- 1Department of Sociology, Jagannath University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 2School of Sociology, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China

This paper examines why and how Myanmar makes Rohingyas a stateless community in Southeast Asia, known as one of the most vulnerable human groups in the contemporary world. Based on the secondary evidence, the paper argues that Rohingyas are stateless because they are the victim of four discourses: former Bangladeshi people who illegally entered Myanmar; collaborators to British armies while Myanmar was fighting for its independence from British rule; attachment to Islamic terrorism; and foreign interests in the Rakhine state. The paper draws on a wide range of local and global literature to support its arguments. The paper uses extant sociological approaches to understand why a minority community becomes stateless and experiences genocide in their own country. The researcher developed an analytical framework to answer the research questions. This analytical framework draws on existing literature, recent strategies, theoretical understandings, contemporary data, and government responses to understand the process of Rohingya statelessness. This paper finds that Myanmar not only expelled Rohingyas from their homeland by imposing the blame on them but is also unwilling to return over a million Rohingyas from Bangladesh—a host country for them. The paper also finds that the international community is least concerned about the genocide and expulsion of the Rohingyas because of Myanmar’s communal agenda and foreign countries’ economic interests in the Rakhine state. The paper offers some recommendations to address this unique inhuman condition in its concluding part.

Introduction

Myanmar is a neighboring country of Bangladesh which was previously recognized as Burma. This historically significant state is situated in Southeast Asia and surrounded by Laos, Bangladesh, China, and Thailand. In 1948 Myanmar received freedom from the United Kingdom. It is a Buddhist country formally, but it has around 135 familiar ethnic minorities that reflect an enormous religious variety. Rohingya is a Muslim minority community of Myanmar living in the Rakhine state (western Myanmar) (please see Figure 1) and is also known as Muslim Arakanese. The term “Rohingya” derives from the word “Rohang” and reflects the Rakhine state’s ancient name (Ullah, 2016). An additional expression of this state was “Arakan,” a free empire earlier than the British colonization of Myanmar. Approximately two million Rohingyas reside in Myanmar, and 800,000 of them live in the state of Rakhine (Farzana, 2017: 2). This Muslim minority group claims themselves as the residents of Myanmar, but the authority of Myanmar does not accept it. Rather the authority of Myanmar claimed them as illegal settlers (Albert and Maizland, 2020; Ullah and Chattoraj, 2023).

Figure 1. Geographical map of the Rakhine State. © Myanmar Information Management Unit 2017. https://reliefweb.int/map/myanmar/myanmar-district-map-rakhine-state-23-oct-2017-enmy.

The distinctiveness of the Rohingya community has been governmentally, politically, and administratively infested by offering two solid unions in Myanmar, namely the Pro-Rohingya and the Anti-Rohingya. Historical analysis of the Rohingya community is similarly disputed, and the people who are affirmative towards this community declare that during the 9th century, Rohingya settlement was done in Myanmar by mixing with Bengalis, Turks, Moghuls, and Persians (Ullah, 2016). This argument focuses on the traditionally diverse demography of Rakhine (Albert and Maizland, 2020). In contrast, the Anti-Rohingya bloc declares that Rohingya is an up-to-date, self-produced individuality created by illegal Chittagongnian Bengali immigrants entering Myanmar due to the rule of the British colony. The Government of Myanmar (GOM) applies the word “Bengali” that recommends status as migrants for labeling Rohingya. Moreover, the Rohingya community is not accepted as inhabitants of Myanmar; rather, people of this Muslim minority group are termed as “resident foreigners” (Ullah, 2016). Accordingly, Rohingyas are deprived of a state-individuality or identity and residency and are effectually stateless (Farzana, 2017: 2).

The Government of Myanmar has been oppressing Rohingyas for hundreds of years. Due to the intentions of the Myanmar authorities, people of the Rohingya community have been excluded from the national identity of Myanmar (Ullah and Chattoraj, 2018). Bangladesh similarly ignores the people of this community, and the Government of Bangladesh (GOB) claimed that the Rohingya issue is Myanmar’s own problem.

This paper aims to explore why Rohingyas are stateless or excluded systematically from some significant human, social and political rights and confront interference even in their personal life decisions, for example, marriage and having children, and the processes used by Myanmar military-dominated government in doing so. The central research question of this paper is why and how the Rohingyas are stateless. Therefore, this paper investigates the nature, extent, and incidence of exclusion among the Rohingya community through secondary data analyses and explains how multidimensional exclusion makes them stateless and pushes them into vulnerable conditions. The researcher developed an analytical framework to answer the research questions. Finally, in this paper, the researcher attempt to explain the processes of statelessness by using a pragmatic theoretical framework to interpret these dynamics and processes.

This article is divided into eight sections. The first section deals with the study objective and research question. The second section discusses the historical background of the Rohingya statelessness. The third section contextualizes statelessness from relevant theoretical perspectives. The fourth section clarifies the research methodology. The fifth section develops an analytical framework. The sixth section details the findings. The seventh section consists of a discussion, and the final section draws conclusions.

Rohingya statelessness: historical background

There is a lot of academic research regarding the crisis of the Rohingya community. The researcher initially reviewed significant literature about Rohingya and their statelessness for writing this paper (Ullah, 2016; Amnesty International, 2017; Beyrer and Kamarulzaman, 2017; Milton et al., 2017; Lewis, 2019; Albert and Maizland, 2020; Hossain et al., 2022). Many scholars mentioned ethnicity and identity crisis as the prime causes of the exclusion and vulnerability of the Rohingya community (Ullah, 2016; Cheesman, 2017; Farzana, 2017: 21). Moreover, several former pieces of research established the situation of Rohingyas as a humanitarian crisis (Ullah, 2011; Kingston, 2015; Kaveri, 2017). Categorizing by the administration, the population of Myanmar consists of 135 different ethnic groups. Rohingya is one of the marginal groups that are not accepted as an ethnic group in Myanmar. They mainly live in Arakan or Rakhine state, situated on the western side of the nation. The usage of the term “Rohingya” was opposed by the Myanmar government, besides the dominant ethnic Buddhist group in the Rakhine state, as it was familiarized as a way of personal identification by the people of the Rohingya community (Albert and Maizland, 2020). Ahsan Ullah argues “that Rohingyas in Myanmar have been intentionally excluded by its government.” He basically concentrated on the role of politicized ethnicity. In his writing, he also focused on the importance of politicized ethnicity for creating national unity. Furthermore, in Myanmar, Political Buddhism, which is the combination of Buddhist religious faith and nationalism, is used to oppress the Rohingya Muslim minority people (Ullah, 2016).

Farzana explores the underlying causes of the displacement of the Rohingya community of Myanmar in her book Memories of Burmese Rohingya Refugees. She marks the processes by which Rohingya identity has been politicized, and subsequently, it has brought the consequences that affected the Rohingya community. She claims that minority clusters replace with “identity-less parasites” by state policies, but the victimized minority can preserve their identity through memories and culture. The Rohingya community is an example of this identity-less parasite. Furthermore, she argues that “more attention to the social and political processes of forced migration and identity politics that generate protracted displacement” is needed for studying the Rohingya crisis (Farzana, 2017: 3).

The first displacement of Rohingya refugees started in 1978, and 200,000 escaped to Bangladesh. Subsequently, improved identity policies from the Myanmar government, the situation of forced migration happened and targeted those persons who were previously refugees. Myanmar’s government denied their participation in the 1978 displacements, and the authority claimed that they were not accountable for people who crossed the boundary to Bangladesh (Farzana, 2017: 50). Boycotting the goods and trades of Rohingyas is an additional vital phenomenon. “Several campaigns continue to call for a boycott of Muslim businesses, including the foreign telecom giant Ooredoo; In any public lecture events, disrupt Muslim or Muslim-sympathetic speakers; threaten boycott against the 2014 census” (Zin, 2015). Moreover, the Myanmar government is considering the Rohingyas as an extreme economic load for the country due to their competition for the limited existing business, jobs, and opportunities (Wolf, 2015).

The constitution of Myanmar safeguards the rights and independence of all Burmese citizens, but Rohingyas are excluded from these constitutional rights since they are not Burmese citizens. Hence, Rohingyas achieved a small number of political and civil rights, and they were permitted to vote in the 1990 election (Farzana, 2017: 52–53). Rohingyas were given white cards (provisional identity cards), which permitted them to vote in the general election of 2008 (Albert and Maizland, 2020). The constitution of Myanmar stated that the Union (i.e., Myanmar) “shall guarantee any person to enjoy equal rights before the law and shall equally provide legal protection” (Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar 2008, September 2008: Paragraph 347). Consequently, Rohingyas failed to enjoy equal rights before the law like the Burmese citizens, and the provisional identity cards were automatically canceled in 2015 by rejecting their right to vote. The Myanmar government ignored the Rohingya community’s civil rights in other situations. Rakhine state is one of the poorest states in Myanmar, where 78 percent of the inhabitants are living beneath poverty brink. The massive mistrust between the Muslim Rohingya and Buddhists in the Rakhine region was generated due to the mixture of poverty, deficiency of proper infrastructure, limited work opportunities, etc. (Albert and Maizland, 2020). Though the entire state suffers from the cited hindrances, the stigmatized Rohingyas are leading the most vulnerable lives. The reports of the Human Rights Watch show that from 25th August 2017, ferocity, rape, and violence have been used against the Rohingya men, women, and children within the Rakhine state by the military-dominated Myanmar government (Human Rights Watch, 2017).

Since the outburst of violence in 2012, the oppression of the Rohingyas by local and national governments has forcefully exiled thousands of Rohingya people. Strains touched a dangerous level in 2012 after ages of discrimination. Hundreds of Rohingya expired, and a large number of people became homeless due to violent conflicts. Several Rohingyas were imprisoned in inner displacement camps. The violent conflicts between Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingyas displaced nearly 10,000 Rohingya people in June 2012 (BBC News, 2012). During the time of violence, the United Nations guessed that approximately 100,000 Rohingyas escaped from Myanmar via sea route with life threats. Thus, the ignored and tortured Rohingya people left Myanmar only for securing their life. Aljazeera reported that around 110,000 Rohingya people left Myanmar through fragile boats to neighboring states like Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand in 2012. The report of CNN revealed that Thai police found hundreds of Rohingya males, females, and offspring in a trafficking camp in January 2014 (Hutcherson and Olarn, 2015).

According to Human Rights Watch Report, in the Sadao district of Songkhla region near the Thai-Malaysian boundary, a united army-police team found about 30 bodies in an uninhibited human trafficking camp on 1st May, 2015. A lot of them were buried in narrow graves, whereas other bodies were covered with mantles and clothes. These dead bodies were identified as ethnic Rohingyas by the police report (Human Rights Watch, 2015). The ASEAN parliaments for Human Rights report shows that approximately 100,000 Rohingya refugees now exist in Malaysia, and numerous are living in Bangladesh, Thailand, and other ASEAN (The Association of Southeast Asian Nations) countries jointly [APHR (ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights), 2015]. According to UNHCR, Rohingyas are treated as one of the world’s biggest defenseless refugee bunches (Albert and Maizland, 2020). In 2017 when the ARSA (Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army) militia attacked the police stations in the Rakhine region, the security forces of Myanmar retaliated, and consequently, the chaos started. Thousands of people became shelterless and displaced from their settlements due to the burning of the Rohingya villages by the security forces of Myanmar (Amnesty International, 2017). As a consequence of these violent terrorist attacks by the Myanmar army in August 2017 (Human Rights Watch, 2017), a huge number of Rohingya refugees started to cross the border. Approximately 650,000 Rohingyas escaped from Myanmar and surpassed the boundary to Bangladesh in order to take shelter as refugees in the Cox’s Bazar area of eastern Bangladesh (Milton et al., 2017; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2017; Choudury and Fazlulkader, 2019; Lewis, 2019). The majority of Rohingyas currently reside in Cox’s Bazar’s Ukhiya and Teknaf Upazilas near the Naf River, which serves as a porous border between Bangladesh and Myanmar (Khuda, 2020).

Based on the perspectives of the human rights scholars writings address the multidimensional aspects of Rohingya refugees living in South Asian (India and Bangladesh), and Southeast Asian countries (Faisal, 2020; Sabbir et al., 2022; Uddin, 2022; Zaman, 2022). The transforming public discourse regarding the Rohingya community and the blame-game of environmental costs of Rohingya presence in neighboring countries is declining the relationship between the host countries and the Rohingya refugees (Chemali et al., 2017; Chaudhury and Samaddar, 2018; Uddin, 2020; Shohel, 2023). Recent studies on this issue examine and analyze the reasons for increasing intra-group conflicts, declining international concerns, the failure of repatriation, diplomatic roles of the global community, voice of the universal civil society and diaspora engagement (Storai, 2018; Hossain and Hosain, 2019; Ali, 2022; Sabbir et al., 2022). The host countries including Bangladesh is considering Rohingya refugees as an additional burden on their land, social structure, job opportunities, social security, tourism industry, and economy (Dey, 2018; Bhattacharjee and Hoque, 2019). Under the criterion of sharing global justice the host countries are waiting for a stable solution and are concerned about the future direction of the Rohingya crisis.

Contextualizing statelessness from theoretical viewpoints

This study used three relevant theories of social exclusion and downgrading offered by Silver (1994), Pierre Clavel (1998), and Levitas (2005) to identify and explain the reasons for statelessness and leading dynamics of social exclusion among the Rohingya Muslim minority community of Myanmar.

Hillary Silver, a noticeable French academic, offered three central paradigms about social exclusion, formed on the considerations of the underprivileged and deprived individuals in French culture and society. Hilary displayed several meanings of exclusion and marginalization through the threefold typology of exclusion, explicitly solidarity paradigm, specialization paradigm, and monopoly paradigm. Silver varied these three paradigms from political ideologies and state dissertations. Thus, she concentrated her ideas on distinct understandings of social integration and political philosophies for explaining exclusion (Rawal, 2008).

Silver suggested that the solidarity paradigm compacts with the view that segregation and exclusion are a principal agency to collapse the societal connection between individuals and society. This social tie is not financially manufactured; rather, it is generated in cultural and ethical terms, forming a hectic condition in society that impends community order and eventually creates marginalization and social exclusion. Similarly, from this study, it can be shown that the Government of Myanmar (GOM), political leaders, and other ethnic groups did not recognize the Rohingya Muslim minority community as citizens of the country. The reason is Rohingyas were treated like residents of other countries. Besides, this model contains diverse agreement, consistency, and solidarity notions. Hilary argued whereas solidarity decays, exclusion arises (Mathieson et al., 2008: 17).

The specialization paradigm is the subsequent model of Hilary Silver. This model represents that exclusion is a product of the market fiasco or monetary discernment (Silver, 1994: 543). The monopoly paradigm is the third and concluding model of Silver. Centered on Weber and Marx, this model designates that exclusion begins when a segment of the residents is purposefully forced out from the ingress or entry to typical or shared belongings. Furthermore, this model claims that hierarchical or classified power interactions are vital for social banishment and exclusion. “Exclusion arises from the interplay of class, status, and political power and serves the political interests of the included…exclusion is combated through citizenship, and the extension of equal membership and full participation in the community to outsiders” (Silver, 1994: 543). In the case of the Rohingya Muslim minority people, political leaders of Myanmar thought of them (Rohingya) as a risk to their interests. Thus, the government of Myanmar excluded Rohingyas through various tactics to secure the interests of political leaders.

A different theoretical perspective about social exclusion came from the intellectual writings of Pierre Clavel. For simplifying social exclusion, (Clavel, 1998:184-186; DIMÉ, Mamadou dit ndongo, 2005) applied four approaches. The leading one is identified as the population groups approach, where persons of society are separated into paramount social classes considering the definite quantity of individuals as beneficiaries and other individuals as underprivileged. The subsequent one is recognized as the economic approach. This approach describes social exclusion in terms of some signs, i.e., revenue, social disparity, financial disproportion, and poverty levels. Consistently, the population of Myanmar and political leaders boycotted Rohingyas from businesses and also boycotted their goods. The denial of rights approach is the next approach that denotes the refusal of or scarcity of entrance to resources, belongings, or investments. The concluding approach is the extreme situations approach, and it represents the situation where persons are considered outsiders, unwelcomed, and aliens (Mathieson et al., 2008:18). Rohingyas are socially excluded from the mainstream community of Myanmar. This study discovers that this Muslim minority community people have been experiencing discernment through the generations. They are excluded from the conventional society, fundamental rights, labor market, social practices, and other cultural festivals and occasions. People of this community are facing an identity crisis problem. They are discriminated against more in terms of work, medical facilities, shopping, education, social security, and other purposes. Furthermore, intergenerational poverty situations, lack of wealth, limited opportunities, and powerlessness are the indicators of social exclusion in this community. These social exclusion indicators are responsible for the statelessness of the Rohingya community.

Ruth Levitas is an eminent intellectual who deliberately studied social exclusion and isolation. Levitas proposed that three discourses are responsible for relegation and social exclusion. The chief one is recognized as redistributionist discourse, which maintains that the public’s inadequacy of entire freedoms to citizenship declines their well-being circumstances that create paucity, exclusion, isolation, discernment, poverty, and relegation. Rohingyas are not considered citizens of Myanmar. The government did not categorize the Rohingyas according to the different categories of citizenship because Rohingyas are thought to be outsiders. Thus, they are deprived of various amenities. The following discourse is identified as the moral underclass discourse, which represents that the mislaid and excluded persons are accountable for their personal fate. It focuses attention on the dependent actions of the underprivileged and destitute individuals who are eliminating their expertise and capability to welfare dependence (Levitas, 2005: 21).

The concluding discourse is the social integrationist discourse. This discourse explains exclusion through the employment market. There has no opportunity to have a job and business sector for Rohingyas as they are a Muslim minority community. Similarly, this discourse gives importance to discernments among paid laborers, chiefly wage discrimination in gender frameworks (Levitas, 2005: 26; Mathieson et al., 2008:18). Furthermore, Amartya Sen described why social exclusion is inevitable in society. According to him, exclusion occurs due to the incapability of entering into the amenities which are accessible in the political, societal, and financial arenas (Sen, 2000: 4).

Rohingya statelessness in Myanmar began when this community was de facto excluded from Burmese citizenship through the “Citizenship Law of 1982”.Though the Law of Burmese citizenship did not reject the citizenship of Rohingyas, the national race was the central inducement for Burmese citizenship that is highlighted by this law and clearly presented that Kachin, Karenni, Karen, Chin, Burman, Mon, Arakanese, and Shan, who have existed in Myanmar before 1823, will get citizenship (Cheesman, 2017). This law formed three kinds of “citizens” within Myanmar: citizens, associate citizens, and naturalized citizens. Since among the 135 national races Myanmar government did not consider Rohingya, the implications of this law excluded this community from Burmese citizenship by making them stateless. That means it is impossible for a Rohingya child to obtain citizenship in Myanmar because their parents are not enlisted among these three types of citizens (Farzana, 2017: 51).

Furthermore, people of this community cannot move freely throughout the country and abroad, which is a sign of political exclusion. This political instability increases the terrorist activities within the Rakhine state. The ARSA (Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army) is a terrorist organization that operates terrorist activities within the state and has launched several attacks on the Myanmar Security Forces (MSF) in the past few years. Consequently, the Myanmar army started operations within the Rohingya villages, making the Rohingyas shelter less and stateless.

Methodological background

The central research question in this paper examines why and how Rohingyas are stateless. The methodology of this study involves secondary data analysis. For this reason, this paper is principally based on secondary sources of data. The researcher gathered information from secondary sources to conduct this study, including previously published and unpublished research works, relevant books, journal articles, internet documents, newspaper and magazine reports, e-books, and other archival documents. The researcher used a wide range of electronic databases, especially Scopus, Google Scholar, Google, Pub Med Central, Pro Quest, Web of Science, and PsycINFO, to find relevant articles and literature for this study. Research articles and significant literature on the Rohingya community published between 1957 and 2023 were considered for this study. Besides, in this study, the researcher adhered to the article’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. That means, to conduct this study, the researcher only accepted those research materials that focused on the plight of the Rohingya people in Myanmar, who are stateless, marginalized, and socially excluded. To specify the exclusion criteria, the researcher excluded the other pieces of literature and findings for not fulfilling the research question and objectives of the study. Analyzing secondary data sources, the study identifies several structural factors contributing to the statelessness of the Rohingya minority in Myanmar, which points to the analysis of this research paper.

Analytical framework

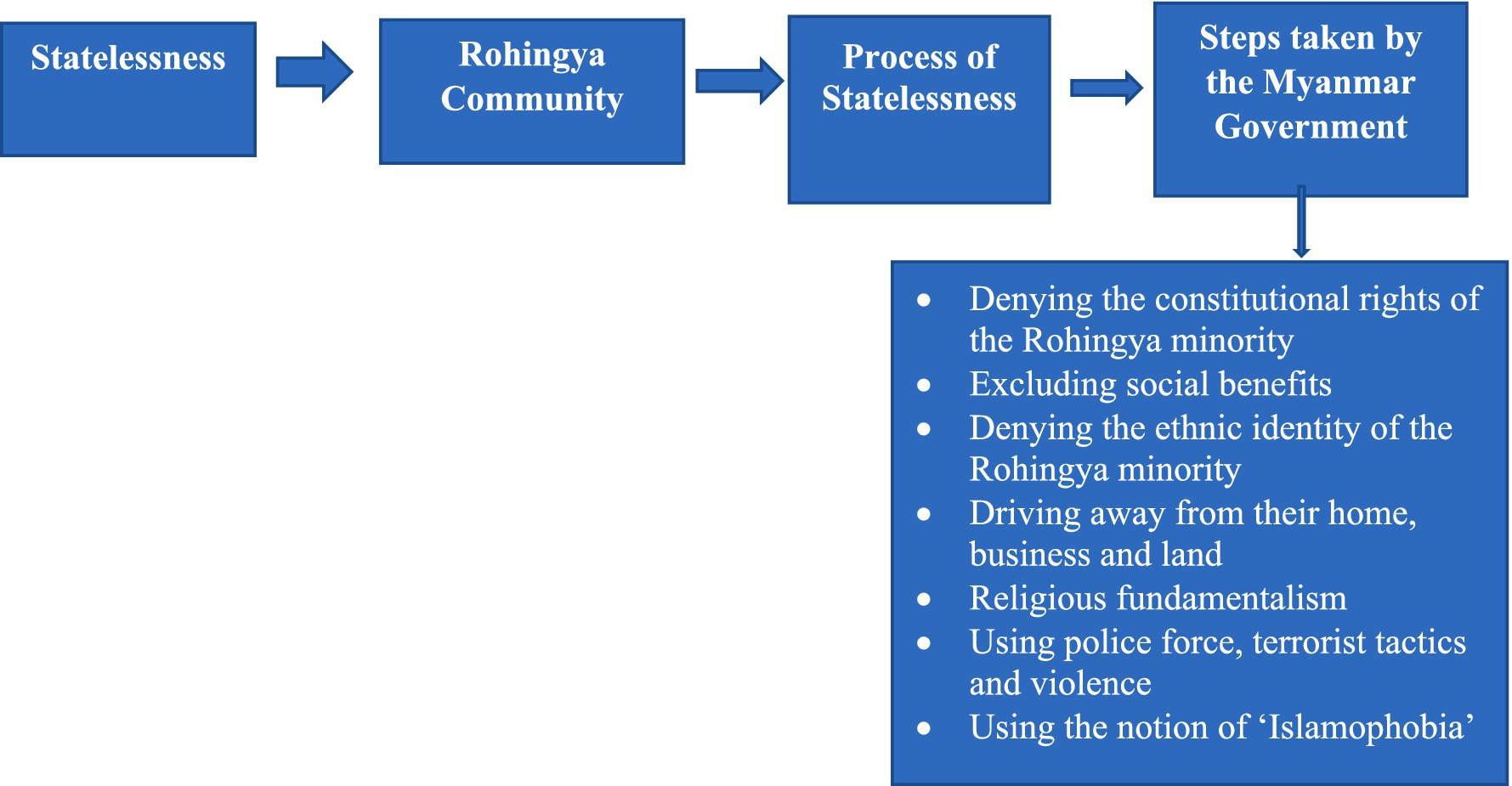

This study developed an analytical framework in order to understand the process of statelessness of the Rohingya community. Based on the research question, literatures and theoretical understandings on the Rohingya crisis this study identified that the Myanmar government applied several process to make the Rohingyas stateless. The following figure (please see Figure 2) shows the analytical framework. The findings of the present study is consistent with this analytical framework.

Findings: why and how are Rohingyas stateless?

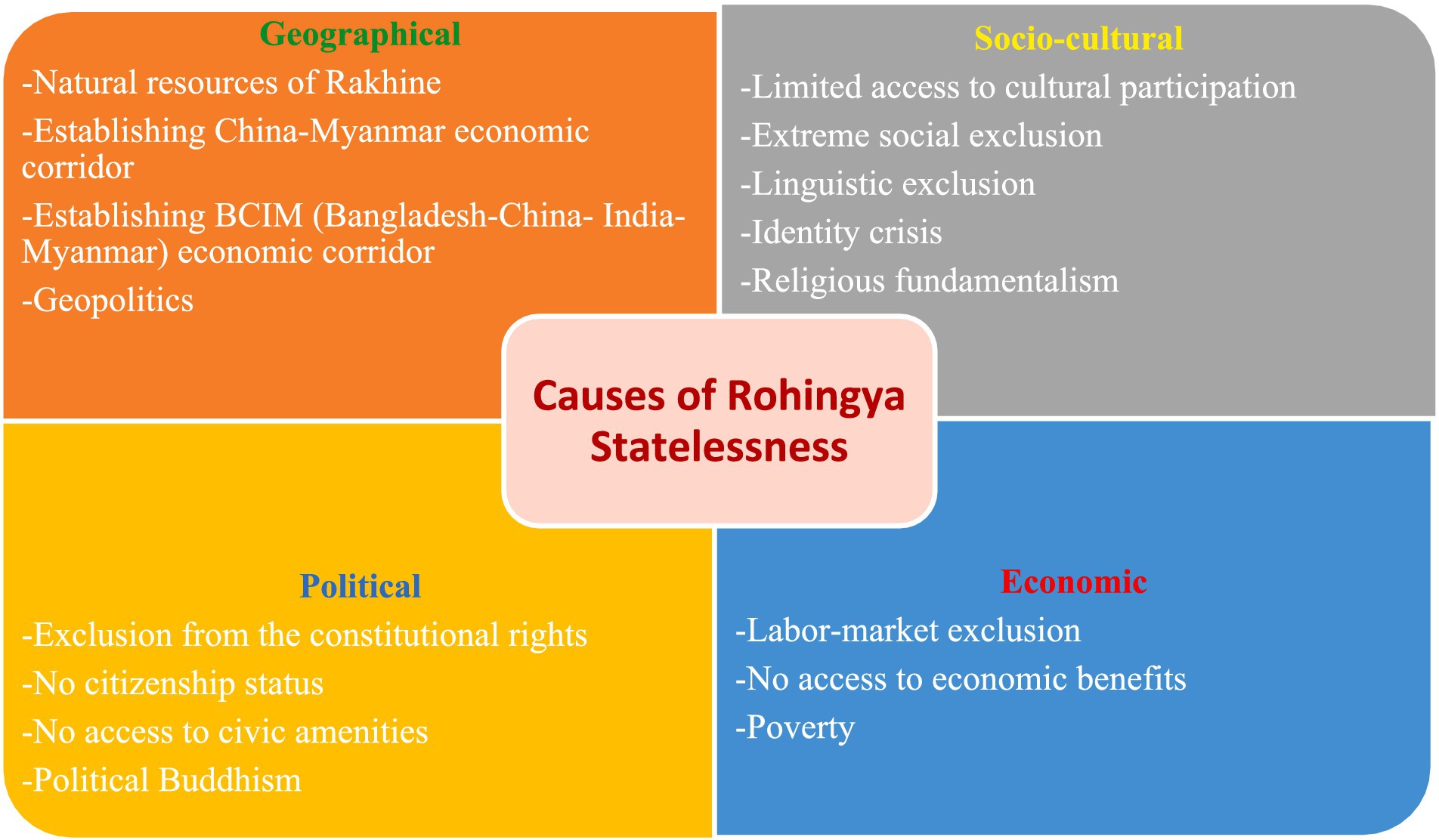

This study argues that Rohingyas are stateless because they are the victim of four factors: the logic of illegal aliens (former Bangladeshi people who illegally entered Myanmar); the enemy discourse (collaborators to British armies while Myanmar was fighting for its independence from British rule); the “doctrine of Islamic terrorism”; and foreign interests in the Rakhine State. In this section, the researcher will explain these four factors.

The logic of illegal aliens

Historically, the Rohingya community has been living in the Rakhine (the then Arakan) state for a long period. Although people of the Rohingya community have been living in Myanmar for a long time, they are still considered illegitimate settlers or immigrants from Bangladesh by the majority of Myanmar citizens. The first sign of Muslim presence in the Myanmar region was in the 1430s when the Bengali Muslims established their settlements in this area with “Naramekhla Min Saw Mon,” the last king of the Launggyet dynasty (renowned as Suleiman Shah, the founder of Arakan’s prominent Mrauk-U dynasty) (Chan, 2005). From the nineteenth century onwards, the northern part of Arakan (Rakhine state) was linked to British India through an imperial nexus of peoples’ movement, transportation, and governance because Burma was administered by the then British government as part of British India. During the British colonial period between 1824 and 1948, labor migration from Bengal to Burma was considered a significant internal migration. As a result of the 1942 Arakan massacres, the then British government armed the Muslims of the northern part of Arakan to serve as a buffer zone between the British and Japanese forces, which sparked inter-communal tensions within the region. Following the British withdrawal, communal violence broke out between Buddhist Rakhine supporters of Japan and Rohingya Muslim villagers who supported the British (Yegar, 1972: 95). An Arakanese Muslim group tried to unite Maungdaw and Buthidang in East Pakistan after Burma gained independence in 1948, but Muhammad Ali Jinnah (the founder of Pakistan) and the Burmese Constituent Assembly rejected the idea. The Myanmar government began classifying Rohingya minority people as “illegal immigrants” in this context (Tinker, 1957: 357).

Nevertheless, the Rohingyas were represented in Myanmar’s parliament, and several Rohingyas held a number of prominent government positions, including two female members of parliament. Following the 1956 general election, six parliamentarians were elected to the Burmese parliament, and Sultan Mahmud (the Ex Rohingya-politician in the then British India) was appointed health minister in Prime Minister U Nu’s cabinet. In 1960, Mahmud rejected the idea of a unified Arakan province, proposing that either the Northern part of the Arakan state should be made a separate province or controlled by the central government. In response to Jinnah’s refusal to admit the northern Arakan region within Pakistan, several Rohingyas formed the Mujahid Party, which aspired to create an independent Islamic state in the northern-Arakan area (Tinker, 1957: 56). Pakistan sent an early warning to the Myanmar government in 1950 about Burmese atrocities against Rohingya Muslims. Subsequently, after a lengthy negotiation settlement, the government of Pakistan decided to stop supporting the Rohingya Mujahids and arrested their leader Cassim (Qasim) in 1954. In the same year, Burmese troops intensified their counter-insurgency operations and suppressed the Arakan rebellion (Nu, 1975: 272).

The researcher argued that language is a vital issue in defining ethnicity and nationality because linguistic wars are consistent with real-world violence. During their struggle for citizenship in Pakistan, a Muslim-majority nation-state divided from British India, the Rohingya Arakan Mujahideen Party (RAMP) insisted on using the Urdu script. Although the Rohingya Arakanese Muslim Autonomy Movement wanted autonomy in independent Burma, there was a campaign to accept the Burmese script for their language. The 1952 language issue marked a violent conflict between the Pakistani government and Bengali-speaking students in East Pakistan’s capital (Dhaka) that almost turned Urdu’s claim to the Rohingya language into a betrayal. Due to the similarities between the Rohingya language and the Chittagongian dialect of the Bengali language, the Rohingya Muslims’ adoption of Urdu as a language is treachery because the Urdu-speaking Pakistani government was oppressing their ethnic brothers in East Pakistan. Burmese, Urdu, Nagori, and Hanifi are just a few of the Rohingya language scripts that bear witness to the struggle of the Rohingyas to maintain their identity on the increasingly harsh borders of different nations-states. It demonstrates the endeavors of the Rohingya minority to seek recognition and refugee status across different borders and cultures. This linguistic and regional vagueness haunts the “stateless” identity of the Rohingya community, which was formed on the battlegrounds of the Second World War and reshaped in the border areas of Burma (present Myanmar), Pakistan, and contemporary Bangladesh. Moreover, it allows the Myanmar government to continue propagating the misconception that the Rohingya Muslims are essentially “Bengali-speaking migrants” and foreigners living in their country.

Using the excuse that Rohingyas are not Myanmar nationals but Bangladeshi “resident foreigners” who do not speak Burmese and do not belong to any of Myanmar’s numerous ethnic groups, the military forces of Myanmar had resorted to violence against this minority. Since the Rohingya people have been stripped of their citizenship status under the Myanmar Citizenship Act-1982, armed violence against them is an extension of unequal government strategies. Therefore, the Myanmar government has been able to exploit this legal loophole in order to continue its recent suppression of the Rohingya minority indefinitely. Approximately one million stateless Rohingya refugees who fled from the northern area of Myanmar’s Rakhine state for fear of violence and ethnic cleansing are now living in various camps in Bangladesh.

The enemy discourse

Rohingya Muslims have a long history of being brutally attacked by the military-ruled Myanmar government. Myanmar’s brutality against this linguistically different ethnic minority has astonished people worldwide who are bewildered by the nature of this violence. Official records from the British archives demonstrate that the current situation of the Rohingya minority has its roots in the communal violence that erupted between the Rohingya Muslims and the Rakhine Buddhists during and after the Second World War due to Rohingyas’ participation in that war. Burma was ruled by the British government as a province of the then British India from 1824, and in 1937 Burma was separated and declared a separate colony of the British Empire. To counterbalance the influence of the “less dependable” Burmese and to continue stable imperial rule, imperial bureaucrats in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century encouraged widespread migration of “loyal” Indians. These conflicting allegiances shaped British military tactics in the Allied Burma Campaign during the Second World War. The British government recruited numerous Rohingya Muslim uneducated agricultural workers of the then northern Arakan to fight alongside the British-led “Fourteenth Army” against the forces of Japan during the Second World War. The Muslims of northern Arakan acted as a V-force because the then British government promised that a “Muslim national territory” would be given to the Rohingya Muslims in exchange for their assistance (Yegar, 1972: 95). Aung San (father of current Burmese politician, diplomat, and ex-State Counsellor of Myanmar Aung San Suu Kyi) led “The Burmese National Army,” which fought alongside the Japanese during the Second World War in exchange for independence from Britain. The Second World War also witnessed an eruption of communal violence between the Rohingya Muslims who supported the British and Rakhine Buddhists who helped the Japanese. Therefore, with the Japanese advancement, Muslims escaped from Japan-controlled Buddhist-majority regions to British-controlled Muslim-inhabited northern Arakan, sparking the opposite “ethnic cleansing” within the British-controlled territories (Christie, 1998: 164, 165–167). When the British troops brought the Rohingya refugees back to their village communities in 1943, tensions erupted again between the two communities in retaliation for what had happened during the Second World War. This communal violence escalated to such an extent that the British military officials declared Akyab a “protected region” in order to prevent the Rohingya Muslims from returning to their hometowns and stop communal carnage between Rohingya Muslims and Rakhine Buddhists. Following the British withdrawal from Arakan and the subsequent arrival of Japanese forces, the Buddhists promptly took drastic measures against Muslims, forcing them to flee to the northern part of Arakan state and East Bengal. On the other hand, the Buddhists were primarily concentrated in the southern part of Arakan, and in addition, both sides suffered heavy losses.

During the Second World War, the British merchant marine was manned by roughly 20 percent Rohingya sailors, who were identified in British archives as “far more industrious and productive than the Arakanese.” The British documents further mentioned that certain Rohingya sailors who served in the British navy were “excellent seamen.” For this reason, the British government was more sympathetic to Rohingya Muslims than Rakhine Buddhists. Though the second world war ended with the surrender of Japan in August 1945, the communal tension between the Rohingya Muslims and the Rakhine Buddhists continued, and the remaining weapons from World War II helped Rohingya Muslims and Rakhine Buddhists insurgents to re-arm themselves by 1946 (Sarkar, 2019). The British government divided British India into India and Pakistan in August 1947 on the basis of religion. India gained independence as a Hindu-majority country, while Pakistan gained independence as a Muslim-majority country. Although Burma received its independence from British rule on 4th January 1948 amidst fierce competition among different ethnic minority communities within the border areas, violent activities resumed in the Rakhine state shortly after independence.

The British archive documents demonstrate that a considerable number of Rohingya insurgents were “ex-army members” who launched attacks on the Burmese military’s “regular forces flanks” before fleeing to the mountains and forests. During the 1950s, a unit of Rohingya Muslims, known as Mujahideen, resorted to violent-armed struggle and expelled both non-Muslim and non-allied Muslim villagers from Maungdaw, Buthidang, and Rathdang (Tinker, 1957: 56), resulting in about 13,000 Rohingya Muslims fleeing to neighboring Pakistan and India who were never allowed to return to their homeland (International Crisis Group, 2014). The Burmese government used Rakhine Buddhist insurgents, minorities in the Rakhine state, by providing weapons against the Rohingya Muslims to repel anti-government attacks, demonstrating an initial blueprint of governmental support for violent activities against the unfortunate Rohingya Muslim minority (Sarkar, 2019).

However, the Rohingya ethnic group leaders had two strategic options for assimilating into the surrounding countries: the first was the division of South Asia, and the second was the independence of Burma from the British Empire. But unfortunately, this ethnic minority failed to assimilate properly with independent Burma due to their participation in the Second World War on the British side and against the “Burmese National Army.” The “Razakar Bahini” supported Pakistan during the liberation war of Bangladesh, which was similar to the Rohingya minority’s support of the British government during Myanmar’s struggle for independence from British rule. The researcher termed this situation as “the enemy discourse,” which is one of the main reasons behind the “stateless identity” of the Rohingya Muslim minority. As long as members of the international community do not grasp the roots of the current violence in the Second World War and how it is implicit in the Rohingya language, they will be unable to design appropriate strategies to solve this current political and humanitarian predicaments.

The doctrine of Islamic terrorism

Unlike the Rohingyas, who are Muslim minority communities, the majority of Myanmar’s population is Buddhist. The Rohingyas were treated inhumanely by the mainstream Buddhist population of Myanmar when the government refused to recognize them as Burmese citizens. Moreover, Rohingyas are consistently hated, humiliated, and treated as subhuman by most of the Buddhist political elites and leaders of Myanmar. The Buddhist spiritual fundamentalists claimed and trusted that Rohingya Muslims might control the Rakhine’s Buddhist culture and society. The Rohingyas, in their view, represented a threat to the Buddhist faith, culture, and lifestyle as well as a gateway to the “Islamization of Myanmar” (Wolf, 2015). This cultural difference leads to ferocious and inter-religious hostilities. The researcher argued that the government of Myanmar and political leaders feared “the doctrine of Islamic terrorism.” Ideologically driven terrorist attacks or movements, notably religiously-inspired ones, perpetrated by individuals and terrorist groups that amenably announce Islamic motives for their activities are referred to as “Islamic terrorism.” The military-dominated Myanmar government is using the concept of “Islamic terrorism” to justify the recent genocide against the Rohingya ethnic minority. Accordingly, the government targeted the Rohingya minority community for their religious identity, which differs from the Buddhist religious belief, identity, tradition, and culture. Hence, religious identity was one of the main reasons behind the ethnic cleansing in Myanmar. Religious fundamentalism is an additional cause for the statelessness of this community.

In this section, the researcher examine the August 2017 genocide against the Rohingya minority, claiming that the ethnic cleansing in the Rakhine state was, therefore, primarily motivated by religious identity. Even though the Myanmar government has categorically refused the allegations of genocide, this case shows how the phenomena of Islamophobia or anti-Muslim racism inclined, permitted, indorsed, and terminated in a genocide whose effects are still being felt today. According to critical race theorists (Khaled Beydoun, Nasar Meer, Brian Klug, Iman Attia, and Fanny Müller-Uri), postcolonial scholars, and feminist thinkers, Islamophobia is usually believed to be associated with the “othering” of Muslims in settler communities and countries of the global north (United States, Australia, United Kingdom, France, Canada, Germany), with much existing discourse focusing on the subject of the “war on terror” (Bakali, 2021). Islamophobia has been identified in Muslim media as “honor-based violence,” with coverage of terrorism-related films, media representations about terrorist attacks and obstructed conspiracies, news reports, and stories about Muslims involved in domestic violence or gender-based violence. However, it is increasingly being used to describe structural racism and anti-Muslim violence across the southern countries of the world and other aspects of social injustice (Alsultany, 2012). The recent atrocities against the Rohingya minority in Myanmar have been revived as part of the country’s legalization of the “war on terror”.

The researcher argued that the Rohingya Solidarity Organization (RSO), Arakan Rohingya Islamic Front (ARIF), Rohingya Patriotic Front (RPF), Rohingya Liberation Organization (RLO), Itihadul Mozahadin of Arakan (IMA) are some radical Rohingya organizations that are presently very dynamic on the border areas of Myanmar-Bangladesh. These extremist organizations have demanded the fundamentalist idea of establishing a separate Islamic state which is a significant threat to the Myanmar government. Moreover, several significant Buddhist extremist movements in Myanmar, private sector Islamophobia and structural Islamophobia in Myanmar were responsible for the statelessness of the Rohingya minority. In particular, it reveals that due to the lack of a well-coordinated and united opposition to the military regime in Myanmar, institutional and private Islamophobia collectively led to genocide since the beginning of military rule (Bakali, 2021). In the light of the “war on terror,” the annoying argument employed to justify state-sponsored brutality and ethnic cleansing in Myanmar shares some features with Islamophobic tendencies in some southern parts of the world (Sri Lanka, India, China, Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan), a term that refers to the global battle against terrorism. Thus, the statelessness of the Rohingya community is exacerbated by religious fundamentalism, Islamic terrorism, and Islamophobia, which are distinct factors.

Foreign interests in the Rakhine state

Rakhine is a very resourceful state. It is located near the Bay of Bengal and filled with oil, gas, coal, and many other valuable minerals. Thus, the Myanmar government always supports Rakhine Buddhist fundamentalists for safeguarding their benefits. While the interest of the Buddhist group was at risk, then conflict eventually started. During the conflict period, the Myanmar government condemned the Rohingya community, including other brands of Buddhist groups. Thus, this geographical aspect is liable for the growth of inter-communal, inter-ethnic, and inter-religious conflicts in the Rakhine state (Wolf, 2015).

Although Rakhine is resourceful, it is one of the most underprivileged regions of Myanmar. Due to the resourcefulness of Rakhine, the anti-Muslim movement exists in this state. Myanmar’s government is always interested in establishing its control over the resources of Rakhine. But the government is unwilling to take steps for developing the structures and other amenities within this state. Currently, the economic openness process is getting maximum attention from national and global viewpoints. For this reason, countries like China and India are trying to establish economic zones by taking different massive projects such as “The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor,” “Kaladan Multi-modal Transit Transport Project,” “The Belt and Road Initiative,” etc.

The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CEMC) connects Yunnan via the Mandalay by developing a high-speed rail and new road network from Yangon and Kyakphyu (Rakhine coast) and forming new industrial zones. The massive project under this corridor also involves the expansion of the Kyakphyu seaport and the formation of a Special Export Zone (SEZ). However, the broad umbrella of “The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)” is linked to this economic corridor, creating an innovative urban development concept for a new metropolis inherited from Yangon. Under this economic corridor, the government of Myanmar has accepted nine projects in the Kachin and Shan states and expanded the border economic cooperation zone.

The Kaladan Multimodal Project, the most ambitious project aimed at connecting India and Myanmar by sea, is a joint venture between the Indian and Myanmar governments. The project will connect the East-Indian seaport of Kolkata with the Sittwe seaport in the Rakhine state of Myanmar by sea, via the “Kaladan” River from Sittwe to Paletwa, by road from Paletwa to the Indian border and Myanmar, and finally to Lawngtlai in Mizoram via the road. Through this project, India will get a multipurpose platform for the shipment of cargo from Kolkata port to Myanmar and towards the landlocked northeastern part of India (especially the Seven Sisters) via Myanmar. This new sea route will reduce distance and transportation costs and boost economic development and commercial-strategic relations between India and Myanmar. Myanmar’s government is keen to preserve the interests of those countries, and control over the Rakhine state is a prime factor in this context. Accordingly, the government started ethnic cleansing in the Rakhine state through “clearance operations,” and Rohingyas became stateless.

Discussion: the process of Rohingya exclusion

To understand why and how Rohingyas are stateless, the researcher precisely examined the objectives of this study. This study found various reasons for excluding the Rohingya community from their citizenship rights through secondary data analysis. Based on the study’s findings, in this section, the researcher will describe the process of Rohingya’s exclusion and how the Myanmar government excluded this community from their citizenship status. Consequently, this community is deprived of fundamental human rights and faces violent activities.

In this paper, the researcher argues that Myanmar expelled Rohingyas from their country by imposing the blame on them and was unwilling to return over a million Rohingyas from Bangladesh—a host country for them. The article also finds that the international community is least concerned about the genocide and expulsion of the Rohingyas because of Myanmar’s communal agenda and foreign countries’ economic interests in the Rakhine state. Although history shows that Rohingya Muslims have lived in Myanmar for centuries, they failed to get entrance into Burmese society. Having citizenship is the central prerequisite for enjoying all rights and privileges within a sovereign state, but Rohingyas are deprived of this citizenship status (Ullah, 2016). The Government of Myanmar (GOM) automatically deprived this community of its most basic human rights by excluding Rohingyas from their citizenship status.

By using innumerable processes, the military-dominated government and political authorities of Myanmar gradually excluded the Rohingyas from their social, economic, political, and cultural rights. Due to their religious identity, it is very challenging for Rohingyas to get a passport, job, employment, good schooling, legal marriage, proper medical treatment, etc. (Gettleman, 2017). Monetary influence or labor market exclusion is basically a vital process behind the Rohingya statelessness. Due to economic exclusion, poverty, and inequality identity crisis is created in the Rakhine state. Numerous driving aspects, like political Buddhism, poverty, inequality, divergence, etc., are liable for the statelessness and exclusion of this community. “Political Buddhism” is a prime factor in creating identity crisis, violence, and divisiveness within Myanmar. Political Buddhism is the result of extreme religious nationalism, and it has generated a society in Myanmar that has excluded the Rohingya community and permitted them to meet with violence (please see Figure 3).

The Burmese identity is a provoking factor to discriminate against individuals in Myanmar who are not included in this identity (Cheesman, 2017). As Rohingyas are not included in the constitution of Myanmar as a citizen, they are discriminated against in Myanmar and become stateless. On 25th August 2017, ethnic cleansing started in the Rakhine state of Myanmar. The army of Myanmar sponged out the Rohingya settlements by uprooting their households, mosques, lands, corrals, grain stores, and even shrubs into sandbanks of ash. Consequently, the Rohingya Muslims fled from their homeland Myanmar across the sea and took shelter in different neighboring states, namely Bangladesh, India, Thailand, and Malaysia (Gettleman, 2017).

Rohingyas are deprived of their fundamental human rights by the Myanmar government, political authorities, spiritual leaders, and mainstream people. For expunging this Muslim minority community from Rakhine, the military of Myanmar burnt their villages, started genocide, raped women and young girls, and killed older adults and infants by different terrorist tactics and violent activities. If the Myanmar government grants the Rohingya minority basic human rights, Myanmar’s mainstream Buddhist population will be at risk of employment, monopoly trade, civic amenities, and other opportunities. This fear is also liable for the process of ethnic cleansing in Myanmar. That means religious, political, and economic factors are accountable for the Buddhist indignation against the people of the Rohingya community (Wolf, 2015). After considering all the factors, the researcher think that geopolitics and Myanmar’s economic interests are more significant than other factors behind the statelessness of the Rohingya minority. Thus, the military-dominated government of Myanmar started ethnic cleansing in the Rakhine state through different violent activities, which compelled the Rohingyas to flee from Myanmar. Consequently, they have become stateless and are living as refugees in Myanmar’s neighboring countries.

Conclusion

This study addresses an important and timely issue regarding the statelessness of the Rohingya community in Myanmar, paying attention to the intellectual discourses on humanity, ethnicity, identity crisis, stigmatization, and minority rights. One of the most persecuted communities globally, the Rohingya have been deprived of their fundamental human rights and citizenship status by Myanmar’s “1982 Citizenship Act”. This study has shown why and in what way the Rohingya people faced ethnic cleansing by the Myanmar army and fled away to the neighborhood countries like Bangladesh, India, Thailand, Malaysia, etc., by being stateless. History shows that this community faced ethnic cleansing in 1979, 1991, and 2016. But on 25th August 2017, they met the most brutal ethnic cleansing in history. Military-controlled Myanmar government burnt their homes and lands, killed them brutally, and raped women and children. The Myanmar government also restricts their social benefits, such as taking proper education, rights to move freely, rights to work and employment, etc. In this paper, the development of an analytical framework dictates a structural approach that helps understand the complexity and depth of the Rohingya issue. The novelty of this study lies in the fact that it provides a thorough systematic review of existing research by analyzing extensive relevant local and global literature on the Rohingya crisis. The central argument of this research focuses on the issue of minority statelessness which adds to the credibility, reliability, and validity of this paper.

This study has identified many reasons behind the statelessness of the Rohingya minority from the theoretical perspectives of Hilary Silver, Pierre Clavel, and Ruth Levitas. The analytical framework developed by the present study found that political Buddhism, attachment to Islamic terrorism, drug trafficking, terrorist activities, geopolitics, economic benefits of the foreign countries, etc., are some of the main culprits behind the statelessness of this community. Myanmar people do not accept Rohingyas as citizens because they always consider Rohingyas outsiders. Accordingly, their ethnic identity is gainsaid by the Myanmar government and the general people. Most of the people in Myanmar are Buddhists, and they believe that the Muslim Rohingya community will create a significant threat to them. Moreover, Rakhine is one of the most resourceful states of Myanmar, and countries like India and China are very interested in the resources of Rakhine. For this reason, the Myanmar government is trying to take control of this state by using terrorist tactics to uproot the Rohingya community. Consequently, people of this Muslim minority community have become stateless, have sought refuge in neighboring countries, and leading a life like prisoners.

This study proposes some recommendations for resolving this unique inhuman condition. The United Nations (UN) should address the issue of genocide and provide high-level support for the Rohingya crisis. As a regional organization, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) could play a leading role in this regard. Through the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), Muslim countries can play an essential role in overcoming this problem. The Bangladesh government should negotiate with the Myanmar government for the safe repatriation of Rohingyas. On the issue of repatriation, the Myanmar provincial government can actively support and promise to the Rohingya people. Finally, this study strongly recommends that various non-governmental organizations and international humanitarian organizations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Doctors Without Borders, Refugees International, OXFAM, etc., take appropriate steps to resolve the issue of the Rohingya predicament.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albert, E., and Maizland, L. (2020). What forces are fueling Myanmar's Rohingya crisis? Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved August 3, 2021, Available at: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/rohingya-crisis

Ali, M. N. (2022). Book review: Nasir Uddin, the Rohingya: an ethnography of ‘subhuman’ life. South Asia Res. 42, 452–454. doi: 10.1177/02627280221115676

Alsultany, E. (2012). Arabs and Muslims in the media: Race and representation after 9/11. New York, USA: New York University Press.

Amnesty International. (2017). Myanmar: Rohingya trapped in dehumanising apartheid regime. Retrieved January 16, 2020, Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2017/11/myanmar-rohingya-trapped-in-dehumanising-apartheid-regime/

APHR (ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights). (2015). The Rohingya crisis and risk of atrocities in Myanmar: an ASEAN challenge and call to action. Retrieved January 16, 2019, Available at: https://burmacampaign.org.uk/media/APHR-Report-Rohingya-Crisis-and-Risk-of-Atrocities-in-Myanmar-final.pdf

Bakali, N. (2021). Islamophobia in Myanmar: the Rohingya genocide and the ‘war on terror’. Race & Class. 62, 53–71. doi: 10.1177/0306396820977753

BBC News. (2012) Burma unrest: Rakhine violence 'displaces 30,000′. BBC News. Retrieved November 14, 2017, Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-18449264

Beyrer, C., and Kamarulzaman, A. (2017). Ethnic cleansing in Myanmar: the Rohingya crisis and human rights. Lancet 390, 1570–1573. Retrieved December 13, 2018, from. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32519-9

Bhattacharjee, M., and Hoque, L. (2019). Representation crisis of Rohingyas: an analysis of the situation of Rohingya women and children. J. Soc. Stud. 162, 1–19.

Chan, A. (2005). The development of a Muslim enclave in Arakan (Rakhine) state of Burma (Myanmar). SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research, 3(2), 396–420. Retrieved March 4, 2020, Available at: https://www.soas.ac.uk/sbbr/editions/file64388.pdf

Chaudhury, S. B. R., and Samaddar, R. (2018). The Rohingya in South Asia: people without a state. India: Routledge.

Cheesman, N. (2017). How in Myanmar "national races" came to surpass citizenship and exclude Rohingya. J. Contemp. Asia 47, 461–483. Retrieved January 12, 2018, from. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2017.1297476

Chemali, Z., Borba, C. P. C., Johnson, K., Hock, R. S., Parnarouskis, L., Henderson, D. C., et al. (2017). Humanitarian space and well-being: effectiveness of training on a psychosocial intervention for host community-refugee interaction. Med. Confl. Surviv. 33, 141–161. doi: 10.1080/13623699.2017.1323303

Choudury, A. H., and Fazlulkader, M. (2019). Rohingya refugee crisis in Bangladesh: an analysis of the socio-economic and environmental problems in Bangladesh Myanmar border area. Europ. J. Res. 87:106.

Christie, C. J. (1998). A modern history of Southeast Asia: decolonization, nationalism and separatism. London: I.B. Tauris Publishers.

Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar (2008). The state peace, and development council (SPDC). Naypyidaw, Myanmar: Printing & Pub. Enterprise. Ministry of Information.

Dey, S. (2018). Adverse Rohingya impacts on Bangladeshi economy and its solutions. Am. J. Trade Policy 5, 81–84. doi: 10.18034/ajtp.v5i2.438

DIMÉ, Mamadou dit ndongo. (2005). Social exclusion in the sociological literature of the french-speaking world: paradox and theorizations. Social Network Journal. 3.

Faisal, M. M. (2020). The Rohingya refugee crisis of Myanmar: a history of persecution and human rights violations. Int. J. Soc. Polit. Econ. Res. 7, 743–761. doi: 10.46291/IJOSPERvol7iss3pp743-761

Farzana, K. F. (2017). Memories of Burmese Rohingya refugees, Contested Identity and Belonging. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gettleman, J. (2017), Fate of stateless Rohingya Muslims is in antagonistic hands. The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2019, Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/03/world/asia/rohingya-myanmar-bangladesh-stateless.html

Hossain, S., and Hosain, S. (2019). Rohingya identity crisis: a case study. Saudi J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 4, 238–243. doi: 10.21276/sjhss.2019.4.4.3

Hossain, M. A., Ullah, A. A., and Mohiuddin, M. (2022). Rohingya refugees in the pandemic: crisis and policy responses. Global Pol. 14, 183–191. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.13156

Human Rights Watch. (2015). Thailand: Mass graves of Rohingya found in trafficking camp. Retrieved November 25, 2019, Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/05/01/thailand-mass-graves-rohingya-found-trafficking-camp

Human Rights Watch. (2017). Burma: Widespread Rape of Rohingya Women, Girls. Retrieved November 26, 2020, from https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/11/16/burma-widespread-rape-rohingya-women-girls

Hutcherson, K., and Olarn, K. (2015) At least 30 graves found in southern Thailand, and a lone survivor. CNN. Retrieved August 12, 2020, Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2015/05/02/asia/thailand-mass-graves/

International Crisis Group. (2014). Myanmar: The politics of Rakhine State. Asia report no. 261. Brussels: Belgium. Retrieved January 14, 2022, Available at: https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1294758/1002_1414163665_261-myanmar-the-politics-of-rakhine-state.pdf

Kaveri (2017). Being stateless and the plight of Rohingyas. Peace Rev. 29, 31–39. doi: 10.1080/10402659.2017.1272295

Khuda, K. E. (2020). The impacts and challenges to host country Bangladesh due to sheltering the Rohingya refugees. Cogent. Soc. Sci. 6:943. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2020.1770943

Kingston, L. N. (2015). Protecting the world's most persecuted: the responsibility to protect and Burma's Rohingya minority. Int. J. Hum. Rights 19, 1163–1175. doi: 10.1080/13642987.2015.1082831

Levitas, R. (2005). The inclusive society? Social exclusion and new labour. 2nd Edn. UK: Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.

Lewis, D. (2019). Humanitarianism, civil society and the Rohingya refugee crisis in Bangladesh. Third World Q. 40, 1884–1902. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2019.1652897

Mathieson, J., Popay, J., Enock, E., Escorel, S., Hernandez, M., Johnston, H., et al. (2008). Social Exclusion, Meaning, Measurement and Experience and Links to Health Inequalities: A Review of Literature. WHO Social Exclusion Knowledge Network Background Paper 1, Institute for Health Research, Lancaster, Lancaster University.

Milton, A. H., Rahman, M., Hussain, S., Jindal, C., Choudhury, S., Akter, S., et al. (2017). Trapped in statelessness: Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 1–8. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14080942

Rawal, N. (2008). Social inclusion and exclusion: a review. Dhaulagiri J. Sociol. Anthropol. 2, 161–180. doi: 10.3126/dsaj.v2i0.1362

Rohingya Crisis. (2017). Human rights watch. Retrieved March 16, 2018, Available at: https://www.hrw.org/blog-feed/rohingya-crisis

Sabbir, A., Al Mahmud, A., and Bilgin, A. (2022). Myanmar: ethnic cleansing of Rohingya. From ethnic nationalism to ethno-religious nationalism. Conflict Stud. Quart. 39, 81–91. doi: 10.24193/csq.39.6

Sarkar, J. (2019). Perspective | how WWII shaped the crisis in Myanmar. Wash. Post. Retrieved September 14, 2021, Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/03/10/how-wwii-shaped-crisis-myanmar/

Sen, A. (2000). Social exclusion: Concept, application, and scrutiny. Manila, Philippines: Asian Development Bank.

Shohel, M. M. (2023). Lives of the Rohingya children in limbo: childhood, education, and children’s rights in refugee camps in Bangladesh. Prospects 53, 131–149. doi: 10.1007/s11125-022-09631-8

Silver, H. (1994). Social exclusion and social solidarity: three paradigms. Int. Labour Rev. 133, 531–578.

Storai, Y. (2018). Systematic ethnic cleansing: the CASE study of ROHINGA community in Myanmar. J. South Asian Stud. 5, 157–168. Available at: https://esciencepress.net/journals/index.php/JSAS/article/view/2485

Tinker, H. (1957). The Union of Burma: A study of the first year of Independence. London: Oxford University Press.

Uddin, N. (2022). The Rohingya crisis: Human rights issues, Policy Concerns and Burden Sharing. India: Sage.

Ullah, A. A. (2011). Rohingya refugee to Bangladesh: historical exclusions and contemporary marginalization. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 9, 139–161. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2011.567149

Ullah, A. A. (2016). Rohingya crisis in Myanmar: seeking justice for the 'Stateless. J. Contemp. Crim. Justice 32, 285–301. doi: 10.1177/1043986216660811

Ullah, A. A., and Chattoraj, D. (2018). Roots of discrimination against Rohingya minorities: society, ethnicity and international relations. Intell. Disc. 26, 541–565. Available at: https://journals.iium.edu.my/intdiscourse/index.php/id/article/view/1220

Ullah, A. A., and Chattoraj, D. (2023). The untold stories of the Rohingyas: Ethnicity, diversity, and media. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2017). UNHCR distributes aid to Rohingya refugees ahead of Bangladesh winter. UNHCR. Retrieved February 23, 2019, Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/news/briefing/2017/12/5a3399624/unhcr-distributes-aid-rohingya-refugees-ahead-bangladesh-winter.html

Wolf, S. O. (2015,). Myanmar's Rohingya conflict 'more economic than religious.' Deutsche Welle. Retrieved November 14, 2018, Available at: https://www.dw.com/en/myanmars-rohingya-conflict-more-economic-than-religious/a-18496206

Yegar, M. (1972). The Muslims of Burma: The study of a minority group. Wiesbaden, Germany: Otto Harrassowitz.

Zaman, F. (2022). Framing of Rohingya crisis in news: the debate over Rohingya relocation. Jagannath Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 11, 1–21.

Keywords: statelessness, Rohingya community, ethnic minority, Myanmar, genocide

Citation: Bhattacharjee M (2024) Statelessness of an ethnic minority: the case of Rohingya. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1144493. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1144493

Edited by:

Annekathryn Goodman, Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, United StatesReviewed by:

A. K. M. Ahsan Ullah, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, BruneiAizat Khairi, University of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Copyright © 2024 Bhattacharjee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mowsume Bhattacharjee, bW93c3VtZWNjbnVAb3V0bG9vay5jb20=

Mowsume Bhattacharjee

Mowsume Bhattacharjee