- 1Italian National Research Council, Institute for Research on Population and Social Policies, Rome, Italy

- 2Department of Political Science, Luiss University, Rome, Italy

- 3Department of Enterprise Engineering, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy

In the Italian context, political and social participation in the urban dimension has experienced innovations to broaden the inclusion of citizens in public choices relating to citylife and to urban renovation. Participation found in the city a relevant space to experiment with innovation in the relationship between institutions and citizens, many initiatives advanced and developed over the years have had a powerful lever in technology: participatory budgets, consultations, public-private-non-profit partnerships. In other cases, specifically in peripheral realities, urban innovation has turned out to be detached from digital infrastructures and has benefited, rather, from the social infrastructures in the area. Civic committees, community foundations, collaboration agreements between citizens and authorities, and local community development experiences developed in peripheral contexts. Regenerating urban spaces is a political objective proposed with increasing emphasis by institutional bodies at the various levels of governance. Environmental, economic, social and urban planning intersect and overlap and often projects related to urban planning “on paper” prevail over issues related to urban communities “on territories”. Without adequate processes of participation and subjectivity of citizens living in urban contexts, no model of “urban renaissance” appears fully deployed, resulting in participatory processes that—at best—only allow for access logics in a neoliberal perspective. Through a qualitative methodology, the paper aims at presenting and investigating six case studies in major Italian cities (Rome, Naples, Milan, Turin, Florence, Reggio Calabria), in which democratic innovation and experimentation in civic engagement spread from the digital capital of citizens and the social organizations of the peripheral territory, with its specificities and its problems. In particular, the objective of the paper is to discuss and problematise the processes of participation involving and featuring vulnerable people within the reconfiguration of urban and digital spaces. Following Sutton and Kemp's approach, we consider the relationship between urban spaces and marginal communities as central to a one-to-one relationship, fostering processes of urban inclusion. Combining participatory processes in liminal marginalized communities with an institutional push toward holistic urban regeneration may develop opportunities for active citizenship, overcoming the neoliberal paradigm of the city.

The neoliberal framework

Although several commentators claim that neoliberalism is merely an evolution of classical liberalism, it is evident that it is driven by very different conceptual assumptions and economic practices. Meanwhile, it is not possible to reduce neoliberalism to a set of monetary economic policies based on logics of a substantial marketization of public life and the “commodification” of social relations. The pervasive capacity of neoliberalism is based on what Dardot and Laval (2010) call a global political rationality that has pervaded the logic of capital, making it the new norm of social organization. What Nancy Fraser has asserted for capitalism in general applies to neoliberal capitalism; it is an institutionalized social order that extends beyond relations of production. In other words, if neoliberalism is not just an economic system, it is not even an ideology (not in the Marxist perspective, at least); rather, it is, if anything, a kind of ideological narrative or, moreover, a social imaginary capable of institutionalizing social production in a broad sense.

Neoliberalism not only reproduces social inequalities but also above all feeds itself with the systemic crises that it produces—hence, its only (apparent) exit is the paradoxical re-proposal of its same recipes that caused this permanent state of crisis.

Many studies have highlighted the relationship between the processes of de-democratization (Brown, 2006) and the neoliberal perspective. At this level, the neoliberal imaginary also affects the public sphere, favoring its hyperfragmentation while promoting, simultaneously, a sort of single thought that tends to become hegemonic (Sorice, 2020a), making forms of resistance useless (because delegitimized). Individualism —typical of the liberal tradition—thus becomes a sort of empty container, transforming itself into what we could call “de- subjectivized individualism”. In this framework, the transformations of the public sphere— often significantly placed in the “crisis paradigm”—highlight the apparent contradiction between single thought and hyperfragmentation (connected to polarization processes), which in reality turn out to be the poles of the new transitional public sphere, which has recently been called the “post-public sphere” (Davis, 2019; Schlesinger, 2020; Sorice, 2020a).

Over the past two decades, new buzzwords have emerged that are mostly related to the value of governance and how it is applied. While the success of the concept of “governmentality” (both in the Foucultian interpretation and in those that link it to the rhetoric on depoliticised governance) has been an important step toward the affirmation of the new global rationality of neoliberalism, it has in fact promoted a hierarchy between governability and representation (to the advantage of the former) that undermines the liberal idea of democracy itself (Foucault, 1979; Fawcett et al., 2017). The concept of governmentality has progressively replaced that of governance; the latter has been perceived to be too closely linked to a medium- to long-term political project and is therefore considered intrinsically dysfunctional to the rhetoric of efficiency. Governmentality has thus become rooted in values typical of business, such as competition, self-interest, and the “necessity” of strong decentralization. The same narrative of individual empowerment (in the sense, however, of a de-subjectivized individual) is in fact resolved in a substantial devolution of power and in the progressive loss of the capacity of social actors to make proposals, especially those living in liminal spaces1.

The emphasis on governmentality has found fertile ground in other phenomena, from the processes of depoliticization (Flinders and Buller, 2016) to the development of approaches that can be variously framed in the area of New Public Management to the growing centrality of the concept of “governance” at the expense of that of “government”.

It is precisely the use and misuse of the “storytelling” of governance that has been a formidable narrative strategy of the new neoliberal rationality and in particular of the form of neoliberalism “with a human face”, an approach that we could connect—with some attention— to the concept of common-sense neoliberalism used by Stuart Hall at various moments in his reflections (Hall and O'Shea, 2013). This sociocultural framework includes both the public policies that are fundamentally based on a strong deregulation of the economy and an emphasis on the privatization processes of state enterprises; the latter has given rise to a spiral of the marketization of public life via the transformation of essential public goods into 'commodities' (water, for instance). Even the rhetoric on the light state has been progressively turned into a social narrative on a renewed presence of the State via an obvious process involving the neoliberalization of the latter, which has even become “heavy” in the context of securitarianist rhetoric and growing expenditure on military apparatus and armaments. This process, moreover, long predates the conflict resulting from Russia's invasion of Ukraine—which it has only emphasized—and has been widely discussed in the literature (Harvey, 2005; Sintomer, 2010).

This approach to the so-called neoliberalization of the state has also been accompanied by a considerable degree of suspicion toward the institutions of representative democracy (and the emphasis on “governability” has fostered this tendency). The following aspects of this perspective should be underscored: (a) rhetoric on “overcoming” party politics (judged “slow” and mostly ineffective); (b) emphasis on greater citizen participation in policy-making processes; and c) “efficiency” trends that find in the technocratic approach a formidable space for legitimization.

These aspects are also very relevant when referring to the relations between political participation and territorial governance. Indeed, it is precisely in certain participatory processes that the paternalist face of the state manifests its clearest features. It must be made clear, however, that the paternalist state of neoliberal rationality has nothing to do with social democratic paternalism, which is symbolically summarized by the image of public institutions that are capable of following, supporting, and even directing the entire life of social subjects. Neoliberal paternalism is anesthetizing and adopts as its discursive mode that of the single thought. The distinguishing features of neoliberalism with a human face are manifold and have been variously redefined over time as part of an ongoing transformation of the very logic of neoliberalism. They are forms of the social imaginary and appear to be underpinned by buzzwords that also express social narratives, i.e., expressions such as competition, meritocracy, human rights, personal enhancement, and state interventionism explain this social storytelling very well, in addition to the centrality of the communicative ecosystems that constitute both spaces of conflict and frames for the anaesthetization of conflict. Neoliberal rationality is also an important framework for revisiting the relationship between participation and community. At this level, in fact, there is an important element of social “cleavage”. Political participation, in fact, moves in the dimension of “commonality”; it is the logic of koinònein that defines citizenship and participatory processes themselves. In other words, one does not participate as a component of a community; rather, participation determines the existence of one's community (Dardot and Laval, 2010, 2015). The relationship between the “common” and participation can be interpreted in different ways according to the “productivity” dimension of Hardt and Negri (2010) and—in a slightly different way—of Rifkin (2014) to the liberal approach to the commons, well expressed by the work of Ostrom (2015). The former entail potentially producing a progressive marginalization of territorial experiences with the risk of insignificance precisely for participatory experiences in liminal spaces. The “liberal” theory of the commons, on the other hand, constitutes, very often and in spite of itself, a breeding ground for a neoliberal perspective on participation and civic engagement that often translates into procedures for legitimizing policy actions that are decided outside of any perspective of the effective participation of social subjects. Hence, the institutionalization of participation produces two outcomes: (a) the risk of the privatization of the commons and (b) the excessive centrality of process facilitators, who tend to become a veritable “technocracy” of participatory processes.

In this scenario, “commonality” represents a kind of resistance to antidemocratic trends if one uses the commons as a theoretical frame of reference and thus political principle.

The neoliberal scenario also decisively influences the dynamics of democratic innovation2. The components of democratic innovation can be traced to seven areas (Smith, 2009; Geissel and Joas, 2013): inclusiveness, institutionalization, popular control, social legitimation, transparency, efficiency, and transferability. These components present several problematic issues: What kind of inclusiveness is referred to? Is it connected with an idea of meaningful participation (Geissel and Joas, 2013), or is it limited to activating access dynamics? In institutionalization processes, are citizens beneficiaries of services provided, or do they also become protagonists in the construction of the public agenda? Is popular control delegated to specific organizations, or does it also involve forms of self-organization? When we talk about efficiency, do we refer only to the time variable (the time taken between the proposal and implementation of a policy) or are the dynamics of accountability also central? Is transparency a procedural variable, or does it also have an impact on participatory architectures? Do the dynamics of legitimation concern the recognition of political institutions, or do they also refer to third-sector organizations and civil society in general? Finally, is transferability a system output or a risk of the homogenization of experiences on the ground?

These are not purely academic questions since the answers they provide significantly impact the very dynamics of democratic innovation and its ability to serve as a toolkit for inclusion and not just a “top-down” organization procedure.

An attempt to redefine commoning practices in a horizon other than the one that focuses on the centrality of the city can be identified in the reemergence of the concept of community, which is obviously distinct from sovereigntist neocommunitarianism. The concept of community constitutes one of the controversial aspects of both participation studies and urban studies. Although it is, in fact, a central notion, it remains vaguely defined and, above all, difficult to operationalize in empirical terms. Over the last two decades, many studies have attempted to go beyond the idea of community as a stable structure that is continuous over time with clearly defined internal relations to conceptualize community as a fundamentally liquid structure with relations that are not necessarily durable over time and where the relationship between a community's territory and its practices of commoning are of particular importance. In other words, the spatial and relational dimensions with respect to this territory have become prevalent over the temporal dimension. This change in perspective has made it possible to consider territorial communities using social practices and, above all, urban practices in spaces of sharing. At this level, it has become possible to study hybrid “social bodies” in which the participatory dimension nevertheless constitutes one of the qualifying elements of social relationship.

Urban communities are realities connected to a territory, albeit often in a non-ascriptive manner, where relations are made possible by political action. Recently, many Italian territorial realities—mostly urban—have employed certain early twentieth-century methods of mutual aid societies, reversing them with a network logic of a marked political propensity. This has given rise to experiences that are very different from one another but share the need to recreate a participatory architecture capable of going beyond the exhausted forms of political organization (such as parties, old neighborhood committees and trade unions). A census of realities of this type—even on a national scale—is almost impossible due to both the substantial “liquidity” of some of them and the plurality of their models and practices, although most focus on egalitarian and inclusive practices of “going common”. Even defining a typology is a difficult task and is in any case a form of reducing a very high social complexity. In this social “universe”, in fact, one finds experiences of a diverse nature. For (partial and limited) example, we can mention (a) street association, i.e., a territorial community created with the function of “defending” a limited space or, at most, urban regeneration; (b) technological reappropriation, where groups of communities share access to the internet through open wi-fi connections; (c) movement experiences with a strong territorial connotation whose activity involves the creation of political awareness through the transmission of knowledge (regarding, e.g., home baking, the creation of shared gardens, training on ethnic foods, and providing information concerning citizens' rights); (d) horizontal solidarity groups built from solidarity buying groups (often linked to a territory but not necessarily limited to one), which engage in struggles in defense of housing or, more generically, in cohousing projects; (e) urban communities in the proper sense, which are often activated by one or more of the abovementioned motivations but are capable of organizing themselves in a stable manner as a space of confrontation and political commitment in their territory. These different experiences and organizational forms share what is sometimes called creative participation, an expression also used in many forms of “horizontal” democratic innovation.

It is in this scenario that participatory experiences in which the dimension of care (The Care Collective, 2020) has taken on a specific function, especially for inclusive interventions in “liminal” contexts, have developed. These experiences constitute the specific dimension of the field research presented here.

Participatory processes in liminal contexts

Our focus is on “liminal spaces”—spaces characterized by both (1) processes of refiguration (Knoublach and Löw, 2017) due to polycontextualization, deep mediatization (Hepp, 2020) and translocalization (Hepp, 2015) and (2) processes of marginalization, i.e., gentrification (Sennet, 2018) and defamiliarization (Blokland, 2017; Blockland et al., 2022).

A “liminal space” is located “at the boundary of two dominant spaces, which is not fully part of either” (Dale and Burrell, 2008). Spaces such as these are not easily defined in terms of their use and are not clearly “owned” by a particular party. This is in direct contrast to dominant spaces, which are defined by mainstream uses and typically have clear boundaries and where the practices within them are interwoven with social expectations, routines, and norms.

We assume that when communities inhabit liminal spaces and consider them vital and meaningful to their everyday lives, these areas cease to be ambiguous spaces and instead become transitory dwelling places that provide sense to the activities, languages, and instances that develop therein (Casey, 1993).

How are these spaces reconfigured by deep mediatization change? Is it possible to imagine the communities living these spaces, and if so, how?

First, we must acknowledge that spaces are reconfigured through both deep mediatization and a distinct sociality (Hepp, 2022; Million et al., 2022). Individual and collective action is enacted in hybrid and changing spaces that do not allow us to imagine social order but may, however, represent an opportunity for widespread relationality between strangers (Small, 2017). This can lead to the constitution of increasingly hybrid communities, which are momentary and noncontinuous as well as intermittent, with a symbolic force capable of breaking down pre- existing patterns, models, and mental representations. Where can they be found? The answer is in both everyday life experiences and more formal and institutionalized settings.

Hybrid processes (physical and digital) are also intertwined with participatory processes in nonconscious and unconventional ways among the inhabitants of liminal spaces. Indeed, the communicative flows of a hybrid participatory process begin with not only the stimulation of specific interests or problems but also the stumbling (chance) into the participatory process itself. That is, inhabitants may encounter spaces for more or less organized discussion that satisfy their specific, contingent interests and sometimes also their personal desires and aspirations.

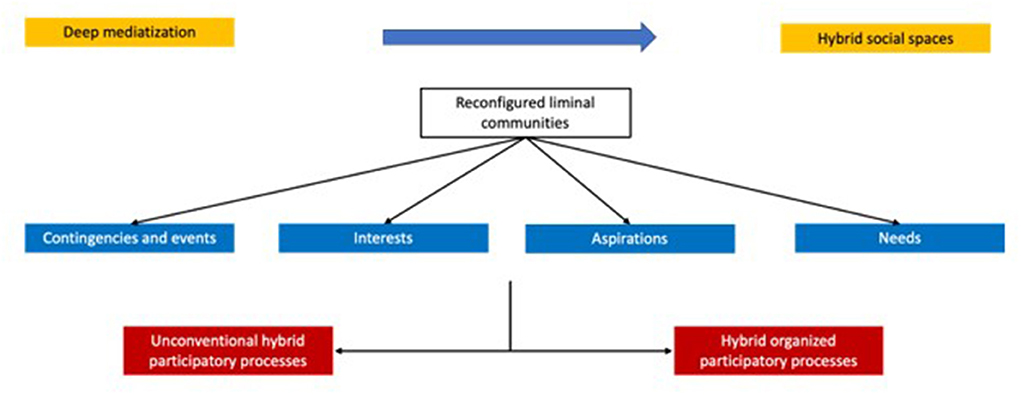

The distinction between inclusive and meaningful participatory processes (Geissel and Joas, 2013) also constitutes a fundamental element in hybrid participatory processes because the intersection of these two processes makes it possible to assign “value” to onsite and digital participation and, above all, make reconfigured liminal spaces attractive from both an organizational and unconventional/informal perspective. An initial explanatory scheme is summarized below in Figure 1.

To these reflections should be added the issue of digital inclusion. As many authors have stated (Tsatsou, 2011; Choudrie et al., 2018), digital inclusion refers to the growing need to involve the most vulnerable populations in digital spaces, as such populations often remain excluded because of both the digital divide and their typical lack of the cultural and social skills that are necessary to transform digital resources into opportunities for capability growth (Sen, 1987; Zamani, 2018). As some recent reflections following Bourdieu's thoughts on cultural and social capital have highlighted (Ragnedda and, 2020), we need to consider digital inclusion in terms of digital capital:

Digital capital is the accumulation of digital competencies (information, communication, safety, content creation and problem solving) and digital technology. As with all the other capitals, its continual transmission and accumulation tend to preserve social inequalities. In Bourdieusian terms, we may define digital capital as “a set of internalized abilities and aptitudes” (digital competencies) as well as “externalized resources” (digital technology) that can be historically accumulated and transferred from one arena to another. The level of digital capital that a person possesses influences the quality of the Internet experience (second level of the digital divide), which, in turn, may be “converted” into other forms of capital (economic, social, cultural, personal, and political) in the social sphere, thus influencing the third level of the digital divide. (Ragnedda, 2020: 2367)

The most vulnerable people therefore have a level of digital capital that is inevitably affected by both existing inequalities and the continual increase in digital complexity via the ongoing growth of datafication, algorithms and platform society (Van Dijck et al., 2018; Couldry and Mejias, 2019; Ragnedda, 2020).

Within this framework that we have tried to outline, we have identified some case studies in the liminal and vulnerable spaces of some Italian cities that have adopted hybrid participatory approaches and processes for the social and digital inclusion of marginal people to reconfigure these urban spaces with related proposals for rethinking everyday life.

Case studies in 6 Italian urban contexts: Case selection and research method

Italy is an interesting case to study for studying the nature and orientation of urban transformation, especially in peripheral and liminal areas. Made up of over 8,000 urban communities, Italy however has a rather small number of large cities, intended as multilayer urban contexts, home for plural economic and institutional services, inhabited by different communities and served by big-city level infrastructures (transportation services, waste cycle, energy and water resources). During the 2010s, in order to provide some large cities with an administrative statute aimed at promoting integration with the peri-urban and regional territory, the law on metropolitan cities was approved, indicating the 14 cities that could benefit from this new statute and outlining the powers regarding the integration of local services.

This reform has turned the spotlight on these large cities, each different from the other, but with a common issue in terms of peripheral and liminal spaces. Furthermore, in the same years, a strong trend toward urban regeneration—also in participatory terms—of peripheral and liminal spaces has established both in the scientific literature (Garau et al., 2015; Rabbiosi, 2016; La Rosa et al., 2017; Bottero et al., 2018) and in the political-administrative practice of large Italian cities. In the context of this change in the administrative role of large cities and with attention to the urban regeneration of peripheral and liminal areas of urban contexts, our research question was aimed at verifying whether and how these urban, social, economic regeneration interventions found correspondence in the main theoretical models of urban change highlighted in par. 1. Due to these specific features of metropolitan areas, urban regeneration projects have shown a weightier impact on urban spaces and communities, which we considered exploring with a qualitative methodology.

Methods

After defining our research question, we developed a two-step methodological plan. First, we started our fieldwork by reflecting on the opportunity of engaging through a qualitative approach to research and selected the case study method with the intention—well presented by Aspers and Corte (2019)—of “getting closer to the phenomenon studied”. Consequently, we proceeded to the selection of 6 case studies in Italian metropolitan areas, collecting material about the most innovative city level new experiences of social, environmental, and cultural participation in regeneration in suburban contexts. This phase of background research was developed through open sources of different formats (local media, digital platforms, websites dedicated to urban regeneration, and scientific articles), and it was necessary to develop specific information on the civic and social realities that were operating in these different urban contexts. Then, this more significant and accurate knowledge of the context and background of our research [as Flyvbjerg (2011) states this phase is consistent with the model of social studies that “generate context-dependent knowledge”] enabled the selection of 6 organizations as our case studies to further develop an investigation strategy. According to this logic of the interrogative comparison of the social practices in the liminal areas of the considered cities, we proceeded in the direction identified by George and Bennett (2005, p. 5), who state that the middle-range or typological theories produced by a case study “can accommodate various forms of complex causality”. Complex causality thus resulted from the interaction between the general model of a neoliberal city and the highly localized participatory communities in the specific liminal spaces we have identified above. Third, we proceeded to investigate the complex relationship between the general neoliberal model of cities and the specific contexts of participation in urban regeneration activities in the peripheral areas with a series of semi structured interviews aimed at the organizational subjects of the 6 case studies.

In doing so, we tried, following the indications of Seawright and Gerring (2008), to identify our different case studies by nature of their organization, type of intervention, the liminal scope of intervention, the expected and real impact, the intervening factors (such as interruptions related to COVID-19) and the emerging perspectives, e.g., the urban regeneration of the suburbs advanced by the national recovery and resilience plan (“PNRR”). Our hypothesis necessitated testing the extent to which different organizations in diverse Italian urban contexts find common factors of strength, weakness, risk, and opportunity in participatory practices for social and cultural regeneration.

Our basic goal for selecting organizations as our city case studies was to collect and evaluate the experiences of different types of organizations. Specifically, in addition to their format (nonprofit organizations (NPOs), cultural organizations, citizen networks, social enterprises, consortiums), they all should have delivered an idea of urban regeneration that transcend the mere transformation of the physical spaces of their city; at the same time these organizations had to be dealing with the interception of the latent or expressed needs of the citizens living in liminal context, while supporting bottom-up formulation of responses by the means of active citizenship, community building, and network creation. In the selected case studies, we were looking for an organizational approach that moved beyond the idea of urban regeneration in vogue within the perspective of the neoliberal city (improvement of space design, securitization, “smart city-zation”, tactical urbanism). We selected organizations of different level, format and size that we found to be seeking to promote and accompany an idea of local community development in liminal spaces, a process that is often relinquished by local public institutions and economic actors.

Our field research was conducted in the period March-May 2022. The participants were selected after an in-depth theoretical study of the main urban regeneration interventions in the 14 Italian metropolitan cities. The group discussion about the opportunity to proceed to further investigations and the in-depth interview was the basis for the selection of the 6 case studies. The main purpose of the research group was to include the widest representativeness in territorial terms (two cases in the North, in the Center, in the South of the national territory) and the greatest possible variability of subjects active in urban, social, economic regeneration of the peripheral areas of metropolitan cities.

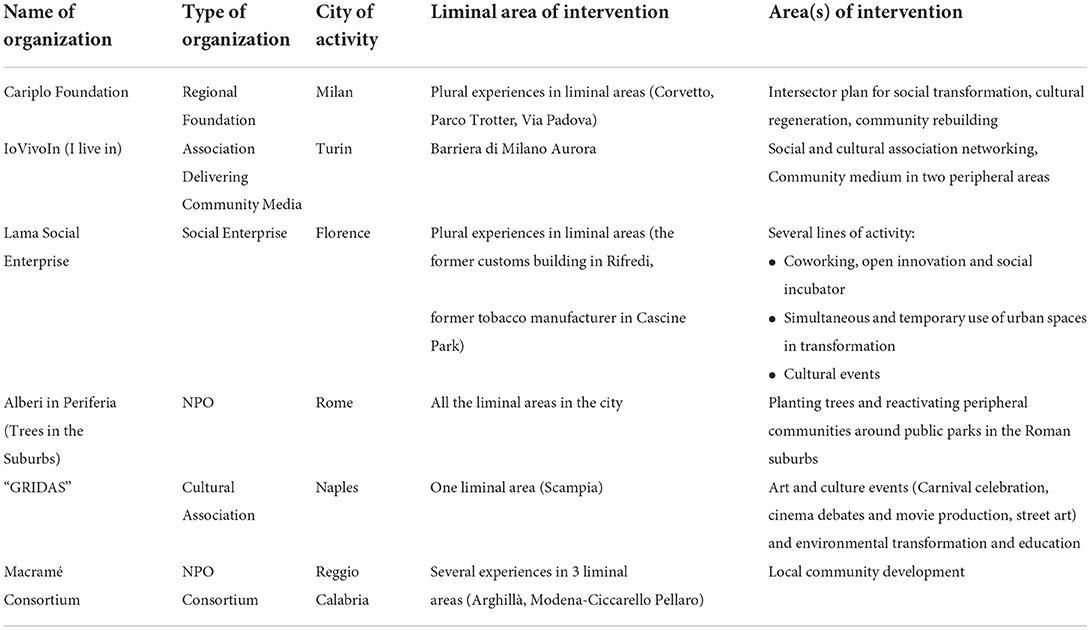

The organizations we interviewed for fieldwork in 6 Italian urban contexts are described in Table 1, while the localization of the case studies on map is in Figure 2.

We applied the semi structured interviews (SSIs) to increase our overall knowledge of two relevant aspects. On the one hand, the SSIs constituted a pivotal tool for understanding the liminal urban contexts of the different cities, as described by relevant testimonials. On the other hand, SSIs remain the most accurate technique for observing the vision, purposes, limits, and opportunities that are self-identified by interviewees, and the adherence to the theoretical model of urban regeneration.

The five main sections that we deemed worth investigating directly with testimonials were as follows:

• General aims pursued through the project/program of social, cultural and community regeneration being carried out.

• Main relations produced by planning with institutional, economic, civic and third sector actors.

• Impacts of the project/program.

• Emergent difficulties and deficits in the liminal context after the start of the project/program (including those related to the COVID-19 pandemic).

• Future perspectives and objectives.

Examining these dimensions had a twofold purpose. On the one hand, they fostered our overall need for a deeper and better understanding of the phenomenon of social regeneration in the various areas of cities. On the other hand, they were essential to answering the central question of our fieldwork: How do those subjects who are active in the social regeneration of liminal urban areas comprehend and present their role while negotiating their restraints and opportunities in the dominant context of a neoliberal city?

Thematic analysis, discussion and results

When evaluating the material emerging from the interviews and their testimonials of social, environmental and communitarian regeneration in the liminal spaces of metropolitan areas, we considered several aspects: 1. the coherence of the activities conducted with the theoretical approaches to cities presented in section one; 2. the use of participatory approaches and tools described in section two; 3. the organization's self-perception in regard to its ability to build relationships with the institutional, economic, civic and third-sector subjects involved in its peripheral area(s); 4. the self-perception of the limits and development potential of the projects/programs being carried out; 5. the challenges to and opportunities for the regeneration of a city in the context of the lockdowns and crises during the COVID-19 pandemic and of the subsequent national plan for recovery and resilience.

Our analysis of the case studies revealed some contradictory aspects with respect to their participatory processes.

Most of the analyzed activities connected to the context of the commonality perspective, with a definite trend in the context of Milan, Rome and Turin, where the idea of common extra-institutional effort to regenerate urban peripheries is animated by the networking of the involved organization with associations and civic committees. Instead, in the case of Reggio Calabria, we detected an approach aimed at creating and empowering territorial communities; this may be linked to local social practices, emerging from the active involvement of the third-sector consortium supporting and accompanying three liminal communities in identifying their community development path (discussion on the local resources, identification in a local community, social relations building, community planning for future development). The case of cultural and environmental regeneration in Naples seemed to lie between the cultural and environmental movement experience and the urban community, with some elements referring to the commonality hypothesis, and others linking to the culture of social centers, extremely lively in Southern Italy. In this halfway model, all Neapolitan citizens (artists, filmmakers, third-sector subjects, civic engagement actors) supported the set of values carried out by the leading “Scampia3” cultural association. An approach straddling the neoliberal model of the city and the technological reappropriation of urban spaces in transformation emerged in Florence, where the neoliberal vision of the urban transformation prevails over the cultural and artistic activities proposed in the physical transformation of the spaces, especially in the context of Tobacco Manufacture regeneration. This technological reappropriation of socially innovative spaces has reshaped the former City Customs building, through its regeneration into a “smart working” location for physical, digital, economic, and social innovation.

We then analyzed a multifaceted approach concerning the second dimension—the participatory approach implemented by organizations in peripheral contexts. Even in this area of analysis there is no univocal project profile for the organizations we examined. Some engaged in cultural and pedagogical movement practices with the community (Naples Scampia) to create an organic and systematic plan involving peripheral populations (Reggio Calabria) with the local community development program. Others enacted a more standard perspective through codified tools with citizen involvement, stakeholder engagement, and agreements for the joint administration of common goods in Milan and Florence. In the Roman case, we observed non structured cooperation with other territorial civic subjects that were open to the dimension of the periphery. In Turin, the experience of building a peripheral community medium was twofold. On the one hand, it strove for networking the social and cultural organizations in the two peripheral areas; on the other hand, the project aimed to co-construct information that is useful for the communitarian participation of citizens in two suburbs, pairing it with an intense associative life.

In our perspective, this variety in the models of participatory openness is mainly a function of the different peripheral conditions under which organizations operate; then it derives from each organization's culture, which derives from previous its social and cultural regeneration activities in a peripheral area. The organizational culture of a territorial ecological association (Rome) or a local cultural movement (Naples) differs from the participatory approach of a network of third-sector organizations (Reggio Calabria, Turin), a social enterprise (Florence), or a large foundation (Milan). From our perspective, the main differences in the organizations' participation tools for social and cultural regeneration activities seem to primarily reflect these two factors (social context of the involved periphery, organizational culture of the intervening subject) rather than the neoliberal urban condition that is common to all the analyzed experiences.

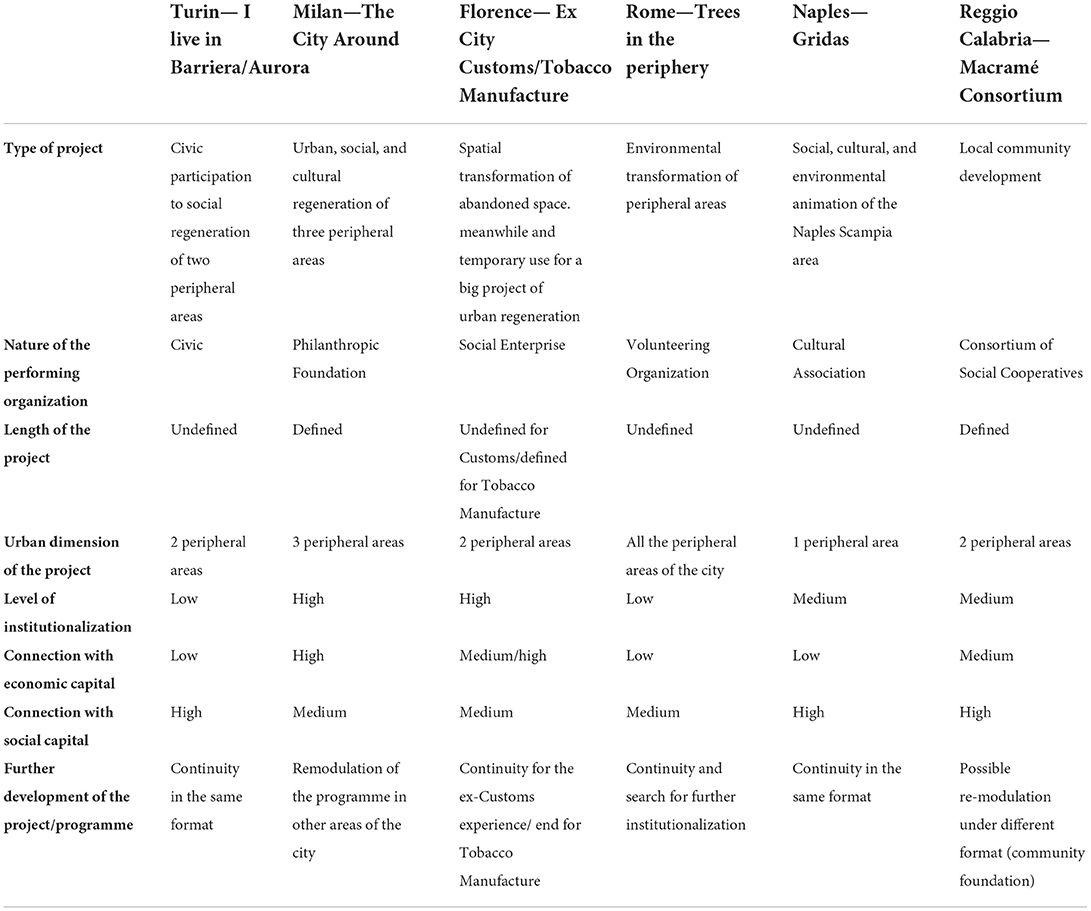

We summarize the differences in the organizational approach and in the endowment of economic, social and institutional resources, as well as possible developments of the projects and programmes in Table 2.

The second aspect to highlight is the role of local institutions. In the case of Milan and Florence, local institutions play a bureaucratic/functional role in supporting the proposed activities in these communities, intervening only partially with political decision-making in the first case:

For the initiative carried out in Rifredi, the relationship with the institutional dimension was rather reduced since it was a private–private project. In the project carried out with Manufacture Tabacchi, the governance is mixed public–private, but with an evidently supra-local dimension of the public institutions involved. (Florence)

The genesis of the program was the signing of a memorandum of understanding between the municipality and the foundation, in which, precisely, the common goals and the tools available to the two parties were made explicit; thus, the public administration and the foundation, to pursue these common goals, were developed. (Milan)

In Naples, the institutions' presence is predominantly formal, leaving space for community movements and associations to address and resolve emerging issues in the community:

Our activity of cultural, environmental, and social animation has taken place amid a great absence of institutions over the years, or even worse, due to an institutional intervention that sometimes comes to block rather than facilitate the resources of social and cultural protagonism that spontaneously arise in this context. This is a problem at the moment, when these resources on the ground are not only not put to good use by local institutions but also hindered by a bureaucratized model of managing every activity. For every initiative, for every detail, for every activity, many bureaucracies, forms, and PECs4 are required. (Naples)

In Turin, the institutional relation activity is limited to the local dimension of the city institutions and to some political figures with specific insight into peripheral contexts: We have often dealt with local articulations of the city institutions (“Circoscrizioni”) … that in evaluating our experience have appreciated its innovative dimension and proposed collaborations and exchanges of experience with us, but with no outcomes thus far. We have also interacted with some politicians of the municipality, which have been characterized by a deeper knowledge of the two peripheral areas, but still with no impact on our activity.

In Rome, the only administrative involvement of the institutions explicitly omits political involvement in the initiatives:

This is why we support institutional relations of an administrative type more than political ones: to avoid being exploited through the logic of an electoral campaign and to guarantee a lasting result for our green regeneration actions in the suburbs. (Rome)

In Reggio Calabria, meeting with local institutions is defined by chance and individual sensitivity:

But we also had lucky encounters with some councilors who turned out to be attentive and sensitive, who managed to understand how essential it is to enter the communities and stay in the area in order to be able to reconstruct history on the one hand and a vision for the future on the other. (Reggio Calabria)

In all cases, local institutions tend not to take part in the bottom-up participatory processes that have been established either through specific resources or an active presence.

In their self-evaluation of their organizations, cultural, environmental, and social regeneration impacts liminal civic communities by building relational capital, distributing cultural opportunities, enhancing the environment, and facilitating occasions for public dialog in both face-to-face activities and digital platforms. Nevertheless, members of these organizations mostly complain about specific factors such as delays due to complex formats of dialog with local administrations (Milan, Florence), and shortcomings in more systematic policies of development. The latter includes a lack of integration activities in peripheral contexts (Naples, Turin), scarce involvement of city politics in the outcomes produced by organizations (Rome), and limits for the continuity of support for programs launched (Reggio Calabria). In the interviewed organizations a common perception comes to light: in the presence of a non-bureaucratic and directive approach by local institutions, many of the results produced would have occurred earlier or more impactfully.

Another aspect to pay attention to is the territorial social capital of the organizations that are the engines of the initiatives analyzed. In the case of Milan, the territorial social capital is incentivized with financial resources to set up initiatives a posteriori. There is no work to build relationships or specific participatory processes before and during the performance of salient activities; instead, top-down tools are imagined responding to the needs of the communities:

The community points constitute the central lever. They are intended to be engagement devices, that is, the operational and concrete tools through which the program implements, together with the communities, the objectives. These are community hubs that try to respond to the needs of the territory in which they are grafted, starting precisely from the resources highlighted and reported and in practice. (Milan)

In Florence, however, the situations are different. In one case, Manufacture Tabacchi, top–down relationships had been built:

Since this is a private property with a private address and an approved masterplan, there have been no participatory processes for the involvement of these realities, but great attention has been given to ensuring maximum information on the works. (Florence)

In another case in the Rifredi district, however, the construction of widespread relationships had been placed at the center of the activities:

The networks for the activation of the district have been created not only with the formal and informal associations of economic-commercial operators but also with all the realities of citizens present in the area who have been able to grasp the meaning and direction of social innovation that we brought to the territory where they live. (Florence)

In Naples, social capital was and is fundamental to the continuity of the actions in the Scampia district, albeit with particularly significant difficulties:

We strongly believe in the social value of bottom-up networks, and we … finance our activities in this way, especially in a context like Scampia, where from the early 1980s onward, there were only buildings. Only later, and in some circumstances thanks to the generative capacity of GRIDAS, was a network of associations created. These groups and associations were born, by the same admission on their part, thanks to the attendance of the Carnival of Scampia, intended as an artistic– cultural moment of organizing the workshops and subsequently as a participation activity open to all the inhabitants of Scampia. (Naples)

In Reggio Calabria, the problem of how to build relationships with citizens of liminal communities was placed at the center via an expansion of the network and informal contact processes:

Arghillà has the characteristics of the outskirts of Scampia, of Tor Bella Monaca. Therefore, for all third-sector operators, the main problem with respect to the context was understanding how to enter it and how to relate, given that not even the police were able to enter. The institutional response that came was to treat the social problem only in terms of security and to propose policemen in the territory rather than social educators. This approach has resulted in even greater community closure, and as a third sector, we have had even greater difficulty in entering. But we entered on tiptoe, not alone but together with other subjects of a large network made up of amateur sports organizations, voluntary organizations, [and] local staff. (Reggio Calabria)

Additionally, in Reggio, the work that has been conducted through a local digital platform is interesting:

This, however, in a way that is only apparently paradoxical, has developed expectations on the part of the communities involved because the investment in relationships even in an excessive format, perhaps even disconnected from real necessity, has led to a request for relationships, passed on with the format of the digital community that we had set up. We spent whole days together online thanks to these tools that were dedicated to the three digital communities. These expectations of relationality have produced intense digital community building work centered on reciprocal relationships. (Reggio Calabria)

In Turin, the local community's social media platform has connected both the rich context of associations and resident citizens. Its aim is producing, through information diffusion, associative networking, and community development:

We found that this widespread and dynamic associationism is the result of a desire for social redemption—specific to those segments of civil society with the cultural means to react, to do something useful in this neighborhood thanks to the ability to take action… At the same time, there was no reference tool for the citizens who live in these two neighborhoods to know what is happening and to share experiences... Hence, the idea of the community medium, dedicated to associative networks, [emerged,] which then became a tool often used by citizens to learn what is happening and what will happen in their neighborhood. The purpose of the community medium is also to reach, with information on the activities, all those people who thanks to a model of community participation would feel less alone or less afraid in these neighborhoods. (Turin)

Finally, in Rome, territorial social capital was built through tree planting actions:

Neighborhood committees, citizens' associations, and groups gathered around schools are a fundamental element of our project because they are, together with us, protagonists, in different ways, in the regeneration that takes place within their respective territories. They can become volunteers of our association, donate trees to us through crowdfunding, offer their advice, and adopt the trees we plant. (Rome)

An important aspect is the financial resources that have allowed the development of actions in liminal communities and derive from private funds (Milan and Florence), from public funds (Reggio Calabria), from the resources of sponsoring third-sector organizations (Rome and Naples) or from civic crowdfunding (Naples). In the cases of resources derived from private funds, the need for investments to produce income (in some direct, in others indirect due to the generation of commercial and entrepreneurial initiatives in the areas) is quite evident:

Over the years, this company has developed a model called Gotit. Value path is a call for innovative startups with a social impact that are selected on the basis of certain criteria and are entered into an incubation and mentoring path. At the end of the path, by participating in an investor day when the social venture foundation itself is present, together with other potential investors, it is decided in which realities to invest patient capital resources. (Milan)

While we were carrying out this project in Rifredi and all the remaining cooperative work (private assistance, consultancy, evaluation, and impact assessment) in 2017, we were contacted by an investment fund…, which is the owner of the property of the Tobacco Manufacture Building… for a sociocultural accompaniment project that stands alongside the space regeneration work in the structure. (Florence)

Regarding the use of public resources in Reggio Calabria, interventions were imagined that could broaden the initial idea of financing civic laboratories to foster the participatory development of the three liminal communities involved:

Probably, the theme of urban regeneration is a subsequent theme to the paradigm of our intervention in Pellaro, Arghillà and Modena-Ciccarello, peripheral areas where we have created, together with the neighborhood communities, paths of involvement and social participation.... we have taken action to regenerate communities, from a relational point of view, as a prerequisite for any development, whether structural or infrastructural, of the urban spaces in which the communities of Pellaro, Arghillà, Modena-Ciccarello live with a series of activities. [Through] mapping, action research, and civic laboratories managed on behalf of the municipality of Reggio Calabria … we have followed an open tender procedure on MEPA in the context of social regeneration interventions called “Cantieri della Bellezza”.

To involve the entire community in the neighborhoods of Arghillà, Pellaro, Modena- Ciccarello, we have created some process paths aimed at activating territorial groups: create networks among the subjects of the local community; build a “community map” of the neighborhoods; set up research groups with public social operators and other subjects operating in the area; train “community activators”, operators who—followed and accompanied by experts—have learned to intercept the needs of their community, speak and listen to the people who live and inhabit their territory, and find shared solutions to their needs; and initiate territorial animation actions (neighborhood walks, interviews, life stories, informal talks, neighborhood assemblies). (Reggio Calabria)

In the case where the resources of third-sector organizations have been more relevant, creativity in finding innovative solutions is higher:

... the activities conducted by Gridas are carried out by self-financing or collaborating with the network of associations in the area. The only reality with which we collaborate, for example, for the realization of cultural productions, is the platform productions of dal basso.com, an independent platform for supporting the main initiatives. We have used this digital tool to raise funds to print books, to make films, and to start environmental projects in the area. (Naples)

Finally, regarding the activities conducted during the pandemic lockdowns and with the perspective of recovery, the interviewed organizations—in line with the capacity for social innovation and the functional flexibility of the third sector and civic organizations—experienced and led innovative formats and practices to digitize social, environmental, and cultural regeneration. All the organizations have worked to keep community ties intact. They have devised new ways to experience the digital dimension of social, environmental and cultural regeneration: from the transfer on a digital platform of artistic and cultural events (Naples) to digital environmental education (Rome); from digital community building (Reggio Calabria) to the complete digitization of community media during the pandemic, discontinuing the relevant in person activities on a project (Turin); and from the need to find new formats for simultaneous and temporary use (Florence) to the ability to find new digital engagement devices (Milan). In a common perspective, the pandemic has been an opportunity for social innovation in formats (with consistent use of digital technology) and in designing new content and tools (with a drive to look beyond the usual dynamics of civic involvement in peripheral spaces).

Nonetheless, for all the interviewed organizations the current recovery phase seems more complex; in the face of an incomplete return to activities in the present, new problems and side effects seem to characterize these contexts. Uncertainty about the future due to the pandemic, energy crisis and war; difficulty in restarting the action of city institutions; the prospect of working in new organizational contexts dominated by the formats of National recovery and resilience plan seem to restrain the resilience of these organizations. The social, cultural, and environmental regeneration activities that started before the pandemic continue to advance. However, uncertainty about the future affects the ability to imagine new actions in peripheral and liminal contexts, presenting a higher economic and social risk. The contingency characterizing the political and economic dimension also seems to have an impact on the third sector and civic organizations, especially those working in contexts affected by difficult conditions, as peripheral and liminal spaces.

Conclusions

The experiences that constitute the subject of our field research are not ascribable to the phenomenon of “participationism”, i.e., to those procedures activated in the framework of depoliticization processes that often favor forms of access without enabling actual practices of meaningful participation. At the same time, however, the poles of participation engagement logics are found. On the one hand, these include those promoted by public administrations (engagement by invitation); on the other, they comprise those more markedly “from below” (Sorice, 2021).

Table 3 articulates the two significant modes of participation that we have discussed. The first—derived from top-down procedures—is based on the adoption of deliberative processes and is not limited to the dimension of consultation or collaborative governance (more or less articulated). The second refers to the procedures of co-management in a territory and includes some forms of direct social action (Bosi and Zamponi, 2019) and, in some cases, of connective action (Bennett and Segerberg, 2013). The cases we studied fit, in an articulated but not always clearly defined way, the pattern proposed by Table 2.

In this article, we have tried to highlight the dual role, both real and potential, of participatory dynamics in different social and territorial contexts that are clearly placed in a broader socioeconomic context that is easily defined as “neoliberal. “The analysis reveals some dimensions to reflect on:

• Differences in the territorial dimension (social, cultural and economic characteristics) affect the experience and history of social actors as facilitators or not of 'civic empowerment' processes (e.g., the different situations of social actors in Milan and Naples).

• There is a continuum of experiences, which, as shown in Table 2, move between bottom-up and highly proceduralized patterns of participation. The latter are ultimately essential to the neoliberal paradigm of bottom-up legitimization of choices made 'at the top' through mechanisms that tend to exclude those parts of communities that are most vulnerable and liminal.

• The dimension of bureaucratization linked to local public institutions. There is a strong perception on the part of all the social actors surveyed that in the presence of a non-bureaucratic and directive approach on the part of local institutions, many of the results produced would have been obtained more quickly and, above all, with a greater impact on the territory.

• the relevance of the dimension of financial resources and territorial social capital resources. In particular, when those of third sector associations are more relevant, the development of more significant forms of 'creative participation' also appears to be greater.

• The existence of a plurality of approaches to the commons, which shift between the liberal frame, and one based on an idea that participation is a political process.

In conclusion, we can state that we expect participatory processes to cause real (significant) changes in both public policy agenda priorities and proposed measures, enabling increased transparency of procedures and, finally, citizen empowerment. Political participation, in other words, should foster inclusion and substantive equality. However, this goal is not always easily attainable, due to the problematic dimensions we have shown, undermining the participatory empowerment of vulnerable individuals in liminal spaces.

Other phenomena—the processes of social platformization (Van Dijck et al., 2018), the fragmentation of the public sphere (Schlesinger, 2020), and the emergence of a participatory narrative that effectively anesthetizes the political dimension of participation—favor a neoliberal storytelling, which contributes to making some participatory processes mere procedures that are incapable of fostering the inclusion of vulnerable people. It is clear, however, that the very capacity of participatory instances to foster real inclusion is a central element in the democratization of democracy.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The concept of liminal space comes from anthropology and specifically from Turner's studies (Turner, 1974). Over time, however, the concept has been used in diverse meanings, encompassing both places of social marginality (including borders, no man's land and disputed territories) and the “empty spaces” found in some social media. Special uses of the term are, anyway, present also in religion and other disciplines. Here we use the concept in a sociological perspective, also including the processes of refiguration (Knoublach and Löw, 2017) and the processes of marginalization. See also: Shortt (2015) and Andrews et al. (2019).

2. ^We define democratic innovation here not only in a top-down direction but also via a dialogic and horizontal approach. Specifically, “The term democratic innovation covers all procedures aimed at facilitating and increasing citizens' access and political participation, which are realized both through institutions specifically designed to increase public participation and through bottom-up experiences capable of providing connections to institutional practices in policy-making and political decision-making processes” (Sorice, 2020b).

3. ^Scampia is a district of Naples.

4. ^PEC is the Italian acronym for “certified email”.

References

Andrews, N., Greenfield, S., Drever, W., and Redwood, S. (2019). Intersectionality in the Liminal Space: Researching Caribbean Women's Health in the UK Context. Front. Sociol. 4, 82. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2019.00082

Aspers, P., and Corte, U. (2019). What is qualitative in qualitative research. Qual Sociol. 42, 139–160. doi: 10.1007/s11133-019-9413-7

Bennett, W. L., and Segerberg, A. (2013). The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blockland, T., Kruger, D., Vief, R., and Schultze, H. (2022). “Where we turn to. Rethinking networks, urban space and research methods,” in Spatial Transformations. Kaleidoscopic Perspectives on the Refiguration of Spaces, eds A. Million, C. Haid, C. I. Ulloa, and N. Baur (2022). New York: Routledge, 258–268.

Bosi, L., and Zamponi, L. (2019). Resistere alla crisi. I percorsi dell'azione sociale diretta. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Bottero, M., D'Alpaos, C., and Oppio, A. (2018). “Multicriteria evaluation of urban regeneration processes: an application of PROMETHEE method in Northern Italy,” in Advances in Operations Research. Available online at: http:link.gale.com/apps/doc/A574695061/AONE?u=anon~a5eb689b&sid=googleScholar&xid=15b60315 (accessed September 28, 2022).

Brown, W. (2006). American Nightmare: Neoliberalism, Neoconservatism, and De-Democratization. Political Theory, 34, 690–714. doi: 10.1177/0090591706293016

Casey, E. S. (1993). Getting Back into Place: Toward a Renewed Understanding of the Place- World. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Choudrie, J., Tsatsou, P., and Kurnia, S. (2018). Social Inclusion and Usability of ICT- Enabled Services. New York: Routledge.

Couldry, N., and Mejias, U. (2019). The Cost of Connections. How Data is Colonising Human Life Appropriating it for Capitalism. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Dale, K., and Burrell, G. (2008). The Spaces of Organization and the Organization of Space: Power, Identity and Materiality at Work. London: Palgrave.

Dardot, P., and Laval, C. (2010). La nouvelle raison du monde: Essai sur la société néolibérale. Paris: La Découverte. doi: 10.3917/dec.dardo.2010.01

Dardot, P., and Laval, C. (2015). Commun: Essai sur la révolution au XXIe siècle. Paris: La Découverte. doi: 10.3917/dec.dardo.2015.01

Fawcett, P., Flinders, M., Hay, C., and Wood, M. (2017). Anti-Politics, Depoliticization and Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flinders, M., and Buller, J. (2016). Depoliticisation: principles, tactis and tools. Br. Pol. 1, 3. 293–318. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.bp.4200016

Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). “Case Study,” in The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, eds N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 301–316.

Garau, C., Balletto, G., and Mundula, L. (2015). “A critical reflection on smart governance in Italy: Definition and challenges for a sustainable urban regeneration,” in International conference on Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions. Berlin,Germany: Springer, Cham, 235–250.

Geissel, B., and Joas, M. (2013). Participatory Democratic Innovations in Europe: Improving the Quality of Democracy? Berlin: Barbara Budrich Publisher. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvdf0gdc

George, A. L., and Bennett, A. (2005). Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hall, S., and O'Shea, A. (2013). Common-sense neoliberalism. Soundings: A Journal of Politics and Culture 55, 8–24.

Hepp, A. (2022). Agency, social relations, and order: Media sociology's shift into the digital. Communications 1–24. doi: 10.1515/commun-2020-0079

Knoublach, H., and Löw, M. (2017). On the spatial refiguration of the social world. Sociologica 2, 1–27. doi: 10.12759/hsr.45.2020.2.263-292

La Rosa, D., Privitera, R., Barbarossa, L., and La Greca, P. (2017). Assessing spatial benefits of urban regeneration programs in a highly vulnerable urban context: A case study in Catania, Italy. Landscape Urban Plann. 157, 180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.05.031

Million, A., Haid, C., Ulloa, C. I., and Baur, N. (2022). “Spatial transformations,” in Kaleidoscopic Perspectives on the Refiguration of Spaces. New York: Routledge.

Ostrom, E. (2015). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rabbiosi, C. (2016). Urban regeneration ‘from the bottom up' Critique or co-optation? Notes from Milan, Italy. City 20, 832–844. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2016.1242240

Ragnedda, M. (2020). Enhancing Digital Equity: Connecting the Digital Underclass. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Rifkin, J. (2014). The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Schlesinger, P. (2020). After the Post-public Sphere. Media Cult. Soc. 42:1545–1563. doi: 10.1177/0163443720948003

Seawright, J., and Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection techniques in case study research: A menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Polit Res Q. 61, 294–308. doi: 10.1177/1065912907313077

Shortt, H. (2015). Liminality, space and the importance of “transitory dwelling places” at work. Human Relat. 68, 633–658. doi: 10.1177/0018726714536938

Sintomer, Y. (2010). Random Selection, Republican Self-government, and Deliberative Democracy. Constellations, 17, 472–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8675.2010.00607.x

Smith, G. (2009). Democratic Innovations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511609848

Sorice, M. (2020a). La piattaformizzazione della sfera pubblica. Comunicazione Politica, 3, 371–88. doi: 10.3270/98799

Sorice, M. (2020b). “Democratic Innovation,” in The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Interest Groups, Lobbying and Public Affairs, eds P. Harris, A. Bitonti, C. Fleisher, A. Skorkjær Binderkrantz. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sorice, M. (2021). “Partecipazione disconnessa,” in Innovazione democratica e illusione digitale al tempo del neoliberismo. Roma: Carocci.

The Care Collective (2020). “The care manifesto,” in The Politics of Interdependence. London: Verso Books.

Tsatsou, P. (2011). Digital Divides in Europe: Culture, Politics, and the Western-Southern Divide. New York: Peter Lang Pub Inc.

Turner, V. (1974). “Liminal to liminoid in play, flow, and ritual: An essay in comparative symbology,” in Rice Institute Pamphlet—Rice University Studies, 60, 3. Available online at: https://scholarship.rice.edu/bitstream/handle/1911/63159/article_RIP603_part4.pdf?sequence=1andisAllowed=y

Van Dijck, J., Poell, T., and De Waal, M. (2018). The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. New York: Oxford University Press.

Keywords: urban regeneration, urban policies, social participation, civic engagement, liminal spaces, digital platforms, vulnerabilities, third sector organizations

Citation: Antonucci MC, Sorice M and Volterrani A (2022) Social and digital vulnerabilities: The role of participatory processes in the reconfiguration of urban and digital space. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:970958. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.970958

Received: 16 June 2022; Accepted: 26 September 2022;

Published: 14 October 2022.

Edited by:

Donatella Selva, University of Tuscia, ItalyReviewed by:

Giulia Allegrini, University of Bologna, ItalyVangelis Pitidis, University of Warwick, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Antonucci, Sorice and Volterrani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria Cristina Antonucci, bWNyaXN0aW5hLmFudG9udWNjaUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Maria Cristina Antonucci

Maria Cristina Antonucci Michele Sorice

Michele Sorice Andrea Volterrani3

Andrea Volterrani3