- 1Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle, Germany

- 2Department of Sociology, European University at St. Petersburg, St. Petersburg, Russia

- 3Higher School of Economics, St. Petersburg, Russia

A backlash against liberal gender and sexuality attitudes has been an issue in many societies, especially post-Communist. However, it takes a different shape in each socio–cultural context. This article contributes to academic debates about neo-traditionalism in the post-Soviet space and focuses specifically on Armenia. It points at some possible mechanisms that make these societies look more neo-traditionalist than they actually are. From the previous research of gender aspects of nationalism, we argue that the neo-traditionalist public discourses in Armenia might be a by-product of the national identity construction. We conclude that the individual-choice attitudes in the post-Soviet space may reflect the respondents' acceptance of a national ideology promoted by the post-Soviet elites rather than their private practices. Our aim is to reveal the complexities of neo-traditionalism in the post-Soviet space where everyday practices are at odds with neo-traditionalist narratives, which we argue might be a result of the Soviet legacy of unwritten rules and open secrets.

Introduction

Gender backlash is often presented as a global phenomenon. Indeed, the campaigns against gender equality are run by conservative governments and other actors around the world who mobilize various social groups, resulting in anti-abortion laws in Poland and Hungary and anti-gender movements in the US and Latin America. This is also a prominent trend that is often observed in the post-Soviet space. What such movements have in common is that they all claim to struggle against what they call the “gender ideology.” Reproductive rights, along with sex education, same-sex marriage, and the very notion of gender (as opposed to biological sex) are at the center of cross-national debates (Paternotte and Kuhar, 2018, p. 8). However, it is important to consider the local particularities in each case of gender backlash.

Post-Soviet gender issues in the past decades are often characterized by such terms as “conservative turn,” “re-familiarization,” or “maternalism” (Mahon and Williams, 2007). The regional specifics vary from the religion-charged national revivals in Central Asia (Kandiyoti, 2007) to the rise of masculinity in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus (Johnson and Saarinen, 2013; Riabov and Riabova, 2014; Bureychak and Petrenko, 2015). World Values Survey and the European Values Study data collected in post-Soviet countries show that those states, with a notable exception of Baltic countries, demonstrate less gender egalitarianism than any other society of comparable wealth and educational level (Inglehart and Norris, 2003), and less progress in the recent decades than expected.

Armenia may be considered a model case of the gender backlash in the post-Soviet space, as it exemplifies the deep contradictions observed in the region. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Armenia has become a part and parcel of the anti-gender trend observed in the post-Soviet region:

“Armenia underwent a resurgence of neo-traditionalism and patriarchal patterns of behavior in the wake of the USSR's collapse. Gender equality and the inclusion of women in the public sphere were rejected as artificial Soviet impositions, and many nationalists, political conservatives, and members of the clergy described women's equality as being antithetical to Armenian values” (Cavoukian and Shahnazaryan, 2019, p. 730).

In the 1990s, the country experienced an immense economic crisis aggravated by warfare. The first Nagorno–Karabakh war began in 1988 and ended victoriously for Armenia in 1994. Border clashes have been on and off since then and until the second war in 2021, which ended with a victory for Azerbaijan. On top of that, the history of Armenia is full of tragic episodes that culminated in the 1915 Ottoman genocide that resulted in 1.5 million deaths, ethnic cleansing, and massive emigration. Armenians make one of the largest diasporas of around 4.5 million of full or partial Armenian ancestry compared to the current population of approximately 3 million people in Armenia proper (Cohen, 2008, p. 52). Its current territory is a fraction of historical Armenia, surrounded by two explicitly inimical states (Azerbaijan, and, to somewhat lesser extent, Turkey) with regular paroxysms of warfare at its borders, especially in the contested land of Nagorno–Karabakh. No wonder that nationalist sentiment and national pride are quite strong in Armenia. This is the backdrop of the rise of anti-gender attitudes and policies in the last three decades. The endangered project of nation-building has been used by the Armenian politicians since 1991 to reinforce the national identity, and such a stance is closely associated with pro-life discourse worldwide (Gal, 1994; Yuval-Davis, 1997; Smyth, 1998). In Armenia, this discourse is, indeed, very popular among both the politicians and the general public.

At the same time, seven decades of Soviet secularization and the policy of women's empowerment have left a deep imprint on Armenian society. Armenia is a case of relatively successful and rapid Soviet-style modernization in the twentieth century, which resulted in low fertility rates, high rate of female college attendance, urbanization, and cross-regional mobility. Formal parameters, such as total fertility rate, mother's age at first birth, divorce rates have not changed much in the post-Soviet period and are similar to those of modernized countries. Armenian women are active in the non-governmental sector and participate in political protest, democracy building and civil society initiatives (Ishkanian, 2005; Ziemer, 2020). The democratic forces in Armenia are vibrant such as multiple NGOs and civil society institutes, LGBT-and women-rights movements.

For this reason, we argue that the story of gender attitudes in Armenia is much more complicated than a simple return to the “Golden Age” of traditionalism after a failed Soviet modernization project. It rather looks like a number of trials in a quest for “creating new imaginaries of the nation that enhance social solidarity in increasingly fractured post-Soviet societies” (Kandiyoti, 2007). Eisenstadt notes that the conservative turn is in fact deeply modern even though it may wear a mask of traditionalism (Eisenstadt, 2000). In his book, “Multiple Modernities,” he posits that after the dissolution of large empires such as the Soviet Union, the emerging states shape their identities based on their ethnic or religious unity. It is a common way for post-imperial societies to constitute their nationhood by disavowing the empire's values and reverting to traditionalism in family life and public discourse. This is especially so when the new nation feels an existential threat or has a history of such a threat. Women and their rights to divorce, abortion, and premarital or extramarital sex are particularly vulnerable to the patriarchal discourse and policies in such a situation. However, what happens if those women are secularized and educated, familiar with contraception, and have had low birth rates for generations?

This article aims to take a closer look at and critically assess the gender backlash in Armenia. Our main argument is that Armenia is not as conservative as it may look. We intend to show and explain the many complexities of what is perceived as gender backlash in Armenia. We focus on freedom in sexual and reproductive choices, operationalized as justification of abortion, divorce, and casual sex. To illustrate our argument, we employ regression and latent class analyses of two waves of the EVS survey (EVS, 2020) to show that the national pride operationalized in various ways is the main (and almost the only) predictor of conservative attitudes. In the following sections, we will give more context on Armenia as a part of the Soviet project of emancipation, its post-Soviet transformations, and endangered nation-building, continue with data analysis, and proceed with discussion and conclusion.

Armenia as a post-Soviet society

A possible explanation of the anti-gender backlash is the Armenian government's distancing from the Soviet-era policies, which is typical for many nations that emerged after the collapse of the USSR. The dissatisfaction of women and men with Soviet gender policies existed already in the Soviet Union period but it became more acute and visible after the Soviet Union's collapse. This discontent evolved into support of more traditional gender roles in the context of national revival.

Armenia as a part of the Soviet Union was subject to Soviet gender policies. In the early twentieth century, the Soviet Union was one of the more progressive countries with respect to gender equality and sexual freedom. It implemented universal voting rights, mass education, and state programs of enhancing female labor force participation right after the 1917 revolution.

Historically, the Independent Republic of Armenia (1918–1920) granted women a right to vote and to be elected; 8% members of the parliament were women (Talalyan, 2020, p. 14). After the establishment of the Soviet power in Armenia in 1920, rape was criminalized and bride purchase was prohibited. Girls of less than 16 years of age were forbidden to marry. Women and men got equal rights to inheritance.

Thanks to the effort of the prominent Bolshevik Alexandra Kollontai in the early post-revolutionary years, Soviet women could make free decisions about marriage (or refrain from it), divorce, abortion, and premarital sex. Based on her approach, the Soviet Union managed to drastically change the peasantry's patriarchal norms in a couple of decades (Kollontai, 1977). The number of births started to decline even before the revolution, but the process had been slower than in other European countries until the Bolshevik reform accelerated it (Ashwin, 2000). Even when, due to Stalin's demographic concerns, abortion was illegal in the USSR (1936–1955); it was still performed secretly en masse. Most Soviet women of those generations reported to have experienced abortion at least once in their life. Many perceived it as simply a means of contraception (Westoff, 2005), which is reflected in astounding statistics; for example, 5.5 million legal abortions were performed in USSR in 1965, that is more than live births (Johnston, 2021). In the early 1970s, the abortion rate in Armenia stood at 45% of all pregnancies which is somewhat lower than in the USSR in general, but still extremely high (Johnston, 2021).

Regarding divorce, it had been available with a “no reason” explanation since 1918, while co-habitations were equalized with marriages in 1926. Divorce became somewhat less easy to obtain in 1936, as it then involved a fine and the necessary presence of both parties. It was made a public issue in 1944, as the parties had to publish a note about their divorce in local newspapers (Fitzpatrick, 2000). The divorce rate was relatively low right after World War II, but it had grown 10-fold by the mid-1970s, because of post-Stalin policy liberalization of the 1950s.

Despite some positive changes that the Soviet domination brought up to the Caucasus region, including the policies that allowed women more autonomy and choice in reproductive and sexual behaviors, inequality continued to flourish. In Soviet Armenia, men dominated the upper levels of government and the Communist Party and had better paying jobs to the extent that men's salaries were up to 5 times higher than those of women (Dudwick, 1997, p. 238–239; Ishkanian, 2005, p. 482). Furthermore, women carried a double burden as they had to work full time while being fully responsible for home chores and raising children.

Some resistance to radical change and in favor of the preservation of traditions in Armenia persisted throughout the Soviet period. In addition, the patriarchal gender roles were staunchly upheld within Armenian families, and were seen by many as a form of everyday resistance to Soviet social engineering (Matossian, 1962).

“Open secrets” as a Soviet legacy

An important feature that distinguishes post-Soviet societies is the legacy of Soviet informal practices and “open secrets.” The Soviet Union was a testing ground for various, often radical, social experiments. Its population experienced a broad variety of government interventions in their economic, religious, social, and sexual life. Moreover, those experiments sometimes made complete U-turns that negated the earlier official line, yet they were always accompanied by intensive propaganda. Therefore, not only did they deprive the majority of the Soviet population of their family traditions and religious roots, but of any ideological embeddedness whatsoever (Inkeles and Bauer, 2013). The policy zigzags eventually led to distrust of official proclamations and to mass escape into one's private life. When the state's prestige was relatively high, the dominant ideology was enthusiastically shared by the majority; on the contrary, during the regime's economic and moral decline, most people were very cynical about it.

Absent Stalin, the only carrier of the “objective truth,” the Soviet public life transformed so that the reproduction of the form and of the ritual became more important than the actual contents of public speech. In his ground-breaking study, Alexey Yurchak argues that after Stalin's death, the system experienced the standardization of official discourse, ubiquitous posters, and slogans were “common, identical, predictable,” the texts became “normalized, fixed, and citational (Yurchak, 2013, p. 37).” The support for the system was simulated in many intricate ways; a performative shift developed in the wake of Stalin's death (Yurchak, 2013). Participation in rituals was an indication of one's belonging to a collective. The performative aspect of public speech and rituals not only reproduced social and power structures but also carried a liberating function for their performers; as their loyalty was thus officially confirmed, the performers had more freedom for self-expression in other contexts. This enabled new unanticipated meanings in everyday life and created new forms of “freedom' (Yurchak, 2013, p. 37).

The prevalence of the following unwritten rules and informal practices in the relationship of citizens and authorities kept the system functioning: the planned economy could not function without people getting around its declared principles and depended on people who compensated systemic deficiencies by cutting corners and easing the constraints (Ledeneva, 2011, p. 726). One aspect of the unwritten rules is open secrets; according to Ledeneva, open secrets refer to the set of informal practices that are well-known but absent from the official discourse (Ibid.). They indicate a gap between the official discourse and the everyday practices. Open secrets require not only the common in-group knowledge of unwritten rules but also the ability to handle them, or tacit knowledge; the group's outsiders cannot know the secret. The open secret should remain unarticulated, “Open secrets occupy areas of tension, where a public affirmation of knowledge would threaten other values or goods that those involved want to protect” (Ledeneva, 2011, p. 725). The concept of open secrets can be understood as a conflict of interest between individuals and groups, as opposition to dominant social norms; they are relevant in social systems with contradictory nature. It is not a hypocrisy but a way for an individual to remain within the social order and at the same time oppose it, or allow some degree of emancipation from the system (Rossier, 2007).

The phenomenon exists in other societies, too; for instance, abortion is an open secret in Burkina Faso, where abortion is illegal in most cases (Rossier, 2007). This study shows that while women generally choose to keep their abortion secret, they nevertheless discuss it with their friends and relatives; thus, many people are actually aware of it.

The practices that are in the focus of our research—abortion, divorces, and premarital sex—are widely stigmatized and therefore not articulated in the official discourse in Armenia. The Soviet hypocrisy with respect to freedom in sexual and reproductive choices (Zdravomyslova, 2001) was also a characteristic of Armenia that talking about sex and sexuality, especially with women, was inappropriate. Although sex education was introduced in Armenia in 2004, sex and sexuality are still a controversial topic and often censored, especially for girls. This aspect has changed little since the Soviet times (Talalyan, 2020, p. 43).

At the same time, many indicators in Armenia show that the actual practice does not correspond to the discourse: abortion and divorce rates are high, hymenoplasty (plastic surgery for the hymen restoration) is popular, the mean age at marriage is steadily rising, and the mean number of children is steadily declining (Darbinyan et al., 2019). Although polls show that the overwhelming majority opposes freedom in sexual and reproductive choices, statistics show that abortion is widely practiced, whereas divorce and age at marriage are very close to the European levels. This discrepancy is the puzzle that drives this research. We believe it can partly be attributed to the Soviet habit of open secrets that the respondents tell outsiders (including researchers) the officially approved opinion regarding abortions, divorces, and premarital sex while reserving personal freedom for private conversations and actions. Just as in Yurchak's model of late Soviet society, we see a similar dynamic in post-Soviet Armenia that the reproduction of the official discourse opens possibilities for more freedom of action and new unanticipated meanings. Even if this is true, the question remains, why is the official (and public) narrative on pro-choice attitudes so harsh in Armenia?

The collapse of the Soviet Union made the ideological vacuum even more acute. Even those older people who used to honestly believe in the communist ideals faced the breakdown of the state they fought and worked for (Alexievich, 2016). People started contemplating alternative ideologies even before the Soviet collapse; liberal democracy seemed very promising for many. However, the first tough years after the collapse of the USSR resulted in frustration and disappointment in liberal democracy across the emerging post-Soviet societies. In most cases, the various conservative ideologies filled the ideological vacuum in post-Soviet countries. Typically, it was a nationalist ideology, whether in a primordial or state-oriented mode, flavored with a varying quantity of traditional religion. The position of women in those societies was explicitly reformulated in all cases. The new official discourses were about bringing women back home from the labor market. However, it did not necessarily mean that women actually followed remonstrances of the politicians and conservative activists. Neither the average number of children has risen nor the divorce rate has fallen dramatically. All the existing demographic trends suggest irrelevance of conservative political interventions in this sphere (Vishnevsky, 2009).

The new realities—neoliberalism in the forms of oligarchic capitalism—also felt like another experiment and reinforced distrust in the government because of the shrinking public services and monopolization of goods and services by local tycoons. The post-Communist governments were “most fervent and committed adopters of neoliberal economic reforms” (Appel and Orenstein, 2018); they continued to enact neoliberal reforms despite political setbacks. In Armenia, similar to many post-Soviet countries, the political and economic power has been in the hands of the ruling elite that the state and private media have been predominantly owned by the oligarchs, the opposition have not had much resources to compete at the elections, many Armenian oligarchs have been members of parliaments and members of the ruling Republican party. Oligarchs used their wealth and resources to ensure the victory of their candidates in elections (e.g., victories of Sargsian and Kocharian) (Stefes, 2008; Aghajanian, 2012). This situation led to lower institutional trust in the long run.

Armenian nation-building and pro-choice attitudes

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Armenia along with other post-Soviet governments tended to promote gender hierarchy and traditional gender roles to reinforce their legitimacy. As some authors note, the role of mother quickly started to be praised as sacred, as Armenian mothers were called upon to revive the nation after centuries of colonization and abuse. During the times of crisis, women were involved in the nationalist movement in the late 1980s and Karabakh war in the 1990s; they fought in the war and assisted the war effort in multiple ways (Shahnazarian, 2016). Beukian shows that in the aftermath of the nationalist movement of 1988 and the war in Karabakh, “the role of women shifted from protestors, soldiers, and martyrs, to home-carers, housewives, and mothers” (Beukian, 2014, p. 248) However, the sacralization of women puts them in a passive role as reproducers of the country, transmitters of culture to the younger generation, guardians of the nation's health (Beukian, 2014, p. 253). Their agency and active participation in democratic movements for independence and in the war have been largely ignored by the national ideology and public discourse (Shahnazarian, 2016).

Gendered national ideology aiming at securing and legitimizing male domination has become a part of national ideology and nation-building across post-Soviet space (except the Baltic countries). This is a part and parcel of breaking away from the Soviet past and asserting the country's continuity with the pre-Soviet period. In addition to emphasizing the idea of soil and blood, these discourses are also strong on women's role as mothers and the nation's means of reproduction. These discourses typically emphasize the control over women's reproductive function and their sexuality through public condemnation of “deviance.” These developments resemble legal prohibitions of divorces, abortions, and premarital sex in other countries, which also involved the patriarchal notions of “manhood” and “womanhood” (Yuval-Davis, 1997).

In the Republic of Armenia since 1991, women's presence in governmental structures has remained low despite the gender quotas and formal legal equality. After the Velvet revolution of 2018 where women took an active part in the protest, the new government of Nikol Pashinyan did not increase the representation of women. The National Assembly of Armenia returned to the quota system in 1999, adopting a law providing for mandatory inclusion of women in the party lists—no less than 5% (in 2007, the quota increased to 15%, and in 2012 to 20%). A very few women run and get elected to regional and local governments, where specific quotas do not exist. Female mayors or governors of regions are non-existent, and there are only a small number of women working as heads of village administration. According the UNDP report, women make up only 9% of the district and local councils. Moreover, the gender stereotypes continue to deny women positions of leadership (Cavoukian and Shahnazaryan, 2019). However, their presence in NGOs and horizontal networks is high.

Despite all the differences that post-Soviet societies may have, the processes of nation-building in those societies have common features as follows: They are relatively conservative, stressing patriarchal and nationalist narratives, and trying to form their new national post-Soviet identity by appealing to primordial discourses and myths of national revival (Gapova, 2007). Even the Perestroika leader, Mikhail Gorbachev claimed that women should be liberated from their double burden and stay at home (Rotkirch et al., 2007).

After the fall of communism, “women's interests were sacrificed to the transformation” in the former Soviet Union and all over post-Communist Europe (Funk and Mueller, 2018). This resulted in transition from the full employment system to returning women to the private sphere of home, control over women's bodies and general hostility toward women's sexuality, realized through restrictions of abortions and the emphasis on women's roles as mothers (Funk and Mueller, 2018). Gender and sexuality are now acknowledged as a major basis for redistribution of resources within each nation, benefiting some groups at the expense of others. Furthermore, the observed drastic reduction of gender equality and rejection of individual-choice values might occur due to the recovery of class hierarchies in these societies. As Gapova argues, “while the essential feature of the third wave of feminism in the West was the alleviation of the class structure, which meant a more even redistribution of resources, post-socialism generated the amplification of the class structure through economic inequality” (Gapova, 2005). According to her analysis, the redistribution of resources went hand in hand with redefinitions of masculinity and femininity and the roles of men and women in the society (Gapova, 2002). A rapid economic decline may lead to unpredictable transformations in gender patterns, either to more egalitarian or more oppressive gender order (Young, 2013).

Religion is instrumental in building the new gender order, and its role in Armenia is huge. Religion is prominent in the public sphere of most post-Soviet states, serving as a “grand narrative representing national values” (Agadjanian, 2006). The Armenian church (one of the earliest Christian churches) plays an important role in everyday life of people and in the persistence of the traditional gender roles in Armenia.

The most specific feature of the Armenian gender order is the attitude toward pre-marital sex and public fetishization of virginity. Attitudes toward sexuality remain discriminatory toward women that a 2016 survey revealed that almost 86% of respondents agreed that women should remain virgin until marriage (Arab and Abrahamyan, 2019). This fact usually has to be proven by the mother-in-law, and remains an issue in the marital choice. Temkina shows that social control of premarital sex constitutes the gender order in Armenia (Temkina, 2010, p. 132).

Talalyan argues that the institute of marriage is the pinnacle of patriarchy in Armenia, which shapes power relations in the domestic sphere, maintaining marginalization and inequality of women in the domestic sphere. Women can face insecurity and economic instability outside marriage, especially in the case of divorce (Talalyan, 2020, p. 2).

“To obey the husband is one of the most important obligations of an Armenian woman, and the Armenian husband has all rights to demand this kind of submission from her. This statement proves not only national written materials, but also religious records” (Talalyan, 2020, p. 9). A cheating husband is tolerated by the society whereas a cheating wife would be harshly criticized as not worthy of being called an Armenian woman (Aharonian, 2010). Strict regulations of young women's behavior and limitations on their freedom has been a custom in Armenian society historically. Purity and humility have been the main sources of pride of the bride's family and deviations from strict rules of girls' upbringing could lead to social stigma.

Despite women's access to education and employment since the nineteenth century (Rowe, 2003), the patriarchal paradigm is remarkably stable in private life. Despite the fact that abortion, divorce, single motherhood, remarriage used to be available options in the twentieth century Armenia, the gender-age hierarchies remain powerful. Men are considered the bread-winners in the family while women's main role is to be a mother–housewife. The parents often choose partners for their children. These tendencies are especially prominent in the rural and urban areas while significant diversity is observed in Yerevan (Talalyan, 2020, p. 43).

The institute of the traditional Armenian family is still strong in Armenian society. Even in the Soviet period, Armenian men and women found it crucially important to keep their marriage in any circumstances as divorce was universally condemned and had harsher consequences for women Talalyan. While it may seem typical for any modernizing society, Armenian scholars claim that marital status played an exceptional role for Armenian women throughout decades, while divorced women were stigmatized. The lack of gender equality, especially in the private sphere, and stigmatization of divorced women resulted in domestic violence. There is no punishment for domestic violence in the Armenian criminal code (Martirosyan, 2019). Violence against women is widely accepted and can be even seen as a norm inside the family, “Armenia is a patriarchal society, in which gender-based stereotypes and patriarchal attitudes are passed on from generation to generation” (Nikoghosyan, 2015, p. 23).

There are sex-selective abortions as well a considerable intolerance in Armenian public and media toward women- and LGBT-rights activists and organizations (Nikoghosyan, 2015). The rate of newborn boys to girls in Armenia is among the most inequal in the world, and it has to do with the lower status of women in general as well as to economic reasons (girls leave parents' house when they get married). In 2013, the adoption of the law on Equal Right and Equal Opportunities for Men and Women by the parliament instigated a public hysteria and actions by ultra-nationalist groups against the law, women- and LGBT-rights activists, and the very word gender (Nikoghosyan, 2015, p. 23) Nikoghosyan views it as a broader attack on women and LGBT rights activists in the region and civil society on post-Soviet space that aim to block any attempts toward European integration. The adoption of the law mobilized an anti-gender movement and resulted in the changes of the title of the law (Hovhannisyan, 2018). The interpretation of the law and its leading concept—gender—has been interpreted by the conservatives as propaganda of homosexuality; the 2013 law was represented by far-right nationalists as a threat to the already endangered nation. Gender, according to far-right nationalists, threatens the existence of Armenian nation because it is seen as attempts to “halt Armenians from reproducing for their future survival as a nation” (Shirinian, 2019, p. 964). Marriage, family, and reproduction of national values are deemed to be the important factors that ensure survival of their nation that the reaction against the law came from almost all segments of the society (Shirinian, 2019). Human rights and equality are often perceived as “Western” values and even “foreign intervention” (Shirinian, 2019). The word gender, as a result, was deleted from all documents.

There have been two waves in the process of gender backlash and re-traditionalization in Armenia; the first was internal (1988–1991) and caused by the economic collapse and political instability. The second one was external, when Armenia became a member of the Eurasian Economic Union in 2013 led by Russia. The construction of the imaginary “illiberal East” in the country has to do not only with the historical and nation-building features but also with the elites' desire to ally with Russia, whose elites also exhibit ostentatious patriarchy and traditionalism. The Kremlin's domestic and international narratives amplify the ideological confrontation with the West; it denounces “Gayrope” (meaning Europe) in an attempt to discredit the European Union as a model and convince the public to support the Eurasian Economic Union. Sperling (2014) argues that the gender norms propagating gender stereotypes, patriarchal culture, and “macho” masculinity are used as a legitimation tool by the Russian government. Moreover, Russia exports this ideology abroad to win conservatives' support in various societies. A very nuanced recent work of Shirinian (2020) argues that imaginary geography where the US is portrayed as an enemy to Armenia influences the perception of the term “gender.” The ideology of “illiberal East” is actively supported by various far-right and nationalist groups in Armenia, politicians, and media. The term gender, as Nona Shahnazarian argues, is a “battleground in efforts for producing new geopolitical divisions” (Shahnazarian, 2017). After Armenia joined the Eurasian Economic Union, anti-gender campaigns became stronger, while women- and LGBT-rights almost disappeared from the public discourse (Shahnazarian, 2017).

Armenian historical traumas and perceived threat to national existence

In Armenia, the conflict with Azerbaijan over Nagorno–Karabakh exacerbates the traumatic memories of the 1915 Armenian genocide. Armenia is the center of a very divided community of over 7 million Armenians living in diaspora (spyurk) and 4–5 million of crypto-Armenians (those who are hiding their ethnic roots in contemporary Turkey) (Cheterian, 2015). Post-Soviet Armenia is surrounded by hostile states and many people in the country feel as if they were in a besieged fortress. For those who left Armenia, it is often imagined as a lost paradise. As Nira Yuval–Davis notes, “[The new communication technologies established] the new role for the ‘homeland' more central and concrete, for diasporic communities, whose links with their country of origin had for many generations a symbolical meaning” (Yuval-Davis, 1997, p. 66). This is very true for Armenians, as national pride and corresponding pro-natalist attitudes can be associated with the national struggle for the territories, and the national identity is built on the basis of tragic common history of genocide and dispersion.

Another trauma of Armenian society has to do with its colonial experience. As Fanon (1952) had argued, liberation from the (effeminizing) colonial burden is often associated with reclaiming the colonized men' masculinity and the associated disempowerment of women. However, the recently achieved freedom from the Soviet colonial project does not exhaust the topic.

When a national project is perceived to be threatened and the construction of the national identity is contested, the attitudes toward sexuality and gender might take extreme and prohibiting forms. The nationalists often rely on discourses of home and family to prop up the national identity in times of crisis (Moghadam, 1994). The rhetoric of national threat of losing the local population worked so well that virtually all the USSR successor states exploited it although to a various extent (Marsh, 1998; Cleuziou and Direnberger, 2016). The elites framed the debates on individual-choice values so that being against those values was natural for a “patriot.” This choice of the post-Soviet elites is perhaps better explained by their economic incapacity to build a new national identity on another basis than by cultural factors (Suny, 2000; Surucu, 2002). Nation-building projects try to “mobilize all available relevant resources for their promotion” (Yuval-Davis, 1997, p. 44). When the economic resources are scarce, and the political ones unstable, the political entrepreneurs resort to culture. Here the issues of fertility, birth control, and family easily become central as women are “required to carry this ‘burden of representation', as they are constructed as the symbolic bearers of the collectivity's identity and honor” (Yuval-Davis, 1997, p. 45). Hence, the symbolic importance of female purity, as only “pure” women can reproduce a “pure” nation to sustain and ensure its survival (Anthias and Yuval-Davis, 1989).

At any rate, people's attitudes are affected by various nationalist and neo-traditionalist ideologies. Yet their behaviors, especially in the private sphere, remain divorced from the official line. The wide-spread condemnation of these practices in survey answers does not necessarily reflect the reality where abortions, divorces, and premarital sex have been normalized since the early Soviet period. Despite the significant decline in abortions and increasing use of contraception since 1991, the former still remains an important part of country's reproductive culture and practice.

While research on value change points to the behavioral relevance of individual-choice values (Welzel, 2013, p. 189), as values usually affect life strategies and priorities, we see an opposite pattern in Armenia. The discrepancy between the individual-choice values and actual behaviors in Armenia may be due to socioeconomic reasons. Many decisions related to sexual and reproductive choices are conditioned by socioeconomic factors to a greater extent than by values. Low levels of fertility during the first two decades after the Soviet collapse might happen to a larger extent due to economic restraints rather than value change. If both partners are jobless, they are more likely to postpone their next child. According to Billingsley (2011), the wealthiest women in Armenia have higher odds of wanting a third child. The choice of divorce vs. keeping the marriage may also be viewed as a decision driven by economic considerations rather than individual choice. Women's status and economic security might be affected as a result of divorce (Talalyan, 2020, p. 60).

A representative study indicated that the Armenian public views men's migration more positively than women's (Agadjanian, 2020). In patriarchal societies like Armenia, women's migration is still a subject of stigmatization. Since Armenia gained independence in 1991, the collapse of its economy and deindustrialization increased the labor migration flow, including the labor migration of women and permanent emigration. The male migration flows continued to grow and decimated communities in rural areas. The stabilization of the economy in the late 1990s did not restore the rural employment rates because the Soviet-era rural industries did not really recover. Due to the economic stagnation in the rural areas, the rural poverty remained widespread, pushing more men to migrate to Russia (Menjívar and Agadjanian, 2007). Female labor migration from Armenia has been relatively low. The patriarchal norms supported the gender imbalance in labor migration. When their partner migrates, women take additional responsibilities in the household but this does not transform women's status and relationships (Agadjanian, 2020). Women have been increasingly becoming breadwinners in the families yet men are still considered the “heads of the household” (Anjargolian, 2005, p. 182). After the Soviet collapse, many educated women, such as engineers or teachers, had to work as street vendors or cleaners. According to Aslanyan, many women surveyed in 2005 agreed that they would prefer to sit at home if the husband could provide for the family (Aslanyan, 2005, p. 200).

The decline in birth rates might be the result of economic conditions rather than changing the individual values. Our research question, however, is not why people do what they do but rather why they say some things publicly while doing very different things privately. This article focuses on the possible mechanisms that make these discrepancies possible.

Hypotheses

Our data allow us to take a glimpse on individual-choice attitudes in Armenia. In more than 30 years of independence, new generations grew up listening to the discourses on women amalgamating patriarchal and nationalist ideologies. How successful have these discourses been? Which social groups are more prone to support these discourses?

We analyze measures of attitudes toward abortions, divorces, and casual sex. These items are not necessarily something that respondents think of on a daily basis. Yet they reflect socially approved opinions formed mostly in the post-Soviet period. The respondents' answers give us an idea of what can and what cannot be said publicly—in other words, of social norms. As Moore and Vanneman wrote, “most people conceal their real attitudes toward any charged issues. For this reason, the overwhelming support of puritanic attitudes in mass surveys may not reflect the actual practice, although it does reflect the social norm” (Moore and Vanneman, 2003).

The majority of people, whose answers we are analyzing below, grew up in the USSR, and they could hardly have radically changed their opinion after the dissolution of the country. However, the new institutional context empowered some, and disempowered others. Social context defines the majority opinion, but there is some degree of heterogeneity and a few agents of change in every society. In more open and less-repressive systems, this heterogeneity is more vivid than in others. In more restrictive situations, some potential agents of change are more likely to leave the country, making these prospective changes less probable.

At any rate, people's attitudes are affected by official post-Soviet discourses, oftentimes essentially nationalist. However, their behavior, especially in the private sphere, remains disassociated from the official line, which continues the tradition of Soviet “open secrets.” Still, we expect those people who are more affected with nationalist ideologies to express more conservative attitudes. Consequently, we state the basic hypothesis of this study as follows: Nationalism is a strong predictor of individual-choice values, operationalized as attitudes toward abortion, divorce, and casual sex.

Additional hypotheses are of twofold. The first has to do with institutional trust as lack thereof along with repression (even in the form of opprobrium) creates an environment conducive to open secrets and unwritten rules. We expect that those with lower levels of confidence in state institutions will be more likely to express the most conservative attitudes. The second is about interest in politics, as we think that those affected by the official discourse will be more supportive of the patriarchal narrative formulated by the state.

In most societies in the world, the support of individual-choice values is well predicted with higher education, younger age, low levels of religiosity, and higher social status with high explanatory power of those predictors. We expect all those factors to have weaker explanatory power in Armenia.

Analysis

Post-Soviet countries significantly deviate from the theoretical prediction of their position on abortion, divorce, and casual sex. These attitudes, labeled “individual choice” in Welzel's emancipative index, are expected to rank much higher than we find in the post-Soviet societies for which we have compatible data (Welzel, 2013).

We use two waves of the European Values Study that include Armenia with fieldwork done in 2008 (EVS, 2020, 4th wave), and 2018 (EVS, 2020, 5th wave) to investigate the factors of pro-choice attitudes.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable in our analysis is an index of individual-choice values that resembles Welzel's index of individual choice (Welzel, 2013). Our index, too, includes questions regarding the justification of divorce and abortion, but we exclude the question on homosexuality because it has little or no variation. The overwhelming majority of the Armenian respondents (95%) say that it can never be justified. Due to the long history of criminal punishment for sex between males (up to 1993) and a history of using homosexual sex as a measure of control in Soviet prisons (and millions of Soviet men have been a part of that system on either side of the bars), homosexuality is still deeply stigmatized in the whole post-Soviet region (Clech, 2018; Gulevich et al., 2018).

To replace the missing item of the index, we add a question on casual (extramarital) sex. The issue of virginity is still very much alive in many patriarchal cultures and it has received some attention in the post-Soviet context in the recent years (Poghosyan, 2011). As Anna Temkina writes in her work on the Armenian case, premarital virginity was the key part of gender order there even in the relatively emancipated Soviet period (even though emancipation might apply more to the public, rather than private, domain) (Temkina, 2010, p. 132). The question on justification of extramarital sex also relates to individual choice in one's private life and correlates with the two other components of the index.

Consequently, our index includes the following variables: Justification of divorce, abortion, and casual sex. All answers are measured on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 means “can never be justified” and 10 means “can always be justified.”

Controls and independent variables

Education is dichotomized so that it has the following two levels: University education (level 1) and other (level 2). Age and gender are taken from the original EVS data set “as is.”

We use two measures of religiosity as follows: Attendance is a seven-level variable (ranging from “Several times a day” to “Never”), treated as a continuous variable. Although we acknowledge the issue of distance inequality between categories, the preliminary analysis shows an almost constant effect across categories, so we decided in favor of the model parsimony. The other one is the response to the question whether the respondent is religious with the following three categories of answers: “A religious person,” “Not a religious person,” and “A convinced atheist.”

Interest in politics is a four-point variable (1: very interested, 4: not at all interested) that we treat as a continuous variable.

We measure nationalism, which is our main explanatory variable as a response to the question, “How proud are you to be a national of your country” with four possible answers: “very proud,” “proud,” “not proud,” and “not at all proud.” We united the two latter categories into one as they are numerically small.

Another block of independent variables includes a battery of questions on confidence in state or international organizations coded as follows: 1: a great deal of confidence, 4: no confidence at all.

Methods

The datasets of the last two waves of the European Values Study demonstrate very high quality, and the problem of missing values is relatively small. Nevertheless, we start with multiple imputation [using the Amelia package in the R environment (Honaker et al., 2011; R Core Team, 2020)] to rely on full datasets and to make sure that missing values do not alter our results. Amelia is a tool (library) for the R environment for statistical programming that runs multiple imputation—it reconstructs missing values based upon variable relationships within the dataset. Then we proceed to latent class analysis, which identifies two groups of respondents. The first tends to answer “Never justifiable” to all the questions on justifiability of abortion, divorce, and casual sex included in our index. The other group (forming just less than half of the sample) is less radical.

Based on this finding, we conduct a two-step regression analysis with binary logistic regression at the first step and gamma regression at the second step (cf. Gelman and Hill, 2006). At the first step, we re-code our dependent variable into two categories: “1” refers to those people who say they could never justify divorce, abortion, and sex before marriage, and “0” stands for those who justify at least some individual choice on at least one dimension. We then use logistic regression to analyze the factors that distinguish these two categories of respondents.

At the second step, we conduct a regression analysis that distinguishes between those individuals who accept individual choice to various degrees, excluding those coded as “1” at the previous step. This analysis helps us identify the factors that influence one's views on family and sexual behavior, provided one does not hold radically conservative beliefs. We employed gamma regression at the second step of our analysis due to the shape of the distribution of our DV. In these models, we estimate the effects of various factors on individual-choice values among those who concede that it is possible to sometimes justify, at least minimally, abortion, divorce or casual sex. We also cross-check our findings using Tobit regression; these results are given in Appendix.

Results

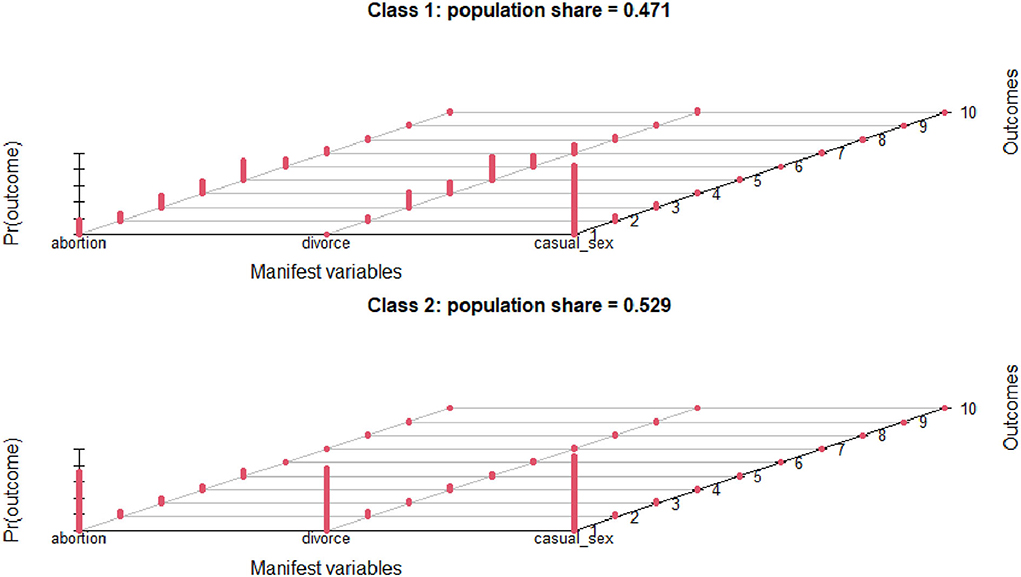

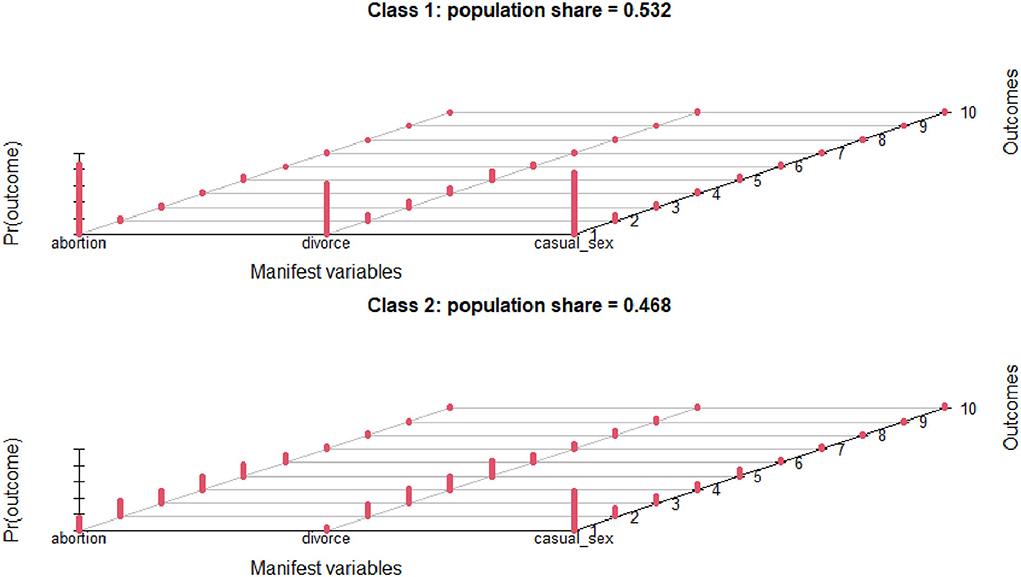

Latent class analysis

One can see two major groups differing in the degree of their radicalism on the issues of interest in Figures 1, 2. The class of “never justifiers” remains stable over time (about 53%). Another class of “sometimes justifiers” shows some dynamics, as the attitude toward casual sex is the strictest of all three variables, but less so in the latter wave.

Binary logistic regressions

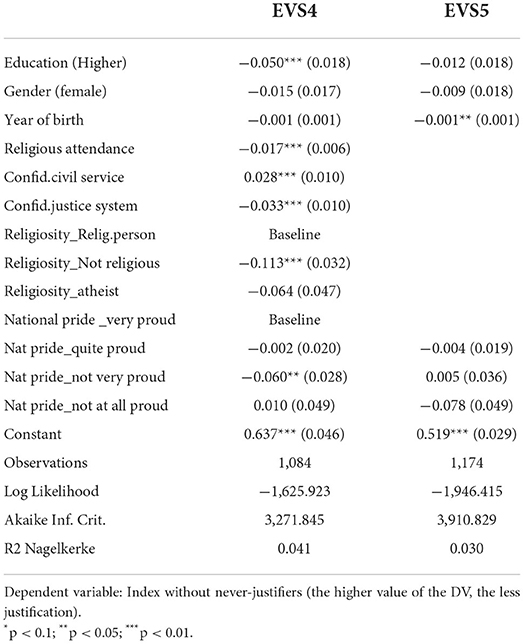

At the first step, we employ logistic regression to estimate the predictors of radically conservative attitudes (those people who answer “never justifiable” on all three questions included into the index) (see Table 1).

Table 1. Binary logistic regressions on most conservative attitudes (1-all three components never justifiable).

Interestingly, the controls that routinely prove to be significant, such as higher education or gender show no effect. Younger age has a fair predictive power in wave 4, but much less so in wave 5. Overall, the model fitted for the earlier data fits our theoretical expectations much better both in terms of significant predictors and their explanatory power.

In EVS (2020), we see strong effects of religiosity and political interest; more religious people and those not interested in politics are more likely to never justify abortions, divorces, and casual sex, the latter finding being contrary to our expectations. Less confidence in the national civil service and healthcare system, but more confidence in the justice system (in wave 4) and education system (in wave 5) is associated with strict moral condemnation.

However, the only predictor that shows high significance in both waves of EVS is national pride; those who are very proud to be Armenians (as opposed to those “quite proud” and “not very proud”) tend to have more condemning attitudes.

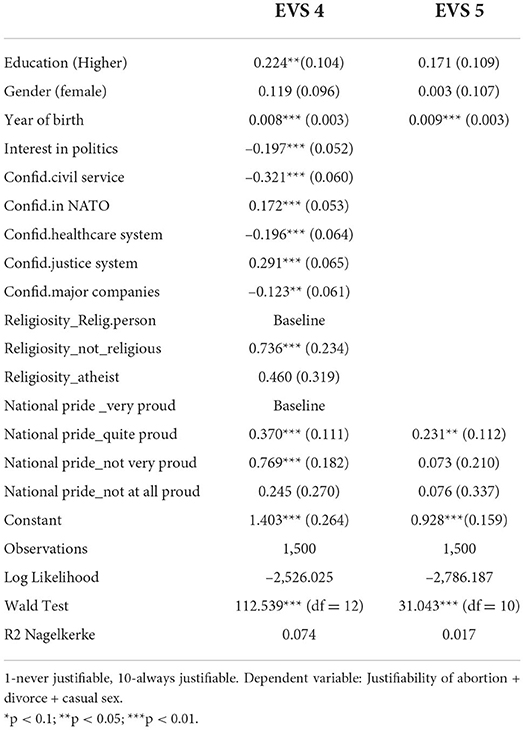

Gamma regressions

At the second step, we see even less explanatory power of conventional predictors in both waves, with the latter model being weaker (see Table 2). The expected effect of higher education is found in EVS 4, but turns insignificant in EVS 5, gender makes no difference in either wave, and the positive effect of older age on absolute non-justification holds in EVS 5, but not in EVS 4. National pride is significant in wave 4, but not in wave 5.

Likewise, more religious people are more likely to condemn abortion, divorce, and casual sex in wave 4, but not in wave 5. Less confidence in the national civil service, but more confidence in the justice system is associated with condemnation in wave 4, but not in wave 5.

Tobit regressions

Tobit regressions (see Table A1 in Appendix) are used for the robustness checks and show very similar results such as no effect of gender, a weak effect of higher education, and a solid effect of age. Religiosity, interest in politics, and confidence in organizations have basically the same effects as in the previous models, while national pride remains the only predictor working well in both waves of surveys, although the effect is weaker in wave 5.

In our research, we use standard methods of regression analysis to drive to a conclusion that in Armenia attitudes toward abortion, divorce, and casual sex are hardly predicted by a standard bunch of factors that correlate with those attitudes in most countries of the world. Knowing that those variables are highly invariant (see Sokolov, 2018), we confirm the hypothesis that something specific, different from the majority of the countries happens in Armenia regarding those issues. We aim at explaining very conservative attitudes by nationalist feelings, confidence, and trust apart from evident controls of age, higher education, and gender. The picture we get from those analyses reminds us that the answers on sensitive questions should not be taken at their face value, but they can still convey much about the society.

Discussion

Armenia is a unique country where pro-choice attitudes are not predicted by the conventional factors of female gender and higher education, and even the age effect is fickle. On the other hand, the national pride is the strongest and most robust predictor. The picture of very low level of justification of abortion and divorce and one of the world's lowest ones as far as casual sex is concerned, this picture looks like a portrait of a society that is going through a period of a massive conservative backlash united by the idea of pro-creation in the face of national security threat. This is the story that respondents seem to be telling. They report their opinions fairly openly, leaving fewer missing values than respondents in more repressive societies. However, can one take this picture at face value?

We know from the literature that condemnation of these practices in survey answers does not necessarily reflect the actual experience in a society where abortion, divorce, and premarital sex have been routine since the early Soviet period. Armenia underwent a quick and relatively successful modernization in the twentieth century as a part of the Soviet Union, which included modernization in the gender order and individual choice. However, after the collapse of the USSR, which was followed by war, economic hardship, neoliberalism, and precarious nation-building, a certain retrogression of attitudes and acceptance of more traditional gender roles occurred. We argue that this retrogression was not as profound as it seems; despite the propagation of conservative norms in the media, people continue to enjoy freedom in these as they did in the Soviet era. Fertility rate, for example, has remained the low for decades (about 1.7) and shows no rising trend, and country-level indicators of gender equality have been actually improving since the mid-2000s.

Does it necessarily mean that respondents just lie? Not really. Plugging in the concept of unwritten rules and open secrets, we express that behavior, especially in the private sphere, remains divorced from the publicly accepted official line. An immense discrepancy between what was said in public and what was practiced in private was a key feature of high socialism. Unwritten rules and open secrets, or a mismatch between the public discourse and private practices, is a post-Soviet habit inherited from the Soviet times, and can be empirically captured by low trust in state institutions. Therefore, individual-choice attitudes in post-Soviet societies may be better interpreted differently than they are in developed democracies.

It is also possible that in the context of an international survey, the issue of national dignity may affect people's responses, especially in those countries that are high on national pride. They may want to present their society in a more favorable light by giving such answers that reflect socially approved norms of their country. We think that most respondents have some notion of the real abortion rate, among the highest in the world in Armenia. However, “national pride,” which is so high in Armenia, may prevent people from acknowledging this in a conversation with a stranger. The observed association of higher national pride and stricter condemnation of pro-choice attitudes (controlling for numerous other predictors) supports this argument.

Deindustrialization, mass unemployment, emigration, political corruption, and low trust in institutions, on the one hand, and the recurring war with Azerbaijan, on the other, has lasting effects on Armenians' understanding of the future of their nation. National values, however, are deeply intertwined with patriarchy.

This preoccupation with national pride definitely stems from the tragic episodes of Armenian history and post-Soviet nation-building based on the idea of a small, dispersed, but unique and proud nation. The strong association of national pride and pro-choice attitudes points to the gendered nature of nation-building which is typical in post-Soviet countries. Since the 1980s, multiple studies have questioned the assumption of nationalism as a gender-neutral project by showing the importance of gender and sexuality for nation-building projects: “Nationalism frequently becomes the language through which sexual control and repression are justified and through which masculine prowess is expressed and strategically exercised” (Mayer, 2012).

This article may also contribute to our understanding of gender backlash in other parts of the world where one observes the rise of conservative politicians and attitudes even as modernization continues (Inglehart and Baker, 2000).

The subtle process of modernization can be seen in our data, as we observe how some effects wane in the later wave of the survey, while younger age becomes a stronger predictor of less conservative attitudes, eclipsing national pride. This may signal that those generations that grew up in relatively stable recent conditions do not respond to the feeling of national threat with traditional attitudes as their elders do. This would open the door to a change both in practice and narrative, raising the level of emancipation to that expected in such an urbanized and educated population as the Armenian.

Conclusion

In some countries, certain historical and cultural settings may lead to the situation when pro-choice attitudes are not predicted by the usual factors, such as education, gender or age. In the case of Armenia presented here, the attitudes appear extremely conservative and are associated with national pride. However, these results should not be interpreted immediately as a sign of a massive gender backlash or retrogression. The value modernization may proceed quietly and privately under the guise of traditional norms. The people in such societies may have various reasons to report normative attitudes on sensitive issues. These may include sheer fear in repressive environments, the legacy of “open secrets” in post-Soviet contexts, or national pride motivating people to present their country right and proper. Thus, learning more about each context is crucial to avoid a simplified or wrong conclusion.

Further research may find out whether the observed link between national pride and lifestyle intolerance is present in other countries, including the Western ones, or this is a specifically post-Soviet phenomenon, or something typical for developing countries that recently have experienced life-threatening and life-altering situations such as war, economic perturbations, and political crises. Likewise, further research may elucidate to what extent the open secrets, or public declaration of neo-traditionalist attitudes divorced from people's real behavior, extend to other contexts.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

VK performed the statistical analysis. SL and VK wrote the manuscript. EP revised it. All authors conceived and designed the study, manuscript revisions, read, and approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be held accountable for the content.

Funding

EP's contribution was supported by the Basic Research Program of the NRU Higher School of Economics.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agadjanian, A. (2006). The search for privacy and the return of a grand narrative: religion in a post-communist society. Soc. Compass 53, 169–184. doi: 10.1177/0037768606064318

Agadjanian, V. (2020). Double gendered: public views on women's and men's migration in Armenia. J. Ethnic Migrat. Stud. 1–24. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1805304

Aghajanian, L. (2012). Breaking the Grip of the Oligarchs. Foreign Policy 5. Available online at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2012/11/05/breaking-the-grip-of-the-oligarchs/ (accessed June 13, 2022).

Aharonian, L. (2010). Nationalism and Sex. The Armenian Weekly 7. Available online at: https://armenianweekly.com/2010/03/07/aharonian-nationalism-and-sex/ (accessed April 28, 2022).

Anjargolian, S. (2005). “Armenia's women in transition,” in The State of Law in the South Caucasus (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 181–195.

Appel, H., and Orenstein, M. A. (2018). From Triumph To Crisis: Neoliberal Economic Reform in Postcommunist Countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Arab, C., and Abrahamyan, M. (2019). Armenia. Country Gender Equality Brief. UN Women 2019. Available online at: https://eca.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/05/armenia-country-gender-equality-brief (accessed April 28, 2022).

Ashwin, S. (2000). “Introduction: gender, state, and society in soviet and post-Soviet Russia,” in Gender, State, and Society in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia, ed S. Ashwin (London: Routledge), 1–29.

Aslanyan, S. (2005). “Women's social identity from an Armenian perspective: Armenian woman, Soviet woman, Post-Soviet woman,” ‘in EMΦY∧OI METAΣHMATIΣMOI GENDERING TRANSFORMATIONS (Rethimno: University of Crete), 192–202.

Beukian, S. (2014). Motherhood as armenianness: expressions of femininity in the making of armenian national identity. Stud. Ethnicity Nationalism 14, 247–269. doi: 10.1111/sena.12092

Billingsley, S. (2011). Second and third births in Armenia and Moldova: an economic perspective of recent behaviour and current preferences. Eur. J. Populat. 27, 125–155. doi: 10.1007/s10680-011-9229-y

Bureychak, T., and Petrenko, O. (2015). Heroic Masculinity in Post-Soviet Ukraine: Cossacks, UPA and “Svoboda”. East/West J. Ukrainian Stud. 2, 3–28. doi: 10.21226/T2988X

Cavoukian, K., and Shahnazaryan, N. (2019). “Armenia: persistent gender stereotypes,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Women's Political Rights, eds S. Franceschet, M. L. Krook, and N. Tan (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 729–743.

Cheterian, V. (2015). Open Wounds: Armenians, Turks and a Century of Genocide. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clech, A. (2018). Between the labor camp and the clinic: tema or the shared forms of late soviet homosexual subjectivities. Slavic Rev. 77, 6–29. doi: 10.1017/slr.2018.8

Cleuziou, J., and Direnberger, L. (2016). Gender and nation in post-Soviet central Asia: from national narratives to women's practices. Natl. Pap. 44, 195–206. doi: 10.1080/00905992.2015.1082997

Darbinyan, K., Arakelyan, M., Hovhannisyan, T., and Aslizadyan, N. (2019). Marriage and Divorce: a Look at Love Life in Armenia. Available online at: https://ampop.am/en/married-and-divorced-why-are-desires-changed/ (Accessed April 11, 2022).

Dudwick, N. (1997). “Out of the kitchen into the crossfire: women in independent Armenia,” in Post-Soviet Women: from the Baltic to Central Asia, ed M. Buckley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 235–249.

EVS (2020). European Values Study Longitudinal Data File 1981-2008 (EVS 1981-2008). GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA4804 Data file Version 3.1.0.

Fanon, F. (1952). The fact of blackness. Postcolonial Stud. Anthol. 15, 2–40. doi: 10.1002/9781119118589.ch1

Fitzpatrick, S. (2000). Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times. Soviet Russia in the 1930s. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Funk, N., and Mueller, M., (Eds.). (2018). Gender Politics and Post-Communism: Reflections from Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. London: Routledge.

Gal, S. (1994). Gender in the post-socialist transition: the abortion debate in hungary. East Eur. Polit. Societies 8, 256–286. doi: 10.1177/0888325494008002003

Gapova, E. (2002). On nation, gender, and class formation in belarus.. and elsewhere in the Post-Soviet world. Nationalities Papers Belarus. 30, 639–662. doi: 10.1080/00905992.2002.10540511

Gapova, E. (2007). Gender i Postsovetskie Natsii: Lichnoe kak Politicheskoe. Ab Imperio 1, 309–328. doi: 10.1353/imp.2007.0040

Gelman, A., and Hill, J. (2006). Data Analysis Using Regression And Multi-level/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gulevich, O., Osin, E., Isaenko, N., and Brainis, L. (2018). Scrutinizing homophobia: a model of perception of homosexuals in Russia. J. Homosex 65, 1838–1866. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1391017

Honaker, J., King, G., and Blackwell, M. (2011). “Amelia II: a program for missing data.” J. Stat. Softw. 45, 1–47. doi: 10.18637/jss.v045.i07

Hovhannisyan, S. (2018). Gender as Danger: Discourses Around the Notion of Gender in 'Iravunk' Newspaper in Armenia (master's thesis). Central European University. Available online at: https://www.etd.ceu.edu/2018/hovhannisyan_siran.pdf (accessed April 28, 2022).

Inglehart, R., and Baker, W. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. Am. Sociol. Rev. 65, 19–51. doi: 10.2307/2657288

Inglehart, R., and Norris, P. (2003). Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Ishkanian, A. (2005). “Gendered transitions: the impact of the post-Soviet transition on women in Central Asia and the Caucasus”, in Central Eurasia in Global Politics, eds M. Amineh and H. Houweling (Leiden: Brill), 161–182.

Johnson, J., and Saarinen, A. (2013). Twenty-first-century Feminisms under Repression: gender regime change and the women's crisis center movement in Russia. Signs 38, 543–567. doi: 10.1086/668515

Johnston, R. (2021). Historical Abortions Statistics, Armenia. Johnston‘s Archive. Available online at; https://www.johnstonsarchive.net/policy/abortion/ab-armenia.html (Accessed April 19, 2022).

Kandiyoti, D. (2007). The politics of gender and the soviet paradox: neither colonised, nor modern? Centr. Asian Surv. 26, 601–623. doi: 10.1080/02634930802018521

Kollontai, A. (1977). Theses On Communist Morality In The Sphere Of Marital Relations. New York, NY: WW Norton New York.

Ledeneva, A. (2011). Open secrets and knowing smiles. East Eur. Polit. Societies 25, 720–736. doi: 10.1177/0888325410388558

Mahon, R., and Williams, F. (2007). Gender and state in post-communist societies: introduction. Soc. Polit. 14, 281–283. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxm017

Marsh, R. (1998). “Women in contemporary Russia and the former Soviet Union,” in Women, Ethnicity and Nationalism: The Politics of Transition, eds R. Wilford and R. Miller (London: Routledge), 75–103.

Martirosyan, S. (2019). Sexual Discourse: Speaking About the Unspeakable. Available online at: https://evnreport.com/raw-unfiltered/sexual-discourse-speaking-about-the-unspeakable-2/ (Accessed April 28, 2022).

Mayer, T., (Ed.). (2012). Gender Ironies of Nationalism: Sexing the Nation. New York, NY: Routledge.

Menjívar, C., and Agadjanian, V. (2007). Men's migration and women's lives: views from rural Armenia and Guatemala. Soc. Sci. Q. 88, 1243–1262. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2007.00501.x

Moghadam, V. (Ed.). (1994). Gender and National Identity: Women and Politics in Muslim Societies. (Karachi: Oxford University Press).

Moore, L., and Vanneman, R. (2003). Context matters: Effects of the proportion of fundamentalists on gender attitudes. Soc Force. 82, 115–139. Available online at: http://www.vanneman.umd.edu/papers/moorev03.pdf

Nikoghosyan, A. (2015). “Tools for change: collective actions of women's rights activists in Armenia,” in Anti-Gender Movements on the Rise? Strategising for G, Vol. 38, ed Heinrich Böll Foundation (Berlin: Heinrich Böll Stiftung. Publication Series on Democracy), 23–27.

Paternotte, D., and Kuhar, R. (2018). Disentangling and locating the “global right”: anti-gender campaigns in Europe. Politics Govern. 6, 6–19. doi: 10.17645/pag.v6i3.1557

Poghosyan, A. (2011). Red apple tradition: contemporary interpretations and observance. Acta Ethnogr. Hungarica 56, 377–384 doi: 10.1556/AEthn.56.2011.2.7

R Core Team (2020). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/.

Riabov, O., and Riabova, T. (2014). The remasculinization of russia? gender, nationalism, and the legitimation of power under vladimir putin. Problems Postcommun. 61, 23–35. doi: 10.2753/PPC1075-8216610202

Rossier, C. (2007). Abortion: an open secret? Abortion and social network involvement in Burkina Faso. Reproduct. Health Matters 15, 230–238. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(07)30313-3

Rotkirch, A., Temkina, A., and Zdravomyslova, E. (2007). Who helps the degraded housewife? Comments on vladimir Putin's demographic speech. Eur. J. Womens Stud. 14, 349–357. doi: 10.1177/1350506807081884

Rowe, V. (2003). A History of Armenian Women's Writing, 1880-1922. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press.

Shahnazarian, N. (2016). “A good soldier and a good mother: new conditions and new roles in the nagorno-karabakh war,” in The Journal of Power Institutions in Post-Soviet Societies.

Shahnazarian, N. (2017). Eurasian Family versus European Values: The Geopolitical Roots of “Anti-Genderism” in Armenia. PONARS Eurasia. Available online at: https://www.ponarseurasia.org/eurasian-family-versus-european-values-the-geopolitical-roots-of-anti-genderism-in-armenia/ (Accessed June 19, 2022).

Shirinian, T. (2019). “Gender hysteria: the other effect of public policy in Armenia,” in Sexuality, Human Rights, and Public Policy, edited by Chima Korieh (Lanham, MD: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press), 115–130.

Shirinian, T. (2020). The illiberal east: the gender and sexuality of the imagined geography of Eurasia in Armenia. Gender Place Cult. 28, 955–974. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2020.1762545

Smyth, L. (1998). Narratives of Irishness and the Problem of Abortion: the X case 1992. Fem. Rev. 60, 61–83. doi: 10.1080/014177898339398

Sokolov, B. (2018). The index of emancipative values: Measurement model misspecifications. Am. Polit Sci. Rev. 112, 395–408. doi: 10.1017/S0003055417000624

Sperling, V. (2014). Sex, Politics, and Putin: Political Legitimacy in Russia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Stefes, C. H. (2008). Governance, the state, and systemic corruption: Armenia and Georgia in comparison. Caucasian Review of International Affairs 2, 73–83.

Suny, R. (2000). Provisional Stabilities: the politics of identities in post-Soviet Eurasia. Int. Secur. 24, 139–178. doi: 10.1162/016228899560266

Surucu, C. (2002). Modernity, nationalism, resistance: identity politics in post-Soviet kazakhstan. Central Asian Survey 21, 385–402. doi: 10.1080/0263493032000053208

Talalyan, L. (2020). The Institution of Marriage in Armenia from Gender Perspective (Dissertation). Univerzita Karlova, Fakulta Humanitních Studií, Praha: Charles University.

Temkina, A. (2010). Dobrachnaya devstvennost': Kul'turnyy Kod Gendernogo Poryadka v Sovremennoy Armenii (na primere Yerevana). Laboratorium. Zhurnal Sotsial'nykh Issledovaniy 2, 129–159.

Westoff, C. (2005). “Recent trends in abortion and contraception in 12 countries,” in DHS Analytical Studies No. 8 (Calverton, MD: ORC Macro).

Young, K. (2013). “Modes of appropriation and the sexual division of labour: a case study from Oaxaca, Mexico,” in Feminism and Materialism (RLE Feminist Theory): Women and Modes of Production, eds A. Kuhn and A. Wolpe (Boston: Routledge), 124–155.

Yurchak, A. (2013). Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Genera- tion. Princeton, NJ: University Press.

Yuval-Davis, N. (1997a). Women, citizenship, and difference. Fem. Rev. 57, 4–27. doi: 10.1080/014177897339632

Zdravomyslova, E. (2001). “Hypocritical sexuality of the late soviet period: sexual knowledge and sexual ignorance,” in Education And Civic Culture In Post-Communist Countries, eds S. Webber and I. Liikanen (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 151–167.

Ziemer, U. (2020). “Women against authoritarianism: agency and political protest in Armenia,” in Women's Everyday Lives in War and Peace in the South Caucasus Palgrave, ed U. Ziemer (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 71–100.

Appendix

Keywords: nation-building, pro-choice values, European Values Study, neo-traditionalism, post-Soviet countries, open secrets

Citation: Lopatina S, Kostenko V and Ponarin E (2022) Pro-life vs. pro-choice in a resurgent nation: The case of post-Soviet Armenia. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:932492. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.932492

Received: 29 April 2022; Accepted: 08 July 2022;

Published: 11 August 2022.

Edited by:

Amy Alexander, University of Gothenburg, SwedenReviewed by:

Tamar Shirinian, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, United StatesNona Shahnazarian, IAE NAS Armenia, Armenia

Copyright © 2022 Lopatina, Kostenko and Ponarin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sofia Lopatina, c29meWEubG9wYXRpbmFAZ21haWwuY29t

Sofia Lopatina

Sofia Lopatina Veronica Kostenko

Veronica Kostenko Eduard Ponarin3

Eduard Ponarin3