94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 30 November 2022

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.984238

This article is part of the Research TopicAffective Polarisation in Comparative PerspectiveView all 9 articles

While scholars increasingly link affective polarization to the rise of populist parties, existing empirical studies are limited to the effects of radical right parties, without considering the possible effects of leftist populist parties or of parties' varying degrees of populism. Analyzing novel survey data across eight European publics, we analyze whether citizens' affective party evaluations broadly map onto these parties' varying degrees of populism, along with their Left-Right ideologies. We scale survey respondents' party feeling thermometer evaluations and social distance ratings of rival partisans using multidimensional scaling (MDS) to estimate a two-dimensional affective partisan space for each mass public, finding that in most (though not all) publics our mappings are strongly related to the parties' varying degrees of populism, as well as to Left-Right ideology. We substantiate these conclusions via analyses regressing respondents' affective ratings against exogenous measures of the parties' Left-Right ideologies and their degrees of populism. Our findings suggest that in many European publics, populism structures citizens' affective ratings of parties (and of their supporters) to roughly the same degree as Left-Right ideology.

Concerns over citizens' dislike, distrust, and contempt toward partisan opponents, i.e., affective polarization, have intensified in recent years. While the canonical affective polarization studies pertain to the American public (Lelkes and Westwood, 2017; Iyengar et al., 2019), a growing comparative literature extends this perspective outside the United States (see, e.g., Reiljan, 2020; Boxell et al., 2020; Gidron et al., 2020, 2022; Harteveld, 2021; Wagner, 2021; Adams et al., 2022; Horne et al., 2022).

Scholars link intensifying affective polarization to the rise of populist parties, with special emphasis on radical right populists. Populism, with its Manichean distinction between the pure people and the corrupt elites (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017), “appeals to a range of primarily negative emotions, such as anger, indignation, and resentment” (Betz, 2020). Established, mainstream parties often accuse populist radical right parties of promoting anger and division (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018). Indeed, studies find that populist radical right parties provoke far stronger dislike from political opponents than can be explained by policy considerations alone (Harteveld, 2021; Harteveld et al., 2021; Gidron et al., 2022), suggesting that populists' anti-system viewpoints and rhetoric provoke hostility independently of their policy stances. Yet studies linking affective polarization and populism focus exclusively on populist radical right parties, defined dichotomously, and thus do not address the effects of leftist populist parties, nor of variations in different parties' degrees of populism.

Synthesizing literature on affective polarization and electoral politics, we ask the questions: Across European publics, do citizens' affective party evaluations broadly coincide with our qualitative understanding of these parties' varying degrees of populism, along with their Left-Right ideologies? And how strongly does populism structure the “affective partisan space” in each public, relative to the Left-Right dimension?

To answer these questions, we analyze novel survey data from nine European countries: France, Germany, Greece, Italy, The Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. These surveys include the party feeling thermometer question, widely used in the polarization literature to capture partisan affect (in Supplementary material we present analyses with an alternative measure of partisan affect—preference for out-partisan social distance—that produces substantively similar findings). We apply non-metric multi-dimensional scaling to estimate an affective partisan space for each mass public in our study, i.e., a space that displays the affective distances between different partisan constituencies, and we qualitatively discuss whether the affective spaces we estimate reflect shared understandings of parties' populist orientations. Next, we analyze exogenous measures of parties' Left-Right ideologies from the Manifesto Project Database (Volkens et al., 2021) and their degree of populism from the Populism and Political Parties Expert Survey (POPPA; Meijers and Zaslove, 2021) to predict respondents' thermometer-based party ratings.

We find that in most of the publics we study, our affective partisan spatial mappings are strongly related to parties' Left-Right positions and to their varying degrees of populism. In every public in our study, one of the primary affective dimensions we uncover relates to the parties' Left-Right positions. And nearly every public features a second affective dimension that appears related to populism, with the exceptions of Britain which (at the time of our data collection) lacks major populist parties, and Spain where the dimensionality of the political space is less clear due to regional cleavages centered on Catalan and Basque nationalist identities. We conclude that party populism significantly drives citizens' affective party evaluations across many European publics, to a degree that is comparable to the Left-Right policy debates that have structured party competition across postwar democracies.

There is good reason to expect populism to provoke anger and distrust across party lines. While strictly programmatic parties tend to define political competition over policy positions and priorities, populist parties instead explicitly bifurcate society into the (good) people and the (corrupted) elite. Populist parties claim to speak for the people and to fight against the elite, who are portrayed as consciously working against ordinary peoples' interests (Bonikowski and Gidron, 2016). Thus, populist politics builds upon, and in turn feeds, negative emotions such as anger, anxiety, and hate. Leading scholars of populism have noted that anger is “an ideal motivating factor for populist mobilization” (Betz and Oswald, 2021, p. 122). In a series of multi-country experiments, Marx (2020) finds that anti-elite populist discourse provokes negative emotions when discussing pocketbook issues. If these emotions spill over into the partisan arena, they should intensify affective polarization.

Research on contemporary Western politics identifies a populist-vs-technocratic cleavage that is distinct from the Left-Right ideological dimension (Moffitt, 2018; Stavrakakis et al., 2018). For example, Zanotti (2021) traces the Italian party system's collapse and the emergence of populist alternatives such as Lega Nord and the Five Star Movement (which is particularly difficult to place on a traditional left-right scale), which has generated a competitive dynamic centering on populism. This party system is (at the time of our data collection) structured by Lega Nord and the Five Star Movement who constitute the populist, anti-elite wing vs. the more technocratic/anti-populist politics offered by the Democratic Party (Zanotti, 2021). A similar pattern exists in France, where the once hegemonic mainstream parties have become increasingly irrelevant, and elections feature a cleavage between the technocratic style of incumbent President Emmanuel Macron's En Marche party and two distinct populist alternatives: the radical right, culturally conservative populist National Rally Party and the left-leaning, culturally liberal, populist party France Unbowed. Even in countries where mainstream parties retain a large following, such as Germany, populist parties and movements have achieved electoral gains on both the left and the right (Arzheimer, 2015; Arzheimer and Berning, 2019; Rama et al., 2021; Torcal and Comellas, 2022). The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic has provoked “conflict extension” (Layman and Carsey, 2002) in many publics that relate to populist viewpoints, with populist parties opposing government mask and vaccine mandates, in line with populists' skepticism about public health experts' recommendations. In this regard, German protesters' attempt to storm the national parliament building in August 2020 was an outgrowth of a public demonstration—heavily attended by supporters of the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) party—against the government's pandemic restrictions.

While the populist cleavage appears increasingly salient across Europe, we know little about how it structures citizens' affect toward political parties. Empirical studies find that radical right populist parties are disliked far more intensely than can be explained by their policy positions on the Left-Right scale (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018), even when accounting for these parties' extreme positions on cultural issues pertaining to immigration and national identity (Harteveld, 2021; Gidron et al., 2022). Such findings validate populist partisans' sense that they are outsiders with low social status (Gidron and Hall, 2017, 2020). However, these studies focus exclusively on radical right populist parties, defined dichotomously.

We extend studies on the affective implications of populism to consider populists of both the left and the right, along with parties displaying varying degrees of populist characteristics. In light of previous findings, we expect a party's degree of populism to structure its partisans' feelings toward other parties in the system, independently of parties' Left-Right ideologies (Bertsou and Caramani, 2022). For example, supporters of the populist-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Germany might be expected to dislike the Christian Democratic and the Social Democratic parties based on these mainstream parties‘ support for the political system, but AfD partisans may feel more warmly toward the more populist, anti-system Die Linke, even though in comparison to the AfD, Die Linke espouses more leftist economic policies and more liberal cultural positions. Moreover, supporters of mainstream, pro-system parties may reciprocally despise populist parties of both the left and the right that challenge the political order, while more warmly evaluating other mainstream parties, even those that espouse sharply different Left-Right positions. Importantly, we do not argue that this populism dimension has replaced the traditional left-right cleavage in structuring cross-party affect. Instead, we expect that some citizens heavily weight populism, that others primarily consider Left-Right ideology, and that other citizens significantly weight both dimensions.

We analyze data from a novel dataset, collected by the survey firm Latana in the summer of 2021 via online surveys in the United States, Sweden, Poland, the Netherlands, Italy, Greece, the United Kingdom, France, Spain, and Germany.1 Because our multidimensional scaling analysis of the affective partisan space in each public requires more than two parties, we drop the United States from these analyses. Our case selection covers countries across Eastern, Western, Northern and Southern Europe, and also displays variations in the proportionality of countries' electoral systems and in their democratic histories. Moreover, our survey covers political systems in which there are populist parties on both the right and the left. Based on previous research, our case selection includes countries with comparatively high levels of affective polarization, Spain and Greece, along with countries with comparatively low affective polarization levels, notably the Netherlands and Sweden (Reiljan, 2020; Wagner, 2021).

Latana sampled roughly 1,000 respondents per country, balanced on current population distributions with weights on age, gender and rural-urban residential environment. Respondents were asked to rate their affect toward parties using the feeling thermometer question: “Please rate how you feel toward the following party on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 being the most unfavorable rating and 10 being the most favorable rating.” This is the most common survey-based measure of partisan affect in affective polarization research (Iyengar et al., 2019; Reiljan, 2020). Supplementary Tables 2, 3 list the set of parties survey respondents were asked to evaluate in each country, along with descriptive statistics and democratic breakdowns of the survey respondents' gender, age, education, rural-urban residence, and partisanship.

We leverage individuals' party feeling thermometer ratings to recover a multidimensional affective space. Specifically, we apply non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) to take advantage of our data structure. Political scientists have applied MDS to a range of data including feeling thermometers and roll-call voting in the United States Congress (Weisberg and Rusk, 1970; Hoadley, 1980). MDS has been effective in recovering dimensional representations of concepts resulting from said data, primarily ideological spaces. Importantly, MDS can recover additional dimensions beyond ideology when analyzing feeling thermometers. For example, Weisberg and Rusk (1970) find a “recent-issue” dimension that crosscuts the standard (economic) Left-Right ideology dimension, that, in the 1960's, constituted positions on issues such as the Vietnam War, civil rights, and urban unrest. While MDS has been applied to many measures in American politics, including feeling thermometers, to our knowledge it has not yet been used with cross-country party-level feeling thermometer ratings. Furthermore, MDS has not been applied to study the dimensionality of partisan affect.

For technically-interested readers, the following two paragraphs provide details of the non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) procedure (other readers may skip this material, and continue reading at the paragraph beginning “Intuitively, MDS takes the…”). To analyze our data, we use survey respondents' party thermometer ratings, denoted D, by taking the correlation of every respondent's party feeling thermometer responses to each party stimulus in their country. This generates a similarity matrix S (bounded between [−1, 1]). We then subtract the matrix S from 1, and divide S by its resulting maximum value

to bound the matrix between [0, 1] resulting in dissimilarity matrix D. The resulting matrices, Dc are size pc × pc where p is the number of parties and the subscript c denotes the country.

Using these recovered dissimilarity matrices of parties in each country, non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) estimates δjm = f(djm) where δ is the observed dissimilarity of party j and party m and d represents the distance between parties j and m in the low-dimensional representation of the data. MDS generates party locations in this space by minimizing a badness-of-fit measure called stress:

This iteration of stress is calculated by dividing the raw stress by the sum of squared observed similarities (δjm). In general, higher stress values imply worse configurations, in terms of fit, of points in the low-dimensional space. As a rule of thumb, 0.2 is used as a threshold for poor solutions, while the best solutions approach zero. All our MDS stress values approach zero for each public in our study, with our largest value being 0.005, implying that our two-dimensional solution captures the dynamics contained in our data.

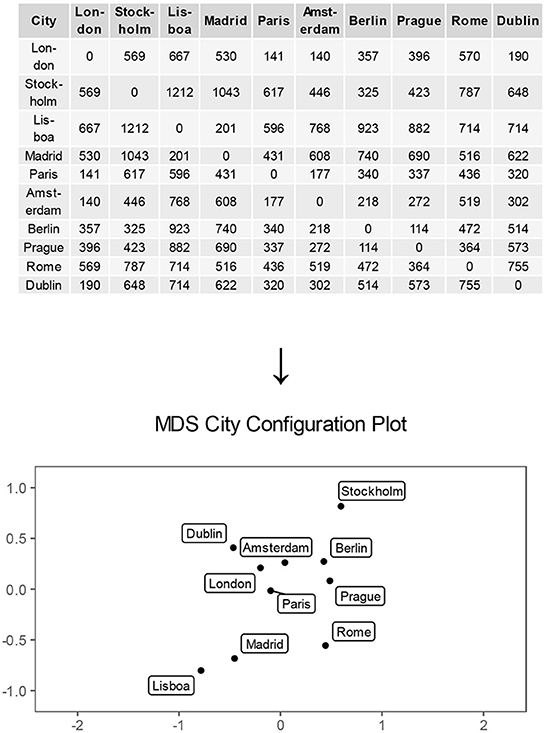

Intuitively, MDS takes the complex, numerically observed dissimilarities of a given set of objects or stimuli and maps those differences onto a simplified, low-dimensional space. The geometric distance between points in the space recovered by MDS is a lower-dimensional representation of the mathematical dissimilarities between those stimuli. An example of this method comes from Borg and Groenen (2005), where the authors use the flight distances between European cities as a dissimilarity matrix: the further the distance between two cities, the higher their “dissimilarity.” While this matrix comprises complex, numerical distances between cities, using a two-dimensional MDS on this data generates a highly accurate reconstruction of a map of Europe, reproduced below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Example of the use of non-metric scaling to represent distances in a two-dimensional space. The top panel in the figure displaces a matrix of the flight distances (in miles) between different European cities. The bottom panel applies non-metric multi-dimension scaling (MDS) to represent the “spatial dissimilarity” between these different cities, based on this flight distance matrix. The recovered dimensional space captures the geographic locations of these cities. Analogously, when applying MDS to our data on party affect, we recover a two-dimensional space that reflects how individuals affectively evaluate the parties in their system.

The non-metric dimensional scaling (MDS) results that we present display parties' estimated locations in our recovered two-dimensional space. Each party has a recovered x (Dimension 1) and y (Dimension 2) coordinate. The configuration of these points reveals how the survey respondents who provided the party thermometer ratings we analyze conceive of and affectively evaluate parties. Specifically, the greater the distance between any two parties in the space, the stronger the tendencies of those respondents who rated one party warmly to rate the spatially distant party coldly, and vice versa. Given the low stress values (again, a general goodness of fit measure for MDS analysis) from our MDS results, we are confident that individuals conceive of these parties as existing in a two-dimensional space.

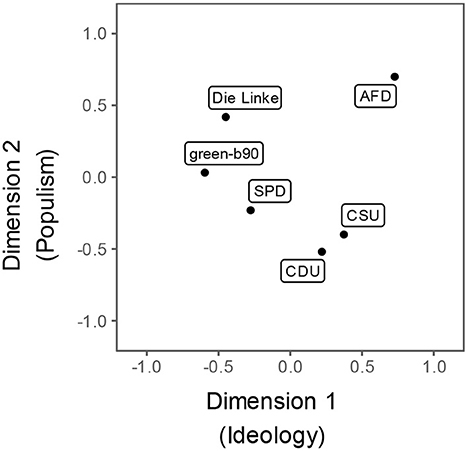

Figure 2 displays the two-dimensional affective partisan space we generated for the German party system, using survey respondents' party thermometer ratings. The parties are the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), a large, mainstream, center right party, and its sister party the Christian Social Union (CSU) from the state of Bavaria; the Social Democratic Party (SPD), a large, mainstream center-left party; the Greens, a smaller ecological party; Die Linke, a smaller party with a leftist economic program and liberal cultural positions whose support base is in the states of the former East Germany, and that displays populist attributes; and Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), a radical right and intensely populist party.2

Figure 2. Affective spatial mapping of the German party system. The figure displays non-metric multi-dimensional spatial mappings of Germany's affective partisan space, based on respondents' party thermometer ratings from a survey administered in the summer of 2021. The party acronyms in the figure are spelled out in the text. The wording of the survey items is given in the text. The labels “Ideology” for Dimension 1 and ”Populism” for Dimension 2 refer to qualitative interpretations of these dimensions, which are discussed in the text.

As discussed above, the parties‘ relative placementes in Figure 2 represent distances in the affective space. These placements indicate that survey respondents who expressed warmer (colder) feelings toward the AfD tended to express colder (warmer) feelings toward most of the other parties in the system, and vice versa—i.e., the AfD is located far away from all other parties in the two-dimensional space. The SPD is located near to the Greens and relatively near the CDU and CSU which are extremely proximate in the affective space which reflects the CSU's status as a “sister” party to the CDU, with largely overlapping policy positions.

Two key patterns emerge from the affective partisan mapping for Germany. First, this two-dimensional space appears to map reasonably well onto the Left-Right and populist dimensions. The horizontal dimension maps the parties with the Greens and Die Linke at the left pole, followed by the center-left SPD. The CDU and CSU are positioned between the SPD and the AfD at the right pole, which is consistent with our shared understanding of these parties' relative Left-Right ideologies.3 On the vertical axis the strongly populist AfD and the moderately populist Die Linke are positioned near one pole, while the mainstream SPD and CDU/CSU are positioned at the other pole. Second, the German parties' positions are roughly as dispersed on the vertical dimension that appears to capture populism, as they are on the horizontal dimension that is broadly consistent with Left-Right ideology. Qualitatively, this implies that German citizens' affective orientations toward different parties are significantly related to both the parties' ideological positions and to their relative degrees of populism.

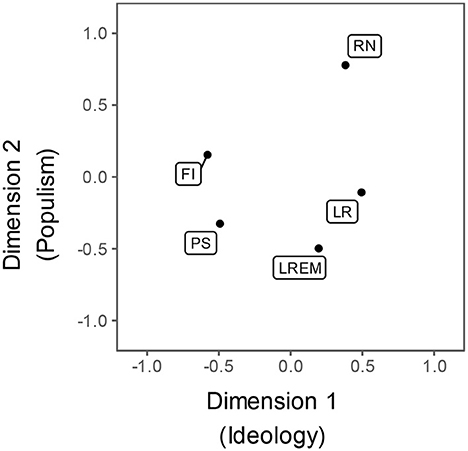

Figure 3 displays the affective partisan space we generated for the French party system. The parties displayed are the National Rally (RN), the strongly populist, culturally conservative (though economically more ambiguously positioned) party led by Marine Le Pen; France Unbowed (FI), a populist party with a radically left-wing economic agenda combined with liberal cultural positions, led by Jean-Luc Melenchon; Republic Forward (LREM), Emmanuel Macron's technocratic party of the economic center-right; The Republicans (LR), a mainstream party with conservative economic positions, and the economically leftist Socialist Party (PS).

Figure 3. Affective spatial mapping of the French party system. The figure displays non-metric multi-dimensional spatial mappings of France's affective partisan space, based on respondents' party thermometer ratings from a survey administered in the summer of 2021. The acronyms in the figure designate the following parties: The National Rally (RN), The Republicans (LR), Republic Forward (LREM), The Socialists (PS), and France Unbowed (FI). The wording of the survey items is given in the text. The labels “Ideology” for Dimension 1 and ”Populism” for Dimension 2 refer to qualitative interpretations of these dimensions, which are discussed in the text.

Figure 3 displays the National Rally (RN) located far from the other parties in the affective space, denoting that respondents who warmly (coldly) evaluated the RN tended to coldly (warmly) evaluate the other parties, and vice versa. The horizontal dimension maps the economically leftist parties, the Socialists and France Unbowed (FI), at one pole, while the economically conservative Republican Party (LR) anchors the other pole. While the National Rally (RN) is typically labeled a radical right party, it occupies a position near the Republicans on the horizontal dimension which plausibly reflects the RN's mixture of very conservative cultural positions and more moderate economic positions. The parties' relative positions on the vertical axis are related to their degrees of populism: The strongly populist National Rally anchors one pole of this axis, while Emmanuel Macron's technocratic Republic Forward party (LREM) anchors the other pole. Note, moreover, that France Unbowed (FI)—a party with some populist characteristics, though not to the same degree as the National Rally (RN)—is mapped as the most proximate party to the FN along this vertical axis, suggesting that these two parties' embrace of populism, relative to the other parties, leads some respondents to rate these two ideologically quite distinctive parties similarly. At the same time the spatial mapping displays a large distance between the National Rally and France Unbowed, plausibly stemming from these parties' clashing positions on cultural issues which are a major component of the Left-Right dimension. This illustrates that while shared populist orientations can warm cross-party affective evaluations, affect in France is also significantly structured by parties' Left-Right positions. Finally, as with the affective partisan mapping for Germany, the French mapping shows the parties' positions roughly as dispersed on the vertical dimension as on the horizontal dimension, suggesting that French citizens' party affect is significantly related both to the parties' Left-Right positions and to their relative degrees of populism.

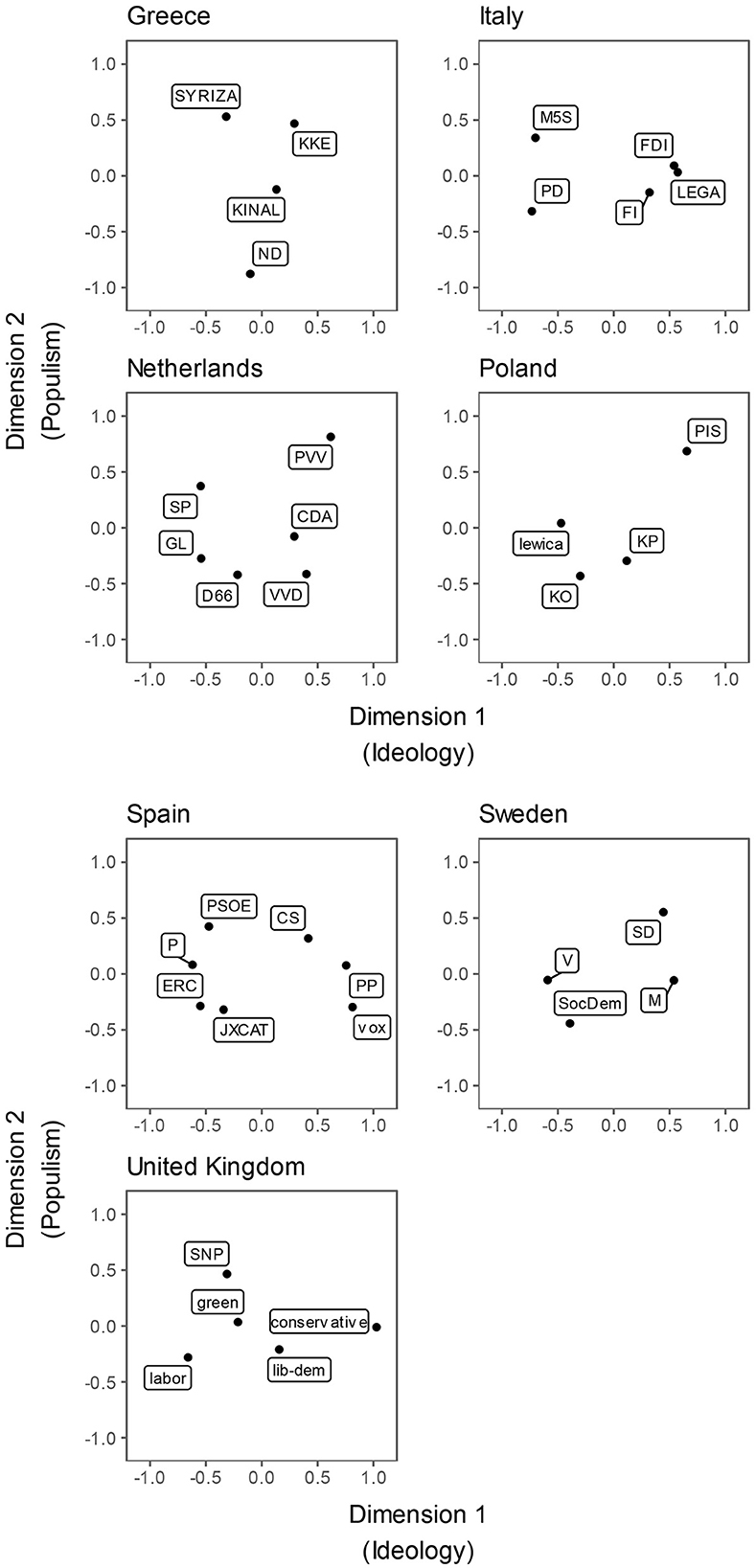

Figure 4 displays the affective partisan mappings for the other seven mass publics in our study: Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. For all seven of these publics, the horizontal dimension of the affective space appears to tap Left-Right ideology, while in five of the seven publics—Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Sweden—the vertical axis appears to tap a populist dimension. With respect to these affective spaces and populism, in Italy the vertical axis places the populist parties The Northern League (LEGA), the Five Star Movement (M5S), and Forza Italia (FI) at one pole, and the mainstream, technocratic Democratic Party (PD) at the other pole. In Greece, the vertical axis places the populist parties Syriza and the Communist Party (KKE) at one pole, and the mainstream New Democracy (ND) at the other pole. In the Netherlands, the populist radical right Party for Freedom (PVV) anchors one pole of the vertical axis, while the mainstream Liberals (VVD), the Democrats 66 (D66), and the Christian Democrats (CDA) are located near the other pole. In Poland, the populist Law and Justice (PiS) is distinct from all other parties in the system on the vertical dimension while the horizontal dimension captures the parties' relative left-right position. In general, this structure seems representative of the party structure in Poland (Pytlas, 2021), with PiS being distinctly further right-wing and populist than their counterparts. Finally, in Sweden one pole of the vertical axis is anchored by the populist, radical right Sweden Democrats (SD), while the mainstream Social Democrats (SocDem) are at the other pole.

Figure 4. Affective spatial mappings for Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The figure displays non-metric multi-dimensional spatial mappings of the affective partisan spaces for Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, based on survey items eliciting respondents' party thermometer ratings from a survey administered in the summer of 2021. The acronyms in each panel denote political parties whose names are spelled out in the text. The wording of the survey items is given in the text. The labels “Ideology” for Dimension 1 and ”Populism” for Dimension 2 refer to qualitative interpretations of these dimensions, which are explained in the text. Note, however, that—as discussed in the text—the qualitative interpretation of populism for Dimension 2 does not apply to the mappings of the Spanish and British publics.

By contrast, the affective partisan mappings for Spain and the UK do not display relative party positions that clearly capture a populist dimension. For Spain, the first (horizontal) dimension is clearly Left-Right ideology, anchored by the right-wing Vox and Popular Party (PP) at one pole, and the left-wing Podemos (PSOE) near the other. However, the substantive interpretation of the vertical dimension is unclear. Both Catalan parties, the Republican Left (ERC) and Together for Catalonia (JXCAT) cluster at the bottom of the vertical axis while the mainstream, anti-independence parties cluster higher in this axis. However, Vox, a populist right party, is placed near the Catalan parties on the vertical axis which suggests that this dimension is neither clearly populist nor clearly nationalist. The lack of a populist affective dimension in Spain may thus in part be due to the choice of political parties included in the survey, which structure affect around the highly salient question of Catalan independence. In the UK, the horizontal dimension clearly captures Left-Right ideology with the left anchored by Labor and the Green Party, with the Scottish National Party (SNP) and Liberal Democrats (Lib-dem) toward the middle, and the Conservatives on the right. However, none of the UK's political parties are strongly populist.4 Prior to the Brexit referendum, when both the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) and the Brexit Party were electorally relevant, we may have detected a populist dimension structuring affect in the UK. Yet, support for both of these parties collapsed after the success of the Brexit referendum and the UK's exit from the European Union.

Overall, the mappings of the nine mass publics we analyze suggest that the affective partisan space is invariably structured by a Left-Right ideological dimension, and is usually—but not always—structured by a second dimension strongly related to populism.

To further substantiate our conclusions we conduct pooled data analyses using the survey data from the nine publics we study, in which we predict each partisan constituency x's mean thermometer rating of each out-party y in the system, relative to the constituency's mean rating of their own party (the in-party).5 We label this variable [Difference between party x's supporters' thermometer ratings of party x vs. party y]. For instance, the German survey respondents who reported that they supported the Green Party awarded their own party a mean thermometer rating of 7.83 while awarding the Social Democratic party (SDP) a mean thermometer rating of 5.54, a difference of 2.29 units on the 0–10 thermometer scale.

We predict the thermometer score differences as a function of the Left-Right distance between the parties x, y, along with the difference between each party's degree of populism. Our measure of Left-Right party differences relies on the Comparative Manifesto Project codings of the left-right tones of the parties' manifestos (i.e., the RILE scores), for the most recent national parliamentary election for which these codings were available. The parties' degrees of populism were measured using the Populism and Political Parties Expert Survey (POPPA) by Meijers and Zaslove (2021). This data set covers up to 250 political parties in 28 European countries that were represented in parliament in 2017/2018. The POPPA data are from a one-time expert survey administered in 2017–2018, and we assume that parties' degrees of populism did not change between this time and the summer 2021 period of our survey. As discussed in Meijers and Zaslove (2021), POPPA performs well in terms of accuracy, validity, and coverage. The information to define parties as populist is based on factor regression scores of four dimensions of populism and ranges between 0 (a party is not at all populist) and 10 (a party is very populist).6

We create our independent variables in a similar structure as our dependent variable, based on the party pair consisting of the in-party x and the out-party y: [Left-Right distance between parties x, y] is defined as the absolute difference between the CMP's Left-Right codings of the parties x and y based on their most recent election manifestos, and [Populism difference between parties x, y] is defined as the absolute difference between the populism scores for the parties x, y based on the POPPA data. We standardize these independent variables through centering and scaling to create comparable effect estimates for both the populism and ideological differences between the parties.

Overall, our data structure results in 200 unique datapoints comprised of each in-party x's average thermometer rating of their own party subtracted from the rating of the given out-party y. For example, the datapoints for Germany are presented below in Table 1. The top row displays the variable values for the party pair consisting of the CSU, the [in-party (x)] and its sister party the CDU, the [out-party (y)]. Here the three columns under the header [in-party (x) – out-party (y)] are calculated by taking the difference between the in-party x's average value and the out-party y's average value. Specifically, in the column labeled [Therm difference], the value of 1.114 in the top row denotes that the CSU's partisans assigned thermometer scores to their in-party that were, on average, 1.114 units higher than those they assigned to their sister party, the CDU. The value in the column labeled [POPPA distance], −0.359, denotes that the difference between the populism scores for the CSU and the CDU was 0.359 standard deviations below the mean value in our data set. And the value in the column labeled [RILE distance], −1.424, denotes that the Left-Right distance between the CSU and the CDU was 1.424 standard deviations below the mean value in our data set.

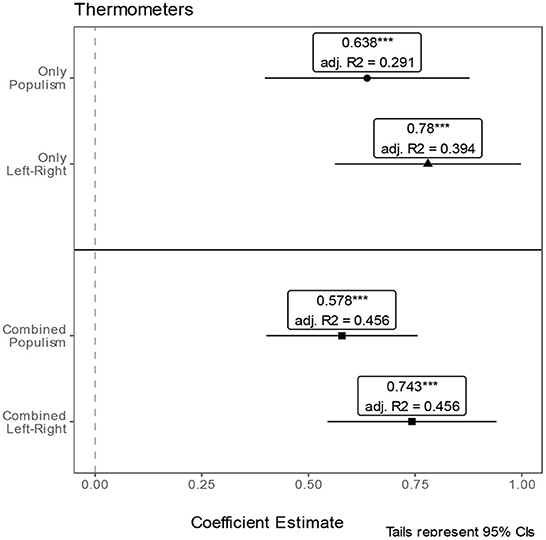

Using this data for all countries, we regress the average difference in the partisan constituency's in-party-vs-out-party thermometer ratings on our independent variables using country-level fixed-effects and country-clustered standard errors. We estimated three models: a univariate model where the key independent variable (IV) was the party populism difference; a model where the key IV was the party ideology difference; and a model that incorporated both IVs simultaneously. Figure 5 displays these regression results (see Supplementary Table 1 for further details of these analyses).7 In all three of our models, differences in parties' Left-Right ideologies and in their degrees of populism strongly predict differences in affective party evaluations. The standardized regression coefficients suggest that the magnitudes of the effects associated with populism are comparable to those associated with ideology.

Figure 5. Predicting differences in partisan constituencies' in-party vs. out-party ratings based on party differences with respect to Left-Right ideology and populism. The figure reports analyses where the dependent variable was the difference between a given partisan constituency's mean thermometer rating of its in-party x vs. its mean thermometer rating of a focal out-party y. The independent variables are defined in the text. See Supplementary Table 1 for further details of these analyses. Also see Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 4 for the same analyses using weighted difference in means. *** denotes statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level.

As discussed above, our measure of partisan affect is the party feeling thermometer—the most common variable in the affective polarization literature. Recent critics have pointed out, however, that this measure is oriented toward out-party affect, while what scholars may actually care about is out-partisan affect (Iyengar et al., 2019). That is, we may be more normatively concerned by citizens disliking—and possibly discriminating against—fellow citizens because of partisan disagreements, than about citizens disliking opposing parties. To address this issue, our survey included an additional measure of partisan affect, one that captures affect toward out-partisans using a social distance scale (Bogardus, 1933). We used the question: “Please indicate the closest relationship you would be comfortable having with voters of the following party.” Respondents were then presented with the following options, in declining levels of social proximity: “close family, friend, neighbor, co-worker, citizen of your country, tourist, or none of the above.” Preferences for greater social distance on this scale have been shown to correlate with discriminatory behavior in economic decision-making games (Enos and Gidron, 2018).

We estimated models that were similar to those described above, but this time using the preference for social distance variable as our dependent variable. We first generated figures that were comparable to the spatial mapping of partisan affect presented above (see Supplementary Figures 1, 2), and the results were substantively similar. We then regressed this social distance measure of partisan effect on the Left-Right distance and populism distance variables, and the results were substantively similar to those presented in Figure 5 above. For more information on these analyses, please see Supplementary Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 1 and see Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 4 for the same analyses using weighted difference in means.

To summarize these robustness checks, in every mass public the affective partisan mappings we estimate from survey respondents' party thermometer ratings are strikingly similar to the mappings generated from respondents' social distance ratings of out-partisans (cf., Druckman and Levendusky, 2019). Hence our substantive conclusions do not depend on any single measure of political affect. This similarity suggests that prior comparative findings on the correlates of affective polarization, nearly all of which analyze respondents' party thermometer ratings (e.g., Boxell et al., 2020; Gidron et al., 2020; Reiljan, 2020; Harteveld, 2021; Wagner, 2021), are not an artifact of this thermometer item. In fact, survey respondents' party thermometer ratings and their social distance ratings of out-partisans appear closely related.

While scholars increasingly link intensifying affective polarization in mass publics to the rise of populist parties, existing empirical studies are limited to the effects of radical right parties, without consideration of the possible effects of leftist populist parties or of parties' varying degrees of populism. Analyzing novel survey data across nine European publics—France, Germany, Greece, Italy, The Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom—we analyze whether citizens' affective evaluations of competing parties broadly map onto these parties' varying degrees of populism, along with parties' Left-Right ideological differences which have been shown to strongly influence cross-party affect.

Applying non-metric multi-dimensional scaling to respondents' affective party ratings, we estimate a two-dimensional affective partisan space for each mass public in our study, finding that in most (though not all) publics our affective spatial mappings are strongly related to the parties' varying degrees of populism, as well as to the parties' differing Left-Right positions. We substantiate these conclusions via analyses regressing survey respondents' affective party ratings against exogenous measures of the parties' Left-Right ideologies and their degrees of populism. These regressions suggest that, on average, populism structures citizens' affective ratings of political parties to a degree that is comparable to the affective consequences of Left-Right ideology. Thus, cross-party differences relating to populism are important for explaining affective polarization across European publics. We substantiate these conclusions via robustness checks in which our dependent variable is a measure of the respondent's preferred social distance from a focal out-party's supporters.

Our findings raise several promising directions for future research. For instance, it would be interesting to examine heterogeneity in the role of the two partisan traits we study—Left-Right and degree of populism—in shaping affective evaluations. That is, which citizens typically place more weight on ideology when affectively evaluating parties, and which ones prioritize populism? In addition, we might analyze whether populist parties' governing status mediates citizens' affective reactions to their populist characteristics; whether the affective consequences of populism are different for citizens with varying degrees of political engagement; and, whether the salience of cultural debates over issues such as immigration, governmental covid-19 restrictions, and traditional morality mediate the public's reactions to parties' populism characteristics.

Data and replication code is available on Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/MN4RAR).

NG, WH, and JA designed and administered the survey. SF performed the statistical analyses and generated all figures. All authors contributed to the write-up. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The survey used in this paper was funded by Israel Science Foundation grant (1806/19).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.984238/full#supplementary-material

1. ^For data collection assistance we thank Arvid Lindh, Eelco Harteveld, Alexandra Jabbour, David Weisstanner, Volha Charnysh, Chiara Superti, and Luis Miller.

2. ^Due to space limitations in our survey we did not ask respondents to affectively rate the Free Democratic Party (FDP), a small, mainstream party that is economically conservative but culturally liberal.

3. ^While the proximity of the SPD and CDU-CSU may seem surprising given that they are on different sides of the Left-Right divide, these parties had been in a long-term “grand coalition” government for 12 of the past 16 years at the time of our summer 2021 survey, which had blurred their distinctive ideological positions.

4. ^Both Labour (with Jeremy Corbyn) and the Conservatives (with Boris Johnson) recently had leaders who flirted with populism. Yet, both parties score low on the POPPA populism scores described below, which are designed to measure parties' degrees of populism, and are also generally seen as mainstream, catch-all, parties.

5. ^To determine an individual's in-party, we used the party that the survey respondent reported they felt closest to. If a respondent did not indicate that they felt closest to any party, they were asked if there was a party that they felt somewhat close to, and this was used as their in-party. If a respondent did not feel somewhat close to any party then they were classified as non-partisans and excluded from our analyses.

6. ^Meijers and Zaslove (2021) employ a multi-dimensional concept of populism. Specifically, the four dimensions that the Populism Score comprises are: a Manichean discourse (parties see politics as a moral struggle between good and bad), the indivisibility of people (parties consider the ordinary people to be indivisible, i.e., homogeneous), the general will of the people (parties consider the ordinary people's interests to be singular), and centrism (parties believe that sovereignty should lie exclusively with the ordinary people).

7. ^We also conducted these analyses using individual-level weights calculated based on age, education, and gender, with tables and figures reported in the Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 4. The results are highly similar, and our substantive conclusions remain the same. We thank Thomas Tichelbaecker for creating and implementing the variable weighting.

Adams, J., Bracken, D., Gidron, N., Horne, W., O'brien, D. Z., and Senk, K. (2022). Can't we all just get along? How women MPs can ameliorate affective polarization in western publics. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2022, 1–7. doi: 10.1017/S0003055422000491

Arzheimer, K. (2015). The AfD: finally a successful right-wing populist Eurosceptic party for Germany? West Eur. Polit. 38, 535–556. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2015.1004230

Arzheimer, K., and Berning, C. C. (2019). How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and their voters veered to the radical right, 2013–2017. Electoral Stud. 60, 102040. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004

Bertsou, E., and Caramani, D. (2022). People haven't had enough of experts: technocratic attitudes among citizens in nine European democracies. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 66, 5–23. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12554

Betz, H. G. (2020). “The emotional underpinnings of radical right populist mobilization: explaining the protracted success of radical right-wing populist parties”. Carr Research Insight. (London: Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right), 6, Available online at: https://www.radicalrightanalysis.com/2020/06/05/carr-researchinsight-series-the-emotional-underpinnings-of-populist-radical-right-mobilization/.

Betz, H. G., and Oswald, M. (2021). “Emotional mobilization: the affective underpinnings of right-wing populist party support,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Populism, ed O. Michael (London: Palgrave McMillan), 7. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-80803-7_7

Bonikowski, B., and Gidron, N. (2016). The populist style in American politics: presidential campaign discourse, 1952–1996. Social Forces 94, 1593–1621. doi: 10.1093/sf/sov120

Borg, I., and Groenen, P. J. (2005). Modern Multidimensional Scaling: Theory and Applications. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Boxell, L., Gentzkow, M., and Shapiro, J. M. (2020). Cross-country trends in affective polarization. Rev. Econ. Statist. 2020, 1–60. doi: 10.3386/w26669

Druckman, J. N., and Levendusky, M. S. (2019). What do we measure when we measure affective polarization?. Pub. Opin. Q. 83, 114–122. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfz003

Enos, R. D., and Gidron, N. (2018). Exclusion and cooperation in diverse societies: Experimental evidence from Israel. Amer. Polit. Sci. Rev. 112, 742–757. doi: 10.1017/S0003055418000266

Gidron, N., Adams, J., and Horne, W. (2020). American Affective Polarization in Comparative Perspective (Elements in American Politics). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108914123

Gidron, N., Adams, J., and Horne, W. (2022). Who Dislikes Whom? Affective Polarization between Pairs of Parties in Western Democracies. British Journal of Political Science. Forthcoming. Available online at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-political-science/article/who-dislikes-whom-affective-polarization-between-pairs-of-parties-in-western-democracies/4AAAA9771D0F4B0FB6A395E727F5154F

Gidron, N., and Hall, P. A. (2017). The politics of social status: economic and cultural roots of the populist right. Br. J. Sociol. 68, S57–S84. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12319

Gidron, N., and Hall, P. A. (2020). Populism as a problem of social integration. Comparat. Polit. Stud. 53, 1027–1059. doi: 10.1177/0010414019879947

Harteveld, E. (2021). Ticking all the boxes? A comparative study of social sorting and affective polarization. Elect. Stud. 72, 102337. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102337

Harteveld, E., Mendoza, P., and Rooduijn, M. (2021). Affective polarization and the populist radical right: creating the hating? Govern. opposite. 2021, 1–25. doi: 10.1017/gov.2021.31

Hoadley, J. F. (1980). The emergence of political parties in Congress, 1789–1803. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 74, 757–779. doi: 10.2307/1958156

Horne, W., Adams, J., and Gidron, N. (2022). The way we were: how histories of co-governance alleviate partisan hostility. Comparat. Polit. Stud. 2022:10414022110019. doi: 10.1177/00104140221100197

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., and Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Layman, G. C., and Carsey, T. M. (2002). Party polarization and “conflict extension” in the American electorate. Amer. J. Polit. Sci. 786–802. doi: 10.2307/3088434

Lelkes, Y., and Westwood, S. J. (2017). The limits of partisan prejudice. J. Polit. 79, 485–501. doi: 10.1086/688223

Marx, P. (2020). Anti-elite politics and emotional reactions to socio-economic problems: experimental evidence on “pocketbook anger” from France, Germany, and the United States. Br. J. Sociol. 71, 608–624. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12750

Meijers, M. J., and Zaslove, A. (2021). Measuring populism in political parties: appraisal of a new approach. Comparat. Polit. Stud. 54, 372–407. doi: 10.1177/0010414020938081

Moffitt, B. (2018). The populism/anti-populism divide in Western Europe. Democrat. Theor. 5, 1–16. doi: 10.3167/dt.2018.050202

Mudde, C., and Kaltwasser, C. (2017). Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/actrade/9780190234874.001.0001

Mudde, C., and Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018). Studying populism in comparative perspective: reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda. Comparat. Polit. Stud. 51, 1667–1693. doi: 10.1177/0010414018789490

Pytlas, B. (2021). Party organization of PiS in Poland: between electoral rhetoric and absolutist practice. Polit. Govern. 9, 340–353. doi: 10.17645/pag.v9i4.4479

Rama, J., Zanotti, L., Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J., and Santana, A. V. O. X. (2021). The Rise of the Spanish Populist Radical Right. London: Routledge.

Reiljan, A. (2020). ‘Fear and loathing across party lines' (also) in Europe: Affective polarisation in European party systems. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 59, 376–396. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12351

Stavrakakis, Y., Katsambekis, G., Kioupkiolis, A., Nikisianis, N., and Siomos, T. (2018). Populism, anti-populism and crisis. Contempor. Polit. Theor. 17, 4–27. doi: 10.1057/s41296-017-0142-y

Torcal, M., and Comellas, J. M. (2022). Affective polarisation in times of political instability and conflict. Spain from a comparative perspective. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 2022, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2022.2044236

Volkens, A., Burst, T., Krause, W., Lehmann, P., Matthieß, T., Regel, S., et al. (2021). The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2021a. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

Wagner, M. (2021). Affective polarization in multiparty systems. Electoral Stud. 69, 102199. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102199

Weisberg, H. F., and Rusk, J. G. (1970). Dimensions of candidate evaluation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 64, 1167–1185. doi: 10.2307/1958364

Keywords: populism, ideology, parties, affective polarization, public opinion, dimensional scaling

Citation: Fuller S, Horne W, Adams J and Gidron N (2022) Populism and the affective partisan space in nine European publics: Evidence from a cross-national survey. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:984238. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.984238

Received: 01 July 2022; Accepted: 02 November 2022;

Published: 30 November 2022.

Edited by:

Mariano Torcal, Pompeu Fabra University, SpainReviewed by:

Noam Lupu, Vanderbilt University, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Fuller, Horne, Adams and Gidron. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: James Adams, amZhZGFtc0B1Y2RhdmlzLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.