- Political and Moral Philosophy, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

In this paper, I try to show that the recent surge of coups in Africa, like past surges, rather than resulting from cultural factors, is closely linked with the cyclic crisis of capitalism to which Africa is especially vulnerable, compounded by inadequate decolonization and by structural adjustment programs imposed by the leaders of economic globalization. Looking into the instances of coups in the African continent over the past 50 years and the history of global capitalism, I try to show that there is a pattern of coups matching capitalism crisis. I will look into the example of Guinea-Bissau to show this linkage between crisis and coups and the incidental and adaptive role of the military and political elites in the context of economic globalization. Political instability and violent takeover of political authority in Africa and beyond- are, therefore, a symptom of what has gone wrong with neoliberal globalization. Like Rodrik, I conclude that this has placed humanity before the trilemma: economic globalization, democracy and national sovereignty cannot be achieved simultaneously. To overcome it, there is a need for unfettered public debate on what form of global governance we want.

1. Introduction

Some serious harm has resulted, in the past, from taking the market mechanism to be itself-on its own-a solution to many problems, whereas it is an instrument that can be used in different ways-with or without vision, with or without social responsibility. Indeed, a social commitment to norms and priorities is essential not only for equity, but also for the efficiency of the market mechanism itself. (Sen, 2001, p. 22)

I will argue that the recent surge of coups in Africa, like past surges, is closely linked with the cyclic crisis of capitalism to which Africa is especially vulnerable. African economies are mostly extractive and are enormously dependent on imports for energy and food from the Global North. “Nearly 20 percent of African capital is owned by foreigners.” (Piketty, 2014, p. 87)

This leads to extreme inequality and consequently political instability in countries where colonial borders are still under dispute and where political decolonization did not translate into economic decolonization. Furthermore, the premise that economic liberalization would bring democracy—pushed through structural adjustment programs—has been proven wrong.

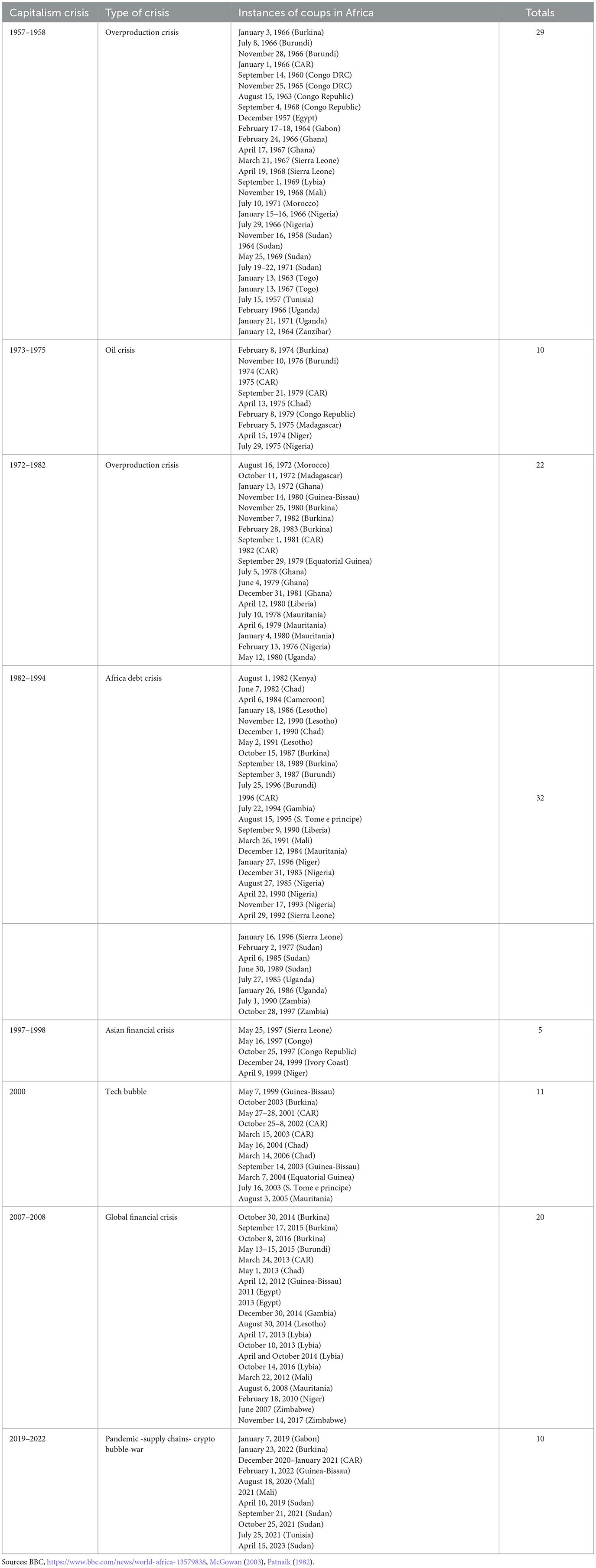

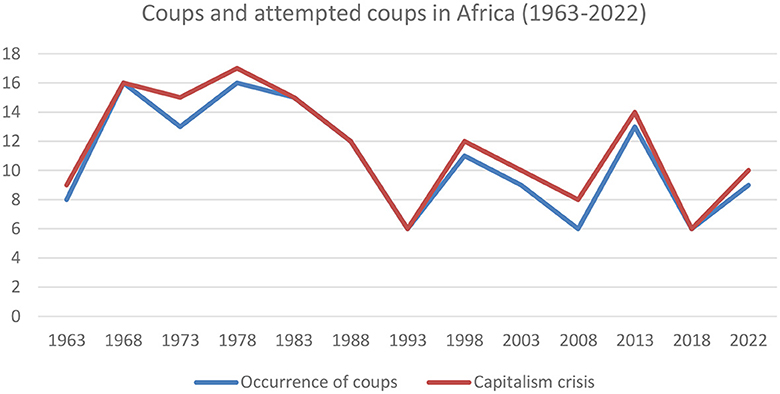

I will try to show that there is a pattern of coups matching capitalism crisis. See Table 1 and Figure 1.

Figure 1. Coups and attempted coups in Africa (1963–2022). Sources: BBC, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13579838, McGowan (2003).

One review identified 124 banking crises, 208 currency crises, and 63 sovereign debt crises between 1970 and 2008. After a lull in the early years of the new millennium, the subprime mortgage crisis centered in the United States triggered another powerful set of tremors, confronting financially open economies with a sudden dearth of foreign finance and bankrupting a few among them (Iceland, Latvia). (Rodrik, 2010, p. 109)

I will examine the case of Guinea-Bissau to show this linkage between crisis and coups. The fact the military still lead these coups is due to paradoxical factors: the symbolic capital of the armed forces as “people's revolutionary forces;” and the involvement of the military elite in a significant illicit economy, which has become very important to the survival of global capitalism.

1.1. Are there more coups in Africa than anywhere else?

The violent overthrow of political authority is as old as humankind, as David Graeber and Wengrow, have demonstrated in “The Dawn of Everything” (2021). Political authority, whatever shape it takes—autocratic, oligarchic, democratic—is a human construct.

Similarly, economic systems are a human social construction. Political and economic systems are intertwined and are created by human beings, and their existence depends on the legitimacy of those systems and, therefore, on the will of the subjects which compose them.

The relationship between states and economic activity is constitutive, not incidental. Capitalism depends not only on the organization of markets as “objective” systemic phenomena but also on social and cultural constructions like the corporation—not just as a legal entity but as an organization of work. (Calhoun et al., 2013, p. 146)

The view of political authority I am adopting in this study is that of Jean Hampton:

I'm proposing political authority is indeed invented by the people rather than derived from them. The point is that the people don't have it naturally as individuals; rather, they have to create it in order to solve certain kinds of problems that would otherwise plague them were such an authority not present. (Hampton, 1997/2018, p. 76)

Political authority is and has been constantly under dispute—peaceful and violent. The historical and geographic distribution of coup d'états is therefore much broader than the African continent. Spain and Chile have lived through 36 coups, Thailand, 22, China, 20, and Switzerland, 12.

While those are viewed as episodes in the history of those countries, the occurrence of coup d'états in the African continent since the late 1960's has raised special academic interest for several reasons: decolonization in the context of the cold war, international assistance to those young democracies (support to development and governance), and the evident linkages between political instability and underdevelopment. It is my view that, in addition to those factors, the discussion about democracy in Africa is largely informed by the evolutionist views of mainstream Western-centered anthropology, persistence of the colonialist mindset, and expansion of global capitalism.

While capitalism expansion in Africa requires political stability, because of its focus on the extraction of raw materials and cheap labor, it demands weak governance (Riddell, 1992, p. 61). This paradox generates a self-feeding cycle of instability.

If we look at the coup statistics in Africa, since the first half of the twentieth century, we see that the first surge of coups—a total of 29—took place between 1956 and 1971. During this period, in addition to the independence of many of these African states, the world lived one of the most serious overproduction crises of capitalism, boosted by technological development. Between the oil crisis of 1973–1975, through the second oil price increase of 1979–1980, until 1994 when the African Debt crisis was unfolding, there were a total of 64 coups and coup attempts in Africa (see Table 1 and McGowan, 2003).

There were two periods when oil price increases had a concentrated impact on the global economy: in 1973–74, the time of the initial OPEC increases, and in 1979–80. These, were periods of acute crisis for Africa, but there were intermediate periods of shock and stress as well, perhaps of greater significance there than elsewhere in the world. (Johnson and Wilson, 2023, p. 212)

The expansion of global capitalism was aided by the IMF and World Bank which rolled out their structural adjustment programs.

In 1978 only two African countries had agreements with the IMF. Between 1979 and 1982, however, of 48 countries 28 had negotiated at least one standby agreement or extended fund facility (EFF). There were 45 standby agreements and nine EFFs. Eight other countries drew resources from other IMF facilities, bringing the total number of African countries using IMF resources to 36. (Callaghy, 1988, p. 20)

Those programs imposed the neoliberal agenda of small and open states to countries who had not consolidated their governance structures and had incipient private sectors.

The third surge of coups (about 40 coups and attempts) comes in the aftermath of the 2007–2008 global financial crisis, which in Africa marked the growth of the continent's financial sector, thanks to the investment of major Western banks which thought local partners among the political and business elite to open new banks. According to former UNODC director Antonio Maria Costa, in an interview with Executive Intelligence Review: “massive cash flows from the global narcotics trade were brought into the banking system to rescue banks after the interbank money markets shut down.”

As African countries which had gone through structural adjustment programs had started resorting to illicit and informal business, the new financial sector (fed by the appetite of international banks) provided an open door for transnational organized crime and terrorism to finally permeate the political and economic spheres of these countries.

Therefore, what I am proposing is that the recent surge of coups in Africa is a direct effect of economic neoliberal globalization where the international borrowing system provides coup incentives because: (1) it facilitates borrowing from destructive governments; (2) it forces democratically elected governments to pay the debts of former corrupt governments; and (3) it legitimizes elites who use the coercive power of the state to get the borrowing privilege (Pogge, 2003, p. 127).

“States under strain or under disintegration, the emergence of shadow states or outright state collapse are becoming common sights in the contemporary world.” (Gowan, 2003, p. 62)

2. Guinea-Bissau: state building under economic globalization

2.1. The struggle

Guinea-Bissau, a small country on the coast of West Africa, declared its independence in September 1973, after a 13-year armed struggle against colonial Portugal. It was the only former Portuguese colony who won the war. This struggle was led by pan-Africanist Amilcar Cabral, son of Cape Verdeans born in Guinea-Bissau, who graduated from Lisbon as an agricultural engineer with a thesis about desertification—and the African Party for the Independence of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. Cabral and the PAIGC have inspired many other African countries and the fight against fascism in Portugal that culminated in the April 1974 carnation revolution.

Guinea-Bissau independence struggle unfolded against the backdrop of the cold war, and therefore, it harnessed the support of international leftwing solidarity movements and socialist countries, such as Cuba, Sweden, and the former Soviet Union.

Although influenced by Marxism and advocate of policies that could be seen as socialist inspired, Amilcar Cabral always refused such orthodoxy.

Cabral was aware of the risks of prompting another proxy war—in the context of the Cold War—and of the importance of developing an African homegrown ideology based in African culture and traditions, to which neighboring countries greatly contributed to: Senegal led by Senghor, and Guinea led by Seko Ture.

When pinned down, as inevitably happened in the context of the ideological Cold War, to state the ideological foundation of his movement, Cabral was unambiguous: “Our ideology is nationalism, to get our independence, absolutely, and to do all we can with our own forces, but to cooperate with all other peoples in order to realize the development of our country.” (Mendy, 2010, p. 14–15)

Amilcar Cabral understood culture as a product of history and that in its struggle for self-determination, the people would have to separate those aspects of culture that were “strengths” and abandon those that constituted “weaknesses” (Cabral, 2013, p. 165).

In addition to the international geopolitical constraints, and the fierce opposition of the Portuguese fascist regime and its political police (PIDE) Cabral faced many internal challenges. Guinea-Bissau was a mosaic of ethnic groups—Mandinka, Fulani, Pepel, Manjacos, Bijagos, Nalu, Mancanho, Felupe (Joola-ajamaat)—and divided into colonial imposed categories:

The Guinea-Bissau into which Amilcar Cabral was born was also a divided country, of civilizados (“civilized”) and não civilizados (“uncivilized”), of assimilados (the assimilated) and indígenas (natives) or gentios (heathens); a color-conscious compartmentalized world of brancos (whites), mestiços (mixed race), and pretos (blacks). In the 1950's, the so-called “civilized” population numbered some 8,320 individuals (Mendy, 1994, p. 311)—a mere 1.6% of the total population. They were racially identified as brancos, 27%; mestiços (the overwhelming majority of whom were Cape Verdeans), 55%; and pretos, 18%. With the stroke of a pen, the Lisbon authorities decreed “uncivilized” the indigenous populations of Guinea-Bissau, Angola and Mozambique, but not Cape Verde. (Mendy, 2010, p. 10)

While addressing these contradictions, Cabral focused and tried to keep combatants focused on the essential:

National liberation, the struggle against colonialism, working for peace and progress—independence—all these are empty words without meaning for the people, unless they are translated into a real improvement in standards of living. It is useless to liberate an area, if the people of that area are left without the basic necessities of life. (Cabral, 1979, p. 241)

This goal informed his view that in addition to destroying the colonial institutions oppressing Bissau-Guineans and Africans, the liberation movements would have to “destroy the economy of the enemy and build our own economy.” (Nzongola-Ntalaya, 2010, p. 76)

Cabral was early aware of the difficulties in responding to people's expectations, in moderating the old elite's self-interested impulses. That same elite (in this case the Cape Verdeans and mestiços) had privileges during the colonial regime and identified with the bourgeoisie in the capital and the West. Moreover, he had to deal with the new warrior elite who, in mid and late 60's, was beginning to reap the benefits of the armed struggle by assuming absolute power over the liberated areas, which led to human rights abuses over the civilian population.

To address those contradictions, the PAIGC organized its first congress in the liberated area of Cassaca in 1964. In that very tense meeting, Cabral identified the negative and opportunistic tendencies among party members: “militarism, authoritarianism, patronage, misogyny and racism” which were compounding on the weaknesses of the movement: “lack of planning, lack of funds, disagreement among leaders” (Lopes, 2010, p. 128).

Cabral, one of those privileged mestiços, was himself never put to the test of Governance as he was assassinated in January 1973 by disgruntled comrades, before independence and before he could try to build the new state and its economy. Nonetheless, he left relevant guidance to his successors:

In underlining the incompatibility between the inherited colonial economy and state machinery with the needs and aspirations of the African masses, Cabral shows that there is a choice to be made by the new ruling class, between the people and their aspirations on the one hand, and the world system and its constraints, on the other. For him, as for us today, the economic policy of the African state ought to respond to the deepest aspirations of the people, and not to the interests of the dominant classes of the world system along with the antisocial policies of the financial institutions under their control. (Nzongola-Ntalaya, 2010, p. 76)

2.2. PAIGC one-party rule, the first coup, and the structural adjustment program

Luis Cabral, who had been chosen to lead PAIGC after the death of his brother, became president of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde in 1974. The system of Government adopted was the one-party system as stated in Article Four of the country's first constitution: “Power is exercised by the working masses in close association with the PAIGC which provides political direction.” (International Crisis Group, 2008, p. 7)

Luis Cabral initiated an ambitious program of industrialization and agriculture development, in a system of centrally planned economy, which was supported by China, the Soviet Union, and the European Nordic countries. Although that period is still remembered with nostalgia by some, as the period when Guinea-Bissau had factories producing mostly everything—cars, milk, juice, beer, etc.—it is recorded by many others as a period of scarcity. Productivity was low, due to the absence of cadres, very high illiteracy rates,1 lack of infrastructure and food storage, and the contamination of farmland by landmines and other remnants of war.

Imported goods would hardly reach the rural areas, increasing the resentment of the population against the ruling elite, and subsequently against the “Cape Verdeans.” Moreover, the PAIG's wartime structure was not suited to the new context of state building.

The party's men and women, finding themselves at the head of a state without a real bureaucratic administration, resorted to nepotism and political patronage to satisfy their personal, financial, and political interests. (International Crisis Group, 2008, p. 7)2

Incipient human resources, lack of funding, and the urgency to deliver led Luis Cabral to delegate government to those closest to him neglecting the formation of a real state administration:

Most of the 16 new ministerial posts introduced upon independence were taken by party members who were told to find their own sources of finance. This enabled the PAIGC's elite to gradually obtain a monopoly on state resources. (International Crisis Group, 2008, p. 7; see text footnote 2)

Lacking the symbolic power of Amilcar Cabral, Luis Cabral was also unable to deal with the growing discontentment of former combatants, who felt neglected by the new state. Nino Vieira became their representative, and in 1980, he led a coup d'état against Luis Cabral accusing him of purges, political assassinations, and neocolonialism.

Nino Vieira, the new President of the Revolutionary Council, made a radio broadcast saying the coup aimed to 'chase off the colonialists that were still in Guinea-Bissau', and there was much talk of ending their hegemony over the mainland. (Munslow, 1981, p. 110)

This led to the breakdown of the unity between Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau, the departure of the Cape Verdean cadres, and the beginning of Nino Vieira 18 years of rule in Guinea-Bissau. The country was bankrupt.

All this happened in the aftermath of the 1973 Oil Crisis which had a devastating effect on world economy but especially in Africa, where it had a domino effect in all import prices on a continent highly dependent on imports:

The flood of high import prices that swept over African economies in the 1970's severely imbalanced their international payments accounts, knocked African development plans out of their traditional moorings, and nearly drowned the new states in a sea of debts. (Johnson and Wilson, 2023, p. 211)

In desperate need of financial assistance, Nino Vieira's government begins conversations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB) in 1981. Two years later, an “Economic Recovery Program” was approved and in 1984, a “Plan for Economic Stabilization.” In 1986, the Government passed two decrees liberalizing the economy: Decree 22/86 liberalized trade, and Decree 23/86, established a System of prices determined by market mechanisms (apart from oil and rice).

These important reforms opened the way to an agreement with the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank for starting the country's first formal Structural Adjustment Program with the support of the international financial institutions and the donors. (Aguilar and Stenman, 1997, p. 6)

This resulted in the privatization of all the state-run factories (who were mostly acquired by the former business colonial elite or by politicians), reduction in the incipient public administration body,3 hampering the state's capacity to deliver essential services to the population, establish key state institutions, undertake security sector reform, or build the capacity of its cadres.

On the other hand, the push for economic liberalization was followed by a push for democratization, by donors:

Economic liberalization, which began in 1983 with the adoption of the economic stabilization program and continued in 1986 with the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) structural adjustment program, opened the door to pressure from international donors. The country's democratization became an essential condition for the financial aid on which the country, in structural economic crisis, was totally dependent. (International Crisis Group, 2008, p. 11)

This push for democratization in the late 90's and early 2000's emerged among policymakers and academics faced with the evidence that market alone could not yield sustainable development. Amartya Sen was one of these academics arguing that democracy is intrinsic to development, countering the narrow view of economic growth and the idea that authoritarian regimes are more efficient at generating economic development. Sen argued that:

Democracy has an important instrumental value in enhancing the hearing that people get in expressing and supporting their claims to political attention (including the claims of economic needs). It gives political incentives to ruling governments to respond to the demands of people, and it makes the governors more responsible and accountable. (Sen, 2001, p. 10)

The same view was defended by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan in Address at University of Yaoundé, Cameroon (May 2, 2000):

[i]n a country where those who hold power are not accountable, but can use their power to monopolize wealth, exploit their fellow citizens and repress peaceful dissent, conflict is all too predictable and investment will be scarce.

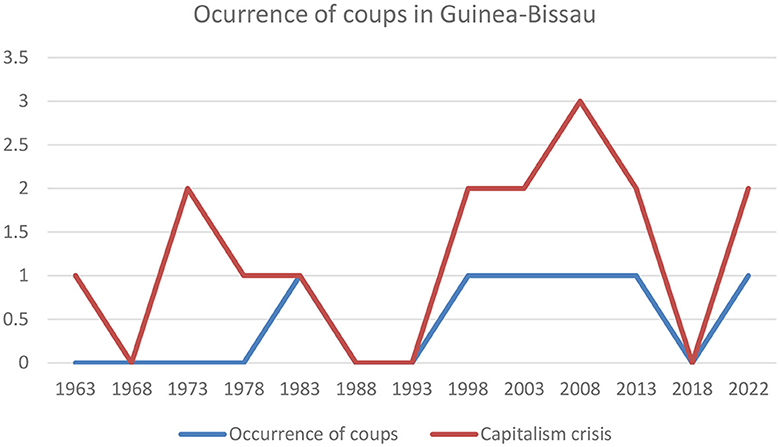

Democratization in Guinea-Bissau began in 1991 with the constitutional review which abolished the one-party system and the multi-party elections of 1994. Nonetheless, that did not put an end to violent political struggle. The country continued engulfed in a recurrent cycle of political instability. It has lived four successful coups and 16 attempts. Until the moment of writing, no government has completed a legislature and only one president has ended its term.

Human development indicators have worsened. Poverty increased between 2000 and 2010. Guinea-Bissau ranks 177 of 184 in the Human development index. According to the World Bank, poverty and inequality have worsened:

Both absolute and extreme poverty rose between 2002 and 2010 (by 3.7 and 11.5%, respectively): the country's limited economic growth had no measurable or sustained poverty reducing benefits. (…) In 2010, average consumption for the top 10% was 23 times higher than for the bottom 10%. While economic growth has benefitted the top income group, the rest of the population suffered from declining welfare. (World Bank, 2017, p. 7)

According to the international financial institutions, despite the economic growth recorded, Guinea-Bissau population, essential services, and public administration have not benefited. Also, overall external debt has increased. In general, the country's fragility remains high and is perpetuating the capturing of the state and resources by the elites.

Fragility in Guinea-Bissau manifests in a disconnect between state and society, with weak state institutions and a lack of state presence outside Bissau, which renders the state illegitimate in the eyes of many of its citizens. Furthermore, military engagement in the political and economic spheres is strong, the justice sector is weak, and the economy is poorly diversified and captured by elite interests. (…) Fragility is also the result of competition for rents among elites. Weak governance has allowed a “rentier” economy to fester, effectively diverting much of public resources toward individual private gain. (World Bank, 2017, p. 6)

The case of Guinea-Bissau seems to demonstrate Amartya Sen and Anan's argument. Despite 40 years of international assistance and structural adjustments and although Guinea-Bissau has lived periods of economic growth, this has not resulted in an improvement of people's welfare. State institutions and governance also remain weak—a trend that tends to worsen. The country seems trapped in cycles of political instability: See Figure 2 and is even at risk of being engulfed in the web of transnational organized crime and terrorism. Already back in 2007, the International Crisis Group reported:

Some donors are concerned that criminality, including drugs, risks infiltrating state structures, even if this is not yet entirely the case. Unfortunately, given the opacity of the system, it may be difficult to judge the degree of criminalization of the state before it is too late. (International Crisis Group, 2008, p. 22)

Figure 2. Occurrence of coups in Guinea-Bissau. Sources: BBC, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13579838, ICG, World Bank.

2.3. The evolving role of the military in Guinea-Bissau and beyond

Managing the expectations and the symbolic capital of the Military in Guinea-Bissau was a challenge since even before the independence. Abuses of power were frequent in the liberated areas, what prompted the Cassaca congress, where guerrilla leaders were harshly disciplined. After independence, with the Cape Verdean elite occupying Government positions and Luis Cabral decision to introduce military ranks in February 1980, the dissatisfaction among the Military—mostly from the Balanta ethnic group—grew rapidly. “The move was seen by the Balanta as yet another way of promoting Cape Verdeans to the detriment of other, more worthy soldiers.” (International Crisis Group, 2008, p. 9)

The economic crisis and the harsh repression over opponents compounded the divisions so, when the PAIGC passed a rule preventing natural Bissau-Guineans from occupying the presidency in Cape Verde, the Bissau Guinean opposition, led by Nino Vieira, made the move toward the first coup. “Nino Vieira, who already had the active support of the army and the population, took advantage of the situation to lead a coup d'état on 14 November 1980.” (International Crisis Group, 2008, p. 9)

During the subsequent 18 years of Nino Vieira's autocratic rule, power was in the hands of the military. Nino Vieira used his capital as independence hero to secure his own power.

This period was peppered with real or imagined attempted coups d'état and power was increasingly concentrated in the hands of the military. To hold on to the presidency, Vieira had to constantly maintain his popularity with the army while eliminating his enemies. (International Crisis Group, 2008, The First Reign of Nino Vieira, p. 10)

Eventually, Vieira who also had to impose economic austerity, prescribed by the Structural Adjustments and debt crisis, and manage the political and military elite competition for resources, was not able to avert the military uprising in 1998. This resulted in a year-long armed conflict and consequent destruction of the country's infrastructure, 100's of deaths, 1,000's of displaced people, and mass emigration.

It is important to note that the conflict was triggered by mutual accusations (between Nino Vieira and Ansumane Mane, the head of the Armed Forces) of involvement in arms trade with the Movement of Democratic Forces of Casamance (MFDC) from the Senegalese region of Casamance (who have been fighting for independence since 1982).

President Abdou Diouf put pressure on Vieira to end the weapons trafficking between some members of the Bissau-Guinean army and Casamance rebels of the Mouvement des forces démocratiques de Casamance (MFDC). In reality, Nino Vieira and his entourage were directly involved in the trafficking. To protect himself from suspicion, he diverted blame to his right-hand man and chief of staff, General Ansumane Mané. (International Crisis Group, 2008, p. 12)

The conflict also led to drainage of human resources leaving the country even more vulnerable economically, more dependent on external financial resources. This led to highly dysfunctional dynamics between military, political, and business elites, which exchanged roles, influence, and favor to seize the scarce resources from international donors or foreign business (Sucuma, 2021, p. 16). Access to government positions meant access to resources and business. And there are only two ways to get into government: elections or forceful power takeover. While elections became a business by attracting funds from donors, they turned into a reason to look for other sources of funding.

Structural adjustment orientated the politico-military elite even further toward a reliance on non-domestic resource flows. These resources began to dry up by the late 1990's, which introduced a new fragility into Guinea-Bissau politics as, over time, a series of competing protection networks coalesced around a new and illicit flow: cocaine from Latin America. (Shaw, 2015, p. 344)

According to Mark Shaw, the increasing involvement of the country's elite in drug trafficking reached a peak in 2009 with the assassinations of Nino Vieira (who returned to power in 2005) and General Tagme NaWaye, whose involvement with drug trafficking had been documented by the largely underfunded judicial police.

In the years that followed, the military held a tighter grip on power and to controlling all revenue sources. After the 2012 coup d'état led by another General, Antonio Indjai, Admiral Bubo Natchuto was arrested by the American authorities in international waters in a covert operation where DEA agents pretended to be FARC asked Indjai to provide arms in exchange for cocaine. “According to prosecutors, Bubo suggested to the DEA agents that the timing to engage in such activity was very good in the period after the 2012 coup, given who was in charge of the country” (Shaw, 2015).

Mark Shaw, who supported his research with hundreds of interviews with military, civil society, media, and politicians in Guinea-Bissau, further asserted that the involvement of the political-military and business elite in drug trafficking expanded to a broader range of activities in the second decade of the twenty-first century, “most notably the smuggling of people and the illegal exploitation of the country's timber resources.” (Shaw, p. 358)

This was at the same time enabled and fueled by the rapidly weakening of state institutions and the rule of law.

Shaw demonstrates that the role of the military evolved over time and became central in a protection economy serving many other actors.

Guinea-Bissau did not possess a coherent state and it is more accurate to describe control over trafficking as a result of a protection network that evolved within a small elite, increasingly starved of external resources in the wake of the end of the Cold War and structural adjustment policies. Elements of that elite needed resources to ensure political survival; little attention was paid to whether those resources were licit or illicit. (Shaw, 2015, p. 360)

The transformation of the military into a force to protect and maintain illegal resource streams for themselves and the economic and political elite may seem unique to Guinea-Bissau, and that is why the country has often received the epithet of a narco-state. However, the root causes of this process and its manifestations in coup d'états are not unique to this tinny West African state nor the African continent.

Patrick McGowen, in his early study on “African military coups d'état, 1956–2001: frequency, trends and distribution,” concluded that:

(…) no trends of increasing or decreasing coup behavior are evident, except that up to around 1975 as decolonization progressed, TMIS [Total Military Intervention Score] also increased; and that West Africa is the predominant center of coup activity in SSA, although all African regions have experienced coups. States that have been free of significant PI [Political Instability] since 1990 are examined and those with institutionalized democratic traditions appear less prone to coups. (McGowan, 2003, p. 1)

Defining a coup as a change in power from the top, which may or not change state policies and or imply redistribution, McGowan attributes the incidence of coups mostly to internal causes, although he states that further research is needed. He advances that “rent seeking behavior of African militaries and their elite constituencies explains the negative impact of military-led PI and military rule on economic growth and human development” (McGowan, 2003, p. 341). Moreover, he does not find evidence that global conditions “such as the ending of the Cold War between 1989 and 1991 or the collapse of commodity prices in the mid-1980's are major influences on coup activity” (McGowan, 2003, p. 355).

Two decades later, Basedau (2020) examined the political instability trends in sub-Saharan Africa and found that the numbers show a decreasing number of military coups “although the curve may have flattened in the last decade before 2020,” in spite of the re-militarization around the world in recent years.

However, less visible forms of intervention by the military in politics persist. In almost 40 per cent of sub-Saharan cases, the military remains a powerful actor in politics; in 15 out of 49 countries, “generals in suits” rule as heads of government. (Basedau, 2020, p. 2)

As for the causes for involvement of the military in politics, Basedau offers more simple explanation: the military get involved when countries face political and socioeconomic problems (Basedau, 2020). In my view, this involvement can be more overt (like in the pre- and post-independence period) and more or less self-interested (when the armed forces intervened to prevent unconstitutional maneuvers from politicians to remain in power or to voice people's discontentment with economic hardship).

In any case, the fact that the military have real coercive power turns them into both predator and prey of other interest groups, domestic or foreign.

What history has shown is that this coercive power is essential to ensure the conditions for economic exchange and it determines the distribution of goods. Market exchange, and especially long-distance trade, cannot exist without rules imposed from somewhere. (Rodrik, 2010, p. 8–9)

Those imposing the rules can be a state, colonial state, or corporation, like the chartered trade monopolies which controlled global trade between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries (e.g., East India Company).

Similarly, military force has been used all over the world to impose economic reforms favoring free market policies such as the Structural Adjustment Programs. As it was in Chile, under the Pinochet regime, authoritarian conditions are required for the implementation of its true vision (Klein, 2010).

2.4. The impact of SAPs in Africa

The situation in Guinea-Bissau is common to many other African States who went through structural adjustments programs (SAPs). There is extensive literature and discussion about the results and impact of the Structural Adjustment Programs in Africa. For a long time, arguments fell generally in two camps: (1) Those who argue that SAPs have not yielded positive results because the continent is in a poverty trap due to weak African leadership and governance, poor infrastructure, low literacy, and a culture of corruption and of violence (Ikome, 2007, p. 16); and (2) those who claim that SAPs could not have good results because they actually contribute, if not create that poverty trap, by forcing these countries to open their economies before having created strong institutions.

American economist Sachs et al. (2004) is one of the top proponents of the first camp. In 1996, in the Economist,4 in face of the disastrous effects of the SAPs in Africa, he highlighted the good results in Asia (despite the 97 financial crisis) and argued that “It can be done” in Africa if the IMF and WB correct the programs to promote more openness to trade, more market incentives national saving. Later in 2011, in Ending Africa's Poverty Trap Sachs argued that the programs were not having good results because of Africa's “poor infrastructure and weak human capital” and that what was necessary was a “big push” in public investment.

Another prominent economist, Nobel winner, Joseph Stiglitz, who was also chief economist at the World Bank (2023), has a more nuanced view of the SAP imposed reforms:

Some of the structural reforms pushed during the 1990's, such as reforms that encouraged countries to live within their means, have had positive impacts. But other central reforms, such as capital and financial market liberalization, have exposed developing countries to external shocks, and also reduced their capacity to respond to them. In addition, some reforms like privatization were implemented without the proper institutional framework in place, resulting in inefficient allocations of resources (due for example, to unbridled monopoly power) and widespread corruption (so much so that privatizations in many countries were nicknamed “briberizations”). (Stiglitz et al., 2006, p. 217–218)

So, not only SAPs exposed countries to external shocks, but they boosted a culture of corruption in countries like Guinea-Bissau, where elites were already prone to appropriating the national resources for their own benefit.

Moreover, proponents of the second camp also make a very substantive claim that:

The poverty, weak institutions, and conflict, described in the preceding sections, are worsened by the structural adjustment programs that have been put in place in African countries by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Economic reforms, culminating in privatization, encapsulate how a combination of excessive deregulation and a lack of balancing safeguards have worsened poverty and deprived governments of the resources required to build strong national institutions, including political parties, that promote democracy and development. Structural adjustment programs demand that African countries, irrespective of their level of development and industrial base, should liberalize their trade regimes in order to expand production and exports, and consequently promote their economic development. That is, they should integrate into the global economy. (Ndulo, 2003, p. 363)

One can safely conclude that these programs, reportedly created with the goal of “stabilizing,” ended up destabilizing countries, while integrating them into the globalized economy. By opening them to economic globalization, they've also become permeable to economic shocks elsewhere. By liberalizing trade, these countries also became unable to develop their own industries and agriculture production, becoming condemned to a basic extractive economy where the only thing they can trade are their natural resources or cash crops.

It is, therefore, unsurprising that, at each shock of the global economy, these countries suffer serious aftershocks for which they have no capable political or social institutions to respond to.

That there is a correlation between global economic crisis and waves of coup d'états and/or political, military, and civil unrest seems evident.

Craig Calhoun also recognizes this correlation between the economy, which is not unique to Africa.

It is the intersection of economic with political crises that threatens it most, or the erosion of the implicit bargain in which people accept damages to society or environment in the pursuit of growth. Europe raises the specter of no growth capitalism—almost a contradiction in terms—and it's not clear how it will cope. Asia seems still to offer growth, but in combination with volatile and vulnerable politics. And political unrest is recurrent, both where faltering growth brings disappointment to those with rising expectations and where elected leaders seek to diminish public freedoms and quash dissent. (Calhoun et al., 2013, p. 146)

3. The Washington Consensus and economic globalization

But how did the IMF and the World Bank, created like the UN in the aftermath of the Second World War, with the goal of preventing global economic shocks (like the 30's great depression) which could pose risks to peace, ended up proposing and imposing such programs?

In 1944, a group of 44 allied countries came together in New Hampshire at a conference to agree on a regulation of the international financial and monetary system to prevent problems such as those created by the abandonment of the Gold Standard, the Great Depression, and to prevent crisis such as the one faced by Germany in the interwar period (forced to pay reparations after the I World War, Germany plunged into a hyperinflation crisis which contributed to the rise of fascism).

The goal was to foster multilateral economic cooperation. At that conference, the Bretton Wood system was created consisting of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.5

The genius of the system was that it achieved a balance that served multiple objectives admirably well. Some of the most egregious restrictions on trade flows were removed, while leaving governments free to run their own independent economic policies and to erect their preferred versions of the welfare state. (Rodrik, 2010, Intro. Par. 26)

Jonh Manyard Keynes, heading the UK delegation to the conference, “was convinced that the world had finally recognized the political perils of leaving the market to regulate itself” (Klein, 2010, p. 162–163). However, Keynes was apparently wrong. The power-sharing agreement of the Bretton Woods system was based on the size of each country's economy, which gave the US veto over major decisions and disproportionate power also to Europe and Japan.

That meant that when Reagan and Thatcher came to power in the eighties, their highly ideological administrations were essentially able to harness the two institutions for their own ends. (Klein, 2010, p. 163).

Although ideology played a role in the transformation and end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, its fate was sealed by the fact that the regime depended on the so-called “dollar-exchange rate,” making the US the global supplier of the “global currency” (as we have seen pegged to gold).

In 1971, confronted with growing demands from foreign countries to convert their dollar holdings to gold, President Richard Nixon and his Treasury secretary John Connolly faced a choice: either tighten domestic economic policies or suspend the convertibility of dollars to gold at a fixed rate. They naturally chose the second option. (Rodrik, 2010, p. 100)

The decision to move to floating currencies was taken officially in 1973, pushed by the increasing mobility of capital and by the oil crisis of the 1970's, which as we have seen had a severe impact all over the world especially in Africa.

This regime was superseded in the 1980's and 1990's by a more ambitious agenda of economic liberalization and deep integration—an effort to establish what we may call hyperglobalization. Trade agreements now extended beyond their traditional focus on import restrictions and impinged on domestic policies; controls on international capital markets were removed; and developing nations came under severe pressure to open their markets to foreign trade and investment. In effect, economic globalization became an end in itself. (Rodrik, 2010, Intro. Par. 26)

This “ambitious agenda” became known as the “Washington Consensus.” Williamson (2004) was the author of the background study with this same title, presented to a conference at the Institute for International Economics convened “in order to explore how extensive were the policy reforms that were then ongoing in Latin America.” The study presented a 10-point agenda listing policies, which included “abolition of trade barriers, privatization of state enterprises, abolition of regulations that restrict competition, and financial liberalization.” Although Williamson, said in 2005, he never intended to make it a universal policy, these points which became the core of every Structural Adjustment Program that the IMF and World Bank implemented in Latin America and Africa, from 1983 onwards.

For the next two decades, every country that came to the fund for a major loan was informed that it needed to revamp its economy from top to bottom. (…) The principle was simple: countries in crisis desperately need emergency aid to stabilize their currencies. When privatization and free-trade policies are packaged together with a financial bailout, countries have little choice but to accept the whole package. (Klein, 2010, p. 164)

The effects of the SPA package were then compounded by World Trade Organization (2023) rules, which impose unattainable conditions on products from developing countries, WTO Agreement on Intellectual property rights prevents these from copying essential technology from rich countries.

The countries of the periphery not only failed to industrialize, but they also actually lost whatever industry they had. They deindustrialized. (Rodrik, 2010, p. 140)

By hampering the states' capacity to control their own development and to protect their populations from external shocks, the liberalization agenda ends up fueling conflict (between people and elites, among social classes, and between countries). This became evident in Guinea-Bissau, and I believe explains to some extent why the surges of coups in Africa match periods of economic upheaval which is felt much more strongly in these countries. Why does it hit them harder is explained by the colonization past, which favored extractive economies, by the short state-building and democratic experience.

Guinea-Bissau institutions were progressively weakened by SAPs and allowed for the growth of the informal economic sector, which, in turn, compounded the deterioration of the same state institutions and civil-military unrest. Craig Calhoun offers

The informal sector is not just local community networks and other face-to-face alternatives to formal markets and formal institutions. It also has a large-scale dimension of transnational capitalist structures that operate at least partially outside state institutions and laws. The latter include money-laundering, banking, and investments backed up by force as well as contracts. They include tax-evasion, trafficking, and a range of illicit flows—from minerals (blood diamonds or coltan), to weapons (small arms mostly, but also tanks, aircraft, and missiles), to drugs, to people. (Calhoun et al., 2013, p. 157)

4. Market as ideology—globalization, states, or democracy: the trilemma

Both Naomi Klein and Dani Rodrik spoke of an ideologic turn at the time of the Washington Consensus, which was promoted by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. Klein called it a “corporate crusade” designed by the Chicago School of Economics. She also called it the emergence of disaster capitalism. For Rodrik, it was a system of belief that has been called “market fundamentalism, or neoliberalism.”

Whatever the appellation, this belief system combined excessive optimism about what markets could achieve on their own with a very bleak view of the capacity of governments to act in socially desirable ways. Governments stood in the way of markets instead of being indispensable to their functioning, and accordingly had to be cut down to size. (Rodrik, 2010, p. 76)

For Rodrik, there is, therefore, a tension between democracy, national sovereignty, and economic hyperglobalization and that the latter poses a trilemma: We cannot have sovereign states, democracy, and economic globalization simultaneously. Humanity will have to choose between either economic globalization and states without democracy, or states and democracy without economic globalization, or alternatively, we can have global democracy with a global economy.

Must we give up on democracy if we want to strive for a fully globalized world economy? There is actually a way out. We can drop nation states rather than democratic politics. This is the “global governance” option. Robust global institutions with regulatory and standard-setting powers would align legal and political jurisdictions with the reach of markets and remove the transaction costs associated with national borders. If they could be endowed with adequate accountability and legitimacy in addition, politics need not, and would not, shrink: it would relocate to the global level. (Rodrik, 2010, p. 202)

I would argue that the economic hyperglobalization that Rodrik describes is in fact the expansion of capitalism, as an ideology6 that views property as sacred. For this purpose, it is also important to consider some definitions of capitalism.

According to historian Ellen Meiksins Wood:

Capitalism is a system in which goods and services, down to the most necessities of life, are produced for profitable exchange, where even human labor-power is a commodity for sale in the market, and where all economic actors are dependent on the market. (Wood, 2002, p. 78)

Nancy Fraser and Rahel Jaeggi supplement that Capitalism in its complete form ends up regulating all social relations:

This unique system of market-dependence means that the dictates of the capitalist market—its imperatives of competition, accumulation, profit-maximization, and increasing labor-productivity—regulate not only all economic transactions but social relations in general. (Fraser and Jaeggi, 2018, p. 119)

Thomas Picketty defines capitalism as a particular form of proprietarianism:

Generally speaking, whether we are talking about the capitalism of the first industrial and financial globalization (in the Belle Époque, 1880–1914) or the globalized digital hypercapitalism that began around 1990 and continues to this day, capitalism can be seen as a historical movement that seeks constantly to expand the limits of private property and asset accumulation beyond traditional forms of ownership and existing state boundaries. It is a movement that depends on advances in transport and communication, which enable it to increase global trade, output, and accumulation. At a still more fundamental level, it depends on the development of an increasingly sophisticated and globalized legal system, which “codifies” different forms of material and immaterial property so as to protect ownership claims as long as possible while concealing its activities from those who might wish to challenge those claims (starting with people who own nothing) as well as from states and national courts. (Piketty, 2020, p. 154)

Seen as a vision of society that sets property as a chief value and that tries to impose it, it is understandable that capitalism is incompatible with democracy. This only becomes more visible once it expands across state borders. In fact, Stiglitz reminded us that although the United States plays a major role in the top institutions responsible for advancing capitalism around the world, its actions have not benefited the American people, which he says are not being heard.

When the IMF pushed for capital market liberalization, such policies benefited Wall Street but not the American people. (…) Similarly, in the WTO, drug companies might gain from the stronger protection of intellectual property rights. Such measures enable drug companies in poorest countries to insist that drug prices be so high that people dying for those drugs couldn't afford them. Yet that was not consonant with the interests of the American people, and when the American people saw that people were being deprived of life-saving drugs, in South Africa and elsewhere, their voices were heard very strongly and policy was reversed. I do think American voices are heard, but which of our voices? Often, the voices of special interests drown out what most Americans actually believe. (Stiglitz and Schoenfelder, 2003, p. 38)

Understanding capitalism as an ideology that for the past 40 years has been increasingly imposed by the most powerful states, with coercive power, to the rest of the world, should allow us to open the debate about how we want to organize our societies and about the world we want to live in. The options are those to which Rodrik points to: (1) dropping democracy and replacing it with national or global forms of authoritarian regimes, (2) creating democratic global governance institutions, or (3) limiting globalization and leaving the discussion to each state.

Whatever the outcome will be, it is important to note that it is not a choice about the economy only, because markets do not operate in the void, they are a social construct, they need institutions to bring trust into commercial relations, and they are not moral free. We should remember that the colonialist system used racism to justify the exploitation of other peoples and countries.

5. Global capitalism or global ethics

We have witnessed the expansion of capitalism and its policies being implemented not only in Africa and the South but also in Europe in the aftermath of the 2008 American subprime crisis, and we are likely to see it again soon in the 20's of the twenty-first century.

The results are visible, not only in the surge of coups and political violence in Africa and beyond but also in a receding democracy and rule of law everywhere, a resurgence of authoritarian regimes in Europe and the rising inequality.

Freedom House and the Economist Intelligence Unit reported in 2021 and 2022 that democracy is receding. This is visible in constriction of the public debate, decreased citizen participation, and the rise of identity politics.

In sum, we witness the deterioration of the public sphere, as described by Habermas, where the laws of the market, of commodity exchange have pervaded all other social spheres including that of the private people as a public, which led to the replacement of rational debate by consumption. (Habermas, 1989, p. 161–162)

This trend is followed by the proliferation of conflict and a receding international rule of law, as reported in 2019 by the “Security Council report,” an NGO that monitors the UN Security Council, responsible for maintaining international peace and security.

As Thomas Picketty showed in “Capital in the twenty-first century” and “Capital and ideology,” socioeconomic inequality and poverty have increased exponentially in all regions of the world.

The 2022 World Inequality Report estimates that the share of the bottom 50% of the world in total global wealth is 2% by their estimates, while the share of the top 10% is 76%. “Since wealth is a major source of future economic gains, and increasingly, of power and influence, this presages further increases in inequality.”7

In my view, these are all interrelated “pathologies” and can be explained by what historian Samuel Moyn calls the dismissal of an idea of global egalitarianism which took place in the aftermath of the second world war and consolidated during the cold war—the end of utopia—cosmopolitanism as an unfulfillable dream (Moyn, 2010). According to Moyn, this was when liberalism gave place to neoliberalism. (Moynn, 2018, Chapter 6)

This was, says Moyn, a result of the trauma of the Holocaust, the fear of totalitarianism, and by the confrontation of two cosmopolitanisms: nationalist welfarism, embraced by the left and the global south in their struggle for self-determination against colonialism, and supranational globalism, embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 (United Nations, 1948) and Moyn (2014, p. 368–384).

According to Moyn national welfarism won the confrontation, and international human rights were cut off from the dream of global social justice.

Not surprisingly, this period was also marked by the rise of political realism, the adoption of the market economy as dogma, the death of ideology, and the emergence of a notion of self that is atomized, individualist—“unencumbered self,” according to Sandel (1984) and one of “The Malaises of Modernity,” according to Charles Taylor (Taylor, 1991/2018).

In addition to Sandel and Taylor, there have been multiple attempts at finding a language to mediate cultural difference (Taylor, 1995) and restoring a global moral framework on which can be built global democratic institutions to ensure universal human rights and global social justice.

Sen et al have shown that it is possible to find common moral ground across human cultures. “Human Rights can, therefore, be directly grounded in values without becoming culturally limited” (Griffin, 2008, p.27). This can be done by identifying what makes a life valuable and what are the essential circumstances for a good life: human capabilities and basic freedoms (Nussbaum and Sen, 1993, p. 256–260; Sen, 1999).

From the perspective of political theory, the human rights language emerged in a historic process of social and political struggles, which led to the development of a contractual notion of political authority based on the idea that human beings are deserving of equal respect and have rights because they have dignity.

In this view, the development of the human rights language is inextricable from the social processes, which led to the formation of the modern state, and which continue to push toward some form of global political authority. The current pressing question is whether this global political authority will be consensual, and therefore contractarian, and democratic or will it be a form of mastery? The latter would imply adopting notions of natural subordination and a total rejection of human rights.

What I propose is the development of a global political authority that is grounded on the idea that all human beings have equal dignity and are equally deserving of respect and recognition. Following Jean Hampton, a consent-based form of political authority that requires moral legitimacy, and therefore, democratic. (Hampton, 1997/2018, p. 70)

This will require the development of institutions, including the media, that allow for unfettered public debate—a real market of ideas—and prevent what Chomsky and Habermas called “manufactured consent.” “The press and broadcast media serve less as organs of public information and debate than as technologies for managing consensus and promoting consumer culture.” (Habermas, 1989, p. 23)

The alternative is the capitalist cosmopolis, with a different moral framework, and a different form of political authority. A moral framework that accepts that some human beings are superior to others, maybe because they have superior knowledge of the workings of the markets, and a form of political authority that Aristotle would describe as oligarchy.

6. Conclusion

The recent surge in coup d'etats in the African continent contradicted the expectations of the late years of the twentieth century that economic liberalization and democracy would bring peace and prosperity to the African Continent. The narrative that this was due to internal social and cultural factors, so popular during the colonial period, gained new traction.

However, we have seen that the violent overthrow of political authority is a human universal phenomenon. I believe have shown that the surges of coups d'états are closely linked with economic globalization and its cyclic crisis. Examining the case of Guinea-Bissau—one of the last African states gaining independence—has allowed us to see that Sub-Saharan African states are more vulnerable to the crisis of capitalism because they did not have the time to freely build neither their economic systems not their political systems. Having just emerged from costly and many times bloody independence struggles, and before they could strengthen the rule of law to industrialize and transform their inherited extractive economies, they were open to the free market and the shocks of capitalism, through Structural Adjustment programs.

Disgruntled military elites and desperate business and political elites took over and became prey to international borrowing systems that perpetuate the cycles of instability and poverty. We have also seen that the role of the military has changed over time and that, because of their coercive power, they can be used to impose the trade rules or rise to create the rules themselves and control the resource streams, whether legal or illegal.

By assessing the drivers of economic globalization, I also tried to demonstrate that this dynamic is not unique to Africa but extensive to other parts of the globe, even those who thought to have solid democratic regimes.

Calhoun et al. (2022) in their work “Degenerations of Democracy” acknowledge that “Contemporary democracies are being corrupted and eroded from within rather than being suspended and dismantled from without.” They identify meritocracy, politics, changes in the media institutions (new media and loss of economic independence of traditional media), and neoliberalism as the causes for degeneration.

They claim that “is not new for capitalism at once to deliver some of what democrats want and to pursue structural rearrangements antithetical to the stability of democracy” and that it is still possible to compromise.

They call for a new compromise, a renewal of solidarity and social movements, local, national, and global to address the environmental, social, and political challenges that societies face today. This, they argue, will mean a regeneration of democracy.

My view is that the compromise must be an ethical compromise, based on human rights. Unless we are able to build global institutions grounded on human rights, we will be witnessing the collapse of more states, armed conflict, and the destruction of life-supporting systems.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^A 99% illiteracy rate on the mainland contrasted markedly with the relatively well-educated Cape Verdeans. Racial differences were therefore exacerbated by educational one, Munslow (1981).

2. ^Guinea-Bissau, in need of a state: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep38356.6.

3. ^The village committees, the basis of state administrative structure, were either removed from local politics or dominated by traditional village chiefs without ties to the national government. Just as under Portuguese rule when the rural population had had little contact with the colonial administration, so too after independence they had little to do with the PAIGC. The state was therefore kept separate from the social and political fabric of the countryside, limiting its ability to establish an effective government.

4. ^https://www.jeffsachs.org/newspaper-articles/jpezmar9bcgl8y8mcz4hychamkxzrw

5. ^The IMF came into formal existence in December 1945, when its first 29 member countries signed its Articles of Agreement. The countries agreed to keep their currencies fixed but adjustable (within a 1 percent band) to the dollar, and the dollar was fixed to gold at $35 an ounce. To this day, when a country joins the IMF, it receives a quota based on its relative position in the world economy, which determines how much it contributes to the fund https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/bretton-woods-created.

6. ^Following Thomas Piketty, I understand ideology as a set of ideas and discourses describing how society should be structured, with social, economic, and political dimensions. “It is an attempt to respond to a broad set of questions concerning the desirable or ideal organization of a society” (Piketty, 2020, p. 3–4).

7. ^https://wir2022.wid.world/www-site/uploads/2022/01/Summary_WorldInequalityReport2022_English.pdf

References

Aguilar, R., and Stenman, Å. (1997). Guinea-Bissau: From structural adjustment to economic integration. Africa Spectr. 32, 71–96.

Basedau, M. (2020). A Force (Still) to Be Reckoned With: The Military in African Politics. German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA). Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep24790 (accessed June 30, 2023).

Cabral, A. (2013). “Unidade e Luta,” in Obras escolhidas, Coordination Mário de Andrade (Cidade da Praia: Fundação Amílcar Cabral).

Calhoun, C., Derluguian, G. M., Mann, M., Collins, R., and Wallerstein, I. (2013). Does Capitalism Have a Future? New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Calhoun, C., Taylor, C., and Gaonkar, D. P. (2022). Degenerations of Democracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Callaghy, T. M. (1988). Debt and structural adjustment in Africa: realities and possibilities. J. Opin. 16, 11–18. doi: 10.2307/1166952

Fraser, N., and Jaeggi, R. (2018). Capitalism: A Conversation in Critical Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gowan, P. (2003). “The new liberal cosmopolitanism,” in Debating Cosmopolitics, ed D. Archibugi (New York, NY; London: Verso), 51-66.

Hampton, J. (1997/2018). Political Philosophy (Dimensions of Philosophy Series). New York, NY: Routledge.

Ikome, F. N. (2007). The African State and the Coup Culture: Report Title: GOOD COUPS AND BAD COUPS Report Subtitle: The Limits of the African Union's Injunction on Unconstitutional Changes of Power in Africa Report Author(s): Institute for Global Dialogue. Available online at: http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep07759.6 (accessed June 30, 2023).

International Crisis Group (2008). “New Momentum?” Guinea-Bissau: In Need of A State. 18–23. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep38356.9 (accessed June 29, 2023).

Johnson, W. R., and Wilson, E. J. (2023). The “oil crises” and African economies: oil wave on a tidal flood of industrial price inflation. Daedalus 111, 211–241. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20024792

Klein, N. (2010). Shock Doctrine. The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York, NY: Henry-Holt & Company.

Lopes, C. (ed.)., (2010). “Amilcar Cabral and the Liberation of Guinea-Bissau: context, challenges and lessons for effective African leadership,” in Africa's Contemporary Challenges (New York, NY: Routledge), 6–19.

McGowan, P. J. (2003). African military coups d'état, 1956–2001: Frequency, trends and distribution. J. Modern Afri. Stud. 41, 339–370. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X0300435X

Mendy, P. K. (2010). “Amilcar Cabral and the Liberation of Guinea-Bissau: context, challenges and lessons for effective African leadership,” in Africa's Contemporary Challenges, ed C. Lopes (New York, NY: Routledge), 6–19.

Moyn, S. (2010). The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Moyn, S. (2014). The universal declaration of human rights of 1948 in the history of cosmopolitanism. Crit. Inq. 40, 365–384. doi: 10.1086/676412

Moynn, S. (2018). Not Enough Human Rights in an Unequal World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Munslow, B. (1981). The 1980 coup in Guinea Bissau. Rev. Afri. Polit. Econ. 21, 109–113. doi: 10.1080/03056248108703470

Ndulo (2003). The democratization process and structural adjustment in Africa. Ind. J. Glob. Legal Stud. 10, 315. doi: 10.2979/gls.2003.10.1.315

Nzongola-Ntalaya, G. (2010). “Challenges to state building in Africa,” in Africa's Contemporary Challenges, ed C. Lopes (New York, NY: Routledge), 69–86.

Patnaik, P. (1982). On the economic crisis of world capitalism. Soc. Scientist 10, 19. doi: 10.2307/3520256

Pogge, T. (2003). “The influence of the global on the prospects for genuine democracy in developing countries,” in Debating Cosmopolitics, ed D. Archibugi (New York, NY; London: Verso), 117–141.

Riddell, J. B. (1992). Things fall apart again: Structural adjustment programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Modern Afri. Stud. 30, 53–68. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X00007722

Rodrik, D. (2010). The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Sachs, J., McArthur, J. W., Schmidt-Traub, G., Kruk, M., Bahadur, C., Faye, M., et al. (2004). Ending Africa's poverty trap. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 2004, 117–216. doi: 10.1353/eca.2004.0018

Sandel, M. (1984). The procedural republic and the unencumbered self. Polit. Theory 12, 81–96. doi: 10.1177/0090591784012001005

Sen, A. (2001). “Chapter 2: Democracy and social justice,” in Democracy, Market Economics and Development An Asian Perspective, eds F. Iqbal and J. I. You (Washington, DC: The World Bank), 7–24. Available online at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/542051468748763203/Democracy-market-economics-and-development-an-Asian-perspective

Shaw, M. (2015). Drug trafficking in Guinea-Bissau, 1998–2014: The evolution of an elite protection network. J. Modern Afri. Stud. 53, 339–364. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X15000361

Stiglitz, J., and Schoenfelder, L. (2003). Challenging the Washington Consensus. Brown J. World Aff. 9, 3340. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24590462 (accessed June 30, 2023).

Stiglitz, J. E. (2006). Stability with Growth: Macroeconomics, Liberalization and Development (Initiative for Policy Dialogue), 1st Edn. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Sucuma, A. (2021). Política e Democracia na Guiné-Bissau pós-colonial. Africa Dev. 46, 37–70. doi: 10.57054/ad.v46i2.1182

United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed June 30, 2023).

Williamson, J. (2004). The strange history of the Washington consensus. J. Post Keynes. Econ. 27, 195–206. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4538920

World Bank (2017). Country Partnership Framework 2018-2021. World Bank. Available online at: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/874941497621490526-0010022017/original/GuineaBissauCountryPartnershipFrameworkF18F21.pdf (accessed June 30, 2023).

World Bank (2023). The World Bank in Guinea-Bissau. Available online at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/guineabissau (Accessed June 30, 2023).

World Trade Organization (2023). World Health Organization. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/e-coli (accessed June 30, 2023).

Keywords: capitalism, colonialism, globalization, democracy, coup d'etat, Africa, neoliberalism

Citation: Alhinho J (2023) Global capitalism crisis fueling coups and instability in Africa. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1059151. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1059151

Received: 30 September 2022; Accepted: 23 May 2023;

Published: 27 July 2023.

Edited by:

Luca Bussotti, Federal University of Pernambuco, BrazilReviewed by:

Ernesto Vivares, Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences Headquarters Ecuador, EcuadorMarc Jacquinet, Universidade Aberta, Portugal

Copyright © 2023 Alhinho. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Júlia Alhinho, anVsaWFhbGhpbmhvQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Júlia Alhinho

Júlia Alhinho