- Institute for Politics and Strategy, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

What explains the explosion of coup activity in Africa over the last few years? To answer this question, this article presents narrative summaries—a current history—of all eleven coups attempts in Africa between August 2020 and November 2022. We then discuss the most relevant causal explanations for the observed increase in coup frequency in Africa in this period. Though we find relatively little evidence of direct coup diffusion or democratic backsliding as coup triggers, our findings suggest that coup-struck African countries over the last few years are disproportionately poor, have a recent history of coups, and face ongoing dilemmas of democratic consolidation. Ongoing Islamist insurgencies may have helped precipitate recent coups in West Africa but not elsewhere.

1. Introduction

For six decades, Africa has been one of the most coup-prone regions in the world. According to the Colpus dataset, a new dataset of coup types and characteristics,1 the region has suffered a total of 222 coup attempts since 1946, more than any other world region.2 As of 2022, 45 of the region's 54 countries have suffered one or more coup attempts.3 The average African state has suffered four coup attempts since independence, with Sudan having the most (17), including two just last year.

At their historic peak in the 1960s, nearly thirty percent of all African states had suffered one or more coup attempts in the prior two years. Cold War Africa was home to many fledgling and politically unstable countries that were (1) extremely poor and suffering from low economic growth (Collier and Hoeffler, 2005), (2) rife with ethnic tensions and violence (Roessler, 2011; Harkness, 2016, 2018), and (3) governed by autocratic and corrupt personalist regimes (Jackson and Rosberg, 1982, 1984; Decalo, 1989). Many African countries appeared mired in an endemic “coup trap” (Londregan and Poole, 1990), with poverty causing coups (and dictatorship) and vice versa.

The end of the Cold War brought a measure of political optimism for the region as many previously entrenched authoritarian regimes collapsed, Western aid donors—freed from the competing strategic imperative to balance the Soviet Union—were able to more successfully condition continued aid on democratic reform (Dunning, 2004), democratic elections spread (Lindberg and Clark, 2008), and “anti-coup” norms proliferated within international organizations (e.g., Wobig, 2015). The African Union (AU), launched in 2002, arguably became a “norm entrepreneur” delegitimizing coups in Africa (Souaré, 2014). The threat and imposition of sanctions and refusal to recognize post-coup governments—especially in countries most dependent on Western foreign aid (Marinov and Goemans, 2014)—was credited with altering the cost-benefit calculation of would-be coup plotters and thereby deterring coups in Africa (Powell et al., 2016). Observers welcomed the decline of coups in Africa in the 1990s and 2000s (Clark, 2007), with 2007 and 2018 marking the first years in over half a century that there had not been a single coup attempt in Africa. By 2018, the share of African states with coup attempts over the last two years had fallen nearly 15-fold from its Cold War peak to an all-time low of less than two percent.4

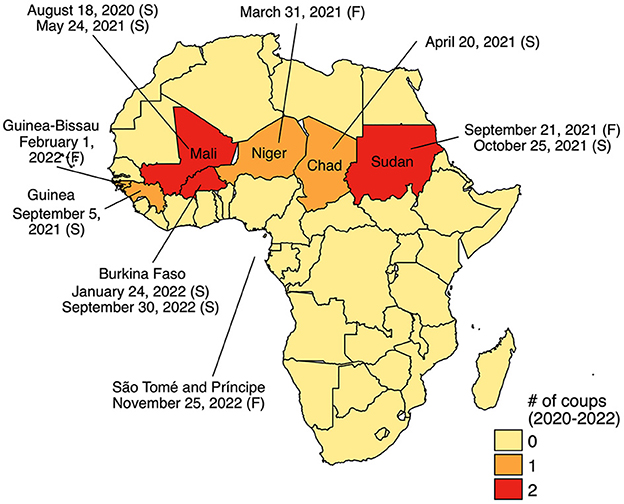

The decline of coups in Africa in the early 21st century did not last, with 11 coup attempts in Africa between August 2020 and November 2022. As shown in Figure 1, five African countries suffered seven successful coups in this period: Mali (August 2020 and May 2021), Chad (April 2021), Sudan (October 2021), Burkina Faso (January and September 2022, and Guinea (September 2022). Four African countries also faced failed coup attempts: Niger (March 2021), Sudan (September 2021), Guinea-Bissau (February 2022), and São Tomé and Príncipe (November 2022).

Figure 1. Geographic distribution of coup attempts (total per country) in Africa, 2020–2022. Source: Colpus dataset, updated by corresponding author through December 2022. S in parentheses denotes a successful coup and F denotes a failed coup attempt.

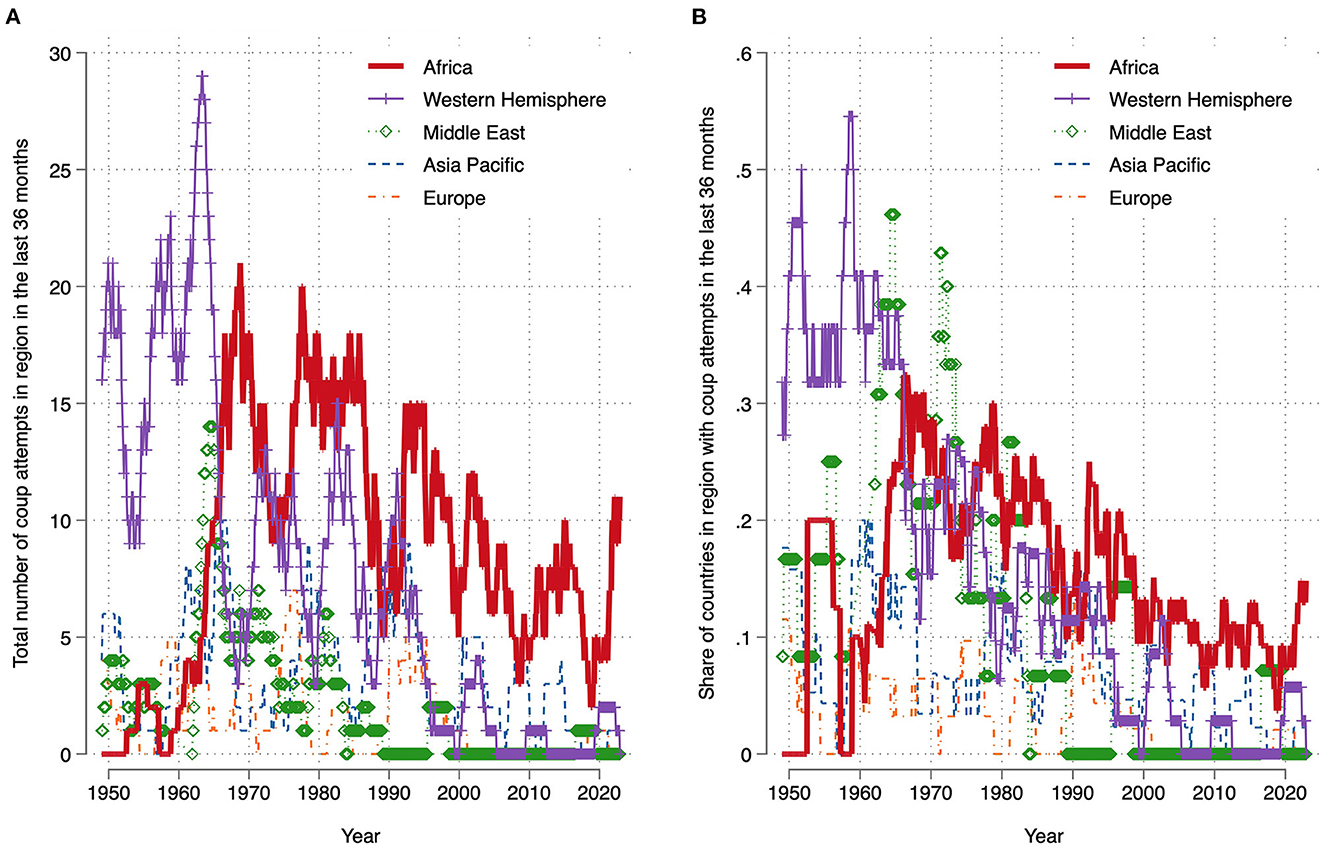

By the end of 2022, 13 percent of African countries had suffered coups in the prior two years, a six-fold increase from just four years earlier. Even more strikingly, all but one coup worldwide since the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic has been in Africa (Chin, 2022).5 Figure 2 shows the total number of coups (Figure 2A) and share of countries suffering coup attempts (Figure 2B) in the past three years for five world regions. In contrast to other regions such as the Western Hemisphere and Middle East where coups have declined from their Cold War peaks and remain at historically low levels, Africa has seen a resurgence of coups. Coup prevalence in Africa has not gone back to Cold War levels, but is higher than any other point in the last two decades.

Figure 2. Total number of coup attempts (A) and share of countries with coup attempts (B) in region in the last 36 months.

Understanding why there has been a resurgence of coups in part of Africa in the last few years—but not in other regions—is vitally important for actors seeking to arrest “coup contagion” and promote democracy in Africa. To contribute to this effort, we draw inspiration from classic coup literature on Africa that centered historical narratives to understand political developments (e.g., First, 1970; Welch, 1970; Decalo, 1976). Our approach parallels that of Patrick McGowan, who for decades meticulously documented coup plots and attempts for all African countries and used the resulting narratives and data to analyze the causes of coups in Africa (McGowan and Johnson, 1984; McGowan, 2003, 2005, 2006). Our narratives also are intended to complement those in the recently published Historical Dictionary of Modern of Coups D'état (Chin et al., 2022).

Before proceeding, it is worth acknowledging the limits of our narrative-driven (qualitative) and comparative (small-N/medium-N) research design. On the one side, it comes at the cost of the level of historical or ethnographic detail one could ideally include if restricting attention to a single-country or single-coup case study.6 On the other side, our relatively small number of cases—less than a dozen over two years—and the proximity to the current coup wave—more will come to light on the causes, meaning, and legacy of these coups only in the fullness of time—means that our inferences must be considered tentative. We hope that our narratives provide inspiration for further field research and large-N cross-national quantitative studies of recent coups in Africa. To be clear, we aim only to write a first history, not the final history, on recent coups in Africa.

2. A current history of coups in Africa, 2020–2022

Between the onset of the global pandemic in 2020 and this writing (December 2022), there have been 11 coup attempts in Africa, of which 7 succeeded. We briefly summarize each case below (in chronological order) for background and context before discussing common causes and legacies.

2.1. Mali: August 18, 2020

In the wake of the March 2012 coup in Mali, which was triggered by military grievances over inadequate government support to contain a Tuareg rebellion in the north, civilian democratic rule was restored (Chin et al., 2022, p. 731–733). Although the 2018 elections were deemed credible to observers from the European Union and African Union, Ibrahim Keïta's re-election to a second term in 2018 was marred by electoral violence in the first round, low turnout in the second round (which he easily won), and opposition allegations of fraud (Felter and Bussemaker, 2020).

In 2020, the opposition accused President Keïta of using intimidation tactics and buying votes in parliamentary elections. After the constitutional court tossed out results in 31 districts in April, Keïta installed his own candidates. The June 5 movement-Rally of Patriotic Forces (M5-RFP), led by Mahmoud Dicko, a popular conservative imam, accused Keïta of violating the constitution and launched protests calling for his ouster. Throughout the summer, tens of thousands of people mobilized over complaints of endemic corruption, weakness dealing with Islamic insurgency, police violence against protestors in June (Felter and Bussemaker, 2020; Maclean, 2020a), and a crumbling economy exacerbated by lockdowns and unemployment that grew worse in 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic (Paquette, 2020a). Keïta agreed to negotiate with the opposition and offered concessions short of resignation. In July 2020, Keïta offered concessions and said he would dissolve the constitutional court and free some political prisoners (Paquette, 2020f). After protesters attacked the parliament building, Keïta's son Karim, a target of opposition criticism for his “playboy” lifestyle, resigned as chairman of parliament's powerful defense and security committee but said he would remain an MP (Agence France-Presse, 2020; Sangare and Adebayo, 2020). Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) mediators rejected opposition demands that Keïta be forced to resign, noting that his 2018 election was legitimate. ECOWAS called for the resignation of the 31 controversial MPs and called on the opposition to accept a new national unity government (Deutsche Welle, 2020; Maclean et al., 2020; Nagourney, 2020). However, the M5-RFP, gaining momentum, refused to stop protesting until Keïta resigned.

Then, on Tuesday, August 18, 2020, in a replay of events that led to the 2012 coup, a mutiny broke out at the Kati military camp 10 miles north of the capital Bamako. Led initially by Col. Malick Diaw, deputy head of Kati military camp, and Col. Sadio Camara, the former head of the Kati military academy, mutineers in pickup trucks began moving into Bamako, closing roads, and arresting senior officials, including the finance minister and president of the national assembly (BBC, 2020; Maclean, 2020a; Paquette, 2020a). Pictures posted to WhatsApp showed the home of the minister of justice on fire (Paquette, 2020a). Soldiers surrounded the national television station and fired shots into the air (Paquette, 2020e). Thousands of anti-government demonstrators cheered the mutineers on, with spontaneous crowds blowing vuvuzelas and revving motorcycles at Bamako's Independence Square. One sign read, “Goodbye, I.B.K., Long live Mali” (Maclean, 2020a). By the evening, mutineers had detained President Keïta and Prime Minister Boubou Cissé (Paquette, 2020d). Crowds cheered in the streets, shouting “They have IBK!” (Paquette, 2020e). Revelers were filmed wading in Karim Keïta's pool (Ross, 2020). ECOWAS, the African Union, United Nations, and officials from the United States and France all condemned the uprising and called for Keïta's release (Paquette, 2020e). But the troops took Keïta back to Kati (Ross, 2020). Around midnight, Keïta appeared on state television wearing a surgical mask to announce his resignation, saying “For seven years I have with great joy and happiness tried to put this country back on its feet. If today some people from the armed forces have decided to end it by their intervention, do I have a choice? I should submit to it because I don't want any blood to be shed” (Bell et al., 2020). The hospital union later reported that four people died and 15 people were injured and brought to Bamako's main hospital during the military uprising (Maclean et al., 2020).

Under the constitution, the president of the national assembly was next in line to become interim president upon Keïta's resignation (Thurston, 2020). Instead, on Wednesday, August 19, the coup leaders, identifying themselves as the National Committee for the Salvation of People (CNSP), dissolved the national assembly and announced a national curfew (Bell et al., 2020). The five officers at the CNSP's initial television appearance were all mid-level divisional commanders and deputy commanders. Col. Diaw and Col. Camara were joined by Col. Assimi Goïta, the Autonomous Special Forces Battalion commander in the central region, Maj. Ismaël Wagué, the deputy chief of staff of the air force, and Col. Modibo Koné, a National Guardsman and former commander in Koro. The senior-most military officers and service chiefs did not support the coup and none of the new junta members were Tuareg or Arab from Mali's north (Melly, 2020; Thurston, 2020). In a televised statement, CNSP spokesman Maj. Wagué denounced Keïta's “political clientelism and family management of state affairs” (Ross, 2020). Seeking the support of the M5-RFP and civil society (Devermont, 2020), Wagué said the CNSP was “not keen on power” but sought stability “which will allow us to organize general elections within a reasonable timeframe to allow Mali to equip itself with strong institutions capable of managing as well as possible our daily lives and restore trust between governments and governed” (Bell et al., 2020).

Goïta, who soon emerged as CNSP president, was called the “true force” behind the coup by close associates (Ogunkeye, 2020). On the CNSP, Col. Diaw emerged as first vice president, Col. Sadio Camara as second vice president, and Col. Modibo Koné as third vice president (Diallo, 2020). Prior to the coup, Col. Goïta had been trained in the U.S., having attended a seminar at MacDill Air Force Base in Florida in 2020, and for years had partnered with U.S. Special Operations forces to fight al-Qaeda and other Islamic State militants in Mali. Goïta also received training from other Western allies, including both France and Germany (Paquette, 2020c, 2021a,b). Some see frustration with Keïta's management of defense, given the ineffective state response to the deteriorating security situation, as a catalyst for Goïta and fellow coupmakers (Matei, 2021).

In the wake of the 2020 coup, the African Union suspended Mali's membership (Thurston, 2020). ECOWAS also suspended Mali from its internal decision-making bodies (Ogunkeye, 2020) and moved to impose other sanctions, including shutting down Mali's borders (Richards and Ogugbuaja, 2020). U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called for a restoration of constitutional government and the pentagon suspended aid to Mali's military (Paquette, 2020b,c). Domestic and international pressure was sufficient to gain promises of a political transition back to civilian rule but not to restore Keïta to office. ECOWAS leaders—who parleyed with the CNSP through Diaw—initially insisted on a 1-year transition and a civilian to lead the interim government, but soon said they would accept an 18-month transition (Akorlie, 2020; Maclean, 2020b).

On September 2, General Oumar Diarra was appointed armed forces chief of the general staff, replacing General Abdoulaye Coulibaly, who was detained during the coup (Diallo, 2020). On September 25, after weeks of talks with ECOWAS and a series of dialogues with civil society representatives, the CNSP tapped Ibrahim Bah Ndaw, a retired military officer and former defense minister (in 2014), to serve as interim president (Maclean, 2020b). A few days later, Moctar Ouane, a former diplomat, was appointed prime minister, with four of 25 cabinet positions going to military officers. Two CNSP members gained cabinet posts, with Col. Camara becoming defense minister and Col. Koné becoming security minister. With a nominally civilian government in place (even though real power lay with the junta), ECOWAS lifted its sanctions in October (RFI, 2020).

Assimi Goïta kept a watchful eye over the transition as vice president, even after an interim legislature—the National Transitional Council (CNT)—was set up in December 2020 and Ndaw signed a presidential decree in January 2021 dissolving the CNSP (Diallo, 2021). Formally only responsible for security and defense, in reality Goïta's influence was more far reaching (Diallo, 2021). He had hand-picked CNT members and assented to the ambitious Col. Diaw as CNT head. Goïta had already appointed military officers to 13 of 20 governorships in November, entrenching military power over the state. Tensions between the ex-CNSP and “transitional” government led to a second coup in May 2021 in which Goïta would oust Ndaw, as chronicled below in Section 2.4.

2.2. Niger: March 31, 2021

In February 2021, second round presidential elections were held to determine who would succeed Mahamadou Issoufou, who was set to step down after serving two terms in office. Issoufou himself had come to power in elections held in the wake of a 2010 coup. Mohamed Bazoum, Issoufou's former interior minister and the candidate of the governing party (the Nigerien Party for Democracy and Socialism), won a landmark victory over ex-president Mahamane Ousmane, whose supporters protested and alleged fraud (BBC, 2021d). Despite these post-election protests, international observers from the African Union endorsed the elections as peaceful and democratic. Bazoum's scheduled inauguration on April 2 would thus mark the first transfer of power between democratically elected presidents since Niger's independence from France in 1960 (Balima and Aksar, 2021). In the meantime, jihadist attacks increased. On March 21, Niger suffered its worst terrorist attack in its history, leaving 137 people killed by a coordinated raid by militants on three villages in the Tahoua region near the border with Mali (BBC, 2021b).

Around 3 a.m. on Wednesday, March 31, just two days before Bazoum's inauguration, an armed air force unit from an airbase near the capital's airport reportedly headed west in three heavily armed vehicles and attempted to take over the presidential palace in Niamey. After 30 minutes of heavy gunfire and shelling, the attackers fled the scene and authorities began making arrests. The government spokesperson, Abdourahamane Zakaria, condemned a “cowardly and retrogressive act that aims to endanger democracy and the rule of law to which our country is resolutely committed.” He praised the loyalty and prompt response of the presidential guard and other security forces. Aside from some clashes between pro-Ousmane protestors and police, the situation appeared normal by 10 a.m. (APA, 2021; Balima and Aksar, 2021; BBC, 2021c; Bell et al., 2021a).

Neither the president nor president-elect were captured or harmed and Bazoum's inauguration proceeded as scheduled. At least 15 soldiers were detained for questioning in connection with the apparent coup attempt. Soldiers in custody claimed they had acted on orders of an air force officer, Captain Sani Saley Gouroza (RFI, 2021). Gourouza, the alleged coup leader, was arrested in Benin in late April 2021 (Africa News, 2021). Gouroza's motivations—and with whom he may have conspired—remains shrouded in a mystery as neither he nor the armed assailants have made any public statements or broadcasts. As far as we are aware, there has been no public trial. However, in May 2022, six imprisoned officers were quietly dismissed from Niger's military in connection with the March 2021 coup attempt, including Gourouza, three colonels (Djibo Hamani, Aboubacar Oumarou, and Seydou Mourtala Diori), and two lieutenants (Morou Idrissa and Boubacar Bagouma) (Agence France-Presse, 2022g). The timing of the coup attempt suggests a motive: elements of a government and army long dominated by the western Djerma and Hausa sought to veto the entry to office of an easterner (Diffa Arab) (Harkness, 2022).

As of this writing (in December 2022), Bazoum remains Niger's president. Niger continues to face challenges to democratic consolidation: a history of coups, extreme poverty, low export prices for uranium, insecurity due to jihadist extremism linked to al Qaeda and the Islamic State in the Sahel, and the legacy of the COVID-19 pandemic (Balima and Aksar, 2021). In April 2022, Niger's government arrested Ousmane Cissé, a former interior minister after the 2010 coup and ambassador to Chad since 2016. Cissé was accused of involvement in the March 2021 coup attempt and plotting a coup in March 2022 while Bazoum was in Turkey (Agence France-Presse, 2022g).

2.3. Chad: April 20, 2021

On April 19, 2021, long-time dictator Idriss Déby—who himself had come to power as a rebel leader in 1990 (Debos, 2021)—was killed in action on the front during a battle against Front for Change and Concord in Chad (FACT) rebels north of N'Djamena.7 Fearing a power vacuum that might leave the regime vulnerable and threaten the fight against Islamist extremists in the Sahel, the military moved quickly to prop up Déby's personalist regime (and preserve militarized rule) by installing his 37-year-old son, Mahamat (a four-star military general), as interim president. Thus, on Tuesday, April 20, the military closed the borders, suspended the constitution, dissolved parliament and the government, installed a Transitional Military Council (TMC) led by Mahamat Déby, and promised new elections in 18 months. The military thereby prevented Haroun Kabadi, the president of the national assembly, the next in the presidential line of succession under the 1996 constitution, from taking over as interim president (Adamou et al., 2021; Enonchong, 2021).

A rebel FACT spokesman immediately denounced the coup, saying “Chad is not a monarchy. There cannot be any dynastic devolution of power in our country” (Walsh, 2021a). The domestic opposition also decried the coup. On April 26, the military installed Albert Pahimi Padacke, the runner-up in the 11 April 2021 presidential elections, as interim prime minister. The military repressed anti-coup protests, killing at least nine people. Further demonstrations were banned (Ramadane and McAllister, 2021b). On May 2, the council installed a new “transitional” government with Mahamat Déby as president (Ramadane and McAllister, 2021a).

Though the African Union expressed “grave concern” about the military takeover, in May 2021 the AU chose not to sanction Chad or suspend its membership; though many Anglophone members favored sanctions, Francophone members such as Cameroon and Nigeria, which support N'Djamena in its campaign against Boko Haram in the Lake Chad basin, pushed for leniency (Handy and Djilo, 2021; Olivier, 2021). France, who had for years defended the Déby regime and allied with Déby to fight Islamic insurgents in the Sahel, backed the junta and advocated a “civilian-military” transition. For similar geopolitical reasons, and despite concerns over the regime's human rights abuses, the United States stopped short of condemning the takeover even while calling for a “peaceful and democratic transition” to a civilian government (Adamou et al., 2021; Peltier, 2021).

The TMC initially promised elections for September 2022 (Dizolele, 2022). In October 2021, a National Transition Council was set up as an interim legislature, headed by Haroun Kabadi—the man who had been deposed as president of the national assembly and denied the interim presidency in April 2021 (Nebe, 2021). On October 2, 2022, the transitional government announced that it was delaying democratic elections by 2 years, defying warnings from the AU, the U.S., and other foreign powers (Ramadane, 2022). Amidst anti-TMC anger, a new prime minister was installed in mid-October 2022, Saleh Kebzabo, who claimed a desire to promote national unity and invited FACT to join other rebel groups in transition talks (Salih, 2022).

As of this writing (in December 2022), Mahamat Idriss Déby remains in power as “interim” president. Unlike other recent African coup leaders, Déby was allowed to attend the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit in December 2022. The invitation to Washington was criticized by human rights advocates for prioritizing counter-terrorism concerns over democracy defense (Gramer, 2022). Indeed, there are good reasons to doubt that the current regime is committed to allowing a genuine democratic transition. Pro-democracy protests on October 20, 2022, were violently repressed (Nodjimbadem, 2022). Mahamat Déby is likely to run in any eventual presidential elections.

2.4. Mali: May 24, 2021

Nine months after mid-level officers seized power in the name of the National Committee for the Salvation of People (CNSP; on the 2020 coup, see Section 2.1), fissures between the junta and transitional government surfaced. Civilian disenchantment with the transition process grew. By the spring of 2021, the June 5 movement (M5-RFP), having initially supported the CNSP but increasingly sidelined, thus moved into opposition to the interim government, decrying “continuity of the old regime” and lack of civilianization. Amidst rumors of an elite split, a source close to the ex-CNSP chief tried to assuage concerns, noting that “Assimi Goïta sees Bah N'Daw as an uncle. He spent his entire childhood with him” (Diallo, 2021).

On Monday, May 24, 2021, the interim president, Bah Ndaw, and prime minister, Moctar Ouane, announced a cabinet reshuffle that dropped two key ex-CNSP members, removing Col. Sadio Camara as defense minister and Col. Modibo Koné as security minister (Lorgerie and Felix, 2021; Paquette, 2021d). The move could be seen as a bid to enhance the power of civilians in the transitional government, and thus advance Ouane's reform agenda that the military had blocked for months (International Crisis Group, 2021). Within hours, soldiers arrested Ouane and Ndaw, who were then detained at a military base outside of the capital (Diallo et al., 2021b).

On Tuesday, May 25, 2021, interim Vice President Goïta announced that he had ousted Ndaw and Ouane for failing to consult him on the cabinet shakeup (Bell et al., 2021b), which he argued violated the country's transition agreement. Goïta also accused the former transitional government of mishandling social tensions. On Wednesday, May 26, Bah Ndaw and Ouane's resignations were announced and Goïta promised that the elections planned for 2022 would still occur. The U.N. Security Council called for a safe, immediate, and unconditional release of the two detained leaders. France, the European Union, and the U.S. all threatened to impose targeted sanctions in response to what French President Emanuel Macron referred to as Goïta's “coup within a coup.” Additionally, an ECOWAS delegation visiting the country urged the military to back down and raised the possibility of sanctioning the coup makers (Diallo et al., 2021b). On May 27, thanks to international pressures, Ndaw and Ouane were released from military custody (Paquette, 2021c).

In early June 2021, Goïta was sworn in as interim president (Reuters, 2021a). Choguel Maiga, the M5-RFP spokesman, was tapped to serve as prime minister (International Crisis Group, 2021). Soon after, Col. Camara was restored as defense minister (Lorgerie and Felix, 2021). Around the same time, despite the deteriorating security situation in Mali, with insurgent attacks reportedly increasing by 30 percent since the 2020 coup (De Bruin and Dwyer, 2022), French President Emmanuel Macron—having already suspended joint operations with the Malian military—announced that France would wind down Operation Barkhane, under which over 5,000 French troops since 2014 had aided the fight against extremism in West Africa (Noack and Paquette, 2021). Some feared that France's drawdown, cutting its forces by half over a year, would hearten extremists loyal to al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (Paquette and Noack, 2021).

In November 2021, ECOWAS imposed sanctions after Goïta's government delayed elections scheduled for February 2022 under the September 2020 transition agreement (Reuters, 2021b). ECOWAS imposed even stricter sanctions after the military announced in January 2022 that elections might not be held until 2026 (Africa Business, 2022). ECOWAS made lifting sanctions conditional on restoring a quicker timeline for a return to civilian rule. Following negotiations with ECOWAS, in June 2022 Goïta's government adopted a 24-month transition plan from March 2022, with a referendum for a new constitution set for March 2023 followed by local elections in June 2023, legislative elections in fall 2023, and presidential elections in February 2024 (Kontao et al., 2021; Africanews, 2022c). In response, ECOWAS lifted sanctions (Risemberg, 2022).

As of this writing (in December 2022), Goïta's junta remains in power and Mali is governed by a “transitional government.” On October 12, 2022, the constitutional commission set up in June 2022 delivered a new draft constitution to Goïta (Africanews, 2022b). Whether or not Mali's military masters relinquish power to civilians on time (or any time soon) remains to be seen.

2.5. Guinea: September 5, 2021

Alpha Condé was democratically elected in 2010 (in the wake of a 2008 coup), marking the country's first democratic election since gaining its independence from France in 1958. But during his second term, Condé changed Guinea's constitution to allow himself to stay in power longer than two terms. In October 2020, Condé won a third term, defeating opposition leader Cellou Delein in a flawed election marked by violence and border closures that prevented people living abroad from casting votes (Bah and Paquette, 2021; Diallo et al., 2021a). After the election, protests broke out and more than 400 of Condé's political opponents were sent to prison (Walsh and Schmitt, 2021). These autocratizing moves undermined the government's legitimacy (Allegrozzi, 2020).

Early on Sunday, September 5, 2021, a Guinean special forces unit took a break from a months-long training program with U.S. Green Berets in Forécariah (Walsh and Schmitt, 2021). They drove several hours to the capital of Conakry, stormed the presidential palace, detained President Condé, and fired gunshots to prevent people from leaving their homes. Soon after, the 41-year-old head of Guinea's special forces, Col. Mamady Doumbouya, announced on state television that the constitution was suspended and government institutions dissolved. Doumbouya said that “the Guinean personalisation of political life is over. We will no longer entrust politics to one man, we will entrust it to the people” (BBC, 2021a; Diallo et al., 2021a). He accused Condé of “the trampling of citizens' rights, the disrespect for democratic principles, the outrageous politicization of public administration, financial mismanagement,” and endemic corruption (Paquette and Timsit, 2021).

Before the coup, Doumbouya—a former French Foreign Legionnaire and Condé ally—had kept a low profile. Like Condé, he was an ethnic Malinké from Guinea's eastern Kankan region (BBC, 2021a). Like Assimi Goïta, who led the 2020 and 2021 coups in Mali, Doumbouya had received training from the U.S. military.8 Doumbouya became the head of a new junta, the National Committee of Reconciliation and Development (CNRD), and was sworn in as interim president on October 1. Doubouya quoted the late Jerry Rawlings—the charismatic Ghanaian coup leader who ruled Ghana from 1981 until 2001—saying: “If the people are crushed by their elites, it is up to the army to give the people their freedom” (BBC, 2021a). Domestic reception of the coup was initially mixed or ambivalent (Diallo et al., 2021a). There were no immediate anti-coup protests. Rather, some crowds shouted Doumbouya's name, seeing the coup as an opportunity for renewal.

The international community—including the European Union's chief diplomat, the French foreign ministry, and the U.S. State Department and Defense Department—condemned the coup. ECOWAS and the AU suspended Guinea's membership (BBC, 2021a). Less than two weeks after the coup, ECOWAS imposed sanctions—a travel ban and bank freeze for junta members and their families—and called on the junta to release Condé from detention and hold elections within six months to restore civilian rule (AFP et al., 2021). In October 2021, the junta tapped a Mohamed Beavogui, a long-time international civil servant, as interim prime minister (Associated Press, 2021). As in Mali after the 2020 coup, the junta installed an interim legislature—the National Transitional Council (CNT)—that began to meet in February 2022 (Agence France-Presse, 2022e). However, the junta continued to refuse to commit to a transition timetable. Alpha Condé was only released from prison in November 2021 and house arrest in April 2022 (Samb, 2022a).

In May 2022, under the threat of sanctions, the junta belatedly announced a 39-month transition period for the return of constitutional civilian rule, a much longer transition than ECOWAS had demanded. Doumbouya promised that no one in the interim government, including himself, would stand in the promised elections (BBC, 2022b). Soon after, however, the junta banned political protest (Agence France-Presse, 2022g). The ban did not deter protesters, however, who grew frustrated with the lack of dialogue over the transition process. The National Front for the Defense of the Constitution (FNDC)—a coalition of civil society groups pushing for a return to civilian rule—began organizing mass protests since July 2022 (Agence France-Presse, 2022b; Samb, 2022b).

In September 2022, responding to the junta's refusal to set a quicker date for elections, ECOWAS agreed to gradually impose more sanctions on junta members (Agence France-Presse, 2022h). The U.S. expressed support for ECOWAS sanctions (Price, 2022). The junta violently repressed anti-government protests demanding a return to civilian rule in October (Reuters, 2022), but soon after the junta agreed to a shortened 2-year timeline for a return to civilian rule in a bid to avoid sanctions (Agence France-Presse, 2022f). As of this writing (in December 2022), Doumbouya remains in power and whether promises to restore civilian rule are kept remain to be seen.

2.6. Sudan: September 21, 2021

After a wave of mass protest and security force defections, long-time dictator Omar Bashir—who had been in power since coming to a coup himself in 1989—was ousted in a regime change coup in April 2019 that brought to power a Transitional Military Council (TMC) led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. Yet protests continued as the opposition demanded that a civilian government be installed. Days earlier, the TMC and the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) alliance agreed to a power-sharing deal to create a joint 11-member sovereignty council with six civilians and five military officers to rule for 39-months while new democratic elections were organized. In August 2019, the sovereignty council appointed Abdalla Hamdok, a civilian diplomat, as prime minister. Under Sudan's 2019 constitution, the military was to be in charge of the Sovereignty Council for the first 21 months of the 39-month transition, then a civilian selected by the FFC from May 17, 2021.9 By September 2021, however, the transition to civilian leadership had still not occurred, and Burhan (and thus the military) remained in command (Eltahir and Abdelaziz, 2021).

On September 21, 2021, Sudanese authorities claimed they stopped a coup attempt against the transitional government.10 Rebel troops tried to seize the military headquarters and state broadcaster in Omdurman and successfully took over several government institutions. Security forces blocked the bridge linking Khartoum and Omdurman, and demonstrators in Port Sudan and other nearby areas protested against the coup (Beaumont, 2021). The military managed to take back the governmental buildings from the rebels and arrested more than 30 troops, including high-ranking officers. Omar Bashir was also arrested, and the Sudanese government stated that it would hand over Bashir to the International Criminal Court (Agence France-Presse, 2021).

The government blamed the coup attempt on 22 army officers and civilians loyal to Bashir and identified their leader as Major General Abdalbagi Alhassan Othman Bakrawi, the commander of the Armored Corps (Mirghani and Abdelaziz, 2021). The implication is that the coup makers sought to take advantage of a period of heightened political tension—and grievances over the delayed transition to civilian leadership—to attempt to put Bashir back in power and potentially gain the support of civilians. We were not able to discover the fate of the alleged coupmakers or any evidence of a public trial. However, conflict between the military and civilians over control of the transitional government lead to a coup the following month, as chronicled in Section 2.7.

2.7. Sudan: October 25, 2021

Little more than a month after an apparent failed coup attempt by Bashir loyalists (see Section 2.6), a successful coup was launched from within the Sovereignty Council itself. On October 16, pro-military demonstrators marched in Khartoum shouting slogans like “One army, one people” and demanding that the military stage a coup. The protest was reportedly financed by a minority civilian faction on the Sovereignty Council—led by former rebels and known as the Charter of the National Accord—that sought to replace the Hamdok's majority FFC faction with more pro-military civilians in the transitional government. Thousands of counter-protesters in Khartoum on October 21 demanded a fully civilian government (Hammou, 2021).

On October 25, 2021, Lt. Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan—Sudan's top military commander and head of state—dissolved the government and Sovereignty Council, declared a state of emergency, and arrested Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and a majority of Hamdok's cabinet (Nichols, 2021; Salih and Beaumont, 2021). Burhan justified his move against the civilian faction of the provisional government with the need for a “competent” government and to prevent further infighting between the military and civilians until new elections were held in 2023 (Benoist, 2021). Though some elements (including former Bashir loyalists) expressed support for the coup, tens of thousands of civilians took to the streets to protest in Khartoum, Omdurman, and other cities. At least seven people were killed, and 140 civilians were injured (Nichols, 2021).

The international community—including the United States, European Union, and Arab League—largely condemned the coup. The African Union suspended Sudan's membership and the U.S. withdrew $700 million of aid (Alhenawi, 2021; Mackintosh, 2021). The World Bank and International Monetary Fund also suspended aid and debt relief pending a return to civilian rule (MEE Staff, 2022). Following civil resistance to the coup and weeks of negotiations, in November 2021 Gen. al-Burhan agreed to a 14-point deal restoring Hamdock as prime minister, promising him freedom in forming his cabinet, and releasing all political prisoners (Reuters et al., 2021). However, the Umma Party and some members of the FFC rejected the deal. Thousands of civilians continued to protest, calling for the coupmakers' prosecution and accusing Hamdok of providing cover for continuing military domination (BBC, 2021e). The U.S. sanctioned Sudan in March 2022 in response to Sudanese police's severe repression of peaceful protesters (News Agencies, 2022b).

If Sudanese protesters had succeeded in forcing a power-sharing deal in August 2019 that put Sudan on track for a “pacted transition” (Grewal, 2021), then the October 2021 coup by Burhan represents a “veto coup” by which Burhan and the military have sought to maintain their power and block the negotiated transition to civilian rule, a process which has stalled over the last year despite continuing anti-coup protests (Hudson, 2022). In this struggle, Sudan's military has drawn support from the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, all with an interest in blunting democratization in the Arab world (Siegle, 2021). Russia, too, has cozied up to Sudan's post-coup junta, hoping to secure naval access to Port Sudan. The Wagner Group has also reportedly been active in gold smuggling in western Sudan (MEE Staff, 2022).

In January 2022, Hamdok resigned as prime minister after continued protests and mediation attempts with the military failed (Dahir, 2022). Burhan installed a caretaker government headed by Osman Hussein as acting prime minister (ST, 2022b). In July 2022, Burhan broke off internationally-mediated talks with civilian forces and claimed the military would let civilians form a government but that the military would retain control over defense matters through a supreme council of the armed forces. Many observers were rightfully skeptical, as pro-democracy forces such as the FFC had boycotted the talks given the involvement of civilians associated with the former Bashir regime in the transitional government (Hammou, 2022). Burhan sacked civilian members of the Sovereignty Council in preparation for the transition, but then the military and civilian forces remained deadlocked for the next two months (Boswell, 2022).

In September 2022, military leaders agreed in principle to allow civilian forces to name the next prime minister (Reuters, 2022). The United States brokered secret talks between the military and FFC to restore a civilian prime minister while guaranteeing the military some autonomy (Marks and Alamin, 2022). On December 5, 2022, a “framework agreement was announced under which a civilian transitional government would be restored and prepare elections to be held in 24 months. Though praised internationally, domestic critics pointed to the deal as legitimizing Burhan's political power (ST, 2022a). As of this writing (in December 2022), it remains to be seen whether the framework agreement will be carried out or the military will actually relinquish power. Many seasoned observers are pessimistic about military withdrawal (Ali et al., 2022). Speaking at an army training event in mid-December, Burhan made clear that no final settlement had been reached and reassured troops that the military would not accept a deal that undermined the country's “constants” (MEM Staff, 2022). For now, Sudan remains under military rule.

2.8. Burkina Faso: January 24, 2022

By January 2022, grievances within the armed forces, and tension between the military and the democratically-elected government of Roch Kaboré, had been building for months (Martin and Lebovich, 2022). The military—spread thin—had struggled for years to contain Islamist militants in the country, all while being blamed for many civilian casualties and suffering a significant number of losses itself. In November 2021, militants killed 49 gendarmes and four civilians at a camp in Inata, marking the country's largest loss of security forces to date (Dwyer, 2022). Anti-government protests called for Kaboré to step down following reports that the troops had been without food for two weeks prior to this attack. To shore up his support in the military, Kaboré reshuffled the senior military ranks. In early December 2021, Lt. Col. Paul-Henri Damiba, a 41-year-old counter-terrorism commander in the north, was promoted to be the commander of the important third military region covering the capital (Al Jazeera and News Agencies, 2022). A leading military figure, Damiba had been a member of Blaise Compaoré's presidential guard (RSP) until 2011 but joined loyalist forces opposing a 2015 coup attempt by RSP elements (Engels, 2022a, p. 317).

On Sunday, January 23, 2022, soldiers mutinied. Their list of demands included a call for more support, troops, and training for the fight against terrorism in the country, changes to deployment processes, increased support for families who had lost their relatives in conflict, improved assistance for injured soldiers, and for the replacement of intelligence and military chiefs, for the government. Heavy gunfire soon engulfed the capital of Burkina Events soon overtook government assurances of being in full control (Ndiaga and Mimault, 2022a; Walsh, 2022).

On the evening of Monday, January 24, soldiers detained Kaboré, dissolved the government and national assembly, suspended the constitution, and closed the country's borders. Kaboré, the coup makers announced, was unfit to lead the country in the face of new challenges, including the rise of the jihadist insurgency that had taken the lives of thousands of people and displaced over one million people (Munshi, 2022a). The army needed to intervene to restore the country's “territorial integrity” and “sovereignty.” Kaboré hand wrote a letter of resignation (Engels, 2022a, p. 315). Many people welcomed the coup given frustration with the worsening security and humanitarian crisis (Mimault and Ndiaga, 2022a). Although the trade union alliance condemned the coup on January 26, trade unions did not mobilize anti-coup protests as they had in 2015 (Engels, 2022b).

Damiba emerged as head of the new junta, the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration (MPSR). ECOWAS suspended Burkina Faso's membership. After two weeks, the national curfew was removed. In February 2022, the MPSR installed a 15-person commission—including representatives of civil society—to advise a transition process. On March 1, Damiba agreed to initiate a 36-month transition period back to constitutional civilian rule and not to stand as a candidate in the elections. The first and principal aim of the transition charter was the “fight against terrorism.” On March 3, Dambiba appointed Albert Ouédraogo—a civilian and close friend of Damiba's uncle—as interim prime minister. The interim cabinet installed on March 5 including some pre-coup members, notably the minister of defense Barthélemy Simporé (Engels, 2022a, 316, Engels, 2022b). In July 2022, the junta proposed—and ECOWAS accepted—a “two-year” transition timeline proposal under which there would be a constitutional referendum in December 2024 and legislative and presidential elections in February 2025 (RFI, 2022). However, Damiba himself would be ousted just a few months later, as chronicled below in Section 2.10.

2.9. Guinea Bissau: February 1, 2022

On Tuesday afternoon, February 1, 2022, continuous gunfire was heard around government buildings in which President Umaro Sissoco Embaló and his prime minister Nuno Gomes Nabiam were holding a cabinet meeting. Armed assailants tried to enter the compound just after the cabinet met but were repelled. According to military sources and local media in the West African country, the exchange of fire lasted for five hours and eleven people—mostly loyal government forces—died in a failed attempt to overthrow the democratically-elected government of Guinea Bissau. ECOWAS and the AU condemned the attack. On Wednesday, calm returned, public transportation resumed, and businesses reopened (EFE, 2022; Munshi, 2022c; News Wires, 2022; Paquette, 2022). On February 3, ECOWAS voted to deploy troops to stabilize the country, as it had done from 2012 to 2020 following a prior coup (Dabo and Peyton, 2022b).

President Embaló quickly linked the coup attempt to men connected to drug trafficking who opposed his war on drugs and corruption (Munshi, 2022b). Since the 2000s, Guinea Bissau—“Africa's first narco-state”—had served as a key transit point of drugs (especially cocaine) headed from Latin America to the U.S. and Europe, to the great consternation of the United States and United Nations, among others. The drug trade had indeed long been implicated in the struggle for power and wealth in Guinea Bissau's government and armed forces (BBC, 2022a; EFE, 2022), with the Balanta-dominated military having deep ties to drug traffickers (Harkness, 2022). On February 10, Embaló said that former navy chief Admiral Jose Americo Bubo Na Tchuto and his aides Tchamy Yala and Papis Djeme had masterminded the failed coup and were among those arrested. The three men had been arrested in an undercover DEA sting operation in 2013, served multi-year sentences, and had since been released and returned to Guinea Bissau. Embaló said that he had seen Yala and Djeme at the government palace during the attack (News Agencies, 2022a).11

However, some questioning how the president could survive a bloody firefight for five hours—believed that the coup may have been staged, or may have been the result of tensions with Prime Minister Nabian, a close ally to the military (Munshi, 2022b). Some observers feared that Embaló would use the coup attempt as cover to purge political elites and to root out remaining opposition and plots (Woldense, 2022). On May 16, Embaló dissolved the opposition-controlled parliament, citing parliamentary corruption and irreconcilable differences (Milo, 2022). Over 600 ECOWAS troops deployed in June to deter military intervention in the country (Dabo and Peyton, 2022a).

As of this writing (in December 2022), we are aware of no completed investigation, trials of the alleged coupmakers, or subsequent unrest. The extent of military involvement remains unclear (King, 2022). Some witnesses claimed the military was involved, whereas others and Embaló himself dismissed or downplayed military involvement (if the military was not involved, this event would not constitute a bonafide coup attempt). Snap legislative elections, scheduled for December 2022, have been constitutionally postponed to 2023 (Milo, 2022). Meanwhile, Guinea Bissau has called on ECOWAS to form a rapid reaction force to fight coups and combat terrorism (Vieira, 2022).

2.10. Burkina Faso: September 30, 2022

Little more than eight months after the military (MPSR led by Lt. Col. Damiba) seized power (see Section 2.8), Burkina Faso suffered a “coup within a coup” (MacDougall, 2022). Lt. Col. Damiba had justified his January 2022 coup on the need to defeat Islamic extremists, but public support for the junta waned as the violence continued to worsen under Damiba. Despite setting up a National Operations Command, Burkina Faso suffered some 620 terrorist attacks killing 567 people during Damiba's first 100 days in power (Heywood et al., 2022). By September 2022, the country only controlled about 60 percent of its territory (Booty, 2022a; Mednick and Kabore, 2022). Hundreds of thousands of more people had been displaced since the January 2022, bringing the total to upwards of two million people. The Group to Support Islam and Muslims (JNIM) and the Islamic State Sahel Province (IS Sahel) were active in 10 of Burkina's 13 regions and had begun to blockade major cities, leading to some food shortages. On September 13, President Damiba sacked Barthélemy Simporé and took over as defense minister himself (International Crisis Group, 2022; Ndiaga and Mimault, 2022c). Then, on Monday, September 26, an attack in Gaskinde in Soum province of the Sahel destroyed a dozen trucks of a 150-truck convoy taking supplies to the besieged town of Djibo, leaving at least 27 soldiers and 10 civilians dead and 50 civilians missing (MacDougall, 2022; Mimault and Ndiaga, 2022b). This attack, as it were, was the last straw.12

On the morning of Friday, September 30, 2022, gunfire rang in the capital of Ouagadougou. Mutinous soldiers blocked roads near the presidential palace (where there was an explosion) and the state television broadcaster RTB briefly went off the air (Maclean, 2022; Ndiaga and Mimault, 2022b). That afternoon, some street protesters called for Damiba's ouster (Booty, 2022a). In the evening, soldiers led by Captain Ibrahim Traoré—a 34-year old officer who had fought Islamist insurgents in Mali and in Burkina Faso (Rakotomalala and Chothia, 2022)—announced on state television that Damiba had been ousted as MPSR head and that they had closed the country's borders, dissolved the interim government and national assembly, and issued a curfew. Capt. Kiswendsida Farouk Azaria Sorgho, a spokesman for the coupmakers, cited the “the continually worsening security situation” and said that military officers and junior officers had acted to protect the country's “security and integrity” (Maclean and Peltier, 2022; Mednick and Kabore, 2022). Damiba said “our people have suffered enough, and are still suffering” (Booty, 2022a). Traoré explained that Damiba had ignored his advice and that of other soldiers. “Soldiers have been dying like flies, but [their commanders] never change their methods,” Traoré said (MacDougall, 2022).

By Saturday, October 1, although the coupmakers on Friday had promised to respect international commitments and “adopt a new transitional constitution charter and to select a new Burkina Faso president be it civilian or military” (Mednick and Kabore, 2022), ECOWAS condemned the coup as “inappropriate” while the country was trying to restore civilian rule; the AU demanded the return of constitutional order by July 2023. The coupmakers released a second statement read on behalf of Capt. Traoré's camp accusing Damiba—whose whereabouts remained unknown—of planning a counter-attack because they were willing to work with new partners—widely believed to be a reference to Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group—in the fight against Islamists (Booty, 2022a; Kabore and Mednick, 2022). A junta member, speaking anonymously, later disclosed that Damiba had rejected the urging of Traoré and others that he work with more partners, especially Russia (Mednick, 2022). Echoing rumors spread on social media, Capt. Traoré accused the French army of harboring Damiba at one of their bases at Kamboinsin (Booty, 2022a). Despite France's denial, protests commenced outside of the French embassy and other French-related sites, leading to significant property damage after the embassy was set on fire (Associated Press, 2022a).

By Sunday, October 2, after mediation with religious and community leaders, Lt. Col. Damiba agreed to resign after Capt. Traoré agreed to his conditions, which included an agreement to respect commitments made to ECOWAS to hold an election by the year 2024. Captain Traoré took over as the new head of state, and Damiba released a recording that was widely shared on social media wishing his successor success (Associated Press, 2022a; Booty, 2022b). On Monday, October 3, Togo's government confirmed that Lt. Col. Damiba had fled the capital and sought refuge in Togo (Booty, 2022b). The relatively cordial hand off of power, and absence of moves to purge the rest of the MPSR, suggest that the coup was not revolutionary but sought simply to reshuffle the leadership of the junta. Following an emergency meeting with ECOWAS on October 4, Traoré committed to respecting international commitments and the transition timetable for elections by 2024 (MacDougall, 2022). On Wednesday, October 5, Traoré was officially declared president. Some pro-coup protesters that week were seen waving Russian flags (Jones, 2022).

On October 5, 2022 an ECOWAS began a “fact-finding” mission in Burkina Faso regarding the coup, but were met by dozens of pro-coup demonstrators calling ECOWAS a disgrace, chanting pro-Russian slogans, and urging France to exit the country (Africanews, 2022a). Although the coup had reshuffling motives, the coup does entail a shift in the balance of power within the military. Whereas Damiba and others military elite are graduates of the prestigious Kadiogo Military Academy, Traoré had graduated from a second-tier institution, the Georges Namonao Military School (France 24 and AFP, 2022). Meanwhile, fears abound that Burkina Faso—following Mali's playbook—may empower the Wagner Group in the country (Heywood et al., 2022; Mednick, 2022). Meanwhile, as of this writing, Burkina's military and civilian leaders continue to negotiate over the terms and timeline for a return to democratic rule (Breslawski and Fleishman, 2022).

2.11. São Tomé and Príncipe: November 25, 2022

On Friday, November 25, 2022, officials in São Tomé and Príncipe reported that security forces had thwarted a coup attempt early that morning, the first coup attempt in the West African island nation since 2003. At a press briefing aired by Radio Somos Todos Primos, Prime Minister Patrice Trovoada said that the coup began at 12:40 a.m. Four citizens—ex-soldiers or mercenaries—entered army headquarters with the presumed support of troops on the inside. The men were searching for weapons, which the conspirators purportedly sought to deliver to accomplices parked in a van outside the facility. Fearing a coup, authorities deployed troops to secure the homes of the president and cabinet members and to re-secure the base. A local resident told international journalists that they heard automatic and heavy weapons fire and explosions for two hours coming from inside the army headquarters. During the fighting, perpetrators took the officer of the day (a lieutenant) hostage, who was lightly injured. By 6 a.m., the four principal infiltrators had been “neutralized” and calm had been restored. At least three active-duty corporals were arrested. Some of the men waiting in the van nearby reportedly fled the scene (Agence France-Presse, 2022d; Associated Press, 2022b; Bonny, 2022; Christensen, 2022; Fabricius, 2022; Lusa, 2022; Nkurunziza, 2022).

If this event was a genuine coup attempt, who was behind it, and how the perpetrators died is disputed and still under official investigation. Authorities interpreted the attack on the base as the opening gambit in a planned coup (Fabricius, 2022). Four perpetrators at the base were detained (Christensen, 2022; Yusuf, 2022). Under interrogation, these men reportedly implicated two alleged ringleaders. One was Arlécio Costa, a former Santomean officer of the so-called “Buffalo Battalion”—a notorious South African mercenary unit active during the late Cold War but disbanded by Pretoria in 1993 (Fabricius, 2022). Costa was a leader of the 2003 coup attempt and had been detained in 2009 in connection with another coup conspiracy (Pinho, 2009). The other alleged ringleader was Delfim Neves, the former president of the outgoing national assembly (until November 11) and still deputy of the Democratic Convergence Party. Neves ran on behalf of the Basta movement that had finished third in the September 2022 parliamentary elections (All Africa, 2022; Yusuf, 2022). Neves had unsuccessfully run for president in July 2021, and alleged fraud after he was eliminated in the first round. He had allegedly tried to use his position in parliament to delay second round voting and be installed interim president (Powell and Oldershaw, 2022).

Costa and Neves were rounded up for questioning. Of those detained in connection with the base infiltration, by November 26 four were dead, including three of the four original perpetrators and Costa (Bonny, 2022). The military said that the three perpetrators had died of injuries sustained during the firefight after they had been taken to the hospital. Costa allegedly died after he “jumped from a vehicle” (Agence France-Presse, 2022a). However, images of suspects being tied up spread on social media and led to allegations from the largest opposition party, the center-left Movement for the Liberation of São Tomé and Príncipe (MLSTP), that the suspects had been tortured and murdered (BBC, 2022c). In response, judicial authorities launched two investigations into the causes of the alleged coup attempt and into how the detainees died (Agence France-Presse, 2022a). They requested assistance from Portugal, which quickly deployed a team of investigators and police experts to aid the investigations (Euronews and AFP, 2022).

On Sunday, November 27, Trovoada said that the alleged coup attempt had involved four civilians, 12 active-duty soldiers, and some veterans of the Buffalo Battalion (Agence France-Presse, 2022a). Prime Minister Trovoada, who had only come back to office two weeks earlier after his center-right Independent Democratic Action (ADI) party won parliamentary elections, had earlier said that “certain individuals do not conform to the will of the ballot box and the will of the sovereign people, and thus tarnish the country” (Associated Press, 2022b). The heads of the African Union and ECOWAS both condemned the coup attempt (Yusuf, 2022). Joao Lourenço, as acting chairman of the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries, called for calm in the country (All Africa, 2022). Neves was released on bail on Tuesday, November 29. Neves denied any involvement and the former prime minister accused the Trovoada government of staging the coup to eliminate political rivals (Agence France-Presse, 2022c). Soon after, former prime minister and MLSTP leader Jorge Bom Jesus dismissed the attack on barracks as involving “miscreants” and dismissed the alleged coup attempt as an “invention” by an increasingly autocratic government to justify an opposition crackdown (Fernando, 2022). As of this writing (in December 2022), the European Union has called for transparency in the ongoing investigations so the facts are revealed.

3. Discussion

Having reviewed the history of coups in Africa over the two plus year-period from August 2020 to November 2022, what lessons may follow about their causes and consequences?

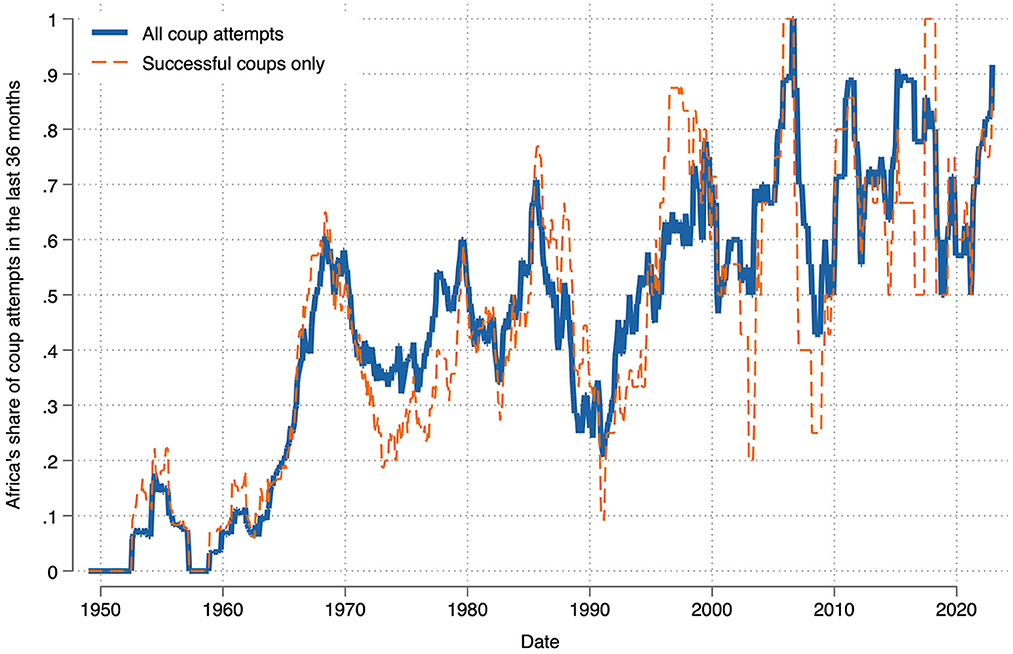

To start, we must ask: why has there been an uptick in coups—what U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres called an “epidemic of coups d'état” in October 2021 (Nichols, 2021)—in the last few “COVID pandemic” years, and why have all but one occurred in Africa? As seen in Figure 3, Africa has now become the global epicenter of coups. During the Cold War years from 1958 to 1989, when coups were much more common in other world regions, Africa accounted for 36 percent of all coup attempts (127 of 355) and successful coups (66 of 183) worldwide. This figure has only increased over the last three decades. Africa accounted for 55 percent of all coup attempts (45 of 82) and 53 percent of successful coups (17 of 32) from 1990 to 2001. From 2002 to 2019, Africa accounted for 69 percent of all coup attempts (36 of 52) and 63 percent of all successful coups (17 of 27). From 2020 through (December) 2022, by contrast, and despite the fact that Africa only accounts for about 27 percent of all countries in the world, countries in Africa have accounted for 92 percent of all coup attempts (11 of 12) and 88 percent of successful coups (7 of 8) worldwide. Until 1999, Africa had never accounted for 80 percent or more of annual global coup attempts. Since 2000, this threshold has been met or exceeded in over half of all years (12 of 22). Since 2010, Africa had accounted all coup attempts in six of 12 years, including 2020 and 2022.13

First, was there evidence of “contagion” or coupmakers being inspired by recent coups in region, or were the causes nearly exclusively domestic? Although scholars have long argued that coups often “diffuse” across borders and thus cluster in space and time, the extreme bounds analysis by Miller et al. (2018) casts doubt on the “coup contagion” hypothesis in general, and Faulkner et al. (2022) and Singh (2022) have questioned this explanation for recent coups in Africa in particular. Indeed, given the lack of a “smoking gun,” it is difficult to establish that direct diffusion—either through learning or changing the cost-benefit calculus of coupmakers—was a key cause for any given coup. The evidence of coup contagion is circumstantial. For example, Lt. Col. Damiba—the leader of the January 2022 coup in Burkina Faso—studied at the Ecole militaire in Paris together with Mamady Doumbouya, the leader of the September 2021 coup in Guinea (Engels, 2022a, p. 317). Although we are not aware of direct communication between them in advance, their personal connection makes it plausible that Damiba drew inspiration from his former classmate.

Second, can we blame the decline of anti-coup norms globally in recent years? The jury is still out. It is generally accepted that the international community's reactions to coups—even if they cannot “reverse” coups in the short-run (Powell and Hammou, 2022)—can influence how long post-coup regimes survive (Thyne et al., 2018). On the one hand, according to De Bruin and Dwyer (2022), the AU continues to consistently uphold anti-coup norms, having “suspended nearly all government that experienced coups since 2003 and imposed sanctions 73 percent of the time.” The decision not to suspend Chad after the 2021 coup was the exception that proved the rule. On the other hand, many observers see a weakening of “anti-coup” norms in recent years (Tansey, 2017, 2018). ECOWAS has had more uneven application of anti-coup norms since 2014 (Balogun and Glas, 2021). Meanwhile, coupmakers in Egypt (2013) and Zimbabwe (2017) were able to retain power via elections. To the extent coup plotters increasingly believe they can get away with it, “learning” processes may have empowered previously deterrable plotters to act (Powell and Hammou, 2022). Contemporaneous evidence of such learning from changes in the international environment—and insight into coupmakers' cost-benefit calculations—is difficult to observe. What's more, Thailand (2014) and Myanmar (2021) have similarly demonstrated that it is possible for military coupmakers to entrench themselves, yet we have not seen the same resurgence of coups in Asia, despite relatively weaker anti-coup norms in regional bodies like ASEAN.

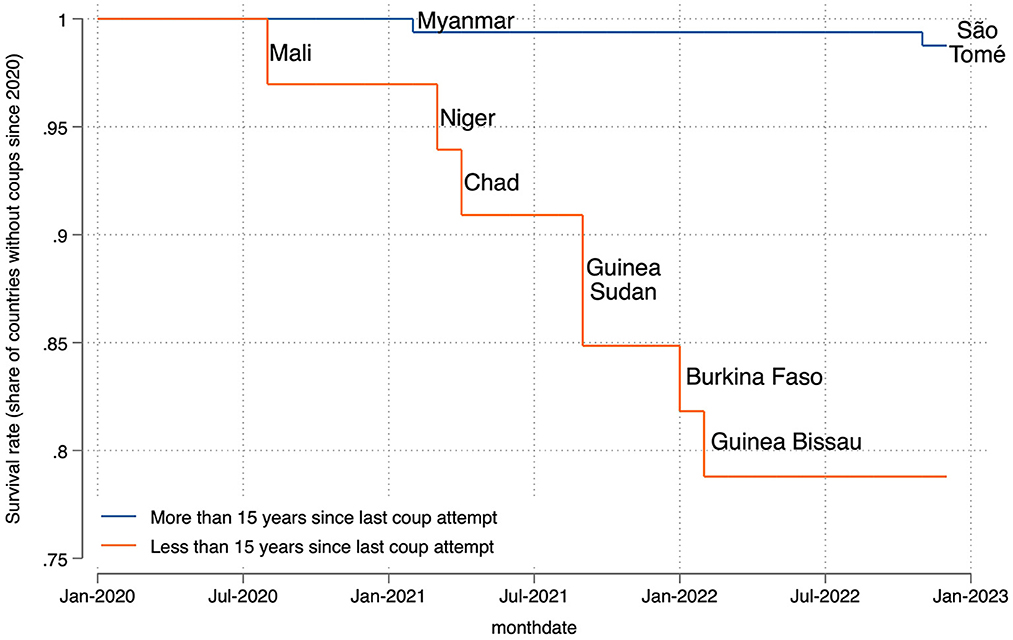

What about the domestic drivers of the recent coups? We briefly review five major potential causes discussed in the literature. The first, as noted persuasively by Singh (2022, p. 78), is “the coup trap.” Countries with a more recent history of coups are at a higher risk of coups, and the same is true of the most recent wave of coups. The average country in Africa that avoided a coup attempt from 2020 to 2022 had not had a coup for 27 years. By contrast, the average country that did suffer coups in this period had a coup attempt only seven years previously. Among the eight African countries with coups since 2020, most had coups recently, occurring in Sudan in 2019, Burkina Faso in 2015, Guinea Bissau and Mali in 2012, Niger in 2010, Guinea in 2008, Chad in 2006, and in 2003. Figure 4 compares the survival rates (share of countries avoiding coups between 2020 and October 2022) of the 33 countries with a more recent history of coups at the onset of 2020 (less than 15 years since last coup attempt) versus the 162 countries with no recent coups. Whereas countries with no coup history were mostly immune to coups (with Myanmar and São Tomé and Príncipe the exceptions that prove the rule), more than one in five countries (7 of 33) with coup attempts in the last 15 years suffered coup recidivism from 2020 to 2022.14

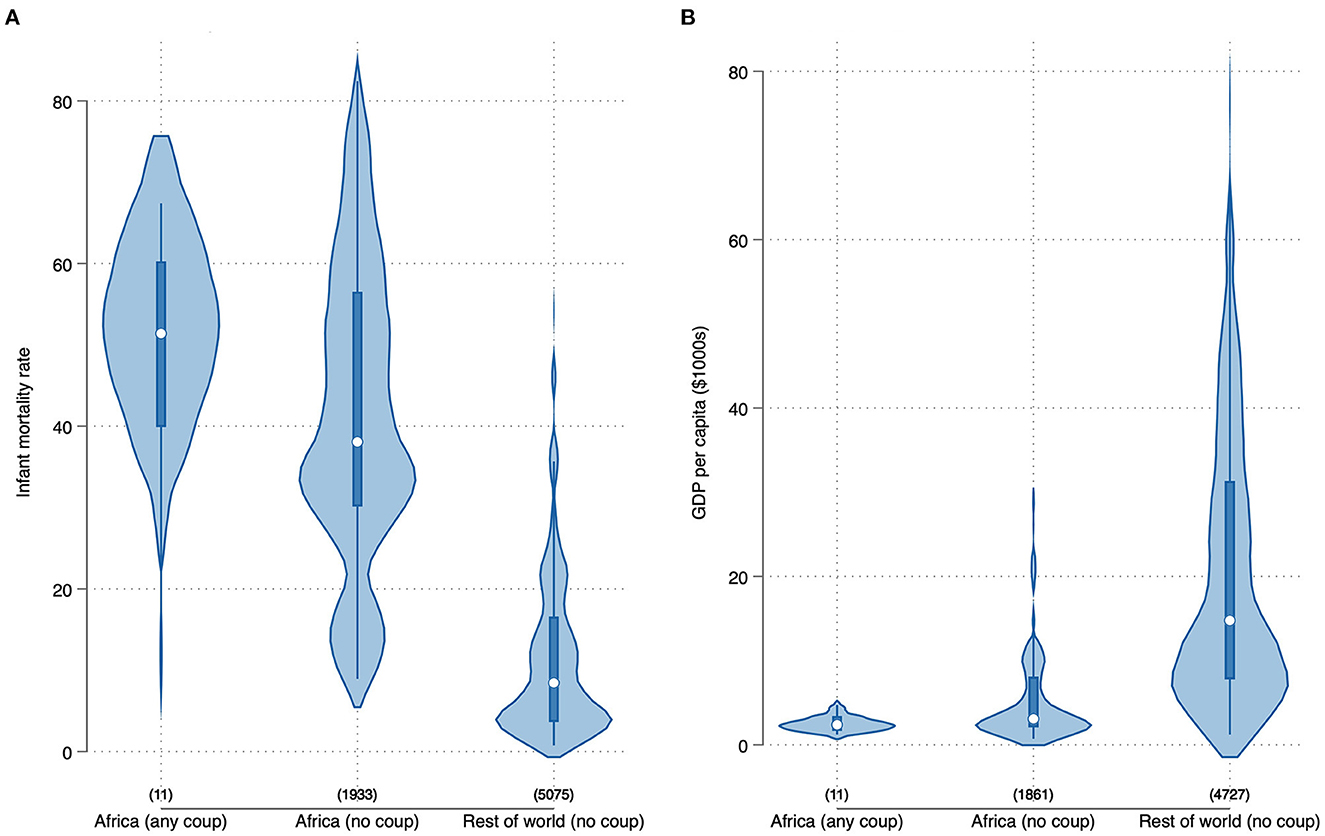

Second, is poverty a key driver of the recent coup wave? Yes, and no. Collier (2007, p. 35–36) famously argued that coup traps are mainly driven by two risk factors: low income and low economic growth. He concludes: “Because Africa is the epicenter of low income and low growth, it has become the epicenter of coups. But, controlling for these risk factors, there is no “Africa effect.” Africa does not have more coups because it is Africa, it has more coups because it is poor.” Looking at the most recent data, coup-prone African countries on average are somewhat poorer than other African countries and much poorer than the rest of the world (see the violin plots in Figure 5). In the 2020–2022 period, mean infant mortality rates (IMR)—a key proxy for poverty in the coup forecasting literature (e.g., Goldstone et al., 2010)—are only about 12 deaths per 1,000 live births in the rest of the world but is four times higher (48) in the recent coup-struck African countries.15 Likewise, the mean GDP per capita among African countries experiencing recent coups (≈$2,750) is nearly half that of African countries that have avoided coups (≈$5,400) and over 13 times lower than the rest of the world (≈$36,900).16 Put in terms of survival rates, not a single country with GDP per capita of over $6,000 suffered a coup during the 2020-2022 period, but nearly 15 percent of states with GDP per capita under $6,000 experienced a coup attempt.

Figure 5. Violin plots for two measures of poverty, by region and coup incidence from 2020 to 2022. (A) Infant mortality rates. (B) GDP per capita.

To the extent that poverty predicts coups,17 the relative poverty in Africa helps explain why coup risk in Africa is generally higher than other world regions. However, poverty—a slower-moving structural economic variable—is somewhat less helpful at determining which among Africa's impoverished countries actually suffered coups. We find little evidence that COVID-19—or grievances over government responses to the pandemic—directly triggered recent coups, though it is possible the pandemic had indirect effects. The pandemic led in 2020 to the worst economic recession that Africa had suffered in half a century (Zeigler, 2021). Yet economic woes by themselves, even if a necessary cause, were not sufficient to account for these coups.

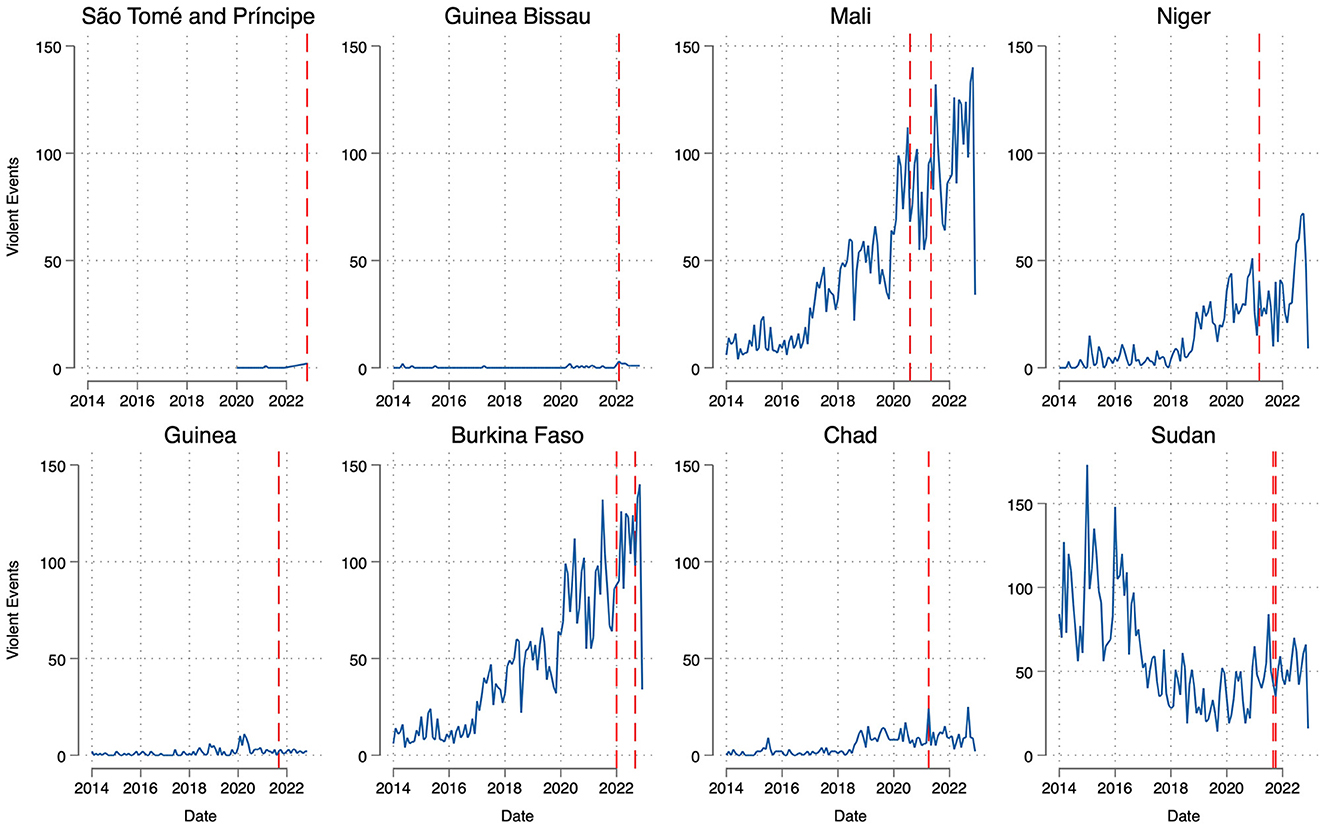

Third, one of the oft-discussed factors of recent coups in West African—Mali, Burkina Faso, and Chad especially—is the presence of the Islamist insurgencies, which France and the United States have done what they can to combat, including by training local military forces. In Mali and Burkina Faso, regime outsiders moved to oust perceived governments deemed unwilling or unable to defeat the insurgencies. In Chad, regime insiders moved to preserve the ruling regime after insurgents were able to kill their long-time leader (making a single battle with insurgents highly politically significant). Singh (2014, p. 75–77) dismisses this factor. He correctly notes that insurgencies in the Sahel have been raging for many years, yet there were no coup attempts in the region from 2015 through mid-2020. But just as poverty cannot be dismissed as a cause just because all poor states don't have coups right away, we do not think armed conflicts' effect need be immediate to be deemed a contributing cause. Many coups occur in the context of civil wars, especially when facing stronger rebel groups (Bell and Sudduth, 2017). The more that conflicts that drag on and threaten regime survival or state sovereignty, the more likely coups become, as soldiers seek to install leaders that can better prosecute the war (Aksoy et al., 2015).18 Figure 6 shows the time trend in monthly number of violent organized events in each of the eight recent coup-struck states in Africa.19 Overall, there is not a general or blanket connection between violent insurgency and coups in this set of countries, with violence either absent (as in Guinea, Guinea Bissau, and) or declining from historic peaks (Sudan) in half of the countries. However, violence was clearly getting worse in three countries prior to their COVID-era coups: Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger.

Figure 6. Time trend in organized violence in coup-struck African countries from 2020 to 2022. Source: Data on organized violent events is from ACLED at https://acleddata.com/. The dashed vertical lines for each plot marks the month of coup attempts in each country.

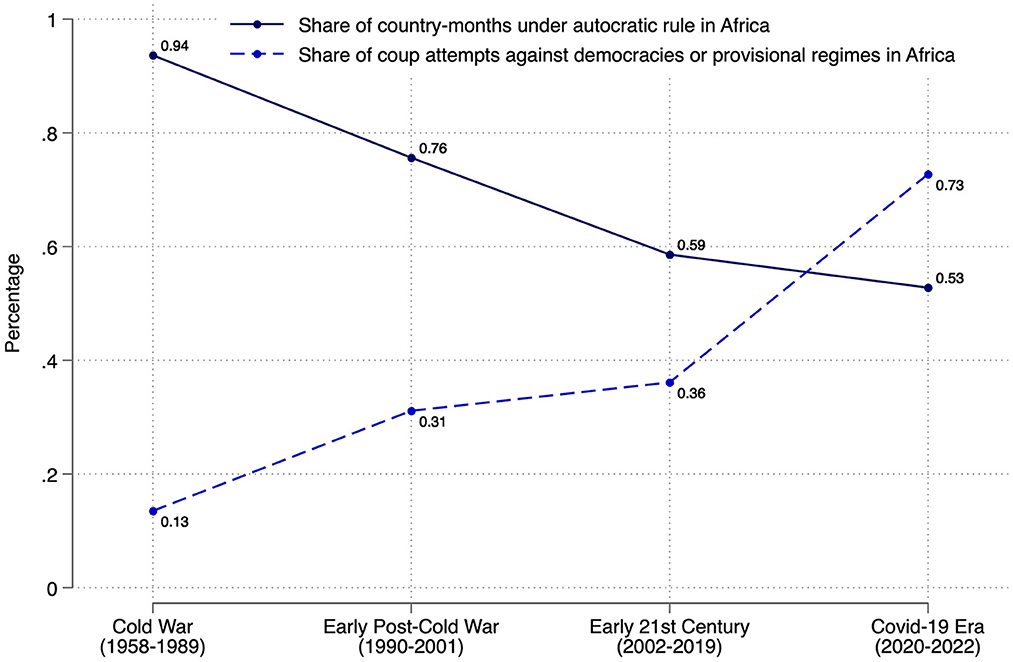

Fourth, some observers point to renewed turmoil of democratization (young democracies with poorly-funded militaries are much more likely to face coups than older consolidated democracies). Historically, coups in Africa disproportionately targeted dictatorships (democracies were rare). To understand African Cold War coup politics principally required knowledge about autocratic politics. As shown in Figure 7, democratic rule in Africa has become more common over time. An unfortunate by-product is that a majority of coups in the most recent period, for the first time ever, have targeted democratic (or provisional) governments rather than dictatorships. With the exception of Chad, none of the African countries suffering COVID-era coups are entrenched dictatorships.20 Understanding African coup politics now requires knowledge of politics in fledgling democracies. In Guinea, the military purported to strike back against an aspiring dictator. Yet, democratic backsliding does not seem to be the major factor in most of the cases reviewed above. If it were, given the global scope of democratic backsliding in recent years, we would expect coups to be distributed much more broadly. Like poverty, “problems of democracy” may be a necessary background cause, but by no means appears sufficient to explain recent coup patterns.

Fifth, and related to the challenge of democratic consolidation, some point to the problem of ethnic politics and entrenched ethnic armies. As Harkness (2022) notes, at least four of the seven African countries with recent coups—Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Niger, and Sudan—“are all struggling with a legacy of entrenched ethnic armies that want to preserve their influence over politics and financial benefits.” Looking at ethnic power relations (EPR) more generally, ethnicity is a salient political cleavage in 44 of 52 African states (≈ 15 percent) for which we have data from the EPR 2021 dataset for the post-2020 period (Vogt et al., 2015). Ethnicity is politically salient in all but one of the COVID coup-struck states in Africa (Burkina Faso being the exception). Having said that, ethnic grievances do not appear to have featured prominently in the coupmakers' public list of grievances (where coupmakers aired them). Ethnicity was only explicitly mentioned in media reporting we reviewed in one coup. We know the 2021 coup in Guinea was led by a co-ethnic of the president (Doumbouya and Condé were both Malinké), so that the 2021 coup in Guinea has to date had no discernible impact on ethnic power relations. The influence of ethnic politics in other cases, if present, is largely working below the surface of contemporaneous reporting. For example, Gen. Burhan and other Arab coup leaders in Sudan have dominated the transitional government in Sudan since 2019, and even more so since the 2021 coups. Given that Sudan's pro-democracy forces (FFC) sought to promote more ethnic inclusion, it is possible that vetoing a reduction in Arab power was a motivating factor in the October 2021 coup. Additional research—and data on ethnic politics in Africa during this period—is needed to further untangle these issues.

How long will COVID-era coupmakers in Africa survive in power? Perhaps unsurprisingly, most of the post-coup juntas have—often begrudgingly and under international pressure—committed to return their countries to constitutional rule (Elischer and Lawrance, 2022). In contrast to the Cold War, when many coup-makers launched open-ended coups and expressed long-term projects, the successful coups reviewed above are, with the exception of Chad, what Bermeo (2016) calls “promissory coups.” That is, even if disingenuous, the coupmakers have made promises to set timetables for a return to elections and civilian rule. That does not mean, however, that these coups are likely to spur democratization. If anything, they make democracy a more distant prospect.

Some observers fear that closer alignment with Russia—as opposed to France and the United States—in places like Mali and perhaps soon in Burkina Faso may undermine pro-democracy forces and help keep post-coup juntas in power. In Chad, democracies have tolerated a classic veto coup—blocking a transition to civilian rule to keep the Déby regime in power. Chad remains in good standing at the AU, and France and the U.S. have implicitly supported the coup (Elischer and Lawrance, 2022, p. 3). In some countries, particularly Sudan, civilian political opposition remains mobilized for democracy, and if they succeed in winning a democratic breakthrough it will be in spite of not because of COVID-era coups. Given the reluctance with which juntas have ceded genuine power to civilians so far, it's hard to see how any COVID-era coups can be characterized as “good coups.” However, because regional responses to coups are more severe today than during the Cold War, some observers are optimistic that instead of prolonged (direct) military rule, “militaries are likely to use elections to maintain power” indirectly (De Bruin and Dwyer, 2022).

Finally, will the recent uptick in coups in Africa continue? Some scholars think Africa may see more coups (e.g., Harkness, 2022; Santamaria, 2022), for several reasons. First, the countries with recent coups are at higher risk of falling into a “coup trap,” as coups often beget more coups in a country, in part because coups only exacerbate conditions favorable to coups—political instability and poor economic growth. Second, many African countries are poor by global standards, have a recent history of democratization (or democratic backsliding), and face demographic challenges (e.g., youth bulges) that generate economic and social grievances. Third, government weakness in the face of continuing jihadist insurgencies—the declared cause of the coups in Mali and Burkina Faso—will likely persist in the Sahel. Finally, there appears to be a lack of foreign actors that are willing or able to impose costs on coup makers that might actually deter coups. Given geopolitical cross-pressures, the U.S. has been hesitant to “call a coup a coup” and impose sanctions on post-coup regimes in countries where it has security partnerships (Harrison, 2022). And, as noted above, France is pulling back from the region, after having spent north of $1 billion to counter insurgency in the Sahel in Operation Burkhane since 2014. Meanwhile, non-democratic powers may fill the void, acting as “black knights” that could sponsor coups and prop up post-coup regimes.

The long-term effects of the recent coup surge in Africa remain to be seen. Whether this is a blip or just the beginning of a trend will only reveal itself in the fullness of time. Until then, we hope this current history helps readers better understand African coups in the COVID-19 era.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. Replication files will be available at https://www.johnjchin.com/colpus.

Author contributions

JC designed the study, wrote the introduction and discussion, wrote the Mali 2020 and São Tomé and Príncipe 2022 coup narratives, and edited all historical narratives in Section 2. JK wrote first drafts of nine of eleven coup attempts in Section 2. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Unless otherwise noted, all coup statistics in this article use Colpus data, extended through December 2022 by John Chin (Colpus version 1.0 documented in Chin et al. (2021) only covered coups through 2019). Thanks to Jodie Zheng for research assistance on the 2021 coups in Sudan.

2. ^The Western hemisphere (including Latin America) comes in a close second place with 194, followed far behind by Asia, 85; the Middle East, 53; and Europe, 39. Latin America was more coup-prone than Africa through the mid-1960s, however. See Figure 2 for a visualization of regional coup trends.