95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 27 January 2023

Sec. Political Science Methodologies

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.976756

A correction has been applied to this article in:

Corrigendum: Assessing the public understanding of democracy through conjoint analysis

Global support for democracy is puzzling in the time of alleged backlash toward democracy. Building on recent studies on democratic support that take into consideration heterogeneity in the subjective perceptions of democracy, I conducted a conjoint analysis and examined the trade-offs among various democratic values that the citizens might face when they think of democracy. Using an original dataset of 2,206 respondents, sampled from Japanese adult population, I found that the procedural view of democracy played the most important role when Japanese people evaluated a country's democracy level. In their view, a lack of free and fair elections and disenfranchisement of certain groups were more detrimental to democracy than a shortage of checks and balances, economic growth, and social welfare. In addition, the analysis shows that factors representing the minoritarian view and the substantive view of democracy play an undeniable role in citizens' democracy evaluations, which confirms the discrepancies between how students of democratization conceptualize and how ordinary people think of democracy today.

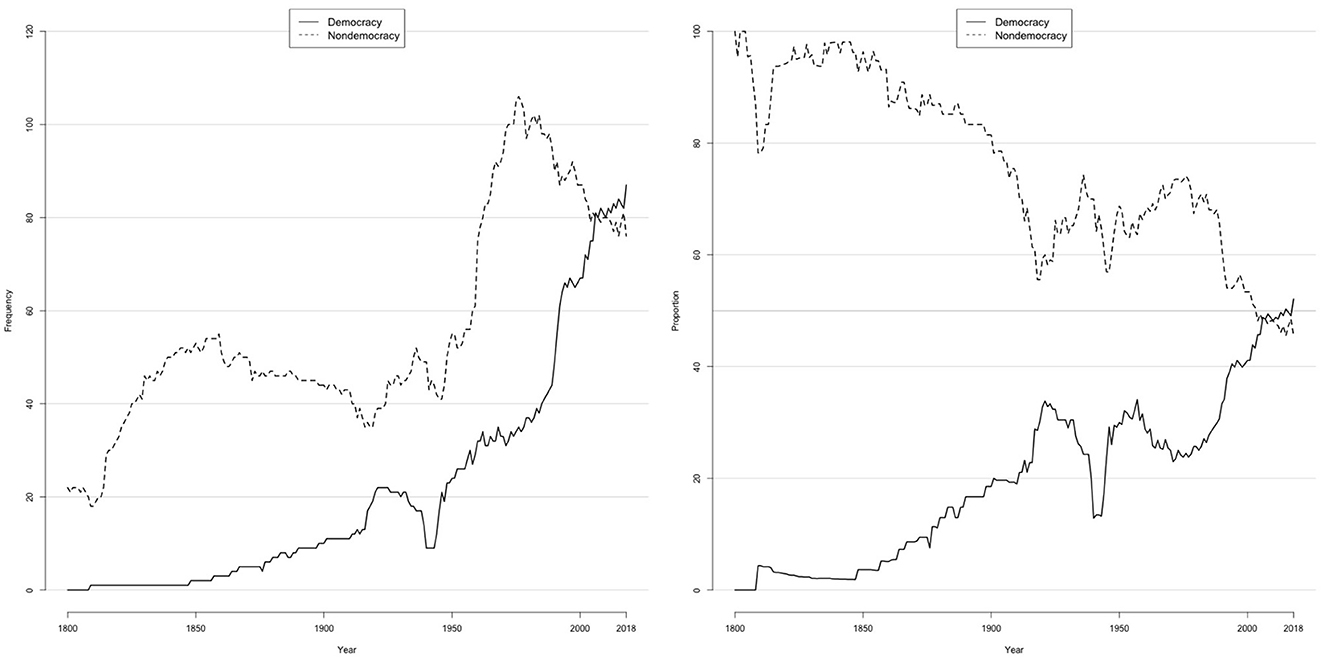

Is democracy decaying and in danger in the present era? Although the number of democratic regimes and the proportion of democratic countries have increased over time (Figure 1), we observe instances of democratic backsliding worldwide (Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018; Haggard and Kaufman, 2021). A growing concern among the citizens and the policymakers is highlighted by the cases of consolidated democracies that are believed to last almost forever (Svolik, 2008), but are a part of this autocratization pattern. The fact that democracies today collapse less by coup d'état, but are put in danger more by democratically elected leaders (Svolik, 2015), complicates the matter. This is the case because the democratic backsliding by elected leaders might proceed gradually, and therefore citizens might not realize the backsliding is indeed in progress.

Figure 1. (Left) Number of democracies and non-democracies from 1800 to 2018. (Right) Proportion of democracies and non-democracies from 1800 to 2018. Using V-Dem data Version 11 (Coppedge et al., 2021), I classified regimes as democracy if the value of electoral democracy index is greater than or equal to 0.5. A regime is deemed nondemocratic if the electoral democracy index is smaller than 0.5.

The growing concern regarding democratic backsliding contradicts global mass support for democracy that some of the survey research demonstrate (Rose et al., 1998; Bratton et al., 2005; Chu et al., 2008; Jamal and Tessler, 2008; Klingemann et al., 2008; Blokker, 2012; Booth and Richard, 2014), even in nondemocratic countries (Maseland and van Hoorn, 2011; Welzel and Alvarez, 2014). Studies on support for democracy have accumulated. To make sense of the gap between the high level of support for democracy and the relative lack of democracy in the real world, recent research has attempted to examine whether individuals have different understanding of democracy when they are asked about their support for it (Mattes and Bratton, 2007; Crow, 2010; Canache, 2012; Cho, 2015).

Innovations have been proposed and implemented for measuring what people think with respect to democracy. Open-ended questions and close-ended questions have been used in survey research (see Shin and Kim, 2018; Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2020 for a review). On the one hand, open-ended questions reveal the properties, which the respondents identify as essential characteristics of democracy. Close-ended questions, on the other hand, enable researchers to investigate the extent to which the citizens differentiate the properties of democracy and how these properties shape their understanding of democracy. Among others, the Asian Barometer Survey develops novel question items that address the issues of identification and differentiation simultaneously, leading to the conclusion that the substantive view of democracy predominates among Asians. Despite the novel empirical strategy that the Asian Barometer Survey devised, there remains room for improvement. Surveys can include diverse attributes of democracy and varied connotations of those attributes. Then, researchers can comprehensively observe the properties, which the respondents identify as essential properties of democracy with varying magnitudes of importance or priority.

To address the possible trade-offs that individuals might face when they think of democracy, I conducted a conjoint analysis with a nationally representative sample of Japanese people. Conjoint analysis is a survey-based experimental method that allows us to observe the characteristics individuals identify as properties of democracy and the degree of emphasis that they place on these properties. My analysis shows that Japanese people, on average, consider the lack of electoral competition and electoral participation to be most detrimental to democracy. In addition, it reveals that other aspects of democracy including the minoritarian view and substantive view play an undeniable role in shaping the popular understanding of democracy in Japan. Thus, the finding corroborates previous studies that demonstrate the multidimensional nature of subjective democracy while offering nuanced observations of citizens' perspective.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. First, I review the literature and summarize previous studies that highlight heterogeneity in the understandings of democracy among the public and try to overcome the problem by implementing open-ended and close-ended questions. Next, I highlight a novel approach taken by the Asian Barometer Survey while discussing the limitations in its empirical strategy. I emphasize the need for an alternative approach to better investigate what individuals identify as properties of democracy and how they use these properties in their regime evaluation. Second, I explicate the merit of conjoint analysis, provide the design of my conjoint analysis regarding democracy evaluation, and demonstrate the result that Japanese people, on average, negatively react to the lack of electoral competition and participation when evaluating a country's democracy. The last section concludes.

In modern times, democracy is deemed a type of political regime that enjoys universal appeal or aspiration (Inglehart, 2003; Dalton et al., 2007; Diamond, 2011; Norris, 2011). This perspective is supported by public opinion research, be it analyses of a regional or global survey project, that the vast majority of people worldwide express support for democracy when they are asked about their preference (Rose et al., 1998; Bratton et al., 2005; Chu et al., 2008; Jamal and Tessler, 2008; Klingemann et al., 2008; Blokker, 2012; Booth and Richard, 2014). Intriguingly, public support for democracy is consistently reported in countries that are usually considered nondemocratic (Maseland and van Hoorn, 2011; Welzel and Alvarez, 2014). These findings let some scholars conclude global diffusion of liberal ideas (e.g., Elkink, 2011).

Global public support for democracy is encouraging, on the one hand, because it demonstrates the legitimacy of democratic regimes while criticizing and rejecting its nondemocratic counterpart, possibly leading to democratic changes worldwide (Mishler and Rose, 2002; Mattes and Bratton, 2007; Shin and Tusalem, 2007; Diamond, 2008). On the other hand, however, this finding does not corroborate the theory of lifelong learning of democracy that emphasizes the role of political socialization and intrinsic regime performance in nurturing the public preference for democracy (Bratton et al., 2005; Mattes and Bratton, 2007; Fails and Pierce, 2010). This is the case because it is impossible for the citizens living in nondemocratic political regimes to learn about democracy. Moreover, using the Asian Barometer Survey Wave 4 data, Shin and Kim (2018, p. 225) find that the citizens living in non-democracies are more satisfied with the way in which their country is governed democratically than the citizens residing in democracies. This indicates the possible discrepancies in what democracy means to ordinary citizens. Having these concerns in mind, scholars started to investigate whether people from different parts of the world share the same understanding of democracy before examining the magnitude of support for democracy.

While individual citizens might hold different understandings of democracy, scholars who conduct empirical studies on democratization generally accept the idea of defining democracy with respect to procedure rather than a source of authority or purpose (Huntington, 1991, p. 6). The procedural minimal definition of democracy (Dahl, 1971) becomes its dominant conceptualization (e.g., Przeworski et al., 2000; Boix, 2003; Coppedge et al., 2008). This serves as a useful analytical concept and the resulting dichotomous measurement of political regimes (i.e., democracy and non-democracy), for instance, allows researchers to draw a clear dividing line between democracies and non-democracies. Hence, scholars are able to study when and why a nondemocratic regime collapses and a democracy replaces it.1

In contrast to that, ordinary citizens might view democracy as an abstract and, at times, contentious concept (Gallie, 1955; Collier and Levitsky, 1997; Collier et al., 2006) as it evokes varied connotations and implications. This is the case because the citizens around the world are exposed to heterogeneous political, economic, and social contexts (Munck and Verkuilen, 2002; Hopkins and King, 2010). Public opinion research indicates that ordinary citizens do not necessarily follow the minimalist definition of democracy (Davidov et al., 2014; Ulbricht, 2018). For example, in his study of Mexico, Crow (2010) documents the varied ways in which people define democracy. While some define it narrowly with respect to elections and political rights, others take a broader view by incorporating substantive outcomes into the definition of democracy.2 A similar conclusion is drawn from the samples collected in Latin America (Canache, 2012) and Africa (Mattes and Bratton, 2007). Likewise, Cho (2015) argues that democracy has a weak cognitive foundation in non-Western countries. He shows that most people in Western democracies are able to distinguish between democratic and authoritarian attributes, whereas this is not the case in the Middle East and South Asia. These studies urge scholars to examine how people understand democracy before asking their affinity to and desire for it (Schedler and Sarsfield, 2007; Shi, 2014; Ferrín and Kriesi, 2016; Wegscheider and Stark, 2020).

Unpacking people's understanding of democracy requires scholars to observe the extent to which the citizens identify the properties of democracy and differentiate them from the properties of its nondemocratic counterparts (Shin and Kim, 2018). Different approaches have been proposed and undertaken to address this point in survey research. Surveys have asked open-ended questions to learn what individuals identify as essential properties of democracy. In addition, using close-ended questions, previous studies investigate the extent to which subjective understanding of democracy corresponds to or deviates from certain concepts of democracy including the procedural definition of democracy.

Typical open-ended questions ask the respondents to list one or more attributes of democracy that come to their mind (Miller et al., 1997; Camp, 2001). This results in a list of properties of democracy to which the citizens attach positive connotations. Baviskar and Malone (2004) ask the respondents to name what they like and dislike about democracy to maintain neutrality. Open-ended question items largely grasp what the citizens identify as properties of democracy.3

Surveys that incorporate close-ended questions are represented by, for instance, the World Values Survey (WVS) Wave 7 in which the respondents are asked to evaluate statements referring to a principle or institutional setting that scholars conceive as the essential attributes of democracy (Haerpfer et al., 2020). These include statements about electoral process, political rights, civil liberties, redistribution of wealth from the rich to the poor, income inequality, obedience to rulers, and the role of army and religion in politics. By assessing citizens' evaluation of each statement, researchers can observe the properties that the citizens perceive as essential to democracy and emphasize more than the others (Zagrebina, 2020).

In both types of survey questions, researchers begin with the concern that the citizens might have different understandings of democracy. The questions help them observe the properties that citizens have in their mind when they think about democracy, leading to the conclusion that popular understandings of democracy are not uniform, but heterogeneous.

Building on this, some scholars use a set of survey items and classify the respondents into particular types of democracy that scholars conceptualize and respondents might conceive of (see Shin and Kim, 2018, p. 229–230, for a review). Among many others, Shi and Lu (2010) propose the distinction between procedure-based liberal conception and a substance-based minben conception of democracy. Norris (2011) makes three categories including procedural, instrumental, and authoritarian. Likewise, Welzel (2013) categorizes democratic understandings into liberal, social, populist, and authoritarian. Kirsch and Welzel (2019) distinguish between the liberal and authoritarian notion of democracy to make sense of the high support for democracy in nondemocratic regimes. This approach helps learn the extent to which individuals' perception corresponds to or deviates from the notions of democracy that scholars develop.

A potential drawback of this approach, however, is an implicit assumption that a certain combination of democratic properties that individuals identify leads to a notion of democracy that they are likely to hold. For example, those who disregard electoral institutions and procedures, but stress economic and social benefits are considered embracing substantive democracy. Although it the type of democracy that people show support for, this approach tends to remain descriptive, resulting in “a great deal of variation in the number and type of conceptual devices proposed to ascertain mass conceptions of democracy” (Shin and Kim, 2018, p. 229). Moreover, by giving a conceptual label to individuals through a classification procedure, the approach might mask the possible trade-offs that individuals face when they evaluate the different properties that relate to democracy. In other words, taxonomies might obscure the way in which individual citizens differentiate among the different properties of democracy with different weights.

Both open-ended and close-ended survey questions that ask the properties of democracy demonstrate a great deal of leverage to draw findings and implications that might be generalizable. This is the case because they allow researchers to mobilize a large scale of individual-level data. However, the fact that the subjective perception of democracy is multidimensional and diverse across individuals calls additional concerns. More specifically, it is important to scrutinize the extent to which a respondent emphasizes an attribute (or a dimension) over another. Two survey items, for instance, from Wave 7 of the WVS clarify this point. Following the text below, respondents are directed to evaluate ten different statements; each of which relates to a certain attribute of democracy (or political regime). For demonstration purpose, I present the first two statements:

Many things are desirable, but not all of them are essential characteristics of democracy. Please tell me for each of the following things how essential you think it is as a characteristic of democracy. Use this scale where 1 means “not at all an essential characteristic of democracy” and 10 means it definitely is “an essential characteristic of democracy.”

Q241: Governments tax the rich and subsidize the poor.

Q242: Religious authorities ultimately interpret the laws.

Suppose that two respondents both give a score of 5 to each item. Yet, they might still be different with respect to the importance that they place on each statement. Respondent A might think that taxing and providing subsidies are a lot more important than the role of religious authorities. Respondent B might think that both statements are equally important. The problem here is that each statement is presented separately in the survey and respondents provide an answer to each question one by one. Thus, respondents might not have thought about the relative importance of each statement. If the survey questions are lumped together, the respondents would need to assess each statement while considering relative weights between them.4

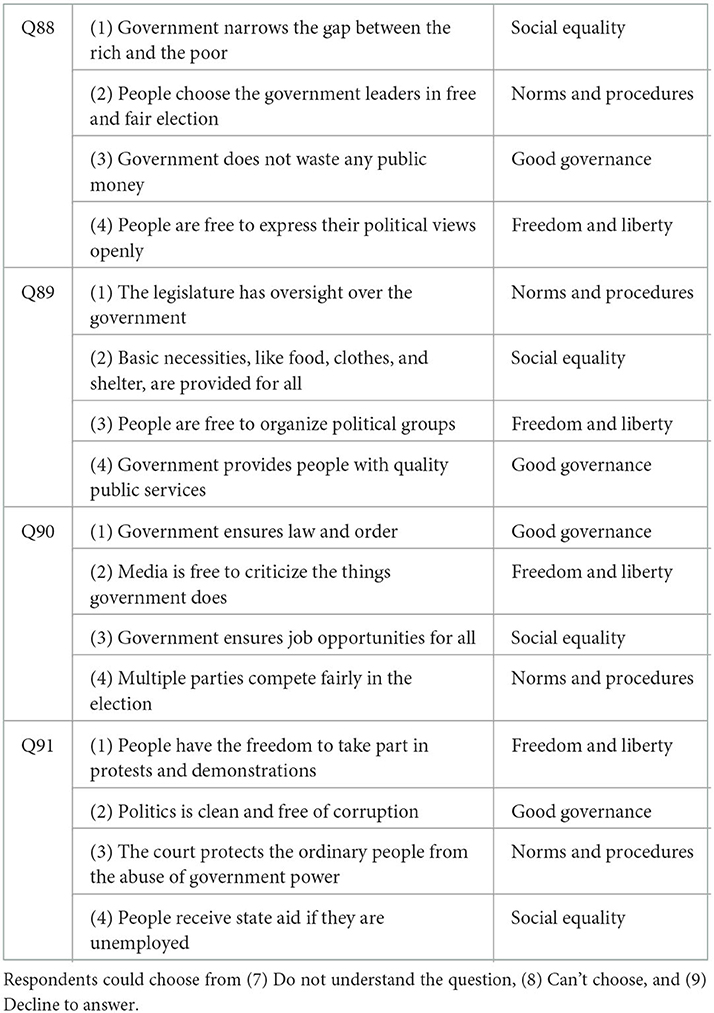

Wave 3 and Wave 4 of the Asian Barometer Survey directly address this issue. In the survey, the respondents are exposed to the statement, “[m]any things may be desirable, but not all of them are essential characteristics of democracy. If you have to choose only one from each four sets of statements that I am going to read, which one would you choose as the most essential characteristics of a democracy?” As Table 1 shows, the respondents see a set of options that represent, good governance, norms and procedure, and freedom and liberty. Social equality and good governance relate to substantive democracy while norms and procedure and freedom and liberty are at the core of procedural democracy. The approach successfully randomizes the four different attributes of democracy to avoid the order effect and asks respondents to name one as the most essential characteristic of democracy (Huang, 2018).

Table 1. The Asian Barometer Survey (Wave 4) items asking the most essential characteristics of democracy.

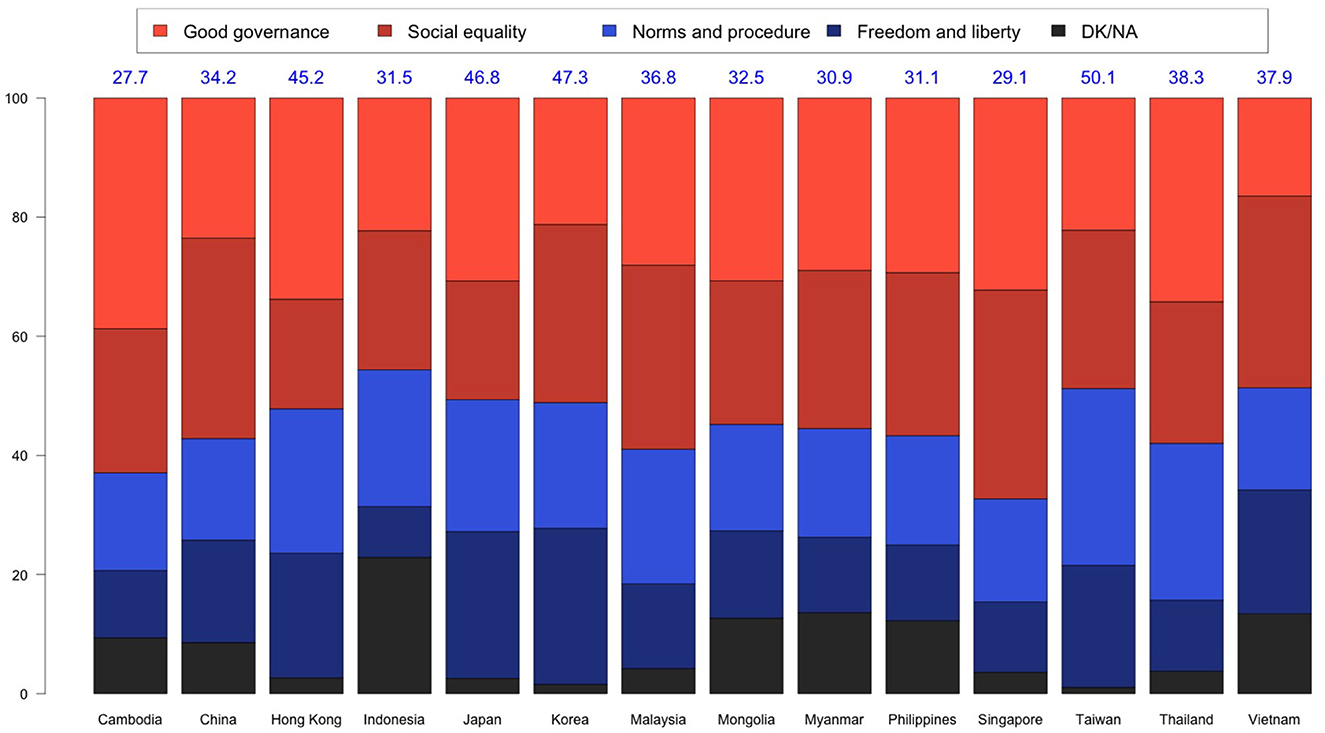

Figure 2 displays the results from fourteen Asian countries and entities. Using the four question items in the Asian Barometer Survey Wave 4 that was fielded in 2014–2016 (Table 1), for each country, I calculate the proportion of respondents who select good governance, social equality, norms and procedure, or freedom and liberty as the most essential characteristic of democracy.5 The proportion of respondents who choose an option representing norms and procedure or freedom and liberty (i.e., attributes that characterize procedural democracy) is highest in Taiwan (50.1%), followed by South Korea (47.3%), Japan (46.8%), Hong Kong (45.2%), Thailand (38.3%), Vietnam (37.9%), Malaysia (36.8%), China (34.2%), Mongolia (32.5%), Indonesia (31.5%), the Philippines (31.1%), Myanmar (30.9%), Singapore (29.1%), and Cambodia (27.7%). This demonstrates diverse views about democracy within and across countries and entities in the region. In addition, it reveals that substantive view of democracy predominates in general, which is consistent with the finding of the previous wave of the survey conducted in 2010–2012 (Huang, 2018, p. 305–307).

Figure 2. The Asian Barometer Survey Wave 4 questions on the Meaning of Democracy (Q88–Q91). The respondents are asked to choose one out of four options as the most essential characteristic of democracy. DK/NA includes those who choose “Do not understand the question,” “Can't choose,” or “Decline to answer”. The number above each bar shows the proportion of respondents who choose the options representing the procedural view of democracy (i.e., Norms and procedure or freedom and liberty).

Although the Asian Barometer Survey Wave 3 and Wave 4 address both identification and differentiation issues when measuring popular understanding of democracy, there remains room for improvement. First, the number of attributes under investigation can be expanded to more than four. Because subjective democracy can have numerous attributes, it will be an important addition if alternative empirical strategy allows researchers to incorporate more than four attributes. Second, and more importantly, the attributes can include both positive and negative connotations. The example from the Asian Barometer Survey Wave 4 implys positive meanings with respect to procedural or substantive democracy. It is uncertain how the respondents would react if the attributes had negative implications. Reflecting this concern, however, inflates the number of combinations of different attributes, which are difficult to implement in face-to-face, interview-based surveys. The limitations in the number and content of the attributes of democracy indicates the need for developing an empirical strategy that allows researchers to comprehensively observe the properties that the respondents identify as essential with varying magnitudes of importance or priority.

Conjoint analysis is a survey-based experimental method that has been widely used in the field of marketing. This is nowadays applied in other fields of social sciences including political science (Hainmueller et al., 2014). In a typical application, researchers construct a pair of hypothetical options with several attributes and let the respondents choose an option and/or evaluate each option in a continuous scale. These attributes have different levels that researchers define prior to the survey. For example, if a scholar conducts a conjoint analysis on preferences of smartphone, the attributes might include weight, storage, memory, color, price, and so on. If the scholar is interested in the color most popular among consumers, she can define the levels of color such as black, silver, red, and blue. Using the pre-defined levels of each attribute, she generates a pair of two hypothetical smartphones with the aforementioned attributes whose levels are randomly assigned. By randomizing the levels of each attribute, researchers can assess the extent and the degree to which each attribute matters to the respondents. Most importantly, the respondents evaluate and choose an option as a package of different attributes, which closely reflects real-world multidimensional choice situations. In addition, this approach can reduce social desirability bias of the respondents because multiple attributes allow them to justify the reason for a particular choice and their rating (Wallander, 2009).

This empirical approach is applicable to the present problem regarding popular understandings of democracy. Indeed, conjoint analysis can better address the multidimensional nature of understandings of democracy. Moreover, it allows us to measure which attributes or properties the respondents give more emphasis. For example, Graham and Svolik (2020) find that, when choosing a candidate during the elections, partisan interests and considerations with respect to economic and social policies work as the strongest drivers of vote choice, which obscures undemocratic attitude and behavior of candidates. In what follows, I apply conjoint analysis to demonstrate what we can learn about popular understandings of democracy. By doing so, I attempt to provide an opportunity to investigate whether conjoint analysis helps improve the measurement of people's understandings of democracy.

To investigate the extent to which citizens living in a democratic country hold different views of democracy, I conducted a conjoint analysis in which the respondents in an online survey evaluated two hypothetical countries with a set of attributes that represent different perspectives of democracy. In this paper, I focus on three dimensions of democracy. First, the attributes of electoral competition and electoral participation relate to the procedural view of democracy (e.g., Dahl, 1971). Second, as a dimension distinct from the procedural view of democracy, I include three attributes that represent checks and balances—media, separation of powers, and minority protection. Claassen (2020) argues, for instance, that democracy involves majoritarian and counter-majoritarian (or minoritarian) elements. Majoritarian elements of democracy closely relate to electoral institutions and processes while minoritarian elements are represented by institutions and processes that embody liberal views and protect minorities in general. Lastly, the attributes of economic growth and social welfare constitute the substantive view of democracy, which emphasizes the outcomes produced by political regimes. I chose the three dimensions to closely reflect on the ongoing debate of substantive democracy versus procedural democracy. I added the minoritarian aspect because this plays a role different from the majoritarian aspect with respect to support for democracy (Claassen, 2020).6

In this study, I chose a sample from Japanese adult population. First, Japan is an old democracy that experienced democratic transition after the Second World War (Huntington, 1991). This means that most of the respondents in this survey were born after Japan became a democracy in the procedural minimalist sense. Therefore, population homogeneity regarding democratic experience would be presumably high.7 As Figure 2 indicates, Japanese people are divided into procedural and substantive understandings of democracy, despite a long and stable democratic history. Thus, it is intriguing to see the extent to which people in Japan view democracy in a procedural or substantive manner and which attributes constitute democratic understandings among them. Second, to ensure representativeness of the respondents through web survey, it is critical that the target country achieves a high internet penetration rate. According to the Internet World Stats (2019), the internet penetration rates of Japan is 93.5% as of 2019. In addition, Japan is ranked twenty-fifth in the world and seventh in Asia after Kuwait (99.6%), Qatar (99.6%), Bahrain (99.3%), UAE (98.5%), South Korea (95.9%), and Brunei Darussulam (94.9%).8 Thus, Japan is well suited for an online survey as the sampling bias due to the lack of internet access is likely to be small.9

Table 2 presents the seven attributes with varying levels that are used in the conjoint analysis. The attribute of electoral competition includes free and fair elections, cases of election fraud that are severely punished if detected, a single party dominance with alleged electoral fraud, and holding unfree and unfair elections. The attribute of electoral participation includes universal suffrage, universal suffrage with complicated registration procedure, and cases in which suffrage is not granted to certain ethnic minorities. The attribute of media includes three levels—neutral media, media that are critical of the government, and the government pressurizing the media so that criticism is not expressed. The attribute of separation of powers includes divided government and resulting policy stalemate, the Supreme Court overruling government decisions, excessive use of presidential decree in policy-making, and bureaucracy making most policy decisions. The attribute of minority protection includes cases in which a country attempts to integrate immigrants, properly represents sexual minorities, disregards ethnic minorities, or does not recognize certain religions. The first attribute of the substantive view refers to economic growth. This ranges from a growth rate of 5%, 1%, −1%, to −5%, which correlates with the extent to which the citizens benefit or suffer from economic performance. The second is about social welfare. This includes two contrasting cases with respect to social security system and resulting provision of, for instance, education and health. Another set of two contrasting cases is about the government measure to fight a high unemployment rate.

A survey was conducted online with a sample of Japanese adults. The sample was recruited to represent the Japanese adult population. Rakuten Insight fielded the survey in January 2022 and 2,206 respondents participated in the study. This sample excludes those who failed to carefully read the survey instructions or failed to answer an attention check question in the middle of the survey. The survey started with a set of questions asking respondents' nationality, age, gender, and political attitude, behavior, and knowledge, which was followed by conjoint tasks. The survey concluded with a battery of demographic questions regarding respondents' household, marital status, prefecture of residence, education level, employment, and household income.10

In the survey, the respondents were presented with a pair of hypothetical countries with the seven attributes whose levels were randomly assigned. They were asked to choose which country looks more democratic. Table 3 shows an example conjoint task.11 After comparing the two hypothetical countries, the respondents were asked to choose from “Country A is more democratic” and “Country B is more democratic”. Each respondent was asked to complete the task five times. To avoid the order effect of attributes on respondents' answer, the order of attributes was randomly assigned. The order was, however, fixed to one respondent to avoid imposing excessive cognitive burdens on the respondents.12

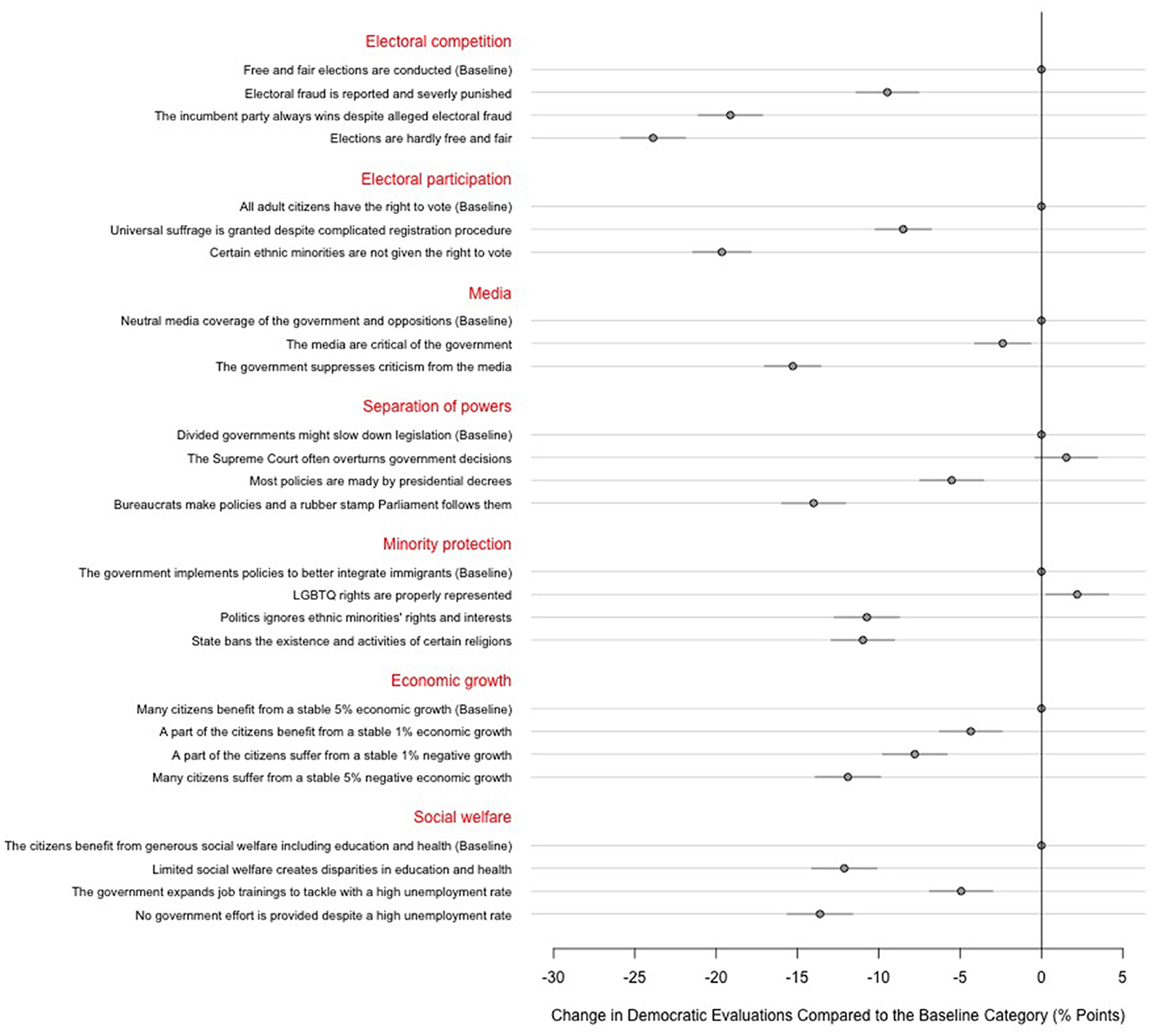

Figure 3 presents the estimated average marginal component effect (AMCE) of a regime attribute on a respondent's probability of choosing a hypothetical country as being more democratic than the other hypothetical country. The horizontal bars represent 95% confidence intervals that are robust to clustering at the respondent level. One of the levels in each attribute is set as the baseline and the AMCEs represent the extent to which the other levels affect the respondents' evaluation relative to the baseline. Note that we can compare the magnitude of AMCEs across properties.

Figure 3. The average effects of regime characteristics on respondents' evaluation of a country's democracy. Each solid circle represents the estimated average marginal component effect (AMCE) of a regime attribute on a respondent's probability of choosing a hypothetical country as being more democratic than the other country. The horizontal bars represent 95% confidence intervals that are robust to clustering at the respondent level.

First, a country in which elections are held, but are hardly free and fair, witnesses 23.9% decrease in the probability of being chosen as more democratic than another country with free and fair elections. This negative effect of unfree and unfair elections is strongest among all property levels, implying that Japanese people believe, on average, that rigged and stolen elections render a political regime least democratic. The second largest negative effect is found in cases where the incumbent always wins the elections despite alleged fraud (−19.1%) and when certain ethnic minorities are not granted the right to vote (−19.7%). In brief, the analysis reveals that Japanese respondents, on average, strongly react to undemocratic characteristics of electoral competition and participation.

Second, the AMCEs are found negative and moderately strong in size when the media are unable to criticize the government (−15.3%), bureaucrats make policies which are followed by a rubber stamp legislative institution (−14.0%), the government makes no effort at fighting a high unemployment rate (−13.6%), disparities exist in education and health provision (−12.1%), many citizens suffer from a −5% economic growth (−12.0%), the state denies certain religions (−11.0%), and ethnic minorities are ignored in politics (−10.7%). Hence, we can observe that the respondents consider those negative characteristics with respect to the minoritarian view and substantive view of democracy.

In brief, the present analysis demonstrates the multidimensional nature of popular understandings of democracy by conducting conjoint analysis and offering a comprehensive picture of subjective understandings of democracy. We observe that Japanese people, on average, consider a regime least democratic if electoral competition and participation are severely undermined and constrained. In addition, we learn that the properties representing the minoritarian view and the substantive view of democracy play an undeniable role when the citizens evaluate a country's democracy level. Media freedom, separation of powers, and minority protection, economic growth, and social welfare are important for the citizens, to a certain and moderate degree when comparing countries' democracy. Even in a country like Japan in which democracy has been present for more than seventy years, individuals incorporate regime outputs, particularly economic performance and security, into their evaluation of democracy. The finding corroborates the results of the Asian Barometer Survey Wave 4 (Figure 2). However, the present analysis reveals that procedural democracy is more important than the other perspectives.

Global support for democracy is puzzling in the face of alleged backlash toward democracy. What does democracy mean for the public when they express support for it? Put differently, when they think about democracy, which aspect of democracy do they emphasize or prioritize? The conjoint analysis with a sample of Japanese adults demonstrates that, on the one hand, a lack of free and fair elections and disenfranchisement of certain groups in the society, which represents the procedural view of democracy, is considered to undermine democracy the most. That is, democratic procedures and institutions are at the core of their perception of democracy. On the other hand, however, the findings indicate that they also take into consideration other aspects of democracy which the minoritarian view and the substantive view of democracy embody. Therefore, the results corroborate the idea that popular understandings of democracy are heterogeneous.

The findings are distinct from the previous studies because the conjoint analysis incorporates the trade-offs that individuals might encounter when evaluating democracy. The analysis shows that, among Japanese people, electoral competition and participation are most important when evaluating a country's democracy level. Future research on popular understandings of democracy would improve by incorporating the extent to which individuals prioritize certain properties of democracy they identify into the measurement of understandings of democracy. As this paper demonstrates, conjoint analysis could be a useful tool for that purpose. A natural next step would be to examine when and why individual citizens hold the procedural minimalist view of democracy rather than the substantive view of democracy while using the findings from conjoint analyses. The literature developed a number of hypotheses including, for example, the lifelong learning of democracy (e.g., Bratton et al., 2005; Mattes and Bratton, 2007; Fails and Pierce, 2010) and the role that emancipative values play in shaping the popular understanding of democracy (e.g., Welzel, 2013). In addition, it is intriguing is to apply conjoint analysis to examine attributes of democracy that are not a part of procedural, minoritarian, or substantive democracy (e.g., Norris, 2011; Kirsch and Welzel, 2019).

Despite the advantages of conjoint analysis, there are certainly caveats. First, conjoint analysis is easy to implement for online surveys as we can automatically randomize the attribute levels, which, in turn, brings all the issues inherent in web surveys (Tourangeau et al., 2013). Among many others, some might have concerns about the nature of the samples because we often rely on a pool of respondents that a survey firm has recruited or those who spontaneously register for a survey pool membership. Because the participation in online surveys presumes literacy, conjoint analysis embedded in web surveys might not reach illiterate citizens and voters that face-to-face surveys could interview with, which might cause a bias in the sample. Second, if hypothetical options are unrealistic because of the randomly assigned attribute levels, the conclusions drawn from conjoint analyses might not be generalizable, which would lead to a low external validity of the experiment. In the present study, it would be unrealistic to insert a country name as an attribute because the hypothetical options might include, for instance, a case in which a country name is France and the attribute is unfree and unfair elections. From the respondents' perspective, this does not seem an appropriate hypothetical case, potentially causing measurement errors. This implies limitations in the design of conjoint analysis that might not happen with other types of survey. Future research would benefit from constructing conjoint designs to minimize the external validity issues while maximizing the benefits out of this empirical strategy.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, the University of Tsukuba. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Kakenhi Grant Numbers 20H00061 and 20K13392.

KS thank Hao-Jung Hsieh, Jae-Hee Jung, Roni Lehrer, and Wen-Chin Wu for their comments to an early version of this paper. The Asian Barometer Survey data analyzed in this article were collected by the Asian Barometer Project (2013–2016), which was co-directed by Professors Fu Hu and Yun-han Chu and received major funding support from Taiwan's Ministry of Education, Academia Sinica, and National Taiwan University. The Asian Barometer Project Office (www.asianbarometer.org) is solely responsible for the data distribution. The author appreciates the assistance in providing data by the institutes and individuals aforementioned.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2023.976756/full#supplementary-material

1. ^It is important to note that employing the procedural minimal definition of democracy in empirical research does not necessarily mean that this must be the definition of democracy. For the criticism that the literature on democratic transition (or transitology) is teleological and a counterargument to it, see Gans-Morse (2004).

2. ^As Dahl (1971, p. 10–11) acknowledges, the procedural minimal definition of democracy is not concerned with the further democratization of democracies (or polyarchies). Thus, it is not surprising that ordinary citizens consider democracy beyond the two dimensions—public contestation and participation—that constitute the minimalist definition.

3. ^Osterberg-Kaufmann et al. (2020) argue that this approach in fact reveals knowledge of democracy among individuals as it does not require any reference or base concept of democracy to begin with. Importantly, there are more methodological approaches other than open-ended questions in public opinion poll to study citizens' knowledge of democracy. See Osterberg-Kaufmann et al. (2020) for an overview of alternative approaches.

4. ^Another issue in this approach taken by the WVS is that “each characteristic is presupposed to be essential to a greater or lesser degree. Hence, this type of question does not permit the respondents themselves to determine whether some of the proposed characteristics are incompatible with democracy. Even the response ‘not an essential characteristic of democracy' cannot be treated unequivocally. It can be used by respondents to mark unessential characteristics or characteristics which are incompatible with democracy” (Zagrebina, 2020, p. 7).

5. ^The Supplementary material shows the results of each survey item separately.

6. ^In past survey research, other elements of political regime were investigated regarding understandings of democracy such as the role of religious authority, military, and strong leader in politics (e.g., the World Values Survey). Thus, future research would benefit by examining them through conjoint analysis.

7. ^It is important to note that Japan is known for the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) that governs as the dominant party. The LDP has lost elections for the lower house only twice (1993 and 2009) since democratic transition. Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility of generational gaps before and after the first alternation in power in 1993, for instance.

8. ^If we exclude countries with a high internet penetration rate in the Middle East, Japan is ranked third in Asia.

9. ^The high internet penetration rate does not necessarily guarantee, for instance, that the older generations are equally likely to participate in online surveys as the younger generations. However, in an online that I conducted in Japan and Taiwan in November 2022, there was a clear difference and I could reach higher number of older population in Japan than in Taiwan.

10. ^The Supplementary material presents the distribution of respondents' gender, age group, prefecture of residence, and annual household income.

11. ^Because the level of each attribute was randomly assigned, it is possible that a pair of hypothetical countries have the same level in an attribute (which is indeed the case for the “economic growth” attribute in Table 3).

12. ^Some might wonder whether the present conjoint design imposes extensive cognitive burdens on the respondents because the profile of the hypothetical countries involves more information than the other applications. I am not aware of previous studies that systematically address this point, and therefore unable to investigate whether the current design generates biased conclusion. This is an important question for future research, but remains beyond the scope of this study. To address this concern, I decided to ask the respondents to perform five tasks. Bansak et al. (2018) argue that assigning dozens of tasks does not lead to substantial declines in response quality when a conjoint design remains relatively simple.

Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., and Yamamoto, T. (2018). The number of choice tasks and survey satisfiing in conjoint experiments. Politic. Anal. 26, 112–119. doi: 10.1017/pan.2017.40

Baviskar, S., and Malone, M. F. T. (2004). What democracy means to citizens—and why it matters. Eur. Rev. Latin Am. Caribb. Stud. 76, 3–23. doi: 10.18352/erlacs.9682

Blokker, P. (2012). Multiple Democracies in Europe: Political Culture in New Member States. New York, NY: Routledge.

Boix, C. (2003). Democracy and Redistribution. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511804960

Booth, J., and Richard, P. (2014). Latin American Political Culture: Public Opinion and Democracy. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Bratton, M., Mattes, R., and Gyimah-Boadi, E. (2005). Public Opinion, Democracy, and Market Reform in Africa. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511617324

Camp, R. A. (2001). Citizen Views of Democracy in Latin America. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt5hjp4v

Canache, D. (2012). Citizens' conceptualizations of democracy: structural complexity, substantive content, and political significance. Comp. Polit. Stud. 45, 1132–1158. doi: 10.1177/0010414011434009

Cho, Y. (2015). How well are global citizenries informed about democracy? ascertaining the breadth and distribution of their democratic enlightenment and its sources. Polit. Stud. 63, 240-258. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12088

Chu, Y.-h., Diamond, L., Nathan, A., and Shin, D. C. (2008). How East Asians View Democracy. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. doi: 10.7312/chu-14534

Claassen, C. (2020). In the mood for democracy? democratic support as thermostatic opinion. Am. Politic. Sci. Rev. 114, 36–53. doi: 10.1017/S0003055419000558

Collier, D., Hidalgo, F. D., and Maciuceanu, A. O. (2006). Essentially contested concepts: Debates and applications. J. Politic. Ideol. 11, 211–246. doi: 10.1080/13569310600923782

Collier, D., and Levitsky, S. (1997). Democracy with adjectives: conceptual innovation in comparative research. World Politics 49, 430–451. doi: 10.1353/wp.1997.0009

Coppedge, M., Alvarez, A., and Maldonado, C. (2008). Two persistent dimensions of democracy: contestation and inclusiveness. J. Polit. 70, 632–647. doi: 10.1017/S0022381608080663

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Alizada, N., et al. (2021). V-Dem Country-Year/Country-Date Dataset v11.

Crow, D. (2010). The party's over: citizen conceptions of democracy and political dissatisfaction in Mexico. Comp. Polit. 43, 41–61. doi: 10.5129/001041510X12911363510358

Dalton, R. J., Jou, W., and Shin, D. C. (2007). Understanding democracy: data from unlikely places. J. Democr. 18, 142–156. Available online at: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/223229

Davidov, E., Meuleman, B., Cieciuch, J., Schmidt, P., and Billiet, J. (2014). Measurement equivalence in cross-national research. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 40, 55–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043137

Diamond, L. (2008). The Spirit of Democracy: The Struggle to Build Free Societies. New York, NY: Times Book.

Diamond, L. (2011). The impact of the economic crisis: why democracies survive. J. Democ. 22, 17–30. Available online at: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/412890

Elkink, J. A. (2011). The international diffusion of democracy. Comp. Politic. Stud. 44, 1651–1674. doi: 10.1177/0010414011407474

Fails, M. D., and Pierce, H. N. (2010). Changing mass attitudes and democratic deepening. Politic. Res. Q. 63, 174–187. doi: 10.1177/1065912908327603

Ferrín, M., and Kriesi, H. (2016). How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gallie, W. B. (1955). Essentially contested concepts. Proc. Aristotelian Soc. 56, 167–198. doi: 10.1093/aristotelian/56.1.167

Gans-Morse, J. (2004). Searching for transitologists: contemporary theories of post-communist transitions and the myth of a dominant paradigm. Post-Soviet Affairs 20, 320–349. doi: 10.2747/1060-586X.20.4.320

Graham, M. H., and Svolik, M. W. (2020). Democracy in America? Partisanship, polarization, and the robustness of support for democracy in the United States. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 114, 392–409. doi: 10.1017/S0003055420000052

Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., et al. (2020). World Values Survey: Round Seven—Country-Pooled Datafile.

Haggard, S., and Kaufman, R. (2021). Backsliding: Democratic Regress in the Contemporary World. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108957809

Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., and Yamamoto, T. (2014). Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Politic. Anal. 22, 1–30. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpt024

Hopkins, D. J., and King, G. (2010). Improving anchoring vignettes: designing surveys to correct interpersonal incomparability. Public Opin. Q. 74, 201–222. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfq011

Huang, M.-H. (2018). "Cognitive involvement and democratic understanding," in Routledge Handbook of Democratization in East Asia, eds. T.-j. Cheng and Y.-h. Chu (London: Routledge), 297–313. doi: 10.4324/9781315733869-18

Huntington, S. P. (1991). The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press.

Inglehart, R. (2003). How solid is mass support for democracy and how can we measure it? Polit. Sci. Polit. 36, 51–57. doi: 10.1017/S1049096503001689

Internet World Stats (2019). Top 25 Countries With the Highest Internet Penetration Rates (Users Divided By Population).

Jamal, A., and Tessler, M. (2008). Attitudes in the Arab world. J. Democracy 19, 97–110. doi: 10.1353/jod.2008.0004

Kirsch, H., and Welzel, C. (2019). Democracy misunderstood: authoritarian notions of democracy around the globe. Social Forces 98, 59–92. doi: 10.1093/sf/soy114

Klingemann, H.-D., Fuchs, D., and Zielonka, J. (Eds.). (2008). Democracy and Political Culture in Eastern Europe. New York, NY: Routledge. Available online at: https://www.routledge.com/Democracy-and-Political-Culture-in-Eastern-Europe/Klingemann-Fuchs-Zielonka/p/book/9780415479622

Maseland, R., and van Hoorn, A. (2011). Why muslims like democracy yet have so little of it. Public Choice 147, 481–496. doi: 10.1007/s11127-010-9642-5

Mattes, R., and Bratton, M. (2007). Learning about democracy in Africa: awareness, performance, and experience. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 192–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00245.x

Miller, A. H., Hesli, V., and Reisinger, W. M. (1997). Conceptions of democracy among mass and elite in post-soviet societies. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 27, 157–190. doi: 10.1017/S0007123497000100

Mishler, W., and Rose, R. (2002). Learning and re-learning regime support: the dynamics of post-communist regimes. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 41, 5–36. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00002

Munck, G. L., and Verkuilen, J. (2002). Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: evaluating alternative indices. Comp. Polit. Stud. 35, 5–34. doi: 10.1177/001041400203500101

Norris, P. (2011). Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511973383

Osterberg-Kaufmann, N., Stark, T., and Mohamad-Klotzbach, C. (2020). Challenges in conceptualizing and measuring meanings and understandings of democracy. Z. Vergleich. Politikwissensch. 14, 299–320. doi: 10.1007/s12286-020-00470-5

Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M. E., Cheibub, J. A., and Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950–1990. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511804946

Rose, R., Mishler, W., and Haerpfer, C. W. (1998). Democracy and Its Alternatives. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Schedler, A., and Sarsfield, R. (2007). Democrats with adjectives: linking direct and indirect measures of democratic support. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 46, 637–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2007.00708.x

Shi, T. (2014). The Cultural Logic of Politics in Mainland China and Taiwan. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511996474

Shi, T., and Lu, J. (2010). The shadow of confucianism. J. Democr. 21, 123–130. doi: 10.1353/jod.2010.0012

Shin, D. C., and Kim, H. J. (2018). How global citizenries think about democracy: an evaluation and synthesis of recent public opinion research. Jpn J. Polit. Sci. 19, 222–249. doi: 10.1017/S1468109918000063

Shin, D. C., and Tusalem, R. F. (2007). The cultural and institutional dynamics of global democratization: a synthesis of mass experience and congruence theory. Taiwan J. Democr. 3, 1–28. Available online at: http://www.tfd.org.tw/opencms/english/publication/journal/data/Journal0005.html

Svolik, M. (2008). Authoritarian reversals and democratic consolidation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 102, 153–168. doi: 10.1017/S0003055408080143

Svolik, M. W. (2015). Which democracies will last? Coups, incumbent takeovers, and the dynamic of democratic consolidation. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 45, 715–738. doi: 10.1017/S0007123413000550

Tourangeau, R., Conrad, F. G., and Couper, M. P. (2013). The Science of Web Surveys. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199747047.001.0001

Ulbricht, T. (2018). Perceptions and conceptions of democracy: applying thick concepts of democracy to reassess desires for democracy. Comp. Polit. Stud. 51, 1387–1440. doi: 10.1177/0010414018758751

Wallander, L. (2009). 25 years of factorial surveys in sociology: a review. Soc. Sci. Res. 38, 505–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.03.004

Wegscheider, C., and Stark, T. (2020). What drives citizens' evaluation of democratic performance? The interaction of citizens' democratic knowledge and institutional level of democracy. Z. Vergleich. Politikwissensch. 14, 345–374. doi: 10.1007/s12286-020-00467-0

Welzel, C. (2013). Freedom Rising. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139540919

Welzel, C., and Alvarez, A. M. (2014). “Enlightening people: the spark of emancipative values,” in The Civic Culture Transformed: From Allegiant to Assertive Citizens, eds. R. Dalton and J. Welzel (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 59–88. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139600002.007

Keywords: understanding of democracy, support for democracy, democratic backsliding, conjoint analysis, Japan

Citation: Seki K (2023) Assessing the public understanding of democracy through conjoint analysis. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:976756. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.976756

Received: 23 June 2022; Accepted: 05 January 2023;

Published: 27 January 2023.

Edited by:

Régis Dandoy, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, EcuadorReviewed by:

Marlene Mauk, GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, GermanyCopyright © 2023 Seki. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katsunori Seki, c2VraS5rYXRzdW5vcmkuZnVAdS50c3VrdWJhLmFjLmpw

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.