94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 21 September 2023

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1070508

This article is part of the Research Topic Blue Economy and Ocean Sustainable Development in a Globalised World: Social, Political, Economic and Environmental Issues View all 14 articles

Olusola Olalekan Popoola*

Olusola Olalekan Popoola* Ayo Emmanuel Olajuyigbe

Ayo Emmanuel OlajuyigbeThe Blue Economy is crucial for sustainable development in Africa, and the Gulf of Guinea, one of Sub-Saharan Africa's most economically dynamic countries, faces several challenges in transitioning into this economy. This study assesses the situation of the Blue Economy in the Gulf of Guinea and proposes strategies for its operationalization. A qualitative research approach was used to examine each member state's marine conservation initiatives, regional collaboration, management approaches, and strategic frameworks. Findings show that the Gulf of Guinea is already experiencing blue economy activities, but challenges like rapid population growth, urbanization, piracy, unsustainable anthropogenic activities, poor institutional frameworks, and climate change hinder the transition. The Gulf of Guinea's ocean economy accounts for less than 10% of GDP, so integrating the blue economy into trade strategies is crucial for its transformation. A systematic approach based on national priorities, social context, and resource base is needed to foster social inclusion, economic progress, and sustainable ocean development. Enablers of blue growth, such as integrated coastal zone management, marine spatial planning, marine protected areas, marine biodiversity, and blue justice discourse, must be integrated into policy design, prioritizing sustainability and equity. A cautious, phased approach is suggested, focusing on establishing traditional sectors, growing them, integrating value chains, and implementing regional collaboration so that the blue economy delivers on its social, environmental and economic goals in the Gulf of Guinea.

The ocean covers approximately seventy percent of the earth's surface, including the ocean, seas, rivers, streams, and lakes, serving as man's most vital support system (Allison et al., 2020). It contributes significantly to global wealth creation by supplying food, drinking water, clean air, job opportunities, climate regulation, waste treatment, biodiversity habitat, and functioning coastal and marine ecosystems (Sandifer and Sutton-Grier, 2014). For example, the ocean food sector provides nutrients in the form of protein for over 3 billion people and provides as many as 260 million jobs globally (Teh and Sumaila, 2011). Globally, it has been estimated that the value of the world's marine environment is US$2.5 trillion per annum (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2015). Recent studies indicate that the oceans contribute more than a quarter (US$24 trillion) of the world economy (US$94 trillion), and increased protection of critical marine habitats will result in additional net benefits of US$3 trillion by 2030 (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2015; OECD, 2016; Bax et al., 2021).

Given its potential for economic growth, employment, eradicating poverty, and ensuring food security, among other things, the ocean is considered a frontier for environmental sustainability and a necessary tool for achieving sustainable economic development (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 2020). Due to human activities like overfishing, coastal development, pollution, climate change, ocean acidification, and as well as the fact that the oceans' carrying capacity is at its limit, the ecosystems of the ocean are changing, thus significantly impacting human wellbeing (Nash et al., 2017). The rapid expansion of economic activities in the oceans without precaution will have significant implications for the already overburdened marine environment and resources, leading to injustices (Ehlers, 2016; Golden et al., 2017; Nash et al., 2017; Klinger et al., 2018). The injustices because of blue growth include dispossession, displacement, ocean grabbing, environmental justice concerns, degradation, undermining livelihoods, access to marine resources, inequitable distribution of economic benefits, social and cultural impacts, marginalization of women, human and Indigenous rights abuses, and exclusion from decision-making and governance (Bennett et al., 2020). As a result, immediate global and regional action is required to shield the oceans from the numerous pressures they encounter (United Nations, 2017).

Similarly, there is a need for a course that can advocate for the sustainable development of ocean spaces without jeopardizing their ability to perform their natural functions (Smith-Godfrey, 2016; Wenhai et al., 2019). The preservation and responsible utilization of oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development are critical due to the significant alterations occurring in ocean ecosystems. This is a key focus of one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) - SDG14 - that must be given top priority (Nash et al., 2017). This has necessitated increased efforts and investments by governments and stakeholders worldwide in policy reforms and rule changes to better safeguard and restore functionality in ocean ecosystems (OECD, 2019), resulting in the development of the Blue Economy concept. Furthermore, procedural, distributive, and recognition justice dimensions may be used as a comprehensive, all-encompassing framework to direct the planning, execution, and administration of ocean-based development efforts to ensure blue justice in the ocean environment (Bennett et al., 2020).

The Blue Economy (BE) aims to protect the world's ocean resources by promoting economic growth, social inclusion, and livelihood preservation/improvement while ensuring environmental sustainability and resilience (Smith-Godfrey, 2016; World Bank and UNDESA, 2017; Olteanu and Stinga, 2019; Essen, 2020; Martínez-Vázquez et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2022). BE seeks to decouple socioeconomic activities and development from environmental degradation while maximizing the benefits of coastal and marine resources (Lee et al., 2020). The Blue Economy concept is consistent with agreements that established the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which defines nations' rights and responsibilities regarding their use of the world's ocean and establishes guidelines for ocean economy, environment, and marine natural resource management (World Bank and UNDESA, 2017).

The Blue Economy concept has emerged as a significant driving force in achieving global sustainable development and the conservation of ocean and coastal resources (Union for the Mediterranean, 2017; Wenhai et al., 2019). This necessitates considering all three pillars of sustainable development: economic, environmental, and social, resulting in the development of initiatives that are environmentally sustainable, inclusive, and climate-resilient (United Nations, 2022). BE is based on Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM), which implements policy, activity, and investment coordination to improve the sustainability of coastal and ocean resources (OECD, 2019). Diversifying a country's economy to sea-based activities is crucial for achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs) and inclusive economic growth, ensuring increased economic benefits from sustainable marine resource use.

BE's overarching goal is to construct integrated economic activities and businesses related to ocean space to maintain a healthy economy without jeopardizing other parts of sustainable development (Spalding, 2016). BE promotes maritime and coastal resource protection by allowing for the formation of both international and regional integration, where member nations of a given region may foster collaboration and coordination (Haimbala, 2019). It also enhances land and sea management and the management and administration of marine ecosystems.

In Africa, the BE concept is being adopted internally and externally (Childs and Hicks, 2019). This is evident in the “Agenda 2063: the Africa We Want”, the 2050 African Integrated Marine Strategy, Policy Framework, and Reform strategy for fisheries and aquaculture in Africa (Pretorius and Henwood, 2019). Indeed, the African Union (AU) stressed the need to transition into the BE and therefore develop an initiative for a sustainable BE urgently to improve the socioeconomic wellbeing of Africans by fostering increased wealth creation along African oceans and seas in an environmentally sustainable manner (African Union, 2012). The African Union (AU) plays a significant role in developing and implementing the Blue Economy policy and strategy in the region (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 2016). Indeed, the African Union Commission has developed a pan-African agreement on the Blue Economy's vital role in encouraging structural transformation by 2030 (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 2016). The Blue Economy is now a primary goal and priority of the African Union 2063 Agenda, with Goal 6 focusing on the Blue/Ocean Economy for accelerated economic growth (AU-IBAR, 2019). Many African countries have already become signatories to the AU 2063 Agenda.

Only a few African nations, primarily those in the south of the continent, have successfully transitioned to the BE others are drafting policies to include the approach in their national development plans (Lopes, 2016). For instance, to generate employment, reduce poverty, and improve social equity, Operation Phaskisa (unlocking the ocean's economy) was launched in South Africa, while in Seychelles, “The Seychelles Blue Economy Strategic Policy Framework and Road map: Charting the Future (2018–2030)” was developed with four specific goals. It even established a ministry whose sole purpose was to advance the BE (Findlay, 2018). Although Madagascar is still establishing its own BE framework, it has made significant progress thanks to sustainable practices.

The Gulf of Guinea, which encompasses the sub-Saharan countries, is a diverse region stretching from Guinea Bissau to Angola (Ibe and Sherman, 2002), covering approximately 6,200 kilometers of coastline. The region is a crucial hub for shipping and transporting various products, such as oil, gas, and goods, to and from other parts of Africa (European Union, 2021). This region, known to be Africa's most populous and economically dynamic (Giulini, 2021), is yet to transit into the BE despite the tremendous progress made in Africa. Some reasons include weak political institutions, vicious clashes, climatic and demographic pressure, lack of economic growth, and misappropriation of natural resource revenues (Sartre, 2014). Others include a need for more government monitoring of the sea, an adequate awareness of the marine economy, which is responsible for the lack of an appropriate institutional framework, and unsupervised anthropogenic activities in the coastal and marine regions (Zhang and Xing, 2022). Therefore, actions of pirates, kidnapping, human and drug traffickers, and illegal fishermen, among other factors, have impeded security and, thus, threatened the achievement of BE goals in the region (Lindley, 2021). Overlooking these issues will hinder the potential economic growth that the ocean bestows as it calls for interventions in the area and beyond. Additionally, the natural resources presumed to support the BE are exposed to various hazards and environmental degradation. For instance, four West African countries (Benin, Côte d'Ivoire, Senegal, and Togo) lost an estimated $3.8 billion (5.3% of GDP) in 2017 to flooding, coastal erosion, pollution, oil pollution, and industrial and domestic wastes (Okafor-Yarwood et al., 2020).

Transitioning into the BE will aid in capturing economic marine opportunities while addressing the causes and risks of economic degradation and loss of natural capital (Patil et al., 2018). Transitioning to BE will discover and unlock the potential of the marine economy, thereby reducing ocean degradation and alleviating poverty (Kathijotes, 2013). Furthermore, the BE will stimulate economic growth, generate employment and investments, and reduce poverty while protecting healthy oceans and providing a clear vision for the national or regional development of the marine sector (Union for the Mediterranean, 2017). To this end, this study aims to assess the existing situation of the Blue Economy in the Gulf of Guinea and recommend strategies for its operationalization.

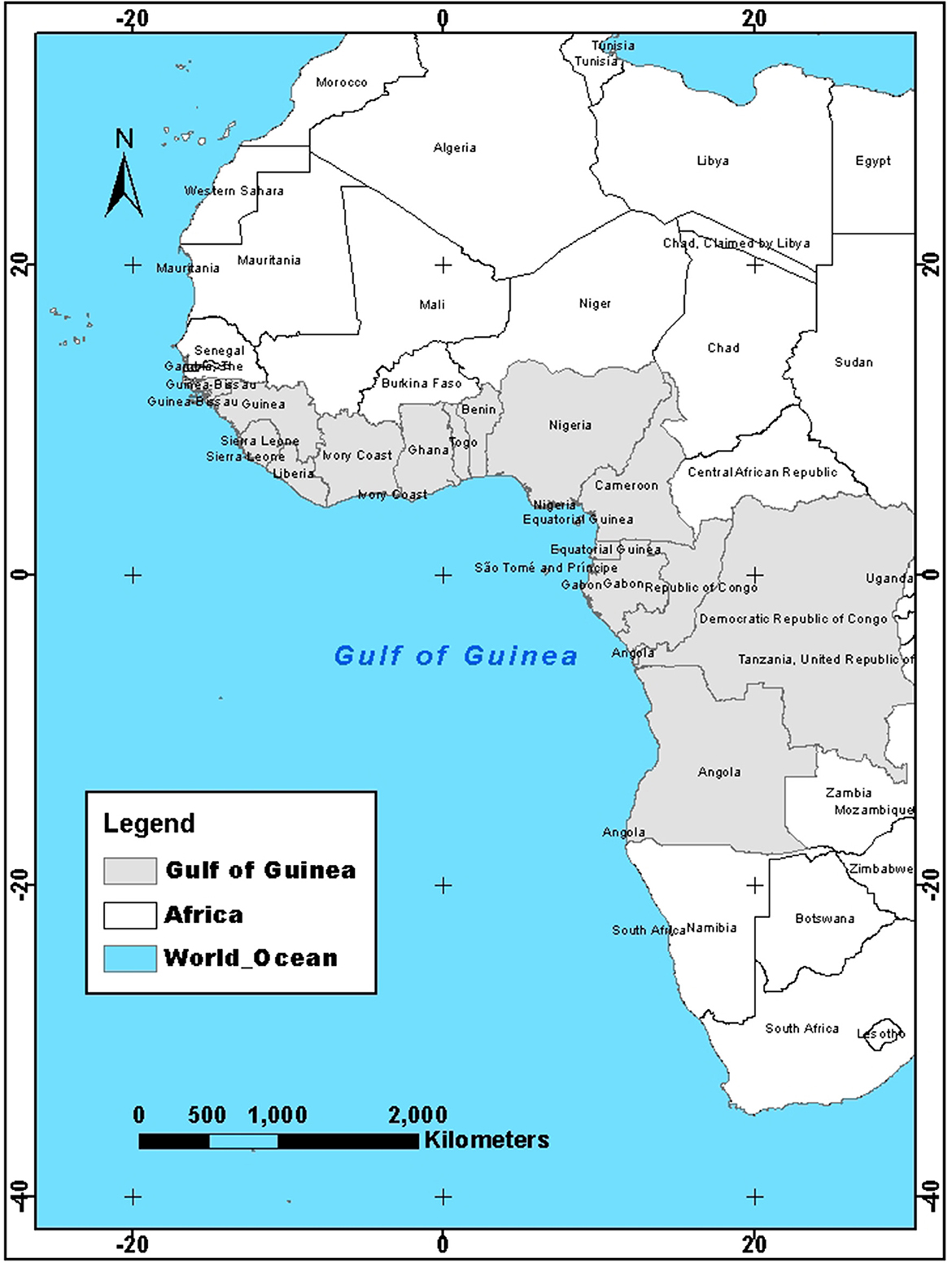

The Gulf of Guinea is situated in the northeastern part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean, extending from Guinea Bissau to Angola (Ibe and Sherman, 2002; UNESCO, 2021). It runs through countries like Guinea Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Sao Tome and Principe, Gabon, Republic of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Angola (See Figure 1). It also contains Islands such as Bioko, Sao Tome, Principe, Llehu, BomBom, Caroko, ElobeyGrandey, Elobey Chico Annobon, Corisco, and Bobowasi. This region is where a seasonal upwelling takes place along the equator and its northern coasts between Benin and Ivory Coast (Ali et al., 2011).

Figure 1. Countries adjacent to the Gulf of Guinea in the context of Africa. Source: Adapted from UNESCO (UNESCO, 2021).

The region has oil reserves of 51.34 billion barrels (3.11% of global reserves) and gas reserves of 202,346,000 million cubic feet (2.91% of global reserves) (Worldometer, 2016a,b). It is also endowed with lush rainforests, one of the world's principal suppliers of oxygen (Ghosh, 2021). It also contains one of the richest fishing grounds in the world, accounting for around 4% of worldwide fish output (Giulini, 2021; Morcos, 2021). Ten of the sixteen nations in the Gulf of Guinea have proven oil reserves, with Nigeria and Angola leading the way, accounting for 88.6% of total oil production in the region. Minerals found in this region include petroleum products, bitumen, diamond, gold, tin, manganese, and silver.

The area has some of the most dynamic economies in terms of socioeconomic aspects. For example, despite having a vast population of over 200 million people and a GDP growth rate of 2.7%, Nigeria still needs a significant proportion of export income and GDP from a broadly diverse blue economy base (Hamisu, 2019). Similarly, Cape Verde, with many islands and the largest Exclusive Economic Zone in the Gulf of Guinea, offers enormous potential for the BE through encouraging investments in ports and marine transportation, tourism, fisheries, and aquatic ecotourism (Fonseca, 2021). The area is recognized for issues such as high unemployment, poverty, informality in their economies, and poor infrastructure, exacerbated in the face of the COVID-19 problem (Grynspan, 2021). This region has many sovereign states that share similar economic qualities of poverty with a rapidly growing population.

This study utilized a qualitative research approach to scrutinize the blue economy activities, marine conservation initiatives, regional collaboration, management approaches, and strategic frameworks to transition into the BE in each Gulf of Guinea member state. Content analysis as a research tool was used to determine if these countries have developed a broad BE-based structure for their economies through textual evidence from the literature. The mode of data collection includes documents that refer to the blue economy or any other relevant existing marine initiative, blue agenda, blue growth, and ocean governance in each member state. This process entailed verifying whether member states have any framework for operationalizing the BE concept. The extent of transition into the BE was also assessed to determine if there are existing strategies or if these strategies are underway. It also proceeds to resolve the challenges hindering the operationalization of this concept. Further, it recommends an approach that will coordinate and incorporate the BE into trade strategies and industrial policies.

The analyzed documents were policy documents, reports, online documents, government reports, journals, and conference proceedings. These documents were derived from an extensive internet search for literature on the blue economy, blue growth, blue agenda, and strategies. Likewise, information was obtained through a focused web search on websites of national and continental government agencies and organizations and non-governmental organizations involved in marine activities.

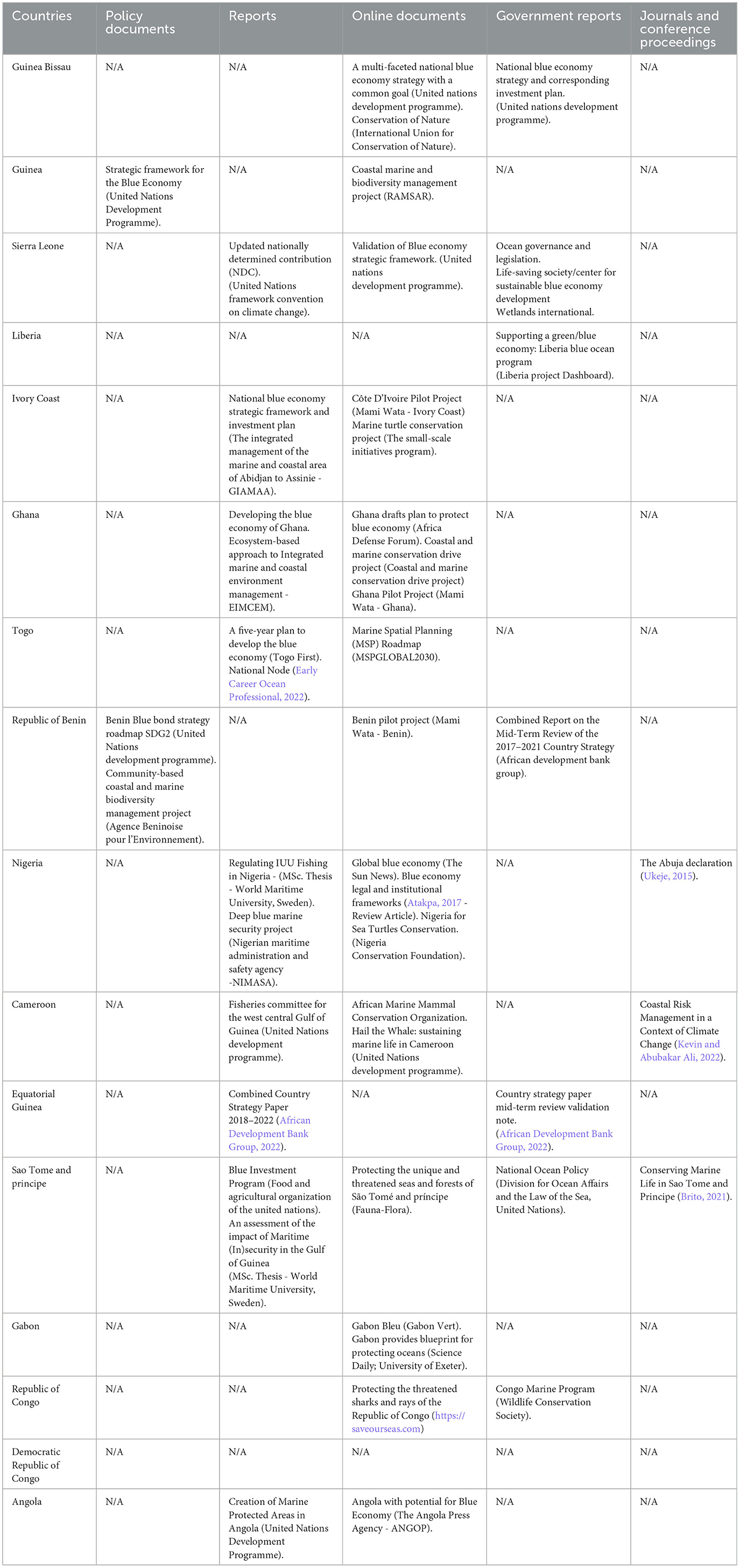

Documents about the transition to the blue economy were gathered from the official websites of each nation for content analysis. Many documents were received from several authorities that have established projects to shift toward the blue economy. Some of these papers have already been published, while others are planning frameworks presently being developed, yet others are in the implementation stage. Forty-nine papers on the blue economy were discovered in the Gulf of Guinea nations. Three (3) policy documents, twelve (12) reports, twenty-two (22) online documents, eight (8) government reports, and four (4) journal articles/conference proceedings are among them. Table 1 lists the documents used in the content analysis.

Table 1. Documents consulted in the content analysis showcasing the organizations involved in blue economy related activities in the Gulf of Guinea.

The study used blue economy derivatives such as blue economy activities, marine conservation initiatives, regional collaboration for ocean sustainability, management approaches adopted for ocean management, strategic frameworks for the blue economy, goals and objectives of ocean management strategies, blue growth and blue agenda, coastal and marine spatial planning to narrow down on key search items that capture the blue economy for the content analysis. The study looked at the denotative incidence of these essential phrases as solo words or in conjunction with other notions associated with blue economy narratives. Where the blue economy was not expressly addressed, the research identified it using proxies such as ocean management, ocean governance, coastal/marine management, and marine protected zones. This strategy is congruent with Bauler and Pipart (2013), who proposed that empirically validating the first step of conceptual adoption begins with a question about how frequently the term is used in policy papers. In addition to keyword research, the study included direct content analysis (Geneletti and Zardo, 2016), which scans all available blue economy contents for information about each Gulf of Guinea nation.

This section scrutinized variables for attaining the blue economy, including the blue economy activities, marine conservation initiatives, regional collaboration, management approaches, and strategic frameworks to transition into the BE in each Gulf of Guinea member state. Regarding the blue economy activities in the member states, many of the member states in the Gulf of Guinea share several similarities, including fisheries, aquaculture, port services, maritime transportation, and tourism (Economic Commission for Africa, 2014). Some countries such as Guinea Bissau, Guinea, Nigeria, Cameroon, Gabon, Republic of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Angola are engaged in oil and gas, with their scale of activity varying from one country to another. There are cases of some member states, such as Guinea Bissau, Sao Tome and Principle, and Angola, that are involved in wind energy generation (Economic Commission for Africa, 2014).

This study's findings indicate that many member states along the Gulf of Guinea have developed or have ongoing marine conservation initiatives. Guinea Bissau has developed a mangrove restoration project to rehabilitate damaged ecosystems and protect species and habitats (International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2019). Guinea has an ongoing project on coastal marine and biodiversity management. This project includes creating marine protected areas (MPAs) in RAMSAR sites, capacity building for MPAs management, support to participative local development, and project management, monitoring, and evaluation. The management approach focuses on the sustainable use of marine resources, biodiversity management, legal and institutional reform, and social and economic development (World Bank Group, 2015).

The marine conservation initiatives of Sierra Leone focus on sustainable coastal zone management, seagrass conservation, and the establishment of marine protected areas to promote the long-term ecological, social, and economic wellbeing of coastal communities and ecosystems (Wetlands International, 2008). Regarding Liberia's marine conservation initiatives, the primary goals are to improve science-based understanding of factors affecting the health and services provided by coastal and marine ecosystems, address marine pollution, implement effective governance, manage coastal and marine ecosystems in concert, and increase public awareness and education (Liberia Project Dashboard., 2019).

Cote d'Ivoire has set up a marine initiative to conserve marine ecosystems and biodiversity through the Integrated Management of the Marine and Coastal Area of Abidjan to Assinie (GIAMAA). The initiative's objective is to promote responsible and sustainable utilization of resources while ensuring that ecosystem services continue to be available in the long run, thereby supporting economic growth and the wellbeing of coastal communities (Mami Wata., 2018a). Another initiative is the Marine Turtle Conservation Project (The Small-Scale Initiatives Program, 2014). In Ghana, the Coastal and Marine Conservation Drive Project has been embarked on to promote local economic development and nature protection and contribute to the achievement of some sustainable development goals 1, 2, 8, and 14, which are to reduce poverty, reduce hunger, provide decent work and economic growth, and life below water (Lighthouse Foundation., 2021). Another initiative in Ghana is the Ecosystem-based approach to Integrated Marine and Coastal Environment Management (EIMCEM). This initiative adopts a marine spatial planning approach that is expected to enable Ghana to use integrated management tools inclusively to reduce excessive human pressures on marine resources for sustainable use (Mami Wata., 2018b).

Togo has an active Early Career Ocean Professional (ECOP) that supports ocean conservation and sustainable development (Early Career Ocean Professional, 2022; Dossavi, 2023). Togo has already developed a marine spatial planning (MSP) roadmap under the MSPGLOBAL2030 initiative to manage its marine resources sustainably (MSPglobal., 2022). Indeed, there are already underway Blue Economy initiatives in Togo (Dossavi, 2023). Benin's focus on fisheries, tourism, and aquaculture aligns with its goals of increasing economic growth and reducing poverty. The country has a Community-Based Coastal and Marine Biodiversity Management Project that aims to promote the conservation and responsible utilization of biological diversity of coastal wetlands and marine resources while supporting the livelihood and economic opportunities of the coastal and marine communities (Agence Beninoise pour l'Environnement, 2010). Benin has also embarked on the Integrated Marine and Coastal Zone Management (GIZMaC) project to promote sustainable management of marine and coastal resources (Mami Wata., 2018c).

Nigeria's existing marine conservation initiatives include the West Africa Coastal Management Program, Nigeria Conservation Foundation, and Nigeria for Sea Turtles Conservation (Nigeria Conservation Foundation, 2020). Noticeable marine initiatives in Cameroon include sustaining marine life in Cameroon (Ayissi et al., 2018; UNDP, n.d.) and the initiative of the African Marine Mammal Conservation Organization (AMMCO), whose task is to make the coastal and aquatic environment a threat-free home for aquatic wildlife (AMMCO, 2021). Equatorial Guinea has tried to conserve marine areas through cumulative impact mapping to prioritize marine conservation efforts (Trew et al., 2019). Sao Tome and Principe is implementing measures to protect threatened seas and forests by establishing marine protected areas and sustainable use zones (Fauna-Flora, 2023). This will restore biodiversity and improve indigenous communities' economic prospects. The community actively creates and manages these protected areas, demonstrating their unwavering dedication to the cause (Fauna-Flora, 2023). Likewise, concerted actions regarding marine life conservation have been adopted, with implementation in progress (Brito, 2021).

Gabon has launched the Gabon Bleu initiative, which aims to protect endangered marine biodiversity through protected areas and a sustainable fisheries management plan (Gabon Vert, 2023). The Republic of Congo's conservation initiative is the Congo Marine Program which focuses on the designation of marine protected areas, the development of an Integrated Marine Spatial Tool for maritime reforms, and capacity building for fisheries management, surveillance, and law enforcement by local administrations (Wildlife Conservation Society, 2021). Another marine initiative in the Republic of Congo is the ‘Save Our Seas' initiative, which seeks to protect the threatened sharks and rays in the country to increase the knowledge base on these taxa and to apply informed and appropriate solutions for conservation (Doherty, 2023). The Democratic Republic of Congo does not have a marine conservation initiative at the time of this study. Angola has created marine protected areas in response to the country's degradation of coastal and marine ecosystems (UNDP, 2022c).

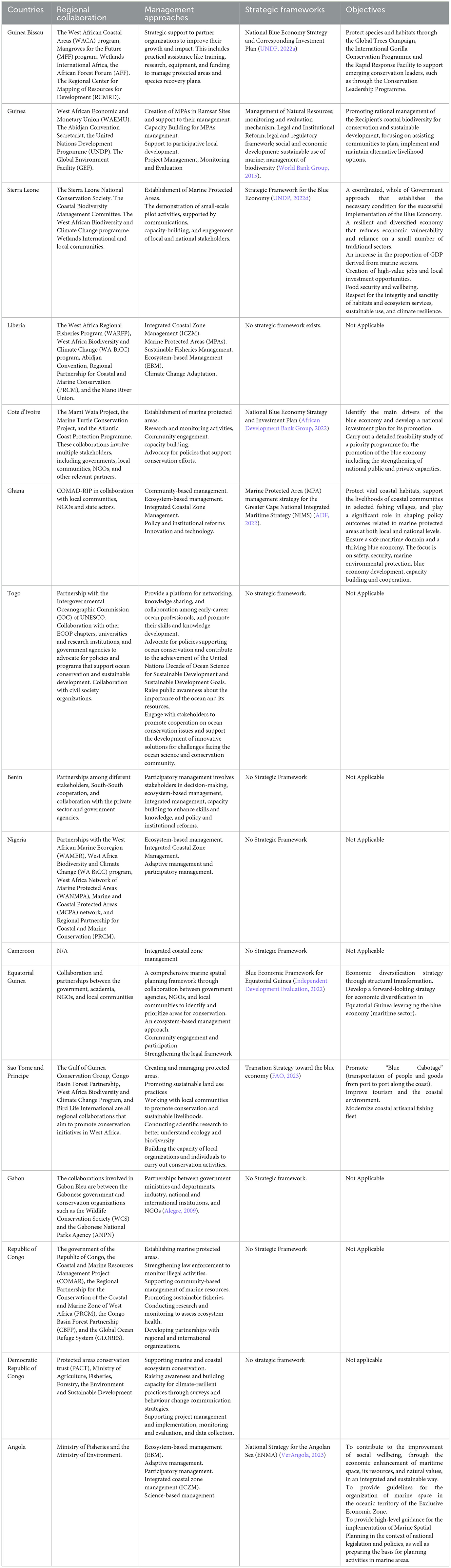

Fostering regional collaboration among Gulf of Guinea member states is crucial for achieving blue economy growth. This is because regional collaboration can promote ocean-based good governance in areas such as environmental protection of regional marine commons, maritime surveillance to prevent marine resource pillage, and mitigation of climate change impacts on marine resources (Bolaky, 2020). Sustainable management approaches and strategic frameworks are essential in transitioning to a blue economy. As detailed in Table 2, findings from this study indicate that many of these countries have a series of regional collaborations meant to promote a blue economy. Likewise, many management approaches are being undertaken by these countries, which could help to transition into a blue economy. Still, strategic frameworks have yet to be in existence in many of the nations. The Regional Collaboration in the member states is commendable, with collaborations involving governments, local communities, NGOs, and other relevant partners. These collaborations have contributed to achieving sustainable development goals, including conserving marine ecosystems, protecting marine life, and promoting local economic development. For instance, in Cote d'Ivoire, the Mami Wata project, Marine Turtle Conservation Project, and Programme for the Protection of the Atlantic Coast involve multiple stakeholders in achieving marine conservation and biodiversity conservation (Mami Wata., 2018a).

Table 2. Regional collaboration, management approaches and strategic frameworks for transitioning into the blue economy in the gulf of guinea.

Marine protected areas (MPAs), Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM), Sustainable Fisheries Management, Ecosystem-based Management (EBM), community engagement, capacity building and knowledge sharing, innovation and technology, and community-based management of marine resources are among the management approaches being used. Seven of the sixteen Gulf of Guinea nations have created or are building strategic frameworks for transitioning to the blue economy (Table 2). For example, Guinea Bissau and Cote D'Ivoire have a National Blue Economy Strategy and Investment Plan, Sierra Leone has a Strategic Framework for the Blue Economy, Ghana has a National Maritime Strategy, and Equatorial Guinea has a Blue Economic Framework. Angola, on the other hand, has produced the Angolan Sea National Strategy. These results suggest significant external involvement, collaboration, and activity in the area connected to ocean and marine resources. Despite this, there is a lot of disparity and poor alignment about the Blue Economy since only 7 of the 16 nations have frameworks that appear to support the blue economy.

Furthermore, as shown in Table 3, which refers to the Blue economy documents, blue agenda, and ocean governance along the Gulf of Guinea, it is evident that actions and strategies are in place in many member states that can serve as enablers of blue growth. These enablers are biodiversity and conservation strategy, marine spatial planning, marine protected area, integrated coastal zone management, and maritime strategies. However, nearly 20% of the countries in the region still need documents that refer to the blue economy. This demonstrates that these nations need a BE. Framework, which prevents them from exploiting ocean resources sustainably for economic development, improved quality of life, employment possibilities, and maintaining the health of ocean ecosystems.

Additionally, research reveals that 50% of the nations in the Gulf of Guinea need more documentation outlining the blue agenda/growth development. As a result, these nations need to execute the core components of the Blue Agenda/Blue Growth initiatives, which include understanding the marine environment, marine spatial planning, and integrated surveillance. Where they have been implemented, the blue agenda/growth has been tilted toward maritime spatial planning, including identifying marine protected areas.

Despite some of these nations' success in securing and managing ocean space, a formal model is needed to enhance the environmental performance of the BE sectors. This agrees with the findings of Martínez-Vázquez et al. (2021) that the BE sectors' growth presents challenges, such as a lack of standard and agreed-upon goals for blue growth. Other factors include maximizing economic growth from marine and aquatic resources (Boonstra et al., 2018) and maximizing inclusive economic growth derived from marine and aquatic resources (Eikeset et al., 2018).

So far, progress in capitalizing on the rising demand for BE goods and diversifying into the BE has been slow in the Gulf of Guinea since none of these initiatives focuses on ultimately capturing the financial advantages of the Gulf of Guinea's ocean resources in a coordinated manner. This assertion is in line with the findings of Rustomjee (2017) that despite these initiatives and measures adopted in the Caribbean, little headway has been made in leveraging the rising global demand for the goods and services that the small island nations presently provide or in diversifying into new and developing blue economy sectors and industries. As a result, remedial efforts such as research into the ocean environment, coordinated surveillance, and well-developed marine spatial planning are required throughout the Gulf of Guinea to transition into the Blue Economy.

Maritime insecurity and safety are among the factors hindering the development of a framework for BE in the Gulf of Guinea. The Gulf of Guinea has gained disrepute over the years as a danger zone with security challenges such as piracy, kidnapping, and human and drug trafficking (Ukeje, 2015). Despite the economic potency of this region, being a significant source of crude petroleum, oil and gas, and an essential global maritime corridor, maritime insecurity has grown to become a considerable challenge compromising and threatening its development over the years (Ikein, 2009; Ukeje and Ela, 2013). The Nigerian marine space, for example, has reports of diverse forms of illicit trafficking, kidnapping, the prevalence of piracy, and armed robbery, which has resulted in some shipping companies avoiding these waterways (Ugwueze and Asua, 2021). Moreover, the Port of Cotonou in the Republic of Benin has experienced a significant decrease of 70 percent in the number of vessels calling because piracy and armed robbery are common occurrences at sea (Okafor-Yarwood et al., 2020). Security challenges are perceived to be more severe in smaller Islands like Sao Tome and Principe, where issues like oil and cargo theft are predominant because of geographic remoteness and high reliance on natural resources (De Ceita, 2020). However, BE can only thrive in a safe, secure, well-regulated maritime environment (Quak, 2019; De Ceita, 2020).

Environmental degradation is another major hindrance to BE in the Gulf of Guinea, as achieving a sustainable BE requires a healthy coastal and marine ecosystem (Okafor-Yarwood et al., 2020). Sources of pollution from chemicals, particles, domestic wastes, industrial wastes, agricultural wastes, and noise, or the spread of invasive organisms affect the ocean in the Gulf of Guinea, resulting in habitat degradation, loss of biodiversity, and degeneration in human health (Akita et al., 2020). These led to various forms of environmental debacle such as flooding, coastal erosion, pollution of various degrees and types, chronic illnesses, loss of species, and the inability of the ocean to perform its natural function (Popoola, 2012, 2022). Coastal and ocean degradation is caused by impacts of climate change with grave consequences such as fishery depletion, rising sea levels, and threat to the survival of ecosystem biomes which serve as habitats for ecosystem wildlife (Popoola et al., 2019; Popoola, 2021). Similarly, the inadequate institutional structure for administrating and developing marine and coastal environments presents a significant obstacle (Adibe et al., 2018; Denton and Harris, 2019).

Other challenges include unstrained and uncontrolled numerous anthropogenic activities in the coastal and marine space, poor ocean governance, and inadequately trained personnel on climate change and environmental mismanagement, which need to be addressed to reap the full potential of BE (Bolaky, 2020). Additionally, the region has been unable to create a just and inclusive ocean economy due to the neglect of social inequities caused by the quick and unrestrained expansion of maritime resources in the area. Harnessing the benefits of the BE requires immediate attention to the challenges of insecurity and environmental degradation, as failure to address these could deprive these nations of the economic gains derivable from the ocean (Okafor-Yarwood et al., 2020).

Harnessing the potential of blue economy growth and development is crucial for Africa's transformation and regeneration (Karani et al., 2022). In the Gulf of Guinea, various activities or limited BE activities are carried out in the marine area (though unsustainably), contributing to <10% of the GDP in member states (Giulini, 2021). The ocean economy contributes as little as a quarter of all revenues and one-third of export revenues (Saghir, 2016). The reason for this is that broad-based BE needs to be integrated or weakly integrated into the trade strategies of these countries. Therefore, implementing the BE into the trading strategy of member countries will be the right step in the direct direction of harnessing economic and social benefits (Hamisu, 2019). This is because there are various benefits and gains to be accrued from trade and deepened integration of these countries in global and regional trade once the related constraints are addressed (Bolaky, 2020).

As revealed in Table 4, Angola earns 37.9 percent of its GDP mainly from exporting crude petroleum, among other goods and services such as precious stones, beverages, and foodstuff. The only blue economy-based goods and services are fisheries such as non-filet frozen fish, mollusks, fish filet, and crustaceans which reduced from 4.6 percent of the country's GDP in 2011 to 2.1% in 2018 (The Global Economy, 2022). Crude oil, petroleum gases, and cocoa beans dominate Cameroon's export products. Its top blue economy-based export product consists of fish, crustaceans, and mollusks constituting 1.8 percent of total goods exports. The same applies to many countries in the Gulf of Guinea, where the only blue economy-based goods and services are fisheries and aquaculture, constituting only a minute percentage of each county's GDP. Other blue economy-based activities such as shipbuilding, offshore oil and gas, marine construction, marine seabed mining, marine research and development, and marine transport still need to be explored.

In terms of export services, travel services in the form of business and personal travels dominate in many countries such as Ivory Coast, Togo, Republic of Benin, Nigeria, Cameroon, Gabon, Sao Tome and Principe and DR Congo, and Angola. However, sea transportation under-exploited needs to be more explored in these countries as the primary mode of international travel is by air. Marine tourism is another service that remains to be tapped in these countries except in Ivory Coast and Togo, where the service is gradually being developed (Agbota, 2019). The development of maritime tourism requires a secure and clean waterway which is a challenge in the Gulf of Guinea as the ocean is troubled by insecurity and environmental degradation. Once the related challenges hindering the transition of member countries have been addressed, there are significant opportunities to be gained from international and regional trade among nations (Failler et al., 2020).

Achieving a sustainable BE as a continent requires a certain level of cooperation internationally and regionally (Haimbala, 2019). Given this, the AU proposed many strategies for African nations to transition into BE. For instance, the Inter-Agency/Transitional cooperation on maritime safety and security to address maritime security and safety, thereby providing situational awareness in the maritime province of African countries (African Union, 2012). Another strategy plan is the establishment of the Combined Exclusive Maritime Zone of Africa (CEMZA) to boost African trade by simply eliminating or simplifying administrative procedures in intra-AU maritime transport (African Union, 2012).

Furthermore, the African Blue Economy Strategy (ABES) was developed in 2019 by merging five detailed thematic areas considered essential to the growth of the African Blue Economy (Failler et al., 2020; Karani et al., 2022). The first is the conservation of aquatic life and the sustainability of aquatic ecosystems. Second, it includes shipping, marine transportation, security, and safety, while the third area is concerned with coastal and marine tourism, climate change, resilience, environment, and infrastructure. The fourth thematic area relates to sustainable energy, mineral resources, and marine industrialization, and the fifth is policies, institutional frameworks and governance, employment, job creation and poverty eradication, and innovative financing (Karani et al., 2022). The strategy is designed to assist and support AU member countries and other regional institutions in developing their own individual national and regional BE strategies based on SDG 14, “Life below water,” and Agenda 2063.

Transitioning into the BE is ambiguous and complex, so it must be done in phases. The Blue Economy encompasses several sectors with significant potential for collaboration, giving positive incentives for progress toward more integrated legal, regulatory, and institutional frameworks (Economic Commission of Africa, 2016). This study proposes three stages for moving into the blue economy. The first phase focuses on existing and traditional sectors of the BE, which necessitates the development of policies to increase and deepen profit and benefits from current blue industries and projects (World Bank and UNDESA, 2017). Examples include fishing, marine transport, shipping, mining, and marine food processing. Fostering regional collaboration and enhancing additional growth in these areas is vital. While some sectors require little effort, others may necessitate better encouragement and additional governance to achieve their full potential and yield maximum output (World Bank Group, 2016).

The next phase focuses on directing policies, incentives, and regional collaboration toward emerging sectors of the BE (Bolaky, 2020). Successful implementation of existing sectors of the BE enhances the diversification of the economy into emerging ocean-based activities and sectors (Rustomjee, 2017). These sectors include marine aquaculture, deep-water oil and gas exploration and drilling, offshore wind energy, ocean renewable energy, marine and seabed mining, marine biotechnology, and high-tech marine products (Martínez-Vázquez et al., 2021). The final stage focuses on fostering blue-based regional value chains based on a mix of traditional and non-traditional BE-based industries (Bolaky, 2020). It is vital to intensify the creation of regional, blue-based value chains that integrate traditional and non-traditional industries. Due to its potential to increase production and processes and improve cross-border marketing of marine products and international markets, value chain development significantly boosts the BE (Haimbala, 2019).

Trade, investment, technology, private sector activities, state and state-owned firms, regional collaboration and integration, and cooperation are some of the factors that enable the implementation of the blue economy (Purvis, 2015). Even if the exportation of marine products and services will increase investment profitability, these elements will support the BE's goals. The many social actors, including the government, the commercial sector, and the scientific ones, must cooperate for a country or region to transition into the BE successfully (Roy, 2019). Due to the multisectoral character of the concept, stakeholders, especially among research institutions, must be fully engaged and involved in the development of the BE. The business sector and ocean users could collaborate to address crucial monitoring needs by considering the appropriate role and innovative alternatives for various levels of government, as they can generate and direct scientific breakthroughs (Howard, 2018; Wenhai et al., 2019).

Government agencies provide direction, planning, coordination, and oversight. Additionally, they promote and create legal and policy frameworks for sustainable oceans, draw in private investors, and take the initiative to help launch the developing blue industry, which must be regulated by accountability and transparency. There is also the place of the private sector, which quickly embraces the BE concept to invest and explore ocean-based resources and services (Voyer and van Leeuwen, 2019). At the same time, they must be involved in implementing action plans for sustainable economic growth and enhanced social wellbeing (Whisnant and Vandeweerd, 2019).

Applying blue justice to end all injustices that may arise due to the region's rapid growth of ocean resources is a crucial factor that might influence the implementation of the blue economy. Processes for making decisions about the ocean economy should be guided by an explicit justice framework (Bennett et al., 2020). This might entail a significant shift in ocean governance and a reevaluation of core values about ocean development, raising several concerns with potentially complex answers involving resource grabs and other ideologies prioritizing profit above people and the environment. Recognitional justice, procedural justice, and distributional justice are crucial to lessen or completely eradicate inequities in the ocean environment.

Regional cooperation and member-state cooperation are integral constituents of the development of the BE (Bertarelli, 2020). Regional cooperation tools include economic integration, trade, investment, remittances, debt relief, humanitarian interventions, peacebuilding, and export credit lines (Gay, 2022). The Gulf of Guinea member states are endowed with various resources, which must be managed domestically and regionally if they are to be perpetuated. Regional collaboration will help assess how governments collaborate, as well as with foreign funders and stakeholders, to strengthen maritime security in the broader region in the face of maritime instability in the Gulf of Guinea.

Additionally, cooperation at the national, regional, sub-regional, and global levels will improve collaboration, knowledge sharing, and the exchange of effective practices to assist marine research and development in the Gulf of Guinea. Furthermore, coordination among the member nations would promote joint initiatives so that those wishing to increase capacity might benefit from those who already have it and vice versa (Mohan et al., 2021). With the aid of regional cooperation, combating concerns like piracy, environmental degradation, and climate change becomes simpler.

Through intra-regional commerce in maritime goods, the Gulf of Guinea's member nations' economic integration will strengthen competition. Indeed, intra-African trade is minimal compared to other continents with significant economies (Mold, 2022), despite the assertion that intra-African commerce in marine goods and services will be Africa's primary force behind industrialization (Uranie, 2016). The African Continental Free Trade Area's efforts to increase intra-continental trade between Africa and the Gulf of Guinea are liberalizing deeper levels of trade and improving regulatory harmonization and coordination (Signé, 2022). Additionally, it can bring roughly 30 million people out of poverty by 2030 and increase intra-African commerce from 18 to 50% (World Economic Forum., 2022). Regional organizations like regional markets can strengthen member-state collaboration on BE and increase Africa's sustainable use of its blue resources (Bolaky, 2020).

The study has established that several blue economy activities are already present along the Gulf of Guinea. As noted, the member states have several marine conservation initiatives. They also have some form of collaboration regionally to promote the blue economy, and several management approaches have been undertaken or are being developed to manage the ocean environment. Some of these management approaches include the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs), integrated coastal zone management (ICZM), ecosystem-based management (EBM), adaptive and participatory management, and marine spatial planning (MSP). These management strategies are enablers of blue growth. A well-developed marine strategic framework needs to be improved in many of the member states. However, there are pieces of evidence that this is already being developed by some member states such as Guinea Bissau, Sierra Leone, Cote d'Ivoire, Ghana, Equatorial Guinea, Sao Tome and Principe, and Angola.

Furthermore, several ocean governance initiatives exist along the Gulf of Guinea, as detailed in Table 2. However, several challenges hinder the transition into a blue economy in this region, which include rapid population growth, urbanization, piracy, armed robbery, trafficking of people, illicit narcotics and weapons, climate change-induced rising sea levels and ocean acidification, overfishing, unregulated fishing and other unsustainable fishing practices (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 2016). A crucial objective for Africa's transformation and regeneration is to fully use the potential of the blue economy for growth and prosperity, hence the need to integrate the blue economy into trade strategies. However, <10% of the GDP of member nations in the Gulf of Guinea comes from marine activities, with the ocean economy accounting for barely a quarter of total revenues and a third of export earnings. Indeed, economic and social benefits are hampered by a lack of broad-based biodiversity (BE), including factors like excluding manufactured goods and services from trade strategies and raw and commodities with added value. Deeper integration and economic progress may result from addressing obstacles and incorporating BE into member nations' trade policies.

Furthermore, blue justice has been presented as a paradigm for achieving sustainable and equitable blue economy governance (Axon et al., 2022). The omission of the blue justice discourse from the Gulf of Guinea's blue economy will impact its implementation with disastrous implications. The effects will include economic disparity, a lack of local advantages, adverse social and cultural repercussions, pollution, and displacement of the local population (Bennett et al., 2019). Unchecked development in the Gulf of Guinea may result in human rights violations and “ocean grabbing” since ocean spaces and resources may be privatized for blue growth, resulting in blue injustices.

Since the BE aims to foster social inclusion, economic progress, and sustainable development to the greatest extent possible, it is essential to address some of the security, environmental, political, and institutional problems in the Gulf of Guinea that prevent the operationalization of this concept from reaping its many benefits of it. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the Gulf of Guinea Commission (GGC) can work together through trade, investment, finance, technology, and information sharing to address these difficulties at the regional level.

Transitioning into the blue economy requires a systematic approach based on national priorities, social context, and resource base (World Bank Group, 2016). Member states must recognize the need for biophysical characteristics, capacity, and synergies between sectors for efficient management. Marine and coastal spatial planning integrated maritime surveillance, digital mapping, and data-limited stock assessments are essential for authorities, businesses, and communities (World Bank Group, 2016). Mobile technology is needed to gather previously unavailable data in the ocean sector. Integrated coastal zone management (ICZM), an enabler of the blue economy, enhances coastal protection and nearshore resources while increasing efficiency (Popoola, 2012, 2014). Adopting ICZM involves mapping, delineating, and demarcating hazard lines, building capacity for informed decisions about growing the blue economy within the carrying capacity of the natural resource base. Also, the blue economy requires assessing the value of marine resources, which needs to be better measured and understood (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2015). Other enablers of blue growth, including strategies like marine protected areas, marine spatial planning, and marine biodiversity and conservation, are essential to transition into the blue economy.

Blue justice discourse must be integrated into the design and implementation process of transitioning into the blue economy in the Gulf of Guinea. This will require proactive, systematic, and bold policies that recognize, meaningfully involve, and treat all coastal people fairly regarding how ocean and coastal resources are accessible, utilized, managed, and enjoyed across the countries in the Gulf of Guinea. Prioritizing sustainability and equity in ocean negotiations, developing comprehensive legislation, fairly treating local populations, and sharing wealth generated by blue growth, inclusive governance, and ocean science insights for policy design, and monitoring impacts are critical for incorporating blue justice into the Gulf of Guinea's blue economy (Bennett et al., 2019; Blythe et al., 2023).

A cautious, phased approach is suggested for a smooth transition into the Business of Enterprise (BE) as Africa's revival frontier. Phase 1 focuses on establishing existing and traditional sectors and deepening their benefits. Phase 2 focuses on growing sectors and launching local initiatives to expand the concept. Phase 3 emphasizes value chain development to integrate traditional and non-traditional sectors. Collaboration between coastal governments, business communities, non-governmental organizations, scientific communities, and local inhabitants is essential to achieve BE objectives. Drawing inspiration from successful areas like the Caribbean, Pacific, and southwest Indian Ocean towns, is recommended for a successful transition into the BE. Regional cooperation is needed to address the Gulf of Guinea's insecurity through maritime security, environmental protection, joint exploration, and marine-based product research and development.

The Blue Economy is a relatively new concept that aims to protect the world's ocean resources by promoting economic growth, social inclusion, and the preservation/improvement of livelihoods while ensuring environmental sustainability. This concept is consistent with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea agreements, which define nations' rights and responsibilities in their use of the world's oceans. Sustainable development and improved livelihoods are guaranteed with the proper application of the Blue Economy. Efforts to transition to the Blue Economy have been welcomed in Africa, with examples from the Southwest Indian Ocean. However, such strategies do not exist in the Gulf of Guinea, resulting in an inability to capitalize on economic marine opportunities and address the causes and risks of economic degradation and natural capital loss. Transitioning to the Blue Economy in the Gulf of Guinea faces challenges such as maritime security and safety, environmental degradation, and uncontrolled anthropogenic activities. This necessitates strategies to integrate the Blue Economy into the Gulf trade strategies. This will entail developing policies to increase profits and gains from existing blue industries and projects; directing policies, incentives, and regional collaboration toward emerging sectors of the BE; and cultivating blue-based regional value chains.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

We thank Adefola Deborah Ojomo (Ph.D. student of the Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Federal University of Technology Akure, Nigeria) and Favor Moyosore Adeleye (Research Assistant at GISPLUS Technologies, Akure, Nigeria), who contributed to the initial data collection for the content analysis and the management and organization of the data which made it possible to analyze the several documents employed in this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

ADF (2022). Ghana Drafts Plan to Protect Blue Economy. Africa Defense Forum. Available online at: https://adf-magazine.com/2022/09/ghana-drafts-plan-to-protect-blue-economy/ (accessed May 24, 2023).

Adibe, R., Nwangwu, C., Ezirim, G. E., and Egonu, N. (2018). Energy hegemony and maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea: rethinking the regional trans-border cooperation approach. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 46, 336–346. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2018.1484350

African Development Bank Group (2022). Equatorial Guinea - Combined Country Strategy Paper (CSP) 2018-2022 Midterm Review and 2021 Portfolio Performance Review (CPPR) Report. [online] https://www.afdb.org. Available online at: https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/equatorial-guinea-combined-country-strategypaper-csp-2018-2022-midterm-review-and-2021-portfolio-performance-review-cpprreport (accessed June 30, 2023).

Agbota, S. (2019). Global Blue Economy: Nigeria Not Listed Among Africa's 15th Maritime Tourism Nations. The Sun Nigeria. Available online at: https://www.sunnewsonline.com/global-blue-economy-nigeria-not-listed-among-africas-15th-maritime-tourism-nations (accessed October 2, 2022).

Agence Beninoise pour l'Environnement (2010). Benin - Community-Based Coastal and Marine Biodiversity Management Project: Environmental Assessment. World Bank. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available online at: https://documents.worldbank.org/pt/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/848941468201571023/benin-community-based-coastal-and-marine-biodiversity-management-project (accessed May 24, 2023).

Akita, L. G., Laudien, J., and Nyarko, E. (2020). Geochemical contamination in the Densu Estuary, Gulf of Guinea, Ghana. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 42530–42555. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-10035-4

Alegre, M.-C. C. (2009). Towards a National Ocean Policy in Sao Tome and Principe. Sao Tome: United Nations, 1–76.

Ali, K. E., Kouadio, K. Y., Zahiri, E.-P., Aman, A., Assamoi, A. P., and Bourles, B. (2011). Influence of the gulf of guinea coastal and equatorial upwellings on the precipitations along its northern coasts during the boreal summer period. Asian J. Appl. Sci. 4, 271–285. doi: 10.3923/ajaps.2011.271.285

Allison, E., Kurien, J., Ota, Y., Adhuri, D., Bavinck, J., and Cisneros-Montemayor, A. (2020). The Human Relationship with Our Ocean Planet. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

AMMCO (2021). African Marine Mammal Conservation Organization (AMMCO) is Working to make Central Africa's Coastal and aquatic Environments Safe for Marine Wildlife. Available online at: https://www.synchronicityearth.org/partner/african-marine-mammal-conservation-organization-ammco/?fwp_programme=congo-basin (accessed April 16, 2023).

Angop (2022). Angola with Potential for Blue Economy. Available online at: https://www.angop.ao/en/noticias/economia/angola-tem-um-grande-potencial-para-a-economia-azul-josefa-sacko/ (accessed May 29, 2023).

Atakpa, S. D. (2017). Blue Economy Legal and Institutional Frameworks: The Nigerian Challenge. Available online at: https://www.google.com/amp/s/shipsandports.com.ng/blue-economy-legal-and-institutional-frameworks-the-nigerian-challenge/amp/ (accessed September 4, 2022).

Axon, S., Bertana, A., Graziano, M., Cross, E., Smith, A., Axon, K., and Wakefield, A. (2022). The US blue new deal: what does it mean for just transitions, sustainability, and resilience of the blue economy? The Geograph. J. 189, 12434. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12434

Ayissi, I., Makoge, R. E., Nack, J., Nyeck, N., Mpeck, M. L., and Kamga, A. (2018). Characterization of marine artisanal fisheries and the impact of by-catch on marine faunal in southern cameroon (West Africa). HSOA J. Aquac. Fisher. 3, 1–6.

Bauler, T., and Pipart, N. (2013). Ecosystem Services in Belgian Environmental Policy Making. Ecosystem Services. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 121–133.

Bax, N., Novaglio, C., Maxwell, K. H., Meyers, K., McCann, J., and Jennings, S. (2021). Ocean resource use: building the coastal blue economy. Rev. Fish Biol. Fisheries 32, 1–9. doi: 10.22541/au.160391057.79751584/v1

Bennett, N. J., Blythe, J., White, C., and Campero, C. (2020). Blue Growth and Blue Justice. IOF Working Paper #2020 - 02. Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia.

Bennett, N. J., Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Blythe, J., Silver, J. J., Singh, G., and Andrews, N. (2019). Towards a sustainable and equitable blue economy. Nat. Sust. 2, 12. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0404-1

Bertarelli, D. (2020). Developing a Vibrant Blue Economy is Feasible, But We Need to Collaborate | UNCTAD. Available online at: https://unctad.org/news/developing-vibrant-blue-economy-feasible-we-need-collaborate (accessed September 29, 2022).

Blythe, J. L., Gill, D. A., Claudet, J., Bennett, N. J., Gurney, G. G., Baggio, J. A., et al. (2023). Blue justice: a review of emerging scholarship and resistance movements. Prisms Coast. Futur. 1, e15. doi: 10.1017/cft.2023.4

Bolaky, B. (2020). Operationalising Blue Economy in Africa: The case of South West Indian Ocean. Delhi: Observer Research Foundation.

Boonstra, W. J., Valman, M., and Björkvik, E. (2018). A sea of many colours – how relevant is blue growth for capture fisheries in the global north, and vice versa? Marine Policy 87, 340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.09.007

Brito, B. R. (2021). Conserving Marine Life in Sao Tome and Principe: Concerted Actions with Agenda 2030. Life Below Water: Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Cham: Springer, 1–16.

Childs, J. R., and Hicks, C. C. (2019). Securing the blue: political ecologies of the blue economy in Africa. J. Poli. Ecol. 26, 323–340. doi: 10.2458/v26i1.23162

De Ceita, P. A. R. (2020). An Assessment of the Impact of Maritime (In)security in the Gulf of Guinea: Special Emphasis on Sao Tome and Principe (M.Sc. Thesis), 1–64. Available online at: https://commons.wmu.se/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2382&context=all_dissertations

Denton, G. L., and Harris, J. R. (2019). Maritime piracy, military capacity, and institutions in the gulf of guinea. Terror. Polit. Viol. 34, 1–27. doi: 10.1080/09546553.2019.1659783

Directorate General for West Africa (2021). Bénin - Combined Report on the Mid-Term Review of the 2017-2021 Country Strategy Paper and the 2019 Country Portfolio Performance Review. African Development Bank - Building Today, a Better Africa Tomorrow. Available online at: https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/benin-combined-report-mid-term-review-2017-2021-country-strategy-paper-and-2019-country-portfolio-performance-review (accessed May 9, 2023).

Doherty, P. (2023). Protecting the threatened sharks and rays of the Republic of Congo. Save Our Seas Foundation. Available online at: https://saveourseas.com/project/protecting-the-threatened-sharks-and-rays-of-the-republic-of-congo (accessed May 21, 2023).

Dossavi, A. R. (2023). Togo: A Five-Year Plan to Develop the Blue Economy is in the Pipeline. Available online at: https://www.togofirst.com/en/economic-governance/1602-11414-togo-a-five-year-plan-to-develop-the-blue-economy-is-in-the-pipeline (accessed June 9, 2023).

Early Career Ocean Professional (2022). Togo - ECOP Programme. [online] Ecopdecade.org. Available online at: https://www.ecopdecade.org/togo/ (accessed May 20, 2023).

Economic Commission for Africa (2014). Unlocking the Full Potential of the Blue Economy: Are African Small Island Developing States Ready to Embrace the Opportunities? Addis Ababa: UN ECA, 1–33.

Ehlers, P. (2016). Blue growth and ocean governance—How to balance the use and the protection of the seas. WMU J. Mar. Affairs. 15, 187–203. doi: 10.1007/s13437-016-0104-x

Eikeset, A. M., Mazzarella, A. B., Davíð*sdóttir, B., Klinger, D. H., Levin, S. A., and Rovenskaya, E. (2018). What is blue growth? The semantics of ‘Sustainable Development' of marine environments. Marine Policy 87, 177–179. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.10.019

Essen, E. (2020). Blue Economy. The New Frontier for Marine Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development. Munich: GRINerlag, 1–36.

European Union (2021). EU Maritime Security Factsheet: The Gulf of Guinea | EEAS. Available online at: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eu-maritime-security-factsheet-gulf-guinea (accessed May 17, 2023).

Failler, P., Karani, P., Gilau, A. M., Hamukuaya, H., and Diop, S. (2020). Africa Blue Economy Strategy - Implementation Plan 2021-2025. [online] University of Portsmouth; The African Union Inter-African Bureau for Animal Resources. Available online at: https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/en/publications/africa-blue-economy-strategy-implementation-plan-2021-2025 (accessed October 2, 2022).

FAO (2023). Sao Tome and Principe. HandInHand. Available online at: https://www.fao.org/hand-in-hand/investment-forum-2022/sao-tome-and-principe/en#:~:text=The%20Government%20of%20Sao%20Tome (accessed May 19, 2023).

Fauna-Flora (2023). Protecting the Unique and Threatened Seas and Forests of São Tomé and Príncipe. Available online at: https://www.fauna-flora.org/projects/supporting-conservation-programmes-principe/ (accessed June 1,2023).

Findlay, K. (2018). Operation Phakisa and Unlocking South Africa's Ocean Economy. J. Ind. Ocean Reg. 14, 248–254. doi: 10.1080/19480881.2018.1475857

Finke, G., Gee, K., Gxaba, T., Sorgenfrei, R., Russo, V., Pinto, D., et al. (2020). Marine spatial planning in the benguela current large marine ecosystem. Environ. Dev. 36, 100569–100580. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2020.100569

Fonseca, V. (2021). Making Sense of an Experimental Portfolio in Blue Economy in Cabo Verde | United Nations Development Programme. UNDP. Available online at: https://www.undp.org/acceleratorlabs/blog/making-sense-experimental-portfolio-blue-economy-cabo-verde (accessed September 25, 2022).

Gabon Vert (2023). Gabon Bleu. Available online at: https://gabonvert.com/gabon-bleu/ (accessed May 28, 2023).

Gay, D. (2022). South-South Cooperation in Advancing Sustainable Development and Achieving the Transformative Recovery of the Least Developed Countries. New York, NY: UN-OHRLLS, 1–58.

Geneletti, D., and Zardo, L. (2016). Ecosystem-based adaptation in cities: an analysis of European urban climate adaptation plans. Land Use Policy 50, 38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.09.003

Ghosh, D. (2021). Gulf Of Guinea. WorldAtlas. Available online at: https://www.worldatlas.com/seas/gulf-of-guinea.html (accessed September 25, 2022).

Ginga, D. (2020). The importance of integrated ocean governance for a blue economy in angola. Perspectivas – J. Polit. Sci. 23, 22–35. doi: 10.21814/perspectivas.3058

Giulini, L. (2021). The Gulf of Guinea's Blue Economy: from Oil through Fish to People. The Organization for World Peace. Available online at: http://theowp.org/the-gulf-of-guineas-blue-economy-from-oil-through-fish-to-people/ (accessed September 17, 2022).

Golden, J. S., Virdin, J., Nowacek, D., Halpin, P., Bennear, L., and Patil, P. G. (2017). Making sure the blue economy is green. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 16–21. doi: 10.1038/s41559-016-0017

Government of Sierra Leone. (2021). Updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). Freetown: UNFCCC.

Grynspan, R. (2021). New Opportunities for Accelerating Pan-African Trade. UNCTAD. Available online at: https://unctad.org/news/blog-new-opportunities-accelerating-pan-african-trade (accessed September 28, 2022).

Haimbala, T. (2019). Sustainable Growth through Value Chain Development in the Blue Economy: a Case Study of the Port of Walvis Bay. [MSc Thesis]. Available online at: https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/1123?utm_source=commons.wmu.se%2Fall_dissertations%2F1123andutm_medium=PDFandutm_campaign=PDFCoverPages (accessed March 13, 2019).

Hamisu, A. H. (2019). A study of Nigeria's Blue Economy Potential With Particular Reference to the Oil and Gas Sector. [MSc Thesis]. Available online at: https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/1234?utm_source=commons.wmu.se%2Fall_dissertations%2F1234andutm_medium=PDFandutm_campaign=PDFCoverPages (accessed August 1, 2022).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Beal, D., Chaudhry, T., Elhaj, H., Abdullat, A., Etessy, P., and Smits, M. (2015). Reviving the Ocean Economy: The Case for Action - 2015. Geneva: WWF International, 1–60.

Howard, B. C. (2018). Blue growth: stakeholder perspectives. Marine Policy 87, 375–377. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.11.002

Ibe, C. A., and Sherman, K. E. (2002). The gulf of guinea large marine ecosystem project: turning challenges into achievements. Elsevier eBooks 11, 27–39. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0461(02)80025-8

Ikein, A. (2009). The potential power of west african oil to the economics and energy security interest of euro-america in the 21st century. J. Sust. Dev. Africa 10, 540–556.

Independent Development Evaluation (2022). Equatorial Guinea: 2018-2022 Country Strategy Paper Mid-Term Review Validation Note. Available online at: https://idev.afdbnet.com/sites/default/files/documents/files/Equatorial%20Guinea%202018-2022%20Country%20Strategy%20Paper%20MTR%20Validation%20Note%20%28EN%29_0.pdf (accessed May 26, 2023).

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (2021). IOC Sub Commission for Africa and the Adjacent Island States - Sierra Leone. Available online at: https://ioc-africa.org/ocean-governance-and-legislation/33-governance-and-legislation/106-siera-leone.html (accessed June 1, 2023).

International Union for Conservation of Nature (2019). Guinea-Bissau | IUCN. Available online at: https://www.iucn.org/our-work/topic/ecosystem-restoration/restoration-initiative/projects/guinea-bissau (accessed May 14, 2023).

Karani, P., Failler, P., Gilau, A. M., Ndende, M., and Diop, S. T. (2022). Africa blue economy strategies integrated in planning to achieve sustainable development at national and regional economic communities (RECs). J. Sust. Res. 4, 3.

Kathijotes, N. (2013). Keynote: blue economy - environmental and behavioural aspects towards sustainable coastal development. Procedia – Soc. Behav. Sci. 101, 7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.173

Kevin, W., Abubakar Ali, S.hidiki, and Tchamba, M. N. (2022). Coastal risk management in a context of climate change: a case study of kribi town of the south region of Cameroon. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 10, 111–124. doi: 10.4236/gep.2022.105009

Kleverlaan, E. (2023). Guidance Document on Development of National Action Plan on Sea-Based Marine Plastic Litter. Available online at: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/PartnershipsProjects/Documents/GloLitter/Guidance%20Document%20on%20Development%20of%20National%20Action%20Plan%20on%20Sea-Based%20Marine%20Plastic%20Litter.pdf (accessed June 9, 2023).

Klinger, D. H., Maria Eikeset, A., Davíð*sdóttir, B., Winter, A.-M., and Watson, J. R. (2018). The mechanics of blue growth: Management of oceanic natural resource use with multiple, interacting sectors. Marine Policy. 87, 356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.09.025

Lee, K. H., Noh, J., and Khim, J. S. (2020). The blue economy and the united nations' sustainable development goals: challenges and opportunities. Environ. Int. 137, 105528. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105528

Lee, Y. F., Anukoonwattaka, W., Taylor-Strauss, H., and Duval, Y. (2022). Regional Cooperation and Integration in Support of a Sustainable Development-Oriented Multilateral Trading System. ESCAP. Available online at: https://www.unescap.org/kp/2022/regional-cooperation-and-integration-support-sustainable-development-oriented-multilateral (accessed April 16, 2023).

Liberia Project Dashboard (2019). Liberia Project Dashboard. Available online at: https://www.liberiaprojects.org/activities/1137 (accessed June 5, 2023).

Lighthouse Foundation. (2021). Ghana: Coastal and Marine Conservation Drive Project. Available online at: https://lighthouse-foundation.org/en/Ghana-Coastal-and-Marine-Conservation-Drive-Project.html (accessed May 16, 2023).

Lindley, J. (2021). Maritime Safety and Security. The Blue Economy in Sub-Saharan Africa. London: Routledge, 1–14.

Lopes, C. (2016). Africa's Blue Economy: An opportunity not to be missed. Development Matters. Available online at: https://oecd-development-matters.org/2016/06/07/africas-blue-economy-an-opportunity-not-to-be-missed/ (accessed June 1, 2023).

Mami Wata. (2018a). Benin Pilot Project – Context. The Mami Wata Project. Available online at: https://mamiwataproject.org/pilot-projects/pilot-project-benin-context/ (accessed May 18, 2023).

Mami Wata. (2018b). Côte D'Ivoire Pilot Project – Context. The Mami Wata Project. Available online at: https://mamiwataproject.org/pilot-projects/pilot-projects-cotedivoire-context/ (accessed May 15, 2023).

Mami Wata. (2018c). Ghana Pilot Project – Context. The Mami Wata Project. Available online at: https://mamiwataproject.org/pilot-projects/pilot-projects-ghana-context/ (accessed May 16, 2023).

Martínez-Vázquez, R. M., Milán-García, J., and de Pablo Valenciano, J. (2021). Challenges of the Blue Economy: evidence and research trends. Environ. Sci. Europe 33, 1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12302-021-00502-1

Metcalfe, K., White, L., Lee, M. E., Fay, J. M., Abitsi, G., Parnell, R. J., et al. (2022). Fulfilling global marine commitments; lessons learned from Gabon. Conserv. Letters 15, e12872. doi: 10.1111/conl.12872

Mohan, P., Strobl, E., and Watson, P. (2021). Innovation, market failures and policy implications of KIBS firms: the case of Trinidad and Tobago's oil and gas sector. Energ. Policy 153, p.112250. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112250

Mold, A. (2022). The Economic Significance of intra-African Trade Getting the Narrative Right Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings. [online] Africa Growth Initiative - Brookings, 1–31. Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2022/08/Economic-significance_of_intra-African_trade.pdf (accessed September 29, 2022).

Morcos, P. (2021). A Transatlantic Approach to Address Growing Maritime Insecurity in the Gulf of Guinea. Available online at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/transatlantic-approach-address-growing-maritime-insecurity-gulf-guinea (accessed October 6, 2022).

MSPglobal. (2022). Togo – MSPGLOBAL2030. mspglobal2030. Available online at: https://www.mspglobal2030.org/msp-roadmap/msp-around-the-world/africa/togo/ (accessed April 11, 2023).

Nash, K. L., Cvitanovic, C., Fulton, E. A., Halpern, B. S., Milner-Gulland, E. J., and Watson, R. A. (2017). Planetary boundaries for a blue planet. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 11. 017-0319-z doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0319-z

Nigeria Conservation Foundation (2020). NCF Nigeria. Available online at: https://www.ncfnigeria.org/marine-coastline (accessed May 26, 2023).

Observatory of Economic Complexity (2020). Angola (AGO) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners. Available online at: https://oec.world/en/profile/country/ago (accessed July 23, 2020).

Okafor-Yarwood, I., Pigeon, M., Amling, A., Ridgway, C., Adewumi, I., and Joubert, L. (2020). Stable seas: gulf of guinea. Stable Seas 2, 1–124. doi: 10.18289/OEF.2020.043

Olteanu, A., and Stinga, V. (2019). The economic impact of the blue economy. LUMEN Proc. 7, 190–203. doi: 10.18662/lumproc.111

Patil, P. G., Virdin, J., Colgan, C. S., Hussain, M. G., Failler, P., and Vegh, T. (2018). Toward a Blue Economy: A Pathway for Sustainable Growth in Bangladesh. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Popoola, O. O. (2012). Sea Level Rise and Sustainability of the Nigerian Coastal Zone. [Ph.D. Thesis]. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/907 (accessed June 7, 2022).

Popoola, O. O. (2014). Vulnerability of the Nigerian coast to inundation consequent on sea level rise. J. Eng. Environ. Stu. 5, 25–38.

Popoola, O. O. (2021). Spatio-temporal assessment of modifications to coastal marshes along the deltaic coast of Nigeria. J. Sust. Technol. 11, 165–180.

Popoola, O. O. (2022). Spatio-temporal assessment of shoreline changes and management of the transgressive mud coast, Nigeria. Eur. Sci. J. 18, 99–127. doi: 10.19044/esj.2022.v18n20p99

Popoola, O. O., Olajuyigbe, A. E., and Rowland, O. E. (2019). Assessment of the implications of biodiversity change in the coastal area of Ondo State, Nigeria. J. Sust. Technol. 10, 53–67.

Pretorius, R., and Henwood, R. (2019). Governing Africa's blue economy: the protection and utilisation of the continent's blue spaces. Stu. Univ. Babe? 64, 119–148. doi: 10.24193/subbeuropaea.2019.2.05

Purvis, M. T. (2015). Seychelles Blue Economy Strategy. Island Studies: Indian Ocean. Victoria, Seychelles: University of Seychelles, 14–19.

Quak, E. (2019). How Losing Access to Concessional Finance Affects Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Leeds: UKaid.

Roy, A. (2019). Blue Economy in the Indian Ocean: Governance Perspectives for Sustainable Development in the Region. ORF Occasional Paper No. 181. Available online at: https://www.orfonline.org/wpcontent/uploads/2019/01/ORF_Occasional_Paper_181_Blue_Economy.pdf (accessed October 8, 2022).

Rustomjee, C. (2017). Operationalizing the Blue Economy in Small States: Lessons from the Early Movers. Waterloo: Centre for International Governance Innovation.

Saghir, J. (2016). Africa Leads in the Pursuit of a Sustainable Ocean Economy. Available online at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/africa-leads-pursuit-sustainable-ocean-economy (accessed July, 18, 2022).

Sandifer, P. A., and Sutton-Grier, A. E. (2014). Connecting stressors, ocean ecosystem services, and human health. Nat. Res. Forum 38, 157–167. doi: 10.1111/1477-8947.12047

Sartre, P. (2014). Responding to Insecurity in the Gulf of Guinea. New York, NY: International Peace Institute.

Science Daily (2022). Gabon Provides Blueprint for Protecting Oceans. ScienceDaily. Available online at: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2022/02/220208105227.htm (accessed October 1, 2022).

Signé, L. (2022). Understanding the African Continental Free Trade Area and How the US Can Promote Its Success. Available online at: https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.brookings.edu/testimony/understanding-the-african-continental-free-trade-area-and-how-the-US (accessed October 4, 2022).

Smith-Godfrey, S. (2016). Defining the blue economy. Maritime Aff. J. Nat. Mar. Foundation India 12, 58–64. doi: 10.1080/09733159.2016.1175131

Spalding, M. J. (2016). The new blue economy: the future of sustainability. J. Ocean Coastal Econ. 2, 2. doi: 10.15351/2373-8456.1052

Teh, L. C. L., and Sumaila, U. R. (2011). Contribution of marine fisheries to worldwide employment. Fish Fisheries 14, 77–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2011.00450.x

The Global Economy (2022). Global Economy, World Economy | TheGlobalEconomy.com. Available online at: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com (accessed September 26, 2022).

The Small-Scale Initiatives Program. (2014). Marine Turtle Conservation Project in Côte d'Ivoire. UICN. Available online at: https://www.programmeppi.org/en/projects/projet-de-conservation-de-tortues-marines-en-cote-divoire (accessed June 5, 2023).

Ticha, A. A. (2015). Cameroon: Capitalize on Blue Economy to Cash in on Africa's Free Trade Area. Yaounde: Fisheries Committee for the West Central Gulf of Guinea.

Trew, B. T., Grantham, H. S., Barrientos, C., Collins, T., Doherty, P. D., and Formia, A. (2019). Using cumulative impact mapping to prioritize marine conservation efforts in equatorial guinea. Front. Marine Sci. 6, 717. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00717

Ugwueze, M. I., and Asua, S. A. (2021). Business at risk: understanding threats to informal maritime transportation system in the South-South, Nigeria. J. Transp. Secur. 14, 7. doi: 10.1007/s12198-021-00233-7