- Institute for Global Health and Development, Queen Margaret University, Musselburgh, United Kingdom

This paper highlights the importance of local and individual context in either facilitating or hindering processes of integration for reunited refugee families settling in unchosen areas. It adds to understandings of integration by analyzing the day-to-day active and processual nature of place-making, from the perspective of families. The findings are based on qualitative interviews with 13 refugee families−21 parents and 8 children aged between 12 and 18, who had recently been reunited in two large cities in the UK: Glasgow and Birmingham. The paper explores the local conditions families identified as conducive to settling in their local area and argues that the process of attaching to their new locales was mediated through the social connections they made. The article contributes to knowledge by demonstrating how families exercised agency and resilience in place-making in unchosen spaces, through the people they met and the relationships they developed. Further, it critiques the tendency to denigrate “exclusive” bonding ties, particularly between co-ethnics and pays attention to the role of friendship in routes to belonging in unchosen spaces.

1 Introduction

This article builds on definitions of integration as a multi-directional, multi-dimensional and relational process with social connections at its heart (Ager and Strang, 2004; Ndofor-Tah et al., 2019) and as a dynamic process which incorporates economic, social and spatial dimensions (Kearns and Whitley, 2015; Spencer and Charsley, 2021). It argues that place and identities are co-constituted in spaces, between people, and calls for a re-linking of the relational and affective aspects of integration to the sites where social interaction happens. Drawing on Massey (1991, 2005), the article demonstrates how refugee families negotiate the process of integration through relational place-making. It describes the routes or integration pathways which family members carve out through their everyday interactions in new and unfamiliar spaces, toward a sense of feeling at home in an area. The theory of place-making is not only relevant to the social and spatial dimensions of integration, but also to the affective side of integration; how feelings of belonging are negotiated. The article explores place-making from the perspectives of people already granted refugee status who are at a very particular transition point in their personal and familial integration pathways, having been recently reunited in the UK. Specifically, it focuses on recently reunited refugee families' daily negotiation of place-making in unchosen places. It analyses the opportunities and constraints to develop friendships, how the families exercised choice in the people and spaces they attached to, and the meanings attached to these relationships. Places are not just the sites where social relations happen, but rather identities and places are co-constructed by the people who live there, forging a sense of attachment to locales through social interactions in shared spaces. The making of place is crucial in the process of actively negotiating the spatial and social dimensions of belonging. In the words of Massey:

“[W]hat gives place its specificity is not some long internalized history but the face that is constructed out of a particular constellation of social relations, meeting and weaving together at a particular locus.” (Massey, 1991, p. 7)

The author adopts a political lens in analyzing the everyday processes of weaving together of people in spaces; recognizing that place-making happens in uneven spaces and that the opportunities to access the spaces of interaction are not equally available to all people. Amin (2002, p. 959) refers to this as the “micropolitics of everyday social contact and encounter.” Boccagni and Hondagneu-Sotelo (2023) conceptualize the dynamic and contested process of negotiating belonging in spaces as “homemaking” and argue that this constitutes a new analytical category from which to unpack and understand the contexts in which people, spaces and time intersect. Echoing Yuval-Davis (2006) they highlight the differential social locations of actors in this relational process (see also Wessendorf, 2019). However, this article retains the concept of place-making, drawing on later iterations of 'Massey's de-essentializing theory of space and place which also highlights how unequal social relations are played out in the everyday politics of place-making. She argues that power imbalances are played out relationally:

“through a myriad of practices of quotidian negotiation and contestation; practices, moreover, through which the constituent “identities” are themselves continually moulded” (Massey, 2005, p. 154)

It is the contexts in which unequal social relations are played out and the agency exercised by refugee families in negotiating belonging in new locales, despite the constraints and lack of freedoms to choose where to live and who to interact with that this article is concerned with. Following feminist scholars such as Lenette et al. (2013) and O'Reilly this article aims to pay:

“empirical attention to the everyday lives of migrants in order to understand and make visible the processes of mobility and immobility” (O'Reilly, 2018)

Further, the paper explores the affective side of integration, paying attention to the meaning attached to friendships in new locales, and how these relationships shape narratives of transnational belonging or feeling “at home”. It draws particularly on Yuval-Davis (2006) who argues for a multi-faceted analysis of the “politics of belonging” including at the level of who and what people identify with, and the emotional attachments they make. Rather than making assumptions about the form, function and meaning (Baillot et al., 2023) of friendships made in the UK, particularly on the basis of nationality and ethnicity, the author argues that, the basis for homophilus “identifications” (Yuval-Davis, 2006) cannot be assumed but are rather “an observation that had to be explained” (Barwick, 2017). In conceptualizing belonging as the affective side of integration the article seeks to explore: who people interact with; in what spaces; and how they negotiate their relationship, based on which common and distinct aspects of their identities. Ultimately, we need to understand the meanings people attach to relationships vis-à-vis their feelings of belonging to particular physical and social locales.

For refugees, the practice of transnational place-making, place-attachment or “emplacement” (Schiller and Çaglar, 2013; Nelson et al., 2019; Wessendorf and Phillimore, 2019) must be understood in the context of displacement; a liminal state of “being attached to several places while simultaneously struggling to establish the right to a place” (Brun, 2015). People granted refugee status have been forced to migrate from their home countries and are then doubly displaced in the UK through the dispersal system and, later through a series of moves between emergency and temporary housing arrangements until they are able to secure permanent housing.

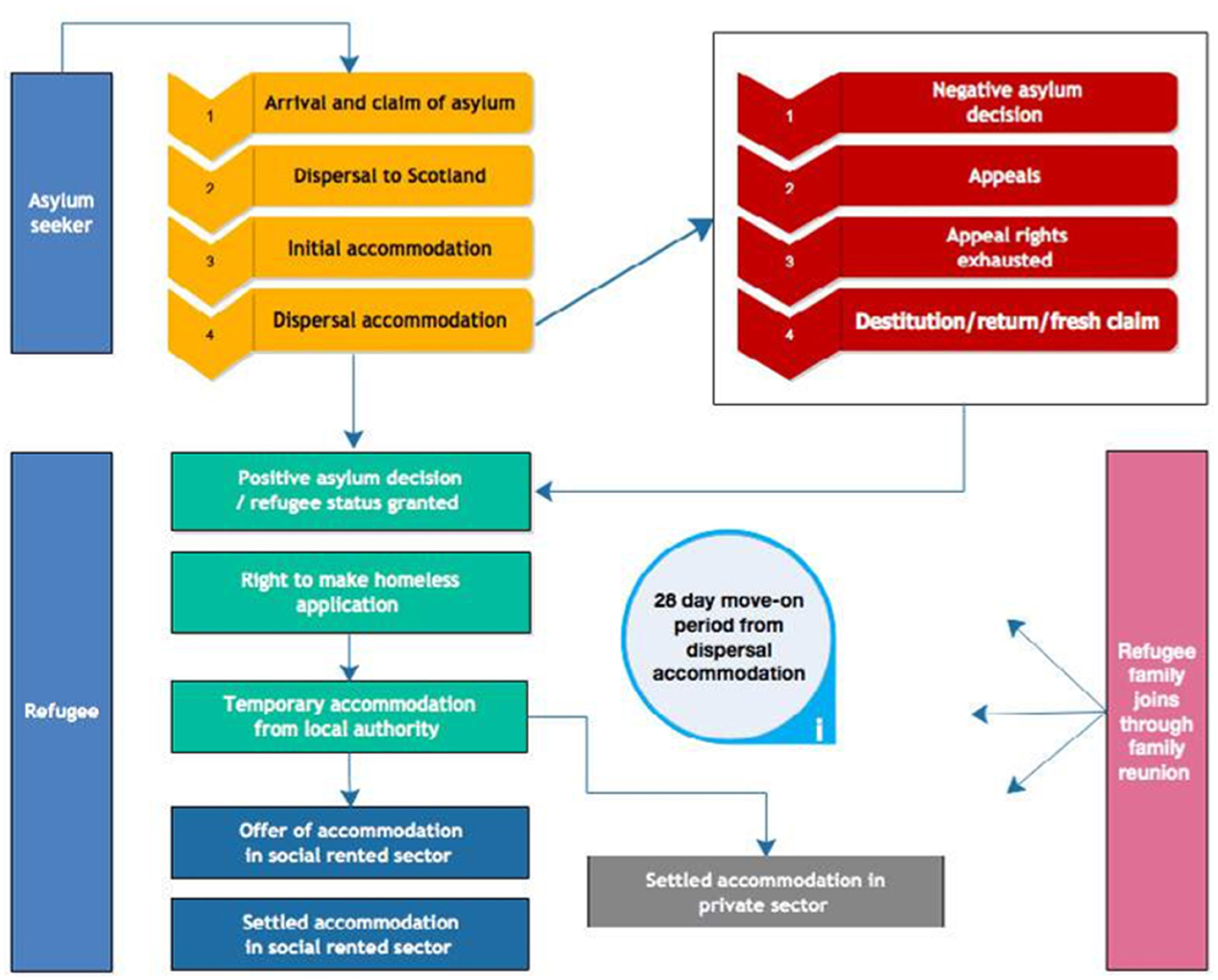

Lack of choice over where to live, homelessness and poverty are built into the UK housing and welfare systems asylum seekers and refugees have to navigate at several transition points in their integration pathway (Mcphail, 2021). First, at the point of claiming asylum, when people are dispersed on a no-choice basis from London and the Southeast of England according to the national dispersal policy, introduced under the 1999 Immigration and Asylum Act. Originally entered into by voluntary agreement with participating Local Authorities in England, Scotland and Wales, the dispersal scheme recently became mandatory and was widened to include all Local Authorities (Home Office, 2022). Updated Home Office guidance on accommodation allocation emphasizes the overarching principle is to allocate housing on a “no-choice basis”. It states that any consideration of location requests to be housed near to friends, family or children's schools should not “outweigh the public interest of allocating accommodation on a “no-choice basis” outside London and the Southeast and in areas of the UK where the Home Office has a ready supply” (Home Office, 2022, p. 9). Asylum seekers are often housed in areas with poor quality housing stock, limited services and social infrastructure, and far from existing support networks (Kerlaff and Käkelä, forthcoming; Hill et al., 2021).

The second key transition point in the housing journey comes once a person is granted refugee status and is subsequently served “notice to quit” their current asylum accommodation within a 28-day “move-on period” during which they are expected to secure follow-on accommodation, usually in the social or private rental sector. While, in theory, recognized refugees have freedom to choose where they live, the reality is that few have the resources to afford them this luxury and will at this point have little choice but to register as homeless. Most asylum seekers are not allowed to work and are therefore reliant on asylum support, currently £47.30 per person per week, barely enough to live on, let alone enough to allow them to save money. Further, there is substantial evidence that the 28 day move-on period gives insufficient time to secure onward accommodation or access welfare benefits, putting newly granted refugees at risk of homelessness and destitution (Provan, 2020). Despite this, the UK government have just announced plans to reduce this “move-on period” to just 7 days (The Guardian, 2023).

The third transition point for reunited refugee families comes at the point of arrival of the family joining the sponsor in the UK when larger accommodation will usually be required. Most local authority areas, Birmingham being one of them, only activate their homelessness prevention duties once the family have arrived in the UK and won't accept an application for homelessness accommodation from the sponsor prior to his or her family's arrival (British Red Cross, 2022a). Glasgow, in contrast, will accept a claim a few days before the family arrives. Further, reunited families face a “destitution gap” in the intervening period between the sponsor's individual Universal Credit claim being canceled, and a new joint claim being processed (British Red Cross, 2022a).

The process for seeking accommodation in the UK for those who have come through the asylum route is depicted in Figure 1 (reproduced from Mcphail, 2021, p. 10). It should be noted that this figure does not reflect changes to this process which are currently being implemented under the UK Nationality and Borders Act 2022 and the Illegal Migration Act 2023. The initial lack of choice over where to live, and imposed financial insecurity as an asylum seeker, have a ripple effect on the housing allocation process after being granted refugee status, and again when family join sponsors in the UK and larger accommodation is required. Further, many families face overcrowding when they are reunited when the transition to more suitable accommodation can take many months after the family's arrival.

Figure 1. The housing process for people claiming asylum in the UK, reproduced with permission from Mcphail (2021, p. 10).

Homelessness is embedded in the system refugees have to navigate and multiple moves cause further disruptions and ruptures in the integration process (Hynes, 2011; Meer et al., 2019). Multiple moves between emergency and temporary accommodation can undermine the family's efforts to progress their integration pathways in other areas such as children's education and building social networks.

This cycle of exclusion requires refugees to constantly negotiate a sense of security and belonging in the face of ongoing rupture, liminality (O'Reilly, 2018; Vidal et al., 2023), stasis and insecurity (Brun, 2015; Horst and Grabska, 2015). This paper looks at the “opportunity structures” (Phillimore, 2021) that restrict refugee families' choice in where to make their new homes in the UK, and the resultant impact on their integration journeys. It explores how the families we interviewed exercised agency and resilience in negotiating a sense of place and belonging in the cities they were housed in, despite both the structural constraints on their integration pathways, and the additional ruptures imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

2 Materials and methods

This article is based on findings from a mixed methods study conducted from 2019 to 2020 with people who were accessing a family reunion integration service provided by two third sector organizations. The service provided support both to the sponsor refugee—the first parent to arrive, usually alone, and to their arriving spouse and any dependent children. The terms sponsor, spouse and child are used throughout the remainder of the article to differentiate participants and family pseudonyms are used throughout. The service was explicitly designed to deliver interventions across the domains of the Indicators of Integration framework (Ndofor-Tah et al., 2019). This included work to support families to re-build bonds between them, and to foster bridging connections with local communities (Baillot et al., 2020).

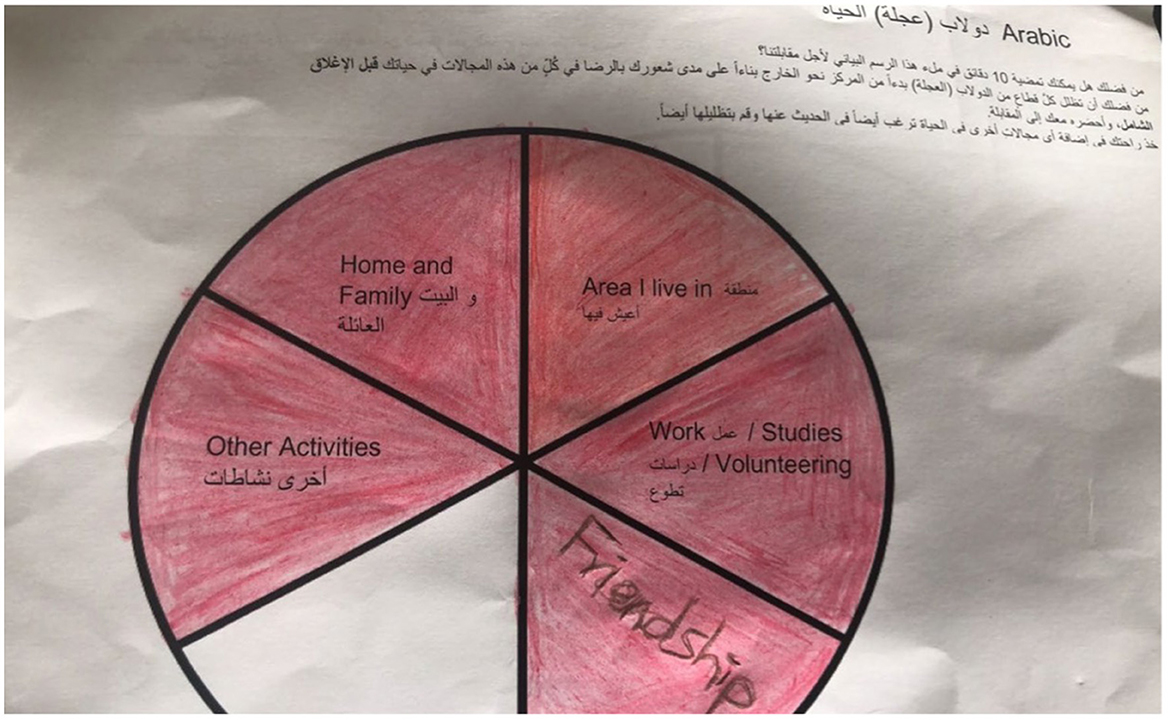

It draws on data from semi-structured interviews with 13 families, including 21 parents and 8 children aged between 12 and 18, all of whom had recently been reunited in two large cities in the UK: Glasgow and Birmingham. These locations were selected in agreement with practice partners as the families in these sites were being supported by family project workers to whom interviewers could pass on any concerns for safety and wellbeing. None were recorded. The interviews were conducted remotely over Zoom or by telephone during July and August 2020 due to strict physical distancing restrictions imposed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Professional interpreters were used when requested. A schedule was used to guide the interviews and accompanied by an adapted coaching tool “the Wheel of Life” which was used to offer greater control to participants in guiding the conversation to the areas of their lives they wanted to speak about, and as a visual tool to facilitate the conversation. Different wheels were adapted for children and adults, to reflect the different priority areas of their lives. Interviewees were posted the visual tools in advance of the interview, with a set of coloring pencils, translated information about the interviews, and instructions on how to complete the wheels. They were asked to fill the wheels in according to how fulfilled they felt in each area of their lives, and to add any areas of life that they felt were missing from them. A filled in wheel is shown in Figure 2.

Some spouses were interviewed together and others consecutively, depending on preference and practicalities. The research team had originally anticipated interviewing family members individually, but seven out of 11 couples opted to be interviewed together. This, alongside the fact that physical distancing measures were in place and most family members were all in the house at the time of interview, could potentially have limited the opportunity for individual family members to speak completely openly. Informed consent was explained verbally before the activity and translated information sheets, including a child-friendly version were provided. Verbal consent was obtained at the outset. Ethical approval was granted by the Queen Margaret University Ethics Committee (REP 0222).

2.1 Analysis

An interpretive phenomenological approach (Matua and Van Der Wal, 2015; Noon, 2018) was used to inform both the collection and analysis of interview data; prioritizing understanding how each individual and family unit made meaning of their own experiences of settling in the UK from an emic perspective. The interviewing approach and use of the visual tool prioritized “deep listening” (Laryea, 2016) which goes beyond “active” listening in explicitly checking with interviewees that our interpretation of what they were telling us reflected their intended meaning, whilst in dialogue with them. In this way, we attempted to move beyond relying on a “flat” reading of the subsequent transcript as the principal means of interpretation. All transcripts or notes relating to each family were analyzed in turn, firstly by each individual researcher and then jointly with the two other fieldwork researchers and the Principal Investigator. In this way, data gathered from each family was reviewed as a distinct phenomenon or case. After this initial analysis the team proceeded to a more traditional inductive coding phase. Each researcher manually coded an agreed sample of interview notes and transcripts. The team then met to compare their coding schemes before proceeding to a second manual coding phase using the agreed coding framework.

The sample of families were drawn from the same family support programme and were geographically spread across different postcode areas in the two cities. Analysis of interviews focused on interviewees' emic perceptions of the home and area they were living in (at neighborhood and city level), without exploring the characteristics of the specific neighborhoods from an etic perspective. This was for both practical and conceptual reasons; it was not practical to explore the particular context of each postcode area where they lived and was also deliberately not our intention to make assumptions about the areas based on “some long internalized history” (Massey, 1991, p. 7), but rather to understand how interviewees themselves perceived the character of the areas they were living.

3 Results

3.1 Context–time, place, and person

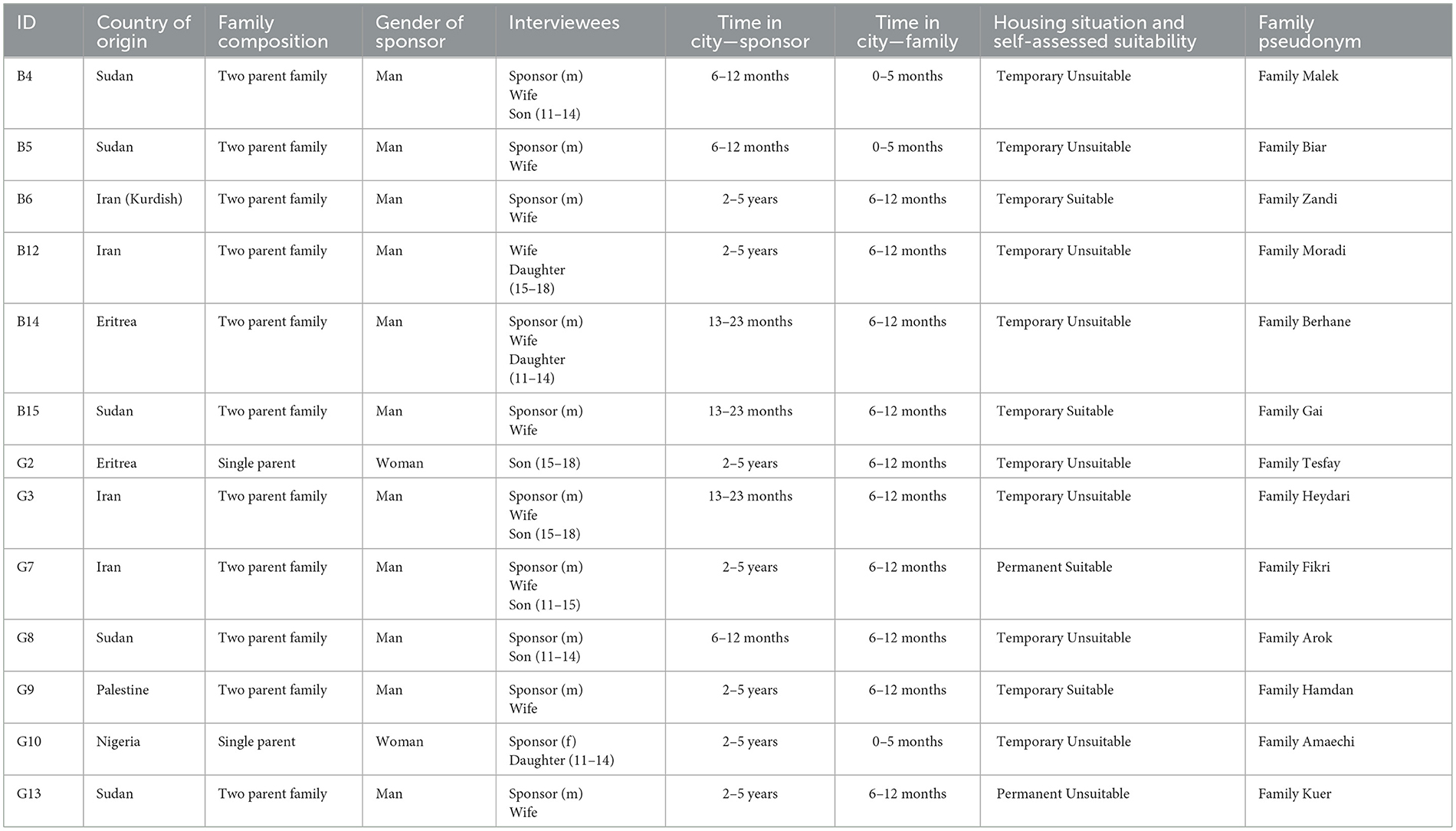

This section first contextualizes the social and physical locations of the people we spoke to, describing their position in the family, how they came to be living in Birmingham or Glasgow, and for how long they had lived there. Seven of the families we interviewed were living in Glasgow, while six were based in Birmingham (see Table 1). Sponsors had been living in the UK from anywhere between 1 and 10 years at the time of interview and had lived in Birmingham or Glasgow for anywhere between 6 months and 5 years as reflected in Table 1. The table reflects the time sponsors had lived in Glasgow or Birmingham, rather than their overall time living in the UK in line with the article's primary focus on the process of place-making at the level of the neighborhood and city.

Six people had lived exclusively in Glasgow or Birmingham, five having been directly dispersed to the cities following their arrival in the UK. Five male sponsors had chosen to live in either Glasgow or Birmingham: two had chosen to move to Birmingham, and one to Glasgow after they were granted refugee status. One had originally chosen to come to Glasgow to study and had subsequently sought asylum and stayed on in the city once granted refugee status. A fifth male sponsor was offered a choice by the authorities to relocate to Glasgow from London after he was granted refugee status and was homeless, staying with friends in London. It is unclear from the interview whether a sixth male sponsor was dispersed to Birmingham after 6–12 months living in Newcastle or made a choice to move there. Finally, one female sponsor had spent several years living in Manchester before being dispersed to Glasgow when she applied for asylum accommodation support.

All of the arriving spouses and children had been in the UK for a year or less and had come directly to join their sponsors living in Glasgow or Birmingham. In one case, the whole family were initially housed in a town outside of Birmingham before being moved to more central temporary accommodation.

In terms of family composition, all but two of the families interviewed were two-parent families in which the father had come to the UK in advance of his wife and children. The two families with female sponsors were both single mothers, one of whom arrived in the country prior to her 2 children, and the other of whom was in the country with two of her children, and recently reunited with her third child after being separated for nearly 10 years. Five families were originally from Sudan, four from Iran, two from Eritrea and the remaining two families were originally from Palestine and Nigeria.

To offer some comparative context of the size and demographics of the two cities: Birmingham is the second largest city in the UK and widely recognized as a “superdiverse” city “soon to become a majority minority city” (Birmingham City Council, 2023). The city has a population of over 1.1 million and the wider metropolitan area of Birmingham has a population of 3.8 million. In the 2021 Census, 48.7 % of Birmingham's population identified as having a white ethnic background, 31% as Asian and 10.9% as Black. This compares to the City of Glasgow which has a much smaller population of just over 635,000 and the wider area of Greater Glasgow and Clyde which has an overall population of slightly more than 1 million (National Records of Scotland, 2022); similar to the population of Birmingham city. An estimated 88.5% of Glasgow's population identify as having a White ethnic background and 11.5% as having a Black or Minority Ethnic (BME) background. While not as ethnically diverse as Birmingham, Glasgow's ethnic profile has changed significantly since 2001 (when the BME population was 5.5%), likely due in main part to the dispersal of thousands of asylum seekers since that time (Walsh, 2017). Glasgow is also nearly 3 times more ethnically diverse than Scotland's overall population which is currently recorded at 96.0% White and 4.0% BME (National Records of Scotland, 2022).

Only one family in the interview cohort were living in suitable, sustainable accommodation at the time of interview, and 15 children out of the 36 who were old enough to be in education were not yet formally registered in school or college—in part due to their arrival shortly before the country went into lockdown in 2019, and also due to waiting lists for schools in Birmingham.

3.2 Reunited in unchosen spaces

Regardless of whether the family came to be living in Birmingham or Glasgow as a result of the sponsor's choice or out of circumstance (due to the fact that the sponsor had been dispersed there on a no-choice basis during the asylum process), none had any significant choice in the area or accommodation in which they were housed. All of the families had accessed housing through the homelessness system which offers little to no choice in the allocation of accommodation. All but two families were living in temporary houses and flats at the time of interview and without exception, all of the families living in Birmingham had initially been housed in emergency accommodation (hostels or hotels) for anywhere between 2 weeks and more prolonged periods of up to 6 months before being moved to their current temporary accommodation. Monitoring data collected by the family reunion support service indicates that it took people accessing the service in the West Midlands 100 days on average to access temporary housing after initially being placed in emergency accommodation, compared to families in Glasgow who waited 4 days on average. In contrast to Birmingham council, Glasgow city council has a policy of providing temporary accommodation to the sponsor a few days before their family's arrival (British Red Cross, 2022b). Even those who had been in the UK longer and were more familiar with the housing system felt that they had very little or no choice in where they were housed, as in the case of Ms. Amaechi who had moved four times since living in Glasgow and was currently housed in permanent accommodation.

“I've got no choice. If I have my way, I don't know, anywhere they give me because we can't dictate, we can't say. Like when I got this house, you can't say no to your house. Whatever they give you, you have to just take it like that, you know.” (Female sponsor, Family Amaechi)

Although in theory, a person on the homeless register can challenge an offer of accommodation on the basis of it being unsuitable, they are encouraged to seek advice before refusing an offer as it puts them at risk of becoming “intentionally homeless”, thereby risking their right to homelessness provision (Citizens Advice, 2023; Shelter Scotland, 2023). Mr. Biar chose to check out of the hostel he was housed in in Birmingham just before he met his family from the airport as he was advised the council wouldn't house them until they were in the country. He then presented at Birmingham City Council offices with his wife and four children, and the whole family were housed in another hotel for 15 days before being moved to temporary housing. Mr. Malek was offered the choice to relocate to Birmingham from London after he was granted refugee status, at a time when he was homeless and living with friends. However, he goes on to describe the lack of choice in where he was housed; first in a hotel where he lived for 3 months before his family arrived and then in a hotel room outside Birmingham where the whole family lived altogether in one room for 50 days before being housed in temporary accommodation in Birmingham.

“They book for me actually at housing option. It's not my choice, it's their choice, and they book for me one room for all my family […]. We are me and my wife and four children in one room and there is no kitchen, there is no washing machine—nothing like that.” (Male sponsor, Family Malek)

Mr. Zandi similarly described the challenges of living in poverty and the associated lack of choice and control over housing:

“It was so difficult time for me because I did not have any money and they used to help me but when they came they moved us to a hotel. It was a two-bedroom hotel I think but it was really small for us. And what made me scared was that because it was the corona time and in the kitchen all the children used to touch everything, and I was so scared of my kids.” (Male sponsor, Family Zandi)

Most sponsors were unemployed when their families arrived and reliant on welfare benefits—the expense of funding the family reunion process or supporting their family's move may have also sent some people into debt (British Red Cross, 2022a). Mr. Zandi's experience speaks to the insecurity experienced by refugees living in emergency accommodation and also to the fear associated with living in cramped conditions and using shared facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. This resonates with the experiences of asylum seekers transferred to hotels during the COVID-19 public health protection measures (Vidal et al., 2021) an experience of rupture to daily life experience by the whole population:

“After my family arrived, we feel better, we feel more secure. And, now they're settled, my daughter started school but after lockdown, you know, so everything vanished, as you know.” (Male sponsor, family Heydari)

In contrast to the circumstances for the majority population, the disruption from COVID-19 came at a time when many of the families had not yet had time to start their lives in earnest, and many arriving spouses and children felt they did not have enough experience of their new locales to comment on them. In the words of Ms. Fikri:

“It is difficult, I can't comment like [my husband] because [he] has been here for around four years, I just recently joined and also just after a few months' lockdown, so it's very difficult to comment or to judge.” (Female spouse, Family Fikri)

Particularly for those families living in Birmingham, where many of their children had not yet been registered in school, much of their experience of life in the UK was characterized by “waiting”: waiting for a response from the council about moving to larger accommodation, waiting for school place for their children, waiting for a GP appointment and waiting for a place at college.

“I'm just waiting.” (Male sponsor, Family Zandi)

Despite the challenges of accessing the essentials in this early period of their integration journeys, the families expressed happiness at being safely reunited and, for some, lockdown was experienced as an opportunity to enjoy time together as a family. This happiness was expressed by some on the “wheels of life” where they had fully colored the “home and family section” or colored it in a bright color.

“My husband had been away from us for more than two years so to reunite again under the same roof and have a place to live in together as a family, especially my little daughter, she didn't know her father even before we came here. So, to reunite again and live as a family this is very bright, that's why we decided to colour it [the wheel of life] in brightly.” (Female spouse, Family Kuer)

“On the “home and family”, I coloured this full because I'm so happy to see my mum and my sisters after a very long time. Like, so I get to know them more than before.” (Female child, Family Amaechi)

Alongside the happiness of being reunited, some families reflected on being separated from extended family back home and, in missing them, expressed the challenges of negotiating transnational belonging in new spaces while simultaneously experiencing the painful process of loss through forced displacement, and the joy of being reunited in a safe place.

“I'm really thankful just now but it's that I miss my parents and my sisters as I don't have any brothers, I have only three sisters but it's the fact that I know that I cannot see them, but it really makes me sad thinking about them.” (Male sponsor, Family Zandi)

The impact on our research participants of loss in their settlement process—of having left behind loved ones in their home countries, and of having endured previous separation from family members—are discussed in more depth in Baillot (2023, this issue). In particular, Baillot discusses the practical and emotional implications of providing care for family members across space and time (in the past, present and future of the pivotal transition point of family reunion) on their opportunities to attach to new people and places. While recognizing the interrelated processes of loss of home and home-making (see for example Bunn et al., 2023), our research questions deliberately focused on participant's experiences of settling in the UK, and not on their experiences of loss and trauma in the process of displacement, unless they indicated a wish to discuss it.

3.3 Inclusive and exclusive spaces

Additionally, and often in spite of the negative experiences of waiting, insecurity and transience, interviewees commonly ultimately judged the character of an area by the people who lived there and the sense of welcome they had felt. This resonates with findings from Spicer (2008) on refugee experiences of places of inclusion and exclusion and on the impact of welcoming people and spaces on feelings of belonging compared to unsafe spaces that negated integration (see also Atfield and O'Toole, 2007; Darling, 2011; Baillot et al., 2020). For example, Mr. Malek had been moved multiple times during the asylum process between Lancaster, London and Liverpool finally ending up being offered to relocate to Birmingham where he was then housed in a hostel for 3 months before his family arrived. He did not feel at all safe in the hostel and describes it as “not a place for families”. Unable to apply for homelessness accommodation city prior to their arrival, Mr. Malek, his wife and their four children had to spend several hours in the council offices on the day they arrived in Birmingham, eventually being sent to emergency accommodation where they shared one hotel room for 50 days, The hotel was in remote location several miles outside of Birmingham, in a town with seemingly little ethnic diversity. And yet, the couple liked the area because of the welcome they felt from the people who lived there.

“Nothing is there […] but the people is very very good.” (Male sponsor, Family Malek)

“I didn't see much black [people] there. But you can't imagine that how nice they are … like you feel all of them know each other.” (Female spouse, Family Malek)

A smile or gesture of warmth and friendliness was enough for some to feel welcome and accepted. This resonates with Barwick who describes how “friendly recognition” (Barwick, 2017, p. 418) is just one indicator of a “willingness to connect” (Barwick, 2017) on the part of more established residents and an essential factor in progressing the multi-directional and reciprocal process of place-making. It also resonates with respondents in Atfield and O'Toole's (2007) study who identified these small gestures such as greeting people in the street as important indicators of integration.

“From the smile I could tell people were friendly and warm, you know.” (Female spouse, Family Heydari)

Conversely, when people felt a lack of willingness from neighbors to connect or worse: felt unsafe in their local neighborhoods; experienced anti-social behavior or tension from their neighbors; or racist attitudes and behaviors, this precluded them from feeling they could belong in that area. Mr. Fikri felt his neighbors were unwelcoming, saying:

“I feel like they [my neighbours] are a little bit conservative so it's not easiest to interact with them or make a kind of friendship or any kind of relationship with them” and concluding “it makes me feel like this is not the right place for me.” (Male sponsor, family Fikri)

Ms Amaechi similarly says of a previous area she lived in that it was not “the right place to be”:

“The people that lives there, they no, you know, it's not a good experience, the right place to be.” (Female sponsor, Family Amaechi)

She goes on to compare the previous area to the area she currently lives in, somewhere she describes a lot of antisocial behavior and lack of amenities, but one she wants to stay in because of the people living in her building and nearby, demonstrating not only the importance of how crucial the opportunities to meet people and interact are to processes of place-making, but also how positive spaces of interaction can make all the difference within wider geographic areas that are felt to be unwelcoming.

“Wow, they are great people. The area I live is not a good area, but this particular building where I live, they are so good.” (Female spouse, Family Amaechi)

In contrast, the Moradi family were happy with their accommodation, but had not made any local relationships. Much of their experience since arriving in Birmingham was characterized by feelings of isolation, exclusion and “protracted uncertainty” (Horst and Grabska, 2015); neither of the children had been registered in school, the sponsor was unemployed, and they were waiting to be offered alternative, permanent accommodation. The mother and daughter we spoke to both described the area as somewhere where they felt the other residents to be people different from themselves, who they could not connect with.

“I love my home, but not the area. […] There aren't many locals in our area. Mostly Pakistanis and Africans. They are loud, they drink a lot and they loiter a lot. It's not a very pleasant place to be.” (Female child, Family Moradi)

For many, the absence of conflict and threat was enough for them to judge the area to be “good” and somewhere they would like to stay.

“You know, before I heard [name of area] this area was trouble, but you know was totally opposite. This is a very, very good area, very happy, it's very quiet and we have got a very good relationship with the neighbour.” (Male sponsor, Family Karimi)

People's personal and familial circumstances were an additional factor in their opportunities to meet others and interact; English language proficiency, health and physical mobility were a big consideration for some interviewees, including Ms. Kuer who liked the area but was in unsuitable accommodation. Her health and mobility issues meant that she could rarely leave her flat, which was high up and only accessible by stairs, serving to enforce a degree of social isolation. Family Berhane wanted to move more centrally in Glasgow to be closer to the Eritrean community as they spoke little English and relied on them for practical support in navigating systems.

“See, the people from my community are very supportive. So especially in Birmingham, so if you've got any problems or if you face some issues, so they help you and support you with what to do. So especially because of the lack of the language I have.” (Male sponsor, Family Berhane)

Not enough is known about each families' socio-economic status in their home countries to draw any conclusions about how this impacted on opportunities to build social networks in their new locales, yet there were clear indications that not speaking much English was a clear added barrier to navigating the housing system. For more exploration on how the families in this research project navigated systems see (Baillot et al., 2023).

3.4 Places to meet

The reasons interviewees gave for either feeling like they could belong to an area or were “out of place” were not just based on experience but were also intrinsically tied to the felt opportunities to meet other people and embed themselves in local spaces and in “communities” of people. Closeness to amenities emerged as a factor underpinning how family members felt about the area they lived in. This was in part a practical consideration of being able to easily access essential goods and services such as schools, transport links, healthcare and shops. Under this lay a concern with being able to access spaces for interaction and opportunities for connection. For example, the Heydari family all expressed a wish to live closer to the city center; like many of the young people, the son was concerned with accessing central amenities such as leisure facilities. His mother articulated that it was not just the amenities in and of themselves, but the opportunity they offered to meet people:

“Probably, I'm not sure, but maybe just near the centre where there are more facilities, it would give us more opportunity to meet people or to socialise, even if we are somewhere near.” (Female spouse, Family Heydari)

This resonates with Feld (1981) focus theory that suggest the interactions between people are organized by the spaces and activities or “foci” that people structure their daily lives around, such as shops, schools and parks. For adults, the process of local place-making was negotiated through first meeting essential needs by registering with services such as schools, the GP and dentists, and then starting to embed in the area through interacting with people in the local shops and amenities or, in the works of Mr. Arok, “becoming customers”:

“When I talk about the settlement, that means I got my children to go to school and we registered with the GP, with the dentist., we know about the area. There are important places we needed like the shops, and we started to become customers for some shops.” (Male sponsor, Family Arok)

Typically, young people were preoccupied with spaces where they could interact with other children and young people such as local parks and shared gardens or where they could engage in shared activities such as football clubs. Particularly in lockdown, some children were spending more time interacting with friends in virtual spaces, through video games.

“I'm a social person and through this game I'm socialising with the Iranian or maybe non-Iranian friends, so I just feel, you know, I'm socialising through this game.” (Child, Family Karimi)

The gendered interactions of the families in our sample with people and spaces are explored by Baillot (2023, this issue) who discusses how the invisible labor of caring performed by women in the private realm of their homes in some instances restricted opportunities for their interaction in public spaces, compared to their male counterparts. The mosque is one example where men may have had more opportunities to expand their social networks Mr. Arok suggests that the mosque was a particularly important place for him, as a man, to connect with other Sudanese people.

“Friday afternoon prayer is one of the most important prayers and it's a must for the man to go to do it in the mosque” later adding “this is a main window I used to get in touch with the Sudanese community or Sudanese people.” (Male sponsor, Family Arok)

Our research highlighted instances of a re-negotiation of gender roles between reunited spouses in the UK, underscoring how gender relations and gendered spaces are also co-constructed differently across time and cultures (Massey, 1994). In addition to the gendered aspects, access to particular relationships and social networks were also different for male sponsors from their later arriving spouses by dint of having spent more time in the country as a single person without the day-to-day responsibilities of family life before their wives and children had joined them. Ms. Zandi reflects that she was not included in some of her husband's friendships and spaces where they interacted “outside” of the home:

“Yes, my husband a lot of friends but like most of them they don't have families so they're not just visiting us in our house, so they are just friends outside. They're only like men together.” (Female spouse, Family Zandi)

Unwanted spaces were not only those that people felt to be unsafe or unwelcoming, but also those that did not offer opportunities to meet and interact with others.

“That place was really isolating—nobody to play with, it's only park, no libraries, nothing there.” (Female spouse, Family Amaechi)

3.5 Navigating place-making through connections

This section turns attention to how families negotiated the process of adaptation to their new environments in Birmingham and Glasgow through friendships they made in the early stages (for arriving spouses and children) and at this transitional stage (for sponsors) of their settlement journeys. It highlights the different narratives family members employed in the process of place-making, according to their priorities and perspectives in making sense of their new lives and negotiating a sense of belonging.

People's aspirations to widen their social networks were dependent on the stage they were at in their personal and family integration journey, their needs and aspirations. Where some were focused primarily on meeting the family's immediate settlement needs and re-establishing bonds between themselves, others aspired to belong to a wider “community”. These comfortable “easy” connections played a crucial role for many families in being able to develop deep trusting friendships which tied them both to people and spaces.

However, this “step-by-step” process is not a linear trajectory, and those who had been in the country longer spoke to the continued insecurity and ruptures in their housing journey, which in turn disrupted their children's education and the whole family's social networks.

“Leaving their school in Manchester, they were so sad and when they got here as well, they getting familiar with people and then we got moved again.” (Female sponsor, Family Amaechi)

Friendships stood out as pivotal relationships which connected people to cities and neighborhoods and which influenced their desire to stay or leave, underlying the inextricable nature of space, place and social relations (Massey, 2005). The role of more formal relationships with organizations, and care experienced through them is explored in an earlier publication (Käkelä et al., 2023). These informal relationships offer insights into people's identities and the social and physical spaces where they saw opportunities to develop comfortable and trusting connections. Mr. Zandi articulates how familiarity with people and places had, over time, made him feel more embedded in Birmingham, saying:

“When I first came in here, I did not know anybody but now because I have lots of friends and I know people who were from Iran as well, so it makes me be more comfortable in here and I got used to the places, like I know how to go out and know the places.” (Male sponsor, Family Zandi)

From a child's perspective, the son from Family Arok says simply that until he made some friends at school who also spoke Arabic and could help him learn in class:

“I felt I'm a bit a stranger because my language is different.” (Male child, Family Arok)

This speaks to the axes along which people felt they shared similarities with others or the “bonds that tie” (Anthias, 1998, p. 570). Several interviewees strongly identified with people from the same country or who spoke the same language, referring to the comfort and ease of these friendships. Moving closer to the Sudanese communities in Birmingham and Glasgow were key drivers for the male sponsors from Family Biar and Family Arok in their decisions to relocate. Mr. Biar had chosen to return to Birmingham where he had originally claimed asylum before being dispersed to a small town near Newcastle and Mr. Arok had chosen to relocate to Glasgow from Belfast once granted status. Both had moved to the cities before their families arrived. For Mr. Arok, a friendship with someone from his own country was instrumental in his decision to move to Glasgow, again illustrating the relational nature of place-making. He says of the Sudanese friend he had met in Belfast:

“And sometimes there is like a chemistry between two people, so they get on well with each other and [name of friend] recommended for him to come to Glasgow. And what Arok noticed, the relationship between them and the communication is very easy and stuff, so he decided ‘I want to be part of this group or this community'. So, he made his mind to come to Glasgow rather than going to Edinburgh.” (Male sponsor, Arok Family)

Similarly, Mr. Biar had been drawn to move back to Birmingham to be part of the Sudanese network, saying:

“The first thing, we have a strong community in Birmingham. The time I have been there, I met a good network and friendship, and I like the city.” Male sponsor, Family Biar)

It is likely also that both men were also considering the needs of their families in moving to Glasgow and Birmingham, although neither explicitly cited it as the main reason for their move. Mr. Arok in particular had moved to Glasgow just before his family arrived and also cited the “high quality of education” in the city as a factor influencing his decision. In fact, many relationships between families from the same country were facilitated by friendships between their children who played together in shared spaces. The Berhane family met another Eritrean family in the hotel they were initially housed in and became friends, attending the same church together and taking their children to the local park, demonstrating the intersectional aspects of their identities that drew them together: their shared nationalities being one; their shared faith another; and the fact of their shared circumstances living in a hotel with young children in common. Ms Berhane says:

“So even our kids, so they were taking them, we were taking them to the park, and they were playing together. And then they have built a strong friendship, even more than us.” (Female spouse, Family Berhane)

However, not all interviewees were keen to connect with people from the same country or necessarily felt trustful of them as in the case of Mr. Fikri who preferred to spend time with Scottish friends, challenging the often-held assumption that shared origins or ethnicity are the basis for social bonds:

“I have friends from all the nationalities, but I feel more comfortable with my Scottish friends more than the people from my country.” (Male sponsor, Family Fikri)

Axes of difference are as illuminating as commonality in identity formation in new places; the lines along which people perceived others to be “like me” or “not like me”. Ms. Heydari had had limited opportunities to meet people before lockdown except through the church a few miles from where the family lived. However, members of the congregation were older than she was, and she couldn't therefore foresee developing friendships with the other women.

“So, I had the chance just to meet two or three ladies, they were lovely, we chat, but they were, kind of, not the same age range, they were very much older than me.” (Female spouse, Family Heydari)

The reasons for those who chose to move to Glasgow or Birmingham are also instructive as to some of the narratives around which characteristics of people and spaces that made the cities attractive to them. Mr. Gai had chosen to move to Birmingham from a small city in the Greater Manchester area after being granted refugee status but prior to his families' arrival in the UK. The reason he gave for his decision was that he wanted to be in a more multicultural city where he felt he and his family would have greater opportunities and be less at risk of encountering racist attitudes and behaviors. In contrast to Mr. Biar and Mr. Arok, Mr. Gai had not explicitly moved to be closer to the Sudanese community and in fact said he hadn't found it as easy to connect with people in Birmingham compared to in Glasgow, where he had been located for a short while before being dispersed to a town outside Manchester, and where he still had a network of friends.

“When I was in the small city, [name], no opportunity, I was suffering from the racism, you know? It's a very small village or a city. Unfortunately, there is not many educated people and even they didn't have any clue what is a refugee. So, I don't know, we were just victim of racism. But here I chose Birmingham because it's a big city, multicultural, you know? Just it's like a culturally different people, so that's why I chose Birmingham.” (Male sponsor, Family Gai)

Finally, Mr. Malek also from Sudan, chose to take the offer to move to Birmingham from London—he had originally arrived in London, then been dispersed to Liverpool and Lancaster before being granted status and returning to London to look for work. He had not identified Birmingham as a place to move to, but rather moved because he had been offered accommodation there. Comparing London to Birmingham, he concluded that the latter was better suited to families saying:

“For family I don't think it's good because it's very expensive and not easily to find the accommodation.” (Male sponsor, Family Malek)

The desire to live in a multicultural area was common to a number of interviewees who felt it offered more acceptance and less threat. Ms. Zandi went further to comment on the freedoms offered in Birmingham, possibly comparing her experience to a lack of freedom she had experienced because of her gender, as a woman living in Iran.

“It's not like in my country there are some things that are forbidden, but here you're free to do whatever you want.” (Female spouse Family Zandi)

Resonating with Mr. Arok's experience and again illustrating the role of friendship in place-making, she adds:

“It's a big city and I really love because I made friends, so I used more here, and I am starting to learn the locations and know where they are.” (Female spouse Family Zandi)

Together, these findings illustrate the different frames of reference through which people negotiated pathways to belonging in Birmingham and Glasgow and the meanings they attached to their interactions with people in spaces. Despite the lack of choice over where to live, these practices of place-making are active and agentive in fostering a sense of belonging. Summing up how it is through meaning-making that people make spaces into “credible” places, Ms. Amaechi says of the area she lives in:

“it's only very credible because of the connection I have, that's why, because you need people, you can't live by yourself, you need somebody.” (Female sponsor, Family Amaechi)

4 Discussion

This article has sought to analyse how refugee families negotiate processes of integration in the early stages of being reunited and adapting to their new lives in the cities of Birmingham and Glasgow. Drawing on Massey's progressive concept of space and place (Massey, 1991, 2005), the author argues that the concept of place-making, similar to the concepts of “emplacement” (Schiller and Çaglar, 2013; Wessendorf and Phillimore, 2019) and “homemaking” (Boccagni and Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2023) provides a lens through which to understand how families actively make meaning of their new locales and negotiate transnational belonging through their everyday interactions with people in the spaces available to them. Considering their particular opportunities for interaction and the differential “social conditions, opportunities and exclusions” (Anthias, 1998, p. 564) offered in these spaces, the author demonstrates how the interviewees exercise agency and resilience in the active process of place-making, despite living in unchosen spaces.

Place-making adds to understandings of the relational processes of integration by re-contextualizing the interactions between people with their spatial environments (Lenette et al., 2013), and analyzing the processes by which identities and places are co-constructed through the interactions between people in spaces (Massey, 2005). The identities of the men, women and children interviewed were constituted and reconstituted (Spicer, 2008) in their new locales, according to the axes along which they saw opportunities for interaction and connection with others. Rather than falling back on assumptions that the pathways to belonging were necessarily predicated on shared origins or characteristics, the article has sought to analyse the “routes” rather than “roots” (connections to people through land, ethnicity or “cultural” heritage, see for example (Malkki, 1992) people traced in making sense of their new locales and negotiate a sense of belonging to them.

In tracing the interviewees' own narratives on their routes to place-attachment and belonging, the article has offered insight into how the participants negotiated transnational belonging as a process of recognizing commonalities and diversity (Anthias, 1998) through their friendships. The interviewees did not have choice over where they lived, but they did exercise agency and intentionality in choosing who to connect with in the spaces and places they lived in. Rather than assuming categories of belonging, the author explored how the families exercised choice in the people and spaces they attached to, within the constraints and opportunities of their new locales. Further, in contextualizing the inequalities in access to spaces, places and people, the author recognizes that these practices of place-making constitute an everyday “micropolitics” (Amin, 2002) of belonging. In doing so, the article pays attention to “boundaries of exclusion as well as boundaries constructed through identity and common experience” (Anthias, 1998, p. 569). This paper argues against analyzing the negotiation of identity and belonging through the lens of ethnicity, and for careful attention to the positionality of people in spaces, and their particular frames and contexts within which they negotiate their own pathways to integration at the level of the city and neighborhood.

The bonds that tie (Anthias, 1998) and the spaces in which they negotiated processes of place-making and belonging are forged through intersectional identities and experience, not always necessarily through shared origins. The findings contest the binary conceptualization in social capital of social bonds as exclusionary, and bridges and inclusive (Putnam, 2000) and adds to a growing body of literature which critiques the conflation of social bonds with ethnicity (Anthias, 1998; Barwick, 2017; Demireva, 2019; Baillot et al., 2023). Rather than essentializing people or spaces, the article has sought to critically analyse who people choose to build friendships with, and within which “opportunity structures” (Phillimore, 2021).

It recognizes the politics of place-making in exploring how belonging is negotiated by refugee families within the constraints and opportunities of uneven spaces and unequal relations. Despite the “architecture of exclusion” (Mountz, 2011) woven into the housing allocation process, refugee families negotiate connection, attachment and belonging to the neighborhoods and cities they are housed in but have not chosen, through the people they meet and the relationships they make. In practicing place-making, negotiating and navigating pathways to inclusion and belonging, the families exercise agency in spite of uncertainty, precarity and exclusion. In the words of Horst and Grabska.

“Coming to terms with uncertainty, then, is often not about calculated risk taking but about coping through hope, waiting, negotiating, and navigating.” (Horst and Grabska, 2015, p. 5)

Coming to terms with and navigating in spite of uncertainty is conceptualized as agency, understood as a “temporally embedded process of engagement informed by the past and oriented toward the future and present” (Emirbayer and Mische, 1998 cited in Vidal et al., 2023, p. 14). In paying attention to the day-to-day negotiation of pathways situated in “person-environment interactions” toward belonging the author also highlights the resilience (Lenette et al., 2013) of families in place-making. It draws on Lenette et al. and Vidal et al. in conceptualizing resilience as a “set of behaviors over time that reflect the interactions of people with their environment” (Vidal et al., 2023, p. 15).

5 Conclusion

Recently reunited refugee families are at a very particular transition point in their integration journeys, navigating the challenges of meeting the essential needs of the family, such as accommodation and benefits, education and healthcare. They are also negotiating the longer-term processes of place-making in unfamiliar and unchosen spaces. There is a political imperative to pay attention to the constraints and opportunities of the spaces within which they are housed and the contexts in which they are required to navigate insecure and unsuitable housing arrangements, poverty and disadvantage. There is an equal duty on those with power to recognize the agency and resilience with which the individuals and families practice place-making and progress toward transnational belonging, in spite of the multiple moves, ruptures and disruptions in their housing pathways and integration journeys. Further, there is an urgent need for the UK government to extend rather than reduce the move-on period for newly granted refugees and to co-ordinate an approach to housing people seeking asylum and refugees which supports rather than undermines their opportunities to integrate into local communities.

Data availability statement

The datasets in this article are not publicly available due to the potential for identifying vulnerable participants (refugee families). Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bGtlcnIyQHFtdS5hYy51aw==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Queen Margaret University Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Informed consent for participation in this study was sought from all participants, including for children aged under 18, from their parents/guardians.

Author contributions

LK is the sole author of this paper and agrees to be accountable for the content of the work.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Data collection for this study was funded by the EU Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF). Grant Number: UK/2018/PR/0064.

Acknowledgments

Research design, data collection and analysis was jointly conducted with my colleagues from the research team based at Queen Margaret University's Institute for Global Health and Development: Helen Baillot, Arek Dakessian, and Alison Strang. The author wishes to thank the families who so generously gave their time and shared their experiences with us, and our third sector project partners without whom this research would not have been possible. Thank you also to Marcia Vera Espinoza for her invaluable support and to the reviewers for their thoughtful feedback.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ager, A., and Strang, A. (2004). Indicators of Integration: Final Report. London: Home Office. Available online at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20110218141321mp_/http://rds.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs04/dpr28.pdf (accessed September 9, 2023).

Amin, A. (2002). Ethnicity and the multicultural city: living with diversity. Environ. Plann. A 34, 959–980. doi: 10.1068/a3537

Anthias, F. (1998). Evaluating “diaspora”: beyond ethnicity? Sociology 32, 557–580. doi: 10.1017/S0038038598000091

Atfield, G., and O'Toole, T. (2007). Refugees' Experiences of Integration Public Faith and Finance View Project Muslim Engagement in Bristol View Project. London: Refugee Council and University of Birmingham.

Baillot, H. (2023). “I just try my best to make them happy”: the role of intra-familial relationships of care in the integration of reunited refugee families. Front. Hum. Dynam. 5, 1248634. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2023.1248634

Baillot, H., Kerlaff, L., Dakessian, A., and Strang, A. (2020). Pathways and Potentialities: the Role of Social Connections in the Integration of Reunited Refugee Families. Available online at: squarespace.com (accessed September 9, 2023).

Baillot, H., Kerlaff, L., Dakessian, A., and Strang, A. (2023). ‘Step by step': the role of social connections in reunited refugee families' navigation of statutory systems. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 49, 43134332. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2023.2168633

Barwick, C. (2017). Are immigrants really lacking social networking skills? The crucial role of reciprocity in building ethnically diverse networks. Sociology 51, 410–428. doi: 10.1177/0038038515596896

Birmingham City Council (2023). Community Cohesion Strategy for Birmingham. Available online at: https://www.birmingham.gov.uk/downloads/download/2606/community_cohesion_strategy (accessed June 8, 2023).

Boccagni, P., and Hondagneu-Sotelo, P. (2023). Integration and the struggle to turn space into “our” place: homemaking as a way beyond the stalemate of assimilationism vs transnationalism. Int. Migr. 61, 154–167. doi: 10.1111/imig.12846

Brun, C. (2015). Active waiting and changing hopes toward a time perspective on protracted displacement. Soc. Anal. 59, 19–37. doi: 10.3167/sa.2015.590102

Bunn, M., Samuels, G., and Higson-Smith, C. (2023). Ambiguous loss of home: syrian refugees and the process of losing and remaking home. Wellbeing Space Soc. 4, 100136. doi: 10.1016/j.wss.2023.100136

Citizens Advice (2023). Refusing an Offer of an Unsuitable Council Home. Available online at: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/housing/social-housing/applying-for-social-housing/refusing-an-unsuitable-council-home/ (accessed September 31, 2023).

Darling, J. (2011). Giving space: care, generosity and belonging in a UK asylum drop-in centre. Geoforum 42, 408–417. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.02.004

Demireva, N. (2019). Briefing: Immigration, Diversity and Social Cohesion. Oxford: The Migration Observatory.

Feld, S. L. (1981). The focused organization of social ties. Am. J. Sociol. 86, 1015–1035. doi: 10.1086/227352

Hill, E., Meer, N., and Peace, T. (2021). The role of asylum in processes of urban gentrification. Sociol. Rev. 69 259–276. doi: 10.1177/0038026120970359

Home Office (2022). Allocation of Asylum Accommodation Policy. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/651e85ee7309a10014b0a882/Allocation+of+accommodation.pdf (accessed October 10, 2023).

Horst, C., and Grabska, K. (2015). Introduction flight and Exile—uncertainty in the context of Conflict-Induced displacement. Soc. Anal. 59, 1–18. doi: 10.3167/sa.2015.590101

Hynes, P. (2011). The Dispersal and Social Exclusion of Asylum Seekers: Between Liminality and Belonging. Bristol: Policy Press.

Käkelä, E., Baillot, H., Kerlaff, L., and Vera-Espinoza., M. (2023). From acts of care to practice-based resistance:refugee-sector service provision and its impact(s) on integration. Soc. Sci. 12. doi: 10.3390/socsci1201003

Kearns, A., and Whitley, E. (2015). Getting there? The effects of functional factors, time and place on the social integration of migrants. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 41, 2105–2129. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2015.1030374

Kerlaff, L., and Käkelä, E. (forthcoming). Understanding Good Places to Meet: The Role of 'Common Interest Infrastructures' in Promoting Social Cohesion in Superdiverse Societies. London: British Academy.

Laryea, K. (2016). Expert rater as deep listener in complex performance-based assessments (Dissertation). ProQuest LLC, Parkway, CA, United States.

Lenette, C., Brough, M., and Cox, L. (2013). Everyday resilience: narratives of single refugee women with children. Qualit. Soc. Work 12, 637–653. doi: 10.1177/1473325012449684

Malkki, L. (1992). National geographic: the rooting of peoples and the territorialization of national identity among scholars and refugees. Cult. Anthropol. 7, 24–44. doi: 10.1525/can.1992.7.1.02a00030

Massey, D. (1991). A Global Sense of Place. Available online at: http://www.amielandmelburn.org.uk/collections/mt/index_frame.htm (accessed December 9, 2003).

Matua, G. A., and Van Der Wal, D. M. (2015). Differentiating between descriptive and interpretive phenomenological research approaches. Nurse Res. 22, 22–27. doi: 10.7748/nr.22.6.22.e1344

Mcphail, G. (2021). A Housing Practitioners' Guide to Integrating People Seeking Protection and Refugees. Scottish Refugee Council. Available online at: https://www.scottishrefugeecouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Scottish-Refugee-Council-Housing-Practitions-Guide-2021-1.pdf (Accessed October 31, 2023).

Meer, N., Peace, T., and Hill, E. (2019). Integration Governance in Scotland Accommodation, Regeneration and Exclusion. University of Edinburgh and University of Glasgow. Available online at: https://www.glimer.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Scotland-Accommodation.pdf (Accessed October 31, 2023).

Mountz, A. (2011). Where asylum-seekers wait: feminist counter-topographies of sites between states. Gender Place Cult. 18, 381–399. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2011.566370

National Records of Scotland (2022). Glasgow City Council Area Profile. Available online at: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files/statistics/council-area-data-sheets/glasgow-city-council-profile.html (Accessed August 24, 2023).

Ndofor-Tah, C., Strang, A., Phillimore, J., Morrice, L., Michael, L, Wood, P., et al. (2019). Home Office Indicators of Integration Framework 2019. 3rd Edn. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/835573/home-office-indicators-of-integration-framework-2019-horr109.pdf (accessed October 9, 2023).

Nelson, A., Rödlach, A., and Williams, R,. (eds.) (2019). The Crux of Refugee Settlement: Rebuilding Social Networks. London: Lexington Books.

Noon, E. J. (2018). Interpretive phenomenological analysis: an appropriate methodology for educational research? J. Persp. Appl. Acad. Pract. 6, 75–83. doi: 10.14297/jpaap.v6i1.304

O'Reilly, Z. (2018). “Living Liminality”: everyday experiences of asylum seekers in the “Direct Provision” system in Ireland. Gender Place Cult. 25 821–842. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2018.1473345

Phillimore, J. (2021). Refugee-integration-opportunity structures: shifting the focus from refugees to context. J. Refugee Stud. 34, 1946–1966. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feaa012

Provan, B. (2020). Extending the “move-on” Period for Newly Granted Refugees: Analysis of Benefits and Costs. Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion London School of Economics for the British Red Cross Policy, Research and Advocacy Team. Available online at: https://sticerd.lse.ac.uk/dps/case/cr/casereport126.pdf (accessed September 9, 2023).

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York, NY: Touchstone.

Schiller, N. G., and Çaglar, A. (2013). Locating migrant pathways of economic emplacement: thinking beyond the ethnic lens. Ethnicities 13, 494–514. doi: 10.1177/1468796813483733

Shelter Scotland (2023). Refusal of Offer. Available online at: https://scotland.shelter.org.uk/professional_resources/legal/homelessness/local_authority_duties/refusal_of_offer? (accessed August 31, 2023).

Spencer, S., and Charsley, K. (2021). Reframing ‘integration': acknowledging and addressing five core critiques. Compar. Migr. Stud. 9. doi: 10.1186/s40878-021-00226-4

Spicer, N. (2008). Places of exclusion and inclusion: asylum-seeker and refugee experiences of neighbourhoods in the UK. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 34, 491–510. doi: 10.1080/13691830701880350

The Guardian (2023). Thousands of Refugees Could Face Homelessness After Home Office Policy Change. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/15/thousands-of-refugees-could-face-homelessness-after-home-office-policy-change (accessed September 9, 2023).

Vidal, N., Sagan, O., Strang, A., and Palombo, G. (2023). Rupture and liminality: experiences of Scotland's refugee population during a time of COVID-19 lockdown. SSM Qualit. Res. Health 4, 100328. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmqr.2023.100328

Vidal, N., Salih, M., Strang, A., Sagan, O., and Smith, C. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 Restrictions on Scotland's Refugees: Sudden-Onset Isolation in a Neglected Population Group. Research report to the Chief scientist's office, Scottish Government. Available online at: https://www.qmu.ac.uk/media/ohqeqzxa/csocovid_final-report_14-sep-2021.pdf (accessed October 9, 23).

Walsh, D. (2017). The Changing Ethnic Profiles of Glasgow and Scotland, and the Implications for Population Health. Glasgow Centre for Population Health. Available online at: https://www.gcph.co.uk/assets/0000/6255/The_changing_ethnic_profiles_of_Glasgow_and_Scotland.pdf (accessed February 9, 2023).

Wessendorf, S. (2019). Migrant belonging, social location and the neighbourhood: recent migrants in East London and Birmingham. Urban Stud. 56, 131–146. doi: 10.1177/0042098017730300

Wessendorf, S., and Phillimore, J. (2019). New migrants' social integration, embedding and emplacement in superdiverse contexts. Sociology 53, 123–138. doi: 10.1177/0038038518771843

Keywords: integration, place-making, belonging, refugee, families

Citation: Kerlaff L (2023) “Now we start to make it like home”: reunited refugee families negotiating integration and belonging. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1287035. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1287035

Received: 01 September 2023; Accepted: 31 October 2023;

Published: 23 November 2023.

Edited by:

Clayton Boeyink, University of Edinburgh, United KingdomReviewed by:

Zlatko Hadzidedic, International Center for Minority Studies and Intercultural Relations, BulgariaPetek Onur, University of Flensburg, Germany

Copyright © 2023 Kerlaff. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Leyla Kerlaff, bGtlcmxhZmZAcW11LmFjLnVr

Leyla Kerlaff

Leyla Kerlaff