- Department of Political Science, University of Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland

Due to widespread citizen disenchantment with representative democracy, the introduction of direct-democratic institutions is often promoted as a promising remedy to overcome the current democratic crisis. Theorists of participatory democracy have argued that direct democracy can foster civic virtues, given that the opportunity to participate in referendums and initiatives is generally expected to empower and enlighten citizens. By conducting a systematic literature review, this article aims to provide an overview of scholarship on how direct democracy delivers on its promise to increase individual civic virtues. To that end, it focuses on the effects of direct democracy on those four areas to which scholars have devoted much attention so far: (1) electoral turnout, (2) external and internal efficacy, (3) political knowledge, and (4) subjective wellbeing and satisfaction with democracy. Based on 67 selected studies, it turns out that there is only little positive overall effect of direct democracy on civic virtues, with a great deal of variation. The empirical analysis establishes a negative time trend, indicating that researchers have increasingly reported negative findings over the years. This main result calls into question the expectations advanced by the theorists of participatory democracy and gives some credit to more skeptical views. This review concludes by providing scholars with new avenues for research.

Introduction

Although democracy is generally regarded as superior to other forms of government, a widespread malaise can be observed in many Western democracies today. More specifically, citizens have exhibited increasing disenchantment with the functioning of representative democracy over the last decades (e.g., Pharr and Putnam, 2000; Pitkin, 2004). This concerning trend manifests itself in various symptoms such as lower participation rates, a growing alienation between citizens and their representatives, decreasing trust in elites and institutions, more frequent electoral successes of populist actors, and even recurring social unrest, all of which ultimately call into question the legitimacy of representative democracy (Leininger, 2015; Altman, 2019; Vatter et al., 2019).

In this context, new participation rights in general and the introduction of direct-democratic institutions in particular are often discussed as promising remedies to overcome the current democratic crisis (e.g., Cain et al., 2003). In line with the theorists of participatory democracy (Pateman, 1970; Barber, 2003), the hope is that, by providing citizens with the opportunity to participate in democratic decision-making, the legitimacy of the political system will be restored. Indeed, direct democracy enjoys great popularity in representative democracies. International comparative surveys have shown that the overwhelming majority of respondents in most countries welcome the introduction of referendums and initiatives (e.g., Bowler and Donovan, 2019; Bessen, 2020). This strong demand for increased participation rights does not seem to have been quenched by the rise in the number of direct-democratic votes across the world over the last decades (Brüggemann et al., 2023).

As an increasing number of citizens have gained experience with direct democracy over recent years, scholars have expressed increased interest in studying whether such devices can deliver on their promises. At the most basic level, academic contributions draw a distinction between (primary) instrumental and (secondary) spillover effects (e.g., Tolbert and Smith, 2006). Whereas the first refers to policy outcomes, the latter is concerned with actor behavior and attitudes that go beyond specific issue-related decisions. As far as the instrumental effects are concerned, empirical studies have primarily focused on economic performance, congruence between citizen preferences and policy outcomes, and protection of minority rights. Except for the latter, a rather consistently positive picture emerges from the state-of-the-art (Lupia and Matsuaka, 2004; Matsusaka, 2005; Maduz, 2010; Vatter et al., 2019). This conclusion is in line with the view that, despite the much-discussed risk of subversion by special interest, direct democracy generally ‘serves the many and not the few’, as Matsusaka (2005: 200) put it.

Regarding the spillover effects, the evidence seems to be much more disputed. This is remarkable since the proponents of direct democracy have long dominated the field, both from theoretical and empirical points of view. Following participatory theories, direct democracy used to be predominantly regarded as a valuable element of democratic citizenship by scholars. The possibility to take part in referendums and initiatives was expected to empower and enlighten citizens by bolstering their civic virtues in democratic life (e.g., Frey, 1997). In accordance with this line of reasoning, numerous studies have found evidence for such desirable ‘educational effects’, above all in terms of participation, efficacy, knowledge, and satisfaction (Smith and Tolbert, 2019). However, due to the emergence of non-significant and negative effects, some serious doubts have been cast on the prevailing view about the positive side effects of direct democracy. Contrary to the classical elitist and realist theorists (Schumpeter, 1942; Sartori, 1987), who emphasized the presumed political disinterest and widespread incompetence of ordinary citizens, these challenging studies basically refute the thesis of educational effects (at least in the case of the United States) by arguing that ballot measures intensify partisan conflict around an issue, since mobilizing actors have an incentive to strongly criticize the jobs made by members of the government and legislators (see Dyck and Lascher, 2019).

This article aims to provide an overview of scholarship on the question of whether direct democracy increases individual civic virtues by relying on a systematic literature review. To that end, it focuses on the effects of direct democracy on those four areas to which scholars have devoted much attention so far: (1) electoral turnout, (2) external and internal efficacy, (3) political knowledge, and (4) subjective wellbeing and satisfaction with democracy. Note that the fourth area includes both individual and collective dimensions, whereas the latter refers to political support and institutional trust in addition to satisfaction with democracy. Based on a selection of 67 studies, it turns out that there is only little positive overall effect of direct democracy on civic virtues, with a great deal of variation. The empirical analysis establishes a negative time trend, indicating that scholars increasingly reported negative findings over the years. The main result of this review thus calls into question the expectations advanced by theorists of participatory democracy and gives some credit to the skeptics of direct democracy.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: The following section describes the procedure for the selection of studies that are used for this systematic literature review. Thereafter, the empirical results are presented in two steps. After an overall analysis, the effects of direct democracy are studied at the level of four selected civic virtues. Finally, the last section summarizes the main findings and provides interested scholars with some advice for future empirical investigations.

Selection method

In this section, I shall specify the strategy adopted to search the literature and the criteria used to select the analyzed studies. Given that the objective of this article is to provide an overview of the effects of direct democracy (independent variable) on a selection of civic virtues (dependent variables), I decided to focus the search strings on these two crucial elements. For the independent variable, the strategy consisted in relying on ‘direct democracy’ as well as on two of its most common synonyms: ‘referendums’ and ‘initiatives’ or ‘ballot initiatives’. This resulted in three search terms ‘direct democra*’, ‘referend*’, and ‘ballot’. Asterisks were employed to account for possible singular forms (e.g., ‘referendum’), adjectives (e.g., ‘direct democratic’), and different spellings (e.g., ‘referenda’). Note that ‘initiatives’ were eventually omitted, given that the inclusion of the term ‘initiative*’ would have produced far too many search results, the vast majority being not related to direct democracy.

As to the dependent variables, the search strings refer to each of the selected civic virtues. Regarding electoral turnout, I decided to resort to ‘turnout’ as well as to ‘electoral participation’ and ‘voter participation’, since the more general term ‘participation’ yielded a non-manageable number of results.1 While I ultimately stick with ‘efficac*’ for external and internal efficacy, I rely on knowledge (‘knowledge*’) and awareness (‘aware*’) for the domain of political knowledge. Finally, the relatively broader area of satisfaction is ultimately covered by four search terms. In addition to the obvious and general ‘satsif*’, ‘happiness’ is meant to cover the individual dimension, whereas the selection of ‘political support’ and ‘trust’ is expected to ensure the inclusion of studies that focus on the collective dimension.2

The pre-selection required to include at least one of the three search terms on direct democracy as well as at least one of the 10 just mentioned virtue-specific terms. This resulted in the following search query:

(turnout OR “electoral participation” OR “voter participation” OR “efficac*” OR “knowledge*” OR “aware*” OR “satisf*” OR happiness OR “political support” OR trust) AND (“direct democra*” OR referend* OR ballot)

This search query was entered into the Web of Science database in August 2023 by making use of two restrictions. First, I used the topic search option, meaning the records only applied to the title, abstract, and keywords fields. Second, I limited the search query to articles published in scientific journals, thus leaving aside other formats such as books, PhD theses, and data studies. In doing so, my pre-selection amounted to 2,016 records.

To select suitable studies for analysis, a couple of inclusion and exclusion criteria were subsequently implemented. Most importantly, from a substantial point of view, I retained those articles that contained at least an empirical analysis that examined the effects of direct democracy on at least one of the four selected civic virtues. More specifically, variations in terms of direct-democratic contexts had to be present on the dependent variable(s). Note that there is a distinction between genuine direct-democratic and non-direct-democratic contexts. For the latter (i.e., contexts outside Switzerland and the subnational level of the United States), I also decided to include longitudinal studies on single direct-democratic votes. Such ‘change analyses’ (i.e., before and after a vote) examine a substantial increase in terms of direct democracy in essentially representative political systems. It also needs to be mentioned that studies had to report the overall effects of direct-democracy variables for being selected, meaning that empirical analyses limited to the effects of a particular segment of the population (e.g., participating voters as opposed to all respondents) were removed.

As to the dependent variables, I specified the inclusion criteria on the level of each civic virtue. Regarding electoral turnout, I restricted the selection to participation rates in official elections and direct-democratic votes. With respect to efficacy, I considered studies on both internal and external efficacy. As to political knowledge, I limited myself to analyses that use factual political knowledge items.3 Hence, both general and issue-specific knowledge were included. Finally, the studies on satisfaction included subjective wellbeing and happiness at the individual level, along with institutional trust, political support, and satisfaction with democracy at the contextual level.

From a formal point of view, I only included articles written in English. A total of 48 articles met these criteria. In a second step, I replicated this procedure in Scopus, Elsevier’s citation and abstract database. This yielded four additional articles. Finally, I relied on Google Scholar, a web search engine for scholarly literature that can be regarded as a useful complementary resource (Gusenbauer and Haddaway, 2020). This added two articles to my stock of 54 articles in total.4 However, since some articles focused on several dependent variables of interest, the number of selected relationships between direct democracy and the selected civic virtues amounts to 67 for the present analysis.

As to the selected civic virtues, most of these empirically analyzed relationships focused on electoral turnout (42%), followed by satisfaction (28%), efficacy (21%), and knowledge (9%).5 The selection at hand is dominated by subnational studies, with 70% taking full advantage of variations at the regional level (such as US states and Swiss cantons) and 10% at the local level. In addition, all studies were conducted in a quantitative manner. Furthermore, it is noticeable that the selected analyses were published on a rather regular basis between 2000 (oldest contributions) and 2023 (newest ones), with the median year being 2011. Almost four in five analyses refer to the individual level (79%) using representative survey data that were enriched with contextual data, at least about variations in terms of direct democracy, with the remaining ones limiting themselves to the contextual level (21%). As for their general design, 54% of the selected analyses are cross-sectional in nature, 37% are time-series and cross-section analyses, while the remaining 9% are purely longitudinal. In geographical terms, the United States of America proves to be the most studied country context (48%). Next in line is Switzerland (22%), while internationally comparative studies account for 16% and other single-country studies account for 12% of the selection.6

Empirical analysis

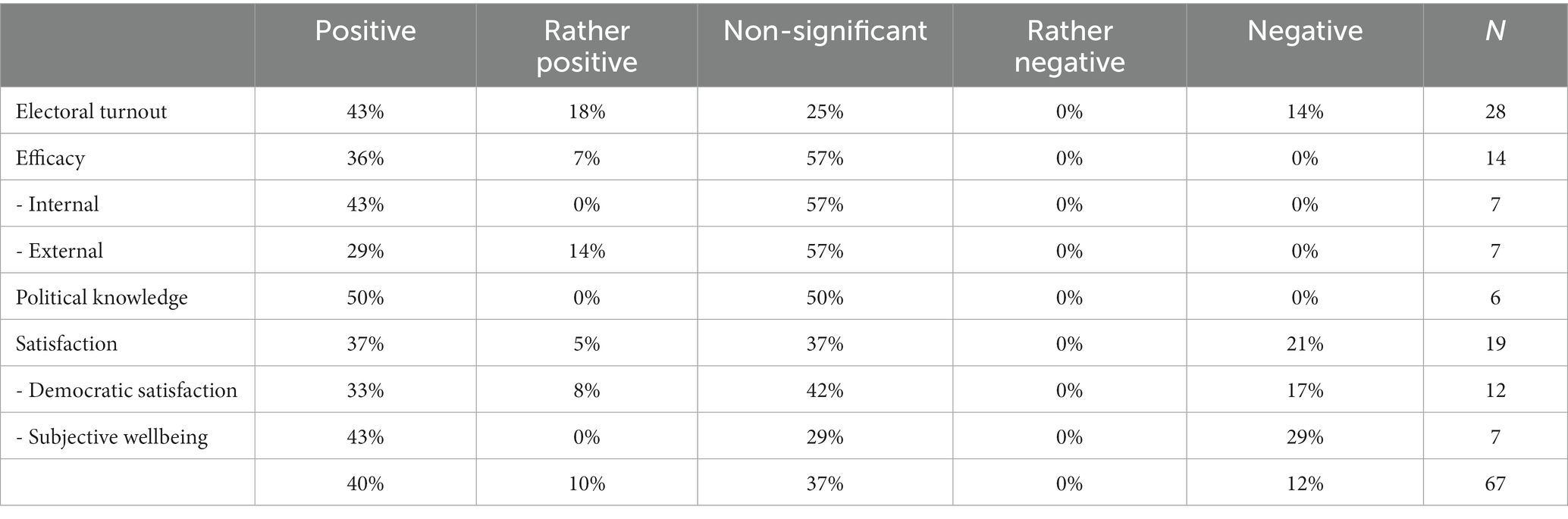

To give an overview of the effects of direct democracy on civic virtues, I relied on a content analysis. For each of the 67 selected studies, I coded the reported outcome on a 5-level Likert scale that ranges from −1 to 1. Code 1 stands for a positive effect, 0.5 for a rather positive, 0 for an insignificant, −0.5 for a rather negative, and −1 for a negative one.7 With an average score of 0.34, the indicator turns to slightly point toward the positive direction. Hence, there is only little positive overall effect of direct democracy on civic virtues. Probably equally important, the standard deviation of 0.65 reveals a high degree of variation. As shown in Table 1, the positive effects are most frequent with 40% of the studies, and a further 10% prove to be rather positive. However, an important share of 37% report insignificant effects, while negative ones are present in almost one out of eight cases (12%). This rather great deal of variation confirms that the state-of-the art can be qualified as mixed and inconclusive when it comes to the research question of whether direct democracy bolsters civic virtues.

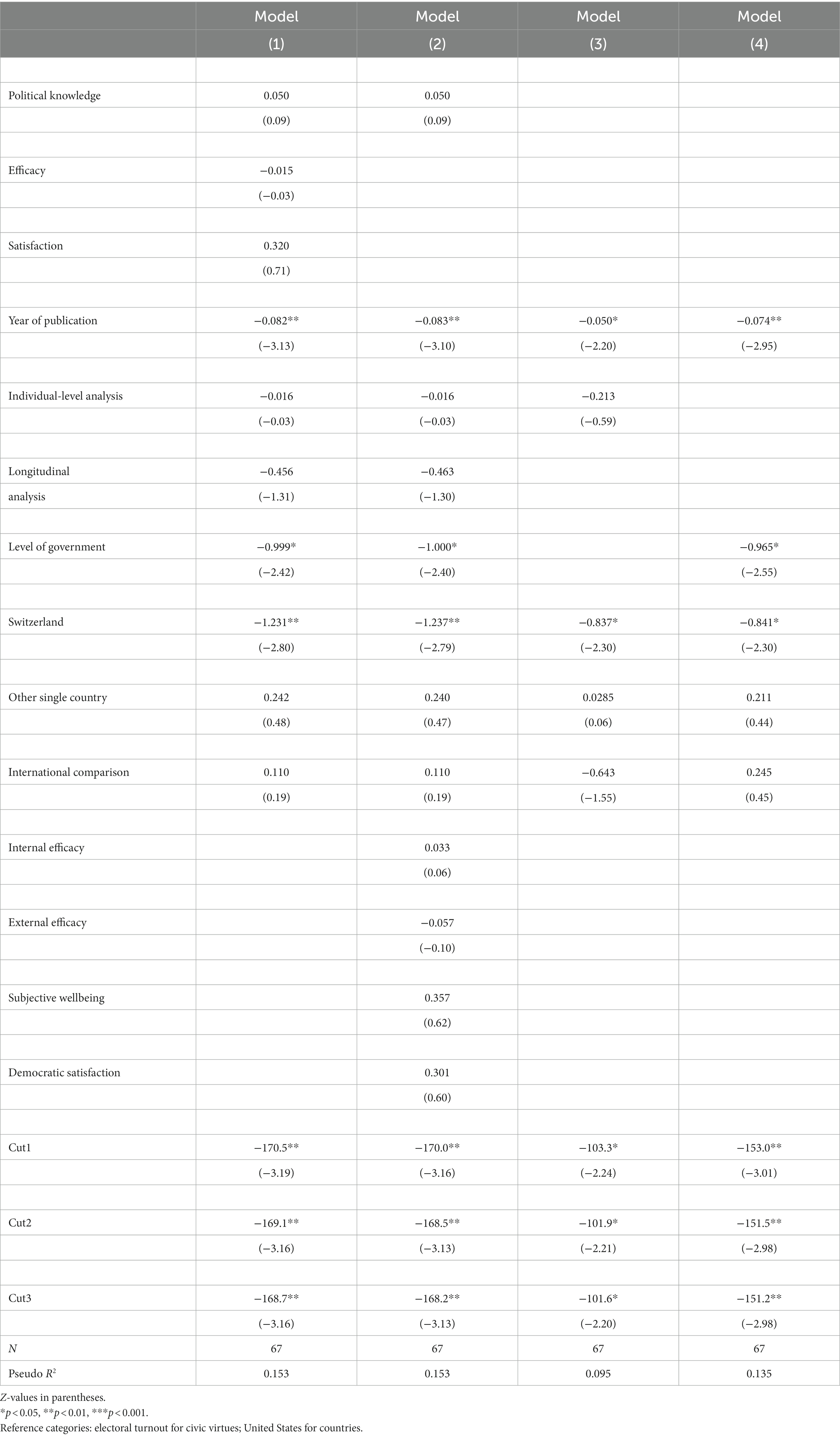

To explain this variation from a statistical point of view, I performed a multivariate analysis that accounts for the type of civic virtues, the year of publication, the level of government, the overall design, and the geographic context. The results of four ordered probit estimations are presented in Table 2. Model 1 distinguishes between the four main civic virtues, while model 2 includes the two subcategories for efficacy and satisfaction. Due to the small number of cases at hand, a reviewer has convincingly suggested to account for fewer explanatory variables. Model 3 is thus limited to the year of publication, the overall design, and the geographical indicators, while Model 4 is restricted to the three determinants that prove to be statistically significant in this analysis (see next paragraph). I also need to mention that the results are robust when using a binary dependent variable that distinguishes between positive results (i.e., code 1 of the Likert scale) and the remaining outcomes. These models are presented in Appendix Table A1.

Table 2. Ordered probit models explaining the positivity of direct democracy’s effect on civic virtues.

Furthermore In summary, three factors are found to exert a systematic influence on the outcome of interest. First and most importantly, the significantly negative coefficient for the year of publication indicates that scholars generally published more negative results on the relationship between direct democracy and civic virtues over time. This finding is in line with the view that, after some initial optimism about the virtuous effects of direct democracy, concerns have intensified more recently. Second, the three-level indicator for the level of governments (3 = national, 2 = regional, 1 = local) consistently turns out to be negative from a statistical point of view. Hence, studies are more likely to report positive outcomes the lower the level of the jurisdictions they focus on. Third, this multivariate analysis shows that the studies on Switzerland tend to exhibit more negative effects than those on the United States (which serve as reference categories in both models). However, a closer look reveals that this discrepancy is most pronounced for electoral turnout, a finding that will be addressed in the second part of the empirical analysis.8

The remaining determinants prove to be statistically insignificant. Most importantly, for the study at hand, this applies to the selected civic virtues, as can be seen from models 1 and 2. This general non-finding may suggest that it is necessary to dig deeper to identify some possible patterns. Hence, the subsequent empirical analysis will take a closer look at electoral turnout, internal and external efficacy, political knowledge, and individual and collective satisfaction.

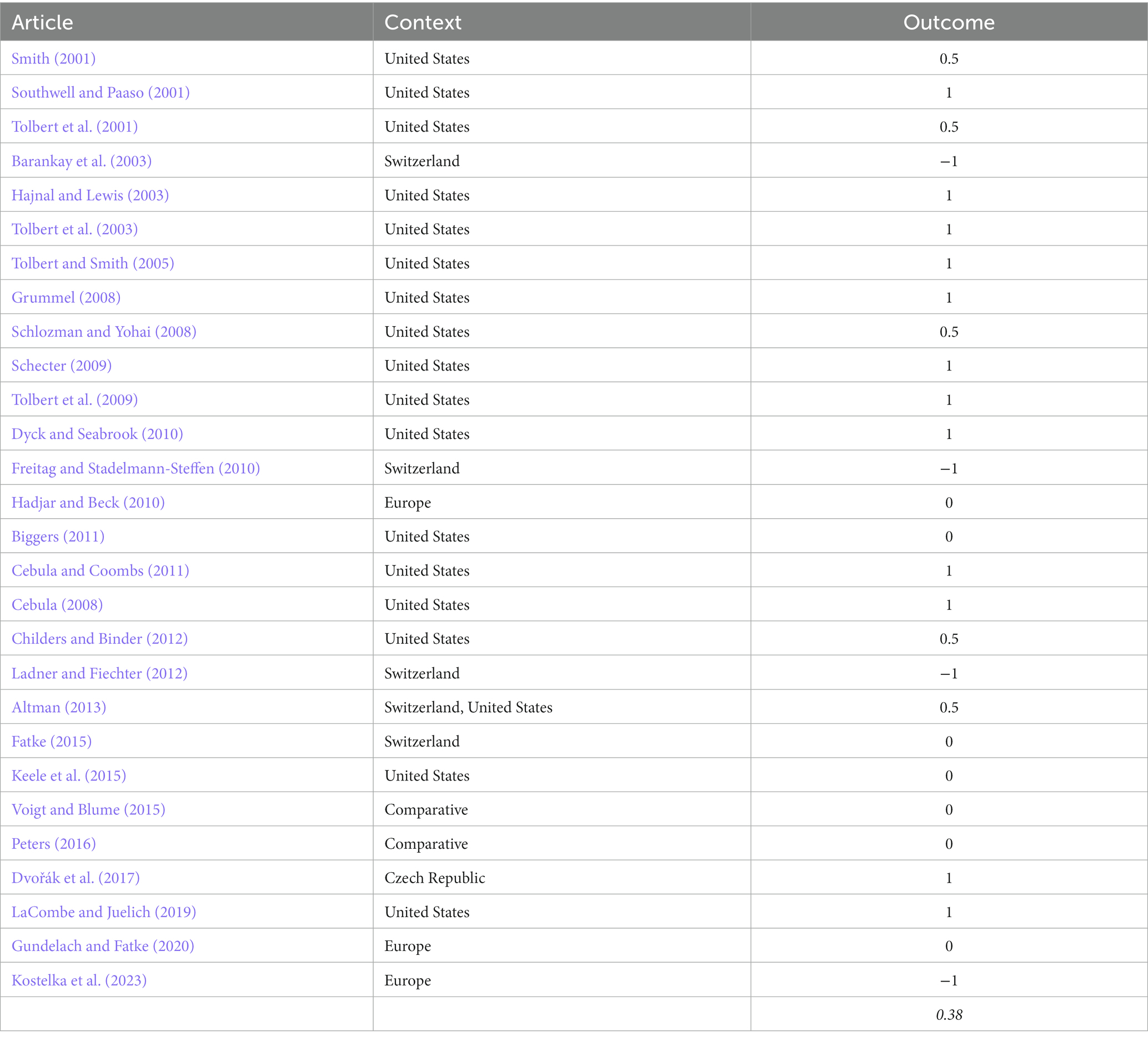

When it comes to the effect of direct democracy on electoral turnout, the mean reaches 0.38 across the selected 28 empirical analyses listed in Table 3. However, the direction of the effect proves to be highly context-specific. With an average score of 0.76, it appears that the 17 studies devoted exclusively to the United States predominantly arrive at positive findings. Despite the fact that only two studies (Biggers, 2011; Keele et al., 2015) conclude on a more pessimistic note by consistently reporting non-findings, there seems to be agreement among scholars that the election context matters a lot (see, for instance, Smith, 2001; Tolbert et al., 2003; Schlozman and Yohai, 2008; Childers and Binder, 2012). More specifically, the participation-boosting effect of direct democracy is more likely to be statistically significant in midterm elections than in regular general elections.

In line with the comparative study by Altman (2013), things turn out to be very different in the case of Switzerland (mean = −0.75). Indeed, three out of the four empirical analyses that focus on this country find that turnout is lower the more direct-democratic a given direct-democratic context. An explanation for the discrepancy with the United States may relate to the fact that national elections are usually not combined with direct-democratic votes held at the subnational level in the Swiss political system. Therefore, the strategic mobilization of voters by parties in the framework of concurrent elections is not of importance there.9 In addition, it needs to be highlighted that the five encompassing international comparisons mainly report insignificant effects (Hadjar and Beck, 2010; Voigt and Blume, 2015; Peters, 2016; Gundelach and Fatke, 2020). Considering the negative finding reported by Kostelka et al. (2023), the mean score for this subsample even slightly falls into the minus (−0.20).

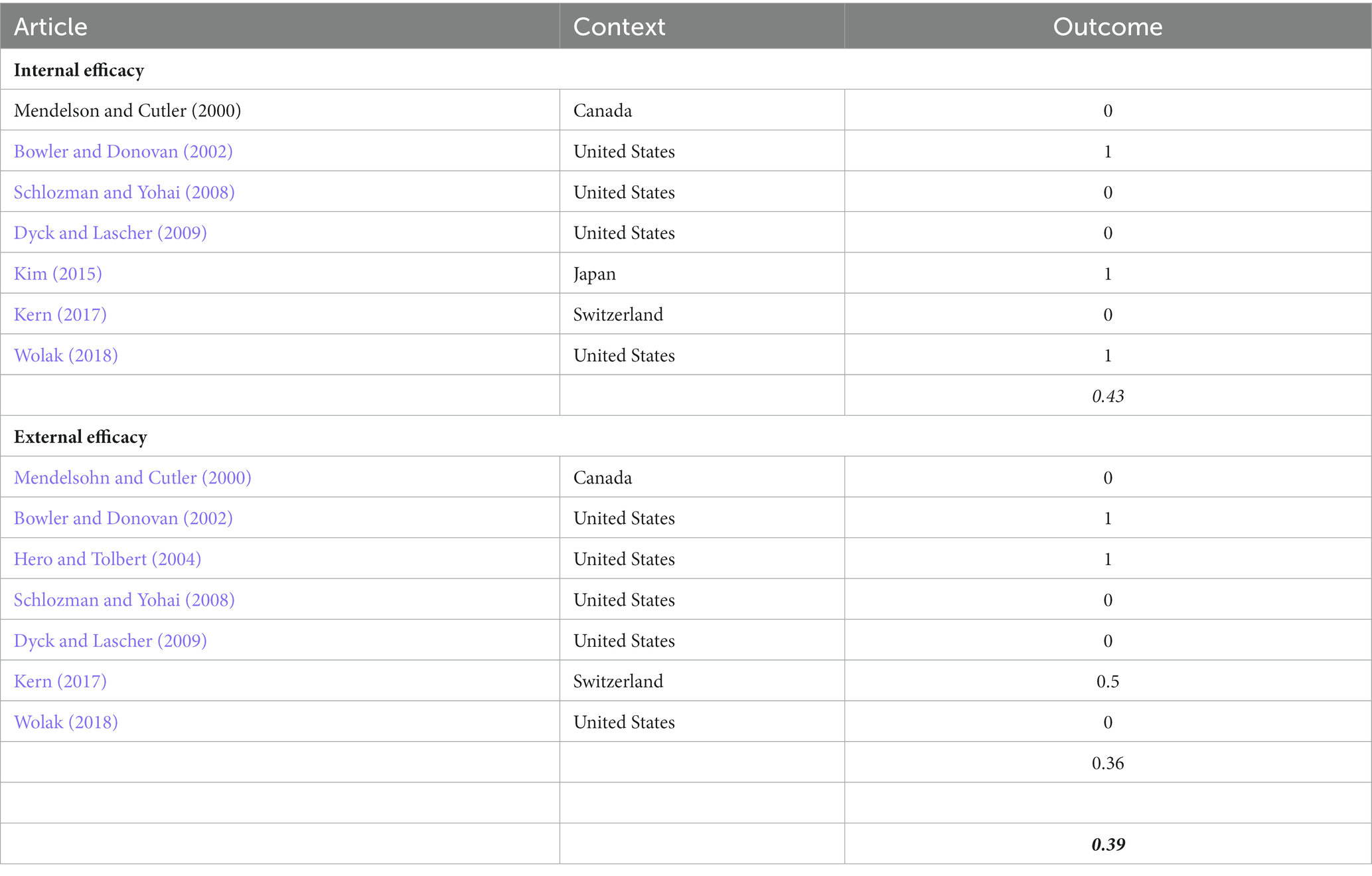

When it comes to the 14 studies on internal and external efficacy, there is obviously a domination by analyses that deal with North America. As seen in Table 4, nine of them focused on the United States and two on Canada. The remaining studies considered Switzerland (2) and Japan (1). While these empirical contributions arrive at slightly positive conclusions on average (mean = 0.39), it turns out that the studies on internal and external efficacy (0.43 vs. 0.36) do not systematically differ. Similarly, there are no clear patterns as to other key characteristics. Perhaps most importantly, there is no negative trend over time. By contrast to the general finding reported in Table 2, feelings of efficacy thus prove to be stable in the course of scholarly research so far.10

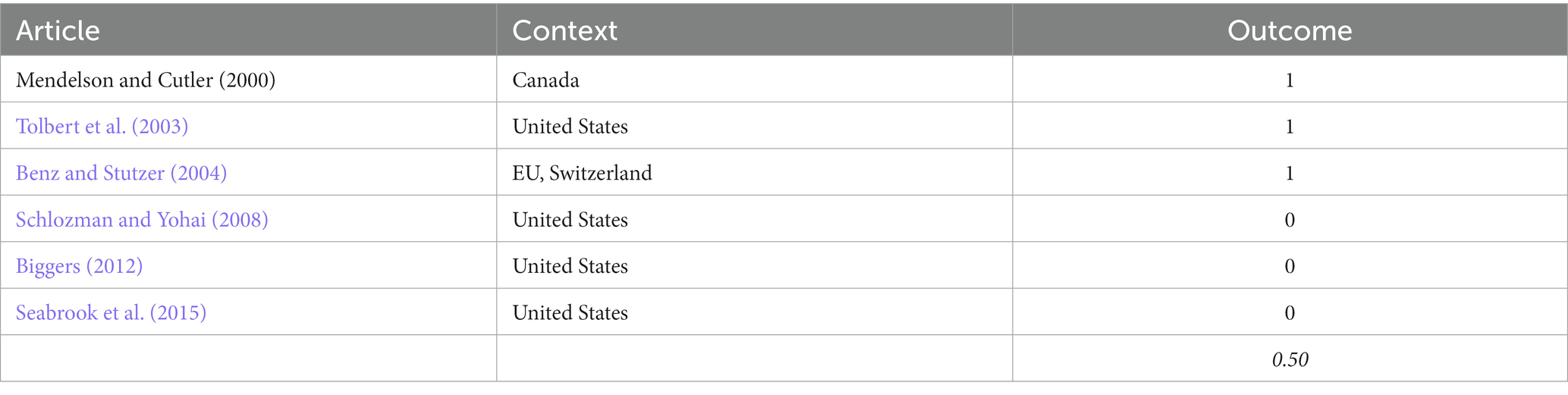

There are only six studies that focused on the civic virtue of political knowledge in the selection at hand (see Table 5). Nevertheless, three main provisory conclusions can be drawn from these empirical analyses. First, scholars seem to have focused on general political knowledge, thus leaving aside issue-specific considerations. The only exception concerns the Canadian study on the 1992 Charlottetown Accord (Mendelsohn and Cutler, 2000). Second, the state-of-the-art is characterized by balanced results in general. Indeed, three studies each find statistically positive effects or insignificant effects (mean = 0.5). Third, there may be a strong negative tendency, given that the three most recently published analyses report significantly negative effects of direct democracy on political knowledge levels (Schlozman and Yohai, 2008; Biggers, 2012; Seabrook et al., 2015). Thus, initial optimism provided by Benz and Stutzer (2004), Mendelsohn and Cutler (2000), and Tolbert et al., 2003 seems to have faded away.

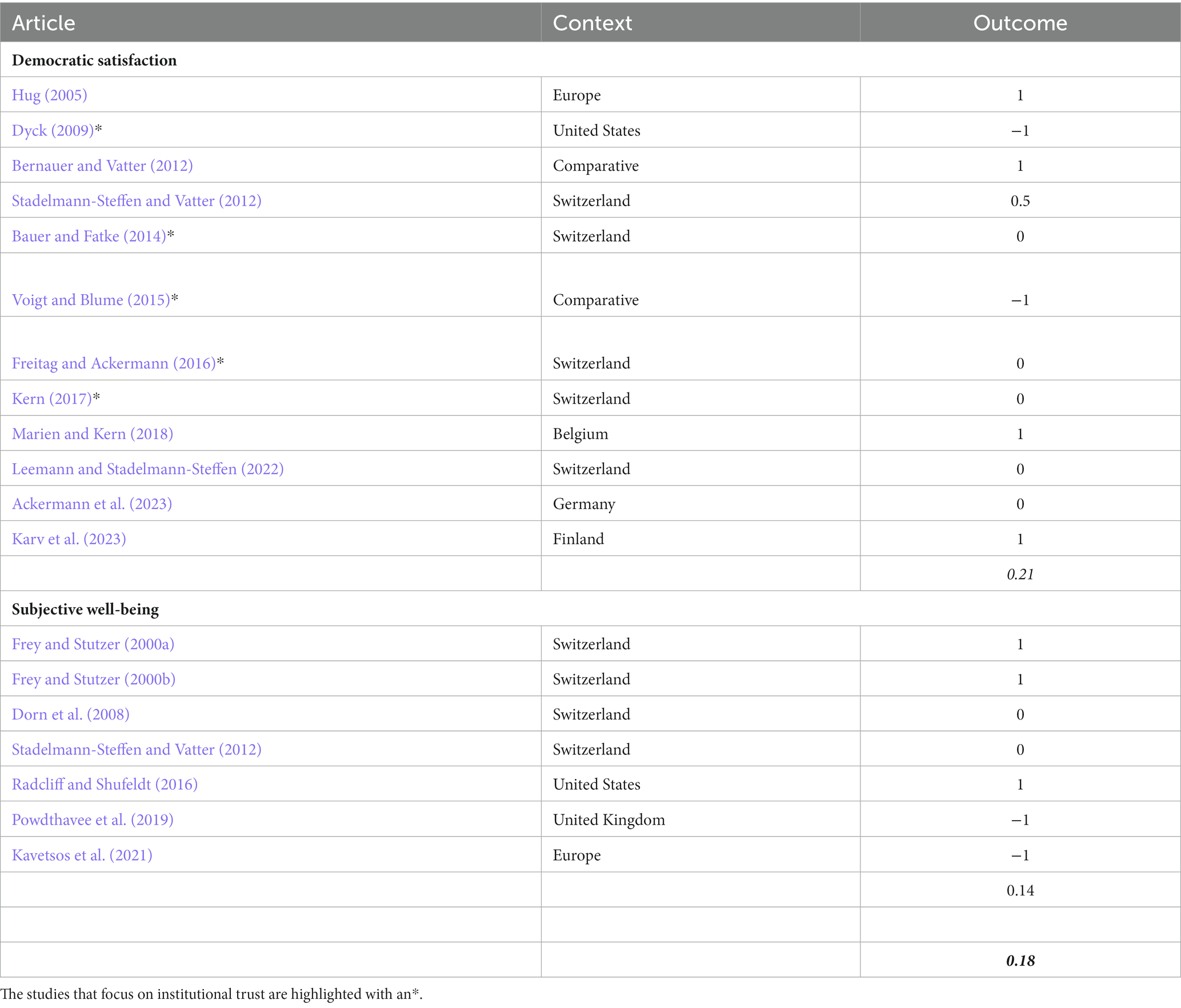

The overview of civic virtues related to individual and collective satisfaction is shown in Table 6. There is a high degree of concentration in geographical terms. Among the 19 selected studies, 9 focused on Switzerland and another 6 on other European countries more generally, whereas the remaining 4 studies refer to the United States as well as to comparisons that include at least two continents (2 each). Altogether, the effect direction proves to be rather narrowly on the positive side (mean = 0.18). In this context, it is important to note that there are no less than four studies that established significantly negative effects (i.e., Dyck, 2009; Voigt and Blume, 2015;Powdthavee et al., 2019; Kavetsos et al., 2021).

The comparatively low average scores apply to both collective (0.21) and individual dimensions of satisfaction (0.14). Yet, there is a marked difference within the former category. In general, the direct-democratic effects on institutional trust are much more negative (−0.40) than for political support and democratic satisfaction (0.64). As to subjective wellbeing, a negative time trend can be observed. The findings by Frey and Stutzer (2000a, 200b), according to which the degree of direct democracy fosters individual happiness, were subsequently challenged as far as the Swiss context is concerned (Dorn et al., 2008; Stadelmann-Steffen and Vatter, 2012) but confirmed for the United States (Radcliff and Shufeldt, 2016). Most recently, two studies on Brexit showed using panel data that this crucial vote led to a significant decrease in subjective wellbeing in the United Kingdom (Powdthavee et al., 2019; Kavetsos et al., 2021).

Conclusion

In the context of the current crisis of representative democracy, many citizens strive to decide the fate of major issues themselves through the adoption of direct-democratic institutions. In line with this demand, the number of referendums and initiatives has substantially increased across liberal democracies over recent decades. This has provided scholars with numerous opportunities to study whether these participatory devices have the potential to restore legitimacy. While direct democracy seems to have basically delivered on its instrumental promises related to policy-related outcomes (primary effects), the state-of-the-art on the secondary effects (i.e., normatively desired actor behavior and attitudes beyond policies) can probably best be described as inconclusive.

This article aimed to shed light on the subject by conducting a systematic literature review on the effects of direct democracy on four civic virtues: (1) electoral turnout, (2) external and internal efficacy, (3) political knowledge, and (4) subjective wellbeing and satisfaction with democracy. Based on a selection of 67 studies that empirically analyzed the effects of these associations, this article established only little beneficial effects on average with a great deal of variation. In addition, this review showed that scholars increasingly reported negative findings over time. This tendency applies to all selected civic virtues except for the studies on both internal and external efficacy.

If this review had been published 15 years ago, it almost certainly would have concluded on an optimistic note, stating that direct democracy can be considered a promising institutional device to promote civic virtues. Yet, the strong negative time trend calls into question the key argument put forward by theorists of participatory democracy, according to which referendums and initiatives empower and enlighten citizens. By contrast, it gives some credit to more skeptical views on the merits of direct democracy regarding secondary spillover effects. Alternatively, the negative time trend reported here may be linked to a general decline in terms of democratic quality, as a reviewer observed. This implies that it would be more difficult for direct democracy to deliver on its promises under such deteriorating conditions. This article has brought some further insights to light. Analyses that examined the lower levels of government were found to be more likely to arrive at more positive conclusions. In addition, the empirical contributions on the United States turned out to be significantly more optimistic than the Swiss studies. Yet, most of this discrepancy can be attributed to studies on electoral turnout, which may be a result of diverging practices in these two countries when it comes to the concurrent scheduling of elections and referendums.

In light of the main findings of this review, I would like to suggest some avenues for research. Given that it is not settled whether direct democracy leads to an increase in civic virtues, more research is obviously needed. This is exemplified by the fact that the number of analyzed relationships in this review only amounts to 67.11 Although scholars have increasingly relied on large-scale international comparisons and more systematic and encompassing analyses (e.g., by including several data sources or various ballots) in recent years, there is still a lot of potential. Perhaps, except for electoral turnout, this article suggests that there is little conclusive evidence at the level of single individual civic virtues. Since this review covered the most studied areas so far, the call for more empirical contributions on other virtues seems all too evident. This would allow complementing existing findings on various domains such as political interest (Ladner and Fiechter, 2012; Freitag and Zumbrunn, 2022), social trust (Dyck, 2012), tax morale (Torgler, 2005; Hug and Spörri, 2011), and forms of political engagement that go beyond electoral participation such as associational engagement (Freitag, 2006; Boehmke and Bowen, 2010; Stadelmann-Steffen and Freitag, 2011) and new forms of deliberative citizen participation (Ladner and Fiechter, 2012).

Based on the main results of this review, it would not be surprising to observe that mixed findings emerge from such additional studies. In the absence of clear-cut evidence, scholars may be well advised to increasingly take into consideration the conditions under which direct democracy exerts a positive or negative effect on a given civic virtue. In other words, they may more systematically look at possible interaction effects. A couple of studies suggest that mediating factors at both the contextual and individual levels can be at play. These may range from the type of direct-democratic institutions (Altman, 2013) to electoral contexts (Childers and Binder, 2012), over-issue characteristics (Biggers, 2011, 2012), population diversity (Dyck, 2012), and personality traits (Freitag and Zumbrunn, 2022).

This review has found that the academic literature is dominated by two country contexts: the United States and Switzerland. With the global increase in direct-democratic votes in recent decades, it would be appropriate for researchers to increasingly devote their attention to other political systems in which direct democracy has been traditionally less established. Following the Swiss and U.S. studies, cross-sectional analyses could be conducted at the subnational level in countries characterized by variations in terms of the existence or the extent of democracy (see Ackermann et al., 2023 for such an analysis on the states of Germany). From a longitudinal perspective, however, it would seem appropriate, from a researcher’s point of view, to focus on those jurisdictions characterized until recently by an (almost complete) absence of referendums and that have experienced a recent significant increase. This would make it possible to conduct change analyses in which the development of citizens’ civic virtues before and after direct democracy took off could be studied. According to the C2D database (available at http://www.c2d.ch), country contexts that meet these criteria include Lithuania, Mexico, the Netherlands (at least up to 2018), Slovakia, Slovenia, and Taiwan, as far as referendums at the national level are concerned.

In addition, it may be promising to focus on comparisons across direct-democratic systems. Indeed, this review has shown that this kind of approach has so far been neglected in the literature (Altman, 2013 being an exception). This is all the more regrettable as comparative studies have shown that direct-democratic institutions and practices can vary substantially across political contexts (Altman, 2019). At the same time, the present article has also revealed that studies on the subnational level in general and on the local level in particular tended to yield rather positive effects. However, empirical research proves to be particularly scant when it comes to studies on municipalities (and equivalents). Hence, the local level can be regarded as another blind spot of the academic literature that would need some enlightenment in the near future when it comes to examining the merits of direct democracy in general and in terms of individual civic virtues in particular.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

LB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2024.1287330/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^For instance, such a search query resulted in slightly more than 30,000 articles on Web of Science.

2. ^In this context, I need to mention that ‘support’ would have led to a far too large pre-selection of articles. By contrast, the more specific search term ‘democratic support’ did not lead to any additional study and was therefore not used here.

3. ^Political knowledge may go far beyond factual knowledge indeed. It may include, for instance, conceptual and procedural knowledge, both of which would probably require more advanced measures such as sophistication and competence.

4. ^Given that it turned out that the relevant articles appeared among the first entries, I decided to stop my screening after having looked at 500 of the 21,600 documents search results.

5. ^At the level of subcategories, 18% looked at democratic satisfaction, whereas 10% each were concerned with subjective wellbeing, external efficacy, as well as with internal efficacy.

6. ^On a methodological note, scholars have employed various operationalizations of direct democracy. Generally speaking, there is a distinction between the availability and the use of direct-democratic devices, whereas both are measured in a dichotomous or continuous way.

7. ^Rather positive (code 0.5) and rather negative effects (code −0.5) refer to studies that report varying direct results of direct democracy on civic virtues in terms of statistical significance that nevertheless point in a direction (i.e., either positive or negative effects). An example for coding 0.5 is an empirical analysis that uses two measures of direct democracy (e.g., the use and the availability of referendums) and finds a significant positive effect for a one of the two measures on a given civic virtue as well as a insignificant effect for the other one (e.g., the use of referendums). In such a case, it seems appropriate to use the code 0.5, given that there is a positive (1) and an insignificant outcome (0) at the same time.

8. ^When introducing an interaction term between ‘Switzerland’ and ‘Turnout’ into Model 1, it turns out that significant coefficient for ‘Switzerland’ vanishes, while the interaction term proves to be significantly negative at the 1% error level.

9. ^In this context, a reviewer rightly pointed out that the Swiss experience has shown that participation on ballot measures is better considered systematically and not on the basis of individual votes. Over the duration of an entire legislative term, electoral turnout has been found to be not necessarily lower in Switzerland than in comparable countries without direct democracy (Serdült, 2013).

10. ^In line with this impression, a significantly positive interaction term between efficacy and the year of publication can be detected in an additional model of the overall multivariate analysis (not shown here). This finding indicates that the general negative trend over time is less pronounced when it comes to studies on both internal and external efficacy.

11. ^At this point, it must be emphasized that this analysis is limited to journal articles in English, a standard practice when it comes to systematic literature reviews. Hence, there is no doubt that important additional insights can be gained from further forms of publication and contributions written in other languages.

References

Ackermann, K., Braun, D., Fatke, M., and Fawzi, N. (2023). Direct democracy, political support and populism–attitudinal patterns in the German Bundesländer. Reg.Fed. Stud. 33 , 139–162. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2021.1919876

Altman, D. (2013). Does an active use of mechanisms of direct democracy impact electoral participation? Evidence from the U.S. states and the Swiss cantons. Local Gov. Stud. 39 , 739–755. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2012.679933

Altman, D. (2019) Citizenship and contemporary direct democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barankay, I., Sciarini, P., and Trechsel, A. H. (2003). Institutional openness and the use of referendums and popular initiatives: evidence from Swiss cantons. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 9 , 169–199. doi: 10.1002/j.1662-6370.2003.tb00404.x

Barber, B. R. (2003). Strong democracy: Participatory politics for a new age. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bauer, P. C., and Fatke, M. (2014). Direct democracy and political trust: enhancing trust, initiating distrust–or both? Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 20 , 49–69. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12071

Benz, M., and Stutzer, A. (2004). Are voters better informed when they have a larger say in politics? Evidence for the European Union and Switzerland. Public Choice 119 , 31–59. doi: 10.1023/B:PUCH.0000024161.44798.ef

Bernauer, J., and Vatter, A. (2012). Can't get no satisfaction with the Westminster model? Winners, losers and the effects of consensual and direct democratic institutions on satisfaction with democracy. Eur J Polit Res 51 , 435–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.02007.x

Bessen, B. R. (2020). Rejecting representation? Party systems and popular support for referendums in Europe. Elect. Stud. 68 :102219. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102219

Biggers, D. R. (2011). When ballot issues matter: social issue ballot measures and their impact on turnout. Polit. Behav. 33 , 3–25. doi: 10.1007/s11109-010-9113-1

Biggers, D. R. (2012). Can a social issue proposition increase political knowledge? Campaign learning and the educative effects of direct democracy. Am. Politics Res. 40 , 998–1025. doi: 10.1177/1532673X11427073

Boehmke, F. J., and Bowen, D. C. (2010). Direct democracy and individual interest group membership. J. Polit. 72 , 659–671. doi: 10.1017/S0022381610000083

Bowler, S., and Donovan, T. (2002). Democracy, institutions and attitudes about citizen influence on government. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 32 , 371–390. doi: 10.1017/S0007123402000157

Bowler, S., and Donovan, T. (2019). Perceptions of referendums and democracy: the referendum disappointment gap. Polit. Govern. 7 , 227–241. doi: 10.17645/pag.v7i2.1874

Brüggemann, S., Gut, R. T., Serdült, U., and Wüthrich, J. (2023). The world of referendums: 2023 edition. Aarau: Zentrum für Demokratie Aarau (ZDA).

Cain, B. E., Dalton, R. J, and Scarrow, S. E. (2003). Democracy transformed? The expanding opportunities in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cebula, R. J. (2008). Does direct democracy increase voter turnout? Evidence from the 2004 general election. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 67 , 629–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1536-7150.2008.00590.x

Cebula, R. J., and Coombs, C. K. (2011). The influence of the number of statewide legislative referendums on voter participation in the US. Appl. Econ. 43 , 2823–2831. doi: 10.1080/00036840903389820

Childers, M., and Binder, M. (2012). Engaged by the initiative? How the use of citizen initiatives increases voter turnout. Polit. Res. Q. 65 , 93–103. doi: 10.1177/1065912910388191

Dorn, D., Fischer, J. A., Kirchgässner, G., and Sousa-Poza, A. (2008). Direct democracy and life satisfaction revisited: new evidence for Switzerland. J. Happiness Stud. 9 , 227–255. doi: 10.1007/s10902-007-9050-9

Dvořák, T., Zouhar, J., and Novák, J. (2017). The effect of direct democracy on turnout: voter mobilization or participatory momentum? Polit. Res. Q. 70 , 433–448. doi: 10.1177/1065912917698043

Dyck, J. J. (2009). Initiated distrust: direct democracy and trust in government. Am. Politics Res. 37 , 539–568. doi: 10.1177/1532673X08330635

Dyck, J. J. (2012). Racial threat, direct legislation, and social trust: taking tyranny seriously in studies of the ballot initiative. Polit. Res. Q. 65 , 615–628. doi: 10.1177/1065912911404562

Dyck, J. J., and Lascher, E. L. (2009). Direct democracy and political efficacy reconsidered. Polit. Behav. 31 , 401–427. doi: 10.1007/s11109-008-9081-x

Dyck, J. J., and Lascher, E. L. (2019). Initiatives without engagement: A realistic appraisal of direct Democracy’s secondary effects. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Dyck, J. J., and Seabrook, N. R. (2010). Mobilized by direct democracy: short-term versus long-term effects and the geography of turnout in ballot measure elections. Soc. Sci. Q. 91 , 188–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00688.x

Fatke, M. (2015). Participation and political equality in direct democracy: educative effect or social bias. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 21 , 99–118. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12127

Freitag, M. (2006). Bowling the state back in: political institutions and the creation of social capital. Eur J Polit Res 45 , 123–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2005.00293.x

Freitag, M., and Ackermann, K. (2016). Direct democracy and institutional trust: relationships and differences across personality traits. Polit. Psychol. 37 , 707–723. doi: 10.1111/pops.12293

Freitag, M., and Stadelmann-Steffen, I. (2010). Stumbling block or stepping stone? The influence of direct democracy on individual participation in parliamentary elections. Elect. Stud. 29 , 472–483. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2010.04.009

Freitag, M., and Zumbrunn, A. (2022). Direct democracy, personality, and political interest in comparative perspective. Politics 2633957221074897:026339572210748. doi: 10.1177/02633957221074897

Frey, B. S. (1997). A constitution for knaves crowds out civic virtues. Econ. J. 107 , 1043–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.1997.tb00006.x

Frey, B. S., and Stutzer, A. (2000a). Happiness, economy and institutions. Econ. J. 110 , 918–938. doi: 10.1111/1468-0297.00570

Frey, B. S., and Stutzer, A. (2000b). Maximising happiness? Ger. Econ. Rev. 1 , 145–167. doi: 10.1111/1468-0475.00009

Grummel, J. A. (2008). Morality politics, direct democracy, and turnout. State Polit. Pol. Quart. 8, 282–292. doi: 10.1177/153244000800800304

Gundelach, B., and Fatke, M. (2020). Decentralisation and political inequality: a comparative analysis of unequal turnout in European regions. Comp. Eur. Polit. 18 , 510–531. doi: 10.1057/s41295-019-00197-y

Gusenbauer, M., and Haddaway, N. R. (2020). Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews of meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res. Synth. Methods 11 , 181–217. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1378

Hadjar, A., and Beck, M. (2010). Who does not participate in elections in Europe and why is this? A multilevel analysis of social mechanisms behind non-voting. Eur. Soc. 12 , 521–542. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2010.483007

Hajnal, Z. L., and Lewis, P. G. (2003). Municipal institutions and voter turnout in local elections. Urban Aff. Rev. 38 , 645–668. doi: 10.1177/1078087403038005002

Hero, R. E., and Tolbert, C. J. (2004). Minority voices and citizen attitudes about government responsiveness in the American states: do social and institutional context matter? Br. J. Polit. Sci. 34 , 109–121. doi: 10.1017/S0007123403000371

Hug, S. (2005). The political effects of referendums: an analysis of institutional innovations in eastern and Central Europe. Communis. Post-Commun. 38 , 475–499. doi: 10.1016/j.postcomstud.2005.09.006

Hug, S., and Spörri, F. (2011). Referendums, trust, and tax evasion. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 27, 120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2010.06.005

Karv, T., Backström, K., and Strandberg, K. (2023). Consultative referendums and democracy-assessing the short-term effects on political support of a referendum on a municipal merger. Local Gov. Stud. 49 , 151–180. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2022.2047029

Kavetsos, G., Kawachi, I., Kyriopoulos, I., and Vandoros, S. (2021). The effect of the Brexit referendum result on subjective well-being. J. Royal Stat. Soc. Series A 184 , 707–731. doi: 10.1111/rssa.12676

Keele, L., Titiunik, R., and Zubizarreta, J. R. (2015). Enhancing a geographic regression discontinuity design through matching to estimate the effect of ballot initiatives on voter turnout. J. Royal Stat. Soc. Series A 178 , 223–239. doi: 10.1111/rssa.12056

Kern, A. (2017). The effect of direct democratic participation on Citizens' political attitudes in Switzerland: the difference between availability and use. Pol. Govern. 5 , 16–26. doi: 10.17645/pag.v5i2.820

Kim, T. (2015). The effect of direct democracy on political efficacy: the evidence from panel data analysis. Jap. J. Polit. Sci. 16 , 52–67. doi: 10.1017/S1468109914000383

Kostelka, F., Krejcova, E., Sauger, N., and Wuttke, A. (2023). Election frequency and voter turnout. Comp. Pol. Stud. 56, 2231–2268. doi: 10.1177/00104140231169020

LaCombe, S. J., and Juelich, C. (2019). Salient ballot measures and the millennial vote. Comp. Pol. Stud. 7, 198–212. doi: 10.17645/pag.v7i2.1885

Ladner, A., and Fiechter, J. (2012). The influence of direct democracy on political interest, electoral turnout and other forms of citizens’ participation in Swiss municipalities. Local Gov. Stud. 38 , 437–459. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2012.698242

Leemann, L., and Stadelmann-Steffen, I. (2022). Satisfaction with democracy: when government by the people brings electoral losers and winners together. Comp. Pol. Stud. 55 , 93–121. doi: 10.1177/00104140211024302

Leininger, A. (2015). Direct democracy in Europe: potential and pitfalls. Global Pol. 6 , 17–27. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12224

Lupia, A., and Matsuaka, J. G. (2004). Direct democracy: new approaches to old questions. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 7 , 463–482. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.7.012003.104730

Maduz, L. (2010). Direct democracy. Liv. Rev. Demo. 2 , 1–14. Available at: http://www.livingreviews.org/lrd-2010-1

Marien, S., and Kern, A. (2018). The winner takes it all: revisiting the effect of direct democracy on citizens’ political support. Polit. Behav. 40 , 857–882. doi: 10.1007/s11109-017-9427-3

Matsusaka, J. G. (2005). Direct democracy works. J. Econ. Perspect. 19 , 185–206. doi: 10.1257/0895330054048713

Mendelsohn, M., and Cutler, F. (2000). The effect of referendums on democratic citizens: information, politicization, efficacy and tolerance. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 30 , 669–698. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400220292

Peters, Y. (2016). Zero-sum democracy? The effects of direct democracy on representative participation. Polit. Stud. 64 , 593–613. doi: 10.1177/0032321715607510

Pharr, S. C., and Putnam, R. D. (2000). Disaffected democracies: What’s troubling the trilateral countries? Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Pitkin, H. F. (2004). Representation and democracy. Scand. Polit. Stud. 27 , 335–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2004.00109.x

Powdthavee, N., Plagnol, A. C., Frijters, P., and Clark, A. E. (2019). Who got the Brexit blues? The effect of Brexit on subjective wellbeing in the UK. Economica 86 , 471–494. doi: 10.1111/ecca.12304

Radcliff, B., and Shufeldt, G. (2016). Direct democracy and subjective well-being: the initiative and life satisfaction in the American states. Soc. Indic. Res. 128 , 1405–1423. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-1085-4

Schecter, D. L. (2009). Legislating morality outside of the legislature: direct democracy, voter participation and morality politics. Soc. Sci. J. 46 , 89–110. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2008.12.002

Schlozman, D., and Yohai, I. (2008). How initiatives don’t always make citizens: ballot initiatives in the American states, 1978–2004. Polit. Behav. 30 , 469–489. doi: 10.1007/s11109-008-9062-0

Seabrook, N. R., Dyck, J. J., and Lascher, E. L. (2015). Do ballot initiatives increase general political knowledge? Polit. Behav. 37 , 279–307. doi: 10.1007/s11109-014-9273-5

Serdült, U. (2013). “Partizipation als Norm und Artefakt in der schweizerischen Abstimmungsdemokratie: Entmystifizierung der durchschnittlichen Stimmbeteiligung anhand von Stimmregisterdaten aus der Stadt St. Gallen” in Direkte Demokratie: Herausforderungen zwischen Politik und Recht. eds. A. Good and B. Platipodis (Bern: Stämpfli), 41–50.

Smith, M. A. (2001). The contingent effects of ballot initiatives and candidate races on turnout. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 45, 700–706. doi: 10.2307/2669246

Smith, D. A., and Tolbert, C. J. (2019). Educated by initiative: The effects of direct democracy on citizens and political organizations in the American states. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Southwell, P. L., and Paaso, P. S. (2001). The relationship between voter turnout and ballot measures-a research note. J. Polit. Milit. Sociol., 275–281. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45293805

Stadelmann-Steffen, I., and Freitag, M. (2011). Making civil society work: models of democracy and their impact on civic engagement. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 40 , 526–551. doi: 10.1177/0899764010362114

Stadelmann-Steffen, I., and Vatter, A. (2012). Does satisfaction with democracy really increase happiness? Direct democracy and individual satisfaction in Switzerland. Polit. Behav. 34 , 535–559. doi: 10.1007/s11109-011-9164-y

Tolbert, C. J., Bowen, D. C., and Donovan, T. (2009). Initiative campaigns: direct democracy and voter mobilization. Am. Politics Res. 37 , 155–192. doi: 10.1177/1532673X08320185

Tolbert, C. J., Grummel, J. A., and Smith, D. A. (2001). The effects of ballot initiatives on voter turnout in the American states. Am. Politics Res. 29 , 625–648. doi: 10.1177/1532673X01029006005

Tolbert, C. J., McNeal, R. S., and Smith, D. A. (2003). Enhancing civic engagement: the effect of direct democracy on political participation and knowledge. State Polit. Policy Quart. 3 , 23–41. doi: 10.1177/153244000300300102

Tolbert, C. J., and Smith, D. A. (2005). The educative effects of ballot initiatives on voter turnout. Am. Politics Res. 33 , 283–309. doi: 10.1177/1532673X04271904

Tolbert, C. J., and Smith, D. A. (2006). Representation and direct democracy in the United States. Representation 42 , 25–44. doi: 10.1080/00344890600583743

Torgler, B. (2005). Tax morale and direct democracy. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 21 , 525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2004.08.002

Vatter, A., Rousselot, B., and Milic, T. (2019). The input and output effects of direct democracy: a new research agenda. Policy & Politics. 47 , 169–186. doi: 10.1332/030557318X15200933925423

Voigt, S., and Blume, L. (2015). Does direct democracy make for better citizens? A cautionary warning based on cross-country evidence. Constit. Polit. Econ. 26 , 391–420. doi: 10.1007/s10602-015-9194-2

Keywords: direct democracy, civic virtues, efficacy, happiness, knowledge, literature review, participation, satisfaction

Citation: Bernhard L (2024) Does direct democracy increase civic virtues? A systematic literature review. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1287330. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1287330

Edited by:

Raul Magni Berton, Université Grenoble Alpes, FranceReviewed by:

Davide Morisi, University of Southern Denmark, DenmarkZoltán Tibor Pállinger, Andrássy University Budapest, Hungary

Copyright © 2024 Bernhard. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laurent Bernhard, bGF1cmVudC5iZXJuaGFyZEB6ZGEudXpoLmNo

Laurent Bernhard

Laurent Bernhard