- 1Risk and Vulnerability Science Centre, University of Forthare, Alice Campus, Alice, South Africa

- 2Institute for Rural Development, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa

- 3Centre of Gender and Africa Studies, University of the Free State Qwaqwa Campus, Phuthaditjhaba, South Africa

Introduction: Current frameworks of conflict resolution have shown only partial success, particularly in the context of local municipalities where conflicts persist. There is a pressing need for context-specific framework that address leadership conflicts while fostering peace.

Methods: To address the lack of progress in resolving conflicts, this study identifies major challenges undermining the assimilation and implementation of objectively informed conflict resolution strategies. A purposive sampling method was employed to select 33 respondents from the Greater Giyani Municipality. Data were collected through semistructured interviews and analyzed using statistically established matrix scoring procedures. ATLAS.ti software was utilized for data analysis.

Results: Without claiming to be exhaustive, this paper highlights examples of externalities that threaten the coexistence of the dual system of governance in South African communities, with a focus on leadership conflict and unsustainable peace. Factors contributing to conflict escalation include capacity constraints, lack of inclusive, bias, divisive decision-making and contested court decisions.

Discussion: The study underscores the importance of addressing these challenges to foster effective conflict resolution. It emphasizes the need for the scientific community to provide critical information necessary for responding effectively to these challenges.

Conclusion: To enhance conflict resolution in local municipalities, it is imperative to develop context-specific frameworks that address underlying challenges and promote sustainable peace. This requires concerted efforts from both researchers and practitioners to provide the necessary insights and strategies for resolution.

1 Introduction

South Africa employs a range of conflict resolution frameworks (CRFs) within its dual system of government, incorporating institutions such as the Council of Churches (CoCs), modern courts, and traditional courts (TCs) to address a diverse array of conflicts (Mashau and Mutshaeni, 2014; Waindim, 2019). Despite the utilization of these CRFs, there remains a persistent challenge in effectively mitigating conflicts between traditional leaders (TLs) and Ward Committees (WCs) at the local municipal level (Soyapi, 2014; Uwazie, 2018). This is why despite existing CRFs, numerous conflicts continue to recur and re-escalate. Although dealing with conflicts is generally complex, addressing conflicts between traditional and elected leaders is even more difficult than conflicts among community members (Rautenbach, 2014; Reddy, 2018). This complexity is further amplified by the emergence of a dual system of governance in local municipalities, which adds another layer to the nature of conflicts common among them (Waindim, 2019). The existence of a seemingly equal power economy between the two leadership institutions undermines the effectiveness of several CRFs, while the presence of overlapping roles increases the prevalence of conflicts (Alemie and Mandefro, 2018; Uwazie, 2018). While the Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act of 2003 sets out the legal framework for the presence and operation of TLs, including their involvement in local government affairs, the specific roles and functions of TLs at the local government level remain ill-defined (Mashau and Mutshaeni, 2014; Reddy, 2018). The resulting power dynamics arising from the overlapping of responsibilities and the lack of clearly defined roles are cited as an important factor in numerous conflicts (Soyapi, 2014). Therefore, this study argues that a customized framework will be instrumental in effectively addressing and fostering cooperation among community leaders.

Equally important to highlight is the fact that despite the general acknowledgment that the existing literature on conflict resolution (CR) offers many useful frameworks for ending conflicts and that traditional authorities continue to play a vital role in resolving conflicts (Fitzsimmons, 2006; Rukuni et al., 2012), there has been no consensus or clear-cut formula for selecting a framework that can resolve conflicts amicably in dual systems of governance (Rautenbach, 2014; Reddy, 2018). Amicable resolution of conflict not only ensures the ending of the conflict but also ensures that the process remains fair and balanced. In some cases, these frameworks have become instruments of propagating individual interest (Rautenbach, 2014; Adebayo and Oriola, 2016). In fact, with the existing frameworks failing to cope with the diverse conflicts, conflict continues to re-escalate every day. It is within this context that the need for sustainability and effectiveness of the existing frameworks become not only apparent but also imperative.

Studies by Cunningham (1996), Fashagba and Oshewolo (2014), and Rautenbach (2014) suggest that discourses and public opinion have focused on ending conflict without delving into strategies for building and sustaining peace leaving the conflicts susceptible to regenerating into another conflict. Recently the need to promote social cohesion has gained prominence. This has triggered a debate among scholars such as Shanka and Thuo (2017) who argue that effective conflict resolution cannot be confined to just ending the conflict but to sustainable peace. To rectify the perceived drawbacks, this study aimed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the weaknesses and strengths of the existing frameworks to strategically embrace and adapt elements that can effectively address the concerns while enhancing compatibility.

The endogenous CR models remain relevant not exclusively to South Africa but in other traditional societies of Africa, Asia, and Australia (Osuchukwu and Udeze, 2015; Alemie and Mandefro, 2018). For example, besides the modern courts, TCs and councils of churches were formed to collaboratively address conflicts in most rural areas of South Africa (Rautenbach, 2014; Reddy, 2018). Ideally, TCs are intended to resolve local disputes through arbitration, but the CoCs are a neo-traditional body superficially created to assist in addressing religious matters and conflicts among community leaders (Cunningham, 1996; Fisher and Rucki, 2016). No doubt, the two are therefore distinct manifestations of a genuine attempt to resolve conflicts conveniently and amicably in rural areas. Nevertheless, this collaborative approach to CR suffered a stillbirth. Therefore, if the concerns raised remain unresolved and threaten the existence and effectiveness of a dual system of governance in South Africa.

Given the emergence of the dual system of government in South Africa, it is crucial to prioritize cooperative governance through peacebuilding. However, the introduction of the dual system in municipalities has led to an increase in conflict between municipal councils in rural areas. In addition, traditional CR procedures in most societies have evolved so that democratic frameworks now dominate the CR process in rural communities. Consequently, certain aspects of previous conflict-resolution approaches have been abandoned in favor of democratic principles. The reasons for the failure of CRFs are many, but the main reason is the lack of understanding and integration of the strengths and weaknesses of the current frameworks. While it is important to acknowledge the existence of these conflicts, the focus of this study is on the identification and possible adaptation of elements of the existing frameworks within democratic systems of governance.

2 Methodology

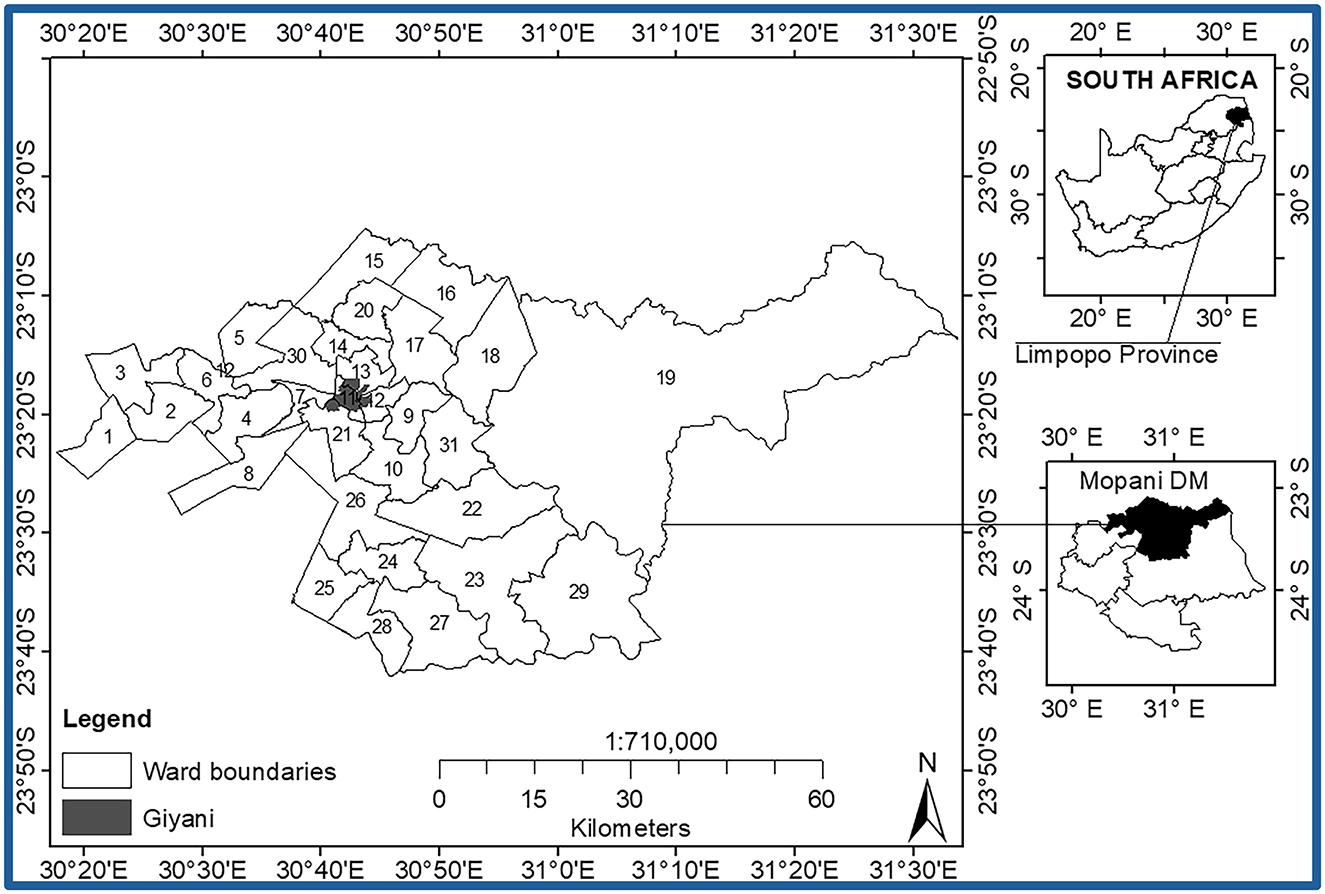

The present study covered the rural part of GGM in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Giyani is situated about 185 km from Polokwane (formerly Pietersburg), 100 km from Thohoyandou and 550 km from Pretoria. The municipality covers an area of 2967.27 km2 with only one semi-urban area, Giyani, which belongs to the B category of South African municipalities (Great Giyani Municiplality, 2018). It was established under the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996 and the Municipality Demarcation Act 1998 (South African Local Government Association, 2013) and is one of five municipalities in the Mopani District. The municipality is divided into 31 wards and has 62 councilors (Greater Giyani Municipality). It has 10 traditional authority areas consisting of 93 villages, all inhabited by Tsonga. The boundaries of the wards and the boundaries of the traditional communities do not coincide.

2.1 Sampling procedure

The data collection methodology for the case study conducted in GGM was a purposive selection of participants representing youth (six), women (six), WC chairpersons (six), prominent people (six), police representatives (three) and chairpersons of traditional authorities (six). Respondents' years of experience in CR varied from <1 year to more than seven years to collect relevant data from all age groups (Mosera and Korstjens, 2017). Twenty participants had secondary education and only four key informants had tertiary education. Nine participants had no formal education but could read and write. The sample was drawn from two wards of the 31 wards in the municipality.

2.2 Data collection methods

Data were collected using semi-structured investigative approaches that were developed by Adeoye-Olatunde and Olenik (2021). Questions were tailored to the group being interviewed so that the researcher could gather information on the experiences of youth, women, community committee chairpersons, police representatives and traditional authority chairpersons (Creswell, 2013; Adeoye-Olatunde and Olenik, 2021). The consolidated matrix scoring was used to identify the typical conflicts between TLs and WCs in Greater Giyani Municipality (Figure 1). The key informants, under the guidance of the researcher, created an assessment of what they thought were the most common conflicts in the area. The respondents' subsequent reflections on how to assess the consequences of conflicts against the established criteria were quite insightful. They discussed among themselves with examples of why a certain score should be given. The scoring was first recorded on the flipcharts. Regular scores were calculated from the various FGDs to indicate the severity of the consequence of conflict.

2.3 Analysis of the data

After the completion of the interviews, the recorded conversations were transcribed and imported into ATLAS ti.22 for coding (Scales, 2013). By utilizing ATLAS ti.22 for coding, the researchers were able to identify key themes and patterns within the transcribed data. This coding process allowed for the identification of significant topics of discussion and the extraction of pertinent findings (Sucharew and Macaluso, 2019). Subsequently, network diagrams were electronically generated to visually present the results (Wright and Bouffard, 2016). The use of network diagrams as a means of presenting the data proved to be an effective method for communicating the consolidated findings of the study (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2012). These diagrams provided a visual representation of the data, facilitating the easy illustration of the key findings by the researchers (Wright and Bouffard, 2016).

3 Results and discussion

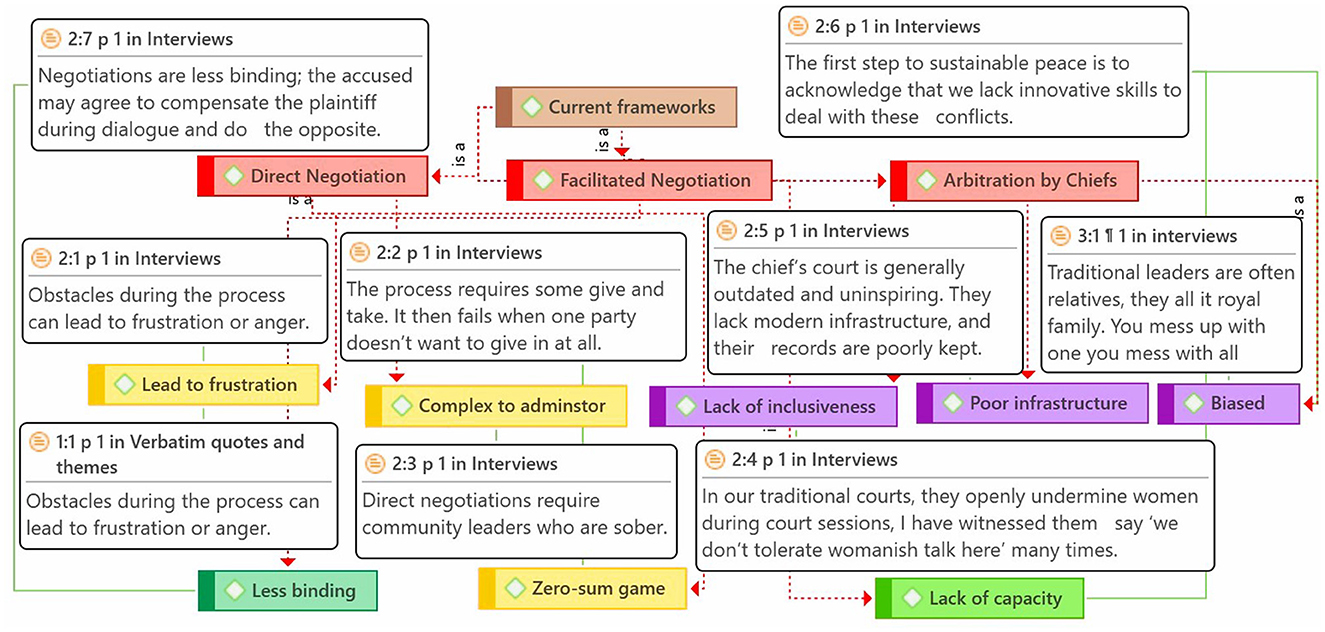

This present study presents the weaknesses and strengths of various CRFs and how they were employed to resolve conflicts between TLs and WCS (Figure 1). Key informant interviews and FGDs expressed that there are multiple frameworks employed by community leaders in Greater Giyani Municipality. The results revealed that direct negotiation facilitated negotiation, arbitration, and adjudication as popular frameworks.

Figure 2 below shows the ATLAS.ti 8 table of major strengths and weaknesses of the existing CRFs. Respondents indicated that all civil matters involving community leaders are expected to be resolved through the Chief's Court or the CoCs. However, the victim will first look to the wrongdoer for satisfaction by direct negotiation. Should this fail, then the matter proceeds to the local magistrate court, and if necessary, through the hierarchy to the chief's court. Unlike the other TCs in Africa like the Tswana Chiefs Court which handles criminal cases (Schapera, 1995), participants in Giyani indicated that bulky criminal cases were handled by the magistrate court.

Figure 2. Flowchart illustrating the shortcomings of the current frameworks identified by survey respondents.

3.1 Chiefs as arbitrators in conflict resolution

One of the key findings from this study is the utilization of chiefs as peace brokers between the elected and TLs in CR. Respondents revealed that within the Greater Giyani Municipality, chiefs, operating within TCs, directly engage as arbitrators for conflicts. Also, chiefs were considered to possess extensive experience and a deep understanding of cultural dynamics and norms. This cultural sensitivity as suggested by scholars such as Shanka and Thuo (2017) and Albin (2019) enables them to approach conflicts with a nuanced perspective and ensure that the resolution process is respectful of the community's cultural values and traditions. However, key informants expressed concerns about bias and lack of inclusiveness, suggesting that the chief's independence and evenhandedness may be compromised due to their social hierarchies and linkages. Youth and women, whose experiences and voices are often in stark contrast to those of other social segments, tended to agree on values related to inclusion. Youth felt marginalized as traditional structures often do not take their input into account, and women also felt that cultural norms relegated them to a passive role in conflict resolution, eclipsing their unique perspectives and needs. This led to a divergence from groups that prioritize the status quo and hierarchy. These results also align with Osuchukwu and Udeze (2015) who contend that women were excluded in endogenous systems of CR. One of the representatives of the youth retorted:

“Traditional leaders are often reluctant to give young people and women the opportunity to bring their perspective to conflict resolution. They often invoke the concept of the ‘royal family', creating a culture in which disrupting a TL's stance is seen as a challenge to the whole. This tendency is particularly evident in the Chief's Court, where chiefs tend to support each other.”

A close analysis of the above verbatim quote confirms that TLs in the Chiefs' Court often face challenges stemming from their exclusionary practices and social affiliations (Figure 2). The situation raises concerns that the integrity of TCs is not guaranteed due to social hierarchies, ties and the exclusion of voices from the community. Despite these concerns, there is a possibility of convergence. Recognizing the unique contributions of youth and women is essential to developing more inclusive and sustainable conflict resolution methods. Proposals to integrate women and youth into the TC system and to train court members in conflict resolution have been suggested as positive measures to improve capacity. Nevertheless, the practical implementation and acceptance of these recommendations within the TC structure may face obstacles due to deeply ingrained cultural norms and prevailing power dynamics.

Participants also expressed concern about the current state of infrastructure of endogenous court facilities, such as courthouses and roads (Figure 2). They argue that the lack of modern infrastructure not only hinders the effectiveness of these court systems but also lacks their commitment to ending conflict. It was also found that some members of the TCs appointed by the chief based on their proximity lacked acumen and relevant knowledge on CR to perform their duties effectively. These findings are in line with Soyapi (2014) who opined that justice exercised by TCs is not healthy because there is no legal representation. Therefore, tailor-made capacity-building workshops would equip them with the necessary skills and understanding of CR. In addition, the creation of knowledge-sharing platforms with practitioners from the legal profession would facilitate the exchange of valuable insights and expertise and further enhance the capacity of TCs to resolve conflicts.

3.2 Direct negotiation by the conflicting parties

The other strategy that emerged in the study and is used by the parties to resolve conflicts in the communities is face-to-face discussions. According to interviewees during KIs, the approach is preferred when both parties are influential players in a conflict situation. For example, an aggrieved TL can consider having direct conversations with WC to resolve their differences because they all have influence. A practical example given by interviewees is that in one of the case study villages, a WC who had disagreed with the village head over the recruitment of youths in a community project chose to talk face-to-face. One of the highlighted advantages of this approach is that it signals the actors' willingness to manage the conflict and can foster the development of trust. Considering that direct negotiations can lead to a win-win result, obligations under direct negotiations are more likely to be implemented than obligations imposed by a third party. However, negotiations may turn sour if players fail to act rationally (Figure 2), and ultimately lead parties to argue with one another, aggravating tensions between disputants. For example, informants recounted that a failed negotiation over-allocation of resources usually resulted in the re-escalation of cultural conflicts (Figure 2). These findings agree with other studies by Alfredson and Cungu (2008) the process is frustrating and requires players who can manage their emotions.

3.3 Facilitated negotiations by the CoCs

The interviews conducted revealed that some matters are reported to the CoCs, the pastor, who also serves as the chairperson of the council, acts as the principal negotiator and invites the aggrieved parties to negotiate. The negotiator asks the complainant to state the value of the compensation he or she is seeking from the accused. The CoCs were given as an example of a CR structure with facilitated negotiations. This form of facilitated negotiation is not suitable for parties with unequal power and resources. Where power and resources are unequal, the process could lead to an unfair settlement as the party with less power and resources could be overburdened and vulnerable to bias. The KIs also pointed out that the facilitated negotiation process is often lengthy due to the involvement of various stakeholders, including district committees, CoCs and formal institutions. These findings are in line with the conclusions of Vettori (2015), who emphasizes that the facilitated negotiation process is known to be laborious and time-consuming.

An important finding is that, in most cases, conflict parties usually lack honesty during negotiations as they seek to maximize their gains from the process. As a result, the process is marred by claims and counterclaims among parties in conflict. This suggests that the decision to participate in facilitated negotiations may be disregarded if the parties feel that they will gain less from it. Consequently, the success of these negotiations depends heavily on the cooperation of both parties. These findings support the claims of scholars such as Radford (2001) and Omisore and Abiodun (2014) who argue that the facilitated negotiation process may fail if the parties involved do not find common ground.

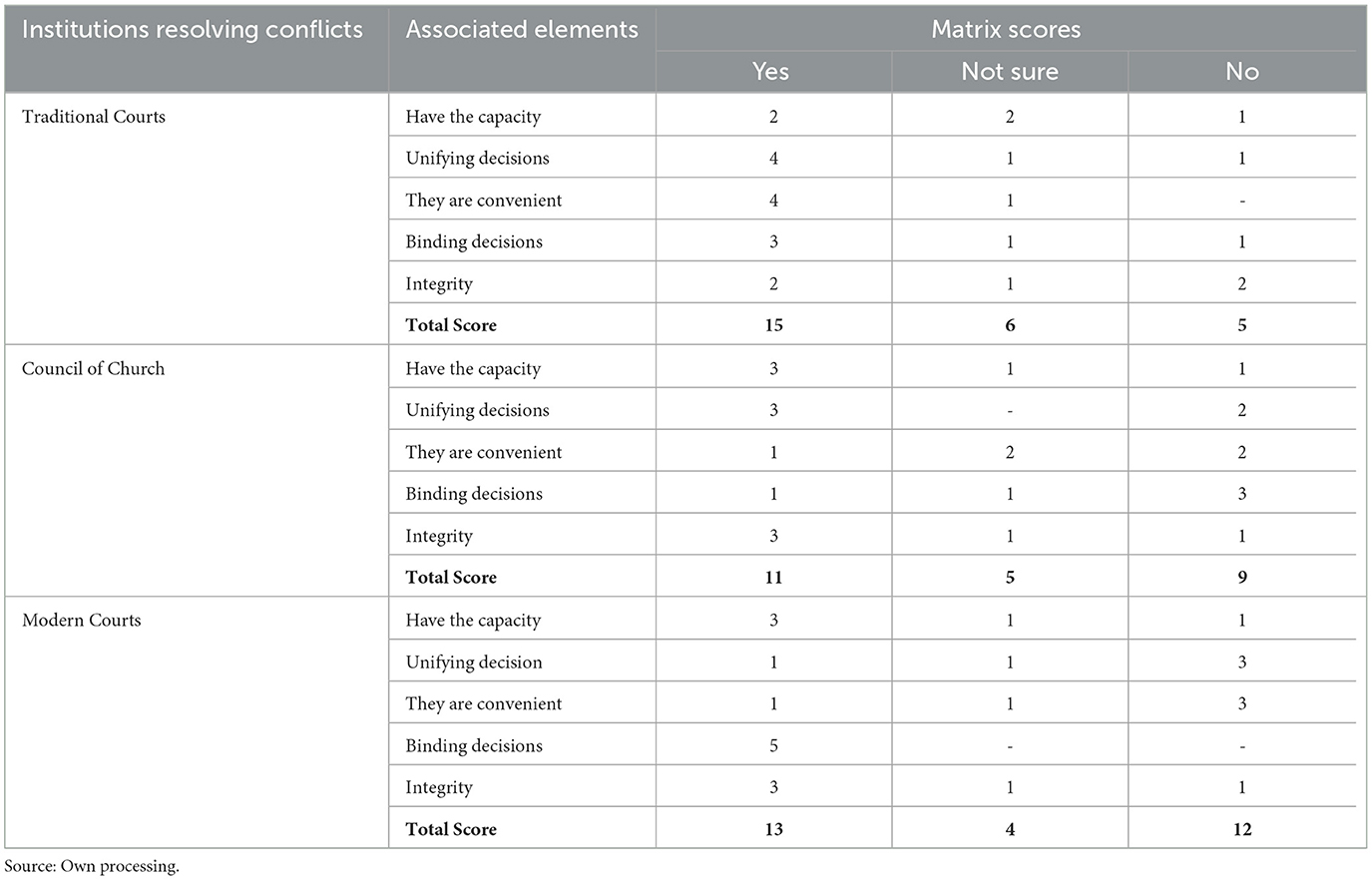

The results of the matrix score collated from the five focus groups provide some insights into the preferred peace structures. It is worth noting that TCs obtained the highest score of 15, indicating that they are the most preferred peace structure among the participants. However, a closer examination of the individual components of the score reveals some weaknesses. The TCs scored the lowest in integrity and capacity, both receiving a score of 2, which raises concerns about the trustworthiness and effectiveness of these courts. On the positive side, aspects of convenience and unifying decisions received higher scores of 4, indicating that TCs are perceived as accessible and capable of fostering cohesion. This observation is consistent with the perspective of Mashau and Mutshaeni (2014), who argue that TCs tend to make decisions that contribute to greater unity within communities. While these scores highlight the perception that TCs are accessible and promote social cohesion, it's crucial to note that these perceptions can vary widely based on specific cultural contexts and individual experiences. In contrast, modern courts obtained the second-highest score of 13. While their overall score is lower than TCs, they scored better on integrity and capacity, each with 3 points. This suggests that participants consider modern courts to be more reliable and capable than TCs. Disturbingly, however, modern courts scored the lowest out of 1 on both convenience and unifying decisions. This suggests that they may not be perceived as accessible or able to promote consensus among communities. Conversely, participants assigned the highest score of 5 to binding decisions, suggesting a prevailing belief in the capacity of modern courts to robustly enforce their judgments. This alignment is corroborated by Rukuni et al. (2012) and Alemie and Mandefro (2018), who contend that the binding nature of modern court decisions underscores their efficacy.

The CoCs received the lowest score of 11 among the three peace structures. The CoCs also received an average score of 3 on integrity and capacity. However, convenience and binding decisions received the lowest score of 1, indicating that participants do not view the CoCs as instrumentally useful in resolving conflicts. Unifying decisions also received only a score of 3, indicating that participants do not believe the CoCs can effectively unify communities. Overall, the analysis of the matrix items reveals some strengths and weaknesses of the preferred peace structures. These results suggest that further study and evaluation of each peace structure is needed to determine the most appropriate solution for promoting peace and justice in each context.

3.4 Ranking of the current CR structures

Table 1 shows public opinion on the ability of current CR institutions to resolve conflicts between TLs and WCs in Giyani municipality. Five interrelated characteristics of an effective CR system were identified from the results based on participant feedback. Characteristics that are interrelated and grouped under one name.

3.5 Benefits of a complementarity approach to addressing each system's limitations

Because of the important role that the traditional leadership institution plays in resolving conflicts (Rautenbach, 2014; Reddy, 2018), there is a need to preserve and strengthen these traditional structures. It is crucial to mention that advocating for TCs should not be misconstrued as disregarding the relevance of modern courts in these communities. Instead, both institutions should work hand in hand, complementing each other's functions. Traditional courts, being local and easily accessible, allow individuals to resolve minor legal issues closer to their communities (Mashau and Mutshaeni, 2014; Alemie and Mandefro, 2018; Uwazie, 2018). This reduces the burden on magistrate courts, which can prioritize more complex cases. The complementary approach ensures that justice is more accessible to leadership institutions regardless of the nature or severity of their legal matters. Due to their simplified procedures, TCs can typically resolve cases more quickly than magistrate courts (Rukuni et al., 2012; Waindim, 2019). By referring appropriate cases to TCs, the overall judicial system can expedite the resolution of less complex matters, thus alleviating the backlog in magistrate courts and promoting efficiency in the justice system. In a nutshell, the adaptation of TCs allows for the complementarity between TCs and magistrates. The collaboration promotes legal pluralism, which acknowledges and respects multiple legal systems existing within society. This, in turn, enhances social cohesion by recognizing diverse perspectives and values.

3.6 Adapting TCs in ending conflicts and building sustainable peace

Similarities in the chief's arbitration and magistrate courts reflected gradual ideological diffusion through government efforts to transform traditional leadership institutions. This study argues that moving toward building sustainable peace in local municipalities requires incorporating elements from other frameworks of CR into the TC system. For example, democratic societies prioritize the protection of human rights. Adapting TCs in line with democratic principles helps ensure that the rights of individuals are respected and protected during the court process (Fashagba and Oshewolo, 2014; Uwazie, 2018). This includes rights such as the right to a fair trial and the right to be heard.

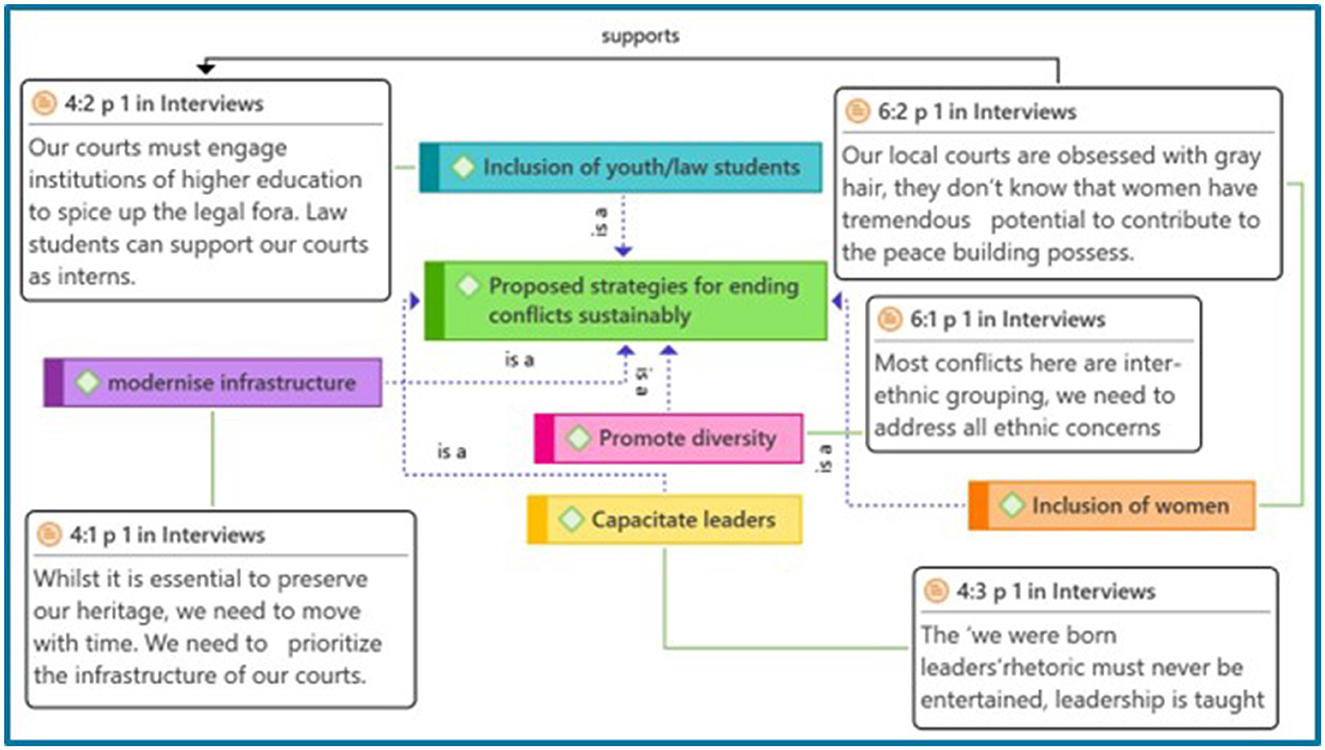

Representatives of women also voiced their apprehensions regarding the exclusion of women and youth from the TC proceedings, emphasizing the imperative of including representatives from these groups in the process of CR. As a result, the inclusion of youth and women in dispute settlement structures has the potential to create a forum for consensus building, that is based on open discussion and the exchange of information on CR matters (Figure 3). Soyapi (2014) and Osuchukwu and Udeze (2015) add that a deep reflection on the sheer number of youths alone justifies the inclusion and consideration of youth in CR processes.

Figure 3. Flowchart illustrating elements identified by survey respondents that can be incorporated into the current frameworks.

This study has also brought to light the fact that TC systems are lacking in cultural diversity. This is particularly surprising considering the multicultural nature of many local municipalities in South Africa. Consequently, there is an urgent need to promote cultural diversity and tolerance within these TCs. Taking this recommendation seriously is of utmost importance as it will effectively address potential issues of unfairness, discrimination, and biases within the system.

It has also become clear that some members of the TCs lack sufficient acumen and capacity to resolve complex conflicts involving other leaders. To address this weakness, one viable solution is to assign law students to serve as interns in the courts (Figure 3). This approach would bring new perspectives and strengthen the court's ability to effectively dispense justice. Problems with overlapping roles have also proven to be an obstacle to the complementary function of CR structures. One step in the right direction is to eliminate overlapping jurisdictions to create a court system that commands respect and makes enforceable decisions. Streamlining jurisdictional boundaries is essential to give the court's decisions the seriousness they need.

Finally, the commendable move to modernize TC facilities goes a long way toward enhancing the credibility of the TC system. By providing modern and appropriate facilities, the court can create a more conducive environment for dispute resolution, thereby increasing confidence in the entire process (Figure 3). However, it is also important to ensure that modernization efforts respect the original design and historical significance of the traditional institutions. Any changes or updates should be done in a way that preserves the integrity and authenticity of the site. Involving local communities, indigenous groups, and stakeholders in decision-making processes related to traditional institutions can help strike a balance between modernizing facilities and preserving cultural value. Their perspectives and voices should be heard and respected, as they have intimate knowledge and connections to the cultural heritage at stake. In short, adopting certain elements and integrating positive recommendations into the TC system is essential to effectively address underlying problems and contribute to real and lasting peace in communities.

4 Conclusion

The results of this study highlight the similarities between the chief's arbitration and magistrate courts, indicating a gradual diffusion of ideologies through government initiatives to promote a dual system of governance. This article concludes that the traditional CR structures were less effective due to the emergence of more formal and well-resourced structures that tended to overshadow most traditional practices that were used to mitigate and resolve conflicts in Giyani Municipality. Regardless of the need for change, TCs are still preferred and remain integral to local communities in South Africa. This underscores the importance of the need to strengthen their structures and efficiency within these communities. However, any attempts to reform TCs should consider the local context and the importance of preserving cultural identity to ensure a balance between modernization and cultural preservation for a more effective and inclusive legal system.

This study has shown that dealing with conflicts between traditional and elected leaders is complex and that existing frameworks are not designed to deal with inter-institutional conflicts. This complexity appears to be exacerbated by the failure to resolve the core values of a dual governance system (integration of customary law and democratic principles). The argument, then, is that traditional and modern legal systems can be adapted to develop an appropriate response to institutional conflict. Considering these and other considerations, current frameworks must move from a de facto dichotomy (impunity or trial) to multiple concepts of justice and reconciliation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethical Clearance Committee of the University of Venda. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. GM: Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adebayo, A. A., and Oriola, B. (2016). Nexus of land conflicts and rural-urban migration in south-west Nigeria: implications for national development in Nigeria. Nigerian J. Rural Sociol. 16, 70–78.

Adeoye-Olatunde, O. A., and Olenik, N. L. (2021). Research and scholarly methods: semi-structured interviews. J. Am. College Clin. Pharm. 4, 1257–1367. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1441

Albin, C. (2019). Negotiating complex conflicts. Global Policy 10, 55–60. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12693

Alemie, A., and Mandefro, H. (2018). Roles of indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms for maintaining social solidarity and strengthening communities in AlefaDistrict, North West of Ethiopia. J. Ind. Soc. Dev. 7, 1–21.

Alfredson, T., and Cungu, A. (2008). Negotiation Theory and Practice A Review of the Literature. Maryland: FAO.

Cunningham, T. F. (1996). Conflict Resolution Strategies and the Church: The Church's Role as an Agent of Social Change in the Polemical Conflict in South Africa. Pretoria: University of Pretoria.

Fashagba, J., and Oshewolo, S. (2014). Peace and governance in Africa. Covenant Univ. J. Politics Int. Affairs. 2, 45–57.

Fisher, J., and Rucki, K. (2016). Re-conceptualizing the science of sustainability: a dynamical systems approach to understanding the nexus of conflict, development and the environment. Sust. Dev. 1, 267–275. doi: 10.1002/sd.1656

Fitzsimmons, A. (2006). Forum shopping: a practitioner's perspective. The Int. Assoc. Study Insurance Econ. 1, 314–322. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.gpp.2510076

Great Giyani Municiplality (2018). Integrated Development Plan 2019/2020. Giyani: Greater Giyani Municipality.

Mashau, T. S., and Mutshaeni, H. N. (2014). The relationship between traditional leaders and rural local municipalities in South Africa: with special reference to legislations governing local government. Kamla-Raj 12, 219–225. doi: 10.1080/0972639X.2014.11886702

Mosera, A., and Korstjens, I. (2017). Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. part 1: introduction. Eur. J. Gen. Practice 23, 271–273. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375093

Omisore, B. O., and Abiodun, A. R. (2014). Organizational conflicts: causes, effects and remedies. Int. J. Acad. Res. Econ. Manage. Sci. 3, 118–136. doi: 10.6007/IJAREMS/v3-i6/1351

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Leech, N. L., and Collins, K. M. (2012). Qualitative analysis techniques for the review of the literature. Qual. Rep. 17:56.

Osuchukwu, N. P., and Udeze, N. S. (2015). Promoting women's participation in conflict resolution in nigeria: information accessibility. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Hum. Res. 3, 431–439.

Radford, M. F. (2001). Advantages and disadvantages of mediation in probate, trust, and guardianship matters. Pepperdine Dispute Resol. Law J. 1, 241–257.

Rautenbach, C. (2014). Traditional courts as alternative dispute resolution (ADR) –mechanisms in South Africa. Int. J. Div. Org. Commun. Nations 1, 288–329.

Reddy, P. S. (2018). Evolving local government in post-conflict South Africa: Where to? Local Econ. J. Local Econ. Policy Unit 33, 710–725. doi: 10.1177/0269094218809079

Rukuni, T., Machingambi, Z., Musingafi, M. C., and Kaseke, K. E. (2012). The role of traditional leadership in conflict resolution and peace building in Zimbabwean rural communities: the case of Bikita district. Publ. Policy Admin. Res. 5, 75–79.

Scales, B. J. (2013). Qualitative analysis of student assignments: A practical look at ATLAS.ti. Ref. Serv. Rev. 41, 134–147.

Shanka, E. B., and Thuo, M. (2017). Conflict management and resolution strategies between teachers and school leaders in primary schools of Wolaita Zone. Ethiopia 8, 63–74.

South African Local Government Association (2013). SALGA Annual Report 2012-2013. Pretoria: South Africa.

Soyapi, C. B. (2014). Regulating traditional justice in south africa: a comparative analysis of selected aspects of the traditional court bill. PER 17, 1441–1469. doi: 10.4314/pelj.v17i4.07

Sucharew, H., and Macaluso, M. (2019). Methods for research evidence synthesis: The scoping review approach. J. Hosp. Med. 14, 416–418.

Uwazie, E. E. (2018). Peace and Conflict Resolution in Africa: Lessons and Opportunities, 1st Edn. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Vettori, S. (2015). Mandatory mediation: An obstacle to access to justice? Afr. Hum. Rights Law J. 15, 355–377. doi: 10.17159/1996-2096/2015/v15n2a6

Waindim, J. N. (2019). Traditional Methods of Conflict Resolution: The Kom Experience. London: ACCORD.

Keywords: conflict resolution, framework, leadership disputes, sustainable peace, traditional courts

Citation: Muchaku S and Magaiza G (2024) The struggle within dual systems of government: dealing with conflict between traditional leaders and ward councilors in the greater Giyani Municipality in South Africa. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1311178. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1311178

Received: 09 October 2023; Accepted: 26 February 2024;

Published: 20 March 2024.

Edited by:

Clinton Sarker Bennett, State University of New York at New Paltz, United StatesReviewed by:

Dylan Mangani, Nelson Mandela University, South AfricaHlekani Kabiti, Walter Sisulu University, South Africa

Copyright © 2024 Muchaku and Magaiza. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shadreck Muchaku, TXVjaGFrdS5TJiN4MDAwNDA7dWZzLmFjLnph

Shadreck Muchaku

Shadreck Muchaku Grey Magaiza

Grey Magaiza