- School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom

As nationalism rises worldwide, understanding the relevance of national identities is at a premium in both the study of mass political behavior and the analysis of social movements. Drawing on research in social psychology, this study explores interactions among national and supranational identities using the concepts of identity interference (i.e., negative interactions) and identity complementarity (i.e., positive interactions). These interactions extend beyond the direct effects of identity considered in many previous studies. Focusing on interactions centers the analysis on the contextual aspects of identity during nationalist mobilizations. Survey data from Scotland demonstrate that interactions among Scottish, British, and European identities were consequential for mobilizing support for Scottish independence in 2019. Strong evidence indicates interference between Scottish and British identities. European and Scottish identities complement one another among independence supporters but not in the general population. The possibility of interference between European and British identities is backed by only mixed results. The timing of this study in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum was likely relevant to its findings on European identity. Overall, this research illustrates the benefits of widening the empirical examination of multiple identities in the social sciences.

Introduction

A rising tide of nationalism has spread across the globe in recent years (Bieber, 2022). This new nationalism has followed diverse forms, exhibiting both inclusive and exclusive variants, drawing inspiration alternatively from the left and right sides of the political spectrum (Wimmer, 2019). Given the extensiveness of its reach and power to motivate individuals to endorse heterogeneous causes, nationalism has been described by Mylonas and Tudor (2023, p. 60) as “the most important political ideology of the modern era….” Consequently, it is crucial for scholars to further understanding of what contributes to or undercuts nationalist mobilizations.

The extent to which national identities are present and salient in a place is a critical factor affecting the dynamics of nationalist politics (Cederman, 1995; Lacroix, 1996; Bond, 2006; Reeskens and Wright, 2013; McCrone and Bechhofer, 2015; Bayram, 2019) (Johns, unpublished)1. A national identity is a psychological attachment that an individual has to a nation or to an imagined community with aspirations to become a nation (Anderson, 1983; Brewer, 1991). Prior research has shown that individuals may hold multiple political identities—sometimes multiple national identities—at the same time (Moreno and Arriba, 1996; Brewer, 1999; Simon and Grabow, 2010; Martinovic and Verkuyten, 2014).

A weak point in this body of research is its limited appreciation of how national identities interact and how these interactions are associated with mobilizing nationalist causes—beyond the direct effects of national identities. Neglecting interactions ignores a vital component of context that is relevant when salient identifications co-occur with one another. It is typical for scholars to recognize that national identities are multiple but to conceptualize that multiplicity discretely—that is, they view identities as either multiple or not multiple. While the discrete approach can be valuable, it skirts the potential for continuous and non-linear interactions that may be vital to complex nationalist politics. These interaction effects may differ when the identities in question are operating within mass political behavior or social movements.

This article explores the potential for complex interactions among national identities during a period of nationalist mobilization at the level of mass politics as well as in grassroots politics. To do so, it draws upon advances in social psychology that conceptualize interacting identities in a continuous fashion. Specifically, it uses the concepts of identity interference advanced by Settles (2004, 2006; see also Karelaia and Guillén, 2014) and identity complementarity, derived from the scholarship of Burke and Stets (2009). These concepts provide analytical tools for modeling the ways that identities may impinge on, reinforce, or make no difference to one another during political mobilizations. They center the contextual aspects of identity and extend beyond the direct effects considered in many previous studies.

In order to test hypotheses on identity interference and complementarity, this study examines the mobilization of the independence movement in Scotland in 2019. Scotland is one of the four nations (Keating, 2020, p. 1) that encompass the United Kingdom (UK), along with England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Scotland was previously an independent nation before the crowns of England and Scotland were unified in 1603 and their parliaments were merged in 1707. Debates about Scottish independence are, thus, contests over whether Scotland should be a nation within the UK or outside of it. These debates are principally about constitutional politics, rather than about ethnicity (King, 2012). The ebb and flow of the tides of nationalism influences the balance of forces in these contests.

Since the formation of the UK, various groups have agitated for Scottish independence from the UK (Brand, 1978). In 1997, a referendum in Scotland supported the restoration of the Scottish Parliament (effective in 1999), with powers devolved to it by the UK central government. Since 2007, the Scottish National Party (SNP)—a pro-independence party—has led the parliament as the largest party. Almost a decade ago, a popular referendum on the question of independence was defeated in September 2014 by a vote of 45 percent “Yes” to 55 percent “No” (McInnes et al., 2014). Despite this defeat, mobilization for Scottish independence flared up again in the aftermath of the 2016 Brexit referendum in which the UK chose to leave the European Union (EU) over the objections of Scottish voters, approximately two-thirds of whom voted to remain in the EU (McCrone, 2017; LexisNexis, 2022). Selecting 2019 as the period for study—a peak time of nationalist mobilization—permits investigation of interactions among British and Scottish national identities at a time and place where the supranational European identity was also highly salient.

This article analyzes three types of pro-nationalist mobilization in Scotland: (1) vocalized support for the cause of independence; (2) physical attendance at pro-independence street demonstrations; and (3) membership in a pro-independence organization. In doing so, it brings together traditional data on political behavior with original data on social movement activities at the grassroots, thus helping to rectify the systematic neglect of social movements in scholarship on Scotland (Keating, 2020, p. v). Data for the first type of mobilization were obtained from the British Election Study (2019) Wave 16, which was fielded from May to June 2019. Surveys containing the second and third types of data were fielded by the authors of the study at pro-independence street demonstrations from August to November 2019.

Analysis of the British Election Study (BES) and street demonstration surveys reveals evidence of statistically significant interactions among Scottish, British, and European identities with respect to supporting Scottish independence. These interactions are in addition to the direct effects of identity documented in the models. Scottish and British identities display statistically significant levels of interference for all three types of mobilization, although this result does not rule out that the identities are complementary for some people. Scottish and European identities indicate complementarity for attending demonstrations and organizational membership but not for supporting the cause. British and European identity interactions appear to follow a non-linear pattern in supporting the cause and interference with respect to attending demonstrations but, for the third type of mobilization (organizational membership), the interaction fails to meet the conventional threshold for statistical significance.

The results of this study are relevant for making sense of how nationalist mobilizations take place. Nationalist supporters may be driven not only by their loyalty to a national identity but also by how that identity interacts with other loyalties, in both mass publics and grassroots theaters. Thus, it matters when salient identities coexist with one another in political arenas. Further, the results suggest that supranational identities can enter nationalist politics not only to undercut a national identity but also to reinforce a national identity (as evidenced by the Scottish-European complementarity). The implications of these findings extend beyond nationalism to mobilization behind other identities; for example, it informs research on the intersection of race, gender, and other dimensions of difference that is centrally concerned with interactions among identities (hooks, 1984) [sic.].

This article proceeds in six parts. First, it employs social psychology to theorize the implications of identity interference and complementarity on nationalist mobilization. Second, it outlines hypotheses for the direct effects of identity and its interactions during Scottish independence mobilizations. Third, it lays out the research design of the study and data collection processes. Fourth, it reports the statistical results. Fifth, it considers the potential endogenous effects of mobilization on identity and their consequences for interpreting the results. Finally, it discusses the implications of this study for, and future research on, nationalism, identity, and social movement mobilization.

Theorizing interacting identities

This section theorizes interacting identities in three parts. First, it clarifies the meaning of identity. Second, it explains how identities can be multiple and why that matters in Scotland. Third, it presents interference and complementarity as ways of interpreting identity interactions beyond the direct effects of identity.

In the setting of this study, identity refers to the attachment that an individual has to a social group (existing or imagined), such as a nation, a gender, a class, or a profession. Social psychologist Tajfel (1981, p. 255) defined social identity as “that part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from [their] knowledge of [their] membership of a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership” (emphasis in original). This conceptualization sets up an identity as forging a micro–macro connection between an individual and a large social group. While the present study focuses on national identities, it is immediately apparent that an identity can link an individual to any number of groups, as demonstrated in Nagar’s (1997) analysis of Tanzanian Asians.

As there is nothing about the definition of identity that implies that it must be exclusive, it is possible—indeed, likely—that individuals simultaneously hold a wide range of social identities. With respect to the identities that are the focus of this study, it is even possible to hold multiple national (or supranational) identities at the same time. Being born in, living in, or having ancestors from Scotland may all be reasons for a person to identify as Scottish. The same person may identify as British, perhaps embracing symbols of the nation, such as the king, the prime minister, or the Union Jack.

Extensive prior research on national identities in Scotland is consistent with this perspective on the salience of multiple, coexisting national identities. As McCrone (2020) documented, people may hold identities classifiable as “nationalist” or “dual.” Nationalists are people who understand themselves as either more Scottish than British or as more British than Scottish. In contrast, dual identities exist in people with equal (or roughly equal) attachments to Scotland and Britain. Consistent with what Torrance (2020) has referred to as “nationalist unionism,” these individuals may be able to accept Scottishness and Britishness simultaneously and without irresolvable internal conflict.

Early examinations of Scottish and British identities drew upon work by Juan José Linz and Luis Moreno (explained in Moreno and Arriba, 1996; Moreno, 2006). Their approach asked respondents to place their identities on a continuum from “Scottish, not British” to “British, not Scottish,” with “Equally Scottish and British” indicating a midpoint or dual identity. More recent studies (e.g., McCrone, 2019) have allowed respondents to indicate Scottish, British, and European identifications on separate scales—rather than on a single continuum—thus expanding the dimensionality of identity measurement.

Although there is no simple and direct relationship between identities and individuals’ views on policy questions, myriad studies have demonstrated that there are significant associations between the balance of these identities and the degree of support for nationalist and pro-Union positions (see, inter alia, Pattie and Johnston, 2017; Merino, 2020; Henderson et al., 2022). Yet these studies documented only the direct effects of national identities, rather than the types of interactive effects that are the focus of the present study.

Holding either nationalist or dual identities in Scotland would not preclude a person from also identifying with the European project, embodied as a geographic region of the world, as people with common ancestries, or through institutions designed to promote cooperation for the common good. There is no reason that a person cannot identify as Scottish, British, and European at the same time. Similarly, it is possible to dually identify as Ukrainian and Russian, as Chinese and a Hongkonger, as Arapaho and an American, or with many other different pairs of nationalities. In these instances, it is possible for identities to have separate effects on an individual’s attitudes and behavior, as illustrated in research by Simon and Grabow (2010) on German and Russian identities.

Even if an individual aspires to honor all their multiple identities equally and independently, events in the world may conspire to make that difficult or impossible. For instance, the Russian invasions of Ukraine in 2014 and 2022 drove a wedge between Russian and Ukrainian identities (Eras, 2023). Conversely, widespread immigration from Ireland to America as a result of famine and economic depression brought Irish and American national identities more closely together (Kenny, 2014). In both examples, national identities may interact to prop each other up or cut one another down, depending on the situation. Studies that approach these situations discretely (e.g., Kang, 2008; Klandermans, 2014; Smithson et al., 2015)—thinking of individuals with national identities that are “dual” or “not dual”—may miss out on important subtleties in how identities interact.

Settles (2004, p. 487) observed that “the combination of identities are not always easy to negotiate.” In these situations, identity interference may be present, which occurs “when the expectations and norms associated with one identity interfere with the enactment of another identity” (Settles et al., 2009, p. 856). Interference may occur because the standards set by one identity tend to be inconsistent with the standards set by another identity (Burke and Stets, 2009, p. 184). For example, feelings of pride for the flag of one nation (the standard for nation A) may create dissonance when singing the national anthem of another nation (the standard for nation B). When this happens, the individual may feel the need to determine which identity is more important to them; when Russia invades Ukraine, a Ukrainian-Russian is naturally pressed to take sides in the conflict.

Inspired by the analysis of Burke and Stets (2009, p. 191), we define identity complementarity as the degree to which identities reinforce each other when they become closer to one another in strength. They do this by bringing situationally relevant meanings to bear on a person’s self-understanding of political events (Burke and Stets, 2009, pp. 176, 180). For example, as a person develops a stronger self-identification as Chinese that may tend to stabilize their political support for the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions, a political party that espouses Chinese nationalism. It may do this by helping to understand and interpret the decisions and actions of the Federation in the midst of a complex reality. In this situation, the strengthening of Chinese identity may help to verify a Hongkonger’s identification with the Federation (see Burke and Stets, 2009, p. 189).

Interference and complementarity exhibit gradations depending on the situation. For example, the interaction between Ukrainian and Russian identities is likely greater for a person living in southeastern Ukraine, somewhat less for those living in Poland, and still less for those living in Chicago—possibly (in part) as a function of physical distance from the war zone. These gradations allow for the possibility of capturing non-linearities that may be prompted by threshold effects in the meaning of identities.

Introducing interference and complementarity into a theory of identity presents a subtle but consequential ontological shift. Rather than imagining identities as having separate—and separable—effects on actors, the interactive approach asserts that the copresence of identities matters. This perspective moves away from thinking of identities as a fixed part of a person’s self and toward thinking of identity as something expressed or felt differently depending on the situation. For example, a person’s desire for an independent Catalan nation may depend not only on the extent to which they identify with Catalonia but also on the extent to which they identify with Europe. European identities could be shaped by factors such as the that way local secondary schools teach about European institutions. In this case, the compatibility or lack of compatibility of Catalan and European identities may shift mobilization dynamics, potentially in varied ways with unfolding events, such as conclusions recently announced by the European Council. Thus, the consequences of Catalan and European identities may become inseparable from one another. In such a scenario, we could not fully appreciate the consequences of Catalan identities until we were informed about coexisting European identities and their salience. These identities must be investigated jointly.

Not all people need to experience interference or complementarity in the same way. It is possible for some people to see two identities as complementary, while many others—even the majority—perceive interference. The opposite pattern is possible as well, with some people encountering interference in cases where most others embrace complementarity. Similarly, it is possible for a person to experience ambivalence, with some aspects of an identity posing interference and other aspects presenting complementarity. Identity interactions are likely heterogeneous across persons. Nevertheless, identities may have a general logic that allows us to hypothesize certain patterns of interaction, as we do in the next section.

Hypothesized effects for identity and its interactions

The framework established in this article leads to the anticipation of both direct and interactive effects of national identity on mobilization into the Scottish independence movement. The direct effects of Scottish and British identities on support for nationalist mobilization are relatively well established in the extant literature. Existing evidence documents the positive direct effects of strong Scottish identities on nationalist support and corresponding negative (or null) direct effects of strong British identities on the same (Henderson et al., 2015; McCrone and Bechhofer, 2015; Morisi, 2018). The direct effects of European identities are less clear because of dynamics in the political landscape.

European identities appear to have developed a tighter association with Scottish nationalism since the SNP shifted its policy positions to be more pro-European and as the outcome of the Brexit referendum alienated many people in Scotland (Curtis and Montagu, 2018; McCrone, 2019). Aligning Scottish and European identities at the individual level is consistent with recent research, suggesting that it is possible for supranational identities (such as cosmopolitanism) to be compatible with national identities and pro-national attitudes, such as the willingness to go to war for one’s country (Bayram, 2019). These findings swing expectations toward a direct positive effect of European identities on support for the nationalist cause, though this expectation is not as clear as it is for the direct effects of Scottish (positive) and British (negative) identities.

Investigating interaction effects asks the question of whether Scottish, British, and European identities have associations with one another that extend beyond the direct effects of those identities. In the case of Scottish and British identities, a negative interaction effect is fairly likely, though certainly not absolutely necessary. A person who has a strong Scottish identity and a strong British identity is likely to experience considerable cognitive dissonance during independence debates from the feeling that they are unable to meet the identity standard for one or the other of the identities, yet some people do effectively reconcile these tensions. Conversely, a person who is high in either Scottishness or Britishness—but has a low level of identification with the other identity—would probably experience little internal struggle in deciding whether to support the independence movement. Thus, they would likely feel free to endorse the movement if they were high in Scottishness or oppose (or ignore) the movement if they were high in Britishness. The pattern of these expectations suggests interference.

The expected interaction between European-Scottish and European-British identities is more likely to be contingent on recent political events than is the case for Scottish-British interactions. At the time of this study in 2019, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson was working hard to pull Britain out of the EU by “get [ting] Brexit done” (Usherwood, 2019). Johnson sought to translate the results of the 2016 Brexit referendum into an actual legal withdrawal of the UK from the EU, which was ultimately achieved in January 2020. On the contrary, the SNP—a leading voice for the independence movement—had taken the position that Scotland would rejoin the EU if it secured independence (McEwen and Murphy, 2022).

Under the above conditions, a person who strongly held European and Scottish identities could imagine that each identity helps the other; identifying with Europe helped to meet the standard for the Scottish identity, and vice versa, making it more likely that they would support independence. A person with weak Scottish and European identities would have even less reason to care about independence, which aligned with neither of their identities. This pattern of expectations is consistent with complementarity.

Conversely, the above conditions suggest that a person with strongly held European and British identities would likely find themself to be internally conflicted. Britishness sets the standard of rejecting Scottish independence to preserve the Union. However, Europeanness would be consistent with the desire to return to Europe, which could possibly be accomplished by backing Scottish independence. A person holding this mix of views could feel paralyzed and, thus, demobilized from independence movement involvement. This pattern of expectations is consistent with interference.

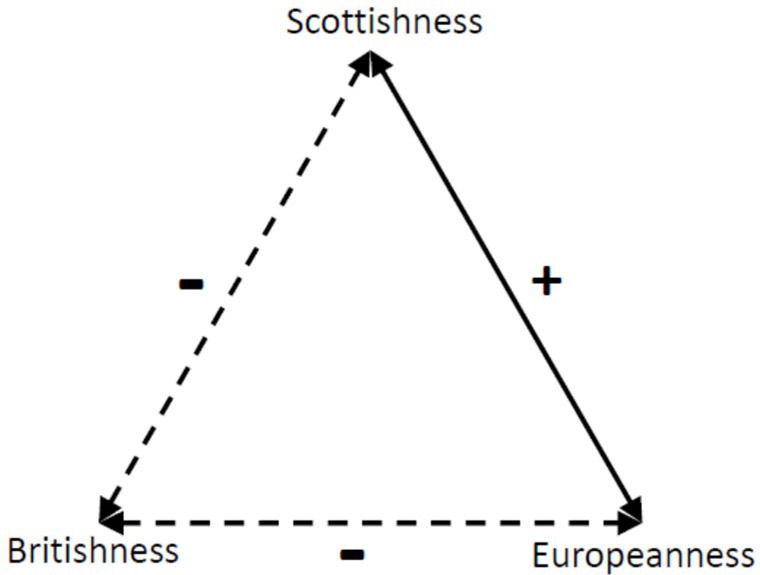

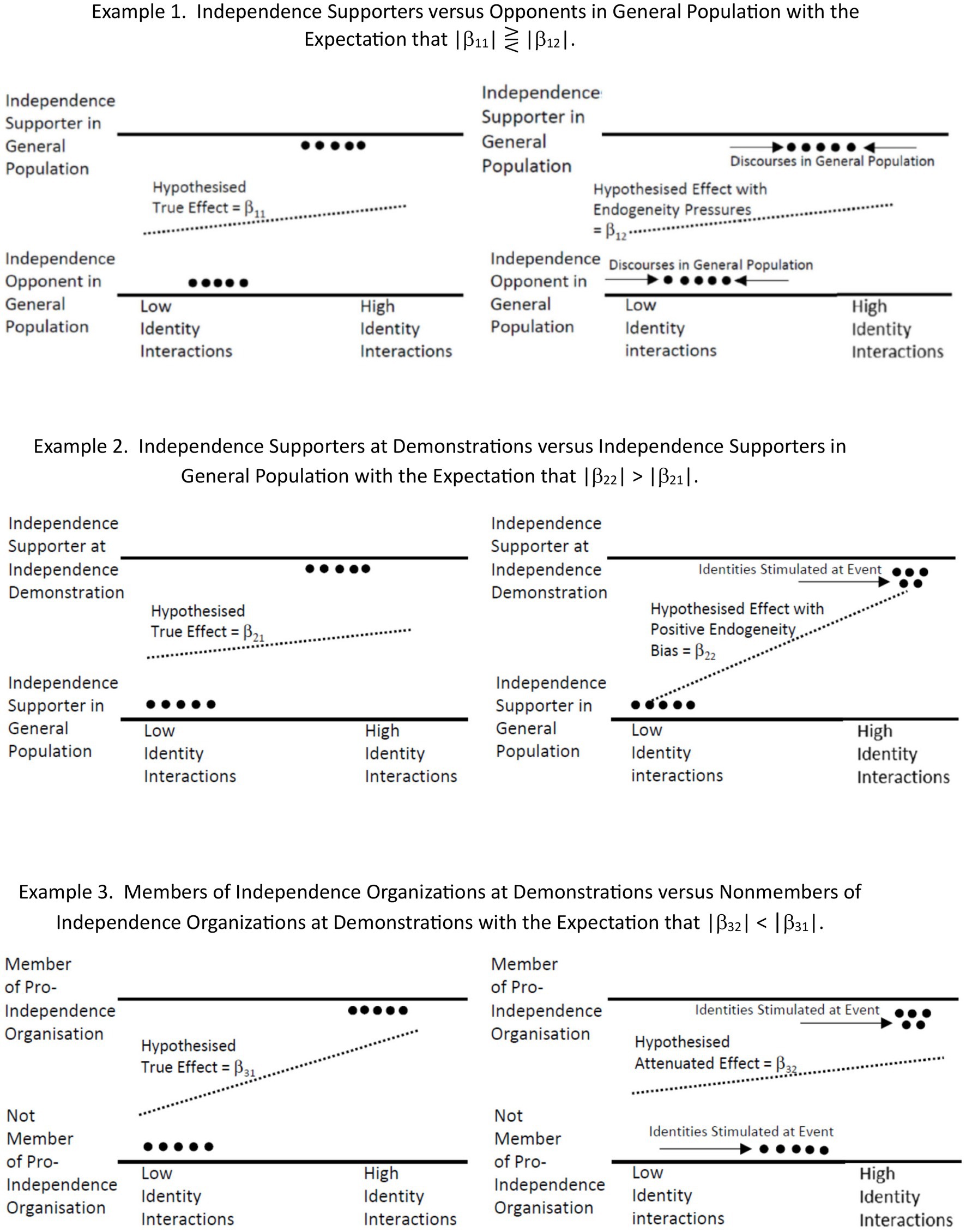

A summary of all anticipated interaction effects is presented in Figure 1, where a negative sign symbolizes expected interference and a positive sign symbolizes expected complementarity. These expectations do not imply that the relationship must hold for every person, only that they represent the overall configuration of relationships.

Although this article predicts the presence of interaction effects, it is important to remember that identities do not necessarily need to interact. The alternative hypothesis of a null effect is meaningful. For example, in the absence of Brexit, interactions between European identity and Scottish-British identities might have been inconsequential. Thus, the hypotheses articulated here are specific to the time and place of the study. We envision that identity interference and complementarity are general concepts that travel across time and space, but we recognize that the exact ways that they operate are fluid and contextually grounded.

Research design

Testing our hypotheses requires information on both supporters and non-supporters of Scottish independence. At the same time, it is valuable to have information not only about passive support for independence—the willingness to verbally state support—but also active support as actual participation in independence events and concrete contributions to nationalist organizations. These multiple types of data inform on nationalist mobilizations both in mass politics and social movements while also facilitating triangulation on effects that may be ambiguated by endogeneity. Thus, this study combines the use of publicly available data with original data on independence activism collected specifically for the project at hand.

First, the study accessed data available from the BES, which is conducted periodically for all of Great Britain (British Election Study, 2019). Conveniently, it contains a substantial sample from Scotland as well as questions about a possible future referendum on Scottish independence. These features, along with the fact that it coincided with a spike in pro-independence demonstrations in Scotland, as well as its long-established nature, make the BES a desirable source for our study. We used Wave 16 of the BES, conducted from May to June 2019, including responses from 2,068 randomly sampled residents of Scotland. Wave 16 of the BES had an overall retention rate of 65 percent of respondents who had previously participated in Wave 15 in March 2019.

Second, an original sample of active Scottish independence supporters was collected at all five major independence rallies held in Scotland on weekend days between August 17 and November 2, 2019. These surveys aimed to represent individuals who were active in the social movement aspects of the independence cause, thus enabling the research to examine grassroots politics in addition to mass politics. Given that there is no public register of social movement participants, surveys of this type are typically deployed to assess movement involvement. Surveys were collected in Aberdeen, Perth, Edinburgh, and Glasgow (two rallies) that were separately sponsored by three different organizations: All Under One Banner (three rallies), Hope Over Fear, and The National newspaper. The survey questions were drawn from the BES so that the two samples could be compared directly.

Respondents were selected from the crowd using the anchor-sampling counting technique developed by Heaney and Rojas (2015), consistent with prevailing standards for sampling protesters (Fisher et al., 2019). This technique involves distributing surveyors throughout the crowd with instructions on how to count and select potential respondents to approximate random selection. Estimates were made on the gender and race of non-respondents to construct survey weights. In total, 1,690 people were sampled at these events, 1,362 of whom agreed to take the survey, giving us an overall response rate of 81 percent. This rate is about typical of similar surveys conducted on-site at protests (Fisher et al., 2019).

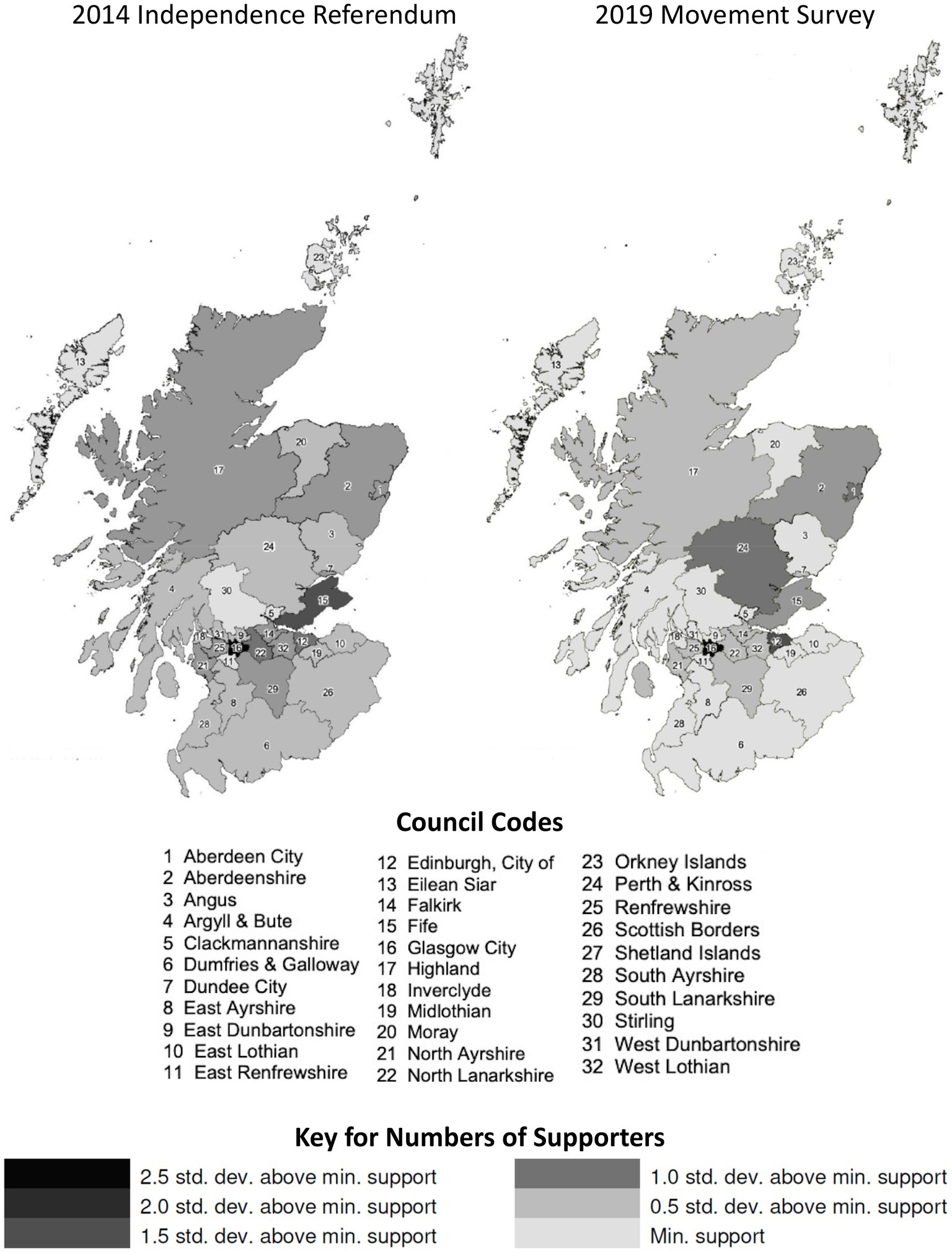

It is important to establish that the surveys conducted at the independence rallies fairly represent the people that gave active support to the independence movement. To do so, we mapped the people who voted for Scottish independence in 2014 (BBC, 2016) against the people who we surveyed at demonstrations in 2019, according to the council (i.e., geographic area) that they lived in. The results are reported in Figure 2. As the two maps have different dependent variables (number of votes versus number of demonstrators), we are not looking for an exact match between the levels in the two maps but, instead, the correlation between levels of support. We find a high correlation of 0.847, p ≤ 0.05. Thus, our street survey reasonably (though not perfectly) represents independence supporters in the general population on the dimension of residential location. This outcome reflects the willingness of supporters to travel to demonstrations as well as the relatively small size of Scotland.

Figure 2. Numbers of supporters for Scottish independence by council area. Maps are not adjusted for population but reflect raw numbers of supporters.

Statistical results

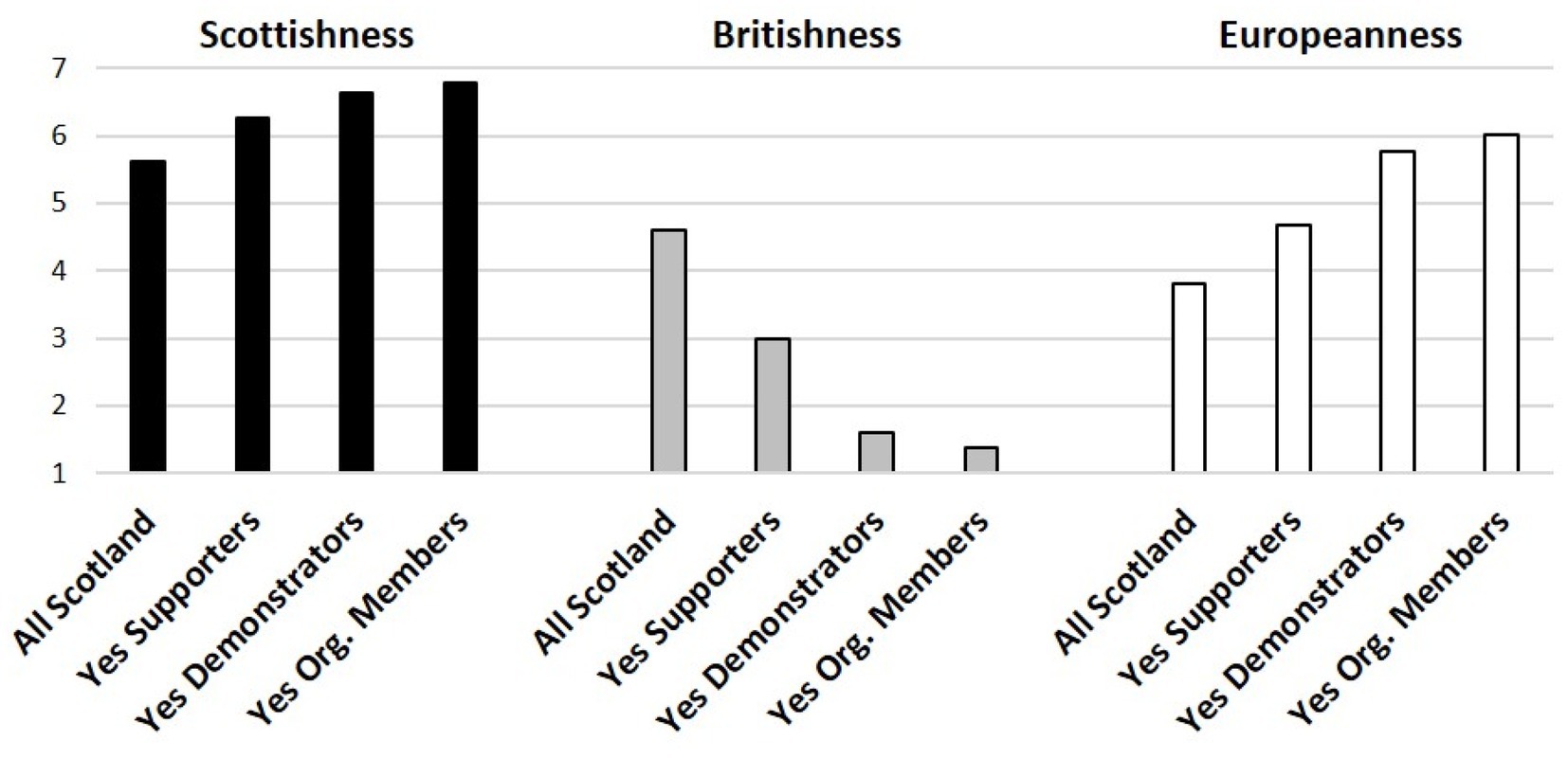

Descriptive statistics on identity and levels of nationalist mobilization in Scotland (reported in Figure 3) offer a simplified yet informative overview of their relationship. Respondents were presented with three identities: Britishness, Scottishness, and Europeanness. They were then asked “Where would you place yourself on these scales? 1 is low, 7 is high.” The results indicate that stronger Scottish identities were associated with higher levels of nationalist mobilization, thus pointing to an important relationship between identity strength and social movement involvement. British identities were stronger than European identities in Scotland overall. However, British identities diminished as increasing levels of nationalist mobilization were observed. Conversely, European identities were stronger as higher movement involvement was observed. Thus, among the most ardent supporters of independence, Scottish identities were strongest, followed by European and then British identities.

To test the hypotheses of the study, we estimated three sets of Probit models. Missing values were imputed using complete-case imputation, constrained to the range of possible values, which is an appropriate method when there is a low incidence of missing data (less than 20 percent) as was the case in this study (Little, 1988; King et al., 2001). Survey weights were applied to all models to adjust for differences between respondents and the relevant population reference group (all Scotland or all demonstrators).

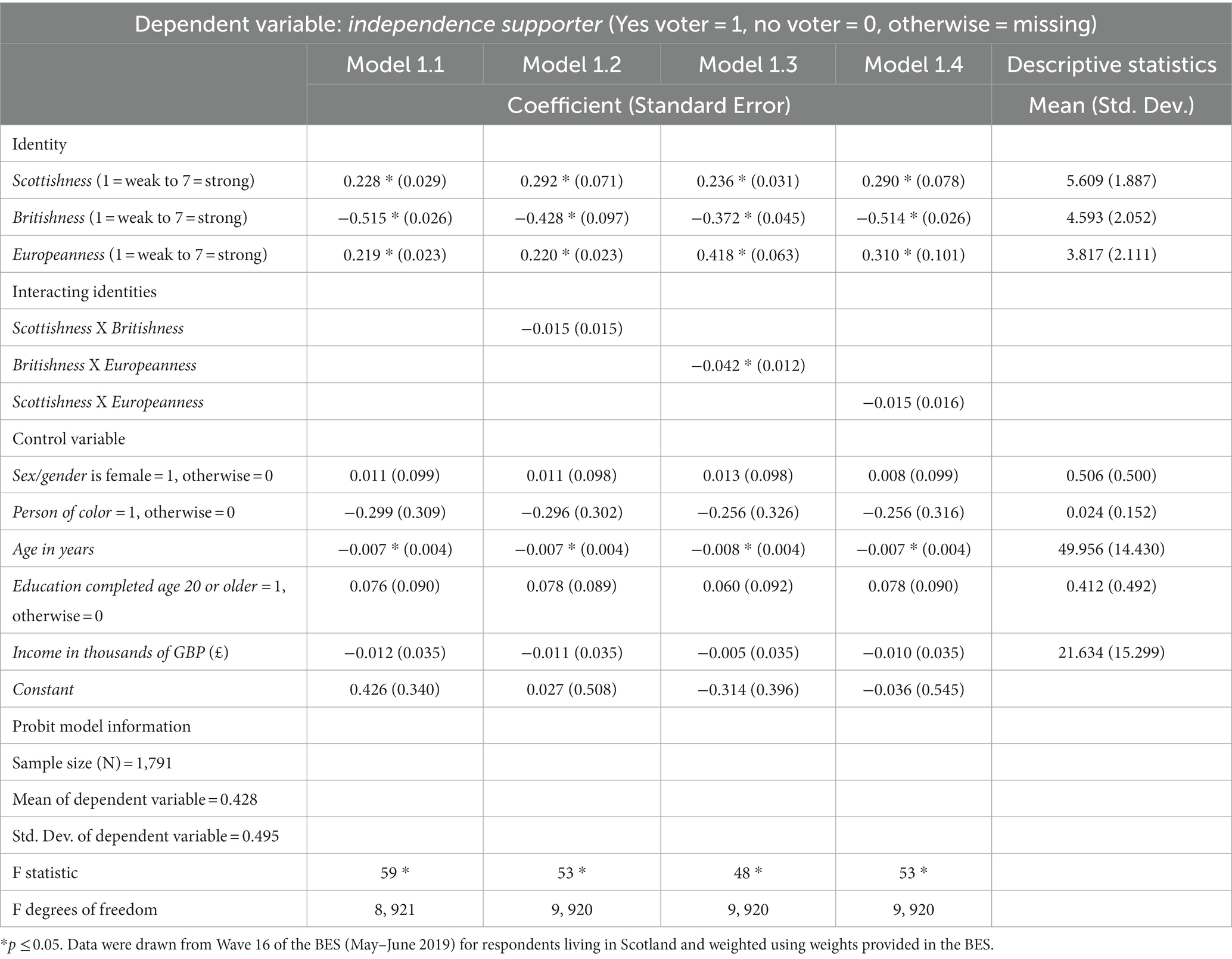

In Table 1, we report models in which the dependent variable takes the value of 1 if a BES respondent indicated support for independence and 0 if they indicated opposition to independence. These scores were based on the question “If there was another referendum on Scottish independence, how do you think that you would vote? Please circle one. [Options:] I would vote ‘Yes’ (leave the UK); I would vote ‘No’ (stay in the UK); Would not vote; Do not know.” Model 1.1 accounts for the direct effects of Scottish, British, and European identities, along with control variables for Sex/Gender, Person of Color, Age, Education, and Income using the pertinent questions from the BES. This model serves as a baseline because it did not include interaction effects.

The findings in Table 1 are unambiguous with respect to the direct effects of identity. In all four models, we observe statistically significant effects on all identity parameters. Scottish and European identities are both positively associated with support for independence among residents of Scotland, while British identities were negatively associated with such support. Among the control variables, age was negatively and significantly associated with support, revealing that younger people were more likely to embrace independence than were older people when other factors are held constant. The controls for sex/gender, race, education, and income do not reflect significant associations.

Models 1.2, 1.3, and 1.4 incorporate interaction effects. Each model included one interaction effect for a combination of Scottish, British, and European identities. We did not estimate models with three-way interactions (i.e., Scottish X British X European identities) because our theoretical approach does not yield clear hypotheses for such interactions. While these models are necessary to test the hypotheses, conclusions about interactions cannot be drawn directly from the table because interaction effects may change non-linearly throughout the sample space (Hainmueller et al., 2019). Instead, examining marginal effects substitutes for significance tests on the coefficients as a significant Probit coefficient is neither a necessary nor sufficient condition in making an inference about the significance of the interaction effects.

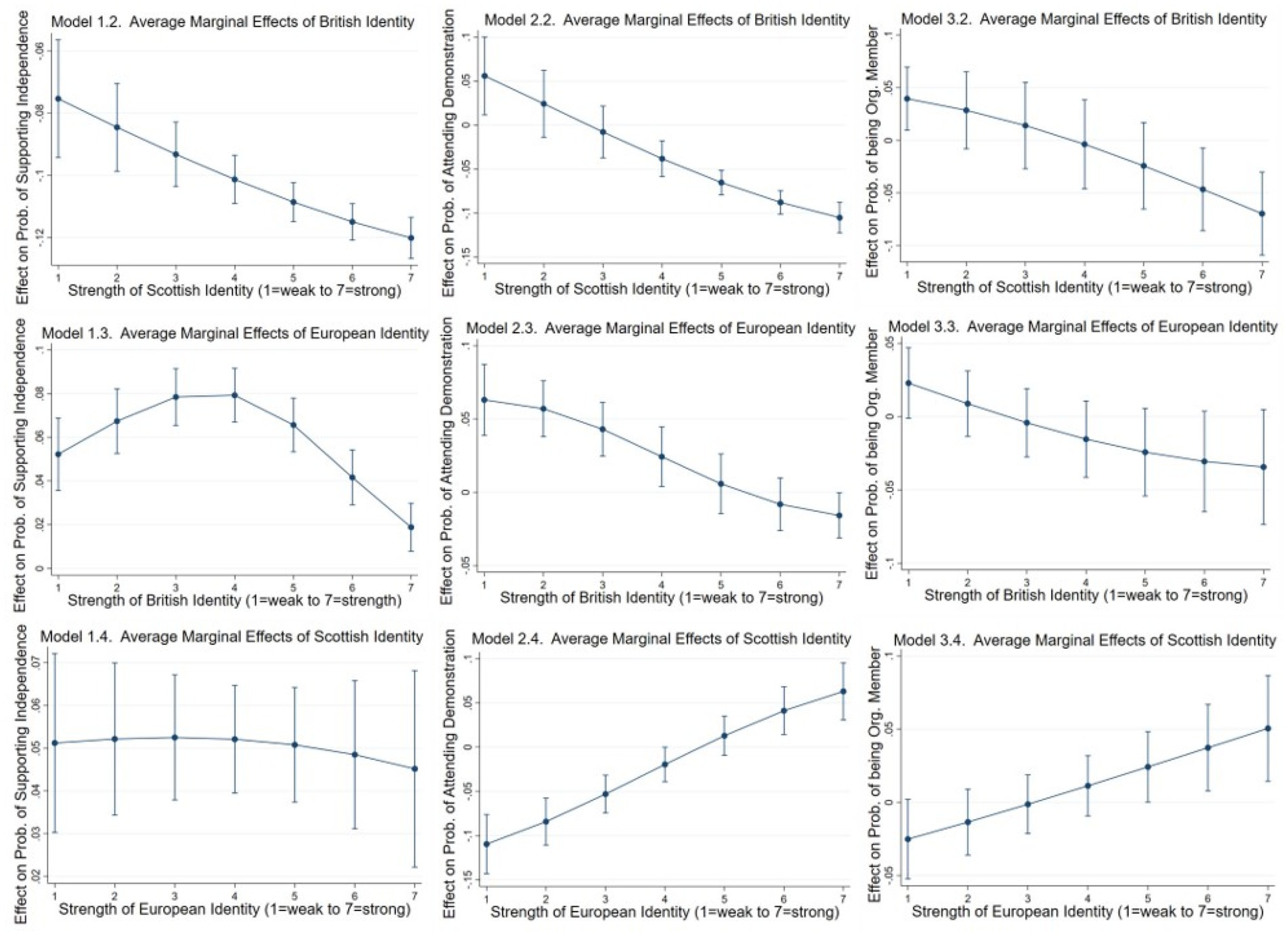

The marginal effects graphs reported in Figure 4 provide the information necessary to draw inferences about the hypotheses. The 95 percent confidence intervals plotted around the point estimates make it possible to extract these inferences directly from the graphs. The marginal effects graph associated with Model 1.2 presents compelling evidence that there is significant interference between Scottish and British identities in the general Scottish population. This result does not imply that Scottish and British identities are never complementary, only that there is a statistically significant amount of interference between them on the question of Scottish independence. The marginal effects graph associated with Model 1.3 appear to demonstrate a non-linear relationship between European and British identities. However, a careful reader will observe that the non-linearity is not statistically significant. Nonetheless, the non-linearity does complicate the interpretation of the result. There is significant interference between British and European identities when very high and very low British identities are compared. Finally, the graph associated with Model 1.4 is unambiguous that there is no significant interference or complementarity between Scottish and European identities regarding support for independence in the general population.

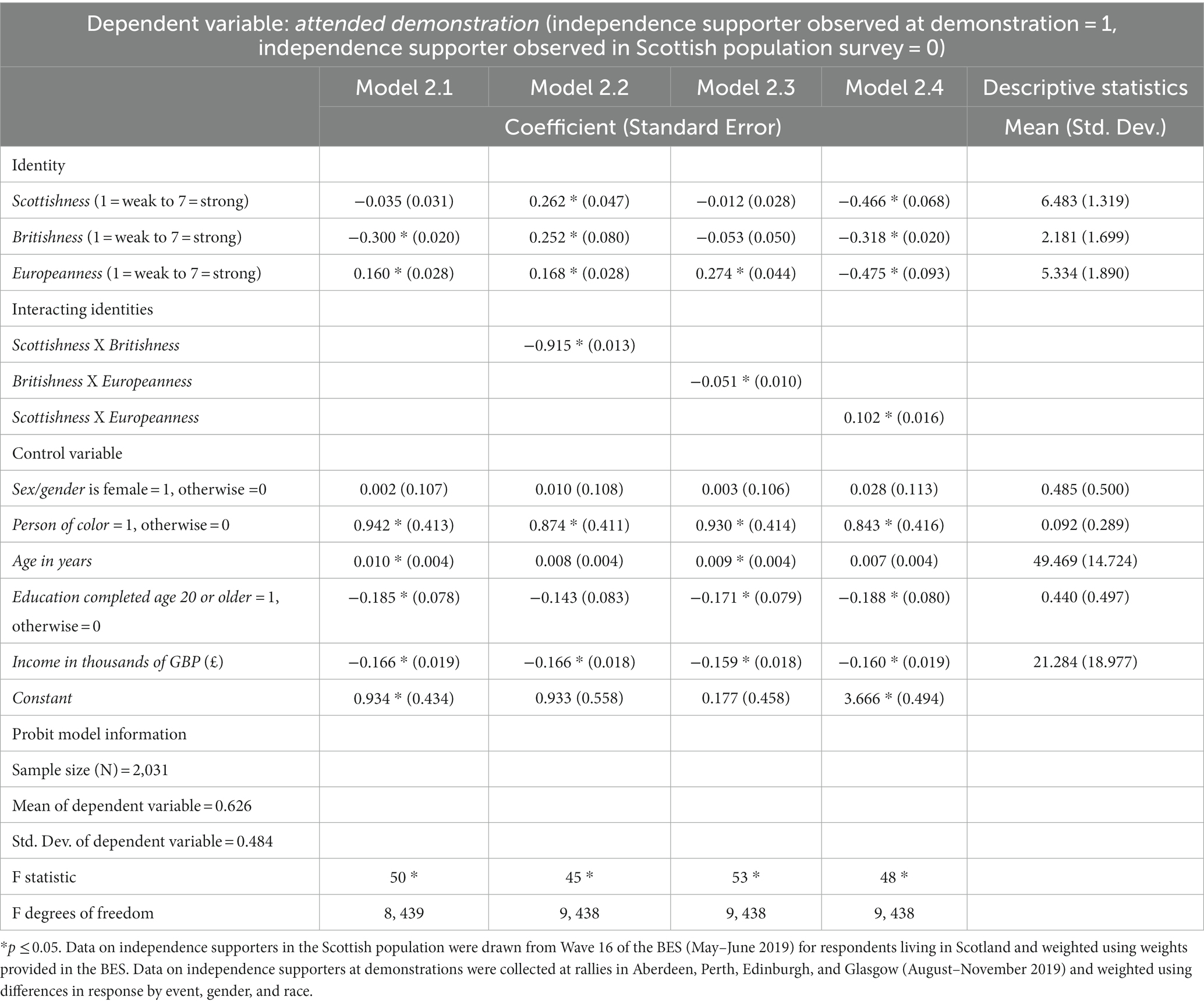

In Table 2, we report models in which the dependent variable takes the value of 1 if an independence supporter was observed at a demonstration and 0 if an independence supporter was observed in the BES. This approach reveals how independence supporters who were active in the movement at demonstrations differ from those who may have been less active in the movement. These models follow the same specification as the models reported in Table 1 with respect to independent variables. As we know that 100 percent of persons observed at rallies actually attended an independence rally, while only about 13 percent (British Election Study, 2019) of residents of Scotland who support independence had attended any kind of public demonstration in the past 12 months, these models differentiate between persons who attended rallies from those who likely only supported the movement at the ballot box.

The estimates of Model 2.1 are reported in Table 2. The direct effects of identity are not statistically significant in this model due to the relatively small difference between the strength of Scottish identities among marchers and pro-independence voters. Nevertheless, British (negative) and European (positive) identities maintain their significance as in Models 1.1 through 1.4 (above). Various demographic factors were significantly associated with active participation in demonstrations. People were more likely to march if they were a Person of Color as opposed to white and if they were older as opposed to younger. They were less likely to march if they completed more years of education and if they had higher levels of income. Sex/gender differences were not statistically significant.

To interpret the interaction effects in Models 2.2, 2.3, and 2.4, we return our attention to the graphs in Figure 4. Although the direct effects of Scottish identity are not significant in Model 2.1, the interaction effects between Scottish and British identities are unambiguously negative and significant. While this interference is true on average, the result does not mean that identities are not complementary for some people. Further, the models show identity interference between British and European identities; but they show identity complementarity between Scottish and European identities with respect to people turning out to demonstrations.

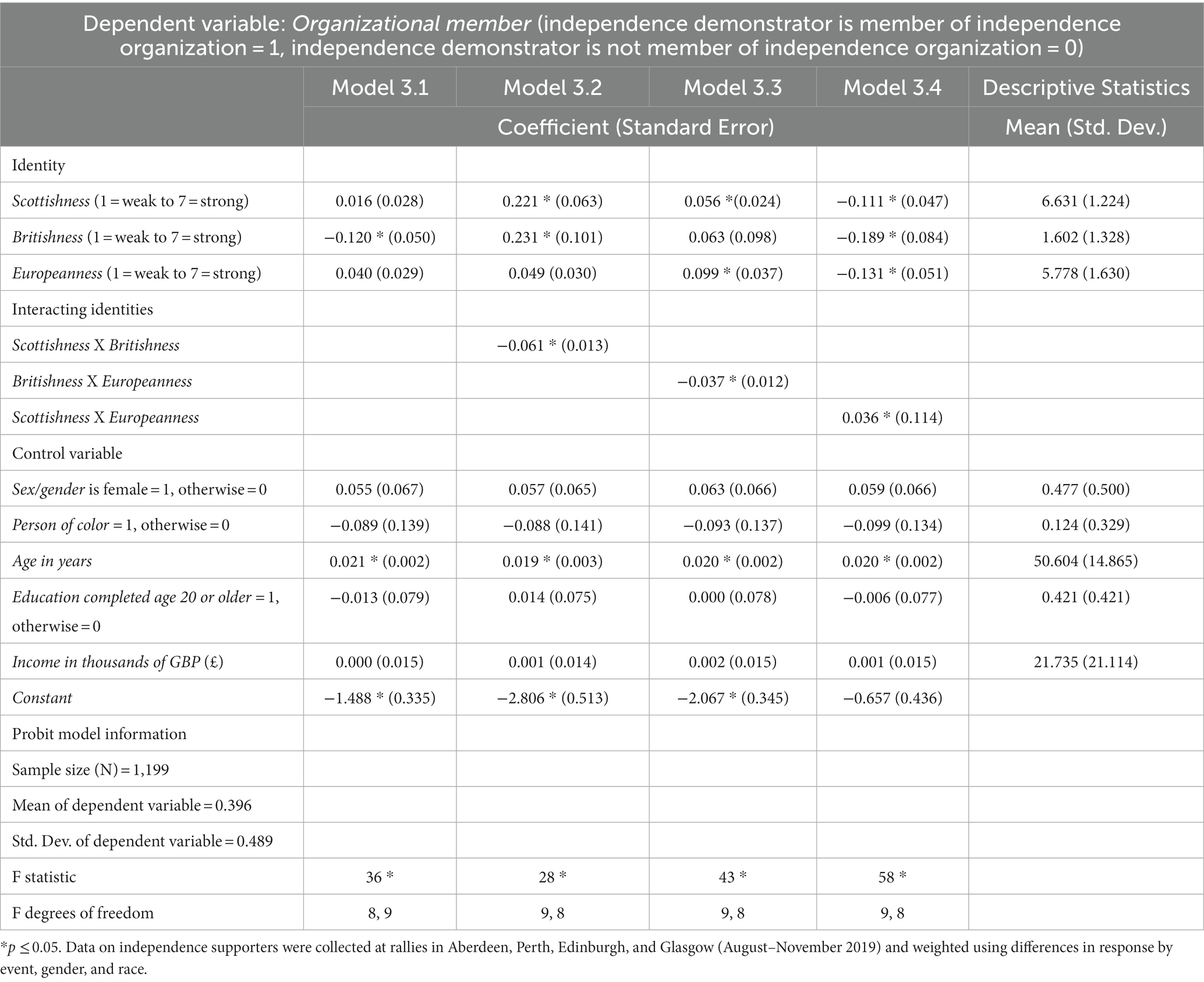

In Table 3, we report models in which the dependent variable takes the value of 1 if a participant in a demonstration is also a member of an independence organization and 0 if they are not a member of an independence organization. This measure is based on the question “Are you a member of any political organisations [sic.], social movement organisations [sic.], interest groups, or policy advocacy groups? Please circle one. [Options:] Yes, No. If yes, which ones?” (British spellings in original). Written responses were then coded by the study’s authors for whether they were an “independence organization” or not. Examples of such organizations include Women for Independence, Yes Stones, Bikers for Independence, and the SNP (see also Heaney, 2020). These models follow the same specification as those in Tables 1, 2 with respect to independent variables.

As was the case with Model 2.1, the results of Model 3.1 do not suggest a direct effect of Scottishness on predicting whether a demonstrator was also a member of an independence organization. Additionally, a direct effect of Europeanness is not detected in Model 3.1, though it is in Models 1.1 and 2.1. The reason for this variation is that there are only small differences between the Europeanness of demonstrators and people who are in pro-independence organizations. Among the control variables, only age holds predictive power in Model 3.1: Older demonstrators were more likely to also be members of pro-independence organizations than were younger demonstrators.

To interpret the interactions in Models 3.2 through 3.4, we return our attention to the graphs in Figure 4. The models suggest identity interference between British and Scottish identities as well as identity complementarity between Scottish and European identities. On the other hand, the results establish no relationship between British and European identities. While there is a negative pattern in the data, it misses the threshold for statistical significance as there is a slight overlap between the first and last confidence intervals in the graph.

In reviewing the full set of interactive effects, informative patterns emerge. First, there is evidence of interference between Scottish and British identities in every model that is quite separate from whether direct effects of identity are present or absent. In some ways, this result is not surprising in the sense that the independence movement is fundamentally about breaking the relationship between Scottish and British identities. If there were not interference between these identities, we might suspect that something was wrong with our models. Thus, this result may be viewed as a validity test for the overall study. Nevertheless, this study is the first to establish statistically the significance of such interactions as prior studies have focused on the direct effects of identity in Scotland.

Second, we have less confidence in concluding that there is interference between British and European identities than we do regarding the interference between Scottish and British identities. It is true that there are significant interactions between British and European identities in Models 1.3 and 2.3. However, Model 1.3 exhibits a non-linearity that begs for more exploration. It could be that people with strong European identities and low levels of British identity do not have much of a stake in the UK, creating a complementarity at low levels of Britishness. Still, it would be wise to obtain more data before reaching a firm conclusion here.

Third, the analysis of Scottish-European interactions is surprising and interesting. Model 1.4 weighs in favor of no relationship between Scottish and European identities, with the marginal effects graphs approximating a flat line (i.e., no effect). Among the general population, it may be that people with strong European identities are less likely to have a deep emotional connection to Scotland and, therefore, do not experience significant interactions between the two identities. On the other hand, Models 2.4 and 3.4 of pro-independence supporters both reveal complementarity between Scottish and European identities. These results were obtained in the presence of movement mobilization and activism. Thus, it is conceivable that direct contact with the movement is connected with the emergence of identity interactions.

Potential endogenous effects

The results of this study provide substantial evidence of statistically significant associations between interacting identities and degrees of support for nationalism in Scotland. The question naturally arises as to the direction of this association. Do interacting identities cause support for nationalism? Or does support for nationalism cause identities to interact? Does causality flow in both directions?

The statistical models in this article assume that identity interactions affect support for nationalism. This is the assumption of exogeneity in linear models. Yet, there are good reasons to believe that the opposite assumption (i.e., endogeneity) may also have some validity. For example, a person who participates in a nationalist mobilization may learn through that experience about how identities are or ought to be interrelated. If a speaker at a street demonstration talks about why people in Scotland should be committed to the European Union, listening to that speech could lead someone attending to think more about their European identity—possibly prompting an interaction. If so, then an endogenous effect could be present. At the same time, it is also plausible that the same rally participant attends the event and listens to the speaker only because they already agree with or sympathize with the pro-European position. If that were the case, then the exogeneity assumption would still be reasonable. Recent research by Johns (unpublished, see footnote 1) suggests that the endogenous effects of mobilization on identity are small in magnitude and seemingly short-lived, though this research was reported in a preliminary stage, with further investigation required.

There may be no definitive way of resolving these types of endogeneity problems in observational research. However, the present study was designed with these issues in mind such that the data may afford some leverage on the endogeneity question. The three dependent variables that measure nationalist mobilization are plausibly vulnerable to endogeneity effects to different degrees and in opposing directions. If we assume that the endogenous effects in question are least when the contact between the movement and the individuals is minimal, then it may be possible to construct bounds around the magnitude of endogenous effects. Manski (1995) proposed this approach as a way to facilitate the identification of empirical models in the presence of endogeneity.

Consider the models presented in Figure 5. Example 1 illustrates the case of people in the general public who encounter the independence movement. Those encounters could influence identity interactions. However, it is also possible for those people (or other people) to encounter the pro-Union (anti-independence) movement and its arguments. If so, pro-Union contacts could influence identity interactions in the opposite direction. If the pressures from these contacts were roughly equal, then there would be no expected bias in the estimated regression coefficient of interest. Or, if there was a bias, it would be in proportion to the imbalance of independence versus pro-Union discourses.

Example 2 illustrates the case in which people who vocalize support for independence are compared to people who also attend pro-independence street demonstrations. If we assume people attending demonstrations are more likely to be exposed to arguments prompting identity interactions than people not attending them, then there is the potential for a positive bias in the estimated regression coefficient of interest.

Example 3 illustrates the case in which non-members of independence organizations attending a street demonstration are compared to members of independence organizations also attending demonstrations. If we assume that people who are members of independence organizations have already had high exposure to arguments that would prompt identity interactions, then there would be more opportunity for the non-members of organizations to receive new exposure. If the non-members shift more than the members, then the result would be the attenuation of the regression coefficient of interest, suggesting a negative bias.

This analysis implies that the interaction coefficients in the first regressions would have biases tending toward zero. Coefficients in the second regressions would manifest positive biases. Finally, coefficients in the third regressions would exhibit negative biases. Adopting this perspective would allow the second regressions to be viewed as an upper bound on the interaction coefficient, the third regression as a lower bound, and the first regression as a possible middle effect.

The models in Figure 5 are a lens for comparing the nine interaction effects reported in Figure 4. The first row of results (Models 1.2, 2.2, and 3.2) presents an unambiguous negative interaction that establishes interference (on average, but not necessarily for all people) between Scottish and British identities in all three cases. At the upper bound, the lower bound, and the middle, the effect is estimated to be negative. The second row of results (Models 1.3, 2.3, and 3.3) is more problematic. Upper-bound effects imply complementarity, though the suggested lower bound misses the threshold for statistical significance. The possible middle effect may be non-linear, though it confidently reveals interference at the highest level of British identity. The third row of results (Models 1.4, 2.4, and 3.4) shows clear complementarity at both the upper bound and the lower bound. However, the possible mean effect (in the general population) is non-significant.

The insights gleaned from this approach provide some clarity, though they leave other questions unanswered. First, the evidence strongly suggests interference between Scottish and British identities matters to nationalist mobilization even if endogeneity effects are consequential for these models. That is as close to ruling out an endogeneity problem as is possible in this study. Second, complementarity between European and Scottish identities is clear for people who support independence even if endogeneity effects are consequential for these models. However, it is improbable that such interactions mattered in the general population. Third, some evidence supports interference between European and British identities, though the results are mixed. If there are endogeneity effects here, they could be obscuring our ability to assess interaction effects.

Implications and future research

The results of this study are consistent with prior research that establishes direct associations from national identities to support for nationalist causes (such as independence) and the social movements that aspire to advance them. It may not be surprising that we find that stronger Scottish and European identities often align with greater support for Scottish independence, while stronger British identities align with pro-Union or anti-independence positions. Instead, the clearest contribution of the study comes from its evidence about interactions among these identities.

Thinking only (or primarily) about the direct effects of national identities—as is standard in the extant literature—is misleading because doing so tends to conceptualize identity as a fixed, static component in politics. This perspective treats the potential effects of identities as additive. However, interaction effects present multiplicative possibilities. In our study, complementarity between Scottish and European identities means that they amplify one another in mobilizing support. As the strength of European identities went up (or down), the effect of Scottish identities went up (or down) even more. If someone identifies resolutely as both Scottish and European, their European identification tends to augment the impact of Scottish identification, and vice versa. Interference between British and European identities means that the solidification of a European identity has both a direct and indirect effect on mobilization by diminishing the relevance of Britishness.

Interaction effects illuminate the relevance of context for the impact of identities. The study at hand examined independence mobilizations in 2019 subsequent to a highly controversial referendum in which the UK as a whole overrode Scottish preferences on Brexit. In this instance, events served to link Scottish and European identities as leaving the European Union also meant suppressing Scotland’s autonomy. The copresence of Scottish and European identities is a critical part of the story. This milieu plausibly augmented interaction effects between the identities. Alternatively, it is easy to imagine counterfactuals and their consequences. If the final UK Brexit vote had aligned with (as opposed to against) Scotland’s vote—or if there had never been a Brexit referendum, it is hard to envision that independence mobilization in Scotland would have been as robust in 2019 as it actually was. This view posits that mobilization is not just dependent on isolated identities but on the configuration of identities in a situation.

Throughout this article, we have been careful not to overgeneralize our findings. Interference or complementarity does not necessarily apply to every single person in Scotland. There is no reason to doubt that many people are able to reconcile their attachments to Britain and Scotland with the push by many of their fellow Scots for independence. Their identities may be genuinely dual in nature without fomenting conflict. Or, perhaps, interference is present when people are primed with questions about independence but is absent when different issues are on the table (such as teachers’ contracts or funding the National Health Service). Similarly, some Scots may embrace Europe without affecting their thinking about independence. Their identities may be fundamentally unrelated to one another. Or, perhaps, complementarity is embedded in conversations about independence but not in concerns about Europe’s intervention in the war between Ukraine and Russia. Nevertheless, this study evinces that interference and complementarity are statistically significant tendencies in the data with respect to Scottish independence—patterns that hold at multiple levels of mobilization.

While it is possible for interference or complementarity to manifest between any pair of identities, it is also critical to highlight the distinctiveness of the configuration of identities in this particular study. Notably, it investigates the interface between two national identities and a supranational identity. While it may be intuitive to assume that the solidification of a supranational identity impinges on the national identities below it, this research instead reveals positive feedback between Scottish and European identities. Thus, the salience of a supranational identity counterintuitively enhanced the effect of a national identity. Scottish identities mattered more when they were coupled with strong European identities. If this pattern generalizes to other countries, it could prompt unexpected dynamics in their national politics.

The analysis in this article hints at several possibilities for future research. First, this study displays the benefits of examining identities in Scotland along three dimensions (Scottish, British, and European) rather than principally on a single dimension of Scottish to British. It is conceivable that future research could unpack the dimensionality of these identities even further, perhaps probing different ways of identifying with a nation. For example, some scholars have sought to differentiate between “civic” and “ethnic” nationalism, though the boundaries between them may be blurred and fraught with contradictions (Tamir, 2019). Lessons could also be drawn from scholarship that dissects the dimensionality of regional identities—such as distinguishing between parochialism, inclusive regionalism, and pseudo-exclusive regionalism (Brigevich, 2018)—in order to imagine further variation in national identities. Regardless of the specific choices made by scholars about the forms of nationalism, the idea of decomposing the elements of national identity to better understand interactions seems promising.

Second, this study raises the question of how European identities are likely to matter for the politics of Scotland and the UK more generally. It pinpoints the power of Europeanness for 2019. The extent to which that power pervades over time is an empirical question. Will Scottishness and Europeanness continue to co-evolve together or have they passed a peak? It is possible that the European identity continues to fuel Scottish nationalism. Conversely, it is conceivable that the European identity fades in salience as Brexit drifts into the rearview mirror. Which of these patterns eventually manifests is likely to be influential in the power exerted in future rounds of mobilization for Scottish independence. Related questions could be asked about Irish, British, and European identities as the prospects rise for a border poll on Northern Ireland (Garry et al., 2021). For example, is it possible for common European identities to serve as a bridge to unify Irish identities between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland? Research of this ilk would be well positioned to build on and add to the findings of studies that have examined the degree of compatibility of European identities in other nations (Brigevich, 2012).

Third, this study points to opportunities for filling the lacuna on social movements in Scotland. The present article, as well as studies such as McKeever’s (2021) analysis of parties, movements, and brokers for Scottish independence and Moreau’s (2023) fieldwork on the Conference on the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow, helps to address this gap. Yet these recent developments only scratch the surface of the vibrant social movement sector in Scotland. Edinburgh and Glasgow, which are the largest cities in Scotland, are also hubs for recurrent protests for a variety of causes. On the political right, the anti-Catholic Orange Order and the anti-vaccine Scottish Vaccine Injury Group have been regularly active. On the political left, myriad groups routinely gather to promote Palestinian rights, socialism, labor unions, racial justice, solutions to the climate emergency, and many other causes. The colocation of these opposing groups is known to spark intense counterprotests and sporadic violence (Patterson, 2023). These urban environments are veritable melting pots of movements and identities, which likely stimulate extensive cross-fertilization and hybridization (Heaney and Rojas, 2014). Research on activism in this environment could inform how a broader range of identities interact and the consequences for intersecting movements and their intersecting causes.

Fourth, future research could consider whether the interactions present in Scotland are a factor in other places that encounter clashing nationalisms, such as Ukraine, Russia, Hong Kong, Quebec, Puerto Rico, and Catalonia. For example, do the prospects for the Québécois identity rise and fall along with confidence in the Canadian identity? Given that identities are held in people’s minds, new interactions could be introduced by generational changes that are not anticipated by political leaders.

Fifth, to what extent do supranational identities extend beyond Europe? The European identity is a prominent example of a supranational identity but is certainly not the only possible instantiation of this idea. For example, as China rises as a power in Asia, the viability of pro- or counter-Chinese supranational identities could result from aspirations to unite other Asian nations (Mearsheimer, 2014, pp. 388–392). The insight offered by this article is that dynamics underlying these supranational projects depend not only on the actions of the elites of the great powers but also on the ways ordinary people identify themselves and the events that shape their era (see also Wendt, 1999, pp. 327–333).

Sixth, do the implications of this article extend beyond national identities and nationalist mobilization to other social movements that depend on multiple and interacting identities of myriad types? The growing literature that connects the intersectionality of race, gender, and other dimensions of difference especially calls for more research on how interactions among identities are consequential for mobilization (Roberts and Jesudason, 2013; Terriquez et al., 2018; Heaney, 2021). For example, the interaction between identities relating to race and gender has been extensively explored (for a review, see Hancock, 2016). Yet, the complex relationship of class identities with race and gender is less well understood. Could non-linear patterns of interaction be present where interference or complementarity works differently as income and wealth progress from the lower tiers to higher tiers? Is it possible that LGBTQIA+ identities exhibit complementarities with race or gender at some levels of wealth and income but interference at other levels? The present article should prompt scholars to compare the effects of interactions across multiple levels of analysis and varied forms of identity. These interactions are at the heart of intersectionality and related instantiations of movement politics.

In conclusion, this article illustrates the benefits of extending the range of identities investigated in social science research. It is important to look at multiple identities not only because these identities have separate effects on actors but also because the identities may affect each other. While there is undoubtedly a limit to the number of identities that bear upon any particular research question, that limit is likely well above what is typically considered in empirical studies of identity. Studies that explore only one or two identities potentially bypass unexpected, complex interactions that may arise from other loyalties of leading actors. Thus, further research should aspire to harvest more evidence on salient identities that may be linked to nationality, race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, class, ideology, profession, party, ability or disability, language, and other dimensions of difference.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Social Sciences Ethics Board, University of Glasgow. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EA: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MC: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. GM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. All funding for this research was provided by the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Glasgow.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for helpful suggestions from six reviewers, Joost Berkhout, Andrew Bertoli, Chris Carman, Jane Duckett, Rob Franzese, Steve Garcia, Marc Guinjoan, Rob Johns, Bert Klandermans, Suzanne Luft, Thomas Lundberg, Dave McKeever, Fraser McMillan, David Meyer, Anja Neundorf, Sergi Pardos-Prado, Bernhard Reinsberg, Arieke Rijken, Toni Rodon, Patrícia Silva, Jacquelien van Stekelenburg, Mark Tranmer, Katerina Vrablikova, Karen Wright, the Comparative Politics Cluster at the University of Glasgow, the Social Change and Conflict (SCC) Group at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, a seminar in Politics and International Relations at the University of Essex, and the European Consortium on Political Research (ECPR) workshop on “Whither Identity? National Identity and Political Behavior [sic.].” Surveys were administered at demonstrations by Erika Anderson, Yang Ben, Madilyn Cancro, Rebecca Gebauer, Michael Heaney, Cameron Herbert, Angeline MacDonald, Salwa Malik, Grace Martin, Tracy McKenzie, Leila Le Mercier, Harry McClean, Maarya Omar, Caitlin Ryan, Roisin Spragg, and Miriam Thangaraj.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anderson, Benedict . (1983). Imagined communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso.

Bayram, A. B. (2019). Nationalist cosmopolitanism: the psychology of cosmopolitanism, national identity, and going to war for the country. Nations Natl. 25, 757–781. doi: 10.1111/nana.12476

BBC (2016). EU Referendum Results. Available at:https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/politics/eu_referendum/results (Accessed January 19, 2020).

Bieber, F. (2022). Global nationalism in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Natl. Papers 50, 13–25. doi: 10.1017/nps.2020.35

Bond, R. (2006). Belonging and becoming: national identity and exclusion. Sociology 40, 609–626. doi: 10.1177/0038038506065149

Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: on being the same and different at the same time. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 17, 475–482. doi: 10.1177/0146167291175001

Brewer, M. B. (1999). Multiple identities and identity transition: implications for Hong Kong. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 23, 187–197. doi: 10.1016/S0147-1767(98)00034-0

Brigevich, A. (2012). Peeling back the layers: territorial identity and EU support in Spain. Reg. Fed. Stud. 22, 205–230. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2012.668136

Brigevich, A. (2018). Regional identity and support for integration: an EU-wide comparison of parochialists, inclusive regionalist, and pseudo-exclusivists. Eur. Union Polit. 19, 639–662. doi: 10.1177/1465116518793708

British Election Study (2019). Available at:https://www.britishelectionstudy.com/ (Accessed December 1, 2019).

Cederman, L.-E. (1995). Competing identities: an ecological model of nationality formation. Eur. J. Int. Rel. 1, 331–365. doi: 10.1177/1354066195001003002

Curtis, John, and Montagu, Ian. (2018). How Brexit has created a new divide in the nationalist movement. British Social Attitudes. Available at:https://bsa.natcen.ac.uk/latest-report/british-social-attitudes-35/scotland.aspx (Accessed August 21, 2023).

Eras, L. (2023). War, identity politics, and attitudes toward a linguistic minority: prejudice against Russian-speaking Ukrainians in Ukraine between 1995 and 2018. Natl. Papers 51, 114–135. doi: 10.1017/nps.2021.100

Fisher, D. R., Andrews, K. T., Caren, N., Chenoweth, E., Heaney, M. T., Tommy Leung, L., et al. (2019). The science of contemporary street protest: new efforts in the United States. Sci. Adv. 5:eaaw5461. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw5461

Garry, J., O’Leary, B., McNicholl, K., and Pow, J. (2021). The future of Northern Ireland: border anxieties and support for Irish reunification under varieties of UKexit. Reg. Stud. 55, 1517–1527. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2020.1759796

Hainmueller, J., Mummolo, J., and Yiqing, X. (2019). How much should we trust estimates from multiplicative interaction models? Simple tools to improve empirical practice. Polit. Anal. 27, 163–192. doi: 10.1017/pan.2018.46

Hancock, Ange-Marie . (2016). Intersectionality: an intellectual history. New York: Oxford University Press.

Heaney, M. T. (2020). The contentious politics of Scottish independence. Polit. Insight 11, 20–23. doi: 10.1177/2041905820978838

Heaney, M. T. (2021). Intersectionality at the grassroots. Polit. Groups Ident. 9, 608–628. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2019.1629318

Heaney, M. T., and Rojas, F. (2014). Hybrid activism: social movement mobilization in a multimovement environment. Am. J. Sociol. 119, 1047–1103. doi: 10.1086/674897

Heaney, Michael T., and Rojas, Fabio. (2015). Party in the street: the antiwar movement and the Democratic Party after 9/11. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Henderson, A., Jeffrey, C., and Liñeira, R. (2015). National identity or national interest? Scottish, English and Welsh attitudes to the constitutional debate. Polit. Q. 86, 265–274. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12163

Henderson, Ailsa, Johns, Robert, Larner, Jac M., and Carman, Christopher J. (2022). The referendum that changed a nation Scottish voting behaviour 2014–2019. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave MacMillian.

hooks, b . (1984) [sic.]. Feminist theory: from margin to center. Boston, MA: South End Press. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell_hooks

Kang, J. W. (2008). The dual national identity of the Korean minority in China: the politics of nation and race and the imagination of ethnicity. Stud. Ethn. Natl. 8, 101–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9469.2008.00005.x

Karelaia, N., and Guillén, L. (2014). Me, a woman, and a leader: positive social identity and identity conflict. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 125, 204–219. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.08.002

Keating, Michael , Ed. (2020). The Oxford handbook of Scottish politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

King, C. (2012). The Scottish play: Edinburgh’s quest for independence and the future of separatism. Foreign Aff. 91, 113–124.

King, G., Honaker, J., Joseph, A., and Scheve, K. (2001). Analyzing incomplete political science data: an alternative algorithm for multiple imputation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 95, 49–69. doi: 10.1017/S0003055401000235

Klandermans, P. G. (2014). Identity politics and politicized identities: identity processes and the dynamics of protest. Polit. Psychol. 35, 1–22. doi: 10.1111/pops.12167

Lacroix, J.-G. (1996). The reproduction of Quebec national identity in the post-referendum context. Scottish Affairs 17, 62–77. doi: 10.3366/scot.1996.0055

LexisNexis (2022). Lexis Uni. Available at:https://www.lexisnexis.co.uk/products/nexis-uni.html

Manski, Charles . (1995). Identification problems in the social sciences. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Martinovic, B., and Verkuyten, M. (2014). The political downside of dual identity: group identifications and religious political mobilization of Muslim minorities. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 53, 711–730. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12065

McCrone, D. (2017). Explaining Brexit north and south of the border. Scottish Affairs 26, 391–410. doi: 10.3366/scot.2017.0207

McCrone, D. (2019). Who’s European? Scotland and England compared. Polit. Q. 90, 515–524. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12702

McCrone, D. (2020). “Nationality and national identity” in The Oxford handbook of Scottish politics. ed. M. Keating (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 23–41.

McCrone, David, and Bechhofer, Frank. (2015). Understanding national identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McEwen, N., and Murphy, M. C. (2022). Brexit and the union: territorial voice, exit and re-entry strategies in Scotland and Northern Ireland after EU exit. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 43, 374–389. doi: 10.1177/0192512121990543

McInnes, Roderick, Ayres, Steven, and Hawkins, Oliver. (2014). Scottish independence referendum 2014: analysis of results. Westminster: House of Commons Library. Research Paper 14/50.

McKeever, D. (2021). Parties, movements, brokers: the Scottish independence movement. Contention Multidiscip. J. Soc. Protest 9, 1–30. doi: 10.3167/cont.2021.090102

Mearsheimer, John J. (2014). The tragedy of great power politics, Updated Edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Merino, J. A. (2020). The rise of independence feelings in Catalonia and Scotland. A longitudinal study on the profile of independence in the beginning of the 21st century. Przegląd Narodowościowy / Review of Nationalities 10, 57–75. doi: 10.2478/pn-2020-0005

Moreau, M. (2023). COP26 protests in Glasgow: encountering crowds and the city. Scottish Geogr. J. 139, 56–72. doi: 10.1080/14702541.2022.2161008

Moreno, L. (2006). Scotland, Catalonia, Europeanization and the ‘Moreno question’. Scottish Affairs 54, 1–21. doi: 10.3366/scot.2006.0002

Moreno, L., and Arriba, A. (1996). Dual identity in autonomous Catalonia. Scottish Affairs 17, 78–97. doi: 10.3366/scot.1996.0056

Morisi, D. (2018). When campaigns can backfire: national identities and support for parties in the 2015 U.K. general election in Scotland. Polit. Res. Q. 71, 895–909. doi: 10.1177/1065912918771529

Mylonas, Harris, and Tudor, Maya. (2023). Varieties of nationalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nagar, R. (1997). Communal places and the politics of multiple identities: the case of Tanzanian Asians. Ecumene 4, 3–26. doi: 10.1177/147447409700400102

Pattie, C., and Johnston, R. (2017). Sticking to the union? Nationalism, inequality and political disaffection and the geography of Scotland’s 2014 independence referendum. Reg. Federal Stud. 27, 83–96. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2016.1251907

Reeskens, T., and Wright, M. (2013). Nationalism and the cohesive society: a multilevel analysis of the interplay among diversity, national identity, and social capital across 27 European societies. Comp. Pol. Stud. 46, 153–181. doi: 10.1177/0010414012453033

Roberts, D., and Jesudason, S. (2013). Movement intersectionality. Du Bois Review 10, 313–328. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X13000210

Settles, I. (2004). When multiple identities interfere: the role of identity centrality. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 30, 487–500. doi: 10.1177/0146167203261885

Settles, I. (2006). Use of an intersectional framework to understand black women’s racial and gender identities. Sex Roles 54, 589–601. doi: 10.1007/s11199-006-9029-8

Settles, I., Jellison, W. A., and Pratt-Hyatt, J. S. (2009). Identification with multiple social groups: the moderating role of identity change over time among women-scientists. J. Res. Pers. 43, 856–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.04.005

Simon, B., and Grabow, O. (2010). The politicization of migrants: further evidence that politicized collective identity is a dual identity. Polit. Psychol. 31, 717–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00782.x

Smithson, M., Sopeña, A., and Platow, M. J. (2015). When is group membership zero-sum? Effects of ethnicity, threat, and social identity on dual national identity. PLoS One 10:e0130539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130539

Tajfel, Henri . (1981). Human groups & social categories: studies in social psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tamir, Y. (2019). Not so civic: is there a difference between ethnic and civic nationalism? Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 419–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-022018-024059

Terriquez, V., Brenes, T., and Lopez, A. (2018). Intersectionality as a multipurpose collective action frame: the case of the undocumented youth movement. Ethnicities 18, 260–276. doi: 10.1177/1468796817752558

Torrance, David . (2020). ‘Standing up for Scotland’: Nationalist unionism and Scottish party politics, 1884–2014. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Usherwood, S. (2019). Getting Brexit done, or getting Brexit done right? Polit. Insight 10, 32–34. doi: 10.1177/2041905819891372

Wendt, Alexander . (1999). Social theory of international politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Keywords: nationalism, national identity, social movements, interaction effects, independence, Scotland, United Kingdom, Europe

Citation: Heaney MT, Anderson EL, Cancro ME and Martin GE (2023) Interactions among national and supranational identities: mobilizing the independence movement in Scotland. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1281437. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1281437

Edited by:

Anna McKeever, University of the West of Scotland, United KingdomReviewed by:

Duncan Sim, University of the West of Scotland, United KingdomKirstein Rummery, University of Stirling, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2023 Heaney, Anderson, Cancro and Martin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michael T. Heaney, bWljaGFlbHRoZWFuZXlAZ21haWwuY29t

Michael T. Heaney

Michael T. Heaney Erika L. Anderson

Erika L. Anderson