- 1Department of Political Science, Guido Carli Free International University for Social Studies, Rome, Lazio, Italy

- 2Department of Social, Political and Cognitive Sciences, University of Siena, Siena, Italy

- 3Department of Political Science, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

COVID-19 constitutes an unprecedented exogenous shock for democratic political systems across the globe. During this turbulent period, Italy and Israel have also experienced a government crisis. Building upon the “coalition life cycle” and the “critical events” approaches to government stability, this article explores the trajectories of the government crises in Italy and Israel in times of COVID-19. The article examines the impact of the cabinets' structural attributes and the pandemic in relation to the governments' early termination. In both countries, the oversized coalition configuration of the cabinets led to conflicts between the governing parties, which became untenable during the pandemic crisis, thus precipitating the governments' collapse.

1. Introduction

Research on government crises in democratic political systems has a long and consolidated record. Government crises have indeed inspired academic inquiries and received considerable attention in political science studies. In the comparative politics tradition, scholars have focused on explaining the duration of cabinets, asking why some cabinets last longer than others (King et al., 1990; Laver and Shepsle, 1998; Saalfeld, 2008). Early attempts to explain variations in the duration of cabinets looked at so-called “structural attributes” such as the configuration of cabinet types (e.g., Riker, 1962; Taylor and Herman, 1971), particularly concerning the distinction between single-party governments, minority, minimal-winning, and oversized coalitions. In the 1980s, the focus shifted to the role of critical events and what Warwick termed the “survival debates” (Warwick, 1994). Such debates were started by Browne et al. (1984), who argued that the vast majority of government terminations were driven by unpredictable or random events such as deaths or health problems of prime ministers, economic crises, corruption scandals, or personal conflicts.

The COVID-19 pandemic constitutes an unprecedented exogenous shock for democratic political systems worldwide. To curb the risks associated with public health, governments had to pass measures that limited citizens' freedom of movement, including national lockdowns (De Vries et al., 2021). Such measures brought about one of the most critical economic recession in modern history, increasing the scope for populist parties to challenge mainstream ones and gain comparative electoral advantages (Crulli, 2022). COVID-19 contributed to reshaping the main political competition dynamics in several countries, and highlighted the prominent role of non-elected experts in government (e.g., Andersson et al., 2022). Furthermore, the pandemic was center-stage in governments' concerns about budgetary policies (Cavalieri, 2023). Many countries have indeed had to switch to expansionary fiscal policies, increasing government expenditure to properly tackle the pandemic's impact on social protection, particularly health1 (e.g., Hale et al., 2021).

As governments had to deal with extraordinary policy challenges, the scope for internal conflicts and political (and governmental) instability increased (e.g., Newell, 2021). The extension of national restrictions due to the rapid spread of the virus and the emergence of new variants prompted major citizen protests, targeting incumbent governments and their political leaders (Erhardt et al., 2021). As such, the pandemic gave rise to different communication strategies related to the management of COVID-19 for parties in government and parties in opposition, thus contributing to increased politicization (Bobba and Hubé, 2021) as well as polarization (Capati et al., 2022).

This article aims to shed light on how the government crisis in Italy and Israel unfolded during the pandemic crisis. Specifically, the article investigates the role of the cabinets' structural attributes (i.e., their nature as oversized coalitions) and the COVID-19 pandemic in determining the governments' early collapse. The examination focuses on two fragmented and unstable multiparty democracies, traditionally ruled according to consensus style (Lijphart, 1999). In such systems, government responsibility is usually shared between several parties. The study argues that the cabinet type as an oversized coalition led to conflicts between the governing parties which became untenable during the pandemic crisis, thus precipitating the government fall.

The article is structured as follows. The second section presents the theoretical background. The third section illustrates the research design. The fourth and fifth sections analyse the origins and development of government crises in Italy and Israel respectively, and discuss the combined explanatory power of the cabinets' structural configuration as oversized coalitions and the outbreak of a critical exogenous event like a pandemic in leading to government termination. The sixth section draws a comparison between the Italian and Israeli government crises while the final section discusses the implications of the research and concludes.

2. Theoretical framework and research hypotheses

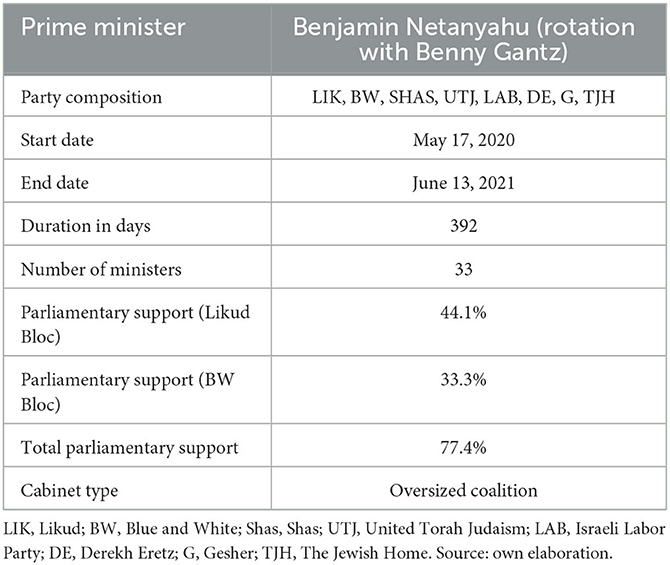

This article combines insights from the “coalition life cycle” (Bergman et al., 2021) and the “events” (Browne et al., 1984) approaches to the issue of government stability. To explain cabinet termination, the first focuses on structural factors, such as cabinet type, while the second emphasizes the relevance of contingencies that arise in the institutional environment in which cabinet actors operate. The coalition life cycle approach contends that all cabinet phases—notably, formation, governance, and termination—are interconnected (Strøm et al., 2008, p. 9). Recently, Bergman et al. (2021) further specified coalition politics dynamic, making predictions on the interplay between the three main stages (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The coalition life cycle. Source: Bergman et al. (2021).

Following Bergman et al. (2021), we build on the idea that what occurs during the early stages of the coalition life cycle, that is during the formation and negotiations to give birth to a coalition government, influences governments' policy actions and behavior, and ultimately affects the durability of the cabinet. In particular, the cabinet type, defined as the set of cabinet features related to party size in Parliament, plays a major role in boosting or hindering government survival (Dodd, 1976). Back in the day, Lowell (1896) had already observed that government stability is higher when the cabinet commands a parliamentary majority and when that parliamentary majority is provided by a single party. Along these lines, majority governments are expected to be more durable than minority governments, and among majority cabinets, minimal winning coalitions are expected to be more stable than oversized coalitions (Woldendorp et al., 1998). Minimal winning coalitions are more durable than other coalition types based on the “bargaining threat”; if cabinets are minimal winning coalitions, every coalition partner might appear to have an equally compelling threat (Riker, 1962; Kirsch and Langner, 2010). Conversely, a party whose votes are not crucial may be allowed to leave the cabinet, thus precipitating what is technically a cabinet breakdown (Heller, 2001).

For their part, oversized coalitions are expected to significantly undermine government stability (e.g., Meireles, 2016). Such ruling configurations increase the likelihood of intra-coalition conflicts, leading to lengthy decision-making and short endurance (see for Israel, e.g., Stinnett, 2007; and generally Bormann, 2019). According to Dodd (1976), oversized cabinets include “unnecessary” parties that could be removed from the cabinet with its ministerial payoffs distributed among the other coalition parties. Compared to minimal winning coalitions, in case of oversized coalitions at least one party could be removed from the cabinet without undermining the cabinet's stability. Thus, if unnecessary parties are omitted from the cabinet, some or all of the other coalition parties will obtain a higher ministerial payoff. For the sake of government stability, coalition parties should thus seek to reduce cabinet size by removing at least one party (Dodd, 1976).

Overall, oversized coalitions tend to increase the internal policy disagreement between the parties making up the cabinet (Grofman and Van Roozendaal, 1997). Indeed, as the membership of the government grows, the task of reaching an agreement among government parties becomes more difficult and chances of government breakdown increase (Warwick, 1979). Along these lines, the research hypothesis that can be derived is as follows:

H1: Oversized coalitions are prone to intra-coalition conflicts that undermine cabinet stability

On the other hand, the events approach to government stability argues that early government termination is associated with generally unpredictable, random events that arise throughout a government's tenure. These events can range from natural disasters and economic crises to political scandals and terrorist attacks (Browne et al., 1984). Events may arise in the environment of a government taking the form of demands or challenges that cabinet members must address with a high sense of urgency. The cabinet thus comes under increased pressure as it is collectively responsible for securing an efficient and swift response to the crisis as well as for granting the consistency of government action against an uncertain political environment. As the rising event becomes politically salient, it brings up policy issues with a largely divise (or consensus-threatening) potential (Browne et al., 1984).

The events approach expects exogenous shocks to significantly disrupt government stability in several ways. Firstly, they can challenge the ability of the government to effectively respond and provide essential services to its citizens. For instance, a natural disaster might overwhelm the government's resources and infrastructure, causing a breakdown in governance and public trust. Secondly, unexpected events can lead to public discontent and erode the legitimacy of the government. If the government is perceived as unprepared, incompetent, or unresponsive in the face of a crisis, it can result in widespread dissatisfaction and loss of confidence among the population. This can manifest through protests, political instability, or even calls for a change in government leadership. Moreover, unexpected events may create opportunities for rival coalition partners or opposition groups to exploit the situation and challenge the government's authority. Crises often provide a platform for criticism and can galvanize public opinion, leading to increased political contestation and instability.

Along these lines, ruling in turbulent times may lead to increased intra-coalition conflicts, as decision-making becomes key to dealing with existential events and coalition parties have less room to implement their agreed policy agenda, which increases the scope for internal disagreements (Marangoni and Vercesi, 2014; Plescia and Kritzinger, 2022). While large-scale unexpected events might or might not lead to early cabinet termination, they are expected to consistently produce cabinet instability in the form of increased intra-coalition tensions. The claim here is that critical exogenous events are the effective causal agents of cabinet instability, irrespective of the specific configuration of cabinet types (Browne et al., 1984).

From the above, the following hypothesis is derived:

H2: Unexpected events are likely to increase intra-coalition conflicts that undermine cabinet stability

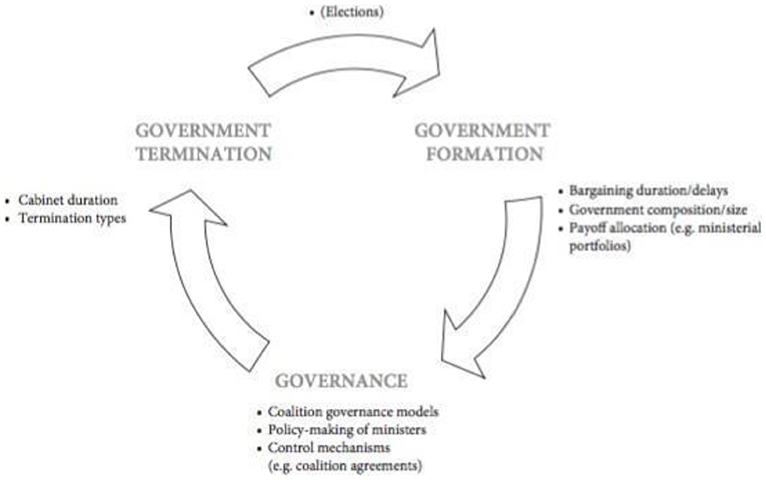

We thus build our synthetic conceptual scheme (Figure 2) upon the coalition life cycle and the events approach to government stability. To understand early cabinet termination, a causal sequence composed of two factors can be identified. The first factor concerns the cabinet's structural attributes, and in particular the cabinet type as an oversized coalition, which is expected to increase intra-coalition conflicts and undermine government stability even in “normal times”. The second factor regards the environment, that is the occurrence of critical exogenous events, which are expected to undermine the coalition stability by exposing ruling parties to conflicts over the direction of government action. We thus expect the combination of cabinet types as oversized coalitions and the occurrence of large-scale crises to be likely to lead to early cabinet termination. This is because, while the intra-coalition conflicts stemming from an oversized coalition can still be manageable in times of political and economic stability, exogenous shocks requiring swift policy action dramatically increase the scope for intra-coalition conflicts to grow in both frequency and intensity, thus causing a government crisis.

Figure 2. Synthetic conceptual scheme based on the traditions of structural and critical events. Source: own elaboration.

For the most part, governments in consolidated democracies operate in “normal times” and exercise ordinary powers such as ensuring effective governance and administration, managing the economy, providing public services and infrastructure, as well as taking care of security, defense, and external diplomatic relations. Sometimes, governments can be faced with minor, short-lived endogenous crises which typically originate from inherent vulnerabilities and imbalances due to internal political dynamics, policy decisions or governance issues (such as political polarization or local social unrest). Abrupt exogenous shocks—such as wars, economic collapse, floodings or pandemics—requiring governments to take bold and immediate action are indeed extremely rare. As one such shock, the COVID-19 pandemic provides an opportunity to investigate the combined effect of unanticipated critical events and oversized coalitions on government stability in contemporary democracies.

Specifically, we raise the following working hypothesis:

H3: The exogenous shock caused by the pandemic (environment) exacerbated intra-coalition conflicts in oversized coalitions (cabinet structural attributes), leading to a government crisis (government termination)

Hence, we identify the “oversized coalition” as our focal independent variable (structural cause), leading to intra-coalition conflicts. The underlying logic is that the larger the number of parties in government the more likely it is that some of them disagree with government decisions. In addition, we interpret the COVID-19 pandemic as an intervening variable (successive cause), that is a high-salience policy issue constituting the ground on which tensions within an oversized coalition government may intensify, leading to the government fall. We thus move from the consideration that cabinet structural attributes and events alone cannot provide a comprehensive account of government dissolution (King et al., 1990). The two factors can actually work simultaneously and combine to trigger a government crisis.

Along these lines, the paper selects two cases—Italy and Israel—that suffered government crises during the pandemic, and performs a qualitative analysis to assess whether and how the government crisis was related to cabinets' structural attributes and the outbreak of the pandemic crisis. It aims to test three main effects of the hypothesized causal mechanism. First, whether the oversized coalition format gave rise to tensions between coalition partners before the pandemic outbreak,2 in line with H1. Second, whether intra-coalition conflicts intensified with the pandemic, in line with H2. Finally, whether the government crises were related to pandemic crisis-management in the context of intra-coalition conflicts, as H3 implies. Indeed, if the hypothesized causal mechanism holds in the cases of Italy and Israel, three observable implications should follow. First, tensions between coalition partners should be apparent before the start of the pandemic due to the effect of the “oversized coalition” (independent variable). Second, such intra-coalition conflicts should intensify with the pandemic due to the effect of the “exogenous shock” of COVID-19 (intervening variable). Third, issues related to the management of the pandemic should lead to the “government crisis” (dependent variable).

3. Research design

3.1. Most different systems design and case selection

This study adopts a paired comparison strategy for analyzing the Italian and Israeli coalition governments during the recent pandemic crisis with a view to explaining their early termination. Specifically, the comparative analysis is based on the Most Different Systems Design (MDSD), which represents one of the most relevant approaches in comparative politics (Przeworski and Teune, 1970). This type of comparative method consists in comparing cases that are as different as possible with regard to a series of control variables but that have one key variable in common which is then expected to explain the similar outcome of the two cases. Following established guidelines in the literature, the MDSD is to be adopted when the cases observed have a constant dependent variable. The fundamental logic is that differences cannot explain similarities (Anckar, 2008). The analysis aims to test whether and how the oversized coalition cabinets (independent variable) in the two cases of Italy and Israel led to an early government fall (dependent variable) during the pandemic crisis (intervening variable).

In line with a MDSD comparison, Italy and Israel are political systems that display remarkable variation across a wide range of dimensions, such as the main conflicts behind political competition (foreign policy and religion in Israel Hazan et al., 2021, the economy in Italy Angelucci and De Sio, 2021), the structure of the legislature (unicameral in Israel [Knesset] and bicameral in Italy [Chamber of Deputies and Senate]), and the size of the legislature (120 members in the Israeli Knesset and 600 elected representatives in the Italian Parliament). Moreover, the two countries also differ in terms of their state systems. Specifically, Italy has a quasi-federal, decentralized governance arrangement with significant powers delegated to the regional governments (Lippi, 2011), including for running regional health systems, whereas Israel has a deeply centralized structure (Hazan, 1996). Finally, Italy and Israel have different sizes, populations, wealth and culture. Yet, when it comes to executives' structural attributes, they share one common feature, namely the frequency of oversized coalition cabinets.

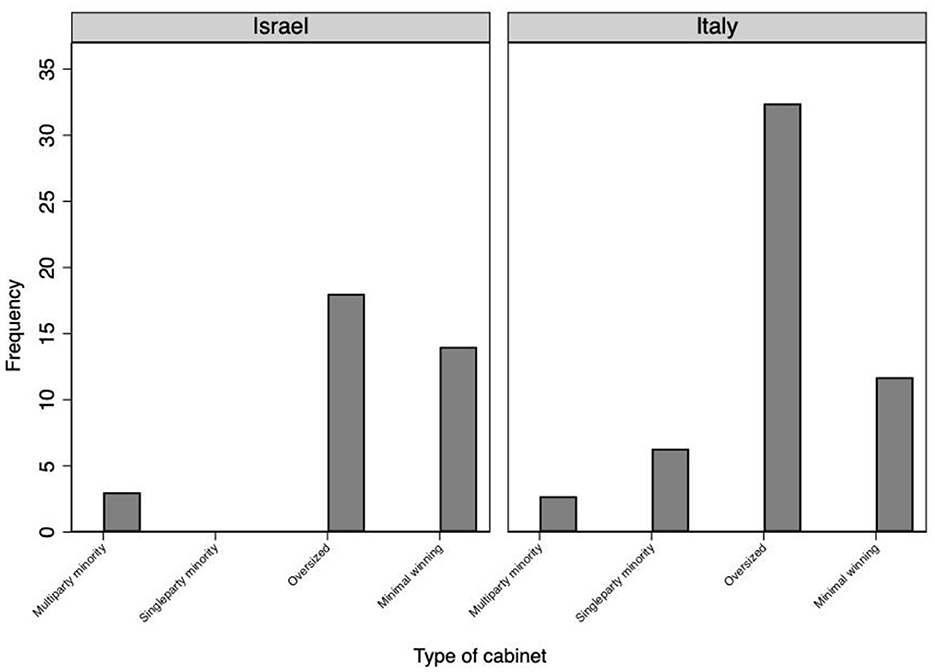

Through an original multilevel dataset composed of 103 cabinets, 67 for Italy and 36 for Israel, from 1948 to 2021 we show that oversized coalitions have been widespread in Italy and Israel, in line with their consensual model of democracy (Lijphart, 1999) (Figure 3 above). These countries are indeed characterized by either strong religious and cultural cleavages (as in the Israeli case see Hazan, 1999) or ideological and territorial cleavages (as in the Italian case see Ignazi and Wellhofer, 2017; Di Mauro and Verzichelli, 2019), ultimately leading to fragmented multiparty systems and large coalitions. This feature can thus serve as the independent variable that explains the early cabinet termination as a common dependent variable.

3.2. Process tracing and data

To trace the emergence and worsening of intra-coalition tensions in each case study and the relation between government crisis and the pandemic outbreak, the analysis takes the form of process tracing (Bennett and Checkel, 2015). It relies on both primary and secondary sources. The former include policy measures, such as the imposition of socio-economic restrictions through national lockdowns, as well as public statements, letters and speeches by political actors. The latter comprise the relevant literature and newspaper articles providing insights into the political dynamics under investigation. The analysis performed within each case takes the form of a “hoop” test (Beach and Pedersen, 2013; Mahoney, 2015). Hoop tests concern predictions that are certain but not unique, meaning that while the failure of such tests invalidates the research hypothesis, the passing of single hoop tests does not provide solid inferences to validate the hypothesis. There are, however, two ways to make hoop tests more compelling. The first is repeating a hoop test across different cases. As Beach and Pedersen (2013) argue, passing several hoop tests can ultimately have a confirmatory effect and support a theory. The second is tightening the “hoop” by increasing the predictions' level of uniqueness, which implies making the conditions to pass the test more stringent and difficult to meet.

We employ both tips to derive more solid inferences from our hoop test. On the one hand, we perform the same test in the context of two cases (Italy and Israel) which differ along multiple dimensions, as holding against different systems (rather than similar ones) increases the test's confirmatory power. On the other, we identify a series of observable implications from the hypothesized relationship between independent (oversized coalition), intervening (pandemic crisis), and dependent variable (government crisis) that serve as joint necessary conditions for the hoop test to pass. This contributes to increasing the uniqueness of predictions and the solidity of the inferences we can derive from the passing of the test.

4. Italy's government crisis: the Conte II cabinet and the COVID-19 pandemic

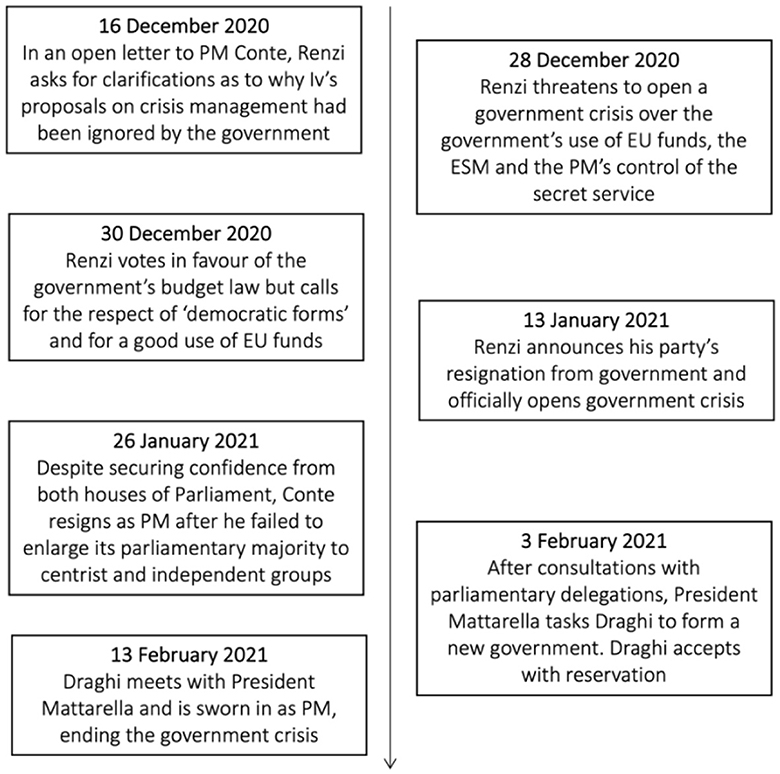

The aim of this section is to trace the origins and development of the government crisis in Italy (Figure 4 below) to assess the combined explanatory power of the Italian cabinet's structural configuration as an oversized coalition and the outbreak of a large-scale exogenous event such as the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, Section 4.1 tests H1. It shows how the second Italian cabinet led by Giuseppe Conte (from September 2019 to January 2021) qualifies as an oversized coalition. It then investigates the emergence of intra-coalition conflicts before the pandemic outbreak to gauge whether the cabinet's nature as an “oversized coalition” led to tensions in the government in “normal times”. Section 4.2 tests H2. It examines whether intra-coalition conflicts intensified during the pandemic crisis and how crisis-management issues affected the stability of the governing coalition. Finally, Section 4.3 tests H3 and shows that the fall of the Conte II government was caused by untenable intra-coalition tensions that arisen in relation to the management of the pandemic.

4.1. The Conte II cabinet and intra-coalition conflict before the pandemic

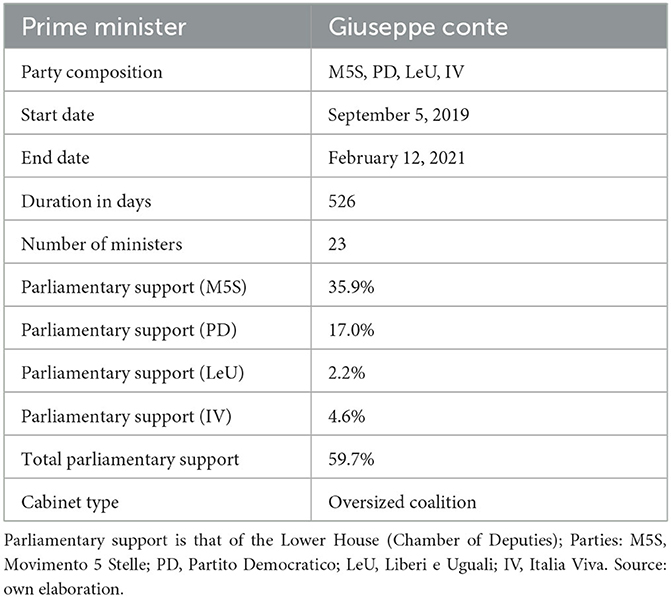

The Conte II cabinet was inaugurated on 5 September 2019 as an oversized coalition government comprising the Five Star Movement (M5S), the Democratic Party (PD) and Free and Equals (LeU). As shown by Table 1, at least one party could indeed be removed from the parliamentary majority without undermining the government tenure. The nature of the cabinet as an oversized coalition made it inherently fragile (Bull, 2021) and exposed it to the risk of intra-coalition conflicts. In addition, government fragmentation increased just a week after the government was sworn in, when former PM Matteo Renzi decided to leave his PD and form a separate parliamentary group, Italia Viva (Iv).

It was on these shaky grounds that Conte began his second term as Prime Minister. Before the pandemic, the turbulent relations among coalition partners undermined public support for the government and led to growing conflicts over several policy areas. The parties frequently confronted each other over government action, as the proposed reforms of the electoral law and the criminal justice system show. In early January 2020, after lengthy negotiations, the M5S and PD had announced the government's provisional agreement on a new electoral law, a proportional representation system with a nationwide threshold of 5% (La Stampa, 2020a). However, as Iv started losing electoral appeal in the polls, Renzi stepped back and reneged on the accord, claiming that “Italy needs a majoritarian electoral system” (La Repubblica, 2020a). This caused frustration among the other governing parties, which vainly urged Renzi to keep his word.

The tug of war between the governing parties also played out with respect to the reform of the criminal justice system. The reform was supported by the PD and LeU and proposed by Justice Minister Alfonso Bonafede (M5S). Renzi's Iv joined forces with center-right opposition parties in the judicial committee to thwart Bonafede's proposal (La Repubblica, 2020b). In turn, the PD blamed Iv for “betraying” the government and supporting the political opposition. Intra-coalition tensions worsened to the point that, on 13 February, Renzi announced a motion of no-confidence in Bonafede and threatened to withdraw Iv's support for the government (Giovannini and Mosca, 2021). On 15 February, Iv's national coordinator Ettore Rosato even talked of a “government mini-crisis” (La Repubblica, 2020b). On the same day, PM Conte declared that Renzi's behavior was “unreasonable” and “ill-mannered”, stressing that he would not tolerate blackmail (La Stampa, 2020b).

In sum, intra-coalition conflicts emerged well before the pandemic outbreak due to the cabinet's varied composition, including one large party (the M5S), one medium-size party (the PD) and two small formations (LeU and Iv), each with their idiosyncratic interests and positions. The cabinet type as an oversized coalition increased the scope for internal disagreements in “normal times” and undermined the credibility of the government action, thus confirming H1 in the case of Italy.

4.2. The COVID-19 pandemic and increased intra-coalition tensions during the Conte II cabinet

The sudden spread of the COVID-19 pushed the country into a state of emergency which had the apparent effect of putting party disputes on hold (Giovannini and Mosca, 2021). However, government cohesion was but a short-lived illusion. Tensions between the parties of the governing coalition soon re-emerged over pandemic-related issues, such as the intensive use of presidential decrees (DPCMs) by the Prime Minister to handle the crisis, the question of whether to borrow financial resources from the Pandemic Crisis Support of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and the allocation of EU funds in the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP). From the deliberation of the national State of Emergency on 31 January onwards, PM Conte constantly resorted to DPCMs to impose anti-pandemic restrictions, including national lockdowns. Such a practice was deemed to further centralize power in the hands of a single man and undermine inter-institutional dialogue on key national priorities by Iv's Renzi, who criticized the government for “suspending the civil liberties of sixty million citizens” (Avvenire, 2020). Renzi openly deplored the use of DPCMs and asked PM Conte to quickly change course. This prompted an angry reaction from coalition partner Zingaretti (PD), who lashed out at Renzi claiming that “it is ethically intolerable to have a foot in two shoes at the same time” (La Repubblica, 2020c).

The pandemic crisis also opened a confrontation in the government on whether to take out loans from the Pandemic Crisis Support, a light-conditionality credit line of the ESM introduced in May to help EU member states cope with the health costs related to COVID-19. From the beginning of the crisis, PM Conte and the M5S strongly opposed any recourse to ESM funds, favoring the introduction of Eurobonds instead. In April, Conte defined the ESM an “inadequate instrument”, adding “my position and the government position on the ESM has never changed and never will—Italy does not need it” (La Repubblica, 2020d). Without calling into question the stability of the government, in June Zingaretti challenged the Prime Minister's opposition to the ESM, suggesting that “we must escape ideological diatribes” and that “in the absence of any conditionality (the ESM) would become an important leverage for the public health service” (La Repubblica, 2020e). With quite harsher tones, Renzi manifested Iv's full support for making use of ESM financial assistance, saying “the Prime Minister will not say ‘no' to the ESM”. In November, tensions over the ESM were just as high, with the three major coalition partners firm on their positions. At that point, Italian media were starting to point to a possible government reshuffle toward the end of the year.

The governing coalition was not able to find a common line on the Italian NRRP either. In late November, Giuseppe Conte presented his plan for the governance of the Recovery Fund, including the establishment of a Task Force that “will report periodically to the Council of Ministers and to Parliament” (Corriere della Sera, 2020a). While the M5S agreed to the plan, the PD and Iv were not quite happy with it. The Democrats asked for the creation of an ad hoc society under the Ministry of Finance to govern the funds, and Iv defined the Task Force as an attempt by the PM to replace ministers with bureaucrats and decide for them. After repeated meetings between Conte and representatives of the PD, Iv and the M5S, no agreement was reached. By the end of the month, demands for a government reshuffle by leaders of the PD and Iv were all the more frequent (Corriere della Sera, 2020b).

The intra-coalition conflict that characterized the first phase of the Conte II government did not abate during the COVID-19 crisis. If anything, the pandemic contributed to intensifying tensions within the cabinet, especially on issues related to pandemic crisis management. This undermined the cohesion of the governing parties and set the cabinet on a collision course, confirming H2.

4.3. Italy's government crisis: the fall of the Conte II cabinet

The government crisis unfolded between December 2020 and January 2021. Diverging views on how best to cope with the pandemic led Iv to withdraw from the governing coalition, precipitating the cabinet fall. On 16 December, in an open letter to the PM, Renzi (2020) asked for clarifications as to why Iv's proposals on crisis management had been ignored by the government. First, Renzi insisted that Italy rely on the ESM to make investments on public health, culture and tourism. He stressed that the ESM would have less conditionality than the Recovery Fund and defined Conte's refusal as merely ideological. Renzi then turned to the NRRP and criticized the government in terms of both contents and methods. In the letter, he claimed that the plan is a “patchwork of proposals without a soul, without a vision, without an idea of what we want to be in 20 years”. The Iv leader blamed again the decision to establish a Task Force to manage the funds “in lieu of the government” and made clear that “we joined the coalition to avoid full powers to Salvini, we will not allow full powers to others”. As the PM deemed the letter a provocation, Renzi threatened to withdraw from the government.

On 28 December, after several meetings between representatives of the governing coalition to mediate divergences had failed, Renzi went on the attack again, announcing 61 points of criticism to the Italian NRRP. Renzi said the plan lacked ambition and was the product of bureaucracy, while reiterating that Iv would step down without an agreement. He then mocked the alliance between the M5S and the PD as a “marriage of convenience”. On 13 January 2021, as nothing much changed in the government's approach to the crisis, Iv's Ministers sent PM Conte a four-page letter formalizing their resignations.3 The Ministers stressed that their resignation came after Iv's proposals on how to handle the pandemic had been repeatedly ignored by the government and that the government crisis had in fact been ongoing for months by then. In the letter, they reiterated their disagreements with Conte over the frequent recourse to DPCMs and the subsequent marginalization of Parliament, the vagueness of the NRRP as well as the refusal to borrow from the ESM in an emergency context.

Despite winning a vote of confidence in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, Giuseppe Conte resigned on 26 January as he realized the coalition was worn out and lost credibility. As the government's termination followed increased intra-coalitions tensions due to issues related to the management of the pandemic crisis, H3 in the case of Italy is confirmed.

5. The Israeli government crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic

This section aims to trace the government crisis in the case of Israel (Figure 5 above). Since the Netanyahu–Gantz government was formed during the outbreak of the pandemic, investigating the presence of intra-coalition conflicts before the pandemic outbreak is not empirically feasible. The section will thus be dedicated to tracing the occurrence of intra-coalition conflicts during the pandemic crisis and the fall of the government over issues related to the management of the pandemic. Section 5.1 discusses the formation of the Netanyahu–Gantz government during the pandemic outbreak and the fragmentation of the governing coalition. Section 5.2 tests H2, examining whether intra-coalition conflicts emerged in relation to the pandemic crisis and whether this undermined the stability of the government. Section 5.3 tests H3, focusing on the government's early termination and its relation with the management of the pandemic crisis.

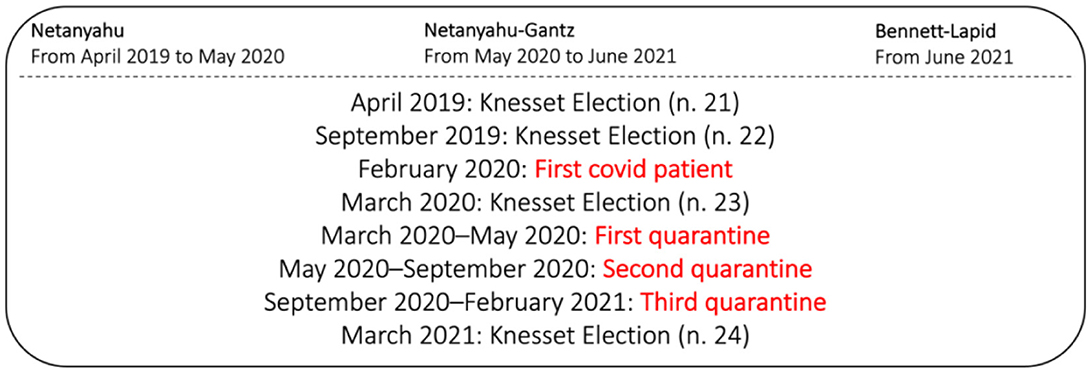

5.1. The Netanyahu–Gantz government: the formation of a fragmented coalition

Israel's 35th government was sworn in on 17 May 2020, following more than a year of political deadlock with three consecutive election cycles. Government formation was complex and highly unpredictable. The elections of the 23rd Knesset resulted in Netanyahu's Likud securing 36 seats, the party's best achievement since 2003. Despite this, the bloc of parties that opposed sitting in a government with Netanyahu won 62 seats (out of 120). After consultations with representatives of the parties, President Reuven Rivlin appointed Blue and White's Binyiamin (Beni) Gantz as formateur. Government formation was accompanied by the outbreak of the first wave of the COVID-19 in Israel, with the first infection recorded in late February and the first quarantine announced at the end of March 2020.

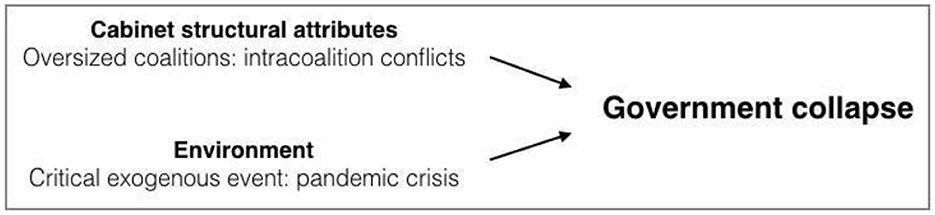

Following the outbreak of COVID-19, rival camp leaders Netanyahu and Gantz reached an agreement on the formation of a national unity government (Israel 35th government). The process of forming a government led to many party splits in the Knesset, eventually giving rise to a highly fragmented system (Table 2 above). Blue and White split into three separate parliamentary groups: Blue and White, Yesh Atid-Telem (which refused to join a government with Netanyahu), and Derekh Eretz (composed of only two MKs), which split from Telem and joined the 35th Israeli government. On the other hand, The Jewish Home, composed of only one MK, split from Yamina after the latter decided to join the opposition. As a result, the Netanyahu-Gantz government was composed of eight parties: Likud, Blue and White, Shas, United Torah Judaism, Israeli Labor Party, Derekh Eretz, Gesher and The Jewish Home. Each party, in turn, was affiliated either to the Likud or Blue and White governmental bloc. The government was oversized and consisted of no <33 ministers, setting a new record in Israeli politics.

The coalition agreement required the two major parties to share equal powers. Gantz and Netanyahu took turns as prime ministers in a so-called “rotation government”. Under the terms of the agreement, Netanyahu was to be prime minister until October 2021, with Gantz serving as vice prime minister. Subsequently, the two leaders were to exchange roles. The rotation government was based on the parity principle, whereby the two blocs would have an equal number of representatives and equal voting powers. It was agreed that the number of ministers identified as affiliated to the prime minister should be equal to the number of ministers identified as affiliated to the alternate prime minister. The parity principle between the blocs was also reflected in the fact that only the head of each governmental bloc could dismiss ministers from his own bloc. Each head of the bloc would also have veto powers over important decisions of the head of the other bloc [Section 13A (d) (1) of Israel's Basic Law]. Crucially, a common consequence of the parity principle is that governing becomes more difficult and vetoes between each bloc become the dominant pattern (Rahat and Hazan, 2005).

5.2. Intra-coalition conflicts during the pandemic crisis in Israel

From the beginning, the Netanyahu–Gantz government was characterized by high mutual distrust between Blue and White and Likud. While a national oversized unity government was necessary to deal with an emergency and resolve a severe political deadlock, it eventually led to disagreements between the coalition partners, creating political uncertainty and unpredictability in inter-party interactions. The greatest conflict between coalition partners concerned the state budget. The written agreement between the Likud and Blue and White stipulated that by August 15, 2020, the governing parties would pass the state budget, including special funds for dealing with the pandemic crisis. The budget would be biennial and apply for 2020 and 2021. However, already in the early days of the government's life, the Likud bloc changed its position and claimed that a budget should be approved for 2020 only, as the budgetary needs for 2021 would ultimately depend on the pandemic development.

Even so, the Blue and White bloc expressed opposition to the 2020 budget, deemed ineffective to meet citizens' needs. Importantly, according to Israel's Basic Law, failure to approve a state budget within the first 3 months of a fiscal year leads to government termination and early elections. In this light, a postponement of the 2021 budget provided Netanyahu with an alibi to dissolve the government and manage the transition period from the chief executive post (The Marker 2020).4 Due to continued disagreement over the biennial budget, the coalition partners temporarily stuck to the budgetary priorities set in the previous 2019 budget law and extended the deadline for approving the following budget law by an additional 120 days through the so-called “Hauser compromise” (The Jerusalem Post, 2021).

Soon, the management of the pandemic became so salient that it often led to tensions within the same party, as the case of Likud's Yifat Shasha-Biton shows. MK Shasha-Biton was appointed chairwoman of the Knesset's Coronavirus Committee. In her role, Shasha-Biton systematically opposed the governmental policy on the pandemic and opposed most of the government decisions brought to the committee. This opposition caused great embarrassment in Netanyahu's party. On 28 July 2020, after defying the government's decision to close gyms and swimming pools due to the COVID-19 spread, Shasha-Biton lost many powers deriving from her committee's post, ending two tumultuous months as panel chair.5 Intra-party conflicts within the Likud intensified after Shasha-Biton received support for her activity as chair of the Coronavirus Committee from Likud MK Gideon Sa'ar. Tensions culminated in the establishment of an alliance between Shasha-Biton and Sa'ar, giving rise to the New Hope party (The Jerusalem Post, 2020a).

Intra-coalition conflicts between Likud and Blue and White became particularly evident over the COVID-19 management. Shortly before the provision of the second quarantine in Israel, five government meetings aimed at dealing with the pandemic were canceled. The coalition struggled to find a common solution to the issue, paving the way for State Comptroller Matanyahu Englman's criticisms. In his report, he underlined dramatic shortcomings in the decision-making of the government,6 emphasizing that in the discussions between the government and the Corona cabinet,7 there was no orderly procedure for controlling and monitoring the decisions of the Prime Minister.8 Moreover, according to Englman, the lack of a state budget for 2020 caused grave damage to the country and impaired the state's decision-making in times of crisis. Crucially, in his report, Englman stressed how during the pandemic, the Likud-Blue and White coalition failed to convene even once, disregarding measures recommended by the National Health Council to reduce the country's swelling infection rate (YNET, 2021).

The next major crisis of Israel's 35th government followed Netanyahu's decisions over the second COVID-19 quarantine. In September 2020, during the Jewish Tishrei holidays, COVID-19 cases considerably increased. Therefore, the government decided to impose a general lockdown. Once again, both intra-party and inter-party conflicts emerged. The lockdown implementation fuelled the conflict between Netanyahu and the ultra-orthodox components of the Likud bloc. In a letter to the Prime Minister, Yaakov Litzman of United Torah Judaism announced his resignation as Minister of Housing, claiming that the lockdown “would prevent worshipers, including tens of thousands of Jews who don't go to a synagogue during most of the year, from attending the most important and well-attended Jewish services of the year” (The Times of Israel, 2020a). The rise of pandemic-related conflicts within the governing coalition validates H2 in the case of Israel.

5.3. Government crisis in Israel: the fall of the Netanyahu-Gantz cabinet

The Israeli government crisis unfolded between October and December 2020. In early October, Blue and White's Minister of Tourism Assaf Zamir also resigned from the government after voting against two packages of pandemic-related restrictions (The Jerusalem Post, 2020b). Upon resignation, he declared that the cabinet's approval of regulations limiting citizens' protests were the “final straw” for him. The resignation of Zamir accelerated the government's downfall.9 Taking the side of Zamir, Gantz soon admitted that “in recent weeks we have had long and honest conversations that expressed the common feelings of many in the government, in the Knesset and in every home in Israel. We wanted unity but this is not the government we wished for” (The Times of Israel, 2020b).

In December 2020, the 120-day extension for approving the budget came to an end. The government had to make a clear decision on the issue. After several attempts, with Gantz accusing Netanyahu of dragging his feet and potentially harming the country (The Times of Israel, 2020c), the ruling coalition failed to reach an agreement. Gantz criticized Netanyahu during a Knesset session declaring that “the citizens of Israel are looking at us […] they are looking for a government that will make peace at home, a functioning government that will serve them during the most difficult crisis we have face in decades” (The Times of Israel, 2020c). Yet, when the deadline for approving the budget expired, the Knesset was automatically dissolved by law and the country got back into turmoil. Because of the technical dissolution of the government, Netanyahu remained Prime Minister for caretaking responsibilities until the elections of the 24th Knesset.

The 35th government was formed to deal with the COVID-19 crisis, alongside a year-long political deadlock. Had it not been for the pandemic, it is unlikely that these parties would ever have joined forces. However, the COVID-19 crisis also urged the government to work quickly and efficiently to face the pandemic. The government failed to do so because of heated intra-coalition conflicts deriving from its configuration as an oversized coalition, which made it harder for the government to implement effective actions to contrast the pandemic crisis. Specifically, Likud suffered from internal splits while the frictions between the two coalition blocs gradually became unsolvable. The parity principle ended up producing an inflated government, made up of two quarrelsome blocs, which ultimately led to poor conduct and paralysis. As a consequence, interactions between the two blocs, and particularly between Netanyahu and Gantz, worsened throughout the government's course, leading to increased political instability. This confirms H3 in the case of Israel.

6. A comparison between Italy's and Israel's government crises: what determinants?

The comparison between Italy's and Israel's government crises during the COVID-19 pandemic contributes to our understanding of the explanatory role of cabinets structural attributes and the outbreak of unexpected exogenous crises in producing early government termination in contemporary consensual democracies.

The analysis in this paper has focused on the Conte II government in Italy (September 2019–January 2021) and on the Netanyahu–Gantz government in Israel (May 2020–June 2021), both featuring an oversized coalition. The Conte II government was sworn in before the outbreak of the pandemic. Since its formation, the oversized nature of the cabinet favored the emergence of several divergencies among coalition partners, particularly in relation to the reform of the electoral system and the criminal justice system. Such divergencies testify to the structural inconsistency of oversized coalitions with government stability even in “normal times”, as often conflicting governing parties tend to argue about government action and mutually perceive each other as unnecessary for the government's tenure [H1].

Israel's Netanyahu-Gantz government was formed during the explosion of the pandemic. The handling of the crisis fostered distrust and disagreements among coalition partners, mostly with respect to the adoption of restrictive measures and the state budget, including special funds for dealing with the pandemic emergency. At the same time, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic only contributed to exacerbating tensions within the Conte II government in Italy. As the management of the pandemic assumed greater political salience, the governing coalition started dividing itself over Conte's unilateral use of DPCMs to impose restrictive socio-economic measures (including national lockdowns), the opportinuty to resort to the ESM pandemic credit line, and the elaboration of the NRRP to benefit from the EU recovery programme.

The rise and worsening of intra-coalitional relations in Israel and Italy following the pandemic outbreak corroborates the role of critical exogenous events in undermining government stability as crisis-management becomes a key component of decision-making and the post-electoral agreement between governing parties loses traction [H2].

With the consolidation of a state of emergency in Italy and Israel, contrasting views within the Conte II and the Netanyahu-Gantz governments on how to cope with the pandemic crisis prompted explosive intra-coalition tensions, ultimately leading to a government crisis. In Italy, a political controversy over the activation of ESM pandemic loans and the content of the national recovery plan resulted in Renzi's Iv withdrawing support for the government, which precipitated the cabinet fall. Despite winning a vote of confidence in both houses of Parliament, Conte indeed resigned as PM as he realized the coalition was worn out and lost the necessary credibility to deal with such an extraordinary crisis. In Israel, pandemic crisis management became so salient that political disagreements on how to deal with the crisis emerged not only between the several parties of the governing coalition but also within the majority party, Netanyahu's Likud. Tensions arising from Netanyahu's intention to impose further restrictive measures led to resignations of cabinet members and hampered the government's ability to reach an agreement on the state budget, thus causing its fall. In both the Italian and the Israeli case, the oversized coalition type made the cabinet vulnerable to disagreements between the several governing parties. Such disagreements became untenable following the outbreak of the pandemic, leading to a government crisis over issues related to the management of the health emergency [H3].

7. Conclusion

This article has presented the trajectories of the government crises in Italy and Israel during the pandemic. Specifically, it has investigated the role of the cabinets” oversized nature and the COVID-19 pandemic in determining the early fall of the government. The article has shown that in both Italy and Israel the oversized cabinet fell prey to internal conflicts between coalition partners culminating in a government crisis over the management of the pandemic.

In Italy, the Conte II government including the M5S, PD and LeU took over before the pandemic outbreak in September 2019. Soon after its inauguration, intra-coalition conflicts emerged following Renzi's decision to leave the PD and establish Iv as a separate parliamentary group. At this stage, tensions between the coalition partners focused on the reform of the electoral law and criminal justice system, undermining the credibility of the governmental action. The sudden spread of the coronavirus further intensified intra-coalition conflicts as the governing parties bickered over the frequent use of DPCMs by the Prime Minister, the question of whether to activate ESM credit lines and the allocation of EU funds in the Italian NRRP. In January 2021, due to such disagreements, Iv withdrew support for the government, precipitating the cabinet fall. Indeed, despite winning a vote of confidence in both houses of Parliament, Giuseppe Conte resigned on 26 January as he realized the coalition was worn out and lost credibility.

In Israel, the Netanyahu-Gantz oversized coalition was formed during the pandemic outbreak. The cabinet type jeopardized the successful management of the crisis, producing conflicts both within the single parties and between the two governing blocs. Such conflicts concerned two main domains: the approval of the state budget and pandemic-related restrictive measures. Despite the provisions adopted to solve disputes within the coalition (e.g., parity norms), the lack of party discipline undermined the effectiveness of government action, leading to criticisms from the State Comptroller and to several defections from the cabinet members. The two government blocs ultimately failed to find an agreement on the state budget, which determined the government crisis.

Tracing the outbreak of the government crises in the two countries, the article suggests that oversized coalitions tend to be structurally averse to government stability for the several governing parties struggle to find a common line for policy making and mutually perceive each other as unnecessary for the government tenure. This is especially true in times of crisis, when key decisions with existential implications are to be taken, thus increasing the scope for intra-coalition conflicts.

Theoretically, the study has emphasized the added value of combining two approaches—the “coalition life cycle” and the “events”—in exploring the patterns of government instability in consolidated parliamentary democracies.10 In particular, the analysis in this study suggests that cabinet structural attributes and events alone cannot offer a comprehensive account of government dissolution. The paper has thus provided a plausibility probe to the argument that, when combined, a cabinet's configuration as an oversized coalition and the outbreak of critical exogenous events can qualify as a joint sufficient condition for government crises in the form of early cabinet's termination.

Along these lines, further research is needed to go beyond the exploratory effort made in this study. In particular, future work may seek to assess the relative explanatory power of cabinets' structural attributes and contingent events in determining government crises by focusing on a larger number of cases and the use of quantitative methods, including regressions. Moreover, investigating the impact of alternative crises—e.g., terrorism, wars, and fiscal crises—on government stability would be key to assessing whether the theoretical mechanisms identified in this study apply beyond the case of the pandemic and to what extent unexpected events can lead up to government termination when coupled with structural attributes such as the presence of oversized coalitions.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Before the outbreak of the pandemic, governments across Europe were severely subject to fiscal consolidation paradigms, mainly deriving from European institutions, affecting budgetary programmes (Fabbrini and Zgaga, 2019; Capati and Improta, 2021).

2. ^This applies to Italy only as the 35th Israeli government was formed during the pandemic crisis.

3. ^Bellanova, Bonetti and Scalfarotto's resignations were announced during a press conference at the Chamber of Deputies on the same day.

4. ^See: “The Likud violates the coalition agreement precisely around the budget,” The Marker, 18 June 2020.

5. ^‘Netanyahu fires the chairwoman of the Corona committee, Yifat Shasha-Biton', The Calcalist, 18 July 2020 [in Hebrew].

6. ^‘The budget farce: the Supreme Court ordered the government to justify the rejection of its approval', Globes, 24 November 2020 [in Hebrew].

7. ^The Israeli Corona Cabinet is a panel of experts appointed to advise the government regarding the health emergency.

8. ^See in this regard: Shakuf: ‘Crisis of Trust: 70 Government failures in managing the Corona crisis' [in Hebrew].

9. ^See ‘Minister Assaf Zamir resigns from the government: “Anxious that the state is on the verge of a complete rupture', YNET, 2 October 2022 [in Hebrew].

10. ^Both Italy and Israel are democracies born after the end of World War II.

References

Anckar, C. (2008). On the applicability of the most similar systems design and the most different systems design in comparative research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 11, 389–401. doi: 10.1080/13645570701401552

Andersson, S., Aylott, N., and Eriksson, J. (2022). Democracy and Technocracy in Sweden's Experience of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Polit. Sci. 4, 832518. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.832518

Angelucci, D., and De Sio, L. (2021). Issue characterization of electoral change (and how recent elections in Western Europe were won on economic issues). Italian J. Elect. Stud. 84, 45–67. doi: 10.36253/qoe-10836

Avvenire (2020). Coronavirus. Renzi controcorrente: apriamo, col virus bisogna convivere. Available online at: https://www.avvenire.it/attualita/pagine/renzi-controcorrente-apriamo-col-virus-bisogna-convivere (accessed March 28, 2022).

Beach, D., and Pedersen, R. B. (2013). Process Tracing Methods: Foundations and Guidelines. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.2556282

Bennett, A., and Checkel, J. T. (2015). Process Tracing: From Metaphor to Analytic Tool. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139858472

Bergman, T., Back, H., and Hellström, J. (2021). Coalition Governance in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198868484.001.0001

Bobba, G., and Hubé, N. (2021). Populism and the Politicization of the COVID-19 Crisis in Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-66011-6

Bormann, N. C. (2019). Uncertainty, cleavages, and ethnic coalitions. J. Polit. 81, 471–486. doi: 10.1086/701633

Browne, E. C., Frendreis, J. P., and Gleiber, D. W. (1984). An “events” approach to the problem of cabinet stability. Compar. Polit. Stud. 17, 167–197. doi: 10.1177/0010414084017002003

Bull, M. (2021). The Italian government response to COVID-19 and the making of a Prime Minister. Contemp. Italian Polit. 13, 149–165. doi: 10.1080/23248823.2021.1914453

Capati, A., and Improta, M. (2021). Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde? The approaches of the conte governments to the European Union. Italian Polit. Sci. 16, 1–22.

Capati, A., Improta, M., and Trastulli, F. (2022). COVID-19 and party competition over the EU: Italy in early pandemic times. Eur. Polit. Soc. 20, 170. doi: 10.1080/23745118.2022.2095170

Cavalieri, A. (2023). Italian Budgeting Policy: Between Punctuations and Incrementalism. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-15447-8

Corriere della Sera (2020a). Recovery Fund, ecco il mio piano. Coinvolgeremo tutto il Parlamento. Available online at: https://www.corriere.it/politica/20_novembre_30/conte-sul-recovery-fund-coinvolgeremo-tutto-parlamento-rimpasto-non-possiamo-rincorrere-ambizioni-ff9d8af2-327f-11eb-832d-b62d64755cfe.shtml (accessed November 30, 2022).

Corriere della Sera (2020b). Il colloquio di Renzi per convincere Conte a fare subito il rimpasto. Available online at: https://www.corriere.it/politica/20_novembre_27/colloquio-renzi-convincere-conte-fare-subito-rimpasto-73e8dab6-30fe-11eb-b439-4fc5a36ba8fd.shtml (accessed November 20, 2022).

Crulli, M. (2022). Unmet expectations? The impact of the Coronavirus crisis on radical right populism in North-Western and Southern Europe. Eur. J. Cult. Polit. Sociol. 10, 379–401. doi: 10.1080/23254823.2022.2138483

De Vries, C. E., Bakker, B. N., Hobolt, S. B., and Arceneaux, K. (2021). Crisis signaling: how Italy's coronavirus lockdown affected incumbent support in other European countries. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 9, 451–467. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2021.6

Di Mauro, D., and Verzichelli, L. (2019). Political elites and immigration in Italy: party competition, polarization and new cleavages. Contemp. Italian Polit. 11, 401–414. doi: 10.1080/23248823.2019.1679960

Erhardt, J., Freitag, M., Filsinger, M., and Wamsler, S. (2021). The emotional foundations of political support: how fear and anger affect trust in the government in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 27, 339–352. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12462

Fabbrini, S., and Zgaga, T. (2019). Italy and the European Union: the discontinuity of the Conte government. Contemp. Italian Polit. 11, 280–293. doi: 10.1080/23248823.2019.1642657

Giovannini, A., and Mosca, L. (2021). The year of covid-19. Italy at a crossroads. Contemp. Italian Polit. 13, 130–148. doi: 10.1080/23248823.2021.1911026

Grofman, B., and Van Roozendaal, P. (1997). Modelling cabinet durability and termination. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 27, 419–451. doi: 10.1017/S0007123497000203

Hale, T., Angrist, N., Goldszmidt, R., Kira, B., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., and Tatlow, H. (2021). A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 529–538. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8

Hazan, R. Y. (1996). Presidential parliamentarism: Direct popular election of the Prime Minister, Israel's new electoral and political system. Elect. Stud. 15, 21–37. doi: 10.1016/0261-3794(94)00003-4

Hazan, R. Y. (1999). Religion and politics in Israel: The rise and fall of the consociational model. Israel Affairs 6, 109–137. doi: 10.1080/13537129908719562

Hazan, R. Y., Dowty, A., Hofnung, M., and Rahat, G. (2021). The Oxford Handbook of Israeli Politics and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190675585.001.0001

Heller, W. B. (2001). Making policy stick: why the government gets what it wants in multiparty parliaments. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 780–798. doi: 10.2307/2669324

Ignazi, P., and Wellhofer, S. (2017). Territory, religion and vote: nationalization of politics and the Catholic party in Italy. Italian Polit. Sci. Rev. 47, 21–43. doi: 10.1017/ipo.2016.20

King, G., Alt, J. E., Burns, N. E., and Laver, M. (1990). A unified model of cabinet dissolution in parliamentary democracies. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 12, 846–871. doi: 10.2307/2111401

Kirsch, W., and Langner, J. (2010). Power indices and minimal winning coalitions. Soc. Choice Welf. 34, 33–46. doi: 10.1007/s00355-009-0387-3

La Repubblica (2020a). Renzi: “La crisi imporrà il Mes. Il governo? Va avanti ma serve più competenza. Available online at: https://www.repubblica.it/politica/2020/07/25/news/renzi_la_crisi_imporra_il_mes_la_legislatura_va_avanti_ma_non_so_con_quale_governo_-301036239/ (accessed July 25, 2022).

La Repubblica (2020b). Prescrizione, Pd e M5S bocciano l'emendamento Costa. Available online at: https://www.repubblica.it/politica/2020/01/15/news/prescrizione_pd_e_m5s_bocciano_in_commissione_l_emendamento_costa_italia_viva_vota_con_le_opposizioni-245857536/ (accessed 9 March 2022). 15 January.

La Repubblica (2020c). Covid, Renzi boccia il DPCM: “Errore chiudere i luoghi di cultura”. Zingaretti ai ministri: “Intollerabile chi ha i piedi in due staffe”. Available online at: https://www.repubblica.it/politica/2020/10/26/news/covid_dpcm_chiusure_ristoranti_protesta_regioni-271914676/ (accessed October 26, 2022).

La Repubblica (2020d). Conte: “Lotteremo fino alla fine per gli eurobond”. E sul Mes: “Non è adeguato, l'Italia non ne ha bisogno. Falsità da Salvini e Meloni”. Available online at: https://www.repubblica.it/politica/2020/04/10/news/mes_m5s_reazioni_governo_eurogruppo-253624810/ (accessed April 10, 2022).

La Repubblica (2020e). Direzione Pd, Zingaretti: “No a contrapposizione con Conte, ma al governo serve salto di qualità”. Available online at: https://www.repubblica.it/politica/2020/06/08/news/direzione_pd_zingaretti-258701183/ (accessed June 8, 2022).

La Stampa (2020a). Legge elettorale, depositato il Germanicum. Cosa prevede la proposta del M5S. Available online at: https://www.lastampa.it/politica/2020/01/09/news/legge-elettorale-depositato-il-germanicum-cosa-prevede-la-proposta-del-m5s-1.38307612/ (accessed January 9, 2023).

La Stampa (2020b). Accordo sulla prescrizione. Ma è scontro Conte-Renzi: governo in bilico. Available online at: https://www.lastampa.it/politica/2020/02/13/news/italia-viva-nuovo-voto-con-le-opposizioni-scontro-con-il-pd-orlando-se-il-governo-cade-si-torna-alle-urne-1.38464753/ (accessed February 13, 2023).

Laver, M., and Shepsle, K. A. (1998). Events, equilibria, and government survival. Am. J. Polit. Science 28–54. doi: 10.2307/2991746

Lippi, A. (2011). Evaluating the “quasi federalist'programme of decentralisation in Italy since the 1990s: a side-effect approach. Local Govern. Stud. 37, 495–516. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2011.604543

Lowell, A. L. (1896). Governments and Parties in Continental Europe. London: Longmans Greens. doi: 10.4159/harvard.9780674600157

Mahoney, J. (2015). Process tracing and historical explanation. Secur. Stud. 24, 200–218. doi: 10.1080/09636412.2015.1036610

Marangoni, F., and Vercesi, M. (2014). “The government and its hard decisions: how conflict is managed within the coalition,” in The Challenge of Coalition Government (London: Routledge) 17–35.

Meireles, F. (2016). Oversized government coalitions in Latin America. Brazil. Polit. Sci. Rev. 10, 32. doi: 10.1590/1981-38212016000300001

Newell, J. L. (2021). Italy and beyond at the start of 2021. Contemp. Italian Polit. 13, 1–3. doi: 10.1080/23248823.2021.1878661

Plescia, C., and Kritzinger, S. (2022). When marriage gets hard: intra-coalition conflict and electoral accountability. Compar. Polit. Stud. 55, 32–59. doi: 10.1177/00104140211024307

Rahat, G., and Hazan, R. Y. (2005). Lessons from the Israeli experience with a national unity parity coalition. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Israel.

Renzi, M. (2020). Letter to PM Giuseppe Conte. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com/matteorenziufficiale/posts/10158272595529915 (accessed December 17, 2022).

Saalfeld, T. (2008). “Institutions, chances and choices: the dynamics of cabinet survival in the parliamentary democracies of Western Europe,” in Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining: The Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe, eds. K. Strøm, W. Müller, T. Bergman (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Stinnett, D. M. (2007). International uncertainty, foreign policy flexibility, and surplus majority coalitions in Israel. J. Confl. Resol. 51, 470–495. doi: 10.1177/0022002707300183

Strøm, K., Müller, W. C., and Bergman, T. (2008). Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining: The Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, M., and Herman, V. (1971). Party systems and government stability. Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 65, 28–37. doi: 10.2307/1955041

The Jerusalem Post (2020a). Shasha-Biton joins Sa'ar, gives new pary huge boost in polls. Available online at: https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/politics-and-diplomacy/vote-on-knesset-dispersal-delayed-again-652222 (accessed December 15, 2022).

The Jerusalem Post (2020b). Blue and White minister Assaf Zamir quits government. Available online at: https://www.jpost.com/breaking-news/tourism-minister-asaf-zamir-quits-government-644279 (accessed October 2, 2022).

The Jerusalem Post (2021). Court slams Knesset for budget delay-law, warns of unconstitutionality. Available online at: https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/high-court-sort-of-nixes-basic-law-for-first-time-668909 (accessed May 23, 2022).

The Times of Israel (2020a). Housing Minister Litzman resigns in protest of looming holiday lockdown. Available online at: https://www.timesofisrael.com/housing-minister-litzman-resigns-in-protest-of-looming-holiday-lockdown/ (accessed September 13, 2022).

The Times of Israel (2020b). Blue and White Minister quits, citing Netanyahu's skewed focus, curbs on rallies. Available online at: https://www.timesofisrael.com/blue-and-white-minister-resigns-citing-new-restrictions-on-protests/ (accessed October 2, 2022).

The Times of Israel (2020c). Gantz urges Netanyahu to avert budget disaster, warns early elections nearing. Available online at: https://www.timesofisrael.com/gantz-urges-netanyahu-to-avert-disaster-agree-on-passing-a-budget/ (accessed November 10, 2022).

Warwick, P. (1979). The durability of coalition governments in parliamentary democracies. Compar. Polit. Stud. 11, 465–498. doi: 10.1177/001041407901100402

Warwick, P. (1994). Government Survival in Parliamentary Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511528132

Woldendorp, J., Keman, H., and Budge, I. (1998). Party government in 20 democracies: An update (1990–1995). Eur. J. Polit. Res. 33, 125–164. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00378

YNET (2021). State watchdog report slams handling of Covid under Netanyahu. Available online at: www.ynetnews.com/article/rjozesi11f (accessed August 31, 2022).

Keywords: government crises, COVID-19, oversized coalitions, Italy, Israel

Citation: Capati A, Improta M and Lento T (2023) Ruling in turbulent times: government crises in Italy and Israel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1151288. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1151288

Received: 25 January 2023; Accepted: 13 July 2023;

Published: 27 July 2023.

Edited by:

Xavier Romero Vidal, University of Cambridge, United KingdomReviewed by:

Mirko Crulli, University of Pisa, ItalyRoula Nezi, University of Surrey, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2023 Capati, Improta and Lento. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marco Improta, bWltcHJvdGFAbHVpc3MuaXQ=

Andrea Capati

Andrea Capati Marco Improta

Marco Improta Tal Lento

Tal Lento