- Department of Social and Human Sciences, University of Deusto, Bilbao, Spain

The European Values Study (EVS), and also the World Values Survey (WVS), have for decades included a question that asks about the degree of justification of different behaviors and actions, including abortion and euthanasia. Our research aims to study which factors influence the abortion/euthanasia association in Spain and whether this association is also observed in other countries. A factor analysis of the Spanish sample shows that a number of items related to sexuality and death tend to cluster together. This factor could be called “Eros-Thanatos,” and includes the justification of abortion and euthanasia, in terms of ideological consistency. The analysis shows that in Spain, as well as in Europe generally, not being a religious person is the principal factor associated with the greater justification of abortion and euthanasia. The article analyses whether this association in the Spanish data is something that can be generalized to other European countries or whether, on the contrary, there are factors such as culture and the historical past of the countries that modify the relationship. Correspondence analyses applied to different questions in the questionnaire show that it is possible to establish different dividing lines in Europe according to the values of its citizens, shaping a north-south axis and a west-east axis, in which the processes of secularization in Western Europe or the rise in institutional religion in the former Soviet republics might lie behind.

Introduction

Abortion and euthanasia are two facts that can be related to death, but they are also behaviors that have much to do with the exercise of individual freedom. Both refer to legal and religious frameworks, as well as to and cultural frameworks that undoubtedly exert a strong influence on levels of justification.

Euthanasia, etymologically speaking, means a “good death,” and it tends to be associated with the ability to decide freely on the end of our lives. As for abortion or the voluntary interruption of pregnancy, this also poses the dilemma of whether women can choose freely or not, in this case in relation to their bodies and the option of whether to continue or not with a pregnancy. Both acts, euthanasia and abortion, are related to the binomial life/death; but above all, they are related to the political and moral definition of a given society and culture (and, consequently, legislation) regarding the exercise of individual freedom and its limits.

Analysis of the justification of abortion and euthanasia in Spain has always revealed that there was a relationship between the two. This article attempts to describe this relationship and to check whether it also exists in the rest of Europe. Therefore, our research aims to measure the degree of justification of each of these practices among the European population in general and the Spanish population in particular, at the same time confirming whether there are significant differences in their opinions and attitudes in relation to the justification of each practice. If there are, we will attempt to determine which socio-demographic and contextual characteristics might be associated to the different levels of support for each of these practices, attempting to determine not only the justification given to them, but which factors might operate in the differences we find among European citizens. To this end, we have based our investigation on the most recent wave of the European Values Study, conducted in 2017/2018 (EVS, 2022).

Attitudes to euthanasia and abortion in Europe

There are numerous studies on the positions and attitudes of healthcare professionals and students toward euthanasia. However, there is not a comparable volume of studies exploring the opinion of the general population in relation to this topic, even though it is a social question that affects one's own life and that of others. For this reason, without denying the value of the former set of studies, to the extent that they incorporate the opinions of the specialists who are directly implicated in carrying out the act, we also need more of the latter type of study.

The analysis of results from both kinds of study generates a more favorable view of euthanasia among healthcare professionals than among the general population. Thus, in 2019, 71.2% of the Spanish population was in favor of euthanasia, a percentage that rose to 83% among the medical profession (Bernal-Carcelén, 2020). In both groups, support for euthanasia tends to be sustained by two kinds of arguments: (1) individual autonomy in decision-making about the end of life; and (2) the desire to end unbearable suffering in situations of incurable illness. In the case of healthcare professionals, these arguments take on greater strength, to a large extent because they are inspired by specialist knowledge, as well as deontological principles and/or professional codes of conduct (Vijayalakshmi et al., 2018).

Studies of moral stances on and attitudes to euthanasia and assisted dying in Spain point to a majority consistency in positions both in favor and against. In other words, people who justify one of these acts usually also justify the other, using the same moral argument or the same value for it (Serrano del Rosal and Heredia Cerro, 2018; Rodríguez-Calvo et al., 2019). As a result, it appears that the moral stance on the disposability of life itself is an associated factor in the position in favor or against.

Cohen et al.'s (2014) analysis of attitudes to euthanasia in countries in the European region concluded that in much of Europe the public acceptance of euthanasia was relatively low or moderate. Denmark, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, and Sweden were among the countries with the highest levels of support, and Kosovo, Cyprus, Turkey, Georgia, and Armenia were among those least favorable to euthanasia. The greatest rise in support for euthanasia between 1999 and 2008 occurred in Spain, Portugal, Great Britain, Germany, and Italy, while the main decrease was found in the Russian Federation, Ukraine, Greece, the Slovak Republic, and Belarus. The study suggests a tendency toward polarization in Europe, with an inclination toward greater permissiveness in most of Western Europe and less permissiveness in most of Eastern Europe (Cohen et al., 2014). In the case of Germany, it is possible that the change of name had an impact on this increase, as the term “euthanasia”—used during National Socialism to designate the non-voluntary killing of disabled or mentally handicapped persons—was replaced in 2008 by “Sterbehilfe” (assisted suicide). Hence the observed change might partly be caused by the reformulation of the question.

Individual factors

In almost all the studies we reviewed, both from Spain and from elsewhere, the fundamental variable that distinguishes the population's attitudes toward the regulation of euthanasia is self-positioning in relation to religion: those people who consider themselves to be non-religious are the ones most in favor of euthanasia (Cohen et al., 2014; Serrano del Rosal and Heredia Cerro, 2018; Pentaris and Jacobs, 2020). As has been noted, this relationship is consistent with the strong association between favorable attitudes to euthanasia and tolerance toward personal freedom (Cohen et al., 2014).

Other variables analyzed in the studies include sex, age, and level of education. However, there does not appear to be a clear association between these factors and attitudes toward euthanasia.

With regard to the gender variable, studies yield different results. Some investigations reject any significant association (Rodríguez-Calvo et al., 2019), while others find a greater opposition to euthanasia among women (Vijayalakshmi et al., 2018; Pentaris and Jacobs, 2020). Where there does appear to be an acceptance of euthanasia is among people who identify as non-binary, transgender, or intersex (Pentaris and Jacobs, 2020). This could suggest that what is at issue goes beyond identity to a particular conception of life and freedom.

As for age, research has identified the association of old age with unfavorable attitudes to euthanasia. But even here, this connection may be less the result of age than the impact of the greater representation of religiosity among older people (Roesinger et al., 2018). Furthermore, authors such as Durán (2004) indicate that the greater degree of reflection on death among older people, or the comorbidity or deteriorating health that often accompanies old age, could suggest a greater acceptance of euthanasia (Yun et al., 2022).

As for the level of education, some studies have concluded that the higher the level, the greater the support for euthanasia (Hendry et al., 2013). However, some authors have identified this association only among people who are not religious (Serrano del Rosal and Heredia Cerro, 2018).

It appears that socio-demographic variables are no longer associated to attitudes to euthanasia, and instead it is considered to be an act of personal freedom (Cohen et al., 2014), just as religiosity and political opinions might be.

In this regard, Terkamo-Moisio et al. (2017) speak of a break in the traditional model of support for euthanasia, according to which neither age nor level of education are indicator factors in attitudes toward it, beyond the influence of the religiosity variable. This hypothesis has also been proposed (Hendry et al., 2013) with respect to ethnicity. Even regarding religiosity, in the case of European regions, “the larger division within the Catholic population is probably due to exposure to a wider variety of national and regional influences than are other major religions, which are more concentrated within specific European regions. A person's position toward euthanasia, whether Catholic, Protestant, or not religious, thus seems to be much more determined by the dominant culture within a country than by doctrinal religious stances of the denomination one associates with De Moor (1995). People, religious or not, living in countries in which other people's right to selfdetermination is generally accepted, e.g., with regard to personal choices regarding sexuality, life and death, are for instance usually also more accepting of euthanasia as an option for incurably ill people” (Cohen et al., 2014, p. 151).

In Spain, the study “Abortion and Euthanasia” produced by CIS (1992), put for the thesis that in all segments of society a majority holds favorable views toward euthanasia. In another study conducted in 2003, the same author concluded that there is no group (by age, sex, social situation, ideology, socio-economic status, family, type of habitat, level of exposure to media, political orientation, level of satisfaction with the government, or party supported in the previous elections) that demonstrates a total rejection of euthanasia (Durán, 2004).

Contextual and cultural factors

What is the situation, then, in relation to abortion? In an analysis of incidences of voluntary interruptions to pregnancy, we can distinguish three categories in European countries:

1) Countries with a reliable system of voluntary interruption of pregnancy (e.g., Estonia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, and other Nordic countries).

2) Countries which have designed a limited supervised system (e.g., France, Spain, Italy, Poland, and the Commonwealth of Independent States).

3) Countries with no supervised system (e.g., Austria, Greece, Luxembourg, and Portugal) (Lazdane, 2005).

It must be noted that the situation in relation to abortion has undergone a gradual change, especially during the final decades of the twentieth century. With the advance of technology and the recognition of women's rights, couples and women now have a greater level of autonomy when it comes to choices concerning their fertility. As a result of this autonomy, Dutch women, for example, have the lowest rates of voluntary interruption of pregnancy.

If we compare the rate of abortion in different countries, it is clear that those with the lowest rates are the countries whose requirements are more oriented toward women's needs and where women have greater autonomy to access sex education, contraception, and the voluntary interruption of pregnancy, for example, in the Netherlands (Fiala, 2005). In this sense, it has been proven that countries with high income levels in which abortion is totally legal have the lowest level of undesired pregnancies, abortion, and proportion of undesired pregnancies that end in abortion (Bearak, 2020).

In contrast, some countries still maintain legislation that reflects antiquated procedures that have not been adapted to meet medical and social developments. Countries such as Poland, Malta, and Ireland requested additional dispensations when they signed their declarations for access to the European Union. These clauses permit them to reserve the right to make, under any circumstances, all decisions concerning legislation on the voluntary interruption of pregnancy. A strong opponent of all points collected in the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) Program of Action is the Vatican, which has a great deal of influence in many Catholic countries, as well as important supporters in Brussels.

Portugal has very restrictive legislation in relation to abortion, only recognizing legal presumptions in the case of risk to the health or life of the woman, fetal deformity, or if the pregnancy is a result of rape. Even within these legal presumptions, women are frequently denied the right to voluntarily interrupt their pregnancies because health professionals are not prepared to face the social pressure around this issue (Hägele, 2005).

The results of numerous investigations (Bearak, 2018) indicate that people seek abortions even in settings in which it is restricted. For this reason, it is necessary to analyze the obstacles (social, economic, cultural and political) that many women must face. In this sense, together with factors such as stigma, geographical factors and interregional migration, the implementation of gynecologists' conscientious objection on abortion regulation can lead to a inequal access to abortion facilities in countries where abortion is legal and included in the public health system (Autorino et al., 2020). These results highlight the importance of guaranteeing access to the entire range of sexual health and reproductive services, including contraception and attention to abortion, and providing additional investment in order to achieve equity in healthcare services. Research also emphasizes the need to reach the objectives of the Global Strategy for Women's, Children's, and Adolescent Health, as well as those of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and universal healthcare coverage.

In any case, as numerous authors have indicated (Sedgh, 2016), more studies are required on women's and couple's decision-making in the face of undesired pregnancy in different legal environments and sociocultural contexts, so that we can improve our understanding of the factors that influence the decision to have an abortion.

Methodology

The sample

The Deusto Social Values team represents Spain in the European Values Study (EVS) and has formed part of this consortium since 1990, participating in all the waves of the EVS. The most recent EVS wave was conducted between December 2017 and January 2018, with the participation of 34 European countries.

The design sample of the European Values Study in its application in Spain has been done in such a way that all people over 18 who live in the country can appear in the sample, with no age limit. Technical details of the survey in Spain: 1,212 survey, for a confidence level of 95%, and assuming the maximum variability of the population p = q = 0.5, the sampling error for the sample as a whole is + 2.81%. In the 1981, 1990, and 2008 waves sex and age quotas were applied when making the sample, but from 2008 onwards the sample method has had to as be as random as possible within the economic means of the study. The best recommended strategy for randomization has been to use census data, with the aim of assuring that all individuals on the list have an equal chance of being selected. For reasons of cost and privacy, we opted for the design of randomized paths based on the number of interviews conducted in each autonomous region and by size of habitat.

The definition of the paths, the procedure for selecting the building, building number, floor, apartment number, and person to interview was also entirely established and agreed, in the first instance, between the researchers and principal researchers (PIs) of each country and the methodological team of the European Values Study. The EVS methodology has been greatly strengthened for the current wave to bring the quality of the data to a high level. Each national survey conforms to guidelines designed to ensure quality and consistency (EVS, 2020).

As in addition to Spain we will describe and compare the results with other European countries as well as with the European total. So, we should point out that all the countries are considered in the same way, regardless of their size, since the complete sample is already weighted by the EVS methodological team, making it a representative sample for each country, as well as for Europe.

The total sample has been obtained from the sum of the samples of each country, all of them being representative with samples of more than 1,000 persons. The final total sample is weighted according to the size of each country, by the EVS methodological team1. The weights included in the full release of EVS data are two versions of calibration weights, a population size weight and—for a limited number of countries—a design weight. For the countries where it is provided the design weight has not been factored in the computation of calibration weights.

The results

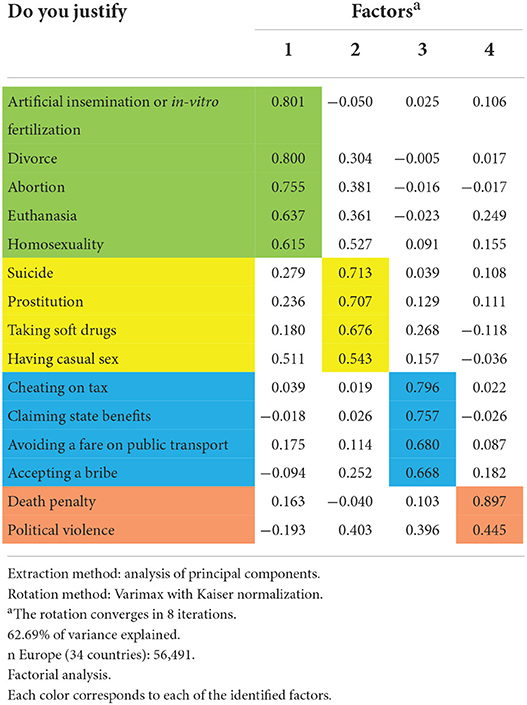

This is a descriptive study. In the first table we use descriptive statistics to compare means (t-test), then we carry out a factor analysis of principal components in relation to the justification of certain behaviors.

Principal components factor analysis was carried out with SPSS. We have followed the criteria of our previous studies for Spain and Europe (Elzo and Silvestre, 2010; Silvestre, 2020), and the explanation of the variance and have finally selected 4 factors. In the case of Europe, the four-factor solution provides a 63% of explanation of the variance. The factor loadings of each factor are high (over 0.5). In the case of Spain, the factorial reaches 70% of variance explained.

The orthogonal rotation method was used both because it minimizes the number of variables that have high saturations in each factor, and because it simplifies the interpretation of the factors by optimizing the solution per column. The varimax rotation method is also the one we have used in previous studies. In addition, in empirical research orthogonal rotations have been implemented frequently (Fabrigar et al., 1999; Conway and Huffcutt, 2003; Costello and Osborne, 2005).

Analysis of results

Incidence of sociodemographic variables

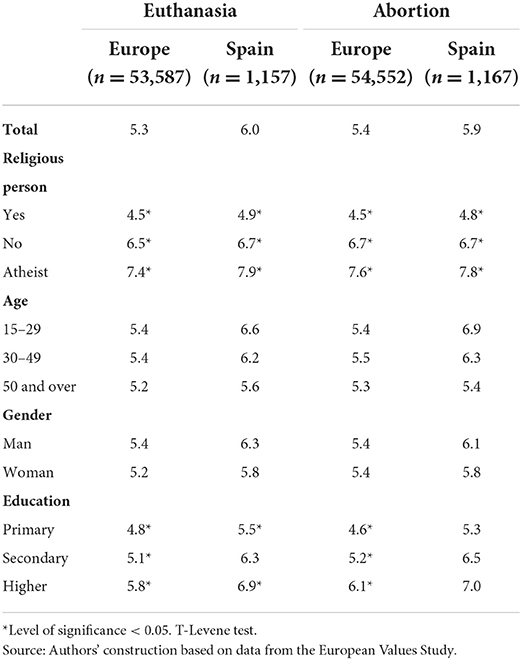

In Table 1 our objective is to establish whether there is an association between a series of socio-demographic or independent variables (age, gender, religion, and education) and the justification of abortion and euthanasia. The result obtained is that religion is the most significant variable when it comes to justifying or not justifying any of these behaviors.

Table 1. Justification of euthanasia and abortion in Europe and Spain (averages on a scale of 1 never to 10 always).

The average point in the justification of both euthanasia and abortion is located in the intermediary values close to acceptance (5.5) in Europe as well as Spain, and is almost one point higher in the case of Spain for both acts (5.3 for euthanasia and 5.4 for abortion in Europe; 6.0 for euthanasia and 5.9 for abortion in Spain). Thus, we can confirm that the justification of one goes hand-in-hand, in the majority of cases, with justification of the other. It is possible to detect, therefore, an important ideological consistency.

The two most significant variables for a greater or lesser justification of both acts among the European and Spanish population is, beyond any doubt religiosity, and, to a lesser degree, level of education.

With regard to religiosity, we can confirm that being a religious person is the most significant factor associated to NO justification of abortion and euthanasia, in Europe as well as Spain. Religious people2 do not justify either abortion or euthanasia as a general norm, and they give both acts a justification with an average lower than 5, while people who are not religious justify both acts, with a point that varies between 6.5 for euthanasia in Europe and 6.7 for abortion in Spain. This means a general average (abortion + euthanasia) of 2.1 points higher among non-religious people than religious people in Europe, and a difference of 1.8 points in Spain. Moreover, in Europe as well as in Spain, atheists are those who justify both acts to the greatest extent, reaching an average level in the justification of euthanasia of 7.9 in Spain and 7.4 in Europe, and 7.8 and 7.6, respectively, in the justification of abortion. Therefore, in the case of atheists, there is a general average (abortion + euthanasia) difference of 1 point in relation to non-religious people and 2.9 in relation to religious people, both in Spain and in Europe.

Level of education is also a factor that influences the justification of both acts. People with higher levels of education justify abortion and euthanasia more than those with lower levels. In this case, the influence of educational level is higher in Europe than in Spain. In Europe, people with only primary-level education generally do not support either euthanasia (4.8) or abortion (4.6). This is in contrast to people with secondary- and higher-level education, who justify these acts with points that vary between 5.1 in the case of people with secondary-level studies for euthanasia, and 6.1 in that of people with higher education for abortion. The average general justification in the case of people with higher education is 0.8 points above the general average (abortion + euthanasia) in the case of secondary-level education, while the difference of averages between secondary- and primary-level education is 0.4. In Spain, people justify both acts with an average of more than 5. The levels vary between 5.5 for euthanasia in the case of people with primary education and 7.0 for abortion in the case of people with higher education. In this case, the general average difference (abortion + euthanasia) is 1 point higher for secondary-level education compared to primary level, and 0.5 points more for higher-level education compared to secondary level.

In addition to religiosity and level of education, age and gender are also associated to the justification of abortion and euthanasia, though to a lesser degree. Thus, in Europe the justification among people of middle age is only slightly above that of the other age groups, for both euthanasia (5.4 in contrast to 5.4 among the younger population group, and 5.2 among the older group) and abortion (5.5 as opposed to 5.4 among the younger group, and 5.3 among the older part of the population). In Spain, however, justification decreases with age, so that younger people are the group that justify both acts more clearly. In the case of euthanasia, young people between 15 and 29 give the average point of justification as 6.6 (as opposed to 6.2 in the middle-aged population and 5.6 among the older group), and in the case of abortion, 6.9 (as opposed to 6.3 and 5.4, respectively). As we can see, the difference is notable, exceeding the justification of the older age group by 1 point.

With respect to gender, in general men justify euthanasia and abortion to a slightly higher degree than women: 0.2 in Europe and 0.5 in Spain for euthanasia, and 0.0 and 0.4, respectively, for abortion.

Taking into account everything we have said so far, we can say that in Europe and in Spain those who justify both abortion and euthanasia the least are people who are religious, older, women, and with primary- (and, to a lesser degree, secondary-) level education.

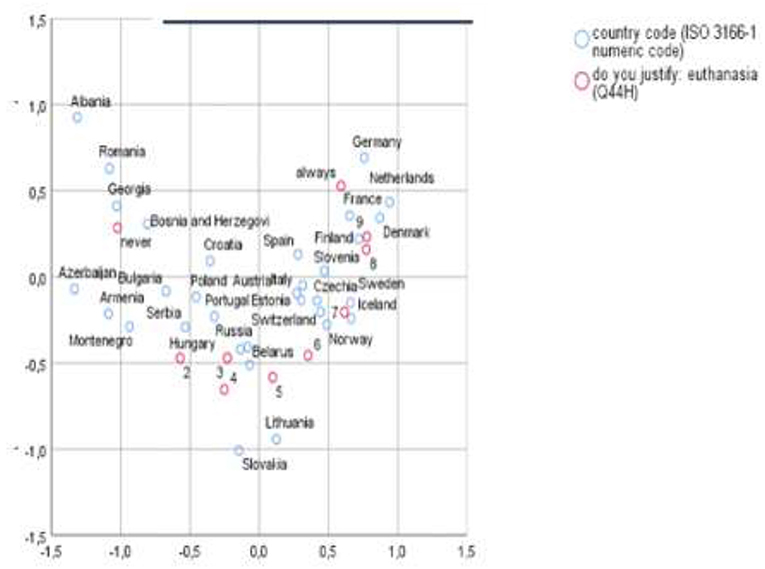

Analysis of correspondences: Comparison by country

The comparative analysis by country confirms what the literature had already put forth in previous studies on attitudes and behavior in relation to euthanasia and abortion: there is a division between a large proportion of the countries in Eastern and Western Europe. In Figure 1, we show the relationship between the variables country and the justification of euthanasia. Thus, the diagram shows how each country is positioned in terms of a greater or lesser justification of euthanasia.

Figure 1. Analysis of correspondences: Justification of euthanasia. Source: Authors' construction based on data from the European Values Study (coordinates are symmetrical).

We can see that countries such as Albania, Romania, Georgia, and Bosnia Herzegovina are clustered around rejection (“never”), while clustered around full justification (“always”) we find countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, and France. The countries that break with this rule are Slovenia and the Czech Republic, which have high levels of justification of euthanasia.

Euthanasia legislation in Europe can provide some clues to approaching the interpretation of the comparative analysis. Few countries have legislated in favor of euthanasia, and those that have done so have developed different norms. The Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and, most recently, Spain (in 2022, 20 years after the Netherlands) have legalized euthanasia and permitted “assisted dying.” The Netherlands registers the highest average value of justification for euthanasia (7.47) and the average in Spain is 5.99 (there is no data for either Belgium or Luxembourg in the last EVS). Other Central European countries, such as Switzerland, Germany, and Austria, do not allow active euthanasia, but do permit passive euthanasia as long as the person who is ill has expressed that will. Passive euthanasia—when a patient with an irreversible illness is allowed to die as a consequence of the suspension of medical treatment—is also recognized in law under certain conditions in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland. All these countries record levels of justification of euthanasia above the European average.

At the other extreme, countries such as Poland, Bulgaria, and Croatia consider euthanasia to be murder or a criminal offense, punishing it with prison sentences between 5 and 8 years. In these countries there are very low levels of justification of euthanasia, with averages well under the European average: Bulgaria (3.76), Poland (4.22), and Croatia (4.58). But there is not always a relationship between the justification of euthanasia and the legislative framework; in France, for example, where euthanasia is not permitted, the justification of it is quite high, with one of the highest averages in Europe (6.9).

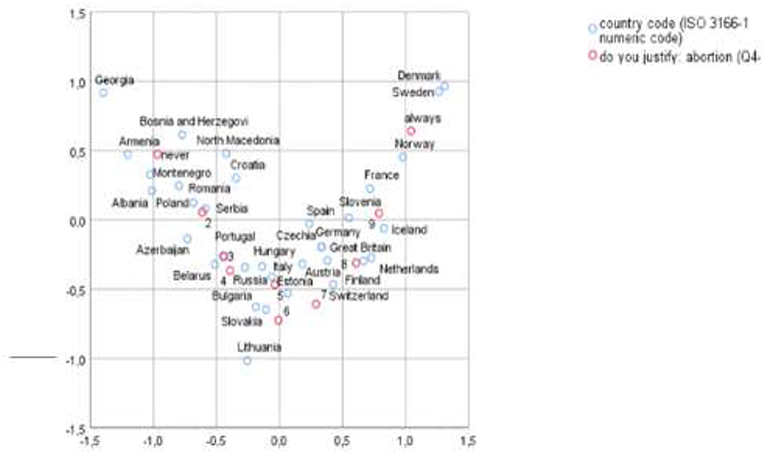

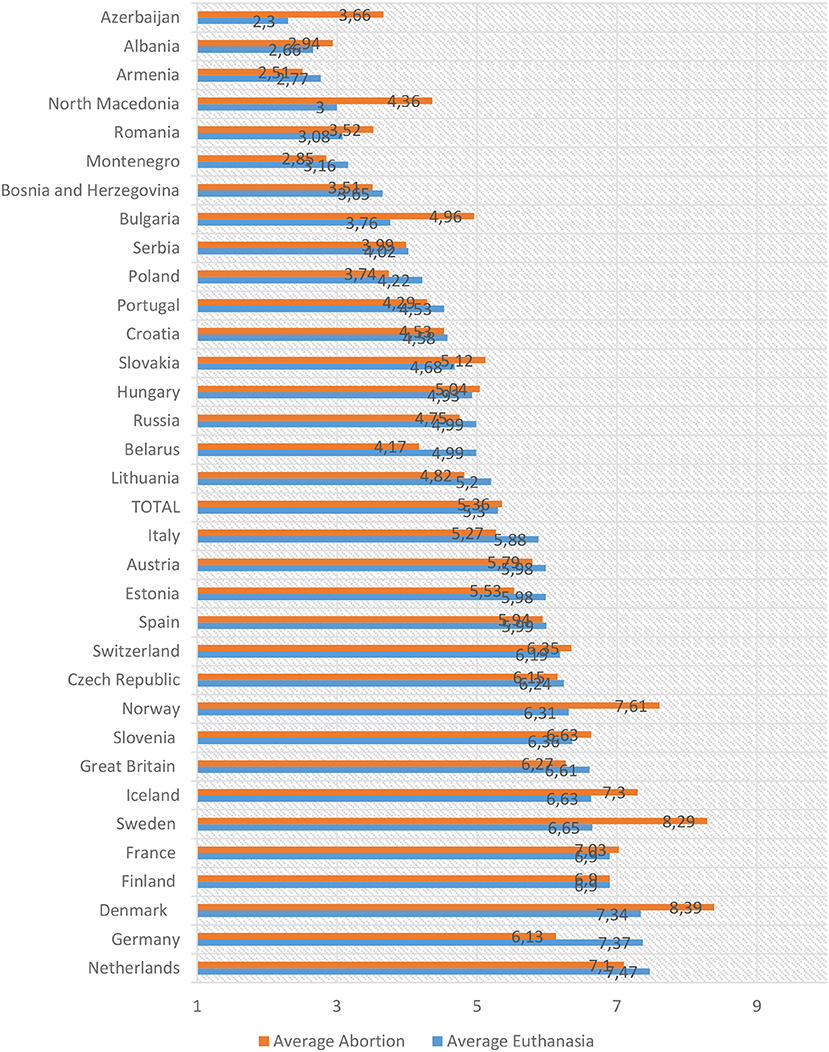

In Figure 2, we show the relationship between the variables country and the justification of abortion. Thus, the diagram shows how each country is positioned in terms of a greater or lesser justification of euthanasia.

Figure 2. Analysis of correspondences: Justification of abortion. Source: Authors' construction based on data from the European Values Study (coordinates are symmetrical).

The comparative analysis in relation to the level of justification of abortion provides a very similar map to that for euthanasia, showing signs of a relationship and parallelism between the two attitudes among European citizens (see Figure 3). Here, once again, the former Soviet republics are those that demonstrate the greatest rejection of abortion. We refer to countries such as Georgia, Armenia, Bosnia Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Romania, Albania, and Poland (Poland has one of the most restrictive abortion laws in the European Union, since the country only permits the interruption of pregnancy in order to save a woman's life, that is, when there is a grave threat to the mother's health). At the opposite pole are situated the Nordic countries, such as Denmark and Norway (in Norway it is possible to abort during the second trimester if socioeconomic reasons are presented).

Figure 3. Justification of euthanasia and abortion. Mean by country (1 never and 10 always). Source: Authors' construction based on data from the European Values Study.

Two special cases are Portugal, which demonstrates attitudes closer to those of the former Soviet republics mentioned above, and Slovenia, since it is closer to the Western countries. This is something that we noted in the cases of the justification of euthanasia as well as abortion. It should be mentioned that a in Portugal a popular vote did not pass a law for euthanasia in 2018; the country also has limitations in the case of abortion.

The study of the position of Spain in relation to other European countries confirms that the analysis of these values challenges the idea that there exists something called the “South of Europe.” This is because the levels of justification of euthanasia and abortion in the Spanish case are much closer to the attitudes in Central European countries such as Switzerland, the Czech Republic, Germany, Austria, and the Netherlands.

Factorial analysis: The Eros/Thanatos grouping

The question in the European Values Study that gathers information on the justification of euthanasia and abortion presents a series of behaviors that are subject to the degree of justification among the European population. It is interesting to gather these behaviors together according to the level of justification because, as we have seen in recent decades (Elzo and Silvestre, 2010; Silvestre, 2020), the way in which the factors take shape allows us to explore the perception and association of actions such as euthanasia and abortion in the European imagination. In what follows, we present the results of the factorial analysis applied to the whole of the base of the European data (Table 2).

First, we can identify a Factor 1, “Eros/Thanatos,” which encompasses behaviors related to the life/death relationship and to sexuality: artificial insemination or in-vitro fertilization, divorce, abortion, euthanasia, and homosexuality.

Factor 2, “Outside the norm,” brings together a series of behaviors that, while in some cases also take us back to death (suicide, for example), share the fact of being criminal acts, falling outside the norm and being, in one way or another, pernicious or risky. This second factor groups together issues such as suicide, prostitution, soft drug use, and casual sex.

Factor 3, “Civility,” brings together a series of behaviors that threaten the common good and governance, and are related to corruption: tax evasion, claiming state benefits, avoiding a fare on public transport, and accepting a bribe.

Finally, Factor 4, “Institutional violence,” includes the death penalty and police violence.

Europe does not relate euthanasia and abortion to either suicide or the death penalty; these are cases of behaviors clearly related to life/death and that are subject to a different valuation, perception, and, therefore, justification. Once again, the idea is reinforced that there are ideological patterns behind this kind of justification.

This grouping of Factors is constant over time and is present in the majority of European countries. In some countries, “homosexuality” falls on the side of Factor 2. This happens where homosexuality is repressed or directly forbidden, for example in the case of Russia. The factorial analysis applied to Spain gathers some differences in the association of variables: “having casual sex” is included in Factor 1 and “avoiding a fare on public transport” appears in Factor 2 instead of Factor 3 (see the Appendices).

Final discussion and reflections

The results of our investigation corroborate the conclusions of previous research. We have ratified the claim that there is an ideological consistency in the justification of euthanasia in relation to the justification of abortion, as has been established in other studies (Roesinger et al., 2018; Serrano del Rosal and Heredia Cerro, 2018; Rodríguez-Calvo et al., 2019).

This ideological consistency, which takes us back to moral principles, is closely connected to the degree of religiosity among citizens. As such, we have observed, similarly to existing studies (Roesinger et al., 2018; Serrano del Rosal and Heredia Cerro, 2018; Vijayalakshmi et al., 2018) that not being a religious person is the principal explanatory factor for the greater justification of abortion and euthanasia, in Spain as well as in Europe generally.

We have shown that there is an association between religiosity and the justification of euthanasia and abortion. The process of secularization experienced in Western Europe in recent decades and, above all, in Southern Europe (Halman and Draulans, 2004; Finke and Adamczyk, 2008; Halman and van Ingen, 2013, 2015), could explain the favorable position in relation to euthanasia in countries such as Spain. In the case of some former Soviet republics, in contrast, the revival of religious practice after the fall of communism could also explain, in part, the positioning of countries such as Georgia, Hungary, and Poland. As Nelly Bekus and Michal Wawrzonek rightly note, “in the post-communist societies of Eastern Europe, the political dynamic of liberation from totalitarian ideology was accompanied by the return of religion to public life after decades of suppression” (Vavzhonek et al., 2016, p. 2). The authors relate this issue to cultural legacies, symbolic capital, and national freedom, which could very well influence the justification given to euthanasia and abortion.

Level of education and age have also been shown to be significant, though to a lesser degree. These elements have also been collected in other studies. Serrano del Rosal and Heredia Cerro (2018) had already noted the importance of older age in positioning against the regulation of euthanasia, and Roesinger et al. (2018) associated this precisely with the greater level of religiosity felt among the older population.

We began this article by proposing a possible relationship in levels of justification of euthanasia and abortion, stemming from the connection to the level of individual freedom granted in a given society and what it permits in relation to the binomial life/death. We have confirmed that the moral positioning toward the disposability of life itself is a key explanatory factor. This moral positioning is closely related to the level of individual religiosity demonstrated and the weight of religion in a given society; for that reason, processes such as secularization in Western Europe or the rise in institutional religion in the former Soviet republics provide some explanatory indicators. Similarly, legislation, as a result of the normative application and practice of said moral positioning, also appears to have a significant influence on levels of justification of euthanasia and abortion. However, this is not a generalizable relationship or one of cause-and-effect, because previous attitudes may have acted as a form of pressure to create a certain normative framework, or the legal framework could be far removed from the views of the majority.

Morality and how it defines in social terms the limits of our individual freedom over our bodies (when it comes to ending life or interrupting a pregnancy) are keys to understanding the different positionings in Europe. At the individual level, religiosity, level of education, and age are shown to be explanatory sociodemographic variables: where there is a higher level of religiosity, older age, and a lower level of education there will be less justification of euthanasia and abortion.

We have also established that euthanasia and abortion are related to behaviors such as in-vitro insemination, divorce, and homosexuality, questions that we have located in the Factor named Eros/Thanatos. We can confirm that within this factor there also exists a certain degree of personal autonomy or exercise of individual freedom when it comes to taking certain decisions of personal significance. In contrast, euthanasia and abortion are not related to either suicide or the death penalty, issues that are more connected to risk or violence.

We have observed that different degrees of justification of euthanasia and abortion divide Europe in two. There are clear differences between Western Europe and Eastern Europe. The first demonstrates greater levels of justification, while the second expresses a greater rejection of both behaviors.

European countries tend to justify abortion somewhat more than euthanasia. In this sense, we can confirm that in Europe the legislation surrounding the interruption of pregnancy is more extensive and more current than the legislation relative to the interruption of life. Spain, however, tends to justify abortion somewhat less than euthanasia, especially in the case of men, people over 50, and those with only a primary-level education.

Our study is descriptive, but it shows that there are personal and contextual conditioning factors, such as the degree of religiosity, legislation, and the welfare model, which affect the degree of justification of two behaviors related to the exercise of individual freedom: euthanasia and abortion. Nevertheless, even a personal factor such as religiosity is influenced by culture. The challenge for future research is to propose explanatory analyses that provide information on which factors have the greatest impact on levels of justification in Europe, whether these are individual or cultural issues.

Data availability statement

Data can be found at https://europeanvaluesstudy.eu/.

Author contributions

The theoretical framework relating to abortion and the exploitation of the data was developed by IA. The theoretical framework relating to euthanasia was written by UB. Factorial and correspondence analysis was developed by MS. Introduction, final discussion, and reflections have been prepared jointly by IA, UB, and MS. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The authors belong to the Deusto Social Values Team recognized as a team of excellence by the Basque Government and received support both through this call and through the contract-program of the University of Deusto.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.966711/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^https://europeanvaluesstudy.eu/methodology-data-documentation/survey-2017/methodology/

2. ^In the EVS a “religious person” is a person who defines him/herself as such, regardless of his/her religious practice and regardless of whether he/she professes a traditional religion (Catholic, Jewish, Muslim, Protestant, etc.) or believes in matters more related to spirituality.

References

Autorino, T., Mattioli, F., and Mencarini, L. (2020). The impact of gynecologists' conscientious objection on abortion access. Soc. Sci. Res. 87, 102403. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2020.102403

Bearak, J. (2018). Global, regional, and subregional trends in unintended pregnancy and its outcomes from 1990 to 2014: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet Global Health 6, 380–389. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30029-9

Bearak, J. (2020). Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990–2019. Lancet Global Health 8, 1152–1162. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30315-6

Bernal-Carcelén, I. (2020). Euthanasia: trends and opinions in Spain. Revista Española De Sanidad Penitenciaria 22, 112. doi: 10.18176/resp.00020

Cohen, J., Van Landeghem, P., Carpentier, N., and Deliens, L. (2014). Public acceptance of euthanasia in Europe: a survey study in 47 countries. Int J Public Health 59, 143–156. doi: 10.1007/s00038-013-0461-6

Conway, J. M., and Huffcutt, A. I. (2003). A review and evaluation of exploratory factor analysis practices in organizational research. Organ. Res. Methods 6, 147–168. doi: 10.1177/1094428103251541

Costello, A. B., and Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assessment Res. Evaluat. 10, 7.

Durán, M. (2004). La calidad de muerte como componente de la calidad de vida. Revista Española De Investigaciones Sociológicas 106, 9–32. doi: 10.2307/40184583

Elzo, J., and Silvestre, M. (2010). Un individualismo placentero y protegido: cuarta encuesta europea de valores en su aplicación a España. Bilbao: Universidad de Deusto.

EVS (2020). European Values Study (EVS) 2017: Methodological Guidelines. (GESIS Papers, 2020/13). Köln: European Values Study.

EVS (2022). European Values Study 2017: Integrated Dataset – Sensitive Data (EVS2017 Sensitive Data). GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA7501 Data file Version 2.0.0.

Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., and Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol. Methods 4, 272–299. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.4.3.272

Fiala, C. (2005). El aborto en Europa: La legislación y la práctica están centradas en la paciente? Entre Nous 59, 23–26. Available online at: https://www.inmujeres.gob.es/areasTematicas/salud/entreNous/docs/EntreNous59.pdf

Finke, R., and Adamczyk, A. (2008). Cross-national moral beliefs: the influence of national religious context. Sociol. Q. 49, 617–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2008.00130.x

Hägele, M. (2005). Derechos sobre salud sexual y reproductive en la Unión Europea. Entre Nous 59, 26–29. Available online at: https://www.inmujeres.gob.es/areasTematicas/salud/entreNous/docs/EntreNous59.pdf

Halman, L., and Draulans, V. (2004). “Religious beliefs and practices in contemporary Europe,” in European Values at the Turn of the Millennium, eds W. Arts and L. Halman (Boston: Brill), 283–316.

Halman, L., and van Ingen, E. (2013). “Secularization and the sources of morality: religion and morality in contemporary Europe,” in Religion and Civil Society in Europe, eds J. De Hart, P. Dekker, and L. Halman (New York: Springer), 87–108.

Halman, L., and van Ingen, E. (2015). Secularization and changing moral views: European trends in church attendance and views on homosexuality, divorce, abortion, and euthanasia. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 31, 1–12 doi: 10.1093/esr/jcv064

Hendry, M., Pasterfield, D., Lewis, R., Carter, B., Hodgson, D., and Wilkinson, C. (2013). Why do we want the right to die? A systematic review of the international literature on the views of patients, carers, and the public on assisted dying. Palliat. Med. 27, 13–26. doi: 10.1177/0269216312463623

Lazdane, G. (2005). Aborto en Europa: diez años después del Cairo. Entre Nous 59, 4–7. Available online at: https://www.inmujeres.gob.es/areasTematicas/salud/entreNous/docs/EntreNous59.pdf

Pentaris, P., and Jacobs, L. (2020). UK public's views and perceptions about the legalisation of assisted dying and assisted suicide. OMEGA J. Death Dying. 1–15. doi: 10.1177/0030222820947254

Rodríguez-Calvo, M. S., Soto, J. L., Martínez-Silva, I. M., Vázquez-Portomeñe, F., and Muñoz-Barús, J. I. (2019). Actitudes hacia la eutanasia y el suicidio medicamente asistido en estudiantes universitarios españoles. Revista Bioética 27, 490–499. doi: 10.1590/1983-80422019273333

Roesinger, M., Prudlik, L., Pauli, S., Hendlmeier, I., Noyon, A., and Schäufele, M. (2018). Einflussfaktoren auf die positionierung gegenüber sterbehilfe. Zeitschrift Für Gerontologie Und Geriatrie 51, 222–230. doi: 10.1007/s00391-016-1159-1

Sedgh, G. (2016). Abortion incidence between 1990 and 2014: global, regional, and subregional levels and trends. Lancet 388, 258–267. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30380-4

Serrano del Rosal, R., and Heredia Cerro, A. (2018). Actitudes de los españoles ante la eutanasia y el suicidio médico asistido. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 161, 103–20. doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.161.103

Silvestre, M. (2020). Valores en la era de la incertidumbre: individualismos y solidaridades. Quinta encuesta europea de valores en su aplicación a España. Madrid: Ediciones La Catarata.

Terkamo-Moisio, A., Kvist, T., Laitila, T., Kangasniemi, M., Ryynänen, O., and Pietil,ä, A. (2017). The traditional model does not explain attitudes toward euthanasia: a web-based survey of the general public in Finland. OMEGA J. Death Dying 75, 266–283. doi: 10.1177/0030222816652804

Vavzhonek, M., Bekus, N., and Korzeniewska-Wiszniewska, M. (2016). Orthodoxy Versus Post-Communism?: Belarus, Serbia, Ukraine and the Russkiy Mir. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Vijayalakshmi, P., Nagarajaiah Reddy, P. D., and Suresh, B. M. (2018). Indian nurses' attitudes toward euthanasia: gender differences. OMEGA J. Death Dying 78, 143–160. doi: 10.1177/0030222816688576

Keywords: euthanasia, abortion, values, religion, personal freedom

Citation: Silvestre M, Aristegui I and Beloki U (2022) Abortion and euthanasia: Explanatory factors of an association in Thanatos. Analysis of the European Values Study. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:966711. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.966711

Received: 11 June 2022; Accepted: 10 October 2022;

Published: 28 October 2022.

Edited by:

Hermann Duelmer, University of Cologne, GermanyCopyright © 2022 Silvestre, Aristegui and Beloki. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria Silvestre, bWFyaWEuc2lsdmVzdHJlQGRldXN0by5lcw==

Maria Silvestre

Maria Silvestre Iratxe Aristegui

Iratxe Aristegui Usue Beloki

Usue Beloki