- School of Governance, Law and Society, Tallinn University, Tallinn, Estonia

This article examines the role of ideations in the de-problematization process of the governance of “migration crises”. Ideations, for example, in the form of frames often simplify social reality and do not allow us to understand the nature of a problem policy-makers are dealing with. To show this, I use the example of the “European Migrant Crisis,” to illustrate that it is, in fact, a wicked problem. The “wicked problem” concept describes a complex and contingent problem and, in essence, a set of “un-owned” processes. It further dissolves local and global distinctions and forces to connect micro and macro processes at all times. In this article, I show that this “migration crisis” (and also many others) consists of much more than just a humanitarian or security crisis but is also constituted by geopolitical crises and crises of political institutions. A relational approach seems most pertinent to be able to grasp all these aspects and helps us to stop de-problematizing it and instead problematize it adequately. It also advocates for the circumvention of ideations as they are a main source for the de-problematization of wicked problems.

Introduction

This special issue explores the role ideations play in the governance of policy problems. Parsons (2007) views ideations as the underlying logic of politics shaped by beliefs, identity, practices, experiences, norms and morals. Ideations in forms of beliefs and ideological leanings have played a major role in governing (or better, the opposite) of global crises, like most recently the COVID-19 Crisis (see esp. Selg et al., 2022), for decades in the governance of the Climate Crisis (e.g., Selg et al., forthcoming, ch. 13; Klasche, 2021a,b), and the Migration Crisis of 2015. In this article, I will argue that it is, in particular, these ideations that de-problematize a wicked policy issue and stop us from dealing with the matter effectively1. I will do this by zooming in on the so-called “European Migrant Crisis” of 2015, which depending on who you will ask—meaning depending on your beliefs—can mean many different things. The lessons drawn from this will give insight into the governing and managing of migration at large—a problem that will not go away any time soon.

In 2020 the inflow of refugees into the European Union (EU) had slowed down compared to the heights of 2014/15. The number of asylum applications per quarter is down to below 50,000, especially drastic compared to over 400,000 quarterly in 2015 (Eurostat, 2020). Yet, the “Migrant Crisis”2 of 2015 has been firmly framed as a security threat—for Europeans (see, Klasche and Selg, 2020; Jäntti and Klasche, 2021). The dominating view on this matter is that migrants will impact the societal stability, safety, wealth and way of life of the Europeans. However, based on the dangerous and often lethal journeys, we should rather speak about a security threat to the lives of the people on the move. In a way, this is how the “crisis” was initially perceived. It was a humanitarian issue in which the refugees' circumstances on their flight and in their refuge required the biggest attention of policy-makers. The humanitarian issue has not gone away today. We still see inhumane hosting conditions in Moria, many deaths of refugees attempting to cross the Mediterranean sea and the terrible conditions refugees face now in camps outside of the EU in, for example, Turkey, Lybia, and Morocco (see, e.g., Jäntti and Klasche, 2021). This has added another dimension to this crisis: a legitimacy crisis of the EU, its institutions, and democracy at large due to their inability to address the humanitarian crisis in the first place. This establishes the European Migrant Crisis as a wicked problem; a problem that refuses to remain identical to itself and becomes, therefore, impossible to define and can be considered simultaneously

a humanitarian crisis based in the suffering of individuals who had abandoned their homes; a geopolitical conflict ranging across countries and continents; a security threat for both receiving and transit countries; a potentially heavy financial burden on already overtaxed states; and the breakdown of collaboration in the network of EU member states (Geuijen et al., 2016, p. 622).

To categorize the European Migrant Crisis (EMC) as a wicked problem has been well-established (Alisic and Letschert, 2016; Geuijen et al., 2016; Murray and Longo, 2018). After the inception of the concept by Rittel and Webber (1973), it has been frequently discussed, especially in public administration (e.g., Roberts, 2000; Head, 2008; Peters, 2017; Turnbull and Hoppe, 2018). Wicked problems are defined by their uncertainty, complexity and disagreement among stakeholders about problem definition and solution. There is “no single ‘root cause' of complexity, uncertainty and disagreement, and therefore no root cause of ‘wickedness”' (Head, 2008, p. 106); further complex systems are always mutating from one phase to the next and feature a high density of interactions (Wagenaar, 2007, p. 23, 25). This links the study and governance of wicked problems with processual relationalism (e.g., Jackson and Nexon, 1999, 2019; Qin, 2016; Selg, 2016a,b; Selg and Ventsel, 2020), a relational approach perspective that stresses “complexity and uncertainty come from viewing social problems or social processes as un-owned processes whose constituent elements cannot be considered separately from the changing relations they are embedded in and vice a versa” (see also Jackson and Nexon, 1999; Selg et al., 2022, p. 22–23). Here the focus is set on the un-owned nature of the processes that processual relationalism is interested in, which helps to upheave a relational definition of wicked problems according to which the level of complexity is increasing by the intensity of connection (relations) between units.

A relational approach is, however, not only useful in studying wicked problems but also in governing them. Selg et al. have most recently put forth a comprehensive introduction to a relational governance approach (forthcoming, see also Selg and Ventsel, 2020; Klasche, 2021a). In their book, they do not only point out the benefits of a relational approach in governing wicked problems but, very importantly for this article, note that the de-problematization of wicked problems often occurs when the wickedness is ignored, and politicians convert messy, unstructured problems into “well-structured” micro problems (ch. 4). This is often accompanied by re-framing the problem as “a way of selecting, organizing, interpreting, and making sense of a complex reality to provide guideposts for knowing, analyzing, persuading, and acting” (Rein and Schön, 1977, p. 146). What sounds great in theory exacerbates the problem in practice, as indicated by Head (2019) here:

complex issues requires special care, however, because such problems are often politically contentious and marked by “framing contests” that oversimplify the problems and recast them in more emotional and value-laden terms. This has become typical within the recent “post-truth” policy debates, fuelled by the manipulation of social media channels (p. 7).

In the case of migration crises, this means that the simplified framing as a security threat will not allow us to manage the crises properly, and we will just displace the problems temporarily and spatially. This is where ideations in many forms will stop us from adequately addressing wicked problems. Therefore, I will introduce a relational governance approach (“Failure Governance”) that focuses on the notions of problematization and de-problematization (esp. Selg et al., forthcoming) and squeeze out the notion that ideations, even though helpful in everyday policy-making, are very dangerous in dealing with wicked problems. The article proceeds as follows: First, the theoretical and conceptual notions of relationalism and wicked problems are laid out. Importantly, also a relational definition of wicked problems is provided. Secondly, arguments are provided for what makes the “European Migrant Crisis” a wicked problem. Finally, I will introduce a relational governance approach to wicked problems, and by applying it, I will show the negative impact ideations have on tackling these issues. The article turns now to laying out the main tenets of processual relationalism and providing a relational definition of wicked problems.

Processual relationalism and wicked problems

In the following section, the ontological conformity of processual relationalism and wicked problems will be pointed out. This more detailed argument is necessary to justify the linking of theory and concept and establish firmer grounds for a processual-relational analysis of the European Migrant Crisis. To do so, I will briefly construe the ontological commitments of processual relationalism and show their compatibility with the nature of wicked problems.

Processual relationalism

Processual relationalism is a camp (e.g., Elias, 1978; Emirbayer, 1997; Jackson and Nexon, 1999, 2019; Dépelteau, 2008, 2013, 2018a,b; Abbott, 2016; Qin, 2016; Selg, 2016a,b; Selg and Ventsel, 2020) within the “relational turn” in the Social Sciences that presumes the primacy of relations over the units/elements/actors (e.g., individuals, states, and structures) involved in these relations. Processual relationalism further assumes that relations are constitutive of these units/elements/actors and that relations are at the same time, unfolding, dynamic processes. It distinguishes itself from other relational theories like “critical realism” (e.g., Donati, 2011) or social network analysis (e.g., Crossley, 2010), especially in the latter aspect as these approaches took more realist or inter-actionalist stances. In simpler terms, relationalism is concerned with the dualism between substantialism and relationalism and aims to develop an approach that views the world via the prism of relations and not substances, as almost any other social theory does.3

Via the relational prism “the very terms or units involved in a transaction derive their meaning, significance, and identity from the (changing) functional roles they play within that transaction” (Emirbayer, 1997, p. 287). This means that units/elements/actors are never fixed and their constitution—and identity—is in a constant flux based on the relations they have with other units/elements/actors. Furthermore, this would also render an analysis with a focus on these units/elements/actors useless, and the attention should be placed on relations (or trans-actions according to the vocabulary of many processual relationalists; Emirbayer, 1997, p. 287). A helpful addition for the analytical focus has been introduced by Jackson and Nexon (1999) who stress the distinction between owned and un-owned processes. Based on this, when we consider processes triggered by actions of entities, they are “owned” and still keep us in the substantialist world. However, we should view processes as “un-owned,” independent from entities as they are the one's constituting entities. Based on this, for example, a change in Germany's migration policy is not a process that is triggered by Germany's political system but must be understood as a process that emanates in the interplay of the relations of entities. Therefore, the analysis requires us to consider the relations between all actors involved (Germany, other EU states, non-EU states, migrants, etc.). This distinction is especially helpful when we direct our attention to wicked problems.

Wicked problems

The wicked problem concept has been first coined by Rittel and Webber (1973) by categorizing certain urban planning issues as “wicked.” They considered 10 properties that make a problem wicked: (1) there is no definition; (2) there is no stopping-rule; (3) there are only “good-or bad” solutions; (4) there is no immediate solution; (5) every solution attempt counts significantly; (6) there is no exhaustive set of solutions; (7) every wicked problem is unique; (8) every wicked problem is the symptom of another problem; (9) the choice of explanation determines the resolution; (10) the planner has no right to be wrong (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 161–167). The classical text is a useful starting point to understand wicked problems, however, in the twenty-first century, many wicked problems are global (like the European Migrant Crisis), and it is useful to expand the definition further. Therefore, it is also necessary to consider that time is running out and that those seeking to end the problem are often the ones that cause it (Levin et al., 2012, p. 127–129). Additionally, it stretches across multiple value systems and involves multiple organizations; there are no boundaries between action and reaction, and it transcends spaces and knowledge systems (Noordegraaf et al., 2017, p. 392–393).

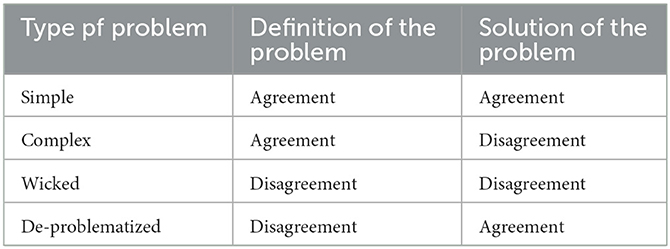

These points might lead us to a descriptive definition of the concept, but it still makes it hard to use for analytical purposes. For this, it has been proven useful (see, e.g., Selg et al., forthcoming; Selg and Ventsel, 2020) to distinguish two aspects of problems to categorize them as wicked, complex or simple problems: (a) the definition/formulation of the problem and (b) the solution to the problem. Based on this, we have simple problems where the problem definition and the solution can be clearly defined (e.g., issuing ID cards). Complex problems are problems that we can clearly define but have no clear solution or at least a very contested one (e.g., implementation of educational policies). In the case of a wicked problem, we have no clear definition or understanding of the solution. If we are considering the European Migrant Crisis, we have certainly no clear idea of how to solve it or -even who needs to involved. Even worse, we are also unable to define what constitutes the crisis. In the introduction, I hinted at the multiple dimensions of the crisis (and section four will make this point more explicit) that ranges from the humanitarian, to the political and societal. We cannot (at least anymore) say that the crisis is defined by immigration into the European Union but is not intrinsically linked with many other factors.

Finally, after understanding what problems are considered wicked, there is still a need to define a wicked problem in relational terms to successfully link the concept with processual relationalism. As argued above, wicked problems are constituted by several different aspects, suggesting that a piece-meal analysis of these aspects could be fruitful. However, the level of complexity and uncertainty is unparalleled and subsequently does not allow for a piece-meal treatment (see, e.g., Byrne, 1998; Cilliers, 1998). Instead, the level of complexity can be found in the relations between components. “Systems with relatively few parts can be complex because of the intensity of interaction between those parts” (Wagenaar, 2007, p. 23). This points us to the notion that wicked problems are not mere problems composed of several components. However, in processual-relational terms, their wickedness derives from “un-owned processes whose constituent elements cannot be considered separately from the changing relations they are embedded in and vice a versa” (Selg et al., forthcoming, p. 22–23). This leads to the conclusion that wicked problems are “processual all the way down” and it is imperative for grasping the problem at hand that any “process-reduction” (Elias, 1978; Emirbayer, 1997), i.e., piece-meal treatment, is avoided. This is further, where processual relationalism is identified as the chance to avoid exactly this and offer a fully processual analysis of wicked problems. The next section will display what this processual-relational agenda contains.

A processual-relational research agenda

Several methodological consequences are deriving from the ontological commitments brought forth by processual relationalism. A processual-relational approach

has to consider phenomena to be (1) relations among entities (2) that exist in practice; (3) and can be considered separately, but not as being separate. “Practice” in 2, of course, refers to social “process” which is our main concern. It is the second and the third conditions that count as sufficient for a processual-relational approach, while the first necessary condition is something that the approach shares with inter-actionalism (but not with self-actionalism). The third condition—let us refer to it as “separately, but not as being separate” condition—delivers the crux of relationalism home in a succinct manner, while the second one highlights the processual form of this relationalism (Selg et al., 2022, p. 27).

The quote above points out again the incapacity to use piece-meal approaches and a focus of analysis on actors/units/entities. Instead, the analytical focus needs to be placed on, unowned processes, as brought forth in the preceding paragraphs. Epistemologically, this means that we cannot learn about reality when we study units (states, individuals, and societies) but “dynamic, unfolding process, become (…) the primary unit of analysis rather than the constituent elements themselves” (Emirbayer, 1997, p. 287). In Emirbayer's quote, we find another important aspect of processual-relational methodology, which is the need for a constitutive inquiry. This type of inquiry or explanation has been directly linked with processual relationalism (Selg et al., forthcoming; Selg, 2019; Selg and Ventsel, 2020) and demarcates itself from causal inquiry. Causal inquiry is more or less the standard approach to conducting (social) science and establishes knowledge by uncovering causal mechanisms between X and Y (e.g., King et al., 1994; Gerring, 2005, 2012a,b). A causal argument would go more or less like this: “in saying that ‘X causes Y,' we assume three things: (1) that X and Y exist independent of each other, (2) that X precedes Y in time, and (3) that but for X, Y would not have occurred” (Wendt, 1998, p. 105, italics added; cf. Wendt, 1998, p. 79). Points (1) and (2) are not combinable with a processual-relational research agenda, as we cannot consider aspects of a phenomenon to be independent of each other (remember above's condition that entities can be considered “separately, but not as being separate”). It is also impossible to talk about timelines in constitutive explanations as constitution is not happening in separate moments but diachronically (see Selg et al., forthcoming based on Ylikoski, 2013). Point (3), on the other hand, is shared by both causal and constitutive explanation and leaves constitutive arguments to ask questions like “What makes Y Z?” or “Why is Y Z?” (Wendt, 1998, p. 113). This paper's specific case would lead us to ask the processual-relational research question, “what makes the European Migrant Crisis wicked?” Please note that this research question is quite different from its causal variations that would something along the lines of “how did the European Migrant Crisis become wicked?,” or “why did the European Migrant Crisis become wicked?” The latter two questions are inquiring about the process/mechanism/cause that made the EMC wicked, whereas the first question asks a more fundamental question about the crisis' being (or constitution). It is necessary to scrutinize the interdependence of relations that create the complexity and, therefore, the problem's wickedness to answer the question. To do this, I presume that it is sensible to deconstruct the crisis into several lower-level crises and display the issue's wickedness via their interdependence and constitutive relationship. It is important not to forget our necessary dictum and keep in mind that we can view the crises as being “separately, but not as being separate” (Elias, 1978, p. 85). Even though I suggest to divide the crisis into several ones, we have to be careful to not treat it in a “piece-meal manner” which I have warned against above, but at all time keep the constitutive nature of the phenomenon in mind. Inline to avoid further criticism, it is also important to realize that when looking at them from close detail,

the processual and continuously changing configurations of elements through which the meaning of elements themselves are constituted and reconstituted is lost. But if we are to conceptualize the crisis as a wicked problem, then we have to imagine this scheme in a moving diachronic fashion rather than only as a synchronic snapshot (Selg et al., 2022, p. 33).

What makes the “European Migrant Crisis” wicked?

A processual-relationalist research project would ask a constitutive research question. In this case, the question would be: What makes the European Migrant Crisis wicked? Remember, wicked problems are often symptoms of other problems, and that attempted solutions can never be right or wrong but only good or bad. On top of that, we know that solution attempts will have consequences that may not be reversible. We can see all those aspects here. Various attempts at solution created other crises that might have even more drastic impact on the European population and the decision-makers themselves. In other words, “[m]any wicked problems seem to lurch from crisis to crisis” (Head, 2019, p. 189). To show this, I will point out the different crises of which the “European Migrant Crisis” is comprised of and how they constitute each other. More specifically, I will look at the humanitarian, the political/legitimacy, and geopolitical crises (certainly even more “parts” could have been considered), which interdependently ground the un-owned process that we call European Migrant Crisis.4 What follows is not a full-fledged case study but an illustration of the prospect of a processual-relationalal approach. Hence, it draws heavily on various other research on the crisis.

Humanitarian crisis

The humanitarian crisis is the most obvious to spot and forms the starting point for the crisis on European soil. In 2015 around 28 million people were displaced due to conflict, violence and disaster, joining the 244 million international migrants already moving throughout the globe (Kaundert and Masys, 2018, p. 73). According to the UNHCR, this is the “highest level ever recorded” (2015). Within this international development, the EU (and its historic territory) faced the most massive and most complex surge in migration since the Second World War. Between January 2015 and February 2016 alone, more than 1.1 million people fled from conflict and poverty and landed in the EU (Kaundert and Masys, 2018, p. 73). Humanitarian challenges are always the main reason for migration (Kaundert and Masys, 2018, p. 79). In fact, according to the Humanitarian Practice Network, “the flight to European shores reflect (…) not only the pull of greater long-term security in Europe but also the failure of the international humanitarian community to meet basic needs in other places” (DeLargy, 2016, p. 5).

The most recent rise in the number of refugees in Europe is mostly related to the Syrian Civil War that started in 2011. However, this is not the sole reason, and it is a combination of political instability, social unrest, violence and socio-economic reasons in the Middle East, the Maghreb Region, and Sub-Saharan Africa (Kaundert and Masys, 2018, p. 74). Besides that, the climate crisis had already an impact on migrants in other regions (like South-East Asia), and it only appears to be a matter of time that it will also affect the movement toward Europe. This, in turn, has a potential to emanate into a huge Human Security risk for the people staying put in their homeland and for the ones on the move that more often than not have to travel through regions of distress and face new security risks unique for a displaced person such as survival, coordination, transportation, communication and other physical resources such as food, shelter, medicine, and clothing (Thurnay et al., 2017, p. 240).

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2015) estimates that over one million people have reached Europe via the Mediterranean, and over 3,700 of them went missing alone in 2015. Apart from the apparent disaster of thousands of humans drowning in the Mediterranean Sea the failure of establishing adequate policies has seen countries violently blocking their passages, migrants remaining in camps with appalling conditions at Europe's borders, the displacement of thousands of people that are now known to be “missing,” the rise of human smuggling with all its criminal by-products, and a presumed situation in which around one million people will remain un-authorized in Europe (Phillips, 2018; p. 63–64). The EU has attempted to outsource this issue by working with its neighbors—most notably Turkey but also Morocco and Lybia—to stop refugees from even approaching Europe's borders (Jäntti and Klasche, 2021). In fact, this might be Europe's biggest challenge of the twenty-first century confronting the continent with long-lasting implications for humanitarian practice, regional stability and international public opinion (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2015).

The humanitarian crisis is embedded in a complex system which makes successful intervention especially problematic (Selg and Ventsel, 2020, p. 262). Approaching a problem in such a complex system with a linear mindset can lead to interventions that result in unintended consequences (Kaundert and Masys, 2018, p. 81) and “the failure to understand or (…) acknowledge the non-linear and highly complex nature of global linkages on every level of governance leads to growing weakness. It can paralyze decision-making” (Goldin and Mariathasan, 2014, p. 3). This paralysis in decision-making and governance constitutes, among other things, the political crisis the EU and some of the national governments of its member states face (Selg and Ventsel, 2020, p. 262).

Political crisis

In the following, three mutually constitutive processes are identified as the political crisis of the EU (Selg and Ventsel, 2020, p. 262). We will learn that these are intimately intertwined with the humanitarian crisis as political actions and inactions will impact human suffering. This is rather obvious, however, the changing situation on the humanitarian front then requires engagement on the political.

The first process is the crisis of democracy, displayed in the demise of general democratic tendencies in Europe, allowing for anti-democratic and anti-establishment parties to gain confidence (Selg and Ventsel, 2020, p. 262). The other crisis is one of legitimacy, leading to the growing mistrust in the EU institutions, the idea of the EU itself or even the nation-state (Selg and Ventsel, 2020, p. 262). This is expressed by voters in national and European elections turning to anti-establishment and anti-EU parties, but also by national governments and politicians who actively seek more independence from the EU. It is further expressed in criticizing existing neoliberal global governance structures (such as the Bretton Woods System or the UN). Thirdly, a crisis of values is noticeable, when the EU leaves behind its humanitarianism and stresses security concerns over solidarity which used to be one of the main pillars of its self-conception.

The crisis of democracy is based on the appeal of far-right, anti-establishment and anti-constitutional parties that were able to celebrate great successes in the 2010's. This crisis is without a doubt exacerbated by the increased migration in 2014/15, where these parties saw the opportunity to intensify their anti-immigration rhetoric and phrased it as an undeniable security threat to European societies (see, e.g., Klasche and Selg, 2020). However, this crisis existed before the intensified migration in 2014 and already had a strong hold on societies beforehand. Therefore, I would argue that it impacted the humanitarian crisis from the start, where we saw, for example, the Hungarian Fidesz regime come down with utmost brutality on the refugees (Bender, 2020). This type of border control, something Europeans had not seen since the 1990's, will also play a role in the next section on the geopolitical crisis.

The legitimacy crisis was created by the EU's responses to the humanitarian crisis, which in return led to contestations by governments, opposition parties and citizens (Murray and Longo, 2018, p. 571). The issues relating to the humanitarian crisis' governing and the differences in practices that various actors are promoting (Murray and Longo, 2018, p. 571). The crises' constitutive nature becomes apparent as the political crisis begins to be inextricably linked with the humanitarian crisis, which is a part of its very identity (Selg and Ventsel, 2020, p. 263). Here each response will alter the other crises, which then trigger the need for new responses that do not only consider the humanitarian crisis but also the legitimacy and democracy crises. The “politicization” of the (initially) administrative issue of handling the incoming migrants—an issue that experts should handle has been made a “people's” issue, by right-wing populist parties all over Europe (Selg and Ventsel, 2020, p. 263). The abating of incoming migrants does not mean the end of the EMC, as it simply changed its identity and can no longer be defined in terms of a humanitarian issue.

It has become a wicked problem that is constantly fluctuating between different crises, the political being one. Responses to one crisis—especially attempts to “solve” it in isolation—will inevitably affect the others, since, in case of constitutive relations, the crises are interdependent and cannot be considered as being separate from one another (Selg and Ventsel, 2020, p. 263).

Some of these solution-attempts that ultimately changed the crisis are ranging from welcoming refugees to Europe to the strict closing of borders. Solutions have also affected EU members very differently. The frontier states of the EU (Italy, Greece, Spain, and Malta) must carry a “disproportionate burden” (Murray and Longo, 2018, p. 574) which has never been addressed in any asylum policy initiative. Some might argue that the whole problem boils down to the lack of common European asylum policy that would ensure the burden is carried by all member states equally. When the European Commission's decisions to relocate 120,000 refugees in 2015 was objected to and ignored by Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic (European Commission, 2017) it indicated for many an apparent lack of resonance of the EU's values (Murray and Longo, 2018, p. 575). This “rebellion by member states (…) is unprecedented in its breadth and depth, given that i[t] constitutes not only contestation but direct opposition to the EU's authority and legal framework” (Murray and Longo, 2018, p. 575). It clearly shows the level of distrust of national governments in the EU's ability to handle the crisis adequately. Subsequently, the migration crisis represents one of the most notable and consequential episodes of political failure in the history of European cooperation, which many worry, retains the capacity to challenge the core of the European project (Phillips, 2018, p. 62).

The crisis has also shed a bad light on the international community and global governance structures that cannot seem to address violence, conflicts and human rights violations in the sending countries (Kaundert and Masys, 2018, p. 80). There is no clear plan or framework for the solution of many transboundary problems that require the cooperation of international actors. Even if there would be an end to the Syrian Civil War in sight, there does not seem to be any guarantee for this country's forthcoming stability. At least this would be reasonable to presume, given Somalia or Afghanistan's experience that even despite years of international intervention remain highly unstable with chronic poverty, inequality, weak governance, and lack of solutions for environmental changes (Metcalfe-Hough, 2015, p. 3). Therefore, the legitimacy crisis could be seen to move further on from the European governments and the European Union to international organizations (e.g., the UN and its sub-bodies) founded on Western values and are not contributing to solving the global problems they were aimed at doing.

Stretching this argument even further, we can find the crisis challenging the Westphalian state system's legitimacy by maneuvering the nation-state's foundation into a crisis. At least in the Western world, the nation-state is the most fundamental building block of the system. The nation and the concept of nationhood find many interpretations, have always been evolving and at the same time challenged and contested (Jacob and Luedke, 2018, vi). The twenty-first century presented already many challenges to the nation-state, with its growing globalization forces that threaten the sovereignty and perceived ability to control its destiny (Jacob and Luedke, 2018, vii). Due to the interconnectivity with international and supranational institutions, the reactions of national governments to these forces have been often insufficient. This is particularly visible in the case in the European Union that for a moment placed much less emphasis on borders and bounding nationstates but finds itself now scrambling how to proceed. This is constitutively related to the humanitarian crisis since adapting and controlling human migration will be one of the most crucial tests for the nation-state (Jacob and Luedke, 2018, xiii). Simultaneously, the lack of supranational cooperation and even outright conflict between nation-states in solving the humanitarian crisis defines the latter, again, as not merely administrative, but a political crisis.

The humanitarian crisis constitutes a political crisis, but also the opposite is true: the political crisis frames the extent and nature of the humanitarian crisis. Migration waves will not stop in the future as living-conditions in many parts of the world deteriorate, and migration will be the only answer to this (Castelli, 2018). “The political crisis is not only a result of the humanitarian crisis. They are intrinsically intertwined. They cannot be seen independent from each other, but as mutually constituting each other” (Selg and Ventsel, 2020, p. 264).

Geopolitical crisis

The political/legitimacy crisis points to the existence of another crisis that is raging in relative inconspicuousness in Europe. The political crisis which is highly interconnected with the humanitiarian crisis also finds itself to be exploited by Russia—which unsurprisingly to a knowledgeable observer intervenes in the political discourse to seed chaos and divide in European societies. This is where the European Migrant Crisis finds itself firmly expressed as a geo-political crisis—a crisis in which another power attempts to weaken the EU. However, also this crisis finds its beginning before 2014. The earliest realization of the geopolitical crisis started in 2008, with Russia re-claiming their imperial ambitions via the Georgian-Russian war and later with the annexation of Crimea in 2014 (Wivel and Wæver, 2018, p. 318). The new security environment emanating out of this also affected the geo-economic constellations of the EU and its Eastern neighbors (Youngs, 2017). The geopolitical power of the EU is expressed in its unity, which has suffered during the last 3 years (Selg and Ventsel, 2020, p. 264). The Russian Federation favors this situation and feasts on the instability of its competition. Seeking instability is part of the “hybrid warfare” playbook that is less concerned with traditional military strategies but with the ability to default to “plausible deniability”. The tactics include the use of propaganda to initiate insurgencies and divide societies which can be easily deployed in the context of polarizing migration policies. For example, Germany offers an ideal playing field for the Kremlin's tactics that have proven useful during the last German election (Aaltola, 2017) and increased the divide between right and left. Naturally, this is also visible today when the German public and political sphere are split over supporting Ukraine to fight off the Russian invasion. This divide is reached through the manipulation of the political discourse that decides on the blame for the situation (political-economic structures, the displaced persons themselves), demarcates the “deserving” migrant from the “undeserving” refugee and generally activates the fear of cultural, religious, and ethnic differences (Holmes and Castañeda, 2016, p. 12).

More precisely, Russia attempts to capitalize on the refugee crisis to re-enter Europe after its exclusion in the aftermath of the invasion of Crimea by (1) casting Europe in a more conservative light in contrast to the self-proclaimed liberal cosmopolitan self-understanding of the Europeans and (2) by “othering today's Orientalized Europe” (Braghiroli and Makarychev, 2017, p. 823). In my terms, this intervention exacerbated the crisis of democracy above as it supported many Eurosceptic parties, which then were able to intensify the anti-immigrant and anti-establishment narratives. It also heightens the humanitarian crises as the effective narratives of othering of migrants made more violent and inhume handling more acceptable.

As stated above, none of these crises is actually over—or dealt with—and so also the geopolitical aspects still loom, for example on more recent events at the Eastern border of the EU. In the Winter of 2021, the “EU-Belarus Border Crisis” saw the Putin regime openly use refugees to pressure the EU by putting it in the strange position of choosing between its humanitarian values and security ideations. Similar strategies have been used by Turkey's Erdogan, where he used the opening or closing of borders are bargaining chips to gain political capital. Finally, it also seems to be one of the main strategies of the Kremlin in its War in Ukraine to displace as many Ukrainians as possible to put political pressure on European leaders. These aspects also point neatly to the fact that the “European Migrant Crisis” was by no means a single and confined event but should be rather understood as part of a process of migration toward Europe and political competition of manifold actors. We also must stress that the crisis is not over or managed and merely changes its face. This points firmly to the conclusion that the processes that culminate into what we refer to as the “European Migrant Crisis” is a wicked problem.

All those crises are interdependent and therefore, mutually constitutive. Thus, for instance, mismanagement of the humanitarian crisis ignites the political crisis and is used as fuel for the meddling campaigns in the geopolitical crisis. The political crisis leads to mismanagement of the humanitarian crisis refueling, in turn, the political crisis and it also provides the breeding ground for the geopolitical crisis. The same applies to the geopolitical crisis that stirs up the anti-refugee sentiment and affects the humanitarian and political crises by doing so. Additionally, the sheer existence of Russian influence on the continent intensifies the political crisis... All three crises are in a constitutive relationship and it is not possible to view them as independent entities. They can be viewed “separately, but not as being separate” (Selg and Ventsel, 2020, p. 265–266).

Constitution of the crises

Even though the crises seem somewhat of chronological order, with the humanitarian crisis preceding the others, it is important to recall that they are independent of each other and in a constitutive relationship, at least as soon as they all exist. Causality might be present at the very start. Still, as soon as we can describe the EMC as a political crisis, humanitarian and political crises, they are in a constitutive relationship. The crises “can be viewed separately, but not as being separate. This makes the (…) [c]risis an un-owned process, a ‘doing,' that is not attributable to a particular ‘doer.' However, it becoming an un-owned process took time” (Selg et al., 2022, p. 39). The illustrative case above showed, according to constitutive inquiry, “what makes Y a Y in the first place and how it turns into something else or remains the same in time” (Selg et al., 2022, p. 39). The EMC started as a humanitarian crisis but quickly transformed into something else and is now a humanitarian crisis, a political crisis, a geopolitical crisis and potentially more that was not covered in the brief sketch. Also note, therefore, it would not be possible for the humanitarian crisis to have the shape it has right now without the relationship with the political and geopolitical crises. The same applies to the political crisis, as well as the geopolitical crisis. The mutually constitutive relationships between the various crises are here the key to the wickedness—the higher the intensity of interconnections, the higher the complexity, the higher the wickedness—and therefore answers the processual-relational research question “What makes the European Migrant Crisis wicked?” successfully.

Governing migration crises by problematization and the danger of ideations

After having laid out what a wicked problem (and a relational definition of one) is, and having shown that the “European Migrant Crisis” must be viewed as one, it is time to turn our attention to the main intervention of this article—the role of ideations of the management of crises of this kind. Beforehand, I want to remind the reader of the analytical definition of a wicked problem based on the agreement and disagreement of stakeholders regarding the definition of the problem and the solution (see Selg et al., 2022, forthcoming). Above I classified all problems of governance into three categories: simple, complex and wicked. This is based on two aspects: (a) the agreement on the definition/formulation of the problem and (b) the solution to the problem. When there is agreement on both, we ought to talk about simple problems; when there is agreement on the definition but not on the solution, we refer to complex problems; and when there is no disagreement about either, we should speak of wicked problems. However, logically there is also a fourth option in which we find a disagreement on the problem definition but an agreement on its solution. In this case, the problem is being de-problematized as its wickedness is ignored. The name is inspired by its parallels to “depoliticization” (Hay, 2007; Fawcett et al., 2017). The problem definition criteria are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Types of problems based on agreement on the definition and solution of the problem (see Klasche, 2021a; Selg et al., 2022).

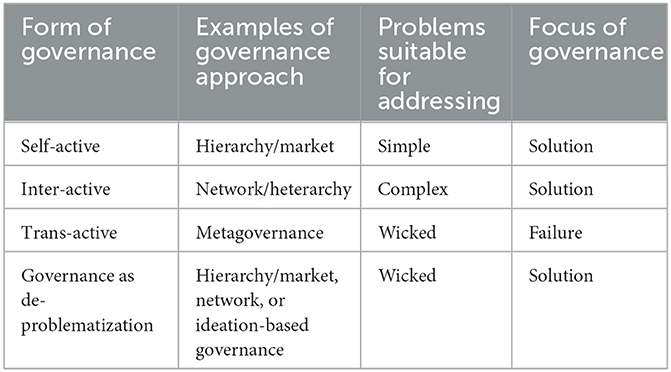

In previous work, it has been theorized that de-problematization occurs when there is a mismatch of governance approaches to a problem, i.e., approach a wicked problem like a simple or complex problem. This is often the first reaction when approaching the governance of a wicked problem. We tend to break it down into multiple smaller elements that are “easier” to manage or could even be solved independently. However, based on the nature of the problem, this cannot be successful (see Selg et al., forthcoming; Klasche, 2021a). In that scenario, we also notice a temporal displacement in the sense that urgent problems are not receiving the instant attention that they should. In this article, I want to emphasize that one of the core reasons, next to ignorance, is the ideological tainting of a problem—or the impact of ideations—that does not allow the problem to be managed properly. But before looking into this closer, it seems necessary to briefly address what I understand when I speak about governance approaches.

At the beginning of this endeavor stands the question of whether policy problems can be solved at all. Interpretivist/Constructivist scholars agree that “solving” a (societal) problem is a problematic action, and we should rather talk about governing it (e.g., Rein and White, 1977). Rein and White (1977), for example, dismiss the “problem-solving image” of policy-making that “rest[s] on the conviction that policy expresses a theory of action that includes: (1) a definition of the problem; (2) a set of possible courses of action; and (3) a goal or goals one seeks to achieve” (p. 250). Keeping this in mind, I believe that it is certainly possible to find solutions for simple and complex problems. The proven strategies have been traditional market/hierarchy-based self-active governance and, more recently prevalent, network/heterarchy-based inter-active governance approaches (Klasche, 2021a, p. 47–50). However, when applied to wicked problems, these approaches fail to address the problem due to various constraints. It starts with the fact that they are both substantialist types of governance where we need a relational form capable of considering the contingency and uncertainty of the social. The other problem is their focus on wanting to solve problems. A wicked problem cannot be solved and, at best, managed and governed over time which is why these approaches do not fit. This is why Selg and Ventsel (2020), (Selg et al., 2022), and Selg et al. (forthcoming) landed on the term “Failure Governance,” a trans-active—and deeply relational—governance approach that focuses on the failure of governing wicked problems. This approach borrows from Jessop's concept of metagovernance that requests, among many things, that policy-makers combine

the “optimism of the will” with “pessimism of the intelligence.” [Most importantly,] ironist accepts incompleteness and failure as essential features of social life but acts as if completeness and success were possible. She must simplify a complex, contradictory, and changing reality in order to be able to act—knowing full well that any such simplification is also a distortion of reality and, what is worse, that such distortions can sometimes generate failure even as they are also a precondition of relatively successful intervention to manage complex interdependence (Jessop, 2011, p. 119).

The different governance approaches and their usefulness in governing different problems is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Forms of governance and their focus of governance matched with suitable problems for addressing [see also (Selg et al., forthcoming; Klasche, 2021a)].

Based on this, it becomes apparent that substantialist approaches (self-active and inter-active) to govern wicked problems are bound to fail. This becomes even more telling when one considers the de-problematization of problems. Borrowing Hay's (2007) ideas on the depoliticization of issues, we found that many wicked problems are de-problematized in a similar fashion. And this is precisely where ideations come in.

Why are ideations now so problematic here? If we consider ideations in the form of frames, for example, it tries to press wicked problems in a “wrong” problem category. Let us take, for instance, the example of the securitization of the European Migrant Crisis of 2015. In this case, migration is solely viewed as a security threat—something that we certainly could observe in most European countries (see Jäntti and Klasche, 2021)—we will find that the problem is misrepresented as a simple problem, which could be solved by simply closing the borders. This is something that many alt-right parties suggest. However, this disregards the following worsening of the humanitarian crisis, i.e., people drowning in the Mediterranean, freezing to death at the Eastern border, or living hopeless lives in camps on Greek islands. It also does not get away with the polarization of the population that fights over a focus on either humanitarian or security values—something that we can observe in the political and geopolitical crises laid out above. This continuous polarization leads to threats to the social order and the survival of democratic institutions and values which then deepens the suffering of refugees. These acts of self-active governance to migration do often not even address the one aspect of the problem they are aimed at. For example, if security concerns mostly find expression in the fear of increasing numbers of migrants entering the country, straightforward policies, such as closing borders, are not effective. An example would be Donald Trump's plan to build a wall at the Mexican-US border to counter the wicked issue of mass migration that, based on his assumption, would stop the inflow of migrants. However, it is almost inevitable that the inflow will not stop but only be re-routed (Garrett, 2018, p. 203) based on the evidence that the Mexican-US border is already highly fortified and militarized and yet has not shown to play a major role.

Similarly, suppose we view the “migration crisis” only via the humanitarian frame—one that stresses Europe's liberal values and its self-understanding as a positive norm-creator (see again, Klasche and Selg, 2020; Jäntti and Klasche, 2021)—meaning we center on the humanitarian catastrophe and subsequently make sure that Europe takes in as many refugees as possible, intensifies rescue missions in the Mediterranean, and focuses on the closing of refugee camps and on the integration in the host society. In that case, we run into the danger of ignoring security and geopolitical aspects (i.e., societal security concerns, terrorism but also destabilization of sending and transit societies) and the work political institutions will have to do in light of this development. Personally, of course, this appears to be the better option in light of bad options, as it saves as many lives as possible. Nevertheless, the point remains that ideational/frame-based takes on wicked problems simplify them—de-problematize them—to such a degree that we lose sight of many of its characteristics and drivers which ultimately disallow us to govern them adequately.

Ideations here become something like ideologies or worldviews. They are used to solve problems “by displacing them through readymade ideological or ritual responses that are presented as universal solutions to whatever societal problems rather than by attempting to address them” (Selg et al., 2022). Furthermore, ideations are crucial “where each competing group attempts to define or ‘frame' the problem in a way that favors certain coalition building” (see also Fischer, 2003, ch. 5; Selg et al., 2022). Ideations are, therefore, very impactful in agenda-setting and coalition-building in day-to-day politics. However, when faced with wicked problems, this creates great problems as here both the problem definition and the solution are “heavily loaded with interpretive baggage, political story-lines and hegemonic discourses, making agreement over them utterly impossible” (Selg et al., 2022). Examples of this can be especially found in the political discourse in and around climate change. Statements such as: “‘there is nothing we can do' or ‘we must take immediate action”' (Fischer, 2003, p. 86) are prevalent. Climate change discourse is also ripe with macro-level, hegemonic discourses (Fischer, 2003, p. 89) that position the problem in contrast with other problems, e.g., “the growth of the economy has to come first,” “the transition to other energy sources will be too costly.” In our language, ideations in the form of framings or certain ideologies will de-problematize a wicked problem and, more importantly, will not allow us to adequately problematize it as the frame or ideology brings clear solutions to the issues. Instead, we should be moving to the ideation of the “problematization ethos” a constant readiness to problematize readymade policy responses “so that the governance mix can be modified … flexib[ly] in the face of failure” (Fischer, 2003, p. 118).

Conclusion

This paper has stressed that the “European Migrant Crisis” must be considered a wicked problem based on its complexity. We should not view it solely as a problem of migrants entering the EU but rather as an irreducible un-owned process within local and global societies with multiple interdependent relations that constitute it a problem in the first place. It is a global phenomenon consisting of multiple crises emanating from many locations worldwide that cannot be “solved” by stopping migrants from entering the EU. We need to understand that problems of this kind—wicked problems—can at best be managed and require constant problematization that acknowledges its changing nature. Frames and other ideations, however, create a reality where reality is ordered and straight-forward and where ideologically tainted solution attempts to wicked problems are the norm. In this reality the problem is reduced to mere parts that depending on which ideation is at work can be solved with simple policy interventions. Out of the sudden, wicked problems appear tame and straightforward like simple technical problems that can be managed with the “old toolbox” of everyday politics. Policy-makers are seduced to approach it with their regular governance tools, giving the impression to the public and the voters that they can “handle” these problems and solve them at once. Of course, this is something we have come to expect of our policy-makers. However, when dealing with wicked problems, this cannot be the desired option as it simply will not work. One answer is the application of failure governance. A mode of governance that understands

that wicked problems are un-owned processes and that the process-relational approach requires, among other things, constant awareness of the fact that the process involved is not in principle reducible to elements and their action as the latter are constituted and reconstituted within this process. Furthermore, in that sense, failure is bound to be central in any attempt to govern this process (Selg et al., forthcoming, ch. 4).

This governance approach does not try to engage with wicked problems using proven policy tools but engages them more with an ethos-based approach in which policies are in a need to constantly change to match with the contingency and relationality of the social. Therefore, no clear guidelines to the management of wicked problems can be given except for the need to attempt to acknowledge their complexity at all times (problematize them) and the need to do away with ideations that usually attempt the opposite—reduce the world to a place that can easily be ordered and understood (de-problematize it). That being said we find some guidelines on what this ethos ought to be grounded on in discussions on metagovernance: (1) Requisite variety; (2) Reflexive orientation; (3) Self-reflexive irony (e.g., Jessop, 2011). Klasche (2021b, p. 4) has summarized these notions as follows:

Requisite variety is a “deliberate cultivation of a flexible repertoire of responses” (Jessop, 2011, p. 117), so in case of governance failure, the strategies can swiftly be modified. Reflexive orientation addresses the preparation for failure. It states that “a reflexive observer … cannot fully understand what she is observing and must, therefore, make contingency plans for unexpected events” (Jessop, 2011, p. 117). Lastly, self-reflexive irony is required for “tackling often daunting problems of governance in the face of complex, reciprocal interdependence in a turbulent environment” (Jessop, 2011, p. 118), and it equips the policy-maker with the ability to accept “incompleteness and failure as essential features of social life but [still] acts as if completeness and success were possible” (Jessop, 2011, p. 119).

After all, I am not suggesting getting rid of ideations but rather exchanging them with the attempt to conceive of the world in relations, which helps us embrace its contingency and interrelatedness. This approach runs counter to what ideations usually do, order the world and simplify it. Instead, it increases the world's complexity and allows us to see to the bottom of problems we must address. Only equipped with this ideation can we manage wicked problems such as the “European Migrant Crisis.”

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement no. 857366, project MIRNet—twinning for excellence in migration and integration research and networking.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer OL declared a shared affiliation with the author BK to the handling editor at the time of review.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Parts of this article are based on or taken from my doctoral dissertation Dealing with Global Crises. A Processual-Relational Approach to Studying and Governing Wicked Problems. Published 2021 by Tallinn University.

2. ^I am placing the term in quotation marks to acknowledge that the term crisis is difficult here unless it is centered on the people losing their lives while attempting to cross European borders.

3. ^For a more detailed description what differentiates substantialist approaches of social action (self-action and inter-action) from relational approaches (trans-action) see e.g., Dewey and Bentley ([1949] 1989), Emirbayer (1997), Selg (2016b), Selg and Ventsel (2020), Selg et al. (2022).

4. ^The delineation of the EMC into these three particular crises is borrowed from Selg and Ventsel (2020, ch. 8).

References

Aaltola, M. (2017). Democracy's Eleventh Hour. Safeguarding Democratic Elections Against Cyber-Enabled Autocratic Meddling. Fiia Briefing Paper. Helsinki: Fiia, 226.

Abbott, A. (2016). Processual Sociology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226336763.001.0001

Alisic, E., and Letschert, R. M. (2016). Fresh eyes on the European refugee crisis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 7, 31847. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v7.31847

Bender, F. (2020). “Abolishing asylum and violating human rights of refugees. Why is it tolerated? The case of Hungary in the EU,” in Europe and the Refugee Response. A Crisis of Values?, eds E. M. Gozdziak, I. Main, and B. Suter (London: Routledge), 59–73.

Braghiroli, S., and Makarychev, A. (2017). Redefining Europe: Russia and the 2015 refugee crisis. Geopolitics 23, 823–848. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2017.1389721

Castelli, F. (2018). Drivers of migration: Why do people move? J. Travel Med. 25, 1–7. doi: 10.1093/jtm/tay040

Cilliers, P. (1998). Complexity and Postmodernism. Understanding Complex Systems. London: Routledge.

DeLargy, P. (2016). Refugees and vulnerable migrants in Europe. Special feature. Human. Exchange 67, 5–7.

Dépelteau, F. (2008). Relational thinking: A critique of co-deterministic theories of structure and agency. Sociol. Theory 26, 51–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9558.2008.00318.x

Dépelteau, F. (2013). “What is the direction of the ‘relational turn'?,” in Conceptualizing Relational Sociology: Ontological and Theoreticalissues, eds C. Powell and F. Dépelteau (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 163–185.

Dépelteau, F. (2018a). The Palgrave Handbook of Relational Sociology. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-66005-9

Dépelteau, F. (2018b). “From the concept of ‘trans-action' to a process-relational sociology,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Relational Sociology (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 499–519. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-66005-9_25

Dewey J. Bentley A. ([1949] 1989). “Knowing the known,” in John Dewey's Collected Works: The Later Works 1925-1953, Vol. 16, ed J. A. Boydston (Chicago, IL: Southern Illinois University Press), 1–293.

Emirbayer, M. (1997). Manifesto for a relational sociology. Am. J. Sociol. 103, 281–317. doi: 10.1086/231209

European Commission (2017). European Agenda on Migration: Commission Calls Onall Parties to Sustain Progress and Make Further Efforts. Press Release, Strasbourg. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_17_1587 (accessed January 15, 2021).

Eurostat (2020). Asylum Quarterly Reports. Eurostat. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/ (accessed January 15, 2021).

Fawcett, P., Flinders, M., Hay, C., and Wood, M. (2017). “Anti-politics, depoliticization, and governance,” in Anti-Politics, Depoliticization, and Governance (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 3–37. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198748977.003.0001

Fischer, F. (2003). Reframing Public Policy: Discursive Politics and Deliberative Practices. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/019924264X.001.0001

Garrett, T. (2018). Where there's a wall there's a way: The end (?) of democratic discourse regarding immigration and border security policy. Maryland J. Int. Law 33, 183–204.

Gerring, J. (2005). Causation: A unified framework for the social sciences. J. Theoret. Polit. 17, 163–198. doi: 10.1177/0951629805050859

Gerring, J. (2012a). Mere description. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 42, 721–746. doi: 10.1017/S0007123412000130

Gerring, J. (2012b). Social Science Methodology: A Unified Framework. Cambridge, CA: Cambridge University Press.

Geuijen, K., Moore, M., Cederquist, A., Ronning, R., and Van Twist, M. (2016). Creating public value in global wicked problems. Publ. Manag. Rev. 19, 621–639. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2016.1192163

Goldin, I., and Mariathasan, M. (2014). The Butterfly Defect: How Globalization Creates Systemic Risks, and What to Do About It. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Head, B. W. (2019). Forty years of wicked problems literature: Forging closer links to policy studies. Policy Soc. 38, 180–197. doi: 10.1080/14494035.2018.1488797

Holmes, S. M., and Castañeda, H. (2016). Representing the “European refugee crisis” in Germany and beyond: Deservingness and difference, life and death. Am. Ethnolog. 43, 12–24. doi: 10.1111/amet.12259

Jackson, P. T., and Nexon, D. H. (1999). Relations before states: Substance, process and the studyof world politics. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 5, 291–332. doi: 10.1177/1354066199005003002

Jackson, P. T., and Nexon, D. H. (2019). Reclaiming the social: Relationalism in anglophone international relations. Cambridge Rev. Int. Affairs 32, 582–600. doi: 10.1080/09557571.2019.1567460

Jacob, F., and Luedke, A. (2018). Migration and the Crisis of the Modern Nation-State? Wilmington, DE: Vernon Press.

Jäntti, J., and Klasche, B. (2021). ‘Losing leverage' in the neighborhood. A cognitive frames analysis of the European Union's Migration Policy. Int. Stud. 58, 302–323. doi: 10.1177/00208817211030643

Jessop, B. (2011). “Metagovernance,” in The SAGE Handbook of Governance, ed M. Bevir (London: Sage), 106-123.

Kaundert, M., and Masys, A. (2018). “Mass migration, humanitarian assistance and crisis management: Embracing social innovation and organizational learning,” in Security by Design. Innovative Perspectives on Complex Problems, ed A. J. Masys (Berlin: Springer), 73–91. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-78021-4_5

King, G., Keohane, R. O., and Verba, S. (1994). Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference Inqualitative Research. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Klasche, B. (2021a). Dealing with Global Crises. A Processual-Relational Approach to Studying and Governing Wicked Problems. (Dissertations on Social Sciences), Tallinn University, Tallinn, Estonia, 146.

Klasche, B. (2021b). After COVID-19: What can we learn about wicked problem governance? Soc. Sci. Human. Open 4, 100173. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100173

Klasche, B., and Selg, P. (2020). A pragmatist defence of rationalism: Towards a cognitive frames-based methodology in international relations. Int. Relat. 34, 544–564. doi: 10.1177/0047117820912519

Levin, K., Cashore, B., Berenstein, S., and Auld, G. (2012). Overcoming the tragedy of superwicked problems: Constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Pol. Sci. 45, 123–152. doi: 10.1007/s11077-012-9151-0

Metcalfe-Hough, V. (2015). The Migration Crisis? Facts, Challenges and Possible Solutions. Overseas Development Institute Briefing Paper. Available online at: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/9913.pdf (accessed January 15, 2021).

Murray, P., and Longo, M. (2018). Europe's wicked legitimacy crisis: The case of refugees. J. Eur. Integr. 40, 411–425. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2018.1436543

Noordegraaf, M., Douglas, S., Bos, A., and Klem, W. (2017). How to evaluate the governance of transboundary problems? Assessing a national counterterrorism strategy. Evaluation 23, 389–406. doi: 10.1177/1356389017733340

Peters, G. B. (2017). What is so wicked about wicked problems? A conceptual analysis and a research program. Pol. Soc. 36, 385–396. doi: 10.1080/14494035.2017.1361633

Phillips, N. (2018). “The European migrant crisis and the future of the European project,” in The Coming Crisis, eds C. Hay and T. Hunt (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 61–68. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-63814-0_8

Qin, Y. (2016). A relational theory of world politics. Int. Stud. Rev. 18, 33–47. doi: 10.1093/isr/viv031

Rein, M., and Schön, D. (1977). “Problem setting in policy research,” in Using Social Research in Public Policy Making, ed C. H. Weiss (Lexington: Lexington Books), 235–251.

Rittel, H. W. J., and Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Pol. Sci. 4, 155–169. doi: 10.1007/BF01405730

Roberts, N. (2000). Wicked problems and network approaches to resolution. Int. Publ. Manag. Rev. 1, 1–19.

Selg, P. (2016a). Two faces of the ‘Relational Turn'. Polit. Sci. Polit. 49, 7–31. doi: 10.1017/S1049096515001195

Selg, P. (2016b). ‘The Fable of the Bs': Between substantialism and deep relational thinkingabout power. J. Polit. Power 9, 183–205. doi: 10.1080/2158379X.2016.1191163

Selg, P. (2019). “Causation is not everything: On constitution and trans-actional view of social science methodology,” in John Dewey and the Notion of Trans-Action. A Sociological Reply on Rethinking Relations and Social Processes, ed C. Morgner (London: Palgrave), 31–53. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-26380-5_2

Selg, P., Klasche, B., and Nõgisto, J. (2022). Wicked problems and sociology: Buildinga missing bridge through processual relationalism. Int. Rev. Sociol. 2022, 2035909. doi: 10.1080/03906701.2022.2035909

Selg, P., Sootla, G., and Klasche, B. (forthcoming). A Relational Approach to Governing Wicked Problems. From Governance Failure to Failure Governance. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Selg, P., and Ventsel, A. (2020). Introducing Relational Political Analysis. Political Semioticsas a Theory and Method. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Thurnay, L., Klasche, B., Nyman-Metcalf, K., Pappel, I., and Draheim, D. (2017). “The potential of the Estonian e-Governance infrastructure in supporting displaced estonian residents,” in Electronic Government and the Information Systems Perspective. EGOVIS 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, eds A. Kö and E. Francesconi (Berlin: Springer), 236–250. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-64248-2_17

Turnbull, N., and Hoppe, R. (2018). Problematizing' Wickedness': A critique of the wickedproblem concept, from philosophy to practice. Pol. Soc. 38, 315–337. doi: 10.1080/14494035.2018.1488796

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2015). World at War. UNHCR. Available online at: http://www.unhcr.org/556725e69.pdf (accessed January 15, 2021).

Wagenaar, H. (2007). Governance, complexity, and democratic participation: How citizens andpublic officials harness the complexities of neighborhood decline. Am. Rev. Publ. Admin. 37, 17–50. doi: 10.1177/0275074006296208

Wendt, A. (1998). On constitution and causation in international relations. Rev. Int. Stud. 24, 101–118. doi: 10.1017/S0260210598001028

Wivel, A., and Wæver, O. (2018). The power of peaceful change: The crisis of the European Union and the rebalancing of Europe's Regional Order. Int. Stud. Rev. 20, 317–325. doi: 10.1093/isr/viy027

Ylikoski, P. (2013). Causal and constitutive explanations compared. Erkenntnis 78, 277–297. doi: 10.1007/s10670-013-9513-9

Keywords: relationalism, migration, wicked problem, European Migrant Crisis, de-problematization

Citation: Klasche B (2023) The role of ideations in de-problematizing migration crises (and other wicked problems). Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1134457. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1134457

Received: 30 December 2022; Accepted: 06 March 2023;

Published: 17 April 2023.

Edited by:

Svetluša Surova, Bratislava Policy Institute, SlovakiaReviewed by:

Ott Lumi, Meta Advisory Group, EstoniaJohan Rochel, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne, Switzerland

Copyright © 2023 Klasche. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Benjamin Klasche, YmVuamFtaW4ua2xhc2NoZUB0bHUuZWU=

Benjamin Klasche

Benjamin Klasche