94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 17 April 2024

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1302686

This article is part of the Research TopicAgents of Political Socialization in the 21st CenturyView all 7 articles

Although the effects of elections and measures of direct democracy on policy outcomes have been well researched, their indirect “educative value” has received less attention, particularly in relation to political engagement of young people. This study examined the activating effect of the national elections in Germany (2009), Czech Republic (2010), and Sweden (2014) on young voters’ political engagement. Young voters (Germany: N = 388; Czech Republic: N = 196, and Sweden: N = 246) were surveyed several months before (T1), shortly after (T2), and several months after (T3) the respective national elections. For all three countries, the results revealed significant increases in political engagement during the election period, followed by significant declines after the election. The post-election declines were smaller compared to the election increases, suggesting a persistence of elections’ activating effects. With the exception of German young adults who were less engaged or first-time voters and showed higher increases in engagement during the election period, there were few interindividual differences. The findings suggest that major political events such as national elections can have activating effects on youth’s political engagement. They support the idea of the socializing value of election participation and of late adolescence and young adulthood as a window of opportunity for reaching young voters during politicized times.

Reports of growing political apathy and disengagement as well as an increasing susceptibility toward populist and anti-democratic voices are viewed with concern – especially when they involve young people (Smets, 2012; Chevalier, 2019). Youth is considered a formative period for the development of political attitudes and behaviors that persist later in life (Shani et al., 2020). According to the impressionable years hypothesis (Sears and Levy, 2003; Dinas, 2010), it is a time in which political awareness and understanding increases, while young people still search for a sense of identity and might, thus, be particularly susceptible to contextual influences. Accordingly, finding ways of activating young people during these formative years could facilitate a formation of lasting political engagement habits.

While the term youth is often linked to the period of adolescence (i.e., 10–18 years; American Psychological Association, 2002), it might also refer to a period somewhat later in life, namely the time of young or emerging adulthood (i.e., 18–29 years; Arnett, 2000). Traditional research in the context of the impressionable years hypothesis stresses the significance of both phases1 for political development (Sears and Levy, 2003).

Of the many factors that shape young people’s political development, experiences in proximal contexts, such as home, school, or the peer group, have gained particular attention (Neundorf and Smets, 2017). Research has shown that young people encounter politics at school (Miklikowska et al., 2019; Noack and Eckstein, 2023) and adopt political attitudes from parents (Miklikowska, 2016; Legget-James et al., 2023) or other family members (Eckstein et al., 2018). Yet, in line with contextual models of human development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), more distal macro-contexts such as societal events (e.g., wars, political upheavals, scandals) also play a role. In this regard, national elections are one example of macro-contextual events that can have socializing effects.

While national elections and measures of direct democracy (e.g., ballot initiatives) have been found to affect policy outcomes (e.g., governmental reforms) and minority rights (Bowler et al., 1998), their indirect “educative value” has received less attention (but see Tolbert et al., 2003; Franklin, 2004; Franklin and Hobolt, 2011), particularly in relation to political engagement of young people. In line with the assumptions of the impressionable years hypothesis, research suggests that the impact of political events is particularly strong for youth (Dinas, 2013; Ghitza et al., 2023). Indeed, Sears and Valentino (1997) showed that youth’s partisan attitudes were shaped by the 1980 presidential campaign. If national elections stimulate youth political engagement, it would suggest that political development does not proceed linearly, reflecting primarily intrinsic maturational processes (Hyman, 1959; Hess and Torney, 1967), but that it sometimes occurs in bursts and in response to external political events (Sears and Valentino, 1997). This would mean that major political events can have a socializing value and that late adolescence and young adulthood is a window of opportunity for reaching young people during politicized times to foster their engagement habits. It would also bolster the case for participatory models of democracy seeking to facilitate government responsiveness to citizen demands (Citrin, 1996; Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 2001).

There are few empirical studies examining the relation between national elections and political engagement of young people, particularly with longitudinal designs. Drawing on three samples of young voters from Germany, Czech Republic, and Sweden it was therefore the goal of the present study to examine whether national elections with their politized climate and the opportunity to actively participate in the electoral process translate into the formation of longer-lasting engagement habits among youth in these country contexts. In particular, we examined whether elections had facilitating and enduring effects on young voters’ political engagement (beyond voting) over the course of an election year. We also examined for whom these effects were the most pronounced.

Reinforced by an influx of information, media coverage, or discussions with friends or family members, current events can contribute to an increase of youth’s political awareness and engagement. Accordingly, research showed that events like the war in Vietnam and the civil rights movement (Markus, 1979; Erikson and Stoker, 2011), the Watergate scandal (Dinas, 2013), or the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York on September 11, 2001 (Gimpel et al., 2003) shaped youth’s political attitudes and behaviors. While most research to date is based on US samples, there is also empirical evidence from other national contexts. Mobilized by developments in the wake of the German reunification in 1989/90, for example, large-scale surveys reported a significant increase in political interest among young people in both the Eastern and Western part of Germany (Friedrich and Förster, 1997). Political activation of young people in response to societal events takes place at any time and could more recently be observed in global movements such as Black Lives Matter (Titley, 2021) or Fridays For Future (Parth et al., 2020).

National elections represent another example of major societal events, but unlike wars, political scandals, or upheavals, they are predictable and are usually held at regular intervals. It has been theorized that elections can have an activating effect on youth and are, for example, assumed to socialize voting behaviors. Research suggests that it takes several successive electoral experiences to lock down the habit of voting (Franklin, 2004). Focusing on conventional political behaviors, one study showed that German adolescents’ participation was higher during a campaign period than in a period when no election was held (Kuhn and Schmid, 2002). Unfortunately, this study did not have a follow up after the election to test whether this effect persisted. Beyond political behaviors, campaign effects have also been discussed in relation to changes in political interest and attitudes (Banducci and Stevens, 2015). One longitudinal study reported significant socialization gains in adolescents’ partisan attitudes, such as the strength of partisan affect, over the course of the 1980 US presidential election (Sears and Valentino, 1997). These gains could be observed primarily for the period of the election campaign, when political issues were more salient, than in the aftermath of the event. In line with the impressionable years hypothesis underlining an enhanced susceptibility to political influences in adolescence and young adulthood (Sears and Levy, 2003), these gains were found to be more pronounced among adolescents than among their parents. Moreover, socialization gains were primarily observed for topics relevant to the political campaign and among adolescents who were exposed to high levels of political information via media and political discussions at home (Valentino and Sears, 1998). On a similar note, high-stakes and tight elections were shown to attract more voters, and in particular young voters, than elections with a foreseeable outcome (Smets and Neundorf, 2014). The type of election also matters – elections to the European Parliament were found to suppress the engagement of first-time voters as they may be too distant or be considered less relevant and, in consequence, create a habit of non-voting (Franklin and Hobolt, 2011). Finally, research provides support for the socializing effects of mock elections, showing that participation in election simulations at school increases youth’s political interest and engagement (Coffey et al., 2011; Borge, 2017; Öhrvall and Oskarsson, 2020; Lundberg, 2024).

These findings suggest that elections can have educational value and can catalyze youth’s political development by drawing attention to political issues, providing opportunities for commitment and reducing the cost of engagement. As such, it can be the act of voting itself that leads to changes in political attentiveness and engagement. Participating in one of democracy’s fundamental tenets could strengthen political-efficacy and trust in political processes, thereby contributing to the establishment of lasting engagement habits (Tolbert et al., 2003). Except for casting one’s vote, a generally enhanced salience and visibility of political topics during election periods might further facilitate engagement. Indeed, research suggests that discussions in social networks stimulate adolescents to pay more attention to the news (McDevitt and Chaffee, 2002; McDevitt and Kiousis, 2004; Miklikowska et al., 2022) and that increased news consumption contributes to the development of political interest (Kruikemeier and Shehata, 2017) and engagement (Valentino and Sears, 1998; Holt et al., 2013; but see Šerek and Umemura, 2015). At the same time, these findings indicate that political development is not a continuous process; instead, it occurs periodically and in response to external political events (Sears and Valentino, 1997). This would mean that event-sparked fluctuations in young people’s engagement present a window of opportunity for reaching young voters during politicized times to facilitate the formation of their engagement habits.

Political events do not affect all young people to a similar extent. Due to consolidated attitudes or previous experiences young people may be more or less receptive to contextual influences. For example, the politicized and often polarized time of an election campaign could especially lead to the mobilization of ‘standby citizens’––young people who are politically interested but not active (Amnå and Ekman, 2014). These young people who consider politics important, could be motivated by the fact that elections offer opportunities for change in government and political leadership. Consequently, they might step out and get active by engaging in political conversations with family and friends, visiting campaign events, or supporting candidates during the campaign. After the election event, they might go back to a standby-mode and reduce their level of active engagement more than young people who were already very active before.

Besides the general level of political activity, the effects of elections might also differ depending on youth’s electoral choice. Experiencing that the party or candidate one has voted for won might contribute to the feeling that one’s vote mattered. Consequently, young voters’ confidence and motivation to engage in political processes may be strengthened. In line with this reasoning, previous research showed that supporting a winning party or candidate boosts satisfaction with democracy as well as trust in politics (Bowler and Donovan, 2002; Plescia et al., 2021). Consequently, due to a higher satisfaction with the result, the activating effect of an election might then be of longer duration.

Finally, the effects of elections might differ depending on previous voting experiences. Being eligible to vote for the first time has a particular meaning and therefore elections may have a stronger mobilization effect among first-time voters than among more experienced young voters. There is empirical support for such a “first-time voter boost” (Konzelmann et al., 2012). Accordingly, several studies showed that young people who could vote for the first time cast their ballot more often than young people who already had a chance to vote (Bhatti et al., 2012; Konzelmann et al., 2012). At the same time, first-time voters are often less decided toward a particular party or candidate (Fournier et al., 2004; Ha et al., 2013) and, accordingly, more susceptible to campaign influences than experienced young voters (Aalberg and Jenssen, 2007; Ohme et al., 2018). Hence, to decide on a vote, first-time voters may show higher levels of information seeking and engagement during the campaign period than more experienced young voters.

The present study is based on data from Germany, Czech Republic, and Sweden, which allow to longitudinally examine youth’s political engagement in the context of a national election. All three countries are characterized by a multiparty system. Elections to the national government are held every 4 years, whereby all citizens of legal age (18 years) are entitled to vote. Apart from these similarities, the included national contexts also reflect the diversity within Europe. As such, the study includes countries with varying levels of overall political trust and voter turnout, which were reported to be higher Sweden and Germany than in the Czech Republic (OECD, 2019; Memoli, 2020).

In addition, further country-specifics relating to the direct context of the examined national elections should be taken into account. Germany. The year of data collection (2009) was characterized by several political events. Besides elections to the national parliament (September 2009), elections to the European Parliament (May 2009) and local/regional elections were held (for Thuringia in August 2009). However, despite the density of opportunities for casting a vote, the national election was considered the most significant, which was also reflected in the overall turnout rates (Tenscher, 2011). The broader climate was not particularly politicized as the campaign periods were generally described as quiet and low-key throughout the year, which also applies to the campaign for the primary national election (Tenscher, 2011). Czech Republic. The year of data collection (2010) was preceded by a period of political turmoil as the national government lost a non-confidence vote in March 2009, in the middle of the Czech presidency of the EU, and a snap election initially scheduled for October 2009 was postponed by the Constitutional Court. The 2010 parliamentary election was mostly perceived as a standard left–right competition on issues such as state budget and public debt, social welfare, health care, or economic policy (Linek, 2012). The election held at the end of May 2010 represented the most salient political event of the year, followed by less prominent local elections in October 2010. Sweden. The year of the data collection (2014) was a period of political stability and few major political events. Although the election was held prior to the increase of refugees arriving in Europe in 2015, the political discourse was slowly changing in relation to the rise of the radical right party (Sweden Democrats) that attracted 12.9% votes in the election held on the 14th of September. Even though the party had little influence on the politics during that time period, it did contribute to making immigration issues more salient on the political agenda thereafter.

The present study aimed at better understanding changes in young people’s political engagement over the course of an election year. Building on longitudinal data, it followed three samples of young voters several months before (T1), shortly after (T2), and approximately 6 months after (T3) the German, Czech, and Swedish national elections in 2009, 2010, and 2014, respectively. At the core of the study are three research questions: (1) Do periods of national elections have a facilitating effect on young people’s political engagement? (2) Does this effect persist for several months after the election? And (3) does this effect vary based on young people’s political experiences (i.e., politically active vs. not in the past; first-time voter vs. experienced voter) and electoral choice (i.e., voted for a winning party that later formed the government vs. voted for another party)? In doing so, the study focused on young people who voted in the respective election.2

Drawing on previous findings concerning the strength and consistency of partisan attitudes (Sears and Valentino, 1997), we expected increases in political engagement from T1 to T2, reflecting the activating effect of the upcoming election (research question 1). We further expected that changes in political engagement during the pre-election period were followed by relatively smaller declines from T2-T3, indicating a persistence of elections’ activating effect (research question 2). We also hypothesized that the activating effect of the election (changes from T1-T2) would be stronger among young voters who had been politically less active in the past and among first-time voters than among youth who were generally more politically active or already voted in a national election, respectively (Konzelmann et al., 2012; Ohme et al., 2018). While we assumed that changes in political engagement during the post-election period (T2-T3) would not differ according to young people’s political experience, we expected young people who voted for a winning party to experience a stronger and more enduring activating effect of the event (research question 3).

We used longitudinal data from German university students, collected 6 months before (T1, N = 871), immediately after (few days up to 2 weeks, T2, N = 434), and 6 months after (T3, N = 458) the German national election in 2009. The data were gathered at a medium-sized University located in Thuringia, Germany. At T1 students from various majors, such as economics, humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences, participated, representing the diverse student body quite well. Students were contacted in lectures and seminars and asked to fill out a paper-pencil questionnaire on different political topics. Since it would have been extremely difficult to contact each participant at the end of the semester in their changing courses, the following two assessments were conducted via an online survey. As an incentive for participation, students had the chance to win portable music players and gift certificates. All students were eligible to vote.

The present study focused on a subsample of participants who voted at T2 (90% of the T2 response rate). Accordingly, the analyzed sample included N = 388 participants (Mage = 21.4 years, SDage = 2.8, age rage: 17–42 years) with more female (n = 258, 66.5%) than male participants. Most of the participants came from higher socio-economic backgrounds (i.e., parents with college-bound education; n = 245, 63.1%), which is characteristic for university students due to the relatively strong association between parental education and children’s educational success in Germany (Klemm, 2016).

Data came from a larger five-wave longitudinal study of Czech high-school students. We analyzed data collected 4 months before (T1, N = 479), immediately after (about 2 weeks, T2, N = 276), and 6 months after (T3, N = 210) the 2010 national election. Participants were recruited by a professional company in the South Moravian region using a stratified multistage random sampling (districts, schools, classes). E-mail addresses were obtained from 1,000 young people, out of which 657 confirmed their willingness to participate in the study and 479 participated in the first wave. Within 1 year, participants were repeatedly asked via e-mail to complete online questionnaires on different topics. Participants who attended all waves of data collection could win gift certificates.

This study focused on a subsample of participants who were older than 18 and voted at T2 (78% of the T2 response rate). Thus, the analyzed sample included N = 196 participants (Mage = 18.4 years, SDage = 0.6, age rage: 18–20 years) with more female (n = 133, 67.9%) than male participants. Most of the participants were from academically-oriented grammar schools (n = 111, 56.6%). About one quarter (n = 47, 24.0%) lived in a big city (with about 400,000 inhabitants), while the rest lived in smaller towns and villages.

We used longitudinal data from Swedish high-school students, collected 6 months before (T1, N = 524), immediately after (2 weeks, T2, N = 268), and 6 months after (T3, N = 583) the Swedish national election in 2014. This study uses the three last waves of longitudinal data of a larger project on youth development. The data were collected in the Swedish seventh largest city of 137,000 inhabitants. The city resembles the national average on income, unemployment, and ethnic diversity (Statistics Sweden, 2016). The data were gathered in 10 schools selected from a range of neighborhoods with different ethnic and social backgrounds. Every class received yearly a small payment of 100 EUR for participation. The data collection took place during school hours and trained research assistants administered questionnaires.

The present study focused on a subsample of participants who voted at T2 (92% of those who indicated that they were eligible to vote at T1 and 86% of the T2 response rate). Accordingly, the analyzed sample included N = 246 participants (n = 136, 55.5% female, Mage = 17.4, SD = 0.5, age rage: 17–18 years). The participants in the analytical sample came from average socio-economic backgrounds (MSES = 3.5, SD = 0.8, range: 1–5) and reported slightly above average parental education levels (Meducation = 4.1, SD = 0.9, range 1–5). Table 1 summarizes important sample characteristics according to country.

Germany. Attentiveness was operationalized as young people’s general interest in politics and the frequency of discussions about political issues with family and peers. Political interest was measured with a single item (“Overall, how interested are you in politics?”) rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 = not interested at all to 6 = very interested. The frequency of political discussions was captured by four items (e.g., “How often do you discuss politics and society with your mother”; Schmid, 2001) rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 = hardly ever to 7 = daily. Reliabilities of the scales were good αT1–T3 = 0.78–0.84. Czech Republic. Attentiveness was operationalized in terms of young people’s frequency of discussions about social and political issues with family and peers. Two items (“How often did you talk about social and political issues with your parents in the last month?” and “How often did you talk about social and political issues with your friends or classmates in the last month?”), were rated on a Likert scale ranging from 0 = never to 4 = daily or almost daily. Correlations between the two items from T1 to T3 were 0.32, 0.41, and 0.56, respectively. There was no measure of political interest in the Czech dataset. Sweden. Attentiveness was operationalized as young people’s general interest in politics and societal issues. It was measured with two items (“How interested are you in politics?” and “How interested are you in what is going on in society?) rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 = not interested at all to 5 = very interested. Correlations between the two items from T1 to T3 were 0.65, 0.77, and 0.74, respectively. There was no measure of political discussions available in the Swedish dataset.

Germany. Intentions were measured with four items (Schmid, 2001). Participants were asked whether they would take part in the following institutionalized forms of engagement (working for a political party, attending a political discussion or campaign event, supporting a political candidate during a campaign, contacting politicians) rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 = would definitely not take part to 6 = would definitely take part. The scale’s reliabilities were good: αT1–T3 = 0.74–0.77. Czech Republic. Intentions were measured with two items: “I feel that I should regularly go to the municipal elections” and “I feel that I should regularly go to national (parliamentary) elections.” Participants expressed their agreement using a Likert scale from 1 = definitely not applies to 4 = definitely applies. Correlations between the two items from T1 to T3 were 0.62, 0.50, and 0.66, respectively. Sweden. There was no measure of intentions available in the Swedish dataset.

Germany. Participants were asked whether they have been actively engaged in any of the four political activities (see description of intention) during the preceding 12 months (0 = no, 1 = yes). A count variable was created, reflecting the number of previous activities. Czech Republic. Participants were asked about their engagement in 11 political activities in the past 12 months (0 = no, 1 = yes), for example “signing a petition,” “attending a demonstration,” or “contacting a politician or a state official.” A count variable was created. Sweden. Participants were asked whether they have done any of the following 10 political activities in the past 12 months, for example: “signed a petition,” “attended a meeting concerned with political or societal issues,” “contacted a politician or public official” (1 = no, 2 = yes, occasionally, 3 = yes, several times).

In all three countries, a dummy-coded variable compared young people who voted for a party that later formed the government (i.e., winning parties; 1) with young people who voted for parties that did not form the government (0).

Germany. First-time voters (1) who were allowed to vote for the first time in 2009 were contrasted with experienced voters (0) who were already old enough to participate in previous elections. Czech Republic and Sweden. All participants from the Czech and Swedish sample were first-time voters.

Germany. Gender (0 = male, 1 = female), parental education (0 = parents without college-bound education, 1 = parents with college-bound education), and age (in years) were included as covariates. Czech Republic. Included covariates were gender (0 = male, 1 = female) and high school track (0 = vocational, 1 = academically-oriented), which is closely associated with family socio-economic status in the Czech Republic (Smith et al., 2016) All participants were from the same cohort and, hence, were of the same age. Sweden. Gender (0 = male, 1 = female), mean parental education (scale from 1 = less than 9 years of compulsory education to 5 = university degree), and subjective financial situation [an average of two items: “What are your family finances like?” rated on a scale from 1 = My parents always complain that they do not have enough money to 4 = My parents never complain about being short of money and “If you want things that cost a lot of money (e.g., a computer), can your parents afford to buy them?” rated on a scale from 1 = absolutely not to 5 = yes, absolutely] were included as covariates. All students were from the same cohort and, hence, were of the same age.

The analytical approach was the same for all three countries. Structural equation modeling (SEM) with latent variables was applied using Mplus 8.6 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2018). For all outcome variables assessed with more than two indicators, we reduced the number of indicators by aggregating them into two parcels (i.e., item averages). An item-to-construct balance procedure, combining items based on their factor loadings, was used (Little et al., 2002). This allowed for decreasing model complexity and improving the sample size to model size ratio, given the studies’ rather small samples (Little et al., 2013). The items were averaged for each parcel (Little et al., 2013; Rioux et al., 2020) and the measurement errors of parallel parcels were allowed to covary over time (Marsh et al., 1992).

To examine intraindividual change in young people’s political engagement, Latent True Change modeling was adopted (LTC; Steyer et al., 1997). Individual scores were decomposed into latent initial states (with means fixed to zero and variances to one) and latent change factors that represent mean-level changes between measurement occasions. Latent change scores can be considered similar to simple change scores obtained as a difference between individual scores from two consecutive measurement occasions. However, their advantage is that they provide a more accurate estimate of change because measurement error is explicitly modeled. To meaningfully interpret mean value differences across time, strict measurement invariance was assumed. Thus, measurement invariance across time was established for political engagement as part of the model specification.

To answer research questions 1 and 2, a latent change model was conducted. Change scores represent mean-level changes in political engagement between adjacent measurement occasions. The initial state factor (State Factor T1) reflects young people’s mean levels of political engagement at T1 before the election. The change between T1 and T2 (Change Score T2-T1) can be interpreted as the activating effect of the election supposed by research question 1. At the same time, change factors between T2 and T3 (Change Score T3-T2) show the persistence of the activating effects after the election addressed by research question 2. Significant mean levels of the change scores describe the average amount of intraindividual change in young people’s political engagement, while significant variances indicate interindividual differences in these trajectories. Both changes in political engagement across time (i.e., T1-T2 and T2-T3) were estimated separately within one model.

To test research question 3, the latent changes in political engagement were predicted by past political behaviors, electoral choice, and first-time voting. The effects of each predictor were tested separately to account for their unique contribution. All models controlled for gender and SES (and age in the German sample) as covariates. Model fit was evaluated based on the χ2-statistic and goodness-of-fit indices (CFI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤0.06, SRMR ≤0.08; Hu and Bentler, 1999).

To examine missing values, Little’s MCAR tests (Little, 1988) including all study variables were employed using participants who voted at T2 as the target sample. For the German sample, the results of the test were not significant (χ2 (44) = 48.94, p = 0.281), suggesting that data were missing at random. Non-significant results were also obtained for the Czech Republic (χ2 (56) = 63.47, p = 0.230). In the Swedish sample, the results of the test were significant (χ2 (20) = 32.94, p = 0.034), suggesting that the data were not missing completely at random. For all three countries, the missingness was addressed within the model estimation by using a full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation, which is better than pairwise or listwise deletion (Woods et al., 2023).

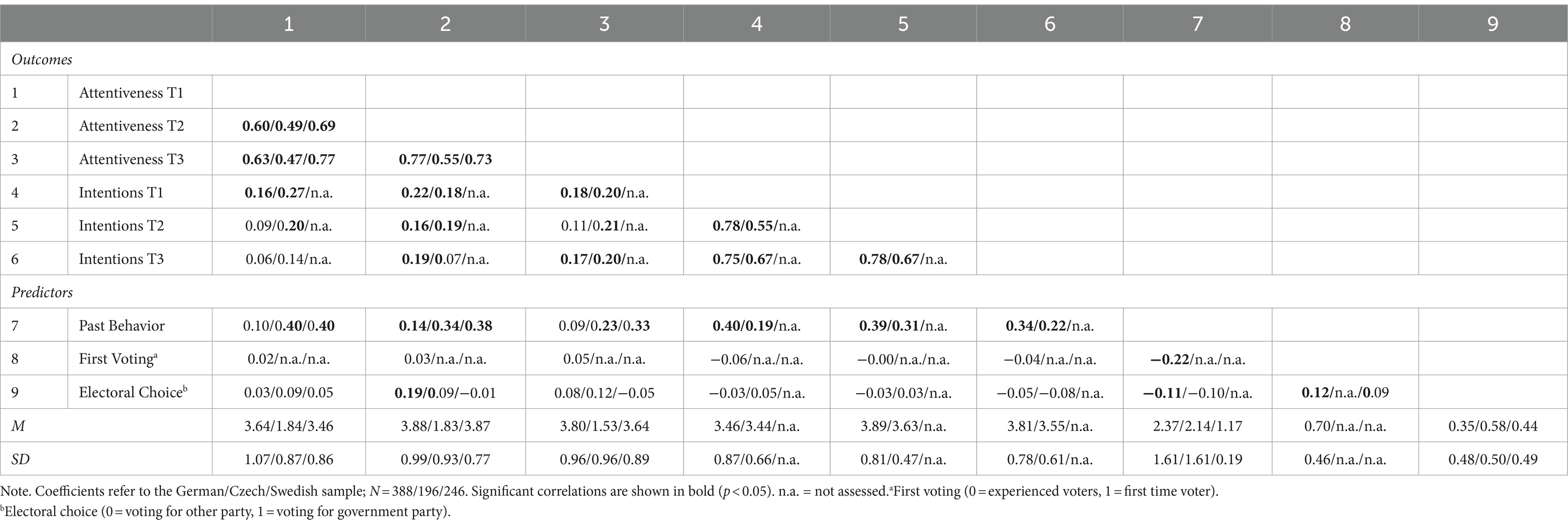

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for all study variables according to country are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of outcome and predictor variables in the German/ Czech/ and Swedish sample.

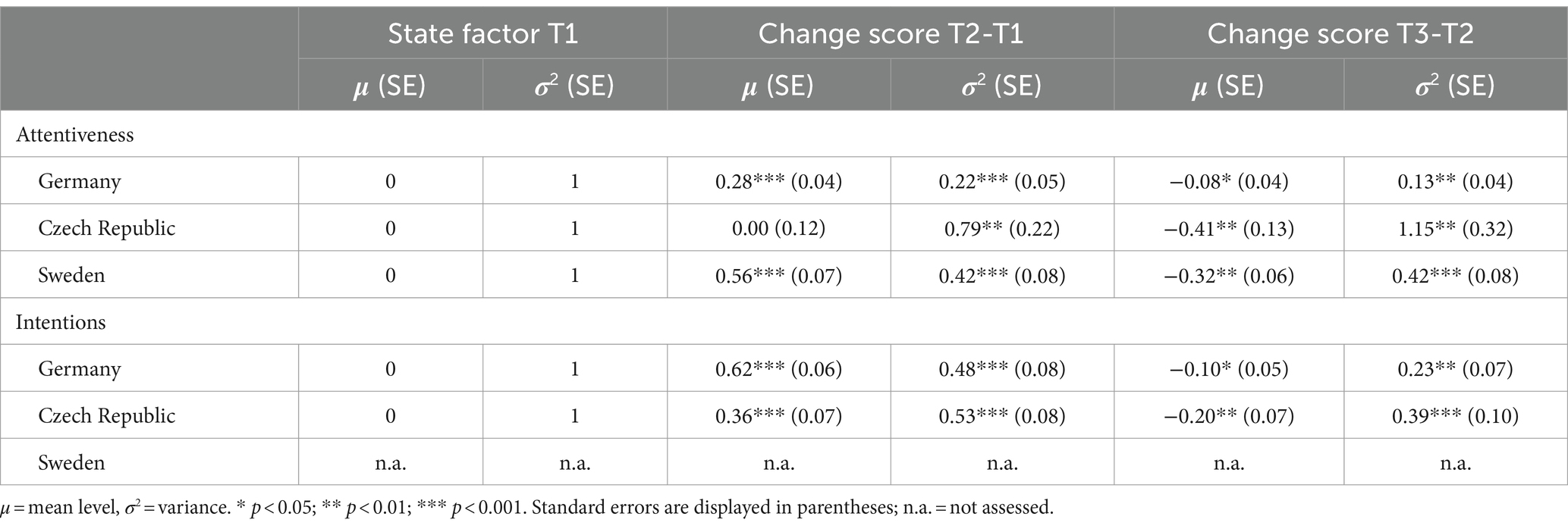

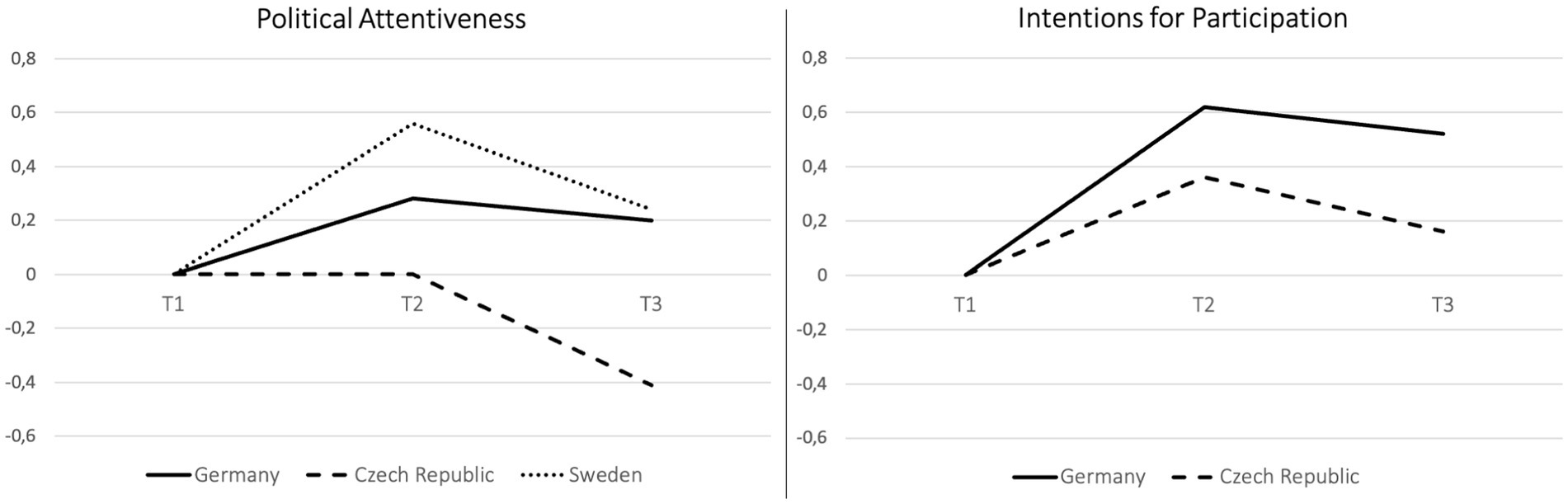

The LTC models for political attentiveness (χ2 = 24.37 (11), p = 0.011, CFI = 0.989, RMSEA = 0.056, SRMR =. 046) and intentions for political participation (χ2 = 13.49 (11), p = 0.262, CFI =0.997, RMSEA = 0.024, SRMR =. 045) yielded a good model fit. Parameter estimates are summarized in Table 3. For both measures, the estimated mean levels of change scores were significant and in the expected direction. The positive mean levels for Change Scores T2-T1 indicate that political attentiveness and intentions for political participation increased over the course of the election. The negative mean level estimates for the Change Scores T3-T2, in contrast, suggest a decrease during the post-election period. Single Wald chi-square test of parameter equalities was conducted to compare both change scores (i.e., absolute values). For political attentiveness (χ2 = 23.22 (1), p < 0.001) and intentions for political participation (χ2 = 79.51 (1), p < 0.001) the tests revealed a significant difference suggesting that the decrease between T2 and T3 was smaller than the increase between T1 and T2. The results further revealed significant variation around the Change Scores T2-T1 and T3-T2, pointing to significant interindividual differences in each rate of change. Figure 1 provides a graphical depiction of the mean level changes in young people’s political engagement across time.

Table 3. Means and variances of the initial state and change scores for political attentiveness and intentions for participation.

Figure 1. Mean level changes in political attentiveness and intentions for participation between T1 and T3. Mean level changes in political attentiveness and intentions for participation are shown according to country. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3; NGER = 388; NCR = 196; NSW = 246.

Both LTC models for political attentiveness (χ2 = 23.64 (10), p = 0.009, CFI = 0.948, RMSEA = 0.083, SRMR =. 053) and intentions for political participation (χ2 = 15.23 (11), p = 0.172, CFI =0.989, RMSEA = 0.044, SRMR = 0.092) showed an acceptable model fit. Table 3 summarizes means and variances of the initial status at T1 and the two change scores. Similarly to Germany, intention for participation significantly increased between T1 and T2, which was followed by a significant decrease between T2 and T3 (see Table 3). A comparison of change scores (Single Wald chi-square test of parameter equalities) revealed that the decrease between T2 and T3 was smaller than the increase between T1 and T2 (χ2 = 4.95 (1), p = 0.026). For political attentiveness, in contrast to Germany, there was no significant mean change between T1 and T2. A significant decrease followed between T2 and T3. Again, significant variances in Change Scores T2-T1 and T3-T2 pointed to interindividual differences in changes across time. Figure 1 provides a graphical depiction of the mean level changes in young people’s political engagement across time.

The LTC model with political attentiveness as outcome yielded an acceptable model fit after replacing strict invariance with strong invariance (χ2 = 21.22 (7), p = 0.004, CFI = 0.986, RMSEA = 0.091, SRMR = 0.046). Similarly to Germany, the results revealed a significant increase in political attentiveness between T1 and T2, which was followed by a significant decrease between T2 and T3 (see Table 3). Parameter comparisons revealed that the T2-T3 decrease was significantly smaller than the T1-T2 increase (χ2 = 21.190 (1), p < 0.001). Significant variances in change scores pointed to interindividual differences in changes across time. Figure 1 provides a graphical depiction of the mean level changes in young people’s political engagement across time.

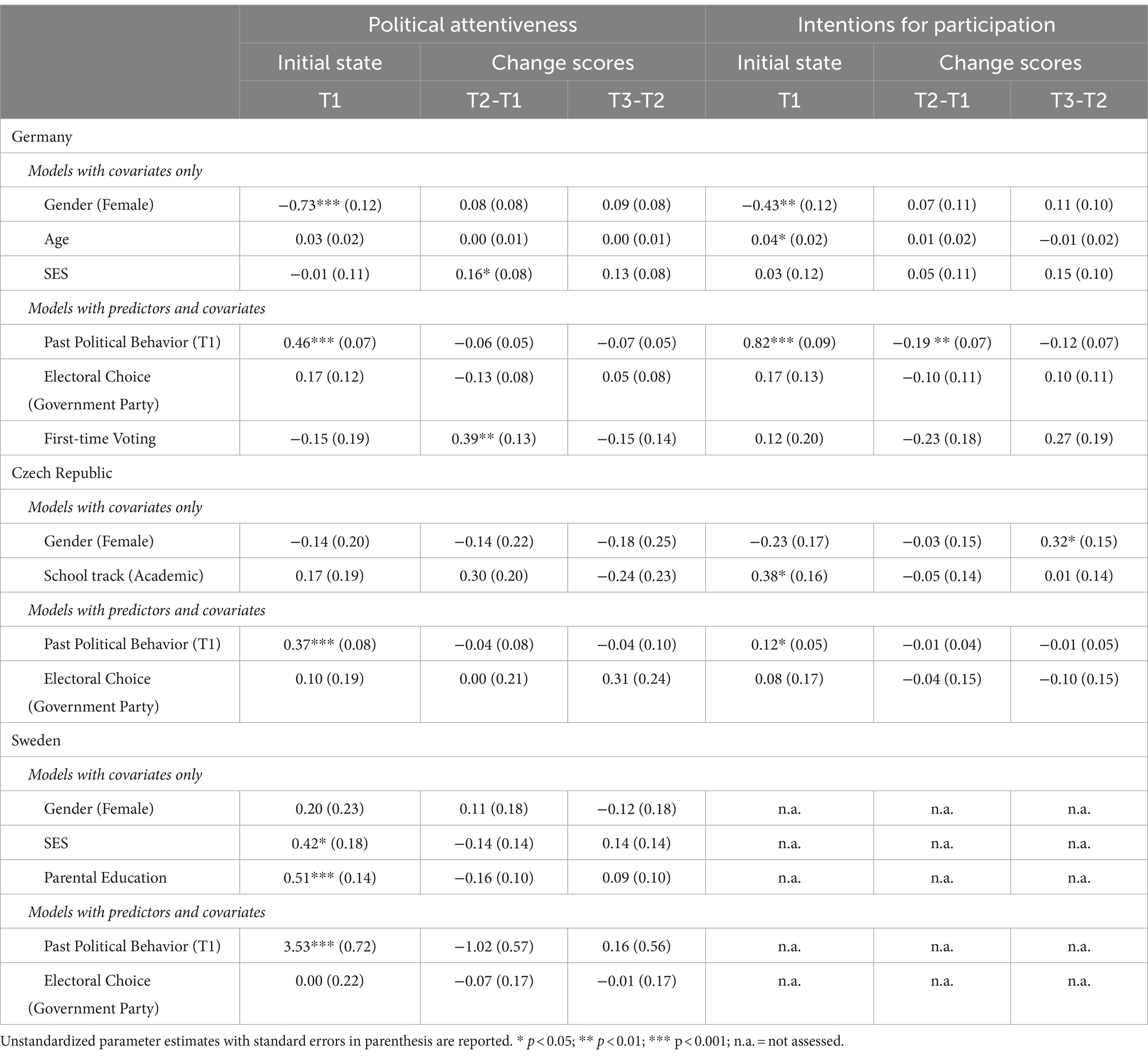

Indicators of past political behaviors, electoral choice, and first-time voting were added to the analyses to predict the State Factors T1 as well as the Change Scores T2-T1, and the Change Scores T3-T2 of both political engagement measures. To account for its unique contribution, each predictor variable was considered separately. Yet, the overall result pattern was also replicated when all predictors were examined simultaneously in one model. A complete summary of the model estimates is provided in Table 4.

Table 4. Results for predicting state levels and change scores of political attentiveness and intentions for participation.

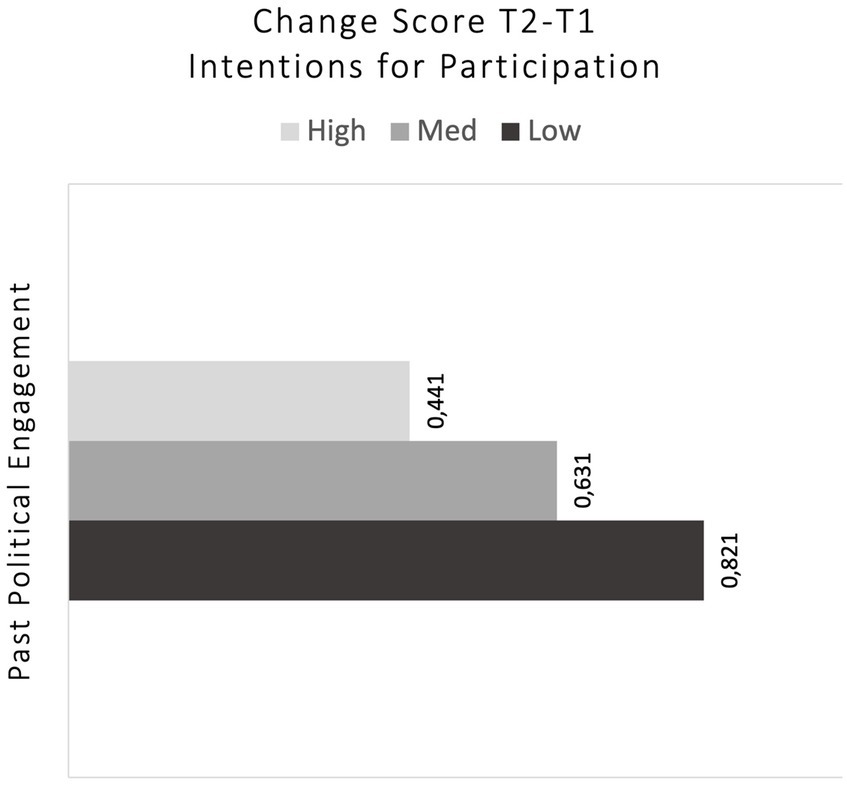

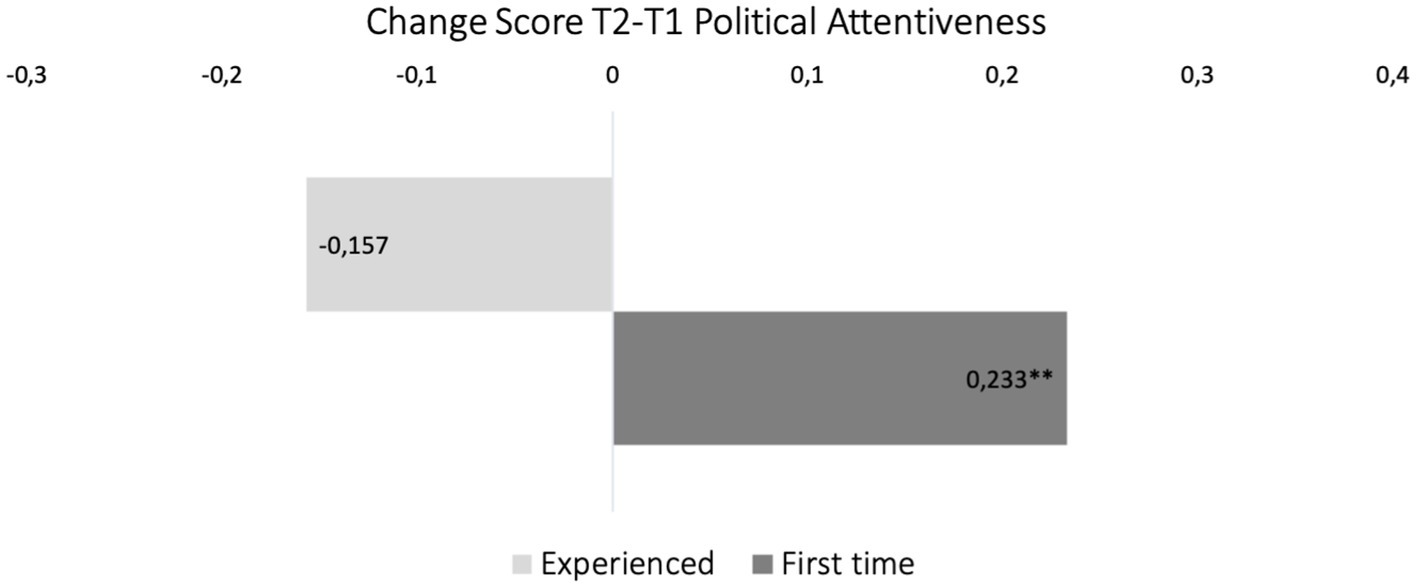

The results showed that past political behaviors were positively related to political attentiveness and intentions for political participation at T1. The findings further revealed that past political behaviors had a significant effect on the Change Score T2-T1 of intentions for political participation. Accordingly, lower levels of past political engagement were associated with a higher increase in intentions for political participation between T1 and T2. To illustrate the latter effect, Change Scores T2-T1 were computed for low, medium, and high levels of past behaviors (i.e., participants involved in zero, one, or two activities, respectively; see Figure 2). Overall, change Scores T2-T1 were smaller for highly active than for less active youth. Contrary to expectations, past political behaviors did not predict changes in political attentiveness between T1 and T2, nor the change between T2 and T3 for either of the two engagement measures. For electoral choice, no effects on changes in political attentiveness and intentions for political participation (neither for Change Score T2-T1 nor Change Score T3-T2) were found. Being a first-time voter was not associated with political attentiveness or intentions for political participation at T1. However, first-time voters had a stronger increase in political attentiveness between T1 and T2 (see Table 4). As depicted in Figure 3, the Change Score T2-T1 was only significant among first-time voters, but not among experienced voters. As the Change Score T2-T1 was controlled for covariates including age, this effect was more than a mere age-effect. First-time voting experience was, however, unrelated to changes in intentions for political participation. There were also no effects on changes between T2 and T3 for both engagement measures.

Figure 2. Change scores T2-T1 of behavioral intentions for high, medium, and low levels of past political engagement (German sample). Estimated means are displayed, controlled for age, gender, and SES effects. High (=2), medium (=1), and low (=0) engagement; N = 388.

Figure 3. Change scores T2-T1 of political attentiveness for first-time and experienced voters (German sample). Estimated means are displayed, controlled for age, gender, and SES effects; ** p < 0.01; N = 388.

Since all participants of the Czech sample were first-time voters, only past political behaviors and electoral choice were included as predictor variables. Again, each predictor was considered separately. Yet, the overall result pattern could be replicated when all predictors were examined simultaneously in one model.

The results showed that past political behaviors were related to higher levels of political attentiveness and intentions for participation at T1, while no effects were found for electoral choice at T1. However, neither past political behaviors nor electoral choice predicted changes in intentions for participation or political attentiveness between T1-T2 and T2-T3 (see Table 4 for a complete summary of parameter estimates).

Similar to the Czech sample, all Swedish participants were first-time voters and therefore only past political behaviors and electoral choice were included (one by one) as predictor variables (again the result pattern could also be replicated in a simultaneous model). Past political behaviors were related to higher levels of political attentiveness, while no effect for electoral choice was found. Neither past political behaviors nor electoral choice predicted changes in political attentiveness between T1-T2 as well as T2-T3 (see Table 4, for a complete summary of parameter estimates).

The results pointed to significant associations with gender at T1. Male youth reported higher levels of political attentiveness and intentions for political participation at T1 than female youth. Associations with age and SES were less consistent: older participants had somewhat higher intentions for participation at T1, while SES positively predicted an increase in political attentiveness between T1 and T2. All other covariate effects were not significant.

Significant covariate effects emerged for school track and gender. More precisely, intentions for participation at T1 were higher among young people from academically-oriented than vocational schools and the decrease in intention for participation was less pronounced among female than among male participants. Gender and SES had no effect on political attentiveness at any time point.

Both indicators of SES (financial resources and parental education) were related to higher political attentiveness at T1, while no effects on changes across time were found. There was also no indication for gender-specific patterns.

Across democratic societies, voting represents the most common form of political participation. Since major elections are usually accompanied by an influx of political information and political discourse – both in the public domain, but also in private conversations among family members or friends – their activating effects have been discussed (e.g., Sears and Valentino, 1997; Franklin, 2004; Dinas, 2010; Franklin and Hobolt, 2011), but scarcely tested longitudinally among young people. Yet, particularly for young people, who often approach traditional political processes and actors with a greater distance (Chevalier, 2019), elections might offer a window of opportunity to get in contact with party and governmental politics and to become politically involved. To examine potential event-driven changes in political engagement, the present study followed three samples of young voters over the course of an election year in Germany, Czech Republic, and Sweden.

Regarding research questions 1 and 2, the results showed that German, Czech, and Swedish youth’s political engagement (i.e., political attentiveness and intentions for participation) significantly increased during the time before and shortly after the election (T1 – T2). This result is in line with previous research showing greater affective expression and crystallization of youth’s partisan attitudes following a 1980 presidential campaign (Sears and Valentino, 1997), an increased political knowledge of adults following the exposure to ballot initiatives (Tolbert et al., 2003), and higher conventional political participation during a campaign period than in a period when no election was held (Kuhn and Schmid, 2002). Moreover, German, Czech, and Swedish youth’s political engagement (i.e., political attentiveness and intentions for participation) significantly decreased during the months following the elections (T2 – T3). This decrease was less pronounced than the increase during the pre-election period (i.e., between T1 and T2) for both measures of political engagement.

This pattern of results suggests that periods of national elections culminating in electoral participation foster young people’s political engagement and that parts of this activating effect persist in the post-election period. This underscores the general importance of the macro-context for political development and, in particular, the socializing value of major political events. As such, periods of national elections can promote youth’s political development by drawing attention to political issues, providing opportunities for commitment, and facilitating opportunities for engagement. It further provides hope that even if young people are initially indifferent, their participation in the electoral process can activate an engagement in politics. As a result, voting in national elections may boost political activity among young people and it is possible that they will maintain a heightened interest after the election, given that late adolescence and young adulthood are formative periods for political attitudes and behaviors that persist later in life (Shani et al., 2020). Promoting political activities among young people should therefore be more actively pursued by educational institutions and programs (Miklikowska et al., 2022). Schools and universities could better integrate curricula initiatives or service programs that encourage students to participate in national elections (Mo et al., 2022) and that support teachers to foster political discussions in the classroom (Eckstein and Noack, 2014; Miklikowska et al., 2022). Moreover, this pattern of findings also offers some support for participatory models of governance as a way to strengthen democracy (Citrin, 1996; Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 2001) and for the initiatives of lowering the voting age as way to start political socialization earlier, thereby boosting youth engagement (Wagner et al., 2012). Finally, this pattern of findings shows the importance of including the data collections around major political events to minimize the risk of omitting important fluctuations in the developmental outcomes and overestimating the importance of intrinsic maturational processes (e.g., cognitive development).

The only exception in this pattern of results was political attentiveness (i.e., discussions) in the Czech Republic, which did not change from T1 to T2 and decreased significantly after the election compared to the pre-election period. When interpreting this finding it should be taken into account that the T1 data collection in the Czech sample took place 4 months prior to the election (compared to 6 months prior in Germany and Sweden). Moreover, the situation of the Czech election in 2010 was relatively specific because it was held after a period of political crisis that lasted for more than 1 year. The election was initially scheduled for October 2009 but postponed to May 2010 by the Constitutional Court. Accordingly, a substantial portion of the event-driven mobilization might have already taken place within the Czech sample, as information flows and public discussions tend to increase especially during the weeks leading up to the election (Hayes and Lawless, 2015). This early effect is more likely for attentiveness than intentions for participation, for which increased opportunities to become active surge rapidly just before the election. The timing of the first point of data collection in the Czech sample could also explain the higher decrease in political attentiveness during the post-election period. Since T1 already caught most of the election’s activating effect on attentiveness, the de-activating trend between T2 and T3 was reflected more prominently in the data.

Although political attentiveness and intentions for participation decreased in the aftermath of the election, for the most part they remained higher when compared to their respective pre-election levels in all three samples. This persistence might be due to the activating experience of casting a vote at a major election, especially to first time voters for whom elections may hold a special meaning. However, this persistence is also likely to be explained by the politicized context not only during the campaign but also post-election with intensified media coverages and discussions in social environments that prompt youth’s political awareness and engagement (Valentino and Sears, 1998; Miklikowska et al., 2022). Consequently, controversies about the designation of political positions or negotiations between political parties remain salient within the public discourse and the media for several weeks.

As part of research question 3, three behavioral indicators were added to predict political engagement to gain a better understanding of interindividual differences in changes across time: past political behaviors, electoral choice, and being a first-time voter. Past political behaviors were found to predict changes in German young voters’ intentions for future engagement during the campaign period (i.e., T1 – T2) but were not related to changes in political attentiveness. One possible explanation might be the conceptual proximity between the indicators. Politicized times, such as campaign periods, often provide a range of opportunities for political participation, for example at campaign-related events. The increased visibility of political activities might then primarily reach young people who have not been active so far but could well imagine getting out of their standby-mode and to take action. This might have contributed to the finding that less active youth reported higher increases in intentions for participation during the pre-election (campaign) period than their more active peers. Applied to the micro-context of schools it could for example also be shown that an encouraging climate motivated particularly less active youth to become politically engaged (e.g., Eckstein and Noack, 2016). At the same time, it should be noted that methodological artefacts, such as ceiling effects, cannot be ruled out. Moreover, this effect occurred only in Germany but not the Czech Republic where the activation during the pre-election period was unrelated to youth’s previous level of political engagement. As noted above, the Czech election took place after a prolonged political crisis and it is possible that the mobilizing effect of the pre-election period operates differently, for example it might be more universal, in such a context compared to times of political stability.

Next, electoral choice, i.e., voting for a party that won the election and later formed the government, showed no associations with political engagement, neither during the pre- nor the post-election period in none of the examined samples. Finally, being a first-time voter was related to changes in German young voters’ political attentiveness during the campaign period but not to changes in intentions for participation. More precisely, only first-time voters reported an increase in political attentiveness during the campaign period (i.e., T1 – T2). This pattern might be explained by the fact that first-time voters are often less decided and knowledgeable at the outset of an election campaign than more experienced young voters (Fournier et al., 2004; Ha et al., 2013). The significant increase in political attentiveness during the pre-election period might therefore reflect young first-time voters’ active search for more information and exchange to make a firm decision on election day. The samples from Czech Republic and Sweden included first-time voters only and could replicate the significant increase in political attentiveness for Swedish youth (for the Czech subgroup, see discussion on specifics during the campaign period above). No other interindividual differences were found in Germany, Czech Republic, or Sweden.

In sum, these results showed that changes in political engagement vary only slightly over the course of an election year according to young voters’ prior political experiences and electoral choice. This suggests that the findings regarding over-time changes in political engagement might be applicable to most young voters in the studied national contexts.

To date, few longitudinal studies have examined changes in political engagement among young people over the course of national elections – particularly outside of the United States. Most research still builds on cross-sectional designs and adult samples (e.g., Stevenson and Vavreck, 2000; Arceneaux, 2006). The current study aimed to contribute to the literature by following young voters across three measurement points in Germany, Czech Republic, and Sweden. Despite differences in measurement and sample characteristics, varying country contexts, as well as varying degrees of each elections’ level of politicization (low in Germany and Sweden; rather high in the Czech Republic), the results showed robust changes in young voters’ political engagement over the course of an election year. The results also revealed that these effects persisted in the months following the elections, underscoring the socializing value of major political events.

Several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, the study focused on young voters only. Although most youth did vote in all three samples, resulting in the non-voter subgroup being too small and diverse to be included in the analyses, more research is needed that compares changes in political engagement among young voters and non-voters to gain a deepened understanding of electoral effects. Second, and on a related note, we were not able to parse out the concrete mechanisms underlying the mobilizing effect of a political election within the scope of the present research. Hence, future studies should consider in greater detail whether it is the act of voting which drives the mobilizing effects of elections or rather a generally enhanced salience and visibility of political topics via media coverage, news consumption, or discussions in social environments. Accounting for relevant comparison groups and operationalizing the assumed processes may provide concrete ways to do so. Apart from non-voters, future studies could also follow a comparable group of youth during a non-election period to gain a more comprehensive understanding. In addition, more frequent assessments (e.g., in form of daily diary methods) around the time of the election could provide deepened insights into the developmental processes involved. In this regard, the timing of data collection should also be considered more explicitly as it was shown to be associated with survey cooperation and thus data quality across electoral cycles (Banducci and Stevens, 2015). Third, several characteristics of our samples need to be pointed out: Due to the studies’ longitudinal nature, not all participants were available at all measurement points. In all three countries, attrition was substantial between Time 1 and Time 2. Hence, a possible bias due to data attrition cannot be ruled out. It should also be taken into account that German university students were a rather homogeneous group in terms of educational level and socio-economic background. Nevertheless, the Czech and Swedish samples were more diverse and showed a similar pattern of results as in the German sample. Moreover, the present study had rather small sample sizes and was conducted in only three countries. Since each country is characterized by a particular political and electoral party system, further research with larger samples and in different national contexts is necessary to make more generalizable statements. Finally, we tracked youth political engagement for 6 months after the elections and are not able to say whether the heightened levels of engagement post-election persist over a longer time. More research is needed that follows youth political engagement over a couple of years to see whether the activating effects of elections remain or whether engagement slowly goes back to the pre-election levels for some youth.

Across various countries young voters abstain from the poll more often than older voters. Young people also approach traditional and institutionalized political domains with greater skepticism and distance. Our findings indicate that major elections can activate young people to become politically engaged. Drawing on three samples of young voters, the present study reveals increases in political engagement in the context of the national elections in Germany, Czech Republic, and Sweden, residues of which persisted post elections. With the exception of German young adults, who were previously less engaged or first-time voters and showed higher increases in engagement during the election, there were few interindividual differences, suggesting robust findings applicable to most young people in the studied country contexts. This research underscores the general importance of the macro-context for political development and, in particular, the socializing value of major political events. It provides hope that even if young people are initially indifferent, their participation in the electoral process can activate an engagement in politics. This research also suggests that late adolescence and young adulthood provide a window of opportunity for schools, media, political parties, and various civic initiatives to reach young voters to facilitate formation of their engagement habits.

The final datasets of the analyses and the input syntaxes are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10711999.

The German study was approved by the Ministry of Education, Thuringia. The Swedish study received the ethical approval of the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala (Dnr, 2010/115). Ethical review and approval was not required for the study in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements at Masaryk University, Czechia. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants or their parents provided their written informed consent to participate in the studies (passive consent was obtained in the Swedish study).

KE: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JŠ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PN: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AK: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. MM work on this project was funded by grants from Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (P20-0599), Vetenskapsrådet (2023-05833), and IGDORE Sweden Foundation. This study was made possible by access to data from the Political Socialization Program at Örebro University, Sweden. Responsible for the planning, implementation, and financing of the collection of data were professors Erik Amnå, Mats Ekström, Margaret Kerr, and Håkan Stattin. The data collection was supported by grants from Riksbankens Jubileumsfond. JS work on this project was supported by Masaryk University (MUNI/A/1596/2023). We acknowledge support by the German Research Foundation Projekt-Nr. 512648189 and the Open Access Publication Fund of the Thueringer Universitaets- und Landesbibliothek Jena.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^The terms youth/ young people are used when referring to a broader age range, including both adolescence and young adulthood. When referring to a specific age group, adolescence and young adulthood are explicitly differentiated.

2. ^The subgroups of non-voters were too diverse and small to allow for a reliable comparison with voters in all three countries. More information can be obtained upon request from the authors.

Aalberg, T., and Jenssen, A. (2007). Do television debates in multiparty systems affect viewers? A quasi-experimental study with first-time voters. Scand. Polit. Stud. 30, 115–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2007.00175.x

American Psychological Association (2002). Developing adolescents: A reference for professionals. Available at: https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/develop.pdf

Amnå, E., and Ekman, J. (2014). Standby citizens: diverse faces of political passivity. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 6, 261–281. doi: 10.1017/S175577391300009X

Arceneaux, K. (2006). Do campaigns help voters learn? A cross-national analysis. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 36, 159–173. doi: 10.1017/S0007123406000081

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 55, 469–480. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.469

Banducci, S., and Stevens, D. (2015). Surveys in context: how timing in the electoral cycle influences response propensity and satisficing. Public Opin. Q. 79, 214–243. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfv007

Bhatti, Y., Hansen, K. M., and Wass, H. (2012). The relationship between age and turnout: a roller-coaster ride. Elect. Stud. 31, 588–593. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2012.05.007

Borge, J. A. Ø. (2017). Tuning in to formal politics: mock elections at school and the intention of electoral participation among first time voters in Norway. Politics 37, 201–214. doi: 10.1177/0263395716674730

Bowler, S., and Donovan, T. (2002). Democracy, institutions and attitudes about citizen influence on government. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 32, 371–390. doi: 10.1017/S0007123402000157

Bowler, S., Donovan, T., and Tolbert, C. (1998). Citizens as legislators: Direct democracy in the United States. Ohio State University Press. Columbus

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Chevalier, T. (2019). Political trust, young people and institutions in Europe. A multilevel analysis. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 28, 418–430. doi: 10.1111/ijsw.12380

Citrin, J. (1996). “Who’s the boss? Direct democracy and popular control of government” in Broken contract? ed. S. Craig (Boulder: Westview)

Coffey, D. J., Miller, W. J., and Feuerstein, D. (2011). Classroom as reality: demonstrating campaign effects through live simulation. J. Polit. Sci. Educ. 7, 14–33. doi: 10.1080/15512169.2011.539906

Dinas, E. (2010). The impressionable years: The Formative role of family, vote and political events during early adulthood, European University Institute. Fiesole

Dinas, E. (2013). Opening “openness to change”: political events and the increased sensitivity of young adults. Polit. Res. Q. 66, 868–882. doi: 10.1177/1065912913475874

Eckstein, K., and Noack, P. (2014). Students' democratic experiences in school: a multilevel analysis of social-emotional influences. Int. J. Dev. Sci. 8, 105–114. doi: 10.3233/DEV-14136

Eckstein, K., and Noack, P. (2016). Classroom climate effects on adolescents' orientations toward political behaviors: a multilevel approach. In P. Thijssen, J. Siongers, J. Laervan, J. Haers, and S. Mels Political engagement of the young in Europe: Youth in the crucible (pp. 161–177). Routledge/Taylor & Francis. New York, NY

Eckstein, K., Šerek, J., and Noack, P. (2018). And what about siblings? A longitudinal analysis of sibling effects on youth's intergroup attitudes. J. Youth Adolesc. 47, 383–397. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0713-5

Erikson, R. S., and Stoker, L. (2011). Caught in the draft: the effects of Vietnam draft lottery status on political attitudes. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 105, 221–237. doi: 10.1017/S0003055411000141

Fournier, P., Nadeau, R., and Blais, A. (2004). Time-of-voting decision and susceptibility to campaign effects. Elect. Stud. 23, 661–681. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2003.09.001

Franklin, M. , (2004). Voter turnout and the dynamics of electoral competition in established democracies since 1945. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Franklin, M. N., and Hobolt, S. B. (2011). The legacy of lethargy: how elections to the European Parliament depress turnout. Elect. Stud. 30, 67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2010.09.019

Friedrich, W., and Förster, P. (1997). “Political orientations of east German youth and young adults in the transformation process” in Entwicklung und Sozialisation von Jugendlichen vor und nach der Vereinigung Deutschlands. ed. H. Sydow (Opladen: Leske+Budrich), 17–73.

Ghitza, Y., Gelman, A., and Auerbach, J. (2023). The great society, Reagan’s revolution, and generations of presidential voting. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 67, 520–537. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12713

Gimpel, J. G., Lay, C. J., and Schuknecht, J. E. (2003). Cultivating democracy: Civic environments and political socialization in America. Brookings Institution Press. Washington, DC

Ha, L. S., Wang, F., Fang, L., Yang, C., Hu, X., Yang, L., et al. (2013). Political efficacy and the use of local and national news media among undecided voters in a swing state: a study of general population voters and first-time college student voters. Electron. News 7, 204–222. doi: 10.1177/1931243113515678

Hayes, D., and Lawless, J. L. (2015). As local news goes, so goes citizen engagement: media, knowledge, and participation in US house elections. J. Polit. 77, 447–462. doi: 10.1086/679749

Hess, R. D., and Torney, J. V. (1967). The development of political attitudes in children. Aldine. London

Hibbing, J., and Theiss-Morse, E. (2001). Process preferences and American politics: what the people want government to be. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 95, 145–153. doi: 10.1017/S0003055401000107

Holt, K., Shehata, A., Strömbäck, J., and Ljungberg, E. (2013). Age and the effects of news media attention and social media use on political interest and participation: do social media function as leveller? Eur. J. Commun. 28, 19–34. doi: 10.1177/0267323112465369

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Klemm, K. (2016). “Soziale Herkunft und Bildung im Spiegel neuerer Studien [social background and education in the light of recent studies]” in Soziale Herkunft und Bildungserfolg. Netzwerk Bildung. eds. B. Jungkamp and M. John-Ohnesorg (Washington, DC: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung), 17–22.

Konzelmann, L., Wagner, C., and Rattinger, H. (2012). Turnout in Germany in the course of time: life cycle and cohort effects on electoral turnout from 1953 to 2049. Elect. Stud. 31, 250–261. doi: 10.1016/J.ELECTSTUD.2011.11.006

Kruikemeier, S., and Shehata, A. (2017). News media use and political engagement among adolescents: an analysis of virtuous circles using panel data. Polit. Commun. 34, 221–242. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2016.1174760

Kuhn, H. P., and Schmid, C. (2002). Conditions of political and social engagement of high school students in Brandenburg. Zeitschrift für politische Psychologie 10, 53–76.

Legget-James, M. P., Eckstein, K., Richmond, A., Noack, P., and Laurson, B. (2023). The spread of political alienation from parents to adolescent children. The spread of political alienation from parents to adolescent children. J. Fam. Psychol. 37, 947–953. doi: 10.1037/fam0001098

Linek, L. (2012). Voters and elections 2010. Sociologické nakladatelství / Sociologický ústav AV ČR.

Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 83, 1198–1202. doi: 10.2307/2290157

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., and Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct. Equ. Model. 9, 151–173. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

Little, T. D., Rhemtulla, M., Gibson, K., and Schoemann, A. M. (2013). Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychol. Methods 18, 285–300. doi: 10.1037/a0033266

Lundberg, E. (2024). Can participation in mock elections boost civic competence among students? J. Polit. Sci. Educ., 1–18. doi: 10.1080/15512169.2023.2300425

Markus, G. B. (1979). The political environment and the dynamics of public attitudes: a panel study. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 23, 338–359. doi: 10.2307/2111006

Marsh, H. W., Byrne, B. M., and Craven, R. (1992). Overcoming problems in confirmatory factor analyses of MTMM data: the correlated uniqueness model and factorial invariance. Multivar. Behav. Res. 27, 489–507. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2704_1

McDevitt, M., and Chaffee, S. H. (2002). From top-down to trickle-up influence: revisiting assumptions about the family in political socialization. Polit. Commun. 19, 281–301. doi: 10.1080/01957470290055501

McDevitt, M., and Kiousis, S. K. (2004). Education for deliberative democracy: The long-term influence of Kids Voting USA. CIRCLE Working Paper 22. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED498897.pdf

Memoli, V. (2020). The effect of the media in times of political distrust: the case of European countries. Italian J. Electoral Stud. 83, 59–72. doi: 10.36253/qoe-9532

Miklikowska, M. (2016). Like parent, like child? Development of prejudice and tolerance in adolescence. Br. J. Psychol. 107, 95–116. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12124

Miklikowska, M., Rekker, R., and Kudrnac, A. (2022). A little more conversation, a little less prejudice: the role of classroom political discussions for youth attitudes toward immigrants. Polit. Commun. 39, 405–427. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2022.2032502

Miklikowska, M., Thijs, J., and Hjerm, M. (2019). The impact of perceived teacher support on anti-immigrant attitudes from early to late adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 48, 1175–1189. doi: 10.1007/s10964-019-00990-8

Mo, C. H., Holbein, J. B., and Elder, E. M. (2022). Civilian national service programs can powerfully increase youth voter turnout. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 119:e2122996119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2122996119

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (1998–2018). Mplus user's guide : 8th. Muthén & Muthén. Los Angeles, CA

Neundorf, A., and Smets, K. (2017). Political socialization and the making of citizens. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Noack, P., and Eckstein, K. (2023). Populism in youth: do experiences in school matter? Child Dev. Perspect. 17, 90–96. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12481

Ohme, J., de Vreese, C. H., and Albaek, E. (2018). The uncertain first-time voter: effects of political media exposure on young citizens’ formation of vote choice in a digital media environment. New Media Soc. 20, 3243–3265. doi: 10.1177/1461444817745017

Öhrvall, R., and Oskarsson, S. (2020). Practice makes voters? Effects of student mock elections on turnout. Politics 40, 377–393. doi: 10.1177/0263395719875110

Parth, A., Weiss, J., Firat, R., and Eberhardt, M. (2020). “How dare you!”—the influence of Fridays for future on the political attitudes of young adults. Front. Polit. Sci. 2:611139. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.611139

Plescia, C., Daoust, J.-F., and Blais, A. (2021). Do European elections enhance satisfaction with European Union democracy? Europ. Union Politics 22, 94–113. doi: 10.1177/1465116520970280

Rioux, C., Stickley, Z. L., Odejimi, O. A., and Little, T. D. (2020). Item parcels as indicators: why, when, and how to use them in small sample research. In R. Schootvan de and M. Miocević Small sample size solutions: A guide for applied researchers and practitioners (pp. 203–214). Routledge, London.

Schmid, C. (2001). “Methode der Untersuchung [survey method]” in Jugendliche Wähler in den neuen Bundesländern. eds. H.-P. Kuhn, K. Weiss, and H. Oswald (Opladen: Leske + Budrich), 64–67.

Sears, D. O., and Levy, S. (2003). “Childhood and adult political development” in Oxford handbook of political psychology. eds. D. O. Sears, L. Huddy, and R. Jervis (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 60–109.

Sears, D. O., and Valentino, N. A. (1997). Politics matters: political events as catalysts for preadults socialization. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 91, 45–65. doi: 10.2307/2952258

Šerek, J., and Umemura, T. (2015). Changes in late adolescents’ voting intentions during the election campaign: disentangling the effects of political communication with parents, peers and media. Eur. J. Commun. 30, 285–300. doi: 10.1177/0267323115577306

Shani, M., Horn, D., and Boehnke, K. (2020). “Developmental trajectories of political engagement from adolescence to mid-adulthood: a review with empirical underpinnings from the German peace movement” in Children and peace. Peace psychology book series. eds. N. Balvin and D. J. Christie (Berlin: Springer)

Smets, K. (2012). A widening generational divide? The age gap in voter turnout through time and space. J. Elect. Public Opin Parties 22, 407–430. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2012.728221

Smets, K., and Neundorf, A. (2014). The hierarchies of age-period-cohort research: political context and the development of generational turnout patterns. Elect. Stud. 33, 41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2013.06.009

Smith, M., Tsai, S. L., Matějů, P., and Huang, M. H. (2016). Educational expansion and inequality in Taiwan and the Czech Republic. Comp. Educ. Rev. 60, 339–374. doi: 10.1086/685695

Statistics Sweden (2016). Statistical database. Available at: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/

Stevenson, R. T., and Vavreck, L. (2000). Does campaign length matter? Testing for cross-national effects. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 30, 217–235. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400000107

Steyer, R., Eid, M., and Schwenkmezger, P. (1997). Modeling true intraindividual change: true change as a latent variable. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2, 21–33. doi: 10.23668/psycharchives.12718

Titley, G. (2021). From all different – all equal to Black Lives Matter: An introduction. Council of Europe. Available at: https://www.coe.int/en/web/all-different-all-equal/from-all-different-all-equal-to-black-lives-matter

Tolbert, C. J., McNeal, R. S., and Smith, D. A. (2003). Participation and knowledge enhancing civic engagement: the effect of direct democracy on political participation and knowledge. State Polit. Policy Q. 3, 23–41. doi: 10.1177/153244000300300102

Valentino, N. A., and Sears, D. O. (1998). Event-driven political communication and the preadult socialization of partisanship. Polit. Behav. 20, 127–154. doi: 10.1023/A:1024880713245

Wagner, M., David, J., and Kritzinger, S. (2012). Voting at 16: turnout and the quality of vote choice. Elect. Stud. 31, 372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2012.01.007

Keywords: elections, political engagement, election participation, young voters, political socialization

Citation: Eckstein K, Miklikowska M, Šerek J, Noack P and Koerner A (2024) Activating effects of elections: changes in young voters’ political engagement over the course of an election year. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1302686. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1302686

Received: 26 September 2023; Accepted: 27 March 2024;

Published: 17 April 2024.

Edited by:

Anne-Marie Jeannet, University of Milan, ItalyReviewed by:

Leo Azzollini, University of Oxford, United KingdomCopyright © 2024 Eckstein, Miklikowska, Šerek, Noack and Koerner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katharina Eckstein, a2F0aGFyaW5hLmVja3N0ZWluQHVuaS1qZW5hLmRl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.