95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 05 July 2023

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1197317

This article is part of the Research Topic Researching Political Legitimacy: Concepts, Theories, Methods and Empirical Studies View all 9 articles

A long-standing argument in the political sciences holds that high levels of inequality are incompatible with democracy. Although a number of studies have by now investigated whether income inequality endangers democratic consolidation and stability through corroding popular support, the findings remain inconclusive. This study provides new evidence for a sociotropic effect of macroeconomic income inequality on trust in the institutions of representative democracy by making use of the random effects within between specification in multilevel models for data from 28 European democracies over a period of 16 years. The findings show that both long-standing differences in income inequality between countries and changes in inequality within countries over time are negatively related to trust in institutions. While the spirit-level thesis states that this effect should be more pronounced among rich democracies, the findings show that the effect of inequality is stronger in countries that are less affluent. Further analyses on whether the social-psychological mechanism proposed by the spirit-level thesis mediates the effect of inequality on trust document a partial transmission via status concerns and social trust. However, the study suggests that income inequality primarily influences trust in institutions through evaluation-based processes as captured by economic evaluations.

Thirty years after the proclaimed end of history (Fukuyama, 1989), we find ourselves looking back at a decade marked by a widespread concern for the state and future of liberal democracy. Especially in Western countries, there is an ongoing debate about the “democratic malaise” (Foa et al., 2020), if not about a veritable legitimacy crisis (Kriesi, 2013; Van der Meer, 2017; Van Ham et al., 2017).

Even before authoritarian and far-right populist parties “became a prominent feature of contemporary politics in Western democracies” (Gidron and Hall, 2017; p. 57), still before the election of Donald Trump or the Brexit referendum burned into collective memory as an illustration of the ramifications of societal polarization, scholars have discussed the extent, causes and consequences of declining confidence in political institutions and actors across affluent representative democracies (e.g., Norris, 1999, 2011; Pharr et al., 2000; Dalton, 2004). Among the potential factors that threaten democratic legitimacy in established democracies by depressing popular support, economic inequality has taken a very prominent place in the debate (e.g., Andersen and Curtis, 2012).

Rising inequality may well be one of the most pressing concerns in Western democracies. It is by now relatively undisputed that the period of declining inequality in many western countries after WWII has been followed by increasing dispersion in the distribution of incomes and wealth after what has been described as the big U-turn (Atkinson, 2015). Aside from an ongoing interest in the economic, social, and political origins of this development, there is a growing body of literature investigating the consequences of rising inequality, especially inequality of income (Van de Werfhorst and Salverda, 2012). Highly influential in this respect was Wilkinson and Pickett's (2010) “The Spirit-level”, which argues that inequality is the root cause of various “social dysfunctions” in rich democracies. Among others, income inequality has been argued to negatively affect (mental) health, crime and mortality rates, educational performance, social mobility, or economic growth (Kawachi et al., 1997; Wilkinson and Pickett, 2009; Stiglitz, 2012; Delhey and Dragolov, 2014; Layte and Whelan, 2014; Delhey et al., 2017; Hertel and Groh-Samberg, 2019; Delhey and Steckermeier, 2020). Wilkinson and Pickett's “inequality thesis” states that, from a certain level of economic development, persistent and rising inequality becomes paramount for social well-being. Theoretically, they link inequality to adverse social outcomes through a social-psychological mechanism involving increasing status concerns and decreasing social trust, and so this has also become known as the “social-psychological theory of inequality” (Buttrick and Oishi, 2017).

The consequences of rising income inequality may go beyond the social dysfunctions listed above. Described as a “powerful social divider” (Wilkinson and Pickett, 2010), the question arises whether the growing dispersion of incomes can be related to the broader phenomenon of social and political polarization that seems to plague our contemporary societies. In order to contribute to this debate, this study addresses the question of whether inequality erodes trust in the core institutions of representative democracy (parliament, parties, politicians). More specifically, we aim to establish whether and how income inequality affects political trust in liberal democracies.

Political trust is a central concept in the social sciences and key to understanding how citizens relate to the state. In this study, we situate political trust in the more general conceptual framework of political support as initially developed by Easton (1965) and reformulated by Norris (2011). From this perspective, political trust is understood as an indicator of regime support and operationalization of the “internal axis” or “subjective dimension” of democratic legitimacy (Norris, 2017; Pennings, 2017; Van Ham et al., 2017; Fuchs and Roller, 2019; Wiesner and Harfst, 2022). Seen in this light, this study is concerned with whether income inequality threatens the very foundations of democratic stability.

There is a long tradition of political theorizing about how democratic legitimacy may be undermined through the inherent conflict between the ideal of political equality and the inequality produced by market outcomes (Dahl, 1971). A similarly classical argument in political sociology states that both the level and distribution of economic resources determine the nature of distributional (and hence political) conflict, making economic prosperity and low levels of economic inequality a precondition for democratic stability (Lipset, 1959a). Yet, while the number of studies on the relationship between macroeconomic contexts and political trust have increased remarkably in the past two decades (see Van Der Meer, 2018, for a review), comparatively few studies investigate the relationship between trust and income inequality. And while most studies document a negative effect of inequality on trust or related indicators of political support (Andersen and Curtis, 2012; Donovan and Karp, 2017; Goubin, 2020; Goubin and Hooghe, 2020), others remain more skeptical (Magalhães, 2014). In addition, most studies to date rely on cross-sectional data only, which evidently makes drawing inferences on how changes in inequality affect changes in political trust problematic. For these reasons, the evidence so far remains inconclusive and warrants a re-investigation.

The current study contributes to this literature by providing new empirical evidence on the sociotropic (i.e. contextual) relationship between objective income inequality and political trust. Applying a set of random-effects-within-between (REWB) models to time-series-cross-section data from nine rounds of the European Social Survey, this study offers further insight into the relationship between income inequality and political trust by discussing its cross-sectional and longitudinal variants. In substantive terms, this may shed light on whether what matters for political trust are long-standing differences in levels of inequality between countries (between effects), or changes in inequality over time (within effects). The analyses reveal remarkable divergence between the within and between effects of inequality, suggesting that one should be skeptical with respect to drawing inferences based on cross-sectional associations alone. Nonetheless, the results document that inequality has both a negative between and within effect on trust. This sociotropic effect of changes in inequality on changes in political trust lends support to notions of a causal role of inequality for political trust. However, and in contrast to the Spirit-level proposition, rising inequality affects trust more negatively when overall economic prosperity is low. In addition, this study is the first to examine whether the social-psychological theory of inequality applies to political support by examining whether status concerns and social trust can plausibly account for the observed relationship between political trust and inequality. The findings lend support to the spirit level notion of a social-psychological transmission channel, albeit with limited explanatory potential: A small part of the association between political trust and inequality can indeed be explained by social trust and status concerns. Nonetheless, as shown by a comparison with evaluation-based processes as captured by evaluations of economic performance, social-psychological mechanisms play a minor role at best.

The remainder of this article proceeds in three parts: The following section starts with a brief introduction to the conceptual framework and main theoretical accounts of political trust before the arguments relating trust to inequality are discussed in more detail. A concise overview of the literature is presented in order to develop a set of falsifiable hypotheses. Section 3 describes the data and methods, whereas section 4 presents findings from the exploratory analysis and the multilevel models. The article closes with a discussion of the findings and concluding remarks on their implications.

Political trust, generally defined as the “faith that citizens place in political actors and institutions not to act in ways that will do them harm” (Hakhverdian and Mayne, 2012; p. 740), is a central concept for scientific inquiries of how citizens relate to the political system (see Zmerli and van der Meer, 2017, for an overview of the long lasting concern with political trust).

In order to clarify further how empirical studies of political trust relate to the question of democratic legitimacy, it is useful to adopt the distinction between an external and internal axis of legitimacy as proposed by Wiesner and Harfst (2022) in the current special issue.1 Most generally, legitimacy can be defined as “the normative justification of political authority” (Thomassen and van Ham, 2017; p. 6). The external axis of legitimacy refers to whether political systems comply with democratic values. While this is primarily measured by expert assessments as to whether political regimes operate according to standards implied by different models of democracy (e.g. liberal, social democratic, deliberative, etc.), it also entails what has been termed “formal legitimacy” in the sense of the legal validity of the procedures by which power is acquired and exercised (Beetham, 2003; p. 14). The internal axis of legitimacy, on the other hand, refers to subjective or informal legitimacy and as such to the popular acceptance of and consent with authority (Wiesner and Harfst, 2022, see also Gilley, 2009; Krause and Merkel, 2018). Following Fuchs and Roller (2019), subjective legitimacy can further be distinguished in two levels: At the first or higher level, subjective legitimacy occurs when citizens are committed to democratic values and principles, that is, when they value democracy as such. At the second level, subjective legitimacy refers to the perception of the performance of democracy in the country in question.

The subjective requirements of democratic stability are of central concern within the “political culture” research tradition (Lipset, 1959b; Almond, 1963; Easton, 1965). From this perspective, the stability of a democratic system hinges on the congruence between its democratic political structure and the values and attitudes of its citizens that in the aggregate constitute its political culture. Central to this research is David Easton's (1965; 1975) conceptual framework of system support and the differentiation between distinct levels and objects of political support (authorities, the regime and the political community). In contrast to the more transient specific support that captures attitudes based on rational evaluations of specific policies or incumbents, it is the more affective and general diffuse support that provides the ‘reservoir of favorable attitudes or good will” (Easton, 1975; p. 444) that is essential for stability.

In Easton's classical conceptualization, trust is one of the main expressions of diffuse support (alongside legitimacy beliefs, see Easton, 1975). Contemporary studies of political trust usually follow Norris' (2011; 2017) reformulation of Easton's framework, which arranges the components of political systems along an attitudinal continuum from most diffuse to most specific.2 Political trust is most commonly understood as the most specific level of regime support. As a “middle range” indicator (Listhaug and Wiberg, 1995), it is more diffuse, i.e., affective or generalized, than the approval of incumbents or specific policies, but also more specific and evaluative than the approval of democratic norms and principles or emotional attachments to the nation-state. The focus of this study, trust in the core institutions of representative democracy (parliament, parties, politicians), can thus be seen as one indicator of support for the political regime. It therefore captures only one aspect of the broader concept of political support, for which an investigation would require an expanded set of indicators (see also Schäfer, 2013).

It follows that low or declining levels of trust in the institutions of representative democracy are not synonymous with eroding support for democratic principles, and even less with declining legitimacy in the sense that legitimacy refers to a high degree of both formal/objective and informal/subjective legitimacy. An empirical study of political trust can also not comprehensively capture the degree to which a regime has subjective legitimacy. Nevertheless, trust is generally regarded as a “precondition for effective democratic rule” and an essential “pro-democratic value” (Van der Meer, 2017). Because political trust is also strongly associated with other indicators of political support, such as support for democracy as an ideal (Mishler and Rose, 2005), it is one (very) important proxy for subjective legitimacy (understood as described above). By restricting the analysis to a sample of European liberal democracies that assume formal legitimacy according to expert measures, this study of whether income inequality depresses political trust amounts to a study of whether rising inequality has the potential to shift fully legitimate systems to subjectively illegitimate systems (Wiesner and Harfst, 2022; p. 8). Put differently, we follow others in regarding a loss of trust as an indication of at least a challenge for, if not a more underlying problem of, democratic legitimacy (Van Ham et al., 2017).

From a broader perspective, low and declining levels of political trust may be seen as one dimension of “social dysfunction” that is caused by increasing inequality (Wilkinson and Pickett, 2009). Indeed, persistent or rising economic inequality has time and again been described as one of the greatest challenges facing democracy in the 21st century (e.g., Jacobs and Skocpol, 2005; Polacko, 2022).

Democratic theory warns us that inequality is at odds with the premises and promises of liberal democracy (Dahl, 2000, 2006). The latter rests on the premise of intrinsic equality - the idea that every human being is fundamentally equal and that therefore, the interests of members of a democracy are of equal importance. In principle, democracy then promises equal respect for every person's needs and interests, a promise enshrined in the slogan “one person, one vote”. If income inequality translates into political inequality by increasing unequal participation (Solt, 2008) and unequal political responsiveness (Elsässer and Schäfer, 2023), rising income inequality can potentially lead to what has been described as “double alienation” (Schäfer and Zürn, 2021): Political institutions move further away from the ideal of political equality, and as a consequence, citizens turn away from a political system they perceive as unresponsive to their needs and as no longer working in their interests (Goubin and Hooghe, 2020). Such is the core argument underlying most studies of inequality's effect on political support: As inequality rises, people realize that said democratic promise is broken and become increasingly dissatisfied and distrusting (e.g., Donovan and Karp, 2017; Goubin and Hooghe, 2020).

And indeed, there is a clear negative correlation between the overall level of political trust and the overall level of income inequality (as measured by the Gini coefficient of disposable household income), as shown in Figure 1. By now, several studies have documented a negative association between inequality and various indicators of political support with multivariate models, and for a wide range of countries: Anderson and Singer (2008) find a detrimental effect of inequality on trust in politics in 20 European countries, Zmerli and Castillo (2015) find the same for Latin America, and Andersen and Curtis (2012) come to a similar conclusion using data from the World values survey. While most studies report a negative effect of income inequality (Anderson and Singer, 2008; Andersen and Curtis, 2012; Schäfer, 2013; Krieckhaus et al., 2014), others remain more skeptical as to whether objective macroeconomic income inequality can be linked to political support (Magalhães, 2014; Kim et al., 2022).

Figure 1. The correlation between income inequality and political trust in Europe (2002–2018). Author's calculations based on ESS (rounds 1–9, N = 339, 866) and SWIID. ESS design weights applied.

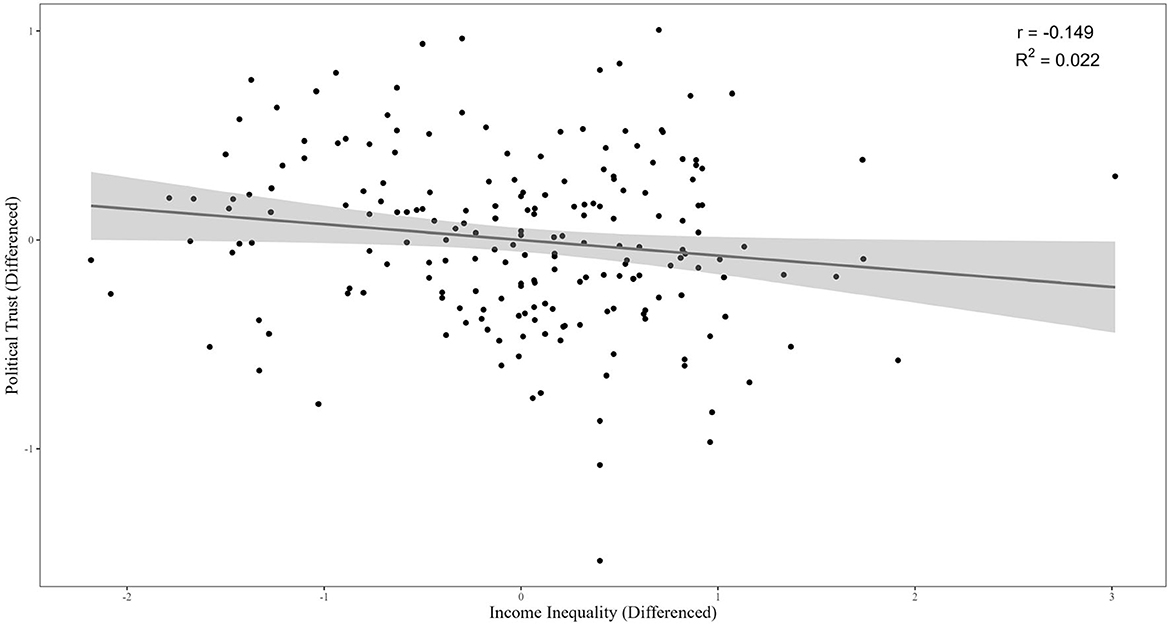

An obvious source of these inconsistent findings is the study design. Most studies to date are, just as Figure 1, based on a comparison between countries. Because these only rely on variation between countries, drawing inferences on how changes in inequality affect changes in trust is highly problematic. Even more so because numerous other country-characteristics potentially affect both the level of trust and inequality in a country. The problem of unobserved heterogeneity thus makes it difficult to ascertain any causal role of inequality. In light of these issues, it is preferable to look at the variation over time. That the relationship between countries might not be the same as the relationship over time becomes evident once we look at Figure 2. The axes now show mean-differenced variables or the score in a survey-year relative to the country's overall average (across years). For example, the x-axis indicates the difference between a country's level of income inequality in a certain survey round from its over-time average. The plot thus shows the bivariate ‘within' association of trust and inequality, the degree to which the two variables co-vary within a country, between survey-years. The average within-relationship is clearly much weaker than the between-relationship shown in the equivalent Figure 1 above. The correlation coefficient (r = −0.165) and coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.027) are also much lower. Still, the negative regression slope and correlation coefficient are in line with the expectation of a positive change in inequality within a country being associated with a negative change in that country's average level of political trust.

Figure 2. Average within-correlation: mean-differenced political trust and income inequality scores. Author's calculations based on ESS (rounds 1–9, N = 339, 866) and SWIID. ESS design weights applied.

Only few studies so far apply a longitudinal design and investigate the effect of changes in inequality on changes in political support. While those generally find more consistent negative effects on political trust (Goubin and Hooghe, 2020) and the related concept of satisfaction with democracy (Christmann, 2018), others find no or inconsistent effects (Sirinić and Bosancianu, 2017; Martini and Quaranta, 2020). The commonality of the longitudinal approach notwithstanding, these differences may once again lie in the difference in study design and consequently, in the type of question these studies can answer.

Without going too much into the methodological details, the question whether income inequality affects political trust can be asked in three different ways. First, one can be interested in the question whether the relationship between income inequality and trust is due to individual differences in incomes. It is well established that people in higher socioeconomic positions have higher levels of trust in politics, which is often interpreted in terms of ‘pocket-book reasoning' (and also known as an egocentric effect, see Polavieja, 2013). If individual differences in socioeconomic position are related to differences in trust, the relationship between income inequality and political trust may well be the result of compositional differences in individual socioeconomic positions.

A second type of question asks whether differences in contexts affect some individual-level processes. Here, the focus is on the relationship between trust and individual characteristics, but one expands by exploring whether that individual-level relationship differs between contexts. The argument would be that the relationship between individual characteristics (e.g., socioeconomic status, political orientation, or electoral status) is stronger or weaker in more unequal contexts (for examples, see Anderson and Singer, 2008; Zmerli and Castillo, 2015; Goubin, 2020; Goubin and Hooghe, 2020; Martini and Quaranta, 2020).

The third type of question differs from the second as it focuses explicitly on the contextual level. Here, the question is whether there is an effect of inequality above and beyond the effect of individual socioeconomic positions. Put differently, the question thus becomes whether people in more unequal contexts express less trust in politics, independent of their own socioeconomic position. If a relationship between trust and contextual inequality can be established after taking into account individual differences in socioeconomic status, this amounts to a sociotropic effect of inequality. Importantly, taking into account the individual differences in socioeconomic status amounts to controlling for compositional differences between contexts; the comparison of interest becomes that between a context in which inequality is high and a context with low inequality.

The type of question asked then determines the methodological decisions. Importantly, the methodological focus of the second type of question is still on the individual-level processes (Enders and Tofighi, 2007). Goubin and Hooghe's (2020) design is one that answers this type of question, as they provide estimates of inequality's effect on the individual-level relationship between socioeconomic status and trust. In order to study whether the gap in trust between people in different socioeconomic positions is larger in more unequal countries, they (correctly) center the individual-level variables within survey-years. However, this type of research design does not address the question of whether there is a sociotropic effect of macroeconomic income inequality on trust. In order to provide the answer to this kind of question, one needs to account for differences in socioeconomic characteristics that exist between individuals in different countries. That is, if one is interested in a genuine contextual effect of inequality on political trust, one needs to control for compositional differences between contexts. Compositional effects are, however, not controlled for if the individual-level variables are centered within survey-years or countries (see Enders and Tofighi, 2007). Against this background, it seems important to reconsider if there is a genuine sociotropic relationship between income inequality on trust, and if this is the same whether we look at a cross-sectional or longitudinal relationship. The corresponding hypotheses can be stated as follows:

H1: The higher a country's overall level of inequality, the lower is its overall level of political trust (between-effect).

H2: An increase in a country's level of income inequality over time is associated with a decrease in that country's average level of political trust (within-effect).

The influential “spirit-level thesis” (Wilkinson and Pickett, 2010) implies an important qualification to the long-standing political sociological argument that the level and distribution of economic resources are a precondition for democratic legitimacy (e.g., Lipset, 1959a). While their social-psychological theory of inequality is more broad and not specifically about political attitudes, it provides a general theoretical framework for understanding the potentially negative consequences of income inequality in prosperous democracies. Seen in this light, trust in institutions may be seen as one sub-dimension of 'social dysfunction' that ranges from teenage pregnancy to mental health problems for which persistent and rising income inequality are thought to be the root cause. Wilkinson and Pickett (2009, 2010) have argued that the distribution of economic resources becomes particularly relevant for social wellbeing once a certain level of economic development is achieved. In other words, in rich countries, income inequality is more important than rising prosperity per se. It follows that inequality should have a more detrimental effect on institutional trust in countries that have already comparatively high levels of economic prosperity (see also Layte, 2012).

H3: The negative effect of income inequality on political trust is more pronounced in countries with higher levels of GDP per capita.

The spirit-level thesis also contains a theoretical argument for how inequality leads to negative social outcomes. In the following, we will describe this social-psychological theory of inequality in more detail and how this perspective links macroeconomic income inequality to political trust. we thus propose the social-psychological mechanism as an alternative to the more established evaluation-based mechanism that currently dominates the political support literature (see Van Der Meer, 2018). As described in more detail below, the now dominant perspective views trust as resulting from a rational evaluation of political outcomes, based on expectations and preferences. A comparison of the two alternative transmission channels from inequality to trust as depicted in Figure 3 should shed light on the plausibility of an extension of the social-psychological theory to the realm of political support.

The social-psychological theory regards income inequality as an indicator for the degree of status differentiation in a society. Accordingly, income inequality affects all outcomes that have a social gradient, i.e., outcomes that systematically differ across social groups according to their position in the social stratification. Wilkinson and Pickett (2010) propose two key pathways through which inequality leads to what they term ‘social dysfunction': Social trust and status anxiety (see also Buttrick and Oishi, 2017; Delhey and Steckermeier, 2020).

Rothstein and Uslaner (2005, p. 45) describe social trust as what “links us to people who are different from ourselves”. Higher income inequality implies greater social stratification and a higher degree of status differentiation in society. It has been argued that higher income inequality can therefore result in greater differences between the social worlds, resulting in fewer contacts across status groups and, consequently, fewer shared interests. As “a powerful social divider” (Wilkinson and Pickett, 2010; p. 51), income inequality would thus depress inter-group contacts, which are, from a social capital perspective, an important determinant of generalized social trust (Putnam, 2000). On the other hand, social trust is often seen as an important determinant of political trust (Delhey and Newton, 2005; Newton et al., 2018). It follows that increased social distances and concomitant lower social trust can be expected to result in lower political trust. Macroeconomic inequality may therefore affect political trust indirectly, via its negative effect on social trust.

In addition, the social-psychological theory states that economic inequality produces adverse social outcomes because greater status differences lead to increased status competition, which result in perceptions of social-evaluative threat and status anxiety. Since an increase in income inequality stretches out the distances between status groups, one's position in the status order becomes ever more relevant. According to the theory, social comparisons and status competition become more prevalent, which increases social-evaluative stress (Wilkinson and Pickett, 2010, p. 33–44). Extant studies document “conspicuous consumption” to be higher in high inequality contexts (Walasek and Brown, 2015). Others show that people in countries with high inequality have higher levels of status anxiety (Layte and Whelan, 2014) and are more status seeking (Wang et al., 2019, but see Paskov et al., 2017). This may have implications for trust in institutions as well, not least because questions of status have become central to current explanations of political attitudes and behavior, especially of the rise of right-wing populism.

Although no study so far has linked inequality to political trust via status concerns, recent studies on populist voting lend support to this notion because populist voting is itself strongly determined by political trust (Ziller and Schübel, 2015). This line of research argues that rising income inequality is associated with rising concern for status, in particular the experience, perception, or fear of status decline, and that this explains the rise of populist and radical right parties in Western democracies (cf. Gidron and Hall, 2017). Rising income inequality has indeed been shown to lead to populist voting via what is essentially status anxiety (Engler and Weisstanner, 2021). Another study found that political trust mediates the effect of inequality on populist voting (Stoetzer et al., 2021). Taken together, this research suggests that income inequality may depress trust in political institutions via increased concern for status.

In sum, when we extend and redirect the social-psychological theory to political trust, the proposition becomes that macroeconomic inequality should affect political trust mainly via its effect on increased status concerns and lower social trust.

H4: Status concerns and social trust mediate the effect of income inequality on political trust.

To assess the plausibility of the mechanism suggested by the social-psychological theory of inequality, it may be compared to more established accounts that focus on evaluative mechanisms. The currently dominant perspective in political science, the trust-as-evaluation approach, views trust as the result of a rational evaluation of expectations against outcomes, whereby the political system must convince its citizens that the outcomes and outputs it produces meet their needs and demands (Polavieja, 2013; Van Der Meer, 2018).

From this performance-evaluation perspective, one can argue that citizens hold certain expectations toward the political system and its actors, and that combating inequality is one of those demands. This argument has been made by Goubin and Hooghe (2020, p. 2), who “assume that citizens hold the political system at least partly responsible for the level of inequality they experience or observe”. Similarly, Donovan and Karp (2017, p. 472) suggest that inequality is one of the “larger social forces that we also expect people to consider, perhaps more immediately, when they are asked about how elections and democracy are performing in their country.” Although this might be a rather strong assumption, one should bear in mind that European citizens have been described as “inequality-averse” (Delhey and Dragolov, 2014). Support for this argument comes from survey-based measures of democracy, which show that large parts of the public across European countries believe it is “essential for democracy” that the government takes measures to reduce income inequality and to protect citizens from poverty (Hooghe and Oser, 2018; Quaranta, 2018).

In this line of thinking, rising economic inequality indicates continuing failure to cater to the demands of citizens, which leads to negative evaluations of the political system's output performance that ultimately result in loss of trust. To test the plausibility of trust-as-evaluation perspective, we can examine the role of citizen's subjective evaluations of overall economic performance as an indirect test of whether the effect of income inequality on political trust is mediated by a mechanism of output performance evaluation.

H5: Economic evaluations mediate the effect of income inequality on political trust.

This study makes use of individual-level data from rounds 1 to 9 of the European Social Survey Cumulative File ESS 1-9 (2020) in combination with macro-level data from the World Bank's World Development Indicators Databank (WDI, 2022) and the Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID, Solt, 2020). The ESS is a cross-national survey that is conducted every two years on newly selected national probability samples in up to 35 participating countries. Not all countries that took part in the ESS were included in the analyses. In order to meaningfully estimate longitudinal associations, only those countries that participated at least twice were retained. As the analysis focuses on European liberal democracies, Russia, Ukraine, Turkey and Hungary were dropped as of their Freedom House (2022) status, whereas Israel was excluded for geographic reasons. The 28 countries remaining in the sample are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

To ensure that differences in parameters and coefficients of successive models were not due to differences in the samples (i.e., to ensure the models were based on the same data), respondents with missing answers on dependent or independent variables were dropped listwise. The samples used for the analysis were further restricted to respondents above the age of 18. The dataset covers 28 countries in total with a minimum of two surveys per country over a period of 16 years. The minimum number of countries in a single survey round is 18, and the number of country-surveys amounts to 200, with the analysis based on a total of 339,866 individual observations. Supplementary Table S1 summarizes the country-years and size of the national samples retained after listwise deletion. Supplementary Table S2 shows descriptive statistics for all variables used in the analysis.

The dependent variable political trust is measured by an index composed of three items asking for the respondent's trust in the national parliament, politicians, and political parties. The political trust index is constructed by taking the mean of the valid answers on these three items. This composite scale ranges from 0 (‘no trust') to 10 (‘complete trust') and captures confidence in the three institutions commonly referred to as the main pillars of representative democracy (e.g., Torcal, 2014). Besides the large body of published research operationalizing political trust in the same way (e.g., Anderson and Singer, 2008; Pennings, 2017) and studies attesting unidimensionality and partial metric equivalence of the political trust measurement in the ESS (Marien, 2011), the use of the composite scale is also justified by a Cronbach's Alpha of 0.91. A noteworthy side benefit the index has over a single item is the reduced number of missing answers on the dependent variable.

The key independent variable, income inequality, is measured by the Gini coefficient of disposable household income. This measure of inequality has a theoretical range from 0 to 100, where 0 describes a situation in which every household has the same share of the national income and 100 corresponds to one single household collecting all of the national income. The data are obtained from the Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID, Solt, 2020). The multivariate models use Gini values with a lag of one year, that is, the Gini in a given country-year corresponds to the Gini from the year before the ESS round.

This study employs the Rosenberg scale for generalized interpersonal trust (cf. Zmerli et al., 2007). The measure is an index composed of the average of the valid responses on three questions probing a respondent's belief in the general helpfulness, fairness, and trustworthiness of others. All three items were measured on 11-point scales ranging from 0 to 10, with higher values indicating a stronger belief in the presence of such qualities in others. The index equally ranges from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating higher levels of social trust. Cronbach's Alpha is 0.78 and can therefore be considered adequate for the construction of an index (Kline, 2016; p. 94).

Status concerns are measured by the “status-seeking index” (Paskov et al., 2017). It is a measure that is frequently used in social-psychological research to tap into the subjective importance of status, or “the heightened desire for esteem, respect and recognition in the eyes of others” (Paskov et al., 2017). The index is based on three items that are part of the ESS Human Values Scale that presents a list of different personality portraits and asks respondents to indicate how similar this person is to themselves. The three items included in the index indicate how important a respondent thinks it is to (1) get respect from others, (2) get recognition for own achievements, (3) show one's abilities and to be admired (see Supplementary Table S4 for details on question wording and measurement). The original answers on a 6-point scale were reversed. The mean of the valid answers was taken as the index score and within-person centered by subtracting the respondent's mean score across all human value items (Schwartz, 2003, p. 17). Higher scores on the index (Cronbach's α =.70) thus indicate a higher subjective importance of status relative to other values. 3

The ESS includes a question asking respondents how satisfied they are “on the whole with the present state of the economy” in their country. The answers are given on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (“Extremely dissatisfied”) to 10 (“Extremely satisfied”). As is common in the literature (e.g., Polavieja, 2013; Lühiste, 2014), the item is used in this study as a measure of subjective evaluations of economic performance.

Further covariates are employed at the individual and country-level of analysis. A first set of variables measures respondent's socioeconomic position. Education level was measured in four categories based on ISCED codes, distinguishing between “less than secondary”, “secondary”, “post-secondary, non tertiary” and “tertiary” education. Respondent's social class was constructed following the 5-point class schema by Oesch (2006), which distinguishes between “upper service class”, “lower service class”, “small business owners”, “skilled workers”, and “unskilled workers”. Respondents with missing data (7.55%) were captured in an additional category.

The analysis also employs a measure for net equivalized household income. The measure for household income differs between rounds of the ESS. In rounds 1 to 3, income is measured in country-specific categories, in later rounds it is measured in deciles of the national income distribution. To create a harmonized income variable, the lower and upper limits of the income brackets were obtained in Euro. For each country and survey year, an interval regression assuming an underlying log-normal distribution was performed. The resulting regression parameters were then used to simulate a distribution of incomes from which a random value was chosen for each respondent conditional on the limits of the respondent's score on the original income variable. The imputed incomes were adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index and equivalized using the square root of the household size. For the analysis, quintiles of the imputed continuous income measure were used, with an additional category for respondents with missing income information.

Further individual-level controls include age (in years), gender, and labor market status, where those in paid work are distinguished from unemployed persons and all others (mostly retirees and those in education).

At the country level, GDP per capita (log-transformed) is included as a standard measure of economic prosperity (WDI, 2022). It can be noted that, as a consequence of the model specification, the analysis also account for economic growth. That is to say, the longitudinal component of GDP per capita captures changes in GDP within a country relative to its overall level GDP.

The type of data used in this study - newly selected individuals from multiple years in multiple countries - has been termed comparative longitudinal survey data (CLSD) or repeated cross-sectional data (Fairbrother, 2014). CLSD can be regarded as consisting of three hierarchical levels, where individuals are clustered at the country-year, as well as at the country level. Respondents are thus treated as uniquely nested in country-years (or country-survey-rounds), which are again uniquely nested in countries. To clarify, clustering in this sense implies that individuals within one country-year may be more like each other than individuals of different countries, and respondents surveyed in one particular year and country may be more similar than respondents from the same country but a different year. This induces a natural dependency of the responses within each cluster and violates the assumption of independent errors. If the errors are correlated, ignoring the clustering will lead to a downward bias in the standard errors and, in consequence, to an increased Type-I error rate. To account for this, I use the general multi-level or random effects (RE) framework (Hox, 2010).

Within this broader framework of what is also known as mixed-effects, hybrid or hierarchical models, this study will fit a series of so-called Random Effects Within-Between (REWB) models. Based on works from Mundlak (1978), the within-between formulation has become an increasingly popular alternative to Fixed Effects (FE) modeling of CLSD, for which it is particularly suited as it allows the simultaneous analysis of both cross-sectional and longitudinal effects (Fairbrother, 2014; Bell and Jones, 2015; Bell et al., 2019). Specifically, cross-sectional effects (differences between countries) are distinguished from longitudinal effects (differences over time within countries) while also controlling for compositional effects and allowing for an investigation of individual-level determinants of the outcome.

The major advantage of the REWB over the otherwise often used Fixed Effects (FE) specification in the analysis of CLSD is that, instead of merely isolating a specific dimension of variation and ‘controlling away' the between-country heterogeneity, it specifically enables the estimation and modeling of between-coefficients. Analogous to the computation underlying the FE model, the REWB-specification makes use of mean-differencing to arrive at these estimates (Bell and Jones, 2015). Adopting the notation and formula from Schmidt-Catran (2016), the REWB model can be described as follows:

where yijk is the outcome for individual i in country-year j in country k, with constant β0 yielding the conditional average of y. The subscripts ijk refer to the different levels of analysis, so that v0k is the random residual at the third level associated with the intercept, or a country-differential from the overall mean of y. Similarly, u0jk is the random effect at the second level or the departure of a country-year from the overall country mean in y, and e0ijk is the residual at the individual level. The residuals or random effects vk, ukt, eijk are assumed to follow a normal distribution with mean zero and a non-zero variance.

β1...m denotes the coefficients corresponding to the individual level predictors x1..X, whereas γ denotes coefficients for contextual variables z1...Z. Time-varying contextual variables vary not only between countries but also between country-years (indicated by subscript kj). Hence, in order to distinguish between-country effects of z on y from within-country effects, the within-between formulation enters the covariate z (or multiple z, as indicated by Z) once as the country-average across all years for country k, estimating the time-invariant effect of, or the enduring country-difference in Z. This term is denoted as the between effect (). To capture the effect of variation in Z over time, it is entered a second time as group mean centered covariate (alias mean-differenced or centered within cluster, see Enders and Tofighi 2007). The term is constructed by subtracting the country's over-time average from the time-varying measurement for each country-year. The within effect [] is independent (uncorrelated) of the between effect and yields the effect of a change in Z relative to the country average on the dependent variable (see Fairbrother, 2014; Bell and Jones, 2015; Schmidt-Catran and Fairbrother, 2016). Importantly, this independence implies that the within effect is unaffected by any observed or unobserved time-constant confounders (or between-unit heterogeneity). Under the assumption that there are no other time-varying confounders, the within-effect therefore provides a plausible estimate of the causal effect of income inequality on political trust.

The analytical strategy consists of series of REWB models in different specifications. A first set of models investigates the contextual association between inequality and trust, as well as the interaction with GDP per capita. A second series of models includes the individual covariates in a stepwise manner. First to obtain an estimate of the genuine sociotropic effect of inequality and subsequently to assess whether this can be accounted for by the social-psychological or evaluative processes. The assessment of which of the processes explains the contextual association then revolves around observing changes in the coefficient for inequality (see Layte, 2012). The test for hypotheses 4 and 5 is thus provided by the question of how the relationship between inequality and political trust changes if the relationship between inequality and the mediator has been partialled out. In other words, we test for multilevel mediation by observing the difference between the total and the ‘net' effect (c−c′). The change in size and significance of the inequality effect will then serve as an indicator of the strength of the potential mediation.

All analyses reported in this study are conducted using R (R Core Team, 2020), with the REWB-models fitted using the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015). The multi-level models are estimated using Full Maximum Likelihood (FML) estimation, as this allows for the comparison of nested models using the likelihood-ratio test (LRT). Although FML has been shown to produce downward bias in the variance components (the random effects), the number of higher-level units is sufficiently large to assume that this bias is unimportant (Schmidt-Catran et al., 2019). This was verified by re-fitting the models using Restricted Maximum Likelihood estimation (REML).

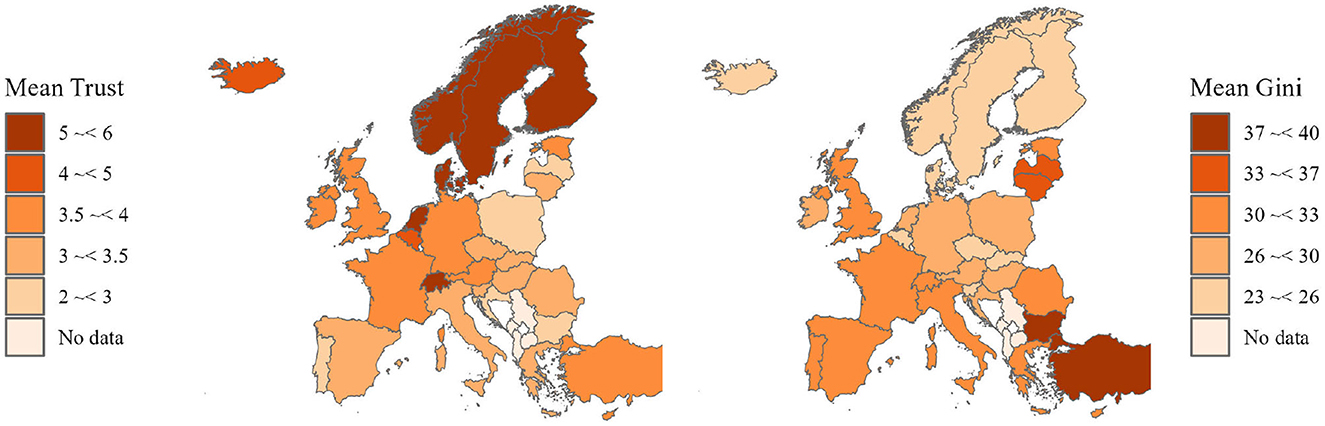

Figure 4 shows two maps of Europe. The left panel shows the average level of the political trust index for 2018 or the last available ESS round by country (including countries excluded from the main analysis). The panel on the right shows the level of income inequality, measured by the Gini coefficient of disposable household income in the corresponding year. While these plots are rather imprecise with respect to the level of trust and inequality due to the categorization, they help identify some broad patterns between countries.

Figure 4. Trust and income inequality in Europe. Author's calculations based on ESS (rounds 1–9, N = 510, 013) and SWIID. ESS design weights applied.

Beginning with political trust (left panel), these patterns echo what is known from the literature (e.g., Torcal, 2017): Comparatively high overall levels of trust are found in the Nordic (Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland) plus some Continental countries (Netherlands, Switzerland). The Southern and Central and Eastern European countries exhibit the lowest trust levels in the sample. In between are the remaining Western, i.e., Continental and Liberal countries. The right panel in Figure 4 shows marked differences between European countries in terms of income inequality. The Nordic countries, Belgium, as well as Czechia, Slovenia and Slovakia have Gini coefficients between 24.4 (Czechia) and 26.4 (Sweden). Among those with the highest income inequality are several Southern countries (Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain), Great Britain, Switzerland, the Baltics (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia). The most unequal country among those included in further analyses is Bulgaria with a Gini coefficient of 38.5.

Do the two panels in Figure 4 indicate an association between the overall levels of income inequality and political trust? There are some commonalities, such as the North-south divide, where the reverse coloring meets the expectation of high inequality pairing with low trust. However, the overlap is far from perfect. Obvious examples are Great Britain and Estonia, where political trust is higher than could be expected from their relatively high levels of inequality. Before turning to a more detailed exploration of questions of association, the following presents a brief description of how trust and inequality in Europe have evolved between 2002 and 2018. Note that the following analyses are based on the subset of country-years that is also included in the multivariate analyses.

Is it the case that the broad patterns observed in the panels of Figure 4 hide important changes in trust and inequality over time? Overall, this does not seem to be the case. Figure 5 shows the level of income inequality and trust for each country in each year of the ESS. While the relationship between both will be discussed in due course, a comparison of the position of countries between different panels reveals the trajectories of countries over time. For example, if we compare the datapoints for Great Britain in 2002 and 2018, we can see that both the Gini and the level of trust decreased over time. The panels show that both institutional trust and income inequality appear to be quite ‘sticky' during the 16 years under investigation: The average difference between the highest and the lowest level of trust within a country over this period was 1.08. For the Gini coefficient, this was 1.99. Although this indicates stability in general, some countries experienced substantial changes in these measures. In Greece, average trust dropped by 2.42 points from 4.15 to 1.73 between 2002 and 2010. Cyprus also experienced a decrease of 2 points in trust from 4.8 in 2006 to 2.8 in 20012. In other countries, these differences were more modest. In terms of changes in country-wide income inequality, those experienced by Bulgaria, Slovakia and Denmark can be considered substantial: Bulgaria saw an increase of income inequality from 33.3 in 2006 to 38.5 in 2018. Denmark also became more unequal over the period (from 22.9 in 2002 to 26.3 in 2018), whereas Slovakia's Gini coefficient in 2004 was at 26.7 and decreased to 23 in 2018 - a decrease of 3.7 points. According to these data, Slovakia became much more equal over the course of 16 years, resulting in it being the most equal country in the sample in 2018. Another notable example of declining inequality is Spain, where the Gini declined from 33.6 to 30.05 in 2018.

Figure 5. Trust and income inequality by country and year. Author's calculations based on ESS (rounds 1–9, N = 339, 866) and SWIID. ESS design weights applied.

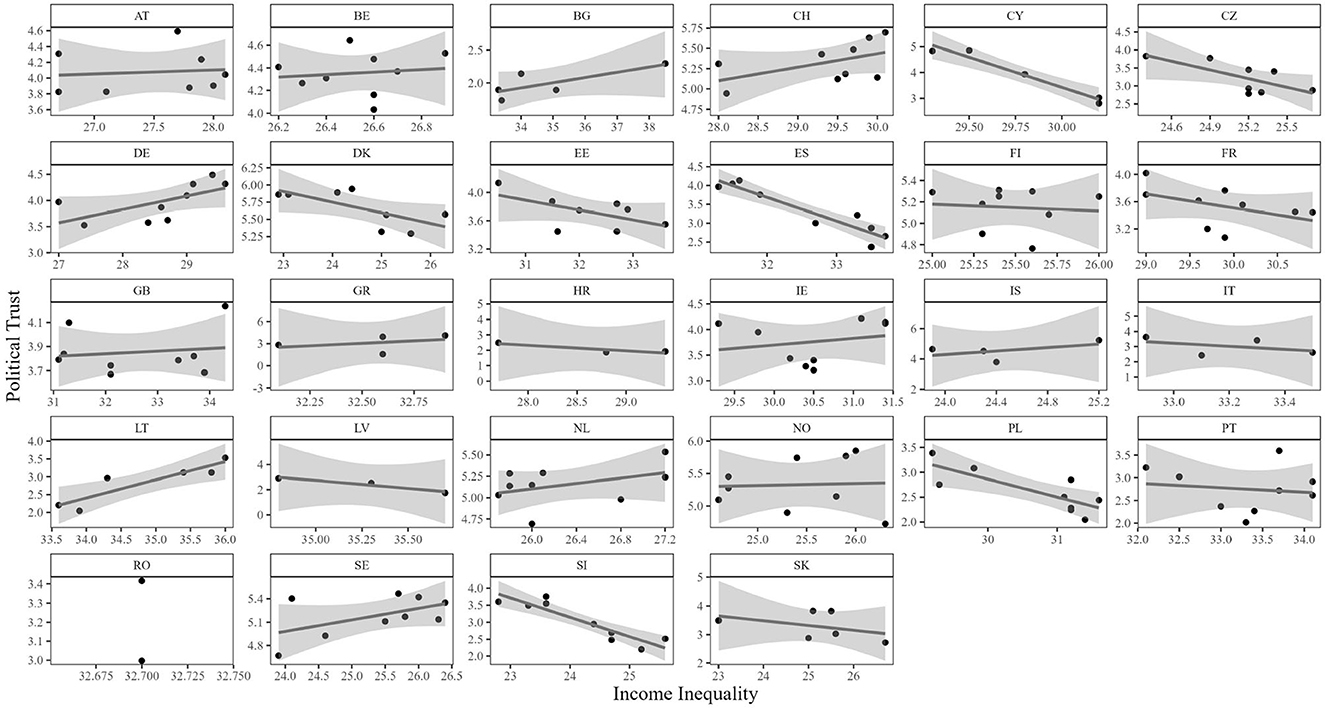

Moving on to an exploratory analysis of the hypothesized relationship between income inequality and levels of political trust, we can again look at Figure 5. The correlations in each year are in line with the expectation that inequality and political trust are negatively related. In addition, this cross-sectional relationship is also quite stable over time, ranging from r = −.453 (in 2006) to r = −.681 (in 2016). In contrast to Figures 5, 6 shows the relationship within countries over time. Here, we plot the level of income inequality on the x-axis and the average political trust on the y-axis for a particular ESS round within each country and add a line of best fit. In a number of countries, the relationship meets the expectations: The regression slope is evidently negative in 12 out of 28 panels. However, the other 16 countries exhibit a very small relationship between trust and inequality (a straight line), if not a positive slope. In contrast to the between relationship in Figure 5, which was very stable between survey years, the within-relationship between income inequality and trust seems to vary a lot from country to country.

Figure 6. Within-correlation trust and income inequality. Author's calculations based on ESS (rounds 1–9, N = 339, 866) and SWIID. ESS design weights applied.

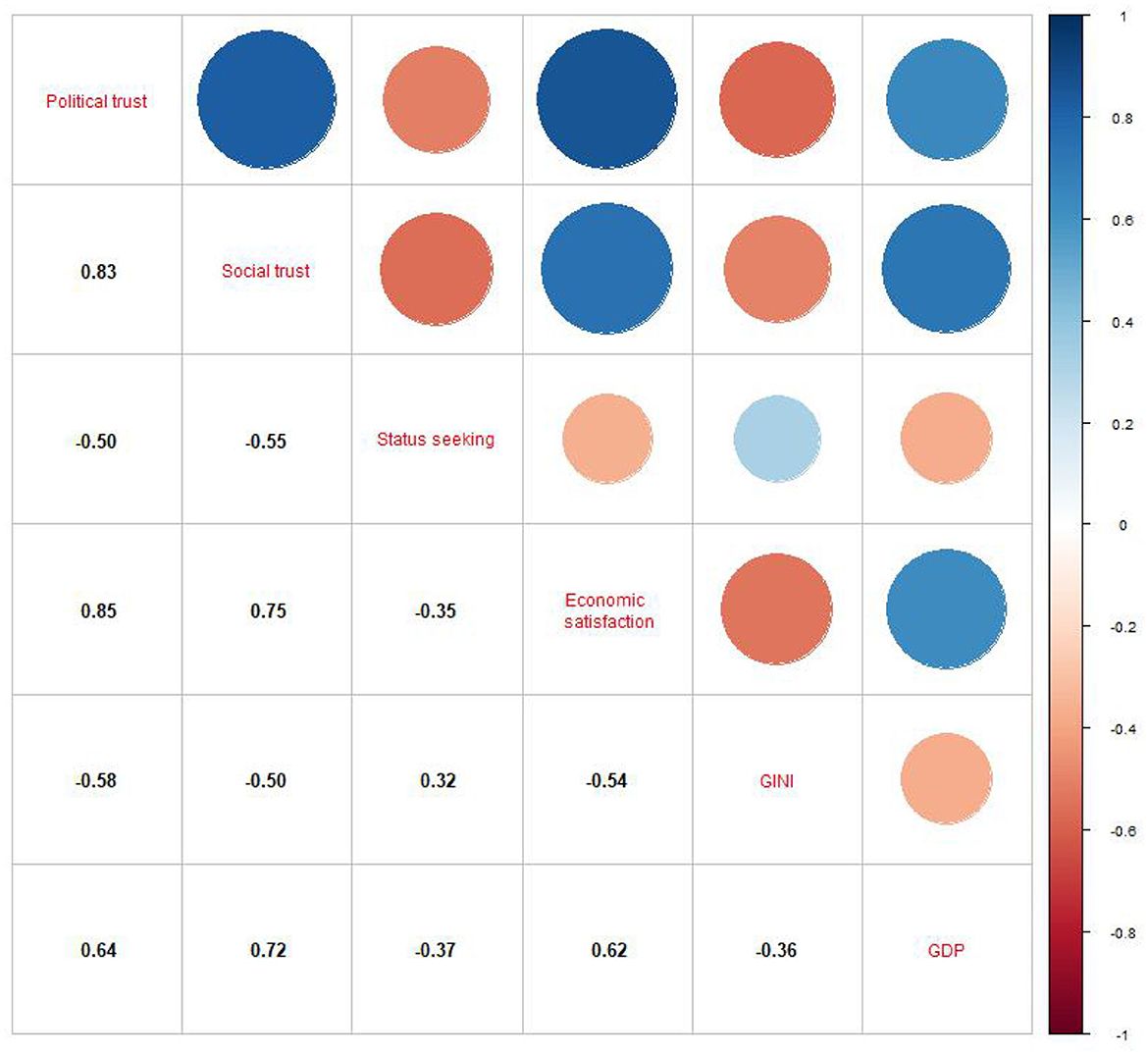

Before turning to the multivariate analysis, it is also useful to provide some descriptive statistics on the associations between inequality and political trust on the one hand, and the proposed mediating variables on the other. To this end, Figure 7 shows the correlations between the key variables, that is, political trust, income inequality, social trust, status seeking, sociotropic economic evaluations, and GDP per capita (log). Social trust and economic satisfaction are strongly related to political trust, whereas the correlation of status concerns with political trust is weaker. GDP per capita is a stronger correlate of political trust than income inequality (Gini). Furthermore, the correlations between income inequality and the potential mediating mechanisms are in line with the expectation that high inequality is associated with lower social trust and economic satisfaction, but higher status seeking.

Figure 7. Correlation heatmap. Correlation heatmap of political trust and selected variables. Correlation between country-year scores, with aggregated individual-level variables (design weights applied). Author's calculations based on ESS 1-9.

The main insight to be taken from the descriptive statistics presented so far is that the within and between relationships of income inequality and political trust may not be the same. The substantial divergence between countries in how trust and inequality have co-varied over time is masked when only cross-sectional relationships are inspected. In several countries, trust did in fact decline while inequality increased, yet there are several countries in which inequality rose at the same time as political trust increased. Further investigations are therefore warranted, and it is to this end that we now turn to the multivariate analysis.

Table 1 shows selected results from a series of REWB models (the complete regression results are shown in Supplementary Table S3). Before interpreting these results we briefly report on the Null- (random intercept) model, which decomposes the total variance of political trust into its different components (results available upon request). 19.3 percent of the total variance are situated at the country level, 3.6 percent are situated at the country-year level and 77.2 percent at the individual level. In other words, most differences in political trust are found between individuals and between countries, whereas only 3.6 percent of the total variance can be attributed to factors that vary within countries over time.

Model 1 regresses political trust on income inequality, controlling only for period effects. The regression coefficients show a negative “bivariate” association between inequality and political trust. The between term indicates that when the overall level of income inequality in a country is higher, the overall level of political trust is lower (Gini [BE] = −0.181, p < .001. The within term shows that when a country becomes more unequal relative to its overall level of inequality, or in other words, when inequality rises within countries over time, political trust decreases (Gini [WE] = −0.073, p = 0.058 ). Model 2 includes GDP per capita as country-level control to provide an estimate of the contextual association between inequality and trust while controlling for the most important potential confounding variable. Both the between and within term of GDP have a strong positive association with trust and the terms for inequality are reduced considerably. The between term of income inequality (Gini [BE]) is reduced to −0.081 (p < .05), whereas the within term (Gini [WE]) is reduced to −0.036, (p = 0.299). Model 3 tests the hypothesis that the effect of inequality depends on the overall level of economic prosperity in a country by including an interaction between the within coefficient of inequality and the between coefficient of GDP per capita. The main effects and the interaction term are statistically significant, but the direction differs from what was expected: Apparently, the effect of rising inequality is more negative when the overall level of GDP per capita is lower. Conversely, a high level of economic prosperity ‘buffers' the negative effect of inequality on trust.

Model 4 introduces the (uncentered) individual level control variables and thereby accounts for compositional differences related to age, gender, labor market status, disposable household income, social class, and level of education. Compared to the null model, the country-level variance is reduced by 78.66 percent and that at the country-year level by 25 percent. Model 4 presents estimates for the genuine sociotropic effects of income inequality on political trust that can serve as a baseline against which the proposed mediating processes can subsequently be evaluated. Net of the compositional effects and the macro-level controls, there is a statistically significant negative between effect of income inequality (Gini [BE] = −0.071, p < .05). Substantially, this indicates that citizens in countries in which economic resources are distributed more unequally have lower trust in democratic institutions, independent of the overall level of economic resources or their own socioeconomic characteristics. The terms associated with changes in inequality over time remain significant as well. To illustrate this conditional sociotropic within effect, Figure 8 shows the predicted values of political trust for Model 4. These predictions show the expected change in political trust for different values of within country changes in income inequality and for the empirical minima and maxima of overall GDP per capita (log). The x-axis shows the within term of inequality, that is, the Gini in a given country and year expressed relative to the overall level of inequality in a country. More positive values thus indicate a stronger increase in inequality over time (empirical range: -2.45 to 3.44). The plot shows a clear negative slope for within country changes in inequality for the low GDP country (the GDP corresponds with that of Romania in the sample), whereas the slope is even slightly positive when overall prosperity is high (GDP per capita corresponding to Norway in the sample).

The next analytical step is the exploration of potential explanations for the association between inequality and trust. Model 5 introduces social trust and status seeking as variables capturing the social-psychological mechanisms. A Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) indicates a significant improvement in model fit (χ2 = 35137.15; df = 2; p < .001). Compared to Model 4, the inclusion of two variables further reduced the country-level variance by 7.3 percentage points and that at the country-year level by 3.65. The variance at the individual level is reduced by 9.61. The marginal R2 indicates that the fixed effects in this model explain about 24 percent of the total variance in political trust, an increase of 8 percentage points compared to Model 4. When it comes to accounting for the effect of inequality, the inclusion of both terms reduced the between effect of inequality by .1, indicating that social-psychological mechanisms can account for 14.3 percent of the association between income inequality and political trust between countries. The main effect of the within term is reduced by .12 points (or 4.8 percent) and the interaction term by .01 (4 percent).

Model 6 tests the evaluation-based mechanism, captured by satisfaction with economic performance. This model has a significantly better fit than Model 4 (χ2 = 65964; df = 1; p < .001) and Model 5 (see AIC, BIC and R2). The model explains 89.09 percent of the variance in political trust scores at the country-level, 56.24 percent of the variance at the country-year level, and 19.37 percent at the individual level. The inclusion of economic evaluations accounts for 71.4 percent of the sociotropic between effect of inequality and 97.6 (main effect) and 100 percent (interaction term) of its within effect. Once economic evaluations are taken into account, there is no statistically significant effect of inequality. Substantively, this indicates that the contextual effect of inequality and trust is largely due to larger segments of the populations having negative evaluations of the country's economic situation as a consequences of higher income inequality.

Rising inequality has been described as one of the greatest challenges for democracy in the 21st century. According to the spirit-level thesis, income inequality is more important for societal well-being in affluent countries than rising prosperity per se. Against the background of a long tradition of political theorizing about the potential of economic inequality to erode democratic legitimacy (e.g., Lipset, 1959a; Dahl, 2006), the question arises whether spirit-level thesis can help us understand the “democratic malaise” of declining citizen support for democracy that so many observe (e.g., Foa et al., 2020).

The current study re-investigates this proposition by focusing on the question of whether income inequality erodes trust in the institutions of representative democracy. As a key indicator of political support, political trust can be seen as capturing the subjective dimension or internal axis of legitimacy (Wiesner and Harfst, 2022). Although trust in institutions is but one aspect of broader concept of political support, the often theorized corrosive potential of inequality for democratic legitimacy and stability should arguably be visible in declining trust in democratic institutions.

To this end, the current study used time-series cross-section data from nine rounds of the European Social Survey, covering a period of 16 years for 28 European liberal democracies. By applying a series of random effects within between models, the study expands on the previous literature that is still predominantly based on cross-sectional methodological designs. The results corroborate prior findings that income inequality and trust are negatively related. Importantly, the analyses reveal a genuine sociotropic effect of income inequality that exists above and beyond the effects of individual socioeconomic positions. Furthermore, both long-standing differences in income inequality between countries, as well as changes in inequality over time within countries, are negatively associated with trust in democratic institutions. With regard to the longitudinal association, the results indicate that the effect of within-country changes on changes in political trust is conditional on the overall level of economic prosperity. Yet, as opposed to what was expected from the spirit-level thesis, the effect is stronger in countries with lower levels of GDP per capita. Rather than countries with higher overall economic prosperity being particularly afflicted by the negative consequences of rising income inequality, prosperity seems to buffer the negative effect.

The spirit-level thesis receives more support when it comes to its explanation for how the effect of income inequality is transmitted. By examining the role of social trust and status concerns in the causal chain from inequality to political trust, this study provides a first test of whether the social-psychological mechanisms proposed by the spirit-level thesis applies to explanations for democratic support. While the social-psychological mechanism accounts for some of the observed effect of inequality, it plays only a minor role in comparison to the more standard evaluation-based processes that can be captured by satisfaction with economic performance. When these evaluations are included, the effect of income inequality becomes statistically insignificant. It seems that inequality matters for how citizens view their representative institutions because they take the distribution of economic resources into account when they evaluate the state of the economy. This findings corroborates previous studies that show that subjective economic evaluations mediate the effect of inequality (Christmann, 2018) and lends further support to the trust-as-evaluation approach (Van Der Meer, 2018).

While these are relevant findings, a number of limitations remain. Although this study made use of a more extensive data set and a more extended time-period than many previous studies, most substantial changes in inequality happened before the period under investigation. Future studies should re-investigate this question using a longer time-span, potentially even harmonizing existing survey data to go back in time. This study was also limited to European liberal democracies, which have comparatively low levels of income inequality. Future studies should re-investigate the relationship between income inequality and political trust with a more diverse set of countries.

Furthermore, the analysis of the mechanisms relating inequality to trust was limited to the set of indicators available in the repeated core questionnaire of the ESS. The analysis therefore remained exploratory and should not be seen as an ultimate answer to how inequality affects political trust, in particular with respect to the role of status concerns. Theory suggests that it is evaluative stress and perceptions of (or fear of) status loss or inferiority that would lead to loss of trust, yet these dimensions of status concerns may not be captured by the status seeking index. While status seeking was the only viable option to proxy status concerns in the context of this study, this measure is not optimal, not least because the underlying items were originally developed to measure value orientations. While previous research suggests that macroeconomic inequality affects status seeking (Paskov et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2022), value orientations are frequently assumed to be relatively stable (Schwartz, 1992, but see Lersch, 2023). In light of these limitations, the results of the current study should be interpreted as a first, not the final test of the social-psychological mechanism. When cross-national comparative panel data with the relevant items become available, future studies may revisit the interrelationships between inequality, status seeking and political trust. Data limitations also prevented the differentiation between different evaluations. Although it is plausible that income inequality matters for political support mostly due to its effect on economic output evaluations, the indicator might also be a sort of ‘catch-all item' capturing satisfaction with a broad range of factors. Future studies should aim at disentangling what perceptions macro-economic inequality affects, possibly linking this to an investigation of other potential mediators, such as perceptions of political efficacy or evaluations of political responsiveness.

Despite these limitations, this study makes important contributions to the literature on political support and to our understanding of the negative consequences of income inequality. This study finds support for the dominant evaluation-based accounts of the association between macroeconomic outcomes and political trust, but also points toward the benefit of broadening our perspective by incorporating social-psychological theories of inequality. Moreover, the new empirical evidence on the sociotropic longitudinal effect of income inequality on political trust lends additional support to the long-standing argument that inequality is harmful for democracies. Alongside the many other social dysfunctions income inequality has been associated with, these political implications should further motivate efforts directed at its reduction.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org. Replication materials are available on OSF (DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/N6JT7).

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

This study is part of the project POLAR: Polarization and its discontents: does rising economic inequality undermine the foundations of liberal societies? (PI: Markus Gangl), that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement no 833196-POLAR-ERC-2018-AdG). Neither the European Research Council nor the primary data collectors and the providers of the data used in this research bear any responsibility for the analysis and the conclusions of this paper.

Earlier versions have been presented at the ECSR 2021. The author thanks all participants, Markus Gangl, Svenja Hense, Alexander Schmidt-Catran, Zsófia S. Ignácz, Gert Pickel, and Anastasia Gorodzeisky for helpful comments and suggestions.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2023.1197317/full#supplementary-material

1. ^Similar distinctions have been made between system-level (or constitutional) and public-opinion aspects of legitimacy (Weatherford, 1992; p. 150), between objective and subjective (Fuchs and Roller, 2019; p. 226–227), or between formal and informal legitimacy (cf. Pennings, 2017; p. 83–84).

2. ^These system components, arranged from most diffuse to most specific, are national identities, approval of core regime principles and values, evaluations of regime performance, confidence in regime institutions and approval of incumbent officeholders (Norris, 2011; p. 24).

3. ^It should be noted at this point that the status seeking index is not the optimal measure for status concerns. First, it captures the relative importance of achievement, respect and recognition, it does not measure the negative affect and psychological state related to status anxiety and social-evaluative stress that may be (more) important for the relationship between inequality and trust (Layte and Whelan, 2014). Second, the items used to construct the status seeking index are derived from the human values scale and were originally developed to tap into achievement and power values (Schwartz, 2012). According to values theory, values are an aspect of one's personality that develops in early childhood and adolescence and remains rather stable over the life course. By implication, status seeking values would not change due to changes in a person's environment and status seeking values could therefore not mediate the relationship between macroeconomic (i.e., contextual) inequality and political trust. At the same time, a key feature of values is that they are adaptive to changes in the environment (Bardi and Goodwin, 2011; Vecchione et al., 2016). Recent research attests to the reality of personal value change over the life course (Lersch, 2023) and status seeking in particular has been shown to be affected by contextual income inequality (Paskov et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2022). In the context of this study and the time-series cross-sectional data it relies on, it is not possible to test whether individuals change their status seeking as a consequence of changes in macroeconomic inequality. Until future studies provide comparative panel data evidence on the relationship between inequality, status seeking and political trust, this remains a necessary (and contestable) assumption. Despite these limitations, status seeking is the only viable option given the lack of alternative items to tap into status concerns. In light of these limitations, however, the results should be interpreted as a first, not a final test of the social-psychological mechanism.

Almond, G. A. (1963). The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press.

Andersen, R., and Curtis, J. (2012). The polarizing effect of economic inequality on class identification: Evidence from 44 countries. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 30, 129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2012.01.002

Anderson, C. J., and Singer, M. M. (2008). The sensitive left and the impervious right. Multilevel models and the politics of inequality, ideology, and legitimacy in europe. Comparat. Polit. Stud. 41, 564–599. doi: 10.1177/0010414007313113

Bardi, A., and Goodwin, R. (2011). The dual route to value change: individual processes and cultural moderators. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 42, 271–287. doi: 10.1177/0022022110396916

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., and Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using {lme4}. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Bell, A., Fairbrother, M., and Jones, K. (2019). Fixed and random effects models: making an informed choice. Qual. Quant. 53, 1051–1074. doi: 10.1007/s11135-018-0802-x

Bell, A., and Jones, K. (2015). Explaining fixed effects: Random effects modeling of time-series cross-sectional and panel data. Political Sci. Res. Methods. 3, 133–153. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2014.7

Buttrick, N. R., and Oishi, S. (2017). The psychological consequences of income inequality. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass, 11(3):e12304. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12304

Christmann, P. (2018). Economic performance, quality of democracy and satisfaction with democracy. Elect. Stud. 53, 79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2018.04.004

Dalton, R. J. (2004). Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices: The Erosion of Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268436.001.0001

Delhey, J., and Dragolov, G. (2014). Why inequality makes europeans less happy: The role of distrust, status anxiety, and perceived conflict. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 30, 151–165. doi: 10.1093/esr/jct033

Delhey, J., and Newton, K (2005). Predicting cross-national levels of social trust: global pattern or Nordic exceptionalism? Eur. Sociol. Rev. 21, 311–327. doi: 10.1093/esr/jci022

Delhey, J., Schneickert, C., and Steckermeier, L. C. (2017). Sociocultural inequalities and status anxiety: redirecting the spirit level theory. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 58, 215–240. doi: 10.1177/0020715217713799

Delhey, J., and Steckermeier, L. C (2020). Social ills in rich countries: new evidence on levels, causes, and mediators. Soc. Indic. Res. 149, 87–125. doi: 10.1007/s11205-019-02244-3

Donovan, T., and Karp, J (2017). Electoral rules, corruption, inequality and evaluations of democracy. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 56, 469. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12188

Easton, D. (1975). A re-assessment of the concept of political support. Br. J. Polit. Sci., 5, 435–457. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400008309

Elsässer, L., and Schäfer, A. (2023). Political Inequality in Rich Democracies. Annual Review of Political Science, 26(1):null. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-052521-094617

Enders, C. K., and Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: a new look at an old issue. Psychol. Methods. 12, 121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121

Engler, S., and Weisstanner, D. (2021). The threat of social decline: Income inequality and radical right support. J. Eur. Public Policy. 28, 153–173. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2020.1733636

European Social Survey Cumulative File ESS 1-9. (2020). Data file edition 1.0. Sikt - Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, Norway, Norway - Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC.

Fairbrother, M. (2014). Two multilevel modeling techniques for analyzing comparative longitudinal survey datasets. Political Sci. Res. Met. 2, 119–140. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2013.24

Foa, R., Klassen, A., Slade, M., Rand, A., and Williams, R. (2020). The Global Satisfaction with Democracy Report 2020. Cambridge: Centre for the Future of Democracy.

Fuchs, D., and Roller, E (2019). “Globalization and political legitimacy in western europe,” in Democracy under Threat: A Crisis of Legitimacy?, Van Beek, U. (eds). Cham: Springer International Publishing. p. 221–254. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-89453-9_9

Gidron, N., and Hall, P. A. (2017). The politics of social status: Economic and cultural roots of the populist right. Br. J. Sociol. 68, S57–S84.

Gilley, B. (2009). The Right to Rule: How States Win and Lose Legitimacy. New York: Columbia University Press.

Goubin, S. (2020). Economic inequality, perceived responsiveness and political trust. Acta Politica. 55, 1. doi: 10.1057/s41269-018-0115-z

Goubin, S., and Hooghe, M. (2020). The effect of inequality on the relation between socioeconomic stratification and political trust in Europe. Soc. Justice Res. 33, 219–247. doi: 10.1007/s11211-020-00350-z