- Department of Political Science, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Changes in party systems do not always occur gradually. While structural changes in societies lead to new tensions and potential conflicts, these conflicts often become politicized in the wake of ‘triggering events’. However, such events do not always lead to the politicization of an issue. This study addresses the question why potentially triggering events sometimes produce extensive political attention and conflict around an associated issue, whereas in other circumstances very similar events do not generate much political attention or contestation. Some scholars highlight the strategic incentives of party political elites (the top-down perspective) whereas others focus on the key role of political challengers in politicizing issues (‘the bottom-up perspective)’. We focus on three events that potentially trigger the politicization of immigration (9–11, Banlieus riots and the Cartoon crisis) and identify anti-immigration parties as challengers of government parties. Based on political claims analysis of newspapers in seven European countries, we find that government parties exert strong control over the political agenda, both in terms of salience as in positional terms. However, when anti-immigration parties are large and in opposition, they do play an important role in politicizing the issue of immigration. Since anti-immigration parties have increased their vote share over the past decade and typically remain in the opposition nevertheless, it is likely that future events will lead to further politicization of the issue of immigration.

Introduction

Over the past decades the party systems of several Western European democracies have changed fundamentally, largely as the result of the increased salience of conflicts over immigration and European unification. While different authors use different terms to describe this conflict dimension,1 there seems to be consensus among scholars that the politicization of the issue of immigration (broadly defined) is a key component of these recent changes in the party systems. Both parties and citizens are increasingly divided on the question of which types of immigrants and how many can be admitted into the countries and to what extent these immigrants should (culturally) adapt to the habits and norms of majority populations. Changes to party systems often do not occur gradually. Even though there are often structural developments that lead to tensions in society, sudden unexpected crises or events may spark a process of politicization and become ‘critical junctures’ in a process of party system change (e.g., Braun and Tausendpfund, 2016; Hooghe and Marks, 2018; Hutter and Kriesi, 2020; Schäfer et al., 2020). However, while scholars agree on the fact that the issue of immigration has become increasingly politicized, there is debate about whether this is either a top-down or bottom-up driven process.

One perspective sees politicization largely as a top-down process, where mainstream parties, in particular those in government, set the political agenda (e.g., Mair, 1998, pp. 10–13; Green-Pedersen, 2010). As noted by Green-Pedersen (2010), p. 16 ‘mainstream parties, if they agree, have a strong control over the party system agenda’. To the extent that mainstream parties agree, they should thus be able not only to determine which issues are politicized, but also to de-politicize an issue that threatens existing (government) coalitions and internal party cohesion (e.g., Schattschneider, 1960, pp. 60–75). The second perspective is one in which there is an important role for challengers, such as grass root organizations and social movements (e.g., Koopmans et al., 2005), niche or challenger parties (e.g., Meguid, 2008; De Vries and Hobolt, 2020) or the public (Downs, 1972; Stimson, 2004). To be sure, most of these authors have emphasized the importance of structural conditions that may offer opportunities for such challengers, or limit these opportunities. Yet, still, in these latter perspectives, politicization of an issue is seen more as a bottom up process than in the former ones.

We contribute to this debate by studying the politicization of the issue of immigration following three events that could have potentially triggered a process of politicization (9–11, Banlieus riots and the Cartoon crisis). We study politicization by means of political claims analysis of newspapers in seven European countries. This enables us, not only to measure politicization at an aggregate level, but also to see which actors initially set the agenda and how different actors react to each other in the news. In this way, we acquire detailed information about how the issue becomes politicized (if at all) and whether this is mainly bottom up or top down.

One could reasonably argue that the leadership of all parties and even social movements is part of the elite, which would then imply that processes of politicization are always initiated top down. However, in this study we distinguish between governing parties and mainstream opposition parties on the one hand and challenger parties and social movements on the other hand. When the latter are able to politicize the issue, we will refer to this as bottom up because we consider these parties as outsiders that wish to change the status quo by politicizing an issue that mainstream actors would prefer to de-politicize. We find that government coalition parties exert strong control over the political agenda, both in terms of salience and in positional terms. However, when anti-immigration parties are large and in opposition, they do play an important role in politicizing the issue of immigration.

So, while our findings provide support for the top-down perspective, they also suggest ways to bridge the two perspectives. More specifically, we point out that government agenda control is asymmetric: government parties can push issues on the agenda but are less successful in strategically keeping unfavorable issues off the agenda. In our cases this asymmetry appears when there is a large far right party in the opposition, and can get the issue of immigration on the agenda, even when it would be better for mainstream parties to ignore it. Mainstream parties then feel forced to react. Our attention to the context-specific strategic interaction between mainstream and challenger parties bridges the two perspectives. We contribute to the literature by proposing a ‘strategic interaction’ perspective on politicization.

The results also speak more broadly to the theme of the special issue. We can expect that the issue of immigration will remain high on the political agenda, since most western democracies have a large anti-immigration party that benefits electorally from politicizing the issue. Mainstream parties will not be able to keep the issue from getting high onto the agenda at different occasions. So, this highly divisive issue will likely remain to be prominent.

Our paper is structured as follows. We will first elaborate on our conceptualization of politicization and discuss how our study relates to the wider literature. We then discuss the data and our methods of analyses, after which we will present the results. The concluding section discusses the implications of our findings.

What do we mean by politicization?

Two bodies of literature exist which focus on ways in which issues become politicized or not. The first tradition of research is concerned with agenda setting. Under which circumstances does a social problem become defined as a problem that requires action from public officials? Agenda setting theory focuses on the different thresholds of public saliency that prevent a topic from becoming an issue and/or prevent an issue from reaching the stage where policies are formulated. A second body of literature focuses more on competition in terms of the intensity of conflict, polarization and position-taking. The abovementioned top-down and bottom-up perspectives are to be found in both traditions. We will discuss both strands of agenda-setting literature in turn.

Agenda-setting studies in political science point to the relative attention, the salience, of issues in various arenas of politics (e.g., Downs, 1972; Cobb and Elder, 1983; Jones and Baumgartner, 2005; Baumgartner et al., 2009). In an overly simplified bottom up view of such agenda-setting approaches, issue attention travels from public opinion via the news media through party politics to the government and its policies. The focus is on the variation in government responsiveness to political issues. In this perspective, the rank-order of issues, the restricted nature of agendas and the (un)likely pathways of issue salience are important factors to explain differences in politicization. Agenda setting studies have extensively assessed the effect of so-called focusing events, ‘external shocks’ or ‘alarmed discoveries’ on policy attention and change (Downs, 1972; Kingdon, 1984, pp. 99–105; Baumgartner and Jones, 1993; p. 39; Birkland, 1997, 2004; Walgrave and Varone, 2008, p. 368). With their focus on (relative) issue salience, agenda-setting studies, however, still miss the magnitude and character of the conflict, because they do not take into account the extent to which actors disagree. Many debates may deal with technicalities of new legislation or policy implementation, rather than with fundamental differences of opinion.

Second, especially scholars of political parties, and party competition more specifically, highlight the importance of positional competition and the extent to which political parties (and the electorate) have different, polarized positions on the issue (e.g., Downs, 1957; Carmines and Carmines, 1989; Hobolt and De Vries, 2015). Electoral competition is seen as a process in which parties present different choices to the electorate in terms of different positions on issues and opposing ideological positions. In this view, the political positions of actors and their interrelationships in a political space determine what political actors do in parliament, in government, in election campaigns and in other forms of providing political attention to issues.

The academic interest in the politicization of issues arises from the idea that the expansion of the scope of participation potentially contributes to more democratic policy-making processes (e.g., Baumgartner and Jones, 1993, p. 11). In this line of argumentation one should observe that electoral campaigns on issues that citizens care about and where political parties present meaningfully opposing views will have larger turn-out and create a stronger mandate than relatively ‘depoliticized’ electoral campaigns in which party offerings are proximate to one another and on issues of limited public salience. At the same time, as noted by Schattschneider (1960), p. 64 politicization may also overburden the political system with contradictory demands and polarized positions may create policy deadlock.

In addition to salience and polarization, recent studies on politicization identify the numbers and types of actors involved in a conflict, i.e., its scope (or ‘actor expansion’ or ‘resonance’), as an important dimension of the politicization issues (De Wilde, 2011; De Wilde and Zürn, 2012; Grande and Hutter, 2016, pp. 7–10; Grande and Hutter, 2016; Hutter and Kriesi, 2020).2 In line with recent work by Andrione-Moylan et al. (2023) we conceptualize politicization as an actor-driven phenomenon. So, we do not consider actor dynamics to be a dimension of politicization. Instead, we conceive of issue (de-)politicization as a (potential) consequence of the strategic interactions of political actors. In our study we will thus focus on two dimensions of politicization: salience and (positional) polarization. This means that in issue becomes more politicized when it is higher on the political agenda (more salient) and when the positions of different actors drift apart (more polarized). Even though the two dimensions of politicization are probably not independent, we treat them as two separate dependent variables in our models.

Our theoretical perspective on politicization is based on three assumptions. The first assumption is that there are many potential conflicts in each society and that only some will be (temporarily) politicized (Schattschneider, 1960, p. 64). This is because the agendas of parliament, but also of the media have restricted carrying capacities (e.g., Jones and Baumgartner, 2005). So, politicians and journalists will always need to prioritize. When actors disagree and one side starts calling attention to the issue, a process of politicization may set in. In particular when both sides make an issue salient and if the issue polarizes, we have the largest degree of politicization. Yet, if only one side calls attention, but the other side does not, attention can easily wane. A second assumption is that actors behave strategically. So, they will try to politicize an issue if they think they can benefit and they will try to prevent politicization of an issue if this could harm them. They will primarily attempt to affect the salience of an issue rather than adapt their position. This assumption is supported by many studies which demonstrate long time periods of stability in the main dimension(s) of conflict (e.g., De Vries and Marks, 2012), as well as in the positions that parties take.

A third assumption is that events do not, by themselves make an issue more salient. For instance, the terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers in New York were conducted mainly by Saudi Arabian citizens, not by immigrants. While it makes sense that these attacks received a lot of attention in the media, it is not necessarily the case that they also raise attention to the situation of Muslims with a migration background in European countries. Making that connection is a strategic political move, usually by those who expect to benefit from doing so. So, events provide opportunities for the politicization of an issue but we see the actual politicization as a strategic act.

Below, we further explain the theoretical implications of these assumptions. After that, we will present analyses which focus on agenda setting, i.e., which types of actors set the agenda and which types of actors react to them. Then we will also present analyses in which we take into account the positions taken by different actors. We seek to uncover interactive processes in this regard: Suppose that a process of politicization is initiated by anti-immigration parties making negative remarks about immigrants, do other actors respond by making positive remarks, do they echo the anti-immigration parties, or do they simply ignore them?

Theoretical considerations

In order to understand how political conflicts develop, one must take into account position taking on the issue (how polarized these positions are), as well as how those positions structure the incentives for political actors to pay more or less attention to the issue (salience). Conflict theory tells us that conflicts do not only divide those parties on the opposite sides of the conflict line, but also unite actors on the same side. If collective actors want to win a conflict, they will invest time and energy into seeking agreement and in building a coalition with like-minded collective actors. Once such a coalition is formed and trust is built, such a coalition is a valuable asset. Especially when parties have created a government coalition, this collaboration adds to their influence on policy making and to the career opportunities of the party leadership. As coalition parties have an incentive to keep the coalition intact, they will try to avoid putting issues on the agenda about which they disagree to such an extent that no acceptable compromise can be reached. Instead of fighting simultaneously at different fronts, they must decide “which battle do we want most to win?” (Schattschneider, 1960, p. 67).

This mechanism explains why party systems are often structured by one single overarching dimension, why, at a sub-system level, policy conflicts tend to be split in only two sides (Baumgartner et al., 2009) and why movement conflict often takes a unidimensional form (e.g., Meyer and Staggenborg, 1996). Even when more than one ideological dimension structures the conflicting principles that guide parties’ behavior, not all these dimensions become equally organized. Normally, political parties will organize coalitions with actors that are close on the conflict dimension that they consider most important. This becomes the dominant dimension of conflict, because parties have an incentive to avoid to ‘fight’ conflicts that do not correspond with this dimension, or that cannot be made compatible with it. This incentive connects the dimensionality of structural relations between political parties and the salience of issues in the party system. This matters a great deal, as noted by Riker (1996), p. 9 ‘people win politically (..) because they have setup the situation in such a way that other people will want to join them – or will feel forced by circumstances to join them’. Mainstream parties will attempt to ‘structure the world so they can win’ by emphasizing issues that are part of the dominant dimension of political conflict whereas the strategy of challengers ‘is to divide the majority’ by emphasizing issues on which other actors do not dominate (Riker, 1996, p. 9; also see: Hobolt and de Vries, 2015; Sagarzazu and Klüver, 2017).

Several studies show that party positions on the issue of immigration are strongly correlated with left/right positions, at least at the time of our study (e.g., Van der Brug and Van Spanje, 2009; Lefkofridi et al., 2014). So, the structure of the party systems imposes few limits on mainstream parties addressing the issue. However, the potential voters for most mainstream parties in Western Europe are deeply divided on the issue of immigration (see, e.g., Givens and Luedtke, 2005; Bale et al., 2010). So, immigration is an issue that mainstream parties would generally not want to politicize, because this could only hurt them electorally. If mainstream parties could exercise full control over the political or media agenda, they would most probably try to keep the issue off the agenda. Yet, neither the governing parties nor even mainstream parties as a group can exercise full control over the political agenda.

When a potential issue exists in public opinion but is ignored by mainstream parties and politically relevant other actors, new parties may arise which explicitly emphasize this topic. They may do so especially around ‘wedge issues. which are issues that have the potential of “driving a wedge into governing party platforms” (Van de Wardt et al., 2014, p. 986). Examples of such issues are environmental protection, European unification and immigration. When the positions of challenger parties on these issues are popular among a substantial group of voters, these challengers might electorally benefit from politicizing the issue, whereas mainstream parties have a clear interest in keeping the issue off the agenda. When challengers are successful in mobilizing support on the basis of their stands on an issue, they automatically become the issue owners.3

When an event occurs, such as 9/11 or the ‘cartoon crisis. this provides opportunities for those who wish to politicize the issue of migration. If we conceive of politicization as a bottom-up process, we would thus expect anti-immigration parties or other radical right movements to put the issue high on the agenda after such events and we would then expect the issue to become politicized because mainstream parties, pro-immigrant movements and other civil society actors would feel forced to react. In their monograph on the politicization of the issue of immigration during the 1990s, Koopmans et al. (2005) focus on the role of grass root organizations and anti-immigration parties. They explain differences in the rise of these grass root movements by the (actor-specific) opportunity structures in each of the countries that they study. Like Koopmans et al. (2005), much of the work in this field does not explicitly attempt to explain politicization, but rather focuses on the (electoral) success of the parties that politicize wedge issues, either referred to as niche parties (e.g., Meguid, 2008) or challenger parties (e.g., De Vries and Hobolt, 2012, 2020). Yet, scholars in this tradition see processes of politicization arising largely from the ‘bottom-up’ activities of challengers, be it grass root organizations or parties. Please note that even though anti-immigration parties may have parliamentary seats and as such may initiate politicization from the ‘top-down. we consider them to be political outsiders who challenge existing power relations largely relying on the political repertoire of challengers and are therefore more properly associated with bottom-up processes of politicization.

As noted earlier, Green-Pedersen (2012) argued, however, that mainstream parties exercise quite a lot of control over the political agenda. When the issue that is owned by a niche party is harmful to the interests of mainstream parties as a group, they will jointly try to keep the issue off the political agenda. However, keeping an issue off the public or media agenda seems to be difficult or even impossible in countries with press freedom. When anti-immigration parties voice their harsh criticisms of migration policies, one would expect their quotes to have a lot of news value, similar to the news values produced by the ‘events and drama’ of social movement action (e.g., Gamson and Wolfsfeld, 1993). So, one would expect them to receive much media attention. Yet, according to Bennett’s (1990) indexing theory, reporters tend to base their coverage of politics on a ‘authoritative’ elite of ‘credible news sources’ (also: Bennett et al., 2007; Van Dalen, 2012). When mainstream parties disagree, opinions of these elites will reflect the different sides of this debate. However, when the mainstream parties agree, opposition voices tend to be marginalized (a similar effect has been noted for social movements, e.g., Tarrow, 1998, p. 66). To the extent that this perspective is valid, we will observe no politicization of the debate on immigration after these events. There may be some instances where anti-immigration parties raise the issue, but this will be largely ignored.

Even though we think that Bennett (1990) and Green-Pedersen (2012) are correct when pointing out selection mechanisms in the media, there are good reasons to expect that anti-immigration parties will play an important role in the politicization of the issue, especially if these parties are large. Small anti-immigration parties have as much interest in trying to call attention to the migration issue as larger anti-immigration parties. Yet, for two reasons larger parties can be expected to receive more attention than smaller ones. First, news values theory predicts that it will be difficult for the media to ignore the opinions of anti-immigration parties if they represent a large portion of the population. A second related reason is that larger parties have more influence in parliament. They get more time during debates to elaborate on the policies they propose and when trying to find parliamentary majorities for proposals, it is more difficult for other parties to ignore them. So, a larger party is a more important player in parliament than a smaller one, and, as predicted by indexing theory, the media tend to pay more attention to larger parties than to smaller ones.

When getting media attention for an issue, the question is how other parties will respond. Even if a small anti-immigration party manages to get some media attention, the most rational response of mainstream parties is probably to ignore the issue and the anti-immigration party, hoping that attention for the issue will soon wane (e.g., Meguid, 2008). However, when a larger anti-immigration party receives media attention, this strategy of ignoring may not work. First of all, as larger anti-immigration parties have easier access to the media, attention for the issue may not wane so quickly. Secondly, if the issue does not wane, mainstream parties will be afraid of being accused of ignoring an important issue (e.g., Sigelman and Buell, 2004). In that case, anti-immigration parties may be seen by many citizens as better representatives of their opinions, which would make the strategy of ignoring very risky. So, if larger anti-immigration parties try to politicize the issue, we expect mainstream parties to either confront, or to accommodate (Meguid, 2008). A confrontational strategy produces full politicization (i.e., in terms of salience as well as polarization) and an accommodative strategy should lead to weaker politicization in which salience goes up shortly, but positional differences between mainstream and anti-immigration parties remains low.

In addition to the size of an anti-immigration party, there is also another element that affects the strategic considerations of anti-immigration parties: whether they are in government or in opposition. When an anti-immigration party is part of a governing coalition, there will be more constraints on its desire to politicize the issue than when the party is in opposition (Strom, 1990). When in government, they are partially responsible for the government’s policies. This makes it difficult for them to criticize the government for not having more strict migration and integration policies. Moreover, parties in government coalitions need to collaborate in order to be effective and to implement their desired policies. In order to maintain good working relations with other government parties, anti-immigration parties will be likely to moderate their tone somewhat (but see: Akkerman, 2012; Akkerman and Lange, 2012). This does not mean they will be silent about their core issue, but we expect them to be less eager to strongly politicize the issue than when they are in opposition.

So, when an event occurs and there is a large issue owner in opposition, we can expect them to try increase the saliency of the issue. In the case of the immigration issue, anti-immigration parties are the most obvious issue owners, especially in ‘associative’ terms (Walgrave et al., 2012). In case the immigration issue becomes salient, mainstream parties may choose to confront anti-immigration parties, which could lead to a further polarization of the issue, or they may choose to accommodate. We cannot a priori predict how they will respond. So, rather than formulating strong hypotheses, we will explore the patterns of politicization on the basis of the following three research questions:

1. Is there a relationship between the number of opposition seats of anti-immigration parties and the salience of the issue after an event?

2. Which actors drive to the politicization of an issue?

3. What are the dynamics by which the actors react to each other?

Data and research design

Political claims analysis

We use political claims analysis of newspaper articles to measure politicization of migration. In this section we will discuss four aspects: the type of public political behavior observed, what news media tell us about the politicization of issues, the operationalization of salience and polarization, and the sampling frame used.

Political claims-making is a certain type of political behavior defined as “the purposive and public articulation of political demands, calls to action, proposals, criticisms, or physical attacks, which, actually or potentially, affect the interests or integrity of the claimants and/or other collective actors” (Koopmans et al., 2005, p. 254, see also Koopmans and Statham, 1999, p. 207). Claims must be political, in the sense that they relate to collective social problems and their solutions, and not to individual problems. They need not be political in the sense that they refer to (changes or initiations of) government policies. The core components of a claim are similar to what Lasswell (1948), p. 37 has defined as core components of political communication: ‘who? says what? to whom? in which channel? with what effect?’. As is common in claims analysis (Koopmans et al., 2005, pp. 254–59), we make a distinction between a subject actor (i.e., the claimant), the addressee, the form, the object actor, the topic of the claim, as well as the frame used to justify the claims. We only use the information on the subject actor in this article (see Berkhout, 2015 for a detailed overview of the project of which the data collection was part). Claim making is in many ways the core business of politicians and other political actors. They do so by, for instance, sending press statements, publishing reports or, in the case of government actors, initiating policy program. Political claims analysis has been successfully used to measure Europeanisation of public spheres (Koopmans and Statham, 2010), to examine the discursive context of migrant mobilization [Localmultidem and Eurislam projects (Cinalli and Giugni, 2013)] and to assess the political effect of citizenship regimes (Koopmans et al., 2005).

We observe claims in newspapers. In principle, one could observe claims-making in various different areas such as by examining police records to count protests, by recording press statements or by coding parliamentary debates. However, such sources only record political activities of certain types of political actors such as social movements or actors appearing in parliament. For that reason, practically all political claims analysis relies on newspapers as a source in order to document claims by various types of political actors, most notably governments and other state actors, civil society actors and political parties. In contrast to research in communication science, we are not specifically interested in media effects or the role of the media in contextualizing political claims. Our analysis includes all organizations who appear as claim-makers, also non-party actors such as government officials, political activists and companies. For parts of the analysis we focus on only those actors of which the party affiliation is reported or may be directly inferred from the reporting.

Questions have been raised about the validity of the use of newspapers to study the political agenda (e.g., Franzosi, 1987), as we do not know the exact criteria used by the newspaper editors to select claims out of a total, unknown population of claims (also see: Mügge, 2012). Research in this area shows that claims of government actors are somewhat overrepresented in newspapers (Bennett, 1990). While one could thus argue that this introduces systematic measurement error in our data, we do not think that this is a major problem. First of all, research shows that selection bias is a relatively limited problem (Earl et al., 2004), and here are no reasons to assume that this error substantially changes over time or that the bias is larger in some countries than in others. So, for the purpose of comparing over time and across countries, the problem is limited. Secondly, and more importantly, the purpose of our study is to draw inferences about the politicization of an issue. Organizations that want to make claims, but are unable to get their claims into the media, have very little political impact. Everyone (average citizens, politicians, journalists, pundits) gets his or her politically relevant information through the media. So, even if the media are selective in their attention, this ‘media bias’ becomes part of the political reality that we want to observe. There is no politically relevant public sphere that exists outside of the media. So, by observing claims in the media, we tap directly into the public debate on migration. We would thus argue that the filter function of the news media is actually beneficial as it works as a selection threshold for the inclusion of claims in our study. Last, in terms of validity or ‘description bias. positional information gathered through political claims analysis of news media is consistent with positional data derived from other sources, most notably party manifestos (Helbling and Tresch, 2011). Newspaper articles4 potentially containing claims about migration or integration have been manually selected by browsing through physical or microfilm versions of the newspaper. We take a broad definition of migration and also include issues related to migrant integration.5 The politicization of cultural differences between migrant communities (also later generation) and the ‘native’ population is therefore explicitly included. This increases the breadth of politicization opportunities following the events studied, including related to Islam.

In the analysis presented in this paper we exclusively focus on the subject actor and the positions taken on the claims. The primary indicator of salience is the number of claims per day. This is the most straightforward and clearest indicator, and especially suited for within country over time analysis. Yet, when analyzing the interactions between the different actors, we also want to take into account the positions of political actors on immigration. For this purpose each claim was classified on a five-point scale, ranging from ‘strongly restrictive to migrants/conservative/pro-national residents/mono-cultural’ (−1) to ‘strongly open to migrants/progressive/cosmopolitan/multi-cultural’ (+1). In order to analyze conflict, we will estimate whether positive claims by one type of actor, provoke negative claims by others, or vice versa. To conduct the analyses that take positions into account, we summarized the positions of all claims of an actor type, so that we combine salience and positions in the second set of analyses. An analysis of just changes in positions is impossible, because there are too many days in which some actor types make no or hardly any claims, so that positions cannot be measured in a reliable way.

Coders were trained until they were able to meet the generally agreed minimum standards of inter-coder reliability. On a sample of 20 British articles the 32 coders on average and pair-wise agreed about the identification and subject actor in 78 percent of the 60 claims (Krippendorff’s Alpha of 0,55). This limits the confident use of the data to certain purposes only. More to the point, the main source of intercoder differences relates to subject actor categories without party-political affiliation and at relatively high levels of specificity such as claims made by public agencies, NGOs, semi-public corporations and so on. In this paper, we use only claims made by party-affiliated actors and we are confident that intercoder differences hardly occurred in this part of the data. In addition, these scores probably underestimate the actual intercoder reliability as most of the claims have been coded by a smaller team of coders who more strongly agreed among each other and because the test was performed at the beginning of the coding procedure (with agreement increasing with coding experience). We did not do a separate intercoder reliability test for exactly the variables and categories used in this paper, at a later stage with more experienced coders or per language-specific coding team. We closely coordinated the coding throughout the data collection process. All the data are archived on Harvard Dataverse (for details see: Berkhout, 2015). We use newspaper articles published on (1) a random sample of days over a long time period and (2) all days following three events. The claims coded on the random sample of days provide the base-line measure of the salience and polarization of the issue. We use the information collected outside the relevant event-related time period to assess the change in attention.

Country selection

We selected the countries so as to obtain variation in two characteristics (for an elaborate discussion of the research design, see: Berkhout et al., 2015). The first one pertains to the number of immigrants the countries have attracted and the time when migration began. We selected three countries with a colonial past, which started to attract large numbers of migrants already in the late 1960s (the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Belgium), two countries without a colonial past but which were also early migration countries using ‘guest workers’ programs (Austria and Switzerland), and two countries that only began to attract large numbers of immigrants from the late 1990s onwards (Spain and Ireland).

The second characteristic on which we wanted the countries to vary is whether the country has a party system dominated by two large parties (Spain and the United Kingdom), or a multi-party system (the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, Switzerland and Ireland). The number of parties in a party system is expected to be important for the way in which the issue will be politicized. In proportional electoral systems it may be more likely that much of the politicization will come from radical parties, and that established parties cannot ignore it. In two party systems, the politicization will be less driven by parties, and potentially takes place outside of the parliamentary arena and be driven more by civil society groups and by journalists.

The three ‘potentially triggering events’

Our analysis focusses on the immediate aftermath of three events that potentially trigger politicization. These events are: ‘9–11’ (11 September to 6 October 2001), the riots in the Paris Banlieus (27 October to 26 November 2005), and the publication of anti-Islam Cartoons in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, which lead to many protests and riots, in Islamic countries as well as in Europe (28 January to 11 March 2006). These three events were carefully selected on the basis of three criteria.

First of all, these should be events that have the potential to raise awareness of problems associated with the presence of immigrants in Western democracies, so that actors who want to politicize the issue of immigration can use these events as an opportunity to do so. Given the elaborate responses of political actors in the countries were these events occurred there were opportunities for actors elsewhere to also do so. A second criterion is that the events should be highly visible in the media. As will be further shown in our analysis, the events meet this criterion as well. A third criterion is that the potential impact of the events should be the same in each of the countries that we studied. We therefore selected events that did not take place in any of the countries that we studied, so that, in all countries studied there is more or less the same probability that it potentially produces political contestation. We therefore excluded events that happened in one of the countries that we investigate, such as the murder of Theo van Gogh in the Netherlands in 2004, the bombings of the Madrid metro in 2004 or the London terrorist bombing in 2005. The events that we selected gave rise to discussions about the presence of migrants in the countries where the events occurred. As we will see, they elicited very different reactions in the seven countries that we investigate.

The main challenger parties

The anti-immigrant parties included are the Dutch opposition party PVV which held around 6 % of the parliamentary seats during the Banlieus and Cartoons events, the Belgian opposition parties Vlaams Blok/Belang (around 12 percent) and small Front National, the Austrian FPÖ which was in government during all events and held 28 percent of the parliamentary seats during 9–11 and around 10 percent during the other events, and the Swiss government-coalition party SVP (around 27 percent of the seats). We also observe a very low number of claims by the British BNP and its inclusion does not affect the findings, especially given its absence from parliament (also see discussion in: Carvalho et al., 2015). There are no relevant Irish and Spanish anti-immigrant parties in the time-period studied. Parties who participate in government coalitions are considered governing parties, also when they are junior partners or when part of a consensus-governing system as in the Swiss case.

Results

We formulated three research questions in the theoretical section, and we will answer each of them in turn. We first examine the variation in the level of salience of migration and integration issues in the post-event weeks and assess whether there is a relationship between the pre-existing polarization of an issue and the salience of the issue after an event. We proceed with outlining the differences in the types of actors involved in politicization and, by means of vector autoregression (VAR) time series analyses of the interaction among actors in the immediate aftermath of the events studied.

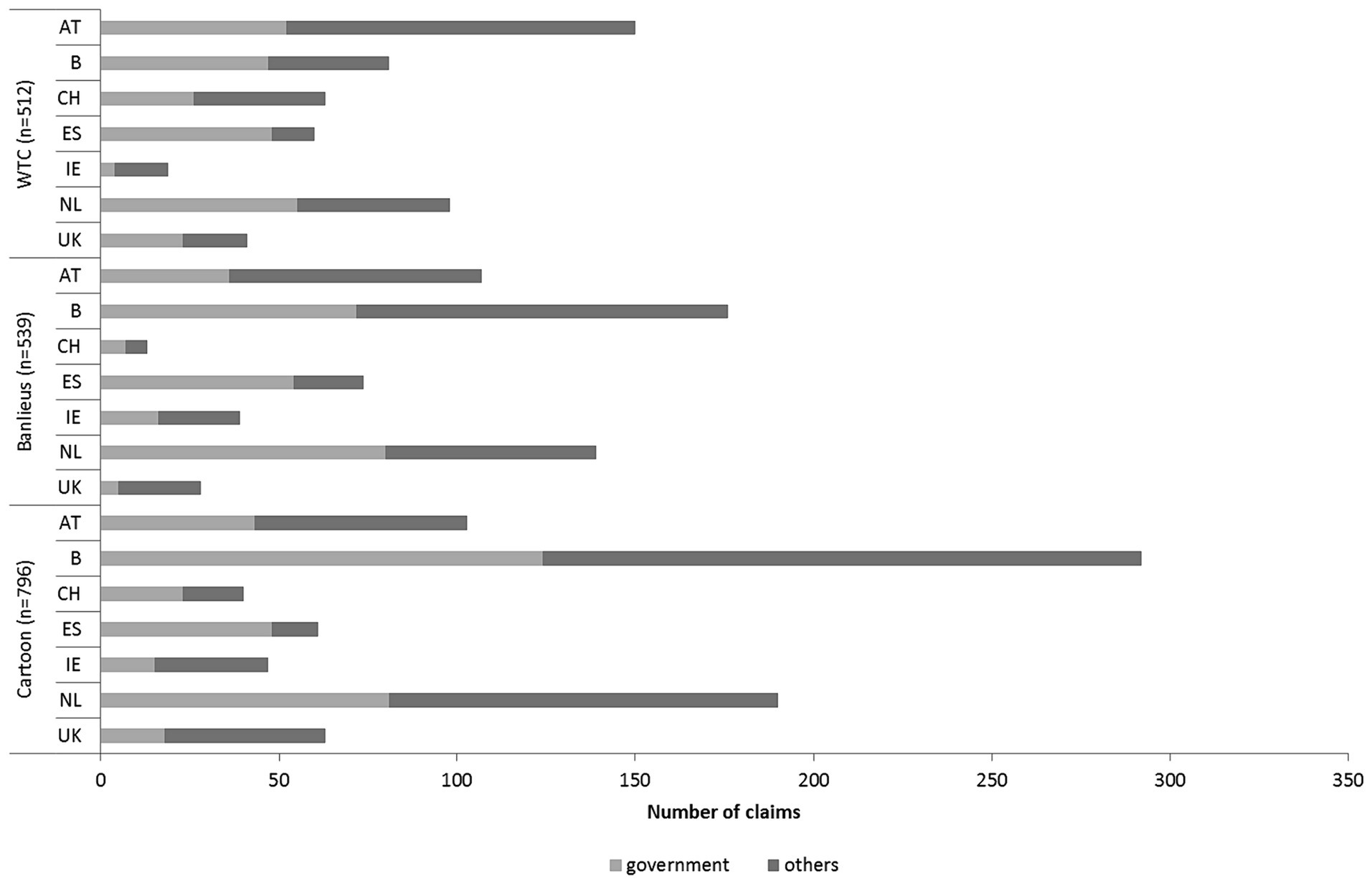

Figure 1 presents the number of claims per event and country. In general, the figure shows that there is substantial variation in the salience of migration in the weeks following the events which merits explanation. The Cartoons event produced substantially larger number of claims than the riots in the Banlieus in Paris and the attack on the WTC in New York. Remember that this does not reflect the general level of level of attention to these events, but more specifically reflects the political attention to migration and integration issues in the post-event weeks. It seems that the Cartoons event is more frequently associated with migration and integration than the other two events studied. In some countries these events did not generate increased attention to migration and integration. This is for instance the case for the WTC event in Ireland and the Banlieus riots in Switzerland. In these cases, the low number of claims makes it very unlikely that we will detect meaningful patterns of interactions among actors over time. This must be considered when we evaluate the results of our analyses below. However, Figure 1 indicates that there is relevant and substantial variation in the types of actors (government or not) involved in claims-making. This variation makes it possible to assess the interaction between different types of actors, as we will do further below.

Before we proceed, we want to make sure that the attention to the issue of migration after these events is indeed largely triggered by these events, and is not simply a reflection of the attention to migration before these events occurred. For that purpose, we compared the average number of claims per day of a sample of days in the year before these three events with the average number of claims in the 4 weeks following these events. In the period before the events, there were on average 1.5 claims on migration made in the newspapers per sampled day (based on a random sample of days) and in the 4 weeks after the events, it was on average 3.1. So clearly, the events triggered more attention. Even more important for the purpose of our study is that the attention before and after the event are virtually uncorrelated (r = −0.025). We will not include the pre-existing salience in the analyses presented below as the absence of correlation means that the differences between the countries in how actors responded to these events are independent from the existing salience of the issue. So, what explains these differences?

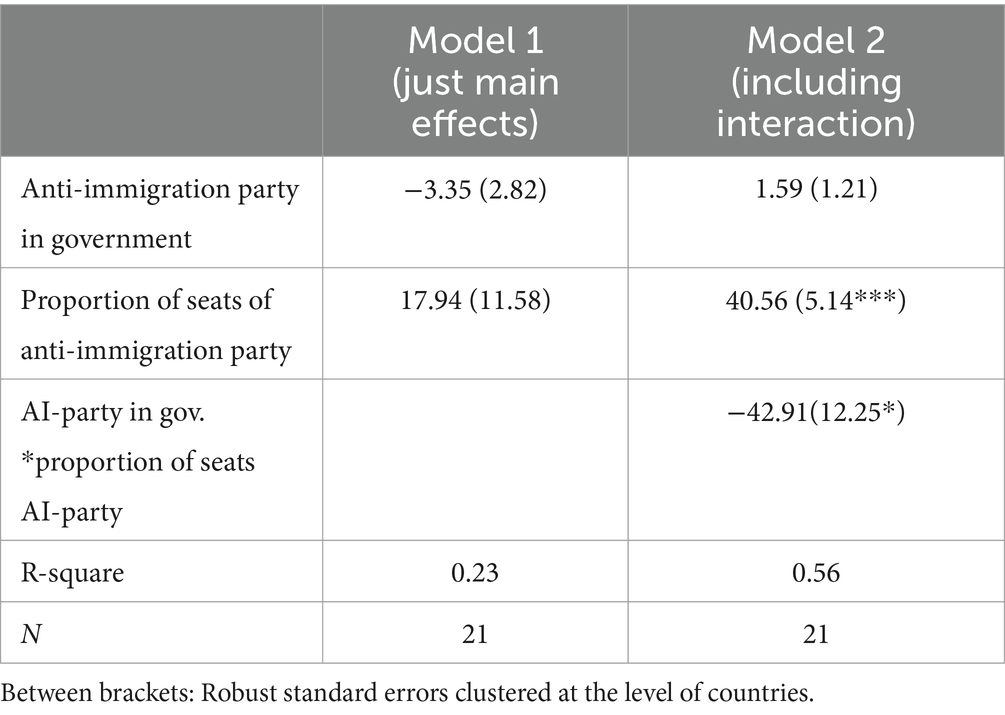

Our first research question was whether there is a relationship between the number of opposition seats of anti-immigration parties and the salience of the issue after an event. In order to assess whether such a relationship exists, we conducted a regression analysis in which we predict the attention to the issue of immigration in terms of the numbers of claims made after the events based on the size of the anti-immigration party in each country at the time (measured in proportion of seats in parliament), whether the anti-immigration party was in government (a dummy variable) and the interaction between these two. Since the observations are not independent, we estimated robust standard errors clustered by seven countries. The results are presented in Table 1.

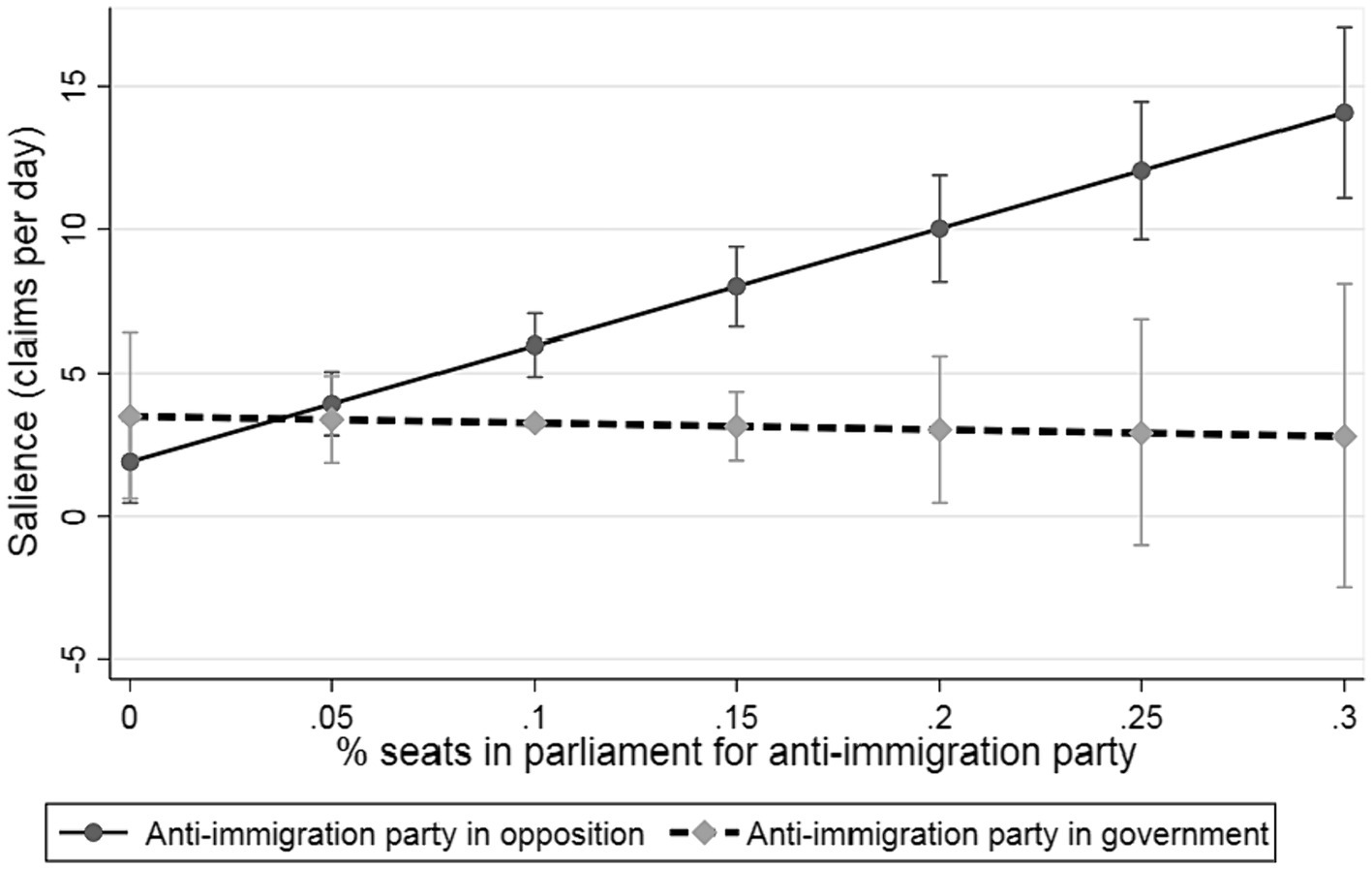

To answer the first research question, we should focus on the interaction effect. However, to show that the interaction drives the results and not just the two main effects, Model 1 is a model that includes the main effects only. Model 1 shows that the salience of the issue of immigration increase when anti-immigration parties are larger and when they are in the opposition. However, these effects are not statistically significant. The same is true for the simple bivariate correlation between the salience of the immigration issue on the one hand and on the other hand the vote share of anti-immigration parties (r = 0.26; p = 0.26) and whether the anti-immigration party is in government (r = −0.04; p = 0.88). However, the effect of the size of the anti-immigration party becomes significant (at p < 0.001) when the distinction is made between anti-immigration parties in government and in opposition. The main effect of the size of an anti-immigration party has a regression coefficient of about 40. This indicates that the average number of claims per day is predicted to increase by 4 if the anti-immigration party in opposition has a 10% larger share of seats. The negative interaction term with government party status indicates that there is no effect from the size of the anti-immigration party in government. This suggests that the effect of the presence of anti-immigration parties on (public) political salience depends on the strategic considerations of these parties.

Figure 2 shows graphically the estimated effects of the size of anti-immigration parties in office and in opposition. These are substantial effects: as can be seen in Figure 1, a ‘typical’ event such as the ‘Cartoon’ event attracts around hundred claims in Austria in total or around three to four claims per day in the immediate aftermath of the event. This is fundamentally different when there is a sizeable anti-immigration in opposition. Figure 2 shows that when such a party holds 20 % of the parliamentary seats, we expect around 10 claims per day after a triggering event.

Patterns of politicization over time

We use VAR analysis for a formal assessment of interaction among actors. This is a typical and flexible way to analyze time series (e.g., Freeman et al., 1989). We have daily observations of the claims in the media. While we have explored models with several time lags, most of the observed effects occurred with a time lag of one single day. Given how the media work, it is likely that actors respond to each other on the same day, but that does not allow us to observe any causal patterns as this requires at a very minimum that there is a temporal order. So, we present models in which we estimate how different types of actors respond to each other the next day, and therefore allow for only a single lag in the analysis. Similar to OLS regression a VAR analysis produces coefficients with positive or negative signs. The significance of the affects will be tested on the basis of so-called Granger causality tests.

For these VAR analyses we differentiate among actors in two ways: (1) Actors affiliated with government-coalition parties versus all other political actors and, (2) government, opposition and anti-immigration parties, focusing on actors with an explicit party affiliation only. The first distinction allows us to evaluate the extent to which politicization is government, top-down driven or is initiated from the bottom-up. The second distinction makes it possible to examine the interactions between political parties. For each of these types of actors we constructed a time series that measures the claim making of these types of actors on each of the roughly 30 days following the event. Claims by actors affiliated to governing anti-immigration parties are in the anti-immigration party category. In each case we conduct separate analyses for salience and for position. When distinguishing between governing-coalition actors and all other actors, we conduct these analyses for three events, seven countries and separately for salience and position taking. Since we make two different distinctions, we could have theoretically conducted 84 analyses. However, in several cases, the models could not be estimated, for two kinds of reasons. The first was that there was no anti-immigration party (in Ireland and Spain at the time). The second was that there was an insufficient number of claims coming from one of the types of actors, so that there was no or hardly any variance in one of the time series. In total, we were able to estimate 55 VAR analyses.

We examine salience and position taking, as the two important concepts that underlie the politicization of an issue. The first time series refers to the number of claims per actor type for each of the days. The time series for position taking is the sum of the positions that actors take on each of the claims. So, if on a certain day 8 claims appear in the media by government actors, which are positive and 2 of their claims are negative, the score is +6.

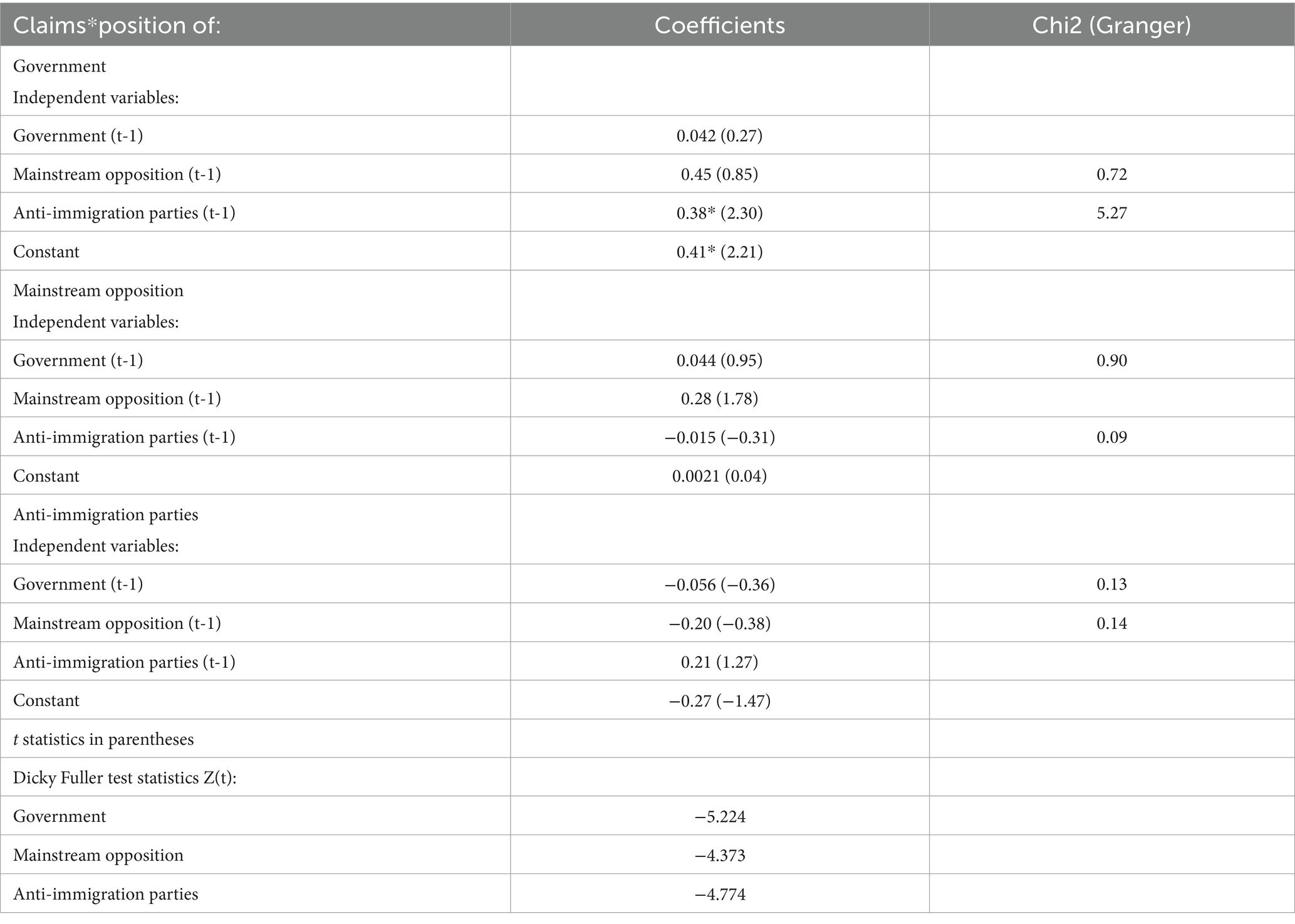

Obviously, we cannot present the results of 55 VAR analyses in much detail. So, we will only summarize the main results of these analyses below. Before we do so, for illustrative purposes we will discuss the results of the VAR analysis of the Cartoons event in Belgium. We selected this case, because it is the event that gave rise to the largest number of claims (see Figure 1). In Table 2 we present the result for the analyses involving three kinds of actors and their positions in the claims that they made. In the bottom rows of Table 2, we find the Dicky Fuller test statistics. These indicate that the null-hypothesis of non-stationarity must be rejected. The data, as in all of our time series, does not have a significant upward or downward trend, i.e., the positions of actors do not systematically change in the month after the event. The table further shows VAR analysis coefficients for the effect of positions of each actor-type on another actor type a day later. All coefficients are insignificant except the effect of the positions of anti-immigration parties on the positions of government actors. This means that anti-immigration party claims-making and position-taking leads to claims-making and position taking by government actors a day later. This effect is positive which means that government actors seem to react in the direction of the anti-immigration challengers. The table also reports the significance of the effects on the basis of the t-statistic, as well as the corresponding Chi2 Granger causality tests. Since we test for the effect of one lag only, the two significance tests are bound to yield the same results. In the analyses below, this is indeed the case, so the effects that we report as significant are significant by both tests.

Table 2. VAR analysis for the Cartoons event in Belgium on the within-actor politicization, n = 36, * p < 0.05.

Even though the number of claims in Belgium after the cartoon event was much larger than the number of claims in the other 20 cases, we must realize that the number of observations is limited. We observe 9 to 10 claims per day on average, divided over three actor types. We should not be surprised therefore to see that most of the effects are not statistically significant. Also, we should not, on the basis of the single significant effect of anti-immigration parties on governments conclude that the process of politicization is largely bottom up. To get a better indication of the extent to which the process tends to be bottom up or top down, we need to look at all VAR analyses. Appendix A presents the results of all 55 VAR analyses. For reasons of space, the main results of these 55 analyses are summarized in Tables 3–6.

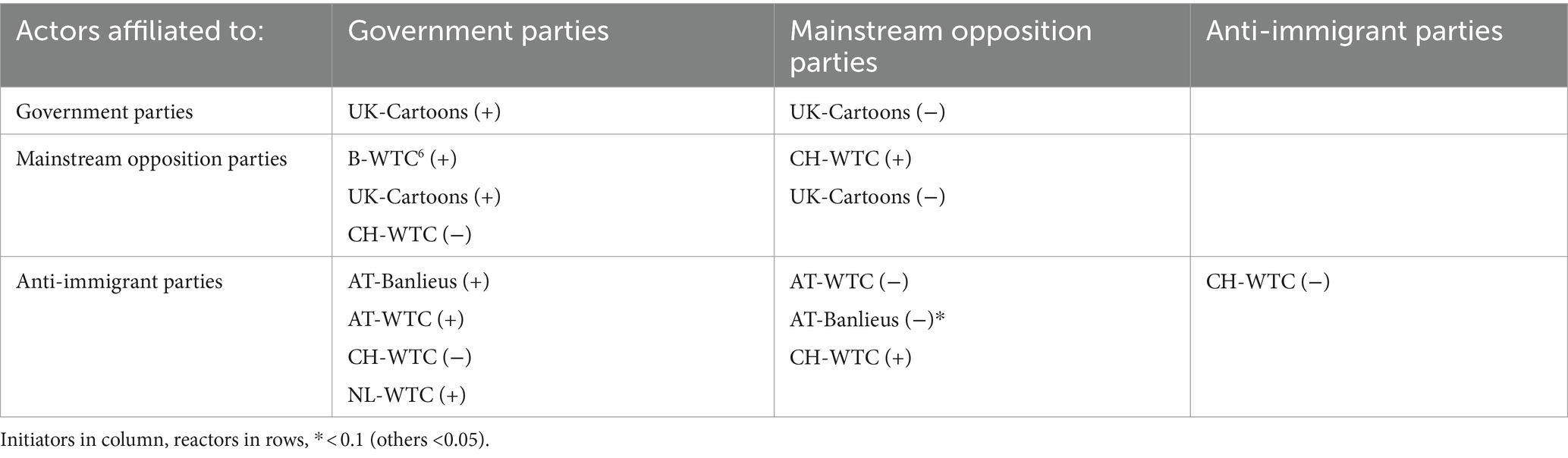

Table 3. Relationships with significant coefficients in VAR analysis, number of claims (salience), by event.

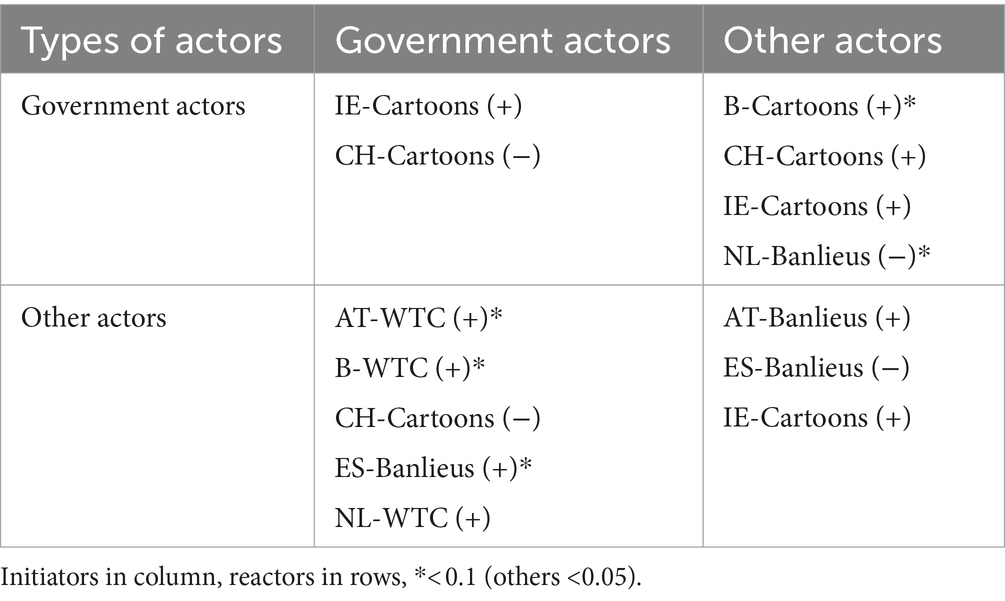

Table 4. Relationships with significant coefficients in VAR analysis, number of claims (salience), by event.

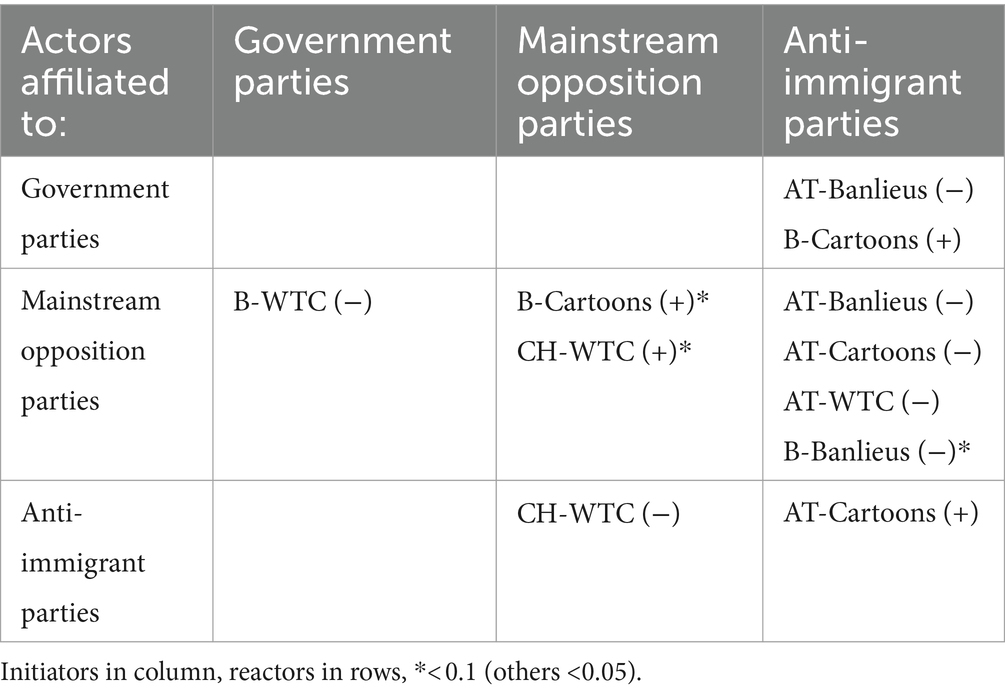

Table 5. Relationships with significant coefficients in VAR analysis, position-weighted claims (politicization), by event.

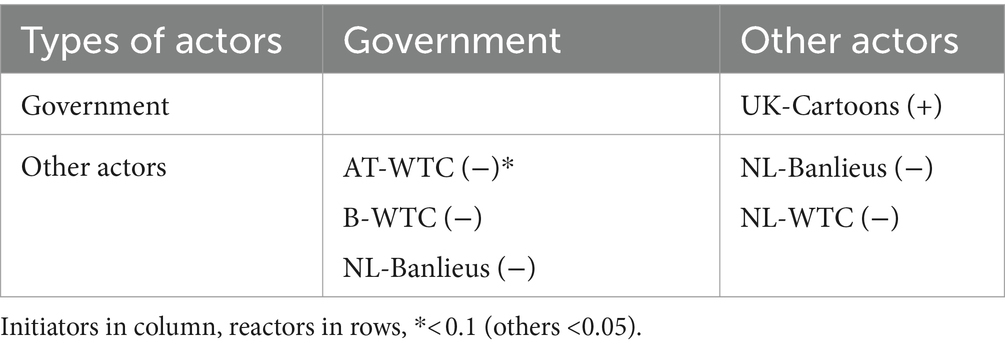

Table 6. Relationships with significant coefficients in VAR analysis, position-weighted claims (politicization), by event.

Tables 3–6 report only the significant effects and the direction of the effect. In all of these cases, the Granger causality tests confirmed that the effects were statistically significant. Tables 3, 4 present the relationships in terms of the number of claims (salience). The events in which certain relationships are significant (at 0,05 level, or * when at 0,1 level) are mentioned in the cells. In the columns are (as independent variables) the actors whose claims, according to the analysis, lead to claims of other actors (in the rows, as dependent variables). In the first column of Table 3 we see that government claims lead to more claims-making by opposition and anti-immigration parties in five cases (significant and positive). In two additional cases (CH-WTC) the effect is negative. This means that opposition and anti-immigration parties tend to become ‘silent’ after government claims-making. The second column of the same table shows that opposition claims lead to fewer claims by anti-immigration parties in Austria (WTC and Banlieus) and more in Switzerland. While in most cases no significant relationships were found, this suggests that in cases where there is a pattern, it is the government that sets the agenda, and opposition and anti-immigration parties react to the government. A similar pattern is shown in the first column in Table 4. In four cases the non-government actors tend to make more claims the day after substantial government claims-making, whereas in three cases it is the other way around.

Tables 5, 6 present the relationships in terms of positions. Do mainstream parties confront anti-immigration parties or is the politics on the issue relatively unpolarized? Most of the estimated effects are insignificant. However, as can be seen in Table 5, in Austria and Belgium we find that anti-immigration parties seem to initiate politicization. Government and more frequently mainstream opposition parties position themselves typically in the opposite direction of anti-immigration parties the day after these parties have spoken out on the topic. These are the examples of cases where the anti-immigration party was in opposition and large. The sole exception is Austria after the attack on the World Trade Center, when the FPÖ was a government party. However, at that time the party was deeply divided internally after Haider had resigned as a party leader. This might explain why (certain people within) the party were politicizing the issue even though their party was governing. Table 6 suggests that in countries without (strong) anti-immigration parties at the time of the events (United Kingdom and NL) other actors are sometimes successful in challenging the government on the issue.

Conclusion

This paper presented analyses about the political responses in seven countries to three events that could have led to the politicization of the issue of immigration: 9/11, the Cartoon crisis and the Banlieus riots. The extent to which the issue was politicized after these events turns out to be related to the electoral support of the main issue owner, when the issue owner is an opposition party. In all of the seven countries, mainstream parties have an incentive to depoliticize the issue of migration. So, when there are no issue owners who seize the opportunity provided by an event, they try to keep silent about it. When the issue owner (the anti-immigration party) is in government, attention to the issue remains rather limited as well. However, when there is a large anti-immigration party in opposition, there is little that established parties can do to keep the issue off the agenda.

Given that immigration is a ‘wedge issue’ that divides mainstream parties (e.g., Van de Wardt et al., 2014), anti-immigration parties have a strong incentive to try to try to politicize the issue. So, they have an incentive to seek media attention, link these events to immigration or integration policies, and in that way force mainstream other parties to respond. However, we found this to happen only when the anti-immigration party was large and in the opposition. In most of the cases anti-immigration parties are unsuccessful in getting their claims in the media, as predicted by indexing theory (Bennett, 1990). Moreover, when anti-immigration parties are small, they do not have much influence on the debate, because mainstream parties typically ignore them. Our VAR-analyses on a data set with daily observations are particularly well suited to unravel the ways in which different types of actors respond to each other. These analyses have shown that in most cases the debate is not initiated by anti-immigration parties. The general pattern that most times the debate is initiated by government actors, who initially set the tone and force others to respond to them.

So, in that sense, our analyses provide support for Green Pedersen’s (2010) argument that governments exercise much control over the political agenda. However, our analyses have demonstrated clearly that this needs to be amended. When a strong anti-immigration party exists, governments parties and mainstream opposition parties pay much more attention to the issue than they would otherwise do. So, the influence of the issue owner on the process of politicization is rather indirect. Most probably, it is the fear of a future loss in political support that induces mainstream parties to address the issue of immigration. We rely on a number of assumptions regarding the structure of party-political conflict and the strategic incentives of mainstream and challenging parties. For instance, we note that, based on Riker (1996) and Schattschneider (1960), political parties can set up the political situation in such a way that is potentially beneficial to them. Future studies could empirically examine how conflict dimensions or dominant issue frames affect the success of shaping the politicization of issues.

While we belief that our VAR analyses are well suited to unravel causal relationships, it may well be that media analysis requires even shorter time intervals. Journalists may pick up a claim by one of the actors and call around to ask others to respond the same day. Future research may be needed to further unravel these kinds of relationships, for instance by focusing on the addressee of the claims. With a sample of seven countries and three events, we cannot test our model against alternative explanations such as those related with particular characteristics of the event or country-specific institutional characteristics. So, future research would have to confirm our findings in other countries and in the context of different events.

The issue of immigration is perhaps the most divisive issue of the last decades in West European politics. According to many scholars, the politicization of this issue has led to a realignment of some of the party systems in this region of the world. The extent to which the issue was politicized varies between countries and over time, and turned out to be unrelated to migration statistics (e.g., Sides and Citrin, 2007; Berkhout, 2015). However, in the context of events that are related to immigration, such as the refugee crisis of 2015, the issue becomes more politicized and this benefits far right parties (e.g., Vasilakis, 2018; Dinas et al., 2019; Mader and Schoen, 2019; Emilsson, 2020), and also affects attitudes toward immigrants and the EU (e.g., Harteveld et al., 2018; Van der Brug and Harteveld, 2021). Yet, our study clearly shows that such events do not necessarily or automatically lead to the politicization of immigration, nor that these events are the real ‘cause’ of politicization. Rather, these events function as an opportunity or fertile ground for an issue to become politicized. Whether it does, depends on the characteristics of the party system, most notably whether there is an issue owner and whether it is in opposition or in government. Long-term structural forces are relatively strong in maintaining party system stability when event occur. But events provide opportunities for punctuated or incremental change, driven by radical right-wing parties. Given that far right parties have increased their vote share over the past decade (e.g., Rooduijn et al., 2023) and that they typically remain in the opposition nevertheless, it is now more likely than before that future events will lead to further contestation over the issue of immigration.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

WV: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review, editing. JB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review, editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This larger project was supported by the European Commission’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement number 225522 (SOM: Support and Opposition to Migration).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and the two reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions, which helped us to improve the article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2024.1314217/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^For instance, Kriesi et al. (2008) label this conflict dimension ‘integration-demarcation’, De Vries (2018) calls it the ‘cosmopolitan-parochial divide’ and Hooghe and Marks (2018) refer to it as the ‘transnational cleavage’.

2. ^Others also identify the framing of an issue as a dimension of politicization. We do not think that that is useful in this context given that framing, i.e., the selective highlighting of considerations in order to mobilize public opinion, is better understood as a political strategy of actors rather than a characteristic of an issue (Jerit, 2008). Also differences in the frame used, i.e., the justification provided by an actor for a position, tends to be a difference in kind rather than in degree, complicating its study as a dimension of issue conflict.

3. ^Here we use the term issue ownership in line with Van der Brug (2004),Bellucci (2006), and Walgrave et al. (2009), namely as the associative identification of a party with an issue.

4. ^The newspapers used are as follows. Austria: Der Standard; Belgium: De Standaard; Switzerland: Neue Zürcher Zeitung*; Spain: El Pais; Ireland: The Irish Times; The Netherlands: De Volkskrant; United Kingdom: The Guardian.

5. ^Definition of migration used: We cover government activities relating to the entry and exit of people from the country, including the general policy direction, the institutional framework, issues of border controls, visa policies, and actions related to illegal entry. We also cover social, cultural and economic conflicts, as well as issues related to social cohesion if they involve people with a migration background. In this context we cover government policies on targeted integration, language and citizenship programs, and issues on how migration affects existing government programs such as housing, education, or policing. As such, we also include coverage on the activities, problems, and social contributions of migrant communities.

References

Akkerman, T. (2012). Comparing radical right parties in government: immigration and integration policies in nine countries (1996–2010). West Eur. Polit. 35, 511–529. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2012.665738

Akkerman, T., and Lange, S. L. (2012). Radical right parties in office: incumbency records and the electoral cost of governing. Gov. Oppos. 47, 574–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2012.01375.x

Andrione-Moylan, A., De Wilde, P., and Raube, K. (2023). (De-) politicization discourse strategies: the case of trade. JCMS. J. Common Mark. Stud. 62, 21:37. doi: 10.1111/jcms.13475

Bale, T., Green-Pedersen, C., Krouwel, A., Luther, K. R., and Sitter, N. (2010). If you can’t beat them, join them? Explaining social democratic responses to the challenge from the populist radical right in Western Europe. Political studies, 58, 410–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00783.x

Baumgartner, F., Berry, J. M., Hojnacki, M., Kimball, D., and Leech, B. (2009) Lobbying and policy change: who wins, who loses and why. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Baumgartner, F. R., and Jones, B. D. (1993) Agendas and instability in American politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bellucci, P. (2006). Tracing the cognitive and affective roots of “party competence”: Italy and Britain, 2001. Elect. Stud. 25, 548–569. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2005.06.014

Bennett, W. L. (1990). Toward a theory of press-state relations. J. Commun. 40, 103–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1990.tb02265.x

Bennett, W. L., Lawrence, R. G., and Livingston, S. (2007) When the press fails. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Berkhout, J. (2015). “Technical appendix: political claims analysis” in The politicisation of migration (extremism and democracy). eds. W. Van der Brug, G. Damato, J. Berkhout, and D. Ruedin (London: Routledge), 197–206.

Berkhout, J., Ruedin, D., van der Brug, W., and Amato, G. D. (2015). “Research design” in The politicisation of migration (extremism and democracy) eds. W. Van der Brug, G. Damato, J. Berkhout, and D. Ruedin (London: Routledge), 19–30.

Birkland, T. A. (1997) After disaster: Agenda setting, public policy, and focusing events. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Birkland, T. A. (2004). “The world changed today”: agenda-setting and policy change in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks. Rev. Policy Res. 21, 179–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-1338.2004.00068.x

Braun, D., and Tausendpfund, M. (2016). “The impact of the euro crisis on citizens‧ support for the European Union” in Coping with crisis: Europe’s challenges and strategies. eds. J. Tosun, A. Wetzel, and G. Zapryanova (Abingdon: Routledge), 37–50.

Carmines, E. G., and Carmines, E. G. (1989) Issue evolution: Race and the transformation of American politics, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Carvalho, J., Eatwell, R., and Wunderlich, D. (2015). “The politicisation of immigration in Britain” in The politicisation of migration. eds. W. Van Der Brug, G. D’Amato, J. Berkhout, and D. Ruedin (Oxon, New York: Routledge), 1–18.

Cinalli, M., and Giugni, M. (2013). Public discourses about Muslims and Islam in Europe. Ethnicities 13, 131–146. doi: 10.1177/1468796812470897

Cobb, R. W., and Elder, C. D. (1983) Participation in American politics: The dynamics of agenda-building, 2nd Edn. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

De Vries, C. E. (2018). The cosmopolitan-parochial divide: changing patterns of party and electoral competition in the Netherlands and beyond. Journal of European Public Policy, 25, 1541–1565. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2017.1339730

De Vries, C. E., and Hobolt, S. (2020). Political entrepreneurs: The rise of challenger parties in Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

De Vries, C. E., and Hobolt, S. B. (2012). When dimensions collide: the electoral success of issue entrepreneurs. Eur. Union Polit. 13, 246–268. doi: 10.1177/1465116511434788

De Vries, C. E., and Marks, G. (2012). The struggle over dimensionality: a note on theory and empirics. Eur. Union Polit. 13, 185–193. doi: 10.1177/1465116511435712

De Wilde, P. (2011). No polity for old politics? A framework for analyzing the politicization of European integration. J. Eur. Integr. 33, 559–575. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2010.546849

De Wilde, P., and Zürn, M. (2012). Can the politicization of European integration be reversed?. JCMS. J. Common Mark. Stud. 50, 137–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5965.2011.02232.x

Dinas, E., Matakos, K., Xefteris, D., and Hangartner, D. (2019). Waking up to golden dawn: does exposure to the refugee crisis increase support for extreme-right parties? Polit. Anal. 27, 244–254. doi: 10.1017/pan.2018.48

Earl, J., Martin, A., McCarthy, J. D., and Soule, S. A. (2004). The use of newspaper data in the study of collective action. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 30, 65–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110603

Emilsson, H. (2020). “Continuity or change? The impact of the refugee crisis on Swedish political parties’ migration policy preferences” in Forced migration and resilience. eds. M. Fingerle and R. Wink (Wiesbaden: Springer), 99–121.

Franzosi, R. (1987). The press as a source of socio-historical data: issues in the methodology of data collection from newspapers. Hist. Methods 20:5. doi: 10.1080/01615440.1987.10594173

Freeman, J. R., Williams, J. T., and Lin, T. M. (1989). Vector autoregression and the study of politics. American Journal of Political Science,842–877. doi: 10.2307/2111112

Gamson, W. A., and Wolfsfeld, G. (1993). Movements and media as interacting systems. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 528, 114–125. doi: 10.1177/0002716293528001009

Givens, T., and Luedtke, A. (2005). European immigration policies in comparative perspective: Issue salience, partisanship and immigrant rights. Comparative European Politics, 3, 1–22. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110051

Grande, E., and Hutter, S. (2016). “European integration and the challenge of politicisation” in Politicising Europe (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 3–30.

Green-Pedersen, C. (2007). The growing importance of issue competition: the changing nature of party competition in Western Europe. Polit. Stud. 55, 607–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00686.x

Green-Pedersen, C. (2010), New Issues, New Cleavages, and New Parties: How to Understand Change in West European Party Competition. Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1666096 or (Accessed August 26, 2010)

Green-Pedersen, C. (2012). A giant fast asleep? Party incentives and the politicisation of European integration. Polit. Stud. 60, 115–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00895.x

Green-Pedersen, C., and Krogstrup, J. (2008). Immigration as a political issue in Denmark and Sweden. Eur J Polit Res 47, 610–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00777.x

Harteveld, E., Schaper, J., de Lange, S., and van der Brug, W. (2018). Blaming Brussels? The impact of (news about) the refugee crisis on attitudes towards the EU and national politics. J. Common Mark. Stud. 56, 157–177. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12664

Helbling, M., and Tresch, A. (2011). Measuring party positions and issue salience from media coverage: discussing and cross-validating new indicators. Elect. Stud. 30, 174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2010.12.001

Hobolt, S. B., and De Vries, C. E. (2015). Issue entrepreneurship and multiparty competition. Comp. Pol. Stud. 48, 1159–1185. doi: 10.1177/0010414015575030

Hooghe, L., and Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 25, 109–135. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

Hutter, S., and Kriesi, H. (2020). “Politicizing Europe in times of crisis” in The European Union beyond the Polycrisis? eds. J. Zeitlin and F. Nicoli (Abingdon: Routledge), 34–55.

Jerit, J. (2008). Issue framing and engagement: rhetorical strategy in public policy debates. Polit. Behav. 30, 1–24. doi: 10.1007/s11109-007-9041-x

Jones, B. D., and Baumgartner, F. R. (2005) The politics of attention: How government prioritizes problems, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Koopmans, R., and Statham, P. (1999). Political claims analysis: integrating protest event and political discourse approaches. Mobilization 4, 203–221. doi: 10.17813/maiq.4.2.d7593370607l6756

Koopmans, R., and Statham, P. (2010) The making of a European public sphere: Media discourse and political contention. Ithaca, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Koopmans, R., Statham, P., Giugni, M., and Passy, F. (2005) Contested citizenship: Immigration and cultural diversity in Europe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., and Frey, T. (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lasswell, H. (1948). “The structure and functions of Communications in Society” in The communication of ideas. ed. L. Bryson (New York: Harper)

Lefkofridi, Z., Wagner, M., and Willmann, J. (2014). Left-authoritarians and policy representation in Western Europe: electoral choice across ideological dimensions. West Eur. Polit. 37, 65–90. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2013.818354

Mader, M., and Schoen, H. (2019). The European refugee crisis, party competition, and voters’ responses in Germany. West Eur. Polit. 42, 67–90. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2018.1490484

Mair, P. (1998) Party system change: Approaches and interpretations. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Meguid, B. M. (2008), Party competition between unequals: Strategies and electoral fortunes in Western Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Meyer, D. S., and Staggenborg, S. (1996). Movements, countermovements, and the structure of political opportunity. Am. J. Sociol. 101, 1628–1660. doi: 10.1086/230869

Mügge, L. M. (2012). Ethnography's contribution to newspaper analysis: Claims-making revisited. (Open Forum CES paper series 12).. Cambridge, MA: The Minda de Gunzberg Center for European Studies at Harvard University.

Riker, W. H. (1996). The strategy of rhetoric: Campaigning for the American constitution. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Rooduijn, M., Pirro, A. L. P., Halikiopoulou, D., Froio, C., Van Kessel, S., De Lange, S. L., et al. (2023). The PopuList 3.0: An Overview of Populist, Far-left and Far-right Parties in Europe.

Sagarzazu, I., and Klüver, H. (2017). Coalition governments and party competition: Political communication strategies of coalition parties. Political Science Research and Methods, 5, 333–349. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2015.56

Schäfer, C., Popa, S. A., Braun, D., and Schmitt, H. (2020). The reshaping of political conflict over Europe: from pre-Maastricht to post-‘euro crisis’. West Eur. Polit. 44, 531–557. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2019.1709754

Schattschneider, E. E. (1960). The Semisovereign people: A realist's view of democracy in America, Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, New York.

Sides, J., and Citrin, J. (2007). European opinion about immigration: the role of identities, interests and information. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 37, 477–504. doi: 10.1017/S0007123407000257

Sigelman, L., and Jr Buell, E. H. (2004). Avoidance or engagement? Issue convergence in US presidential campaigns, 1960–2000. American Journal of Political Science, 48, 650–661. doi: 10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00093.x

Stimson, J. A. (2004) Tides of consent: How public opinion shapes American politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Strom, K. (1990). A behavioral theory of competitive political parties. American journal of political science, 565–598.

Tarrow, S. (1998) Power in movement: Social movements and contentious politics. 2nd Edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Van Dalen, A. (2012). Structural Bias in cross-National Perspective: how political systems and journalism cultures influence government dominance in the news. Int. J. Press Polit. 17, 32–55. doi: 10.1177/1940161211411087

Van der Brug, W. (2004). Issue ownership and party choice. Elect. Stud. 23, 209–233. doi: 10.1016/S0261-3794(02)00061-6

Van der Brug, W., and Harteveld, E. (2021). The conditional effects of the refugee crisis on immigration attitudes and nationalism. Eur. Union Polit. 22, 227–247. doi: 10.1177/1465116520988905

Van der Brug, W., and Van Spanje, J. (2009). Immigration, Europe and the ‘new’ cultural dimension. European Journal of Political Research. 48, 309–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.00841.x

Van de Wardt, M., De Vries, C. E., and Hobolt, S. B. (2014). Exploiting the cracks: wedge issues in multiparty competition. J. Polit. 76, 986–999. doi: 10.1017/S0022381614000565

Vasilakis, C. (2018). Massive migration and elections: evidence from the refugee crisis in Greece. Int. Migr. 56, 28–43. doi: 10.1111/imig.12409

Walgrave, S., Lefevere, J., and Nuytemans, M. (2009). Issue ownership stability and change: How political parties claim and maintain issues through media appearances. Political Communication, 26, 153–172. doi: 10.1080/10584600902850718

Walgrave, S., Lefevere, J., and Tresch, A. (2012). The associative dimension of issue ownership. Public Opin. Q. 76, 771–782. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfs023

Keywords: politicization, immigration, party system change, claims analyses, VAR analyses, anti-immigration parties

Citation: Van der Brug W and Berkhout J (2024) Patterns of politicization following triggering events: the indirect effect of issue-owning challengers. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1314217. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1314217

Edited by:

Daniela Braun, Saarland University, GermanyReviewed by:

Alexia Katsanidou, GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, GermanySimon Otjes, Leiden University, Netherlands

Copyright © 2024 Van der Brug and Berkhout. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wouter Van der Brug, dy52YW5kZXJicnVnQHV2YS5ubA==

†ORCID: Wouter Van der Brug, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4117-1255

Joost Berkhout, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0527-8960

Wouter Van der Brug

Wouter Van der Brug Joost Berkhout

Joost Berkhout