- 1Department of Political Studies, Universidad de Santiago, Santiago, Chile

- 2Center for the Study of Social Cohesion and Conflict, COES, Santiago, Chile

Does the decline in party identification lead to a decrease or an increase in affective polarization? In recent years, research about affective polarization has increased, asking whether contemporary publics polarize in terms of their affective evaluations of the opposite party. Evidence shows that, at least in some cases, there are signs of increased polarization. At the same time, however, there is evidence of a decline in party identification, suggesting that the parties no longer attract people's hearts and minds. These two results might conflict. However, whether and how affective polarization and declining partisanship are related has received little attention. To address this issue, in this article, we investigate how much affective polarization there is in Chile, how it has changed over time. We use survey data from Chile between 1990 and 2021, a country that has shown a profound and constant loss in partisanship. First, we show that affective polarization varies over time and that, at the aggregate level, the decline in partisanship does not impact affective polarization. Second, the groups that show higher polarization also change: if by 1990 the more polarized were people identifying with left-wing parties, by 2021, affective polarization is similar across groups, including those who do not identify with political parties.

Introduction

We can define affective polarization (AP) as the level of animosity between partisans, as the tendency “to view opposing partisans negatively and copartisans positively” (Iyengar and Westwood, 2015, p. 691; Druckman and Levendusky, 2019; Iyengar et al., 2019; Hernández et al., 2021). This concept originated in the United States to describe and explain changes observed in the political process (Iyengar et al., 2012). In particular, the idea that Democrats and Republicans were, more and more, disliking members of the other party (Iyengar et al., 2019). According to Iyengar et al. (2012), the source of this polarization is not ideological but affective, based on identity (Iyengar et al., 2019; Huddy and Yair, 2021). Furthermore, the increase in affective polarization seems to have significant consequences for polities (Iyengar et al., 2012, 2019; Iyengar and Westwood, 2015; Levendusky and Stecula, 2021).

Research in this area has increase in the last few years, particularly considering the theoretical and methodological challenges that it poses for comparative research. Two issues seem especially relevant. First, how are we to understand and measure affective polarization in multi-party systems? Second, how should we approach the problem of polarization in contexts of declining and low levels of political identification? The first issue is the one that has received the most attention. In this article, therefore, we pay special attention to the relationship -or lack thereof- between AP and party identification.

The increase in the percentage of people who do not identify with any party in contemporary democracies (Lupu, 2015a; Heath, 2018; Meléndez, 2022) begs the question of whether and how to measure attachments toward parties accurately, and how to interpret evidence regarding higher levels of political animosity within countries. In particular, in this article we ask how is affective polarization related to party identification in contexts with low levels of identification? Does the decline in party identification lead to a decrease or an increase in affective polarization? Who is more polarized, those who identify with a party or those who do not identify politically?

We argue that even if people do not identify with a political party, they can express positive or negative feelings toward parties. Therefore, we could measure affective polarization in the absence of a positive identification, as measured by traditional survey questions. Most current research assume that affective polarization only refers to those few who identify with a political party. If this is the case, declining and low levels of party identification at the aggregate level, and the absence of party ID at the individual level, should reduce AP, since the groups under consideration are less socially relevant and do not organize political conflict. On the other hand, however, non-identifiers could also have positive and negative feelings toward political parties. In this case, we should observe that party identification is not related to AP at the aggregate level, and, at the individual level, a weaker relationship between these two variables.

This article considers these questions using survey data from Chile from 1990 to 2021. Chile is a good case study to address these issues. First, it has a multiparty system that has been in place since the transition to democracy in 1990. Second, Chile has experienced a significant drop in levels of party identification, which has been constant and profound. Third, we have data available that allows us to assess the levels of polarization over a 30-year period, both at the aggregate and individual-level of analysis.

We show, first, that affective polarization varies over time and that, at the aggregate level, the decline in partisanship does not impact affective polarization. Second, the groups that show higher polarization levels also change: if by 1990 the more polarized people were those who identify with left-wing parties, by 2021, affective polarization is similar across groups, including those who do not identify with parties. Together, these two results suggest that affective polarization can occur in the absence of partisanship. In other words, that partisanship is not related to AP.

The article continues with a review of the literature on affective polarization, placing special attention to the relationship between AP and partisanship. Then, we present the data and methodological strategy used for the analyses, and the results obtained. Finally, we conclude and discuss potential implications of the results.

Affective polarization in low partisanship societies

As mentioned earlier, affective polarization is the animosity between supporters of different political parties in a country. It is, therefore, a way of measuring division and conflict between different social and political groups (Iyengar et al., 2012). What are the sources of AP? Two main explanations can be found on the literature (Huddy and Yair, 2021). The first explanation is based in social identity theory and argues that AP is based on how much we like and trust those who belong to groups other than our own (Iyengar et al., 2012). Second, and following classic polarization studies (Abramowitz and Saunders, 2008; Fiorina and Abrams, 2008; Fiorina et al., 2008; Hetherington, 2009), it has been argued that AP is related to the ideological distance or different stands on public policy issues (Rogowski and Sutherland, 2016; Webster and Abramowitz, 2017; Lelkes, 2021; Dias and Lelkes, 2022).

The concept of affective polarization finds its origin in social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Huddy, 2013; Rudolph and Hetherington, 2021), which postulates that people develop social identities associated with their belonging -or not- to some groups (Iyengar et al., 2012, 2019). The group with which people identify and belong is the ingroup. The opposite group is the outgroup. These groups can be of different types and be associated with different characteristics or interests of people.

People belong to some groups because they share characteristics they have not chosen. In other cases, people identify and develop a sense of belonging arising from shared interests and values. In these cases, identification and belonging are a choice of people. Whatever the group's origin, people will distinguish themselves from those who belong to the outgroup (Conover, 1984). They will develop positive emotions and evaluations for the ingroup and negative emotions and evaluations for the outgroup. When belonging to these groups is more important or salient for the definition of personal identity, the greater the conflict and perceived differences between ingroup and outgroup. Moreover, the greater the probability that these relationships will structure the political and social debate on various issues (Iyengar et al., 2019; Hobolt et al., 2020).

Although social identity theory focuses on social groupings, it is also important to note that political parties are groups that allow for a sense of identification among individuals (Mason, 2016). By identifying with a party, people develop attachment and affection toward that group and feelings of disaffection and animosity toward those who identify with other groups (Campbell et al., 1960; Iyengar et al., 2012, 2019; Iyengar and Westwood, 2015). Therefore, membership in a party helps people organize their opinions and assessments regarding political activity and opposition parties. Identification with parties structures political competition. The recurrence of elections, for example, allows the salience of party identification to be important: it structures people's preferences and dominates the political and social discussion for at least the period that the campaigns last (Hobolt et al., 2020; Hernández et al., 2021; Rodríguez et al., 2022).

Other group of researchers have argued that affective polarization is rooted not on identity but on the growing distance between parties' supporters with respect to ideology and policy preferences. As parties sort themselves in terms of ideology and policy preferences, their supporters will become more affectively polarized: they will dislike the other party's members due to the divergence on issue positions. Rogowski and Sutherland (2016), for example, argue that increased polarization among the parties' elites increase AP within the public, due to an increase relation between ideology and vote choice. When leaders polarize over ideological or policy preferences, citizens will respond by an increase in the animosity toward the opposite party and “when candidates or officeholders exhibit similar ideologies, citizens evaluate them similarly” (Rogowski and Sutherland, 2016, p. 504), decreasing AP.

Webster and Abramowitz (2017), on the other hand also argue that behind the increase AP within the American electorate, there in an increase in ideological polarization. They argue that Americans have become increasingly polarized over ideological issues -particularly those related to welfare policy-. And that this is an important driver of affective polarization in the U.S. Policy disagreement between party supporters seems to be crucial to understand AP.

The evidence regarding which explanation “works better” is still unclear (Huddy and Yair, 2021). In those studies where both identity and ideology are included show mixed results. Reiljan (2020), in a study of AP in Europe, shows that although ideological polarization is correlated with AP, the effect seems to be mediated by other factors, making ideology a weak predictor of AP. Lelkes (2021), reporting on experimental evidence, show that AP is mostly driven by ideology, rather than identity. But Dias and Lelkes (2022) show that both policy and identity play a role in citizens' affective polarization. And they also argue for the need to consider, at the same time, how those effects are mediate by the other (Dias and Lelkes, 2022, p. 787). Harteveld (2021), on the other hand, in a comparative study shows that AP increases when social sorting and political sorting occurs, highlighting the role of identities in affective polarization.

Affective polarization can be a relevant indicator of how well the democratic system works. When affective polarization is high, the possibility of reaching agreements is hampered by the way in which conflicts between groups are faced and solved (Iyengar et al., 2012; Torcal and Comellas, 2022; Torcal and Magalhaes, 2022). Research has shown that higher levels of affective polarization have effects in the political arena (Druckman et al., 2020, 2021; Kingzette et al., 2021; Rodon, 2022; Serani, 2022; Torcal and Carty, 2022), but also in other areas (Iyengar and Westwood, 2015; Iyengar et al., 2019; Rudolph and Hetherington, 2021).

Affective polarization in multi-party systems

This definition of affective polarization, and the consideration over what drives it, presents two critical challenges for comparative research. First, how do we identify ingroups and outgroups for polarization measurement in systems with more than two parties? When there are only two groups in the political arena, people will identify with one party, the ingroup. Members and leaders of the other party are part of the outgroup. In multiparty systems, on the other hand, people may like and/or dislike more than one party. In other words, there may be multiple ingroups and outgroups.

Recent research has considered this problem. Some simply avoid the issue by computing affective polarization for the two main parties (Iyengar et al., 2012; Gidron et al., 2019). Others group parties according to their ideological family or “when a coalition of parties form government” (Knudsen, 2021, p. 37). In this approach, then, AP is computed as the difference in affect between one ingroup and one outgroup, making results directly comparable to the ones obtained in the United States (Gidron et al., 2019). The problem with these solutions is that they restrict the analysis to two parties or coalitions and do not consider other partisans.

Acknowledging this problem, Reiljan (2020) proposes to measure AP as the difference between feelings for the ingroup (defined by party identification) and all other groups in the system. A variation of this proposed measured, identify the ingroup as the most-liked party, allowing for the inclusion of non-partisans in the analysis (Wagner, 2021). Finally, Wagner (2021) proposes a new measure of affective polarization -spread- which evaluates affect toward all political parties in a polity, reducing the problem of defining one ingroup and one outgroup. Additionally, this measure does not distinguish between partisans and non-partisans1. In the following analysis, we will use Wagner's measures of affective polarization to evaluate the Chilean trends from 1990 to 2021.

Using these various measures of AP, research has shown that levels of affective polarization vary between countries and over time. In the case of the United States, for example, there has been a sustained increase in the levels of animosity toward supporters of the opposing party (Iyengar and Westwood, 2015; Iyengar et al., 2019). There is also evidence showing high levels of affective polarization in other Western countries. For example, Gidron et al. (2020), in an analysis of comparative data from 1996 to 2017, show that the Netherlands and Finland are the least polarized countries, while Spain, Greece, and Portugal are the most polarized ones. They also show that in several countries, including Switzerland, France, and Ireland, “the affective polarization levels fluctuate sharply over time” (p. 28). In Germany, Canada, and New Zealand, on the other hand, affective polarization levels have declined or remained stable over this period (Gidron et al., 2020).

In a more recent comparative analysis, Torcal and Comellas (2022) incorporate 61 countries/elections, including nations from different world regions. They show that the US, for example, has the most polarized public, with a clear upward trend in affective polarization between 2004 and 2020. With respect to Latin American countries, they show varying levels of affective polarization: Uruguay in 2004 showed the highest level of polarization, while Argentina in 2007 was the least polarized one. Data for Chile only includes the 1993 and 2017 elections: in both cases, affective polarization is below the average, with higher numbers in 1993 (Torcal and Comellas, 2022, p. 8). Carlin and Love (2013, 2018) and Carlin et al. (2022) evaluate the trust gap among partisans using experimental and comparative research. They show that people trust their co-partisans more, and these results hold across different national contexts and different types of respondents. And Lauka et al. (2018) present evidence of varying levels of AP for over 40 countries from different regions.

Partisanship and affective polarization

The second major challenge to comparative research is related to the relationship between AP and partisanship. What happens to polarization and its consequences in contexts where fewer and fewer people identify with political parties? Lupu (2015b), for example, in a comparative study of mass partisanship and party polarization, shows that more polarized parties increase partisanship at the individual level. Whether or not these results hold for the relationship between affective polarization and partisanship remains open. From the point of view of measurement, then, the problem is how to identify the ingroup of non-partisans.

Iyengar and Westwood (2015) show that “not surprisingly, self-identified partisans have the highest levels of polarization, but pure Independents and independent leaners also show significant levels of partisan affect” (Iyengar and Westwood, 2015, p. 696). Following this work, we argue that non-partisans can also have affect toward parties and leaders and can report more or less positive feelings toward them. Therefore, instead of using the question of party identification, we can identify the ingroup of respondents by simply identifying the party they like the most.

The relationship between AP and partisanship could be evaluated at the aggregated and at the individual level of analysis. At the country level, we argue that a decline in partisanship (the percentage of those who identify with a party) should reduce aggregate levels of affective polarization. If parties do not longer provide the basis for identification, and people do not consider themselves to be partisans, that means that parties are less socially relevant and do not organize political conflict. As political parties loose relevance, political conflict will shift to other types of groupings, where AP will be more relevant. Research has shown that AP can emerge, and organize political conflict, with other types of groups (Mason, 2018; Hobolt et al., 2020). We could expect, then, that the emergence of these new groups might be able to displace political conflict away from parties, making AP within partisans less socially relevant. At the individual level, on the other hand, and following Iyengar and Westwood (2015) we expect to find that independents or non-partisans to exhibit lower levels of AP than partisans.

Non-identifiers, however, could also have positive and negative feelings toward political parties and leaders. In this case, we should observe that party identification is not related to AP at the aggregate level, and, at the individual level, a weaker relationship between these two variables.

Data and methods

For this study, we use the surveys carried out by the Centro de Estudios Públicos (CEP) in Chile between 1990 and 2021, which cover the 30 years since the transition to democracy in the country. This data set is unique and particularly relevant to this study for two reasons: first, the CEP has conducted, on average, between 2 and 3 surveys per year from 1990 to 20212. These surveys, additionally, are available to the public3. We used a total of 67 surveys, which we aggregated in a single database, including all the variables necessary for this study. Each of these surveys interviewed around 1,500 people aged 18 and over residing in Chile (until 1993, only in urban areas; since 1994, in urban and rural areas). Samples are selected using probabilistic procedures. And each survey's sampling error is around ±3 percentage points4.

Second, these surveys have uninterruptedly included questions assessing political leaders. These leaders usually include the presidents of political parties and other relevant figures, such as members of Congress. With these questions, we will measure the levels of affective polarization toward political parties' leaders in Chile.

Measuring affective polarization

To measure affective polarization, we must start by measuring affect attitudes toward political parties. Researchers have used different types of questions to measure affective polarization with surveys. Most of them use the feeling thermometers that ask respondents to rate political parties and/or political leaders on a 0 to 100 (or 0 to 10 in most comparative surveys) scale (Iyengar et al., 2019). The reason for this is mostly related to data availability: the ANES feeling thermometers are used frequently and have been included in comparative survey projects such as the CSES (Iyengar et al., 2019; Gidron et al., 2022; Torcal and Comellas, 2022).

It is important to note that aggregate results of affective polarization might be different depending on whether feeling questions are asked about parties, leaders, or partisans, since the object of the evaluation is different (Druckman and Levendusky, 2019; Reiljan et al., 2021). The evidence suggests, however, that these measures are, first, highly correlated, particularly those that measure affect toward parties and leaders (Reiljan et al., 2021). Furthermore, Druckman and Levendusky (2019) show that “when people evaluate the other party—as the standard measures of affective polarization ask them to do—they think of elites more than ordinary voters” (p. 119), and that “part of what scholars have called affective polarization, then, is not simply dislike of the opposing party, but is dislike of the opposing party's elites” (p. 120). We are confident, then, that using questions regarding party leaders should be comparable to political parties' evaluation.

CEP's surveys include questions very similar to the feeling thermometers commonly used in this line of research. The question reads: “Now I am going to read you a list of political figures, and I want you to tell me what you think of each of them. If you haven't heard of them, please tell me you don't know them. Using the alternatives on this card, which of these best describes your opinion about each person?” The response alternatives go from 1 “very negative” to 5 “very positive.”5

Each survey includes a list of around 30 political figures representing most of the political spectrum. We identify the party to which each political figure belonged at the time of the survey and selected those who belong to the parties under consideration. To calculate the mean party affect, we averaged the level of affection toward each political figure that belongs to that party6. Formally, affect toward the party g, for the individual i, is the average of the affect toward the political figures, f, of that party included in each survey.

Following those procedures, we measure people's affect toward nine political parties. These nine political parties have regularly competed in elections and, in addition, cover the predominant political spectrum during the 30 years considered in this work. Additionally, these parties were included in the surveys for at least five consecutive years. We measure people's affect toward the following parties (the list goes from right-wing to left-wing parties): the Independent Democratic Union (UDI), National Renovation (RN) and Political Evolution (EVOPOLI) of the right, the Christian Democratic Party (DC), the Party for Democracy (PPD), the Socialist Party (PS) and the Radical Party (PRSD), from the center-left, and the Broad Front (FA) and the Communist Party (PC), from the left.

These measures of affect toward political parties' elites are the basis for measuring affective polarization in Chile. As we mentioned before, affective polarization is traditionally defined as the distance between the level of affection toward the party to which people belong, g, (the ingroup), and the level of affection to the other party, h, (the outgroup).

As we pointed out earlier, however, this measure presents difficulties when analyzing (a) multiparty systems and (b) countries with low levels of partisanship. In these systems, people can have positive (and negative) feelings for more than one political party, making it difficult to define the ingroup and outgroup of people. In addition, if the percentages of people who say they do not identify with any party are very high, then the polarization measure is only applied to that lower proportion of the population.

We resort to Wagner's (2021) work to address these issues, using two affective polarization measures: spread and distance. Spread “is the average absolute party like-dislike difference relative to each respondent's average party like-dislike score” (Wagner, 2021, p. 4). This measure, then, evaluates the relationship of affection toward all the parties for each individual.

This measure does not identify ingroups and outgroups, so every person who expresses affect for at least two parties can be included in the analysis. Spread, then, can be computed for more than two parties and for people independently of whether they identify with one party or not. However, this measure should provide a more conservative, less extreme indication of affective polarization since the comparison considers the average feelings of all parties.

As an alternative, Wagner (2021) suggests calculating the distance between the party that obtains, for each person, the maximum score in the level of affection (the ingroup) and the average feelings toward other parties (the outgroup). This measure is the one that most relates to the traditional one. It differs in two relevant ways: first, the ingroup is the party to which the individual expresses more affect, not the declared party identification. In other words, it can be computed for partisans and non-partisans. Second, the outgroups are all other parties. People can express affect o disaffect to more than one party, and this measure includes them all in the overall index of affective polarization.

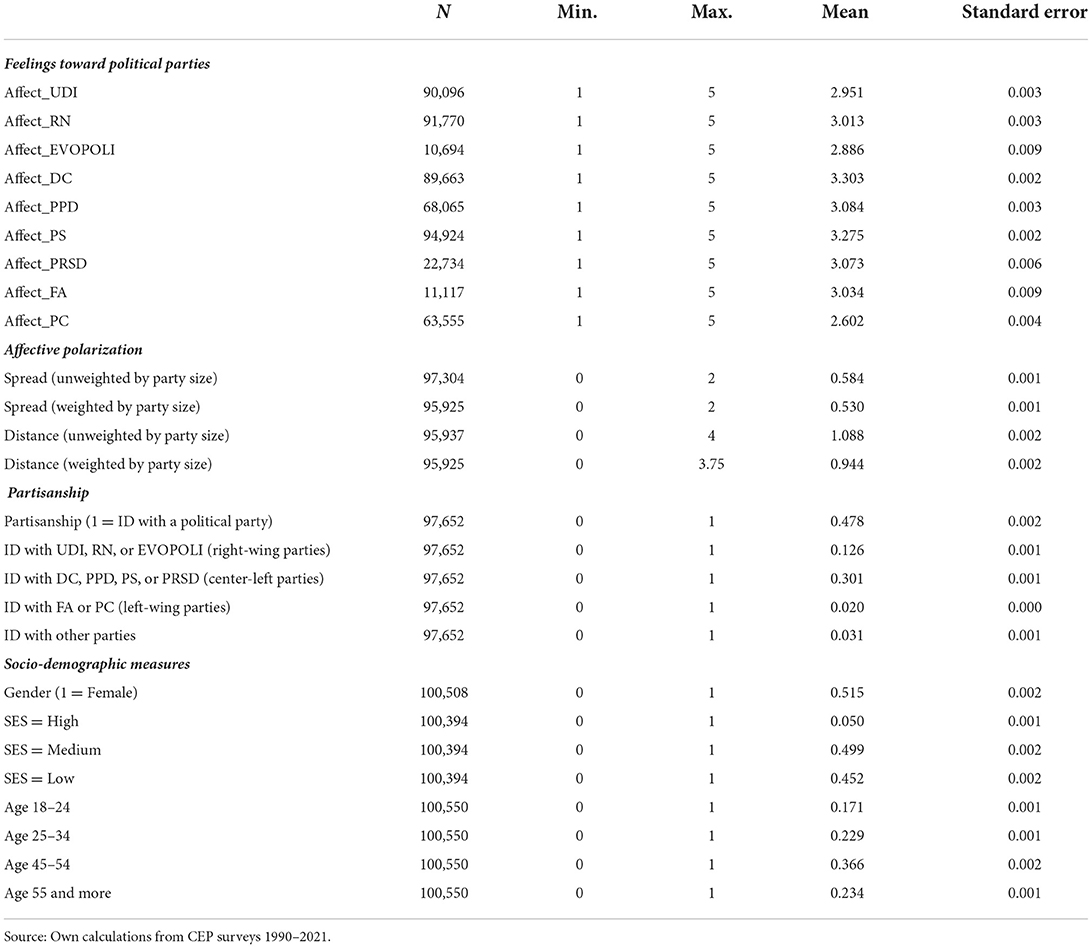

In what follows, we calculate the levels of affective polarization using these two proposed measures. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for these measures.

Weights

According to Wagner, affective polarization “matters more if the liked and disliked parties are very large competitors than if a voter happens to dislike a small party. This is because [...] larger parties are more important for the party system and government formation” (2021, p. 3). Following this argument, we also computed weighted measures of affective polarization using parties' vote share in the previous lower house election.

Two caution notes are in order. First, weighted measures do not include, for any given year, parties that did not compete in the previous election. In fluid or in-formation party systems, then, weighting can lead to a measure of affective polarization that leaves important actors out. For example, the weighted affective polarization measures in Chile that we use in this article did not include the Communist Party (PC) until 1994. This is because the PC could not compete in the parliamentary elections -as a party list- until 1993.7 Second, weighting seems relevant for a general assessment of affective polarization at the country level (Wagner, 2021). However, it is unlikely that the size of the party matters to people's attitudes and actions. In that case, unweighted measures might be more appropriate. However, more research on this point is needed. In what follows, we use both weighted -by party size- and unweighted measures of affective polarization.

Independent variables

We also use four independent variables in the analyses to be presented: partisanship, gender, age groups, and socioeconomic status of the respondents. These questions have been consistently included in CEP's surveys over the years and will allow us to test the relationship between AP and partisanship both at the aggregate and the individual level of analysis. We use age, gender, and socioeconomic status as controls.

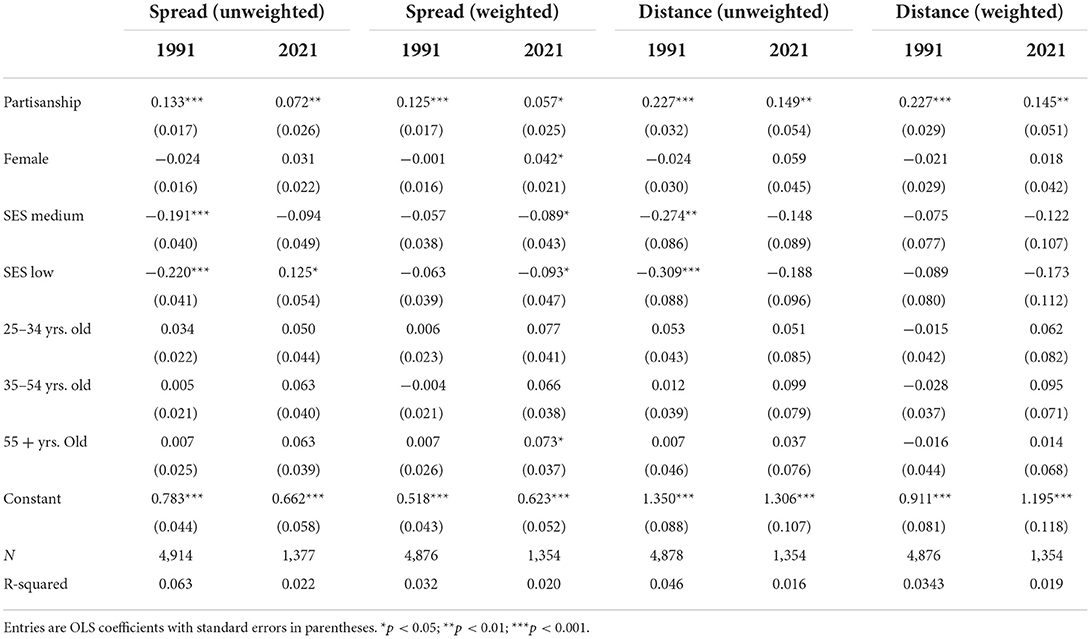

Partisanship is measured using the following question “With which of the following parties do you identify yourself?”. Answer categories vary over the years, accounting for changes within the party system. We mentioned earlier that Chile is one country where party identification has declined over time. How profound is this decline? Figure 18 shows the percentage of people identifying with parties between 1990 and 2021. As can be seen, the levels of party identification have fallen from around 80% by 1990 to less than 20% in 2021. This sharp decline suggests that political parties have lost affection and trust among Chileans (Bargsted and Somma, 2016; Segovia, 2017; Bargsted and Maldonado, 2018). We will consider later whether this decline -and the large proportions of Chileans who do not identify with parties- is related to affective polarization.

Figure 1. Party identification (estimated means with 95% CI). Source: Own calculations from CEP surveys 1990–2021.

Results

Political parties leaders' affect and affective polarization

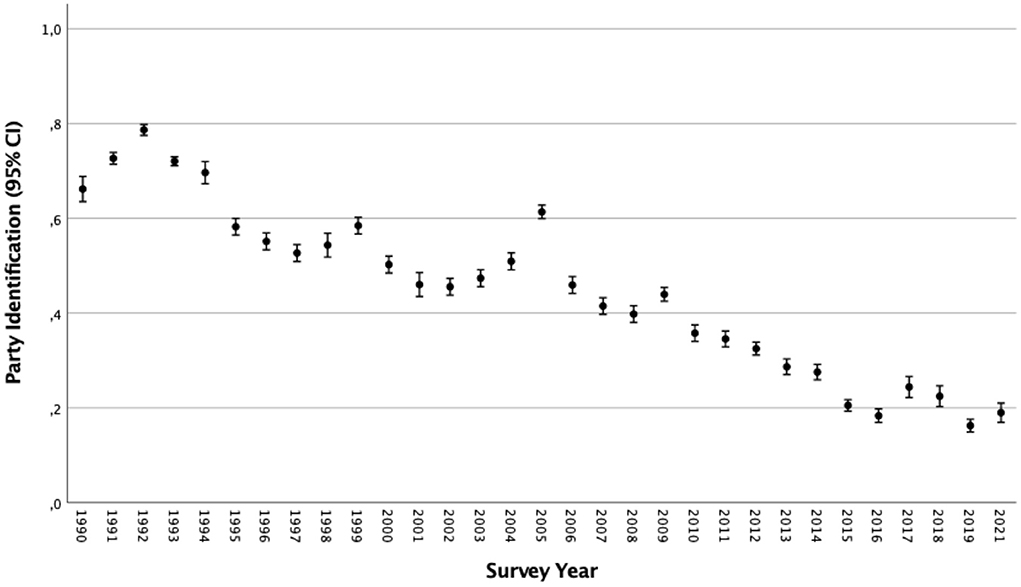

How have Chileans' levels of affect toward their political parties' leadership changed during this period? Figure 2 -and Supplementary Tables A5–A13 in the online appendix- shows the average feelings for the nine political parties between 1990 and 2021. On average, the levels of affect fluctuate for the whole period between 3.3 (se = 0.003) and 2.6 (se = 0.005), obtained by the Christian Democrats and the Communist Party, respectively. These parties are, respectively, the most-liked and the least-liked parties in Chile.

Figure 2. Party affect. 1990–2021 (estimated means with 95% CI). Source: Own calculations from CEP surveys 1990–2021.

Additionally, the data show that the levels of affect toward the parties have fallen during this period. Affect for the Christian Democrats, for example, has fallen from 3.6 (se = 0.026) in 1990 to 2.8 (se = 0.034) in 2021. In the case of the Socialist Party, the drop goes from 3.2 (se = 0.029) to 2.9 (se = 0.029) in the same period. The decline in affect for the UDI is less pronounced, from 2.9 (se = 0.040) to 2.7 (se = 0.034). On average, the level of affection for all the parties considered falls from 3.1 (se = 0.017) to 2.7 (se = 0.018). All these changes are statistically significant and show a generalized decline in the level of affection for the main political parties in Chile.

Overall, these results suggest that Chileans have become detached and more critical of political parties over the years. What consequences do these trends have for affective polarization? We'll consider these issues next.

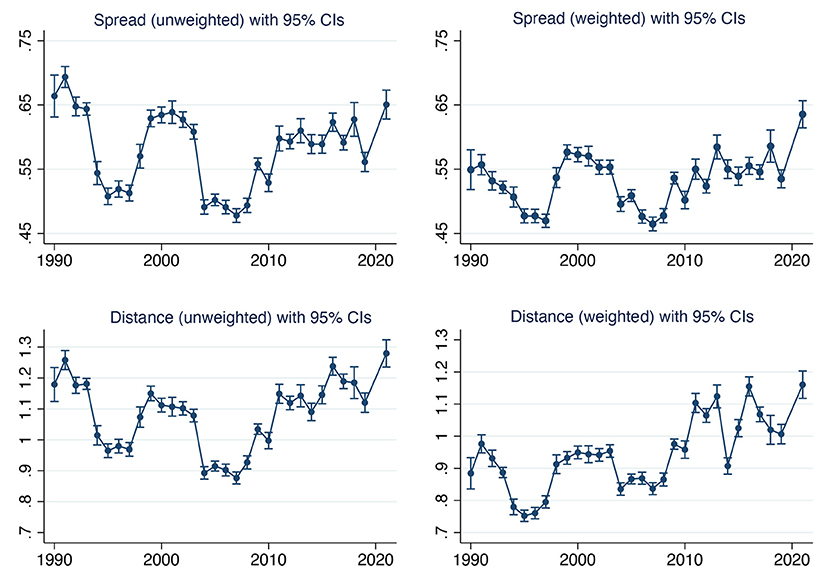

A decline in partisan affect does not necessarily imply, however, a decline in affective polarization. How have the levels of affective polarization changed in these 30 years? As we discussed earlier, in this work, we use two ways to measure affective polarization: spread and distance to the most liked party. These two measures have two important advantages over other forms of measurement. First, they allow assessing the level of affective polarization in countries with multiparty systems, as in Chile. In this way, we are not limited to evaluating polarization for two parties, but we can include them all. Second, these measures allow us to evaluate polarization even for those people who do not identify politically. Figure 3 reports the results obtained using weighted and unweighted -by party size- data. Supplementary Tables A14, A15 in the online appendix provide detailed data.

Figure 3. Trends in affective polarization. Mean spread and distance (with 95% CI). Source: Own calculations from CEP surveys 1990–2021.

The results obtained are unprecedented and very important to understand the characteristics of the Chilean political process in recent years. First, the data shows that affective polarization varies over the years, with periods of high and low AP. There is no clear pattern as, for example, the one observed in the United States and other western countries, where AP has increased or decreased steadily over the years. In the Chilean case, we can distinguish four significant stages in the levels of affective polarization: as expected, Chile begins its installation of the new democratic government with high levels of affective polarization. But this polarization began to decline rapidly, a decline observed until 1997, the second year of the government of Eduardo Frei. From 1998 to 2003 -the last years of the Frei administration and the first years of the Ricardo Lagos government- an increase in polarization is observed, which, however, does not reach the levels computed by 1990. It is important to highlight that the 1999 presidential election in which Lagos was elected was the most competitive of the period. Starting in 2003, the levels of polarization decreased again, but for a short period of time, and around 2007 (during the first government of Michelle Bachelet), a progressive and systematic increase in polarization was observed. Toward 2021, the levels of affective polarization are equal to or higher -depending on the measure used- than those of 1990. In short, AP presents ups and downs over this 30 year period.

Second, it is important to mention that the observed data in the spread measure of affective polarization appears to be more attenuated than the distance measure. This occurred due to differences in the way of measurement. When using spread, polarization is calculated with respect to the average affect toward the parties. Since this has systematically decreased in Chile, then the difference in affect toward the different parties will be smaller. However, the conclusions regarding the previous analysis are maintained. When using distance, polarization is calculated relative to the maximum value of affect observed. What the most pronounced curve of the last period indicates, then, is that not only is there a lower valuation of all the parties but also that the distance between them and the most valued one has increased in a systematic and statistically significant way.

Third, there are also differences between weighted by party size and unweighted results. However, these differences do not seem to arise as much from the different sizes of parties. But from the parties that are included in each measure. In particular, whether the Communist Party is or is not included makes affective polarization more or less pronounced, suggesting that negative feelings toward this party may be a driver of AP in Chile.

Partisanship and affective polarization

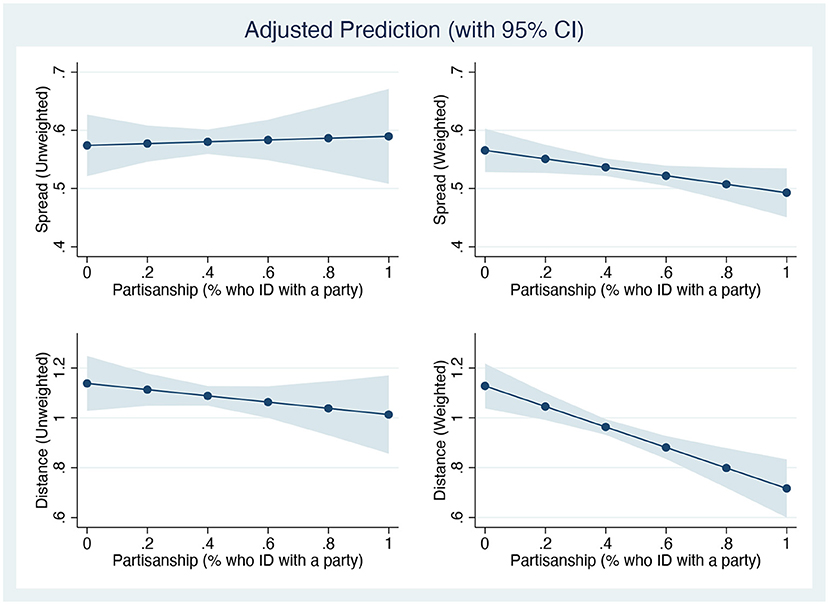

Finally, we need to consider whether affective polarization is related -and how- to declining levels of partisanship. As a starting point, we regress average levels of partisanship per year (n = 31) on the different measures of affective polarization. Figure 4 show predicted values of AP at different levels of partisanship (see full results in Supplementary Table A16 in the online appendix).

Figure 4. Predicted values of AP under different levels of partisanship. Source: Own calculations from CEP surveys 1990–2021.

As can be observed, at the aggregate level, higher levels of partisanship are negatively related to affective polarization. In other words, polarization is, on average, lower when higher proportions of people identify with a party. But the relationship is statistically significant only in one model. This result is different to our initial expectations and suggests that AP may not be driven by group identities as proposed by previous research.

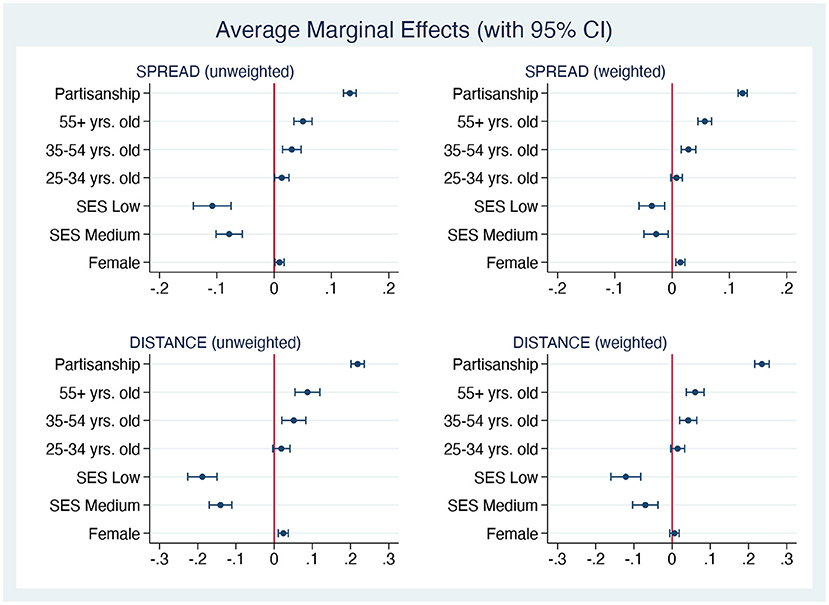

Do these results hold when observing individual level data? To test the relationship between AP and partisanship, we ran hierarchical linear models for the full sample in which we regress partisanship, gender, age group, and socioeconomic status on the four measures of polarization—(weighted and unweighted) spread and distance. We controlled for the year in which each measurement was made. Figure 5 show marginal effects of these variables on affective polarization. Full results are in Supplementary Table A17 of the online appendix.

Figure 5. Correlates of affective polarization. Source: Own calculations from CEP surveys 1990–2021.

Results indicate, first, that in Chile, partisanship (whether respondents identify with a political party) is the factor that shows the strongest relationship to affective polarization, controlling for other factors. This indicates that those who identify with a party show higher levels of AP than those who do not identify. These results also indicate that AP in Chile is, controlling to other factors, higher among women, older respondents, and those with high socioeconomic status.

So far, we have shown that as partisanship decline there seems to be an increase in AP and that, at the same time, those with a positive partisan identification show higher levels of AP. How can we interpret these results? We suggest that that AP remains high or may be even higher under conditions of low partisanship if those who do not identify with a party show at the same time, high levels of AP. The decline in partisanship, then, does not reduce AP since non-identifiers are also polarized.

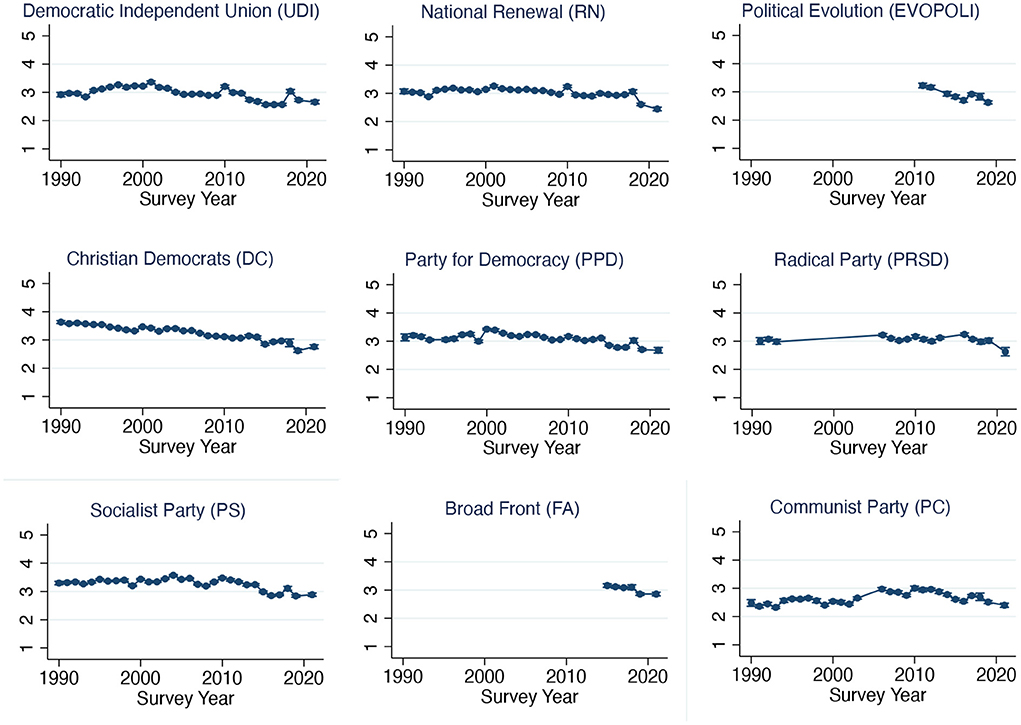

Of course, correlation does not mean causation. In order to test this argument, therefore, we would need panel data to evaluate the impact of changes in the environment and of individual partisanship on AP. Unfortunately, we do not have access to this type of information in the Chilean case. As an alternative, we run OLS regression for 1991 and 2021 to evaluate how has the impact of partisanship on AP changed over the years. If the argument proposed is true, we should observe a decline in the magnitude of the correlation between partisanship and AP. The results are shown in Table 2.

As expected, the impact of partisanship is reduced over time as Table 2 shows (see Supplementary Tables A18, A19 in the online appendix for results in other periods). Both in periods with high partisanship (as in 1991) and low partisanship (as in 2021), identification with a party increases the level of AP. But this correlation is smaller in periods of lower partisanship: non-identifiers, then, also polarize affectively over party leadership.

To consider this matter further we run the same regression models as before and included a new variable that identify the political party that respondents like the most. Since partisanship has decline steadily in Chile, party identification provides little help in defining ingroups. But we can identify the most-liked group from the affect toward parties' leadership. The advantage of this measure is that it does not require a positive identification from respondents. Ingroups are a derived variable from the observable levels of affect. This measure also proves to be limited since, in a multiparty system, people can like more than one party. Overall, in a 70% of those respondents with a measure of affective polarization we can identify one most-liked party9. We'll use this subset of respondents in what follows.

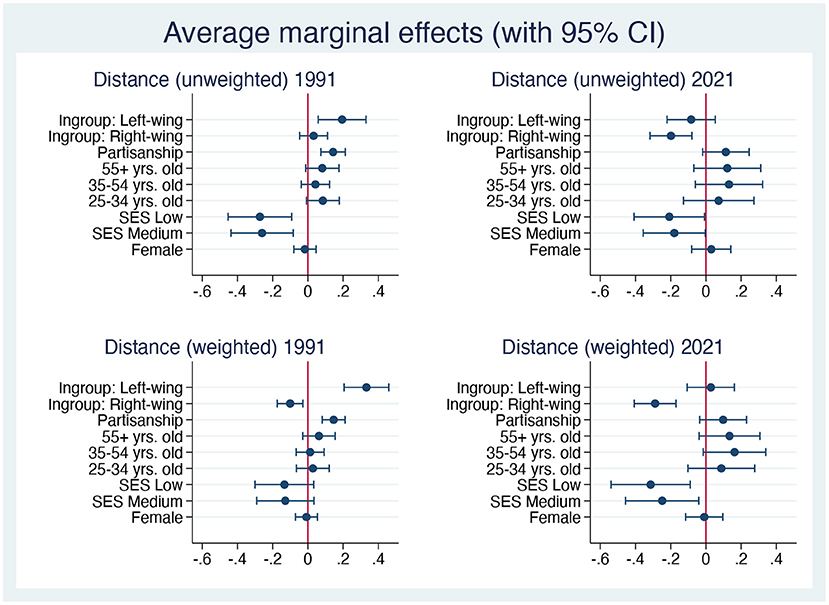

Figure 6 show the average marginal effects for 1991 and 2021, and Supplementary Table A20 in the online appendix presents full results. In this case we regress gender, socioeconomic status, age, partisanship, and most-liked party on affective polarization (measure by Distance). As indicated before, we measure affect toward nine political parties' leaders. In here, we group those parties in three groups: parties that belong to the center-right (UDI, RN and Evopoli), the center left (DC, PPD, PS, and PRSD) and to the left (FA and PC). We use the center-left coalition as the base category.

Figure 6. Correlates of affective polarization. Source: Own calculations from CEP surveys 1990–2021.

The results confirm, first, the lower relevance of partisanship by the end of the period, as compared to 1991. In effect, to identify with a party is an important indicator of higher AP among Chileans at the beginning of the 1990s. By 2021, on the contrary, to identify with a party is no longer a relevant factor associated with polarization. The results also highlight a change between 1991 and 2021 with respect to the groups that appear to be more affectively polarized.

Compared to the levels of AP of the center-left coalition (our base category), the more polarized are those who can be considered closer to the left-wing parties. In 2021, meanwhile, the levels of affective polarization are lower in right-wing supporters as compared to other groups. Left-wing supporters have similar levels of AP than those who are closer to the center-left coalition. In other words, by 2021, affective polarization is a widespread phenomenon.

Conclusions

Interest on affective polarization has boomed the last 10 years, both in academic research as in everyday political discussions. This interest derives from the observation that in contemporary societies there is a higher level of conflict—a conflict that is based on affect- between parties and partisans. Of course, conflict is part of political life. But an increase in AP appears to have unique consequences that make the resolution of those conflicts more difficult and that extend those partisan differences into everyday life. At the same time, however, we can also observe an increase in the percentages of people who do not identify with any political party suggesting that parties no longer attract people's hearts and minds. This decline in partisanship and the changes in affective polarization that we observe, therefore, seem to be at odds. We consider this puzzle and ask how does affective polarization relate to party identification? To address this question, we used survey data from Chile, covering the 30-year period that started with the new democratic governments after the dictatorship in 1990, until 2021, a few months before the last presidential election. This is a good case to study because it has experienced a large and steady decline in partisanship and because there's been public discussions about an increase in polarization in Chilean politics.

We showed, first, that affective polarization varies over time and that, by the end of this 30 years period, affective polarization is as high as the one observed at the beginning of the 1990s. This result indicates that affective polarization is not only a matter of partisans, it can also be present among those who do not declare identification with a party. Second, the groups that show higher polarization also change: if by 1990 the more polarized were people identifying with left-wing parties, by 2021, affective polarization is similar across groups, including those who do not identify with political parties. People can have positive and negative feelings toward parties, and those feelings are not the same. The results suggest that people, even among those who do not identify with a party, like some parties more than others. And the distance among the most liked party and other political groups -what we call affective polarization- can and should be measured.

These results are important for several different reasons. First, this paper investigated and analyzed affective polarization in Chile, widening the existing research scope, which mainly considers the cases of the United States and Western European countries. Information about new cases is crucial for the expansion of comparative research in this area, helping develop modified and new hypotheses and theories about the origins and consequences of affective polarization. In particular, the inclusion of middle-income or less developed democracies should help shed light on some open questions.

Second, the results presented are one more indication that affective polarization might change over time, and that, therefore, we need to look closely at the political processes behind those changes. Some trends might be explained by general or global factors, but we need to evaluate how they relate to country-specific ones.

Third, and more importantly, we believe that these results show that the interaction between partisanship and affective polarization is crucial and should not be avoided in future research. As we saw, affective polarization can and should be measured for all, not only for those who identify with a political party. When we only consider partisans, we ignore significant parts of the respondents. Since everyone may express affection toward parties, we can measure affective polarization for all of them. Additionally, the results show that affective polarization might be higher within partisans, but they also show that it can be as high for partisans as for non-partisans. What explanations might be behind these different patterns is something we need to investigate further.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: www.cepchile.cl.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by Centro de Estudios de Conflicto y Cohesión Social—COES—ANID/FONDAP/15130009 and by Universidad Diego Portales. Fondo de Investigación para Académicas.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.928586/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

. ^1 Other measures have also been considered. Lauka et al. (2018), for example, propose a measure -based on the concept of positive and negative partisanship- that computes the difference between the percentage of people that would vote for a party and the percentage that would never vote for it, allowing to consider AP at the country level (but not at the individual level). And Carlin and Love (2013, 2018) and Carlin et al. (2022) use the questions of trust in political parties to develop an affective polarization measure.

. ^2 Except for the year 2020, when CEP conducted no surveys due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

. ^3 Databases, questionnaires, and methodological documents can be found at www.cepchile.cl.

. ^4 Supplementary Table A1 in the online appendix show the main characteristics of the surveys included in the analyses.

. ^5 A complete list of political figures included in the measurement of parties' affect is included in Supplementary Table A2 in the online appendix.

. ^6 For the analysis, we do not consider those who do not know the politician or do not give an opinion. The percentage of missing values for each political leader. To compute affect, however, we do not require that each respondent answer every question. Instead, we compute affect considering the parties that respondents evaluated. This procedure allows us to keep as many cases as possible in the analysis. Supplementary Table A3 in the online appendix shows the percentage of missing values for each party in each survey considered.

. ^7 For a detailed account of the 1989 parliamentary election in Chile, see Angell and Pollack (1990).

. ^8 See Supplementary Table A4 in the Online Appendix for detailed data on partisanship.

. ^9 This is almost twice the number of those who identify with a party.

References

Abramowitz, A. I., and Saunders, K. L. (2008). Is polarization a myth? J. Polit. 70, 542–555. doi: 10.1017/S0022381608080493

Angell, A., and Pollack, B. (1990). The Chilean elections of 1989 and the politics of the transition to democracy. Bull. Lat. Am. Res. 9, 1–23. doi: 10.2307/3338214

Bargsted, M. A., and Maldonado, L. (2018). Party identification in an encapsulated party system: the case of postauthoritarian Chile. J. Polit. Latin Am. 10, 29–68. doi: 10.1177/1866802X1801000102

Bargsted, M. A., and Somma, N. M. (2016). Social cleavages and political dealignment in contemporary Chile. 1995–2009. Party Polit. 22, 105–124. doi: 10.1177/1354068813514865

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., and Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American Voter. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Carlin, R. E., González, R., Love, G. J., Miranda, D. A., and Navia, P. D. (2022). Ethnicity or Policy? The conditioning of intergroup trust in the context of ethnic conflict. Polit. Psychol. 43, 201–220. doi: 10.1111/pops.12747

Carlin, R. E., and Love, G. J. (2013). The politics of interpersonal trust and reciprocity: an experimental approach. Polit. Behav. 35, 43–63. doi: 10.1007/s11109-011-9181-x

Carlin, R. E., and Love, G. J. (2018). Political competition. Partisanship and interpersonal trust in electoral democracies. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 48, 115–139. doi: 10.1017/S0007123415000526

Conover, P. J. (1984). The influence of group identifications on political perception and evaluation. J. Polit. 46, 760–785. doi: 10.2307/2130855

Dias, N., and Lelkes, Y. (2022). The nature of affective polarization: disentangling policy disagreement from partisan identity. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 66, 775–790. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12628

Druckman, J. N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M., and Ryan, J. B. (2020). How Affective Polarization Shape's Americans' Political Beliefs: A Study of Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Experimental Political Science 8, 223–234. doi: 10.1017/XPS.2020.28

Druckman, J. N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M., and Ryan, J. B. (2021). Affective polarization. Local contexts and public opinion in America. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 28–38. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01012-5

Druckman, J. N., and Levendusky, M. S. (2019). What do we measure when we measure affective polarization? Public Opin. Q. 83, 114–122. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfz003

Fiorina, M. P., Abrams, S., and Pope, J. C. (2008). Polarization in the American public: misconceptions and misreadings. J. Polit. 70, 556–560. doi: 10.1017/S002238160808050X

Fiorina, M. P., and Abrams, S. J. (2008). Political polarization in the American public. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 11, 563–588. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.053106.153836

Gidron, N., Adams, J., and Horne, W. (2019). Toward a comparative research agenda on affective polarization in mass publics. APSA Comp. Polit. Newslett. 29, 30–36.

Gidron, N., Adams, J., and Horne, W. (2020). American Affective Polarization in Comparative Perspective (Elements in American Politics). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108914123

Gidron, N., Sheffer, L., and Mor, G. (2022). Validating the feeling thermometer as a measure of partisan affect in multi-party systems. Elect. Stud. 80, 102542. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2022.102542

Harteveld, E. (2021). Ticking all the boxes? A comparative study of social sorting and affective polarization. Elect. Stud. 72, 102337. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102337

Heath, O. (2018). “Trends in partisanship,” in The Routledge Handbook of Elections. Voting Behavior and Public Opinion, ed. Justin Fisher, Edward Fieldhouse, Mark N. Franklin, Rachel Gibson, Marta Cantijoch and Christopher Wlezien (New York: Routledge), 158–169.

Hernández, E., Anduiza, E., and Rico, G. (2021). Affective polarization and the salience of elections. Elect. Stud. 69, 102203. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102203

Hetherington, M. J. (2009). Review article: putting polarization in perspective. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 39, 413–448. doi: 10.1017/S0007123408000501

Hobolt, S., Leeper, T. J., and Tilley, J. (2020). Divided by the vote: affective polarization in the wake of the brexit referendum. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 1476–1493. doi: 10.1017/S0007123420000125

Huddy, L. (2013). “From group identity to political cohesion and commitment,” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, eds. L. Huddy. D. O. Sears. and J. S. Levy (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 737–773. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199760107.013.0023

Huddy, L., and Yair, O. (2021). Reducing affective polarization: warm group relations or policy compromise? Polit. Psychol. 42, 291–309. doi: 10.1111/pops.12699

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., and Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., and Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology. A Social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opin. Q. 76, 405–431. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfs038

Iyengar, S., and Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: new evidence on group polarization. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 59, 690–707. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12152

Kingzette, J., Druckman, J. M., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M., Ryan, J. B., et al. (2021). How affective polarization undermines support for democratic norms. Public Opin. Q. 85, 663–677. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfab029

Knudsen, E. (2021). Affective polarization in multiparty systems? comparing affective polarization towards voters and parties in Norway and the United States. Scandinavian Polit. Stud. 44, 34–44. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.12186

Lauka, A., McCoy, J., and Firat, R. B. (2018). Mass partisan polarization: measuring a relational concept. Am. Behav. Scient. 62, 107–126. doi: 10.1177/0002764218759581

Lelkes, Y. (2021). Policy over party: comparing the effects of candidate ideology and party on affective polarization. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 9, 189–196. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2019.18

Levendusky, M. S., and Stecula, D. A. (2021). We Need to Talk. How Cross-Party Dialogue Reduces Affective Polarization. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781009042192

Lupu, N. (2015a). “Partisanship in Latin America,” in The Latin American Voter: Pursuing Representation and Accountability in Challenging Contexts. Ann Arbor, eds R. Carlin, M. Singer and E. Zechmeister (MI: University of Michigan Press), 226–245.

Lupu, N. (2015b). Party polarization and mass partisanship: a comparative perspective. Polit. Behav. 37, 331–356. doi: 10.1007/s11109-014-9279-z

Mason, L. (2016). A cross- cutting calm. How social sorting drives affective polarization. Public Opin. Q. 80, 351–377. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfw001

Mason, L. (2018). Ideologues without issues: the polarizing consequences of ideological identities. Public Opin. Q. 82, 280–301. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfy005

Meléndez, C. (2022). The Post-Partisans Anti-Partisans. Anti-Establishment Identifiers. and Apartisans in Latin America. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108694308

Reiljan, A. (2020). ‘Fear and loathing across party lines’ (also) in Europe: affective polarisation in European party systems. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 59, 376–396. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12351

Reiljan, A., Garzia, D., da Silva, F. F, and Trechsel, A. H. (2021). “Patterns of affective polarization in the democratic world: comparing the polarized feelings towards parties and leaders”. Paper presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions. Online conference. 17–28 May.

Rodon, T. (2022). Affective and territorial polarisation: the impact on vote choice in Spain. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 27, 147–169. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2022.2044235

Rodríguez, I., Santamaría, D., and Miller, L. (2022). Electoral competition and partisan affective polarisation in Spain. South Eur. Soc. Polit. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2022.2038492

Rogowski, J. C., and Sutherland, J. L. (2016). How ideology fuels affective polarization. Polit. Behav. 38, 485–508. doi: 10.1007/s11109-015-9323-7

Rudolph, T. J., and Hetherington, M. J. (2021). Affective polarization in political and nonpolitical settings. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 33, 591–606. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edaa040

Segovia, C. (2017). “Malaise and democracy in Chile,” in Malaise in Representation in Latin American Countries, eds A. Joignant, M. Morales and C. Fuentes (New York: Palgrave Macmillan), 69–92. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-59955-1_3

Serani, D. (2022). In-party like. Out-party dislike and propensity to vote in Spain. South Eur. Soc. Polit. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2022.2047541

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. (1979). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict,” in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds. W. G. Austin and S. Worchel (Monterey: Brooks-Cole), 33–47.

Torcal, M., and Carty, E. (2022). Partisan sentiments and political trust: a longitudinal study of Spain. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 27, 176–196. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2022.2047555

Torcal, M., and Comellas, J. M. (2022). Affective polarisation in times of political instability and conflict. Spain from a comparative perspective. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 27, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2022.2044236

Torcal, M., and Magalhaes, P. C. (2022). Ideological extremism. Perceived party system polarization, and support for democracy. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 14, 188–205. doi: 10.1017/S1755773922000066

Wagner, M. (2021). Affective polarization in multiparty systems. Elect. Stud. 69, 102199. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102199

Keywords: affective polarization, Chile, partisanship, measurement, political attitudes

Citation: Segovia C (2022) Affective polarization in low-partisanship societies. The case of Chile 1990–2021. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:928586. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.928586

Received: 25 April 2022; Accepted: 07 November 2022;

Published: 21 November 2022.

Edited by:

Andres Reiljan, University of Tartu, EstoniaReviewed by:

Gregory Love, University of Mississippi, United StatesDanilo Serani, University of Salamanca, Spain

Copyright © 2022 Segovia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carolina Segovia, Y2Fyb2xpbmEuc2Vnb3ZpYS5hQHVzYWNoLmNs

Carolina Segovia

Carolina Segovia