- Université de Lausanne, Institut d'études politiques (IEP), Lausanne, Switzerland

The article addresses the methodological challenges in measuring democratic ideals on an individual level in quantitative studies. Building upon own empirical research, the study identifies several difficulties in assessing individuals' attitudes on democracy. In addition to a discussion of quantitative measures on individual-level data such as the ESS module on democracy or the Afrobarometer measures, the study assesses the possibility of other endeavors and what these look like. The study identifies multidimensionality, the association between elements, as well as problems in aggregating concepts, as important elements to be addressed in research. In the last step, certain quantitative measures are tested through a survey to show possible solutions to the issues.

Introduction

Extending research on the meanings of democracy measured on an individual level (Schedler and Sarsfield, 2007; Shin, 2017; Frankenberger and Buhr, 2020; Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2020; Quaranta, 2020; Davis et al., 2021), this paper discusses the possibility of measuring attitudes of democracy on an individual level using quantitative methods. This reflection realized in a survey conducted between July and December 2020 to test different methodological elements. The study poses the question: What do we measure when assessing individual level democratic ideals through survey-methodology? It seeks to combine measurement problems with theoretical premises to identify a viable solution to the problem of measuring democracy consistently across individuals and countries. The aim is to orient better methodological choices in line with theory and question design for both, within country and comparative studies. Gaining more insights into how democratic meanings influence political participation (Bengtsson and Christensen, 2016) is important to better understand mobilization processes. This enters not only into the debate of how mobilization is motivated (e.g., against inequality) but also on what ideal of democracy is promoted by political parties (e.g., populist parties). In addition, knowing more about democratic ideals helps comparing and understanding configurations in different political systems as well as country-level democratic polarization. Finally, it allows comparing people's ideals with how a political system is configured. Detailing more on ideals of democracy can orient theoretical debates on democracy and notably discuss between dominant strains (e.g., liberalism) and democratic ideals held by fewer people.

The article examines three elements and discusses their implications for measuring democracy on an individual level in line with existing and new measures. Those elements are not new, but are important for the design of any research. First, I discuss democracy's multidimensionality as a concept. This discussion includes the fact that measures need to be as open as possible to account for different attitudes on democracy, but at the same time ensure that they are valid and comparable. Second, I discuss the association between elements of democracy with the argument that, to account for a more valid understanding of different attitudes on democracy, it is important to contextualize elements by looking at their relations. Third, I discuss the possibility of aggregating sub-elements consistent with the way democracy is measured quantitatively, and the related problems with multidimensional concepts. After outlining theoretical challenges, the article proposes two additional steps: It outlines different ways to operationalize the theoretical challenges and finally applies those as part of data from own research.

In this article, I focus on the ideal of democracy as an element of political attitudes. Hence, I am more interested in assessing the way a democracy should look from an individual perspective (democratic ideal) and not in evaluating the current political system's performance. Although somewhat similar challenges apply, it is important to underscore that I focus more on such questions as “What is important to you?” than on “How do you evaluate?” I focus first on the state of the literature to illustrate challenges that apply to measuring democratic attitudes, before associating that literature with measures of democracy. In the last section, I propose several preliminary results from a survey with 1,110 participants from three countries.

Literature review

Measuring democracy, or more concretely, attitudes toward democracy, has a long tradition; however, what has been analyzed has changed more and more. Notably, the “meanings of democracy” approach to its measurement demands better measurement of the way democracy is perceived (Schedler and Sarsfield, 2007; Shin, 2017; Frankenberger and Buhr, 2020; Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2020; Quaranta, 2020; Davis et al., 2021). Amidst growing criticism, notably of the famous “satisfaction with democracy” question in international surveys (Canache et al., 2001; Shin, 2017), new measures are developed in an effort to differentiate between different understandings of democracy. This is an important part of today's research agenda, as Shin (2017, p. 2) summarized: “The capacity to make such a differentiation is a crucial component of an informed understanding of democracy.”

What defines democracy

It should come as no surprise that democracy is a case of contested concepts as Gallie remarked already in 1955. He outlined that democracy is not only appraisive, but also internally complex, with different components in which necessary and sufficient conditions are discussed (Gallie, 1955-1956). Today, scholars agree that democracy is a contested concept with even contradictory definitions and understandings (Schmitter and Karl, 1991; Croissant, 2002; Coppedge et al., 2011; Lauth, 2011; Coppedge, 2012; Burnell, 2013; Vandewoude, 2015; Giebler et al., 2018).

Democracy is a generic term that describes a variety of political systems that are signified as “government of the people, by the people and for the people” as stated in Lincoln's Gettysburg address (Lincoln and William, 1909). There is continuous interest in a minimal definition of democracy. Although we have seen above that different forms of democracy exist, there are certain elements that researchers perceive are shared in common. Scholars focus normally on fair and secret elections and universal franchise as minimal elements, as well as guarantees of political freedom, fairness, justice, deliberation, and political rights, while procedures, transparency and context dependency are additional elements (Dahl, 1989; Schmitter and Karl, 1991; O'Kane, 2004; Bermeo and Yashar, 2016; for a good overview on elections' role, see Hadenius, 2008). Other scholars talk about dimensions: e.g., rule of law, vertical and horizontal accountability, competition, freedom and equality, responsiveness, and participation have been identified (Lauth, 2011, 2013). Scholars use equally different typologies or adjectives to distinguish among democracies, for example electoral, liberal, majoritarian, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian (Collier and Levitsky, 1997; Coppedge et al., 2011).

Liberal democracy is discussed a great deal today. Its core elements are elections (and the choice between alternatives), representation with binding rules based on equity, pluralism, and tolerance, as well as freedom of association and speech, self-determination, responsibility, and the control of the government (Bobbio, 1988; Bauzon, 1992; O'Kane, 2004; Coppedge et al., 2011). Other forms, such as deliberative democracy, focus to a greater extent on processes, participatory democracy, or direct democratic ways to exert influence, and egalitarian conceptions on redistribution of resources (Coppedge et al., 2011). While it would be easy to choose one of these concepts of democracy, it is unlikely that a single definition can capture the multiple understandings that individuals assign to democracy in different countries.

Constituent elements for its measurement

The question of constituent dimensions of democracy illustrates the multiple approaches well, and has generated at least some agreement among scholars. Lauth summarized the dimensions of political freedom and individual political equality as necessary elements of democracy and regarded political control consistent with the rule of law as a third dimension (Lauth, 2010, 2011, 2013; Lauth and Schlenkrich, 2018). Scholars who have analyzed indices of democracy argue for the existence of two axes; however, their names differ. Munck and Verkuilen (2002) discussed contestation or competition and participation or inclusion, Hadenius (2008) used elections and political liberties, and Bowman et al. (2005) discussed political liberties and political rights. In addition, whether democratic output should be used to evaluate a democracy is contested (Lauth, 2010, 2013). Lauth argued that a “trade-off” between different dimensions of democracy exists and ideal democracies cannot realize political liberty and equality, and political and judicial control completely at the same time (Lauth, 2013; c.f., Lauth and Schlenkrich, 2018, for a renewal of the argument on the dimensions' interdependence). Coppedge et al. (2011) adopted a similar perspective, and stated that conceptions of democracy, such as liberal or majoritarian conceptions, can conflict with each other. This association shows the requirement not simply to assess which elements of democracy individuals believe are important, but also to account for the perceived interactions among concepts.

When defining democracy, one can use rather limited concepts that focus on elections (Przeworski, 2010), or can opt for larger concepts with several dimensions, such as the Quality of Democracy approach, and several other competing definitions, such as Varieties of Democracy, the Democracy Barometer, Democratic Audit, and many more. The definition one applies influences which elements/variables to select for deductive studies to a considerable extent. It equally makes cross-study comparisons more difficult, as there is no single widely accepted definition with, respectively, widely available data that follow the same logic. The underlying problem is epistemological in nature. By choosing a selective approach, such as on elections only, one can easily miss other dimensions. This is why I argue for the quality of democracy approach, because it is open to many perspectives and is applicable widely. Consistent with the way democracy is defined, I discuss in the following how multidimensionality, the association among concepts, and possibly aggregation, influence the way democracy is measured.

Multidimensionality

Researchers today agree that democracy is multidimensional (Dahl, 1989; Coppedge et al., 2011), yet there is still no consensus about which dimensions should be included. This multidimensionality indicates that there is not one democratic ideal within society, but several, which is reflected in the research on democracy's quality (Bühlmann et al., 2014; Lauth and Schlenkrich, 2018). The approach to its quality assesses not only degrees, but also types of democracy, simultaneously. According to the multidimensional concept, democracy consists of different dimensions, such as control, equality, and freedom, to take one example (Beetham, 1994), that are more or less developed in different political systems. The dimensions include elections, equal participation, or individual liberties, among others.

However, applying this definition still poses measurement problems. The concept is in sharp contrast to the very general, undifferentiated technique that many international surveys use to evaluate democracy (Canache et al., 2001; Ferrin and Kriesi, 2016; Boese, 2019). To increase feasibility, many studies opt for greatly reduced approaches to democracy. As a consequence, only a few studies have used multidimensional concepts of democracy because it necessitates including many different variables (Ferrin, 2012; Bengtsson and Christensen, 2016; Ferrin and Kriesi, 2016; Kriesi and Morlino, 2016; Heyne, 2018). As democracy takes different forms in different countries, perceptions of it differ as well (Schedler and Sarsfield, 2007; Heyne, 2018), which is another reason that multidimensional measures are necessary.

First, it is crucial to not ask excessively general questions. As outlined above, a question that asks “How important is democracy for you” will be understood differently in different countries (Heyne, 2018), but also by different people. Thus, with respect to validity, it is essential not to include this question, except perhaps in interviews to begin the debate. It is definitely possible to ask questions about democracy's dimensions in interviews, as research has shown (Refle, 2019; Frankenberger and Buhr, 2020). However, this means that we descend at least one level and do not ask questions about democracy in general, but more concrete questions about minority rights, for example, to capture multiple dimensions.

I argue here that even when one adopts a minimalist definition of democracy, it is worth taking a more open approach that can be used to assess several of its perspectives. Leaning on qualitative approaches, this could mean using more inductive or open approaches, while in quantitative approaches, large batteries of questions are necessary to capture a maximum of different understandings. Reducing the operational definition of democracy is also possible once the data are established; however, expanding it can become difficult when questions are posed only on democracy or freedom in general. In this sense, I argue for measuring the maximum number of attitudes possible—within the limits of practical elements such as time for answering a survey—and making these data available to all scholars to allow every research perspective to test it. It is furthermore of importance not to focus on the main ideal of democracy, that will be often liberal democracy in Western countries, but to equally assess the differences in its understanding as well as challenging concepts of democracy.

While I proceed with examples from quantitative research, it is possible to apply similar questions in interviews without greater problems. It is necessary to note that respondents will not answer all questions, but will return to the aspects that are most important to them. Keeping this in mind, it is likely that respondents to quantitative surveys will also skip certain questions or simply respond with a neutral value because of limited conceptions of democracy. Those shortcomings of surveys led Frankenberger and Buhr (2020) to conclude that quantitative surveys are inherently inappropriate to assess what democracy means to citizens. Still, I argue that in case of neutral and reduced conceptions, it is useful to assess what items differ from averages for which individuals or groups of individuals. In addition, it is useful to know how many items are valued by respondents, a question that I will come back to with a new question type for the analysis of meanings of democracy.

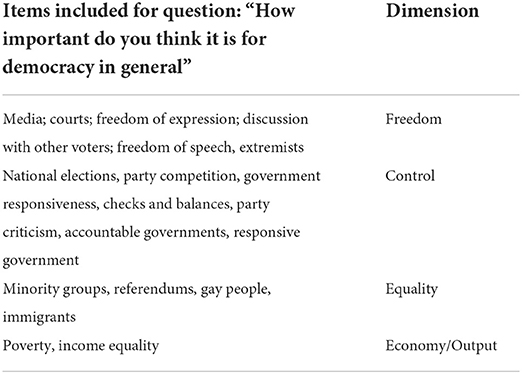

The European Social Survey (ESS) from 2012 actually made a good start, but it is still focused a great deal on elections and less on equality-oriented elements. The new questionnaire from the ESS 2020 module on democracy is more streamlined on liberal democracy. It still has the advantage that it covers several subdimensions and is available already (European Social Survey, 2012, 2018). Among the different elements included in the ESS 2012 are those questions on the importance for democracy1 shown in Table 1.

As the reader may have noticed, the categorization mentioned above is the author's proposition, but something such as equality before the court can be subsumed easily under the equality dimension too. This problem of association will be addressed in the next section. However, the ESS questions' advantage is that they cover not only questions on elements' importance, but also on the way people perceive the situation in the country. This distinguishes between the respondents' actual and ideal perception; however, it is equally part of the problem as respondents get questions with nearly-similar wording two times during the survey.

Still, the questions themselves posed in the ESS are not without problems. Questions that are poor with respect to response rates to the ESS include one that it is important to prevent people from expressing extreme political views, whether the government is formed by a single party, or whether it ignores the people. For example, while < 20% of the total sample responded in Germany and Switzerland, the situation was different in the United Kingdom (UK), where only the question on preventing people from expressing extreme views posed problems. Still, it shows that some questions on democracy, particularly when formulated inversely toward autocracy, evoke social desirability bias that needs to be addressed to provide accurate results. The problem is less relevant to the positive perspective on democracy, where it is more a problem of distinguishing between high levels of support, as outlined later.

While economic elements are often included indirectly in measures of democracy (e.g., in the Democracy Barometer, Bühlmann et al., 2014) by measuring corruption or economic elements' influence, the way individuals integrate economic elements into their conception of democracy is an open question because of the absence of research on the topic. Therefore, in every individual-level measure of democracy, researchers should reflect carefully whether to integrate economic elements or not. Consistent with the open approach advocated earlier, economic elements should be integrated into the data collection at least, leaving it up to every researcher to choose whether or not to include them. Nevertheless, even if economic elements that are associated with democratic output are not included in a theoretical framework, it still appears a good idea to at least control for them in quantitative studies.

As discussed above, the ESS 2012, which was repeated in 2020/2021 in a reduced form with focus on liberal democracy, is a good starting point not only for quantitative, but also qualitative, endeavors that could use similar questions. It illustrates well the influence of, for example, electoral democracy definitions, in which the control dimension is overrepresented and the equality dimension under-represented. Other researchers therefore relied on either the World Value Survey2 (Shin, 2017; Davis et al., 2021) or the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study that however already dates from 2009 (Quaranta, 2020). I add carefully, that according to each scholar's definition, other scholars might subsume the question of equal treatment before courts under equality rather than freedom. This shows that depending upon scholars', but more importantly, individuals' interpretation as well, elements fall under different categories, which is why I argue that it is important to show the association between elements.

Association

Based upon my own research (Refle, 2019), I argue that it is important to identify different elements' association. My qualitative research showed not only that interviewees talked more easily about elements of democracy than about democracy in general, but also that they associated different elements in different ways. One example is the state's monopoly of power. While some people see the monopoly of power as important in democracy, as it allows extremism to be fought, a different perspective sets it in conflict with individual freedoms that can become restricted in a too powerful state. Another example is equality before courts, which can fall under freedom because it guarantees freedom, but can also be seen from an equality perspective, in that everyone is treated in the same way. Thus, it becomes important to account for this differential association in future research, because it shows meaning construction on an individual level. The pure assessment of individual elements' importance, as performed in the ESS in 2012 and 2020/21, can give an overview of what dimension or items are evaluated, but this type of question cannot assess the relations among elements.

While it is difficult to identify best practices, it is easier to retrace association in interviews, because it allows for a fine-grained analysis of connected elements. Another option that is not the most suitable, is ranking the most important elements in democracy as performed in the Afrobarometer3. In Round 6, the Afrobarometer used a question about what democracy means to respondents to which they could make three responses that indicated their three most important priorities. In combination with a list of proposed items, respondents could indicate what item has the first, second and third priority and could indicate positive and negative aspects such as corruption, government change and peace for example. However, this variable becomes complicated to interpret as one is faced with much diversity among priorities. Respondents do not simply evaluate the most important elements according to their attitudes, but also associate elements indirectly, because they normally mention the three most important elements that they would connect. However, this is not ideal, because normally is not always and depends upon individual thinking; they can also mention elements that they perceive are unrelated. Further, it is not always straightforward to rank items and can introduce a non-response error for the questions that follow.

Another option that I tested is allowing respondents to assign points to individual elements of democracy according to their conception of them. In this question type, the respondent is asked to distribute 100 points freely. The respondent can distribute all 100 to one element or to different elements according to his/her priorities. This more flexible assessment has a number of advantages, because it is easier to identify what elements are clustered and whether few or many elements are important to respondents. The results from this test can be found in the empirical section of this article.

While I view association between elements as an important element that distinguishes different conceptions of democracy, many problems on a measurement level to be solved in the future. Still, the problem of interaction is associated with another challenge, the question of aggregation.

Aggregation

Aggregation (vertical integration and summary in main dimensions) is another important challenge and is consistent with the way one conceptualizes democracy's necessary and sufficient conditions. As outlined with reference to Gallie (1955-1956) above, democracy scholars continue to find it difficult to agree on these dimensions. The trend was toward more flexible measures in the past decade or approaches that do not determine necessary and sufficient conditions for democracy, or approaches that are only consistent with very specific concepts.

In the past, a number of scholars, including Dahl (1989) or Przeworski (2010), used models of necessary and sufficient conditions to analyze democracy. Similarly, Goertz (2006) discussed necessary and sufficient conditions. The discussion continued later under the label of the quality of democracy, or can be found in international indices in which different indicators form dimensions. However, this has not gone unchallenged: Scholars working on democratization and the gray zone in between democracy and autocracy argued to abandon necessary and sufficient conditions (Tilly, 2000). As any cut-off point would be arbitrary (O'Donnell, 2010). As a contested concept, it is doubtful whether there will be one solution, as the different names applied in aggregate-level studies show. While flexible solutions can be envisaged in inductive research, it causes problems for more deductive quantitative studies, because it will be difficult to determine categories for items. A preference here could be given to specific approaches consistent with respective concepts, such as measuring only deliberative democracy, but that limits generalization and creates a barrier to democracy scholars working with other concepts.

Accordingly, I propose a mixed solution. The problem of elements' association, as outlined above, makes aggregation difficult because the same element can be viewed from different perspectives and have different meanings. A simple aggregation of two, three, or four dimensions depending upon the perspective subsumes different meanings under the same label and undermines individual-level measures' validity. Factor analysis of a quantitative survey can prove useful here, because connections between items get identified. Equally cluster or later class analysis will provide useful insights. Still, there will remain tensions between theory and measurement. One example are factor loadings for factor analysis that may differ from not only one country to another, but even from one group of individuals to another (thinking about populist voters who conceptualize democracy differently and would subsume items under different dimensions). Thus, on a technical level, aggregation may be possible, but difficult to justify, and quasi-impossible as a multidimensional concept even though theorized differently. However, when analyzing measures of democracy, it is possible to account for specific interactions as an element of groups of people's conceptions, which Ferrin (2012) did with the ESS data. The solution would be to collect data that are as open as possible to different aggregations, but that can be ordered easily after the data are collected.

For practical purposes, I also apply the 3-fold division between control, equality, and freedom. Still, we cannot simply aggregate sub-dimensions without adhering to one tradition of democracy, indicating that as a multidimensional concept, we should be satisfied with keeping variables at the end. The disadvantage of this is that we are faced with a large number of variables to analyze. Thus, it is important to identify interactions for specific groups of people (e.g., activists in social movements or voters for specific parties).

There is another problem when considering attitudes. One will find either simple affirmative statements across respondents, or missing information on all dimensions of democracy, as individual-level conceptions will be fragmented and normally not comprise all elements of democracy, likely because of educational level or knowledge of the topic. As democracy is assigned several meanings across individuals and countries, the best course is to try to re-group these meanings. In the experimental section of this study, I outline the way factor analysis can contribute to this effort, as well as the way measures may account for simplistic perceptions.

It is necessary to manage aggregation with caution; however, it is useful for communication, as it is easier to talk about the subdimensions rather than lower levels, as some elements will remain empty. Here, such qualitative data collection procedures as interviews have the advantage that people talk, will not respond to all elements, and will relate elements in their answers automatically. On a technical level, quantitative analysis can proceed the inverse way and regroup attitudes once the data is collected. In this sense, aggregation seems here less of a problem than association between items. What I propose in the following is a suggestion on how to construct surveys on attitudes toward democracy with the aim to generalize across the population and/or groups of people.

Empirical testing

The second part of this study discusses a survey conducted to address those problems on an empirical level. I used the questions on what is important for democracy the ESS developed already, but supplemented them with additional questions derived from the 3-fold distinction between the control, freedom, and equality dimensions, and included economic elements as well. Twenty nine Items were used, of which 11 were original ESS items and the remaining either modified items from the ESS or new questions based on the operationalization of the Democracy Barometer4 and World Value Survey indicators. As the ESS is a general survey, the number of items that is included is naturally limited to fewer ones. In addition, the distinction between ideal and existent configuration in the ESS does not help in my view as it repeats the same items with different wording which may cause confusion among respondents. Consequentially the focus is on the democratic ideal and not on ideals and actual configuration.

This survey for this article was conducted using Facebook recruiting with paid ads and obtained an N of 1,110 participants. While the original design focused on four countries (Switzerland, France, Germany, and the UK), relatively few respondents from France were included ultimately because of problems with data collection. Hence, the final dataset consisted of 488 respondents from the UK, 355 from Germany, 166 from Switzerland, and 101 from France. Detailed analysis will be provided only for the UK, Switzerland and Germany, because the n for France was relatively low. The survey was conducted between July and December, 2020 and is obviously not representative and needs further verification with a better sample.

The survey was prepared in Limesurvey and hosted on university servers. Thereafter, I used advertising on a Facebook page to recruit potential participants. The recruiting was oriented toward the general public, but was supplemented later with recruiting by gender because it became clear that more men participated initially. The questionnaire began with a question on voter rights in each country and then proceeded with some basis demographic information, such as age and educational level. Because of the already clear difficulty of one question in particular, it was expected that some of the experimental questions could cause attrition, so that certain basic sociodemographic variables (gender, education, and age) were posed at the beginning to verify whether educational levels, for example, influenced attrition5. The following sections included one in the style of the ESS questions on “How important is it for democracy that…” with questions on the following dimensions: 7 on freedom; 8 on equality; 10 on control, and 4 on economic. The following part then used the Afrobarometer priority question in which respondents could rank different democratic elements. In the following, I tested a new question in which respondents had to attribute exactly 100 points to different items. The last section asked general questions, such as party voted for, political activism, interest, trust, and the like, as well as region of residence. As no incentives were given, the first questions attracted much higher response rates than did the latter. This was clear toward the end of the survey, because political participation values were particularly high for those who finished the survey. This indicated that those who are politically active were more likely to finish the survey. This means also that the first questions on importance are more representative than the latter questions, which are more valid for those more interested. Representativeness for the general population is not given and a discussion of some of the socio-demographics is found in the Appendix.

In presenting the preliminary results, I add cautiously that further testing, verification, and replication are necessary to ensure the results' accuracy. The results that are presented in the following are largely descriptive and require further multivariate verification. I distinguished between general results across countries (including all 1,110 respondents), and country-specific differences. Exploratory factor analysis without rotation serves as base model and was performed across all items and within each dimension. Then component matrices were compared to identify items that are constituent to dimensions and the overall concept. To detail more, inter-item correlations were used to identify items that are associated positively or negatively. To verify on possible links to other key variables, one-way ANOVA were performed to make the underlying conceptual differences more tangible. These appear to be useful because they identify the underlying conceptual similarities, and underscore items that are included in different concepts or that are contrary to conceptual expectations simultaneously.

Results

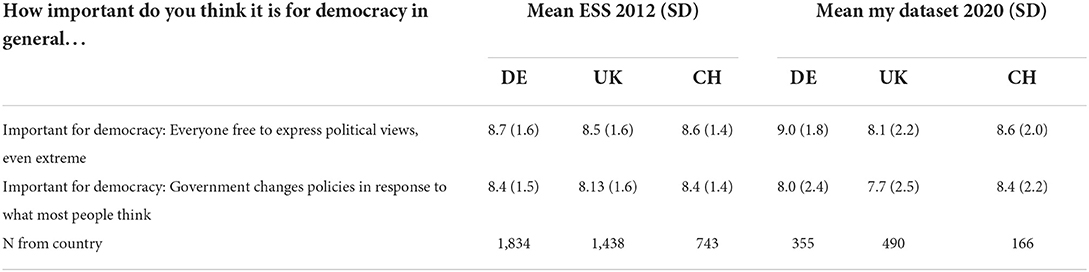

This section is divided into three parts. The first discusses the ESS-like question's important elements, the second assesses the priority question, and the third discusses the new points-based question. The Table 2 verifies whether the results are consistent with other datasets. Here, I presented two questions that were posed in exactly the same way. We can see that the means for both items are similar to those measured in the ESS 2012, but do not overlap completely. In general, the standard deviation is higher in my dataset, which may be an indicator of increased polarization or may also indicate a potential bias, which can be verified ultimately with the ESS 2020/2021 results, once published. I also note that the ESS question on freedom of expression is based upon only a few respondents for each country because of many missing answers. With a questionnaire based only upon democracy, it is possible to augment the response rates for this item, as I had response rates of nearly 100% for this and the other questions.

This is a very strong argument to use not only democracy-related questions in a general survey, but to conduct separate surveys on democracy alone, because it can increase the response rates significantly and allow better analysis as a result. In addition, contrary to the ESS, answers for each block of questions were randomized, such that the preceding questions were less likely to influence them.

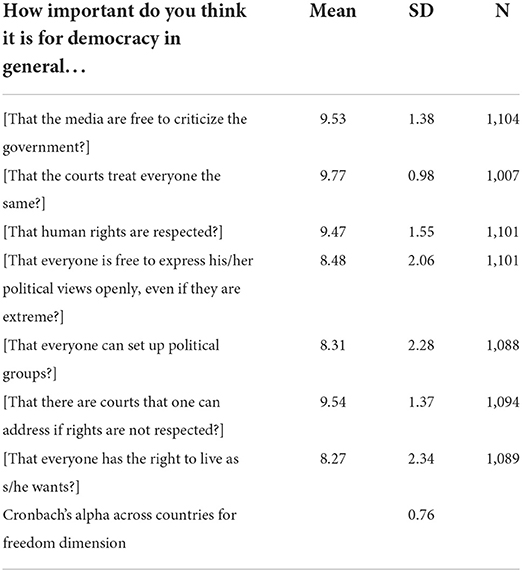

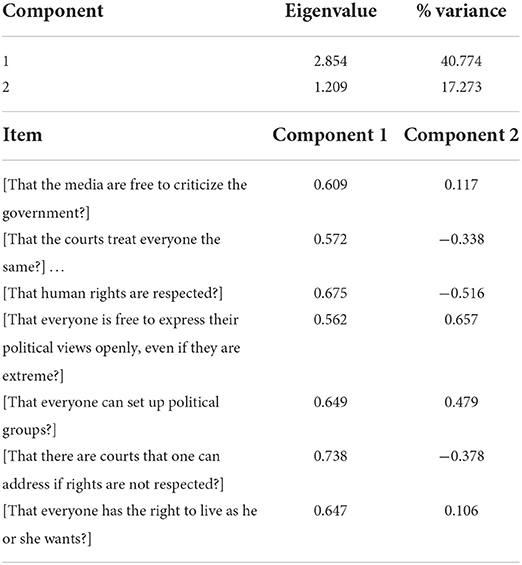

Table 3 gives an overview of the freedom-related items from my survey. The same problem as in the ESS questions emerges: The means on the 10-point scale are very high. It means that inferring priorities from differences toward averages is more complicated, because measurable differences are relatively small. While the questions themselves do not pose problems with respect to response rates, they have to be analyzed with techniques for skewed data. In the following, I refer to factor analysis to account for the underlying association of concepts that is able to identify patterns despite skewed data.

Further, I verified whether these items are correlated and whether they allow for aggregation. The Cronbach's alpha for the freedom questions is relatively high given that several sub-dimensions are included. A factor analysis showed that freedom's first factor loading was 41%, the second 17% (Appendix Table 8, annex). It is notable that all items that include the words court or human rights were associated negatively with the first dimension, indicating that those items represent another conception to respondents, at least in part.

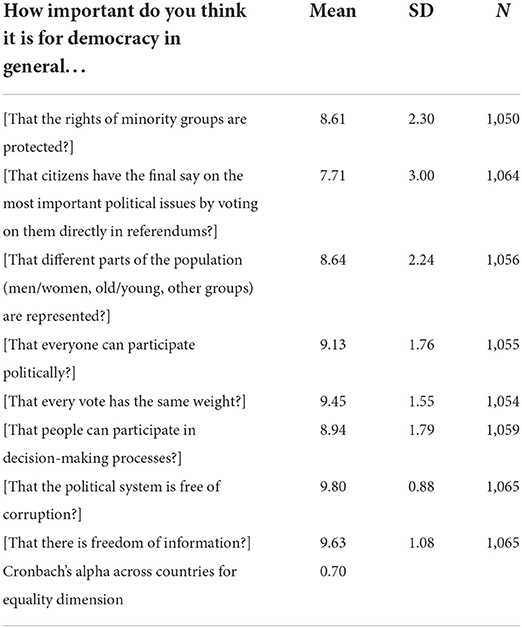

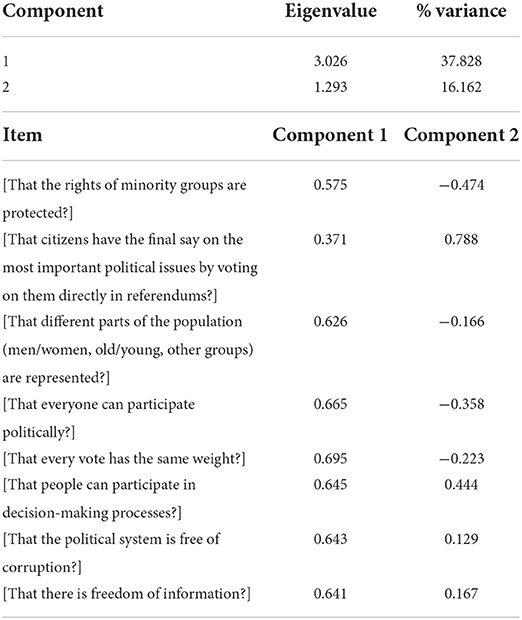

For the equality dimension, Table 4 shows largely the same problems of skewedness, in which one item, direct democracy, scored particularly low. As will be shown later, this was influenced by the UK's value, which was low for direct democracy.

However, an analysis of covariance showed that there was a negative correlation between the item on direct democracy and minority rights, which was the only case of a negative relation. For the second battery of questions on equality, the first factor loading accounted for 38% of variance, and the second for 16% (Appendix Table 9, annex). With respect to the freedom dimension, several minor loadings accounted for between 5 and 12% of the variance. The second dimension appeared to show an over- or under-emphasis on certain groups, notably minority groups, and the items on minority rights, representation of groups equal participation, and equal vote count demonstrated negative correlations.

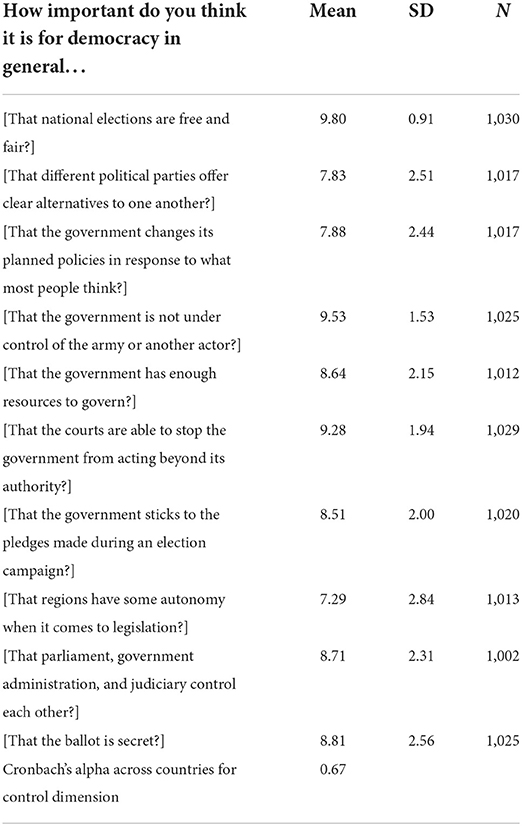

Table 5 shows the responses for the control dimension, in which again, three items had means below 8 on a 10-point scale. Federalism, party politics, and government responsiveness had particularly low means. At the same time, this indicated more polarization in those items, as the standard deviations were higher than for other items.

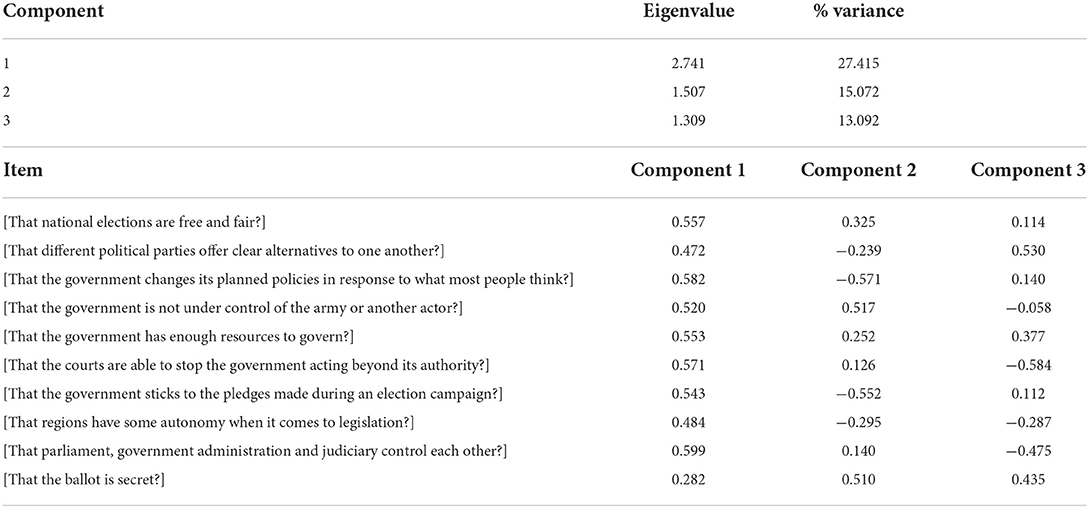

The Cronbach's alpha for the control dimension was lower than for the other two dimensions, but relatively high for a multidimensional concept. Still, it is notable that this derived in part from the inclusion of the secret ballot, which was correlated negatively with two other items. The exclusion of this item increased the Cronbach's alpha to 0.69. Controlling with a factor analysis showed three major dimensions. The first had a factor loading of 27%, the second, 15%, and the third, 13% (Appendix Table 10, annex). The first dimension was related positively across all items, in which the secret ballot was slightly less important. This was the control dimension. The second dimension concerned the items on government responsiveness, but was associated with political alternatives as well. The third dimension represented other actors' control and correlated negatively with the items “not under control of other actors,” as well as “courts controlling” and “separation of powers.” However, that the ballot is secret was not related significantly in many cases. Thus, it appears that this item has a different dimension.

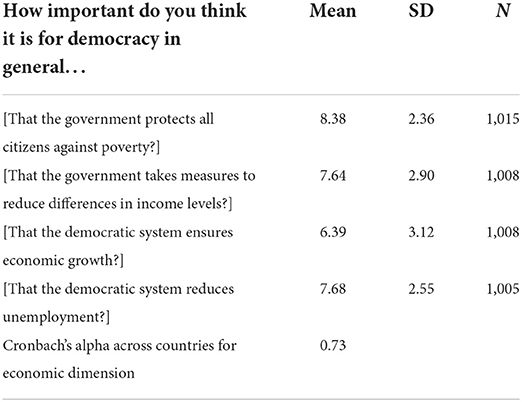

Table 6 shows the economic dimension, which is disputed theoretically with respect to whether it is a constitutive element of democracy or a related dimension. Except for the government protecting its citizens from poverty, the respondents agreed in general that those items are less important for democracy itself.

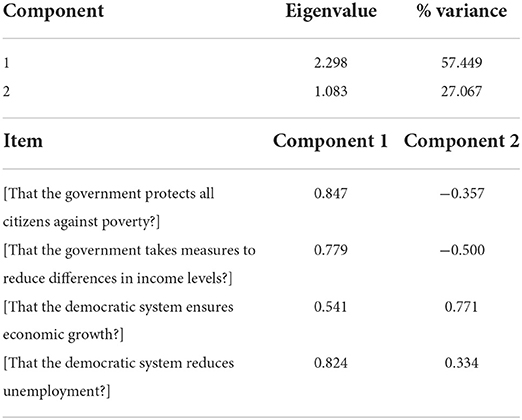

The economic dimension had a Cronbach's alpha of 0.73, and the factor analysis revealed two major dimensions. The first factor loading explained 57% of the variance, while the second loading explained 27% (Appendix Table 11, annex). Notably, the second concerned the questions of poverty and equality.

The Cronbach's alpha for all items (freedom, equality, control, economics) combined was 0.86. Nearly all items were correlated positively across all countries combined; negative correlations were very rare and included the secrecy of the ballot twice and the minority rights/direct democracy interaction once. The latter can be seen as a sign of polarization between majoritarian and minority rights-oriented approaches.

Taking all items of democracy together except those on the economy, the first factor loading accounted for 26% of the variance. Further, there were five additional factor loadings that each explained 4 and 9% of the variance. The first dimension is democracy itself, which had positive effects on all variables, although the variable for the secret ballot had the smallest effect, followed by clear party alternatives and citizens having the final say. From the perspective of all respondents across countries, these three items were democracy's least important elements. This also illustrates the multidimensional nature of the concept well.

The second factor loading was associated with direct democracy, but also minority rights and the one person, one vote principle. This perspective emphasizes that citizens participate directly and majoritarian decision-making, and de-emphasizes minority rights and equal participation. The third perspective focuses on representation, while the fourth focuses on freedom of speech, transparency, and participation. The fifth dimension resembles the third, but focuses more on individual than collective participation. The sixth dimension focuses on a strong government that is able to rule without control; it de-emphasizes the control-related elements and emphasizes individual participation at the same time.

While multivariate analysis's utility is yet to be revealed, a more complete assessment of different dimensions of democracy provided certain promising results that can be used in comprehensive studies on democracy in the future. The batteries of questions are especially useful when it comes to identifying multi-dimensionality and the possible aggregation of items. It equally gives some ideas on associated items.

Question on priorities

It was theoretically possible to select 23 priorities, but the respondents were not forced to do so. Practically, ~32% did not answer this question at all, which showed that the question was more complex than the first and the respondents were less willing to answer after the first batteries of questions. Another 10% stopped after the fifth priority; overall, 50% responded up to priority 7, while priority 8 had more missing than valid responses. This continued until the 23th priority, which only 6% answered.

The problem with this question is that it poses difficulties for interpretation. While it offers certain ideas about the most important priorities on a descriptive level, as shown below, all possible combinations are not necessarily included, for example civil liberties get combined with peace. Thus, not even the first priorities give a consistent picture, and require a more detailed interpretation. Still, the question was useful in interpreting country differences, which were more visible between the UK, Switzerland, and Germany. While civil liberties and equality and justice, for example, played very important roles in Switzerland and Germany, more government-oriented aspects took top priorities in the UK.

Because of the data's non-numeric nature and the fact that the answers were ordered by priorities, not items, this question required considerable recoding after data collection. The priorities question showed somehow useful for identifying what items get valued, but are much less useful for interpreting associations or aggregation. Still, there are simpler ways to obtain an even better result, which is why I continue directly with the points-based question.

Ideal democracy question

The experimental survey design included a question on the ideal democracy, and respondents could assign 100 points freely to “construct” their ideal democracy: Note that the respondents were forced to assign exactly 100 points and were unable to continue the survey if the score was not equal to 100. As a consequence, this question created additional attrition compared to the previous question. Here, there were ~35% missing answers across all four countries, which increased to 40% from the following question onwards.

However, the question proved very useful in developing the respondents' democratic profiles, because it showed the relative distribution the respondents assigned to each category. Table 7 shows the mean points assigned to each item. This allowed the important elements in each country to be identified and thus fulfilled the same function as the previous question on priorities, but was much easier to interpret. As it was ordered by items, the mean number of points assigned to each item could be interpreted easily, and showed that the respondents value direct democracy, human rights, free conduct of life, and equality before the law, particularly in Switzerland. In Germany, human rights and free conduct of life are valued particularly. Elections as the “core” of democracy figured relatively low in both countries. The UK illustrated country-specific differences, as no corruption, human rights, freedom of speech, and equality before the law are valued most. At the same time, this procedure allowed attitude profiles to be built. Despite the 35% missing answers, the interpretations were still not overestimated because the most interested respondents finished the questionnaire. Further, it is a quite promising measure of democratic ideals on an individual level. It was also useful that few respondents had only one top priority to which they assigned 100 points. Thus, the question's responses were also relatively easy to aggregate because the items could be merged easily.

The Cronbach's alpha across items was 0.88 over the countries, which was highly comparable to the values for the questions on the items' importance. The factor analysis revealed that the concept of democracy overall is the main concept that explained 37% of the variance across countries, and all items were associated positively with this concept. The second concept explained only 6.7% of the variance and included minority orientation and human rights, and de-emphasized electoral democracy. The third concept accounted for 6.5% of the variance and was freedom-oriented.

While it remains to be seen whether additional items should be included or some items should be more detailed, the question appeared to be useful to establish profiles of democratic meanings across countries as well as specific groups of people (such as party adherents). For example, it allowed the differences between items for voters to be identified.

When looking at respondents close to the “Alternative für Deutschland” (Afd) in Germany as an example, we find significant differences for the items “direct democracy” and “equality before the law” when comparing with all other German respondents6. When all people who perceive that they are close to right wing populist parties [e.g., Schweizerische Volkspartei (SVP), AfD, Brexit party, Rassemblement National (RN)] are taken together, it is possible to contrast them more, and significant differences in direct democracy, human rights, freedom of speech, equality before the law, participation of all groups, minority rights, and economic growth were found that showed the potential to associate specific democratic ideals with parties. In addition, this same exercise can be applied for other party families, such as conservatives, social democrats, or green parties. Still, the differences are arguably stronger when the extremes, such as the right-wing populist parties mentioned, are contrasted with others.

Another element concerns the reduced conceptions that some people hold. The points-based question takes those into account easily with a large dataset. Still, it allows assessing the way people responded to this question on average. When examining the dataset that was collected for the pre-study, three types of respondents answered the points-based question: People who assigned points to only one or a few items (e.g., 60, 30, 30, or 100 for one item), those who used approximately five items, e.g., (5*20) and those who assigned points to all items (e.g., 2, 6, 10, 3, and so on). This is one of the advantages compared to the question about the items' importance, as the social desirability bias to assign the highest value to all appears to be lower. It still might appear to be desirable to assign some points to all items that are mentioned in the list. The points-based question revealed promising results and allow an easy distinction between attitudes held by groups of people.

Conclusion

The article exploited different options of measuring democracy on an individual level following a three-steps procedure: Outlining theoretical challenges of a contested concept, linking theory and existing measures, and illustrating results generated from those measures. First, I discussed multidimensionality, association between concepts, and aggregation as challenges for survey methods. Beginning with democracy as a disputed concept that does not have one definition, but several, several problems arise: It is not only multidimensionality, but also challenges of horizontal and vertical integration of the conception of democracy that make it difficult to agree upon one measure of democracy. Thus, the ideal is to examine detailed and open concepts that are still parsimonious. However, parsimony should not lead to a reduction in variables that could be useful from other perspectives. On a measurement level, we have seen that the ESS 2012 and 2020 with its module on democracy helps account for multidimensionality. However, my own data showed that more detailed accounts for every dimension and specific surveys on attitudes of democracy have their advantages when several perspectives—and not only liberal democracy—shall be assessed. It includes a strong argument for stand-alone surveys for measuring meanings of democracy.

When implementing several ways of measuring democracy, the results confirmed the complexity of the concept. In effect, the main concept of “democracy” is just one of several important concepts that are revealed through different types of questions. Over all items, the concept “democracy” had one factor loading that explained only 26% of the variance. However, the following factor loadings explained up to 17% when economic elements were not included. The challenge for quantitative measures is to identify how items are associated in order to identify the underlying concepts. Notwithstanding to how items are associated horizontally, the problem of vertical association is largely unproblematic from a statistical perspective. Thus, it is useful to keep many items that may measure several perspectives and test for the association among them to identify different groups of people's specific conceptions of democracy.

Existing questions to measure democratic meanings on an individual level are currently underperforming. Either are the results heavily skewed like for the ESS questions, making interpretation difficult because respondents tend to indicate importance across all items, or are associations between items not clear. Existing questions on democracy invite social desirability to express that democracy is good and it might be worth experimenting with other research designs that reduce social desirability. Current measures of democracy propose solutions to measuring multidimensionality, but not association between items. Assessing associations may be easier with interviews or focus groups, as Frankenberger and Buhr (2020) underscored.

As one possible solution, I tested a point-based questions that has several advantages, but one major disadvantage: It led to some additional attrition among those less interested in politics. It may be possible to reduce this attrition by placing this question earlier, but another explanation is that those with missing or incomplete conceptions of democracy had difficulty answering it. Still, advantages lie on practical levels, in that it is simple to illustrate differences across countries. In addition, it opens manifold options for new research. First, by comparing different averages attributed to items, specific conceptions of e.g., right-wing populist (like tried by Bengtsson and Christensen, 2016 using the ESS), but also other voters can be established. Similarly, this can open up to other political actions, such as activities in different types of social movements and charities, depending on how democracy is conceptualized. Furthermore, in a normative perspective, it allows to check what dominant meanings exist among ordinary citizens. Comparing with aggregate data is can allow to identify items where the political system is configured differently from how citizens would see it. Finally, a comparison across political systems can also help accounting for polarization within a country when only few contradicting concepts are dominant among a country's population.

As well as the caveats evoked already with respect to representation, it is notable that the used dataset has several persistent problems. With the higher attrition toward the end, the analysis related to political activism and whether it shapes conceptions of democracy, was difficult. Some party-specific comparisons were still possible, showing the potential of linking meanings of democracy to political actions such as voting. While the used data does not allow for a wider generalization as it was implemented for question testing, the author is convinced that similar patterns arise with representative data and that can be implemented in the future.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.swissubase.ch/en/catalogue/studies/14095/18025/overview.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

Open access funding was provided by the University of Lausanne.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Section “E” in ESS Round 6, https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/round6/fieldwork/source/ESS6_source_main_questionnaire.pdf. Section “D” in ESS Round 10, https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/round10/questionnaire/ESS-Round-10-Source-Questionnaire_FINAL_Alert-06.pdf.

2. ^Q 235 onwards are partly selected as additional items, https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV7.jsp.

3. ^Q29a, https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/tun_r6_questionnaire.pdf.

4. ^https://democracybarometer.org/data-and-documentation/

5. ^An overview on the questionnaire is available upon request.

6. ^Respondents that indicate being close to the AfD attribute an average of 16.15 points to direct democracy [Standard Deviation (SD) at 21.42, chi2 sig at.01] compared to 4.92 (9.05) for others, for equality before the law the average is 4.9 (SD 5.97) compared to 10.69 (11.28), chi2 sig. at.05, n for both questions = people close to Afd 40, others: 196.

References

Bauzon, K. E. (1992). “Introduction. Democratization in the third world – myth or reality?,” in Development and Democratization in the Third World. Myths, Hopes, and Realities, Ed K. E. Bauzon (Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis),1–31.

Beetham, D. (1994). Defining and Measuring Democracy. Sage Modern Politics Series, Vol. 36, sponsored by the ECPR. London; Thousand Oaks, CA; New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Bengtsson, Å., and Christensen, H. (2016). Ideals and actions: do citizens' patterns of political participation correspond to their conceptions of democracy? Govern. Oppos. 51, 234–260. doi: 10.1017/gov.2014.29

Bermeo, N., and Yashar, D. J. (2016). “Parties, movements, and the making of democracy,” in Parties, Movements, and Democracy in the Developing World, Eds N. Bermeo and D. Yashar (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 1–27.

Boese, V. A. (2019). How (Not) to Measure Democracy. Int. Area Stud. Rev. 22, 95–127. doi: 10.1177/2233865918815571

Bowman, K., Lehocq, F., and Mahoney, J. (2005). Measuring political democracy. Case expertise, data adequacy, and central America. Comp. Polit. Stud. 38, 939–970. doi: 10.1177/0010414005277083

Bühlmann, M., Merkel, W., Müller, L., Giebler, H., and Weβels, B. (2014). Demokratiebarometer-Ein Neues Instrument zur Messung von Demokratiequalität. Available online at: http://www.democracybarometer.org/Images/Demokratiebarometer_Konzept.pdf (accessed July 9, 2014).

Canache, D., Mondak, J. J., and Seligson, M. A. (2001). Meaning and measurement in cross-national research on satisfaction with democracy. Public Opin. Q. 65, 506–528. doi: 10.1086/323576

Collier, D., and Levitsky, S. (1997). Democracy with adjectives: conceptual innovation in comparative research. World Polit. 49, 430–451. doi: 10.1353/wp.1997.0009

Coppedge, M. (2012). Democratization and Research Methods. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Fish, S., Hicken, A., et al. (2011). Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: a new approach. Perspect. Politics 9, 247–267. doi: 10.1017/S1537592711000880

Croissant, A. (2002). “Demokratische grauzonen: konturen und konzepte eines forschungszweigs,” in Zwischen Demokratie und Diktatur. Zur Konzeption und Empirie Demokratischer Grauzonen, Eds P. Bendel, A. Croissant, and F. W. Rüb (Opladen: Leske and Budrich), 9–53.

Davis, N. T., Goidel, K., and Zhao, Y. (2021). The meanings of democracy among mass publics. Social Indicat. Res. 153.3, 849–921. doi: 10.1007/s11205-020-02517-2

European Social Survey (2018). The European Social Survey. Round 10 Question Module Design Teams (QDT) Stage 2 Application. Available online at: http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/round10/questionnaire/ESS10_ferrin_proposal.pdf (accessed May 18, 2022).

European Social Survey (2012). Source Questionnaire, Amendment 01. Available online at: https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/round6/fieldwork/source/ESS6_source_main_questionnaire.pdf (accessed February 15, 2022).

Ferrin, M. (2012). What Is Democracy to Citizens? Understanding Perceptions and Evaluations of Democratic Systems in Contemporary Europe. Available online at: http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/25196/2012_Ferrin_Pereira.pdf?sequence=1andisAllowed=y (accessed May 18, 2022).

Ferrin, M., and Kriesi, H. (2016). How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frankenberger, R., and Buhr, D. (2020). ‘For me democracy is…' Meanings of democracy from a phenomenological perspective. Zeitschr. Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 14, 375–399. doi: 10.1007/s12286-020-00465-2

Gallie, W. B. (1955-1956). Essentially contested concepts. Proc. Aristotelian Soc. 56, 167–198. doi: 10.1093/aristotelian/56.1.167

Giebler, A., Ruth, S. P., and Tanneberg, D. (2018). Why choice matters: revisiting and comparing measures of democracy. Politics Govern. 6, 1–10. doi: 10.17645/pag.v6i1.1428

Heyne, L. (2018). The Making of Democratic Citizens: How Regime-Specific Socialization Shapes Europeans' Expectations of Democracy. Swiss Political Science Review. Available online at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com

Kriesi, H., and Morlino, L. (2016). “Conclusion – what have we learnt, and where do we go from here?,” in How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy, Eds M. Ferrin and H. Kriesi (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 307–325.

Lauth, H.-J. (2010). Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der Demokratiemessung. Zeitschr. Staats Europawissenschaften 8, 498–529. doi: 10.5771/1610-7780-2010-4-498

Lauth, H.-J. (2011). Qualitative ansätze der demokratieforschung. Zeitschrift Staats Europawissenschaften 9, 49–77. doi: 10.5771/1610-7780-2011-1-49

Lauth, H.-J. (2013). “Core criteria for democracy: is responsiveness part of the inner circle?,” in Developing Democracies. Democracy, Democratization, and Development, Eds M. Böss, J. Møller, and S-E. Skaaning (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press), 37–49.

Lauth, H.-J., and Schlenkrich, O. (2018). Making trade-offs visible: theoretical and methodological considerations about the relationship between dimensions and institutions of democracy and empirical findings. Politics Govern. 6, 78–91. doi: 10.17645/pag.v6i1.1200

Lincoln, A., and William, H. (1909). The Gettysburg address. when written, how received, its true form. Pa. Mag. Hist. Biogr. 33, 385–408.

Munck, G. L., and Verkuilen, J. (2002). Conceptualizing and measuring democracy. evaluating alternative indices. Comp. Polit. Stud. 35, 5–34. doi: 10.1177/0010414002035001001

O'Donnell, G. (2010). “Illusions about consolidation,” in Debates on Democratization, Eds L. Diamond, M. F. Plattner, and P. J. Costopoulos (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University), 23–40.

O'Kane, R. H. T. (2004). Paths to Democracy: Revolution and Totalitarianism. New York, NY: Routledge.

Osterberg-Kaufmann, N., Stark, T., and Mohamad-Klotzbach, C. (2020). Challenges in conceptualizing and measuring meanings and understandings of democracy. Zeitschr. Vergleichende Politikwisssenschaft 14, 299–320. doi: 10.1007/s12286-020-00470-5

Przeworski, A. (2010). Democracy and the Limits of Self-Government (Cambridge Studies in the Theory of Democracy). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Quaranta, M. (2020). What makes up democracy? Meanings of democracy and their correlates among adolescents in 38 countries. Acta Politica 55.4, 515–537. doi: 10.1057/s41269-019-00129-4

Refle, J.-E. (2019). Civil Society and Democratic Framing in Tunisia. How Democracy Is Framed and Its Influence on the State. Available online at: https://serval.unil.ch/resource/serval:BIB_3F44A9F93F05.P003/REF (accessed August 19, 2021).

Schedler, A., and Sarsfield, R. (2007). Democrats with adjectives: linking direct and indirect measures of democratic support. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 46, 637–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2007.00708.x

Schmitter, P. C., and Karl, T. L. (1991). What democracy is … and is not. J. Democr. 2, 75–88. doi: 10.1353/jod.1991.0033

Shin, D. C. (2017). Popular Understanding of Democracy. Oxford: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.80

Tilly, C. (2000). Processes and mechanisms of democratization. Sociol. Theory 18, 1–16. doi: 10.1111/0735-2751.00085

Vandewoude, C. (2015). “A universal understanding of democracy,” in Non-Western Encounters With Democratization. Imaging Democracy After the Arab Spring, Eds C. K. Lamont, F. Gaenssmantel, and J. van der Harst (Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate), 9–30.

Appendix

Representativeness of the dataset

Slightly more men than women participated (49.3 to 48%, while the remainder did not respond or indicated other), the distribution in education was 1.2% with primary school only, 18.1% with secondary school, 43.8% Bachelor's degree or three years' vocational training, and 33.3% with a master's degree or similar or higher. The respondents' average age was 59 years, indicating that older people were more likely to participate. When looking at the country level, respondents from the UK were slightly more likely to be men (51 to 46%, the remainder no answer or other), with an average age of 59 years. No respondents indicated that primary school was their highest level of education. The average age of respondents in Germany was 49 years, and female respondents were over-represented slightly (54%) compared to men (44%). There were fewer people with a Bachelor's degree or similar, but slightly more with a secondary education or master's degree or higher. The Swiss respondents were much younger on average, 43 years. 51% of the respondents were female, 46% male. Approximately 46% indicated that they had a Bachelor's degree or similar, and much fewer than in the other countries responded that they finished only secondary school. Still, this is consistent with the predominance of vocational training in Switzerland. While those indicators showed already certain potential biases with respect to representing the population overall, it may denote equally that the sample was restricted to Facebook users, which constituted an additional caveat. However, as the idea was to test different question types for survey research, it is still an acceptable deviation from a representative sample. As the second part of the survey yielded much fewer responses (only 658 for the first non-democracy-related question), it is difficult to estimate other potential biases. However, the question about respondents' interest in politics showed that 92% indicated at least a 5 on a 10-point scale. In combination with the question on political activities, in which the values for different political activities (particularly in comparison to general surveys such as the ESS) were relatively high, those who were politically most interested did finish the survey, while others dropped out earlier. Fortunately, educational level did not seem to affect attrition, so that the difficulty of new questions was unrelated to education, but attributable to political interest.

Keywords: democracy, conceptions, measures, attitudes, individuals, quantitative data, survey research

Citation: Refle J-E (2022) Measuring democracy among ordinary citizens—Challenges to studying democratic ideals. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:934996. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.934996

Received: 03 May 2022; Accepted: 26 August 2022;

Published: 03 October 2022.

Edited by:

Lauri Rapeli, Åbo Akademi University, FinlandReviewed by:

Fredrik Malmberg, Åbo Akademi University, FinlandAino Tiihonen, Tampere University, Finland

Copyright © 2022 Refle. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jan-Erik Refle, amFuLWVyaWsucmVmbGVAdW5pbC5jaA==

†ORCID: Jan-Erik Refle orcid.org/0000-0003-3732-4108

Jan-Erik Refle

Jan-Erik Refle