- 1School of Social Sciences, Södertörn University, Huddinge, Sweden

- 2Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall, Sweden

The Swedish Liberal Party chose a new leader in 2019. It was, in some ways, typical of leader selection in Sweden. It featured an elaborate, institutionalised and yet only semi-public form of “precursory delegation,” in which aspiring leaders are filtered by a “steering agent” on behalf of the party's main power centres. In other ways, though, the process was unusually conflictual and produced an unexpected result, which had considerable consequences for the party and for Swedish politics. Moreover, the selection involved the breakdown of a long-established procedure for leader selection in the party. We seek to explain this deviant case. We emphasise an unexpected cascade of decisions by regional party branches to hold membership ballots on the leadership candidates. This event, we argue, was critical for the outcome. We also suggest a causal mechanism, a shifting perception of procedural legitimacy, that facilitated the outcome—a mechanism that could be useful in understanding leader selection and moments of party change more generally.

Introduction

Political parties change their leaders every so often. Sometimes these transitions are predictable, consensual and engender only modest political consequences. The Swedish Liberal Party's selection of a new leader in 2019 was neither predictable nor consensual. It also had considerable political significance—for the party's own orientation, for the party system and, potentially, for leader selection in other Swedish parties, too. These features alone make the case significant. Perhaps even more intriguing, however, are the events and processes that preceded the selection and the mechanisms through which competition was pursued and change facilitated. Something unusual in Swedish politics unfolded.

Much has changed in European party organisation in recent decades. Leaders tend to be selected by a larger set of people than previously. A party's entire membership, or even its supporters in the wider electorate, are now often directly involved, as can be seen in Britain, Germany, Italy and various other countries. Swedish parties had been resistant to such changes (Madestam, 2014; Aylott and Bolin, 2021b). By 2019, a new party leader in Sweden was still generally selected by a few hundred delegates to the party congress—insofar as “selection” can mean much when there is only one candidate for congress delegates to vote for, which was what usually happened. The more important part of a Swedish leader selection would have occurred earlier, in a fluid, complex, partly secretive process of signalling and bargaining that was nevertheless regulated in the party statutes. The Liberal selection of 2019 ostensibly followed this procedure. Dig just a little deeper into the case, however, and it becomes clear that events prior to the decision of the party congress had slipped beyond the control of the institutions that were supposed to steer the appointment.

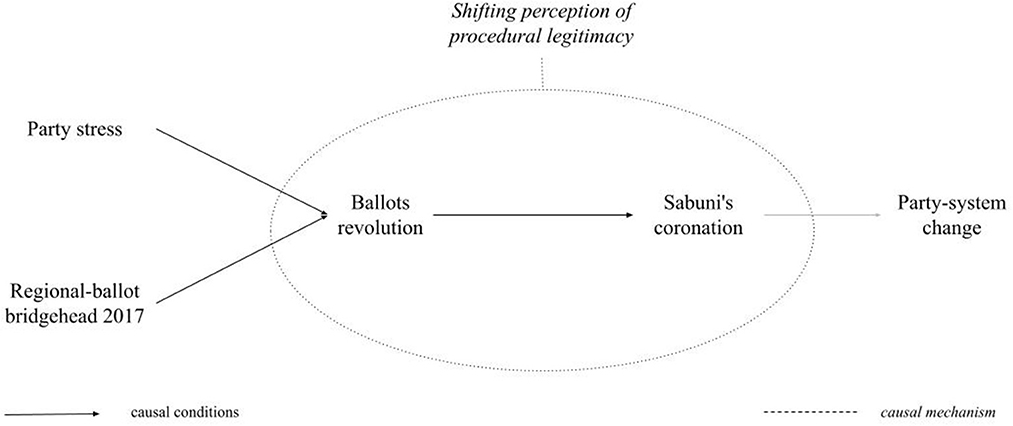

In this article, our objective is to account for what happened in the case and explain the unexpected, controversial outcome of the selection, which had considerable, substantive consequences for Swedish politics. For this purpose, we use a particular framework for analysing party leader selection and a particular explanatory approach. We envisage a chain of events, a process. One event—a cascade of decisions by regional party branches to ballot members about leadership candidates—can be understood as “critical” in changing the path that the process was expected to follow and bringing about the selection of Nyamko Sabuni as the Liberals' new leader. We thus focus largely on this critical event. We rely mainly on qualitative data, collected from media reports and interviews with well-placed individuals within the party.

The case had an additional significance, moreover. A second objective is to analyse the collapse of a selection procedure that was long-established, both in the Liberals and in Swedish parties more generally. It was superseded by a more “inclusive” procedure, in which individual party members played a much more direct role.

Such change has been seen frequently in Europe. Yet it is far from inevitable—as evidenced by the fact that no Swedish party had previously gone down this route. We remain dissatisfied by the sort of causal explanation that relies only on the identification of correlation between variables. In our view, some specific causal factor, or combination of factors, is required to induce transition in any particular case. In our account, we identify a causal mechanism that we call a shifting perception of procedural legitimacy. This, we argue, facilitated the causal effect. We suggest that our findings can travel to other contexts and that the mechanism might well contribute to change in other cases, too.

The rest of the article develops as follows. First, we elaborate on the theory and concepts that we use, plus the logic of our case selection. Then we sketch the background to the Liberal selection of 2019 and the party's customary procedure. We trace the emergence of the leadership contenders and the erosion of the prevailing intra-party power structure. Finally, we conclude.

Theory, concepts and case selection

In this section, we address the theory and method in our study.

Selecting party leaders: The case and its context

When studying leader selection, the selectorate—the section or organ of the party with the formal right to choose the leader—is the obvious place to start. We know that, in European parties, the selectorate has tended towards greater inclusivity. Individual members, and even sympathisers beyond the party membership, have been increasingly allowed to participate in decision-making, including the selection of the leader. The selectorate's decisions have also become less contested, with the winning candidate doing so more easily (LeDuc, 2001; Pilet and Cross, 2014; Cross and Pilet, 2015; Sandri et al., 2015; also Kosiara-Pedersen et al., 2017, pp. 237–243; Scarrow, 2015, pp. 128–153).

However, it has been increasingly acknowledged that what happens prior to the formal vote is at least as important as the role of the selectorate (for instance, Pilet and Wauters, 2014). Leader selection can thus be analysed as a three-phase process (Bolin and Aylott, 2021a). The first phase, gatekeeping, addresses the formal rules that restrict the range of candidates who are eligible to run. The second phase, preparation, is when aspiring leaders and intra-party power centres jostle with each other over candidacies. The final phase, decision, relates to the selectorate. (The first two phases need not be strictly sequenced. They may well overlap).

Let us turn to our case. Its progression became increasingly unusual, and this is where its main value to our contribution lies. The unusualness of the procedure was not that it concluded in the “coronation” (Kenig, 2009) of a new leader, in which the selectorate rubber-stamped a single remaining candidate. Nor was it so remarkable that the winner was initially unfancied. Upsets in party-leader selection are not that rare. On the other hand, the surprise outcome did facilitate a major change in the Liberals' political orientation, which we summarise in a postscript in the concluding section. That was the substantive consequence that justifies our focus on this case.

What lends the case its extra significance, moreover, was the way in which the selection procedure ended up deviating considerably from the party's norm—and, indeed, from the Swedish norm. True, such a step towards inclusivity was quite familiar in other European parties. That allows us to classify this case as deviant (Gerring, 2017, pp. 73–79; Mahoney, 2021, p. 309). The distribution of intra-party power that was reflected in the Liberals' customary method of selecting a leader became disrupted in 2019.

Change in party organisation

Our case can also be classified as one of party change—albeit, in the end, change of a rather ephemeral kind. Party change, as Harmel and Janda (1994, p. 261) asserted, does not just happen. So what makes it happen?

One batch of possible causal factors might be found in what Harmel (2002, pp. 122–124) called the “system-level trends approach.” Arguably, the general move in party organisation towards more inclusive leader-selection procedures could have been a factor in explaining our outcome. Put simply, our case could have been influenced by others. Following the causal chain backwards, we might also point to certain driving forces behind the trend: principally, the decline in party membership over the last four or five decades (Biezen et al., 2012), possibly combined with parties' withdrawal from civil society in search of a more comfortable berth within the protective embrace of the state (Mair, 2006, 2008; also Ignazi, 2020, pp. 10-11).

Superficially, it seems likely that dissatisfied party members have actively demanded a bigger say in important facets of intra-party life, such as the selection of leaders—as occurred, for instance, in the British Conservative Party (Quinn, 2012, p. 97). More common, though, is the suggestion that, because members are useful to parties in various ways, and because the fall in their numbers posed a problem for party elites, the elites sought to re-enthuse remaining members, and perhaps attract (back) non-members, by offering them more decision-making involvement (Gauja, 2017, pp. 30–39; Katz, 2013; also Achury et al., 2020). In the 1990s, Scarrow (1999, pp. 347–349, 353–356) described changes in the big German parties as being implemented largely top-down, as their leaderships sought to respond to the success of the Greens (see also Gauja, 2017, pp. 148-157). Moreover, this idea of elite-initiated change is compatible with the “fake-democratisation thesis” (Aylott and Bolin, 2021a, pp. 7–8). Some scholars (Katz and Mair, 2018, pp. 64–77; Mair, 1997, pp. 149–150; Mair, 2013) have suggested that greater inclusiveness actually masks the consolidation of power among existing party elites. This is because the likeliest source of intra-party opposition to the elites, the mid-levels activists, are bypassed if decisions are taken directly by the members rather than through representative structures.

Yet the supposed connection between greater intra-party inclusivity, whoever initiates it, and membership decline does not apply everywhere. While Swedish parties had certainly lost members, they had not responded, by 2019, by throwing open their internal decision-making to members, let alone non-members. As we will see, there was occasional discussion within the party about greater membership involvement in decision-making. Yet there was little to suggest, at the start of the year, that inclusivity was about to make some sort of breakthrough in the party.

Our contention, then, is that our case is better aligned with Harmel's (2002, pp. 125–127) “discrete change approach.” At the risk of arriving at less generalisable conclusions, scholars working from this perspective search for the interaction of contingent environmental and internal factors, operating at levels within and beyond the party itself, in a particular case (Barnea and Rahat, 2007; Gauja, 2017, pp. 8–15; Panebianco, 1988).

What might such factors be? Harmel and Janda (1994, pp. 265–266) suggest that some sort of “shock”—usually an unpleasant one—is required to stimulate change. Exactly what constitutes a shock depends on the party in question. It might be an electoral defeat; but it might be some other development, either internal or external. At the same time, we acknowledge the desirability, especially in an intensive case study, of illuminating the connection between causes and outcome. Certain individuals within a party have to make an active decision about organisational change; and this requires that they deem it the right thing to do. Their arriving at that conclusion must be part of the causal process (Gauja, 2017, pp. 39–42; Harmel, 2002, p. 128).

Our analytical approach

Our analysis proposes causal association based on set-theoretical principles. Association involves a condition, such as a certain event, being necessary or sufficient to bring about a subsequent outcome, which may itself have causal significance for further events. Causal status is proposed on the basis of empirical evidence and counterfactual reasoning. The more necessary and sufficient a cause, the more causally important it becomes in the overall explanation. If an outcome is unexpected, and if an event is to be understood as critical in the explanation of that outcome, the event must also be unexpected (contingent) (García-Montoya and Mahoney, 2020, pp. 10–16).

Furthermore, this cause must have “spatiotemporal contact” with the outcome, which refers to “intermediary or connecting events,” or “linking mechanisms” (Mahoney, 2021, p. 97). We understand a causal mechanism as a pattern of human thought or action, a configuration of separable components. It possesses, at least to some degree, the quality of portability between empirical cases. Mechanisms facilitate the transmission of causal effects (Backlund, 2020, pp. 76–81; Hedström and Ylikoski, 2010, p. 52). A norm, a “shared expectation...about how people ought to behave” (Mahoney, 2021, p. 322), may form part of a mechanism.

To identify causal relations in our case, we employ an inductive style of process tracing to identify salient mechanisms (Blatter and Haverland, 2012, pp. 79–83). We have scoured contemporary media reports of the Liberals' selection. We distinguish between two categories of media reports and articles. Those in which the author's identity is central to its significance, such as an op-ed column, or in which investigative or analytical effort has been invested by the author, are treated as journal articles and are included in the reference list at the end. News reports that simply record events or remarks are by contrast, are listed separately and chronologically in an appendix. In the main text, references to this latter category of sources include the name of the publication, often abbreviated, and the date of (usually online) publication. We have also undertaken interviews with key actors within the party (see the list of interviewees at the end of this article). We seek, in particular, to establish sequences of events and to explore the motives and intentions of centrally involved actors.

Analysing the case

We start by sketching the background to the case. Then we describe the Liberals' method of selection.

Background: Party-system turbulence and the “January agreement”

The Liberals reunited into a single organisation in 1934. Despite being one of the smaller Swedish parties, it has enjoyed several spells in government, nearly all alongside others in a centre-right bloc (Bolin, 2019, p. 62). In 2004, that bloc hardened into the “Alliance for Sweden,” which then won consecutive terms in government. By 2017, however, underwhelming electoral performances prompted speculation about the position of the Liberal leader, Jan Björklund. In 2017, he was subject to an abortive challenge by a parliamentarian from the party's left wing.

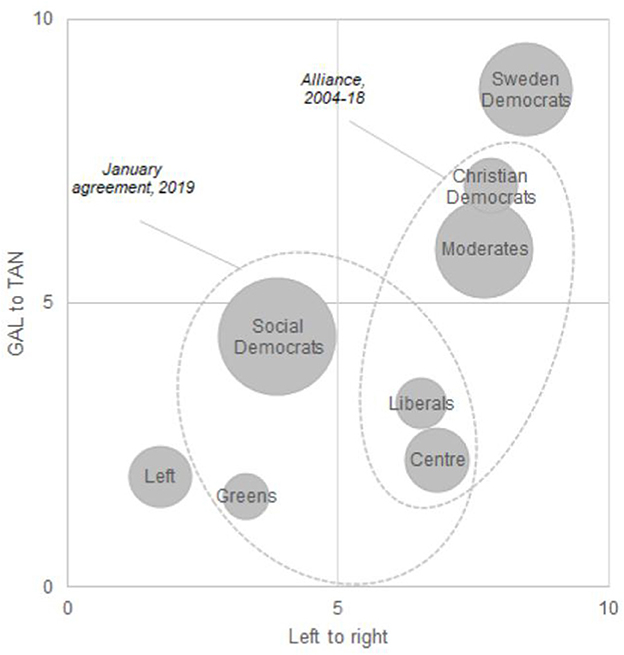

After the national election of autumn 2018, the Alliance split. Half of it wanted to retake power with parliamentary support from the radical-right Sweden Democrats. Its other two parties, the Centre Party and the Liberals, refused. Björklund, for one, had long ruled out any deal with the Sweden Democrats, and in very personal, and thus credible, terms (TV4 12 June 2017). After long negotiations (Teorell et al., 2020), the Centre and the Liberals turned leftwards. They did not join the incumbent coalition government, but they agreed to support its continuation in return for policy concessions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Swedish party system, 2019. Source: Bakker et al., 2020.

Observers saw this “January agreement” as being quite favourable to the defecting Alliance parties (Aylott and Bolin, 2019, pp. 1512–1513). Nevertheless, Liberals had mixed feelings. After a televised debate, a third of the party council, in which its regional branches are represented, voted against the deal (SvD 14 January). So did eight of the party's 20 parliamentarians (Eriksson, 2019).

By early 2019, then, the Liberals were in difficulty. The Alliance was dead. There were doubts about the January agreement. Voters seemed unimpressed by it. The Liberals' support was at its lowest level for many years and well below the 4 per cent threshold for parliamentary representation (MäMä, undated). Björklund announced his resignation. “12 years is a long time in a job like this one,” he observed (SvD 2 February).1

The method of leader selection: The importance of the preparation phase

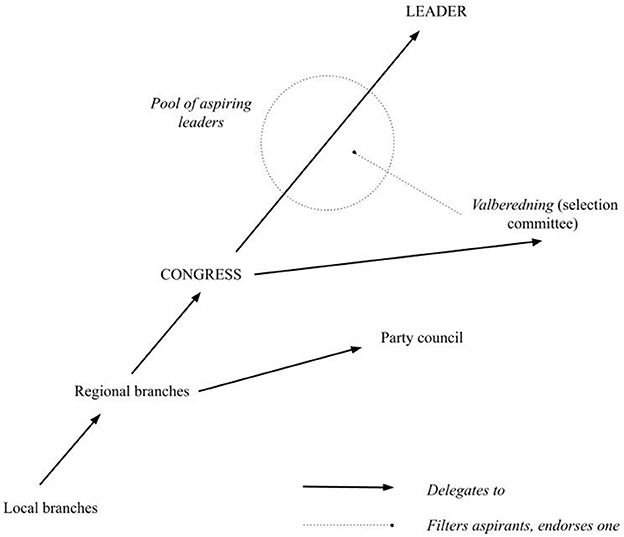

The first phase of the framework, gatekeeping, can be disregarded in the Liberals' case. There were no formal eligibility requirements for anyone who aspired to lead the party. The third and final phase, decision, was also fairly straightforward. The party congress—or, more precisely, its delegates, chosen by the party's 21 regional branches—was to decide. The congress, in other words, was the Liberals' selectorate. This meant that the heavy lifting was to take place in the middle phase, preparation. As in other Swedish parties (and, indeed, in most Swedish organisations that claim to run themselves democratically), the Liberals used a selection committee, or valberedning.

The valberedning represents a form of “precursory delegation,” in which the task of managing the selection process is delegated to a “steering agent” (Aylott and Bolin, 2021a). This agent usually comprises a handful of people who are generally seen as honest brokers, without political ambitions of their own. In a party, the valberedning is formally appointed by the congress. However, appointments are often first decided informally. They will usually be the subject of negotiations in advance between representatives of certain intra-party power centres. These negotiations are about achieving a balance in positions of influence—sometimes a balance between ideological factions or interest groups, but frequently also a balance between social characteristics (sex, age, residence and so on). The valberedning often formulates the proposed balance, including that in its own membership. In fact, the composition and conduct of this valberedning are telling indicators of how the intra-party balance of power is constructed (Aylott and Bolin, 2021a).

When precursory delegation occurs in a party's selection of its leader, balance is less important than consensus—or, at least, as much consensus as can be achieved. The steering agent's job is thus to channel internal competition for the appointment. Although, by 2019, a degree of open competition between a few approved candidates had been permitted in some Swedish parties' processes, the valberedning nevertheless endorsed one preferred candidate before the decision reached the selectorate. There had been occasional exceptions (especially in the Greens), but this endorsement was usually decisive. It persuaded other candidates to drop out, or it persuaded the selectorate to eschew them. The party could then be seen to unite behind its new leader (see Figure 2).

True, the Liberals are, by Swedish standards, relatively open to organisational innovation.2 As regards leader selection, some Liberals long been keen on more inclusivity in leader selection (Schmidt, 2017). The 2015 party congress had passed the idea to the national executive to explore (Nu 15 June 2017), but nothing further had happened. The challenger to Björklund in 2017 had called for a membership ballot (Nu 8 June 2017), but this had been rejected by the valberedning (SvD 16 June 2017; Nu 22 June 2017). Still, in the challenger's home region of Östergötland, a ballot had indeed been held—a first in Sweden, according to a former parliamentarian who had promoted the idea there (DN 18 June; Sundin and Karlsson, 2015; Sundin, 2017).3 Somewhat surprisingly, Björklund—who was seen, ideologically, as to the right of his challenger—had won that vote (SvD 23 August 2017). He, the ballot's advocates in Östergötland and the challenger herself had all expected it to favour her (interview 5).4

Opening stages

When Björklund resigned, the seven current members of the Liberal valberedning had been chosen by the 2017 party congress. The party's regional branches are informally divided into six clusters; and, within each cluster, the branches take turns to nominate committee members. The seventh member is nominated by the youth wing. These nominees are then approved by the congress (interview 3). In practise, then, the Liberal valberedning was dominated by local and regional levels of the party organisation, as in other Swedish parties (Bolin and Aylott, 2021b). In fact, of the nominees approved in 2017, only the chair of the valberedning had parliamentary experience.

At first, there was little to indicate procedural innovation. The Liberals' valberedning intended to gauge the leadership preferences held in key parts of the party. These included the regional branches. The parliamentary group and collateral organisations were also sure to be consulted.

The role of the valberedning is only lightly regulated in the party's statutes (Liberalerna, 2017), so it had some freedom to construct the process. It soon published a schedule for choosing Björklund's successor. There were to be four stages: exploratory (sondering), hustings, nomination, and the congress vote (Liberalernas Valberedning, 2019). An extra congress was set for late June (SvD 20 March). That left nearly 5 months for the Liberals to conduct their selection. However, the timetable was complicated by an election to the European Parliament in late May. Some felt that making a selection before then would be to rush it.

Several regional branches had already expressed interest in having members vote directly in some form (Nu 14 February); three branches intended to hold ballots (Nu 28 February). However, although the valberedning's plan had been discussed with the branches, and although there was a consensus that the process should be transparent and involve several candidates, it was to conform to customary practise. There was no demand for a membership ballot, the valberedning declared (Liberalernas Valberedning, 2019). Its chair later suggested (Schmidt, 2019) that it had, in fact, asked the regional branches's executive boards about a ballot, but interest then had been “lukewarm” (svalt).

In the exploratory stage, from mid-March to mid-April, the regional branches' executive boards (chosen by regional congresses), other party units and individual members were all invited by the valberedning to suggest suitable candidates for the leader's job. The media was soon speculating about who might run, and the likely battle between the party's social-liberal left and its “demanding-liberal” (“kravliberal”) right. Björklund's challenger from 2017 declined to try again. One Liberal favourite, Sweden's outgoing European commissioner, also demurred. Meanwhile, as it prepared for the European election, the party's only MEP, firmly on its left, was messily removed from its list by the valberedning due to conflicts of interest. This upset some in the party (interview 1).

The first to join the race, in early April, was Sabuni (2019). A former parliamentarian and government minister, she was on the party's right, which aroused apprehension in other quarters. She had previously mooted talks with the Sweden Democrats (Sabuni, 2017), an idea that, even by 2019, was still semi-taboo on the mainstream Swedish right (although that was starting to change). Even before she had confirmed her candidacy, Sabuni reportedly criticised the mainstream parties' “bullying” of the Sweden Democrats. At the same meeting, two former leaders, both left-leaning, warned against her candidacy (Exp. 27 March). After she declared, Sabuni pledged to uphold the January agreement over the parliamentary term, but looked to a revival of the Alliance thereafter (SvD 12 April).

It was known that Sabuni was close to the Liberals' last-but-one leader (Exp. 27 March). He had become a senior advisor in a lobbying firm. A former Liberal secretary-general ran another lobbying firm.5 Later, once the contest had been all but decided, accusations surfaced that these two had advised Sabuni and channelled external resources into her campaign.6 However, in our research, we found little to indicate that such advice and resources had made much difference in promoting Sabuni's candidacy—or, for that matter, the institutional instability that, as we will see, favoured her.

By late May, Sabuni, despite having had the field to herself for 5 weeks, was still not seen in the media as a likely winner. A strong challenge from the Liberal left was anticipated—perhaps from Erik Ullenhag, a former party secretary-general, parliamentarian and government minister (SR 20 May). After all, the January agreement had only recently received a two-thirds majority in the party council, so—as commentators pointed out—it seemed unlikely that the party congress, delegates to which were also chosen by the regional branches, would now rally behind a candidate who had been against the agreement. “As I understand it,” remarked the political editor of a centre-right newspaper, “the internal opposition to Sabuni is just too strong” (Exp. 20 May).

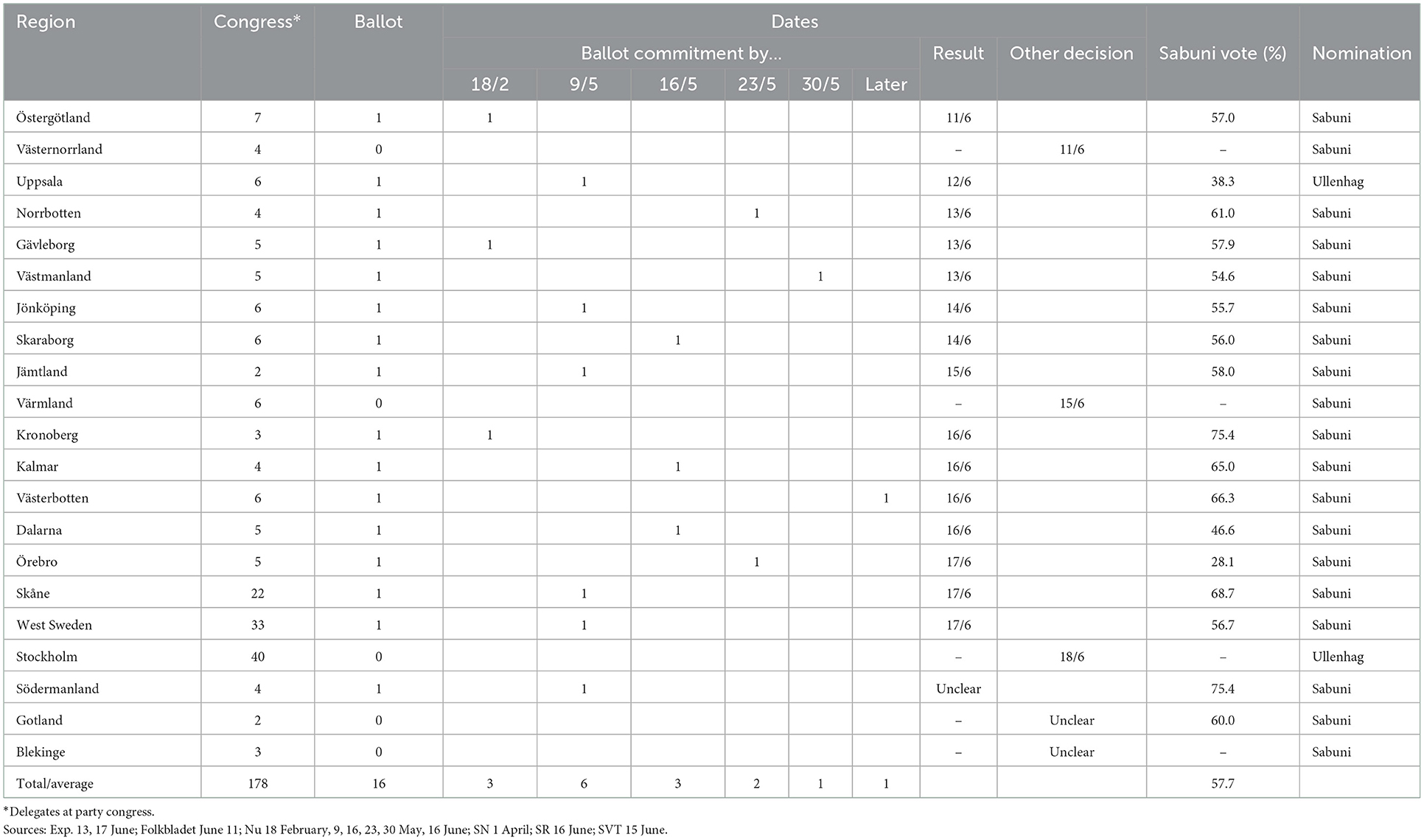

Yet a crucial condition had changed. The idea of regional ballots of the party membership had caught on, spreading in a sort of plebiscitarian revolution. Throughout May, another dozen branches had decided to hold them. The votes were to take varying forms; some were to be at least partly digital. All were to be implemented once the hustings stage had ended and the nomination stage had begun, on 10 June. The reasons for holding them were, according to quotes published in a small survey by a Liberal magazine, procedural rather than political. “We want to give members a chance to be a part of the process,” explained one region's vice-chair. “We think it vitalises and strengthens the internal democracy in the party,” said the chair of another (Nu 22 May).

Yet there was no consensus on what the result of each regional ballot would mean. Even if it was advisory, would the ballot shape the regional executive's decision on who to nominate to the valberedning as its preferred candidate for leader? And would it bind the branch's delegates later, at the national congress? In late spring (Nu 9 May), when only Sabuni had yet declared, the chair of the Östergötland branch had stated that the candidate who got the most votes in the region's ballot would get the support of all the region's delegates to the party congress—although it was unclear how this would be ensured, given that the congress vote was to be a secret ballot. Another region's chair declared that its congress delegates would be “expected” to adhere to the result of its ballot, although they could not be compelled to do so. “You don't become popular in our county if you ignore members' decisions,” he remarked. In the same magazine, however, there were also warnings about the consequences for intra-party representative democracy (Ängeby, 2019).

Contenders and campaign

After the European election (in which the Liberals narrowly retained their only mandate, despite scraping just 4 per cent of the vote), two other candidates entered the contest, six and a half weeks after Sabuni had done so. Ullenhag (2019a) was one. The other was Pehrson (2019), the Liberals' economics spokesman and another former secretary-general. He was seen as an outside bet, although he did have one advantage over his rivals: he was a member of parliament; they were not.7

In fact, and oddly enough, both the main contenders had been absent from national politics for some time. Ullenhag had been Sweden's ambassador to Jordan since 2016. Sabuni had left for the private sector as early as 2013. There were also some obvious differences between the three candidates. Sabuni is a woman who emigrated from Burundi at the age of 12. Pehrson and Ullenhag are men of Swedish ethnicity. Still, these factors were rarely mentioned in media commentary and appeared to play little part in the contest. After all, Sabuni was a well-known figure, and Liberals pride themselves on their progressive social views. The political differences between the candidates were more salient.

Pehrson—who, like Sabuni, had been against the January agreement—emphasised law and order in his pitch. Ullenhag, by contrast, supported the January agreement; was staunchly against detente with the radical right; and declined to commit to any revived Alliance (SvD 29 May). He said he wanted to make Sweden snällare (DN 3 June), meaning something between kinder and nicer. For many, he was the candidate of the Liberal establishment—and the likeliest winner. He was surely a better fit with the party culture depicted in earlier research (Barrling Hermansson, 2010).

In the exploratory phase, the valberedning received about 50 suggestions for who the new leader should be. It shortlisted six, who, at the end of May, became three, after interviews with them (interview 4). Unsurprisingly, the three were Pehrson, Sabuni and Ullenhag.

In the second stage of its schedule, which began on 31 May, the valberedning arranged four open hustings (SR 3 June). According to the chair of the committee, these events were attended by about 1,000 people and seen by more than 100,000 live on Facebook (interview 4). In addition, several regional and local branches arranged meetings at which party members listened and put questions to the candidates (Schmidt et al., 2019). By restrained Swedish standards, the campaign became heated. Sabuni sounded tough, even confrontational, on immigration (Exp. 6 June), then rowed back (DN, SvD 9 June). Ullenhag was evasive about talking to the Sweden Democrats (SVT 2 June) and sought to nuance his reputation as permissive on immigration (SvD 15 June).

In parallel to the campaign, however, the party's institutional revolution was underway. The regional membership ballots turned the contest decisively in Sabuni's favour, and took it away from the control of the valberedning.

The erosion of the selection committee's authority

In Östergötland, the candidates appeared at a “primary vote” (primärval) meeting on 11 June, after which members in attendance chose between them (Folkbladet 4 June).8 By Friday 14 June, six more ballots had taken place. According to a party source, the results were “shocking”: Sabuni won all but one (DN, Exp. 13 June). Still, the head of a liberal news agency suggested that while the smaller regions appeared to be leaning towards Sabuni, the biggest ones were still expected to be keener on Ullenhag.9 Even at this point, a liberal columnist predicted victory for him (SvD 14 June). As it turned out, however, 13 of the 16 regional ballots went in Sabuni's favour—including, on Sunday 16 June, those in the second- and third-biggest regions. Her average share of the votes was about 58 per cent, to Ullenhag's 38 per cent (Nu 19 June).10 In light of these results, two Liberal parliamentarians urged Ullenhag to withdraw (DI 17 June).

Ten days before the congress, the penultimate stage of the selection process commenced. Each regional branch now nominated its preferred candidate to the valberedning. Just two went for Ullenhag: his home region, Uppsala; and Stockholm, one of only three regions that did not hold a membership ballot (SR 18 June).11 The Liberals' youth, student and women's wings also backed him, though.

The contest was not yet decided. There remained the question of how each regional branch's delegates to the national congress ought to act in the final stage of the process, when the congress decided the outcome.

Should each delegate support the candidate who had been favoured in her own region's ballot? Yes, argued the pioneer of membership ballots, based in Östergötland (Folkbladet 11 June; Sundin, 2019). “If you are not interested in following what the members think, you should not go out and ask them, because then you are misleading the members and creating mistrust between them and regional leaders,” argued one regional chair (SR 17 June). Unsurprisingly, Sabuni concurred (2019b). Or should the delegates, as 11 of them insisted (Acketoft, 2019), be guided only by their consciences?12 The chair of the Liberal parliamentary group reportedly urged pro-Ullenhag delegates to hold firm, whatever their regions' ballots or boards had decided (Exp. 16 June).

This uncertainty had never arisen in any previous leader selection. There had never been membership ballots before, so the regional executive boards could not be influenced by them in their nomination decisions.13 Meanwhile, the party's selectorate—congress delegates—only rarely did anything other than rubber stamp the lone candidate endorsed by the valberedning. The selectorate had thus previously enjoyed only very little discretion.

As it turned out, these questions of procedural legitimacy were never resolved. Instead, they were rendered academic, as resistance to Sabuni's candidacy ultimately crumbled.

Pehrson, who had attracted just 6 per cent of the votes in the ballots, withdrew from the contest a week before the congress. On 24 June, 3 days before the congress, the chairs of the Stockholm and West Sweden executive boards, which had nominated different candidates, declared in a joint op-ed that their delegates, who comprised 41% of the total, would vote individually, not as blocs (Johansson and Gustafsson, 2019). Almost simultaneously, however, the valberedning published its own article, in which it endorsed Sabuni as the new leader (Schmidt et al., 2019). The committee implied that it could not ignore the overwhelming verdict of the ballots. Nevertheless, the valberedning was split (SVT 24 June). Two of its seven members remained in favour of Ullenhag (Brohede Tellström, 2019).14

The decision of the valberedning, despite its split, prompted Ullenhag to withdraw. He explained that he wanted to avoid further division within the party (Ullenhag, 2019b). Later, he conceded that he did not want to lead a divided party (interview 6). The valberedning could thus belatedly unite behind its endorsement of Sabuni (interview 4). So too did the congress, after Pehrson and Ullenhag had urged delegates to back her. She was duly elected leader by acclamation. Despite the hard-fought contest and the institutional upheaval that it featured, the process thus ended in the customary coronation.

Interpreting the case

In this section, we discuss the first two links in the chain of events that we introduced at the outset of this article. The links are centred on two outcomes: first, Sabuni's victory; and, prior to that, the spread of member ballots through the Liberals' regional branches. (We briefly discuss additional links, with outcomes that occurred after Sabuni's victory, in the final, concluding section.)

The chain of causes and outcomes

How did Sabuni win? While various factors contributed to the outcome, what we have called the plebiscitarian revolution in the party was a critical event. It was undoubtedly contingent. No Swedish party had ever previously held a membership ballot in selecting its leader. In early 2019, the Liberals' valberedning had explicitly ruled one out.

The revolution was at least moderately necessary for Sabuni's victory. Before the ballots at regional level broke out, and even as they were underway, Ullenhag was still being tipped by knowledgeable observers. His social-liberal profile and disdain for the Sweden Democrats appeared likely to appeal to mid-level party elites—at least if the vote in the party council on the January agreement just a few months earlier is taken to indicate their preferences. Even after the membership ballots, senior party figures—including Ullenhag himself (interview 6)—thought it conceivable that he might yet have won at the congress, when the selectorate made its choice. That seems unlikely. But it shows that Ullenhag was a strong candidate. Without the revolution, it is quite possible that Sabuni would not have won.

The ballots were also sufficient to induce the outcome. To put it another way: in a “possible world” (Mahoney, 2021, pp. 54–63) in which all other conditions remained the same as in the actual world, and thus in which grass-roots discontent with the January agreement still simmered, the absence of the ballots would surely have been necessary for anyone other than Sabuni to win. The revolution was thus both contingent and causally important.

Why did the Liberals' selection method break down? In many ways, then, the crucial questions about the whole case concern this critical event. If we shift the focus to regard it as the outcome, we can construct a plausible account of its causes.

A series of prior events had made the plebiscitarian revolution more likely. One such was the decision by two Alliance parties, after the 2018 election, to embrace the idea of building a governing majority with the Sweden Democrats' help. This decision might amount to the sort of external “shock” that Harmel and Janda (1994, pp. 267–278) suggest can induce party change. Yet it was not a real surprise; the rupture in the Alliance had been on the cards for some time. Other events were more contingent. While the Liberal right was dismayed by the January agreement, the left was unhappy at the controversial sacking of its incumbent MEP prior to the European election. Across the party, there was worry at its precipitous fall in opinion polls since the 2018 election.

Collectively, we argue that these events created what we call party stress. This condition was insufficient to induce the plebiscitarian revolution. But it may have been necessary for it.15 Without this stress, which made party members more open to change and to conflict with Liberal elites, the spread of membership ballots might well not have happened.

The Liberal lobby for greater inclusivity in leader selection must also figure prominently in our explanation. It had achieved its organisational bridgehead with its ballot in Östergötland in the leadership challenge of 2017. This was insufficient to induce the revolution. (Ideas do sometimes need time to permeate an organisation. As we have argued, their advance is not inevitable). The bridgehead may have been necessary, however. Many Liberals must have become aware of the arguments for direct membership involvement in leader selection, especially after the 2017 example of a regional ballot that had not been sanctioned by the party's leadership or its valberedning.

And what of Sabuni's candidacy itself? It was obviously necessary for her ultimate victory. But, in our view, it was unnecessary for the revolution that was, in turn, critical for her victory. After all, plans for ballots in some regional branches were being laid weeks before Sabuni confirmed her candidacy. The evidence for the causal sufficiency of her candidacy, meanwhile, would be stronger if we had found, as had been alleged, that Sabuni's campaign team had actively promoted ballots in the regional branches. In fact, those who had most keenly and consistently promoted ballots before and during 2019 were not associated with Sabuni or the right of the party, as had been shown during the challenge to Björklund in 2017. They saw more inclusive selection simply as a way to mobilise and enthuse members (interviews 1, 5).

It does seem possible that Sabuni's grass-roots sympathisers gradually realised that ballots would help her candidacy, and that this boosted the momentum of institutional change. That might help to explain why party regions that were initially unenthusiastic about a national ballot, according to the valberedning, converted to holding ballots at regional level. Yet we found no direct evidence that Sabuni's candidacy really had that effect. Our inference, then, is that the other two factors discussed above—party stress and the 2017 bridgehead—were not only necessary but also jointly sufficient to cause the membership ballots that were, in turn, critical for Sabuni's success.

A causal mechanism

Our contribution to theory development is in analysing how the relevant conditions facilitated the outcome of the case. We identify a mechanism that, we argue, was present in the causal chain. Its presence was facilitatory: it unlocked the causal forces of the conditions outlined above (see Figure 3). Its operation was necessary (but not sufficient) to induce the institutional change that made Sabuni's victory much more likely. We call it a shift in the perception of procedural legitimacy.

In comparative politics, procedural fairness or legitimacy has usually been associated with citizens vis-à-vis the state (Easton, 1975; Tyler, 1994; Erlingsson et al., 2014). Here, however, we associate it with the internal decision-making of a political party. It involves cognitive evaluation on the part of individuals within the party, and decisions about action in light of that evaluation. In other words, the individual takes a position on whether organisational matters are being managed in an appropriate way, or whether there are preferable alternatives. This mechanism is especially important in party leader selection because power is so often exerted informally, beyond what statutes stipulate. Intra-party actors who are content with the extant balance of intra-party power will seek to preserve a prevailing perception of procedural legitimacy. Those who are discontented will seek to activate change—which can, in turn, affect the outcome of a leader selection.

In a party like the Liberals, internal democracy is an important self-image. Before 2019, few Liberals had seen any conflict between that self-image and the customary Swedish form of representative intra-party democracy that is “managed” by a valberedning (Aylott and Bolin, 2017). In 2019, that changed. Under the conditions discussed above, regional elites—the executive boards—were forced to defend explicitly the previous institutional arrangement, and most could not do so. It may be rhetorically easier to make the case for direct democracy than for the indirect sort (interview 6). One by one, most branches changed their positions on ballots. As each new one did so, change in the remaining hold-outs became more likely. At some point, a “tipping phenomenon” occurred (Hardin, 1995, p. 146), and only a few ultimately resisted the trend. One of the leadership candidates referred to a “snowball effect” (interview 2). The perception of procedural legitimacy shifted.

It suddenly meant a very different role for the valberedning. It usually presents the selectorate with a fait accompli. In 2019, it was itself presented with a fait accompli by the regional branches. The valberedning was marginalised. It could not have ignored the results of the regional ballots without sparking chaos.

The mechanism can work retrospectively, too. It is normal for leadership candidates in other European parties to submit themselves to the selectorate even if they have little chance of winning. They can stake their claims as likely contenders in a future leadership contest. So why did Pehrson and Ullenhag choose to withdraw before the party congress voted? Our interviews with Liberals suggest that a candidate who is unlikely to win, but who still takes her candidacy all the way to the selectorate, would face social and political sanction from others in the party. They would see such behaviour as selfish and inappropriate. Far from enhancing a future claim to the leadership, a stubborn refusal to withdraw would undermine such a claim. To preserve her reputation for loyalty and collegiality, then, the candidate drops out before the selectorate decides. She displays deference to the institution.

Conclusions

In this article, we have argued that the general trend towards greater inclusivity in decision-making is not some natural force. We should rather seek to pin down the specific causes of change in particular cases, and then assess possible common causes. The Swedish Liberals' selection process in 2019 involved a significant deviation from the party's norm and the country's norm—one that had, moreover, major consequences for Swedish politics. We have sought to describe and explain how it could occur.

We have addressed two outcomes. The first was Sabuni's unexpected victory in the Swedish Liberals' leader selection of 2019, before which, we suggest, an intra-party plebiscitarian revolution was a critical causal event. When trying to explain that revolution, our second outcome, we suggested two necessary and jointly sufficient causes. The first was what we called party stress. It was not just electoral defeat (which was not that severe), nor the break-up of a longstanding alliance with other parties (which had been coming for some time), nor additional internal rows: it was the combined effect of these events. The second was the bridgehead established by the advocates of inclusive decision-making during an abortive leadership challenge 2 years before. It planted a seed in ground that later became unexpectedly fertile.

The effect of the causes was enabled by a mechanism, a shift in the perception of procedural legitimacy, that facilitated both the revolution and the confirmation of Sabuni's triumph. In this case, we argue that the mechanism was not the one more commonly identified in previous research—that is, of change initiated from the top of the party, in order to try to make membership more attractive for existing and prospective members by offering them a more direct role in decision-making. Rather, the mechanism in our case involved a bottom-up intra-party revolt—or, more accurately, a revolt by regional activists against what they perceived as Stockholm-based elites' unrepresentative preferences, particularly that for sustaining a left-of-centre government rather than considering an accommodation with the radical-right Sweden Democrats. As the process unfolded, Liberal activists became persuaded that their party's established selection method, which few had previously questioned, was now illegitimate; and they acted accordingly. Their idea of ”good democratic practice“ (Gauja, 2017, p. 9) was thus suddenly transformed.

We suspect that this mechanism will be detectable in other parties, although we do not know how frequently. Similar process-tracing research into other cases of party reform, in which members are included more directly in leader selection, is obviously an intriguing possibility for future research.

Postscript

On the right side of Figure 3, a grey arrow links to a further outcome, for which Sabuni's victory was a cause. This outcome was party-system change. In mid-2021, Sabuni overcame considerable internal opposition and withdrew the Liberals from the January agreement. Instead, she committed her divided party to supporting a right-of-centre government that would seek an understanding with the Sweden Democrats.

This strategy may have contributed to the Liberals' recovering enough votes to retain their parliamentary representation in the election of 2022. Yet while Sabuni instigated the strategy, she did not see it through. She resigned 5 months before the election, after less than three years as leader. Pehrson, who had become leader of the Liberal parliamentary group under Sabuni and, a little later, also the party's first vice-chair, was appointed as her replacement by a unanimous national executive (SvD 8 Apr. 2022), subject to confirmation at a later party congress. Only then did the Liberals' support pick up. It contributed to a narrow win for the right-leaning bloc in the election and the formation of a three-party coalition government that included the Liberals—and was supported by the Sweden Democrats. Internal reaction to the agreement suggested that Liberals remained bitterly divided about their party's direction (Aylott and Bolin, 2023). Nevertheless, the party congress unanimously confirmed Pehrson's confirmation as Liberal leader in November 2022.

The Liberals' own first response to their institutional revolution was to seek to formalise the new selection procedure. The party council recommended to the 2021 party congress that the statutes should provide for an advisory membership ballot before the selection of any future leader (Nu 22 October; Liberalerna, 2020; Malm, 2020). Yet congress delegates voted by a large margin, 122 to 52, to reject the recommendation (Liberalerna, 2021). It will be fascinating to see if the perception of procedural legitimacy has durably shifted in the Liberals, which would militate towards more internal rows about how the party selects its leaders; or whether, with political circumstances changed, the perception of procedural legitimacy has, in fact, shifted back towards the traditional Swedish line, based on precursory delegation and the channelling of competition by a steering agent. It will be equally fascinating to see whether the Liberals' fateful experiment with membership ballots influences other Swedish parties, which have been so resistant to change.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

Research for this article was funded by a project grant issued by the Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies (ÖSS-dnr 19/18).

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the conference of the Nordic Political Science Association (August 10–13, 2021) and the political science research seminar at Södertörn University (September 8, 2021). The authors are grateful for the useful comments received there. We are additionally grateful for the constructive suggestions made by the referees for this journal.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2023.1070269/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^In fact, Björklund became the Liberals' second-longest-serving leader. When his term ended, the party's 11 leaders had each spent, on average, nearly 8 years in the job. When the four shortest-serving leaders are excluded, the average rises to 11 years (see Bolin, 2019).

2. ^Back in 2002, the party's secretary-general had talked about building a “network party,” which would embrace liberals who were not necessarily members (DN 28 Oct. 2002). Indeed, in the parliamentary election the previous month, a non-member had successfully stood on a Liberal list. But this initiative petered out.

3. ^In fact, the same region had held an even earlier advisory ballot of its members in 2014, when the party was choosing its list for the European parliamentary election (interview 5).

4. ^Another region had planned a ballot, but the challenge to Björklund fizzled out before it could be held (SR 23 August 2017).

5. ^This is was the same secretary-general who had referred to the “network party” 17 years previously (see footnote 2).

6. ^The claim was made in a newspaper's unsigned editorial (Eskilstuna-Kuriren, 2019). Around the same time, it emerged that, in April 2019, a Liberal parliamentarian, together with (in his words) unnamed “individuals who did not want to be phoned up by journalists', had paid for a survey of the party's sympathisers in the electorate. The survey showed (also in his words) ”that many were disappointed with the [January] agreement and that...Sabuni had much stronger support than anyone had thought“ (DO 26 June). The survey was in line with later, public surveys (Exp. 10 June); but, according to the editorial, it had boosted Sabuni's campaign at a key moment. Even later, an anonymous letter was sent to the Liberals' national executive board (Reuterskiöld, 2020). According to this letter, the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise, the main employers' organisation, had been keen to see a change of government, which required the Liberals back in the centre-right fold. The confederation had allegedly sought to promote its objective via the lobbying firm run by the Liberals' former secretary-general.

7. ^In an opinion poll back in February, Sabuni had been second-favourite (behind the European commissioner) among Liberal sympathisers, with 17%. Ullenhag had been backed by 7% and Pehrson by 2% (Inizio, 2019).

8. ^We avoid the generic term ”primary“ in the current context. Our view is that it implies a preliminary step in a public electoral process (cf. Kenig et al., 2015, p. 150). A European party leader, however, is first and foremost the head of the party, a private organisation. Her role in any subsequent public election is quite separate.

9. ^Later, this sequencing of ballots, and the speedy appearance of their results in the media, was said by a journalist's sources in the party to be part of the Sabuni camp's strategy to build momentum (Reuterskiöld, 2020). However, it is difficult to see any relationships between a region's size (measured by its congress delegation), the timing of its decision to hold a membership ballot, the timing of the ballot itself and the proportion of the vote that went to Sabuni (see Table 1).

10. ^Turnout was about 40%.

11. ^Stockholm and one other region did, however, record the results of ballots held by their local branches—which, in practice, served as an alternative to a regional ballot (Nu 20 June). Most of those in Stockholm favoured Sabuni, which caused further shock in the party (Exp. 13 June). In addition, two regions nominated Sabuni even though Ullenhag had narrowly won their ballots (Exp. 17 June).

12. ^To employ Burke's well-known terminology, this view implied that members of the party congress should be seen more as trustees than delegates.

13. ^For sure, advisory membership ballots (provval) were commonplace in the party when drawing up lists of the party's candidates in parliamentary, regional and local elections (Aylott et al., 2013, p. 173). However, it was expected that a regional valberedning would take account of the results, and no more than that, when it proposed a list. Achieving a balanced ticket, with due representation of sexes, age groups, regions and the like, was seen as a normal and legitimate reason for affording a valberedning wide discretion in formulating its proposed list. That sort of justification would be much more difficult to maintain in a leader selection, when the endorsement of a single individual was at stake.

14. ^This disunity in the valberedning was unusual, but not unique. Something similar had happened in the Liberals in 1995, when the valberedning endorsed a candidate who then lost at the congress.

15. ^Individually, then, the ingredients of party stress are ”SUIN causes“: sufficient but unnecessary to constitute a cause that itself is insufficient but necessary for an outcome (Mahoney et al., 2009, pp. 126–28).

References

Achury, S., Scarrow, S. E., Kosiara-Pedersen, K., and van Haute, E. (2020). The consequences of membership incentives: do greater political benefits attract different kinds of members? Party Polit. 26, 56–68. doi: 10.1177/1354068818754603

Acketoft, T. (2019). Vi väljer att redan nu avslöja vår valhemlighet. Expressen, June 22. Available online at: www.expressen.se/debatt/vi-valjer-att-redan-nu-avsloja-var-valhemlighet (accessed April 29, 2021).

Aylott, N., Blomgren, M., and Bergman, T. (2013). Political Parties in Multi-Level Polities: The Nordic Countries Compared. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9781137315540

Aylott, N., and Bolin, N. (2017). Managed intra-party democracy: precursory delegation., and party leader selection. Party Polit. 23, 55–65. doi: 10.1177/1354068816655569

Aylott, N., and Bolin, N. (2019). A party system in flux: the Swedish parliamentary election of September 2018. West Eur. Polit. 42, 1504–1515. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2019.1583885

Aylott, N., and Bolin, N. (2021a). ”Conflicts and coronations: analysing leader selection in European political parties“, in Managing Leader Selection in European Political Parties, eds N. Aylott, and N. Bolin (London: Palgrave), 1–28. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-55000-4_1

Aylott, N., and Bolin, N. (2021b). ”The rule of the valberedning? Party leader selection in Sweden“, in Managing Leader Selection in European Political Parties, eds N. Aylott, and N. Bolin (London: Palgrave), 175–195. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-55000-4_9

Aylott, N., and Bolin, N. (2023). A new right: the Swedish parliamentary election of September 2022. West Eur. Polit. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2022.2156199

Backlund, A. (2020). Isolating the Radical Right: Coalition Formation and Policy Adaptation in Sweden [Doctoral thesis]. Huddinge: Södertörn University.

Bakker, R., Hooghe, L., Jolly, S., Marks, G., Polk, J., Rovny, J., et al. (2020). Chapel Hill expert survey trend file, 1999–2019. Elect. Stud. 75, 102420. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102420

Barnea, S., and Rahat, G. (2007). Reforming candidate selection methods: a three-level approach. Party Polit. 13, 375–394. doi: 10.1177/1354068807075942

Barrling Hermansson, K. (2010). Bland blåklint och tomtepålar. Om det kulturella tillståndet i Folkpartiet Liberalerna. Statsvetenskaplig Tidskrift 112, 203–214.

Biezen, I., Mair, P., and Poguntke, T. (2012). Going, going, gone? The decline of party membership in contemporary Europe. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 51, 24–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.01995.x

Blatter, J., and Haverland, M. (2012). Designing Case Studies: Explanatory Approaches in Small-N Research. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9781137016669

Bolin, N. (2019). “The Centre Party and the Liberals: the Swedish members of the liberal party family?” in Liberal Parties in Europe, eds E. van Haute, and C. Close (London: Routledge), 60–76. doi: 10.4324/9781351245500-3

Bolin, N., and Aylott, N. (2021a). “Patterns in leader selection: where does power lie?”, in Managing Leader Selection in European Political Parties, eds N. Aylott, and N. Bolin (London: Palgrave), 217–243. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-55000-4_11

Bolin, N., and Aylott, N. (2021b). Analysing intra-party power: Swedish selection committees over five decades. Politics 10, 2633957211051638. doi: 10.1177/02633957211051638

Brohede Tellström, M. (2019). Ledamot: Därför reserverade jag mig mot nomineringen. SVT, June 25. Available online at: www.svt.se/opinion/darfor-reserverar-jag-mig-mot-nyamko-sabuni (accessed March 26, 2021).

Cross, W., and Pilet, J-B., (eds.). (2015). The Politics of Party Leadership: A Cross-National Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198748984.001.0001

Easton, D. (1975). A re-assessment of the concept of political support. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 5, 435–457. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400008309

Erlingsson, G. Ó., Linde, J., and Öhrvall, R. (2014). Not so fair after all? Perceptions of procedural fairness, and satisfaction with democracy in the Nordic welfare states. Int. J. Publ. Admin. 37, 106–119. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2013.836667

Eskilstuna-Kuriren (2019). Vem har påverkat Liberalernas vägval? Available online at: https://ekuriren.se/bli-prenumerant/artikel/lqdv3wer/ek-2m2kr_s_22 (accessed March 26, 2021).

García-Montoya, L., and Mahoney, J. (2020). Critical event analysis in case study research. Sociol. Methods Res. 8, 49124120926201. doi: 10.1177/0049124120926201

Gauja, A. (2017). Party Reform: The Causes, Challenges, and Consequences of Organizational Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198717164.001.0001

Gerring, J. (2017). Case Study Research: Principles and Practices, 2nd Edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781316848593

Hardin, R. (1995). One For All: The Logic of Group Conflict. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Harmel, R. (2002). “Party organisational change: competing explanations?,” in Political Parties in the New Europe. Political and Analytical Challenges, eds K. R. Luther, and F. Müller-Rommel (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 119–142.

Harmel, R., and Janda, K. (1994). An integrated theory of party goals, and party change. J. Theor. Polit. 6, 259–287. doi: 10.1177/0951692894006003001

Hedström, P., and Ylikoski, P. (2010). Causal mechanisms in the social sciences. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 36, 49–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102632

Ignazi, P. (2020). The four knights of intra-party democracy: a rescue for party delegitimation. Party Polit. 26, 9–20. doi: 10.1177/1354068818754599

Inizio (2019). Liberalerna: Vem efterträder Jan Björklund? Available online at: www.inizio.se/opinion/liberalerna-vem-eftertrader-jan-bjorklund (accessed May 14, 2021).

Johansson, A.-L., and Gustafsson, P. (2019). Ombuden ska rösta efter egen bedömning. Aftonbladet, June 24. Available online at: www.aftonbladet.se/debatt/a/zGVMBv/ombuden-ska-rosta-efter-egen-bedomning (accessed March 26, 2021).

Katz, R. (2013). “Should we believe that improved intra-party democracy would arrest party decline?” in The Challenges of Intra-Party Democracy, eds W.P. Cross, and R.S. Katz (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 49–64. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199661879.003.0004

Katz, R. S., and Mair, P. (2018). Democracy and the Cartelization of Political Parties. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kenig, O. (2009). Classifying party leaders' selection methods in parliamentary democracies. J. Elect. Publ. Opin. Part. 19, 433–447. doi: 10.1080/17457280903275261

Kenig, O., Cross, W., Prusers, S., and Rahat, G. (2015). Party primaries: towards a definition, and typology. Representation 51, 147–160. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2015.1061044

Kosiara-Pedersen, K., Scarrow, S. E., and van Haute, E. (2017). ”Rules of engagement? Party membership costs, new forms of party affiliation, and partisan participation,“ in Organizing Political Parties: Representation, Participation, and Power, eds S. E. Scarrow, P. D. Webb, and T. Poguntke (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 234–258. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198758631.003.0010

LeDuc, L. (2001). Democratizing party leadership selection. Party Polit. 7. 323–341. doi: 10.1177/1354068801007003004

Liberalerna (2020). Stärk medlemmarnas röst vid val av partiledare. Rapport till partirådet 2020. Available online at: www.liberalerna.se/wpcontent/uploads/20-09-partiledarval.pdf (accessed May 14, 2021).

Liberalerna (2021). Protokoll fört vid Liberalernas landsmöte i Linköping 19–21 November 2021. Available online at: https://www.liberalerna.se/wp-content/uploads/landsmotesprotokoll-2021.pdf (accessed November 22, 2021).

Liberalernas Valberedning. (2019). Utkast till process för val av ny partiordförande. Available online at: www.liberalerna.se/wp-content/uploads/20190216-valberedning-utkast-tidplan-web.pdf (accessed May 14, 2021).

Mahoney, J., Kimball, E., and Koivu, K. L. (2009). The logic of historical explanation in the social sciences. Compar. Polit. Stud. 42, 114–146. doi: 10.1177/0010414008325433

Mair, P. (1997). Party System Change: Approaches, and Interpretations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mair, P. (2008). The challenge to party government. West Eur. Polit. 31, 211–234. doi: 10.1080/01402380701835033

MäMä (Mätningarnas mätning). (undated). Opinion Poll Data. Available online at: www.datastory.org/sv/services/poll-of-polls-sweden (accessed December 13 2021).

Panebianco,. A. (1988). Political Parties: Organization and Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pehrson, J. (2019). Jag kandiderar till partiledare för Liberalerna. Expressen. Available online at: www.expressen.se/debatt/johan-pehrson-jag-kandiderartill-partiledare-for-liberalerna (accessed April 29, 2021).

Pilet, J.-B., and Cross, W., (eds). (2014). The Selection of Political Party Leaders in Contemporary Parliamentary Democracies: A Comparative Study. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315856025

Pilet, J.-B., and Wauters, B. (2014). “The selection of party leaders in Belgium”, in The Selection of Political Party Leaders in Contemporary Parliamentary Democracies, eds J.-B. Pilet, and W. P. Cross (London: Routledge), 30–46.

Quinn, T. (2012). Electing and Ejecting Party Leaders in Britain. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9780230362789

Sandri, G., Seddone, A., and Venturino, F., (eds). (2015). Party Primaries in Comparative Perspective. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315599595

Scarrow, S. (1999). Parties and the expansion of direct democracy: who benefits? Party Polit. 5, 341–362.

Scarrow, S. E. (2015). Beyond Party Members: Changing Approaches to Partisan Mobilization. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199661862.001.0001

Schmidt, O. (2017). Om valberedningens och mina överväganden inför beslutet om medlemsomröstning inom Liberalerna.

Schmidt, O., Jernberger, A., Fogelgren, A. C., Hesselius, E., Rönnbäck, J., Persson Skandevall, L., et al. (2019). Valberedningen: Nyamko Sabuni bör bli partiledare. Svenska Dagbladet.

Sundin, M. (2019). Välj Sabuni: Ombuden ska följa medlemmarna. Expressen. Available online at: www.expressen.se/debatt/valj-sabuni-ombuden-skafolja-medlemmarna (accessed April 29, 2021).

Sundin, M., and Karlsson, L. (2015). Låt medlemmarna få rösta om partiledare. Aftonbladet. Available online at: www.aftonbladet.se/debatt/a/pyzwo/lat-medlemmarna-fa-rosta-om-partiledare (accessed November 27, 2015).

Teorell, J., Bäck, H., Hellström, J., and Lindvall, J. (2020). 134 Dagar: Om Regeringsbildningen Efter Valet 2018. Stockholm: Makadam.

Tyler, T. R. (1994). Governing, and diversity: the effect of fair decision making procedures on the legitimacy of government. Law Soc. Rev. 28, 809. doi: 10.2307/3053998

Ullenhag, E. (2019a). Jag vill att L håller fast vid januariöverenskommelsen. Dagens Nyheter. Available online at: https://www.dn.se/debatt/jag-vill-att-l-haller-fast-vid-januarioverenskommelsen/ (accessed March 26, 2021).

Ullenhag, E. (2019b). Jag ställer inte upp som partiledarkandidat. Aftonbladet. Available online at: www.aftonbladet.se/debatt/a/8mx9bw/jag-staller-inteupp-som-partiledarkandidat (accessed March 26, 2021).

Interviews

1. Carlson, Hans-Peter, chair of the regional branch in Västerbotten, June18, 2021.

2. Perhrson, Johan, parliamentarian and economic spokesman, June 24, 2021.

3. Persson Skandevall, Lars, selection committee member , April 9, 2019; May, 14, 2021.

4. Schmidt, Olle, former chair of selection committee, June 27, 2019.

5. Sundin, Mattias, former chair of the regional branch in Östergötland, former parliamentarian and economics spokesman, May 26, 2021.

6. Ullenhag, Erik, former parliamentarian, September 10, 2021.

7. Voronov, Alex, political editor of Eskilstuna-Kuriren/Strengnäs Tidning and Katrineholms-Kuriren, May 20, 21, 26, 2021.

Keywords: party, leader, selection, Sweden, Liberals, democracy

Citation: Aylott N and Bolin N (2023) Shifting perceptions of intra-party democracy: Leader selection in the Swedish Liberal Party. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1070269. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1070269

Received: 14 October 2022; Accepted: 05 January 2023;

Published: 27 January 2023.

Edited by:

Jean-Benoit Pilet, Université Libre de Bruxelles, BelgiumReviewed by:

Audrey Vandeleene, Université Libre de Bruxelles, BelgiumSorina Soare, University of Florence, Italy

Copyright © 2023 Aylott and Bolin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicholas Aylott,  nicholas.aylott@sh.se; Niklas Bolin,

nicholas.aylott@sh.se; Niklas Bolin,  niklas.bolin@miun.se

niklas.bolin@miun.se

Nicholas Aylott

Nicholas Aylott