- 1School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, Central Queensland University, Rockhampton, QLD, Australia

- 2Department of Epidemiology and Global Health, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden

- 3School of Medicine, University of Notre Dame, Fremantle, WA, Australia

Community-based social models of care for seniors promote better outcomes in terms of quality of life, managing chronic illness and life expectancy than institutional care. However, small rural areas in high income countries face an ongoing crisis in coordinating care related to service mix, workforce and access. A scoping review was conducted to examine initiatives that promoted integrated models of multisectoral, collaborative aged care in rural settings which could help respond to this ongoing crisis and improve responses to emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic. A systematic database search, screening and a two-stage full text review was followed by a case study critical appraisal. A content analysis of extracted data from included papers was undertaken. Integrated care services, activities and facilities were identified that helped guide the review process and data synthesis. The three included case studies all emphasized key principles that crucially underpinned the models related to collaboration, cooperation and innovation. Challenges to effective care included fiscal and structural constraints, with underlying social determinant impacts. Based on these findings, we describe the genesis of a “toolkit” with components of integrated models of care. Effective care requires aging to be addressed as a complex, interconnected social issue rather than solely a health problem. It demands a series of coordinated system-based responses that consider the complex and heterogeneous contexts (and needs) of communities. Such models are underpinned by leadership and political will, working with a wide breadth of stakeholders across family, community and clinical domains in private and public sectors.

Introduction

Social care for aged people in rural areas: A global concern

Research in high-income countries [as per the World Bank definition (World Bank, 2022)] has shown that home and community-based social care for seniors (people aged 65 years or more) promote better outcomes in terms of quality of life, managing chronic illness and life expectancy than residential care (Vanleerberghe et al., 2017). Residential care is defined as the care and services received when living in an institutional care facility, including aged care homes (Falk et al., 2013 #131). Home and community care is also typically less expensive than residential care (Kok et al., 2015).

Social care services for seniors are important and has been defined as providing assistance with activities of daily living, maintaining independence, social interaction and facilitating appropriate and proportionate transition to increased support (NHS, 2022). However, these home and community-based services tend to be complex and fragmented, with multiple providers and streams of activity involving personal care, home maintenance, transport, and transfers to and from medical services (Auvinen et al., 2011). These complexities and fragmentations have been exacerbated by an escalating “crisis of care” in high income countries because of aging population, declining tax bases and severe workforce shortages (Nelson, 2019).

The crisis is particularly acute in small rural areas, where resource constraints exist across the entire health and care system, and have been starkly revealed through the compounding effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (Henning-Smith, 2020). Small rural areas face particular challenges in coordinating home and social care services. As well as fewer care providers, there are also likely to be fewer services available “on hand,” with particular challenges in accessing health and care professionals–particularly specialists-and more limited workforce training opportunities. Small rural populations make it difficult to financially sustain services and they may also be comparatively deprived or economically disadvantaged (Kneis and Baker, 2020). Dispersed rural populations lead to uneven and haphazard access to care with attendant inefficiencies, yet they have the same regulatory requirements to provide access to home and social care services as their urban counterparts. As a result, exactly how all or even many of these improvements in social care can be implemented and sustained in small rural communities without exacerbating the resource crisis is unclear, as there are few studies which consider care systems in these contexts holistically or their implications at a policy level (Scharf et al., 2016).

A growing body of literature is concerned with how social care services can be better coordinated at the local level to alleviate the crisis(es) and improve the quality and accessibility of care for seniors in rural areas (Jasper et al., 2019; Davies et al., 2020; Mah et al., 2021).

The literature describes a suite of strategies to encourage better uptake of home and social care services include improving service-patient communication, case management, increasing opportunities for social interaction including volunteering and social support groups, increased support for informal carers, early exposure to home care before needs escalate, educating seniors about how to live with chronic illness, better articulation with medical care needs and “advanced care planning” that provides longer term security about service access (Brodaty et al., 2005; Sandsdalen et al., 2016; Lindquist et al., 2018; Giraudeau and Bailly, 2019; Australian Government, 2020; Ohta et al., 2020; Fournier and Lassen, 2021).

A developing global move toward “reablement” is aimed at helping seniors improve their functioning as a focus of home care services (Aspinal et al., 2016) and represents a philosophical shift from a system which otherwise assumes that care needs will inevitably increase over time. Successful reablement strategies require a focus on improving social connectivity along with improving independent living skills (Doh et al., 2020), promoting capacity (and capabilities) with clients and/ or carers through education and training, particularly in risk assessment (Wilde and Glendinning, 2012; Larsson et al., 2013; Luker et al., 2019). Informal carers play a critical role in this reablement, influencing decisions to move to residential care (Calvó-Perxas et al., 2018; de Souza Alves et al., 2019).

The aim of this scoping review was to identify examples of case studies which could provide insights into addressing the challenges of coordinating integrated (linked social and medical, as opposed to solely medical) aged care services in small rural communities. We were particularly interested in exploring the governance of coordination, responsibilities and the mix of services.

The local context

The genesis of the review arose from a project investigating patterns of use of aged care services in Storumans Kommun, a small rural municipality in northern Sweden (The Storuman Cares Project Team, 2021), where over 40% of the population live in small, dispersed villages (about 7,000 residents spread over 8,000 km2). There are typically large distances to medical services: the municipality has two small primary care facilities, with the nearest more advanced services located 200 km away, and tertiary services 350 km away. These types of settings are widely considered to be barely able to support basic health and care services, and in need of innovative models of care that are as yet poorly developed (Asthana and Halliday, 2004; Scott et al., 2012). Apart from distance, access to quality services in this region is challenged by a lack of appropriately skilled care workers, increasingly complex health needs and multi-morbidities for an aging population, as well as escalating funding constraints. The immediate motivation for the project was a very high fatality rate in residential care facilities during the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting the need to change the balance of care from residential to home and community based (Gaspar et al., 2020). This in turn required a substantial commitment by the municipality to investigate and implement change as the crisis(es) continued, resisting the temptation to put innovation processes “on hold” (Schmidt et al., 2022).

Municipalities in Sweden are responsible for the provision of social care: that is, non-medical care services that help people with activities of daily living. Medical care is the responsibility of provincial governments, although municipalities have a role in coordinating transfers between medical and social care systems (Andersson Bäck and Calltorp, 2015). While some models of care coordination have been developed in urban areas in Sweden (Andersson Bäck and Calltorp, 2015), there are no such equivalent examples in rural settings.

Our review therefore provides direct input into the planning activities of Storumans Kommun as well as insights for small rural communities globally into how “barely viable” services may be organized and sustained.

Methodology

Study design

A scoping review was used to map the extent, range, and nature of research activity, and to identify research gaps in the existing literature (Arksey and O'malley, 2005; Daudt et al., 2013), rather than summarize the available research on a specific question using an unbiased synthesis (Cochrane Training, 2021).

The review used the framework and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018; Peters et al., 2021). The following questions guided the review process.

1. What initiatives exist that promote models of optimum multifaceted, multisectoral collaborative social care in rural settings for older people?

2. What components of care are associated with these initiatives, and what are the challenges identified in implementing these?

3. What is the level of evidence for each of these principles of care available to inform practice, policymaking, and research?

Outcomes

The primary outcome for this study was integrated models of care (the provision of “social care” as defined above or linked “social and medical care” rather than purely “medical care)” for seniors in rural areas of high-income countries. The specific outcomes examined, included: strategies to provide home care, home visits, coordination of services, access to medical consultations, rehabilitation services, case management, transport services, residential care and shared care, offered to seniors as a package under one service. We defined “rural areas” in the context of high-income countries as service catchments with primary (medical) care service facilities only, and more than 1 h from secondary and tertiary care services.

Ethics

The study was exempt from ethics approval because the research was not conducted with humans or animals and used publicly available data.

Eligibility

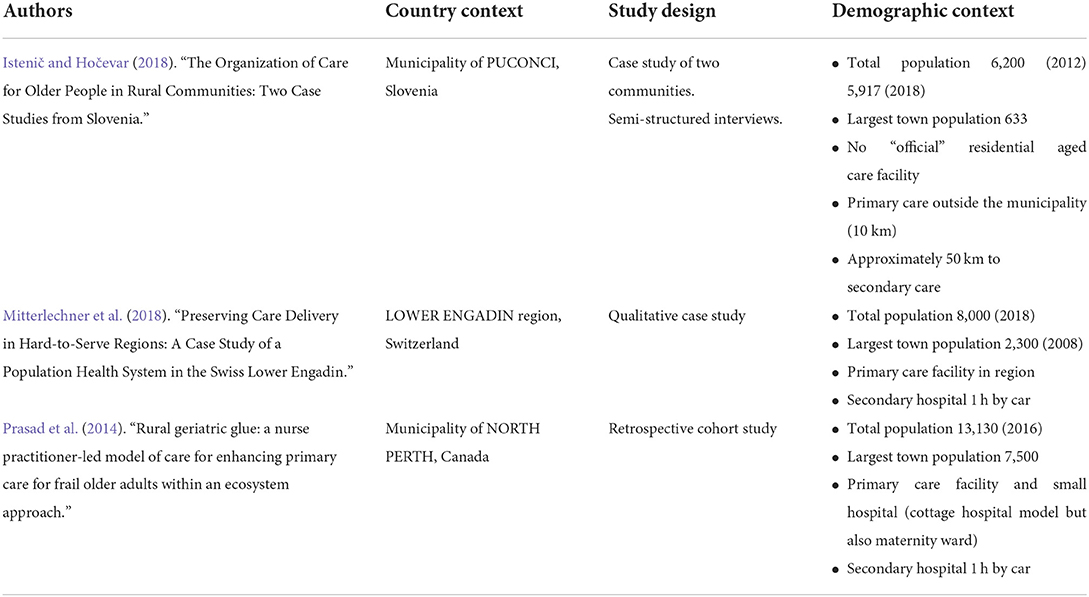

Eligibility criteria comprised peer-reviewed primary research and review articles published in English that described integrated models of social care for elder people in rural high-income country settings (see Table 1 below). The review was conducted in September 2021 by a team of five researchers.

Inclusion criteria

We included studies that focused on (1) service catchment with little more than primary (medical) care services, more than 1 h from secondary care; (2) a collection of interacting and integrated facilities, programs and services targeted at seniors, (3) aged 70+ years in the Storuman context, but often 65+ in other high and middle income country contexts; (4) “social” care, rather than “medical” care in isolation (although services linking social and medical are important); (5) “integrated care” or “integrated services” or “municipal services” or local council level services (first form of government) or county level services; (6) examples of models or toolkits, evaluations, implementation research, case studies; (7) scientific evidence for “success;” and high-income countries as per World Bank definition (World Bank, 2022).

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if (1) they focused on urban or rural areas with a large population; (2) the services studied were fragmented or medical care alone or based on stand-alone models of services; (3) the target population were under 65 years of age; (4) the studied services were offered at a state, provincial, or national level; (5) they were theoretical models, not case studies; (6) they did not find any evidence of success; (7) their settings were in low- or middle-income countries.

A detailed information about inclusion and exclusion criteria and their rationale are outlined in Supplementary material 1.

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted of the following electronic databases and online search registers in April 2021. EBSCOHost including CINAHL, and Scopus databases were searched based on pre-defined search terms for articles published any year up to 2021. A two-stage search process was conducted, with associated separate blocks of search terms. The first block of the search included: rural AND municipal* AND older* AND aged care* AND case stud*. The second block included: rural AND older* AND aged care* AND case stud*. Using or excluding the term “case stud*” made no difference to the number of articles returned, suggesting that the search database function was robust enough to identify equivalents of case studies. The term “case study” used in only 3 of the 12 full text reviewed articles (see below). Equivalent terms included “study” (three articles), “describes/ description” (three), “project,” “example” and “examines” (one each). Gray literature and government reports were also searched, as well as other recommended sources through consultation with external experts.

Refer to Supplementary material 2 for detailed information on the two blocks of search terms.

Study selection

All searches and screening were performed by co-author DC. The first block search term identified 60 articles of which 52 were excluded when screened by title, abstracts and keywords. The second block search term uncovered 686 articles, 667 of which were excluded based on title, abstract, and keyword screening. Two duplicates were removed from the remaining 27 articles, resulting in 25 articles. One source from an external recommendation was included, resulting in 26 articles considered for full text review. All publications that met the inclusion criteria from title and abstract review or those that could not be excluded had the full text retrieved. Full texts of the 26 papers (including two additional results from cited literature and references) were reviewed by DC. Of these, 16 documents were excluded based on study location and/or study type (see PRISMA flow chart in Supplementary material 4 for the described screening and reviewing processes).

Twelve papers were included for full text reading. A second full text reading by DC, AMH and GV resulted in nine excluded documents (see Supplementary material 3) and three included reports. A data extraction tool was developed using Microsoft Excel and the screening process and references were managed in Endnote 20.

Data synthesis and quality assessment of included studies

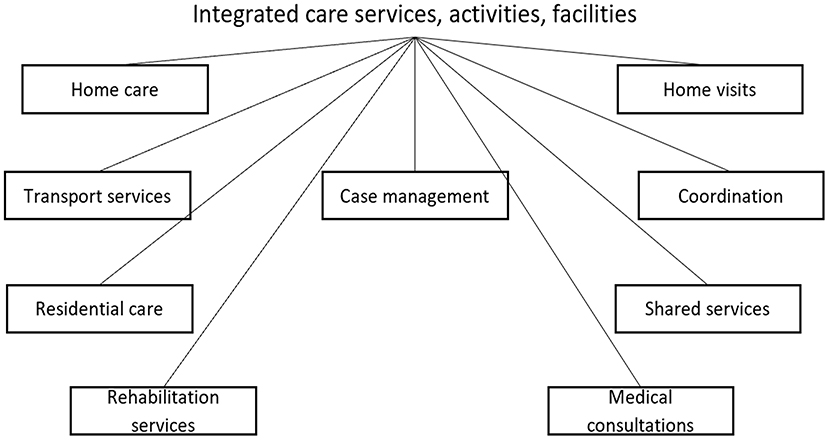

Based on the literature review, integrated care services, activities and facilities related to social care needs for seniors were identified as key factors that helped guide the review process and data synthesis (Figure 1 below).

A content analysis of extracted data from the findings sections of included papers was undertaken, informed by the following attributes of care, program and population characteristics:

• Integrated care services, activities, facilities as outlined above in Figure 1.

• Demographic features (population, geographic dispersal, distance to higher levels of care)

• Governance and coordination (ownership of components, coordinating governance, political positioning (local/provincial/national)

• Funding models

• Emergence (how it came to be a toolkit)

• Cost effectiveness

• Small population

• User outcomes

• Evaluation–program and user satisfaction

Data quality

A critical appraisal of each of the included studies was performed using the CEBM Critical Appraisal of a Case Study tool (Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, 2021). Elements of the appraisal tool related to study description were generally responded to well in the CEBM Critical Appraisal tool. However, responses to questions related to researcher positionality, data collection and analysis, and findings were less clear.

Results

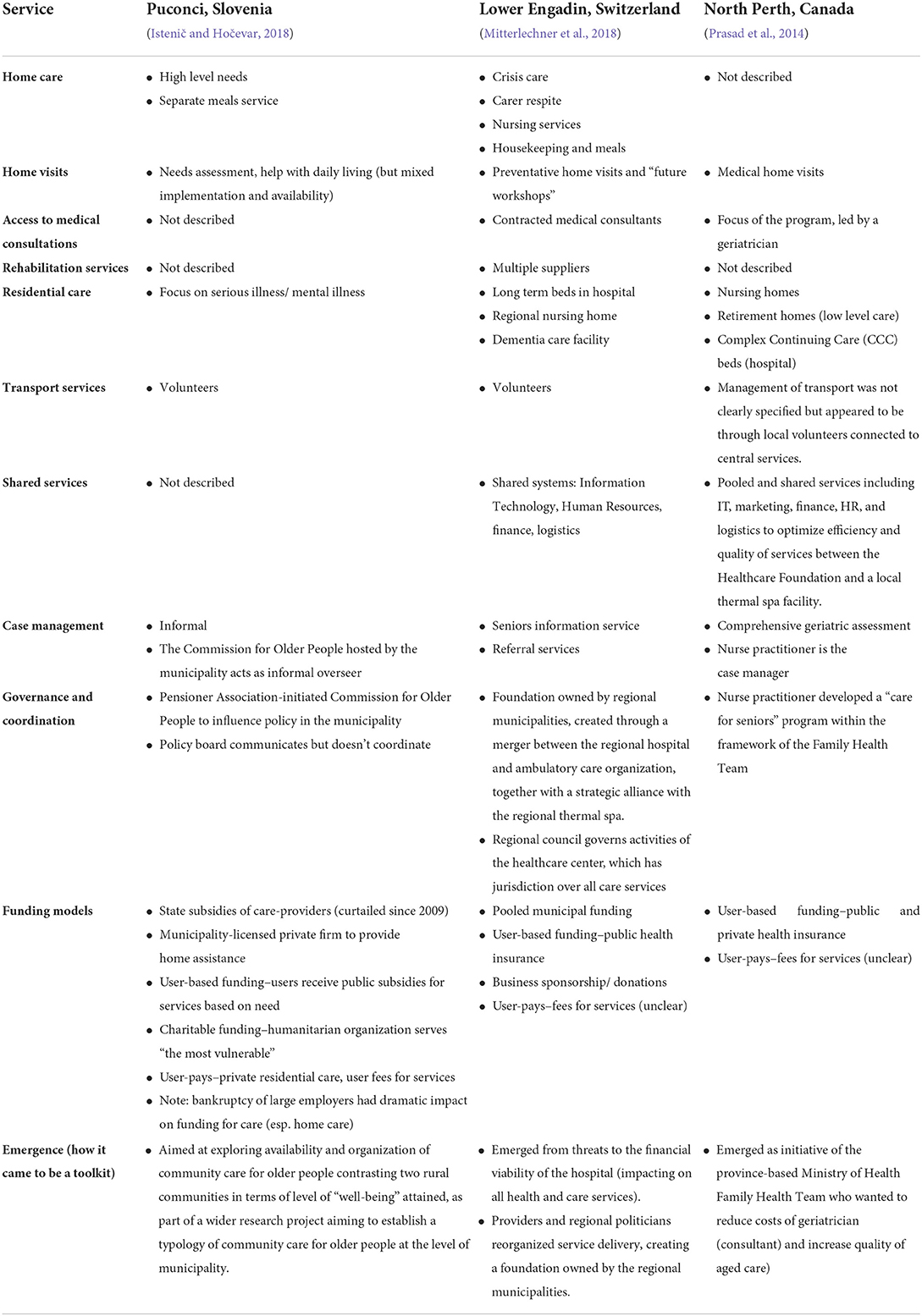

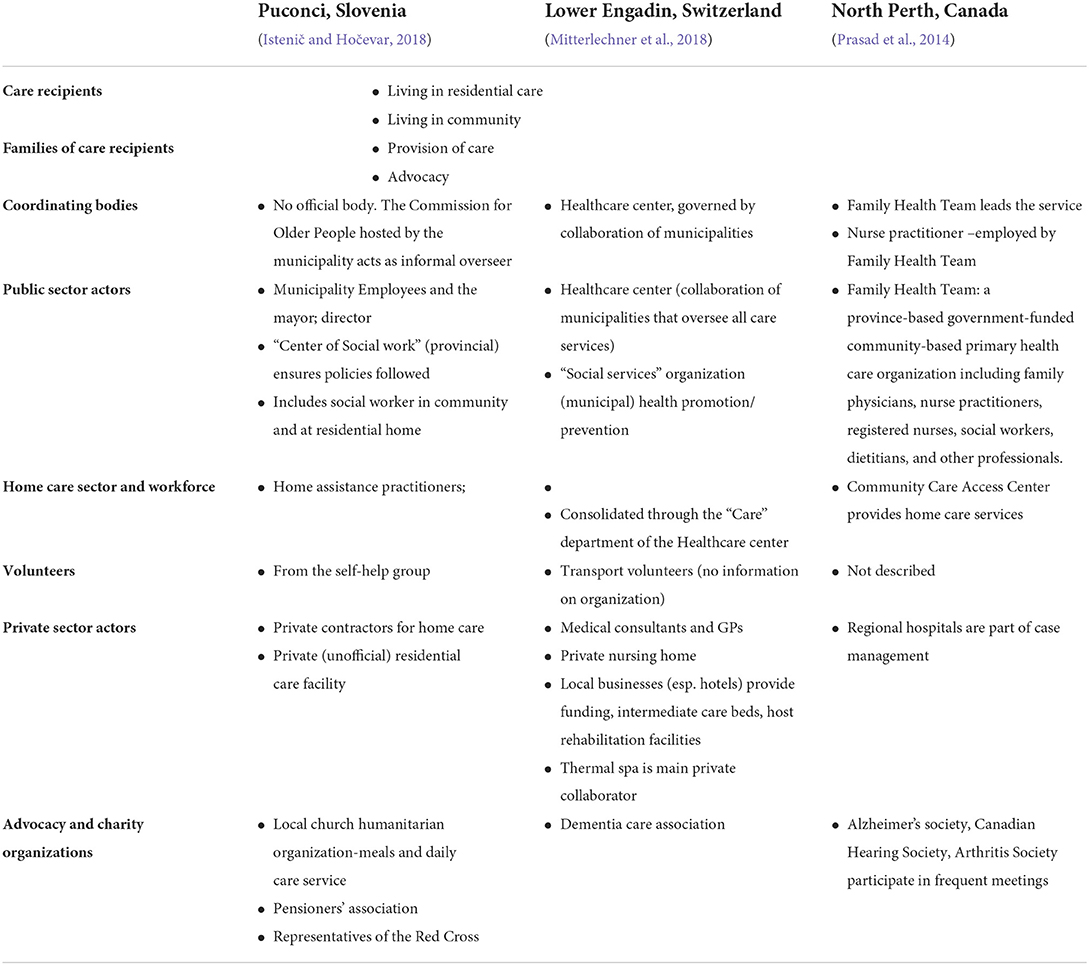

The three included papers were all studies of integrated models of care for seniors in rural settings of high-income countries: Puconci, Slovenia (Istenič and Hočevar, 2018), Lower Engadin, Switzerland (Mitterlechner et al., 2018) (not solely but with a strong focus on aged care) and North Perth, Canada (Prasad et al., 2014). Each of the studies focused on different aspects related to issues of rural aging models of care. The Slovenian study (hereafter “Puconci”) examined the organization and quality of community care for older people in small rural communities. The Swiss study (“Lower Engadin”) explored leadership and governance questions in collaboration with integrated health and social care networks. The Canadian study (“North Perth”) described the implementation of a model of care aiming to improve care coordination and integration for seniors, and provide preliminary evidence of effective use of specialist resources and acute care services. Study and demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Components of an integrated system of social care for seniors in rural settings are identified and mapped across the studies in Table 2. Our findings highlighted the importance (and diversity) of collaborations and partnerships: these are outlined in Table 3. We then evaluate findings in the context of evidence-based principles of care, and explore the complex realities of care. These findings are used to identify an interconnected toolkit of activities to describe the components of care for aged peoples in rural settings.

The review describes much variation between countries in how care for older people was organized. However, there was also variation within country. For example, the Puconci study's results revealed different responses to introduced standards when organizing formal social care on the ground across municipalities in Slovenia. This fieldwork found each local community contextualized the typology of care for their own setting, and the research provided evidence of system responses that the typology itself could not capture (Istenič and Hočevar, 2018).

Components of the included studies are described below and mapped against the associated attributes of care (Table 2).

Stakeholders and sectors

All three case studies described a wide range of stakeholders: spanning clinical to community services, private and public sectors, religious bodies to advocacy groups, as well as consumers (Table 3 below), in turn mediated and shaped by cultural, social and political forces. There were champions described who “made things happen.” In Puconci, the municipality had “an ear for older locals.” Its Commission for Older People provided a local voice through enabling management of regular changes in service providers and provincial policy. Local actors (Pensioners' Associations, humanitarian organization) were in regular contact with distant actors (Center for Social Work, medical care providers), with strong leadership by the Pensioners' Association. However, local providers (e.g., local volunteers, pensioners' associations, and charity organizations), while central to the delivery of care, were not always officially acknowledged. The family remained an important informal care provider for older people in Puconci (Istenič and Hočevar, 2018).

Lower Engadin had leadership by the municipality, supported by commercial entities such as the tourism sector, upon which the region was economically dependent. There were clear ambitions about collaboration with the private sector (especially tourism) for new revenue streams to support the range of services and target populations. There was an acknowledgment that their' small steps' approach to development required bringing actors along.

In North Perth, the geriatric-trained nurse practitioner had responsibility for coordinating care and was a key champion of the initiative. The primary care facility was a key partner. The clear goals and “Program Logic Model” of the Family Health Team guided the nurse practitioner-led model, providing leadership and directing scope.

Evaluation and evidence-based principles of care

Our review found an emphasis on effective responses being driven by community needs and drivers. Communities made heterogeneous adjustments to the processes of population aging according to local context.

System-level solutions supported implementation, governance and efficiencies. Effective information systems were described as critical to successful strategies, with Lower Engadin calling for further development of its population health system, facilitated by a data warehouse; and North Perth referring to the electronic medical record system underpinning effective integration and access. Improved information systems also support evaluative processes that can better inform the evidence base.

Evidence was determined by data availability and depth of analysis: the nature and depth of evaluation of user and provider perspectives as well as outcomes varied between the studies. All studies called for better data management systems to support more robust longitudinal and comparative research and evaluation. Of the three studies, the North Perth review provided the most detailed systematic evidence of improvements in care from its intervention.

The scope of the Puconci study was to explore the organization and quality of community care for older people in small rural communities: there was no formal intervention or evaluation. In describing its typology, the authors acknowledged this was based on and limited by officially obtained and accessible data (Istenič and Hočevar, 2018). Users had regular visits from service leaders, Center for Social Work and municipality to assess needs and satisfaction. These informal assessments found that “recipients are more or less satisfied” but would have more care if it were available/affordable. There was no information on health outcomes. Providers described varying levels of cooperation and collaboration. There was no information on financial sustainability and effectiveness of the initiative.

There were high patient satisfaction rates indicated by users in the Lower Engadin municipality in response to the introduced strategies. Measured outcomes included the average length of stay in the regional hospital, which decreased by 10% over an 8 year period. Providers reported a reduction in operating losses associated with an enhanced shared infrastructure, and the increased range of services introduced over time linked to strengthened collaborations and cooperation (for instance sharing staff) (Mitterlechner et al., 2018).

The North Perth study assessed the number of new geriatrician referrals and follow-up visits before and after the launch of the Care for Seniors program, number of Nurse Practitioner visits in a primary care setting, in-home, retirement home and hospital, number of discharges home from hospital and length of hospital stays. It reported decreased lengths of stay in its Complex Continuing Care beds, and an increased discharge rates returning home (rather to the residential facility). Specialist services were resourced more effectively, with efficiencies in the use of geriatrician time due to improved case management allocation to nurse practitioner and administrative efficiencies. However, the anticipated outcomes of the Program Logic Model had not been confirmed with empirical evidence.

Challenges: The complex realities of care

Challenges to optimal care were described by all case studies, and can be broadly categorized into (interconnected) fiscal, structural and social determinants.

Economic factors impacted availability and choice-making for older people in all three studies. Financial constraints limited access to both home and institutional formal care services. There were many people in need who could not afford institutional care in the Puconci case study. The loss of pension income when an older family member moved to residential care acted as a disincentive to moving from the home setting. Where there was a fee-for-service, people without financial capacity had to rely on charitable funding or municipal subsidies (Istenič and Hočevar, 2018). The increasing number of users in North Perth resulted in a program that was becoming “too successful,” pointing to the need for a different funding structure.

The complex realities of caring needed to better consider the heterogeneous contexts of older people in Puconci rural communities (Istenič and Hočevar, 2018). There was a lack of social power that was considered to limit access to the same level of quality care services as provided in other settings. These authors argued that, while small rural communities were creative and invested heavily in meeting the needs of their older people, their efforts and initiatives were frequently overlooked at a state level. There were parallels in Lower Engadin: while its model of care had political support, its localized structure and innovation differentiated it from other more traditional models, and national policy changes persisted as a potential threat.

Workforce issues and skill capacities impacted on all studies. The policy demand for “qualified” staff was not well suited to the local labor situation in Puconci. Lower Engadin described challenges of its small population base with a complex range of needs against a backdrop of high seasonal demand for services and associated workforce requirements during the tourist season, which continued to impact on service availability. The success of the North Perth model was particularly linked to its champion–a hard to replace Nurse Practitioner in an area where there were limited geriatric trained nurses.

The cooperation and collaboration described as pivotal to the initiatives were not always present. In particular, where public and private actors were “non-local,” they often connected poorly with one another (Istenič and Hočevar, 2018). Maintaining communication between multiple actors was an ongoing challenge in North Perth.

A belief that home assistance may be considered as shameful was prevalent among the first community in the Slovenian case study (Istenič and Hočevar, 2018), inhibiting uptake of the services.

A conceptual toolkit for rural aged care

Based on the findings of our scoping review, an interconnected toolkit of activities was identified to describe the components of care for aged peoples in rural settings. This Toolkit is a collection of interacting and integrated care facilities, programs and services targeted at seniors and coordinated across stakeholders and sectors. It incorporates a systems-based approach to elder care that aims to reduce costs while increasing user and provider satisfaction compared to siloed services. Components of the Toolkit include:

• prevention and screening (essential for understanding patterns of demand)

• home-based care (trend toward increased focus and improved access)

• community-based services (usually provided by third parties)

• residential services (offering various levels of care)

• emergency care management (transitions to acute care)

• rehabilitation (transitions from acute care, and transitions to home-based care)

• support for informal carers (enhanced support and capacity-building)

• information systems and services (integrated across systems)

Underpinning this Toolkit is a move away from a dualistic perspective on rural aging services, with aging addressed as a complex, interconnected social issue rather than solely a health problem (Istenič and Hočevar, 2018; Kneis and Baker, 2020).

Discussion

The three case studies in our review detail various strategies that aimed to promote optimal multifaceted, multisectoral, partnership/collaborative models of social care in rural settings for older people. While each of the studies varied in focus, there were key principles that crucially underpinned the models related to collaboration, cooperation and innovation.

All three studies described leadership and enterprise to drive change, and in each case it was a recognition of the inability of existing models of care to ease the ongoing resource crisis or to cope with compounding crises such as the economic shock of business closures in the Slovenian case or a change in health system management in Switzerland. For the North Perth study, the change agents included a Nurse Practitioner champion who was the “glue” for the various strategies (Prasad et al., 2014). Lower Engadin had a committed management team. In the two Puconci case studies, community actors (including self-organized representative/advocacy groups) were described as central to any effective program.

Notably, the roles of other actors in the complex matrix of care included players outside the traditional concept of aged care in acute and primary care settings. The crucial importance of informal actors (such as family care-givers) was emphasized. Non-elder-specific facilities that influenced service availability and function according to location and context included such novel players as hotels and leisure facilities in Lower Egadin. Municipal and other government actors were also seen as key, even when “the system” extended beyond their legal requirements.

While more research is required, the studies described the economic benefits of collaborative systems of care: it was cheaper to run than siloed care. While the advocated changes did not necessarily solve funding problems, they were described as helping facilitate better use of regional resources (for instance, through innovative pooling, sharing functions and sharing staff).

The interconnectivity of sectors was seen as central to any successful initiative. For example, while primary care remained at the center of organization, it was the connections between community care and primary care that were seen to make systems work in the Lower Engadine study. Better linkages between primary and specialist care were seen to improve care of older adults while promoting more efficient use of resources in the North Perth study. The positioning within and collaboration between formal and informal providers was described as supporting an increasing acceptance of the local practices of care in the Puconci setting.

Therefore, to ensure the effectiveness of public policy responses to aging and the finding of appropriate solutions for both urban and rural communities of different sizes, it is necessary to examine the needs of aging people of different communities, as is regularly emphasized in the literature. Central to this process is to also to explore the reasons that policy makers do not incorporate strengthened partnerships that acknowledge of the diverse social contexts assets, and potentials of these communities (Istenič and Hočevar, 2018), and in turn may better support meaningful context-driven responses to improve the potential for healthy aging.

Regional approaches (collaborations between multiple municipalities or health services in different “regions”) underpinned the models described here and highlighted the importance of context-driven strategies that responded to individual community needs: there are no “one-size-fits-all” solutions.

Implementation of strategies requires leadership, long term planning, political will and buy-in, context-driven responses, effective change management, and the ability to take “small steps” in addressing the ongoing resource crisis in aged care and preparing care systems that can cope well with compounding crises.

Strengths and limitations

The small number of studies examined in this review reflects the paucity of case study literature on the integration of social and health services for older people in rural communities. The Puconci and Lower Engadin studies in particular were limited by a lack of empirical evidence. However, the findings from our review provide valuable insights to help guide policy and planning strategies for improved care. There is a clear need for stronger evidence to guide strategies and policy, including evaluation of cost effectiveness, program and user satisfaction and user outcomes.

Conclusion

Effective models of social care for rural-dwelling seniors demands a series of appropriately funded, coordinated system-based responses that considers the complex and heterogeneous contexts (and needs) of communities. Such models are underpinned by leadership and political will, working with a range of stakeholders across family, community and clinical domains in private and public sectors. They require context-driven mapping against a framework of integrated facilities, programs and services for prevention and rehabilitation, home-based care, community-based care, residential care and emergency care. A systems-based approach to elder care is incorporated that is cost effective while increasing user and provider satisfaction compared to siloed services. Finally, the cases illustrate two key points that relate to the topic of this collection–firstly that effective change can be instigated and implemented (and hopefully sustained) through local action, and secondly that change can be implemented in a “continuing crisis” context, rather than needing to be put “on hold” until the crisis eases.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

GV: conceptualization, methodology, data analysis, writing of original draft, and editing and article preparation. DC: conceptualization, methodology, data analysis, writing, and editing and critical revisions for intellectual content. RP, WM, and A-MH: data analysis, and writing and critical revisions for intellectual content. All authors accept responsibility for the paper as published.

Funding

This research was supported by the Municipality of Storuman, Sweden. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.885636/full#supplementary-material

References

Andersson Bäck, M., and Calltorp, J. (2015). The Norrtaelje model: a unique model for integrated health and social care in Sweden. Int. J. Integr. Care. 15, e016. doi: 10.5334/ijic.2244

Arksey, H., and O'malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Aspinal, F., Glasby, J., Rostgaard, T., Tuntland, H., and Westendorp, R. G. J. (2016). New horizons: reablement-supporting older people towards independence. Age Ageing. 45, 574–578. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw094

Asthana, S., and Halliday, J. (2004). What can rural agencies do to address the additional costs of rural services? A typology of rural service innovation. Health Soc. Care Community. 12, 457–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00518.x

Australian Government. (2020). Review of Innovative Models of Aged Care. Research Paper 3. Canberra Australia: The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety.

Auvinen, A.-M., Silén, R., Groop, J., and Lillrank, P. (2011). “Defining service elements in home care.” in Proceedings-2011 Annual SRII Global Conference. San Jose, CA, 378–383. doi: 10.1109/SRII.2011.50

Brodaty, H., Thomson, C., Thompson, C., and Fine, M. (2005). Why caregivers of people with dementia and memory loss don't use services. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 20, 537–546. doi: 10.1002/gps.1322

Calvó-Perxas, L., Vilalta-Franch, J., Litwin, H., Turró-Garriga, O., Mira, P., and Garre-Olmo, J. (2018). What seems to matter in public policy and the health of informal caregivers? A cross-sectional study in 12 European countries. PLoS ONE. 13, e0194232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194232

Cochrane Training. (2021). 1.1 Why do a systematic review?. Cochrane. Available online at: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-01 (accessed June 2022).

Daudt, H. M., Van Mossel, C., and Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team's experience with Arksey and O'Malley's framework. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13, 48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

Davies, K., Dalgarno, E., Angel, C., Davies, S., Hughes, J., Chester, H., et al. (2020). Home-care providers as collaborators in commissioning arrangements for older people. Health Soc. Care Commun. 30, 644–655. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13169

de Souza Alves, L., Qirino Monteiro, D., Ricarte Bento, S., Hayashi, V., De Carvalho Pelegrini, L., and Carvalho Vale, F. (2019). Burnout syndrom in informal caregivers of older adults with dementia: a systematic review. Dement. Neuropsychol. 13, 415–421. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642018dn13-040008

Doh, D., Smith, R., and Gevers, P. (2020). Reviewing the reablement approach to caring for older people. Aging Soc. 40, 1371–1383. doi: 10.1017/s0144686x18001770

Falk, H., Wijk, H., Persson, L. O., and Falk, K. (2013). A sense of home in residential care. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 27, 999–1009. doi: 10.1111/scs.12011

Fournier, N. B., and Lassen, A. J. (2021). Reattached: emerging relationships and subjectivities when engaging frail older people as volunteer language teachers in Denmark. Ageing Soc. 41, 1163–1183. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X19001648

Gaspar, H. A., Oliveira, C. F. D., Jacober, F. C., Deus, E. R. D., and Canuto, F. (2020). Home Care as a safe alternative during the COVID-19 crisis. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira. 66, 1482–1486. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.66.11.1482

Giraudeau, C., and Bailly, N. (2019). Intergenerational programs: What can school-age children and older people expect from them? A systematic review. Eur. J. Ageing. 16, 363–376. doi: 10.1007/s10433-018-00497-4

Henning-Smith, C. (2020). The unique impact of COVID-19 on older adults in rural areas. J. Aging Soc. Policy. 32, 396–402. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1770036

Istenič, M. C., and Hočevar, D. K. (2018). The organisation of care for older people in rural communities: two case studies from Slovenia. Sociální studia / Social Studies. 15, 65–81. doi: 10.5817/SOC2018-1-65

Jasper, R., Hughes, J., Roberts, A., Chester, H., Davies, S., and Challis, D. (2019). Commissioning Home care for older people: Scoping the evidence. J. Long Term Care. 2019, 176–193. doi: 10.31389/jltc.9

Kneis, P., and Baker, K. (2020). “Understanding the dimensions of aging and old age in rural areas.” in: The Routledge handbook of comparative rural policy. 1 ed. Eds, M. Vittuari, J. Devlin, M. Pagani, and T. G. Johnson (Milton: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9780429489075-15

Kok, L., Berden, C., and Sadiraj, K. (2015). Costs and benefits of home care for the elderly versus residential care: a comparison using propensity scores. Eur. J. Health Econ. 16, 119–131. doi: 10.1007/s10198-013-0557-1

Larsson, A., Karlqvist, L., Westerberg, M., and Gard, G. (2013). Perceptions of health and risk management among home care workers in Sweden. Phys. Ther. Rev. 18, 336–343. doi: 10.1179/108331913X13746741513153

Lindquist, L. A., Ramirez-Zohfeld, V., Forcucci, C., Sunkara, P., and Cameron, K. A. (2018). Overcoming reluctance to accept home-based support from an older adult perspective. J. Am. Geriatr Soc. 66, 1796–1799. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15526

Luker, J. A., Worley, A., Stanley, M., Uy, J., Watt, A. M., and Hillier, S. L. (2019). The evidence for services to avoid or delay residential aged care admission: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 19, 217. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1210-3

Mah, J. C., Stevens, S. J., Keefe, J. M., Rockwood, K., and Andrew, M. K. (2021). Social factors influencing utilization of home care in community-dwelling older adults: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 21:145. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02069-1

Mitterlechner, M., Hollfelder, C., and Koppenberg, J. (2018). Preserving care delivery in hard-to-serve regions: A case study of a population health system in the swiss lower engadin. Int. J. Integrat. Care. 8, 1–12. doi: 10.5334/ijic.3353

Nelson, R. (2019). Trends in home care-the coming resource crisis. Am. J. Nurs. 119, 16–17. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000605312.38403.04

NHS. (2022). National Framework for NHS Continuing Healthcare and NHS funded Nursing Care National Health Service, UK. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1087562/National-Framework-for-NHS-Continuing-Healthcare-and-NHS-funded-Nursing-Care-July-2022-revised.pdf

Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. (2021). Critical Appraisal tools. Oxford University. Available online at: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/ebm-tools/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed June 2022).

Ohta, R., Ryu, Y., Kitayuguchi, J., Gomi, T., and Katsube, T. (2020). Challenges and solutions in the continuity of home care for rural older people: a thematic analysis. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 39, 126–139. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2020.1739185

Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., et al. (2021). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation. 19, 3–10. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000277

Prasad, S., Dunn, W., Hillier, L. M., Mcainey, C. A., Warren, R., and Rutherford, P. (2014). Rural geriatric glue: a nurse practitioner-led model of care for enhancing primary care for frail older adults within an ecosystem approach. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 62, 1772–1780. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12982

Sandsdalen, T., Grøndahl, V. A., Hov, R., Høye, S., Rystedt, I., and Wilde-Larsson, B. (2016). Patients' perceptions of palliative care quality in hospice inpatient care, hospice day care, palliative units in nursing homes, and home care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat. Care. 15:79. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0152-1

Scharf, T., Walsh, K., and O'shea, E. (2016). “Ageing in rural places.” In: Routledge International Handbook of Rural Studies, Eds Shucksmith, M., and Brown, D. L., (New York: Routledge).

Schmidt, E., Schalk, J., Ridder, M., van der Pas, S., Groeneveld, S., and Bussemaker, J. (2022). Collaboration to combat COVID-19: policy responses and best practices in local integrated care settings. J. Health Organ. Manag. 36, 577–589. doi: 10.1108/jhom-03-2021-0102

Scott, A., Witt, J., Humphreys, J., Joyce, C., Kalb, G. R. J., Jeon, S. -H., et al. (2012). Getting Doctors into the Bush: General Practitioners' Preferences for Rural Location (1556–5068). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2126895

The Storuman Cares Project Team. (2021). Storuman Cares 2050 Project. Available online at: https://www.storuman.se/contentassets/bcb77afbdd3643a6b19379bb3252b9a1/storumancaresoptionspaperproposal.pdf (accessed June 2022).

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., et al. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

Vanleerberghe, P., De Witte, N., Claes, C., Schalock, R. L., and Vert,é, D. (2017). The quality of life of older people aging in place: a literature review. Qual. Life Res. 26, 2899–2907. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1651-0

Wilde, A., and Glendinning, C. (2012). ‘If they're helping me then how can I be independent?' The perceptions and experience of users of home-care re-ablement services. Health Soc. Care Community. 20, 583–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01072.x

World Bank. (2022). World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Geneva: World Bank. Available online at: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed September 2022).

Keywords: social care and housing, rural health, healthy aging, models of integrated care, home care, community health

Citation: Vaughan G, Carson DB, Preston R, Mude W and Holt A-M (2022) A “toolkit” for rural aged care? Global insights from a scoping review. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:885636. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.885636

Received: 28 February 2022; Accepted: 12 September 2022;

Published: 17 October 2022.

Edited by:

Andreas Koch, University of Salzburg, AustriaReviewed by:

Matthew Carroll, Monash University, AustraliaLuminita-Anda Mandache, University of Salzburg, Austria

Copyright © 2022 Vaughan, Carson, Preston, Mude and Holt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dean B. Carson, ZGVhbi5jYXJzb25AdW11LnNl

†These authors share first authorship

‡ORCID: Geraldine Vaughan orcid.org/0000-0002-0132-9946

Dean B. Carson orcid.org/0000-0001-8143-123X

Robyn Preston orcid.org/0000-0003-4700-1521

William Mude orcid.org/0000-0003-1961-5681

Anne-Marie Holt orcid.org/0000-0001-8063-6874

Geraldine Vaughan

Geraldine Vaughan Dean B. Carson2*†‡

Dean B. Carson2*†‡ Robyn Preston

Robyn Preston William Mude

William Mude