95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 23 August 2022

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.929991

This article is part of the Research Topic Contemporary Threats, Surveillance, and the Balancing of Security and Liberty View all 5 articles

Authoritarianism is widely conceived as destructive phenomenon that threatens liberal societies. However, some scholars suggest that authoritarianism is beneficial both for individuals' sense of control and goal attainment within groups. In line with this reasoning, collective problems, such as the COVID-19 crisis and climate change, may go hand in hand with increased levels of authoritarianism. While individuals may generally reject the abstract ideas of authoritarian rule and intolerance, societal threat may require individuals to weigh liberal values against needs for collective unity and action. Thus, individuals are expected to show less support for abstract authoritarian ideas compared to authoritarian ideas that are directed at dealing with a specific societal crisis (crisis-related authoritarianism). Following the notion that authoritarianism serves as an antiliberal means for achieving collective goals, relative increases in crisis-related authoritarianism hinge on the rejection of the means being outweighed by the perceived importance of the goal. While authoritarian disposition captures general tendencies to accept the means, trust in science serves as a proxy for the perceived importance of COVID-19 and climate change mitigation. The relative increase in crisis-related authoritarianism should be particularly pronounced among individuals who are not predisposed to authoritarianism and who trust in science. Findings from a cross-national survey experiment in Germany (N = 1,480) and Spain (N = 1,511) support this reasoning. Participants answered four items covering authoritarian submission and aggression either on an abstract level (control condition), or applied to the COVID-19 crisis or the climate change crisis. Participants were more supportive of authoritarian ideas targeted at a specific collective problem as compared to abstract authoritarian ideas. Furthermore, the differences in authoritarianism between the control condition and the two societal crisis conditions decreased with authoritarian disposition and increased with trust in science. Exploratory analyses suggest that the main differences across experimental conditions are driven by authoritarian submission while the interaction effects are rather driven by authoritarian aggression. The study underlines the role of authoritarian ideas for collective goal attainment that exists above and beyond stable personal dispositions. As such, it sheds light on the conditions under which citizens conceive authoritarianism as justifiable.

Authoritarianism is widely conceived as destructive phenomenon that threatens liberal societies (see for example, Bonikowski, 2017). However, some scholars suggest that authoritarianism is beneficial both for individuals' sense of control and agency (Mirisola et al., 2014) and goal attainment within groups (Kessler and Cohrs, 2008). In line with this reasoning, collective problems requiring unified efforts and cooperation may call for increased levels of authoritarianism. Despite generally supporting liberal values of individual freedom, tolerance and democratic rule and rejecting the abstract idea of authoritarianism, individuals may appreciate the instrumental value of authoritarianism for dealing with societal threat. The present study examines the conditions under which individuals consider authoritarianism justifiable and desirable. More specifically, I aim to investigate whether applications of authoritarianism to contexts of existential, societal threat increase authoritarian responses.

I conducted the study in two democratic countries, Spain and Germany. While both countries value liberal principles, they differ in terms of their affectedness by the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change (Ritchie et al., 2020; Mathiesen et al., 2021). Dealing with these existential, societal threats requires high levels unified efforts and cooperation. Accordingly, I expect individuals to show more support for authoritarianism targeted at fighting climate change or the spread of COVID-19 compared to support for general authoritarian ideas. Following the notion that authoritarianism serves as an antiliberal means for achieving collective goals, discrepancies between support for general authoritarian ideas and crisis-related authoritarianism hinge on the rejection of the means being outweighed by the perceived importance of the goal. Thus, particularly those individuals who are not predisposed to authoritarianism and who trust in science are expected to show increased authoritarian responses when they targeted at dealing with societal threat.

The study contributes to the ongoing discussion on the conceptualization of authoritarianism. I move further away from the idea that authoritarianism is a stable trait deeply rooted in socialization and personality (Altemeyer, 1996; Sibley and Duckitt, 2008; Dallago and Roccato, 2010). Instead, I show that authoritarian attitudes and preferences are highly context-dependent. In threatening contexts that urge for collective, coordinated action, authoritarianism is widespread and extends to people that generally reject authoritarian ideas. This crisis-induced shift may pose a challenge to liberal democracies and social cohesion.

The psychological concept of authoritarianism traces back to Adorno et al. (1950)'s work on the authoritarian personality and has since been subject to vigorous discussions and major advancements. Contemporary work mostly builds on Altemeyer (1996) definition and conceives authoritarianism as a tendency for (a) obedience to leaders (authoritarian submission), (b) intolerance of deviance (authoritarian aggression) and (c) conformity to group norms (conventionalism). Overall, authoritarianism may be understood as a tendency to strive for collective security at the expense of individual autonomy (Duckitt and Bizumic, 2013). In his original work, Altemeyer (1996) focuses on right-wing authoritarianism inflaming the debate whether authoritarian attitudes are indicative of the political right. Proponents of the rigidity-of-the-right hypothesis argue that authoritarianism is more pronounced among individuals with a conservative, right-wing political orientation compared to individuals with a progressive, left-wing political orientation. While extensive meta-analyses support this notion (Jost et al., 2003, 2017), it has not been unquestioned. Much critique revolves around the domain-specificity of authoritarianism and other indicators of rigid thinking. Critics argue that the measures are not content-free, but entangled with political ideology up to the extent that they essentially capture social conservatism (Feldman, 2003; Federico and Malka, 2018; Mallinas et al., 2020). With respect to Altemeyer's conceptualization of authoritarianism, this problem pertains particularly to the subdimension of conventionalism while authoritarian aggression and authoritarian submission are less conflated with conservative issue positions (Feldman, 2003; Hiel et al., 2006; Duckitt et al., 2010; Mallinas et al., 2020). For example, items measuring conventionalism tap upon negative views on homosexuality and women's rights (Altemeyer, 1996).

Research dealing with the entanglement of political ideology and authoritarianism broadly follows two approaches. One strategy aims at capturing the non-conflated “heart” of authoritarianism i.e., tendencies to value social conformity over individual autonomy. In practical terms, this approach focuses amongst others on child-rearing values and the relative weights individuals put on social conformity and individual autonomy, respectively (Feldman, 2003). Another strategy is to acknowledge the context-dependency of authoritarianism. Some efforts focused on combining authoritarianism not only with conservative ideas, but to adapt it to progressive, liberal ideas, thus, measuring whether authoritarianism is present among supporters of left-wing ideology (Hiel et al., 2006; Conway et al., 2018). Following a similar approach but moving beyond political ideology, Stellmacher and Petzel (2005) conceptualize authoritarianism as a group phenomenon. In their view, any social group may become authoritarian in defending threatened ingroup values and norms and the measurement of authoritarianism needs to be adapted to the particular group and its respective values and norms. Key to this understanding of authoritarianism is the role of collective threat: Individuals urge for social conformity when they perceive threats to the values and goals of their group.

The two approaches are reconciled in work that conceptualizes authoritarianism as being both dispositional and reactive (Feldman and Stenner, 1997; Stenner, 2005). General tendencies to value social conformity over individual freedom may reflect an authoritarian disposition that is deeply rooted in personality and socialization (Feldman, 2003). These dispositions may in turn be activated by normative threats to social cohesion instigating authoritarian responses, such as racial or political intolerance (Stenner, 2005). This reasoning suggests that having an authoritarian disposition is a prerequisite or at least facilitator for authoritarian reactions. An alternative account is that individuals generally recognize an instrumental value in authoritarianism for dealing with societal threat, pressing for social conformity independently of their authoritarian dispositions. In fact, authoritarianism may have an adaptationist, prosocial function of facilitating collective, goal-directed action and cooperation in large groups (Kessler and Cohrs, 2008; Sinn and Hayes, 2018). In line with this reasoning, research suggests that individuals are well-aware of the instrumental value of authoritarianism: Lack of personal control was found to mediate the relation between societal threat and authoritarianism (Mirisola et al., 2014; Manzi et al., 2015; Kakkar and Sivanathan, 2017). Thus, individuals may strive for control over threatening situations by enforcing social rules that facilitate collective action. In line with this notion, large shifts in authoritarianism were found in response to various types of societal threats (for an overview, see Schnelle et al., 2021), including terrorism and crime (Roccato et al., 2013; Manzi et al., 2015; Vasilopoulos et al., 2018) as well as economic crisis (Doty et al., 1991; Jugert and Duckitt, 2009; Kakkar and Sivanathan, 2017), but also climate change (Fritsche et al., 2012; Barth et al., 2018; Uhl et al., 2018) and the COVID-19 crisis (Amat et al., 2020; Filsinger and Freitag, 2022).

The notion of authoritarianism as an effective means for dealing with societal crisis points to a gap between (a) general tendencies to value collective security over individual autonomy (authoritarian disposition) and (b) authoritarianism applied to contexts of societal threat (crisis-related authoritarianism). While individuals may generally support individual freedoms, they may consider authoritarianism as a justifiable means for solving collective problems. In fact, individuals are required to balance liberal principles of individual freedom, tolerance and democratic rule with the need for collective action against societal threats (for similar theorizing in the domain of political tolerance, see for example Verkuyten and Yogeeswaran, 2017). Previous studies do not adequately capture these conflicting values and goals as they focus on the impact of societal threat on general support for authoritarianism, rather than on crisis-related authoritarianism targeted at managing a specific collective problem. Research on political tolerance shows that support for abstract, liberal principles, such as freedom of speech and religious liberty, is much higher compared to the support of the applications of these principles to specific contexts that require trade-offs between contradicting values (Sullivan and Hendriks, 2009). For example, tolerance judgements of Muslim minority practices in the Netherlands result from balancing the abstract principle of religious freedom with the value of social cohesion (Adelman et al., 2021). Applying this logic to authoritarianism, concerns for achieving collective goals may outweigh commitments to liberal principles resulting in a relative increase of crisis-related authoritarianism vis à vis general tendencies to value collective security over individual autonomy. In other words, applications of authoritarianism to contexts of existential, societal threat, are expected to increase authoritarian responses (Hypothesis 1).

Genuine examples of societal threats are climate change and the COVID-19 crisis. While threat from COVID-19 crisis is more tangible and immediate than threat from (future) climate change, both COVID-19 and climate change are global problems and pose existential threats to individuals and collectives (Fuentes et al., 2020). Both threats have the potential for causing profound societal disruption and are very salient in public discourse. In many European countries, the public considers climate change and the spread of infectious diseases as the greatest threats to their country (Poushter and Huang, 2020). Furthermore, broad scientific consensus revolves around the causes of the threats and their elimination poses a collective good problem: Individuals are required to change their behavior for the benefit of the collective (Fuentes et al., 2020). These characteristics provide an ideal ground for moralization and pressures for social conformity.

The potentially heightened support for crisis-related authoritarianism raises the question whether individuals generally alter their authoritarian responses in light of societal crisis. Put differently, under what conditions is authoritarianism considered a necessary and justifiable means for dealing with societal crisis? The outcome of this balancing process may depend on (a) individuals' general tendencies to reject authoritarianism (evaluation of the means) and (b) individuals' acknowledgment of the collective problem (evaluation of the goal). While authoritarian dispositions reflect individuals' general tendencies to endorse or object to authoritarian ideas, trust in science captures the extent to which individuals embrace scientific views and acknowledge climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic as collective problems. Thus, the extent to which individuals alter their authoritarian response in light of societal crisis may depend on both individuals' authoritarian dispositions and trust in science.

In line with the notion of authoritarianism as a dormant trait rooted in personality and socialization that awaits activation (Feldman and Stenner, 1997; Stenner, 2005; Dallago and Roccato, 2010), individual dispositions may influence the extent to which individuals alter their authoritarian response in light of societal crisis. In fact, some studies found that societal crises instigate authoritarianism particularly among individuals with an authoritarian disposition. Those who chronically score high on authoritarianism, tended to become even more authoritarian in threatening contexts (Feldman and Stenner, 1997; Cohrs et al., 2005). A prominent explanation for interindividual differences in authoritarian reactions to threat contends that an authoritarian disposition comes along with a heightened motivation to overcome the unpleasant state of anxiety and uncertainty (Jost et al., 2003). Another explanation states that individuals with authoritarian predisposition are simply more vigilant and sensitive to threat cues than non-authoritarians (e.g., Perry and Sibley, 2013). The vicious circle of authoritarianism instigating threat perceptions which in turn instigates authoritarianism may be at work particularly for normative threats that are ambiguous in terms of their harmfulness, such as disrespect for leaders, socially deviant groups and minor crimes (Stenner, 2005; Butler, 2013; Russo et al., 2020). In contrast, authoritarian predispositions may play a different role for existential, unequivocal threats that are harmful both at the personal and collective level.

In fact, some scholars argue for the opposite effect and find that threat increases authoritarianism particularly among non-authoritarians (Hetherington and Suhay, 2011; Mirisola et al., 2014; Vasilopoulos et al., 2018). The studies show that authoritarians and non-authoritarians become more alike in their expressions of authoritarianism in contexts of threat. Drawing on the literature of political tolerance (Peffley et al., 2001; Verkuyten and Yogeeswaran, 2017), one possible interpretation is that non-authoritarians engage in a weighting process whereby authoritarianism as a means for preventing collective harm is balanced with principles for individual freedom and democratic rule. To non-authoritarians, authoritarianism may appear as the necessary and appropriate response to existential societal threats and they may alter their attitudes accordingly, while authoritarians do not alter their attitudes in response to threat since they highly support authoritarianism independently of the specific societal context. In other words, non-authoritarians should change their attitudes in accordance with the requirements of the specific situation (societal threat vs. no threat). Thus, the relative increases in crisis-related authoritarianism are expected to be larger among individuals without authoritarian disposition compared to individuals with authoritarian disposition (Hypothesis 2).

Adopting a social identity perspective, Stellmacher and Petzel (2005) argue that authoritarianism is a group phenomenon whereby individuals defend threatened ingroup norms and goals. Again, threat plays a crucial role in predicting authoritarianism. However, unlike more traditional approaches to authoritarianism (e.g., Altemeyer, 1996; Duckitt et al., 2002), they adapt the measurement of authoritarianism to specific social identities, such as national identity and student identity, and ask to what extent the respective group's norms and leaders should be followed and defended. Irrespective of the specific social identity and its group norms, individuals are assumed to become authoritarian if group norms and values are threatened and if they identify with the respective group. In line with this reasoning, Stollberg et al. (2017) found that individuals tend to defend ingroup norms and values more rigorously under threat, even when ingroup norms are liberal. Under threat, individuals seem to defend any norm as long as long as they acknowledge it as their ingroup's norm. Thus, accounting for the extent to which individuals embrace ingroup norms and goals is crucial for predicting authoritarian responses.

On a societal level, tendencies for embracing group norms and goals may be captured by trust in political institutions, a concept closely related to national identity (see for example, Miller and Ali, 2014). Research showed that national identification relates positively to trust in political institutions (Gustavsson and Stendahl, 2020), which in turn increases support of group norms in the form of tax compliance and law abidance (Marien and Hooghe, 2011; Gangl et al., 2016). Political trust also relates positively to support for taxes on fossil fuels, particularly among people who feel threatened by climate change (Fairbrother et al., 2019). Research in the context of COVID-19 found that compliance with preventive measures is predicted by trust in science and to a lesser extent by trust in government (Pagliaro et al., 2021). Furthermore, higher reductions in individuals' mobility were observed in regions with high trust in politicians as compared to regions with low trust in politicians (Bargain and Aminjonov, 2020). As institutional trust plays a crucial role for the endorsement of behaviors preventing the spread of COVID-19, it may even result in lower mortality rates (see for example, Oksanen et al., 2020). Thus, institutional trust may reflect tendencies for acknowledging societal leaders and norms which may in turn trigger authoritarian responses.

While institutional trust may generally enhance authoritarianism, trust in science may only affect crisis-related authoritarianism. Both COVID-19 and climate change can be conceived as global, natural disasters that require scientifically grounded action. Accordingly, academia is an important authority influencing opinions and norms on issues of climate change and COVID-19, up to the level that people make generic appeals to “follow the science” (Leonhardt, 2022). Trust in science may affect the extent to which individuals embrace (or reject) dominant views on COVID-19 and climate change and become authoritarian in the pursuit of the collective goals proposed by scientific authorities. Accordingly, relative increases in crisis-related authoritarianism are expected to be larger among individuals with high trust in science compared to individuals with low trust in science (Hypothesis 3).

While societies face many different types of collective problems and threats, I focus on the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change for investigating the extent to which individuals alter their authoritarian responses in accordance with the societal context. At the time of data collection (December 2020), vaccines against COVID-19 were not yet available to the general public meaning that compliance with non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as wearing face masks and social distancing, was key to slowing down the spread of COVID-19 (Perra, 2021). Therefore, personal well-being was largely dependent on the behaviors of others. Similar interdependencies exist for the climate crisis, albeit less immediate since personal experiences of climate-change-related hardships, such as floods, heat waves and droughts, are not yet widespread and more difficult to attribute to specific human activity (Fuentes et al., 2020). Furthermore, both threats hit countries across the world, but to various degrees, calling for cross-national comparisons. The psychological mechanism of striving for collective goals through authoritarianism should be universal. However, the determination and radicalism with which collective goals are pursued might amongst others depend on country-specific threat levels.

The present study examines authoritarian responses in Spain and Germany, two countries that rank high in terms of respect for political rights and civil liberties (Freedom House, 2021). Despite having a relatively recent history of authoritarian rule (Francoist Spain, Nazi Germany, socialist regime in the former GDR), liberal principles, such as freedom of opinion, checks and balances and rule of law, are firmly established in Spain and Germany's political systems (Engler et al., 2020) and this is also mirrored in citizens' support for democratic rule (Haerpfer et al., 2022)1. However, the counties differ with respect to threat exposure. During the field period of the survey in December 2020, Spain had about twice as many cumulative confirmed COVID-19 cases per 100.000 residents than Germany (4,000 vs. 2,000). This disparity is even lager when looking at cumulative numbers of COVID-19 related deaths per 100.000 residents: 106 for Spain vs. 34 for Germany (Ritchie et al., 2020). With three-quarters of Spain facing desertification by the end of the century, the country is also expected to be hit much harder from climate change than Germany (Mathiesen et al., 2021).

The data was collected as part of a large, representative online survey in December 2020 and January 2021 in Germany. In Germany, respondi invited 8,150 of its panel members to participate in the survey (response rate 22%). In Spain, Netquest invited 4,780 of its panel members (response rate 41%). The survey covered different topics, including personal opinions on COVID-19 measures, personality characteristics and political attitudes (Gerschewski et al., 2021). Median response time was 16.25 min in Germany and 17.55 min in Spain. To improve data quality, respondents, who did not correctly answer a test item, were excluded (217 in Germany and 414 in Spain). I further excluded 91 German respondents and 50 Spanish respondents who had missing values on one or more of the variables included in the analyses (see below), yielding final sample sizes of 1,480 and 1,511, respectively. Quota sampling was applied to assure that the sample resembles the general population in terms of age (M = 48.98, SD = 16.33), gender (49.75 percent female) and education (32.89 percent low, 26.75 percent middle, 40.35 percent high)2. At the expense of statistical power, generalizability may further be enhanced with post-stratification weights (Miratrix et al., 2018). For this purpose, sampling weights were computed based on officially documented distributions of age, gender and education. However, considering the limited advantages of sampling weights in survey experiments (Miratrix et al., 2018), they are not included in the main analyses, but only in an additional robustness check.

A survey experiment was conducted to investigate whether individuals alter their authoritarian responses in accordance with societal context. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions which either measured baseline levels of authoritarianism or authoritarianism applied to COVID-19 or climate change (crisis-related authoritarianism). Participants answered four items on authoritarian submission and authoritarian aggression with introductory sentences and the wording of the items varying across experimental conditions. The subdimension conventionalism was left aside because it is less central to the concept of authoritarianism (Feldman, 2003) and shows higher overlap with conservatism (Mallinas et al., 2020). The items for baseline levels of authoritarianism (control condition) were inspired by an improved measurement of authoritarian aggression and authoritarian submission that reduced the conflation of conservatism and authoritarianism (Beierlein et al., 2014). The items of the COVID-19 condition and the climate change condition also referred to obedience to leaders and intolerance of deviance, but applied the ideas to the context of societal crisis:

[In our current times / In times of the Coronavirus/ in times of climate change], there are different opinions on how our society should be organized. Please indicate to what extent you agree with the following statements:

• We should be grateful for leaders who tell us exactly what we can do and how [in our times/in times of the Coronavirus/ in times of global warming].

• In our times/in times of the Coronavirus/in times of climate change, restraint and obedience are important.

• Those who do not follow social rules/Those who do not follow the rules for fighting the Coronavirus/Polluters should be severely punished.

• Troublemakers and dissenters/Those spreading conspiracy theories and Coronavirus deniers/Those spreading conspiracy theories and climate change deniers should be made aware that they are unwanted in society.

Participants indicated their agreement with the statements on a seven-point scale with higher values reflecting higher authoritarian responses. The reliability of the scale was good in Germany (Cronbach's α = 0.81) and acceptable in Spain (Cronbach's α = 0.69). The experiment was included in the first half of the survey, before respondents administered other items that are of interest in this study.

Individuals' evaluation of the means is reflected in authoritarian disposition that was measured with the KSA-3 scale (Beierlein et al., 2014). Compared to the original RWA scale developed by Altemeyer (1996), the KSA-3 scale is an improved measurement of authoritarianism and is, thus, fairly established in the German context. While following Altemeyer's suggestion for three subdimensions of authoritarianism, Beierlein and colleagues attempt to overcome the shortcomings of its predecessor i.e., the overlap with political conservatism3. The scale was included at the end of the survey and consisted of nine items (Cronbach's α = 0.85 in Germany; Cronbach's α = 0.79 in Spain). Answers were given on a seven-point scale with higher numbers indicating more agreement. Example items are “We should be grateful for leaders telling us exactly what to do” and “Traditions should definitely be carried on and kept alive“4. Compared to the measure for baseline authoritarianism, the scale measuring authoritarian disposition is more extensive as it also covered conventionalism with three items and it included an additional item for both authoritarian submission and authoritarian aggression. Nonetheless, there is a significant conceptual overlap between baseline authoritarianism and authoritarian disposition. This overlap allows to investigate whether authoritarians and non-authoritarians differ in the extent to which they alter their authoritarian responses in accordance with societal context. A strong relation between authoritarian disposition and baseline authoritarianism indicates reliability across measurement times while a weak relation between authoritarian disposition and crisis-related authoritarianism may point to an unequal influence of societal context on authoritarian responses. Thus, the purpose of the analyses is not to confirm a rather trivial relation between authoritarian disposition and baseline authoritarianism but rather to investigate the differences in the relation between authoritarian disposition and authoritarian response across experimental conditions.

Individuals' evaluations of the collective goal are captured with two items measuring participants' trust in universities and trust in scientists (r = 0.73 in Germany; r = 0.54 in Spain). Answers were given on a seven-point scale with higher values indicating more trust.

Trust in national institutions i.e., government, parliament, courts and media (Cronbachs α =0.90 in Germany; Cronbach's α =0.85 in Spain), as well as perceived COVID-19 health risk were included as control variables. For the latter, participants indicated on a seven-point scale how much they worry about they themselves or close others becoming severely sick with COVID-19.

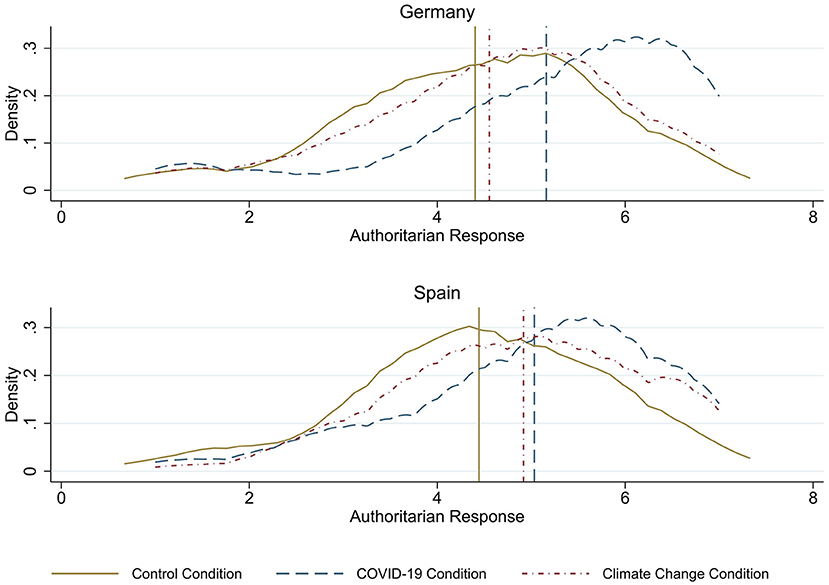

For Germany, a one-way ANOVA revealed group differences in average authoritarian responses across the three conditions [F(2,1,480) = 39.21, p < 0.001]. A test for the a priori hypothesis was conducted using Bonferroni corrected alpha levels. Lending partial support to the first hypothesis, results indicated an increase in COVID-19 related authoritarianism (M = 5.179; SD = 1.545; p < 0.001), but not climate change related authoritarianism (M = 4.571; SD = 1.415; p = 0.216) relative to baseline levels of authoritarianism (M = 4.415; SD = 1.365). Similar results were obtained for Spain. A one-way ANOVA revealed group differences in average authoritarian responses across conditions [F(2,1,511) = 24.53, p < 0.001]. A test for the a priori hypothesis was conducted using Bonferroni corrected alpha levels. In line with the first hypothesis, baseline levels of authoritarianism (M = 4.460; SD = 1.324) were lower compared to both COVID-19 related authoritarianism (M =5.029; SD = 1.376; p < 0.001) and climate change related authoritarianism (M = 4.891; SD = 1.306; p < 0.001). Distributions of authoritarian responses and mean values are also displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Kernel density estimations of authoritarian responses across countries and conditions. Vertical lines indicate mean values for each condition.

To investigate the interplay of societal crisis, authoritarian disposition and trust in science, I conducted linear regressions, again separating between Germany and Spain (see Table 1). In the reduced models (Model 1 and 4), I only included main effects of societal crisis treatments, authoritarian disposition and trust in science. In a second step, interaction effects between societal crisis treatments and authoritarian disposition as well as societal crisis treatments and trust in science were included (Model 2 and 5). In order to facilitate the interpretation of the interaction effects, the variables authoritarian disposition and trust in science were centered at the sample mean5 (Hayes, 2013). In a third step, I included the control variables trust in national institutions, perceived COVID-19 health risk, age and education6.

Including authoritarian disposition and trust in science as covariates altered the effect of the climate change condition in Germany (see model 1): Compared to the one-way ANOVA, the difference in authoritarian responses between the baseline condition and the climate change condition was larger and the difference was also statistically significant. For the other treatment effects, accounting for authoritarian disposition and trust in science resulted only in minor changes compared to the one-way ANOVA. Adding both trust in science and authoritarian disposition to the model did not yield in multicollinearity as indicated by small Variance Inflation Factors (VIF; for all variables in both countries < 1.5).

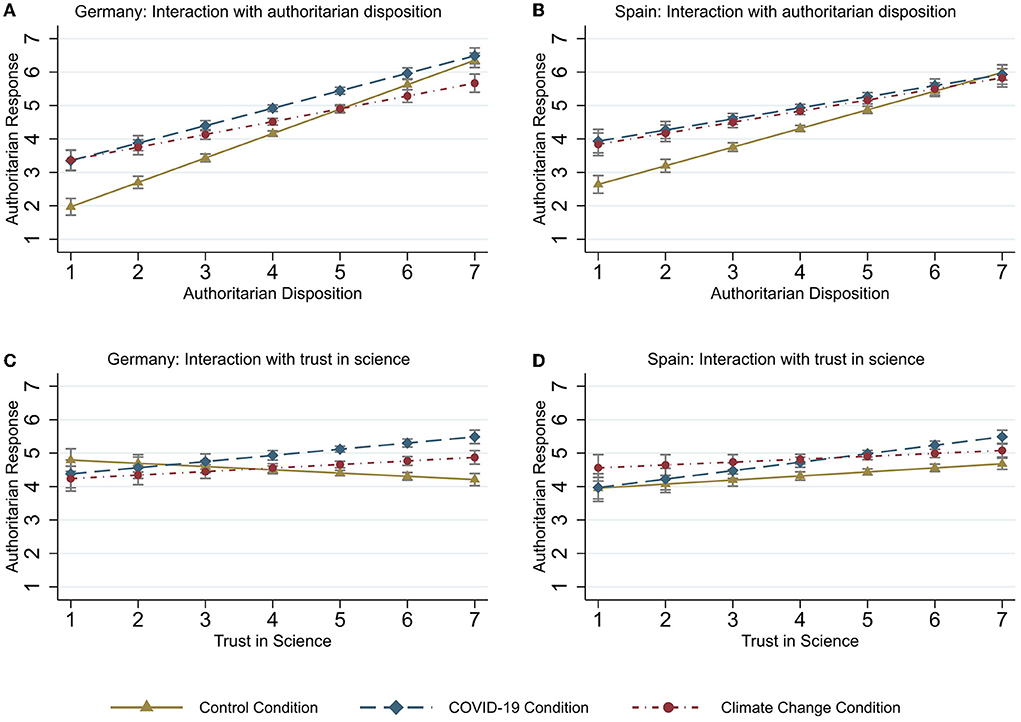

Results from model 2 and 4 indicate that the positive effects of the societal crisis treatments on authoritarian responses decreased with authoritarian disposition and the negative interaction effects persisted even when control variables were included (see model 3 and 5). To facilitate the interpretation, interaction effects of societal crisis treatments and authoritarian disposition are visualized in the upper panels of Figure 2. Both in Germany and in Spain, the COVID-19 condition increased authoritarian responses relative to the control condition among participants low in authoritarian dispositions, but not among participants with high authoritarian dispositions. Similarly, the climate change condition increased authoritarian responses relative to the control condition among participants low in authoritarian dispositions, but this was not the case for participants high in authoritarian dispositions. Among Spanish participants with high authoritarian dispositions, there was no difference between participants in the climate change condition and the control condition (see Figure 2B). In Germany, there was even an opposite effect: Among participants with high authoritarian dispositions, the climate change condition decreased authoritarian responses relative to the control condition (see Figure 2A). Overall, the findings support the second hypothesis.

Figure 2. Authoritarian responses across conditions and countries for different levels of authoritarian disposition [(A) Germany, (B) Spain] and trust in science [(C) Germany, (D) Spain]. Figures are based on results from regression models 3 and 5 in Table 1. Vertical bars denote 95% confidence intervals.

A different pattern was observed for the interplay of societal crisis treatment and trust in science (see lower panels in Figure 2): While applying authoritarianism to COVID-19 had no effect on authoritarian responses for participants who don't trust in science, participants who trust highly in science expressed elevated levels of authoritarianism in the COVID-19 condition relative to the control condition. The interplay of the COVID-19 condition and trust in science was very similar in Germany (Figure 2C) and Spain (Figure 2D). However, the extent to which the effect of the climate change condition depended on trust in science differed across countries. In Germany, the effect on the climate change condition depended on trust in science: Compared to the control condition, applying authoritarianism to climate change did not elevate authoritarian responses among German participants who trust little in science. In contrast, the climate change condition increased authoritarian responses among German participants with high trust in science (see Figure 2C). In Spain, the effect of the climate change condition did not depend on trust in science (see model 5). Compared to the control condition, the climate change condition increased authoritarian dispositions irrespective of participants trust in science. Except for this nonexistent moderation effect, the findings are in line with the third hypothesis7.

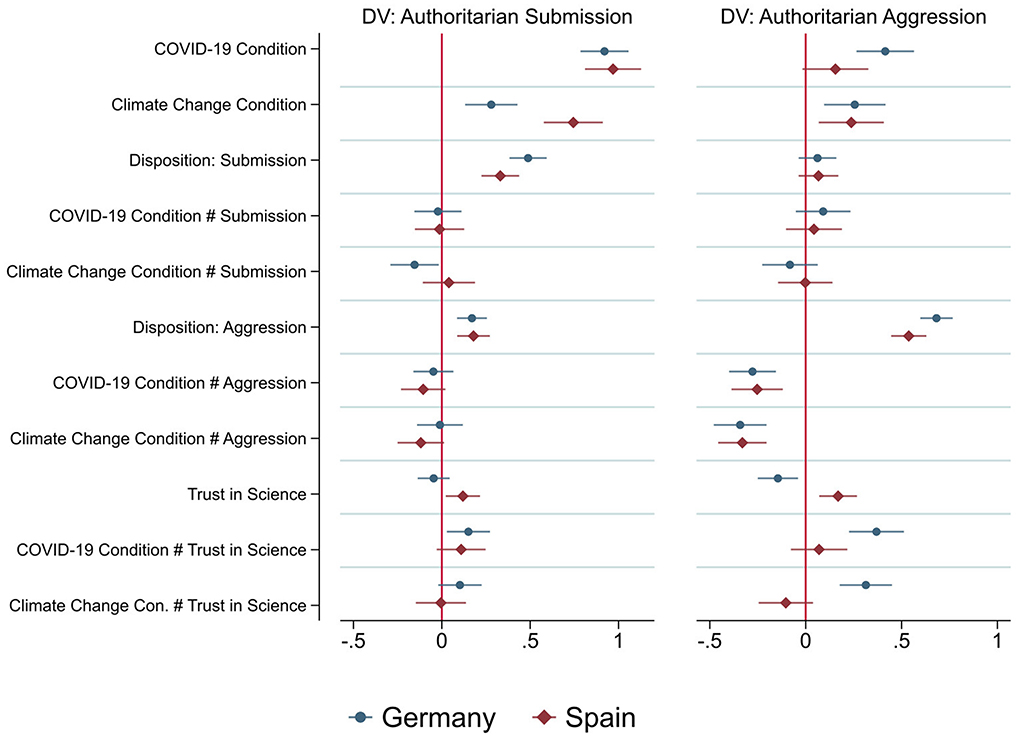

Based on the empirical evidence for the multidimensionality of authoritarianism (Funke, 2005; Duckitt et al., 2010; Mallinas et al., 2020), I further explored differences between the subdimensions of authoritarian submission and authoritarian aggression. Regression analyses separately explaining the subdimensions of authoritarian submission and authoritarian aggression revealed a more nuanced picture (see Figure 3). Relative to the control condition, societal crisis treatments seemed to increase authoritarian aggression to a lesser extent than authoritarian submission. In fact, increases in authoritarian aggression (relative to the control condition) were qualified by individuals' evaluations i.e., disposition for authoritarian aggression (Germany and Spain) and trust in science (in Germany only). While the treatment effects on authoritarian aggression decreased with disposition for authoritarian aggression, they increased with trust in science. In contrast, increases in authoritarian submission were independent of individuals' disposition for authoritarian submission (except for the effect of the Climate Change condition in Germany) and trust in science (except for the effect of the COVID-19 condition in Germany).

Figure 3. Coefficient plot showing the effect of experimental condition (Reference Category: Control condition), authoritarian disposition and trust in science on authoritarian submission and authoritarian aggression, respectively. Estimates are based on linear regression analyses with all control variables included (conventionalism, trust in national institutions, perceived COVID-19 health risk, age and education) and robust standard errors; see Table S7 in the online supplement for the full results. Horizontal bars denote 95% confidence intervals.

An extensive amount of research suggests that support for authoritarianism rises in response to societal threats (for a review, see Schnelle et al., 2021). Adopting a prosocial perspective on this phenomenon (Kessler and Cohrs, 2008; Sinn and Hayes, 2018), I argue that individuals may conceive authoritarianism as a justifiable means for facilitating unified action against societal threats. While individuals may reject the abstract ideas of authoritarian rule and intolerance, they may readily endorse authoritarian ideas when targeted at dealing with societal threat. In line with this reasoning, the present research aimed at grasping the influence of societal context for authoritarian responses. More specifically, general tendencies to value collective security over individual autonomy were compared with levels of crisis-related authoritarianism i.e., authoritarianism applied to the contexts of COVID-19 and climate change, respectively.

Findings from a survey experiment conducted in Germany and Spain indicate that individuals alter their authoritarian responses in accordance with the societal context. Average support for crisis-related authoritarianism was higher than general tendencies to value collective security over individual autonomy. Furthermore, the effect of applying authoritarianism to concrete situations of societal threats varied across individuals: Societal threat increased authoritarian responses among individuals without authoritarian dispositions, but not among individuals with authoritarian disposition. In Germany, findings also indicate that trust in science matters for the extent to which individuals alter their support for authoritarianism in light of societal threat. The relative increases in crisis-related authoritarianism become lager with rising levels of trust in science. In Spain, trust in science also increased the effect of the COVID-19 condition on authoritarianism (albeit to a lesser extent than in Germany), while the effect of the climate change condition did not depend on trust in science. I further explored differences across subdimensions of authoritarianism revealing that contexts of societal crisis increased authoritarian submission (mostly independently of trust in science and authoritarian disposition), while their effects on authoritarian aggression varied largely with levels of trust in science and authoritarian disposition. This finding is in line with research showing that COVID-19 related threat increases authoritarian submission, but not authoritarian aggression (Filsinger and Freitag, 2022).

Findings are remarkably similar for Germany and Spain, except for the interplay between societal crisis and trust in science. In Spain, relative increases in crisis-related authoritarianism seems to depend less on trust in science than in Germany. A possible explanation is that Spain is more affected by COVID-19 and climate change. Conceivably as a result of personal experience, Spanish respondents are generally highly aware of the societal threat from COVID-19 and climate change (Poushter and Huang, 2020) and may recognize the urgency for collective action irrespective of their individual trust in science. In contrast, for German respondents, perceptions of threat from COVID-19 and climate change may be more ambiguous and, thus, depend on individuals' levels of trust in science. An interesting avenue for future research may be to investigate how (sub)national levels of societal threat exposure manifest in authoritarianism. For example, are individuals from regions with high numbers of COVID-19-related deaths more authoritarian than individuals from regions with fewer deaths?

Relatedly, political orientation also plays into threat perceptions and subsequent authoritarian responses. Unlike it is the case for many cultural threats, such as immigration, in Western countries people leaning toward the political left tend to be more concerned about climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic than people leaning toward the political right (Poushter and Huang, 2020; Delvin et al., 2021). Moreover, trust in science is negatively correlated with orientations toward the political right, at least in the US context (Azevedo and Jost, 2021). The finding that trust in science increases the effect of societal crises on authoritarianism may be due to its overlap with political ideology. Political orientation may also be a confounder for the moderating role of authoritarian disposition. Unfortunately, the current survey data did not include any measures of political orientation. However, the notion of political ideology “as an interrelated set of attitudes, values, and beliefs” (Jost et al., 2009, p. 315) suggests that there is value in studying the role of different (ideological) beliefs thereby going beyond the unidimensional concept of left-right orientation. The finding that the interaction effects with authoritarian disposition and with trust in science persist while controlling for the other speak to the idea that they do not capture the same thing i.e., political orientation. Furthermore, the COVID-19 protests have shown that, in Germany, scientific skepticism is not a unique feature of the political right (Grande et al., 2021). Nonetheless, future research should explicitly tackle the conglomerate of political ideology, type of societal crisis (cultural or natural threat) and authoritarian response.

More studies are also needed to investigate the presumed balancing process. Following the reasoning of Asbrock and Fritsche (2013), responses to collective threats may be deliberate and direct rather than subconscious and indirect as it is the case with personal threats, such as mortality salience. Accordingly, the present research assumes that individuals deliberately weigh liberal principles of tolerance and democratic rule against the need for unified action against societal threats. An interesting paradigm might be to enhance individuals' perceptions of cohesiveness and collective control to investigate whether increased perceptions of group agency bolster the effect of threat on authoritarianism. Alternatively, future research may try to frame societal crisis in terms of individual rather than collective problems. While this may be difficult for the climate change crisis, for the COVID-19 crisis emphasis may be laid on individual risk factors and preventive behaviors vs. collective responsibilities and costs. Finally, it may also be interesting to investigate authoritarianism in the context of other, less politicized challenges, such as data protection on the internet and fair working conditions.

Next to the inability to shed light on the presumed balancing process, the present study also has some methodological limitations. First, authoritarian responses were measured with four items only, capturing authoritarian aggression and submission, while discarding the third dimension, conventionalism. This dimension was not included because it has the highest overlap with conservative ideology (Duckitt et al., 2010), at least when measured in the original, abstract form (Altemeyer, 1996). However, in line with the idea of group authoritarianism (Stellmacher and Petzel, 2005), conventionalism may also be conceptualized as conformity with group norms rather than conformity with conservative ideals. Previous studies suggest that societal threat increases conformity with group norms, even when they are liberal (Stollberg et al., 2017). Another limitation is the measure of authoritarian disposition. The survey was conducted during the second COVID-19 wave and respondents administered the scale after answering many questions on the pandemic and its personal and collective consequences. Since authoritarianism has been shown to increase when individuals are reminded of personal or societal threats (Fritsche et al., 2012; Asbrock and Fritsche, 2013), the measure of authoritarian disposition may be inflated. This caveat could have been avoided if authoritarian disposition was measured at a different timepoint, either before or after the main survey. Finally, measures for authoritarian reactions and authoritarian disposition were developed for the German context and their validity may be lower in the Spanish context.

Despite these limitations, the present study entails an important conclusion: During heavy societal storms, individuals are willing to throw principles of individual freedom, tolerance and democratic rule overboard. Interestingly, this change in authoritarian responses pertains particularly to individuals who generally value individual freedoms implying that authoritarians and non-authoritarians become more alike in their responses. The study therefore challenges the account that societal threat activates authoritarian dispositions resulting in an increased gap in intolerance between authoritarians and non-authoritarians (Feldman and Stenner, 1997; Stenner, 2005). While the present study cannot disentangle ideology and authoritarianism, the focus on rather liberal issues ties in with previous studies showing that the phenomenon of authoritarianism extends beyond the political right (Hiel et al., 2006; Conway et al., 2018). Efforts should, thus, be targeted at reconciling liberal values and (perceptions of) collective control. First, awareness for the potential trade-off should be increased among the general public so that individuals may deliberate on their viewpoint. Second, the enforcement of conformity and obedience should be democratically legitimized and within clearly set boundaries, such as the proscription of vigilantism and its limitation the purpose of dealing with existential collective crises. Within these boundaries, authoritarian reactions may unfold their prosocial potential in facilitating collective goal-directed action.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The publication of this article was funded by the Open Access Fund of the Leibniz Association.

I thank Alexander Dicks, Immo Fritsche, Herbert Renz-Polster, Benjamin Schürmann, Marcus Spittler, and Susanne Veit for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.929991/full#supplementary-material

1. ^As indicated by the world values survey (Haerpfer et al., 2022), support for democracy is high among German and Spanish citizens. On a scale from 1 (very good) to 4 (very bad), both German and Spanish citizens consider being ruled by a strong leader on average as fairly bad (Germany: M = 3.28, SD = 0.20; Spain: M = 3.15, SD = 0.03). On a scale from 1 (not at all important) to 10 (absolutely important), they consider living in a democracy on average as very important (Germany: M = 9.31, SD = 0.03; Spain: M = 8.82, SD = 0.05).

2. ^Separate sample statistics for Germany and Spain are displayed in Table S2 in the online supplement.

3. ^The KSA-3 scale also offers advantages compared to child-rearing values, another widespread measure for authoritarianism. First, child-rearing values are highly dependent on cultural contexts, arguably more so than general tendencies to value collective security over individual autonomy as measured by the KSA-3. For example, in collectivist cultures child-rearing values of obedience and cooperation tend to be perceived as more important than in individualistic cultures (Trommsdorff and Kornadt, 2003). In light of the cross-national setting of the present study, using child-rearing values as indicator for authoritarian disposition would thwart comparisons between Germany, a rather individualistic country, and Spain, a rather collectivistic country. Second, the KSA-3 scale allows to capture the three subdimensions of authoritarianism i.e., authoritarian submission, authoritarian aggression, and conventionalism (Altemeyer, 1996). In contrast, the dimensionality of child-rearing is rather unclear and does not map onto the established subdimensions proposed by Altemeyer.

4. ^A complete list of items used in this study is presented in Table S1 in the online supplement.

5. ^Mean centering refers to subtracting the sample mean of a variable from individuals' scores implying that the new variable's mean is zero.

6. ^One-way ANOVAs suggest that the average levels of the independent and control variables did not differ substantially across experimental groups (see Table S5 in the online supplement). Only for Germany and when looking at the subdimensions of authoritarian disposition, pairwise comparisons revealed a marginally significant difference in the average levels of disposition for authoritarian submission between the COVID-19 condition (M = 4.29; SD = 1.41) and the climate change condition (M = 4.08; SD = 1.59; p = 0.061), while comparisons with the control condition (M = 4.12; SD = 1.41) were not significant (p >.16). For Germany, pairwise comparisons also revealed that trust in science is higher in the COVID-19 group (M = 5.00; SD = 1.33;) compared to the climate change group (M = 4.77; SD = 1.44; p = 0.024), but comparisons with the control condition (M = 4.94; SD = 1.34;) were again insignificant (p >.14). Since I do not statistically compare authoritarian responses between the COVID-19 and climate change conditions, but use the control condition as reference category, the interpretation of the main analyses should not be thwarted by these (marginal) group differences.

7. ^To enhance the generalizability of the findings, the same analyses were conducted using post-stratification weights (see Table S6 in the online supplement). Results did not differ substantially from the findings of the main analyses presented in Table 1. Importantly, the results imply the same conclusions with regard to the three hypotheses.

Adelman, L., Verkuyten, M., and Yogeeswaran, K. (2021). Moralization and moral trade-offs explain (in)tolerance of Muslim minority behaviours. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 51, 924–935. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2792

Adorno, T., Frenkel-Brenswik, E., Levinson, D. J., and Sanford, R. N. (1950). The Authoritarian Personality. New York, NY: Harper.

Amat, F., Arenas, A., Falcó-Gimeno, A., and Muñoz, J. (2020). Pandemics meet democracy. Experimental evidence from the COVID-19 crisis in Spain. Available online at: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/dkusw/ (accessed April 14, 2022).

Asbrock, F., and Fritsche, I. (2013). Authoritarian reactions to terrorist threat: who is being threatened, the Me or the We? Int. J. Psychol. 48, 35–49. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.695075

Azevedo, F., and Jost, J. T. (2021). The ideological basis of antiscientific attitudes: effects of authoritarianism, conservatism, religiosity, social dominance, and system justification. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 24, 518–549. doi: 10.1177/1368430221990104

Bargain, O., and Aminjonov, U. (2020). Trust and compliance to public health policies in times of COVID-19. J. Public Econ. 192, 104316. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104316

Barth, M., Masson, T., Fritsche, I., and Ziemer, C.-T. (2018). Closing ranks: ingroup norm conformity as a subtle response to threatening climate change. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 497–512. doi: 10.1177/1368430217733119

Beierlein, C., Asbrock, F., Kauff, M., and Schmidt, P. (2014). Die Kurzskala Autoritarismus (KSA-3): Ein Ökonomisches Messinstrument Zur Erfassung Dreier Subdimensionen Autoritärer Einstellungen. GESIS-Working Papers.

Bonikowski, B. (2017). Ethno-nationalist populism and the mobilization of collective resentment. Br. J. Sociol. 68, 181–213. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12325

Butler, J. C. (2013). Authoritarianism and fear responses to pictures: the role of social differences. Int. J. Psychol. 48, 18–24. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.698392

Cohrs, J. C., Kielmann, S., Maes, J., and Moschner, B. (2005). Effects of right-wing authoritarianism and threat from terrorism on restriction of civil liberties. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 5, 263–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-2415.2005.00071.x

Conway, I. I. I. L. G., Houck, S. C., Gornick, L. J., and Repke, M. A. (2018). Finding the loch ness monster: left-wing authoritarianism in the United States. Polit. Psychol. 39, 1049–1067. doi: 10.1111/pops.12470

Dallago, F., and Roccato, M. (2010). Right-wing authoritarianism, big five and perceived threat to safety. Eur. J. Personal. 24, 106–122. doi: 10.1002/per.745

Delvin, K., Fagan, M., and Connaughton, A. (2021). People in Advanced Economies Say Their Society Is More Divided Than Before Pandemic. Pew Research Center.

Doty, R. M., Peterson, B. E., and Winter, D. G. (1991). Threat and authoritarianism in the United States, 1978–1987. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 61, 629. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.629

Duckitt, J., and Bizumic, B. (2013). Multidimensionality of right-wing authoritarian attitudes: authoritarianism-conservatism-traditionalism. Polit. Psychol. 34, 841–862. doi: 10.1111/pops.12022

Duckitt, J., Bizumic, B., Krauss, S. W., and Heled, E. (2010). A tripartite approach to right-wing authoritarianism: the authoritarianism-conservatism-traditionalism model: authoritarianism-conservatism-traditionalism. Polit. Psychol. 31, 685–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00781.x

Duckitt, J., Wagner, C., du Plessis, I., and Birum, I. (2002). The psychological bases of ideology and prejudice: Testing a dual process model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83, 75–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.1.75

Engler, S., Leemann, L., Abou-Chadi, T., Giebler, H., Bousbah, K., Bochsler, D., et al. (2020). Democracy Barometer. Codebook. Version 7. Aarau: Zentrum der Demokratie.

Fairbrother, M., Johansson Sevä, I., and Kulin, J. (2019). Political trust and the relationship between climate change beliefs and support for fossil fuel taxes: evidence from a survey of 23 European countries. Glob. Environ. Change 59, 102003. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.102003

Federico, C. M., and Malka, A. (2018). The contingent, contextual nature of the relationship between needs for security and certainty and political preferences: evidence and implications. Polit. Psychol. 39, 3–48. doi: 10.1111/pops.12477

Feldman, S. (2003). Enforcing social conformity: a theory of authoritarianism. Polit. Psychol. 24, 41–74. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00316

Feldman, S., and Stenner, K. (1997). Perceived threat and authoritarianism. Polit. Psychol. 18, 741–770. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00077

Filsinger, M., and Freitag, M. (2022). Pandemic threat and authoritarian attitudes in Europe: an empirical analysis of the exposure to COVID-19. Eur. Union Polit. 23, 417–436. doi: 10.1177/14651165221082517

Freedom House (2021). Countries and Territories. Available online at: https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores (accessed January 31, 2022).

Fritsche, I., Cohrs, J. C., Kessler, T., and Bauer, J. (2012). Global warming is breeding social conflict: the subtle impact of climate change threat on authoritarian tendencies. J. Environ. Psychol. 32, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2011.10.002

Fuentes, R., Galeotti, M., Lanza, A., and Manzano, B. (2020). COVID-19 and climate change: a tale of two global problems. Sustainability 12, 8560. doi: 10.3390/su12208560

Funke, F. (2005). The dimensionality of right-wing authoritarianism: lessons from the dilemma between theory and measurement. Polit. Psychol. 26, 195–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00415.x

Gangl, K., Torgler, B., and Kirchler, E. (2016). Patriotism's impact on cooperation with the state: an experimental study on tax compliance. Polit. Psychol. 37, 867–881. doi: 10.1111/pops.12294

Gerschewski, J., Giebler, H., Heisig, J. P., Li, J., and Rauh, C. (2021). Citizens' Assessment of Pandemic Crises and Government Responses: A Cross-National Survey [Dataset]. WZB Berlin Social Science Center.

Grande, E., Hutter, S., Hunger, S., and Kanol, E. (2021). Alles Covidioten? Politische Potenziale des Corona-Protests in Deutschland. WZB Discuss. Pap. Available online at: https://bibliothek.wzb.eu/pdf/2021/zz21-601.pdf (accessed July 20, 2021).

Gustavsson, G., and Stendahl, L. (2020). National identity, a blessing or a curse? The divergent links from national attachment, pride, and chauvinism to social and political trust. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 12, 449–468. doi: 10.1017/S1755773920000211

Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J. M., (eds.). (2022). World Values Survey: Round Seven – Country Pooled Datafile Version 4.0. Madrid; Vienna: JD Systems Institute and WVSA Secretariat. doi: 10.14281/18241.18

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Hetherington, M., and Suhay, E. (2011). Authoritarianism, threat, and Americans' support for the war on terror. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 55, 546–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00514.x

Hiel, A. V., Duriez, B., and Kossowska, M. (2006). The presence of left-wing authoritarianism in Western Europe and its relationship with conservative ideology. Polit. Psychol. 27, 769–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00532.x

Jost, J. T., Federico, C. M., and Napier, J. L. (2009). Political ideology: its structure, functions, and elective affinities. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 60, 307–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163600

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., and Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychol. Bull. 129, 339–375. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.339

Jost, J. T., Stern, C., Rule, N. O., and Sterling, J. (2017). The politics of fear: is there an ideological asymmetry in existential motivation? Soc. Cogn. 35, 324–353. doi: 10.1521/soco.2017.35.4.324

Jugert, P., and Duckitt, J. (2009). A motivational model of authoritarianism: integrating personal and situational determinants. Polit. Psychol. 30, 693–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2009.00722.x

Kakkar, H., and Sivanathan, N. (2017). When the appeal of a dominant leader is greater than a prestige leader. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, 6734–6739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1617711114

Kessler, T., and Cohrs, J. C. (2008). The evolution of authoritarian processes: fostering cooperation in large-scale groups. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 12, 73–84. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.12.1.73

Leonhardt, D. (2022). Follow the Science? Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/11/briefing/covid-cdc-follow-the-science.html (accessed April 3, 2022).

Mallinas, S. R., Crawford, J. T., and Frimer, J. A. (2020). Subcomponents of right-wing authoritarianism differentially predict attitudes toward obeying authorities. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 11, 134–143. doi: 10.1177/1948550619843926

Manzi, C., Roccato, M., and Russo, S. (2015). Meaning buffers right-wing authoritarian responses to societal threat via the mediation of loss of perceived control. Personal. Individ. Differ. 83, 117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.009

Marien, S., and Hooghe, M. (2011). Does political trust matter? An empirical investigation into the relation between political trust and support for law compliance: does political trust matter? Eur. J. Polit. Res. 50, 267–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01930.x

Mathiesen, K., Irischakoff, K., Coi, G., and Busquets Guàrdia, A. (2021). Droughts, fires and floods: How climate change will impact Europe. Politico. Available online at: https://www.politico.eu/article/how-climate-change-will-widen-european-divide-road-to-cop26/ (accessed January 31 2022).

Miller, D., and Ali, S. (2014). Testing the national identity argument. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 6, 237–259. doi: 10.1017/S1755773913000088

Miratrix, L. W., Sekhon, J. S., Theodoridis, A. G., and Campos, L. F. (2018). Worth Weighting? How to think about and use weights in survey experiments. Polit. Anal. 26, 275–291. doi: 10.1017/pan.2018.1

Mirisola, A., Roccato, M., Russo, S., Spagna, G., and Vieno, A. (2014). Societal threat to safety, compensatory control, and right-wing authoritarianism. Polit. Psychol. 35, 795–812. doi: 10.1111/pops.12048

Oksanen, A., Kaakinen, M., Latikka, R., Savolainen, I., Savela, N., and Koivula, A. (2020). Regulation and trust: 3-month follow-up study on COVID-19 mortality in 25 European countries. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 6, e19218. doi: 10.2196/19218

Pagliaro, S., Sacchi, S., Pacilli, M. G., Brambilla, M., Lionetti, F., Bettache, K., et al. (2021). Trust predicts COVID-19 prescribed and discretionary behavioral intentions in 23 countries. PLoS ONE 16, e0248334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248334

Peffley, M., Knigge, P., and Hurwitz, J. (2001). A multiple values model of political tolerance. Polit. Res. Q. 54, 379–406. doi: 10.1177/106591290105400207

Perra, N. (2021). Non-pharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Phys. Rep. 913, 1–52. doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2021.02.001

Perry, R., and Sibley, C. G. (2013). Seize and freeze: openness to experience shapes judgments of societal threat. J. Res. Personal. 47, 677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2013.06.006

Poushter, J., and Huang, C. (2020). Despite Pandemic, Many Europeans Still See Climate Change as Greatest Threat to Their Countries. Pew Research Center.

Ritchie, H., Mathieu, E., Rodés-Guirao, L., Appel, C., Giattino, C., Ortiz-Ospina, E., et al. (2020). Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Our World Data. Available online at: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (accessed January 31, 2022).

Roccato, M., Vieno, A., and Russo, S. (2013). The Country's crime rate moderates the relation between authoritarian predispositions and the manifestations of authoritarianism: a multilevel, multinational study. Eur. J. Pers. 28, 14–24. doi: 10.1002/per.1922

Russo, S., Roccato, M., and Merlone, U. (2020). Actual threat, perceived threat, and authoritarianism: an experimental study. Span. J. Psychol. 23:e3. doi: 10.1017/SJP.2020.7

Schnelle, C., Baier, D., Hadjar, A., and Boehnke, K. (2021). Authoritarianism beyond disposition: a literature review of research on contextual antecedents. Front. Psychol. 12, 676093. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.676093

Sibley, C. G., and Duckitt, J. (2008). Personality and prejudice: a meta-analysis and theoretical review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 12, 248–279. doi: 10.1177/1088868308319226

Sinn, J. S., and Hayes, M. W. (2018). Is political conservatism adaptive? Reinterpreting right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation as evolved, sociofunctional strategies. Polit. Psychol. 39, 1123–1139. doi: 10.1111/pops.12475

Stellmacher, J., and Petzel, T. (2005). Authoritarianism as a group phenomenon. Polit. Psychol. 26, 245–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00417.x

Stollberg, J., Fritsche, I., and Jonas, E. (2017). The groupy shift: conformity to liberal in-group norms as a group-based response to threatened personal control. Soc. Cogn. 35, 374–394. doi: 10.1521/soco.2017.35.4.374

Sullivan, J. L., and Hendriks, H. (2009). Public support for civil liberties pre- and post-9/11. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 5, 375–391. doi: 10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.093008.131525

Trommsdorff, G., and Kornadt, H.-J. (2003). “Parent-child relations in cross-cultural perspective,” in Handbook of Dynamics in Parent-Child Relations, ed L. Kuczynski (London: Sage), 271–306.

Uhl, I., Klackl, J., Hansen, N., and Jonas, E. (2018). Undesirable effects of threatening climate change information: a cross-cultural study. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 21, 513–529. doi: 10.1177/1368430217735577

Vasilopoulos, P., Marcus, G. E., and Foucault, M. (2018). emotional responses to the charlie hebdo attacks: addressing the authoritarianism puzzle. Polit. Psychol. 39, 557–575. doi: 10.1111/pops.12439

Keywords: authoritarianism, societal crises, climate change, COVID-19, trust in science, civil liberties

Citation: Hirsch M (2022) Becoming authoritarian for the greater good? Authoritarian attitudes in context of the societal crises of COVID-19 and climate change. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:929991. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.929991

Received: 27 April 2022; Accepted: 27 July 2022;

Published: 23 August 2022.

Edited by:

Jolanda van der Noll, University of Hagen, GermanyReviewed by:

Klaus Boehnke, Jacobs University Bremen, GermanyCopyright © 2022 Hirsch. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Magdalena Hirsch, bWFnZGFsZW5hLmhpcnNjaEB3emIuZXU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.