95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 26 June 2023

Sec. Peace and Democracy

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1049938

This article is part of the Research Topic Israel/Palestine: The One-State Reality Implications and Dynamics View all 8 articles

In recent years, many academics as well as local actors have started to question the feasibility of a two-state solution for Israel and Palestine. Increased Israeli unilateralism, expansionism as well as weak Palestinian institutions have instead pointed toward a “one-state-reality” where Israel is in de facto control over all lands. This in turn reveals a paradox, where international policymakers, most prominently in the EU and the US, and international organizations like the UN, seem determined to insist on a two-state solution, even though all facts on the ground indicate a move away from such a vision where the egalitarian principles inherent in the two-state solution exists in constant tension with expansionist attempts to establish Israeli sovereignty also on Palestinian land. This article unpacks various visions for the future in Israel-Palestine, based on egalitarian principles on the one hand and expansionist ones on the other and display how they current co-exist in a very uneasy relationship. The over-arching aim of the article is to understand how the EU relates to this paradox. We do this in three steps; first we conduct a mapping of visions for solving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict according to either egalitarian or expansionist principles, where we find one- as well as two-state solutions; second, we conduct a historical analysis on EU positions with regards to the abovementioned principles for solving the conflict, related to other powerful international actors' visions; lastly, we move to an investigation of current developments captured through recent speeches, documents and semi-structured interviews with centrally placed EU staff. Our main conclusion is that even though the EU is determined to hold on to the two state-solution, it however lacks willingness and/or power-resources to push Israel in that direction. Our interviewees seem painfully aware of the lack of viability of the two-state-solution and hence welcome criticism which could push for more egalitarian tendencies in Israel by appealing to its democratic-self-image. Here the current spread of the apartheid narrative among international organizations and an increased international human rights rhetoric emphasizing equal rights for two peoples seem to have left the EU balancing on a tight-rope where they have to choose between standing by status quo, risking supporting ultra-nationalist Israeli sovereignty-aspirations, or criticizing those, instead exposing itself to accusations of antisemitism.

For many years, international actors have viewed a two-state solution based on democratic rights for both peoples in their respective nation-state as the silver-bullet that can solve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This, however, stands in stark contrast to the ever-growing asymmetry in Israeli-Palestinian relations with creeping de facto annexation of large parts of the West Bank, Gaza under siege and a growing Israeli disinterest in negotiations where expansionist Israeli ideals tend to override democratic ones. The over-arching aim of this article is to understand how the EU relates to this paradox and what possible solutions, if any, it envisions for resolving it.

The successful Israeli conquest for sovereignty of occupied Palestinian lands has resulted in many academics, journalists as well as local actors starting to question the feasibility of the two-state solution (Yiftachel, 2005; Ron Frohlich, 2011; Lustick, 2013, 2019; Slaughter, 2013; Bashir, 2016; Bao, 2018; Munayyer, 2013, 2019; Karmi, 2020; Nimni, 2020). Instead, one-state-solutions in different guises have started to gain momentum among activists, academics and as well as politicians on the left and right of the political spectrum. However, international policymakers, such as the EU, UN and the US still cling on to the two-state narrative as the only viable alternative, despite the fact that its feasibility is rapidly diminishing. This article starts with providing historical and ideological explanations for how Israel/Palestinian relations arrived at this deadlock. Then, we explore how an important actor, the EU, deals with the fact that Israeli territorial demands impinges on the viability of a future Palestinian polity. Our results show that many EU-representatives are indeed aware of and troubled by the fact that the two-state solution is currently unviable and provide normative as well as real political explanations for why the EU seems unable to move beyond the impasse.

We start by unpacking egalitarian vs. expansionist principles with regards to solving the conflict, where (starkly different) one-state solutions can be found under both headings. Then we pay specific attention to the EU's historical and current understandings of today's paradoxical reality and relate that to broader international positions. Based on a historical analysis of EU's positions as well as recently conducted interviews with centrally placed EU staff, the analysis explores the development of EU positions with regards to current expansionist and/or egalitarian developments in Israel/Palestine. These are related to (1) views on the viability of the two-state solution and its potential alternatives; (2) the prospects of the equal rights rhetoric to counter expansionist strategies; and lastly, views on the potential of the apartheid-critique to curb Israeli sovereignty-claims on the West Bank and the possibility of that rhetoric to spread to the EU. Besides historical documents and recent speeches by EU leaders, we have conducted 10 semi-structured interviews1 (Kvale and Brinkmann, 2015) with EU officials and think tank members, placed in Brussels as well as in Israel/Palestine. We selected respondents who reflect a broad spectrum of views regarding EU policy since they are placed very differently within the EU-system. The interviews provide us with insights on current ideational developments in the EU beyond its official level. We have asked the interviewees to speak freely and reveal their own thoughts on current EU-positions. Some of the issues touched upon are considered sensitive by the EU, which is why we decided to anonymize them. By conclusion, we reflect on what it would take to rock the current status quo given the strongly path-dependent two-state discourse amid a mounting one-state reality and what the major obstacles as well as enablers may be in terms of adjusting EU norms to current facts on the ground in the region.

This article discusses visions for coexistence along two ideal types; egalitarian and expansionist ideals. The former implies an idea of a state in which all citizens have equal rights and opportunities, regardless of ethnicity and underscores principles of equality and fairness for all members therein. This form of nationalism prioritizes individual rather than group rights (Kymlicka, 2001; Walzer, 2004). The latter term refers to a state which prioritizes the rights and claims of one collective on the expense of the rights of its other groups. This principle tends to prioritize ethno-nationalism in an exclusivist form, as one collective sees its rights claims as superior/more urgent than those of others. These two principles are ideal types and may in practice be mixed or placed along a continuum of more/less pronounced ideas. In the Israeli/Palestinian context, expansionist ideals are well-captured in the literature on settler colonialism. That scholarship emphasizes Israeli settler colonial activities starting in the last two decades of the nineteenth century and its increased expansive activities during the last decades (For an overview of this literature, please see Shafir, 1996, 2016; Sabbagh-Khoury, 2022). This is a good example of how the nationalist aspirations of one group through expansionist strategies erases the legitimacy of nationalist aspirations and renders impossible the strive for national self-determination of other collectives.

Ever since Zionists started to voice claims for Palestine in the second half of the nineteenth century, a variety of ways to resolve the predicament that Palestinians and Jews claim belonging to the same territories have been forwarded. The vision of dividing the territory can be traced back to at least 1937 when the British Peel Commission published a report that recommended partition of the land into a Jewish and a Palestinian state (Morris, 2009, p. 60-61). A decade later, in 1947, the UN Special Committee on Palestine suggested a Palestine partition plan to the UN General Assembly, after which British forces withdrew from its former mandate and the State of Israel was declared. Soon thereafter, the first Arab-Israeli War broke out. After the war, Jordan and Egypt claimed control over territories in the former British mandate for Palestine. The next blow to the idea of national determination for two peoples came with the 1967 War. Then vast Jordanian-annexed territories were taken over and occupied by Israel. Israel still remains in military control over Gaza (even though its settlements there were dismantled in 2005), East Jerusalem came under Israeli formal annexation in 1980, and the West Bank remains under Israeli occupation to this day.

When the idea of dividing the land after the war in 1973 was put on the table, the PLO claimed that it was as an assault on the integrity of their homeland and an unwanted gift imposed on them (Karmi, 2020, p. 63). After the outbreak of the first intifada with its internal turmoil at the end of the 1980s, the US and the EC with its individual members were able to pressure the PLO to accept a two-state solution as the basis on which to build future peaceful relations between Israel and the PLO (Ross, 2005, p. 46-47). At the end of the 1980s a Palestinian discourse on statehood reached world-wide attention when Yasser Arafat on November 18 in 1988 declared Palestinian Independence. Arafat's declaration was famously accompanied by a call for multilateral negotiations based on principles in resolution 242, implying that PLO would grant Israel peace and security were they to turn back occupied lands to the Palestinians. That was a remarkable development in the sense that it broke with the renowned Palestinian determination not to negotiate with Israel, instead opening up for viewing it as a potential future partner for negotiations.

Among many Israelis however, the two-state solution was still viewed as a radical and repugnant (Ron Frohlich, 2011, p. 60). However, the occupation was troubling for Israel which since its creation in 1948 had prided itself with being a Jewish and democratic state guided by egalitarian norms which proved difficult when it came to ruling a population without citizenship and voting rights. Even though a few Israeli leaders had discussed the idea of Palestinian autonomy earlier, such as Menachem Begin who presented an autonomy plan in 1977, later to be included in the Framework for Peace in The Middle East, the Israeli discourse had mainly been based on unilateral views on how Palestinian autonomy could best serve Israeli interests (Singer, 2019).

Not until the 1993 Declaration of Principles and the Oslo Accords did a more genuine discourse on Palestinian autonomy rise among Israeli politicians and negotiators. Even though the declaration of principles stipulated the development of Palestinian autonomy under Israeli control, that transitory period was seen as a step toward the ultimate creation of a separate Palestinian political entity, which was somewhat of a quantum leap in terms of Israeli political positions (Singer, 2019). This propelled polarization in Israeli as well as Palestinian societies with regards to the nature of relations between the conflict parties. Israeli right-wing politicians wanted to keep the occupied territories and incorporate them into a greater Israel, and Palestinian nationalists and Islamists saw Yasser Arafat as a traitor who caved in to Israeli and US demands.

Even though the two-state discourse has been dominant since the late 1990s, the one-state idea also traces back to before the War of 1948. Ever since and until present, small activist groups within Israel have criticized the Zionist endeavor for being based on exclusionist ideals and thus colliding with norms of equality (Ram, 2011). Also many Palestinians have advocated for this idea over the years, as they have come to realize that the idea of a future two-state solution is diminishing with every year (Munayyer, 2019). However, and as eloquently summarized by Bashir (2016), there are several political constructs emerging out of this integrative idea, where liberal and binational solutions are the most common.

A liberal integrationist solution would plea for a restructuring of the state of Israel into a democratic state for all its citizens no matter their national, religious or ethnic belonging and the incorporation of the West Bank and Gaza with its present inhabitants in that democracy (Bashir, 2016, p. 562). Such a state would be based on ideas of equality and would thus not reward Jewishness over other grounds of identification (Tilley, 2010; Abunimah, 2014; Pressman, 2021). A second strand of ideas are binational and call for democratic constructions based on power-sharing solutions in which various groups within the political entity would enjoy group rights. Advocates of binationalism (Abu-Odeh, 2001; Judt, 2003; Nieli, 2009) emphasize individual as well as national rights, by promoting egalitarian politics and institutions at the same time securing national rights for both national groups. The binationalist option offers more of a middle-way in terms of principles of community (Bashir, 2016, p. 568). Another strand of ideas is confederational with limited joint institutions (Beilin, 2015; Scheindlin and Waxman, 2016; Scheindlin, 2018) such as the “land for all”-project (A Land for All, 2019) and the recent “Holy Land Confederation”-plan, drafted by Beilin and Husseini (2022) which implies a solution with two separate national entities with their own homelands under a confederated association (Bashir, 2016). In this entity Jewish Israelis would belong to and vote within their entity of the confederation, and Palestinians to the other. Borders should be open in the whole confederation so that one could travel freely across internal borders and choose where to reside whilst still paying taxes and vote within one of the entities (Serotta, 2022).

In this section we have presented proposals for how to share the land between Israelis and Palestinians along egalitarian lines. The most dominant of these egalitarian solutions is without competition the two-state solution which have garnered support from a wide range of international actors as well as resulted in large investments in the Palestinian state-building project.

During later years, Jewish far-right movements have increasingly started to challenge egalitarian principles for solving the conflict and instead advocate one-state solutions which aim for Jewish sovereignty on all Israeli lands. The below section introduces one-state-solutions based on ideals of Jewish/Israeli expansionism which currently seem to be the most pervasive in terms of reality on the ground.

Ideas expressing maximalist Jewish nationalism on current Israeli and Palestinian territories were iterated by various Zionist groups starting before the establishment of Israel. For example, Zionist revisionism as it was articulated by Zeev Jabotinsky in the 1920s and 1930s had an expansionist view of the future Jewish state. His Zionism was based on strong nationalist sentiments and emphasized a maximalist vision in which a future State of Israel should be established on both sides of the Jordan river (Sprinzak, 1993, p. 4). Updated versions of these early one-state-ideas started to gain traction when right-wing Zionism became a serious contender to Labor Zionism following the 1967 War. Then, Israeli right-wing politicians together with religious Zionists such as the group Gush Emunim (the bloc of faithful) started to work intensely to establish a strong Jewish presence in the occupied territories, with rapid settlement of a large proportion of Jews in the West Bank and Gaza (Weissbrod, 1997; Ram, 2003; Peleg, 2005, p. 105). The peace process during the 1990s with its inherent idea of a two-state solution with national rights for Palestinians was alarming to this movement as much of their ideological goals would be thwarted if the peace process was carried through.

These expansionist ideals come in different guises. There are on the one hand proponents of an “autonomy alternative” where Palestinians living in what is currently areas A and B (not Area C, which is where most settlements are) in a future Jewish state would live in a Palestinian bureaucratic autonomy but not enjoy citizen rights in Israel (Cohen, 2022, p. 141-142). This would bring Israel toward a reality of perpetual ethnic segregation where political rights of Palestinians would be minimal but where Israel would try to improve other rights for Palestinians such as raising living standards and removing the separation wall upon annexation and thus increasing freedom of movement for all.

Another alternative would be to annex all the West Bank and Gaza and offer Israeli citizenship in line with the citizenship status of current Palestinian citizens living in Israel. This would however, in order to ensure Israel's Jewish status which is an intrinsic value for the proponents of this construction, entail that the political system would be refurbished to at all times grant Jewish majorities in all political decisions of national importance (Cohen, 2022, p. 143).

A third and last right-wing alternative for a future one-state solution would be built according to current facts on the ground in Jerusalem, where a creeping, unilateral Judaization of several Palestinian parts of the city has taken place over the last decades (Cohen, 2022, p. 144; Dumper, 1997). This proposal is based on how Jerusalemite Palestinians can apply for residence status and hence also for citizenship and are then allowed to vote. From an outsider perspective this could be considered a risky strategy since it is unclear what would happen if all West Bank Palestinians would apply for and get citizenship status (even though a majority of Jerusalemite Palestinians choose not to do so). Then a large part of the population would garner democratic rights which might create problematic situations for a polity which is built on interests of the Jewish population (Cohen, 2022, p. 144). Lastly, some right-wingers propagate for offering Jordanian citizenship and voting-rights to Palestinians, hence reviving the old slogan “Jordan is Palestine”, which was prevalent among right-wingers in the 1980s (Lustick, 2022, p. 10). Thus, Palestinians would continue to live under Israeli control, yet their rights and duties would be with another administrative unit.

These ideas have in common that they reject any legitimacy of Palestinian national claims, and based on this, it follows logically that the Jews are the only people with historical right to the occupied territories. In that sense, occupation would by all means be legal and a one-state solution is considered the only legitimate way to provide a state for all people with Israeli citizenship (Cohen, 2022, p. 147). These right-wing ideas share the striving toward a state with Israeli superiority over Palestinians (Lustick, 2022). These ideational constructs are not based on liberal democratic principles of equal rights for all, and yet they seem to be guiding the everyday development of life for West Bank Palestinians and settlers who live side by side, yet in vastly different realities.

Under the first years of Oslo the ultra-nationalists, even though very loud and critical against Oslo were not that dominant in Israeli politics, yet over the years this faction has grown substantially. That, together with the enlargement project of settlements and changing demographics that have been going on for decades have increased the number of right-wing proponents of Jewish expansionist one-state visions (Del Sarto, 2017). These views have over the years made it into mainstream politics which was notable in Benjamin Netanyahu's speech prior to the 2015 elections when he stated that no Palestinian state would be established on his watch, followed by his annexation announcement released in 2019 (Cohen, 2022, p. 134-135).

The one-state solutions as iterated by the Israeli far right and the settler movement introduced above may indeed seem like ultra-radical ideas which may not appeal to the Israeli mainstream. However, the current state-of-affairs in Israel-Palestine with an unrealized two-state solution together with expanding Jewish sovereignty on occupied territories continues, the Israeli right-wing solutions as presented above may not be far-fetched (Jamal, 2022; Lustick, 2022). Even though the current situation may be seen (or hoped for) by many as an interregnum which is to eventually end in a two-state solution, current facts on the ground where Israel increases its grip over what could be a potential future Palestinian state rather than loosening it at the same time that the Palestinian state-building project becomes increasingly fragile, we view the emerging one-state reality as part of an expansionist strategy which hinders any serious attempt at a two-state solution.

Even though a majority of Israelis and Palestinians were positive to a two-state solution at the outset of the Oslo-process in the early 1990s (Ma'oz, 2004, p. 135; Shamir and Shikaki, 2002), the developments since have led to Israelis and Palestinians alike losing faith in the two-state solution. Extremist violence in the 1990s, the second intifada, the Israeli construction of the wall, internal strife between Fatah and Hamas, continued expansion of Israeli settlements, Israeli harsh military rule over occupied lands together with Palestinian waves of violence against civilians have created a situation in deadlock. In such a political reality, the political entity with most power-resources, in this case Israel, has remained with the upper hand which have increased power asymmetries resulting in today's seemingly perpetual one-state-reality (Jamal, 2022; Lustick, 2022). This reality points to a situation in which it will be near-to impossible to create a Palestinian political entity on the sliced-up lands which are left in the wake of the ongoing expansion of settlements and hardened siege (Bao, 2018, p. 331; Roy, 2004, p. 367-370). Many commentators thus see the two-state solution, whether it is normatively preferable or not, as having failed in terms of future viability (Lustick, 2019; Munayyer, 2019; Karmi, 2020).

However, the one-state reality creates concerns for Israel, since the state wishes to be portrayed as a vibrant democracy. If Israeli sovereignty conquests for all occupied territories persist, that would disqualify Israel from being a Jewish and democratic state, since its main population in such a reality would consist of non-Jews under Jewish minority rule (Abulof, 2014; Lustick, 2019, p. 123). Furthermore, the Palestinian state-building project as laid out in the Oslo process has furthermore created an apparatus with strong path-dependency with regards to the two-state paradigm, no matter how illusive it may appear to Palestinians during present conditions. It would be very hard to roll back the massive Israeli infrastructure built in the West Bank during the last decades and it may prove equally difficult to undo the Palestinian state-building project (Ron Frohlich, 2011, p. 64). For many years now, massive resources, not least from the EU, have been spent on building a Palestinian Authority, creating new institutions with staff that now have personal incentives to keep those in place and hence continue to advocate for an independent state where those newly built institutions would remain and could constitute the nascent state's backbone.

This section has described an emerging impasse where internal forces, Israeli as well as Palestinian, both treat the discourse on partition as the solution creating least resistance internationally, which in turn aides the continuation of the quite unrealistic vision of a two-state future (Ron Frohlich, 2011; Telhami, 2011). At the same time, commentators have underlined the fragility and weakness of current Palestinian institutions which, if they were to collapse, would confront internal and third parties to the conflict with an entirely different reality. This current collusion between egalitarian and expansionist visions recalls Antonio Gramsci's understanding of hegemonic crisis defined as “the old is dying and the new cannot be born” (Gramsci, 1971, p. 271). In the remainder of this article, we will analyze how EU, related to broader discourses in the international community, has confronted this conundrum.

For over half a century, the EU has been one of the leading international actors in promoting a diplomatic solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The process of creating the parameters for the two-state solution has been incremental, beginning in the early 1970s with what was then called the European Community's (EC) first statement on the conflict (Persson, 2020, p. 17). In that declaration, the EC foreign ministers declared that it was of great importance for Europe to establish a just peace in the Middle East. The declaration expressed approval of UN Security Council resolution 242, which constituted the basis of a settlement, and stressed the need to put it into effect in all its parts. The term “Palestinian” was not used in the declaration. Instead, the Palestinians were referred to only as “refugees”, which was also the case in UN Security Council resolution 242 (Bulletin of the EC, 6-1971, p. 31). The first shift in the EC's conception of the conflict came after the 1973 war, when the term Palestinians entered EU discourse. The EC recognized “that in the establishment of a just and lasting peace account must be taken of the legitimate rights of the Palestinians” (Bulletin of the EC, 10-1973, p. 106). The rest of the 1970s saw a long list of EC declarations that were often perceived as pro-Palestinian/pro-Arab. From advocating the legitimate rights of the Palestinians after the war in 1973, the EC went on to mention legal rights of the Palestinians in 1975, that the Palestinians were a people with the need for a homeland in 1977, that Israeli settlements were in violation of international law in 1979, to advocating for Palestinian self-determination and talks with the PLO in the EC's Venice Declaration of 1980 (Persson, 2020, p. 158-59). It is thus quite clear that the EU has been engaged in advocating for Palestinian rights for several decades.

During the 1980s, EC diplomacy was very successful in advocating what would later become the Oslo peace process's two guiding principles: mutual recognition and land for peace. When the Declaration of Principles (DoP) was finally signed in 1993, it looked much closer to the Venice Declaration than anything the US, the Israelis or the Palestinians had previously outlined (Persson, 2020, p. 41). Other actors involved in the conflict, most notably the US, often followed the EU's example and adopted policies that the EU had been the first to outline. This development pointed to the EU's important normative role in the conflict, what has been referred to as “Normative power Europe” (See, for example Manners, 2002; Pardo, 2015; Persson, 2017). By the 1990s, the EU's positions had crystallized into strong support for a negotiated two-state solution based on democratic rights for both peoples in their respective nation-state, which the EU tried to achieve through various instruments. It put down major investments in Palestinian state-building and strengthened bonds with Israel and the PA through the European Neighborhood Policy (Tocci, 2009, p. 387). However, the EU has often been criticized for being more of a payer than a real player vis-à-vis Israel/Palestine since its economic and technical instruments have not been powerful enough to push Israel to roll back its occupation (Pace, 2016; Bicchi, 2018; Müller, 2019). While the EU and its Member States often played significant roles before and after agreements were signed, it has only had marginal impact, if any, in the most important peace negotiations during the past four decades: the 1978 Camp David Accords, the 1979 Israel-Egypt Treaty, the 1993 DOP, the 1994 Israel-Jordan Treaty, the 1995 Oslo II Accords, the 2000 Camp David Summit, the 2003 Road map for peace and the 2007 Annapolis conference. The same pattern repeated itself throughout the Obama and Trump presidencies (Persson, 2020, p. 69).

Nevertheless, the EU was one of the most ardent supporters of the Oslo peace process and contributed around 50% of the total aid to the Palestinians during the peace process of the 90s and 2000s (Persson, 2020, p. 95). During the first years of Oslo, the EU talked in general terms about Palestinian self-determination in terms of autonomy, but this changed in 1997 when the European Council for the first time called on “Israel to recognize the right of the Palestinians to exercise self-determination, without excluding the option of a State” (Bulletin of the EU, 6-1997, p. 22). That somewhat ambiguous call for a Palestinian state was repeated in the Cardiff European Council of 1998, but it was not until the Berlin Declaration of 1999 that the EU explicitly endorsed the idea of a Palestinian state:

The European Union reaffirms the continuing and un-qualified Palestinian right to self-determination, including the option of a State, and looks forward to the early fulfilment of this right (Bulletin of the EU, 3-1999, p. 21–2).

In the Seville Declaration from 2002, the EU for the first time declared that the two-state solution should be based on the 1967 borders with minor adjustments agreed by the parties if necessary. This was also the first time that the EU addressed the final status issues of Jerusalem and refugees within the framework of a two-state solution, advocating fair and agreed solutions to both issues (Bulletin of the EU, 6-2002), p. 22). In 2009, the European Council for the first time called for Jerusalem to be the capital of a future Palestinian state (Council of the European Union, 2009).

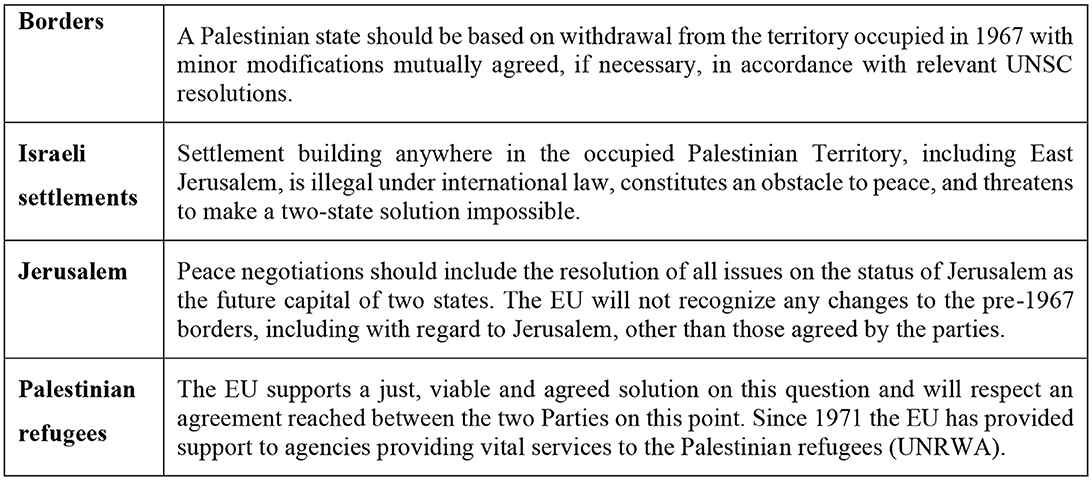

Despite numerous promises to recognize a Palestinian state, the EU and many of its Member States did quite the opposite when the Palestinian bid for statehood was submitted to the UN's Security Council in 2011. The failed UN bid took much of the momentum out of the Palestinian state-building process. Afterwards, much of the EU's work vis-à-vis the conflict shifted from focusing on Palestinian state-building to differentiation—the policy of excluding settlement-linked entities and activities from the internationally-recognized Israel in the EU's relations with Israel, which was a way of keeping up relations with Israel while at the same time criticizing its construction of settlements on occupied lands (Lovatt, 2016). This became a major issue of contention in the middle of the 2010s, but so far it has changed very little on the ground, since Israel has continued on the path of settlement expansion. In 2014, Sweden became the first EU member state to recognize Palestine (several member states had already done so before they joined the EU). Many member states promised to follow, but in the end no one did, which again points to the inability of the EU and its members to live up to its promises with regards to a future two-state solution. Sweden's example as well as world-wide efforts at recognizing a Palestinian state at the UN can be understood in two ways. One the one hand as lending legitimacy to Palestinian claims to national self-determination within the remits of their own future state. On the other as entrenching the path-dependence of a two-state solution, hence obscuring the search for alternative solutions. Currently, the EU differentiation strategy, together with Sweden's recognition of Palestine and the 2016 UN Security Council resolution 2,334 (which was strongly supported by the three EU member states in the UN Security Council at the time: France, United Kingdom and Spain) were probably the last international efforts to save the two-state solution, at least in the form that the EU imagines it. The below figure summarizes EU's position with regards to a two-state solution, emphasizing equal rights and mutuality, together with the dismantling of settlements, which is anathema to the current one-state-reality (Figure 1).

Figure 1. EU current positions on the two-state solution's parameters (EEAS MEPP, 2019).

Even through the two-state solution seems increasingly unviable, the EU has insisted on propagating it. This is partly based on normative claims based on that Israeli as and Palestinians in the long run have the right to sovereign states built on egalitarian principles, but also, according to some, a result of the EU wanting to keep stability in its peripheral neighborhood. The lack of international consensus on alternatives to a two-state-solution is also seen as a factor which strengthens its prevalence in EU rhetoric (Del Sarto, 2019, p. 391; Tocci, 2009, p. 397). The below discussion on current EU positions as expressed in recent statements by EU officials we have interviewed also touch on the distinction between power-politics/stability vs. promoting liberal norms of equality.

Immediately after Israel had occupied large land areas in the war of 1967, the idea that Israel should return these arose, most notably through the UN Security Council resolution 242 (which was built on the principle of land in exchange for peace) which was adopted unanimously by the Security Council. Later UN resolutions have iterated that construction of settlements on Palestinian lands are understood as violating international law (Susser, 2018). Thus, the UN and other strong international actors have later tried to push for the end of settlements which are seen as “a flagrant violation under international law and a major obstacle to the achievement of the two-State solution...” (UNSC res 2334, 2016). The latter resolution was seen as problematic by many US officials since it was strong in its criticism of Israeli settlements. The US did not use its veto-power to block the resolution but chose to abstain from voting which resulted in a wave of criticism against the Obama's administration's policy from pro-Israeli groups in the US (Daugirdas and Mortenson, 2017). As mentioned previously, this chimes well with the measures the EU has taken in response to Israeli settlement expansion, including labeling settlement products as such and discouraging businesses from operating in settlements. In this vein, the EU has continuously called on Israel to freeze settlement construction and to take steps to dismantle existing settlements in the occupied territories. It has furthermore been consistent in its condemnation with regards to Israel's demolition of Palestinian homes and infrastructure in the occupied territories, as well as its policy of “administrative detention”, which allows Israeli authorities to detain Palestinians without charge or trial for extended periods of time (EEAS, 2021).

Since the two-state solution has been increasingly hard to realize despite the attempts at Palestinian state-building following the Oslo Accords, various state-actors have over the years advocated for diplomatic recognition of the state of Palestine to even out the strong power imbalance in Israel's favor. Even though many states, such as in the Swedish example above, have granted such symbolic recognition of Palestine, it remains mainly a declaratory move, since the three Western states in the Security Council, most notably the US, as well as the EU, have abstained from doing so. The Palestinian leadership have repeatedly sent delegations around the world to encourage diplomatic recognition of Palestine. Several BRIC-states did so already in the 1980s, and over the years many other states have followed. Currently 138 of UN's 193 member states have granted Palestine diplomatic recognition (Globalsecurity.org, 2022; World Population Review, 2022). Since not being recognized as a state, Palestine cannot be a member of the UN, but has had the status of a non-member observer state of the General Assembly since 2012. In line with these symbolic gestures, important actors such as the UN, the EU, the Quartet and individual states have tried to uphold the international consensus for a two-state solution negotiated by the parties, in spite of facts on the ground increasingly tilting in Israel's favor with an ever-diminishing territorial basis for a future Palestinian state. A strong exception in the US case was the Trump presidency, during which the US administration insisted on making unilateral actions in Israel's favor, moving key tectonic plates inherent in the international consensus on the two-state solution. For example, Trump in his “Deal of the Century” did mention the future creation of a Palestinian state, but also envisioned future annexation of parts of the West Bank and extending Israeli sovereignty to settlements in areas occupied by Israeli forces in the 1967 war (very much in line with Israeli current expansionist strategies). The Trump plan also stipulated that Israel should be responsible for security in the Jordan Valley for the foreseeable future, which could be scaled back as the Palestinian state developed (Trump White House Archives, 2020). This plan was heavily criticized by Palestinians and internationals alike as it implied a shift toward Israeli expansionism in the conflict (Arieli, 2020). The new US administration has however returned to some of its previous positions, with both Antony Blinken and Joe Biden continuously reaffirming their strong rhetorical support for a negotiated two-state solution.

While the Biden administration has kept most of Trump's policies vis-à-vis the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in place, his administration has come to develop a standard phrase which top officials increasingly use regarding the Israel-Palestinian conflict, along the lines that Israelis and Palestinians should enjoy “equal measures of freedom, security, prosperity, and democracy” (See, for example Blinken, 2021), in line with the EU rhetoric mentioned above. In the US, the idea of ending occupation has never resonated strongly with the broader public since occupation has had a quite peaceful connotation stemming from postwar occupations of Germany and Japan. However, the idea of equal rights for all citizens may be more appealing to a US audience (Lustick, 2019, p. 145). Some commentators assert that this is an important shift in US discourse vis-à-vis Israelis and Palestinians (Lustick, 2019; Serhan, 2021). However, it should be noted that the new US emphasis on human rights and equality often appear together with the two-state rhetoric (see for example statements from US State Department, 2021, 2022). The US equal rights speech may hence only be of declaratory status, signaling important norms to the international community while at the same time silently accepting that Israel's grip of the occupied territories hardens.

No matter the seemingly relentless international support for a two-state solution, the conflict's inherent and increasing power asymmetry has garnered strong criticism from parts of the international community. For a long time, a large number of academics and critics have pointed to similarities between the fate of the Palestinians under occupation and the situation of the black population in South Africa under the apartheid regime (Falah, 2005; Yiftachel, 2005; Tilley, 2010). Lately, this rhetoric has been picked up by influential local and international human rights organizations (See for example reports by B'Tselem, 2021; Human Rights Watch, 2021; Amnesty International, 2022) who are now increasingly referring to the Palestinian situation under occupation as apartheid (Waxman, 2022). The heightened intensity of international criticism together with raised demands for equality for all may contribute to a stronger focus on egalitarian principles for Israelis and Palestinians alike. They can also exercise important leverage and provide substance for criticism for other international actors. However, thus far, neither the US or the EU has been willing to embrace the apartheid-narrative for various reasons, further discussed below. However, in 2022, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territory occupied since 1967, Michael Lynk, commented on a recent report conducted by the UN Human Rights Council where he mentioned that Israel's increasing grip of occupied lands had shifted from occupation into something more ominous and noted that entrenched rule in the occupied Palestinian territory satisfied the evidentiary standard for apartheid. He concluded that “With the eyes of the international community wide open, Israel had imposed upon Palestine an apartheid reality in a post-apartheid world”. Hence, even though the Security Council, the EU and others have refrained from using the apartheid rhetoric, it seems to be spreading beyond NGOs and making its way also into powerful institutions (OHCHR, 2022).

It is important to note that human rights organizations like Amnesty International, even though they are strong in their criticism toward the current status quo, are very careful about not suggesting political solutions. On the question about what kind of political entity they envision for Israel and Palestine, they claim: “This is a political issue and, as such, Amnesty takes no position on this, or on a two-state solution, confederation, or other possible arrangements” (Amnesty International, 2022). However, if egalitarian ideas and criticism of the one-state-reality are proposed together with the two-state solution, there would still be no paradigmatic shift in sight with regards to moving away from the two-state vision.

Despite the EU and the US's ardent support for egalitarian solutions, they have never officially lent support to a one-state solution. Proponents of this idea in the international sphere have instead been found among academics, activists and journalists who have imagined an egalitarian future for the two peoples that breaks with a two-state vision. These have often been Israeli, Palestinian and/or international writers and activists (Tilley, 2010). Early on, the Palestinian academic Edward Sa'id was one such proponent. He was a critic of the Oslo Accords from the outset and claimed that it would be destructive to Palestinians. He saw the Oslo Accords as only benefitting Palestinian elites and claimed that the vast majority of Palestinians would never gain from such an agreement (Bao, 2018, p. 330; Said, 2000). Several others voiced similar ideas early on and wrote articles and petitions directed toward an international audience in newspapers like the Guardian (Milne, 2004; Shlaim, 2004), and in journals like The New York Review of Books (Judt, 2003). It stands clear that even though the current one-state-reality has engendered criticism from a broad range of international actors, very few influential actors in the international sphere promote egalitarian one-state solutions. Expansionist one-state-ideals are equally scarce in the international sphere, and are advocated chiefly by ultra-nationalistic lobby groups, mainly in the US (The Times of Israel, 2019).

This section introduces EU officials' views on how to handle the fact that Israeli ongoing expansionist strategies are making future egalitarian solutions impossible. We first map their and current EU views on the contradictions between egalitarian EU-norms and current Israeli policy, then turn to certain strategies that the EU uses to push Israel as well as reasons for why these are not effective. Lastly, we move to a discussion on the emerging Apartheid-rhetoric among international actors which indeed may be a powerful tool for pushing Israel, yet also might expose the Union to criticism for being antisemitic.

Already in 2018, Federica Mogherini, then the EU's High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, described the situation in Israel-Palestine as a “one-state reality, with unequal rights for the two peoples, perpetual occupation and conflict” (Mogherini, 2018). Moreover, in 2019 more than 35 highly ranked former or current ministers signed a letter on continuous support for a just two-state solution, asserting that “Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories are sliding into a one-state reality of unequal rights. This cannot continue” (Alexander et al., 2019).

Our interviews confirm the view that the two-state solution as the EU has imagined it for two decades “is dying in front of our eyes”, as one EU official in Jerusalem put it (Interview, August 23, 2022). According to another interviewee, the two-state solution is like a “a silver-spun cloud, slowly drifting away” (Interview, November 24, 2022). Another one mentions that s/he has “a very hard time seeing it being realized” (Interview, December 15, 2022). At the same time, all the EU officials we interviewed are even more pessimistic regarding an egalitarian future one-state solution. One interviewee, an EU think tank leader, pinpoints the current deadlock by saying that:

“the EU stands nowhere at the moment with no serious debate on either the two-state or one-state solutions with fewer and fewer EU officials believing substantively in the two-state solution” (Interview, August 29, 2022).

Moreover, one of the EU officials in Jerusalem comments that there is “low appetite in the EU to advocate for a one-state solution as long as the parties themselves (the government of Israel, the Palestinian Authority and even Hamas) do not favor such a solution” (Interview, August 23, 2022). Several of our interviewees concur that the EU could change it position, but then only if the parties would come to consensus or another solution, be it two states, three or even five (interviews November 28 and December 9, 2022).

The general view among our interviewees is that as long as the EU-supported Palestinian Authority officially clings to the two-state solution, it would be hard for the EU to advocate for another solution. But the rhetorical support for the Palestinians comes with a price, according to an EU official in Brussels:

Sometimes I believe that we do the Palestinians an enormous disfavor when we speak about Palestinian rights without being ready to support them. We do nothing to support their rights and thereby we undermine their rights (Interview, November 24, 2022).

All but one of the EU officials we interviewed saw little space between a two-state and one-state solution. “The EU will probably be the last [actor] to change our language”, said one of the EU officials (Interview, December 15, 2022). The one with a dissenting view said that s/he is struggling between “what is right or wrong according to international law vs. what is politically possible” (Interview EU official in Brussels, November 24, 2022). A possible way forward for the EU is the initiative currently envisioned by its Special Representative for the Middle East Peace Process, Sven Koopmans. That plan builds upon and broadens both the Arab Peace Initiative (API) from 2002 and the Abraham Accords from 2020 by engaging regional actors such as the Arab Quartet and work for normalized relations with Israel and more Arab countries in the spirit of the Abraham Accords. Koopmans is sometimes referred to as “a wild visioner” by other EU officials (Interview, November 24, 2022). In the words of an EU official in Jerusalem, Koopmans' plan is about the EU and other regional actors building a circle of incentives around the parties until they are squeezed to agree on a solution (Interview, December 9, 2022). No matter how wild the visions might be, they are indeed still along the lines of an egalitarian two-state solution.

Another challenge to the future of the two-state solution is the increasing fragility of the PA. The PA's institutions, deemed ready for statehood a decade ago by EU, the UN, the IBRD, the IMF and other international actors, are now very weak with a dissolved parliament and no clear order of succession after Abbas. “A collapse of the PA may change the map”, says one of the EU officials in Jerusalem (Interview, August 23, 2022), which may also affect how the EU views the feasibility of a two-state solution. Several of the officials we interviewed are worried about the frailty of the PA yet says that the EU does not have any contingency plans for what may happen if it collapses. One EU official suggests that the EU may have to leave the region and only keep European consulates open if the PA collapses and massive violence erupts (Interview, December 15, 2022). Another one says that we don't have a contingency plan since “we're not a forecasting institute” (Interview EU, December 6, 2022). A third says that “We have no contingency plans. We just hope it will not happen” (Interview, December 9, 2022).

Moreover, many in the region are awaiting the fate of the PA after the 87-year old PA President Mahmoud Abbas eventually leaves office. However, according to an EU official in Jerusalem, Abbas often jokingly comments that his father lived to the age of 112 and that they may have to be stuck with him for another 25 years (Interview, August 19, 2022).

This section has showed the strong path-dependence for the two-state solution in the EU, even though many interviewees as well as EU leaders realize that it is unrealistic during present conditions. Even when faced with an increasingly expansionist Israel, the EU doesn't have any viable alternatives to that scenario and is now occupied with designing a new peace initiative, the API 2.0, which also has a two-state solution at its core. As one of our interviewees puts it: “The EU has no stick to use outside Europe […]. It's unrealistic that the EU can put any real pressure on Israel” (Interview, December 9, 2022).

Mogherini's successor Borrell (2021) almost echoed the Biden administration's phrase on equal measures when he expressed that “both Palestinians and Israelis alike deserve to live in safety and security, enjoying equal rights, fundamental freedoms and democracy”. On the one hand the evolving EU-language on equal rights may merely be empty words, especially since the two-state solution is becoming more and more elusive, according to one EU official (Interview, August 23, 2022). Every time the equal measures-phrase is used and “with every new iteration backed by no action, it becomes clear how empty it is”, says a think-tank leader (Interview, August 29, 2022).

On the other hand, the equal measures-phrase can also be understood as “a shift away from an immediate focus on the two-state solution toward a more fundamental norm that ultimately there needs to be equality in either two states or one state—any solution there is, there must be equality” (Interview, August 29, 2022). Here it seems that the focus on egalitarian principles is the main priority, downplaying practical solutions for solving the conflict. According to this reasoning, “the key is to achieve equal rights whether in the form of a one-state or two-state solution” (Interview, December 7, 2022).

Most of our interviewees are positive toward the narrative on equal rights, but the answers are ambiguous regarding how it relates to the two-state solution. One EU official (Interview, November 28, 2022) said that the narrative on equal rights should be understood within the framework of a two-state solution. However, another interviewee questions whether the narrative on equal rights is stronger or weaker than the two-state solution, suggesting that they may or may not go hand in hand (Interview, November 24, 2022) A third EU official thinks it is a useful rhetorical tool which appeals to Israel's self-image as a liberal democracy (Interview, December 6, 2022). In the same vein, another EU official claims that the new emphasis on equal rights is a:

“not-too-subtle hint to particularly the Israeli constituencies that this is what will be the reality if there's no actual push for a peace-process or a two-state solution […] it's an implicit nod toward getting ready for what needs to be faced if this continues” (Interview, December 9, 2022).

Interpreted in this way, the equal-rights language sends a clear symbolic message conveying that the current status quo in the conflict is unacceptable. Our interviewees see the rhetoric as coming with a tacit threat, to make Israelis aware of the problematic demographic/democratic situation that arises with continued expansion, then facing a one-state-solution where one seriously has to confront the issue of how to handle of Palestinian rights in occupied areas, at a time where the whole world is watching. One of our interviewees comments:

“It is a strategic decision to hold Israel up to democratic standards since it prides itself with being a vibrant democracy. Then it is smart to advance narratives which appeal to that self-image.” (Interview, December 6, 2022).

Throughout 2021 and most of 2022, neither the Biden administration nor the EU seemed able or willing to back up the equal measures-phrase with any significant content. Furthermore, in late 2022, the Biden administration called on Israel to crack down equally on Jewish and Palestinian extremism in a sharply worded statement (Lazaroff, 2022). However, despite its apparent popularity and harsher wordings, the equal measures-phrase and the broader narrative on equal rights seem thus far to have had very little impact on Israeli expansionist policies and the reality on the ground. As pointed out by Spitka (2023) there is a remarkable gap between the equal rights rhetoric and protection of Palestinian human rights and the absence of such protection in practice. It seems that protection of Palestinian rights mainly has translated into human rights assistance and the monitoring of abuses and ad hoc-projects rather than offering any substantive support to Palestinians in an increasingly dire human rights predicament.

The recent labeling of Israeli occupation as apartheid by human rights organizations is an extremely sensitive issue in contemporary EU-Israeli-Palestinian relations. While a few current and former EU foreign ministers have used the term, most notably Jean Asselborn of Luxembourg, it is still far from being mainstreamed as a term among top European officials, at least publicly (Whitson, 2022). In early 2023, Josep Borell, speaking on behalf of the European Commission, came out strongly against the apartheid narrative when he told the European Parliament that “the Commission considers that it is not appropriate to use the term apartheid in connection with the State of Israel” (Borell, 2023). All our interviewees agree on the unbalanced power-relations in the region, but also that “it is too politically sensitive to use the apartheid-language” (Interview, December 9, 2022). In a sense, “the discourse today is polarizing between two A-words: apartheid vs. antisemitism” (Interview, August 29). While many academics, activists and legal organizations have increasingly forwarded the apartheid narrative, the political establishments in Europe have largely embraced the antisemitism narrative by adopting the new IHRA definition of antisemitism according to which criticism against Israel is often labeled as antisemitism. Several of our interviewees claim that the EU is weary of using the apartheid label due to Europe's WWII legacy, but several also argue that real-political motives are at play:

“the fact that Israel is a very important security provider and ally in the region, I think that is another reason why they don't want to antagonize it” (Interview, December 9, 2022).

When asked about the apartheid-label, most of our interviewees are uncomfortable with using the term. Neither do they believe that the EU is about to start using it related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in any foreseeable future. One of the EU officials in Brussels says that while there is “gross injustice going on […] we prefer not to enter into that discussion […] we are encouraged by NGOs, but we don't” (Interview, November 28, 2022). Another EU-official holds that it would be unfruitful for the EU's relations with Israel to use the term apartheid, that the EU may lose leverage with Israel, and could be accused of antisemitism if using it (Interview, December 6, 2022). On the other hand, one EU official in Jerusalem states “we struggle with defining the situation. If it is not apartheid, then what is it?” (Interview, August 23, 2022). Another official in Brussels says “while the EU is not ready to agree on the apartheid narrative, many EU officials recognize many features of apartheid on the ground” (Interview, November 24, 2022). An EU think tank leader takes this argument to the fullest, saying that “the EU won't use the word apartheid, but it would say that Israel risks entrenching a one-state reality with perpetual occupation and unequal rights. That is the definition of apartheid” (Interview, December 7, 2022).

Our interviews reveal a paradox in that EU official institutions as well as the officials we interviewed claim to be against the EU adopting the apartheid narrative while at the same time welcoming the human rights organizations' reports that accuse Israel of apartheid. This paradox is unwrapped by an EU official in Tel Aviv:

“We are very careful, we are reading these reports, we are taking note of it, we value the work of these organizations, such as Amnesty International. At the same time, we are not using the label apartheid… at the moment this is not where we want to go.” (Interview, December 6, 2022)

One of the officials in Brussels says that it is important to keep in mind that:

“the apartheid narrative is not a trajectory toward something, more a description of a permanent situation, but not something that the EU is ready to agree upon or move toward” (Interview, November 24, 2022).

But the human rights organizations' apartheid rhetoric seems to have raised awareness of the human rights violations on the West Bank. This “draws attention to the alarming situation and affects Europeans” (Interview, December 9, 2022).

In other words, the apartheid rhetoric may serve to raise awareness among Europeans of the human rights situation for Palestinians. Consequently, there is a clear linkage between the rise of the apartheid narrative and a shift toward a rights-based discourse emphasizing equal rights in the realization that the current conditions on the ground are unacceptable (Huber, 2021). If this trend continues, “HR-issues will come even more to the fore—pushed by events on the ground”, says one of the officials in Brussels (Interview, December 9, 2022).

This article has showcased the growing gap between the two-state ideal which still seems to be the favored solution among international actors and a situation on the ground in which such a scenario is becoming increasingly less viable, now resembling the one-state reality (2019). Even though the international community is consistent in its criticism of Israeli unilateralism and settlement expansion, it seems hard to rock the two-state solution's long trajectory as the only viable solution to the conflict among its third parties.

The EU has commenced on its insistence on the two-state-solution, even though Mogherini already in 2018 claimed that the reality on the ground resembles an inequal one-state solution. Lately, a slight shift in EU rhetoric toward an emphasis on “equal rights” following the example of the US has however been emerging. Even at the time of writing this piece, EU's “wildest” future vision for Palestine—the API 2.0—is built on the two-state solution. However, our 10 interviewees seem painfully aware of the growing distance of the two-state idea and increasing Israeli expansion on the ground. Beside the emerging discourse on equal rights, security and democracy, current developments in the EU do not reveal any dramatic shifts in EU positions which would place the organization closer to propagating other solutions. Moreover, our EU informants emphasize that the EU will not work for a one-state-solution before both parties agree that such an idea is desirable, which today seems far-reached. Furthermore, the EU is far from adopting the apartheid-narrative even though most of our interviewees seem to welcome it based on the fact that it raises awareness of the human rights issues that Palestinians are facing. Hence, no matter the skepticism vis-à-vis the viability of the two-state solution expressed by our interviewees, the EU still seems a far cry from giving up on the idea of a two-state solution. In general, we discern a lot of agreement on important points among all our interviewees, however with a tendency that the officials working in the region tend to be more outspoken in their critique of Israel than the ones in Brussels, which has previously been pointed out by Bicchi (2016).

If we look at push factors which could change the current one-state-reality, vocal international critics such as Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and local ones such as B'tselem have increasingly come to talk about an Apartheid situation on the West Bank, heavily criticizing Israel's politics vis-a-vis the Palestinians in an attempt to shift international discourse and put increasing political pressure on Israel. The emerging equal-rights rhetoric in the US and EU may also serve as persuasive devices, encouraging moderate factions in Israel to promote egalitarian democratic ideals and disengage from sovereignty-expansion on the West Bank. Another factor which may rock status quo is the decreasing viability of the PA which with a possible collapse would spur reconsiderations of the actors in the region regarding if or how they can be parties in a future solution to the conflict.

Among the pull-factors for a continued one-state-reality, is the path-dependence of Palestinian state-building by the PA and the ardent support by the EU and other international actors (Del Sarto, 2019). This contributes to uphold the ideational grip of the two-state-solution, even though it is losing touch with current reality on the ground. At the same time, Israel's exclusionist trajectory, blatantly apparent with the incoming government, with less focus on human rights and freedom of expression does not give much hope for more egalitarian solutions. This should rather be seen as upholding status quo and increasing expansionist tendencies with regards to Israeli rule over the West Bank and Gaza. Israeli right-wing actors also frequently accuse organizations who use apartheid-criticism as well as critics of Israel's politics in general of antisemitism, which is something that especially the EU fears being associated with, making the EU less inclined to join in such critique, instead insisting on more moderate statements regarding equal rights for both peoples.

It is also clear that the EU is careful not to taint its relations with Israel by being too critical of what is seen as a strategic ally in the region. It remains to be seen if the increasingly violent situation in Israel/Palestine will push the EU to put more power behind its words which may, if picked up by other influential actors, push toward more viable ways to adjust to the ongoing reality in Israel and Palestine. That, however, implies that external actors like the UN, the US and the EU embarks on a search for genuine alternatives to current Israeli expansionist policies and open up for shifted power-relations in the region. Those actors would then have to put power behind their hitherto mainly declaratory criticism of the current situation and take a bold a leap of faith toward a more egalitarian future for Israelis and Palestinians alike.

Even tough walking a tightrope risking criticism for either neglecting Palestinian human rights concerns or being antisemitic, it seems like the EU is currently implementing a policy in line with the law of least resistance. It rhetorically clings to principles of international law supporting the right of self-determination for both Israelis and Palestinians. However, that seems to favor Israel's concerns regarding the fear of not having the internationally recognized borders of the Israeli state as well as the legitimacy of Israeli self-determination, whereas in practice it denies Palestinians' demands for self-determination and seemingly perpetuates occupation.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The research conducted for this article is in accordance with the Swedish Ethics Review Act. The interviewees provided consent to participate in the study.

The authors contributed equally to the writing of this article.

This research was funded by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, through the project ‘Pushing the Boundaries of Peace Research: Reconceptualizing and Measuring Agonistic Peace', Grant number RIK18-1441.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^Of our 10 interviewees, three were with EU officials in Brussels, three were at the EU office dealing with the OPT in Jerusalem, one was at the EU delegation in Tel Aviv, one was with an EU Member State official in Jerusalem and the remaining two were with think-tank representatives.

A Land for All (2019). Available online at: https://www.alandforall.org/english/?d=ltr (Accessed May 23, 2023).

Abulof, U. (2014). Deep securitization and Israel's “demographic demon.” Int. Polit. Sociol. 8, 396–415. doi: 10.1111/ips.12070

Abu-Odeh, L. (2001). The Case for Binationalism. Georgetown Law Faculty Publications and Other Works. p. 1637. Available online at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1637 (accessed May 23, 2023).

Alexander, D. (2019). Europe Must Stand by the Two-State Solution for Israel and Palestine. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/apr/14/europe-must-stand-by-the-two-state-solution-for-israel-and-palestine (accessed May 23, 2023).

Amnesty International (2022). Israel's Apartheid Against Palestinians: Cruel System of Domination and Crime Against Humanity. Amnesty International. Available online at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2022/02/qa-israels-apartheid-against-palestinians-cruel-system-of-domination-and-crime-against-humanity/ (accessed November 17, 2022).

Arieli, S. (2020). Trump plan sets the conflict back 100 years. Palestine-Israel J. Polit. Econ. Cult. 25. Available online at: https://pij.org/articles/1998/trump-plan-sets-the-conflict-back-100-years (accessed May 23, 2023).

Bao, H.-P. (2018). The one-state solution: an alternative approach to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict? Asian J. Middle East. Islam. Stud. 12, 328–341. doi: 10.1080/25765949.2018.1534407

Bashir, B. (2016). The strengths and weaknesses of integrative solutions for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Middle East J. 70, 560–578. doi: 10.3751/70.4.13

Beilin, Y. (2015). Opinion | Confederation Is the Key to Mideast Peace. The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/15/opinion/yossi-beilin-a-confederation-for-peace.html (accessed May 23, 2023).

Beilin, Y., and Husseini, H. (2022). The Holy Land Confederation as a Facilitator for the Two-State Solution. Available online at: https://www.monmouth.edu/news/documents/the-holy-land-confederation-as-a-facilitator-for-the-two-state-solution-english.pdf/ (accessed May 23, 2023).

Bicchi, F. (2016). Europe under occupation: the European diplomatic community of practice in the Jerusalem area. Eur. Secur. 25, 461–477. doi: 10.1080/09662839.2016.1237942

Bicchi, F. (2018). The Occupation of Palestinian territories since 1967: an analysis of Europe's role. Global Affairs 4, 3–5. doi: 10.1080/23340460.2018.1507274

Blinken, A. (2021). Secretary Blinken's Call with Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu, May 12. Available online at: https://www.state.gov/secretary-blinkens-call-with-israeli-prime-minister-netanyahu/ (accessed August 29, 2022).

Borell, J. (2023). Answer Given by High Representative/Vice-President Borrell i Fontelles on Behalf of the European Commission. Available online at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-9-2022-000932-ASW_EN.html (accessed April 29, 2023).

Borrell, J. (2021). Israel-Palestine: Speech on Behalf of High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell at the EP debate, May 19. Available online at: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/israel-palestine-speech-behalf-high-representativevice-president-josep-borrell-ep-debate_en (accessed August 29, 2022).

B'Tselem (2021). A Regime of Jewish Supremacy from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea: This is Apartheid. B'Tselem. Available online at: https://www.btselem.org/publications/fulltext/202101_this_is_apartheid (accessed November 8, 2022).

Bulletin of the EC (10-1973). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Bulletin of the EC (6-1971). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Bulletin of the EU (3-1999). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Bulletin of the EU (6-1997). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Bulletin of the EU (6-2002). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Cohen, I. M. (2022). The right-wing “one-state solution.” Israel Stud. 27, 132–155. doi: 10.2979/israelstudies.27.1.06

Council of the European Union (2009). Council Conclusion on the Middle East Peace Process: 2985th Foreign Affairs Council Meeting, Brussels. Available online at: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cmsdata/docs/pressdata/en/foraff/111829.pdf (accessed August 29, 2022).

Daugirdas, K., and Mortenson, J. D. (2017). United States abstains on security council resolution criticizing Israeli settlements. Am. J. Int. Law 111, 477–482. doi: 10.1017/ajil.2017.18

Del Sarto, R. (2017). Israel Under Siege: The Politics of Insecurity and the Rise of the Israeli Neo-Revisionist Right. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Del Sarto, R. (2019). Stuck in the logic of Oslo: Europe and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Middle East J. 73, 376–396. doi: 10.3751/73.3.12

EEAS (2021). Israel/Palestine: Statement by the Spokesperson on Settlement Expansion and the Situation in East Jerusalem. Available online at: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/israelpalestine-statement-spokesperson-settlement-expansion-and-situation-east-jerusalem_en (accessed May 23, 2023).

EEAS MEPP (2019). EU Positions on the Middle East Peace Process. Available online at: https://eeas.europa.eu/diplomatic-network/middle-east-peace-process/49322/statement-latest-escalation-violence-between-gaza-and-israel_en (accessed August 29, 2022).

Falah, G.-W. (2005). The geopolitics of ‘Enclavisation'and the demise of a two-stateSolution to the Israeli – Palestinian conflict. Third World Quart. 26, 1341–1372. doi: 10.1080/01436590500255007

Globalsecurity.org (2022). Diplomatic Recognition. Globalsecurity.org. Available online at: https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/palestine/recognition.htm#google_vignette (accessed May 23, 2023).

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks, Reprint, 1989 Edition. London: International Publishers Co.

Huber, D. (2021). Equal Rights as a Basis for Just Peace: a European Paradigm Shift for Israel/Palestine. Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI). Available online at: https://www.iai.it/en/pubblicazioni/equal-rights-basis-just-peace-european-paradigm-shift-israelpalestine (accessed May 23, 2023).

Human Rights Watch (2021). A Threshold Crossed: Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution. Human Rights Watch. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/04/27/threshold-crossed/israeli-authorities-and-crimes-apartheid-and-persecution (accessed May 23, 2023).

Jamal, A. (2022). Jewish sovereignty and the inclusive exclusion of Palestinians: Shifting the conceptual understanding of politics in Israel/Palestine. Front. Polit. Sci. 4, 995371. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.995371

Judt, T. (2003). Israel: The Alternative. New York Review of Books. Available online at: https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2003/10/23/israel-the-alternative/ (accessed May 23, 2023).

Karmi, G. (2020). The one-state solution: an alternative vision for Israeli-Palestinian peace. J. Palestine Stud. 40, 16. doi: 10.1525/jps.2011.XL.2.62

Kvale, S., and Brinkmann, S. (2015). Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Kymlicka, W. (2001). Politics in the Vernacular: Nationalism, Multiculturalism and Citizenship | Books | Publications. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lazaroff, T. (2022). US Equates Israeli and Palestinian Extremism, Calls for Condemnation. The Jerusalem Post. Available online at: https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/article-725301 (accessed December 30, 2022).

Lovatt, H. (2016). EU Differentiation and the Push for Peace in Israel-Palestine. European Council on Foreign Affairs, 31 October. Available online at: http://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/eu_differentiation_and_the_push_for_peace_in_israel_palestine7163 (accessed August 29, 2022).

Lustick, I. S. (2019). Paradigm Lost: From Two-State Solution to One-State Reality. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Lustick, I. S. (2022). Annexation in right-wing Israeli discourse—The case of Ribonut. Front. Polit. Sci. 4, 963682. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.963682

Lustick. (2013). The Two State Illusion. New York Times. Available online at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/israel/2019-10-15/there-will-be-one-state-solution (accessed May 23, 2023).

Manners, I. (2002). Normative power Europe: a contradiction in terms. J. Common Mark. Stud. 40, 235–258. doi: 10.1111/1468-5965.00353

Ma'oz, M. (2004). The Oslo Peace Process_ From Breakthrough to Breakdown, in: Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process: Oslo and the Lessons of Failure: Perspectives, Predicaments, Prospects, eds R. Rothstein, M. Maoz, and S. Khalil (Brighton: Sussex Academic).

Milne, S. (2004). Two-State Plan at Risk, Warns Arafat. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/jan/24/israel1 (accessed May 23, 2023).

Mogherini, F. (2018). Remarks by HR/VP Mogherini at the Plenary Session of the European Parliament on the Threat of Demolition of Khan al-Ahmar and Other Bedouin Villages, Strasbourg, September 11. Available online at: https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/50333/remarks-hrvp-mogherini-plenary-session-european-parliament-threat-demolition-khan-al-ahmar-and_en (accessed August 29, 2022).

Morris, B. (2009). One State, Two States: Resolving the Israel/Palestine Conflict. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Müller, P. (2019). Normative power Europe and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: the EU's peacebuilding narrative meets local narratives. Eur. Secur. 28, 251–267. doi: 10.1080/09662839.2019.1648259

Munayyer, Y. (2013). “Thinking Outside the Two-State-Box”, The New Yorker. Available online at: https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/thinking-outside-the-two-state-box (accessed May 5, 2023).

Munayyer, Y. (2019). There will be a one-state solution: but what kind of state will it be? Foreign Affairs 98, 30. Available online at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/israel/2019-10-15/there-will-be-one-state-solution (accessed May 23, 2023).

Nieli, R. (2009). Finally, a new idea: the marriage of a one-state and a two-state solution. Tikkun 24, 33–40. doi: 10.1215/08879982-2009-4013

Nimni, E. (2020). The twilight of the two-state solution in Israel-Palestine: Shared sovereignty and nonterritorial autonomy as the new dawn. Nation. Papers. 48, 339–356. doi: 10.1017/nps.2019.67

OHCHR (2022). Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in the Occupied Palestinian Territories: Israel Has Imposed Upon Palestine an Apartheid Reality in a Post-apartheid World. Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/03/special-rapporteur-situation-human-rights-occupied palestinian-territories (accessed April 21, 2023).

Pace, M. (2016). The EU and its trickster practices: the case of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Global Affairs 2, 405–407. doi: 10.1080/23340460.2016.1243328

Peleg, I. (2005). The zionist right and constructivist realism: ideological persistence and tactical readjustment. Israel Stud. 10, 127–153. doi: 10.2979/ISR.2005.10.3.127

Persson, A. (2017). Shaping discourse and setting examples: Normative Power Europe can work in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. J. Comm. Mark. Stud. 55, 1415–1431. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12578

Persson, A. (2020). EU Diplomacy and the Israeli-Arab Conflict, 1967–2019. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Pressman, J. (2021). Assessing One-State and Two-State Proposals to Solve the Israel-Palestine Conflict. E-International Relations. Available online at: https://www.e-ir.info/2021/06/27/assessing-one-state-and-two-state-proposals-to-solve-the-israel-palestine-conflict/ (accessed September 16, 2022).

Ram, U. (2003). “From nation-state to nation-state. Nation, history and identity struggles in Jewish Israel,” in The Challenge of Post-Zionism. Alternatives to Israeli Fundamentalist Politics, eds. E. Nimni (New York, NY: Zed Books).

Ram, U. (2011). Israeli Nationalism: Social Conflicts and the Politics of Knowledge. London; New-York, NY: Routledge.

Ron Frohlich, J. (2011). Palestine, the UN and the one-state solution. Middle East Policy 18, 59–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4967.2011.00510.x

Ross, D. (2005). The Missing Peace: The Inside Story of the Fight for Middle East Peace, First edition. ed. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.