95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 28 October 2022

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.946985

This article is part of the Research Topic "Performing Control" of the Covid-19 Crisis View all 12 articles

Social media has created new public spheres that provide alternative sources of social and political authority. Such “digital authority” has conventionally been interpreted in metric terms, without qualitative distinctions. Based on Twitter data from four different Swedish state agencies during the first 15 months of the COVID-19 crisis, this paper looks at the different kinds of modes of interaction Twitter enables and their impact on state agencies digital authority. Theoretically this paper applies Valentin Voloshinov's classical theory on reported speech, developed in the 1920s, to the concept of digital authority in the Twitter-sphere of the 2020s. Besides these theoretical contributions to media and communication studies, the main findings are that retweets are generally used to affirm and spread information thus strengthening the digital authority of the origin of the tweet whilst replies and quote-tweets are used to undermine the credibility of the sender and the content of the original tweet, often by resorting to irony. As the COVID-19 crisis prolongs, we observe increasing share of critical commentary and diminishing overall attention to government actors in Sweden. The roles of different state agencies are mirrored by the type of interaction they generate. This article also shows the usefulness of qualitative study of social media interaction in order to reveal the dynamics of digital authority construed in social media.

Crises, such as those that arose from and were performed against the background of the COVID-19 pandemic, call for leadership (Alexander, 2015; Brubaker, 2021). German conceptual historian Koselleck saw in the concept of crisis a breach in the temporary flow of things (Koselleck, 2006). Indeed, the word crisis etymologically refers to a radical opening in the normal way of life, requiring decisions concerning the future course of action (Kornberger et al., 2019). Crisis situations provide opportunities for state agencies to pool power and gain authority. But while crises certainly tend to increase the support for incumbents (Murray, 2017), efficient crisis management does not necessarily require centralized leadership. In Sweden, with its long history of decentralized governance, a distribution of power as well as a “scientization of politics” are considered desirable during crises (Jacobsson et al., 2015; Eyal, 2019, p. 97). In fact, much of the alleged Swedish exceptionalism during the COVID-19 pandemic can be traced back to a system of crisis management that emphasizes the role of politically independent experts and legal circumstances that favor voluntary recommendations over legally sanctioned measures (Baldwin, 2020; Ludvigsson, 2020; Pierre, 2020).1 Historically, the reliance on recommendations and voluntary compliance, rather than rules and laws, has led to—and was in turn made possible by—high levels of trust in government agencies among the population (Rothstein, 2002; Esaiasson et al., 2021). However, there are indications that this universal trust is becoming brittle, at least amongst those in vulnerable socio-economic positions (Holmberg and Rothstein, 2020, p. 10; Hassing Nielsen and Lindvall, 2021).

Sweden's decentralized governance gives crisis communication a central position in the everyday experience of legitimate state authority and leadership during periods such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, two of the agencies responsible for the pandemic policies have their primary task as communication (Krisinformation) and coordination (MSB). In this context, the increasing role of social media has arguably changed how authority is experienced and reacted to Kornberger et al. (2018) and Turunen and Weinryb (2020). A digital public space has emerged that needs to be reckoned with in its own right (Bernard, 2019; Casero-Ripollés, 2021). Gortitz et al. (2020) argue that an analysis of political authority of leadership in modern societies must consider the “digital authority” of respective state agencies. They take the amount of interaction different actors can elicit as an indicator of digital authority. Following Valentin Voloshinov's theory of different forms of reported speech [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930)],2 we contest this merely quantitative definition and argue in the following that not all types of (Twitter) interaction indicate digital authority. Some forms convey and create distrust, pointing toward a contest between more established legal-rational and change-seeking charismatic types of authority in the sense of Weber's (2019) typology.

The objective of this article is four-fold. First, to provide a more elaborated concept of digital authority. Second, to analyse how this authority has evolved in Sweden during the COVID-19 pandemic. Third, to appraise what effects different forms of Twitter interaction have on digital state authority. Four, to discuss the implication of a more qualitative understanding of digital authority, especially regarding the legal-rational foundations of a modern state.

Our explorative case study (Yin, 2003) examines these questions by analyzing the Twitter communication of government agencies tasked with dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. The analyzed data covers the period from January 2020 to March 2021 and includes the two first waves of COVID-19 in Sweden. During these waves, vaccines were still not an option of pandemic management, and Sweden, like other countries, had to rely on conventional pandemic measures like social distancing and basic hygiene requiring discipline from the population, as well as clarity, precision and ultimately, authority, from the state agencies in their communication with society.

We will next discuss our dataset and methodological premises before turning to the concept of digital authority and how it is reflected in interaction on Twitter. Here, we will roll in Voloshinov's insights on reported speech that allow us to place Twitter's technological affordances into a socially meaningful context.

We look at the communication of four governmental Twitter accounts: (i) the Public Health Agency (Folkhälsomyndigheten, @Folkhalsomynd) tasked with the epidemiological information and policy, (ii) the Swedish Agency for Civil Contingencies (Myndigheten för samhällsskydd och beredskap, @MSBse) tasked with an overall coordination of crisis situation in Sweden, (iii) the Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen, @socialstyrelsen) tasked with the coordination of medical supplies and resources, and (iv) the web-platform Crisis Information (Krisinformation, @krisinformation) tasked with collecting and publicizing emergency information from Swedish authorities.

Our main dataset includes all tweets between 1.1.2020 and 31.3.2021 (a) that were sent by one of the four governmental accounts (including their retweets) and (b) that engage in direct interaction with those government accounts by including one of the account names with or without the @-sign. Altogether this yielded 166,692 tweets (285,329 with retweets). We have used Mecodify to collect the data (Al-Saqaf, 2016; Al-Saqaf and Berglez, 2022). We have not limited the search thematically, yet the vast majority of tweets in our dataset is related to COVID-19. As our focus lies on the interaction government agencies trigger, we focus on the tweets that were most retweeted, replied to, or quote-tweeted. While this still represents only a fragment of what has been said about the Corona crisis in the Swedish Twitter sphere, it enables us to conduct a more thorough analysis of the government channels' digital authority. It must, however, be pointed out that in Sweden, with about 2,5 million Twitter accounts, not even 50 tweets from the state agencies gained 100 or more retweets between January 2020 and March 2021. Moreover, of these tweets, 38 were posted during March and April 2020, i.e., during the initial period of the Corona crisis. As the crisis prolonged, the state agencies' accounts quickly lost their momentum.

The dataset has been used to investigate and unfold the dynamics of digital authority exercised by the state agencies. The dataset has been filtered for different parts of the analysis to focus on different kinds of interaction: retweeting, replying and quote-tweeting. We have also filtered the dataset to see how (and why) mentioning or naming government accounts function in relation to digital authority. We further focus in more detail on two specific peak periods: March–April 2020 as the beginning of the pandemic, and December 2020–January, 2021, coinciding with the second peak of COVID-19 pandemic in Sweden. Our approach to treat Twitter data is inspired partly by Fuchs (2018) qualitative study of selected Twitter accounts in order to shed light on a broader political phenomenon (populism) as well as Lindgren (2020) view of bringing classical sociological theory to pursue grounded theory inspired “deep dives” (Markham and Lindgren, 2014) into Twitter mediated social interaction. For Lindgren, the aim of social media analysis is not to confirm or verify social relationships with big amounts of data; rather he encourages researchers to think of actors and structures and their interplay in the big data.

The qualitative analysis was carried out as follows: the tweets were sorted by metrics of interaction and then read individually and coded according to Voloshinov's theory of reported speech (as described below), paying attention to what is the sequence of retweeting, replying or quote-tweeting.

Gortitz et al. (2020) talk about the concept of digital authority as an asymmetrical relationship. They draw on literature on global governance utilizing a notion of authority based on its legal sources and perceived expertise. Zürn, working on Weber's sociology of domination, calls this reflexive authority (Zürn, 2018). Reflexive authority emphasizes the continuous, interactive, construction of social contracts as the sources of Weberian rational-legal authority (Zürn, 2018; Weber, 2019). For Zürn, reflexive authority departs from the logics of appropriateness and consequentiality. The legitimacy of authority results from recognition of one's own limitations and an authority's perceived superior or impartial perspective. Zürn's conceptualization of reflexive authority in international relations is in line with Rosanvallon's claim that the domestic legitimacy of public authority “must be demonstrated in practice” (Rosanvallon, 2011, p. 96). Both Zürn and Rosanvallon emphasize that authority should be studied as reflexive action not as a status or attribute. According to Zürn, most attempts to question reflexive authority do so on epistemological grounds, i.e., they do not question the actual facts in the “superior perspective” but rather question the foundations of the perspective, i.e., they decline to be reflexive in the sense of recognizing the limits in their own perspective (Zürn, 2018, p. 46).

Gortitz et al. turn this interactively constructed legitimacy into a digital authority which is based on recognition, enables influence, and is exercised in online social networks forming a “digital public sphere” (Gortitz et al., 2020, p. 6). Alongside expertise and moral authority, digital authority is an additional dimension of the de facto authority that correlates but is not identical with the de jure authority of public institutions (i.e., their formal legal position and power). Conceptualized in this manner, digital authority is not limited to official state bodies but can equally be acquired and exercised by private institutions and individuals. Indeed, most studies on digital authority focus on other than state actors. Digital authority is a factor that has the potential to support or weaken public actors (Casero-Ripolles, 2018; Dagoula, 2019).

Digital authority as a measure of control, or influence, over the digital public sphere is tied to the affordances of different social media platforms. Twitter has emerged as the primary networking tool in the political sphere (Dubois and Gaffney, 2014; Jungherr, 2016; Gortitz et al., 2020; Casero-Ripollés, 2021) because users tend to have a public profile and because hashtags facilitate the emergence, identification, and visibility of public debates. Furthermore, it combines wide outreach to politically relevant accounts, online real time coverage of political events, as well as convenient and informal ways of interaction.

Digital authority focuses on the interactive dimension of social media platforms, more specifically on the number of times an account is the addressee of communication, or its message is shared by others (Gortitz et al., 2020; see also Maireder and Ausserhofer, 2013; Riquelme and Gonzalez-Cantergiani, 2016). Gortitz et al. operationalise digital authority as the sum of retweets, replies and mentions a tweet generates. Alternative ways of operationalisation of digital authority include, for instance, Casero-Ripollés (2021) focus on tweeters' eigencentrality, i.e., the Twitter account's connections in the network. Yet, both rely on quantitative understanding of digital authority. Gortitz's et al. operationalisation, however, has the advantage of taking the tweet as the central unit of analysis, which also allows for the inclusion of the content of that tweet into the analysis of digital authority. Unfortunately, this potential is left unexplored by Gortitz et al. Their logic seems to be that all publicity is good publicity in stark contrast to Zürn's and Rosanvallon's account of reflexivity at the core of authority relations. In this article, we add to the metric-based view on digital authority a qualitative analysis of the content of the tweet in order to shed light on the dynamics of digital authority beyond mere mass of interaction. This should yield a better understanding of how social media interaction contributes to, or undermines, actors' authority in the digital public sphere.

Two observations especially support the suggested “qualitative turn” of an analysis of digital authority. First, different forms of Twitter interactions with government tweets and accounts (such as retweeting, replying, quoting or mentioning) indicate different relations to that authority. Thus, each form of interaction already contains an unpronounced qualitative dimension, determined by the specific logic of the applied social media. While approval or contestation both indicate the recognition of someone or something as an authority, continuing contestation may well have detrimental long-term effects to authority. Our longitudinal data covering the period from January 2020 to March 2021 allows us to study not only who is posited as an authority in the digital public sphere, but also how one's relationship to that authority evolves. Second, Gortitz's et al. study is based on data from global governance on climate change, and thus cannot be compared with a situation of an unfolding crisis. The differences in our data enable testing digital authority in a context of a crisis. As noted above, crisis situations are prone to rally people around the government, but how long does such an exogenous support for the government last? How do public authorities fare in the contest for digital authority—a dimension of authority they are clearly interested in, but cannot compete for under the same premises as non-government actors?

For Weber, legal-rational authority has an inbuilt tendency to flip to traditional or charismatic authority (Weber, 2019). Whilst traditional authority is prone to inertia, charismatic authority carries the potential of constant revolution. The question of how social media contributes to state agencies' digital authority in practice is not just a question of their digital performance, but also concerns the sources of potential change in the way public power is legitimated. As many studies indicate, social media favors individualized frames of reference (Bennet and Segerberg, 2013; Papacharissi, 2015; Gustafsson and Weinryb, 2020), which are not necessarily “reflexive” in the sense Zürn or Rosanvallon use the term. Basing the legitimacy of public authority on interaction may induce reflexive “subjugation” but also charismatic questioning of the legitimacy of public authorities.

Going beyond social media as a network requires interpretation of both, the meaning of the tweet and the interaction around it. The affordances of Twitter encourage interaction that builds on other account's tweets: retweeting, quote-tweeting and replying; or recognition of another tweeter: mentioning. In linguistic terms, all these actions can be characterized, and will be analyzed by us, as different forms of reported speech [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930); Holt and Clift, 2007]. In addition to the intricacies of reported speech, we also need to understand the context in which such reporting takes place. This context can, in Twitter, be approached through hashtags and the abovementioned sequence of reported speech. Focusing on both, the more algorithmic, or automated, big data of hashtag dynamics and the more qualitative and human mediated acts of retweeting, quote-tweeting and replying we hope to tackle the structure and agent relations (Lindgren, 2020) in Twitter mediated digital authority.

Below we will discuss Voloshinov's theory on reported speech before moving on to look at how hashtags and different forms of interaction function in Twitter. The reason we prefer Voloshinov—writing in the 1920s—over more modern contributions is that Voloshinov's work on reported speech is foundational to this research field, and he was interested in the ideological and social contestation conveyed in reported speech (Coulmas, 1986; Holt and Clift, 2007). This suits our purposes to explore the dynamics of digital authority.

Interactivity of social media is central to its functioning but appears often undertheorised (Vitak, 2012; Georgakopoulou, 2017). In order to provide new insights on how interaction beyond network analyses can be studied, we turn to Russian theoretician of language Voloshinov and his inquiries into reported speech in Marxism and the Philosophy of Language [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930). Succinctly, Voloshinov understood reported speech as “speech within speech, utterance within utterance, and at the same time also speech about speech, utterance about utterance” [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930), p. 115, italics in original]. Whilst the former refers to the borrowed, i.e., other person's content of the speech, the latter dimension refers to the structuring capacities of reported speech: it inevitably becomes a commentary and analysis of the content. Reported speech occurs in a triadic nexus between the original message, the context of the reporting about this original message and the audience to which this message included in the reported speech is addressed.

For Voloshinov, language represents power relations between its users. This originally Marxist premise has since become a standard paradigm in discourse studies and sociolinguistics. It allowed Voloshinov to argue that reported speech is always an active appropriation of another's speech, which is then presented to the third person. The way in which both the speech is appropriated, and the reported speech is received, is conditional upon societal power relations reflected in language [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930), p. 117]. The reported speech, like any speech, is always addressed to someone and exists in a concrete context: “Any utterance, no matter how weighty and complete in and of itself, is only a moment in the continuous process of verbal communication. But that continuous verbal communication is, in turn, itself only a moment in the continuous, all-inclusive, generative process of a given social collective” [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930), p. 95, italics in original]. This places the act of reporting in a broader social continuum of power relations [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930), p. 96].

Reported speech requires grammatical complexity (Spronck and Nikitina, 2019). For instance, it involves deictic shifting (I now recall that John yesterday said that it would rain today), but also temporal incongruence (recall, said, would rain). Also, subordinate clauses (John yesterday said it would rain today) can become the main information bearers. The relationship between the act of reporting and the content that is reported is revealed by the grammatical choices. Grammatical complexity in other words reveals the ways in which speech is appropriated in a given social context.

Voloshinov distinguished between two socially relevant variants of reported speech: factual commentary and reply or retort. Whilst the former focuses on commenting on the factual content, the latter is a personally motivated evaluation, retort or Gegenrede, of that content. Although both are always present, one is usually dominant. Any analysis of the factual commentary or its retort is only possible against the background of the context in which the reported speech is invested, thus making the relevant unit of analysis that “dynamic interrelationship of these two factors, the speech being reported (the other person's speech) and the speech doing the reporting (the author's speech)” [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930)), p. 119] in its social context of power relations.3

Voloshinov identified two basic directions as to how the interrelationship between the reported speech and the authorial speech develops. The first is to preserve the authenticity and distinctiveness of the reported speech. In this case, the focus lies on the content of what is being reported, and the speech is received as a holistic content with its own distinctive message and style. This type of reception is also possible if the original message is received as authoritative or dogmatic: “The more dogmatic an utterance, the less leeway permitted between truth and falsehood or good and bad in its reception by those who comprehend and evaluate, the greater will be the depersonalization that the forms of reported speech will undergo” [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930), p. 120]. This coincides with requirements of reflexivity and subjugation to authority in Zürn's account of reflexive authority. The other dynamic focuses on the possibilities of reporting and reported speech infiltrating one another. This process normally takes impetus from the reporting context, permeating the reported speech with its own intonation such as humor, irony, or enthusiasm [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930), p. 121] effectively undermining the autonomy of the original speech. However, also the contrary is possible where the reported speech hijacks the reporting context diluting the authority and objectivity that are normally invested in the reporting context. For Voloshinov, “the dissolution of the authorial context testifies to a relativistic individualism in speech reception” [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930), p. 122]. This coincides with attempts to contest authority.

Voloshinov argued that all speech is addressed to someone. Yet not seldom is it difficult to delineate that audience, especially in the case of social media. Voloshinov argued that the function of audience can be approached through the concept of “social audience” [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930), p. 86], which refers to an internalized environment in which “reasons, motives, values and so on are fashioned” [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930), p. 86]. This social audience affects the way utterances are formulated. Utterances are composed of words; a “word is a two-sided act. It is determined equally by whose word it is and for whom it is meant. As a word, it is precisely the product of the reciprocal relationship between speaker and listener, addresser and addressee” [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930), p. 86]. Because words have the capacity of acting as bridges between interlocutors, the utterance, made up of words, is a way to construe the linkage between the speaker and the audience. From this follows that the audience as a posited audience—we cannot know beforehand the “real” audience in Twitter (followers are just an indication) any more than we can control how our speech in practice is taken up by listeners—serves the purposes of constructing a desired identity of the speaker, bridging between the speaker and the posited audience. In other words, the posited social audience signals the evaluation of the utterance; or yet in another way: the posited social audience can be used as a signal of the identity of the speaker.

We will now move on to operationalise Voloshinov's theory on reported speech in the context of Twitter by looking at the different affordances of Twitter. Hashtag (#) as a user-generated keyword is the standard way of claiming a certain external, or “material” context and audience for the tweet. Keywords, in turn, can be understood as an authoritative system of classification of information as in library sciences. In this case, the information content determines which keyword should be assigned to best categorize it. On the other hand, keywords function as a means to condense the essence of an historical epoch or a political programme acquiring an emotional tag. Thus, hashtags are keywords that organize tweets as well as attach some with emotional and political charge as illustrated e.g., by #MeToo (Bernard, 2019, p. 38). The modern hashtag fuses these functions making it “an index and a slogan at the same time” (Bernard, 2019, p. 42). This double function of a hashtag brings along some far-reaching consequences. The indexing function of the hashtag “emancipates” the users to create his or her own public sphere and audience, but the slogan function subjects the hashtag to both the media logic and the affordances and algorithms that regulate the social media platform: while some hashtags succeed and become “trending,” most fall into oblivion. This concerns not only the hashtags, but also the political identities created through the hashtag. In Twitter, using hashtags means taking part in the competition for attention of the social audience; opting out of hashtags is to claim alternative functions of tweets than that of the market logic.

Retweet means forwarding the message of another user to one's own account's followers and readers. Retweets can further be classified in two sub-categories, “pure retweet” and “quote-tweet.” The former, hereafter “retweet,” directly forwards the original message including any metrics concerning likes and further retweets. A retweet does not exist independently: if the original tweet is deleted, all retweets become deleted, too. A retweet also preserves the dynamics of the original tweet: any replies to retweets are passed on to the original Twitter account. Given these dynamics, retweets are generally seen as endorsements of the original tweet (Metaxas et al., 2015). This is even confirmed by the common label that “RTs (retweets) are not endorsements,” which nevertheless does not annul the fact that retweets help the original tweet to gain broader audience and establish affirmative connection between the tweeter and the posited social audience.

A quote-tweet embeds another account's tweet in one's own tweet and allows one to comment on the original tweet. New context and content is added, and quote-tweet acquires grammatical complexity that reveals the ways in which the other's words are appropriated and what social structures come into play in this appropriation. For example, the content of the original tweet can be explicitly endorsed or rejected (including an explanation why), but also criticized, ridiculed, or acclaimed. Most importantly, the quote-tweet becomes “independent;” it can be retweeted as described above, and even a deletion of the original tweet will leave it intact—in a Voloshinovian understanding it has been appropriated as reported speech in a new utterance. In a reply to such a quote-tweet, the author of the original tweet will not be added automatically (Also, you will be able to see the metrics of the quote-tweet, in contrast to a pure retweet). A quote-tweet is removed from the original context and new content may be inscribed to it. Its audience has become unspecified, reflecting the posited social audience of the new tweeter. Like in the first case, the quote-tweet seeks to construe a specific identity of the speaker, this time by exercising control over the meaning of the original tweet, sometimes for the speaker's own advantage.4

A reply is an answer to a tweet. It automatically addresses the author of the tweet, but also any other twitter handle (username) mentioned in it (further usernames can be added manually). The audience of a reply is by default thus the same as that of the tweet replied to, but it will also appear in the newsfeed of those following the replying account. In the Twitter timeline, replies are visually placed under the tweet they refer to. Replies to replies (and replies to those) are possible. A quote tweet allows for addressing one's own followers, whilst when reaching out to someone else's audience, a reply is the better option. A reply thus has the function of through appropriation of the tweet to place it in a new context in front of the original addressees.5

The last case, mentions, differ from the above-described forms of interaction, because, if placed manually (and not automatically, as in a reply), they do not refer to a specific tweet but to an account/user. By including one or several usernames in the tweet one can address somebody publicly, like an open letter. The mentioning ensures that the mentioned user will see your tweet in his/her notifications, and that your own followers understand to whom your tweet is directed (other users will see such mentioning only if they search for them).

All forms of interaction described above—retweets, quote-tweets, replies and mentions—make a distinction between the original content of the tweet and its originator and the commentary layer of meaning brought about by reporting this content. For example, applying Voloshinov's terminology of utterance we can see that a pure retweet has the purpose of conveying an authoritative message to the audience—and thereby with the help of the posited audience, construe a certain desired identity for the retweeter. Similarly, replies and quote-tweets in Voloshinov's theory would have the function of infusing the reported speech with a new meaning varying from acclaim to scorn or irony. To interpret, e.g., ironic meanings, it is necessary to understand the context of the tweet. We have suggested above that this context can fruitfully be reconstructed by taking into account Twitter's two logics of operation explored here, the first dealing with accumulation and commodifying one's hashtags, making them trending, the other by studying concretely the dialogical sequences in which retweets, quote-tweets, replies and mentions occur. Retweets and quote-tweets enable one to address one's own audience whilst reply and mention enable one to reach out to new audiences, namely those of the original tweet and/or account. Both modes of interaction can be used to work on one's own identity or the addressee's identity. In a competitive situation over authority, such identity work can easily assume a zero-sum mode: one's gain is the other's loss.

Digital authority as a purely quantifiable dimension of interaction cannot include this interactive context and therefore misses the purpose of such interaction. Complementing the operationalisation of digital authority with the analysis of the sequence and content of interaction, we will provide a more nuanced and factual picture of the reality of digital authority of the four government agencies tasked with the Swedish COVID-19 strategy.

The analysis will proceed in three stages. We will first look at the dataset as a whole as well as the broad context as construed by used hashtags. We will then zoom in on two peak periods coinciding with the first and second wave of COVID-19 in Sweden to better understand the changes in digital authority of the government accounts. Third, we will look more closely at a few peak events to gain detailed information about the practices around digital authority in Sweden.

The four government accounts have varied followership on Twitter. As Twitter does not store the number of followers for individual accounts, we have reconstructed the historical followership with the help of web.archive.org. Before the Corona crisis, Krisinformation was followed by 98 k Twitter accounts, MSB by 30 k, Socialstyrelsen by 13 k and FHM by 9 k (see Table 1). Their followership increased during the Corona crisis. By mid 2021, Krisinformation had 128 k followers (30% increase), MSB 42 k (40% increase), Socialstyrelsen 19 k (46% increase) and FHM 57 k, an increase of 533%. To compare, we looked at two major Swedish news outlets, Dagens Nyheter and SvD, which increased their followership from pre-crisis 219–242 k (11%) and from 206 to 224 k (9%) respectively. The public television SVT's Twitter followers rose from 143 to 196 k (37%). The increase of the followers of the government accounts, especially that of FHM, indicates the importance of expert knowledge in contemporary politics as well as public agencies' conscious attempts to reach out to the public through social media. Still, even in the eye of a global pandemic, with all its possible implications, traditional mass media sources of information continue to be more popular than governmental channels specifically aiming at crisis communication.

The four government agencies have different roles in crisis management. Krisinformation is responsible for collecting and publicizing information, MSB is tasked with coordination whilst FHM and Socialstyrelsen produce expert information and policy recommendations, FHM in the field of epidemiology and public health and Socialstyrelsen in relation to health care provision.

One of the foundational ideas of social media is the logic of accumulation: one needs to generate attention. The concept of digital authority, too, builds on the idea of how much interaction one can generate. Of course, not every actor in social media needs to acknowledge or follow that logic, and there are indicators that accounts of public agencies more often than others deviate from that logic. In some cases, this may be a conscious decision, while in others it is due to the lack of expertise or personnel.

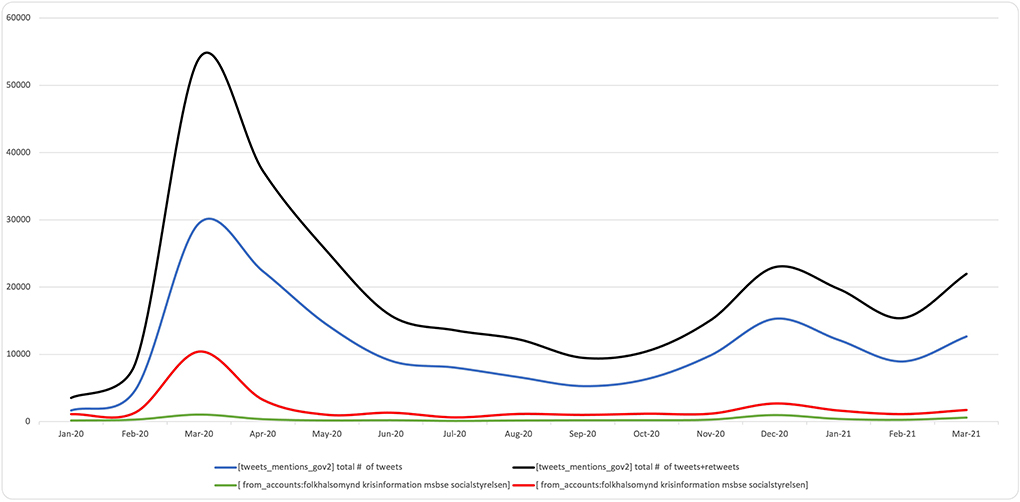

Measuring accumulation of attention is a multifaceted task. One could simply aggregate all government Twitter activity and put it in relation to all generated retweets. Figure 1 shows the monthly breakdown of the “total” number of tweets from the four government accounts and their retweets and all those tweets that in some manner mention or engage with the government accounts. The government accounts do not tweet frantically: in March 2020, they sent out 1,053 tweets and over 53,000 tweets were interacting with or discussing them; in April they sent 354 tweets and since then it has hovered around 200 until the second peak of 982 tweets in December 2020. However, the initial high ratio of retweets declines rapidly after March 2020, even though the government accounts enjoy relatively high interaction ratios throughout the whole analyzed period.

Figure 1. Total tweets (monthly). The green line shows the tweets from the four government agencies @folkhalsomynd, @krisinformation, @MSBse and @socialstyrelsen (5,387). The red line includes in addition the retweets of these tweets (31,026). The blue line includes in addition all replies to and mentions of the governmental accounts (166,692). The black line includes in addition also the retweets of replies to and mentions of governmental accounts (285,329).

Zooming in on individual agencies (Table 2) we see that FHM's Twitter activity is most often retweeted (1 to 14) followed by a fairly even distribution between Krisinformation and socialstyrelsen, and MSB holding the lowest score. Looking at the kind of Twitter activity the government accounts produced, we see that out of the total 5,387 tweets sent, as many as 4,391 (82%) are replies—leaving 996 (18%) what we term agency-initiated tweets appearing on the agency's main timeline (Table 2). The agencies also use the reply function differently. Krisinformation's and MSB's main activity on Twitter consists of replying, whilst expert agencies FHM and Socialstyrelsen mainly tweet new information. Instead of looking at the total Twitter activity, one could argue that only the tweets that the account initiates and thus appear as default on their timeline should be used to assess how much attention they generate. Focusing on agency-initiated tweets we see that not FHM's, but Krisinformation's tweets are the most retweeted (1–42). Even this simple breakdown of different kinds of interactions allows for a more nuanced quantitative analysis of digital authority.

What is the purpose of replies in this attention-seeking social media logic? One could argue that it is part of government agencies' tasks to ascertain that reliable information reaches the public, including clarifying replies to citizens' questions. Indeed, taken together, most government agencies' Twitter activity consists of replying. Krisinformation and MSB stand for more than 96% of all replies. However, it seems that the affordance of a reply function was used neither systematically nor consistently. Instead, reply communication appears mainly random and without a clear strategy. For example, FHM generally seems to avoid replying, but under certain periods does so even extensively (nearly one third of their tweets are replies). It seems that there is no coherent policy, and the agencies' engagement depends on the personnel assigned and his/her social media preferences.

Let us look at the public side of engagement with the government accounts. The centrality of FHM to the public is clear in our data. Of the 140 k tweets replying to or mentioning the four agencies 112.5 k refer to FHM (14.5 k Krisinformation, 10 k Socialstyrelsen and 12.5 k MSB). The prevalence of FHM can be explained by the significance given to science in contemporary politics and pandemic strategy in Sweden. Moreover, FHM organized daily “government” press meetings, hosting Ministers in their premises if necessary. Finally, the state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell at FHM emerged as the face of the Swedish COVID-19 policy. FHM emerged as the social audience to or against which many on Twitter felt a need to establish some kind of affective relationship and construe their own identities. Despite the quantitative superiority of Krisinformation when it comes to tweets sent and retweets generated, FHM has the dominance regarding mentions and replies.

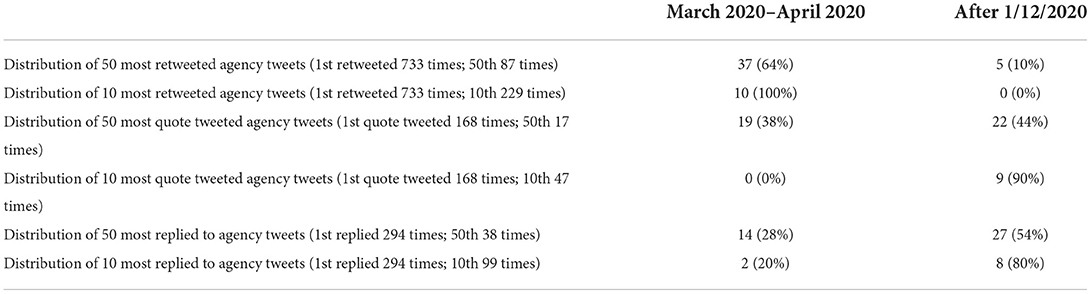

The public's way of engagement with the government accounts, however, underwent a change during the period we studied. In the early period, government tweets were mainly retweeted. As the crisis prolonged, replies and quote-tweets increased in proportion. Of the 50 most retweeted government tweets in the dataset, 37 (64%) are posted in March and April 2020 and only 5 (10%) after 1 December 2020 (Table 3). However, only 14 (28%) of the 50 most replied to and 19 (38%) of the 50 most quote-tweeted tweets were sent during March and April 2020, while 27 (54%) respective 22 (44%) appear after December 1st, 2020. When zooming in on the respective top 10, standing for the vast majority of all generated retweets/quote-tweets and replies, this shift becomes even more dramatic: The 10 most retweeted tweets were all posted in the early period, while 80% and 90% of the most replied and most quoted tweets respectively appear after December 1st, 2020. Following Voloshinov, such a change from treating information as authoritative to appropriating it and infusing it with new contexts, indicates a growing contestation of the legal-rational authority of the state agencies as the crisis prolongs.

Table 3. Distribution of top 50 and top10 most retweeted, quote-tweeted, and replied to agency tweets.

By looking at the hashtags that dominate, we can further poke the actual context with which the government accounts were engaged in interaction. Among the ten most frequent hashtags (Table 4) in our dataset are #svpol (5,138 tweets) (1st), #covid19sverige (2,407 tweets) (3rd), #coronasverige (2,261 tweets) (4th), #bytstrateginu (1,388 tweets) (6th), coronavirussverige (1,342) (7th) and #tegnell (1,158 tweets) (8th), all of which are Twitterspheres more or less critical of the Swedish Corona strategy and the state agencies involved in it.

The use of critical hashtags increases as the crisis prolongs. Some hashtags, such as #bytstrateginu (“change the strategy now”) could only be articulated after the communication of an official COVID strategy (see Figure 2). The hashtag appears for the first time in May 2020 and peaks in June 2020, a month of overall low Twitter activity in our dataset. Its use declines during the summer and peaks again in December 2020.

A number of conclusions can be drawn from the use of hashtags in our data. First, the use of hashtags is not as common in our dataset as one could expect. There is no single dominant hashtag that unifies the public sphere, or successfully commodifies the Corona crisis. It appears that there is no hegemonic public sphere formed by one or a few trending hashtags; instead, fragmentation prevails. Second, the posited social audiences become increasingly more critical—and less reflexive—of the Swedish Corona strategy as the crisis prolongs. The most prominent hashtag #svpol is an alternative right-wing self-identifier, but it is also accompanied by other government-critical hashtags. Looking at the changes in the hashtags between March–April and December–January, we can see that more neutral hashtags such as #corona (6th) and #coronavirus (7th), and #coronaviruset (10th) have disappeared6 and more specific hashtags such as #bytstrateginu and #tegnell, both of which gather mainly critical voices of the Swedish Corona policy, have become more prominent. Other newcomers like #sweden reflect the global, critical, interest in Swedish strategy and #krisinformation relates to a singular event connected to the “SMS to the people,” that was sent in November 2020. The fact that these hashtags emerge from the data that interact with the government means that despite their criticism, the accounts behind the hashtags still engage with the government information. Following Gortitz's et al. interpretation, this should be a sign of digital authority, but we find this doubtful. Rather, we argue that this indicates the emergence of a more charismatic authority contesting the state's legal-rational authority in the digital sphere as the crisis prolongs. Third, government agencies systematically opt out from social media logics by not using hashtags. This may appear as implying they have not understood how social media and Twitter works, but, as Bernard (2019) argued, hashtags delineate certain publics and create segmented public spheres. Thus, the opt out can be interpreted as a conscious strategy of claiming neutrality. In Voloshinov's terms, they try to emphasize the (authoritative) content of information by implying its impartiality and universality, not to whom it is addressed or the form in which it is packaged as is the case in the charismatic contestation of legal-rational authority.

Retweet is a form of reported speech that emphasizes the factual content of the original message. Retweet was the dominant form of engaging with the government during the early period in our data. For Voloshinov, this kind of reported speech signals “authoritative” relation between the content and the reporting situation. Consequently, looking at what is being retweeted, reveals what is popularly approved in the (digital) society. For the period March 1st, 2020, to April 30th, 2020, there are 51,849 tweets (91,256 with retweets) in our dataset, representing 31% of the total number of tweets. Among the 20 most retweeted, there are twelve from the government accounts (11 Krisinformation, 1 FHM), two from other public actors, one news site, and five tweets from individuals. Of the five individual tweets, two are positive, and three voice critical views of the Swedish Corona strategy and the agencies implementing it. The government accounts, especially Krisinformation, dominate the communication initiated by and about themselves. If we exclude the tweets sent from governmental accounts the content of the top 20 most retweeted tweets during March and April 2020 changes: there are 15 tweets from individuals, 3 from other public agencies and 2 from news sites. Among the tweets from individuals, three are positive, two are neutral and ten are negative. One of the news sites is positive, one negative; three tweets from other public agencies are neutral. Already during this early phase of the pandemic, the digital authority of the government does not remain uncontested.

By the end of the year, during the period December 1st, 2020, to January 31st, 2021 (27,430 tweets, 42,691 with retweets) there are only seven tweets from government accounts among the 20 most retweeted in our dataset; the remaining 13 tweets come from individuals (12 tweets) and from a civil society organization (1 tweet). Two of the individual tweets are from foreigners reporting neutrally on Sweden; the remaining 11 are critical of the Swedish Corona policy. If we exclude the government tweets, we have among the top 20 retweeted three neutral tweets by foreigners reporting on travel conditions in Sweden; the rest levels criticism against the Swedish Corona strategy and agencies involved in implementing it.

For Voloshinov, retweet indicates an authoritative relation to the content of reported speech. This combined quantitative and qualitative analysis of the most retweeted tweets in our dataset shows that as the crisis prolongs, the government agencies not only decrease as the source of interaction about themselves, but this interaction is also more often framed critically. In other words, what is considered authoritative information becomes increasingly negative of the government line.

Let us now look at the two other forms of twitter interaction: replies and quote-tweets. The distinction between these two, based on Voloshinov's account on reported speech, is that the former is addressed to the sender directly while the latter is a general statement about the “facts” conveyed in the tweet. To address the sender directly has the function of affecting the sender's social status; to comment on the factual base of the claim has a function of re-evaluating the facts stated. In contrast to a retweet that signals authoritative relation to the content, the appropriation of the original content in replies and quote-tweets adds grammatical complexity to the act of reporting infusing the reported speech with new layers of meaning.

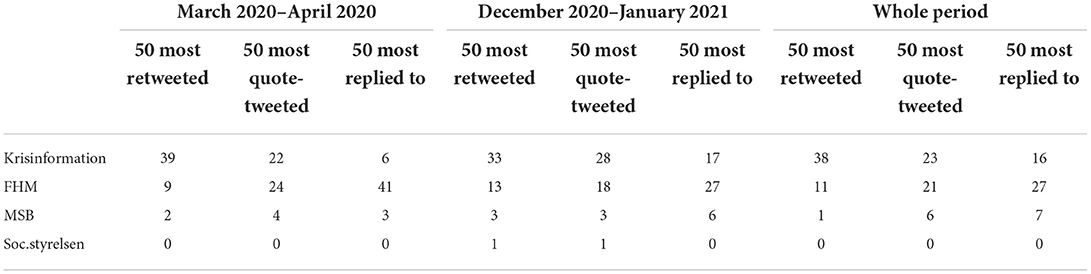

Table 5 shows the distribution of different forms of interaction with the government agencies. Krisinformation is responsible for a vast majority of the 50 most retweeted agency tweets, reflecting its position and function as a source of (authoritative) information. FHM, by contrast, stands for more than half of the 50 tweets that were most often replied to, and during the early phase of the pandemic even for more than 80%. This is, interestingly enough, despite FHM's comparable low engagement in reply-communication. The most quote-tweeted tweets are rather evenly distributed between Krisinformation and FHM.

Table 5. Distribution of different top 50 retweeted, quote-tweeted, and replied to government agencies tweets.

Both FHM and Krisinformation receive the most attention, while MSB and especially Socialstyreslen play a minor role. Already during the early phase of the pandemic, FHM—often impersonated by Tegnell—became the “face” of the Swedish Corona strategy. FHM in relative terms was most often replied to government agency in our material. FHM in other words appears as an actor in the crisis, whilst Krisinformation—at least in the early stages—was a source of (authoritative) information to be retweeted.

Let us look at the replied tweets first. Among the most replied, there are several that inform not about the Corona virus, but about the FHM's work during the Corona crisis. The most replied to tweet refers to a study showing that FHM enjoys high trust among the population (March 14th, 2020). The next one relates to the claimed ineffectiveness of school closure (March 1st, 2020). Other tweets are calls for the daily press meeting (seven examples), which nevertheless receive replies that criticize FHM for their policies. Such replies bear no direct relevance to the invitation but are used to call into question the soundness or logical consistency of FHM's recommendations and arguments concerning Swedish Corona policies. The same applies to other tweets through which FHM informs the public about their activities. FHM's tweets that inform about the Corona situation in society are replied with outright negation of the information. The tweet in which FHM claims inefficiency of school closures reads in its simplicity: “Locking down healthy school children no effective measure—Swedish Public Health Agency”7 referring to their own website for more information. On the website, we learn that “FHM assesses that locking down healthy school children is not an effective measure. It is unlikely that healthy school children could cause the spread of the virus.”8 This tweet and information is replied to by, for instance: “You will see you're so wrong… But then it might unfortunately be too late. Only a few people in Sweden believe in you, and rightly so,”9 or as “I hope you are right, but how do you define a school child? Does one suddenly begin to spread the virus when one turns 20? Or is it a growing scale?” or pointing out alleged illogicalities in the formulations of FHM, as in the following example: “The virus cannot with all thinkable logic distinguish whether it will be spread by a child or an adult… Where is the respect for our elderly? How do you protect the already overwhelmed health care system?” Such replies merge aspects of known weaknesses or failures of the Swedish Corona strategy, such as the failure to protect the elderly or the constant lack of and delays in recommendations, to question the competence of the FHM. Reported speech requires grammatical juggling. The free combination of tenses—the future (“You will see”) in contrast to FHM's present tense “assesses” draws attention to the long-term consequences of FHM's actions, whilst the grammatical change from the nominalisation (“the spread of the virus”) to an active agent (“The virus cannot with all thinkable logic distinguish…”) discredits the FHM's implicit claims to be in control of the virus granting the virus the agency in the crisis. The agentification of the virus also works as a grammatical attack against FHM's posited agent of “healthy school children.” These are techniques for appropriation of others' speech and giving it new meaning in reported speech. The replies indicate very little or no reflection of one's own epistemic limits as is the case in Zürn's reflexive authority, and unashamedly question or attack the sender's authority based on subjective convictions as Voloshinov's reported speech implies.

As pointed out before, quote-tweets offer the possibility to engage with the factual base of the message. There is some overlapping between most replied to and most quote-tweeted tweets. During March–April 2020, the most quote-tweeted tweet comes from FHM informing they have found a mistake in an earlier report. The tweet received substantial international interest, and in the quote-tweets Swedish and international accounts reconstruct the context and refer to earlier statements about herd immunity, indicating that FHM may not have undisputed expert knowledge, as ironically constructed here: “One is called a tin-foil hat if one questions these stars…” Another one applauds to “ TRANSPARENCY

TRANSPARENCY ” and a third one ridicules Sweden's herd immunity plans: “Seems like Sweden's herd immunity might just have to wait a while.”

” and a third one ridicules Sweden's herd immunity plans: “Seems like Sweden's herd immunity might just have to wait a while.”

Among the most quote-tweeted tweets is also the one where FHM claims that opinion polls show high trust in their work. This tweet is quoted mainly by pointing out the temporality of the result thus changing its context from general trust to that of a very context specific, and possibly isolated, piece of information as in this quote-tweet from March 15th: “It won't last if one continues to deal with COVID-19 as a normal seasonal influenza. The virus mutates and one lets it spread freely. Scandal” or in this from July 5th, 2020, months after the original March 14th: “That was back then.” The honesty of the reported high levels of trust is also doubted: “You may wish so.”

A tweet from Krisinformation warning about spreading disinformation about COVID-19 is also questioned in terms of its factuality or ability to convey factual information. One quote-tweet tries to make fun of the grammatical formulation Krisinformation used, another quotes the tweet by adding “At the same time we really have to be source critical as a lot of disinformation is circulating” implying that it is Krisinformation that is guilty of disinformation, and yet another quotes Krisinformation as “applies to all” adding the hashtag “#fakenews.” Such ironic appropriations of the tweet indicate how the change of context renders the content of the tweet quite the opposite from its initial meaning. In our data it appears that replies are most often used ironically to ask for a clarification or to post a follow-up questions, but at times also to explicitly undermine the authority of the sender. Quote-tweets, on the other hand, tend to cast the content of the original tweet in ironic terms. Such a usage of quote-tweets is not exclusive but seems to occur more often in communication with official and perceived authorities. In other contexts, we have seen quote-tweets also provide a positive framing for the original tweet, claiming/appropriating some of the fame of the original tweet.

The ways in which replies and quote-tweets are used during the second peak of COVID-19 infections in December–January, 2020–2021, overall follows patterns of the first peak. However, one clear difference is that there appear tweets that are not Corona-related, but report on totally unrelated matters, such as testing of the public alarm (Hesa Fredrik) or firework regulations ahead of the New Year's celebration (which were possible given no lockdown in Sweden). Among the 20 most quoted tweets there were two, and among the 20 most replied tweets altogether five of those. We will look only at the Corona-related tweets here. One tweet from Krisinformation informs about a coming public sms to Swedish mobile phones, the so called “sms to the people.” The imminent sending of this SMS was announced to the public on Friday, December 11th, 2020, in the presence of two ministers and representatives of FHM and MSB. The public was informed that for the first time the Swedish government attempts to send a public SMS to all mobile phone numbers in Sweden (Press Conference, 2020).10 There were concerns that SMS could be perceived as a bluff, hence a press conference announcing the coming of the SMS. In this context Krisinformation tweeted on Saturday, December 12th, 2020, the following:

“Important information before Monday's sms:

- Sender row: “Fohm, MSB.”

- Text: “Information from State agencies: Observe the harder advice in order to stop the spread of COVID-19. Read more on webpage Krisinformation.”

- Link: none.

If you get a similar sms with a link, do not click.”11

As earlier, replies to the tweet attack the sender, its competence, and judgement: “I honestly wonder if there is one, who believes that this sms will have an inch of effect. How many tax millions this kidsfest cost? Cheaper, better, more effective would have been to send: Use a face mask that protects both you and the ones nearby.” Another goes: “Unbelievable. Not even this can you handle. Other countries have no problem. If you now succeed, which can be doubted, why does this come so darn late? Apparently because Eliasson and the government are involved.” Most replies show direct attack of the person or authority identified with the tweet—and the effects are felt even in Krisinformation's replies, one of which directly asking “What have we done wrong now..?”12 Yet, besides attacks on persons, there are also replies that appropriate the context of the original tweet and twist it ironically. One reply goes: “If this is the teaser/trailer I don't think I will wanna watch the movie.”

In our material, irony emerges as the dominant device for appropriating reported speech. For Voloshinov, such ironic appropriation of the context of the original Tweet is a way of passing an evaluative judgement of the content, which in this case turns the great efforts of pandemic management by the government into a failed movie trailer. Irony is here understood as turning away from the intended meaning and creating infinite indeterminacy (De Man, 1996); in Voloshinov's discussion on reported speech this infinite indeterminacy is achieved by manipulating the context of the original tweet through different techniques of replying and quote-tweeting. Similar appropriation of the context is evident in a number of other replies. Most replies to Krisinformation's video clip about Corona-angst13 point out that it is not the angst that is the problem, but the Corona virus causing the angst. Similarly, when FHM on December 30th, 2020, announced that they will recommend the use of face masks from January 7th, 2021 onwards,14 many replies twist the context by wondering whether masks are not effective before January 7th, or in other ways point out the arbitrary timing of the recommendation. Replies by appropriating the semantic or temporal context of the tweet and by introducing elements of irony into the relationship between the original tweet and its uptake are able to render the meanings in the tweets indeterminate—and their senders to appear as incompetent and out of control of the events.

Among the most quote-tweeted tweets, we find the one on mass-SMS as well as the one on open schools and children's health. The quotes of the SMS-tweet provide an interesting case of comparison between a reply and a quote-tweet. One quote-tweet wonders if the point is to “verify if the SMS is genuine by comparing if the content is exactly the same as a text you have received by other means?!” Another one laments: “Oh Lord, wash your hands is no longer included. Disappointed” and a third twists the context even further: “I think I will also start to twitter my sms before I send them.” Again, the common topic of the tweets is summarized as “Information feed about the Monday's COVID-sms is certainly bigger than the information contained in the sms. So, that makes it then one more successful information campaign, right?” Many quote-tweets also refer to the replies the tweet has generated: “I send a thought to all who work with replying to the criticism against the sms, including among others, in this thread. Factual and polite, but at times unnecessarily hard words.” Quote-tweets are thus able to detach the meaning of the original tweet and turn attention to not what is said, but how it is said, thus making the Twitter feed the focus rather than what is referred to in those tweets. Again, the act of reporting as Voloshinov understood it, embeds the original message and its sender into a new context wherein the original meaning acquired a new, and often ironic, content.

The examples here have shown that Twitter replies and quote-tweets are often used to criticize the government agencies and the Swedish Corona strategy. In a Voloshinovian sense both are forms of reported speech that incline toward criticism. This will be elaborated on below.

In the last part of the analysis, we will be zooming in on specific days, in order to show what kind of events or tweets trigger interaction in Twitter and reveal the practices of constructing and contesting digital authority. In the whole analyzed period, the top ten daily peaks for interacting, i.e., mentioning, retweeting, quote-tweeting or replying one of the four governmental accounts in tweets, inclusive retweets, are in the range of ~1,700–2,500 Twitter actions. Of these daily peaks, five are in the middle of March 2020 and one in April 2020, confirming the identified general peak in March-April 2020. The other four peaks are on December 14th, 2020, February 9th, 2021, and March 17th and 26th, 2021.

The peaks of March 2020 fall into a period of general interest in the Corona crisis, later daily peaks can often be explained with specific events. The tweets on March 15th, 2020—the highest peak in our data—deal with various COVID related issues, most tweets from December 14th, 2020—another peak—refer to the “sms to the people” that was sent by Krisinformation and FHM to the whole population. Other daily peaks were formed by individual tweets that were retweeted overproportinally, such as on March 26th, 2021, when a tweet in English by a Swedish biostatistician working in the US mentioned FHM. Its retweets count for 75% of the total ~2600 tweets and retweets for that day.15 The peak on March 17th, 2021 is directly connected to communication strategies of Krisinformation. The day before, Krisinformation's Twitter account was managed by “Marie,” who, in contrast to previous practice, actively searched for tweets mentioning Krisinformation and replied to them in an ironic and non-chalant style. “Marie's” replies have now been removed, but screenshots are still available. Here an example:

Hej [Name removed]! It is difficult to give a full answer to your somewhat unclear question in just 280 characters. As you call yourself an Angry Man on the Internet, perhaps that suffices also as an answer? That is, to be angry? And then you can enjoy being just that. Hopefully it feels better tomorrow! Cheers, Marie.16

“Marie” used a similar style in other replies on that day. The following day, when Krisinformation after protests had to apologize for their communication, Twitter became filled with support for “Marie” and hashtags such as #jesuismarie and #backamarie emerged.

Whilst irony has been successful in parodying the government accounts, the same does not go the other way around. Legal-rational authority, here exemplified by “Marie,” is limited to the context of the legal-rational state. “Marie's” attempt to appropriate the context of the tweet as something posted by “an Angry Man on the Internet” does not produce ambiguity, but an official apology from Krisinformation. Yet, once the legal-rational authority had acknowledged its mistake, the response from the public could be ironic again: hashtags like #jesuismarie did rendered Marie's faith ambiguous: misunderstood and unfairly persecuted voice of conscience or a parody thereof?

For Weber, authority is a relationship. It is an attribute based on traditional or legal-rational grounds, or due to exceptional personal characteristics. Zürn's concept of reflexive authority, on which the idea of digital authority is based, focuses on the reasons for subjecting oneself to rule: the recognition of one's own (epistemic) limitations. Our material shows that much of the contestation of the legal-rational authority that in Weber's account is attributed to charisma takes the form of irony. Irony is certainly nothing new to politics, but social media communication with the legal-rational authority of the state is a contemporary phenomenon. Recent research on alt-right has placed irony among the key terms of political analysis, seeing in it traits of ambiguity, affective group building as well as mainstreaming racist and misogynist language (Nikunen, 2018; Askanius, 2021) in stark contrast to more philosophical (Rorty, 1989) or literary (de Man's, 1996) interpretations of irony as something liberating and critical. For de Man, irony cannot be defined, because it is an interpretative practice, an attitude toward the text; and ironic text is something that constantly “turns away” from the meaning.

For Voloshinov, the question in this regard would be how does irony appropriate the reported speech. As an interpretative practice toward authority, irony in our material thwarts the idea of public communication and turns official tweets into individualized playgrounds of verbal wittiness, drawing on personal experiences and preferences. Irony plays out on two fronts: in the verbal appropriation of government tweets, and in the situational context (for instance in FHM's acknowledgment that herd immunity strategy was based on miscalculation). The first we call verbal irony and the latter situational irony (Muecke, 1980). The manipulation of context as the main strategy of ironic appropriation of reported speech detaches the context of reporting from the real situation, thereby lending the ironic reported speech an aura of objectivity.

We can further probe the effects of irony on authority. For Voloshinov, different techniques of reporting speech mark different stages of literary evolution; change from one form of reporting speech to another is always also a question of changing power relations at the level of the (literary) system: new techniques are challenging earlier dominant ones. The same can be applied to authority in politics. Consider for instance the reply “ TRANSPARENCY

TRANSPARENCY ” quoted above. It essentially repeats what FHM tweeted earlier, but places FHM's “transparency” in a new context, that of a sham transparency, reduced to procedural steps bereft of substance. Yet, at the same time, “transparency” is pointing out the disguised political dimension in the scientific expertise of FHM. The same goes for many other cases of reported speech, such as replies asking FHM to define “child” or demanding respect for the elderly, where irony discloses the political content of something that is presented as stemming solely from scientific evidence. Irony affects authority also in so far, as it discloses a “real problem” that hides behind what the state agencies present as their problem. For an example, consider the replies to Krisinformation's advice not to read the news to avoid Corona-angst that point out that any fear is caused by the virus itself, not the reports about it.

” quoted above. It essentially repeats what FHM tweeted earlier, but places FHM's “transparency” in a new context, that of a sham transparency, reduced to procedural steps bereft of substance. Yet, at the same time, “transparency” is pointing out the disguised political dimension in the scientific expertise of FHM. The same goes for many other cases of reported speech, such as replies asking FHM to define “child” or demanding respect for the elderly, where irony discloses the political content of something that is presented as stemming solely from scientific evidence. Irony affects authority also in so far, as it discloses a “real problem” that hides behind what the state agencies present as their problem. For an example, consider the replies to Krisinformation's advice not to read the news to avoid Corona-angst that point out that any fear is caused by the virus itself, not the reports about it.

In our material irony does not function as a medium of critical and reflexive interaction with government agencies. Following Voloshinov, the ironic appropriation of government tweets indicates a shifting power dynamic where the authoritative perception of the government tweets has decreased as a result of growing appropriations that blur and trivialize government policy. For Voloshinov, such effects of reported speech are brought about by the changed social relations of power prevalent in the medium of communication—irrespective of any individual intentions in the act of reporting. In contrast to Rorty's irony and Zürn's idea of reflexive authority, there are no signs that irony generates reflexivity, critical distance, and growing awareness of one's own epistemic boundaries in our material; irony has the function of challenging the system.

This article has explored and elaborated on the interactive dynamics of “digital authority.” Gortitz et al. conceptualized digital authority as the interaction in which a certain Twitter—or social media—account is engaged. Yet, their operationalisation of this interaction was just a metric sum of all interaction with the underlying logic that all publicity is good publicity. Viewing digital authority through Voloshinov's theory of reported speech, we could unveil different dynamics that aggregate metrics disguise.

Twitter's different forms of interaction can be classified as either enabling spreading tweets considered as authoritative information or appropriating tweets, putting them in a new context and reporting them further with a new intention and new content. These functions of reported speech are properties of natural communication, explicated by Voloshinov in the 1920s and found still relevant in the algorithmic Twittersphere of the 2020s. They reveal that even in the era of social media, human interaction is able to claim the technological affordances and use them to pursue avenues of reported speech that have long preceded those technological solutions. This is our modest contribution to the emerging ways of looking at social media as an interactive medium. The contrast we found between the metrics of digital authority and the qualitative dynamics of digital authority points toward the need to treat social media as a form of human interaction—mediated by certain technological affordances but not limited to them. This entails including both the quantitative and qualitative dimension in the analysis of social media.

Through our integrated qualitative and quantitative analysis, we can observe a decline of the authority of the state agencies. As the crisis prolongs, the retweeting of government tweets decreases, signaling a diminishing “authoritative relation” to these accounts and their content. Instead the interaction with these accounts takes place in the form of replies and quote tweets rather than retweets. Following Voloshinov, we have shown how retweeting establishes an authoritative relation to the original message and may therefore be conducive to authority, while replies and quote-tweets embed the original tweet in a new context and often infuse it with irony. This creates ambiguity and undermines the legal-rational foundations upon which state agencies base their public communication. In other words, as the crisis prolongs what is perceived as the authoritative content from the government accounts decreases and what is taken as material for retort and ridicule increases. Similarly, what is retweeted extensively toward the end of our data period are tweets that are critical of the government position.

Voloshinov provided us with the insight that changing patterns of reported speech are indicators of ongoing contest over relations of power in society. A recurring theme in our data is the ironic or parodic depiction of legal-rational authority's conduct as procedurally correct but substantively empty. This may be caused or at least be fuelled by Swedish attempts to keep scientific expertise and political responsibility distinct from one another, as herd-immunity, open schools, or no masks are policies that rely as much on expertise as on political stance. Claiming the opposite has become the prime target of ironic appropriations in different forms of reported speech that contest legal-rational authority during COVID-crisis.

The data further shows that whilst irony has turned out to be an effective strategy for the public to appropriate government messages, the same does not work for a legal-rational authority. Most often irony is perceived as a force to counter any authority—a theme developed both in literature and philosophy—but in recent years irony has become a banal excuse for politically incorrect rant. For Rorty, irony can serve as a critical force that renders the contingency of any conviction apparent (Rorty, 1989). This would enable a realization of one's epistemic limits, something that Zürn's concept of reflexive authority builds upon. For Zürn, the conscious subjugation to authority is possible in face of acknowledgment of one's own limits of knowing, yielding to recognition of authority's superior competence. There seems to be two different kinds of irony, Rorty's liberal irony that reveals one's contingency and the more recent irony of dilettantism and consequent cynicism (Grimwood, 2021). The problem here for a legal-rational authority is that Twitter allows for an easy fusion of verbal and situational irony, i.e., verbal wittiness and situational events perceived as ironic. To counter that, legal-rational authority needs to prove its ongoing engagement with events on the ground, much like Rosanvallon's observation that the legitimacy of authority must be demonstrated and it is earned post-hoc.

Finally, this article has shown that communication in social media, although regulated by all powerful algorithms, nevertheless yields to classical qualitative textual analysis. All too often the medium of social media is conceived of in (solely) technical terms muddling the human action that it conveys. Big data has diverted social media analysis to confirming correlations between variables that perhaps lack an obvious relationship substituting content with the volume of data. The common turn to “metrics” as an indication of different social relations is an example of that. Looking at the “volume of interaction” more closely and with a Voloshinovian perspective reveals clear patterns of human interaction through Twitter. The technological affordances of Twitter do affect communication, but they do not render it a meaningless mass. This finding—currently based on one case study and focusing on individuals' relations to public authorities—opens a new potential way to operationalise digital authority. For example, future quantitative undertakings to measure authority in the digital space could differentiate between retweets on the one hand and replies and quote-tweets on the other. One could further refine the operationalisation of such studies by considering the distinction between replies and quote-tweets where the former tends to undermine the authority of the sender whilst the latter the credibility of the content. Such quantitative follow up studies are essential to corroborate the theory.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval were not required for the study in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The data was sourced in accordance with the institution's Twitter API licensing agreement.

JT and SW are the main authors. WA-S provided Mecodify support, collected and organized the empirical data, and contributed with expertise on Twitter. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^Other observers have noted the lack of prior experiences of more serious societal crises (Häyry, 2021), political overreaction to the 2009 swine flu pandemic (Anderberg, 2021) as well as personal clout and convictions of key decision makers in the Public Health Agency (Andersson and Aylott, 2020).

2. ^There has been some doubt as to Voloshinov's real identity. Some authors, especially in the 1980s and 1990s have argued that Voloshinov is just Mikhail Bakhtin's alter ego. Especially Michael Holquist in Dialogism. Bakhtin and His World (1990) has championed this position. However, more recent research has supported separate identities of all Bakhtin circle scholars—Mikhail Bakhtin, Valentin Voloshinov, and Pavel Medvedev. For a detailed discussion, see Brandist, C. (2002). We do not deem it necessary to take part in this debate and accept the authorship of Voloshinov as it is stated in the book.

3. ^To exemplify this point, reporting the speech “Well done! What an achievement!” [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930), p. 128] cannot be done by simply repeating the words in a reported speech: “He said that well done and what an achievement” [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930), p. 128]. Instead, to try to convey the meaning of the original speech, the reported speech must interpret its context and alter the message accordingly: “He said that that had been done very well and was a real achievement” [Voloshinov, 1973 (1930), p. 128]. Both cases show that reporting somebody's speech inevitably also introduces power relations into the act of reporting.

4. ^Here we would briefly like to mention another subcategory, which evolved due to certain mechanisms on Twitter. A quote-tweet further distributes the original tweet and addresses/informs the originator, even if the framing has changed. Often this is intended, although for a various number of reasons. Sometimes, however, neither any interaction with the original tweeter nor the further distribution of his/her tweet (beyond the own followers) may be desirable. The “screenshot quote-tweet” provides a solution. It is technically an original tweet, that includes the image of another tweet which most often is critical, negative, scornful, and avoids spreading the message of the original tweeter, even excludes him/her from the conversation, and is directed to one's own followers.

5. ^In recent years, replies to one's own tweet have become a method to circumvent the character-length limit of individual tweets, allowing the tweeter to open a “thread” that contains many replies to the original tweet. Twitter eventually added a threading feature that makes this approach more formal as it allows influencers to write a rather long textual message with relative ease, although some prefer using the image uploads (e.g., readable images of formal letters).