- Department for E-Governance and Administration, University for Continuing Education Krems, Krems an der Donau, Austria

There is extensive literature on stakeholder theory and knowledge management in the private sector, but less on the public sector, particularly in the context of public participation projects. Public participation initiatives are often designed using a case-by-case approach to identify relevant stakeholder groups, the engagement methods, and the tools to be used. In addition, public sector organizations (PSOs) often rely on participation experts and practitioners' professional knowledge to design successful participation projects. Given that public participation is to enable PSOs access to participants' knowledge, knowledge management is a central issue in public participation projects. In this multi-method, qualitative study we focus on the management of experts' and practitioners' knowledge, and we aim to show how their knowledge contributes to participatory processes and projects, and how the policy cycle can be used as a knowledge management framework to collect and structure their knowledge. We used sequential analysis to study the experiences of 84 practitioners from the public sector collected during a series of workshops. Our findings show the need to locate participation initiatives in the context of the government policy cycle, that the policy cycle can be used for knowledge management in public participation projects and to recognize that practitioners represent a key stakeholder group in public participation.

1. Introduction

Stakeholders play an important role in the governance context (Schmid et al., 2001; Flak and Rose, 2005; Heeks, 2006) so public sector organizations need to know who their stakeholders are (Nabatchi et al., 2017) and support the relationships between stakeholders and the organization (Meijer, 2016). When the focus of stakeholder participation is on collecting the citizens' input or knowledge co-creation together with citizens, then knowledge management must be a central issue in public participation projects (see e.g., Graversgaard et al., 2017). In an increasingly digital environment, public sector organizations (PSOs) must not only know how stakeholders' needs and values are changing (Scupola and Mergel, 2022), but they must also ensure that organizational aims are being achieved and that the (costly) technological investments have the expected impact (Graversgaard et al., 2017; Lember et al., 2019).

PSOs also rely on participation experts and practitioners' professional knowledge to help them design successful participation projects (Barry and Legacy, 2023). Their involvement is important for the development of participation projects, but their role and contribution are not well-accounted for in literature on governance and participation. We note that there is a gap in the literature on practitioners' knowledge and how it is managed for designing public participatory processes. In this study we therefore aim to investigate practitioners' contribution to the design of participatory processes and how their knowledge can be collected and managed. This qualitative study, based on the sequential use of participative methods, contributes to the literature and research on stakeholders in public participatory processes as well as knowledge management in the public sector by answering the following research questions: First, how can the policy cycle be used as a knowledge management framework to collect and structure practitioners' knowledge for designing participation processes? Second, what is the role of practitioners and experts in the development of public participation projects?

For this purpose, we analyze the experiences of 84 practitioners from the public sector collected during a series of workshops. The use of sequential and participative qualitative methods allows us to adopt a holistic approach for understanding of the role of practitioners and knowledge management in the public participation projects. Our findings point out some important issues in the design of public participation projects. First, there is need to locate participation initiatives in the context of the government policy cycle as this allows to explore how a policy is interpreted and enacted by the practitioners. Second, the analysis shows how the policy cycle can be used for knowledge management in public participation projects. Third, the results show how the policy cycle can help with the selection and implementation of digital tools and processes in the design of participatory projects. Finally, the results show that practitioners are key stakeholder PSOs need for public participation projects.

This paper is structured as follows: In section 2, we provide the background to the topics of the study, that is, public participation, the stakeholders in participation processes, knowledge management and the policy cycle. Section 3 describes the research design, including the casing of the study, the methods used in the sequential qualitative approach and the data collection. In Section 4, we describe the findings. Section 5 discusses the results in the context of the literature, whilst Section 6 concludes this article with an overview of the limitations and some suggestions for future research.

2. Background

2.1. Public participation

Public participation is “the direct involvement […] of concerned stakeholders in decision-making about policies, plans or programs in which they have an interest” (Quick and Bryson, 2022, p. 1). Public authorities are often required to take into consideration opinions and comments expressed by the public, provide information on the procedures for participation and how the decisions are taken (European Parliament of the Council, 2003), to consider stakeholders' needs and expertise to develop adequate policies and solutions (Huijboom et al., 2009; Schuler, 2010). This makes public participation a useful instrument policymakers can use to shape policies (Howlett, 2011), to increase the effectiveness, capacity and legitimacy of public decision-making processes, modernize service delivery and increase public value (Espés et al., 2014; Parycek, 2020). Public participation can also be used to increase transparency and accountability in governments (Verschuere et al., 2012), fulfill legal requirements, and advance justice, social inclusion, empowerment and learning (Bryson et al., 2017; Bobbio, 2019). Stakeholder involvement is therefore not just about informing the public, but engaging in knowledge exchange to explore and generate solutions, high-quality plans and projects (Porwol et al., 2016).

Public participation projects can quickly become complicated, as they are socio-technical constructs that include several stakeholders and thus may have many and sometimes contradictory objectives to be achieved, using different participation methods, techniques, information artifacts, and technical facilities (Sæbø et al., 2011). Noveck (2009) suggests that the design elements of collaborative democracy, that is, granularity, groups, and reputation, are the key enabling properties for successful participation. She suggests that granularity, that is, the breaking down of complex problem into smaller and more manageable pieces, enables peers to engage in the best manner and assures a high level of involvement. Scherer and Wimmer (2016) recommend conceptualizing participation projects according to six dimensions: participation scope (motivation and objectives of the project), participants (stakeholder engagement and management), participation (participation services and processes), data and information (production and use of data), e-participation (tools and support for techniques), and implementation and governance (operations, administration, and management of the project). They argue that this framework can help design and implement participation projects, in particular those that use Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). Their strategic, top-down perspective allows project managers, initiators, owners, executives, and decision makers to plan, organize, and combine the participatory activities in a comprehensive way.

Webler et al. (2001) highlight that the design of public participation processes requires leadership, discussions, fairness, and power balance, which adds several challenges for the design of public participation processes. In addition, participatory processes increasingly use digital tools and channels to communicate and exchange information. The increasing implementation of e-government (Heeks, 2006), the provision of online public services (Sideri et al., 2019), as well as e-voting and e-campaigning (Gibson et al., 2016) have expanded thev opportunities for digital public decision-making processes (Espés et al., 2014; Parycek et al., 2014; Bertot et al., 2016). Strokosch and Osborne (2020) argue the for an ecosystem approach, that is, the public sector represents the integration of actors, resources and technologies, the interactions, the goals as well as multiple and competing agendas. In addition, they argue that context of the ecosystem (that is, political, financial, legal, and historical factors) will include actors' multiple and complex needs, and influence how policy goals are implemented. The integration of analog and online participation elements has made multi-phasic models of participation popular (Höchtl and Edelmann, 2021), but also increased their overall complexity. Bobbio (2019) suggests that this complexity can be reduced by ensuring that participatory processes are highly structured using well-defined phases with a pre-defined duration, where participants are provided with complete, balanced, and accessible information they then discuss in small groups moderated by neutral facilitators. Wirtz et al. (2018) point out that some of the problems stem from considering the design of public participation and e-participation processes separately rather than focusing on how the objectives can be achieved.

The analysis of such public participation processes in the literature highlights the need to carefully consider the relationship and interaction between stakeholders as well as the information and communication channels used, but also that access to the relevant knowledge makes the identification and involvement of stakeholders central in the design of public participation processes.

2.2. Stakeholders in participation processes

Freeman (1984) defines stakeholders as any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization's objective. Freeman's stakeholder theory is based on conventional managerial and organizational ideas, but is useful in the public sector context too as it allows to consider the organizational contexts and the organization's social responsibility toward the plurality of the different stakeholders and their goals (Flak and Rose, 2005). The critical role of users and stakeholders in participatory processes has also often been addressed in the public governance literature (Crosby et al., 2017; Bidwell and Schweizer, 2021). Schmid et al. (2001), for example, emphasizes the need to identify and involve stakeholders in the context of changing public sector organizations, whilst Flak and Rose (2005) argue that by identifying the stakeholders, it is possible to understand who will be affected by government initiatives, and to consider the different perspectives, objectives, processes, benefits and conflicts.

Citizens are often viewed as the main stakeholder group to be engaged in participatory processes. The literature identifies citizens as contributors and beneficiaries of public participation (Alford, 2016), responsible for identifying what is valuable to them and obtaining the information on how to be engaged in such processes (Williams and Shearer, 2011). One reason for this is that they have a democratic right to do so (Edelmann and Mergel, 2022). PSOs and governments may also support citizen involvement in order to achieve “substitution value” (Pestoff et al., 2006, p. 599), that is, when citizens carry out tasks originally performed by PSOs and governments that lead to cost and other savings. In the public sector, several stakeholders can be identified. Heeks (2006), for example, broadly identifies two stakeholder groups: (1) those involved in the development of the public system, and (2) those involved in operation of the system. Rowley (2011) proposes a larger typology: people as service users, people as citizens, businesses, small-to-medium sized enterprises, public administrators (employees), other government agencies, non-profit organizations, politicians, e-government project managers, design and IT developers, suppliers and partners, and researchers and evaluators. Further stakeholders mentioned in the literature include communities, government agencies, parliamentary commissions, committees, local authorities, politicians, contractors and IT organizations, research institutions, and NGOs (Nabatchi et al., 2017).

According to Janssen and Helbig (2018) public participation means knowing how to engage in “orchestration,” “quality assurance,” and “aggregating and reporting” activities (p. 103), but policy makers will turn to professionals to help develop and design public participation. Professional practitioners are those who have been trained or certified under emerging industry standards and are also an important stakeholder in participatory processes (Moore, 2012; King et al., 2015). Practitioners contribute significantly to participation processes with their activities, knowledge, innovations, and the results they achieve by designing and being involved in public participation processes (Bryson et al., 2013). They extend participation to include previously excluded voices, help decision-making processes be accessible to a broader range of stakeholders, support innovative engagement, increase quality, and promote different participatory techniques (Bherer and Lee, 2019). The professionalization of public participation practitioners sets new standards and codes of practice and thus changes participatory practice (Barry and Legacy, 2023), but practitioners not played a particularly prominent role in the participation literature so far, nor has the impact of their activities and knowledge been considered extensively in research agendas.

2.3. Knowledge management

Stakeholders contribute to public participatory processes with their specific knowledge. For businesses and governments alike, knowledge is an important strategic resource, and the management of this asset is viewed as critical to strategic organizational design (e.g., Drucker, 2012; Carayannis et al., 2021) and organizational success (Ipe, 2003). Knowledge management is an organizational activity that focuses on the exchange of information, skills and expertise between people or within and across organizations and institutions (Janus, 2016). Knowledge management is important as it implies the movement of knowledge within an organization to create economic value and help the organization benefit from competitive advantage (Hendriks, 1999). It can go beyond knowledge governance (Cao and Xiang, 2012) and focus on organizational aspects such as technology and memory systems (Choi et al., 2010), the role of human capital, and social factors (Stevens, 2010). It also involves the dissemination of innovative ideas, and thus may be considered as the basis of creativity and innovation within organizations (Lin, 2007). Ipe (2003) conceptual framework suggests that knowledge is influenced by the motivation of individuals to engage in knowledge sharing, the nature of the knowledge shared, the opportunities available for individuals to share and, above all, the culture of the particular work environment.

Knowledge management occurs in traditional organizational settings and digital environments (Almahamid, 2008). Parycek and Pircher (2003) argue that in the public sector context, dimensions of knowledge to be managed can include the organization's infrastructure and technologies, processes, strategies, employees activities' and creativity, but also its culture and values and the spatial opportunities for communication and interaction. In the public particpation context, participation is used to collect citizens' knowledge so that policy-makers can develop suitable problem definitions or policy formulations (Flak and Rose, 2005). Knowledge management can therefore be used for aggregating and analyzing the content that is to contribute to policy making, to know how and when to respond rapidly and appropriately to external changes (Zenk et al., 2022), but also for selecting and using participatory tools and instruments effectively (Janssen and Estevez, 2013).

2.4. Public participation in the policy cycle

Providing a participation platform for knowledge collection will not be enough: users must be guided and supported, collaboration needs to be managed, and participation projects will fail if context factors are not taken into consideration and complexity is not addressed (Toots, 2019). To address such issues, the policy cycle can be used to design participatory processes.

The policy cycle describes in a functional and purpose-bound manner the different phases of the participatory process, the actors involved, and the content to be developed. It has been used previously for structuring political-administrative processes, evidence-based policymaking, monitoring, and evaluation (Bridgman and Davis, 2003; Höchtl et al., 2016; Valle-Cruz and Sandoval-Almazán, 2022). Policy cycle phases are defined as problem definition, policy development, implementation, enforcement, and evaluation (Janssen and Helbig, 2018), or as agenda-setting, analysis, formulation, implementation, and monitoring (Kubicek and Aichholzer, 2016). The labels may vary, but describing and aligning the participation architecture to the phases of the policy cycle supports the planning of the requirements, participation instruments whilst retaining the big picture and outcomes to be achieved (Wirtz et al., 2018). The policy cycle therefore has several advantages: First the different phases of the process are clearly described in terms of their objectives; Second, it enables a detailed content analysis of the individual phases; Third, it offers a new perspective on the impact-oriented design and the implementation of participation projects in all phases. As identifying the relevant stakeholders is central to public participation (Schmid et al., 2001; Flak and Rose, 2005), the fourth advantage is that the policy cycle helps to identify the stakeholders and to define the interactions between them. Thus, the use of the policy cycle ensures transparent communication and information between stakeholders, consultation, decision-making and implementation processes.

The governance literature often focuses on the identification of the relevant stakeholder groups and how they can be engaged or involved in participatory processes. The literature shows that citizens are often addressed for content generation, whilst the public sector agencies are seen as primarily responsible for providing participation opportunities, collecting and managing the knowledge create, but practitioners are also increasingly being involved, so their role needs to be conceptualized and explained in more depth (Christensen, 2021). Whilst there is an extensive body of literature on knowledge management in the private sector, in the public sector context, the literature on knowledge management is more limited. We therefore identify the following research gap: as participatory processes become increasingly complex, the involvement of practitioners and the management of their knowledge is central to achieving the aims of public participation. Thus, the aim of this research is 2-fold: first, to study practitioners' role as a stakeholder in the context of public participation, and second, to show how the policy cycle can be used to collect, structure and managed practitioners' expertise for the design of participation projects. This empirical study answers the following research questions:

1. How can the policy cycle be used as a knowledge management framework to collect and structure practitioners' expert knowledge for designing participation processes?

2. What is the role of practitioners and experts in the development of public participation projects?

3. Research design

To answer these research questions the following section describes the research design, including the research case, the selected methods, the qualitative sequential analysis, and a description of the data collection process.

3.1. Research case: public participation in Austria

Participation is a central element in Austrian democracy: the constitution includes participation rights and participation can occur at policy or legislative level, for planning activities, program development or specific projects (Höchtl and Edelmann, 2021). Citizens and organizations have the right to convenient, simple and barrier-free electronic communication with PSOs (E-GovG, 2004), and there is an increasing focus on digital communication to support participation and engagement (Bundesministerium für Digitalisierung und Wirtschaft, 2017). Each participation initiative is designed on a case-by-case basis, but the legal requirements must be fulfilled (Höchtl and Lampoltshammer, 2019). In Austria, participation projects should not only focus on citizens but also give experts, interest groups, chambers, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), environmental protection organizations, or social organizations the opportunity to engage (Bundesministerium für Digitalisierung und Wirtschaft, 2020). The Austrian case is particularly interesting as public participation is of particular importance to PSOs, who aim to develop a user-centric public administration.

3.2. The sequential qualitative approach

Our research questions address the role of practitioners and managing their knowledge in the participatory process. Understanding the role of a specific group of stakeholders in the participatory process and extrapolating value for academic literature and practitioners requires a careful approach. This influences the methodological design of such a study (Massaro et al., 2015). Triangulation of different methods in qualitative design has been seen as an approach to increase the impact of the methods used, and especially the social sciences have provided strategies to address the issues arising from the multimethod analysis of data drawn from social interactions (Meijer et al., 2002; Mik-Meyer, 2020). An argument has been made to select a variety of methods in a sequential qualitative setting (Morse, 2010). The triangulation of different qualitative methods may help to understand the social aspects that influence why, how, and when certain actors share their knowledge to contribute to the design of public participation processes. Therefore, it is necessary to allow individuals to participate in the debate around knowledge management by identifying what they need to “feel at ease to share and create knowledge” (Rechberg and Syed, 2014, p. 435).

The active participation in the design and organization of knowledge management processes influences the research itself and the methods to explore these developments. Massaro et al.'s (2015) literature review on knowledge management research in the public sector shows that a common barrier is the engagement between researchers and the public sector employees. The collaborative approach to generating knowledge can methodologically be grounded in action research, specifically, participatory action research (PAR; Perz et al., 2021). This approach allows for the transdisciplinary integration of different areas of research (Perz et al., 2021), such as public participation, stakeholder engagement, policy and knowledge management through a variety of qualitative methods (Kujala et al., 2022). In addition to the focus on the involvement of specific stakeholders in the research process PAR is characterized by involving the researcher directly in the process (Berman, 2017). The objective of PAR is to improve the appearance of the community or specific domains of interest to them (Reason and Bradbury, 2001; Dick, 2004; Whitehead and McNiff, 2006; Berman, 2017). To achieve this, the research process follows specific steps, mostly a variation of planning, action, critical observation and reflection (Fitzgerald et al., 2015), making it possible to combine different methods to live and design the knowledge generating moment in a collaborative process between researchers and community (Westhues et al., 2008). PAR encourages mutual learning (Fitzgerald et al., 2015; Berman, 2017) and consequently the exchange and development of knowledge (Perz et al., 2021). Community-based participatory action research (CBPAR) is a methodological approach that focuses on seeking solutions to practical issues, generating evidence-based knowledge for improving practice, and empowering participants for change action (Whitehead and McNiff, 2006; Ivankova, 2017). To integrate the different qualitative methods and a CBPAR approach we used a sequential qualitative design following Creswell (2014), and applied different methods of data collection that build on each other in order to define with the practitioners the specific problem situation and to identify relevant dimensions to be investigated.

3.3. Data collection

According to a sequential qualitative mixed methods design (Morse, 2010), conducting the study includes the application of different qualitative methods during the direct interaction between participants of the research. In this study, these are the public participation experts and the researchers. The researchers, planned, moderated, participated in, documented, and evaluated the interactions with the stakeholders, consequently actively partaking in the activities. The entire data collection phase was iterative: Each phase of the research was built on the previous one and participants were constantly informed on the results they had previously obtained.

The project was commissioned by the Austrian Federal Ministry for Arts, Culture, the Civil Service and Sports, Department III/C/9 - Strategic Performance Management and Public Sector Innovation. The participating researchers planned and organized the workshops and activities together with the public servants responsible for the project. The invitation to participate in the workshops was send to the ministry's database of public participation experts, which had been updated beforehand as part of the project. Invitees were free to register for and attend the workshops in person (and for Workshop 4, held online). As the participants were contacted by the ministry, the participants provided their informed consent to the ministry when registering for the workshops or the consultation. At the beginning of each workshop, they were informed about the methods of data collection and signed the agreement regarding the anonymous use of the data collected. The invitation process and all GDPR relevant data were handled by the ministry as the organizer of the workshops. In addition, every workshop provided a detailed summary of the previous workshop, the current status and future steps of the project and the “why” of every activity. Documentation was stored on a secure university server and the raw data was only accessible to and handled by the researchers in charge of the project. Ethical considerations are especially important in public participation projects to ensure the trust of participants and create transparent processes in safe spaces. The project was not only meant to suggest the use of the policy cycle in public participation, but a public participation process itself, so the researchers and public servants took transparency and ethical considerations into account for every step of the project.

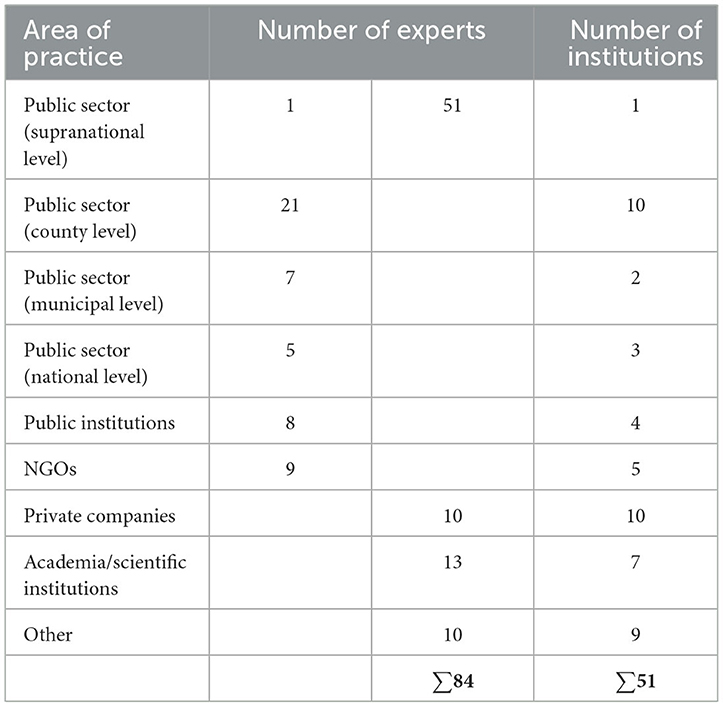

Each workshop lasted between three (online) and four (offline) hours. For the consultation, only practitioners who had attended at least one of the workshops beforehand were invited. In the consultation these practitioners had 21 days to comment a draft version of the project results. Throughout the project, 84 experts from 51 different institutions participated in the workshops. Most of the participants (61%) who registered for the workshops came from the public sector, as can be seen in Table 1. While the majority of participants of the workshops had a public sector background, private sector companies and academic/scientific organizations were involved too, allowing us to better understand how knowledge between different experts is shared.

3.3.1. Workshops

Workshops are a research method that can be used to draw a relationship between the workshop form and its outcomes (Ørngreen and Levinsen, 2017). They foster engagement, collaborative discussions and constructive feedback between the participants with the workshop facilitator, and in this particular study, the researchers and the organizers (Lain, 2017). The engagement in workshops is often very intense, allows the researcher to gather data through collaboratively shared experiences, and are regarded as being one of the primary ways of obtaining information-rich data that help establish the credibility of results from a qualitative study (Creswell and Poth, 2016). With a cooperative design researchers, workshop organizers and participants work together, and the transparent and mindful documentation of the results are important factors in such workshops (Schön, 1983).

Three workshops were organized, each addressed one of the following topics: “Participation in the Policy Cycle,” “Design and Methods,” and “Guiding Principles of Participation.” The methods employed during each workshops included keynotes, small-group brainstorming sessions (Heslin, 2009), and the world café methodology (Carson, 2011) in order to identify success factors, barriers, design and methods for each topic.

During the first workshop, “Participation in the Policy Cycle,” the theoretical background of the policy cycle was discussed. All the experts contributed during the brainstorming sessions to all the policy cycle phases, that is, agenda setting/topic identification, analysis and policy discussion, policy formulation, decision-making, implementation, and evaluation (described as continuous monitoring). The discussions addressed issues such as how digital participation is organized, best practices for each policy cycle phase and examples of participation projects in Austria and other countries. The comprehensive list of the projects and examples mentioned was expanded by the experts throughout the next workshops and published on a public sector website.

During the second workshop, brainstorming and world café methods were used again. The experts were invited to brainstorm on the design of digital, analog and hybrid formats of public participation projects using the policy cycle, best practices, as well as the new insights and ideas generated during the first workshop.

The third workshop focused on the most practical aspects of public participation processes, namely participatory instruments and tools. Based on best practices and design approaches identified in the previous workshops, participants discussed which methods and tools where available and how they could be applied best in participation scenarios. The relevant criteria for the selection of methods, i.e., analog or digital techniques for the implementation of a participation project were identified in this workshop.

These workshops specifically aimed to collect participants' knowledge and experiences on designing participatory projects and how they use digital tools. The results from each workshop were collected in the form of memos, protocols, visual documentation such as photographs and posters. The data generated during these workshops were collected digitally and made available online to participants.

3.3.2. Online consultation

The data collected during the first three workshops was protocolled, analyzed, and structured thematically according to the workshop topics. The themes provided the structure and contents for a draft policy on public participation, presented as a green paper to the participants for additional comments, ideas and insights on the online discussion platform discuto.io. A green paper is a consultation document to stimulate discussion on given topics with the relevant stakeholders and may result in the production of a white paper (EUR-Lex, 2022). Thirty experts participated in the online consultation and provided 170 comments to the draft, addressing how key aspects are understood. We revised the paper based on these comments, that mainly concerned its contents and comprehensibility. The revised version of the green paper was the result of iterative writing steps and made available to the participants.

3.3.3. Online workshop

Originally, the final workshop was to provide participants a revised draft of the green paper, the opportunity to further discuss it and so elicit further insights and ideas. Given the lock-down imposed by the Austrian government as a response to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the fourth workshop was held online. The online format provided an opportunity the public authority to test an innovative digital tool (Zoom) for a digital participatory process. This final online workshop combined the presentation of the green paper, online keynotes, a panel discussion, and small-group discussions held in online breakout rooms.

Topics of the workshop were ideas to improve and finalize the green paper as well as further discussion on PSOs' use of public participation in crisis situations, given the recent experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic. The panel discussion was recorded, and the results of the workshop and its breakout sessions were protocolled by three researchers. The main ideas of the breakout sessions were documented and prioritized by the experts on virtual whiteboards. For many participants it was the first time of using these. The results of the discussion were once again documented, analyzed, and included in the final version of the green paper.

4. Findings

The empirical study uses sequential qualitative design (Creswell, 2014) and the findings were derived in two ways: first, from the participants' expertise contributed during the participatory process, with the online and offline workshops and the consultation activities building on each other, and second, through the participation of the researchers in these the activities (Massaro et al., 2015). We first deductively derived an initial coding list based on the use of the policy cycle in the participation literature and then inductively operationalized the categories from the data collected during the workshops (transcripts, information sheets) to derive a framework of knowledge management in participatory processes.

The results provide insights into two dimensions: first, the as the data collection processes were designed as part of a public participation project, we were able to understand how the policy cycle can be used to design participation and how to integrate different contents and digital and analog methods into the policy cycle phases; second, the need to consolidate the knowledge about practitioners and their role in public participation.

This section shows the findings derived from the data, first presenting the use of the policy cycle to frame to design participation projects, and second, presenting insights on the role of practitioners in public participation processes.

4.1. Using the policy cycle to manage knowledge

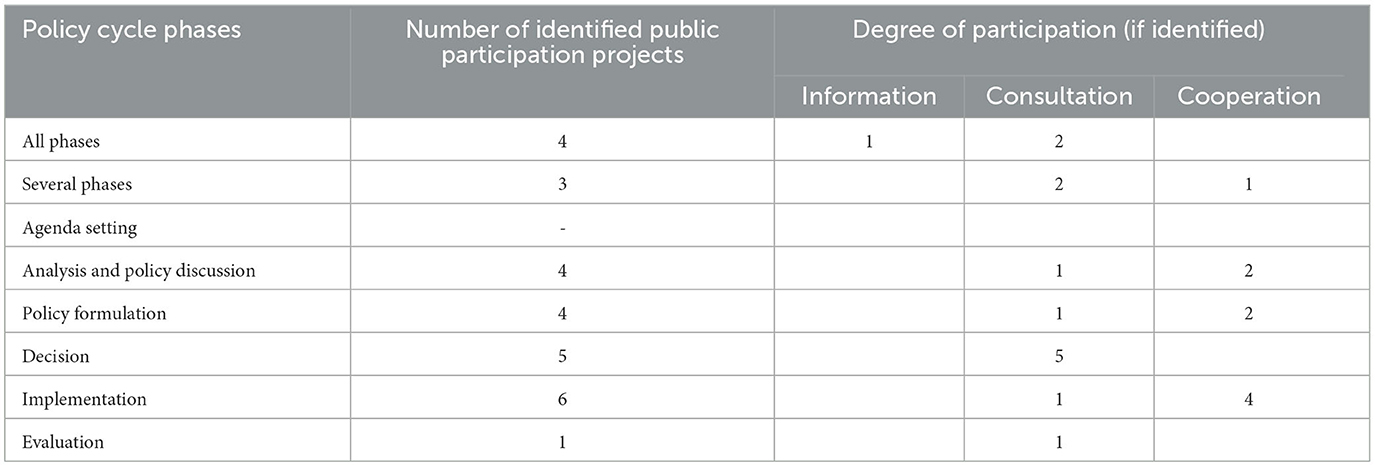

Our findings show that the experts differentiate between different types of participation in the context of the policy cycle. A public participation project may be continuous, i.e., span all or several phases of the policy cycle, or be more punctual, i.e., focused on a specific phase of the policy cycle. According to the Austrian practitioners the type of the participation effort may also vary on the basis of whether it provides information, a consultation, or cooperation (Parycek and Edelmann, 2009):

• Information: Information is seen as providing the basis on which further participation possibilities evolve, and transparency (possibly through the use of ICTs) as indispensable for taking informed decisions, citizen engagement and new forms of public-private partnerships.

• Consultation: the involved parties (citizens, companies, and NPOs) can express their opinion and provide answers to the questions posed, make proposals or official statements on submitted drafts Communication flows between the public, representatives in legislation (MPs) and/or the stakeholders in public administration, but the extent of civil society's influence on the decision can differ considerably.

• Cooperation: the state and civil society allow participants to have their say. Achieving a high impact in e-participation requires intense, electronically supported communication between all stakeholders and the people responsible for planning and the public.

Table 2 below shows the all the projects (27 altogether) identified according to each phase of the policy cycle and, if this information was available, the degree of participation. If the project included different degrees of participation, then the highest degree was chosen (i.e., if a project was informational, but also included a consultation, it was labeled as a consultation).

The projects show that in practice, public participation is common in nearly all phases of the policy cycle. While there are no examples of projects with an agenda setting phase, one project contained the evaluation phase, but these phases are covered by participation projects that have either include several or all phases of the policy cycle.

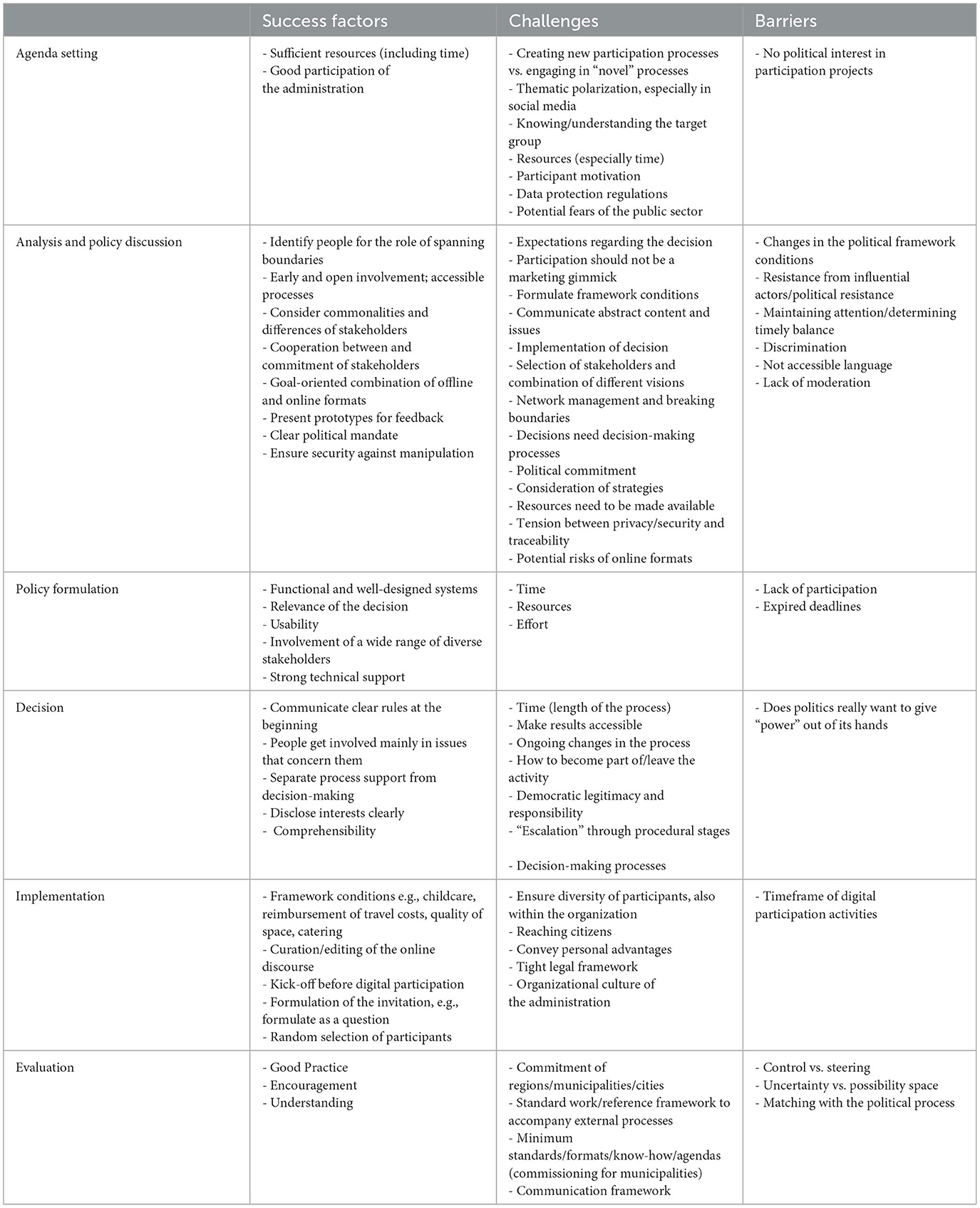

Based on the projects identified in the first workshop, the practitioners identified the success factors, challenges, and barriers for each phase of the policy cycle. Table 3 shows the practitioners' assessment on success factors, challenges, and barriers for public participation in each phase of the policy cycle.

Table 3. Success factors, challenges, and barriers for public participation in the different phases of the policy cycle.

The results show that the design of participation processes using the policy cycle must consider who, whom, when and in what form participation should occur, and, at the same time, the financial, personnel, temporal and framework conditions and, context-dependent requirements. During the workshops, the use of both analog and digital methods for participation projects was highlighted, and practitioners described their positive and negative experiences with the use of social media and digital tools. They noted that digital tools are often only used for communication and survey purposes, to inform or consult citizens and other stakeholders. But there are additional options that can be considered: IT systems support the digital implementation of participation methods and the digitalization of participation processes. This can increase the variety of participatory methods, digital tools and participatory processes. The practitioners highlighted that any digital method or tool selected must fit the policy cycle phase. This shows the need to consider:

• For the design of public participation:

- Degree of public participation.

- Effort and costs (incl. time).

- Success factors and challenges.

• For methods applied.

- Aim of the method.

- Data protection and privacy.

- Accessibility.

- Strengths/weaknesses of the method.

- Possible combinations with other methods.

- Monitoring and evaluation of the use of methods.

• For the organization/stakeholders conducting the participant process.

- Competencies required for the design and implementation.

- Functions and responsibilities.

- Preparation, implementation, follow-up.

Not all digital applications and solutions commonly used by practitioners can be used by public sector, such as certain social networks or messenger services. This raises the need to consider which digital tools and applications can be used by all stakeholders and public partners and integrated into existing participatory processes. At the same time, the context of the participation process, the policy cycle phase, the participants' competences (thus also digital skills, knowledge of participation processes, organization, and project management) and expected duration or frequency of their involvement will determine which digital solutions may represent the best choice. Providing an overview of the new technologies available can support public sector organizations make the best choices, and the specific phase of the policy cycle will also help achieve the ideal digital fit.

Using the policy cycle as a framework can help guide—in coordination with the set participation goals—every selection and decision within the policy cycle phase. Thus, the focus is not on a specific measure or instrument in terms of better or worse, but on the question of how defined and set objectives can be achieved within the specific phase of the policy cycle. Outcomes from all the policy cycle phases and evaluation results help further the development of participatory processes, and the selection of digital tools, processes, and communication channels for public participation.

4.2. Practitioners as stakeholders in public participation

The complexity of political-administrative decision-making and design processes, the growing demands for data protection, transparency, diversity, accessibility, and equality, as well as the continuous development of new technologies, pose challenges for the designers of participatory processes. Planning participation processes must consider the set objectives, the stakeholders, how participation influences each policy cycle phase, the connection(s) between each cycle phase and decision-making.

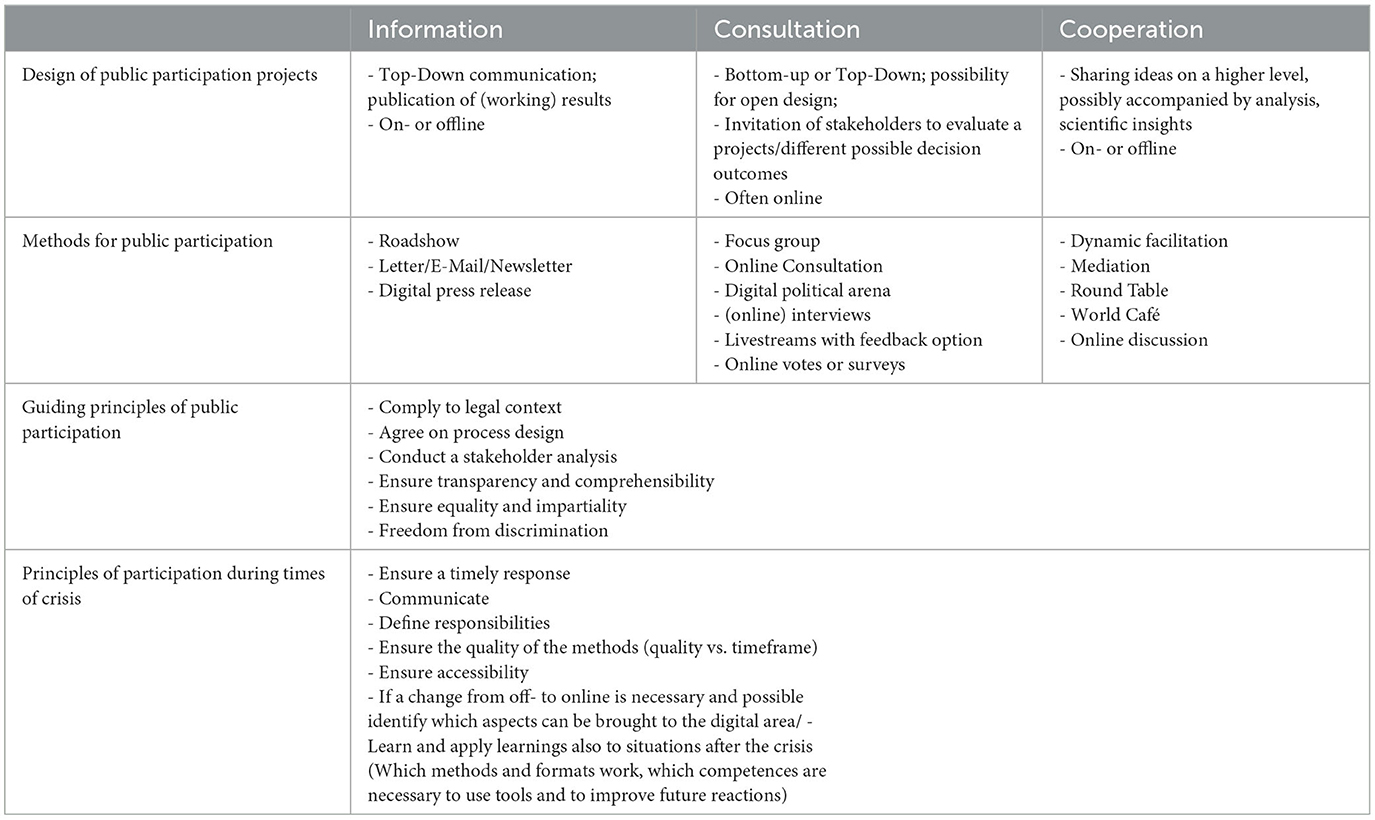

Our research addresses the need identified by Massaro et al. (2015) of bringing together the relevant stakeholders. Our study supported the exchange of stakeholders from different institutions and different public participation projects and shows that practitioners have vast knowledge in developing and adapting the participation process to the specific context in order to achieve the best outcomes possible, knowledge that contributes to a broad and holistic understanding of public participation. Table 4 shows that there many formats and methods for public participation and classifies the practitioners' knowledge according to the type of participation.

Table 4. Central characteristics of public participation in accordance with different degrees of the public participation process.

While factors such as the design, guiding principles and reacting to unexpected changes span the whole of the policy cycle, practitioners pointed out specific designs and methods useful for various types of public participation. The different policy cycle phases contain varying success factors, challenges, and barriers. Aside from a disruptive crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, there are also disruptive technologies and innovations that may have a significant effect on the design and implementation of public participation projects. Practitioners carefully consider the factors identified for each policy cycle, but also engage extensively in defining the framework of the project, supporting cooperation between organizations, and managing stakeholders. Based on their own experience and external knowledge, experts may select a specific process, design, and method to achieve the specific goal of the participation process, and to adapt them to the context. This makes them a valuable contributor and thus a key stakeholder in participatory processes and projects.

5. Discussion

Policy makers need to find ways of engaging the public and representatives in decision-making processes and create public value (Bidwell and Schweizer, 2021). As public participation projects include several stakeholders and may have several, even conflicting, objectives, use different participation methods, techniques, information artifacts, and technical facilities, they become increasingly complex (Sæbø et al., 2011; Scherer and Wimmer, 2016). The same time, Mergel (2015) suggests that a change of paradigm can be seen in the public sector, moving from a “need-to-know” to a “need-to-share” information, a paradigm that includes dimensions such as openness, conversations, inclusion, co-creation, and real-time feedback cycles. In order to utilize and benefit from existing knowledge and be able to adapt to a changing and unpredictable environment or to respond adequately to a crisis such as COVID-19 (United Nations, 2020), an exchange of knowledge is essential. When the focus of stakeholder participation is on collecting the citizens' input or knowledge co-creation together with citizens, then knowledge management must be made a central issue in public participation projects (see e.g., Graversgaard et al., 2017). Ipe (2003) defines knowledge management as “the act of making knowledge available to others within the organization (sic)” [p. 341]. It involves the dissemination of innovative ideas, can be considered as the basis of creativity and innovation within organizations (Armbrecht et al., 2001; Lin, 2007). Ipe's (2003) conceptual framework suggests that knowledge is influenced by the motivation of individuals to engage in knowledge sharing, the nature of the knowledge shared, the opportunities available for individuals to share and, above all, the culture of the particular work environment. Whilst private sector organizations use several knoweldge management techniques, public sector organizations too must be able to manage the content and knowledge collected from and made available to the public, not find themselves in a position where they are overwhelmed or unable to use the data collected (Edelmann et al., 2017).

In this research, we aimed to investigate policy cycle can be used as a knowledge management framework to design participatory processes, and to understand the role of practitioners in participation projects. Thus, we wanted to answer the following two questions: First, how can the policy cycle be used as a knowledge management framework to collect and structure practitioners' knowledge for designing participation processes? Second, how can the policy cycle be used to incorporate digital tools and processes into the design of public participation? Answering the research questions shows that the policy cycle can be used to frame a holistic understanding of public participation and that practitioners are an important stakeholder in public participation, more than has been considered in the literature so far.

Our findings point to some important issues in the design of public participation projects and the use of a knowledge framework in the public sector. First, we identified how the policy cycle can be used as a knowledge management framework in the design of participation processes. This begins by locating the participation initiatives in the context of the government policy cycle as this allows to explore how a policy is interpreted and enacted by the practitioners in local contexts and organizations. Second, our analysis shows how the policy cycle can be used for managing information collected in public participation projects, and that it can be used to help with the selection and implementation of digital tools and processes best suited to a particular participatory project. Third, the results show how the policy cycle can help with the selection and implementation of digital tools and processes in the design of participatory projects. Fourth, the use of sequential, participative, qualitative methods allows for a holistic approach to the use of digital applications and knowledge management in the public sector, as well as an in-depth understanding of the practitioners' knowledge and role in public participation.

In this study we identified how the policy cycle can be used as a knowledge management framework in the design of participation processes. This begins by locating the participation initiatives in the context of the government policy cycle as this allows to explore how a policy is interpreted and enacted by the practitioners in local contexts and organizations. The policy cycle was used as a knowledge framework for collecting practitioners' knowledge and experiences in public participation. The policy cycle allows PSOs to consider in a structured manner how to prepare, design and implement the participation project in terms of different competencies different stakeholders must have, their functions and responsibilities. The practitioners came from different PSOs, public institutions, NGOs, private companies and scientific companies, and the policy cycle was successfully implemented as a knowledge management framework to collect, share and collate their knowledge in a format that is available to all Austrian PSOs (Rosenbichler et al., 2020). The findings gained show that the policy cycle, can be used as a knowledge management framework to be able to carefully select the tools to systematically collect, structure and share stakeholders' knowledge in different participation processes.

The public sector cannot not simply absorb or incorporate new digital tools into old administrative regimes and has to take care to avoid vendor lock-in. Instead, public administrators have use digital tools as a way to strategically manage user participation and stakeholders (McNutt, 2014). Our analysis shows how the policy cycle can be used to help with the selection and implementation of digital tools and processes best suited to the aims of a particular participatory project. In this study we therefore also consider how the policy cycle can be used to incorporate digital tools and processes into the design of public participation. Providing an overview of the new technologies available can support users make choices, but the phase of the policy cycle can help achieve the ideal digital fit. By considering the phase, the digital methods, formats, and tools will help to design the participation project according to the degree of participation (information, consultation, cooperation), the costs, the barriers that need to be addressed as well as the factors that lead to success. The methods to be used will be selected according to criteria such as the aim of the method itself, the strengths and weaknesses of the method, data protection and privacy issues, accessibility, how it can be combined with other methods. The policy cycle not only provides the principles for the design of the public participation project, but also helps practitioners decide how to select the most suitable methods and tools according to the policy cycle phase and to achieve the set aims. While the different phases show varying success factors, challenges and barriers, the results show that in all phases of the policy cycle the participants are concerned with the selection, cooperation, and management of the stakeholders, finding and managing the time for the participation project and defining the framework. Based on their own experience and external knowledge, practitioners may select a specific process design and method to adopt public participation processes to achieve their specific goal.

PSOs should be able to adapt to dynamic environments and be able to respond to crisis-related system disruptions such as epidemics or massive knowledge loss (Zenk et al., 2022). As the COVID-19 lockdowns affected the research design of the project, the topic of public participation in crisis situations and the need to rapidly test innovative digital tools and processes became part of the workshop series. The use of the policy cycle showed how following guidelines is important, but that it is a flexible tool that can be adapted to any situation and crisis. As the continuous evaluation of the policy cycle represents an important phase, this allows agile, resilient, and knowledgeable activities and adaptations to changing situations. The use of the policy cycle to design the workshop in the new COVID-19 context resulted in the creation of additional knowledge on how to use the policy cycle to design participation, digitally involve stakeholders in public participation projects according to the different stages of the policy cycle and to manage the content created.

Public sector organizations need to know who their stakeholders are (Nabatchi et al., 2017) and understand the relationships between stakeholders and the organization (Meijer, 2016), but most research focuses on the identification of the relevant stakeholder groups that are to be engaged in participatory processes. The production of content and knowledge through stakeholders' participation in public processes will continue with increased access to tools, applications, databases and knowledge, and increased transparency and skills (Tapscott and Williams, 2006). In an increasingly digital environment, public sector organizations must also be able to understand how stakeholders' needs and values change accordingly (Scupola and Mergel, 2022), ensure that organizational aims are being achieved and that the (costly) technological investments have the expected impact (Bason, 2018; Lember et al., 2019). All stakeholders play an important role in participatory processes, one particular group has so far not played a prominent role in literature, even though their role is increasingly important for the design of successful participation projects. Although PSOs rely on experts' and practitioners' professional knowledge to develop successful participation projects (Barry and Legacy, 2023), their role, involvement and contribution is not well-accounted for, and then, often only theoretically. In some, e.g., Austria, participation projects should not only focus on citizens as stakeholders, but also consider others as stakeholders too, including experts. Some authors (see e.g., Ferm and Tomaney, 2018; Linovski, 2019) are critical of the increasing involvement of experts and practitioners in shaping public sector processes, but in this empirical study we show that the diversity of the practitioners' knowledge contributes different types of insights and knowledge, and, in terms of Freeman's stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984), will affect the achievement of public participation processes. The results gained here provide in-depth understanding of the practitioners' knowledge and role in public participation. In this project, we were able to empirically collect, combine, analyze, and consolidate the practitioners' knowledge and thus their role as a stakeholder that significantly contributes to public participation, even in times of crisis. Given the proliferation of different methods and approaches for facilitating public participation, and that practitioners' knowledge must be collected and managed in a way that is accessible to others, the policy cycle allows the greatest flexibility. The policy cycle can be used to collect and use practitioners' knowledge in a structured manner, and the results show how their expertise and knowledge are key to developing sustainable practices that can adapt to change and also improve future public participation processes (Flak and Rose, 2005).

We were able to answer the research questions, but this study also had some unexpected findings. Knowledge sharing and its managament are understood to be important as knowledge can help the organization have a competitive advantage and thus create economic value (Hendriks, 1999). Knowledge management needs to be available for public sector organizations, so that they can easily access, maintain and update the relevant knowledge they need in order to fulfill and implement European and national policies on public participation. Public sector organizations need to achieve economic value by engaging in collaborative governance (Newman et al., 2004) and use digital tools not only to gain more knowledge (see e.g., Abbate et al., 2019), but also to manage and share this knowledge with others. By collecting, managing and sharing this knowledge in a structured way, it is possible to overcome known barriers in public participation such as a lack of political support. We were particularly surprised by the practitioners' willingness to contribute their knowledge and experiences not only during the workshops but in future too. Their key role as participation stakeholders, particularly in the context of public sector governance knowledge and management, but also an increasingly professional and digital public participation needs to be recognized in the participation literature and empirically analyzed in more depth.

6. Conclusion

This study contributes to the literature on public participation, knowledge management and stakeholder theory in the public sector context. In this paper, we aim to contribute to the literature of participatory planning to account for the both the digitalization and professionalization of participation. Public participation is based on stakeholders' contribution and generation of new knowledge and is to lead to the sustainable implementation of ideas and solutions and the further development of participatory procedures, for example by monitoring participation projects and evaluating both the processes and outcomes. This study provides empirical evidence on the role of practitioners as stakeholders in the design of participation processes. The use of the policy cycle as a framework for participation creates transparency in political-administrative processes and at the same time, provides a common framework of understanding between the political-administrative system and the stakeholders, including the practitioners. It supports the stakeholders address the political-administrative system in an impact-oriented manner and enables the administration to proactively identify and communicate participation requirements. The use of the policy cycle thus not only helps to develop participation processes, but also provides a format to collect practitioners' expertise and make it available to others. The policy cycle thus creates an interface between the object of participation and the administrative system.

This study has its limitations though: Although several qualitative methods were used, quantitative methods should be used to triangulate the results. Also, the framework was developed expertise and knowledge but tested once only, in the COVID-19 emergency context. Thus, future research could focus on two aspects: First, on the role of practitioners as stakeholders in different the different policy cycle phases, in different contexts, including digital and hybrid formats, using different participation methods, and focusing on different dimensions, such as their competences, functions, and responsibilities; second, even though this project was developed and evaluated using the policy cycle, we urge to test the validity of the policy cycle by involving practitioners in the development of a participation project that includes all the policy cycle phases.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

NE: PI, data collection, literature review, method selection, writing of the first version, and final reading prior to submission. VA: data collection, literature review, analysis, and contribution to writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on the project “Praxisleitfaden digitale Partizipation (Practice Guide Digital Participation)” conducted with Mag.a. Ursula Rosenbichler, Mag. Alexander Grünwald, and Mag. Michael Kallinger from the Federal Ministry for Arts, Culture, the Civil Service and Sport (BMKöS), Section III - Public Service and Public Sector Innovation, III/C/9 - Strategic Performance Management and Public Sector Innovation, Hohenstaufengasse 3, 1010 Wien.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbate, T., Codini, A. P., and Aquilani, B. (2019). Knowledge co-creation in open innovation digital platforms: processes, tools and services. J. Bus. Indus. Market. 2018, 276. doi: 10.1108/JBIM-09-2018-0276

Alford, J. (2016). Co-production, interdependence and publicness: extending public service-dominant logic. Publ. Manag. Rev. 18, 673–691. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2015.1111659

Almahamid, S. (2008). “The role of agility and knowledge sharing on competitive advantage: an empirical investigation in manufacturing companies in Jordan,” in Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 19th Annual Conference POMS La Jolla, CA.

Armbrecht, Jr. F. R., Chapas, R. B., Chappelow, C. C., Farris, G. F., Friga, P. N., Hartz, C. A., et al. (2001). Knowledge management in research and development. Res. Technol. Manag. 2001, 28–48. doi: 10.1080/08956308.2001.11671438

Barry, J., and Legacy, C. (2023). Between virtue and profession: theorising the rise of professionalised public participation practitioners. Plan Theory 22, 85–105. doi: 10.1177/14730952221107148

Bason, C. (2018). Leading Public Sector Innovation 2E: Co-creating for a Better Society. Bristol: Policy Press.

Berman, T. (2017). Conceptual Context. In Public Participation as a Tool for Integrating Local Knowledge into Spatial Planning: Planning, Participation, and Knowledge (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 11–34. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-48063-3_3

Bertot, J. C., Estevez, E., and Janowski, T. (2016). Universal and Contextualized Public Services: Digital Public Service Innovation Framework. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Bherer, L., and Lee, C. W. (2019). “Consultants: the emerging participation industry,” in Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance, eds S. Elstub, O. Escobar (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 196–208. doi: 10.4337/9781786433862.00023

Bidwell, D., and Schweizer, P. J. (2021). Public values and goals for public participation. Environ. Pol. Govern. 31, 257–269. doi: 10.1002/eet.1913

Bobbio, L. (2019). Designing effective public participation. Pol. Soc. 38, 41–57. doi: 10.1080/14494035.2018.1511193

Bridgman, P., and Davis, G. (2003). What use is a policy cycle? Plenty, if the aim is clear. Austr. J. Publ. Admin. 62, 98–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8500.2003.00342.x

Bryson, J. M., Quick, K. S., Slotterback, C. S., and Crosby, B. (2013). Designing public participation processes. Publ. Admin. Rev. 73, 23–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02678.x

Bryson, J. M., Sancino, A., Benington, J., and Sørensen, E. (2017). Towards a multi-actor theory of public value co-creation. Publ. Manag. Rev. 19, 640–654. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2016.1192164

Bundesministerium für Digitalisierung und Wirtschaft (2017). Administration on the Net—The ABC guide of eGovernment in Austria. Vienna: Bundesministerium für Digitalisierung und Wirtschaft. Available online at: https://www.bmdw.gv.at/en/E-Government-ABC.html (accessed May 24, 2022).

Bundesministerium für Digitalisierung und Wirtschaft (2020). Beteiligung der Öffentlichkeit. Available online at: https://www.bmdw.gv.at/Themen/Digitalisierung/Digitales-Oesterreich/Beteiligung-der-Oeffentlichkeit.html (accessed May 24, 2022).

Cao, Y., and Xiang, Y. (2012). The impact of knowledge governance on knowledge sharing. Manag. Decision 50, 591–610. doi: 10.1108/00251741211220147

Carayannis, E. G., Ferreira, J. J., and Fernandes, C. (2021). A prospective retrospective: conceptual mapping of the intellectual structure and research trends of knowledge management over the last 25 years. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 581. doi: 10.1108/JKM-07-2020-0581

Carson, L. (2011). Designing a public conversation using the World Cafe method: paper in themed section: the value of techniques. Soc. Alternat. 30, 10. doi: 10.3316/ielapa.201106325

Choi, S. Y., Lee, H., and Yoo, Y. J. M. (2010). The impact of information technology and transactive memory systems on knowledge sharing, application, and team performance: a field study. MIS Quart. 2010, 855–870. doi: 10.2307/25750708

Christensen, J. (2021). Expert knowledge and policymaking: a multi-disciplinary research agenda. J. Pol. Polit. 49, 455–471. doi: 10.1332/030557320X15898190680037

Creswell, J. W. (2014). A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research: Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches: Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Crosby, B. C., ‘t Hart, P., and Torfing, J. (2017). Public value creation through collaborative innovation. Publ. Manag. Rev. 19, 655–669. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2016.1192165

Dick, B. (2004). Action research literature: themes and trends. Act. Res. 2, 425–444. doi: 10.1177/1476750304047985

Edelmann, N., Krimmer, R., and Parycek, P. (2017). “How online lurking contributes value to E-participation: a conceptual approach to evaluating the role of lurkers in e-participation,” in Paper Presented at the 2017 Fourth International Conference on eDemocracy & eGovernment (ICEDEG) Quito. doi: 10.1109/ICEDEG.2017.7962517

Edelmann, N., and Mergel, I. (2022). “The implementation of a digital strategy in the Austrian Public Sector,” in Paper Presented at the DG. O 2022: The 23rd Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research Seoul. doi: 10.1145/3543434.3543640

E-GovG (2004). Federal Act on Provisions Facilitating Electronic Communications with Public Bodies (E-Government Act—E-GovG), 20003230 C.F.R Vienna.

Espés, C. P., Wimmer, M. A., Moreno-Jimenez, J. M., Janssen, M., Bannister, F., Glassey, O., et al. (2014). “A framework for evaluating the impact of e-participation experiences,” in Paper Presented at the Electronic Government and Electronic Participation: Joint Proceedings of Ongoing Research, Posters, Workshop and Projects of IFIP EGOV 2014 and EPart 2014 Amsterdam.

EUR-Lex (2022). Green Paper. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM:green_paper (accessed May 24, 2022).

Ferm, J., and Tomaney, J. (Eds.) (2018). Planning practice: critical perspectives from the UK. Routledge.

Fitzgerald, C., Moores, A., Coleman, A., and Fleming, J. (2015). Supporting new graduate professional development: a clinical learning framework. Austr. Occup. Therapy J. 62, 13–20. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12165

Flak, L. S., and Rose, J. (2005). Stakeholder governance: adapting stakeholder theory to e-government. Commun. Assoc. Inform. Syst. 16, 31. doi: 10.17705/1CAIS.01631

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gibson, J. P., Krimmer, R., Teague, V., and Pomares, J. (2016). A review of e-voting: the past, present and future. Ann. Telecommun. 71, 279–286. doi: 10.1007/s12243-016-0525-8

Graversgaard, M., Jacobsen, B. H., Kjeldsen, C., and Dalgaard, T. (2017). Stakeholder engagement and knowledge co-creation in water planning: can public participation increase cost-effectiveness? Water 9, 191. doi: 10.3390/w9030191

Heeks, R. (2006). Implementing and Managing eGovernment: An International Text. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage.

Hendriks, P. (1999). Why share knowledge? The influence of ICT on the motivation for knowledge sharing. Knowl. Process Manag. 6, 91–100. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1441(199906)6:2<91::AID-KPM54>3.0.CO;2-M

Heslin, P. (2009). Better than brainstorming? Potential contextual boundary conditions to brainwriting for idea generation in organizations. J. Occup. Org. Psychol. 82, 129–145. doi: 10.1348/096317908X285642

Höchtl, B., and Edelmann, N. (2021). A case study of the digital agenda of the City of Vienna: e-participation design and enabling factors Electronic Government. Int. J. 18, 70–93. doi: 10.1504/EG.2022.119609

Höchtl, B., and Lampoltshammer, T. J. (2019). “Rechtliche Rahmenbedingungen und technische Umsetzung von E-Government in Österreich,” in Handbuch E-Government - Technikinduzierte Verwaltungsentwicklung, eds J. E. Stember, E. Wolfgang, A. Neuroni, A. Spichiger, F. R. Habbel, and M. Wundara (Berlin: Springer), 10.

Höchtl, J., Parycek, P., and Schöllhammer, R. (2016). Big data in the policy cycle: policy decision making in the digital era. J. Org. Comput. Electr. Commerce 26, 147–169. doi: 10.1080/10919392.2015.1125187

Howlett, M. (2011). Public managers as the missing variable in policy studies: an empirical investigation using Canadian data. Rev. Pol. Res. 28, 247–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-1338.2011.00494.x

Huijboom, N., Van Den Broek, T., Frissen, V., Kool, L., Kotterink, B., Nielsen, M., et al. (2009). Public Services 2.0: the Impact of Social Computing on Public Services. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; Institute for Prospective Technological Studies, Joint Research Centre, European Commission.

Ipe, M. (2003). Knowledge sharing in organizations: a conceptual framework. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2, 337–359. doi: 10.1177/1534484303257985

Ivankova, N. V. (2017). Applying mixed methods in community-based participatory action research: a framework for engaging stakeholders with research as a means for promoting patient-centredness. J. Res. Nurs. 22, 282–294. doi: 10.1177/1744987117699655

Janssen, M., and Estevez, E. (2013). Lean government and platform-based governance—doing more with less. Govern. Inform. Quart. 30, S1–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2012.11.003

Janssen, M., and Helbig, N. (2018). Innovating and changing the policy-cycle: policy-makers be prepared! Govern. Inform. Quart. 35, S99–S105. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2015.11.009

Janus, S. S. (2016). Becoming a Knowledge-Sharing Organization: A Handbook for Scaling Up Solutions Through Knowledge Capturing and Sharing. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications.

King, C. S., Feltey, K. M., and Susel, B. O. N. (2015). “The question of participation: toward authentic public participation in public administration,” in The Age of Direct Citizen Participation, ed N. C. Roberts (London: Routledge), 391–408.

Kubicek, H., and Aichholzer, G. (2016). “Closing the evaluation gap in e-participation research and practice,” in Evaluating e-Participation, eds G. Aichholzer, H. Kubicek, L. Torres (Berlin: Springer), 11–45.

Kujala, J., Sachs, S., Leinonen, H., Heikkinen, A., and Laude, D. J. B., and Society (2022). Stakeholder engagement: past, present, and future. Bus. Society 61, 1136–1196. doi: 10.1177/00076503211066595

Lain, S. (2017). Show, don't tell: reading workshop fosters engagement and success. Texas J. Liter. Educ. 5, 160–167.

Lember, V., Brandsen, T., and Tõnurist, P. (2019). The potential impacts of digital technologies on co-production and co-creation. Publ. Manag. Rev. 21, 1665–1686. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2019.1619807

Lin, H. F. (2007). Knowledge sharing and firm innovation capability: an empirical study. Int. J. Manpower 28, 315–332. doi: 10.1108/01437720710755272

Linovski, O. (2019). Shifting agendas: private consultants and public planning policy. Urb. Affairs Rev. 55, 1666–1701. doi: 10.1177/1078087417752475

Massaro, M., Dumay, J., and Garlatti, A. (2015). Public sector knowledge management: a structured literature review. J. Knowl. Manage. 19, 530–558. doi: 10.1108/JKM-11-2014-0466

McNutt, K. (2014). Public engagement in the W eb 2.0 era: social collaborative technologies in a public sector context. Can. Publ. Admin. 57, 49–70. doi: 10.1111/capa.12058

Meijer, A. (2016). Coproduction as a structural transformation of the public sector. Int. J. Public Sector Manag. 29, 596–611. doi: 10.1108/IJPSM-01-2016-0001

Meijer, P., Verloop, N., and Beijaard, D. (2002). Multi-method triangulation in a qualitative study on teachers' practical knowledge: an attempt to increase internal validity. Qual. Quant. 36, 145–167. doi: 10.1023/A:1014984232147

Mergel, I. (2015). “Designing social media strategies and policies,” in Handbook of Public. Administration, eds J. L. Perry and R. K. Christensen (San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.), 456–468.

Moore, A. (2012). Following from the front: theorizing deliberative facilitation. Crit. Pol. Stud. 6, 146–162. doi: 10.1080/19460171.2012.689735

Morse, J. M. (2010). Simultaneous and sequential qualitative mixed method designs. Qualit. Inq. 16, 483–491. doi: 10.1177/1077800410364741

Nabatchi, T., Sancino, A., and Sicilia, M. (2017). Varieties of participation in public services: the who, when, and what of coproduction. Publ. Admin. Rev. 77, 766–776. doi: 10.1111/puar.12765

Newman, J., Barnes, M., Sullivan, H., and Knops, A. (2004). Public participation and collaborative governance. J. Soc. Pol. 33, 203–223. doi: 10.1017/S0047279403007499

Noveck, B. S. (2009). Wiki Government: How Technology Can Make Government Better, Democracy Stronger, and Citizens More Powerful. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Ørngreen, R., and Levinsen, K. (2017). Workshops as a research methodology. Electr. J. E-learning 15, 70–81.

Parycek, P. (2020). Integrierte Partizipation im Policy Cycle. Available online at: https://www.oeffentlicherdienst.gv.at/verwaltungsinnovation/oeffentlichkeitsbeteiligung/Leitfaden_DigiPart_KickOff_Peter_Parycek_Keynote_24012020.pdf?7ciyee (accessed May 24, 2022).

Parycek, P., and Edelmann, N. (2009). “Eparticipation and edemocracy in Austria: projects and tenets for an edemocracy strategy,” in Paper presented at the 1st International Conference on eGovernment & eGovernance. Ankara.

Parycek, P., and Pircher, R. (2003). “Teaching e-government and knowledge management,” in E-Government: Legal, Technical, and Pedagogical Aspects, eds F. Galindo and R. Traunmuller (Albaracin), 213–228.

Parycek, P., Sachs, M., Sedy, F., and Schossböck, J. (2014). Evaluation of an E-participation Project: Lessons Learned and Success Factors from a Cross-Cultural Perspective. Berlin: Heidelberg.

Perz, S. G., Arteaga, M., Baudoin Farah, A., Brown, I. F., Mendoza, E. R. H., de Paula, Y. A. P., et al. (2021). Participatory action research for conservation and development: experiences from the Amazon. Sustainability 14, 233. doi: 10.3390/su14010233

Pestoff, V., Osborne, S. P., and Brandsen, T. (2006). Patterns of co-production in public services: some concluding thoughts. Publ. Manag. Rev. 8, 591–595. doi: 10.1080/14719030601022999

Porwol, L., Ojo, A., and Breslin, J. G. (2016). An ontology for next generation e-Participation initiatives. Govern. Inform. Quart. 33, 583–594. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2016.01.007

Quick, K. S., and Bryson, J. M. (2022). “Public participation,” in Handbook on Theories of Governance, eds C. Ansell, J. Torfing (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 22.

Reason, P., and Bradbury, H. (2001). Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rechberg, I. D., and Syed, J. (2014). Appropriation or participation of the individual in knowledge management. Manag. Decision 52, 426–445. doi: 10.1108/MD-04-2013-0223

Rosenbichler, U., Grünwald, A., Kallinger, M., Edelmann, N., Albrecht, V., and Eibl, G. (2020). Grünbuch: Partizipation im digitalen Zeitalter. Vienna. Available online at: https://www.oeffentlicherdienst.gv.at/verwaltungsinnovation/oeffentlichkeitsbeteiligung/201103_Partizipation_Gruenbuch_A4_BF_1.pdf?7t15d4 (accessed May 24, 2022).

Rowley, J. (2011). e-Government stakeholders—who are they and what do they want? Int. J. Inform. Manag. 31, 53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2010.05.005

Sæbø, Ø., Flak, L. S., and Sein, M. K. J. G. I. Q. (2011). Understanding the dynamics in e-Participation initiatives: looking through the genre and stakeholder lenses. Govern. Inform. Quart. 28, 416–425. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2010.10.005

Scherer, S., and Wimmer, M. A. (2016). “A metamodel for the E-participation reference framework,” in Paper Presented at the International Conference on Electronic Participation Guimarães: Springer International Publishing.

Schmid, B., Stanoevska-Slabeva, K., and Tschammer, V. (Eds.). (2001). Towards the E-Society: E-commerce, E-business, and E-government. Springer Science & Business Media. 74.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner. How Professionals Think in Action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Schuler, D. (2010). Online Deliberation and Civic Intelligence. Open Government, Collaboration, Transparency and Participation in Practice. Sebastopol, CA: OReilly.

Scupola, A., and Mergel, I. (2022). Co-production in digital transformation of public administration and public value creation: the case of Denmark. Govern. Inform. Quart. 39, 101650. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2021.101650

Sideri, M., Kitsiou, A., Filippopoulou, A., Kalloniatis, C., and Gritzalis, S. (2019). E-Governance in educational settings: Greek educational organizations leadership's perspectives towards social media usage for participatory decision-making. Internet Res. 29, 818. doi: 10.1108/IntR-05-2017-0178

Stevens, R. H. (2010). Managing human capital: how to use knowledge management to transfer knowledge in today's multi-generational workforce. Int. Bus. Res. 3, 77. doi: 10.5539/ibr.v3n3p77

Strokosch, K., and Osborne, S. P. (2020). Co-experience, co-production and co-governance: an ecosystem approach to the analysis of value creation. Pol. Polit. 48, 425–442. doi: 10.1332/030557320X15857337955214

Tapscott, D., and Williams, A. D. (2006). Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything. New York, NY: Penguin.

Toots, M. (2019). Why E-participation systems fail: the case of Estonia's Osale. Govern. Inform. Quart. 36, 546–559. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2019.02.002