94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 25 January 2024

Sec. Peace and Democracy

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1267022

This article is part of the Research TopicPolitics, Nationalism and Identity: A World in Flux?View all 4 articles

Scotland is an interesting case study when it comes to politics, nationalism and identity. The separatist movement led by the Scottish National Party (SNP) raises a wide range of questions with regard to Scottish and British politics as well as people's sense of belonging. Given that young people are the generation most likely to witness a hypothetical second independence referendum in the future, this paper focuses on them. It examines the young members of the SNP. It explores the interconnection between Scottish politics and young SNP members' nationalism as well as their understanding of Scottishness. With the analysis of empirical research conducted from 2018 to 2020, it suggests that the Young Scots for Independence (YSI) and SNP Students' nationalism should be regarded as socio-nationalism. This paper defines it as the promotion of societal values and a certain perception of society combined with the promotion and defense of a nation. Interviews and questionnaires reveal that these young people define Scotland as socially just, equal and open. Overall, their definition of Scottishness is similar. In that sense, this paper argues that their political ideology and their sense of belonging are interrelated. This is highlighted by the fact that Scottish independence is, among other factors, the most significant reason why young people choose to become SNP members. It also highlights a relationship between their sense of Scottishness and their wish for Scotland to become independent. Therefore, this paper argues that young people's membership of the SNP and national identity are interrelated.

The issue of independence makes the relationship between politics, nationalism and identity much studied in Scotland. Most scholars agree on the civic aspect of Scottish nationalism.1 Sociologist McCrone (1998, 2001), McCrone and Bechhofer (2015) insists that Scottish identity is related to the notions of place and territory. Also, he argues that contemporary Scottishness builds on center-left politics. In that sense, Scottish nationalism is viewed as civic, not ethnic nor cultural. Taking inspiration from Nairn (1977), McCrone considers Scottish nationalism as “neo-nationalism” in that sense. It is a modernist2 view of Scottish nationalism. Murray Stewart Leith and Daniel P.J. Soule define that approach as follows: “the Scottish modernist interpretation put forward is one of Scottishness as a territorial, civic-based form of identity, whereby an individual resident in Scotland can claim to be Scottish” (Leith and Soule, 2012, p. 4).

The nationalism of the Scottish National Party, the main pro-independence party in Scotland, is widely regarded as civic too.3 Both the leaders and members of the SNP consider themselves a civic nationalist party. This was particularly illustrated by the 2014 independence referendum. During the campaign, the argument of national identity was not used by the SNP. Some leaders like former First Minster Nicola Sturgeon even declared that Scottish identity was not a reason why they wanted Scotland to become independent. In 2012, Sturgeon said:

“For my part, and I believe for my generation, I have never doubted that Scotland is a nation. (…) But for me the fact of nationhood or Scottish identity is not the motive force for independence. Nor do I believe that independence, however desirable, is essential for the preservation of our distinctive Scottish identity. (…) My conviction that Scotland should be independent stems from the principles, not of identity or nationality, but of democracy and social justice” (Sturgeon, 2012).

For Leith, this is explained by the fact that the Scottish nation and Scottish identity are not questioned (Leith, 2010, p. 299). Hence the idea that the SNP do not need to highlight and defend them in their campaign for independence.

Inclusiveness is another element accounting for the civic feature of SNP nationalism. The party praises cultural diversity and highlights the economic benefits of immigration for Scotland. In 2016, Nicola Sturgeon insisted that immigration “made Scotland stronger” (Irish Independent., 2016) and at the SNP conference in Aberdeen in June 2018, she said: “The ‘we' is everyone who chooses to live here” (Sturgeon, 2018). Hence, again, the civic dimension of SNP nationalism.

It is regarded as civic also amongst scholars. Tellingly, for Nathalie Duclos, “[a]n analysis of SNP literature reveals that the party appeals to all of the civic components of national identity, but not ethnicity, and rarely to culture” (Duclos, 2016, p. 102). This echoes Hamilton, who argues for “the Scottish National Party's lack of ethnic character” (Hamilton, 1999). Instead of focusing on ethnocultural elements, SNP nationalism focuses on socio-economic elements, namely on a social-democratic independent Scotland compared to a right-wing, Conservative, United-Kingdom. In a study of party manifestos from 1970 to 2010, Leith has examined the discourse of the SNP about national identity (Leith, 2008; Leith and Soule, 2012). He shows that before the 1980s, their discourse was rather anti-British and anti-English. But, since that decade, their campaign for Scottish independence has built on socio-economic elements exclusively. Hence, again, the idea that SNP nationalism is—at least today—civic. Edwige Camp-Pietrain specifies that SNP claims are based mainly on socio-economic elements thanks to the example of the 2014 referendum campaign:

“The SNP had a discourse centered on economic and social themes, and on ‘people living in Scotland,' refraining from using the term ‘Scottish.' The challenge for the nationalists was to avoid any shift toward ethnic lines, their leaders being careful to describe themselves as Scottish and British. They wanted to demonstrate that it was necessary to achieve independence not to defend a people, but to promote distinct ‘values,' in particular social democracy” (Camp-Pietrain, 2014, p. 69).4

When it comes to “values,” the relationship between national identity and values is worth examining, particularly in the Scottish context.

Interestingly, Duclos (2016, p. 99) says that Scottish identity has been politicized. For her, this process of politicization of Scottishness happened in the 1970s first, when the SNP gained power in the political arena both in Scotland and the UK, and then during the Thatcher era. She specifies that “Scottish identity was politicized in those years because being Scottish was redefined as being anti-Conservative and pro-Welfare State.” In that sense, being Scottish would mean being against the British Conservative government's policies and in favor of social-democratic and progressive measures. Ailsa Henderson and Nicola McEwen highlight that politicization of Scottish identity too. Besides, they insist that Scottishness is based on values (Henderson, 1999; Henderson and McEwen, 2005). They argue that shared values contribute to a national sense of belonging, thus challenging Norman (1995, p. 147)'s theory that “It is not typically common values that lead to a common identity, but vice versa.” Henderson and McEwen nonetheless specify that values do not create a national identity. Rather, it is an aspect of it and it reinforces it. The two scholars also challenge Kymlicka (1995, 1996)'s idea that values like egalitarianism, social justice and fairness—the core values of Scottish identity from the perspective of civic SNP nationalism—are too universal to be attributed to a single national identity.

To summarize, in the literature, most scholars agree that Scottish nationalism is civic and that Scottish identity is devoid of cultural and ethnic traits in the SNP's campaign for independence. Instead, Scottishness is a political object used to oppose a social-democratic, progressive and egalitarian Scotland to a Conservative rest of the United Kingdom—not to say England. Hence the thin line between national identity, political ideology and governmental policies here. This relation is further examined thanks to the study of young SNP members—in both the youth and student wings of the party—that was carried out between 2018 and 2020. Given that the 2014 independence referendum mobilized young people5 and given that they are the generation most likely to witness a hypothetical second independence referendum in the future, I decided to focus on the young members of the SNP. A recent research paper reinforces the idea that it is worth examining young Scottish people's views when it comes to independence. By analyzing Scottish Social Attitudes Surveys by ScotCen from 1999 onwards about people aged 18 and over (except in 2016: 16 and over), Lindsay Paterson highlights an “association of independence with youth” (Paterson, 2023). She relevantly shows that:

“In twelve opinion polls conducted between early April and early July 2023—after Humza Yousaf had become the new leader of the SNP (and First Minister)—the average support [for independence] among people born 1959–68 was 40 per cent, and for those born 1979–88 was 57 per cent. The same gradient continued for people who had been too young to vote in the 2014 referendum (for which the voting age was 16): among people born 1999–2007, the percentage support was 66 per cent.”

This cohort effect regarding support for independence was also highlighted by the referendum results: scholars working on the Scottish Referendum Study found out that the age group that voted most for independence in 2014 was the 25–29 group, while the people aged 70 and over were the group that voted most against it (BBC., 2015). Thanks to her exploration of Scottish Social Attitudes Surveys, Paterson argues for a relationship between a liberal political ideology, education, youth and support for independence. For example, she notes that in 2016, there was a “liberal and left leadership of the independence movement among people who are well-educated and have a Scottish identity. Because the graduates were disproportionately younger, with 40 per cent having been born since the mid-1960s, that leadership also tended to be young.” Interestingly, she even suggests that with young people, Scottish independence could become a reality in the future. She bases her arguments on cohort replacement:

“If independence support is two-thirds of the younger group and only one-third of the older (as the recent polls suggest), that would add perhaps 20,000 independence supporters every year, though this would be less in practice, because turnout tends to be lower in younger groups. So, the annual rise of independence support owing to cohort replacement is probably at most 0.4 per cent of the total electorate. The resulting change in overall support is thus slow and is swamped by the usual random variation in opinion polls. But, if it continues, it would eventually not be negligible.”

In other words, for Paterson, the youngest generations in Scotland are key generations when it comes to the holding of a second referendum and, potentially, Scottish independence from the United Kingdom. Hence the need to examine young SNP members' views, especially as they are pro-independence. The study carried out from 2018 to 2020 is introduced below.

In order to analyze the relationship between young SNP members, their national identity and their political involvement, both qualitative and quantitative methods were used: interviews and an online survey. A total of 25 young members of the party were interviewed. The interviews last between 45 min and an hour and a half. They were semi-guided interviews, which enabled young party members to talk about their views of national identity expansively. For Fox and Miller-Idriss, semi-guided interviews give “opportunities for exploring ordinary people's discursive representations of nationhood in terms chosen by the interviewee—not the interviewer” (Fox and Miller-Idriss, 2008, p. 555). The interviews were conducted from 2018 to 2020 in Aberdeen, Glasgow, Edinburgh and via phone and video calls. Most of them were carried out during SNP annual conferences. The members of the Young Scots for Independence (YSI) and SNP Students interviewed were between 18 and 32 years old. To add to the analysis of the interviews, a quantitative survey was conducted in 2020. An online questionnaire was sent to the young members of the SNP via emails and social media. 38 people responded to it. They were aged between 18 and 29. It should be noted that very few young people are really active in the party.6 Consequently, the number of people interviewed and surveyed is not high. This was frustrating. I would have liked to get at least 100 responses to the online questionnaire so as to draw more significant conclusions. But it appears that the number of respondents corresponds to the number of young people actively involved in the party. To a certain extent, the results are nonetheless significant because they concern the most active members of the youth and student wings of the party, not the “free riders” (Olson, 1965).

Qualitative and quantitative methods were complementary. The online questionnaire allowed to draw conclusions based on figures, namely on scientific data, while interviews allowed for an in-depth exploration of young SNP members' conceptions of national identity. National sense of belonging is, indeed, hard to quantify—except maybe with the Moreno scale (Moreno, 2006).7 Fox and Miller-Idriss relevantly sum all this up:

“Surveys are effective instruments for gaining a general overview of the national sensibilities of relatively large segments of the population. Surveys are less suited, however, for capturing variation in the nuance and texture of everyday nationhood. For this, more qualitative modes of investigation are helpful, such as interviewing and focus groups” (Fox and Miller-Idriss, 2008, p. 555).

Anonymity was part of the methodology chosen. I thought it was fundamental to preserve these young people's privacy and I wanted to see whether there was a gap between SNP's official discourse on Scotland and Scottishness and their young members' personal thoughts. To be more specific, given that they knew the interviews and the questionnaire were anonymous, they probably felt freer to say what they really thought about Scotland and their identity.

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Verbal informed consent for participation in the study and for audio recording was obtained from the interviewees. Written informed consent was not required for participation in the online survey in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. All participants declared that they were at least 18 years of age.

So as to understand how young SNP members view their national identity and see whether they joined the pro-independence party for identity reasons, during interviews they were asked the following questions: How would you define Scottishness, Scottish identity? What are the characteristics of Scottish society? Is Scottishness a reason why you engaged in politics? In the online survey, the questions that were asked were as follows: What does symbolize Scotland? What are the characteristics that represent Scotland best?

Before studying young SNP members' definition of their national identity, it should be noted that a majority declared they felt Scottish only, not British. The Moreno scale (Moreno, 2006) was quite useful to measure the degree of importance of Scottishness compared to Britishness amongst the YSI and SNP Students. I was able to see that most of the young SNP members feel exclusively Scottish: this was the case of 88 per cent of the interviewees and 90 per cent of the respondents (Breniaux, 2021b, p. 330). It might be said that the fact that they do not feel British is congruent with their wish for Scotland to be independent from the United Kingdom. Their sense of nationhood seems to be related to their political involvement. Yet, Mitchell, Bennie and Johns' study about SNP members suggests that people do not join the party for identity reasons. Let us see whether this is confirmed by the analysis of young SNP members' views of Scottish identity and its place in their campaign for independence.

The civic aspect of SNP nationalism is highlighted by the study I conducted from 2018 to 2020 in the youth and student wings of the party. Their understanding of Scottish identity should be regarded as socio-political, not cultural nor ethnic. In total 56 per cent of the definitions of Scottish identity by the interviewees built on socio-political criteria (Breniaux, 2021b, p. 359). Among them, egalitarianism, social justice and fairness were the most mentioned. Those societal values confirm the link between national identity and values in Scotland in the academic literature (Henderson and McEwen, 2005; Camp-Pietrain, 2014). It also rejects Norman's theory that national identity leads to shared values (Norman, 1995) given that in the case of young SNP members, societal values like social justice and equality contribute to the definition of Scottish identity.

Some of the young interviewees talked about culture but it was not the majority of them. More particularly, some insisted that it is social-democracy and progress which symbolize Scotland,8 as well as living in Scotland, not stereotypes or clichés about Scotland. Liam said: “Scottishness is not really bagpipes, haggis. It's more personal. When you come to Scotland, you're Scottish.” Here, the civic characteristic of Scottish identity is clear.

The fact that the majority of the young SNP members studied think of their national identity from a socio-political—not cultural nor ethnic—perspective is confirmed by the online survey results: 66 per cent of the respondents based their definition of Scottish identity on socio-political criteria (Breniaux, 2021b, p. 362). Scottish culture accounted for 13 per cent of the definitions given by the survey respondents. Both culture and socio-political criteria represented 21 per cent of the responses.9 For instance, a respondent argued: “Scotland is traditionally symbolized by kilts, shortbread and whisky. Whereas modern Scotland can be symbolized by so much more. I think the people who live in Scotland are the greatest representation of us as a nation.” (Breniaux, 2021b, p. 362). Another respondent highlighted the civic features of SNP nationalism, saying that Scotland may be defined as “a place that welcomes everyone” (Breniaux, 2021b, p. 362). This civic and socio-politically oriented version of Scottishness is in line with the literature on SNP's discourse about national identity (Henderson, 1999; Henderson and McEwen, 2005; Leith, 2008; Leith and Soule, 2012; Duclos, 2014, 2016, 2020).

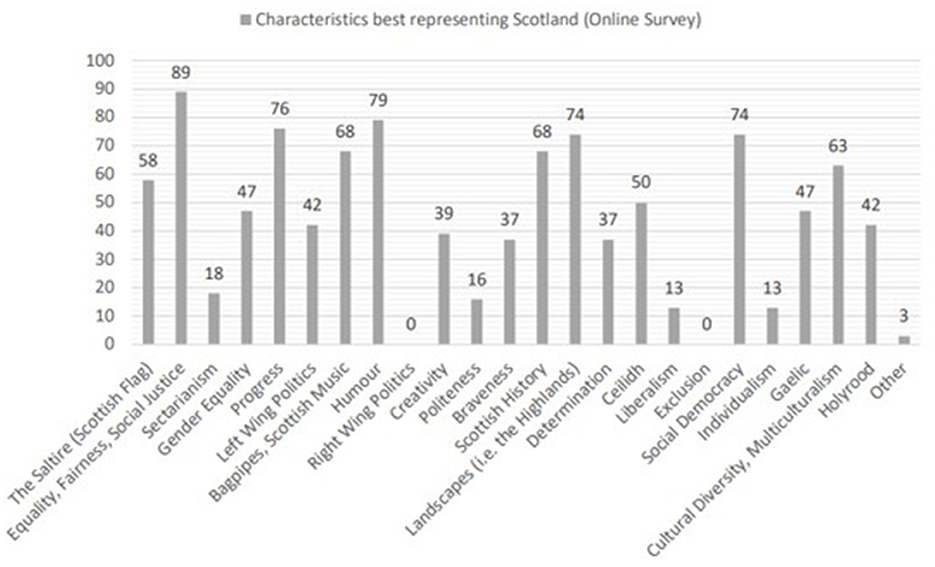

When it comes to their visions of Scotland, it appears that they consider it a social-democratic, inclusive and progressive nation. Scottish culture is not a dominant feature in their definitions.10 Therefore, it may be said that their understanding of Scottish society is socio-political rather than cultural. It aligns with their views of Scottish identity presented earlier. Their overall socio-political version of Scotland is highlighted by Figure 1.

Figure 1. Characteristics best representing Scotland according to young SNP respondents (percentages1) as shown in Breniaux (2021b, p. 346).

Interestingly, those findings suggest a correlation between young SNP members' views of their national identity and their political ideology. First, as they campaign for a social-democratic independent Scottish nation compared to a Conservative UK (especially England), it may be argued that their socio-political definition of Scotland and Scottishness goes hand in hand with Scottish independence, namely their political goal. Second, there are clear similarities between their socio-political understanding of Scottish identity and social democracy, namely their political ideology and party family.11 In that sense, here political ideology and sense of belonging are related. Let us now see what such a link involves.

In their study published in 2012, Mitchell et al. (2012) argue that national identity may be regarded as a motivation for Scottish people to join the SNP, but they note that it is not a major reason. They even say that “[v]ery few of the responses contained specific reference to the importance of Scottish national identity” (Mitchell et al., 2012, p. 74). Few of the young SNP members I interviewed or who responded to the online questionnaire referred to Scottish national identity when they talked about the reasons why they joined the party. Harry12 told me “I'm for independence because I feel Scottish.” As he joined the SNP and given that the main goal of the party is independence, it may be argued that he joined the party for national identity reasons. It should be noted that very few of the young people studied declared explicitly that they were SNP members because of their sense of Scottishness. In that sense, the results of my study align with those of Mitchell, Bennie and Johns. Yet, despite that they did not mention national identity explicitly, it seems that it may be considered a significant reason why young people become SNP members though.

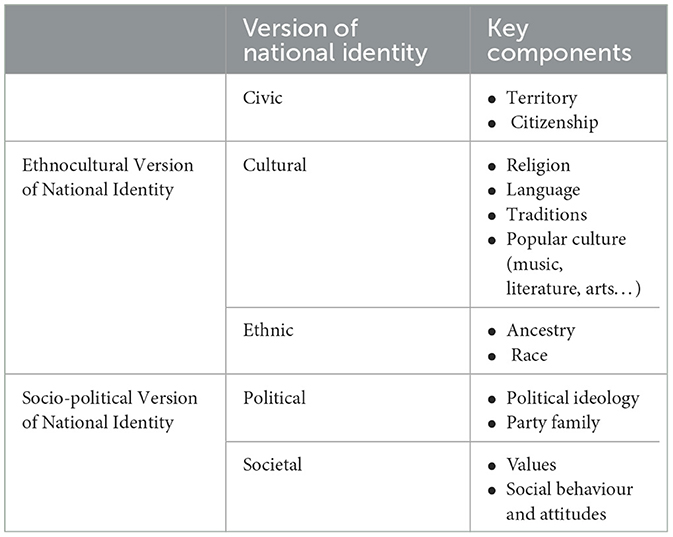

The interviews and the questionnaire responses highlight a relationship between young SNP members' views of Scotland and Scottish identity and their wish for Scotland to become an independent nation-state. As shown before, most of the young SNP members studied defined Scottishness from a socio-political perspective. In the same way, they described Scotland as a socially just, equal, fair and inclusive nation. Interestingly, when I asked them why they fought for Scottish independence, they answered with the same socio-political arguments.13 Therefore, their definitions of Scottish identity and society, and their claims for independence align. Thus, it seems that national identity does play a part in their political involvement. The fact that their motivations for campaigning for Scottish independence are congruent with the way they define Scottish identity means that their SNP party membership and their national identity are interrelated. Contrary to Mitchell, Bennie and Johns, this study concludes that Scottishness plays a significant part in SNP youth party membership.14 Also, it suggests that the notion of national identity should be re-defined. The present study shows that it should not be seen as either civic or ethnic/ethnocultural only. It may also be regarded as societal, political, or both, namely as a socio-political identity. In this regard, it adds to Stephen Shulman's “Alternative Contents of National Identity” (Shulman, 2002, p. 559), a three-dimensional typology of national identity—civic,15 cultural and ethnic: see Table 1.

Table 1. Versions of national identity (as inspired by Shulman's “Alternative contents of national identity” theory), as shown in Breniaux (2021b, p. 405).

The socio-political understanding of national identity and the fact that the young SNP members studied referred to societal values when defining Scotland and Scottishness suggest that rather than considering YSI and SNP Students' ideology and activism as nationalism, it should be considered as socio-nationalism.16 It should be regarded as close to civic nationalism in the sense that it is mainly based on the belief in and the defense of civic values. However, I posit that it slightly differs from civic nationalism in the sense that it builds explicitly on societal values and a vision of society while this is less clear in civic nationalism. Thus, socio-nationalism may be defined as the promotion of a nation with arguments based on societal values. Socio-nationalists may be regarded as people who fight for the recognition of their nation at the same time as fighting for the kind of society they want to live in. In the case of young SNP members, they campaign for Scotland to become an independent nation—in other words, a nation-state—based on the social-democratic and progressive values that they believe in: social justice, equality, inclusiveness.

This paper has shown that the way young members of the Scottish National Party see Scottish society and their national identity, and their political participation are interrelated. In that sense, it has argued that their nationalism should be regarded as socio-nationalism. It builds on the defense of societal values. Through socio-nationalism, young SNP members claim for Scottish independence by highlighting that an independent Scotland would be able to promote the societal values they believe in, compared to the rest of the UK, more especially England.

The political dimension of their nationalism should not be forgotten. It builds on societal values but also on the wish to put an end to what they consider a democratic deficit from which Scotland suffers by staying in the UK.

Thus, their political participation combines their campaign for a social-democratic Scotland, a nationalism based on the promotion of societal values and a social-democratic vision of society, and their socio-political views of Scottish identity, all revolving around the central goal of independence. Hence the idea that the line between nationalism, identity and politics is very thin. This is the case at least in Scotland, amongst the young members of the SNP. It would be instructive to see whether it is the case in other countries, other political parties and amongst older parts of the population too. It would allow to either confirm the relation between nationalism, identity and politics or suggest that Scotland is a particular case. Also, it would be helpful to test the concept of socio-nationalism in other countries so as to see whether it is specific to Scotland.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Verbal informed consent for participation in the study and for audio recording was obtained from the interviewees. Written informed consent was not required for participation in the online survey in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. All participants declared that they were at least 18 years of age.

CB: Writing—original draft.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^Civic nationalism is characterised by territorial claims to achieve sovereignty as a nation-state, without being based on ethnic arguments.

2. ^Modernism or constructivism (Anderson, 1983; Gellner, 1983; Hobsbawm and Ranger, 1983) considers national identity is flexible and may evolve depending on time and place. It is opposed to essentialism or primordialism (Geertz, 1973; Connor, 1994), which argues that national identity is natural, innate and fixed.

3. ^Mycock (2012) nonetheless questions the wholly civic nature of SNP nationalism in his paper on “SNP, identity and citizenship.” In the same way, without necessarily focusing on Scotland, Xenos (1996) and Yack (1996) question the notion of civic nationalism. While Xenos suggests that it is an “oxymoron” and insists on the blurred lines between civic and ethnic nationalism, Yack argues that civic nationalism is a “myth.”

4. ^Original text in French: “Le SNP tenait un discours centré sur des thèmes économiques et sociaux, et sur les ‘personnes vivant en Ecosse', se gardant d'employer le terme ‘Ecossais'. L'enjeu, pour les nationalistes, était d'éviter tout basculement vers des critères ethniques, leurs dirigeants prenant soin de se décrire comme écossais et britanniques. Ils souhaitaient démontrer qu'il fallait accéder à l'indépendance non pas pour défendre un peuple, mais pour promouvoir des ‘valeurs' distinctes, en particulier la social-démocratie.”

5. ^In total of 75 per cent of the people of 16 and 17 years of age went to vote in the referendum in 2014 (The Electoral Commission., 2014).

6. ^I witnessed that on the internet and during SNP conferences: the (few) young people who were much active and involved in the campaign for independence and in the life of the party, either on social media or when they attended the party's conferences, were always the same. Each time, they were a maximum of 30 or 40 people.

7. ^In the 1980s, thanks to his research, Luis Moreno argued that in Scotland, people feel: only Scottish, not British; more Scottish than British; equally Scottish as British; more British than Scottish; or only British, not Scottish. Thanks to the Moreno Question.

8. ^It echoes David McCrone's argument that contemporary Scottishness builds on centre-left politics. See the introduction of this paper.

9. ^Altogether, those 34 per cent—both the young people defining Scottishness with cultural criteria and those doing so with cultural and socio-political criteria—show that some young SNP members' nationalism is perhaps not wholly civic, thus echoing Mycock (2012)'s paper as well as Xenos (1996) and Yack's (1996) views on civic nationalism (see the introduction of the present paper).

10. ^For examples, see Breniaux (2021b).

11. ^Thus confirming Henderson and McEwen's conclusions (Henderson, 1999; Henderson and McEwen, 2005). See the introduction of the present paper.

12. ^Names were changed for anonymity reasons.

13. ^For examples, see Breniaux (2021a,b).

14. ^See Breniaux (2021b, p. 397).

15. ^This type of national identity includes “political ideology” for Shulman. With the present study, I preferred to put it in the political content of national identity that I identified.

16. ^See Dingley (2008)'s analysis of the relationship between nation and society as well as between social theory and nationalism.

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined Communities. Reflection on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

BBC. (2015). Study examines referendum demographics. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-34283948 (accessed November 10, 2023).

Breniaux, C. (2021a). Young Scottish National Party Members” Perceptions of Scotland and the United Kingdom. Observ. Soc. Britann. 26, 127–148. doi: 10.4000/osb.5090

Breniaux, C. (2021b). Young Scottish National Party (SNP) Members' National Identity and Party Membership. Doctor of Philosophy, University of Bourgogne Franche-Comté.

Connor, W. (1994). Ethnonationalism: The Quest for Understanding. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780691186962

Dingley, J. (2008). Nationalism, Social Theory and Durkheim. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9780230593107

Duclos, N. (2014). L'Ecosse en quête d'indépendance ? Le référendum de 2014. Paris: Presses de l'Université Paris-Sorbonne.

Duclos, N. (2016). “The idiosyncrasies of scottish national identity,” in National Identity. Theory and Research, eds. A. Milne, and R. R. Verdugo (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 83–112.

Duclos, N. (2020). “Le nationalisme écossais et l'identité politique du Scottish National Party,” in Processus de transformation et consolidation identitaires dans les sociétés européennes et américaines aux XXe-XXIe siècles, eds A. Palau and M. Smith (Louvain-La-Neuve: Academia - L'Harmattan).

Fox, J. E., and Miller-Idriss, C. (2008). Everyday nationhood. Ethnicities 8, 536–563. doi: 10.1177/1468796808088925

Hamilton, P. (1999). The Scottish national paradox: the scottish national party's lack of ethnic character. Canad. Rev. Stud. National. 26, 17–36.

Henderson, A. (1999). Political constructions of national identity in Scotland and Quebec. Scottish Affairs 29, 121–138. doi: 10.3366/scot.1999.0056

Henderson, A., and McEwen, N. (2005). Do shared values underpin national identity? Examining the role of values in national identity in Canada and the United Kingdom. Natl. Ident. 7, 173–191. doi: 10.1080/14608940500144286

Hobsbawm, E., and Ranger, T. (1983). The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Irish Independent. (2016). Nicola Sturgeon: Immigration has made Scotland stronger. Available online at: https://www.independent.ie/videos/video-nicola-sturgeon-immigration-has-made-scotland-stronger-34851731.html (accessed April 24, 2020).

Kymlicka, W. (1995). Multicultural Citizenship: A Liberal Theory of Minority Rights. Oxford: Clarendon Press. doi: 10.1093/0198290918.001.0001

Kymlicka, W. (1996). Social unity in a liberal state. Soc. Philos. Policy 13, 105–136. doi: 10.1017/S0265052500001540

Leith, M. S. (2008). Scottish national party representations of scottishness and Scotland. Politics 28, 83–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9256.2008.00315.x

Leith, M. S. (2010). Governance and identity in a devolved Scotland. Parliam. Affairs 63, 286–301. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsp032

Leith, M. S., and Soule, D. P. J. (2012). Political Discourse and National Identity in Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780748647118

McCrone, D. (1998). The Sociology of Nationalism: Tomorrow's Ancestors. London, New York: Routledge.

McCrone, D. (2001). Neo-nationalism in stateless nations. Scott. Affairs 37, 3–13. doi: 10.3366/scot.2001.0062

McCrone, D., and Bechhofer, F. (2015). Understanding National Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316178928

Mitchell, J., Bennie, L., and Johns, R. (2012). The Scottish National Party: Transition to Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199580002.001.0001

Moreno, L. (2006). Scotland, catalonia, europeanization and the “Moreno Question.” Scottish Affairs 54, 1–21. doi: 10.3366/scot.2006.0002

Mycock, A. (2012). SNP, identity and citizenship: re-imagining state and nation. Natl. Ident. 14, 53–69. doi: 10.1080/14608944.2012.657078

Norman, W. (1995). “The ideology of shared values: a myopic vision of unity in the multination state,” in Is Quebec Nationalism Just? Perspectives from Anglophone Canada, ed. J. H. Carens (Montreal and Kingstone, London, Buffalo: McGill-Queen's University Press). doi: 10.1515/9780773565609-007

Olson, M. (1965). The Logic of Collective Action. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Paterson, L. (2023). Independence is not going away: the importance of education and birth cohorts. Polit. Quart. 94, 526–534. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.13306

Shulman, S. (2002). Challenging the civic/ethnic and west/east dichotomies in the study of nationalism. Compar. Polit. Stud. 35, 554–585. doi: 10.1177/0010414002035005003

Sturgeon, N. (2012). Bringing the powers home to build a better nation, Speech at Strathclyde University. Available online at: http://www.gov.scot/News/Speeches/better-nation-031212 (accessed July 12, 2023).

Sturgeon, N. (2018). Speech to Scottish National Party conference, Aberdeen, June 9th, 2018. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HpwriZ3kRlg (accessed July 20, 2023).

The Electoral Commission. (2014). Scottish Independence Referendum Report on the referendum held on 18th September 2014. Available online at: https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf_file/Scottish-independence-referendum-report.pdf (accessed November 10, 2023).

Xenos, N. (1996). Civic nationalism: oxymoron? Crit. Rev. 10, 213–231. doi: 10.1080/08913819608443418

Keywords: young people, socio-nationalism, national identity, political participation, Scotland

Citation: Breniaux C (2024) Young SNP members: socio-nationalism, identity and politics. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1267022. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1267022

Received: 25 July 2023; Accepted: 11 January 2024;

Published: 25 January 2024.

Edited by:

Murray Stewart Leith, University of the West of Scotland, United KingdomReviewed by:

Andrew Mycock, University of Leeds, United KingdomCopyright © 2024 Breniaux. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Claire Breniaux, Y2xhaXJlLmJyZW5pYXV4QHVuaXYtZmNvbXRlLmZy

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.