94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 28 March 2023

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1000511

This article is part of the Research Topic Contemporary Threats, Surveillance, and the Balancing of Security and Liberty View all 5 articles

Tolerating others' opinions, even if disliked, is a cornerstone of liberal democracy. At the same time, there are limits to political tolerance as tolerating extremists and groups who use violence would threaten the foundations of tolerance itself. We study people's willingness to set limits to tolerance in case of violence and extremism (scope of tolerance)—under different conditions regarding ideological groups (left-wing, right-wing, religious) and offline/online contexts of free speech. Using data from a large-scale survey experiment conducted in Germany, we show that citizens clearly set limits to tolerance of different groups, especially if the latter have violent intentions, and that people tend to be more tolerant online than offline. Moreover, we find that citizens are more tolerant toward groups that are closer to their own ideological stance. However, violence disrupts such an ideological bias as respondents across the ideological spectrum exhibit low levels of tolerance toward violent groups—irrespectively of their political stance. Our findings highlight the importance of situational factors as foundations of judgments on the limits to tolerance.

The core of political tolerance is to accept equal civil rights and liberties for all groups, including those who express completely different political opinions or do not conform to social norms (Stouffer, 1955, p. 21). Tolerance is not only necessary for cohesion in today's fragmented societies: Only if the expression of dissent is possible, for example through the freedom of speech and the right to assembly, the conditions for decision-making in the form of a marketplace of ideas can be met. Tolerance as a fair procedural principle and element of democratic competition is indispensable for a vital democracy (Dahl, 1971), as are moments of intolerance toward enemies of democratic rights. For instance, different forms of protest against policies to combat COVID-19 have shown how difficult it can be to define the right spaces and boundaries for tolerance of expression in the face of radicalizing worldviews.

Questions related to civil liberties and limits to tolerance are increasingly discussed in the last years in face of various threats to democracies such as the rise of anti-system parties, or a high number of individuals willing to engage in political violence. Political scientists investigate these issues, for instance, in scientific debates about democratic backsliding (e.g., Waldner and Lust, 2018), or militant democracy (e.g., Müller, 2016 with an overview), but we need to know more about citizens' attitudes toward violations of democratic norms. In this study, we focus on violence and extremism as potential boundaries for political tolerance. We examine the contextual contingency of citizens' tolerance judgments using a unique vignette experiment on freedom of speech that varies the group expressing opinions, non-violent vs. violent expression, and online vs. offline settings. Specifically, we focus on both ideological groups and individual ideological positions and analyze the role of ideological bias in tolerance judgments, meaning that—for instance—people who are left-wing are more willing to tolerate left-wing groups even if the latter exhibit acts of violence, which is typically seen as a clear boundary for tolerance (Gibson, 2011). This research complements existing studies on tolerance, which have often focused on individual differences (e.g., Marcus et al., 1995; Freitag and Rapp, 2015) rather than ideological and contextual conditions under which people become more or less likely to tolerate opposing opinions.

We are interested in whether or not an ideological bias exists with reference to extremism and violence—as such a bias can lead to overstepping the boundaries of democratic political tolerance. To put this in other words: Are people willing to trade non-violence as a lynchpin of democratic functioning for ingroup favoritism? This question is particularly relevant against the background of violent anti-democratic incidents such as the recent attacks of right-wing extremist groups on government buildings in the United States and Brazil.1 More generally, such occasions of group-based anti-democratic violence are rooted in deeper political divides and tendencies of polarization (Iyengar et al., 2019). Although the extent of political polarization may differ across countries, most Western societies have witnessed an increase in either polarization regarding political issues (e.g., immigration or abortion rights), affective polarization (i.e., viewing partisans of one's own party positively and partisans of other parties in negative terms), or both (Westwood et al., 2018; Wagner, 2021). Another critical debate of tolerance and intolerance has been centered on hate speech expressed in online settings, especially in social media (Theocharis et al., 2020; Castaño-Pulgarín et al., 2021). Our paper builds on this research by employing online vs. offline as two different contexts of tolerance judgments. Specifically, we analyze tolerance judgments regarding internet usage and, as a more “traditional” context of tolerance, public meetings of different groups.

To examine tolerance judgments related to different groups, intentions, and contexts, the study makes use of an experiment embedded in a telephone survey of a random sample of adults living in Germany in 2016. Our results show that citizens are sensitive toward specific circumstances under which tolerance is exercised. Compared to left-wing groups, right-wing and religious groups receive less tolerance for whether or not these groups are framed to be violent. Violent intentions or behavior decrease people's readiness of expressing political tolerance, online activities are more likely to be tolerated than incidents in offline settings. Regarding ideological biases, we find that citizens tend to tolerate groups with an ideological profile closer to their own more than ideologically distant groups. At the same time, ideological bias is present when groups are considered extremist. However, our results show low political tolerance for groups that are violent—independently of respondents' own ideology. This means that patterns of violence interrupt the dynamic of ideological bias, which is positive news for democracy.

Tolerance is not an absolute and fixed value. In a democracy, intolerance toward intolerants is required in some situations (Verkuyten and Yogeeswaran, 2017, p. 73). Accordingly, it is important to consider the limits to tolerance set by the citizens depending on the activities and intentions of the groups or acts to be tolerated. More than that, for an adequate assessment of the antecedents of political tolerance, we need to distinguish between tolerance of the actor and tolerance related to the nature of the actor's behavior (e.g., Hurwitz and Mondak, 2002; Jones and Bejan, 2021, p. 608).

The use of violence can be regarded as a clear limit of tolerance (Gibson, 2011, p. 411). It constitutes a serious violation of the prevailing rules of coexistence in our societies. This way, violence not only undermines the monopoly of the state in exercising violence but also the liberal-democratic foundations of tolerance itself. Instead of a marketplace of ideas in which a variety of voices aim for making themselves heard, violence silences this competition and creates a situation in which the most powerful get their way. Presuming that citizens in democratic societies tend to be aware of the destructive consequences of group-based violence, the reference to violence should lead to a reduction in the level of tolerance in the population.

Several studies show that people often point to extremism and potential use of violence as a reason not to tolerate particular actors or least-liked groups (e.g., Kuklinski et al., 1991; Sullivan et al., 1993), but little research has been done yet on how explicit references to extremism influence tolerant attitudes. In their discussion of the measurement of political tolerance, Gibson and Bingham (1982, p. 607) report significantly less tolerance toward “speech designed to incite an audience to violence” compared to other forms of speech. Marcus et al. (1995) and Crawford (2014) point to the consequences of normative violations or a threat to people's rights for tolerant attitudes. In their experimental study, Petersen et al. (2011) observe that tolerance judgments are dependent on a group's association with the use of violence and with non-democratic behavior. However, the extreme and violent intentions of the groups examined are not explicitly mentioned. This means that the particular relevance of characteristics associated with extremism such as readiness for violence or ideological deviance can often not be disentangled from their research design (Petersen et al., 2011, p. 596).

Building on this work, we aim for separating the aspects of ideology, extremism, and violence experimentally by either referring to a group's ideology in a non-extremist way, a group's political extremism, or a group's violent intentions. In line with previous works, we expect that priming a group's extremism actually leads to less tolerant attitudes compared to merely mentioning their ideological stance (H1a). Information on the use of violence by different groups is expected to reduce the tolerance of these groups even further (H1b).

Embedding tolerance in situational contexts, judgments about whether or not free speech should be allowed might vary depending on how and where this right is exercised. To give just one example: Chanley (1994) shows that it makes a difference whether a nonconformist may exhibit a book in the library or whether the same person may teach at a school. While there has been much focus on classical forms of exercising political rights, such as the right to hold meetings, research on toleration of free expression in the online and social media context is still fragmented (with a few studies on online hate speech, e.g., Guo and Johnson, 2020). While there are positive effects of online communication on different aspects of political life (e.g., Shah et al., 2016), clearly one of the downsides of the Internet is the widespread phenomenon of online hate production (e.g., Kaakinen et al., 2018). Therefore, it is important to account for the Internet as a context of tolerance.

When comparing tolerance of political expression on the Internet with traditional exercises of political rights, there are two positions: First, individuals might think about rights exercised in the online context in a similar way as offline, which would mean no substantial differences in tolerance judgment between online and offline contexts. As this implies stable attitudes that are insensitive to situational variations when it comes to group activities, this presumption is rather implausible and contrary to findings on the role of context in evaluations of groups (Sibley et al., 2013). Instead, we follow a second perspective according to which people can be expected to tolerate free speech in an online context more than in offline contexts. The main reason is that real-life consequences of extremism and violence are much less proximate on the Internet than offline.2 Moreover, state regulation of Internet communications remains limited due to the time lag between new media development and jurisdiction and the transnational nature of online content (Naab, 2012), which means that legal boundaries of free speech are less developed for online content compared to traditional forms of group activities such as holding a public meeting. From a legal norms perspective, this should render more extreme forms of public speech on the Internet as being more tolerable than offline (H2).

To account for differences in a group's political ideology, we examine tolerance toward left-wing groups, right-wing groups, and radical religious groups. Extremists from these camps make up the majority of organizations under observation by the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution.3 All three kinds of groups can be associated with a broad spectrum of political ideology and activities with different degrees of intensity. In its least intense form, left-wing groups advocate redistribution of wealth and income (in order to reduce economic inequality) for which some form of state activity is necessary, as well as equal treatment regardless of individuals' group membership and characteristics. Right-wing groups often focus on nativism and tend to heighten ingroup bias which, in Western societies, becomes evident in a critical or opposing stance toward immigration and non-traditional ways of life (De Vries et al., 2013; Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos, 2020).

In its pronounced form, left-wing extremist groups set the equality of people as absolute, while right-wing extremist groups negate group-related principles of equality and inclusion. Both ideologies converge on the notion that restricting individual liberties (and thus societal pluralism) is necessary to ultimately reach their goal. Many religious groups share with right-wing groups a critical stance toward non-traditional ways of life. Radical religious groups, such as radical Islamic movements, often criticize liberal, secularized ways of life—while they themselves represent a non-traditional group in Western societies (Kastoryano, 2004). At the same time, right-wing groups are less tolerant of Muslim groups which is related to the symbolic and social status threat Muslim immigrants may represent to these groups (Hafez, 2014).

We expect right-wing and radical religious groups to receive particularly limited political tolerance when seeking free speech compared to left-wing groups (H3). First, this expectation arises from reports on extremism in Germany (e.g., Grumke, 2020), showing that the actual threatening potential (in terms of extremism and violence) from left-wing groups is lower than for right-wing or radical Islamic groups. Second, the threat from right-wing extremism was very salient in Germany after the killings of the terrorist group NSU. Third, recent work on tolerance in Europe lists right-wing extremists as the most-disliked groups, followed by Muslims far behind (Stoeckel and Ceka, 2022).

Individuals differ in the extent to which they are ready to tolerate others. Research on political tolerance showed early on that most citizens express a strong belief in democratic values, but only a small proportion of them are ready to apply these values to groups they dislike (Marcus et al., 1995).

The role of ideological differences—as an individual-level characteristic—on tolerance judgments has been investigated in several studies so far (Sullivan et al., 1981; Marcus et al., 1995). Most of these studies find that people are ideologically biased in terms of which group they are ready to tolerate. In other words, people who self-identify as belonging to the political right are less likely to tolerate acts of left-wing groups (e.g., socialists) and more likely to tolerate acts of right-wing groups (e.g., nationalists, racists), while the opposite is the case for those who self-identify as left-wing. Regarding underlying reasons for this ideological bias, perceptions of ideological congruence (between individually held ideology and the ideology of the group to be tolerated) might serve as a cue that the group to be tolerated has a similar political cause. This turns an act of tolerance into a contribution to one's own political utility function (Mason and Wronski, 2018). Another reason for this bias might be an overlap in social identity which facilitates political tolerance. People strive for a positive social identity and connect more easily with others who display signs related to their own social identity (Tajfel and Turner, 1986). In a similar vein, research on intergroup dynamics shows that people are more willing to tolerate others if they seem to match the perceived prototypicality of the social group they identify with (Wenzel et al., 2008). We conclude from this strand of research that people should be expected to tolerate the group with an ideological profile that is closer to their own more than a group with an incongruent ideological profile.

Apart from these expectations, we move beyond existing studies by investigating the extent to which ideological bias may operate as a boundary condition for how the use of extremism or violence relates to tolerance judgments. A first line of argument suggests that people uphold their ideological bias even if extremism or violence are mentioned and thus potentially put limits to tolerance judgments. This argument is connected to the literature on political polarization highlighting far-reaching ideological divides that contaminate a broad range of social and political life (Iyengar et al., 2019) and can be fostered through biases in information processing (Hameleers and Brosius, 2022). This can be thought of as a situation of critical group conflict in which ingroup loyalty and outgroup hostility trump intentions of promoting the common good (Habyarimana et al., 2007). Following this perspective, ideological bias might be present when it comes to questions of political tolerance even if groups are extremist or use violence.

A second set of arguments suggests that ideological bias is likely to be present when ideological differences between groups are made salient, but that this bias is mitigated when the groups to be tolerated are extremist or make use of violence. Political tolerance is not an absolute value but rather a syndrome of attitudes (Gibson and Bingham, 1982, p. 604)—with decisions to tolerate (or not) depending on the context. People are able to weigh different priorities depending on the context of tolerance, and extremism or the use of violence might be important reasons for many people to reject the activities of groups even if they belong to the same ideological “camp”. In other words, ideological groups are willing to let go of their ideological bias in favor of ensuring proper limits of political tolerance. And we know from previous research that citizens reject the use of force in many contexts, when it comes to the issue of torture, for example (Nincic and Ramos, 2011). Violence and extremism would therefore send clear signals to citizens to set limits to tolerance. Following this line of argument, we expect that ideological bias in political tolerance is mitigated when extremism or violence is mentioned (compared to the simple description of ideological characteristics of groups) (H4).

The tolerance experiment was embedded in a nationwide telephone survey (random sample) conducted in Germany in 2016 in the context of a research project on “Conditional support for civil liberties and preferences for domestic security policies among citizens in Germany” (grant number: 270157613). The target population of the survey consisted of persons of the age of 18 and older living in private households. Our population-based survey experiment thus allows for assigning a large and diverse sample to experimental conditions (Mutz, 2011). 2004 interviews were conducted between April 12 and June 7, 2016. More information on the survey and the study design can be found in the Online Appendix.

Figure 1 shows the experimental design and the exact wording of the treatment conditions. The experiment focuses on tolerance judgments concerning public meetings and Internet usage of different groups as a dependent variable (“Should the following groups be allowed to hold public meetings?” or “should government agencies be able to block websites of the following groups?”). Essentially, both variables refer to allowing vs. restricting the freedom of speech of specific groups—a question that is at the heart of many debates on freedom of expression and the limits to hate speech (Harell, 2010). Responses to these questions were coded as 0 (restricting freedom of speech) or 1 (allowing freedom of speech; i.e., the group should be allowed to hold public meetings; government agencies should not be able to block the websites of the group).

Respondents were randomly assigned to one of the two settings, meaning that those answering the public meetings question are assigned to the “offline” condition, and those answering the block website question are assigned to the “online” condition (i.e., between-subject design aspect). We included this binary variable (0 = offline, 1 = online) as an additional treatment variable.

All respondents were asked about three groups as targets of tolerance: We emphasized for left-wing groups (a) that they favor disowning rich citizens as a distinct way of enforcing redistribution, which can be easily exaggerated into more extremist or even violent characteristics. For right-wing groups (b), we highlighted their position regarding foreigners in the country as anti-immigration rhetoric is a publicly salient attribute, especially in the West European context where populist radical right parties such as the German Alternative für Deutschland gained increased electoral support in the past years (Schulte-Cloos, 2022). Religious groups (c) are less known for advocating economic issues, and since the socio-cultural dimension of traditionalism is already occupied by right-wing groups we emphasized that these religious groups support radical (Islamic) preachers. We shortly described against whom these groups are directed in order to be more specific and to go beyond certain keywords (e.g., xenophobic) that leave room for varying interpretations.

The three groups are included as dummy variables, which allows us to study the role of ideological motivations in the process of political tolerance. Since all three groups have been presented to each respondent (i.e., within-subject design aspect), we account for non-independent observations by using random effects models (cf. Section 3.4.).

To experimentally test the relevance of these groups' intentions and their potential for violence (i.e., the scope of the tolerance act), respondents were randomly assigned to three experimental conditions. The first condition, referred to as the control group (T1), only contained the description of the groups described above (“only group mentioned”). In the second experimental condition (T2), the respective groups were described as extremist or radical (right-wing extremist, left-wing extremist, radical Islamist) (“extremism mentioned”). The third experimental condition (T3) referred to the potential for violence of the three groups (“violence mentioned”). More precisely, respondents were asked to tolerate groups that threaten foreigners with harm, groups that want to forcefully disown rich citizens, and violent groups supporting radical preachers. These three variables were included as scope conditions of the tolerance act.

To be able to examine the balance between groups (Gerber et al., 2014), Table A1 in the Appendix provides means, standard deviations, and an F-test on differences between groups for the key variables of the following analysis. It shows that the participants in the experimental groups do not differ significantly regarding the different characteristics and attitudes relevant to this study.

In order to assess the variability in the treatment effects depending on one's ideological orientation, we use political ideology measured via an individual's self-placement on the left-right scale.

We equally include several control variables. Many studies have already highlighted the role of education in political tolerance (Golebiowska, 1995). Highly educated individuals may express greater tolerance, on average, because they have been more frequently exposed to diverse social networks and ideas which, in turn, increases their readiness for political tolerance (Napier and Jost, 2008; Cavaille and Marshall, 2019). We measure education by the respondent's highest general school-leaving qualification or by his/her attainment of a university degree. In doing so, we can compare individuals with four levels of formal education, namely with no or low formal education, with an intermediary level of secondary qualification, with a high school diploma or similar, and with a university degree. As we compare an online and an offline context of tolerance, we equally control for the individual use of the Internet. Finally, we include age, a person's gender (0: male, 1: female), and a variable differentiating between East and West Germany as people in a region with a shorter history of democracy (East Germany) might have different ways of putting democratic principles into the practice of tolerance (Marquart-Pyatt and Paxton, 2007).

These variables are mainly included in order to reduce (random) measurement error—which may have arisen from small (random) differences in the distribution of relevant covariates even after the randomization related to the vignette experiment took place (e.g., due to small sample size). Omitting the controls leads to substantially similar results as reported below. More information on the included variables (descriptives, question wording) is reported in Table A2 and Table A3 in the Appendix.

To determine the (conditional) effect of the treatment variables on political tolerance, we employ multilevel modeling and include a random intercept at the level of respondents that addresses the within-design part of the experiment (vignettes nested within respondents). This accounts for potentially biased standard errors due to the non-independence of observations. Moreover, the outcome is a dichotomous variable. Instead of using a logit link function, we use a linear probability model (i.e., a linear multilevel regression with heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors). Such a model produces intuitively interpretable estimates (in terms of changes in the probability that Y_i = 1) and typically leads to similar conclusions as a logistic regression model (Breen et al., 2018). In our case, a logistic multilevel regression model produces comparable results in terms of effect sizes and statistical significance of estimates. For conditional effects analyses, we use a group comparison approach by employing self-assessed ideology (left-right self-placement) as the moderator variable. Due to convergence issues, we estimate a linear probability model for the conditional models with cluster-robust standard errors instead of a multilevel specification. To assess statistical significance, we present results from interaction effects analyses and graphically depict predicted values for each of the ideological groups (left-wing, right-wing, religious) depending on group characteristics (only group mentioned, extremism mentioned, violence mentioned) and the ideology of respondents.

In the first step, we descriptively compare the degree of tolerant reactions toward different groups in the contexts of public meetings and websites (in percent). Figure 2 shows the percentage of tolerant answers for offline vs. online conditions—the upper part refers to public meetings, and the lower part refers to websites. Bars represent different treatment conditions (group mentioned, extremism mentioned, violence mentioned) for each of the three groups (left-wing group, right-wing group, and religious group). The differences in tolerance levels across the three experimental conditions show that the intentions of the groups do indeed play a major role in tolerance judgments. In most cases, the tolerance of respondents is highest if no reference is made to extremism or violent intentions.

Introducing a reference to extremism and violence, in particular, provokes clear limits to tolerance, as the percentage of tolerant answers in the condition of receiving the violence treatment is significantly lower than in the other two experimental conditions. Violent intentions reduce the willingness to tolerate the corresponding groups by almost half. The description of the groups as extremists also leads to less tolerance, but not to the same extent as the cue of violence. Compared to the baseline condition, the differences in tolerance levels under the violence condition are statistically significant for all the descriptive comparisons, while the differences in tolerance for the extremism condition are statistically significant in several cases (not significant in three out of six scenarios).

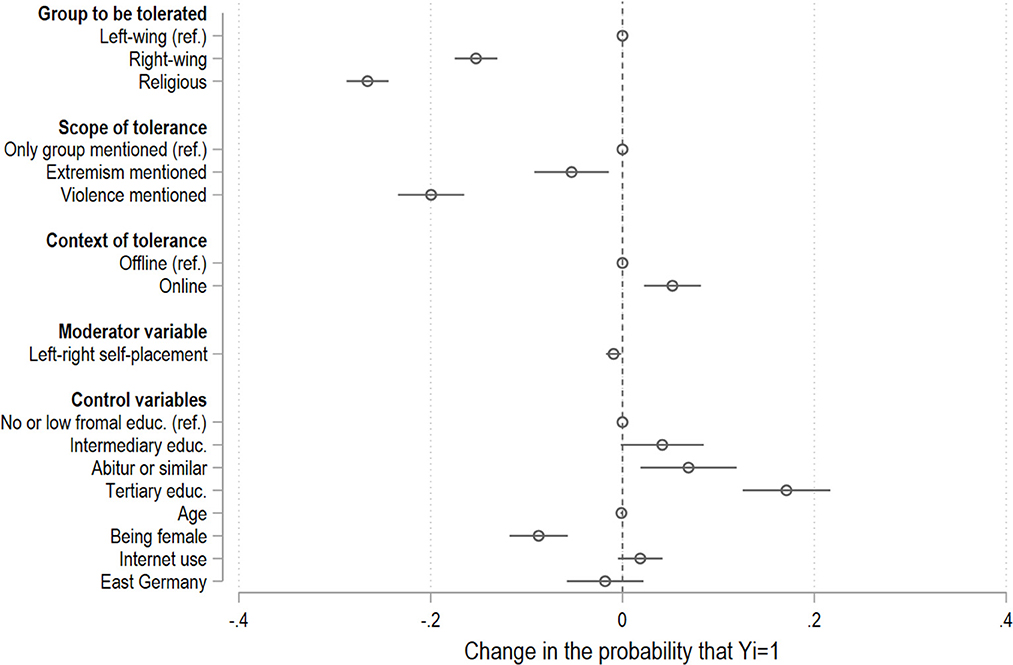

In the next step, we examine the different treatment variables in an overall regression model and also include observed respondent characteristics in order to reduce the impact of random measurement error. Figure 3 shows the corresponding coefficient plot, and the underlying results are presented in Table A4 in the Online Appendix. Regarding the scope of tolerance, the regression model mirrors the descriptive findings. Compared to the baseline condition (only group mentioned), making extremism salient leads to a decrease in the probability of observing political tolerance by 5.3 % while making violence salient leads to a decrease of 20 %. This finding provides empirical evidence in line with Hypotheses 1a and 1b. Both effects are statistically significant (p < 0.01),4 and since the underlying variable is experimental, the effects can be interpreted as being causal.

Figure 3. Results from linear probability models (Model 1, Outcome political tolerance). Coefficient estimates with 95% confidence intervals are shown. Underlying estimates and standard errors are shown in the Table A4 in the Appendix.

Regarding the groups mentioned, we find that respondents are substantially less likely to tolerate right-wing (−15.3 %, p < 0.01) or radical religious groups (−26.6 %, p < 0.01), which is in line with Hypothesis 3.5 About the context of tolerance, we find that respondents in the online condition are 5.2 % more likely to express political tolerance compared to those in the offline condition (p < 0.01). This result thus provides empirical support for Hypothesis 2.

Concerning the non-experimental respondent-level characteristics, we find that women and younger respondents are less likely to express political tolerance, while those highly educated (tertiary education compared to those with no or low formal education) are substantially more likely to tolerate. However, living in East Germany and the frequency of internet usage show no systematic association with political tolerance.

In the next step, we examine the extent of ideological bias among citizens by focusing on responses to each of the political groups separately. The corresponding regression estimates are presented in Table 1. First, we examine the role of ideological orientation as a predictor variable in Models 1, 3, and 5. The results show that the more respondents identify as being right-wing, the less likely they tolerate left-wing and religious groups and the more likely they tolerate right-wing groups. In contrast, being left-leaning implies more tolerance for left-wing and religious groups and less tolerance for right-wing groups. This is a clear indication of ideological bias.

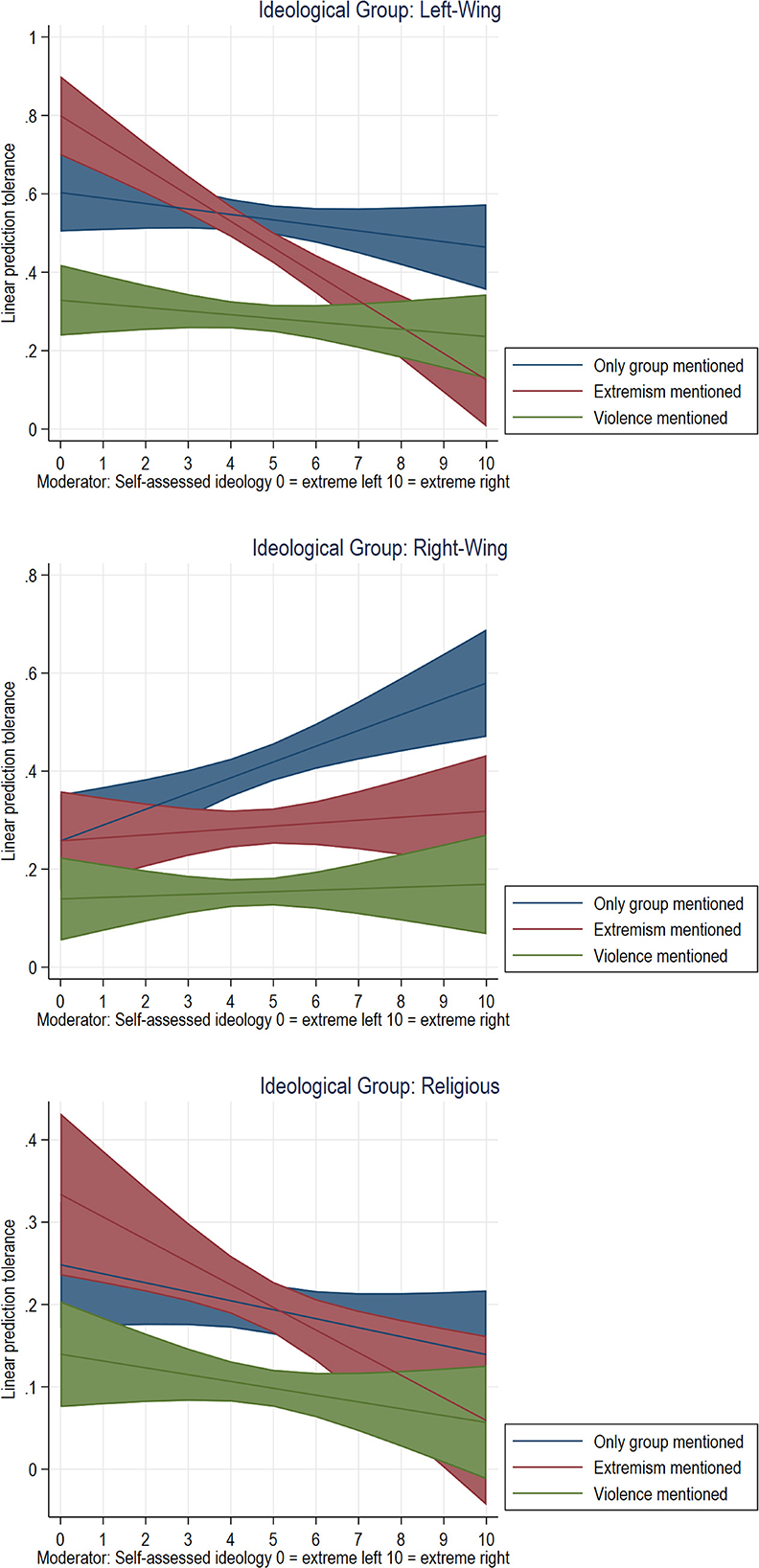

Second, we examine the role of ideological orientation as a moderator. The corresponding predicted marginal means are depicted in Figure 4. Regarding left-wing groups, we find average tolerance to be highest for groups that are not described as extremist or violent, followed by groups described as extremist. Violence elicits the lowest amount of tolerance. People on both sides of the political spectrum tolerate violence to a similarly low degree, which is a key finding of our analysis. We find substantial differences when it comes to extremism. People who perceive themselves as being left-wing tolerate left-wing extremist groups more than those who identify as being right-wing. Right-wing groups are tolerated to a very limited degree by those who identify as left-wing, while right-wing individuals tolerate them to a greater extent, less so if extremism is mentioned, and substantially less (and comparable to left-leaning individuals) if the use of violence is mentioned. Religious groups are more tolerated by left-wing individuals (compared to right-wing individuals), while the differences between a simple description of the group, their description as extremist, and the mentioning of violence are not systematic. In summary, we find an ideological bias in the case of extremist groups, but no ideological bias for violence—regardless of which ideological profile a group has. In support of Hypothesis 4 we find empirical evidence for a nuanced narrative according to which an ideological bias exists concerning extremism, but a rather unified negative response to violence.

Figure 4. Ideological group differences in treatment effects—ideological orientation. Coefficient estimates with 95% confidence intervals are shown.

Our study provides several key messages relevant for further research and for an assessment of political tolerance in contemporary societies: First, the willingness to grant civil liberties to groups is severely restricted by violent intentions of these groups. Any reference to violence decreases people's readiness to grant political tolerance to groups, regardless of the ideological position of the group. This is the case across the different contexts examined here. This result suggests that citizens are aware of one of the limits to tolerance that is critical for a functioning democracy. This is an important finding, as previous studies on political tolerance had often addressed the important question of “allow what” from the citizens' perspective, but there are only a few empirical answers to it.

Second, we find that citizens are slightly more tolerant online than offline. We must be cautious in interpreting this result because the presentation of the two tolerance contexts differs (especially as state intervention is mentioned in the online condition)—the two cases are not comparable in a narrow sense but rather represent relevant examples for an online and an offline context. However, the result shows the need for further assessing intolerance on the Internet—and we think that the discussion of particularities of the online context (e.g., Brown, 2018) should be expanded in research on tolerance.

Third, our results show that ideological bias plays a role in citizens' tolerance judgments. However, violence in the intentions of groups is a clear signal for citizens to set limits to tolerance, ideological affinities, or antagonisms recede well into the background. This is a key message of our analyses directed against a picture of deeply polarized societies, in which ideological divides cloud citizens' views on antidemocratic tendencies.

This study also has several limitations: First, our study examines citizens' limits to tolerance in cases of violence and extremism. The results regarding extreme groups are less clear-cut than those regarding violent groups. This may be due to the strength of the hint of violence, but also to the fact that the public might associate varying ideologies and movements with varying degrees of extremism. Future studies could deepen our research at this point and analyze different connotations of extremism that prevail among the population. They could also differentiate even more explicitly between assigned group characteristics and specific statements or actions to be tolerated, whereby this improvement in internal validity (i.e., identification of tolerance toward groups vs. actions) would certainly also come at the expense of external validity (i.e., correspondence to real-life social situations in which group characteristics and behaviors are often intertwined). Second, another avenue for research would be focusing on groups other than those examined in this study such as radical climate activists. Third, our description of the online condition concentrates on the question of whether the websites of particular groups should be blocked or not. Thus, we account for only one possible form of (in-)tolerance in the online context. Future work should deal with “a wider range of responses to difference” online (Jones and Bejan, 2021, p. 609), and, for example, combine different targets as well as specific actions and communication channels (e.g., websites, Twitter, blogs) that may lead to (in-)tolerance.

In summary, our study provides causal evidence on conditions under which people put limits to political tolerance, showing a high degree of attentiveness to the topic of violence and the ideological background of groups. This can be understood in an optimistic way, namely that people are ready to defend democratic principles of tolerance and to set clear boundaries for the anti-democratic behavior of groups. At the same time, the very same results convey the cautionary tale that framing groups as being violent potentially contributes to their social and political exclusion, whether this frame is justified or not.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

EMT and CZ designed research for this article, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. EMT collected the data and performed research in the larger framework of the research project. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

EMT acknowledges funding by the German Research Foundation for the research project “Conditional support for civil liberties and preferences for domestic security policies among citizens in Germany” (grant number: 270157613). CZ acknowledges funding by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation for the project “Democracy in Crisis: The Role of Emotions and Affective Polarization for Citizens' Political Support During Threatening Events.”

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2023.1000511/full#supplementary-material

1. ^https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/09/us/capitol-rioters.html and https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/09/brazil-bolsonaro-lula-brasilia-attacks-insurrection

2. ^This is not to say that online activities such as bullying have no manifest impact on people's lives (Vaillancourt et al., 2017). Nevertheless, it is easier to opt out on social media platforms than to avoid a protest or rally in one's neighborhood that is visible and proximate. We want to reiterate that the empirical material we use in this study is from 2016, and that we are aware that online activities have become more predominant during the past couple of years, especially during the Corona pandemic. We also acknowledge that connections, for example, between online harassment and offline violence exist (Van der Vegt et al., 2021) that nonetheless go beyond the scope of this study.

3. ^https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/916924/bdc6ab9dce71fbbd94137b995dbca42b/WD-3-107-22-pdf-data.pdf

4. ^The difference between the extremism and violence condition (b = −0.147) is also statistically significant (p < 0.01).

5. ^The difference between radical religious and right-wing groups is 11.3% and statistically significant (p < 0.01).

Breen, R., Karlson, K. B., and Holm, A. (2018). Interpreting and understanding logits, probits, and other nonlinear probability models. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 44, 39–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041429

Brown, A. (2018). What is so special about online (as compared to offline) hate speech? Ethnicities 18, 297–326. doi: 10.1177/1468796817709846

Castaño-Pulgarín, S. A., Suárez-Betancur, N., Vega, L. M. T., and López, H. M. H. (2021). Internet, social media and online hate speech. Systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 58, 101608. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2021.101608

Cavaille, C., and Marshall, J. (2019). Education and anti-immigration attitudes: Evidence from compulsory schooling reforms across Western Europe. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 113, 254–263. doi: 10.1017/S0003055418000588

Chanley, V. (1994). Commitment to political tolerance: Situational and activity-based differences. Pol. Behav. 16, 343–363. doi: 10.1007/BF01498955

Crawford, J. T. (2014). Ideological symmetries and asymmetries in political intolerance and prejudice toward political activist groups. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 55, 284–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2014.08.002

De Vries, C. E., Hakhverdian, A., and Lancee, B. (2013). The dynamics of voters' left/right identification: The role of economic and cultural attitudes. Pol. Sci. Res. Methods 1, 223–238. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2013.4

Freitag, M., and Rapp, C. (2015). The personal foundations of political tolerance towards immigrants. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 41, 351–373. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2014.924847

Gerber, A., Arceneaux, K., Boudreau, C., Dowling, C., Hillygus, S., Palfrey, T., et al. (2014). Reporting guidelines for experimental research: a report from the experimental research section standards committee. J. Exp. Pol. Sci. 1, 81–98. doi: 10.1017/xps.2014.11

Gibson, J. (2011). Political intolerance in the context of democratic theory. In: Goodin, R. E. The Oxford Handbooks of Political Science. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 409–27.

Gibson, J. L., and Bingham, R. D. (1982). On the conceptualization and measurement of political tolerance. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 76, 603–620. doi: 10.2307/1963734

Golebiowska, E. A. (1995). Individual value priorities, education, and political tolerance. Pol. Behav. 17, 23–48. doi: 10.1007/BF01498783

Grumke, T. (2020). Verfassungsschutzbericht 2018. In Jahrbuch Extremismus and Demokratie (E and D). Baden-Baden: Nomos. p. 377–379.

Guo, L., and Johnson, B. G. (2020). Third-person effect and hate speech censorship on Facebook. Soc. Media Soc. 6, 205630512092300. doi: 10.1177/2056305120923003

Habyarimana, J., Humphreys, M., Posner, D. N., and Weinstein, J. M. (2007). Why does ethnic diversity undermine public goods provision? Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 101, 709–725. doi: 10.1017/S0003055407070499

Hafez, F. (2014). Shifting borders: Islamophobia as common ground for building pan-European right-wing unity. Pat. Preju. 48, 479–499. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2014.965877

Hameleers, M., and Brosius, A. (2022). You are wrong because I am right! The perceived causes and ideological biases of misinformation beliefs. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 34, edab028. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edab028

Harell, A. (2010). Political tolerance, racist speech, and the influence of social networks. Soc. Sci. Q. 91, 724–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00716.x

Hurwitz, J., and Mondak, J. J. (2002). Democratic principles, discrimination and political intolerance. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 32, 93–118. doi: 10.1017/S0007123402000042

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., and Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Ann. Rev. Pol. Sci. 22, 129–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Jones, C. W., and Bejan, T. M. (2021). Reconsidering tolerance: insights from political theory and three experiments. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 604–623. doi: 10.1017/S0007123419000279

Kaakinen, M., Räsänen, P., Näsi, M., Minkkinen, J., Keipi, T., and Oksanen, A. (2018). Social capital and online hate production: a four country survey. Crime Law Soc. Change 69, 25–39. doi: 10.1007/s10611-017-9764-5

Kastoryano, R. (2004). Religion and incorporation: Islam in France and Germany. Int. Mig. Rev. 38, 1234–1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00234.x

Kriesi, H., and Schulte-Cloos, J. (2020). Support for radical parties in Western Europe: Structural conflicts and political dynamics. Elect. Stud. 65, 102138. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102138

Kuklinski, J. H., Riggle, E., Ottati, V., Schwarz, N., and Wyer, R. S. (1991). The cognitive and affective bases of political tolerance judgments. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 35, 1–27. doi: 10.2307/2111436

Marcus, G. E., Theiss-Morse, E., Sullivan, J. L., and Wood, S. L. (1995). With Malice Toward Some: How People Make Civil Liberties Judgments. Cambridge, New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press.

Marquart-Pyatt, S., and Paxton, P. (2007). In principle and in practice: Learning political tolerance in Eastern and Western Europe. Pol. Behav. 29, 89–113. doi: 10.1007/s11109-006-9017-2

Mason, L., and Wronski, J. (2018). One tribe to bind them all: how our social group attachments strengthen partisanship. Pol. Psychol. 39, 257–277. doi: 10.1111/pops.12485

Müller, J. W. (2016). Protecting popular self-government from the people? New normative perspectives on militant democracy. Ann. Rev. Pol. Sci. 19, 249–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-043014-124054

Naab, T. K. (2012). The relevance of people's attitudes towards freedom of expression in a changing media environment. J. Commun. Stud. 5, 45–67.

Napier, J. L., and Jost, J. T. (2008). The Antidemocratic Personality revisited: A crossnational investigation of working-class authoritarianism. J. Soc. Issu. 64, 595–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00579.x

Nincic, M., and Ramos, J. (2011). Torture in the public mind. Int. Stud. Perspect. 12, 231–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-3585.2011.00429.x

Petersen, M., Slothuus, R., Stubager, R., and Togeby, L. (2011). Freedom for all? The strength and limits of political tolerance. Br. J. Pol. Sci. 41, 581–597. doi: 10.1017/S0007123410000451

Schulte-Cloos, J. (2022). Political potentials, deep-seated nativism and the success of the German AfD. Front. Pol. Sci. 3, 1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.698085

Shah, D. V., Cho, J., Eveland, W. P., and Kwak, N. (2016). Information and expression in a digital age. Communic. Res. 32, 531–565. doi: 10.1177/0093650205279209

Sibley, C. G., Duckitt, J., Bergh, R., Osborne, D., Perry, R., Asbrock, F., et al. (2013). A dual process model of attitudes towards immigration: person × residential area effects in a national sample. Polit. Psychol. 34, 553–572. doi: 10.1111/pops.12009

Stoeckel, F., and Ceka, B. (2022). Political tolerance in Europe: the role of conspiratorial thinking and cosmopolitanism. Eur. J. Pol. Res. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12527

Stouffer, S. A. (1955). Communism, Conformity, and Civil Liberties: A Cross-Section of the Nation Speaks Its Mind. Garden City, NY: The Country Life Press.

Sullivan, J. L., Marcus, G. E., Feldman, S., and Piereson, J. E. (1981). The sources of political tolerance: a multivariate analysis. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 75, 92–106. doi: 10.2307/1962161

Sullivan, J. L., Piereson, J., and Marcus, G. E. (1993). Political Tolerance and American Democracy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. (1986). “The social identity theory of intergroup behavior,” in Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds S. Worchel and L. W. Austin (Chicago: NelsonHall), 7–24.

Theocharis, Y., Barber,á, P., Fazekas, Z., and Popa, S. A. (2020). The dynamics of political incivility on Twitter. Sage Open 10, 2158244020919447. doi: 10.1177/2158244020919447

Vaillancourt, T., Faris, R., and Mishna, F. (2017). Cyberbullying in children and youth: Implications for health and clinical practice. Can. J. Psychiatry 62, 368–373. doi: 10.1177/0706743716684791

Van der Vegt, I., Mozes, M., Gill, P., and Kleinberg, B. (2021). Online influence, offline violence: language use on YouTube surrounding the ‘Unite the Right' rally. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 4, 333–354. doi: 10.1007/s42001-020-00080-x

Verkuyten, M., and Yogeeswaran, K. (2017). The social psychology of intergroup toleration. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 21, 72–96. doi: 10.1177/1088868316640974

Wagner, M. (2021). Affective polarization in multiparty systems. Elect. Stud. 69, 102199. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102199

Waldner, D., and Lust, E. (2018). Unwelcome change: coming to terms with democratic backsliding. Ann. Rev. Pol. Sci. 21, 93–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-050517-114628

Wenzel, M., Mummendey, A., and Waldzus, S. (2008). Superordinate identities and intergroup conflict: the ingroup projection model. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 18, 331–372. doi: 10.1080/10463280701728302

Keywords: political tolerance, civil liberties and rights, extremism, violence, ideology, survey experiment, Germany, public opinion

Citation: Trüdinger E-M and Ziller C (2023) Setting limits to tolerance: An experimental investigation of individual reactions to extremism and violence. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1000511. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1000511

Received: 22 July 2022; Accepted: 27 February 2023;

Published: 28 March 2023.

Edited by:

Alexia Katsanidou, GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, GermanyReviewed by:

Petar Bankov, University of Glasgow, United KingdomCopyright © 2023 Trüdinger and Ziller. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eva-Maria Trüdinger, ZXZhLW1hcmlhLnRydWVkaW5nZXJAc293aS51bmktc3R1dHRnYXJ0LmRl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.