94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 21 August 2023

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1179181

This article is part of the Research TopicMetropolitan Governance: Models, Policies and Political ProcessesView all 5 articles

Critical social scientific accounts of the confused and inconsistent process of “devolution” in England in recent years have rightly emphasized the place that Greater Manchester and, most recently, the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, has occupied at the forefront of UK metropolitan institutional reform. They typically give little credit, however, to the long-running, independent processes of mobilization and institution-building that have resulted in Greater Manchester achieving this vanguard position. This article challenges the idea that contemporary metropolitan governance in Greater Manchester can be seen merely as a pawn in the hands of a regressive, centralist state or else as an undemocratic vehicle designed to enable a city elite to dominate its metropolitan neighbors. In taking a longer historical perspective than is common to critical accounts, the article demonstrates that metropolitanization in England has not followed a coherent centralizing script and neither has the current Combined Authority been constrained, or chosen, to adopt the narrow economic development logic its critics allege. The latter is exemplified by an empirical examination of the work done in Greater Manchester on the theme of work and health. The article concludes with an assessment of how a fragile and very English form of devolution might develop in the difficult context in which the UK now finds itself, arguing that social scientific analysis can perform much better in identifying ways in which further enhancements of sub-national autonomy can support the realization of progressive social and environmental goals.

“Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) and its constituent member councils are the undisputed pioneers of English devolution. This success is built on a long history of decades of collaboration across the city region where the Mayor, political leaders, senior managers, partners and stakeholders work hard in the best interests of residents. As the strength of this collaboration has developed the trust of government in the CA has evolved too.” Local Government Association Corporate Peer Challenge. Greater Manchester Combined Authority: Feedback report (LGA, 2023, p. 3).

It is widely recognized within the UK local government world that Greater Manchester has played a leading role in recent reforms of subnational governing arrangements in England or in “English devolution” as it has become known. Within the academic literature, however, there is much misunderstanding about how a single metropolitan area in the former industrial heartland of north-west England came to occupy this vanguard position, together with significant controversy about the purposes that metropolitan governance reform has been designed to serve.

One recent strand of critical social science sees the latest manifestation of metropolitan government for the area—the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA)–as simply one of many products of a strategy pursued by recent right of center UK Governments to engender competitive economic behavior at subnational level whilst at the same time stripping local government of its capacity to pursue more redistributive goals. For (Tomaney, 2016, p. 550–51), for example, it fits, unexceptionally, into a context in which:

“England is moving in the direction of an idiosyncratic, uneven and highly centralized form of multilevel government where devolved policy-making is approved only if it meets the criteria of central government… Underpinning the new policy is a theory of economic development that fosters interurban competition and economic concentration [and] tolerates and indeed even celebrates high levels of socio-economic inequality.”

Other critical perspectives take a longer-term view and allow for a greater degree of local agency. On this view it is the political and executive leadership of one of the metropolitan area's ten lower tier local authorities—Manchester City Council—that is generally seen both as the prime mover in the search for better economic performance and as the dominant “player” in a metropolitan coalition it was instrumental in forming. Hodson et al. (2020, p. 208), for example, taking a draft metropolitan land use plan to be emblematic of broader Greater Manchester governing arrangements, sees them as:

“...an attempt to formalize the property-led regeneration agenda that had been developed through the urban growth coalition and soft governance of the 1990s and 2000s... to solidify the narrow governing coalition of political interests (Manchester City Council, Greater Manchester Combined Authority) and developer interests (e.g., Renaker, Peel Holdings) and its extension to include new, often international, financial actors.”

In both accounts, metropolitan institutions are regarded as being driven by elites that are remote from metropolitan electorates and to have little independent effect on residents' sense of belonging or their support for greater subnational autonomy.

It is contended, in this article, that these two alternative interpretations of the evolution of metropolitan governance for Greater Manchester contain elements of truth but ultimately oversimplify complex realities. They fail to fully appreciate the ways in which the interplay between centralized power, local agency and economic circumstance have combined to produce a highly distinctive and dynamic approach to metropolitan governance reform that is proving popular with voters and could ultimately have a profound effect on the future course of devolution in England.

The remainder of the article takes the themes that contributors to this special issue were encouraged to examine in turn and uses them to structure an account of the evolution of different forms of metropolitan governance in Greater Manchester since the early 1970s. The next section examines the extent to which metropolitan governance reform can be seen as an instrument of centralization by assessing the principal ways in which national governments have directly and indirectly shaped and influenced the nature and form of metropolitan structures. A third section offers an account of the way in which different areas of public policy have been “metropolitanized” over time, examining the way Greater Manchester's ten local authority districts collaborated in the voluntary development of metropolitan institutional capacity in advance of the more recent, statutory changes and the factors that encouraged them to do so.

A fourth section examines the latest stage of metropolitan institutional development which was ushered in by the direct election of a metropolitan Mayor in 2017, assessing the degree of change involved and arguing against the idea that the evolving arrangements are constrained, by either national or local political forces, to follow a narrow economic agenda. A final section then assesses evidence on the degree of popular support that has been accorded to the Mayor and the metropolitan institutional structures he oversees and speculates on what the Greater Manchester experience over the last fifty years might mean for future changes in the importance and functions of sub-national government in the UK, and outlines some implications for future analysis and research.

The claim that the UK state is amongst the most centralized in the developed world and that central control over local government has been increasing, under national Governments of all political colors, since the mid-1970s, has become axiomatic within both academic and popular debate (Travers, 2013; UK2070 Commission, 2020; Commission on the UK's Future, 2022; McCann, 2023). Whilst the creation of stronger, more autonomous tiers of government in the UK's non-English nations (Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland) at the end of the last millennium is not easily squared with the notion of consistent, generalized, long-run centralization, this characterization certainly holds true for England, where 85% of the UK population lives.

Since the mid-1970s, and an end to the steady expansion of local government employment and capacity that had characterized the post-World War II period, local authorities have faced ever-stricter controls over local tax-raising, reductions in central government grants during times of austerity, a decline in the proportion of public servants they employ relative to national government, and the steady erosion of their delivery roles in respect of public services. In the process, they have seen their once-dominant roles in respect of key services such as social housing, education, public transport and social care denuded.

It is nonetheless hard to interpret national government attitudes to metropolitan governance in England as a natural complement to growing centralization during the same period. In reality, the nature and degree of interest UK Governments have shown in metropolitan governance reform over the last half century is sporadic and lacking in any consistency. It is only in retrospect that it is possible to identify three key “moments” when national government concern with metropolitan governance, for good or ill, was at its height.

The first of these moments slightly predates the onset of centralizing tendencies whilst at the same time underlining the fact that UK local government has no constitutional protection when national government wishes to change its status, function or form. The re-organization of local government that was debated extensively in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, legislated for in 1972 and introduced in 1974 (Redcliffe-Maud and Wood, 1974) was the first comprehensive reform for nearly a century. Designed at a time when the long post-war period of economic and population growth was expected to continue, the national reforms followed the trail already blazed in London in the early 1960s and introduced a metropolitan tier of government outside the capital for the first time.

The reforms abandoned the earlier and, by that time, unworkable principle that urban and rural areas should remain administratively separated for the purposes of local service delivery. In its place came a presumption in favor of uniting urban and rural areas within larger local government units that were big enough to be viable but not so big as to be ungovernable. The experts who advised on the reforms disagreed on the extent of “metropolitanization” that was needed. A majority favored a Greater London-style metropolitan tier only for what were then the three largest and most complex provincial conurbations—around Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester—and a single, unitary tier of local government elsewhere (HMSO, 1969). A dissenting memorandum published alongside the majority report argued for comprehensive metropolitanization via a new, country-wide, two-tier system based on fifty-three new city-regions (HMSO, 1969). The Conservative government that eventually introduced the reforms mixed and matched expert advice and balanced it against party political considerations. A new two-tier system of local government was introduced everywhere but the six new upper tier metropolitan counties that were created (of which Greater Manchester was one), more likely to be controlled by the Labour party, were less geographically extensive than expert advisors had advocated and were made weaker, in the functions they were empowered to perform, than the much larger number of upper tier counties in the rest of the country that were more likely to favor Conservatives.

The 1974 reforms produced a huge reduction in the number and types of local government units and created some of the largest local authority areas, by population size, in the world. In the case of what became Greater Manchester, 68 lower tier authorities, spread across four traditional county areas and covering a population of two and a half million people, were reorganized into just ten new lower tier districts overseen by the single new metropolitan county council (Barlow, 1995, p. 383–4). No change on this scale would ever have occurred had it not been imposed by national government. In this sense at least, the very notion of Greater Manchester is the product of centralized power. The reforms also had other implications for the future. The first was to establish a tradition whereby strategic “environmental” services, including planning and transportation, were seen as “metropolitan” concerns whereas citizen-facing and more personalized services became the preserve of lower tier districts.

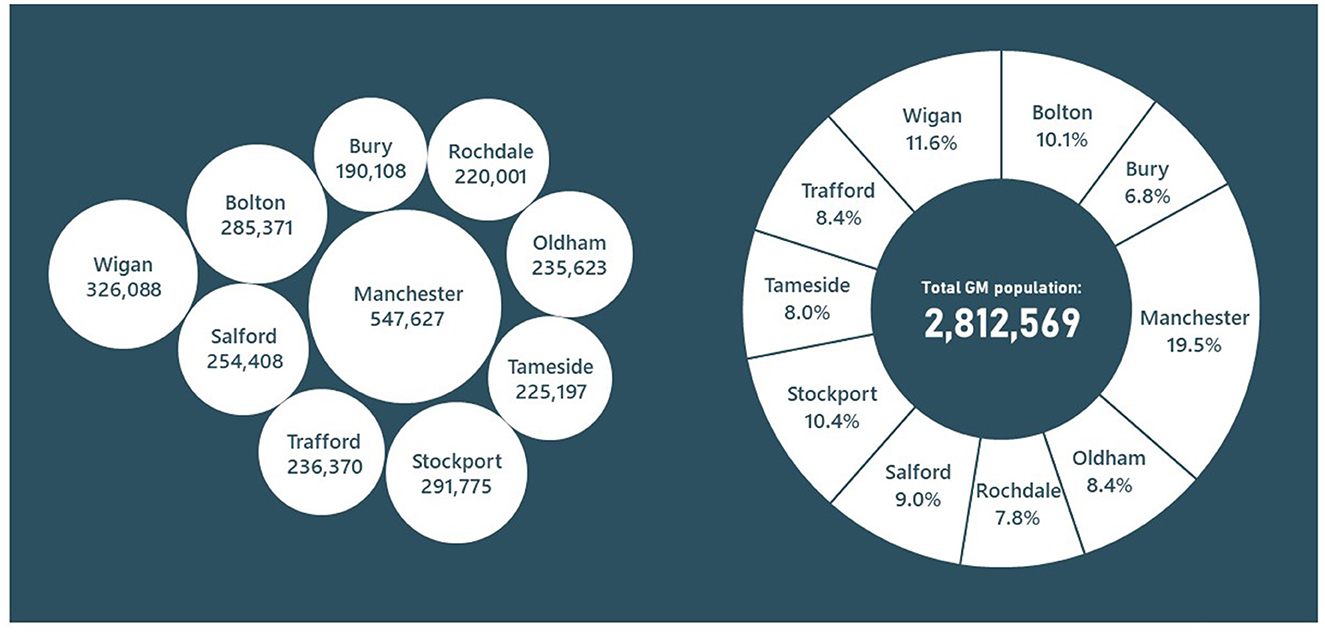

The geography of the 1970s reforms was also to prove important for future metropolitan arrangements in Greater Manchester. For other new metropolitan areas the opportunity was taken to increase the size of the core city so that, for example, Leeds and Birmingham became “first among equals” within new arrangements in the sense that their share of the metropolitan population was substantial (i.e., more than a third) (Leach and Game, 1991). Such a change did not happen in Greater Manchester, where the core city of Manchester remained virtually unchanged and initially comprised only around a sixth of the new metropolitan population (see Figure 1). One effect of the Greater Manchester reforms was to distribute the high concentration of employment clustered at the center of the conurbation between three lower tier districts: Manchester, which retained most CBD functions, Salford, then still the inland port that connected the conurbation to international trading routes, and Trafford, home to Trafford Park, the world's first large scale, dedicated industrial estate.

Figure 1. Schematic Greater Manchester district map showing rough geographical positions and current population shares. Source: ONS and GMFM.

A second effect of the geography of change was to ensure that most suburbs, townships and rural areas from which commuters traveled to work in the conurbation core remained outside the central city. Many, indeed, remained outside Greater Manchester altogether as new districts to the south of what became the new metropolitan area contested the expert guidance that adjudged them part of the functional city-region and lobbied successfully to remain outside the metropolitan administrative area. Manchester's integration with and dependence upon neighboring local authority areas within and beyond Greater Manchester was therefore designed much more powerfully into its new metropolitan arrangements than was the case elsewhere. This may be one reason why the name given to the Greater Manchester County Council proved relatively uncontroversial (Clark, 1973, p. 101) in contrast to all the other new provincial metropolitan areas, none of which came to bear the name of its largest city. Birmingham and Leeds were able to dominate their new metropolitan areas, but their counties were obliged to adopt more neutral names, West Midlands and West Yorkshire respectively, in order to assuage local sensitivities.

The second “moment” in which metropolitan governance captured significant attention on the part of national government came in the mid-1980s when another Conservative government moved to abolish all the upper tier metropolitan authorities its predecessors had created. The ostensible logic for change was that sub-national governance needed to be “streamlined” to contain costs and prevent wasteful competition between tiers of government (Department of the Environment, 1983). The fact that streamlining was only deemed necessary in Greater London and the six metropolitan areas that an earlier Conservative government had deliberately created in a weaker-than-recommended form only a decade earlier hinted, however, that abolition stemmed from rather different motivations.

This Conservative volte face was a product of the tense intergovernmental politics of the time. As noted earlier, the roles and functions of the “mets” were designed at a time when it was confidently expected that the UK's principal conurbations would continue to grow. By the time the new authorities came into being, however, deindustrialization had accelerated dramatically and many of the country's older urban areas were experiencing depopulation, economic decline and rising unemployment (Hausner, 1987; Barlow, 1995, p. 390–1). Having been given responsibility for “strategic” services but finding themselves with a policy toolkit designed for the management of growth rather than the reversal of decline, the new metropolitan authorities, many of them under Labour party control, together with many of the economically hard-pressed, Labour-led urban districts, went in search of creative ways to support economic resurgence. And before long they found themselves doing so during a time in which increasingly bitter conflict between urban local authorities and Margaret Thatcher's post-1979 Conservative governments began to arise over forced reductions in local government finance.

It was in this highly politicized context that a Conservative national administration terminated the short-lived experiment with metropolitan government in England that its predecessor had introduced, partly to remove some of the political platforms its critics used to mobilize opposition to national policies (O'Leary, 1987). It is ironic, given later experiences, that abolition was also motivated by a wish to prevent the development of economic strategies at this scale. The abolition of metropolitan government, however, did not spell the end of metropolitan governance. Whilst some of the functions of the “mets” were picked up by lower tier districts, many were put in the hands of single purpose metropolitan executive agencies overseen, at best, by indirectly elected boards. This was the case, in all the “met” areas, for police forces, fire and rescue services and transport executive agencies. In most cases, including in Greater Manchester, Government advice to co-operate in the creation of metropolitan waste disposal authorities was also followed. Greater Manchester's ten remaining authorities went considerably further than those in other areas affected by abolition, however, in retaining and building metropolitan institutional capacity (Leach and Game, 1991, p. 148–50).

The third “moment” in which national government paid significant attention to metropolitan institutions once more did not arrive for another 20 years. In the intervening period there was piecemeal retreat from the two-tier local government settlement introduced by the 1974 reforms and a slow but incomplete transition to unitary local government facilitated by the abolition of further upper tier counties and the withdrawal from two tier structures by some of the larger urban authorities. By the time national policy interest in metropolitan governance resurfaced in the early 2000s, the key concerns of the then Labour Government were less to do with local government reform and more with its struggle to deliver on its inter-related pledges to reduce sub-national disparities in prosperity and wellbeing and to create a new tier of elected authorities at the weakly-institutionalized regional scale in England.

The move to create elected authorities in the eight administrative regions in England outside the capital came after a major but selective programme of devolution was introduced by the post-1997 Labour Government. New devolved government structures for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were created in 1998 and 1999 and metropolitan governance for London, involving the first ever direct election of a metropolitan Mayor, was recreated in 2000. All these reforms were subject to popular referenda. Whereas change in these two cases was driven by a perceived need to bow to pressure to grant higher levels of political and executive autonomy, however, there was no comparable impetus for democratic change in the English regions. National policy in the rest of England was instead more closely linked to Government aspirations to improve economic performance, particularly in “lagging” areas, and to reduce spatial economic disparities over the longer term.

Institutional reform in this case began with the creation of Regional Development Agencies whose activities were overseen by Government appointees. Partly appointed and partly indirectly elected Regional Assemblies provided some limited indigenous oversight of Agency activity but there was a commitment to explore a more thoroughgoing democratization of regional development policy at some future point if and when it could be shown that there was popular demand for it. The English regionalization movement, such as it was, subsequently collapsed in 2004 when the first of three planned referenda on whether to create elected regional assemblies in the north of England was lost by a huge margin (Sandford, 2009).

The emphatic rejection of elected regional government by the voters of North East England, the administrative region in which support for some form of devolution was expected to be highest, left the then Labour government with no subnational institutional reform plan to align with its spatial economic aspirations. It was at that point that interest in city-regions resurfaced in policy debate, building upon the arguments that academics, think tanks and other policy analysts were making at that time about the importance of cities and agglomeration economies to national economic performance (New Local Government Network, 2000, 2005; New Horizons report, 2004; Harding et al., 2006; Rodríguez-Pose, 2006). The response by the post-2005 Labour administration was to bolt some minor policy initiatives with a metropolitan flavor onto programmes and structures that were already in existence. A series of Multi-Area Agreements was announced, for example, which aimed to achieve the sort of policy integration and stakeholder collaboration at a larger geographical scale than was already being attempted at a district level. Shortly before the party lost the 2010 election, however, it did take one tentative step toward institutional reform when it passed legislation allowing for the creation of statutory Combined Authorities and proposed pilots in Greater Manchester and the extended urban area centered upon Leeds.

The Conservative-led coalition government of 2010-15 and its Conservative successor, at least until the changes of leadership that followed in the wake of the 2016 Brexit vote, were surprisingly enthusiastic supporters of Combined Authorities (CAs), which its leaders saw as building blocks on which they could claim to pursue economic “rebalancing” between the super-region around London and the rest of England. They instituted a programme whereby several CAs, led mainly by new, directly elected Mayors, were created and provided with a range of bespoke powers and resources via a series of bilateral “deals” negotiated between groups of local authority leaders and Government departments. To understand the origins of this approach, however, it is necessary to return to the experience of Greater Manchester after the abolition of its metropolitan county council, during the long period in which UK national governments showed no interest in metropolitan governance.

As we have seen, the Thatcher Government that abolished the “mets” recognized the case for continuity in metropolitan service delivery when it enabled the setting up of separate, statutory, indirectly elected joint bodies in the fields of passenger transport, policing, fire and waste disposal. In Greater Manchester's case, the ownership of Manchester airport was also transferred to the ten district councils, with 55% of shares going to Manchester City Council (the airport's original owner) and 5% each to the other nine. Greater Manchester's councils also organized themselves to voluntarily take over responsibility for a range of services previously provided by the metropolitan authority. A single district typically assumed lead responsibility on behalf of all ten authorities for Greater Manchester-wide services that ranged from the management of local government employees' pension fund to research and intelligence, consumer protection, transport modeling, ecology, archaeology, traffic control, air and water pollution, and the archiving of administrative records (Hebbert and Deas, 2000, p. 83–4). A voluntary partnership of all ten districts—the Association of Greater Manchester Authorities (AGMA) was also created to provide oversight of statutory and voluntary metropolitan institutional activities and to provide a forum for discussion of issues of collective interest.

Greater Manchester's 10 districts, uniquely, continued to build upon these initial post-abolition metropolitan foundations over the next two decades, mainly in the absence of any national Government requirement, encouragement or incentive to do so. A schematic timeline of metropolitan self-organization and capacity development is captured in Figure 2. The story it tells is of the consensual, incremental development of institutional and analytical capacities, most of which were eventually incorporated into the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) when it assumed its current form in 2017, shortly before the inaugural term of its first directly elected Mayor began. The most recent stage of this journey, following the creation of GMCA in a skeletal form in 2011, needed national statutory underpinning and drew upon active Government support but for much of the period since 1986 Greater Manchester forged an independent path, drawing pragmatically on UK Government and European Union programmes that were useful but without ever fitting entirely comfortably within national policy frameworks.

As one of us has described elsewhere at greater length (Harding, 2020), a few key features, taken together, help distinguish the evolution of metropolitan governance capacity in Greater Manchester in the 1990s and “noughties” from what happened in other former “met” areas. The first of these, the primacy of economic concerns in establishing momentum in the development of metropolitan collaborative activity, reflected two critical factors:

• Need and opportunity. It would be difficult to overstate the devastation that the recession of the early 1980s visited upon the UK's older established manufacturing areas and the extent of concern that was felt in those areas that national government was not sufficiently attentive to the challenges they faced. It is therefore unsurprising that a collection of local authority areas whose voters tend toward the Labour party should want to establish its own collective approach to supporting economic change. It is equally unsurprising, given the success that Manchester City Council started to achieve in pursuing a pragmatic approach to economic development and regeneration after Labour lost the 1987 national election (King and Nott, 2006), that neighboring authorities should come to see that Council's approach as something they could support, emulate and benefit from.

• Institutional fit. Irrespective of need or opportunity, it was predictable that strategic economic concerns would be favored at metropolitan scale given the roles the metropolitan council had performed before abolition, the retention of statutory and voluntary metropolitan structures for surface transport, the airport and aspects of planning, and the jealousy with which the lower tier districts guarded their social policy and programme responsibilities. Institutional fit was also aided by Greater Manchester's designation as an Objective 2 area for the European Commission's structural funds. The Commission adopted “NUTS2” areas, which coincided with the former “met” areas, as the basis for their programmes and required area-wide collaboration for policy design and delivery.

Even before new metropolitan organizations started to appear, joint activity related to city-regional connectivity, for example, saw the completion of the orbital motorway system that runs through every district and the opening of the first phase of Metrolink, the country's first new tram system, in the years immediately following abolition.

The initial primacy of economic development is reflected in the type of metropolitan institutional collaborations that evolved but the form they took reflects a second key factor; the tendency for collaborations to move at the pace of the fastest, rather than the slowest, partner. Thus the City Pride initiative, for example, a response to a 1994 national government invitation to improve synergies and co-ordination between development and regeneration programmes in London, Birmingham and Manchester, immediately became a collaborative initiative in Greater Manchester in a way it didn't elsewhere. The initial partnership, however, was between the three authorities covering the conurbation core—Manchester, Salford and Trafford—before it was extended to neighboring authorities in a later phase. Similarly, MIDAS, the inward investment agency, began life in 1997 as a collaboration between the same three core authorities and one of Manchester's neighbors (Tameside) before later being extended to all ten authorities once they gained confidence in its performance. Conversely, Marketing Manchester, the visitor attraction agency formed in 1996, was the first new institutional innovation that was supported by all ten districts from its inception. It helped, in this case, that much of the funding came out of the profits of the jointly owned airport but it also established a precedent that saw consensus across all ten districts become common in later phases of institutional development.

A third factor contributing to the cautious but consistent development of metropolitan collaboration is remarkable consistency of political and executive leadership, particularly within Manchester City Council, the authority that was at the forefront of metropolitan institutional change from abolition to the election of the Greater Manchester Mayor. Whilst the Greater Manchester voting public leans consistently toward the Labour party in national as well as local elections, there has never been a point since 1986 when all ten authorities have been under Labour control. At times, the party has had majorities in as few as five of the districts. One advantage of pluralistic metropolitan politics is that Greater Manchester invariably has decent political connections into national government, irrespective of its party complexion. This, along with the cultivation of good relationships with key local business leaders, has enabled lines of communication with national government to be kept open even during times when inter-governmental relations have become strained. Its corollary, however, is that consensus on what is done and aspired to at the metropolitan scale must always be built and maintained across party lines, which puts a premium on leadership.

Unusually, Manchester City Council has in recent years welcomed only its third leader (2021) and third Chief Executive (2017) since abolition. For virtually the whole period in which Greater Manchester's experiment with the bespoke development of metropolitan governance took shape, it had the same leader and Chief Executive. Both saw significant value in metropolitan solidarity and joint activity and were able to develop a long-term approach, safe in the knowledge that electoral change in a safe Labour city was unlikely to threaten their positions. It was they and their City colleagues who invariably led in the building of metropolitan capacities. In this they found a willing political ally in the long-serving chair (2000 to 2017) of AGMA, Greater Manchester's voluntary local government association who was also the longstanding Labour leader (1991–2018) of the council covering Greater Manchester's most peripheral district, Wigan. In simple terms, the City cultivated powerful connections to peripheral areas, particular in northern Greater Manchester, via Labour party politics and with districts covering the central and southern areas of the metropolitan area, less predictably Labour-dominated, through shared economic assets and interests and stronger labour market inter-connections.

A fourth factor that is often seen as a strength that marks Greater Manchester apart is a commitment to strongly evidence-based policy at the metropolitan scale (Holden and Harding, 2015). This claim can be overdone, given that there are tactical as well as purely analytical considerations at play. In essence, though, this commitment reflects the advantages that developing an overarching narrative can offer in two broad respects. At the metropolitan scale, a common evidence-based narrative can bind the metropolitan area's many stakeholders together, thereby guarding against fragmentation of understanding or effort, whilst at the national and even international scale, it can signal a depth of place-specific knowledge that is difficult to challenge and serves to denote seriousness of understanding and intent to potential allies and partners. Two analytical “set pieces” demonstrate the way evidence-based narrative building in Greater Manchester has been employed to strengthen what are sometimes referred to as horizontal and vertical relationships, that is between the ten districts, on one hand, and between the ten as a collective and national government on the other.

The Manchester Independent Economic Review (MIER) (MIER Reviewers, 2009) represented an attempt by Greater Manchester's leaders to influence the direction of English spatial development policy, through independently sponsored research, at a time when a partial shift in national policy emphasis toward city-regions was taking place. By drawing on researchers who were prominent in contemporary debates about the importance of agglomeration economies, the MIER argued that Manchester and its surrounding area was particularly well placed to deliver faster economic growth in the lagging north of England if a supportive policy context could be agreed and powers and resources devolved to deliver on it. The MIER effectively laid down a marker for the debate Greater Manchester leaders would have with members of the coalition government that came to power in 2010. It did not, as some of its critics have alleged, ignore the distributive implications of the policy choices it favored but rather emphasized the need to improve access to new employment opportunities, for example via improvements in transport, education and early years provision for children, rather than expect to determine the locational choices of firms and organizations.

The Greater Manchester Independent Prosperity Review (IPR) (IPR Reviewers, 2019), similarly, was designed in part to provide an evidence base for a policy initiative; on this occasion the development of a Local Industrial Strategy on which national government had agreed to collaborate with the GMCA. The broader intention, however, was to revisit the MIER, whose observations were rooted in analysis of the sustained period of economic growth that preceded the financial crash of 2008, in light of the changed economic circumstances that followed. Delivered once more via independent reviewers and research, the IPR underlined critical challenges with low productivity, insecure employment and the quality of work that had accompanied recovery from the crisis as well as identifying the critical importance of physical and (particularly) mental health to the patterns of inequality experienced across the metropolitan area.

The above discussion has emphasized that the rebuilding of metropolitan governance after 1986 was a dynamic and incremental process that was clearly driven more by a combination of internal factors that were particular to Greater Manchester than by UK Government imposition. Quite how metropolitan self-organization was affected by the need to bargain with a national government that was only just beginning to understand how stronger metropolitan governance might also serve its purposes is analyzed in the next section. It should be stressed, though, that Greater Manchester leaders had already arrived at the conclusion that its voluntaristic style of collaboration was not fit for all purposes.

What clinched this view was a failure, in 2008, to achieve consensus across all districts on a transport investment proposal that would have generated £3 billion worth of Government investment into Greater Manchester's public transport system on the proviso that there was agreement to proceed with a congestion charging scheme for motorists. When two Greater Manchester councils chose not to support the proposal that came forward, the decision was made to hold a popular referendum informed by a period of campaigning. The referendum produced a resolution—a decisive rejection of the scheme—but left leaders in no doubt that governance arrangements for working up and agreeing programmes with transformational potential needed to be tightened up considerably in order to avoid future embarrassment and any repeat of the strain that threatened at one point to destroy the prospect of future metropolitan collaboration.

By the end of the “noughties” Greater Manchester had established a unique set of institutions that built out from the statutory metropolitan agencies that survived abolition and extended into areas such as inward investment, visitor promotion, training and skills, and business development. It had set out, through the MIER, a set of aspirations about how the metropolitan area could better contribute to the national goal of reducing regional disparities whilst at the same time signaling the importance of enabling the benefits of improved economic performance to be realized by people across Greater Manchester. And it had learned some difficult but valuable lessons about the limits of voluntary collaboration.

In all these respects, Greater Manchester had first-mover advantage when the coalition government that came into power in 2010 decided to retain the legislation that enabled the establishment of combined authorities and, over time, linked their creation to its national “rebalancing” aspirations, one element of which was to encourage a “Northern Powerhouse” focused on the northern English city-regions. At the same time as this line of thinking developed, the Government also caused massive disruption in subnational development policy capacity elsewhere by:

• Abolishing the English regional development structures created by its Labour predecessors and discontinuing most of the UK (as opposed to EU) economic development and regeneration programmes that sustained local authority activity in these fields, and

• Moving to create an England-wide network of business-dominated Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) for “natural economic areas” but without specifying how such areas should be identified or how those who defined and acted for them were to be resourced.

Whilst local authorities in most other areas of England struggled to define new geographies, institutions and purposes that suited Coalition requirements, Greater Manchester's districts were able simply to build on what already existed and was in development at the metropolitan scale. This involved creating the country's first Combined Authority, effectively as an empty shell, in 2011, and then engaging with Government on ways it could be provided with an appropriate constitution and populated with powers and resources. The route that was chosen to accomplish this was a process of “deal making” which resulted, in Greater Manchester's exceptional case, in the signing of six bespoke, bi-lateral, intergovernmental deals in a frenetic period of activity between 2014 and 2017 followed by a further “trailblazer” deal in 2023 through which national government formally recognized that the combined authorities for Greater Manchester and the West Midlands remained at the forefront of change.

Whilst these intergovernmental agreements have often been described as, even called, “devolution deals” it is important to recognize that they do not involve any permanent reallocation of statutory or fiscal power from the national to the subnational level as was the case with the creation of devolved authorities in the non-English UK. Only in a small number of instances, for example in adult education, has responsibility for a service area been passed entirely to the Combined Authority. In other cases (e.g., in relation to investment in transport and new housing development), “deals” allow for greater certainty in the future flow of Government resources. Or else they enable the sharing of service commissioning powers that were formerly held exclusively by national agencies with the Combined Authority and its partners.

The broad shape of the governance structures that the GMCA and most subsequent combined authorities adopted was established in Greater Manchester's first “deal”, in 2014, when the 10 district leaders agreed, somewhat reluctantly, to create the position of a directly elected Mayor in order to trigger the maximum level of new powers and resources that would be available. Over the following 3 years, a constitution was agreed which clarified the powers and responsibilities of the Mayor, as Chair of the Combined Authority, the 10 district council leaders who form the Mayor's Cabinet, and AGMA. Unlike in London, whose upper tier authority is made up of 25 directly elected Assembly members in addition to the Mayor, Greater Manchester's Mayor is the only additional elected politician in the new arrangements. He works with a small number of deputies, one of whom is appointed to the role of Police and Crime Commissioner, the 10 district council leaders who each assume responsibility for a portfolio of metropolitan policy activities and their respective Chief Executives, who share administrative responsibilities with the staff of the Combined Authority and other metropolitan executive agencies.

The Combined Authority's executive support arrangements were created through a “lift and drop” process which saw most programme delivery responsibilities hived off into a separate executive agency, the Growth Company, in 2017, leaving the more strategic functions to be overseen by a newly appointed Chief Executive. Greater Manchester's Fire and Rescue Service, followed by the Waste Disposal Executive, were transferred into the Combined Authority in its earliest days. The police service, together with the transport authority and a special purpose body responsible for health and social care (see below), remain organizationally distinct but are linked into Combined Authority business via portfolio holders and the joint responsibility that members of Greater Manchester's family of metropolitan executive agencies hold for delivering common strategies. Within the Combined Authority there are teams supporting statutory metropolitan services (police, fire, waste, transport) along with others active in planning and housing, skills, employment and business support, digital, environmental and cultural sector development, and public service reform, including health and care.

The arrival of the directly elected Mayor in 2017 saw the biggest change in Greater Manchester's governance in the sense that it introduced a direct electoral mandate, based on a set of political manifesto commitments, into the mix of Combined Authority activities for the first time. Mayoral leadership on certain issues produced some departures from previous practice, or at least a re-ordering of priorities. The focus that was put on ending rough street sleeping during the Mayor's first term, for example, resulted in much greater coordinated effort being put into understanding and dealing with the issues faced by a vulnerable cohort of homeless people. It also provided the first indication of the convening power that the elected Mayor—a former national government Minister with a high media profile—would be able to mobilize in the absence of any statutory responsibilities for some of the challenges he considered important.

In most respects, the requirement that the Combined Authority's constitution places on the Mayor to work with and through others and to build on previous development work means that Mayoral leadership is best seen as speeding up evolution rather than fomenting revolution. One good example of evolutionary change which confounds the argument that Greater Manchester strategies are dominated by narrow concerns with profitability and job creation, is the work that has been done on health and employment.

Greater Manchester's second “deal” with Government in February 2015 was the most exceptional, covering all the health and social care spending committed to Greater Manchester (£6bn p.a.). It was delegated to a new body, the Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership, thereby consolidating the integration of clinical and public health. Whilst this initiative came as a surprise to observers at the time, it was built upon existing work in Greater Manchester and the promise of providing a model that could help the National Health Service (NHS) deliver its strategic aspirations. Clinical health is led by the NHS whilst public health is a responsibility of local government.

At the time of the deal, there was a sense of urgency to do things differently, with Government keen to turn the tide on increasing demand for NHS services and wishing to “get serious about prevention” (NHS England, 2014, p. 9). There was a realization that earlier warnings that demand for future healthcare would outstrip planned supply had not been heeded (Wanless, 2004). As a result, the NHS developed a 5 year forward view strategy in which partnerships from across England, including Greater Manchester, were asked to develop place-based Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STP) (NHS England, 2014; GMCA, 2015). While other STP areas or footprints were building partnerships, the Greater Manchester process built on existing, well-established networks. The plans produced by Greater Manchester were lauded as the “most far-reaching and amicable integration initiative in England so far, by some way” (Wistow, 2017, p. 21).

The Greater Manchester STP soon morphed into a devolution plan called “Taking Charge” and a Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership (GMHSC) became responsible for managing the £6bn health and social care budget. The plan set out four high level reform themes: upgraded population health prevention, transformed community-based care and support, standardized acute and specialist care, and standardized clinical support and back-office services. There were also collective leadership and governance arrangements. There are three intended mechanisms of action: subsidiarity and governance; integration around places and people; and efficiency and effectiveness (Walshe et al., 2016, p. 4). The new partnership included 37 organizations from across the metropolitan area: the ten local authorities, NHS organizations, primary care, NHS England, the community and voluntary sectors, the police and the fire and rescue service.

Some observers thought the changes being proposed were leading to overly complex organizational relationships that would make delivery too difficult (National Audit Office, 2017) and that the arrangements in Greater Manchester were introducing further layers of complexity to already complex arrangements (Checkland et al., 2015). However, from a Greater Manchester perspective there was also some sense of relief given the work that had already been invested in identifying the decisions to be made, at which scale and where the scope for economies of scale and the need for standardization lay (Charles, 2017). Greater Manchester's health “devolution” deal recognized, formalized and enabled the extension of pre-existing work rather than heralded a new beginning. It represented the latest stage in a heavily populated timeline of initiatives and events across the history of Greater Manchester and changes in the NHS.

The Manchester Area Agreement in 2006 was an economic strategy but notably identified prioritizing support for early years. An independent national review of health inequality, commissioned by the Secretary of State for Health and published in 2010 made a raft of recommendations including taking a whole life-cycle approaches to tackling inequality and focusing on person-centered services (Marmot et al., 2010). Greater Manchester responded to the Coalition Government Community budget initiative in 2013, with work on integrated health and social services. Nationally, radical health policy changes opened up local commissioning of health services through the introduction of clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) in 2012. This changed landscape enabled pockets of proactive work to reduce health inequality and enable integration of services across the metropolitan area. Integrated, targeted support for troubled families also began in 2012 (Ozan et al., 2019).

Six months in advance of the STPs (2015), fifty NHS vanguard schemes for health and social care integration were put in place across England including in two in the Greater Manchester districts of Stockport and Salford. These were intended to take a leading role in refining new approaches and models of integration as well as incorporate “diverse solutions and local leadership, in place of further structural distraction” (NHS England, 2014, p. 28). They were testbeds to generate lessons that could be taken forward elsewhere. Some of the alarm at the rushed nature of the health deal in Greater Manchester was that the vanguards had only just been put in place. However, the vanguards were also valuable for demonstrating that there was the capacity and deliverability in place for that second deal. The work in Stockport, for example, focused on proactive care and used a delivery model called Multi-Specialty Community Provider (MCP) bringing together different providers of care and health experts in the local area to prioritize health and care activity in response to real-time information of the local situation.

Prevention of ill health was an important aspect of the health deal not only because it would improve the lives of those who live in Greater Manchester but also in recognition that it made economic sense. A recent review found that poor health potentially accounted for up to 30% of the productivity gap with the UK average (IPR Reviewers, 2019). The public cost-savings through integration and public service reform formed an important part of the negotiations of the health deal. The evidence-based approach to cost-benefit analysis was developed by New Economy, the research arm of the Greater Manchester Partnership (and later part of the combined authority). The cost-benefit analysis approach developed in collaboration with national civil servants was subsequently incorporated into Government evaluation methodologies (National Audit Office, 2013).

The Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership established that if no action were to be taken and delivery were to continue as it was, not only would health outcomes continue to lag England averages, but by 2021 there was expected to have been a £2 billion public funding gap in Greater Manchester. This gap was later revised. Savings and opportunities were expected to be made across all areas, including by joining up back-office functions; training and passporting staff across institutions to reduce agency costs; more efficient use of the estate; efficiencies from joint commissioning; public health initiatives and community-based care leading to reduction in demand in the relatively expensive acute care settings (GMHSC Partnership, 2018).

A key aspect of the devolution deal was the £450 million additional transformation funding to support developments and improvements to the overall system. Ensuring that the health and social care system worked more closely with the wider work around education, skills, work, and housing meant the combined total budget was expected to be £22billion. Through strategic projects the partnership secured further ad hoc funds, the additional surplus from savings made, were to be retained in Greater Manchester for investment in capital programmes (GMHSC Partnership, 2018).

The first stages of delivery, post-deal, involved planning, creation of organizational structures and consultation work as well as formalizing relationships with NGOs, the community and voluntary sector. In January 2017, a memorandum of understanding was signed with a collection of more than 15,000 different NGOs, to formalize their role in the partnership (GMCA, 2017). While focus is often on the significance of the health deal, this agreement was a critical additional step, not only because it recognized citizen engagement (South et al., 2019, p. 10) but also because the NGOs were essential for delivering the new integrated interventions and the person-based care.

Local Care Organizations (LCO) were created in each of the ten local authority areas in the metropolitan area with the remit to create innovations based on their local knowledge and population needs. The LCOs were eligible to secure investment through the Greater Manchester Transformation Fund. The Chief Officer of the Greater Manchester partnership was responsible for the overall Transformation funds but employed by NHS England not the GM Mayor. In practice they both work closely but this creates a fragile position where GMCA and Greater Manchester Integrated Care Partnership (was GMHSCP) remain answerable to NHS England for the use of the devolved funding and what is achieved with it (GMCA, 2015).

According to our research with Greater Manchester policy partners, significant effort is tied up with mitigating against national government policies that have had direct influence over economic inequality and health outcomes as well as responding to delivery of national policies. The Combined Authority does not have direct powers over many important policy areas such as housing and welfare, but this gap has created spaces1 for policy conversations. The preventative approaches that emerged have included family and person-centered interventions. Working with those who require multiple agency support. Post-Mayoral work incorporates learning from pre-mayoral programmes, the person-centered troubled families programme influenced Working Well, the programme developed from a pilot in 2014 to support those furthest from work into employment.

The indications are that the approach taken to health in Greater Manchester has been making a positive impact, independent research showing a small but significant improvement in life expectancy since the deals (Britteon et al., 2022). Whilst the leap to the deal was not as far as may have been felt, integrating such a fragmented set of services was always going to be a huge and ongoing task. The foundation built before the deal included a demonstrable understanding of the problems of fragmented service delivery and how cost savings would be better redirected toward service delivery and how impact could be transformative for individuals and influenced productivity. Greater Manchester policy makers had already recognized the value of system level intervention, of investing in breaking negative cycles and patterns such as investing in early years. Metropolitan leaders were able to win the confidence of Government through speaking the language of the Treasury, using the jointly developed cost benefit analysis tools.

For all the long history of voluntary metropolitan collaboration that preceded it, the GMCA remains a young organization and the office of the Greater Manchester Mayor an even more recent addition to reconstituted, statutory metropolitan governance in England. Both continue to evolve within an unusually unstable national policy context in which, most recently, a Conservative Government with the largest Parliamentary majority for decades has gone through three Prime Ministers and five Chancellors (chief finance ministers) in 2 years whilst struggling to maintain a consistent response to any of the shocks arising from a combination of COVID19, Brexit, energy price instability and falling living standards. It is therefore difficult to anticipate whether recent statutory metropolitan reforms, in which Greater Manchester has played such a prominent role, will prove longer lasting than those triggered by the comparatively thoroughgoing, but ultimately temporary, re-organization 50 years ago.

What is clear so far is that the modern-day Greater Manchester experiment is proving popular. The current Mayor won a comfortable majority of votes cast (63%) in his first election victory in 2017 on a voter turnout of 29% which was marginally below the average for local elections in Greater Manchester. When he stood again in 2021, a second election triumph saw him win in every electoral ward, in every district, with an increased share of the total vote (67%), drawn from an increased turnout (35%) that was slightly higher than the Greater Manchester average. Polling undertaken for the Center for Cities think tank in each of the combined authority areas shortly before the last Mayoral elections demonstrated that Greater Manchester's Mayor was better known to the metropolitan electorate than any of his fellow metro mayors, emphatically so in every case bar London. The approval rating he received for his perceived handling of the COVID pandemic was the highest in the country, comfortably outstripping those given to his fellow metro Mayors, national government and other local authorities. In total 85% of survey respondents in Greater Manchester pronounced themselves in favor of further devolution, with affordable housing, support for businesses, a greater say over tax and spending decisions and bus service improvements topping their list of priorities (Centre for Cities, 2021).

This is not to argue that the new arrangements are without tensions. In some instances, the effective use of new “powers” has proven challenging. Six years into the new Mayoral regime, for example, the land use plan that the Combined Authority is responsible for drawing up but must be agreed by all the districts has still not passed through all the stages necessary to it becoming statutorily enforceable and one of the districts has withdrawn from the scheme. Whether GMCA is striking the best feasible balance between supporting economic growth in a relatively thriving regional center and enabling growth, and the fruits of growth, in less prosperous parts of the metropolitan area is also a permanent tension that needs careful management.

With the conclusion of the latest “trailblazer” deal, though, Greater Manchester clearly continues to set the pace in what remains a highly asymmetric approach to devolution within the UK. Whilst no subnational authority in England is afforded a guaranteed share of public expenditure, as is the case in the devolved, non-English nations, the latest deal has triggered discussion with national government which should see the myriad of funds that the Combined Authority and its partners receive from national departments bundled together in a “single pot” which will allow discretion over the way they are deployed. Depending on how it is implemented, this adds to the ratchet effect whereby discrete packages of activities are prized out of Whitehall and made subject to autonomous metropolitan decisions.

The most recent round of inter-governmental negotiations has not resolved any of the more challenging dilemmas surrounding the future of metropolitan governance and combined authorities more generally because they are not being debated. Fiscal devolution of any significant sort remains off the table for both Government and national opposition parties and is not something that any of the metropolitan authorities, with the exception of London, have been keen to explore, such is the fear that “devolution as dumping” (Maclennan and O'Sullivan, 2013, p. 612) would leave subnational authorities with responsibilities and obligations that their tax bases could not sustain. There is silence, too, about where the weak form of devolution that has been trialed in England thus far fits with current Government aspirations for “leveling up”, which has replaced the previous Conservative Government's “rebalancing” and an early Labour Government's “reducing regional disparities” as the political formulae that denotes concern with spatial and social inequalities.

In the medium term, there appear to be two potential scenarios for English metropolitan “devolution” and the role it might play in an evolving, asymmetric system of UK multi-level governance. In the stronger version, Greater Manchester and other areas become more assertive in their dealings with national government, start to challenge the baleful history of centralization in dealing the key societal challenges and begin to win debates about “taking back control” that are framed in terms of demonstrable evidence that devolved systems can produce better outcomes. The other is that metropolitan areas such as Greater Manchester essentially act as promising test beds for policy experimentation, learning from which can be captured and transferred sensitively into other contexts. We have examined the example of health here because it demonstrates not only that there is far more to metropolitan governance in Greater Manchester than a concern with GVA, jobs and the profits of housing developers but also because it shows how metropolitan innovation can develop, gain traction and deliver for the benefit national government and its agencies as well as for localities.

These scenarios are not mutually exclusive, of course. Indeed, each would be more powerful if they proceeded in tandem. The problem with making further progress toward either of them is that centralization has established as firm a grip on habits of thought as it has over the distribution of powers and resources. Social science has a potentially important role to play here. Whilst policy makers celebrate the relative success Germany has had in integrating the former eastern Lände into a resilient national economy since reunification, for example, we still await the powerful interdisciplinary analysis that would demonstrate how framework conditions there or in the Scandinavian countries combine to produce fewer unequal outcomes. Similarly, whilst there are endless case studies purporting to show “what works” in terms of outcomes of devolved decision making in a variety of contexts and policy areas, answers to the trickier questions of “what works where, and why?” and what might be learned from others' experiences remain in much shorter supply. The challenge for academics is not so much about the extent of knowledge as of finding ways of putting it together around policy challenges more effectively and changing the balance of critique to constructive potential solutions in much scholarly work.

Something interesting has happened in metropolitan Manchester over the course of the last 37 years. A mental construct called Greater Manchester has come to play an important part in the way key players within local economic, political and social life see themselves, their roles and their obligations. Greater Manchester's local authorities started the ball rolling when they joined statutory organizations like the airport, the police, the fire authority, the transport authority and the waste management agency in organizing themselves, at least in part, on a metropolitan footprint. In the years that followed, local Chambers of Commerce dissolved themselves and formed a single Greater Manchester Chamber. Social housing providers came together in a single Greater Manchester umbrella body that explores and represents common interests. Voluntary and community organizations banded together to support a similar umbrella organization that can represent them at the Greater Manchester scale. The area's five universities joined forces in a Civic Universities Agreement. And health and social care bodies came together at a Greater Manchester scale in an attempt find solutions to challenges that every part of the UK faces. This has happened in the absence of any consistent support from UK national governments and without exciting much interest on the part of a skeptical social scientific community. Who knows what Greater Manchester might become if it ever did.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: all additional data drawn upon for the article are reported in the agenda and meetings of the Greater Manchester Combined Authority and its affiliated organizations, details of which can be found at: https://greatermanchester-ca.public-i.tv/core/portal/home.

All sections of the article draw on ideas provided by AH and SP-J. Main authorship of the second and third sections is by AH and of section four by SP-J. AH and SP-J shared responsibility for the introduction and conclusion. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

SP-J's PhD research was supported by a University of Manchester, Faculty of Humanities Doctoral Studentship.

AH was working as part time Chief Economic Adviser for the Greater Manchester Combined Authority during the writing of this article and continues to provide advice to the authority as a consultant. SP-J was employed by the University of Manchester on a research project which involves being an embedded researcher in the Greater Manchester Combined Authority and Transport for Greater Manchester. Both of these organizations are referred to in the article but the judgements made within it are personal to the authors as academic observers.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^A network ethnography, three focus groups and twelve elite interviews across a range of GM partners (trades unions, business organizations, health partners, housing providers, community and voluntary organizations, local government) were undertaken as part of PhD research in 2019.

Barlow, M. (1995). Greater Manchester: conurbation complexity and local government structure. Polit. Geogr. 14, 379–400. doi: 10.1016/0962-6298(95)95720-I

Britteon, P., Fatimah, A., Lau, Y.-S., Anselmi, L., Turner, A.J., Gillibrand, S., et al. (2022). The effect of devolution on health: a generalised synthetic control analysis of Greater Manchester, England. Lancet Public Health. 7, e844–e852. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00198-0

Centre for Cities. (2021). New Polling Finds Public Overwhelmingly Back-More Devolution. Available online at: https://www.centreforcities.org/press/new-polling-finds-public-overwhelmingly-back-more-devolution/ (accessed February 28, 2023).

Charles, A. (2017). Bottom up, top down, middle out: transforming health and care in Greater Manchester [WWW Document]. The King's Fund. Available online at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2017/11/transforming-health-care-greater-manchester (accessed August 29, 2022).

Checkland, K., Segar, J., Voorhees, J., and Coleman, A. (2015). “Like a Circle in a Spiral, Like a Wheel within a Wheel': the layers of complexity and challenge for devolution of health and social care in Greater Manchester. Representation 3, 23. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2016.1165514

Commission on the UK's Future. (2022). A New Britain: Renewing our Democracy and Rebuilding Our Economy. Available online at: https://labour.org.uk/page/a-new-britain/ (accessed February 3, 2023).

GMCA. (2015). Taking Charge of our Health and Social Care in Greater Manchester of our Health and Social Care. Available online at: https://www.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/media/1120/taking-charge-of-our-health-and-social-care-plan.pdf (accessed February 3, 2023).

GMCA. (2017). GM VCSE Accord Agreement. Greater Manchester Combined Authority Manchester, UK. Available online at: https://greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/media/5207/gm-vcse-accord-2021-2026-final-signed-october-2021-for-publication.pdf (accessed February 3, 2023).

Harding, A. (2020). Collaborative Regional Governance: Lessons from Greater Manchester. Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/1807/100727 (accessed February 3, 2023).

Harding, A., Marvin, S., and Robson, B. (2006). A Framework for City-Regions. London: Office of Deputy Prime Minister.

Hausner, V.A. (1987). Critical Issues in Urban Economic Development: v.1. Oxford : New York Oxford University Press.

Hodson, M., McMeekin, A., Froud, J., and Moran, M. (2020). State-rescaling and re-designing the material city-region: Tensions of disruption and continuity in articulating the future of Greater Manchester. Urban Stud. 57, 198–217. doi: 10.1177/0042098018820181

Holden, J., and Harding, A. (2015). Using Evidence: Greater Manchester Case Study. London: What works Centre for Economic Growth.

IPR Reviewers (2019). Greater Manchester Independent Prosperity Review: Reviewers” report Manchester. Available online at: https://greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/what-we-do/economy/greater-manchester-independent-prosperity-review (accessed February 3, 2022).

Leach, S., and Game, C. (1991). English metropolitan government since abolition: an evaluation of the abolition of the english metropolitan county councils. Public Admin. 69, 141–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00788.x

LGA (2023). LGA Corporate Peer Challenge, Greater Manchester Combined Authority: Feedback Report. Available online at: https://greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/media/7248/gmca-cpc-final-report.pdf (accessed February 3, 2023).

Maclennan, D., and O'Sullivan, A. (2013). Localism, devolution and housing policies. Housing Stud. 28, 599–615. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2013.760028

Marmot, M., Allen, J., Goldblatt, P., Boyce, T., McNeish, D., Grady, M., et al. (2010). Fair Society, Healthy Lives: Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England Post-2010 (Report). London: The Marmot Review.

MIER Reviewers (2009). Manchester Independent Economic Review. Available online at: https://greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/media/6668/mier-review.pdf (accessed February 28, 2023).

National Audit Office (2017). Health and social care integration 56 HC1101. London: Department of Health, Department for Communities and Local Government and NHS England.

National Audit Office. (2013). Case Study on Integration: Measuring the Costs and Benefits of Whole-Place Community Budgets, HC1040 Session 2012–2013. Department for Communities and Local Government, Stationery Office, London, United Kingdom.

New Horizons report. (2004). Realising the National Economic Potential of Provincial City-Regions: The Rationale for and Implications of a “Northern Way” Growth Strategy. Salford: University of Salford.

New Local Government Network. (2005). Seeing the light? Next steps for city regions. London: New Local GovernmentNetwork.

O'Leary, B. (1987). Why was the GLC abolished? Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 11, 193–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.1987.tb00046.x

Ozan, J., O'Leary, C., Baines, S., and Bailey, G. (2019). “Troubled Families in Greater Manchester,” in Implementing Innovative Social Investment: Strategic Lessons from Europe, eds. A., Bassi, F., Sipos, J., Csoba, S., Baines (Bristol: Bristol University Press) 43–58. doi: 10.46692/9781447347842.004

Redcliffe-Maud, L., and Wood, B. (1974). English Local Government Reformed. Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress.

Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2006). The City-Region Approach To Economic Development. A report to the Department for International Development, London.

Sandford, M. (2009). The Northern Veto, Illustrated edition. ed. Manchester. Manchester: University Press.

South, J., Connolly, A.M., Stansfield, J.A., Johnstone, P., Henderson, G., and Fenton, K.A. (2019). Putting the public (back) into public health: leadership, evidence and action. J. Public Health 41, 10–17. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdy041

Tomaney, J. (2016). Limits of devolution: localism, economics and post-democracy. Polit. Quart. 87, 546–552. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12280

Travers, T. (2013). Raising the Capital: The Report of the London Finance Commission. London: London Finance Commission.

UK2070 Commission. (2020). Make no little plans: Acting at scale for a fairer and stronger future. Final report of the UK2070 Commission. Available online at: https://uk2070.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/UK2070-FINAL-REPORT-Copy.pdf (accessed February 3, 2023).

Walshe, K., Coleman, A., McDonald, R., Lorne, C., and Munford, L. (2016). Health and social care devolution: the Greater Manchester experiment - ProQuest. Br. Med. J. 5, 352.

Wistow, G. (2017). “Hope over experience: still trying to bridge the divide in health and social care,” in Devo-Then, Devo-Now: What Can the History of the NHS Tell Us About Localism and Devolution in Health and Care? eds H., Quilter-Pinner, and M., Gorsky (London: Institute for Public Policy Research) 18–21.

Keywords: devolution, city-region, governance, sub-national, metropolitan, Manchester

Citation: Harding A and Peake-Jones S (2023) Understanding the search for more autonomy in Greater Manchester: an alternative perspective on the politics of devolution in England. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1179181. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1179181

Received: 03 March 2023; Accepted: 21 July 2023;

Published: 21 August 2023.

Edited by:

Mariona Tomas, University of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Karsten Zimmermann, Technical University Dortmund, GermanyCopyright © 2023 Harding and Peake-Jones. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sian Peake-Jones, c2lhbi5wZWFrZS1qb25lc0BtYW5jaGVzdGVyLmFjLnVr

†ORCID: Alan Harding orcid.org/0000-0002-6681-5662

Sian Peake-Jones orcid.org/0000-0002-3251-9187

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.