob. 6, 169–191. doi: 10.1177/2066220314540572

NES. (2014). POST POLL, CSDS-LOKNITI Post-Poll Survey 2014. Available online at: https://www.lokniti.org/national-election-studies

NES. (2019). POST POLL, THE HINDU CSDS-LOKNITI Post-Poll Survey 2019. Available online at: https://www.lokniti.org/media/PDF-upload/1579771857_30685900_download_report.pdf

Newman, B. I. (1994). The Marketing of the President: Political Marketing as Campaign Strategy. London: Sage.

Newman, B. I., and Sheth, J. N. (1984). The gender gap in voter attitudes and behavior: some advertising implications. J. Advert. 13, 416.

Newman, B. I., and Sheth, J. N. (1985). A model of primary voter behavior. J. Consum. Res. 12, 178–187.

Niffenegger, P. B. (1988). Strategies for success from the political marketers. J. Serv. Market. 2, 15–21. doi: 10.1108/eb024729

O'Shaughnessy, N. J., and Henneberg, S. C. (2009). Political relationship marketing: some micro/macro thoughts. J. Market. Manage. 25, 5–29. doi: 10.1362/026725709X410016

Pathak, P. (2014). Ethopolitics and the financial citizen. Sociol. Rev. 62, 90–116. doi: 10.1111/1467-954X.12119

Pathak, S., and Patra, R. K. (2015). Evolution of political campaign in India. Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. 2, 55–59.

Rabinowitz, G., and Macdonald, S. E. (1989). A directional theory of issue voting. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 83, 93–121. doi: 10.2307/1956436

Redlawsk, D. P., and Lau, R. R. (2013). “Behavioral decision-making,” in Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, 2nd Edn. Eds. L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, and J. S. Levy (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 130–64.

Reeves, P., de Chernatony, D., and Carrigan, L. (2006). Building a political brand: ideology or voter-driven strategy. J. Brand Manage. 13, 418–428. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540283

Rodrigues, U. M., and Niemann, M. (2019). Political communication Modi style: a case study of the demonetization campaign on Twitter. Int. J. Media Cult. Polit. 15, 361–379. doi: 10.1386/macp_00006_1

Scammell, M. (1999). Political marketing: lessons for political science. Polit. Stu. 47, 718–739. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.00228

Scammell, M. (2007). Political brands and consumer citizens: the rebranding of Tony Blair. The Annal. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci., 611, 176–192. doi: 10.1177/0002716206299149

Scammell, M. (2015). Politics and image: the conceptual value of branding. J. Polit. Market. 14, 7–18. doi: 10.1080/15377857.2014.990829

Schakel, A. H., Sharma, C. K., and Swenden, W. (2019). India after the 2014 general elections: BJP dominance and the crisis of the third party system. Reg. Fed. Stu. 29, 329–354. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2019.1614921

Sears, D. O., and Funk, C. L. (1991). “the role of self-interest in social and political attitudes,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, ed. L. Berkowitz (New York, NY: Academic Press), 1–91.

Sears, D. O., Lau, R. R., Tyler, T. R., and Allen, H. M. (1980). Self-interest vs. symbolic politics in policy attitudes and presidential voting. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 74, 670–684. doi: 10.2307/1958149

Sen, R. (2016). Narendra Modi's makeover and the politics of symbolism. J. Asian Pub. Policy 9, 98–111. doi: 10.1080/1752016, 1165248.

Shama, A. (1976). The marketing of political candidates. J. Acad. of Market. Sci. 4, 764–777. doi: 10.1007/BF02729836

Simon, H. A. (1979). Information processing models of cognition. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 30, 363–396. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.30.020179.002051

Singh, M. P., and Saxena, R. (2003). India at the Polls: Parliamentary Elections in the Federal Phase. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan.

Singh, R. (2023). Candidate selection in India: municipal elections and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Commonwealth Compar. Polit. 61, 90–114. doi: 10.1080/14662043.2023.2172792

Speed, R., Butler, P., and Collins, N. (2015). Human branding in political marketing: applying contemporary branding thought to political parties and their leaders. J. Polit. Market. 14, 129–151. doi: 10.1080/15377857.2014.990833

Suri, K. (2019). Social change and the changing indian voter: consolidation of the BJP in India's 2019 Lok Sabha Election. Stu. Indian Polit. 7:232102301987491. doi: 10.1177/2321023019874913

Suzanne, M. (2019). How Social Media Echo Chambers Fuelled the Rise of Boris Johnson, The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jul/23/how-social-media-echo-chambers-fuelled-the-rise-of-boris-johnson (accessed July 23, 2019).

Tekwani, S., and Shetty, K. (2007). “Two India's – the role of the Internet in 2004 elections,” in, The Internet and National Elections: A Comparative Study of Web Campaigning, eds. R. Kluvar, N. W. Jankowski, F. A. Foot, and S. M. Schneider (New York, NY: Routledge).

Ustaahmetoglu, E. (2014). Political marketing: the relationship between agenda-setting and political participation. Innov. Market. 10, 32–39.

Vaishnav, M., and Jamie, H. (2019). India's Fourth Party System. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Verba, S., and Nie, S. H. (1972). Participation in America: Political Democracy and Social Equality. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Walsh, K. C. (2004). Talking About Politics: Informal Groups and Social Identity in American Life. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press

Westlye, M. (1991). Senate Elections and Campaign Intensity. Baltimore, MA: Johns Hopkins University Press, 265.

Wring, D. (1997). Reconciling marketing with political science: theories of political marketing. J. Market. Manage. 13, 651–663. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.1997.9964502

Keywords: election, politics, political marketing, voter behavior, literature review

Citation: Chatterjee J and Dutta G (2024) A systematic literature review to understand the difference between critical factors affecting the national election and state elections in India. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1323186. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1323186

Received: 17 October 2023; Accepted: 08 May 2024;

Published: 31 May 2024.

Edited by:

Régis Dandoy, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, EcuadorReviewed by:

Bappaditya Mukhopadhyay, Great Lakes institute of Management, Gurgaon, IndiaEdward Elder, The University of Auckland, New Zealand

Copyright © 2024 Chatterjee and Dutta. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joydeep Chatterjee, am95ZGVlcF9waGRtcDE5QGlpZnQuZWR1

Joydeep Chatterjee

Joydeep Chatterjee Gautam Dutta

Gautam Dutta