- 1Department of Politics and International Relations, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield, United Kingdom

- 2The Department of Politics, The School of Social Sciences, The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

Political campaigns are increasingly described as data-driven, as parties collect and analyse large quantities of voter data to target their campaign messages in ever more granular ways, particularly online. These practices have increasingly been facing calls for greater regulation due to the range of harms they are seen to pose for citizens and democracy more generally. Such harms include the intrusions on voter privacy, reduced transparency in how messages are constructed and targeted at voters and exposure to increasingly divisive and polarizing political content. Given that data-driven campaigning (DDC) encompasses a range of different practices that are likely to fall under the remit of multiple agencies, it is not evident how suitable current regulatory frameworks are for addressing the harms associated with the growth of DDC. This paper takes a first step toward addressing that question by mapping an emergent regulatory “ecosystem” for DDC in the particular case of the UK. Specifically, we collect and analyse interview data from a range of regulators working directly or indirectly in the election campaigns and communication arena. Our analysis shows that while privacy violations associated with DDC are seen by regulators to be largely well covered by current legislation, other potential harms are given lesser to no priority. These gaps appear to be due to regulators lacking either the powers or the incentives to intervene.

Introduction

Election campaigns are increasingly referred to as data-driven (Kruschinski and Haller, 2017; Baldwin-Philippi, 2019; Bennett and Lyon, 2019; Dommett, 2019). In doing so scholars are seeking to capture a shift by political parties and other campaigning bodies toward the accrual and processing of vast amounts of often personal voter data that is used to target their campaign interventions in ever more granular ways (Rubinstein, 2014). This is particularly true for online campaigning, where campaigners can combine the information they already possess on individual voters; such as voting records, polling data and demographic details with digital trace data, allowing them to deliver highly personalized political messages to individual voters (Borgesius et al., 2018).

The growing use of such practices and their association with democratic problems such as increased voter surveillance, misinformation campaigns and the circulation of conspiracy theories, has led to calls for greater regulation in the United Kingdom (UK), as well as other Western democracies (e.g., Rose, 2017; Shiner, 2019; Dommett, 2020). In particular this is due to claims that parties' use of data brings increased potential for a range of different societal harms. These harms include (i) the potential for voters' privacy to be compromised, (ii) giving parties greater opportunities to campaign in an untransparent way, (iii) the fragmentation of political discourse, (iv) the increased threat of harmful campaign messages and (v) exacerbating the inequality in parties' campaigning resources (Borgesius et al., 2018; Morgan, 2018; Bennett and Lyon, 2019). It is within this context that more interventionist measures have been raised as potential solutions to mitigate these harms (Rose, 2017; Harker, 2020).

Whilst such calls are becoming a feature of debates around data-driven campaigning (DDC), it is not clear what such a regulatory approach would look like in practice. This is in part due to a lack of clarity surrounding existing regulatory arrangements. Within the UK and other countries, the use of data within elections falls within the purview of multiple regulatory bodies (Dommett and Zhu, 2022), and academic research has hitherto not examined the extent to which existing arrangements can or cannot deal with the threats that DDC poses to society. Neither has there been much attention paid to the perspectives of regulators themselves, exploring how they perceive the potential harms of DDC in line with their remits and powers.

These insights are vital for assessing the prospects of any effort to promote state regulation as they reveal the degree to which existing regulatory structures are able and willing to adapt to regulate the harms associated with DDC. In this paper, we map out the ecosystem of regulatory bodies surrounding DDC that currently exists in the UK. In doing so, we first employ a documentary analysis of public materials relating to the key regulatory actors whose remit includes at least some aspect of DDC. From this we identify the data protection, electoral and media standards regulators in the UK as the key actors in this space, and examine whether their remits align with the threats posed by DDC. Following this, we conduct a series of elite interviews within and around these bodies to gather insight into how those involved in regulating DDC understand the threats posed by it, how they are currently able to address these threats, and the priorities that they believe should be pursued in future regulation.

Overall, we find that the threats associated with DDC are being regulated in a highly asymmetrical fashion in the UK. For instance, concerns around voters' privacy being compromised by campaigns collecting their personal data are addressed robustly by existing arrangements, and regulators do not view there to be major problems in this regard beyond requiring campaigns to be more transparent in how they acquire voter data. Conversely, harms related to the content of data-driven political messages do not align with the powers that regulators currently possess, and these concerns are left largely unregulated as a consequence. These findings are significant for understanding attempts to regulate DDC, in that they show there is unlikely to be a single, simple regulatory response which addresses all the concerns associated with these developments in campaigning. Rather, they show the importance of understanding that developments in regulatory practice have been enacted through existing structures, and similarly that future reform in this space is also likely to be extending the purview of bodies which currently exist. Put differently, we argue that it is important to reject an ahistorical approach when researching how DDC is regulated in practice, and to acknowledge that future reform in this space will likely be negotiated through an existing regulatory landscape rather than from a blank slate.

Data-driven campaigning: the case for regulatory intervention

The use of data in political campaigning is far from new (Hersh, 2015; Baldwin-Philippi, 2019). However, the view that campaigns are becoming increasingly “data-driven” is a more recent phenomenon (Römmele and Gibson, 2020). Early Scholarship has tended to avoid defining what precisely is meant by DDC (Dommett et al., 2023), but in a general sense they have pointed to advancements in how parties collect and analyse data (especially voter data) which have changed campaigning practices (Nickerson and Rogers, 2014). Although the specific practices adopted can vary across party and country (Dobber et al., 2017; Kefford et al., 2022), central to all accounts is the notion that data allows parties to campaign in ever more precise and efficient ways.

More pertinently to our study, most of the research in this space has focused upon the processes of DDC, which seeks to understand developments in how parties collect large quantities of data (Kefford, 2021), and how they analyse these data (Nickerson and Rogers, 2014) with the view to target voters at an ever more granular level (Harker, 2020). However, our contribution adds to the nascent literature which is more concerned with the consequences of DDC. Recent years have seen an increase in scholars noting that the various practices associated with this new brand of electioneering could pose serious threats to both the rights of voters and to the health of democracy itself (Kruschinski and Haller, 2017; Borgesius et al., 2018; Bennett and Lyon, 2019; Montigny et al., 2019; Guess et al., 2020). The Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2016 (Robinson, 2018), and subsequent public attention in particular highlighted a varied set of potential harms associated with DDC. Reviewing the extant literature, we identified the following five major threats:

1. Voter surveillance and threats to privacy

At the voter level, scholars have suggested that DDC threatens voters' privacy due to the process of data gathering and repurposing. This has led to concerns around the violation of national privacy laws (especially in Europe, Kruschinski and Haller, 2017) if data is acquired without the express consent, or knowledge of the individuals in question. These concerns have been fuelled by, amongst other things, accounts from whistleblowers associated with Cambridge Analytica who claimed they “exploited Facebook to harvest millions of people's profiles… and built models to exploit what we knew about them and target their inner demons” (Susser et al., 2019, p. 10). Despite growing consensus that the claims of Cambridge Analytica were overblown (ICO, 2020a), this way of monitoring voters' behavior and attitudes online and at scale, with the view to gain electoral advantage is said to be invasive of citizens' privacy. Bennett describes this process as “voter surveillance,” stating that “In our capacities as participants, non–participants or potential participants in the democratic electoral process, personal data is collected and processed about us for the purposes of regulating the fair and efficient conduct of elections but also in order to influence our behaviors and decisions” (2013, p. 2). For many scholars, such practices are directly cited as raising privacy concerns (Rubinstein, 2014, p. 885; Kim et al., 2018, p. 909; Montigny et al., 2019).

2. Lack of transparency

A second concern is that of transparency, and how this is limited around the practices and use of DDC. In particular, scholars have highlighted the potential for voters to be unaware as to how their data is being used, why they are being targeted with a particular campaign message, or even that targeting is occurring (Dommett, 2020). Transparency is an established principle of electoral oversight, enshrined in the UK in the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act (Political Parties Elections Referendums Act, 2000). The increasing use of digital campaign tools and the use of personal data to guide campaign communications is often deemed to lack transparency, particularly when it comes to the specifics of how and why targeting occurs (Montigny et al., 2019). This has added significance when considering that microtargeted messages are better able to reach their intended recipients without being seen by the broader public. Such messages are referred to as “dark ads” and make it harder to hold parties to account for false or incorrect claims (Harker, 2020). Moreover, they also describe a situation where the recipient of a campaign message “is unable to determine the provenance of the message and whether or not it is paid for” (Harker, 2020, p. 157; Wood, 2020, p. 521). These outcomes are seen to raise “major issues of freedom of expression, political participation, and democratic governance” (Gorwa, 2019, p. 855; Kuehn and Salter, 2020, p. 2595).

3. Fragmentation of political discourse

A third threat posed by DDC centers around the challenges it poses to the quality of democracy through fragmenting political discourse. One such way in which it does so comes through what has been termed “political redlining” which describes the use of data to identify and then target specific groups of voters - potentially leading to the exclusion of segments of the population (Kreiss, 2012; Judge and Pal, 2021). Whilst the precise incentive structure of elections varies according to electoral system (with First-Past-the-Post creating a geographic targeting incentive different to proportional electoral systems (Dobber et al., 2017, p. 6), data is seen to lead campaigners to treat citizens differently, resulting in potential inequalities in electoral experience. Particular concern has been voiced about the potential for data to lead those least engaged in the electoral process to be further excluded, resulting in deeper inequalities (Nickerson and Rogers, 2014; Rubinstein, 2014, p. 908; Pons, 2016, p. 42–3). Associated with this idea is also the notion that common public dialogue and debate is eroded, resulting in the breakdown of the common public sphere. As Gorton (2016, p. 63) has argued, the use of data “serves to undermine a healthy public sphere by individualizing, isolating, and distorting political information.”

Related to these ideas, there is concern that such an explicit focus on specific segments of the electorate creates an incentive for parties to govern in the interests of smaller and more clearly defined segments of the electorate. At one extreme, it may even serve to create a clientelist form of politics where governing parties seek to explicitly serve the interests of those voters who are perceived to be most influential in their success (Hersh, 2015; Hanretty, 2021). Even if this has always been the case to a certain extent, the increased ability to target messages to individuals or highly specific groups increases the incentive for successful parties to govern specifically in the interests of these groups. Moreover, the ability to focus more exclusively on the views of the most electoral advantageous groups means that parties are incentivised to withdraw from the “marketplace of ideas” (Ferree et al., 2002), and to in effect outsource some of their function as democratic actors to research and data specialists.

4. Content of data-driven messages

A further danger associated with data-driven campaign messages is the potential for campaigns to target divisive messages to different groups of voters (Borgesius et al., 2018; Bennett and Lyon, 2019). It is becoming increasingly possible, so the argument goes, to only expose voters to a smaller number of divisive and emotive issues (or “wedge” issues) during a campaign, thereby creating “bubbles” where like-minded voters reinforce their own views without being exposed to other perspectives in a meaningful way (Bennett and Lyon, 2019). As noted above, the potential for such messages becomes even greater if parties are able to microtarget voters, thus bypassing public scrutiny of their campaigns (Harker, 2020).

A related possibility arises in the form of misinformation, and particularly the risk that false or misleading information can be spread amongst segmented groups of voters. By reducing the oversight that comes with public deliberation, parties are presented with the opportunity to actively manipulate voters by presenting them with false information - particularly on social media platforms - with less worry that such tactics would be exposed to the wider electorate (Jamieson, 2013; Morgan, 2018; Dobber et al., 2019).

5. Inequality between parties

A fifth concern comes in the form of the potential for campaign inequalities. Running an intensive DDC requires significant resources. While in principle micro-targeting may offer smaller parties and challenger candidates the chance to reach out to under-mobilized and new niche groups, emerging studies have suggested that parties' ability to deploy DDC is affected by available resources (Kruschinski and Haller, 2017), to the benefit of large parties (Kefford et al., 2022). Indeed, Nickerson and Rogers (2014) argue “that the growing impact of data analytics in campaigns has amplified the importance of traditional campaign work” (2014, p. 71) which parties with large numbers of volunteers can do more easily. If we understand DDC as a more efficient, effective form of conducting election campaigns, then discrepancies in how well parties can adopt these practices is likely to be reflected in differences in their ability to secure successful election outcomes.

Many countries, including the UK, have arrangements in place specifically to ensure that parties cannot outspend their rivals during a campaign beyond a particular threshold (Power, 2020). Should DDC involve viewing data as a crucial resource comparable to money (Munroe and Munroe, 2018) then parties' data capacity could exacerbate inequalities between those parties who can more efficiently target and mobilize the voters they need to secure positive electoral outcomes, and those who cannot.

Cumulatively, these concerns have shaped not only academic discussion around the potential problems of DDC, they have also conditioned wider public and policy making debate (Electoral Commission, 2018a; European Commission, 2021a). As such, there have been growing calls from both within and beyond academia for regulation that responds to these varied threats. Whilst increasingly voiced, research to date has not tended to examine the capacity of existing regulatory arrangements to address the harms associated with DDC. We therefore do not know the extent to which DDC requires reform to existing structures of regulation, or whether these concerns can be adequately addressed through the systems currently in place.

Moreover, discussions of the regulation of DDC have tended not to take the perspectives of regulators themselves into consideration. This means we do not know what, if anything, regulators themselves see to be problematic about DDC, and how suitable they believe existing regulatory systems are for tackling these concerns. Although regulatory bodies have their remit set by central government, we nevertheless contend that regulators still play a role in influencing the scope of their work through feeding back to lawmakers, such as via the publication of reports or otherwise taking public stances. As such, these perspectives are crucial in understanding how regulation is shaped, and therefore envisioning the future trajectory in this space. For this reason, in this article we explore the regulatory ecosystem of data-driven campaigning in the UK, posing the following research questions:

RQ1 - What are the focus and boundaries of regulators' oversight in regards to DDC in the UK?

RQ2 - To what extent do these regulatory competencies overlap with the harms identified?

Data and methods

To examine these questions, we employed a combination of two approaches. Given that our research questions center upon (i) the boundaries of regulators insight in relation to DDC, and (ii) the extent to which they align with the specific threats that DDC poses to democracy, we began by generating a thick descriptive account of the regulatory bodies currently involved in the oversight of DDC. We first did so by drawing upon the key public documents that these regulators publish on their websites about (i) the scope of their activity and their powers and processes when it comes to regulating political campaigns (or equivalent actors) and (ii) their perspectives or research documents which outline their stance toward issues relevant to DDC, such as political advertising or the use of data in elections. This helped us set out the scope of the remits of these bodies, identifying where the boundaries of oversight lie (RQ1), and the extent to which their objectives align with the harms highlighted in the section above (RQ2).

Building on this approach, we conducted a series of semi-structured elite interviews of the regulators themselves1. Interviews of this type are especially useful when the goal is to attain insights from elites who have exclusive access to information which is not in the public domain (Dexter, 2006). In our research, interviews complement the documentary analysis in that they help us attain a richer understanding of how DDC is currently regulated in practice. Interviewees were also asked to complete a short survey in advance of the interview where they detailed the key characteristics of their regulatory body [including their powers to sanction parties for malpractice (for survey see Appendix 1)]. The interviews were approximately an hour in length, and were all carried out online using the same team of two interviewers. At the interview itself, a semi-structured interview schedule was utilized containing questions which focus on:

(i) How they problematise data-driven campaigning;

(ii) The oversight powers that they possess;

(iii) The objectives and guiding principles of their organization;

(iv) The relationship they have with other regulatory actors at the national and supranational level.

These questions allowed us to further our understanding of the alignment between regulatory bodies' competences and the harms posed by DDC (RQ2). Moreover, the survey component allowed us to capture information which related more to each body's boundaries of oversight in relation to DDC (RQ1). To achieve this, we asked respondents to detail the specific aspects of DDC which they oversee, and how DDC relates to their day-to-day activity (the full survey questionnaire is detailed in the Appendix).

For our interviews, we targeted individuals who were responsible for strategic considerations and oversight within relevant regulatory bodies. As such, the universe of potential respondents was not large, and typically we were limited to one respondent per organization. This places some limitations on our confidence that the perspective of each respondent perfectly aligns with the full range of views which can be found within the wider organization that they represent. However, given that the intention is to obtain insight into the strategy and broader organizational priorities of these bodies rather than operational insights, capturing the full range of views within these regulatory bodies was less crucial for our study. We therefore view our work as intended to generate theory and insight that can be tested through future research.

Individual respondents were identified using a combination of firstly desk research, and following this, snowball sampling from our initial interviews (Bryman, 2016). Through this, we were able to identify bodies operating exclusively in the UK, as well as their nearest counterparts working at the EU level. From this, we gathered n = 11 respondents in total. Although there is generally an absence of guidelines as to determining the appropriate size for non-probabilistic samples, this is typically seen as meeting the necessary threshold for observing common themes between responses (Guest et al., 2006). We interrogated our data by employing an inductive thematic analysis (Guest et al., 2011). This approach was especially useful for our study as we were looking to identify areas of consensus and divergence between respondents on the same theme (Anstead, 2017).

The landscape of regulation of DDC in the UK

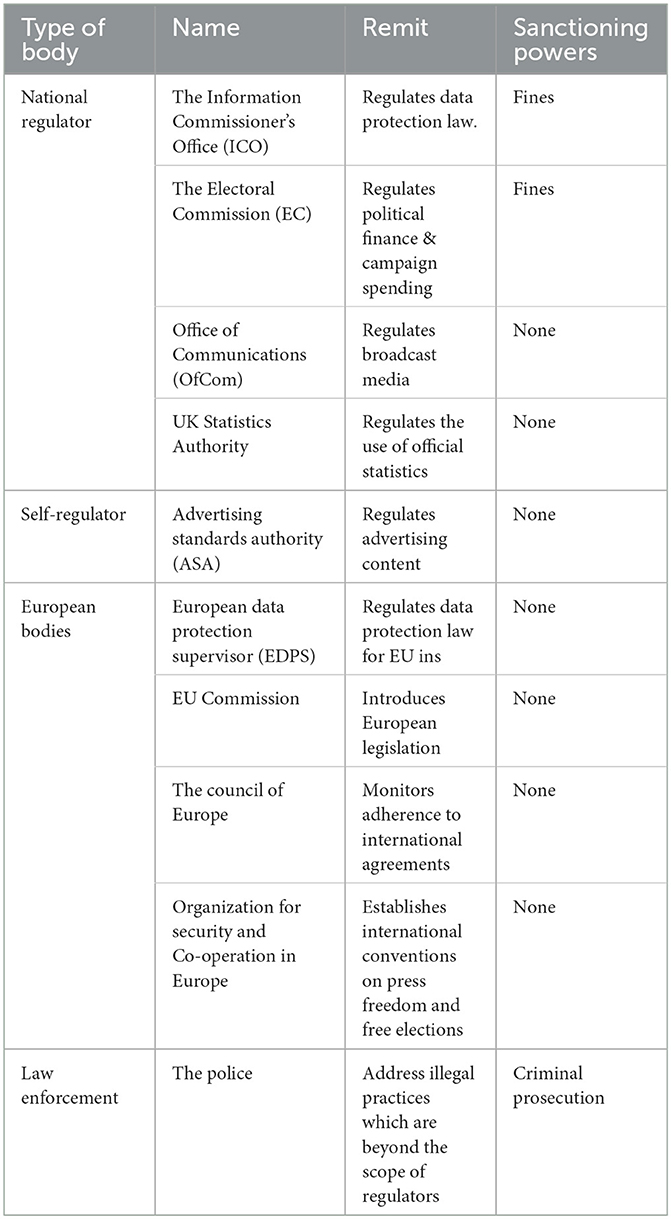

In answering RQ1, we set out to consider the focus and boundaries of the regulatory bodies operating in this space. This involved identifying an exhaustive list of regulators who have at least some interest in the regulation of DDC, before further interrogating the precise area of DDC that their oversight function relates to, and degree to which they have the authority to intervene in cases of malpractice. Building on the analysis of the regulation of online political advertising by Dommett and Zhu (2022), Table 1 presents the list of relevant regulatory bodies and adjacent organizations which we have identified as playing some role in the regulation of DDC in the United Kingdom, alongside their remit and sanctioning powers. Overall, we find ten actors with some form of oversight function. These are a combination of national regulators, which are independent bodies who attain their powers through legislation, self-regulatory bodies who are not awarded power from the state, and bodies operating at the supranational level. To build understanding of these organizations we briefly precis the remit and powers of these bodies drawing insights from our documentary analysis.

According to their response to our pre-interview survey, the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) are primarily responsible for the implementation and oversight of data-protection legislation and describe their function regarding DDC as to “regulate the processing of personal data … campaigners, parties, candidates and others responsible for processing personal data must ensure their processing is compliant with data protection law (The Data Protection Act 2018, 2018). In particular, data use must be transparent, fair and lawful” (Survey of ICO, Feb 2022). In doing so, it is granted significant sanctioning powers when enforcing compliance with this legislation. These are set out in Article 58 of UK GDPR, and include powers to conduct audits and issue fines to bodies found to be non-compliant (UK GDPR, 2018).

The Electoral Commission is the sole regulator in Britain whose remit is focused exclusively on elections and the conduct of political campaigns. However, their remit is not extended to all aspects of political activity. Their primary function is to regulate campaign finance legislation, which specifically refers to the Representation of the People Act (1983) and the Political Parties Elections Referendums Act (2000). As with the ICO, the Electoral Commission also possesses the ability to investigate and issue fines to campaigns who are non-compliant with this legislation. However, these powers are reserved for specific breaches as regards the failure to properly disclose campaign donations or spend, or for not adhering to the nationally imposed limits on campaign spending (Electoral Commission, 2022). Other breaches of electoral law “can only be investigated by the police” (Electoral Commission, 2022), and so here the Electoral Commission's role is limited to monitoring behavior.

Standards in advertising in Britain fall under the purview of multiple bodies. OfCom and the ASA are the primary two actors in this regard. OfCom are the body with the specific remit of overseeing the Communications Act (2003), and as such are the principal broadcast regulator. This gives them an important, albeit fairly limited role when it comes to regulating political campaigning; British parties are not permitted to advertise on broadcast media (i.e. television and radio) beyond specifically allocated “party political broadcasts.” OfCom have the responsibility to ensure that this ban is upheld (OfCom, 2019), but beyond this they take no further role in regulating political ads. As regards non-broadcast media, the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) would typically take a more proactive role working alongside OfCom, ensuring that ads are only making claims that are “legal, decent, honest and truthful” (ASA, 2011). However, at present, the ASA do not concern themselves with specifically political ads. This is primarily due to their function as monitoring adherence to the UK Code of Non-broadcast Advertising (CAP Code), and that ads whose “principal function is to influence voters in local, regional, national or international elections or referendums” are exempt from this code (ASA, 2021). The UK Statistics Authority also has some interest in overseeing the content of claims made within elections, specifically when it comes to the veracity of official statistics that parties use in their campaign messages. They describe this as “ensuring that statistics serve the public good also continues during an election campaign” (The UK Statistics Authority, 2020), albeit that they do not have the powers to compel parties to change their behavior in cases of perceived malpractice.

Alongside these national level bodies, there are also actors operating at the European level which have some bearing on the oversight of DDC in the UK. Amongst these are the European Commission, The Council of Europe and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), all of which are supranational bodies of which the UK are either current or former members. In terms of their relation to DDC, the Commission's role in setting regulations for EU member states was instrumental in the UK adopting its present data-protection framework through GDPR, and it continues to introduce mechanisms of oversight in this area through its “democracy and integrity of elections” initiative (European Commission, 2021b). The Council of Europe (of which the UK is still a member) does not implement regulations directly, but does uphold agreements of its member states, particularly those relating to human rights. Inclusive in such agreements is the Convention for the Protection of Individuals with Regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data (Council of Europe, 2018) which has particular relevance to DDC. The OSCE also do not introduce legally binding regulation, but it issues guidance to its member states in terms of the monitoring of election campaigns (OSCE, 2021). Unlike these three organizations, the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) are a regulatory body, acting as the independent data regulator at the pan-EU level, with the powers laid out in Article 8 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000), and similarly to the ICO at the state level, have powers to investigate and issue sanctions. However, Britain's decision to leave the European Union impacted upon their (and the European Commission's) ability to have a direct oversight role within British elections, although it remains possible that they would retain an important agenda setting role in that British institutions may emulate regulatory innovations that are made at the European level.

Cumulatively, we present a landscape where multiple organizations work toward different aspects of regulation, suggesting that there is a patchwork approach to existing oversight. This is reflective of regulatory arrangements which owe more to pre-existing structures, rather than bespoke arrangements. Moreover, whilst we identify a number of different bodies, only two of these appear to have powers to sanction campaigns in cases of malpractice, and even one of these (the Electoral Commission) can only do so in relation to the financial aspects of political campaigning. These factors raise questions about the degree to which this landscape is capable of addressing the harms identified, and about the degree to which regulators themselves think there is a need to develop new structures to respond to these specific threats.

Are the harms associated with DDC addressed by regulation?

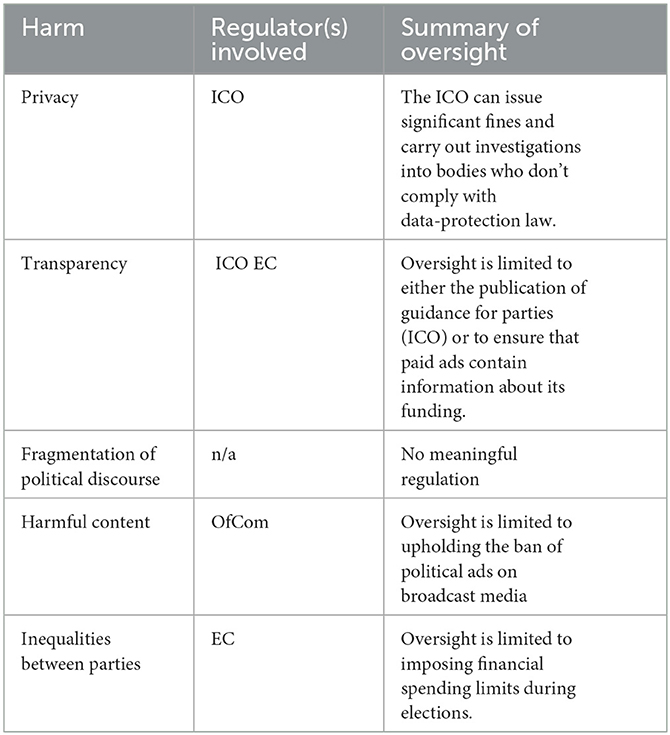

Having established the differing remits of these regulatory bodies we now turn to answer RQ2, examining the extent to which these regulatory competencies overlap with the harms identified by academics. In doing so we examine the perspectives of regulators themselves, thus gaining insight into (i) whether regulators feel able to address these harms given their existing remits, but also (ii) whether they even regard action toward addressing these harms as necessary. Taking each of the five harms identified above in turn, our interviews show DDC to be regulated in a rather asymmetric fashion. In some areas, most notably regarding privacy of citizens, regulators' perspectives align closely with the supposed threat posed by DDC, and have substantial powers to sanction parties in cases of malpractice. In several other cases, however, particularly regarding harms related to the specific content of campaign messages, we find that regulators lack either the means or the inclination to regulate these harms in a more interventionist fashion. A summary of these can be found in Table 2.

Taking first the issue of voter surveillance, and the prospect that British citizens are having their privacy compromised by the amount of personal data that parties are collecting, we find that this is a facet of DDC which is being regulated robustly. The oversight of these threats falls almost exclusively within the remit of a single regulator - the ICO - whose powers in enforcing data protection legislation are significant and enshrined in law. According to Article 58 of UK GDPR, the ICO has the ability to (i) carry out thorough investigations into bodies suspected of not adhering to data protection law, and (ii) issue reprimands and significant monetary fines in cases of proven malpractice (UK GDPR, 2018).

When reviewing the perspective of those within the ICO, we found a belief that existing arrangements are largely sufficient to deal with any threats that DDC poses to voter privacy. This is largely because they perceive their powers to be a substantial enough deterrent to prevent parties from contravening data protection law, particularly through the issuing of substantial fines. As one interviewee reflected:

“[I think] there are areas where more powers, particularly fining limits are needed. I don't think the ICO is one of those… we have quite substantial fining powers now, which are more appropriate and provide the appropriate deterrent, what we need them to do. And we also have a lot more powers in terms of audits so we can do compulsory audits and things that we didn't used to have under the Data Protections Act 1998” (Interview with the ICO, February 2022).

We also found that interviewees within the ICO doubted that the concerns surrounding DDC as regards voter surveillance are fully justified. They acknowledge that the use of analytics in politics using voter data is on the rise in both the official guidance that they have produced for political parties when campaigning online (ICO, 2020b), and their investigation into data in politics following the Cambridge Analytica scandal (ICO, 2018). At the same time, however, interviewees questioned the degree to which parties are making use of a multitude of datapoints on individual voters. Recalling the concerns of voter privacy associated with the Cambridge Analytica scandal, the ICO take a skeptical position toward (British) campaigns being able to harvest personal data en masse to form detailed profiles on individuals before catering campaign messages to their preferences. Moreover, they warn against the possibility of overreacting to these concerns, with one interviewee stating that:

“[For] the mainstream UK political parties, at the moment, some of the techniques that we've seen abroad in places, some of the techniques that may be possible in the future, they're not doing. We have no evidence that they're doing it. We have no evidence that they're considering doing it. And I think there's a lot of scaremongering in this area… I think a healthy amount of pragmatism is important in all of this” (Interview with ICO, February 2022).

As regards supranational bodies, the Council of Europe (2021) recognizes privacy and autonomy of one's personal data as a human right, but one which should be reconciled with other “human rights and fundamental freedoms, including freedom of expression” (Council of Europe, 2021). In other words, there is a trade off between preserving voter privacy whilst simultaneously preserving parties' and platforms' rights to communicate freely with citizens. The OSCE holds a similar position, as they list both upholding privacy and protecting parties' ability to communicate freely (and citizens' access to information from multiple perspectives) as key principles to uphold when observing the conduct of election campaigns on social media (OSCE, 2022).

It should be reiterated that these perspectives from the European level are only voluntary codes when it comes to how DDC is regulated in the UK. However, alongside the powers available to domestic level regulators, the evidence points toward privacy being a concern which is regulated robustly, certainly relative to the other harms identified. Britain's data regulator has sufficient powers to investigate and sanction cases of illegality, and our interview data suggests that they reject some of the grander claims of campaigns' capacity to breach voter privacy at scale.

Turning to transparency, we find less evidence that these concerns can be fully addressed by existing arrangements. Indeed, it appears that current oversight is not regarded as sufficient, with a number of interviewees citing a lack of transparency as problematic. The ICO, for example, are committed to transparency, enshrined through the UK's data-protection law (UK GDPR, 2018), and to this end they have published guidance for campaigners informing them of voters' “right to be informed” about how their data has been collected and used (ICO, 2020b). However, our interview revealed their concerns surrounding the potential for the public to lack understanding of campaigns' data practices. In particular, they describe how voters viewing ads online will tend to not be aware that they may be being targeted as a result of historical online behavior, and that “the opaque nature” of such advertising is “probably the biggest concern that the ICO has” (Interview with ICO, February 2022).

Transparency is a concern shared by the Electoral Commission, although their perspective on transparency is not limited just to the data used by campaigns. Rather, given their function regulating campaign finance, they are more concerned with ensuring that paid political advertising contains information on who has funded the ad. Their concerns around transparency led to calls for additional measures to promote this ideal, including a 2018 report where they recommend that online political ads should contain a digital “imprint,” which makes it clear who has financed it (Electoral Commission, 2018b). Our interview with the Electoral Commission elaborated on this point, saying that imprints are important so that “we can make sure that the spend on that material is being properly accounted for. But I suppose in a wider sense, that imprint requirement also provides transparency for voters, so that they know who is targeting them, who is trying to persuade them to vote in a particular way or not vote in a particular way” (Interview with the EC, April 2022).

These perspectives show that transparency is an active concern to UK regulators, but also that they believe that existing regulatory powers are insufficient to force campaigners to be fully transparent when using voter data. This suggests that transparency is an aspect of DDC which is not currently sufficiently regulated and may, therefore, be a focus of reform in the future. This is particularly notable given current efforts in the EU context to promote increased transparency, most clearly as a key principle within the Digital Services Act (2022), which suggests that a similar agenda could be adopted in the UK.

A third threat associated with DDC is its potential to lead to fragmentation of political discourse. We find that existing arrangements are perceived to be insufficient in addressing these harms, but that regulators themselves do not on the whole view this concern as a priority. The Electoral Commission in particular recognize that DDC presents opportunities for parties to deliver conflicting messages to different groups of voters. At the same time, they also stressed in their interview that there is nothing illegal about a campaign opting to make contradictory claims. Moreover, they even suggest that this isn't necessarily as problematic from an ethical standpoint as it might first appear, as they outlined in their interview:

“[I]f a political party chooses to target one angle to one group of people and another angle to another, then I don't actually see anything wrong with that… on a basic level, it does largely seem to me that it's technology enabling something that was already being done to be done in a more effective manner. And obviously you can get to a stage where a party might be telling one group of people one thing and another group the complete opposite. And I suppose that does become a concern in terms of the plurality of the debate and so on. But there is nothing in electoral law and there has never been anything in electoral law to suggest that you simply cannot do that” (Interview with the EC, April 2022).

Equally, the Electoral Commission in the same interview did recognize the potential negative impact that targeting more granular groups of voters can have for the broader health of democracy. Specifically, if DDC allows parties to be increasingly efficient in targeting the voters that they calculate are most valuable to them strategically, then this will by definition mean that citizens who fall outside of this category are less likely to be exposed to campaign interventions than otherwise would be the case. The Electoral Commission stressed in the interview that they were keen to avoid making it harder for campaigns to get their point across to voters, but equally that “[t]he flip side of efficient campaigning is some people get [fewer] campaign conversations… than they might otherwise do and the extent to which that might have a negative impact on the overall quality of the conversation around elections” is a concern (Interview with the EC, April 2022).

Ultimately however, such concerns fall outside of the Electoral Commission's sphere of oversight. We also didn't find that domestic regulators feel that additional powers are warranted to deal with these specific features of DDC. This was especially notable as our international interviewees did support such a focus. Indeed, the EDPS advocated for a blanket ban on microtargeting in EU member states (EDPS, 2022). In a broad sense, the EDPS diagnose the potential harms of DDC in similar terms to the Electoral Commission; they don't consider targeting different messages to different groups to be inherently problematic, nor do they see this as a particularly novel aspect of electioneering. As they reported in the interview: “[W]ouldn't any political candidate tailor his message according to his audience, if he is speaking at a trade union meeting or is he speaking at a fundraising gala? He might touch on different points or emphasize different parts of his party programme depending on who he's speaking to. That's, I think, probably something which is indeed an inherent and normal part of the political process” (Interview with EDPS, August 2022). The point of difference lies in the EDPS' inclination to stress the scale of the automation that lies behind this targeting. As our interviewee outlined:

“[W]hat is different about the targeting, or what I think is different about the political targeting used in these targeting techniques that you can find in the context of online advertising, is that there's a very high degree of automation and sophistication in that process which relies on information which is not something which is truly contextual like the event that you're speaking at. But really relying on information which is coming from a wide variety of sources and not least online behavior” (Interview with EDPS, August 2022).

As a consequence, the EDPS advocate a blanket ban on data-driven microtargeting, which they detail in their Opinion on the Proposal for Regulation on the Transparency and Targeting of Political Advertising (EDPS, 2022). As they explain further when interviewed, this measure is intended in part to foster a healthier political culture by ensuring that parties continue to take an active role in public deliberation. They state that banning microtargeting:

“[is] not about restricting communication with voters as such, it's not about restricting the content of those communications with voters. It's really just about making sure that we don't undermine free and fair elections or the integrity of our electoral process by creating a world where political discourse is like I said before, heavily fragmented. Where we lose track as a society of a common understanding of the platform of individual political actors, and have an exchange about what is good or what is bad from a political perspective” (Interview with EDPS, August 2022).

Of course, the EDPS' purview no longer includes the United Kingdom since the vote to leave the EU, and so it is not clear what effect that their move to ban microtargeting will have in the British context at this juncture. However, the EDPS' stance illustrates the existence of a spectrum of different models of regulation which could be adopted at the state level. In this regard, a total ban on using data to target voters at the individual level would likely represent one end of this spectrum, whereas prioritizing parties' freedom of expression when campaigning would fall toward the other. Our data therefore offers conflicting insights; in the UK regulators identify a gap but outline little intention to address this; and yet interventions at the European level suggest that such reforms may well be pursued elsewhere, offering a template that could, if attitudes change, be mirrored in the UK.

The fourth harm identified relates to the content of data-driven political messages, specifically in terms of misinformation or polarization. In some respects, regulators tend to accept that DDC does potentially pose some social harms. However, on the whole they tend to stress that regulating the content of campaign interventions is both beyond the scope of their activity and, in any case, undesirable from their perspective.

For example, a commonly discussed harm of DDC is the increased potential for the spread of misinformation and disinformation through political campaigns' advertising and other campaign interventions. This is a particular occupation of supranational bodies. The OSCE for example note their concern about “new challenges for protection of integrity of elections arising from manipulative information” during elections (2022). At the domestic level, OfCom as the UK's principal media regulator acknowledged the possibility of these harms in their case study on monitoring online advertising (OfCom, 2021). One of their statutory roles is to promote media literacy in the UK, and as a part of this they recognize the importance of “the growing need for consumers and citizens to be aware of the range of risks and opportunities involved in being online, particularly in relation to mis- and disinformation” (OfCom, 2021).

Despite recognizing the potential for harm, our interviews revealed that OfCom do not have the capability to enforce campaigns to moderate the content of their messages beyond the low threshold of what would already have been considered illegal, such as through contravening equalities legislation or libel laws2. As currently constituted, their ability to compel parties to change their campaign practices is limited to enforcing the ban on UK parties advertising on broadcast media platforms. Similarly, the Advertising Standards Authority recognize the benefit of political ads adhering to the “same standards of truthfulness” (ASA, 2019) as other forms of advertising (which they regulate) but nevertheless state that this is not an area that they take an active role in. They say this is due to the nature of political communication being different to commercial advertising, and that it would be “inappropriate, and perhaps unhelpful” for them to intervene in election campaigns (ASA, 2019). This is an important point, as it suggests that there is currently a gap in the regulatory landscape in the UK, as no regulatory body views it as their role to address concerns relating to the content of data-driven campaign messages.

In a similar vein, the regulators we interviewed also recognize the potential for DDC to lead to more divisive, polarizing messages. Nevertheless, we find once again that the powers over the content of political messages fall outside the remit of regulatory bodies, and in any case are not seen as desirable by the regulators themselves. The Electoral Commission for example describe the calls for greater intervention following controversial claims made in the 2016 referendum on EU membership. In doing so, they describe the potential for such intervention to be characterized as a “truth commission” (Interview with the EC, April 2022) given that greater intervention would mean arbitrating between what would be considered legitimate and illegitimate political discourse. Consequently, this is an aspect of DDC which, in their view, is left largely unregulated. As our interviewee explained:

‘The whole thing [the calls for content regulation] blew up again I think in the wake of the EU referendum and the infamous bus and all this kind of thing. And there was talk of … Truth Commission, this idea that there would be some body that would decide whether the words in campaign material were actually accurate or not. I don't think anyone particularly fancied dipping their toe in the water of saying, “Yes, I'm quite happy to do that job.” So it is unregulated, that's absolutely true' (Interview with the EC, April 2022).

Within this context, the stance of the EDPS to advocate a total ban on microtargeting may not be as interventionist as it first appeared. As with domestic level regulators such as the Electoral Commission, our interviews reveal that they both hold significant reservations about the prospect of regulating content on the grounds of denying campaigns their freedom of expression, a concern which we have already seen is shared by the Council of Europe and the OSCE. A total ban on microtargeting would by extension mean that such concerns are in effect bypassed as the content within political campaign messages would be exposed to a much wider group of voters, thereby inviting much greater public scrutiny. In any case, our findings suggest that there is little appetite for heavy handed regulation when it comes to the content of political messages, and that this constitutes a gap in the oversight of DDC when compared to other harms associated with it.

The final concern associated with DDC is its potential to exacerbate inequalities between parties. The Electoral Commission are tasked with ensuring a level playing field between parties from a financial perspective, and they reported being cognizant that inequalities when it comes to data can be just as important. However, their ability to act upon these concerns is limited to enforcing general spending limits which are an extremely blunt instrument when it comes to data infrastructure specifically. They addressed this point in the interview, reporting that:

‘[T]he system that we regulate around political finance, it was built around the idea of either trying to put a level playing field or a level ceiling on the money being used in politics… So I suppose sometimes it makes me think that the use of data in this way is a disruptor within all of that… [T]here could be challenges with understanding how much does it cost the different kind of campaigners to get this data. Are some of them getting it somehow for free, for favors? Are some of them much more efficient at creating it than others? And does that somehow then affect the idea of the level playing field amongst them?' (Interview with the EC, April 2022).

On the one hand, this shows that regulators do consider the inequalities between parties that could be entrenched by DDC. On the other, spending limits are a blunt instrument when it comes to preventing these inequalities. They restrict the degree to which parties can outspend their rivals on consultants, data analytics firms and other forms of digital advertising costs which are associated with data-driven campaigns. The fact that there is no mechanism specifically designed to limit inequalities in data infrastructures means that there remains ample room for parties to glean unequal amounts of value from the data that they use.

Reviewing these insights with a view to possible future regulation, we again find evidence of only partial coverage of the threats associated with DDC. We find evidence that regulatory bodies are cognizant of each of these harms that are associated with DDC. However, we find asymmetries in terms of how these threats are perceived as problematic, and similarly whether they believe that it should be their role (as they presently understand it) to act to mitigate these threats.

Discussion

Taken together, we find evidence of regulation appearing to address some of our five concerns more adequately than others. The area which appears to be best catered for as regards current regulatory arrangements is privacy, where there is a single body (the ICO) with a clear remit and significant powers to conduct oversight on data protection. However, the oversight of other concerns appears to be insufficient in other respects, and our data implies that this is true for two key reasons. The first of these relates to the powers that regulators are given, and specifically that the harms associated with DDC fall outside of these remits. We find that concerns surrounding transparency, fragmentation of political discourse, harmful advertising content and inequalities between parties are each recognized as problematic to varying degrees, but at the same time they do not fall neatly within the purview of a single regulatory body. The second reason is through a lack of ownership. Regulators are especially reluctant to involve themselves in the regulation of the content of data-driven political messages, which therefore suggests that this is being missed entirely by existing oversight arrangements.

A result of this asymmetry is that there are different challenges to the current regulatory ecosystem of DDC when it comes to addressing each of these societal harms, and that future responses to strengthen regulation must take these differences into consideration. For instance, granting additional powers to, for example, the Electoral Commission to impose a ban on campaigns microtargeting individuals may be sufficient to address concerns related to the fragmentation of political discourse. However, it is not clear that such an approach would be as effective in terms of addressing the issues relating to harmful content as there appears to be greater reticence on the part of existing regulators about taking on new competencies in this area.

Relatedly, we also found evidence of an additional factor that might inhibit the strengthening of regulation in this space. That is, whereas much of the narrative surrounding DDC to date has centered around the new threats that it poses, we find that regulators often posit DDC as presenting potential benefits to society, alongside the harms. Our interview respondents were unanimous in accepting that DDC poses at least some form of challenge to democratic societies, but they were almost equally united in acknowledging the dangers of being overly prescriptive on how campaigns can communicate with voters. On normative grounds, political campaigns are viewed as essential components of a healthy democracy, and if DDC can facilitate better quality communication, then they are reluctant to advocate a position that would impede this social good. For example, our interviewee within the ICO stated that they “would be far from saying they shouldn't be doing any of this, they shouldn't be contacting people … absolutely not, you know, democratic engagement is legitimate and it is essential in a democratic society. You have to be able to engage with the people that you want to vote” (Interview with the ICO, Feb 2022). Furthermore, regulators were also cognizant of the legal principles which would lead them to take a “light-touch” approach to DDC. Considerations of freedom of speech for example are important when it comes to whether parties should be constrained in what they can include in their messages to voters, which was the view of the Electoral Commission, where our interviewee reported that “[I]t isn't always necessarily the right thing to have everything regulated. So although it is a gap, I wouldn't necessarily argue that it's a gap that shouldn't be there so to speak. So fundamentally, this just comes down, I think, to issues around freedom of speech, which are particularly sensitive in politics” (Interview with the EC, April 2022).

This poses a final question in terms of who picks up the baton for regulation in this space if regulators themselves see all questions to do with content as outside of their remit. One possibility is that the responsibility is in effect outsourced to online platforms. Indeed, the recently published Code for Disinformation by the European Commission (2022) places much responsibility onto those platforms who sign up to monitor the content of messages, in effect establishing a self-regulatory system. As we have seen however, we also find that the EDPS are advocating a much more hands-on approach to addressing other DDC-related harms in the banning of online microtargeting. Another possibility is that the impetus for regulation could come from politicians, given that they are chiefly responsible for setting the legal remits of regulatory bodies. This could mean that even if regulators themselves are reluctant to be more interventionist toward certain threats, law-makers could nevertheless take action in this space. This raises questions about which actors are most influential in driving change between these different models of regulation, a question which requires further research.

Conclusion—What is missed through existing arrangements?

The goal of this paper has been to map the system of regulation of DDC within the context of the UK, particularly with the view of understanding the boundaries of their oversight and how well their competencies overlap with the societal harms associated with DDC. To do so we have drawn on the perspectives of key agencies whose powers encompass practices that are at the core of DDC. The exercise has revealed that oversight of DDC is fragmented, partially reflecting the separation of powers that exists among relevant regulatory bodies, but also that certain facets of DDC do not align with the powers of any regulator currently active in the UK.

An implication of this fragmentation is that there is an asymmetry in how certain harms that are associated with DDC are regulated compared to others. At one end of the spectrum, we find that the concerns that DDC poses to individuals' privacy are regulated in a robust fashion. The remit of the UK's data-protection regulator is clearly aligned with such concerns, and they possess meaningful sanctioning powers in instances where campaigns contravene data-protection law. Conversely, there are next to no arrangements that are currently in place which regulate the content of political messages during campaigns, other than the policing of illegal content which is reactive in nature i.e., citizens must refer the matter to the authorities to take action. This has significant consequences when it comes to the threats that are poised by DDC, as many of these risks are closely linked to the content of data-driven political messages. The spread of misinformation is a particularly commonly discussed concern in the academic literature on DDC, and yet regulators in the UK view the prospect of intervening to prevent such messages as both impossible and undesirable from their standpoint. As a result, these harms - alongside adjacent threats such as the risk of divisive campaign messages - are essentially ignored under current arrangements.

We find that this perspective is due largely as a consequence of regulators being reluctant to impose stronger limits on political campaigns' rights to free speech, as well as healthy skepticism that these new methods wield the subversive power claimed for them. Interestingly, we find that these perspectives have much in common with our data from European level regulators, and yet they propose much more interventionist measures than we detect amongst UK regulators. Specifically their proposal to ban online microtargeting provides an example of an entirely different model to the UK case when it comes to addressing the harms that are associated with DDC. This presents the question of whether other models of oversight are indeed in operation in other democracies outside of the UK, and if so, which are the specific activities which are regulated differently. Taking a more comparative lens to the regulation of DDC should therefore be a priority for future research.

It is also important to reiterate that areas for future reform are largely contingent on lawmakers' willingness to act in this area, although again, we contend that the perspectives of regulators in engaging with politicians and the wider public are important in influencing the direction of future oversight arrangements. This final point has all the more bearing when it comes to appreciating the importance of existing structures in determining the prospects for future reform. We have seen in this paper that the regulatory landscape for DDC has developed from established structures of oversight in the areas of data, elections and media regulation, and that this has been an important factor for the asymmetric and incremental attempts to regulate the harms posed by DDC. This acts to highlight the dangers of taking an ahistorical approach when examining regulation in this space, and the need to recognize that any future regulation is also likely to occur in a similarly incremental and fragmented fashion.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Sheffield Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AB and RG took the lead in data collection and conducting interviews. AB was responsible for the data analysis (while consulting both RG and KD) and writing an initial draft of the manuscript. RG and KD redrafted the manuscript prior to submission. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the NORFACE Joint Research Programme on Democratic Governance in a Turbulent Age and co-funded by ESRC, FWF, NWO, and the European Commission through Horizon 2020 under grant agreement No. 822166.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2023.1146470/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The topic guide used for these interviews can be found in the Appendix.

2. ^Their role in such cases would be restricted to referring these cases to the relevant authorities, rather than taking a more active role themselves.

References

Anstead, N. (2017). Data-driven campaigning in the 2015 United Kingdom general election. Int. J. Press/Politics 22, 294–313. doi: 10.1177/1940161217706163

ASA (2011). Advertising Standards Authority Committee of Advertising Practice Annual Report, 2011. Available online at: https://www.asa.org.uk/static/uploaded/371261dd-4394-4ee9-8810905042925131.pdf (accessed July 31, 2023).

ASA (2019). Why We Dont Regulate Political Ads. Available online at: https://www.asa.org.uk/news/why-we-don-t-regulate-political-ads.html (accessed July 31, 2023).

ASA (2021). The CAP Code The UK Code of Non-broadcast Advertising and Direct and Promotional Marketing. Available online at: https://www.asa.org.uk/static/47eb51e7-028d-4509-ab3c0f4822c9a3c4/1ec222e7-80e4-4292-a8d46c281b4f91b8/The-Cap-code.pdf (accessed July 31, 2023).

Baldwin-Philippi, J. (2019). The technological performance of populism. New Media Soc. 21, 376–397. doi: 10.1177/1461444818797591

Bennett, C. J., and Lyon, D. (2019). Data-driven elections: implications and challenges for democratic societies. Internet Policy Rev. 8, 4. doi: 10.14763/2019.4.1433

Borgesius, F., Möller, J., Kruikemeier, S., Fathaigh, Ó., Irion, R., Dobber, K., et al. (2018). Online political microtargeting: promises and threats for democracy. Utrecht Law Rev. 14, 82–96. doi: 10.18352/ulr.420

Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000). Available online at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf (accessed January 16, 2023).

Communications Act (2003). Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/21/contents (accessed July 31, 2023).

Council of Europe (2018). Convention for the Protection of Individuals with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data. Available online at: https://rm.coe.int/convention-108-convention-for-the-protection-of-individuals-with-regar/16808b36f1 (accessed July 31, 2023).

Council of Europe (2021). Guidelines on the Protection of Individuals With Regard to the Processing of Personal Data by and for Political Campaigns. Available online at: https://rm.coe.int/guidelines-on-data-proetction-and-election-campaigns-en/1680a5ae72 (accessed July 31, 2023).

Digital Services Act (2022). Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32022R2065andqid=1666857835014 (accessed July 31, 2023).

Dobber, T., Fathaigh, Ó. R., and Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. (2019). The regulation of online political micro-targeting in Europe. Internet Policy Rev. 8, 1440. doi: 10.14763/2019.4.1440

Dobber, T., Trilling, D., Helberger, N., and de Vreese, C. (2017). Two crates of beer and 40 pizzas: the adoption of innovative political behavioral targeting techniques. Internet Policy Rev. 6, 1–25. doi: 10.14763/2017.4.777

Dommett, K. (2019). Data-driven political campaigns in practice: understanding and regulating diverse data-driven campaigns. Internet Policy Rev. 8, 1432. doi: 10.14763/2019.4.1432

Dommett, K. (2020). Regulating digital campaigning: the need for precision in calls for transparency. Policy Internet 12, 432–449. doi: 10.1002/poi3.234

Dommett, K., and Barclay, A., and Gibson, R. (2023). Just what is data-driven campaigning: a systematic review information. Commun. Soc. 8, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2023.2166794

Dommett, K., and Zhu, J. (2022). the barriers to regulating the online world: insights from UK debates on online political advertising. Policy Internet. 4, 299. doi: 10.1002/poi3.299

EDPS (2022). Opinion on the Proposal for Regulation on the Transparency and Targeting of Political Advertising. Available online at: https://edps.europa.eu/system/files/2022-01/edps_opinion_political_ads_en.pdf (accessed July 31, 2023).

Electoral Commission (2018a). Report on an Investigation in Respect of the Leave. EU Group Limited. Available online at: https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf_file/Report-on-Investigation-Leave.EU.pdf (accessed July 31, 2023).

Electoral Commission (2018b). Digital Campaigning: Increasing Transparency for Voters. Available online at: https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf_file/Digital-campaigning-improving-transparency-for-voters.pdf (accessed July 31, 2023).

Electoral Commission (2022). Our Role as a Regulator. Available online at: https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/who-we-are-and-what-we-do/about-us/our-role-a-regulator (accessed July 31, 2023).

European Commission (2021a). European Democracy: Commission Sets Out New Laws on Political Advertising, Electoral Rights and Party Funding. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_6118 (accessed July 31, 2023).

European Commission (2021b). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Protecting Election Integrity and Promoting Democratic Participation. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0730andqid=1641368130520 (accessed July 31, 2023).

European Commission (2022). The Strengthened Code of Practice on Disinformation. Available online at: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/2022-strengthened-code-practice-disinformation (accessed July 31, 2023).

Ferree, M. M., Gamson, W. A., Gerhards, J., and Rucht, D. (2002). Four models of the public sphere in modern democracies. Theor. Soc. 31, 289–324. doi: 10.1023/A:1016284431021

Gorton, W. A. (2016). Manipulating citizens: how political campaigns use of behavioral social science harms democracy. New Political Sci. 38, 61–80. doi: 10.1080/07393148.2015.1125119

Gorwa, R. (2019). What is platform governance? Inf. Commun. Soc. 22, 854–871. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2019.1573914

Guess, A. M., Lockett, D., Lyons, B., Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., et al. (2020). “Fake news” may have limited effects beyond increasing beliefs in false claims harvard kennedy school misinformation. Review 1, 1–19. doi: 10.37016/mr-2020-004

Guest, G., Bunce, A., and Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18, 59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., and Namey, E. E. (2011). Applied Thematic Analysis. London: Sage Publications.

Hanretty, C. (2021). The pork barrel politics of the towns fund. Political Q. 92, 7–13. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12970

Harker, M. (2020). Political advertising revisited: digital campaigning and protecting democratic discourse. Legal Studies 40, 151–171. doi: 10.1017/lst.2019.24

Hersh, E. D. (2015). Hacking the Electorate: How Campaigns Perceive Voters. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

ICO (2018). Investigation Into the Use of Data Analytics in Political Campaigns. Available online at: https://ico.org.uk/media/action-weve-taken/2260271/investigation-into-the-use-of-data-analytics-in-political-campaigns-final-20181105.pdf (accessed July 31, 2023).

ICO (2020a). Letter to the DCMS Select Committee Available online at: https://ico.org.uk/media/action-weve-taken/2618383/20201002_ico-o-ed-l-rtl-0181_to-julian-knight-mp.pdf (accessed July 31, 2023).

ICO (2020b). Guidance for the Use of Personal Data in Political Campaigning. Available online at: https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-data-protection/key-dp-themes/guidance-for-the-use-of-personal-data-in-political-campaigning-1/ (accessed July 31, 2023).

Jamieson, K. H. (2013). Messages, micro-targeting, and new media technologies. Forum 11, 429–435. doi: 10.1515/for-2013-0052

Judge, E. F., and Pal, M. (2021). Voter privacy and big-data elections. Osgoode Hall Law J. 58 1–56 doi: 10.60082/2817-5069.3631

Kefford, G. (2021). Political Parties and Campaigning in Australia: Data, Digital and Field. Cham: Springer Nature.

Kefford, G., Dommett, K., Baldwin-Philippi, J., Bannerman, S., Dobber, T., Kruschinski, S., et al. (2022). Data-driven campaigning and democratic disruption: evidence from six advanced democracies. Party Politics. 2, 13540688221084039. doi: 10.1177/13540688221084039

Kim, T., Barasz, K., and John, L. (2018). Why am i seeing this ad? The effect of ad transparency on ad effectiveness. J. Consum. Res. 45 906–932 doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucy039

Kreiss, D. (2012). Acting in the Public Sphere: The 2008 Obama Campaigns Strategic Use of New Media to Shape Narratives of the Presidential Race. Media, Movements, and Political Change. New York, NY: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Kruschinski, S., and Haller, A. (2017). Restrictions on data-driven political micro-targeting in Germany. Int. Policy Rev. 6, 1–23. doi: 10.14763/2017.4.780

Kuehn, K. M., and Salter, L. A. (2020). Assessing digital threats to democracy, and workable solutions: a review of the recent literature. Int. J. Commun. 14, 2859–2610. Available online at: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/12959

Montigny, E., Dubois, P. R., and Giasson, T. (2019). On the edge of glory (… or catastrophe): regulation, transparency and party democracy in data-driven campaigning in Québec. Internet Policy Rev. 8, 1441. doi: 10.14763/2019.4.1441

Morgan, S. (2018). Fake news, disinformation, manipulation and online tactics to undermine democracy. J. Cyber Policy 3, 39–43. doi: 10.1080/23738871.2018.1462395

Munroe, K. B., and Munroe, H. D. (2018). Constituency campaigning in the age of data. Can. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 135–154. doi: 10.1017/S0008423917001135

Nickerson, D. W., and Rogers, T. (2014). Political campaigns and big data. J. Econ. Persp. 28, 51–74. doi: 10.1257/jep.28.2.51

OfCom (2019). “The OfCom Broadcasting Code.” Available online at: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/132073/Broadcast-Code-Full.pdf (accessed July 31, 2023).

OfCom. (2021). Insights for Online Regulation: a Case Study Monitoring Political Advertising. Available online at: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/212861/tools-for-online-regulation.pdf (accessed July 31, 2023).

OSCE (2021). Guidelines for Observation of Election Campaigns on Social Networks. Available online at: https://www.osce.org/Observing_elections_on_Social_Networks (accessed July 31, 2023).

OSCE (2022). Freedom of Media in Elections and Countering Disinformation. Available online at: https://www.osce.org/representative-on-freedom-of-media/516579 (accessed July 31, 2023).

Political Parties Elections and Referendums Act (2000). Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2000/41/contents (accessed July 31, 2023).

Pons, V. (2016). Has social science taken over electoral campaigns and should we regret it? French Polit. Cult. Soc. 34, 34–47. doi: 10.3167/fpcs.2016.340104

Representation of the People Act (1983). Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1983/2 (accessed July 31, 2023).

Robinson, S. (2018). Databases and doppelgängers: new articulations of power. Configurations 26, 411–440. doi: 10.1353/con.2018.0035

Römmele, A., and Gibson, R. (2020). Scientific and subversive: the two faces of the fourth era of political campaigning. New Media Soc. 22, 595–610. doi: 10.1177/1461444819893979

Rose, J. (2017). Brexit, trump, and post-truth politics. Public Integ. 19, 555–558. doi: 10.1080/10999922.2017.1285540

Rubinstein, I. (2014). Voter privacy in the age of big data. Wisconsin Law Rev. 861, 862–936. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2447956

Shiner, B. (2019). Big data, small law: how gaps in regulation are affecting political campaigning methods and the need for fundamental reform. Public Law 2, 362–379.

Susser, D., Roessler, B., and Nissenbaum, H. (2019). Online manipulation: hidden influences in a digital world, georgetown. Law. Technol. Rev. 4 1–46. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3306006

The Data Protection Act 2018. (2018). Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2018/12/contents/enacted (accessed July 31, 2023).

The UK Statistics Authority. (2020). The Role of the Statistics Authority in the 2019 General Election. Available online at: https://osr.statisticsauthority.gov.uk/blog/the-role-of-the-statistics-authority-in-the-2019-general-election/#:~:text=The%20UK%20Statistics%20Authority's%20role,for%20Statistics%20Regulation%20(OSR) (accessed July 31, 2023).

UK GDPR (2018). Available online at: https://uk-gdpr.org/ (accessed July 31, 2023).

Wood, A. K. (2020). Facilitating accountability for online political advertisements. Ohio State Technol. Law J. 16, 520–557. Available online at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/isjlpsoc16&div=26&g_sent=1&casa_token=tUIddISkJHUAAAAA:dB7_c3akWYWXN9WPH-G5RBwxs10NuIXFtXof3cuptijbgoHmBQI315DrJktD-4SxfjjRYys&collection=journals

Keywords: data, elections, data-driven campaigning, regulation, digital

Citation: Barclay A, Gibson R and Dommett K (2023) The regulatory ecosystem of data driven campaigning in the UK. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1146470. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1146470

Received: 17 January 2023; Accepted: 21 August 2023;

Published: 08 September 2023.

Edited by:

Felix Von Nostitz, Lille Catholic University, FranceReviewed by:

Isabelle Roth Borucki, University of Marburg, GermanyJordi Barrat, University of Rovira i Virgili, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Barclay, Gibson and Dommett. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrew Barclay, YS5iYXJjbGF5MUBzaGVmZmllbGQuYWMudWs=

Andrew Barclay

Andrew Barclay Rachel Gibson

Rachel Gibson Katherine Dommett1

Katherine Dommett1