94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 22 June 2022

Sec. Politics of Technology

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.885362

This article is part of the Research Topic The Politics of Digital Media View all 6 articles

The current military conflict between Russia and Ukraine is accompanied by disinformation and propaganda within the digital ecosystem of social media platforms and online news sources. One month prior to the conflict's February 2022 start, a Special Report by the U.S. Department of State had already highlighted concern about the extent to which Kremlin-funded media were feeding the online disinformation and propaganda ecosystem. Here we address a closely related issue: how Russian information sources feed into online extremist communities. Specifically, we present a preliminary study of how the sector of the online ecosystem involving extremist communities interconnects within and across social media platforms, and how it connects into such official information sources. Our focus here is on Russian domains, European Nationalists, and American White Supremacists. Though necessarily very limited in scope, our study goes beyond many existing works that focus on Twitter, by instead considering platforms such as VKontakte, Telegram, and Gab. Our findings can help shed light on the scope and impact of state-sponsored foreign influence operations. Our study also highlights the need to develop a detailed map of the full multi-platform ecosystem in order to better inform discussions aimed at countering violent extremism.

The current conflict initiated by Russia against Ukraine in February 2022 is accompanied online by heightened activity involving official Russian information sources and social media platforms. This activity includes attempts to drown out narratives on Facebook and even physical restriction of Internet access (Tidy and Clayton, 2022). There has also been dismay expressed at Facebook, the largest social media platform, for its apparent inability to label Russia propaganda about Ukraine (Center for Countering Digital Hate, 2022). This finding by the Center for Countering Digital Hate, a U.S. non-profit that researches online hate and misinformation, follows from their finding that articles concerning Ukraine that were written by English-language media outlets owned by the Russian state, have received over 500,000 likes, comments and shares from Facebook users in the year prior to the Russian conflict starting February 2022.

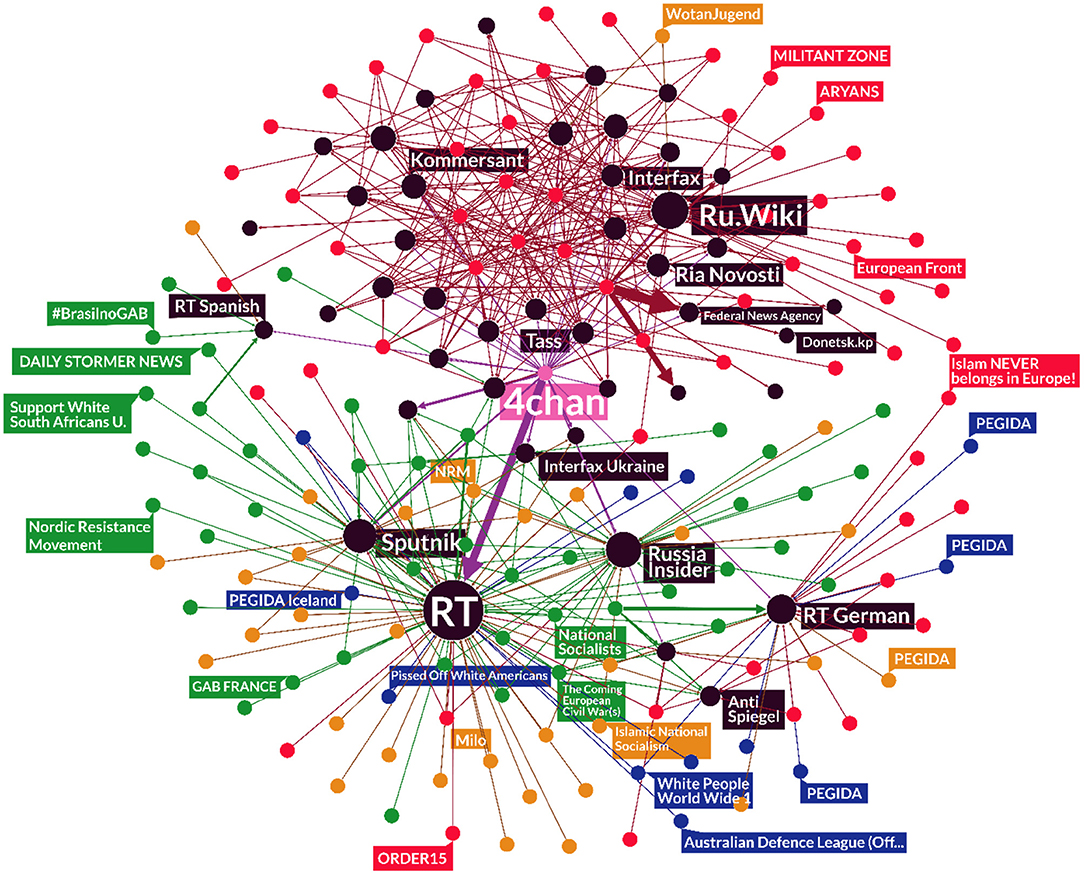

One of the obstacles in assessing how the online disinformation and propaganda war is evolving, is the lack of understanding of how the social media universe comprising many interconnected communities across multiple platforms, interacts with Russian information sources. This paper takes a preliminary step to improve this understanding with respect to Russian information sources and online extremist communities–in particular, European Nationalists and American White Supremacists–across five highly active social media platforms: Facebook, VKontakte, Telegram, Gab, and 4chan. The relationship between Russian information sources (official media) and extremists online was raised by the U.S. State Department report as being of particular concern and urgency (U. S. State Department, 2022). Our resultant mapping of this ecosystem (Figure 1) is necessarily incomplete and imperfect, like any first map, and constitutes just a piece of the full ecosystem that will surely later be extensively modified and expanded. However, it provides a concrete starting point which can then be easily improved with higher frequency updating and deeper content analysis. It also seems reasonable to claim that any meaningful discussion of online disinformation and propaganda during the current Russia-Ukraine crisis, can benefit from the knowledge contained in this map–and of course, more detailed future versions.

Figure 1. Network map (directed graph) showing links from hate clusters (each hate cluster is a node) across multiple social networking sites into Russian domains. Colored nodes represent a known hate-based cluster on one of five different social networking sites —Facebook (blue nodes), VKontakte (red nodes), Gab (green nodes), 4chan (pink node), and Telegram (brown nodes)—that self-organized around a variety of different hateful narratives. The dark nodes represent a Russian domain such as Tass, the Russian Federal News Agency, or Russia Today. The correspondingly colored labels indicate the name of different noteworthy Russian domains or SNS clusters. Their node size is based on each node's in-degree, i.e., the number of inbound links from an SNS cluster to a Russian domain. Hence larger nodes were linked to more frequently across social networking sites than smaller nodes. The network is plotted in Gephi using the Fruchterman-Reingold Algorithm. This force-directed layout algorithm equates the attractive forces between nodes to the force of a mass on a spring and the repulsive force to an electrical force, and hence establishes nodes' final positions when the system reaches equilibrium (Gephi).

To set out the expected complexity of this online ecosystem, we recall that the overall global social media universe comprises several billion users who operate within and often across multiple social media platforms. Many users profit from the in-built community feature available on most social media platforms. This allows them to easily join and form a community around any particular topic of interest. An example of such an in-built community is a Facebook “Page” or “Group”, or a “Club” on the Russian-based platform VKontakte. While most of these in-built communities focus around benign topics such as parenting, sports, or lifestyle, some communities focus on extreme content of various forms. Depending on the host platform's terms of use and the efficiency of their policing, some extreme communities may not be censored or taken down. All in-built communities also typically discuss items of news that are of interest; hence, they often feature links (URLs) into external news and information websites. Extremist communities are no different. In addition, all in-built communities can feature links into other communities whose content is of interest to them, within the same—and also across different—social media platforms. Again, extremist communities are no different, and typically do this a lot across platforms in order to keep their members away from moderator pressure (Johnson et al., 2019; Velásquez et al., 2021). The net result is a highly complex, interconnected ecosystem of communities within and across platforms, together with links into external information sources of various kinds.

In what follows, we refer to each such online community (e.g., Facebook Page, Telegram Channel) as a “cluster” in order to avoid confusion with platform-specific definitions and network discovery algorithms. Our choice of the word “cluster” is exactly as in previous published work (Johnson et al., 2019; Velásquez et al., 2021). For example, it avoids any possible confusion with the term “community” in network science which has the different meaning of a subnetwork that is inferred from a specific partitioning algorithm and hence is algorithm dependent. Instead, our clusters are all in-built online communities and have a unique online label as their ID. Our study identifies and focuses on the interconnectivity and activity of 734 hate-based clusters that we uncovered (i.e., 734 online communities) across five platforms, from June 2019 through January 2020. The resulting network (a collection of clusters and URLs which represent nodes and edges in a graph) that we obtain of the online ecosystem (Figure 1) remains remarkably similar through today, May 2022. We do not show it updated here because we have not been able to check every single possible node and link over the past year. We also note that our analysis is achieved without drawing on any personally identifiable information. As a by-product of this mapping, our study also offers insights into the fragmented nature of the social media landscape, and the emergence of alternative platforms which are designed around free speech absolutism, and which create new vulnerabilities for state-sponsored propaganda and coordinated inauthentic behavior.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section Background, we provide a background to the importance of assessing foreign influence, focusing on Russia. In Section Mapping the Social Media Communities and the Interconnections, we present our methodology for mapping out the ecosystem. In Section Identifying the Potential Reach of Russian Propaganda, we discuss the potential reach of Russian propaganda. In Section Mapping the Relationships Between Hate Clusters and Russian Propaganda, we provide the map of the multi-platform ecosystem involving hate clusters and their connection into Russian information sources. Section Future Work lays out some of the future work that will be needed to extend and strengthen the preliminary results presented in this first study. Section Conclusion summarizes our conclusions.

One month before the current military conflict started in February 2020, the U.S. State Department published a report “Kremlin-Funded Media: RT and Sputnik's Role in the Russian Disinformation and Propaganda Ecosystem” which highlights the need to better understand how Russian information outlets RT and Sputnik might act as conduits for the Kremlin's disinformation and propaganda operations (U. S. State Department, 2022). Going further back to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the U.S. Intelligence community established that “Russia's state-run propaganda machine,” specifically RT and Sputnik, “contributed to the influence campaign by serving as a platform for Kremlin messaging to Russian and international audiences (Directorate of National Intelligence, 2017, p. iii).” Three key aspects of Russia's influence operations were noted: a team of quasi-governmental trolls that promotes messages while sowing social discord and doubt about other sources of information; a domestic media apparatus; and a media apparatus that directs Kremlin messaging toward foreign audiences.

This highlights the general concern and interest that has been building in government circles and among academics regarding the relationship between Russian information sources (official media) and extremists online (Tidy and Clayton, 2022) which in turn feeds into the explosion of research works on far-right growth online (Sevortian, 2009; Arnold and Romanova, 2013; Polyakova, 2014, 2016; Berlet et al., 2015; Bluth, 2017; Enstad, 2017; Parkin et al., 2017; Fielitz and Thurston, 2019; Karlsen, 2019; Schuurman, 2019; Baele et al., 2020; Butt and Byman, 2020; Gaudette et al., 2020; Rrustemi, 2020; Umland, 2020; Urman and Katz, 2020). For example, Karlsen used a survey of reports from 15 different intelligence agencies across 11 Western countries to conclude that “Russia uses minorities, refugees and extremists to further its divide and rule approach” (Karlsen, 2019). Twitter has been the social media platform of choice in many studies on misinformation and disinformation in relation to Russia. However, there is a lack in study of the broader online ecology and how narratives propagated by extreme communities evolve at the system level across multiple platforms. Present work tends to either focus on single platforms (such as Twitter) or limited case studies (e.g., tracking the content and activity from a few individuals thought to be influential). These approaches can miss the scope of online influence patterns or the degree to which small but active groups can influence the broader network. Our belief, reinforced by the results that we present, is that fully mapping the multi-platform ecology is a key component in understanding the scope and impact of these state-sponsored foreign influence operations. Watts' 2017 testimony before Congress presented a hypothetical example of how a state-sponsored influence operation mutates and evolves across multiple platforms:

“an anonymous forgery placed on 4Chan can be discussed by Kremlin 4 Twitter accounts who then amplify those discussions with social bots. Then, a Russian state sponsored outlet on YouTube reports on the Twitter discussion. The YouTube news story is then pushed into Facebook communities, amplified through ads or promoted amongst bogus groups. Each social media company will see but a part of the Kremlin's efforts. Unless all of the social media companies share their data, no one can fully comprehend the scope of Russia's manipulation and the degree of their impact (Watts, 2017)”.

This form of development across multiple social platforms was noted by the Rand Corporation as serving to strengthen the narrative within each individual platform by adding apparent legitimacy, as well as ultimately creating a web that becomes almost impossible to disentangle [Mazarr et al., 2019, p. 90].

We now discuss the importance of including the smaller social media platforms 4chan, Gab and Telegram, in addition to Facebook and VKontakte for which there is now a significant body of research into hate speech, violent extremism, and influence operations. Facebook is well known and the largest of all social networking services (SNS). VKontakte is also popular and is based within the Russian Federation. It is Europe's most popular SNS and is Russia's most prominent by far. Though it has 100 million users overall, only half come from the Russian Federation. Most of the other half come from areas throughout the former Soviet Republics as well as China and Western Europe. There are about 5% in China and Germany. VKontakte was banned in Ukraine in 2017 in an attempt to stem Russian disinformation, yet it persisted as the country's 4th most popular site. The smaller platforms 4chan, Gab and Telegram add to this mix, with their users' many links to each other and to the larger platforms helping to entangle the ecosystem more tightly (Johnson et al., 2019; Velásquez et al., 2021). Moreover, they tend to be more lenient toward hate speech and conspiracy theories (McLaughlin, 2019). Gab promotes itself as a free speech alternative to Twitter and has additional technical features that allows its users to form interest-based groups. Gab's policies prohibit content that constitutes terrorist activity, threats, and illegal pornography (Zannettou et al., 2018). The platform 4chan promotes similarly few policies and has the added feature of making posts anonymous (McLaughlin, 2019). Together, the ecosystem of these platforms provides a good candidate for exploring connective action (Bennett and Segerberg, 2012), and more directly for addressing the question of interest in this paper concerning how Russian information sources feed into online extremist communities.

Our methodological approach to building the map of the social media platforms' communities and their interconnections – and classifying their content—is exactly the same as that in Johnson et al., 2019, Velásquez et al. (2021) where it is laid out in detail with examples. Summarizing, it involves identifying clusters that satisfy the criteria that we set, then collecting the links between them. We do this using a mixture of manual analysis combined with machine search algorithms that we have developed. Our approach avoids requiring any individual level information. As in Johnson et al. (2019), Velásquez et al. (2021), we focus in this paper on communities that promote hateful content and we use the same definition of hate as in those earlier papers and as summarized in what follows. We realize that our definitions create a subset of all the extremist communities that could be considered, and that nuanced definitions of hate could be adopted.

In detail, our process begins with us manually identifying a small seed set of clusters that promote hateful content across platforms. This seed set is developed by manually following leads from previously published work (academic and journalistic) that report particular clusters as playing an important role, together with our own experience of particular high-profile clusters. Because of the iterative snowball approach that we then subsequently employ, the precise composition of this seed is not too important because any highly connected (and hence important) clusters that are missed will likely be picked up as the snowballing process is carried out. Of course, future work needs to be carried out to rigorously check this but our experience shows that having manual seeds produced by different subject-matter experts working independently still leads to final many-cluster ecologies that are similar. When building the seed, we search the content of each candidate cluster manually to look for hateful themes, narratives, and symbols. In order to qualify a particular cluster as being hate-based, we look in detail at its name, avatar, photos, and publicly available posts to see if they show racial or ethnic supremacist or fascist ideology. Specifically, if two of the twenty most recent posts or artifacts at the time of review were “encouraging, condoning, justifying, or supporting the commission of a violent act to achieve political, ideological, religious, social, or economic goals” (Hate Crimes), then we included that cluster in our seed set. We based our criteria for racial and ethnic supremacy and fascist ideologies on Michael Mann's description of fascism as “the pursuit of a transcendent and cleansing nation-statism through paramilitarism” to identify a broad set of clusters that ground their hate in extreme nation-state ideology (Mann, 2004, p. 13). This initial seed list of clusters is then fed into software that we developed which interacts with APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) for the various social media platforms, to identify new clusters that are connected to them via URLs. Specifically, if Cluster A shares a post with a link to Cluster B, then Cluster B is included in the new set to be reviewed. We manually review this expanded list using the same criteria as above, to see if they should be classified also as hate-based. We then iterate this snowball-like process a number of times and note that ultimately the new clusters we find often link back to members of the list. In this sense, we can reasonably claim that our process has uncovered many of the most popularly linked-to clusters. Because our procedure relies on URLs from existing clusters to discover new ones, there is a small potential for bias if popular clusters are both (A) not present in our original seed set and (B) rarely linked-to from our collected network of clusters. Due to the tendency for online groups to link to each other frequently, we consider this unlikely to have compromised the integrity of our network.

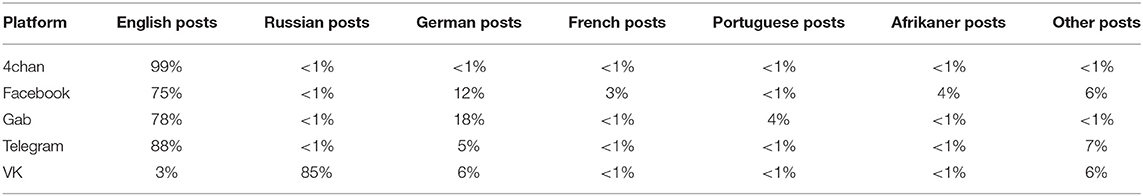

This process produces a network with clusters that express hate—and from now on we refer to them simply as “hate clusters”. We obtain 734 hate clusters that are interconnected across the five platforms. These hate clusters all promote types of violent extremism; hence they can also be referred to as extremist clusters or equivalently extremist communities. They typically show some affiliation with a recognizable hate group, such as the KKK, the Nordic Resistance Movement, and Atomwaffen Division, but there are also those that are unaffiliated or whose affiliation is to some other smaller group that is far less discussed or known (Extremist Files), (Hate on Display: Hate Symbols Database, 2019). Moreover, during the six-month period of study this network of hate clusters produced nearly 20 million posts in many different languages. The hate clusters contain users from many different places across the globe, but the main languages used in the postings and stories suggests that users are from Europe and the United Kingdom, North America, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. The statistics for the language of the posts on the hate clusters within each platform is shown in Table 1. Languages such as Ukrainian, Polish, Serbian, Slovenian, Italian, Danish, and Spanish made up <2% of the total posts on any single platform. We used Google's Compact Language Detector model (freely available) to obtain these estimates of the proportion of different languages used in the posts of the hate clusters on each platform (Ooms, 2018).

Table 1. The main usage of language in the posts within the hate clusters across different social media platforms.

A subset of these 734 hate clusters share links to official Russian information sources such as domains and international affiliates of known Russian state-sponsored propaganda channels including RT and Sputnik. The U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence describes “Russia's state-run propaganda machine” as “its domestic media apparatus, outlets targeting global audiences such as RT and Sputnik, and a network of quasi-governmental trolls” (Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, 2018). It is also well documented that Russia has been supporting far-right entities in Europe and the United States (Klapsis, 2015). To explore the potential online nexus between hate clusters across platforms involving far-right entities and Russian propaganda, we analyzed posts linking to URLs of documented Russian propaganda channels. Then we measured their frequency as a proxy for the likely presence of potential “quasi-governmental trolls.” Working off our total database of nearly 20 million posts, we found links to hundreds of different Russian domains, but many of these URLs were only shared a single time across the entire global online hate network. We assess that “one-off” posts were likely not a sign of a coordinated campaign, so we limited the scope to the 1,500 most shared or linked to domains over the six-month period of the study. We realize that the task of unambiguously identifying coordination is an unsolved problem and that our approach is limited, not unlike many existing approaches in the literature. Nevertheless, it does help shed some light on the potential extent of such coordination.

Doing this, we found the following. Among the top 1,500 most shared domains across our ecosystem, we found 43 unique Russian domains, i.e., URLs ending in a.ru address or links to international affiliates of known Russian domains including RT and Sputnik. Each of these 43 domains had been shared at least 40 times in one or more of our indexed hate clusters. These domains include a battery of mainstream domestic Russian news channels, services, and agencies such as Tass, Ria Novosti, Kommersant, Lenta.ru and Echo Moskvy which can be characterized as Russia's “domestic media apparatus” (Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, 2018). While these are all mainstream, popular channels within Russia, each entity is either owned by the Russian government, or a subsidiary of a larger company like Gazprom that is owned by the Russian government, reflecting broader trends in the Russian media landscape (Russia's Struggle for Press Freedom, 2018; Russia profile - Media, 2021). The list of frequently linked-to Russian domains also includes several international affiliates of RT and Sputnik, which the U.S. government designated as Russian propaganda “outlets targeting global audiences” (Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, 2018). Additionally, one prominent domain was Russia Insider, a far-right English language blog founded and edited by an American living in Russia with ties to a Kremlin-connected Russian oligarch who has allegedly provided financial support to Russian separatists in Eastern Ukraine (Antisemitism pro-Kremlin propaganda, 2018). Aligning with the broader hateful themes and narratives propagating through these networks, Russia Insider has a whole section of its online paper labeled “The Jewish Question,” filled with false stories and conspiracy theories. The list of frequently linked-to Russian domains also includes the Russian language section of Wikipedia, as well as a set of less notable news sites, anti-LGBT+ blogs, blogs about Russian patriotism, and the local government site for “Donetsk, Russia”.

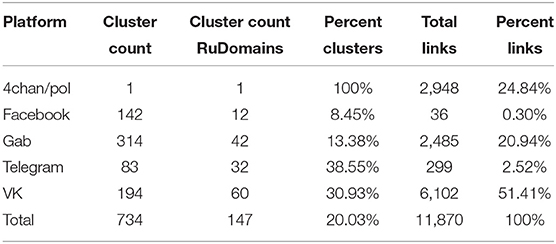

A relatively small portion of clusters linked to these frequently shared Russian domains at any point between June 2019 and January 2020, but a disproportionately large percentage of those links came from 4chan/pol or clusters on Gab. In total, about 20% of hate-based clusters across all platforms linked to one of those 43 Russian domains. When VK, with its predominantly Russian-speaking userbase, is excluded then only approximately 16% of hate-based clusters linked to at least one of those 43 Russian domains at any point during the study. Surprisingly, there were more links to Russian domains from Gab and 4chan/pol combined than from VK, even though <1% of the total posts within clusters on either Gab or 4chan/pol were in Russian.

Table 2 shows the number of individual clusters that we studied and the count of clusters that featured posts linking other followers to frequently shared Russian domains. The “Percent Clusters” column indicates what percentage of total clusters on the studied platform shared links to these Russian domains. The “Total Links” column specifies how many unique links that we found on any given platform to one of the key 43 Russian domains, and the “Percent Links” column shows what portion of the total number links into one of those key Russian domains came from a given platform.

Table 2. The numbers and percentages of hate clusters that featured posts linking other followers to frequently shared Russian domains.

These numbers in Table 2 reveal that links from Gab and 4chan/pol accounted for more than half of all connections from the cross-platform network of hate clusters to the most shared Russian domains. This high rate of links is particularly surprising given the comparatively low rates of Russian language posts on either of these platforms, <1% each across millions of posts, since many of the key Russian domains are Russian-language news sites and blogs. To further investigate the relationships between these racially and ethnically motivated hate clusters and the Russian domains that they link to, we mapped and analyzed how these networks connect across these five social networking platforms.

Our ecosystem network map (Figure 1) is a directed graph showing links from hate clusters across multiple social networking sites into Russian domains. In this network, colored nodes represent a known hate-based cluster on one of five different social networking sites—Facebook, VKontakte, Gab, 4chan, and Telegram— that self-organized around a variety of different hateful narratives. The dark nodes represent a Russian domain such as Tass, the Russian Federal News Agency, or Russia Today. The correspondingly colored labels indicate the name of different noteworthy Russian domains or SNS clusters. Their node size is based on each vertices' in-degree centrality, or the number of inbound links from an SNS cluster to a Russian domain. Therefore, larger nodes were linked to more frequently across social networking sites than smaller nodes for the six-month period of this study. The network's edges are inferred from hyperlinks into.ru domains embedded in cluster's posts. For example, a post in a Gab Group including a URL to an article on RT that directs other members of that cluster to read the article would constitute an edge from that particular Gab group to that Russian domain. This network's edges are weighted, so thicker edges represent more frequent links from one cluster to a given domain. This network map contains 190 unique nodes, 43 of which are Russian domains and 147 of which are hate-based clusters on a social networking site. The network contains 11,870 edges.

The resulting network map in Figure 1 reveals key differences in connective behavior among clusters that post predominantly in Russian on VK and clusters that predominantly post in other languages on Gab, 4chan, Telegram, and Facebook. Russian language clusters on VK tend to link to a larger number of Russian domains at relatively consistent rates because they are interacting with a broader Russophone web ecology in a regular manner, whereas clusters communicating in other languages are consistently linking to a much smaller set of Russian domains at more frequent rates because they are likely engaging with some facet of a state-sponsored influence operation. This network map also illustrates the significant difference in the connective behavior from clusters on less regulated fringe platforms like Gab and 4chan compared to clusters on platforms that have developed policies around hate speech and coordinated inauthentic behavior like Facebook. This heightened degree of connectivity (i.e., the number of links from these platforms, as shown in Table 2) suggests that these platforms' free speech absolutist policies have inadvertently created new and greater vulnerabilities for their users to be exposed to state-sponsored coordinated inauthentic behavior, propaganda, and social manipulation. Compared to a more controlled platform (e.g., Facebook) whose moderation policies take longer to adapt to (Johnson et al., 2019), a coordinated effort from Russian domains could impact users in Gab and 4chan much more quickly. Telegram appears to be an exception to any conclusion that more restriction means fewer links into Russian media. It has a small percentage of links into Russian domains, even though a high percentage of our tracked clusters linked to these domains at some point during the study period. As stated later in the conclusions, more research is clearly needed to tease this out and also to address the additional factors that contribute to the vulnerability of users to social manipulation.

The top-half of the network consists of mostly red clusters, which are groups and pages on VKontakte that densely interconnect to darker clusters representing Russian domains. These domains are mostly mainstream news sources within Russia including Tass, Ria Novosti, Kommersant, Lenta.ru and Echo Moskvy, as well as the Russian language section of Wikipedia. Most of the dark nodes in the top half of the network are about the same diameter because they have similar indegree centralities, meaning that they are referenced at similar rates across social networking sites. This network topology is what we would expect to see from Russian language clusters: namely, clusters posting predominantly in Russian frequently link to a set of Russian domains because those are some of the most commonly available and widely read Russian-language news sources that report on and discuss current events.

In the bottom half of the network, we observe a complex web of hate-based clusters on platforms with relatively few Russian language posts—specifically Gab, 4chan, Facebook, and Telegram—frequently linking to Russian state-sponsored propaganda channels aimed at foreign audiences. RT is the most prominent node in the network because it has the highest in-degree centrality, and 4chan/pol is the most influential node because it has the highest out-degree centrality, meaning it provides the highest rate of links to one of these Russian domains. 4chan/pol is represented as a single node because we treated the /pol board as a single cluster that generates many links to the key Russian domains, especially RT.

Figure 1's map also aligns with the findings in Zannettou et al. (2019) which quantified Russian influence on multiple social networking sites. Those researchers statistically analyzed the presence of commonly shared URLs across several platforms. They found that Russian trolls had a limited influence on larger narratives across different social networks, but that degree of influence was slightly higher on 4chan compared with Twitter and Reddit, and the trolls' impact was highest when trying to drive traffic to RT compared with other news sources (Zannettou et al., 2019, p. 9).

The green Gab clusters and brown Telegram clusters comprise a comparatively high number of nodes, and their positions throughout the network largely align with the language of the RT affiliate that they connect to. In other words, German language clusters on each social networking site aggregate around the RT German node. The red VK clusters connecting to Russian domains in the bottom half of the graph primarily post in German or English and still tend to interact with Russian domains aimed at foreign audiences because they likely contain mostly foreign userbases. While VK is comparatively a mainstream platform to Gab and 4chan, white nationalists from the U.S. and Europe have adapted and migrated to VK due to their relatively low rates of policing and censorship around hate and far-right extremism compared to Facebook (Leahy, 2019).

The clusters sharing Russian state-sponsored propaganda are not bound by any geography, theme, or platform. On Facebook, they include a range of Pegida chapters across Germany, a page called the Australian Defense League promoting anti-Muslim rhetoric, and a page called “Pissed off White Americans”. On Telegram, they include a range of European nationalists, American white supremacists, and a group of Islamists applauding the parallels between religious fundamentalism and national socialism. On Gab, they include exceptionally vitriolic Brexiters, a Daily Stormer fan group, and Brazilian far-right group.

Interestingly, clusters on Facebook are less likely to appear in the network at all compared to clusters on other platforms. The Facebook clusters that do share links to Russian domains tend to be part of PEGIDA, an anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant political movement in Germany that has advocated for improving relations between Germany and Russia and declared their sympathies for Russian president Vladimir Putin (Grabow, 2016). These comparatively low rates could also be attributed to Facebook's recent policy changes around combating hate and extremism, as well as their announced revamped efforts to fight foreign interference ahead of the 2020 U.S. election (Combating Hate Extremism, 2019; Helping to Protect the 2020, 2019).

This work offers a preliminary step toward addressing the significant challenge of understanding the interconnections between Russian information sources and extremist communities across social media platforms. Of course, much work remains to be done. While the network discussed here is extensive, there are many widely-used platforms which are not present: in particular video-sharing sites like YouTube or BitChute. A more complete understanding of the online ecosystem will require additional SNS monitoring.

Telegram looks to be playing a rather unique role that deserves far closer scrutiny than we are able to offer here. It accounted for a relatively small percentage of the total links into key Russian domains in our dataset, yet it exhibited a relatively high percentage of clusters linking into these domains (see Table 2). These facts set it apart from the less-moderated platforms like 4chan and Gab, as well as the more highly moderated one in our dataset: Facebook. Previous work suggests that Telegram's users have a strong ability to direct each other between platforms (Velásquez et al., 2021; Figure 1), and currently it is gaining significant popularity as a communication tool about the Ukraine conflict (Safronova et al., 2022). We leave a more thorough analysis of Telegram's impact for future research.

We also recognize that a broader-reaching dataset could be used to compare the impact factor for other sources. As Table 2 shows, these hate clusters link to many more domains than Russian ones. The frequency of links to U.S.-based or European sources falls outside the scope of the present study but will be an important aspect to measure in future work. Many other generalizations and extensions of what we have done are of course also possible and we hope that this work will at least stimulate efforts in this direction.

Frequent links to Russian propaganda channels would suggest the likely presence of state-sponsored coordinated inauthentic behavior. However, our multi-platform data suggests that such signals appear at relatively low rates on a small subset of clusters. The global online ecology of hate hence remains a largely organic system with many authentic actors, reflecting the persistent real-world presence of hate and violent extremist ideologies. More research is clearly needed to tease this out all the factors that contribute to the vulnerability of users to social manipulation. However, based on the present findings, we can conclude that at the system-level Russian trolls and propaganda channels do not appear to be a dominant, controlling factor in the online ecology of racially and ethnically motivated violent extremists. Putting it crudely, the problem of online hate and violent extremist ideologies is bigger than them.

Nevertheless, what our system-level network maps do show is that the inroads and scope of possible Russian influence operations is comparatively greater on alternative fringe platforms like Gab and 4chan that practice free speech absolutism, as compared to mainstream social networking sites like Facebook that developed and enforced policies around hate speech and coordinated inauthentic behavior. These findings suggest that a fragmented social media landscape among online hate movements, with an increasing number of platforms designed around free speech absolutism, has created new vulnerabilities for state-sponsored social manipulation. These emerging unregulated platforms tend to draw userbases already focused on racially and ethnically hateful content, naturally aligning with Russia's documented techniques of exploiting existing social inequality and discrimination toward minorities and migrants.

The U.S. Intelligence Community's investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election concluded that Russia “will apply lessons learned from its campaign aimed at the US presidential election to future influence efforts in the United States and worldwide (Directorate of National Intelligence, 2017, p. 5).” Monitoring the cross-platform dynamics among multiple online ecologies, including the online ecology of hate as we have attempted to do here, is essential to understanding the scope and impact of these operations during future elections in the U.S. and around the world.

Russia is currently engaging in a conflict with the Ukraine—and indirectly with NATO—in which a large part of the battle is likely being fought online. Such hybrid online-offline aggressions will likely become more commonplace in the coming decades. At the same time, an increasing number of people around the world will come online and have the chance to engage with existing social networking sites as well as creating entirely new platforms with their own set of policies about hate speech, disinformation, and violent extremism—thereby adding complexity to the already messy, shifting online landscape. Our study shows that free speech absolutist platforms have inadvertently created new vulnerabilities to coordinated campaigns promoting state-sponsored propaganda, raising questions around whether heightened susceptibility to state-sponsored manipulation defeats the purpose of committing to free speech. Furthermore, our study shows that more regulated platforms have seemingly made progress in reducing the reach of coordinated inauthentic behavior from state-sponsored trolls spreading propaganda—but they need to take additional measures to combat authentic social coordination around racially and ethnically motivated hate and violent extremism. The persistence of both problems, online hate and susceptibility to foreign influence, challenges policymakers to develop new strategies to handle the offline, real-world root causes of hate and distrust.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

NR was employed by ClustrX LLC.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We are grateful for funding for this research from the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research under award numbers FA9550-20-1-0382 and FA9550-20-1-0383. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Air Force.

Antisemitism and pro-Kremlin propaganda. (2018). EU vs Disinfo. Available online at: https://euvsdisinfo.eu/antisemitism-and-pro-kremlin-propaganda/ (accessed Jan 19, 2018).

Arnold, R., and Romanova, E. (2013). The “White World's Future?” an analysis of the russian far right. J. Study Radicalism. 7, 79–107. doi: 10.1353/jsr.2013.0002

Baele, S., Brace, L., and Coan, T. (2020). Uncovering the far-right online ecosystem: an analytical framework and research agenda. Stud. Confl. Terror. 1–21. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2020.1862895

Bennett, W. L., and Segerberg, A. (2012). The Logic of Connective Action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Inf. Commun. Soc. 15, 739–768. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661

Berlet, C., Christensen, K., Duerr, G., Duval, R. D., Garcia, J. D., Klier, F., et al. (2015). Digital media strategies of the far right in Europe and the United States. Lexington Books, ISBN 978-0-7391-9881-0

Bluth, N. (2017). Fringe Benefits: How a Russian ultranationalist think tank is laying the “intellectual” foundations for a far-right movement. World Policy Journal 34, 87–92. doi: 10.1215/07402775-4373262

Butt, S., and Byman, D. (2020). Right-wing extremism: the Russian connection. Survival. 62, 137–152. doi: 10.1080/00396338.2020.1739960

Center for Countering Digital Hate. (2022). Facebook failing to label 91% of posts containing Russian propaganda about Ukraine. Available online at: https://www.counterhate.com/post/facebook-failing-to-label-91-of-posts-containing-russian-propaganda-about-ukraine (accessed Feb 26, 2022).

Combating Hate and Extremism. (2019). Facebook News. Available online at: https://about.fb.com/news/2019/09/combating-hate-and-extremism/ (accessed Sept 17, 2019).

Directorate of National Intelligence. (2017). Background to Assessing Russian Activities and Intentions in Recent, U. S. Elections: The Analytic Process and Cyber Incident Attribution. Available online at: https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/ICA_2017_01.pdf (accessed December 11, 2021).

Enstad, J. (2017). “Glory to Breivik!”: the russian far right and the 2011 Norway attacks. Terror Political Violence. 29, 773–792. doi: 10.1080/09546553.2015.1008629

Extremist Files. Southern Poverty Law Center. Available online at: https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files

Fielitz, M., and Thurston, N. (2019). Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right: Online Actions and Offline Consequences in Europe and the US. Bielefeld: Trancript Verlag. doi: 10.14361/9783839446706

Gaudette, T., Scrivens, R., and Venkatesh, V. (2020). The role of the internet in facilitating violent extremism: insights from former right-wing extremists. Terror. Political Violence. doi: 10.1080/09546553.2020.1784147

Gephi (2019). https://gephi.org (accessed December 11, 2021).

Grabow, K. (2016). PEGIDA and the Alternative für Deutschland: two sides of the same coin? European View. 15, 173–181. doi: 10.1007/s12290-016-0419-1

Hate Crimes. FBI Website. Available: https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/civil-rights/hate-crimes

Hate on Display: Hate Symbols Database. (2019). Anti-Defamation League. Available online at: https://www.adl.org/hate-symbols (accessed December 11, 2021).

Helping to Protect the 2020. (2019). US Elections. Facebook News. Available online at: https://about.fb.com/news/2019/10/update-on-election-integrity-efforts/ (accessed Oct 21, 2019).

Johnson, N. F., Leahy, R., Johnson Restrepo, N., Velasquez, N., Zheng, M., Manrique, P., et al. (2019). Hidden resilience and adaptive dynamics of the global online hate ecology. Nature. 573, 261–265. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1494-7

Karlsen, G. (2019). Divide and rule: ten lessons about russian political influence activities in Europe. Palgrave Commun. 5, 19. doi: 10.1057/s41599-019-0227-8

Klapsis, A. (2015). An Unholy Alliance: The European Far Right and Putin's Russia. Wilfried Martens Centre. Available online at: https://www.stratcomcoe.org/antonis-klapsis-unholy-alliance-european-far-right-and-putins-russia (accessed May 27, 2015). doi: 10.1007/s12290-015-0359-1

Leahy, R. (2019). The Online Ecology of European Nationalists and American White Supremacists on VKontakte. Connected Life Conference at the Oxford Internet Institute. Available: https://connectedlife.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/82/2019/06/CL-Conference-Programme.pdf (accessed Jun 24, 2019).

Mann, M. (2004). Fascists. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511806568

Mazarr, M. J., Casey, A., Demus, A., Harold, S. W., Matthews, L. J., Beauchamp-Mustafaga, N., et al. (2019). Hostile Social Manipulation: Present Realities and Emerging Trends. Rand Corporation. Available online at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2713.html (accessed December 11, 2021).

McLaughlin, T. (2019). The Weird, Dark History of 8chan and Its Founder Fredrick Brennan. WIRED. Available online at: https://www.wired.com/story/the-weird-dark-history-8chan/ (accessed August 6, 2019).

Ooms, J. (2018). Google's Compact Language Detector 2. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/cld2/cld2.pdf (accessed May 11, 2018).

Parkin, W., Klein, B., Gruenewald, J., Freilich, J., and Chermak, S. (2017). Threats of Violent Islamist and Far-right Extremism: What Does the Research Say? The Conversation. Available online at: https://theconversation.com/threats-of-violent-islamist-and-~far-right-extremism-what-does-the-research-say-72781.

Polyakova, A. (2016). Putinism and the European far right. Institute of Modern Russia. Available online at: https://imrussia.org/en/world/2500-putinism-and-the-european-far-right

Rrustemi, A. (2020). Far-Right Trends in South Eastern Europe: The Influences of Russia, Croatia, Serbia and Albania. Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. (2020). Available online at: https://hcss.nl/report/far-right-trends-in-south-eastern-europe-the-influences-of-russia-croatia-serbia-and-albania/ (accessed December 11, 2021).

Russia profile - Media. (2021). BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-17840134 (accessed June 8, 2021).

Russia's Struggle for Press Freedom (2018). Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. Available online at: https://www.georgetown journalofinternationalaffairs.org/online-edition/2018/4/29/russias-struggle-for- press-freedom (accessed December 11, 2021).

Safronova, V., MacFarquhar, N., and Satariano, A. (2022). Telegram: Where Russians Turn for Uncensored Ukraine News. The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/16/world/europe/russian-propaganda-telegram-ukraine.html (accessed Apr 16, 2022).

Schuurman, B. (2019). Topics in terrorism research: reviewing trends and gaps, 2007-2016. Crit. Stud. Terror. 12, 463–480. doi: 10.1080/17539153.2019.1579777

Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. (2018). Available online at: https://www.intelligence.senate.gov/publications/committee-findings-2017-intelligence-community-assessment (accessed July 3, 2018).

Tidy, J., and Clayton, J. (2022). Ukraine Invasion: Russia Restricts Social Media Access. BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-60533083 (accessed Feb 26, 2022).

Umland, A. (2020). The far right in pre-and post-Euromaidan Ukraine: from ultra-nationalist party politics to ethno-centric uncivil society. Demokratizatsiya. 28, 247–268.

Urman, A., and Katz, S. (2020). What they do in the shadows: examining the far-right networks on Telegram. Inf Commun Soc. 25, 904–923. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2020.1803946

U. S. State Department. (2022). Available online at: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Kremlin-Funded-Media_January_update-19.pdf (accessed Jan, 2022)

Velásquez, N., Leahy, R., Johnson Restrepo, N., Lupu, Y., Sear, R., Gabriel, N., et al. (2021). Online hate network spreads malicious COVID-19 content outside the control of individual social media platforms. Sci. Rep. 11, 11549. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89467-y

Watts, C. (2017). Extremist Content and Russian Disinformation Online: Working with Tech to Find Solutions. Foreign Policy Research Institute. Available online at: https://www.fpri.org/article/2017/10/extremist-content-russian-disinformation-online-working-tech-find-solutions/ (accessed October 31, 2017).

Zannettou, S., Bradlyn, B., De Cristofaro, E., Kwak, H., Sirivianos, M., Stringini, G., et al. (2018). What is Gab: A Bastion of Free Speech or an Alt-Right Echo Chamber? 3rd Cybersafety Workshop (WWW Companion, 2018). France: Lyon. p.1007–1014. doi: 10.1145/3184558.3191531

Zannettou, S., Caulfield, T., Cristofaro, D. e., Sirivianos, E., Stringhini, M., Blackburn, G., et al. (2019). Understanding State-Sponsored Trolls on Twitter and Their Influence on the Web. Available online at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1801,09288.pdf (accessed Mar, 2019). doi: 10.1145/3308560.3316495

Keywords: Russia, extremism, transnational threats, complexity, networks, social media

Citation: Leahy R, Restrepo NJ, Sear R and Johnson NF (2022) Connectivity Between Russian Information Sources and Extremist Communities Across Social Media Platforms. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:885362. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.885362

Received: 28 February 2022; Accepted: 24 May 2022;

Published: 22 June 2022.

Edited by:

Leslie Paul Thiele, University of Florida, United StatesReviewed by:

Lorien Jasny, University of Exeter, United KingdomCopyright © 2022 Leahy, Restrepo, Sear and Johnson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Neil F. Johnson, bmVpbGpvaG5zb25AZ3d1LmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.