- 1Department of Political Science, University of Duisburg-Essen, Duisburg, Germany

- 2Department of Politics and International Affairs, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, United States

How do national models of solidarity shape public support for distinctive policy responses to social and economic crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic? We analyze American and German policy responses from March 2020 to June 2021 across a number of economic and social policy domains and identify path-dependent institutional contingencies in both countries despite the same crisis experience. Drawing from 10 different sources of public opinion data, we then triangulate the pandemic's effects on public support for individualized and collectively oriented policy responses. Aside from emotional rally-to-the-flag effects, the policy-specific public reactions are consistent with institutional and normative predicates of the two political economies: the German public seems to be supportive of aggressive policies to combat inequality, though in ways that privilege established social collectivities and groups, whereas in the U.S., we only see moderate evidence of support for time-limited and individually-focused measures designed to remain in place only for the duration of the crisis.

Introduction

How do national models of solidarity shape public support for policy responses to social and economic crises? The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare the limitations of models of economic governance across the advanced industrial world, including gaps in national systems of social protection, over-reliance on social benefits derived from labor-market relationships, and the effects of decades of underinvestment in educational and vocational-training systems. In the process, it has highlighted trends that long predate it, discrediting the long-held neoliberal nostrum that limited states and an expansive scope for market forces lead inexorably to generalized economic prosperity. It has also shown the need to revisit the question of social solidarities and norms of community and mutual support that inform prevailing conceptions of economic citizenship, as well as expectations of the scope and character of state involvement in the economy. In the process, it has brought renewed attention to the origins and effects of nationally distinctive social-protection institutions, which now more than ever seem essential to the capacity of capitalist economies and their citizenries to adjust to shifting social and economic challenges.

Using COVID-19 pandemic as a signal case, we investigate how the acute uncertainties occasioned by such shocks reshape citizens' capacity for empathy and mutual support, their willingness to sacrifice for the sake of societal welfare, and their support for particular kinds of collective responses that enjoy broad legitimacy and reflect a shared sense of public purpose. In so doing, we draw analogies with other kinds of national trauma, such as wars, which have historically transformed both patterns of social solidarity and support for an expansion of government's role, as with the creation of a comprehensive British welfare state in the aftermath of World War II. We present systematic public-opinion data and tie public views to policy initiatives undertaken by advanced industrial states in order to show how, and the extent to which, public policies have garnered support and how patterns of policy interventions have varied cross-nationally. In the process, we also generate broader insights about how historical episodes that generate massive increases in economic insecurity inform distinctive collective understandings and support particular patterns of economic governance. In so doing, we move beyond prevailing institutionalist and rationalist approaches to investigate the sources of existing institutional and policy frameworks in public opinion and prevailing public discourses related to work, fairness, the economic role of the state, and the meaning of economic citizenship and solidarity. This means treating existing institutional frameworks, not as analytical points of departure, but rather as expressions of underlying public norms and models of solidarity of which both they and the character of policy responses to economic shocks are expressions.

We focus on Germany and the United States, countries with widely divergent modes of integration of capitalist markets, differential levels of state capacity, distinctive systems of social protection, and starkly different institutionalized relationships between capital and labor. Attention to these differences allows us to explain how interactions between social-protection arrangements and related labor-market institutions inform public expectations of government and support for a range of policy responses to COVID-19. Such distinctions between the American and German models, and by extension, liberal and mixed economies more generally, have been analyzed in decades of research, from the comparative-welfare-state literature (Esping-Andersen, 1990) to the well-known distinction between “liberal” and “coordinated market economies” advanced by the “Varieties-of-Capitalism” literature (Hall and Soskice, 2001). However, we go beyond them in analyzing broad patterns of social solidarity and attendant models of economic governance, focusing on the state as a key variable, with particular emphasis on how prevailing conceptions of social obligation, shared by both elites and mass publics, support distinctive patterns of state intervention. We trace American and German policy responses between March 2020 and July 2021, the period during which the key policy responses to the pandemic were crafted, across a number of policy domains, including social protection, financial assistance to firms, tax breaks for individuals and families, and fiscal-stimulus initiatives. We then undertake systematic analysis of public opinion in Germany and the U.S. about such initiatives and broader questions of trust, inequality, and solidarity. This comparative case-study approach furthers our understanding of causal mechanisms at work in these two country contexts, moving beyond the mere observation of “models” to key social and discursive mechanisms that sustain them over time.

We argue that differing conceptions of public purpose and models of solidarity have led to distinctive patterns of public support for both state action in general and policy responses. In both countries, the emotional trauma wrought by the pandemic led to a marked increase in public trust of government and public officials. At the same time, the policies supported by the public varied significantly with levels of economic embeddedness and the degree of institutionalization of economic relationships. In the U.S., where such relationships are much more disembedded and atomized, public discourse reflects a more individualized conception of social organization, and social trust and cohesion have been undermined by partisan and ideological battles, public and elite support has coalesced behind particularistic and palliative benefits aimed at individuals and affected firms. In Germany, by contrast, both the public and elites have favored policy instruments that support strategically important groups, such as skilled labor and firms in export-intensive industries, supported by a more robust conception of social purpose and mutual reliance and aiming proactively to prevent or minimize social and economic dislocation. These patterns of public opinion and institutional configurations both reflect and reinforce distinctive models of social solidarity. In Germany, this model tends to reflect a greater sense of shared public purpose and collective welfare, focused upon the economic fortunes of key groups in the economy, within which a sense of shared identity tends to cohere. In the U.S., by contrast, a much more individualistic conception of deservingness, effort, and responsibility undermines such collective identities, and, with it, support for government initiatives in the service of a sense of shared public purpose. These differential responses and the models of solidarity that underpin them carry with them distinctive sets of life chances for workers, for whom structural economic and power inequalities are both symptoms and reinforcing causes of nationally distinctive social contracts.

In the next section, we develop our theoretical framework, which synthesizes sociological and historical conceptions of capitalism with “moral-economy” understandings of fairness and associated patterns of public opinion. We then present an overview of German and American policy responses to the pandemic, highlighting characteristic differences. Then, we present a second set of empirical data, connecting patterns of public opinion in the two countries to levels of social trust and support for particular policy interventions. We end by exploring the theoretical significance of our findings and speculating about their implications for other episodes of national trauma.

From embeddedness to public purpose and solidarity: theoretical underpinnings of responses to economic crisis

The epidemiological and economic shock of the COVID-19 pandemic was equally a social and political one, unsettling conventional wisdoms about the relationship between the state and the market. As such, it presents an opportunity to analyze the relationship between public support for social and economic policies designed to buffer workers, and norms relating to social solidarity and mutual support among citizens. Our theoretical point of departure is that the degree of social cohesion, involving horizontal bonds among citizens, shapes citizens' attitudes toward and trust in the state. In investigating patterns of change in both of these contexts, we shed light on how periods of heightened economic uncertainty and trauma shape the structure and cohesiveness of social bonds and public support for evolving models of economic governance. Thus, we work to connect, theoretically and empirically, patterns of social cohesion and embeddedness to the possibilities for a congruent conception of public purpose between the public and governing elites.

Theoretical approaches to systemic reactions to crises

In developing our macro-level theoretical framework, we build upon two distinctive scholarly traditions. The first entails work on the comparative historical sociology of capitalism, exemplified in the work of Polanyi (1957, 2001). Polanyi provides a sociological conception of the emergence of capitalism, demonstrating that a “market society” was a deliberate construction of the state constrained by limitations to the commodification of labor. Prior to the beginning of the process of market construction in the 18th century, economic life was informed by the older norms of reciprocity and redistribution, informing such practices as sharing among kinship groups, in contrast to the transactional norms that emerged subsequently (Polanyi, 1957). The implication is that the norms that govern patterns of adjustment to economic disruption are informed by deep structures of human solidarity that legitimate particular patterns of state economic engagement and attendant policy expectations. This idea suggests in turn that differently constituted political economies, with varying historical patterns of economic relationships among groups and between groups and the state, will generate different public expectations and support for policy responses.

Polanyi's emphasis upon the socially embedded character of capitalist economic relations provided a touchstone for critiques of the neoliberal, market-based orthodoxies since the 1970s. Granovetter (1985), for example, brought similar insights to bear on contemporary economic debates over the appropriate and feasible scope of market arrangements in advanced industrial economies. He argues that even highly modern forms of economic life, the level of economic embeddedness “has always been and continues to be more substantial than allowed by economists and formalists” (Granovetter, 1985, p. 483). Economic sociologists locate the foundations of capitalist economies in the social relationships on which market transactions ultimately rely, a view at odds with the transactional and atomized conception of human beings central to classical models. While Polanyi's account is more developmentalist than Granovetter's, they share a key conviction that is central to our approach: that economic and social relations are co-constitutive, and that individuals' capacity to support collective economic endeavors is tied to the extent and character of social embeddedness. In this way, economic activity is understood, not merely as a matter of individual initiative, but also as part of a broader pattern of engagement in which citizens derive support from one another and the state.

The second, related, body of scholarship that informs our analytical framework seeks to historicize and identify mechanisms that govern workers' individual and collective responses to disruptive economic change. The “moral-economy” literature, exemplified in the work of Thompson (1964), grew out of the “New Left” including scholars such as Stuart Hall and Ralph Milliband, who contended that “culture and ideology had become as important as class” (Menand, 2021, p. 49). Thompson (1971, p. 79) argues that “a moral economy … suppose[s] definite, and passionately held, notions of the common weal…a consistent traditional view of social norms and obligations, of the proper economic functions of several parties within the community”.

Such scholarship provides powerful tools for understanding contemporary public and élite reactions to the devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic (for a similar approach, see Koos and Sachweh, 2019). In like fashion, we seek to understand how differing degrees of social embeddedness, and the horizontal ties—both actual and notional—that constitute them inform public trust in government and support for particular kinds of policy responses. This leads to our first of five theoretical expectations, which establishes a broad theoretical framework for the micro-level propositions described subsequently.

Proposition #1: Individuals are connected to the market in nationally distinctive ways, and differing patterns of social embeddedness generate divergent expectations of the state.

Taken together, these literatures generate different expectations regarding citizens' responses to exogenous shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast to economistic models of atomized individuals, they posit a deeply socially embedded frame, within which individuals act within social contexts and are willing to constrain their individual prerogatives for the sake of collective welfare. Relatedly, they lead one to expect that societies with different constellations of political and social arrangements will respond differently to such shocks, in terms of both citizens' willingness to acknowledge the importance of societal benefit and their expectations of the character and extent of state support.

Micro-level approaches to the nexus between politics and public opinion

We now consider the mechanisms that inform individuals' reactions to collective shocks. The sudden onset of COVID-19, and the resulting epistemological and narrative instability across both mass publics and elites, provides potentially fertile ground on which to assess the effects of such shocks on social cohesion, trust and support for social and economic policies. Whereas our knowledge about political and social institutions guides our expectations about what governments might be expected to do, we must turn to public-opinion research to understand how the public reacted in these two countries and how such reactions shaped state responses.

In theory, it is possible to differentiate between the public's reactions to the pandemic itself and to policy responses to deal with it, by asking questions about both the pandemic itself and government measures. In practice, however, this proves to be more difficult, as there is a significant time lag between sudden events and their effects on public polling.1

A rich scholarly literature about crises and their effects on public opinion provides guidance about how to understand crises that cannot be easily attributed to broader problems with society, government, or the economy, with much longer gestational periods and time horizons. Whereas, in such instances, citizens' attitudes about crises are shaped by their assessment of the perceived underlying problems (Goerres and Walter, 2016), we focus instead on public-opinion reactions to pandemics and other similar catastrophes, such as wars and natural disasters.

There is robust evidence for a unifying effect of external shocks in support of the executive and incumbent governments and administrations. Such “rally” effects can be seen after military conflicts, assuming the presence of some media attention. The micro-level mechanism is that those who are ambivalent about the executive tend to increase support for government (Baker and Oneal, 2001; Baum, 2002). Elite criticism of government immediately after the onset of a crisis is often less prevalent in the media (Groeling and Baum, 2008), and citizens perceive a stronger elite consensus in such contexts and adjust their attitudes accordingly.

The individual reactions that lead to such effects are driven by powerful emotions. Threats trigger anxiety and the desire for security, which citizens often seek from public officials and institutions (Pierce, 2021). Some psychological theories emphasize humans' yearning for a world that is predictable and secure (Lambert et al., 2011). Although military conflicts are the most-studied trigger of a rally-around-the-flag effect, similar effects can be observed in the affirmation of in-group memberships in response to perceptions of threats from outgroups. In other words, perceptions of threats and insecurity tend to generate expectations of both the state and fellow citizens, and the effects of such dynamics extend beyond policies to social behavior more generally. Altruism with respect to one's in-group seems closely tied to conflict and catastrophe (Bowles, 2008). That said, one should expect different kinds of public reactions and different levels of support for policies that reflect and reinforce distinctive conceptions of social solidarity.

Proposition #2: The onset of pandemics will increase support for incumbents and political trust in government in the short run.

Wars have been shown to create prosocial behavior at the individual level (Bauer et al., 2016) and to encourage burden-sharing and institution-building at the collective level (Obinger and Petersen, 2017). The collective experience of hardship during war seems to lead to a logic of “we share the burden, we share resources” (see Titmuss, 2019, ch. 4). COVID-19 was not a war, but it had some characteristics that remind us of wartime experiences. For example, COVID-19 was potentially deadly for millions with unknown consequences for citizens' long-term health. Increases in prosocial behavior was a plausible expectation, as the economic devastation wrought by the pandemic far exceeded the coping capacity of individuals or even significant social groups. The traumatic experience of COVID-19 might also lead to altered preferences and thus a higher level of prosociality reflected in social trust.

Proposition #3: Social trust will increase in both countries in the short run.

As with wars, in this scenario, citizens might support major government interventions related to health policy, as in the case of economic policy (Mizrahi et al., 2020). It would thus be plausible to expect citizens to grow accustomed to a more active role for government and for this effect to be more visible in the U.S., where baseline state capacity is weaker than in Germany. However, it remains unclear whether this shift in attitudes would be related primarily to the scope of government or, rather, to the intensity of its activities.

Proposition #4: With respect to social and economic policy, path-dependent cross-national policy divergence will develop, with increased support for highly individualized provisions in the U.S., in contrast to support for more collectively- or group-oriented policies in Germany.

Given the magnitude of the pandemic's shock to the two societies, it is reasonable to expect significant change in the policy priorities within their populations. However, the two countries differ significantly in the organization of their healthcare systems, a fact that would be consistent with different sets of expectations. In Germany, coverage of health insurance is quasi-universal, with funding burdens and managerial tasks shared between worker and employer representatives. The public-hospital system is robust, and the public-health infrastructure is well developed. In the United States, by contrast, despite the expansion of coverage resulting from the Affordable Care Act, coverage is spotty and incomplete and benefit terms are much less generous. Public hospitals are also fragmented and uneven in coverage, and public-health infrastructure is underdeveloped and underfunded, with widely varying capacities across states.

The pandemic should increase public concerns about unemployment, though the character of the concern and respective points of emphasis are unclear a priori. In Germany, normal unemployment insurance pays up to 67% of a worker's previous wage, with benefit duration scaled by age and time of employment but typically lasting at least a year. Thereafter, the less-generous “Hartz IV” benefit kicks in Vail (2010). In the United States, by contrast, unemployment insurance is limited to a few hundred dollars per week, varying significantly by state in generosity and terms of eligibility. Whereas German workers and employers view unemployment insurance as a benefit paid for through contributions over time, in the U.S. the benefit is heavily stigmatized and is contingent upon often-onerous job-search, reporting, and monitoring requirements (Herd and Moynihan, 2018). These policy and institutional differences are both possible drivers of distinct patterns of state intervention and historical artifacts of deeply rooted differences in public conceptions of politics and social organization.

The economic dislocation resulting from the pandemic leads one to expect social inequality to become more prominent in people's minds, though in ways shaped by these policy and institutional differences. The pandemic was much more difficult for people with fewer assets, who could not work remotely, and who were responsible for caring for children or dependent adults. Under such circumstances, it is reasonable to expect an increase in the salience of economic inequality, but it is less clear a priori how citizens socialized in these two systems would interpret and respond to it. Traditionally, the American public is much more tolerant of social inequality. Bénabou and Tirole (2006) relate this discrepancy to the prevalence of the belief that individuals and their children can succeed economically. It is thus reasonable to expect that the salience of social inequality would rise in both countries, but that the demand for government action will be limited in the U.S., as fewer citizens view government as a legitimate remedy to social problems.2 This reasoning leads us to our fifth and final proposition:

Proposition #5: Support for policy measures to reduce inequality will increase in Germany, but not in the U.S.

Research design and data

We look at two country-crisis episodes: the United States in 2019–2021 and Germany in 2019–2021. We concentrate on policy responses at the national level as a first set of reactions and on public opinion as a second. We also consider variation within that period over time. In each country, the challenges related to health, the labor market, and the economy were similar, but the reactions were quite different. We are thus echoing other comparative approaches to moral economies in which the two countries are often selected as representative of different welfare regimes (Sachweh and Olafsdottir, 2012) (see Supplementary Appendix A.1).

We explore the extent to which similar challenges were channeled differently in the two countries. Causally, we employ the logic of within-case designs, assuming that Germany in February 2020 is similar to Germany in January 2020, with the obvious difference that the first local infections of COVID-19 were discovered in February. The exogenous origin of the pandemic leads to the plausible assumption that a temporal change between January 2020 and subsequent periods can be attributed to COVID-19. However, we must be careful not to discount the difference between reactions to the pandemic and reactions to behavior by political actors. Thus, for instance, a rise in political trust after the onset of the pandemic might be a function of fears' being more prevalent in the population or, instead, of an appreciation of adopted policy measures.

We have collected extensive data, building on various efforts by other scholars (e.g., Bruegel, 2020; McCollum, 2020; Matthews, 2021) and on secondary usage of existing analyses. We also make use of ten commercial and scientific public opinion data sources, some of them with different surveys. All data are accessible to the public (Edelman Trust Barometer, More in Common, Politbarometer, Freiburger Politikpanel, Pew International), scientists (GESIS internet panel) or through available commercial databases (Kaiser Family Foundation, Gallup). The public-opinion data differ slightly in their sampling procedure (some use random sampling, some quota sampling, others convenience sampling) and their survey mode (phone, face-to-face, online) (see Supplementary Appendix A.2).

We use different indicators of public opinion to assess the relationship between citizens and the state and among citizens. We examine confidence in national government, trust in national government, support for the incumbent, social trust, and attitudes toward specific policies. All of these variables capture slightly different aspects of citizens' connections to the state or to other individuals. The objective of this triangulating kaleidoscope of public-opinion pieces is to paint a broad picture about changes attributable to the pandemic and attitudes toward policies adopted to fight it.

We can trace changes over time of some measures of public opinion and static snapshots of others. Given the observational nature of our data, we cannot distinguish whether changes over time were already anticipated by policy-makers when implementing these public policies.

Empirical analysis: public-policy responses to COVID-19 in Germany and the United States

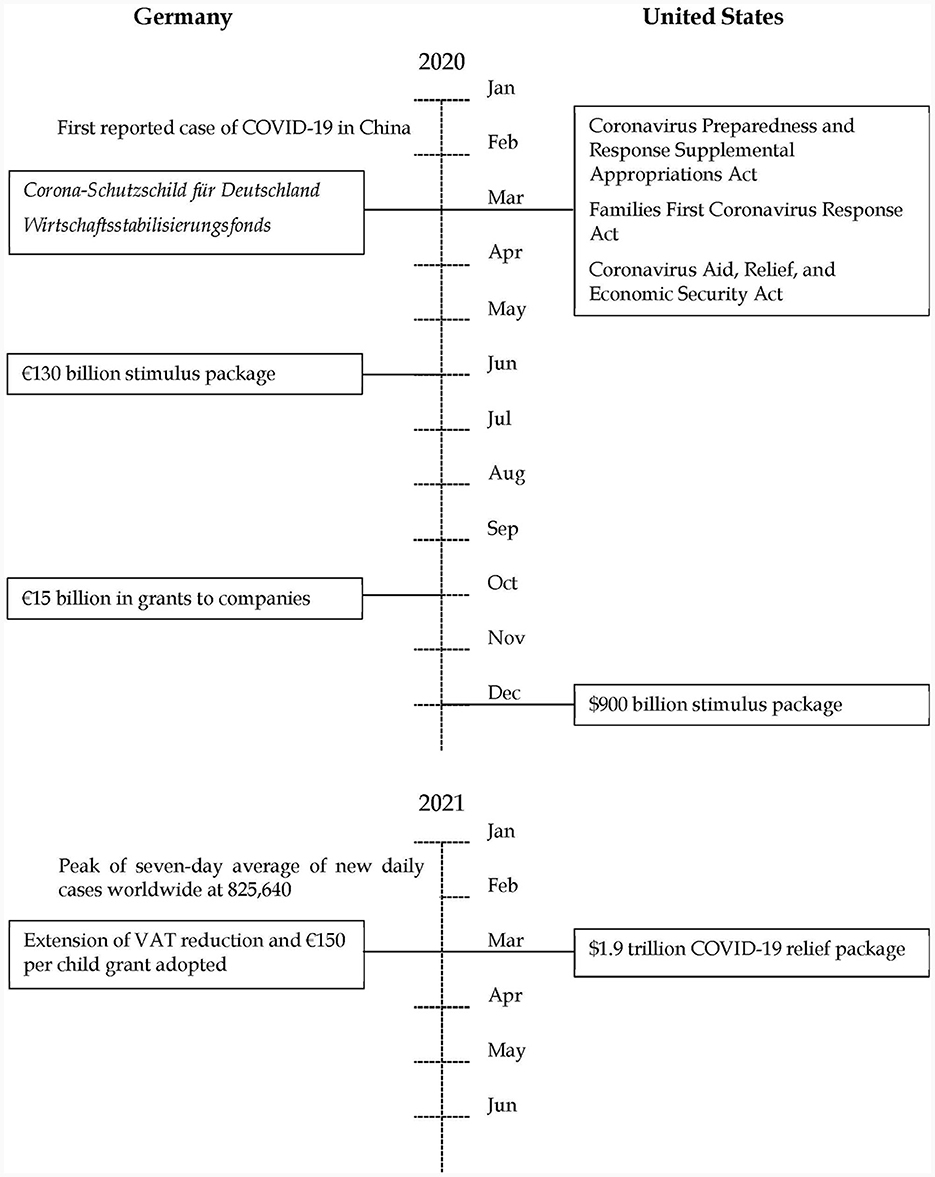

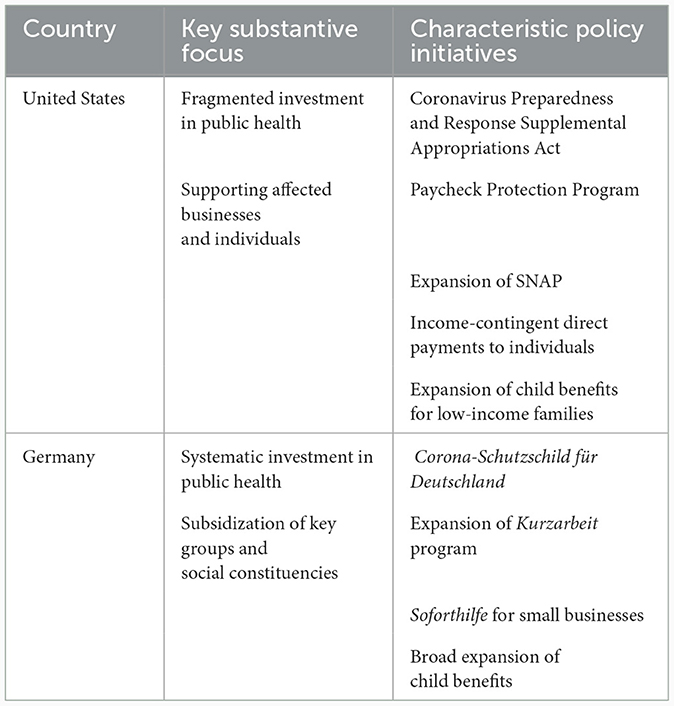

Like many advanced industrial countries, Germany and the United States rapidly deployed vast fiscal and administrative resources following the advent of COVID-19 in March 2020 and continued economic support into the summer of 2021. These measures included loan guarantees and payroll subsidies to businesses, investments in public infrastructure, and direct assistance (Figure 1).

In Germany, the scale of policy responses echoed that following reunification in 1990, when more than €2 trillion was spent over three decades (Vail, 2018). In the U.S., the response, involved a major deployment of state power and resources unmatched since the Great Depression, shifting the prevailing policy-making paradigm away from the small-government and neoliberal orthodoxies that even the post-2008 Great Recession had been unable to displace (Alter, 2021; Carter, 2021).

Both countries' fiscal- and economic-policy responses were breathtakingly ambitious. Including all discretionary spending until March 2021, the U.S. spent more than any other country (at 27.1% of GDP), while Germany's, at 20.3% of GDP, was seventh largest in the world (Matthews, 2021) (see Table 1).

Pre-empting dislocation in Germany: subsidizing business, supporting core workers and families, and bolstering public investment

Germany's economic-policy strategy in the wake of COVID-19 involved a combination of generous support for public-health initiatives and an extension of both direct and indirect support to core constituencies of the Social Market Economy, including industrial firms, small businesses, workers in key industries, and families. In late March 2020, Merkel's government announced two major initiatives to support economic activity and buffer disproportionately affected groups. The first, the so-called Corona-Schutzschild für Deutschland (Coronavirus Protective Shield for Germany), allocated €353.3 billion, including €3.5 billion for personal protective equipment (PPE) for hospitals and investments in vaccine development; €55 billion to remedy hospitals' and doctors' deteriorating finances and to provide support to families, including subsidies for lost earnings and extended access to family allowances; and €50 billion in so-called Soforthilfe (Immediate Assistance) for small businesses, freelancers, and the self-employed (Bundesfinanzministerium, 2021a). The second initiative, the Wirtschaftsstabilisierungsfonds (Economic Stabilization Fund), earmarked €891.7 billion for larger firms, particularly those with strategic economic importance. This measure included €400 billion in loan guarantees, €100 million for an assistance program for firms within the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) (a public development bank), and tax breaks and abatements to help firms clean up their balance sheets (Bundesfinanzministerium, 2021a).

The government also provided extensive support for workers, particularly those in manufacturing and key export sectors. The signal initiative in this category involved the so-called Kurzarbeitergeld, or “Short-time Work Program.” Originally created in the aftermath of German reunification and resuscitated in the wake of the Great Recession, these schemes allow at-risk workers to work reduced hours while receiving up to 90% of their previous pay, so as to avoid disruptive and costly layoffs. Between March and December 2020 alone, an additional €23.5 billion was spent on related programs (Bruegel, 2020). In a supplementary budget of €122.5 billion adopted in the same month, the government extended other forms of support to German workers, including an additional €7.7 billion for the second-tier assistance program for the unemployed.

In June 2020, the government adopted a second major stimulus package worth €130 billion that focused on tax relief to German firms and consumers and additional resources for families with children, long a core constituency of the post-war Social Market Economy. The two VAT rates were cut from 19 to 16% for the standard rate and 7 to 5% for necessities, such as groceries. The initiative also provided an additional €300-per-child bonus payment to families and more than doubled the income-tax exemption for single parents to €4,000. The package also extended a number of tax breaks, including subsidies for municipalities suffering from declining tax revenue and a 40% cap on social-security contributions. For firms, it increased depreciation allowances and created more generous provisions for declaring losses from previous tax years. Finally, the measure made significant investments in renewable energy and infrastructure, including investments in electric vehicles, battery-technology development, and the modernization of Germany's aging fleets of buses and commercial vehicles. In October, an additional €15 billion was provided for grants to companies, and in March 2021 an additional €150 per child was paid to families (Bundesfinanzministerium, 2021b). Although the EU invested significant funds in vaccine development and distribution, both public-health regulations and investments in economic-adjustment funding was undertaken largely on the national level. Although some of the funding [e.g., the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF)] derived from EU sources, the allocation of the spending was largely an affair of the member states.

Taken together, these national-level initiatives provided urgently needed support for both investment and consumption and represented remarkably open-ended commitments for a country normally associated with fiscal probity. At the same time, they reflected significant continuity of policy orientation, with a focus on key social and economic groups, and a more socialized conception of welfare, pre-emptively intervening to avoid social and economic damage rather than mitigating it after the fact. Though Germany's more robust network of automatic stabilizers, such as unemployment insurance, might help to explain the fact that officials favored a more targeted approach, with the general population benefitting from pre-existing, more general benefits, the reduction in generosity of such benefits with the so-called “Hartz IV” reforms in the early 2000s has constrained such support (Vail, 2010). Accordingly, the disproportionate support afforded to economically important groups during the pandemic suggests the durability of established insider-outsider cleavages that have long characterized the German export-led growth model. To the extent that such automatic stabilizers are operative, they provide support that is different in scope and scale from the robust, targeted measures that constituted the core of the German response.

Repairing damage in the United States: investing in public health and a targeted, short-term expansion of the safety net

In early 2020, Congress, in rare bipartisan fashion, responded aggressively to the pandemic, passing three distinct but related measures. The first, the “Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act,” devoted a modest $8.3 billion to support public health, dedicated funds to vaccine research, funded broad public-health initiatives on the federal, state, and local levels, and purchased personal protective equipment for medical professionals (Breuninger, 2020).

The second package, the so-called “Families First Coronavirus Response Act,” focused on the pandemic's economic effects on individuals. It devoted a total of $192 billion to paid sick and medical leave for certain categories of businesses and significant subsidies to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, colloquially known as “Food Stamps”), temporarily increased the generosity of Medicaid and Medicare (the federal health-insurance programs for the poor and elderly), and subsidized existing unemployment-insurance benefits (Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, 2020).

The third, and much more extensive measure, dubbed the “Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act” (CARES), represented the most extensive crisis-related package since the New Deal. Costing $2.2 trillion, the measure involved four distinctive areas of assistance. The first entailed an increase in the generosity of unemployment insurance, providing an additional $600 per week and extending the length of eligibility. A second measure offered one-time relief payments of up to $1,200 per adult and $500 per child. The third extended support to businesses directly affected by the collapse in demand, including $350 billion for forgivable loans to small and medium-sized enterprises and $58 billion for airlines, which had seen air traffic decline by about 60% (Slotnick, 2020). The fourth measure included funds for overwhelmed hospitals; additional funds for vaccine development, veterans' health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and money for medical equipment and community health centers. In April, Congress passed an additional program, the Paycheck Protection Program, which provided loans, forgivable under certain circumstances, to firms in exchange for their commitment to keep workers on their payroll.3 In addition, the law created a new type of unemployment assistance, as opposed to insurance, which extended eligibility to previously ineligible people, including those who had exhausted their state-level benefits, those who quit their jobs to care for ill family members, and the self-employed whose incomes were affected by the pandemic (Stone, 2020).

Following President Biden's electoral victory in November 2020, Congress adopted an $900 billion package that focused on extending existing programs to support affected households and businesses. The measure provided additional income-contingent stimulus payments of $600 per person, additional unemployment payments of $300 per week, childcare and nutrition assistance for the poorest Americans, and emergency assistance to renters. On the business side, it provided an additional $248 billion for the Paycheck Protection Program and funding for colleges and universities and the entertainment industry. It also devoted modest resources to infrastructure initiatives, including money to expand broadband internet access for families whose children were being educated at home, and $45 billion for airlines, highway repairs, and public transportation (Siegel et al., 2021).

Following two surprising Democratic victories in the Georgia Senate runoffs, which gave Democrats unified political control, Congress enacted the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan in March 2021, with no Republican support. This package was unprecedented in scope, with large extensions of previous measures as well as an array of new initiatives, including one-time, income-contingent payments of $1,400 for each adult and child and an extension of additional federal payments for unemployment insurance. Breaking with historical patterns of federal support for children, which had traditionally been provided through non-refundable tax credits, the measure introduced 6 months of direct family allowances, scaled by family income and refundable beyond a family's tax liability. This paradigm-shifting initiative, which like most of the package was fiercely opposed by Republicans, represented an unprecedented assumption of federal responsibility for supporting children.4 The package also extended $350 billion to state and local government and money for educational institutions, restaurants, early-childhood development programs, vaccine distribution, public transportation, and infrastructure, as well as more than a half billion dollars for the Federal Emergency Management Association's Emergency Food and Shelter Program. Focusing overwhelmingly on directly affected individuals and business and low-income families, the measure was much more targeted than its German counterpart and reflected a more individualistic and fragmented model of solidarity. This difference is consistent with broader policy patterns in the two countries' welfare states. Germany's neocorporatist logic and administration yield contributory policies jointly managed by workers and employers (or other relevant actors, such as doctors' associations in health insurance) across a wide range of policy areas, from unemployment insurance, to pensions, to health care. In the U.S., with the sole exceptions of Social Security and Medicare, by contrast, policies tend to focus on individual behaviors and often impose onerous work and job-search requirements for eligibility, though this varies significantly by state. Salient examples include Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and many state-administered unemployment-insurance schemes.

Empirical analysis: public opinion reactions

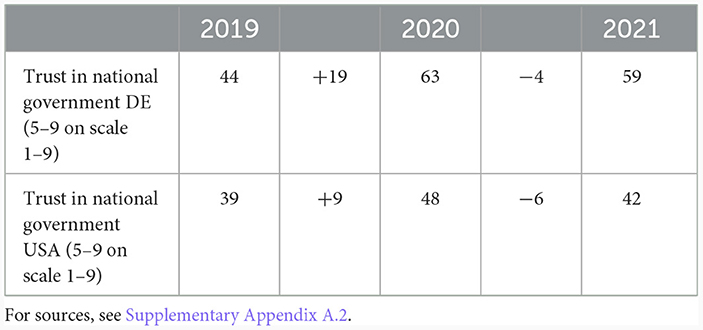

In view of these divergent policy responses, we now turn to the mechanisms, located in individuals' views and priorities, that lie behind such patterns. We start by examining potential rally-to-the-flag effects. Gallup runs a long-established global series asking for confidence in one's government (Table 2).

Both countries reveal a clear jump in aggregate confidence in government between 2019 and 2020. The German public's confidence rose by 8% points, from 57 to 65%. The American public's confidence rose by 10% points from 36 to 46%. What is more, the high levels of confidence in both countries are exceptional in the long run, dating back to 2006 in this series. The second-highest confidence level in Germany was 63% in 2015. In the U.S., only 2006 and 2009 witnessed higher levels at 56% and 50%. The change from 2020 to 2021 is downward again in both countries with 5–6 points. This is what we would expect if an emotionally driven rally to the flag effect were in place. This outcome is consistent with Proposition #2 above, relating to expectations of increased trust in government, though it also provides reason to expect distinctive patterns of support cross-nationally.

For a comparable indicator (trust in government, Table 3), we see a similar picture, a sizeable jump in trust in government by 19 points in Germany and nine points in the U.S. between 2019 and 2020, followed by a decline in 2021 that we have already seen for confidence in national government.5 This increase in political trust after the onset of the pandemic has been demonstrated for other contexts in Western Europe (Bol et al., 2021; Esaiasson et al., 2021; Oude Groeniger et al., 2021; Schraff, 2021).

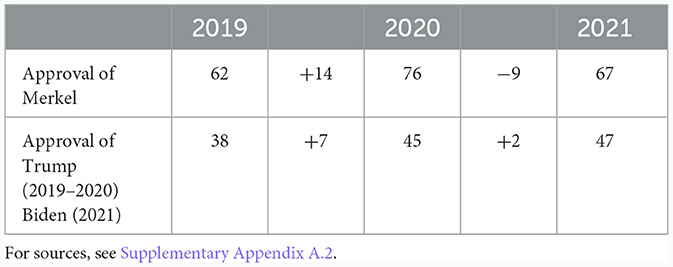

In both countries, there was an increase in approval of the leadership of the respective country (Table 4), which was much smaller in the United States (+5%) than in Germany (+14%). These trends reflected the different levels of general support or approval of national governments (higher in Germany than in the U.S.). The relative changes were upward in both countries between 2019 and 2020. After 2020, the United States experienced a change in leadership from Trump to Biden. German approval rates decreased by nine points whereas the U.S. public had a small increase in approval by two points. Despite the many institutional differences, as expected in Proposition #2, we see similar indications of deeply human, emotional reactions: human nature, and the associated need for assurance and safety, dominates over institutionally embedded learning experiences.

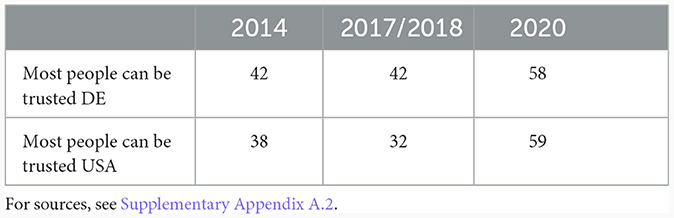

We also find some evidence of an increase in social trust (Proposition #3, Table 5). In 2020, the levels of social trust were indistinguishable in the two countries, at 58%−59%. In 2014, however, the levels were much lower, at 42 and 38%, respectively. In 2017/2018, the German estimates were unchanged, whereas in the U.S., they had declined to 32%. Thus, available evidence shows higher levels of social trust in 2020 than in earlier years, but with similar levels at the height of the crisis. This outcome supports our proposition that countries with higher degrees of social embeddedness will experience greater social trust in the presence of social and economic dislocation.

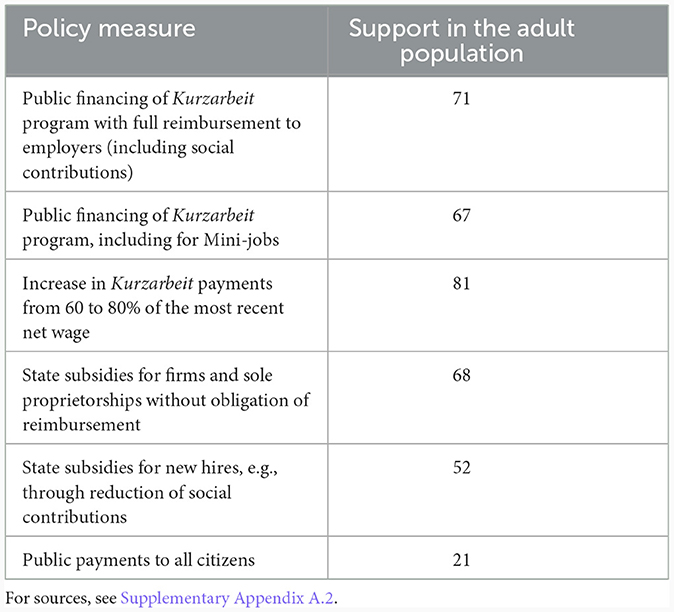

With respect to attitudes toward specific economic and social policies in Germany, there is strong evidence for support for status-maintaining policies and investments in preserving and protecting key groups in the labor market. According to our estimates from May/June 2020 in Table 6, four measures that directly protect jobs had approval rates of 50% and more. Per-head payments for the public, by contrast, were only supported by 21% of the populace.

Table 6. Policy attitudes toward anti-COVID19 economic and social policies in Germany in May/June 2020.

In another survey conducted at the same time (Politbarometer), one-off payments for families with children also found a majority of 57%. The absence of any questions about healthcare reflects the fact that the near-universal, socialized healthcare system is uncontroversial in Germany.

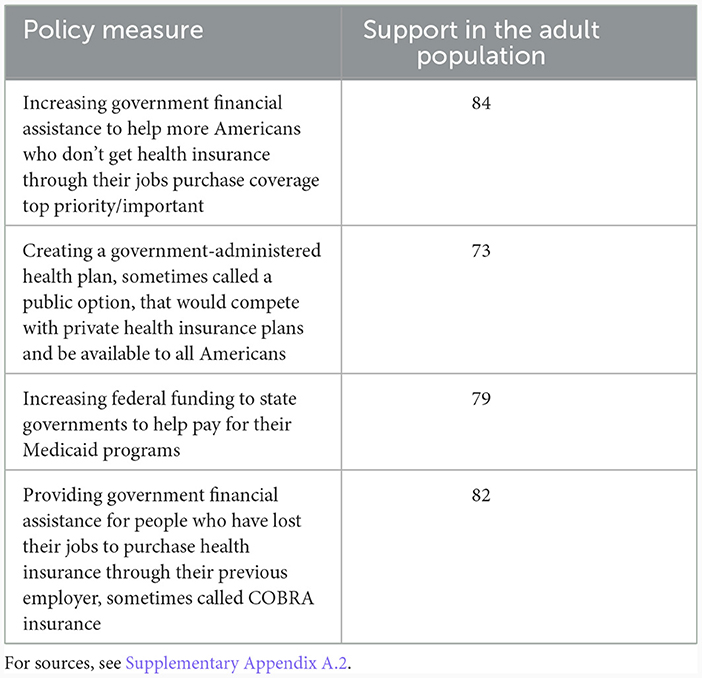

With respect to American public-opinion data regarding specific policies (Table 7), health policy was the most salient policy area before the crisis and remained so afterwards. Various surveys (Kaiser Family Foundation) reveal that this was the most important issue for the American public (as to their voting intentions): 89% in February 2020 just before the pandemic, 85% in May, 87% in September, and 91% in October 2020. In other words, the electoral salience of health policy was not really affected by the pandemic in the U.S. because it had been so salient before. It thus comes as no surprise that health-policy changes suggested to fight the pandemic found broad majorities, as well.

Finally, we consider public views on inequality. In Germany, there is evidence for increased support for a wealth tax for people with at least €500,000 in assets to combat the economic consequences of the pandemic. In May 2020, 51% supported such a measure, compared to 56% in November 2020 and 58% in February 2021 (Freiburger Politikpanel). This increase in support, however, is not mirrored in support for an increase in the solidarity contribution levied since the 1990s in order to promote socio-economic equality between East and West (a mere 17%, up from 15%). Among Americans, 67% supported a universal basic income for the course of the pandemic in July 2020 (Kaiser), but there is no evidence for robust support for sustained measures to combat inequality.

Both countries show high levels of concern about division. Though this is not the same as concern about inequality, after the COVID crisis, 67% of Germans and 89% of Americans were worried about greater division in society (More in Common Survey).

Although state-level implementational differences in public-health measures such as mask mandates varied in the United States, there is no evidence that such differences exerted any systemic effects on national-level support for public-spending initiatives designed to buffer citizens from the economic effects of the pandemic. In Germany, such regional differences were more muted, with variations stemming largely from regional and time-delimited differences in the severity of the outbreak and, to a lesser extent, ideological differences among Länder governments (Behnke and Person, 2022). In general terms, Länder governments sought to achieve consensus and to limit cross-regional variations in the implementation of federal-level mandates. We therefore conclude that both states' federal structures exerted limited and non-systemic effects upon public policy and patterns of public support.

Although some recent policy initiatives by the Biden administration might lead one to conclude that the American public has become more broadly supportive of government intervention, we believe that caution is warranted on this score. To be sure, the passage of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which embarks on a set of serious industrial-policy initiatives related mostly to combatting climate change, might lead one to conclude that support for robust government intervention had durably increased. However, given widespread public unfamiliarity with the act's provisions, broad public support for the legislation should be taken with a grain of salt. Even broad support for some of the act's main provisions, such as tax credits for investments in clean energy infrastructure, public support for the act (about 74% among likely voters at the time of its passage) (Data for Progress, 2022) must be set against Americans' historical preference for tax credits, which are easier to sell politically, than direct fiscal outlays, which they distrust.6 These factors suggest that this departure from past trends is fragile and unlikely to be reproduced across other contexts. Indeed, the recent abandonment of the refundable and more generous child tax credit, promulgated as part of post-COVID stimulus measures, would seem to justify such skepticism.

In sum, we find support for positive reactions associated with a rally-to-the-flag effect in both countries, indicated in increases in confidence and trust in government and approval of the national leaders. For prosociality, social trust shows an increase in both countries for 2020 compared to earlier years. The policy-specific reactions are surprisingly predictable given the intensity and breadth of the pandemic in its consequences. Citizens seem to remain relatively consistent in how they want governments to react. The German public seems to be supportive, as we would expect, of aggressive policies to combat inequality whereas in the U.S., we only see evidence for time-delimited measures that would last only for the duration of the crisis. In addition, post-COVID patterns of policy making in both countries, with the partial exception of the IRA in the U.S., have continued to hew to established paradigms; the German reliance on the Kurzarbeitergeld program and the American abandonment of the refundable child tax credit serve as illustrative examples. To be sure, with these surveys, we cannot be sure how citizens would have responded to other survey questions (preferably exactly the same ones in both countries). With that caveat, we argue that these outcomes are consistent with our propositions relating to both common effects across countries and cross-national variation in public support for particular sets of policy responses.

Conclusion: social embeddedness, public opinion, and public policy: the lessons of COVID-19

We have traced German and American policy responses to COVID-19 and explained them as the products of differing patterns of embeddedness and associated models of solidarity, using a systematic investigation of shifts in public opinion in the two countries, with particular emphasis upon levels of public trust in government and support for varying policy initiatives. The trauma of the pandemic led to highly emotionally charged public responses, with significant increases in public trust in and reliance upon government in both countries. This development reflects a significant rally-around-the-flag effect, a reaction that was perhaps surprising in the United States, given the deep currents of public distrust of government that have prevailed there since the 1980s.

That said, the character of shifts in public opinion differed markedly in the two countries. In the United States, where economic relationships are much more disembedded and the moral economy more fragmented and individualistic, the public disproportionately supported individualized benefits and assistance to individuals and firms directly affected by the pandemic. In Germany, by contrast, where economic and labor-markets are more deeply embedded and where workers and employers have traditionally shared a common, if sometimes contested, sense of public purpose, surveys reflected support for investments in existing collectivized labor-market institutions, rather than merely to repair economic damage after the fact. These distinctive arrangements and patterns of social embeddedness, we argue, help to explain the fact that the measures supported by German citizens tended to be more solidaristic and institutionalized, with the Kurzarbeitergeld and state support for new hires serving as a key example. If the American response reflected a logic of post-hoc, palliative care, then, its German counterpart reflected one of preventative medicine combined with systemic investment in established social and economic relationships.

Although the full scale of the effects of the pandemic will take several years to reveal themselves, our research suggests several important implications relating to the effects of cataclysmic shocks, such as pandemics, natural disasters, and wars. First, despite widely varying baseline levels of support for government cross-nationally, such events tend to bolster public support for the collective responses that only states can provide. Second, the kinds of policy interventions supported by citizens may well parallel, and perhaps even reinforce, pre-existing levels of social embeddedness in the economy, with patterns of group-based solidarities acting as both outgrowths and reinforcements of existing institutions and established political and social practices. In this context, distinctive national moral economies and social and economic institutions are tightly linked, with exogenous shocks revealing underlying shared moral and conceptual frameworks that are not reducible to simple institutional dynamics, but rather reflect deeply embedded understandings of the imperatives of remedying structural inequalities and differential access to economic resources. These findings are consistent with those presented in other recent work, including (Béland et al., 2021).7

Finally, in a more speculative vein, we suggest that the ways in which such underlying normative structures mediate between catastrophes and both public attitudes and social and economic arrangements may take years to unfold, much as the Black Death in the 14th century began to erode feudalism in ways that were far from obvious at the time. Such long-term consequences could also be highly regionalized and pan out differently across large polities, especially when they are federal states. In future research, we hope to exploit the increasing availability of longitudinal public-opinion data related to COVID-19 to arrive at more systematic conclusions about the relationship between catastrophes and public attitudes, in an era in which such catastrophes—ranging from pandemics to natural disasters whose severity and frequency are increasing in the wake of human-engendered climate change—are becoming both more common and more severe.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The libraries of Tulane University, Wake Forest University, and the University of Duisburg Essen provided research support, and the latter generously funded the access to the Roper Archive and Gallup Analytics. AG would like to thank the European Research Council for funding this paper including publication costs through the Consolidator Grant project POLITSOLID “Political Solidarities” (# 864818) accessible at https://bit.ly/politsolid.

Acknowledgments

All authors would like to thank Manuel Diaz Garcia and Josra Riecke for research assistance. Further data were gathered from the GESIS (2018) Archive.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2024.1273824/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^As a result, we are constrained by the timing of polling efforts and their relationship to government actions, such as executive orders introducing physical distancing measures.

2. ^Public opinion data bear out this contention. In a recent Pew survey, fewer than four in ten Americans surveyed believed that addressing inequality should be a top priority of government, In contrast, in an OECD poll, more than half of Germans surveyed strongly believed that inequality was too great, well above the OECD average and in increasing shares over time since 2017. See Mitchell (2020) and OECD (2021).

3. ^The contrast between the targeted, time-delimited nature of this program and its reliance on loans, and the much more generous and open-ended Kurzarbeitergeld program in Germany is typical.

4. ^The recent excision of this measure from the Inflation Reduction Act, passed in August 2022, shows how precarious this shift was.

5. ^Another indicator by Gallup World Poll reveals a similar picture with 53% of Germany in 2018 and 82% in 2020 trusting their national government some or a lot, compared to 47% and 52% in the USA.

6. ^It is worth noting that the act also contained a widely popular provision enabling Medicare to negotiate drug prices with pharmaceutical companies, which no doubt bolstered support for the law overall.

7. ^This article cited is one contribution to a 2021 special issue of Social Policy and Administration, several of the articles of which deal with cross-national and cross-regional variation in policy responses to COVID-19.

References

Alter, J. (2021). Opinion | Can biden be our F.D.R.? The New York Times, sec. Opinion. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/12/opinion/biden-fdr-new-deal.html (accessed April 12, 2021).

Baker, W. D., and Oneal, J. R. (2001). Patriotism or opinion leadership?: the nature and origins of the “Rally ‘Round the Flag”' effect. J. Conflict Resol. 45, 661–687. doi: 10.1177/0022002701045005006

Bauer, M., Blattman, C., Chytilová, J., Henrich, J., Miguel, E., Mitts, T., et al. (2016). Can war foster cooperation? J. Econ. Perspect. 30, 249–274. doi: 10.1257/jep.30.3.249

Baum, M. A. (2002). The constituent foundations of the rally-round-the-flag phenomenon. Int. Stud. Q. 46, 263–298. doi: 10.1111/1468-2478.00232

Behnke, N., and Person, C. (2022). Föderalismus in der krise – restriktivität und variation der infektionsschutzverordnungen der länder. Dms –Mod. Staat – Z. Public Policy Recht Manag. 15, 9–10. doi: 10.3224/dms.v15i1.03

Béland, D., Cantillon, B., Hick, R., and Moreira, A. (2021). Social policy in the face of a global pandemic: policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis. Soc. Policy Adm. 55, 249–260. doi: 10.1111/spol.12718

Bénabou, R., and Tirole, J. (2006). Belief in a just world and redistributive politics. Q. J. Econ. 121, 699–746. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2006.121.2.699

Bol, D., Giani, M., Blais, A., and Loewen, P. J. (2021). The effect of COVID-19 lockdowns on political support: some good news for democracy? Eur. J. Polit. Res. 60, 497–505. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12401

Bowles, S. (2008). Being human: conflict: altruism's midwife. Nature 456, 326–327. doi: 10.1038/456326a

Breuninger, K. (2020). Senate passes $8.3 billion emergency coronavirus package, sending bill to trump's desk. CNBC. Available online at: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/05/senate-passes-8point3-billion-coronavirus-bill-sending-it-to-trumps-desk.html (accessed March 5, 2020).

Bruegel. (2020). The Fiscal Response to the Economic Fallout from the Coronavirus | Bruegel.Available online at: https://www.bruegel.org/publications/datasets/covid-national-dataset/ (accessed August 23, 2021).

Bundesfinanzministerium (2021a). Emerging from the crisis with full strength - Federal Ministry of Finance - Issues. Bundesministerium Der Finanzen. Available online at: https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/EN/Standardartikel/Topics/Public-Finances/Articles/2020-06-04-fiscal-package.html (accessed April 1, 2021).

Bundesfinanzministerium (2021b). Combating the coronavirus: Germany adopts the largest assistance package in its history - Federal Ministry of Finance - Issues. Bundesministerium Der Finanzen. Available online at: https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/EN/Standardartikel/Topics/Priority-Issues/Corona/2020-03-25-combating-the-corona-virus.html (accessed April 1, 2021).

Carter, Z. D. (2021). Opinion | The coronavirus killed the gospel of small government. The New York Times, sec. Opinion. Available online at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/11/opinion/coronavirus-economy-government.html (accessed March 11, 2021).

Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (2020). Families first coronavirus response act will cost $192 billion. Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Available online at: https://www.crfb.org/blogs/families-first-coronavirus-response-act-will-cost-192-billion (accessed April 6, 2020).

Data for Progress (2022). Voters Support the Inflation Reduction Act. Data For Progress. https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/2022/8/3/voters-support-the-inflation-reduction-act (accessed August 3, 2022).

Esaiasson, P., Sohlberg, J., Ghersetti, M., and Johansson, B. (2021). How the coronavirus crisis affects citizen trust in institutions and in unknown others: evidence from ‘the swedish experiment.' Eur. J. Polit. Res. 60, 748–760. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12419

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

GESIS (2018). GESIS Panel - Standard Edition. ZA5665 Data file Version 31.0.0. Cologne: GESIS Data Archive.

Goerres, A., and Walter, S. (2016). The political consequences of national crisis management: micro-level evidence from German voters during the 2008/09 Global Economic Crisis. German Polit. 25, 131–153. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2015.1134495

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 91, 481–510. doi: 10.1086/228311

Groeling, T., and Baum, M. A. (2008). Crossing the water's edge: elite rhetoric, media coverage, and the rally-round-the-flag phenomenon. J. Polit. 70, 1065–1085. doi: 10.1017/S0022381608081061

Hall, P. A., and Soskice, D. (2001). Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/0199247757.001.0001

Herd, P., and Moynihan, D. P. (2018). Administrative Burden: Policymaking by Other Means. New York, NY: Russell Sage. doi: 10.7758/9781610448789

Koos, S., and Sachweh, P. (2019). The moral economies of market societies: popular attitudes towards market competition, redistribution and reciprocity in comparative perspective. Socio-Econ. Rev. 17, 793–821. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwx045

Lambert, A. J., Schott, J. P., and Scherer, L. (2011). Threat, politics, and attitudes: toward a greater understanding of rally-'round-the-flag effects. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 20, 343–348. doi: 10.1177/0963721411422060

Matthews, D. (2021). How the U.S. won the economic recovery. Vox. Available online at: https://www.vox.com/22348364/united-states-stimulus-covid-coronavirus (accessed April 30, 2021).

McCollum, B. (2020). H.R.266 - 116th congress (2019-2020): paycheck protection program and health care enhancement act. Webpage. 2019/2020. Available online at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/266 (accessed April 24, 2020).

Menand, L. (2021). The making of the new left. The New Yorker. Available online at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/03/22/the-making-of-the-new-left (accessed March 22, 2021).

Mitchell, T. (2020). Most americans say there is too much economic inequality in the u.s., but fewer than half call it a top priority. Pew Research Center's Social and Demographic Trends Project (blog). Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/01/09/most-americans-say-there-is-too-much-economic-inequality-in-the-u-s-but-fewer-than-half-call-it-a-top-priority/ (accessed January 9, 2020).

Mizrahi, S., Cohen, N., and Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2020). Government's social responsibility, citizen satisfaction and trust. Policy Polit. 48, 443–460. doi: 10.1332/030557320X15837138439319

Obinger, H., and Petersen, K. (2017). Mass warfare and the welfare state – causal mechanisms and effects. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 47, 203–227. doi: 10.1017/S0007123415000162

OECD (2021). Does Inequality Matter?: How People Perceive Economic Disparities and Social Mobility. Paris: OECD. doi: 10.1787/3023ed40-en

Oude Groeniger, J., Noordzij, K., van der Waal, J., and de Koster, W. (2021). Dutch COVID-19 lockdown measures increased trust in government and trust in science: a difference-in-differences analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 275:113819. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113819

Pierce, J. J. (2021). Emotions and the policy process: enthusiasm, anger and fear. Policy Polit. 49, 595–614. doi: 10.1332/030557321X16304447582668

Polanyi, K. (1957). “The economy as instituted process,” in Trade and Markets in the Early Empires: Economies in History and Theory, eds K. Polanyi, C. M. Arensberg, and H. M. Pearson (Glencoe, IL: The Free Press).

Polanyi, K. (2001). The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origns of Our Time. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Sachweh, P., and Olafsdottir, S. (2012). The welfare state and equality? Stratification realities and aspirations in three welfare regimes. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 28, 149–168. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcq055

Schraff, D. (2021). Political trust during the Covid-19 pandemic: rally around the flag or lockdown effects?. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 60, 10071017. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12425

Siegel, R., Stein, J., and DeBonis, M. (2021). Here's What's in the $900 Billion Stimulus Package. Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/12/20/stimulus-package-details/ (accessed March 8, 2022).

Slotnick, D. (2020). Coronavirus demolished air travel around the globe. These 14 charts show how empty the skies are right now. Business Insider. Available online at: https://www.businessinsider.com/air-traffic-during-coronavirus-pandemic-changes-effects-around-the-world-2020-4 (accessed April 22, 2020).

Stone, C. (2020). CARES Act Measures Strengthening Unemployment Insurance Should Continue While Need Remains | Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Available online at: https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/cares-act-measures-strengthening-unemployment-insurance-should-continue (accessed June 9, 2020).

Thompson, E. P. (1971). The moral economy of the english crowd in the eighteenth century. Past Present 50, 76–136. doi: 10.1093/past/50.1.76

Titmuss, R. M. (2019). Essays on “The Welfare State”. Bristol: Policy Press. doi: 10.1332/policypress/9781447349518.001.0001

Vail, M. I. (2010). Recasting Welfare Capitalism: Economic Adjustment in Contemporary France and Germany. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Keywords: solidarity, COVID-19, political trust, inequality, labor markets, fiscal policy, Germany, United States

Citation: Goerres A and Vail MI (2024) How national models of solidarity shaped public support for policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis in 2020–2021. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1273824. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1273824

Received: 07 August 2023; Accepted: 12 January 2024;

Published: 06 February 2024.

Edited by:

Francis Boateng, University of Mississippi, United StatesReviewed by:

Jeffrey Anderson, Georgetown University, United StatesRobert Cox, University of South Carolina, United States

Sarah Wiliarty, Wesleyan University, United States

Copyright © 2024 Goerres and Vail. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Achim Goerres, QWNoaW0uR29lcnJlc0B1bmktZHVlLmRl

Achim Goerres

Achim Goerres Mark I. Vail

Mark I. Vail