- GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, Mannheim, Germany

“Left” and “right” are common concepts when it comes to describing both political attitudes of citizens and politicians or to classifying, for example, parties on the political spectrum. But how do political ideological attitudes emerge? One central factor is political socialization, in which the family is a key socialization agent. However, existing research focuses largely on partisan preferences and how they emerge through family political socialization. Nevertheless, due to multiparty systems, this concept is less suitable in the European context. This paper therefore contributes to filling this research gap by looking at the role of the family as a political socialization agent in the emergence of political ideological attitudes. Hereby the focus is on two key research questions: what difference does the cross-gender transmission of left-right ideology make? How does the parenting style affect intergenerational transmission? These questions are examined using the Cultural Pathways to Economic Self-Sufficiency and Entrepreneurship (CUPESSE) dataset, whose structure allows for several advances on existing studies. First, it contains a high number of cases with more than 4,000 parent-child dyads, which come from a total of 11 European countries and thus allow a view beyond existing single country studies. Furthermore, it contains the classification of the parenting style by the children and thus enables analyses based on the perception of the recipients of the parenting rather than the parent self-assessment. The results of the analysis indicate that existing differences in political ideology between parents and children vary for cross-gender transmission processes. It also shows that the similarity of political ideology between parents and children is influenced by the parenting style, such as whether children experienced warmth from their parents, support in the pursuit of autonomy, or strong controlling behavior.

Introduction

The belief that political orientations are passed on from parents to children is a cornerstone of the study of political socialization. Thus, existing literature agrees that parents are a central political socialization agent as they spend a lot of time with their children, thereby directly and indirectly guiding their children's behavior (Quintelier, 2015). Direct political socialization, for example, takes place when parents themselves are actively involved in politics and communicate this. Existing studies show that parental political involvement also increases the likelihood that their children will be politically active when they grow older (Mcfarland and Thomas, 2006; Cicognani et al., 2012). Indirect political socialization by parents takes place, for example, when parents talk about politics with their respective partners and or directly with their children. Here, too, studies show that when parents regularly talk with their children about politics, children's likelihood of becoming politically active increases (McIntosh et al., 2007; Schmid, 2012). Thus, the general view within most political socialization literature is that parents drive the transmission process by promoting values, role modeling, nurturance, information control, resources, and structuring the child's environment (Weiss, 2020; Hatemi and Ojeda, 2021). However, it is also clear that parents are not the only socialization agents, but social networks, education, peers, religion, media, or even life events can also have an influence on children's political orientation (Mcfarland and Thomas, 2006; Koskimaa and Rapeli, 2015; Quintelier, 2015; Ekström and Shehata, 2018; Grasso et al., 2019; Weiss, 2020; Hatemi and Ojeda, 2021). Nevertheless, parental influences are assumed to be at the forefront and their influence in conjunction with other socialization factors persists throughout the life course (Hatemi and Ojeda, 2021). A finding that is also underscored by qualitative studies on the issue of young adults' role models (Strohmeyer and Weiss, 2021).

Previous research suggests that the successful transmission of political orientations may depend on the parent-child relationship, the mode of communication, the home climate, and other dynamics, although the extent to which these influence the adoption of political orientations is not fully understood.

Therefore, this study takes a closer look at two central aspects. First, the question of what role the gender of the parents and the children play in the transmission process. Existing research comes to different results, ranging from the conclusion that fathers are the more successful socialization agents, to studies that find no difference between mother and father, to studies that see the mother as the more successful transmission agent. Therefore, in the following we will take a closer look at the question to what extent parent-child congruence in political ideology is influenced by same-gender dyads. In contrast, what is clear from existing research on other aspects of political attitudes and behavior is that the relationship between parent and child plays an important role. Family political socialization characterized by a supportive and friendly parenting style usually leads to more successful transmission to the children, which for example in the case of parents regularly talking about politics with their children can lead to a higher political interest among the children, also in their later life. Following this, this study examines two key research questions: what difference does the cross-gender transmission of left-right ideology make? And how does the parenting style affect intergenerational transmission?

To understand these intergenerational processes, the Cultural Pathways to Economic Self-Sufficiency and Entrepreneurship (CUPESSE) dataset is examined. This is an 11-country study of young adults and their parents. This unique dataset contains information on political left-right attitudes of 18–35-year-olds, as well as their parents. In addition, it contains a wealth of information on parenting styles and the relationship between parents and their children, which makes it possible to investigate the research questions mentioned above.

Consideration of these aspects is relevant here for several reasons. Existing research on family political socialization in the context of political attitudes focuses strongly on partisan preferences. A concept that is certainly appropriate in the context of U.S. research and a two-party system. However, it seems less appropriate for the European context and multiparty systems. Instead, the left-right classification is much more common in this context, but little considered so far in relation to the role of political socialization through the family. Moreover, previous research on the role of same-gender dyads on political ideology provides mixed results. This study can contribute to the goal of obtaining clearer results. Furthermore, the database allows making an important contribution. Previous studies have focused on individual countries or combinations of countries based on their data, often with a lower number of parent-child dyads. With the help of the CUPESSE data set and the high number of parent-child dyads, robust results can be delivered here, which allow a European view due to the number of countries.

The remainder is structured as follows: After a presentation of the general theoretical approaches to intergenerational transmission, a comprehensive look at the state of research on intergenerational transmission of left-right ideology and the aspects of gender and parenting style follows. In the following section, the data set and the variables used are outlined before the empirical results of the analyses are presented in section five. Finally, the results are discussed, and a conclusion is drawn.

Theories of intergenerational transmission processes

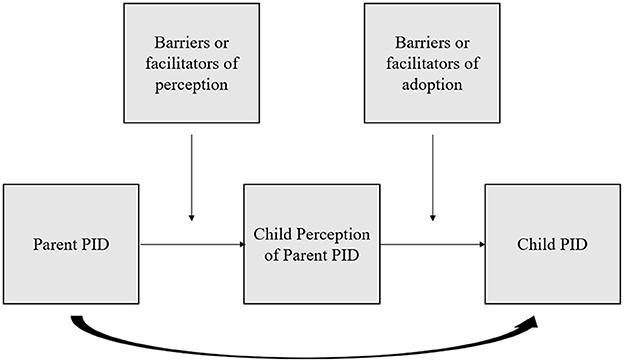

The literature that has emerged over decades to explain transmission from parents to their children has for a long time assumed a basic theoretical mechanism that can be called a direct-transmission approach (Hatemi and Ojeda, 2021). Based on Social Learning Theory (Jennings and Niemi, 1974; Bandura, 1977; Percheron and Jennings, 1981) it is assumed that transmission occurs when the parent and child are concordant and thus the transmission process is basically one-step directly from the parent to the child. What falls short, however, is that such a one-step approach to transmission will almost always disregard how the family environment and characteristics of the parent or child influence the transmission process. For this reason, Hatemi and Ojeda (2021) developed an extended model in which the process of transmission between parent and child is operationalized in two major steps (see Figure 1). In the first step, children must perceive their parents' political attitudes and then, in the second step, decide whether to adopt or reject the perceived orientation for their own position. In this view, transmission is a function of both parent and child since neither correct perception nor adoption of parental orientations alone reflects actual transmission. In this regard, the model also recognizes that this transference process can be guided by a variety of factors. Thus, there are conditioning factors that facilitate or impede the steps of perception and adoption. At the same time, this theoretical model also contains the possibility that the transmission bypasses the child's perception and thus occurs unintentionally, implicitly, or indirectly (Hatemi and Ojeda, 2021).

Figure 1. Theoretical model of Hatemi and Ojeda (2021). Source: Representation according to Hatemi/Ojeda (2021:1100). PID, political ideology.

From the perspective of cultural transmission, the theoretical approach underlines the fact that the observation is clearly to be differentiated from genetics, i.e., it is about cultural and not biological transmission between parents and children. Thus, the concept of cultural transmission includes any traits that arise through any form of non-genetic transmission, such as imprinting, conditioning, observation, imitation, or direct teaching (Schönpflug, 2008). Here, too, the conditioning factors of the transmission process are considered to play an important role. These conditioning factors are often referred to as transmission belts (Schönpflug and Bilz, 2008). These transmission belts can be seen as transmission-enhancing conditions and can be quite different in their nature. Thus, ranging from relational ones, such as parenting style or marital quality of the parents, to sociodevelopmental variables, such as parental education, stage in adolescent development and sibling position, to name just a few examples (Schönpflug and Bilz, 2008).

In summary, from a theoretical perspective, intergenerational transmission is a socialization process that takes place within the family and can occur through direct and indirect transmission (Tosun et al., 2021). An important role is played by who the persons in the transmission process are, what kind of relationship they have with each other, and what content is passed on, in our case political ideology (Trommsdorff, 2008). In addition, it is important to consider the context in which the transmission process takes place (Kagitçibaşi, 2017), for example, in our case within a multiparty system, which will be discussed in more detail later, or the structure within the family, for example, in terms of the level of education or the economic situation. Finally, in addition to the context, there are various transmission belts, such as the parenting style, which can be conducive or obstructive to the transmission process.

Intergenerational transmission of left-right ideology

Most of the existing literature on political socialization, especially the one which laid the foundation of this strand of research decades ago, comes from the U.S. context and focuses on the transmission of partisanship. However, due to the different political systems, this concept is difficult to transfer to the European context. In multiparty systems, as is the case in European countries, the left-right ideology is more likely to be passed on than partisanship, as is the case in the two-party system in the United States. Since a larger number of parties makes it difficult to transfer an attachment to a specific party, ideology proves to be an expectable as well as specifically researchable concept in this context (Van Ditmars, 2022). Nonetheless, most of the European work on intergenerational political transmission examines party identification or party preferences (Kroh and Selb, 2009; Boonen, 2017). What is ignored is that the increasing volatility and decline in party affiliation (Chiaramonte and Emanuele, 2017), as well as the volatility of votes within a bloc (van der Meer et al., 2015), underscore why political socialization processes in Western Europe can be understood in terms of political ideology transmission (Van Ditmars, 2022). Only a few studies, such as Corbetta et al. (2013) for Italy, Rico and Jennings (2016) for Catalonia, Van Ditmars (2022) for Germany and Switzerland and Durmuşoğlu et al. (2023) for the Netherlands, have taken this approach so far, which is why the study presented here aims to contribute further to a broader consideration of this aspect.

Left-right orientation is just one part, besides others such as political interest, of an individual's political identity. Nonetheless, left-right orientation is an important and summarizing measure of political ideology that is particularly useful for politically describing individuals in Europe. Here, “left” and “right” are the terms most used in everyday life to distinguish, for example, parties but also the political ideology of citizens themselves (Van Ditmars, 2022). For decades, a large part of the electorate has been able to classify itself on the left-right scale (Inglehart and Klingemann, 1976; Maier, 2007). Nevertheless, there is also criticism of the concept, noting that the multidimensionality of political space is not reflected by such a simple scale (Huber and Inglehart, 1995). Existing research shows that the meaning of left and right has varied over time and space (Bauer et al., 2017). However, this flexibility makes the concept particularly suitable for looking at intergenerational political socialization (Van Ditmars, 2022). Using the left-right scale as a concept for ideology that adapts its meaning to important political issues and dimensions at a particular point in time means that it is a durable guide to intergenerational transmission that is not limited to a particular political context at a particular point in time. Thus, the examination of this concept within the study allows to contribute to the ever-changing literature of political socialization.

Mothers and fathers within the political socialization process

The question of what role the gender of parents and children plays in the political socialization process has already been explored many times. Thus, studies on the phenomenon of “assortative mating” show that parental couples often resemble each other, also in terms of their political traits. In such a case, it can be assumed that this similarity of parental political preferences results in a more successful transmission to the children, since the children receive uniform cues and no cross-pressures (Bandura, 1977; Van Ditmars, 2022). If the parents differ in their political orientation, the empirical results are more diverse. Early studies showed the father as the dominant socialization agent (Lazarsfeld et al., 1968). Later studies contradicted this and showed both parents as equal socialization agents (Gniewosz et al., 2009; Boonen, 2017). Some studies, on the other hand, showed that the mother is the primary socialization agent (Zuckerman et al., 2007), which can be explained by the fact that she often spends more time with the children (Gidengil et al., 2016) or that she has a different communication style, which is more characterized by conversation (Shulman and DeAndrea, 2014).

Results are similarly mixed when studies on the question of what difference it makes for political socialization if transmission occurs between parent and child from the same gender are reviewed. Based on mechanisms of same-gender identification and role modeling some studies showed same-gender patterns, with particularly stronger ties between mothers and daughter (Jennings and Langton, 1969). In contrast, other studies found no such evidence (Acock and Bengtson, 1978). However, the most recent studies again show that the greater similarity is between mothers and daughters compared to sons, whereas this is not the case when it comes to fathers and sons compared to daughters (Van Ditmars, 2022). Following this, the first hypothesis is:

H1: Parent-child congruence of political ideology is greater for dyads of parent and child of the same gender, than of dyads of different gender.

The moderating role of parenting behavior

As previously stated, transmission belts play an important role in intergenerational transmission. One of these transmission belts is the parenting style (Kitamura et al., 2009; Mcadams et al., 2014). Previous research has shown that parental behavior and parenting style is linked to various aspects of their children, such as children's educational success, social behavior, or mental health (Mcadams et al., 2014). Parenting in general describes the attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that parents exhibit toward their children that create a sustained emotional climate across a wide range of situations (Fernández-Martín et al., 2022).

Based on Baumrind (1967), extended by Maccoby and Martin (1983) and examined in its facets by many recent studies, at least four different parenting styles can be defined. First, the authoritative parenting style within which parents give children clear guidance, keep an eye on their development, and support them in becoming autonomous (Tosun et al., 2021). What is special about this style of parenting is that the parents explain and justify their expectations and yet are open to feedback from the children. At the same time, these parents forgive and pardon instead of punish, when a child does not achieve the set goals (Murray and Mulvaney, 2012). According to Baumrind (1980), authoritative parents see their parental rights and responsibilities as complementary to those of their children. Because this style allows their children to accept their parents values while still maintaining their own curiosity, originality, and spontaneity, this parenting style is described by many as the most effective one (Grusec and Goodnow, 1994). Here, the parental responsiveness is positively associated with trustworthiness and fairness. This essential element of the authoritative parenting style leads to a more successful transmission of values, because the more positively children perceive their parents, the more likely they are to perceive their parents as role models (Tosun et al., 2021).

Second, there is the authoritarian parenting style, which is characterized by a low level of warmth and a high level of demands and control. These parents expect a lot but are not responsive (Kiliçkaya et al., 2021). In this case, the children comply with the parents' wishes to avoid punishment and not because they are motivated in any positive way to accept the parental guidelines. Parents' assertion of power thus prevents successful value transmission and various studies show that instead such upbringing is related to ill-being and maladaptive outcomes (Grusec and Goodnow, 1994; Soenens and Beyers, 2012).

Third, the permissive parenting style. Here, the relational context is characterized by positive affectivity, but with low expectations and a low degree of control over the child's behavior. In this parenting style, parents set few expectations for children, but are still responsive and willing to communicate. In this sense, parents present themselves more as friends than parents and enforce few rules (Murray and Mulvaney, 2012). The result of permissive parenting is often that the self-regulation of the children is not sufficiently promoted and leaves them impulsive, which for example can lead to disadvantages in terms of academic achievement in later life (Aunola et al., 2000).

Fourth, there is the neglectful parenting style, within which parents are neither responsive nor demanding. Here, parents do not use any restrictions or monitoring, but actively reject their parental child-rearing responsibilities (Kiliçkaya et al., 2021). In this sense, neglectful parents are neither responsive nor demanding. They do not support or encourage their child's self-regulation and often fail to monitor the child's behavior (Maccoby and Martin, 1983). This parenting style could also be summarized as general unresponsiveness (Maccoby and Martin, 1983; Aunola et al., 2000).

Following this, existing studies on parenting divide parenting behavior into different dimensions, which include parental warmth, autonomy support, and control (Prinzie et al., 2009; Pinquart, 2016; Fernández-Martín et al., 2022). In this regard, showing affection and support to children as an expression of emotional closeness can be defined as parental warmth. As a result, children are more likely to follow their parents' example, and parental warmth has been shown to increase congruence between parents and children (Maccoby and Martin, 1983). A positive relationship in terms of increasing parent-child congruence can also be assumed when considering parental support for the child's autonomy. If parents allow their children to make their own decisions and solve problems on their own, this describes parental autonomy support (Grolnick et al., 1997). The third aspect, parental control, on the other hand, is expected to have a negative effect on parent-child congruence. If parents exercise supervision and control over the child, children are less likely to follow their parent's example (Maccoby and Martin, 1983). These dimensions are then in turn reflected in the various parenting styles previously named. For example, the neglectful parenting style is characterized by living a low level of parental warmth, autonomy support, and control. Whereas, for example, in the authoritative parenting style, a high level of parental warmth and control is equally lived (Fernández-Martín et al., 2022).

Consequently, the following hypotheses are formed, which will be empirically examined in the further course:

H2: Parent-child congruence of political ideology is positively correlated with parental warmth.

H3: Parent-child congruence of political ideology is positively correlated with parental autonomy support.

H4: Parent-child congruence of political ideology is negatively correlated with parental control.

Research design

Data

The data basis for the following analyses is the CUPESSE data set (Tosun et al., 2018). This contains data on 18–35-year-olds from 11 different European countries, which are Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. Official statistics often define youth as 15–24- or 15–29-year-olds. However, existing research shows that today's young adults take longer than previous generations to complete the major steps of the transition from youth to adulthood (Arnett, 2014). This explains the age frame chosen in the CUPESSE survey. As this survey is explicitly designed to examine mechanisms of intergenerational transmission, interviews with respondents' parents were conducted. To contact respondents' parents, respondents were first asked who they considered to be their mother or father and then asked to provide corresponding contact information for these individuals.1 The response options to this went beyond biological parents and included the spouse/life partner of a particular parent, grandparents, and other individuals who then had to be specified by the respondent. The resulting CUPESSE dataset consists of 20,008 young adults, of which 5,945 had data for at least one parent (Tosun et al., 2019). The relevant dataset for this study then consists of over 4,000 parent-child dyads.

Overall, the sampling frame for the survey was coherent across countries, resulting in probability samples of individuals aged 18 to 35 that were representative of each country in terms of employment status, NUTS 2 region, age group, education, and migration background (Tosun et al., 2019; Weiss et al., 2021). The surveys were conducted online except for Hungary and Turkey in which low internet coverage necessitated face-to-face interviews. Further detailed information on the data set and survey is presented comprehensively by Tosun et al. (2019).

Variables and methodology

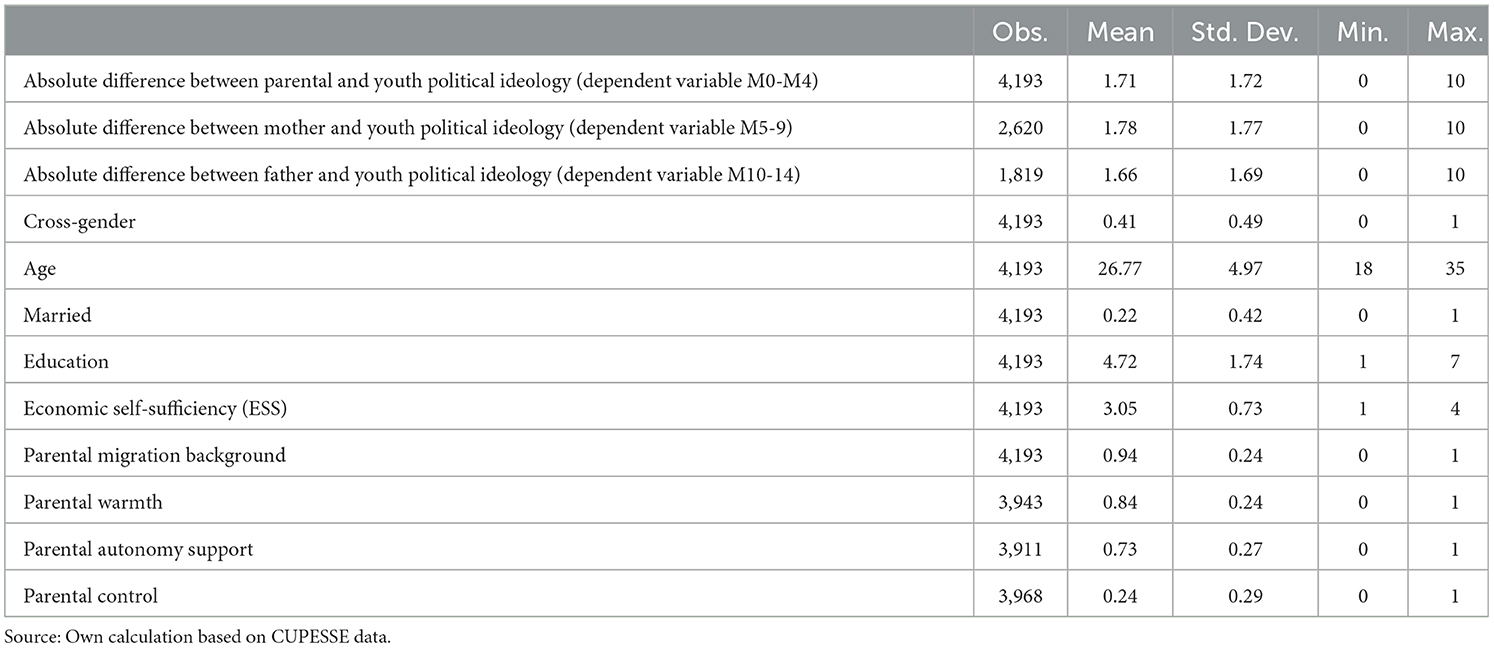

The descriptive information associated with the variables used in the analyses can be found in Table 1. The dependent variable here consists of the absolute difference between the children's political ideology and the parents' political ideology. To capture the political ideology of both children and parents, the following question was asked to both sides: “In politics people sometimes talk of ‘left' and ‘right'. Where would you place yourself on the scale below, where 0 means left and 10 means right?”. In the case of both parents responding (N = 251), the variable takes the average of the respective parent responses.

The independent variables are constituted as follows. “Cross-gender” takes the values 0 or 1, with 1 meaning that the responding parent is of the opposite gender than the child and 0 meaning that the gender of parent and child are the same.

For the variables on parenting style, the children were asked to rate (yes/no) on several aspects and the variables parental warmth, parental autonomy support and parental control take the mean of their respective items. For parental warmth these items were: “I felt that warmth and tenderness existed between me and my [mother/father],” “I felt that my [mother/father] was proud when I succeeded in something I did” and “If things went badly for me my [mother/father] tried to comfort and encourage me.” For parental autonomy support these items were: “My [mother/father] emphasized that every family member should have some say in family decision,” “My [mother/father] encouraged me to be independent” and “My [mother/father] allowed me to choose my own direction in life.” Finally for parental control the items were “My [mother/father] always tried to change how I felt or thought about things” and “My [mother/father] blamed me for other family members' problems.” The selection of the items is done as described by Fernández-Martín et al. (2022) by using existing psychometrically validated measures of parenting behavior: the items on parental warmth stem from the short form of the “Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran”(Arrindell et al., 1999), the items on autonomy support are drawn from the “Autonomy Granting Scale” (Silk et al., 2003; Soenens et al., 2007) and finally the items on parental control stem from the “Psychological Control Scale -Youth Self Report” (Barber, 1996).

The models also include various control variables. In addition to the age of the children (18–35), their marital status, which dichotomously takes the value 1 if they are married, the educational level of the children is also used. For this the respondent were asked what the highest level of education they have successfully completed is, and their answers range from 1, which is ISCED 1–less than lower secondary to 7, which is ISCED V2–higher tertiary education (≧MA level).2

Furthermore, another control variable includes the family's financial situation when the young adults themselves were around 14 years old. For this, the young adults were asked: “Thinking about your family's financial situation when you were about 14 years old. Which of the following statements applied to your family?,” “My family was able to pay its bills,” “We could afford extras for ourselves,” “We could afford to live in decent housing” and “My family was able to put money in a savings account.” For all these statements, the children could indicate whether this was never(=1)/sometimes(=2)/most of the time(=3)/always(=4) true.

Finally, the models consider parental migration background. The corresponding variable takes the value 1 if the interviewed mother/father was born in a country other than the country in which the child lives. The models control for this, as existing research shows that in the case of family migration, the effectiveness of transmission from parents to children may be lower (Schönpflug and Bilz, 2008). This can happen for several reasons, firstly because the culture of origin in the host country can be dysfunctional and thus the successor generation does not accept the transmission and secondly because the parents actively try not to pass it on (Schönpflug and Bilz, 2008).

Due to the nature of the dependent variable, linear regression models are calculated in the further course. The models are weighted. According to the recommendations of the CUPESSE survey they include post-stratification weights. Post-stratification weights were based on gender, age, education and NUTS2 region and the population frequencies came from the European Union Labor Force Survey. Due to the data structure the following linear regression models contain country fixed effects with standard errors clustered by countries.

Results

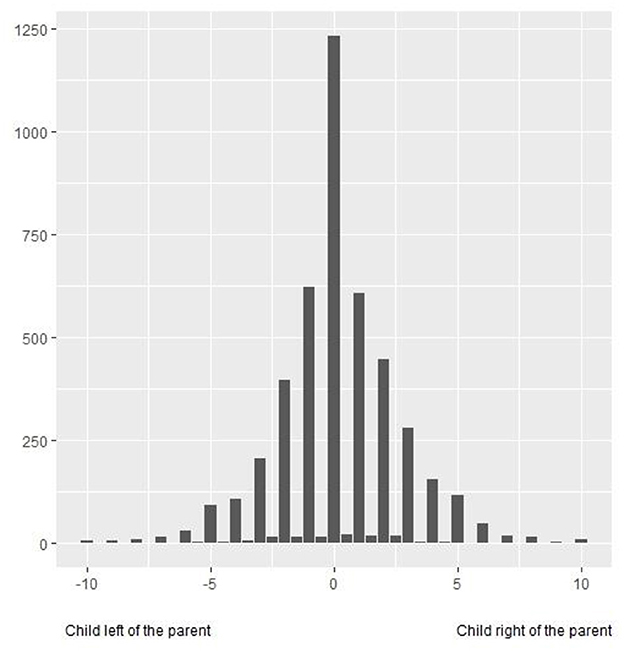

To begin with, the question arises to what extent children and their parents differ in their political ideology. To this end, Figure 2 descriptively represents the corresponding distribution. This is the relative difference and not the absolute difference, which is the dependent variable in the later models. Based on the relative values in the representation, the largest proportion is congruent (value=0), but that substantial proportions of respondents also deviate from the political ideology of their parents. Here, +10 and −10 represent the extreme values. With positive values, the political ideology of the parents is thus further to the right, and with negative values in the figure, the parental political ideology is further to the left than the political ideology of their children.

Figure 2. Descriptive representation of the parent-child congruence of political ideology. Source: Own calculation based on CUPESSE data.

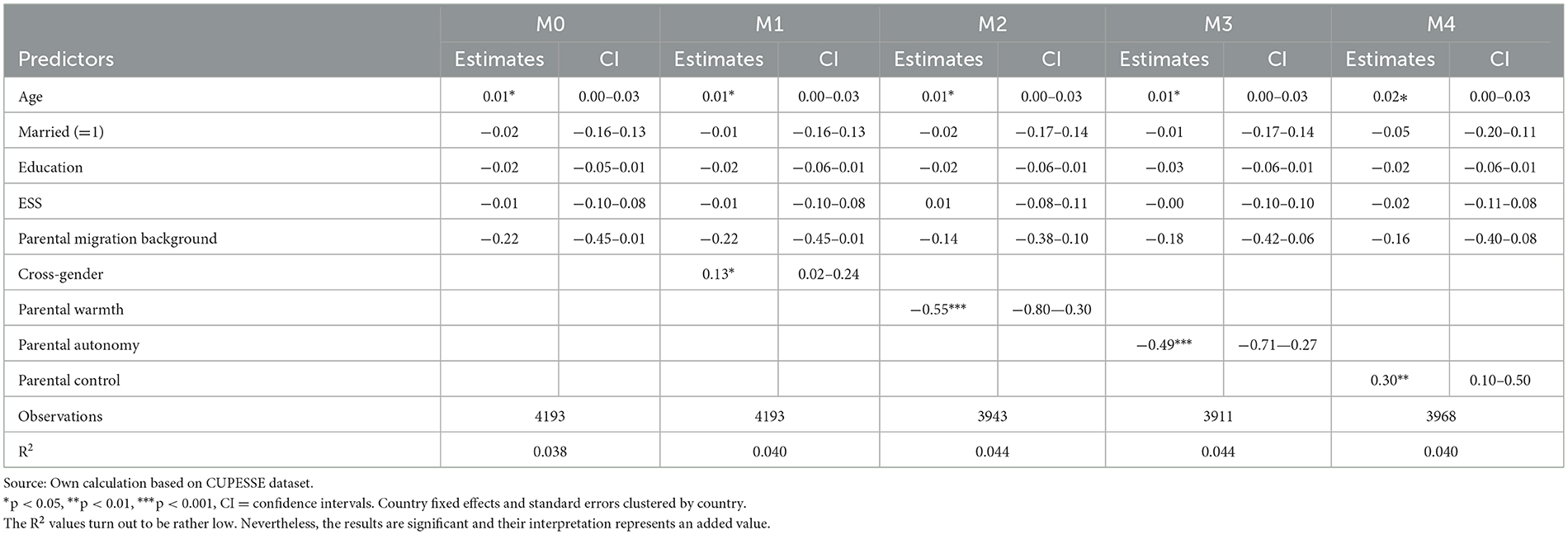

Table 2 then represents the models corresponding to the hypotheses from the section Intergenerational transmission of left-right ideology. The first hypothesis assumed that the parent-child congruence of political ideology is greater for dyads of parent and child of the same gender, than of dyads of different gender. The first model (M1) shows a confirmation of this hypothesis. The coefficient of “cross-gender” shows that same-gender parent-child pairs are closer together in their ideological orientation, whereas opposite-gender dyads are further apart on the left-right scale.

Table 2. Results of the empirical models (dependent variable = absolute difference between parental and youth political ideology).

The further hypotheses focused on the parenting style. Model 2 shows that parental warmth increases the ideological similarity of parents and their children. Thus, hypothesis 2 can be confirmed. The same applies to the question of the role of parental autonomy support (H3). Here, too, it can be seen (M3) that the ideological similarity increases with increasing parental support for the child's autonomy. Finally, the fourth hypothesis can also be confirmed. The last model (M4) shows that a controlling parenting style has a negative effect on ideological similarity. Thus, children who have experienced a controlling parenting style differ more ideologically from their parents.

Further, it is important to consider the control variables. Across M1-M4, all included control variables show no influence on the ideological similarity of parents and their children. Only age shows a weakly significant influence, which can make one assume that while growing up, an ideological distance from parents can take place.

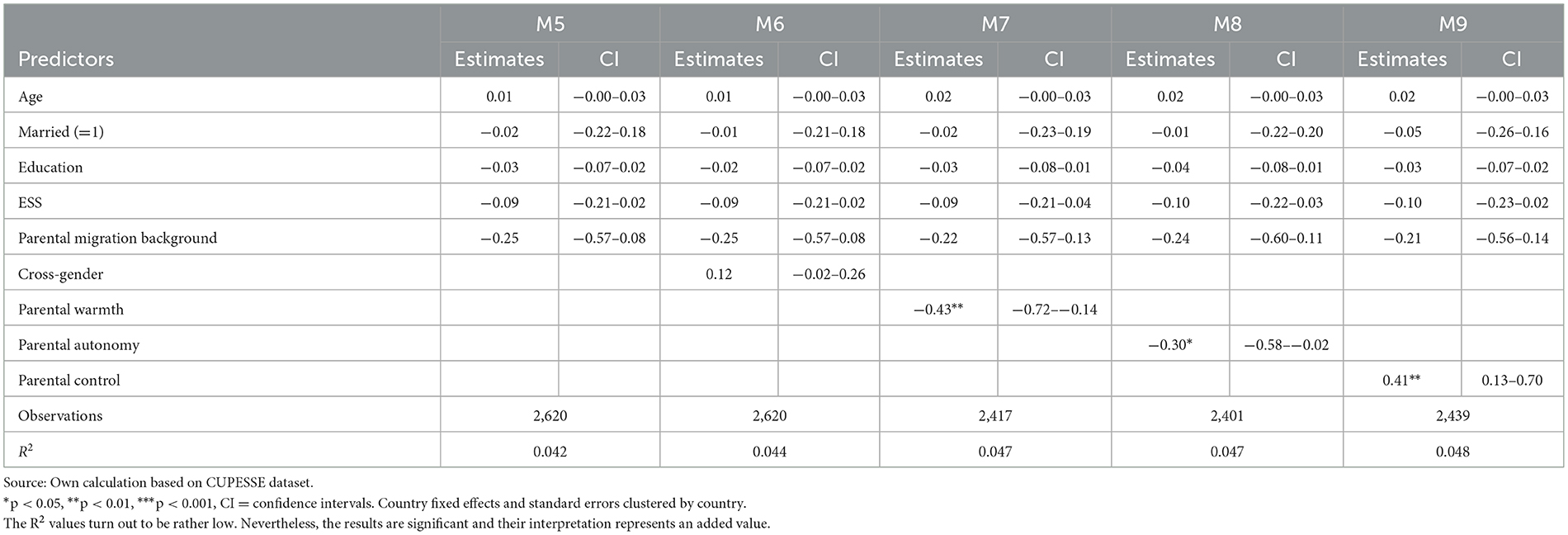

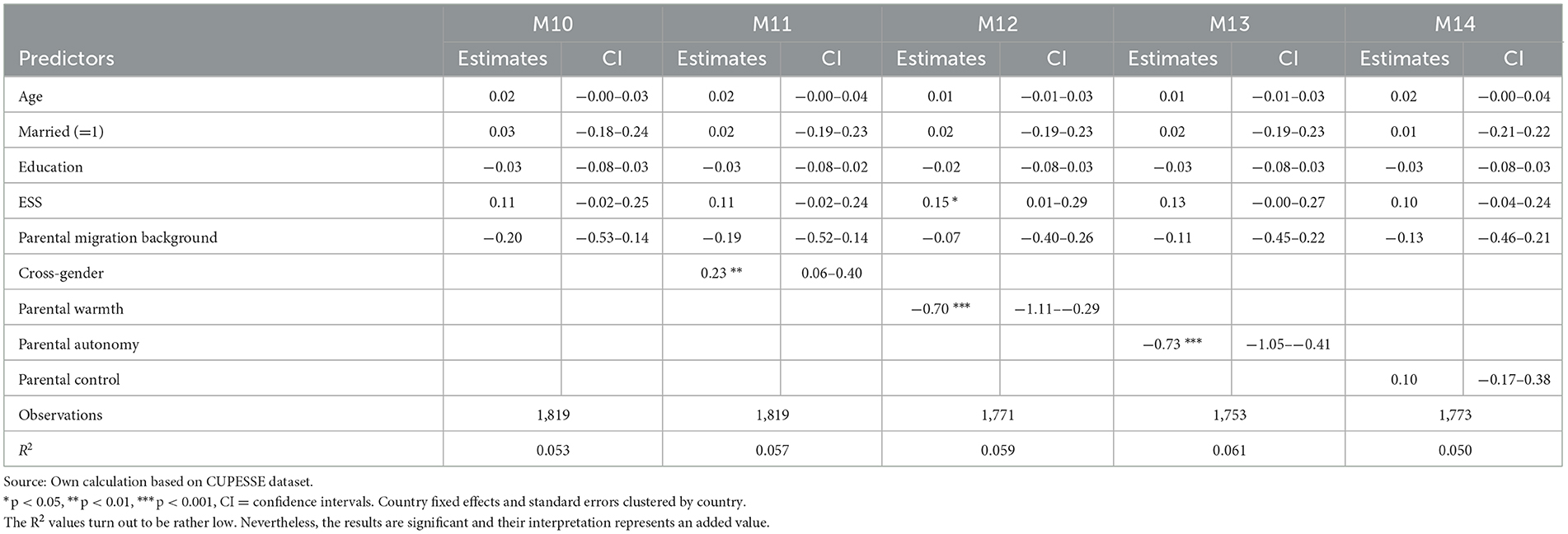

Tables 3, 4 now provide a more in-depth look at the role of gender and its combination with parenting style. The structure of the calculated models is the same as in Table 2, but the dependent variables differ. In models M5-M9, the difference between maternal and child political ideology is now the dependent variable, while in models M10-14, the difference between paternal and child political ideology forms the dependent variable.

Table 3. Results of the empirical models (dependent variable = absolute difference between mother and youth political ideology).

Table 4. Results of the empirical models (dependent variable = absolute difference between father and youth political ideology).

Here the results show that the same gender between parent and child does not seem to have any influence in the case of mothers. Further there are differences regarding parenting style. Thus, for mothers, it remains that warmth and autonomy support promote ideological closeness and control reduces it. For fathers, on the other hand, parental control shows no significant effect, and the effects for warmth and autonomy promotion whiten in the same direction as for mothers, only with a stronger expression of the correlation.

Discussion and conclusion

This study investigates the intergenerational transmission of left-right ideology in 11 European countries, by testing hypotheses both regarding same-gender dynamics and parenting styles. The results underline the applicability of the classic family political socialization model to the transmission processes of left-right positions (Van Ditmars, 2022) and how both gender and parenting styles are consequential for this process.

Besides the descriptive observation that parents and their children not infrequently differ in their political left-right classification, three central results of the empirical analysis should be emphasized: First, same-gender parent-child pairs are closer together in their ideological orientation than parents and children of different gender. Second, parenting style plays a relevant role in the transmission process, with parental warmth and autonomy promotion proving beneficial and controlling behavior proving detrimental to the transmission process. Third, there are differences in the relevance of parenting style for the transmission process for mothers and fathers. More precisely, controlling parenting behavior only negatively influences the transmission process originating from the mother and not the ones originating from the father.

Thereby, the results of this study have important implications for the mechanisms underlying political socialization. Most of the literature looking at left-right transmission within the family has not considered the types of parenting styles addressed in this study. The results nevertheless support the general relevance of transmission belts known from research on cultural transmission processes (Schönpflug and Bilz, 2008). At the same time, they extend the literature by showing that these transmission belts are not only relevant for cultural values but also for aspects of political socialization.

Of course, this study is not without shortcomings. In general, the present analyses do not allow any statements about causality but present correlations, which are theoretically argued in a plausible way. Furthermore, and although the dataset used is unique and provides a basis for the analyses due to its high number of parent-child dyads, a few items are missing that would allow to analyze the political socialization process in more detail. For example, indicators that show how the child perceives and classifies the political orientation of his or her own parents, and further items regarding, for example, the frequency of political discussions between parents and children or data on political participation behavior of both parents and children could be thought of here. Future studies may be able to include such items and would thus allow to delve even deeper into the mechanisms behind parenting style and the intergenerational transmission of left-right ideology. In addition, there are only 251 young adults in the dataset used where both parents were interviewed. Ideally, the questions about the role of the gender of parent and child would be examined in a setting in which both parents were interviewed for all young adults, also considering that for the data collection process there is the possibility that the children indicated the particular parent with whom they felt closer as the interview partner. Future data collection should take this into account, and thus allow for an even deeper examination of the differential influences of mothers and fathers.

Despite the frequently postulated tendency toward the declining importance of the family in the political socialization process, increasing individualization and political volatility, the present study was able to show that the intergenerational transmission of left-right ideology plays an important role in the political self-identification of individuals. The gender differences in the intergenerational reproduction of political ideology show that children are not passive recipients in the political socialization process. At the same time, the parenting behavior of mothers and fathers proofs to be important, thus the relationship between parent and child plays an important role not only in everyday life but also in the political sphere.

Data availability statement

The dataset analyzed for this study can be found in the GESIS data archive (datafile: ZA7475)-https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13042.

Author contributions

JW conceived and designed the article, performed the analysis, wrote the manuscript, revised the manuscript, reread it, and finally approved the submitted version.

Funding

The publication of this article was funded by the Open Access Fund of the Leibniz Association.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In this sense, the selection of parents is random. Nonetheless, a bias can occur as maybe the parent with whom the child feels more closely connected is selected by the child to pass on his or her contact data.

2. ^The detailed naming of all education levels is: “(1) ISCED I, less than lower secondary”, “(2) ISCED II, lower secondary”, “(3) ISCED IIIb, lower tier upper secondary”, (4) ISCED IIIa, upper tier upper secondary”. “(5) ISCED IV, advanced vocational, sub-degree”, “(6) ISCED V1, lower tertiary education, BA level” and “(7) ISCED V2, higher tertiary education, ≧ MA level”.

References

Acock, A. C., and Bengtson, V. L. (1978). On the relative influence of mothers and fathers: a covariance analysis of political and religious socialization. J. Marriage Fam. 40, 519–530. doi: 10.2307/350932

Arnett, J. J. (2014). Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Arrindell, W. A., Sanavio, E., Aguilar, G., Sica, C., Hatzichristou, C., Eisemann, M., et al. (1999). The development of a short form of the EMBU1Swedish acronym for Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran (“My memories of upbringing”)0.1: Its appraisal with students in Greece, Guatemala, Hungary and Italy. Pers. Individ. Differ. 27, 613–628. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00192-5

Aunola, K., Stattin, H., and Nurmi, J.-E. (2000). Parenting styles and adolescents' achievement strategies. J. Adolesc. 23, 205–222. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0308

Barber, B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: revisiting a neglected construct. Child Dev. 67, 3296–3319. doi: 10.2307/1131780

Bauer, P. C., Barberá, P., Ackermann, K., and Venetz, A. (2017). Is the left-right scale a valid measure of ideology? Polit. Behav. 39, 553–583. doi: 10.1007/s11109-016-9368-2

Baumrind, D. (1967). Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 75, 43–88.

Baumrind, D. (1980). New directions in socialization research. Am. Psychol. 35, 639–652. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.35.7.639

Boonen, J. (2017). Political equality within the household? The political role and influence of mothers and fathers in a multi-party setting. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 38, 577–592. doi: 10.1177/0192512116639745

Chiaramonte, A., and Emanuele, V. (2017). Party system volatility, regeneration and de-institutionalization in Western Europe (1945–2015). Party Politics. 23, 376–388. doi: 10.1177/1354068815601330

Cicognani, E., Zani, B., Fournier, B., Gavray, C., and Born, M. (2012). Gender differences in youths' political engagement and participation. The role of parents and of adolescents' social and civic participation. J. Adolesc. 35, 561–576. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.10.002

Corbetta, P., Tuorto, D., and Cavazza, N. (2013). “Parents and children in the political socialization process: Changes in Italy over thirty-five years.” in: Growing into politics. Context and timing of political socialization, ed S. Abendschön (Colchester: ECPR Press).

Durmuşoğlu, L. R., de Lange, S. L., Kuhn, T., and van der Brug, W. (2023). The intergenerational transmission of party preferences in multiparty contexts: Examining parental socialization processes in the Netherlands. Polit. Psychol. 1–19. doi: 10.1111/pops.12861. [Epub ahead of print].

Ekström, M., and Shehata, A. (2018). Social media, porous boundaries, and the development of online political engagement among young citizens. New Media Soc. 20, 740–759. doi: 10.1177/1461444816670325

Fernández-Martín, F. D., Arco-Tirado, J. L., Mitrea, E.-C., and Littvay, L. (2022). The role of parenting behavior's on the intergenerational covariation of grit. Curr. Psychol. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03185-w

Gidengil, E., Wass, H., and Valaste, M. (2016). Political socialization and voting: the parent–child link in turnout. Polit. Res. Q. 69, 373–383. doi: 10.1177/1065912916640900

Gniewosz, B., Noack, P., and Buhl, M. (2009). Political alienation in adolescence: associations with parental role models, parenting styles, and classroom climate. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 33, 337–346. doi: 10.1177/0165025409103137

Grasso, M. T., Farrall, S., Gray, E., Hay, C., and Jennings, W. (2019). Thatcher's children, blair's babies, political socialization and trickle-down value change: an age, period and cohort analysis. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 49, 17–36. doi: 10.1017/S0007123416000375

Grolnick, W. S., Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1997). “Internalization within the family: The self-determination theory perspective.” in Parenting and children's internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory, eds J. E. Grusec, and L. Kuczynski (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley).

Grusec, J. E., and Goodnow, J. J. (1994). Impact of parental discipline methods on the child's internalization of values: a reconceptualization of current points of view. Dev. Psychol. 30, 4–19. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.30.1.4

Hatemi, P. K., and Ojeda, C. (2021). The role of child perception and motivation in political socialization. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 1097–1118. doi: 10.1017/S0007123419000516

Huber, J., and Inglehart, R. (1995). Expert interpretations of party space and party locations in 42 societies. Party Politics. 1, 73–111. doi: 10.1177/1354068895001001004

Inglehart, R., and Klingemann, H. D. (1976). “Party identification, ideological preference and the left-right dimension among western mass publics.” in: Party identification and beyond: Representations ofvoting and party competition, eds I. Budge, I. Crewe, and D. Farlie (Wiley and Sons).

Jennings, M. K., and Langton, K. P. (1969). Mothers versus fathers: the formation of political orientations among young Americans. J. Politics. 31, 329–358. doi: 10.2307/2128600

Jennings, M. K., and Niemi, R. G. (1974). The Political Character of Adolescence: The Influence of Family and Schools. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kagitçibaşi, Ç. (2017). Family, Self, and Human Development Across Cultures: Theory and Applications. New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315205281

Kiliçkaya, S., Uçar, N., and Denizci Nazligül, M. (2021). A systematic review of the association between parenting styles and narcissism in young adults: from baumrind's perspective. Psychol. Rep. 00332941211041010. doi: 10.1177/00332941211041010

Kitamura, T., Shikai, N., Uji, M., Hiramura, H., Tanaka, N., and Shono, M. (2009). Intergenerational transmission of parenting style and personality: direct influence or mediation? J. Child Fam. Stud. 18, 541–556. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9256-z

Koskimaa, V., and Rapeli, L. (2015). Political socialization and political interest: the role of school reassessed. J. Political Sci. Educ. 11, 141–156. doi: 10.1080/15512169.2015.1016033

Kroh, M., and Selb, P. (2009). Inheritance and the dynamics of party identification. Polit. Behav. 31, 559. doi: 10.1007/s11109-009-9084-2

Lazarsfeld, P. F., Berelson, B., and Gaudet, H. (1968). The People's Choice: How the Voter Makes Up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Maccoby, E. E., and Martin, J. A. (1983). “Socialization in the context of the family: parent-child interaction.” In: Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, Personality, and Social Development, Eds P. H. Mussen and E. M. Hetherington (New York: Wiley).

Maier, P. (2007). “Left-right orientations.” in: The Oxford handbook ofpolitical behavior, Eds R. J. Dalton, and H. D. Klingemann (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Mcadams, T. A., Neiderhiser, J. M., Rijsdijk, F. V., Narusyte, J., Lichtenstein, P., and Eley, T. C. (2014). Accounting for genetic and environmental confounds in associations between parent and child characteristics: a systematic review of children-of-twins studies. Psychol. Bull. 140, 1138–1173. doi: 10.1037/a0036416

Mcfarland, D. A., and Thomas, R. J. (2006). Bowling young: how youth voluntary associations influence adult political participation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 71, 401–425. doi: 10.1177/000312240607100303

McIntosh, H., Hart, D., and Youniss, J. (2007). The influence of family political discussion on youth civic development: which parent qualities matter? PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 40, 495–499. doi: 10.1017/S1049096507070758

Murray, G. R., and Mulvaney, M. K. (2012). Parenting styles, socialization, and the transmission of political ideology and partisanship. Politics and Policy. 40, 1106–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-1346.2012.00395.x

Percheron, A., and Jennings, M. K. (1981). Political continuities in french families: a new perspective on an old controversy. Comp. Polit. 13, 421–436. doi: 10.2307/421719

Pinquart, M. (2016). Associations of parenting styles and dimensions with academic achievement in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 475–493. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9338-y

Prinzie, P., Stams, G. J. J. M., Dekovi,ć, M., Reijntjes, A. H. A., and Belsky, J. (2009). The relations between parents' Big Five personality factors and parenting: a meta-analytic review. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 97, 351–362. doi: 10.1037/a0015823

Quintelier, E. (2015). Engaging adolescents in politics:the longitudinal effect of political socialization agents. Youth Soc. 47, 51–69. doi: 10.1177/0044118X13507295

Rico, G., and Jennings, M. K. (2016). The formation of left-right identification: pathways and correlates of parental influence. Polit. Psychol. 37, 237–252. doi: 10.1111/pops.12243

Schmid, C. (2012). The value “social responsibility” as a motivating factor for adolescents' readiness to participate in different types of political actions, and its socialization in parent and peer contexts. J. Adolesc. 35, 533–547. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.03.009

Schönpflug, U. (2008). “Introduction to cultural transmission: psychological, developmental, social, and methodological aspects.” in Cultural Transmission: Psychological, Developmental, Social, and Methodological Aspects, Ed U. Schönpflug (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Schönpflug, U., and Bilz, L. (2008). “The transmission process: mechanisms and contexts.” in: Cultural Transmission: Psychological, Developmental, Social, and Methodological Aspects, Ed U. Schönpflug (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Shulman, H. C., and DeAndrea, D. C. (2014). Predicting success: revisiting assumptions about family political socialization. Commun. Monogr. 81, 386–406. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2014.936478

Silk, J. S., Morris, A. S., Kanaya, T., and Steinberg, L. (2003). Psychological control and autonomy granting: opposite ends of a continuum or distinct constructs? J. Res. Adolesc. 13, 113–128. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.1301004

Soenens, B., and Beyers, W. (2012). The cross-cultural significance of control and autonomy in parent–adolescent relationships. J. Adolesc. 35, 243–248. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.02.007

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., Luyckx, K., Goossens, L., Beyers, W., et al. (2007). Conceptualizing parental autonomy support: adolescent perceptions of promotion of independence versus promotion of volitional functioning. Dev. Psychol. 43, 633–646. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.633

Strohmeyer, R., and Weiss, J. (2021). “Between adaption and rejection: intergenerational transmission of resources and work values in Germany.” in Intergenerational Transmission and Economic Self-Sufficiency, Eds J. Tosun, D. Pauknerová, and B. Kittel (Cham: Palgrave Macmillian). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-17498-9_6

Tosun, J., Arco-Tirado, J. L., Caserta, M., Cemalcilar, Z., Freitag, M., Hörisch, F., et al. (2019). Perceived economic self-sufficiency: a country- and generation-comparative approach. Eur. Political Sci. 18, 510–531. doi: 10.1057/s41304-018-0186-3

Tosun, J., Hörisch, F., Schuck, B., Shore, J., Woywode, M., Strohmeyer, R., et al. (2018). CUPESSE: Cultural Pathways to Economic Self-Sufficiency and Entrepreneurship. GESIS Datenarchiv, Köln. ZA7475 Datenfile Version 1.0.0.

Tosun, J., Kittel, B., and Pauknerová, D. (2021). “Theoretical framework.” in Intergenerational Transmission and Economic Self-Sufficiency, eds J. Tosun, D. Pauknerová, and Kittel, B. (Cham: Palgrave Macmillian). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-17498-9

Trommsdorff, G. (2008). “Intergenerational relations and cultural transmission.” in: Cultural Transmission: Psychological, Developmental, Social, and Methodological Aspects, Ed U. Schönpflug (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511804670.008

van der Meer, T. W., Van Elsas, E., Lubbe, R., and Van Der Brug, W. (2015). Are volatile voters erratic, whimsical or seriously picky? A panel study of 58 waves into the nature of electoral volatility (The Netherlands 2006–2010). Party Politics. 21, 100–114. doi: 10.1177/1354068812472570

Van Ditmars, M. M. (2022). Political socialization, political gender gaps and the intergenerational transmission of left-right ideology. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 62, 1−22. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12517

Weiss, J. (2020). What Is youth political participation? literature review on youth political participation and political attitudes. Front. Polit. Sci. 2, 1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.00001

Weiss, J., Ferrante, L., and Soler-Porta, M. (2021). There is no place like home! how willing are young adults to move to find a job? Sustainability. 13, 7494. doi: 10.3390/su13137494

Keywords: political socialization, youth, parenting, left-right ideology, intergenerational transmission

Citation: Weiss J (2023) Intergenerational transmission of left-right ideology: A question of gender and parenting style? Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1080543. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1080543

Received: 26 October 2022; Accepted: 07 March 2023;

Published: 23 March 2023.

Edited by:

Anne-Marie Jeannet, University of Milan, ItalyReviewed by:

Susan Banducci, University of Exeter, United KingdomAndrés Santana, Autonomous University of Madrid, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Weiss. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Julia Weiss, anVsaWEud2Vpc3NAZ2VzaXMub3Jn

Julia Weiss

Julia Weiss