94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 20 June 2022

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.873948

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Left Behind: Crisis and Challenges of the Left in Contemporary DemocraciesView all 5 articles

The ideological evolution of Western European social democratic parties has received considerable scholarly attention over the decades. The most widespread view concerns the alleged programmatic moderation and convergence with the mainstream right of this party family. However, recent empirical investigations based on electoral manifestos come to different conclusions, highlighting an increase over time in Western European social democratic parties' emphasis on traditional economic left goals, especially in recent years. Hence, this article analyses the evolution of the social democratic programmatic outlook with regard to traditional economic left issues. It does so by relying on Manifesto Project (MARPOR) data about such formations in 369 general elections across 20 Western European countries between 1944 and 2021, employing different indicators of economic left emphasis and time to ensure the robustness of the findings. The analysis shows how, at the aggregate level, social democracy increases its emphasis on traditional economic left issues over time, with the effect driven entirely by the recent post-Great Recession years. However, once disaggregating the results, a more differentiated picture emerges, pointing towards potential causes of concern in terms of measurement validity within the MARPOR data. The article discusses the substantive and, especially, methodological implications of its findings in detail.

Western European social democracy has moved away from its flagship policy positions over time, catering less and less to its traditional electoral constituency in an attempt to broaden its electoral reach. Upon reading such a statement, few would find it contentious taken at face value. Indeed, much has been written on the ideological moderation and convergence to the centre of these mainstream formations in Western Europe (e.g., Przeworski and Sprague, 1986; Keman and Pennings, 2006; Evans and Tilley, 2013), especially in terms of left-right economic positions and during the years of the “Third Way” (e.g., Giddens, 1998; Adams et al., 2004; Mair et al., 2004; Dalton, 2013). Likewise, the potential motifs of this evolution over time have also been investigated. These include socio-structural drivers such as the progressive shrinking in size of the working class (e.g., Best, 2011); strategic shifts such as the electoral “catch-allisation” (Kirchheimer, 1966) aimed at catering to the expanding and better-off sectors of society (e.g., Kitschelt, 1994; Arndt, 2014; Rennwald and Evans, 2014; Gingrich and Häusermann, 2015; Rennwald, 2020); and the external constraints imposed by their role as almost full-time governing parties (e.g., Mair, 2009). Many identified this programmatic shift as what ultimately caused the end of cleavage politics, that is the electoral misalignment of social democracy's traditional electoral constituency: the working class (e.g., Franklin, 1992; Keman and Pennings, 2006; Evans and Tilley, 2013; Goldberg, 2020).

However, a series of recent empirical contributions have come to surprising conclusions, going in the opposite direction if compared to mainstream accounts. Indeed, some of these analyses show that Western European social democracy has not significantly shifted its economic positions over time (e.g., Adam and Ftergioti, 2019), hence not even during the centrist Third Way phase. Even more remarkably, other such works illustrate how social democratic parties in the region have actually moved further to the economic left over time, by putting greater emphasis on traditional economic left issues (e.g., Emanuele, 2021a). This seems to apply especially in recent years, that is after the global financial crisis now known as the “Great Recession,” which signified the crisis and collapse of the international neoliberal economic model (e.g., Polacko, 2022). The common denominator of these contributions is the data source upon which they rely, the Manifesto Project (MARPOR), which provides information on the salience put by parties on different issues in their electoral manifestos.

With a view to testing these two contradictory viewpoints and settling the debate concerning the effect of time on social democratic economic positions, this article seeks to answer a very straightforward research question: did Western European social democracy increase or decrease the salience it put on traditional economic left issues over time? It does so by performing a detailed time-series cross-section statistical analysis on 369 general elections in 20 Western European countries during a time span of almost 80 years, between the final years of WWII and contemporary days (1944–2021). At the aggregate level, the results seem to go entirely in the direction of the more recent contributions that posit an increase of social democratic emphasis on traditional economic left issues over time, hence contradicting the more numerous mainstream viewpoints. Indeed, the effect of time on social democratic economic left emphasis is positive, statistically significant, and robust to several different operationalisations of both the focal predictor and dependent variable. Moreover, another interesting substantive finding is that this effect is driven entirely by the most recent, post-Great Recession years of the analysed time frame. Were these findings to find further confirmation, they would have important implications as to the several testable mechanisms that could have favoured this leftwards recalibration. These include the urgency of proposing an economic and political model alternative to the hegemonic neoliberalism (e.g., Meyer and Spiegel, 2010); the responsiveness to voters in the region that are progressively more left-wing from an economic viewpoint (e.g., Mair, 2008); and the path-dependency deriving from both previous ideological positions (e.g., Strøm, 1990; Adams et al., 2009) and the key role played in labour-capital bargaining vis-à-vis powerful counterparts such as trade unions (e.g., Garrett, 1998; Hellwig, 2016).

However, a disaggregated look at the results provides a more differentiated and less certain picture. Indeed, on the one hand, there are also issues that become significantly less emphasised over time by social democratic parties. Strikingly, all these MARPOR items concern the defining feature of the economic left: that is, state intervention in the economy (e.g., Downs, 1957, p. 116). On the other, instead, most of the economic left MARPOR items that increase in salience over time are notoriously problematic from a methodological viewpoint: for instance, the categories related to equality and welfare. This adds to the already existing calls for a broader discussion as to the validity of the measurements and results obtained by using MARPOR data. Such a methodological question is especially important when drawing inferences on topics of substantive importance such as the programmatic evolution of Western European social democracy from a longitudinal perspective.

This article will proceed as follows: the next section will introduce the theoretical framework and hypotheses that will guide the empirical analysis, by illustrating the two opposing viewpoints on the relationship between time and social democratic economic left emphasis in detail. The following section will focus on the research design and method of the empirical analysis, before moving on to the illustration of its results. Finally, the article will conclude by providing an exhaustive discussion of the substantive and, especially, methodological implications of its findings.

As one of the main Western European party families and a “core” component (Smith, 1989) of party systems across the continent (Keman, 2017), the ideological profile of social democracy and its evolution over time have attracted considerable scholarly attention. In this regard, the existing scholarly contributions have focused in particular on social democratic positions along the left-right economic issue dimension, and most of them can be divided into two broad camps. On the one hand, several found that, over time, social democratic parties have moved away from traditional economic left stances, progressively favouring a more moderate and economically centrist profile in an ideological convergence with the centre-right. On the other, recent contributions based on MARPOR data come to the opposite conclusion, pointing instead to an increase in social democratic emphasis on traditional economic left issues over time. Both such viewpoints will now be illustrated in greater detail, allowing for the generation of related hypotheses to be employed in this article's empirical analysis.

A widespread view in the literature is that social democracy has moderated its economic stances and converged to the centre with centre-right formations over time, especially during the heyday of the “Third Way” (e.g., Giddens, 1998) during the 1990's (e.g., Keman, 2011). Indeed, several empirical investigations, based on a variety of sources such as expert surveys, data on the socio-economic impact of government policy, and party manifestos, illustrate this rightwards movement to the economic centre (e.g., Mair et al., 2004; Dalton, 2013), most notably epitomised by Tony Blair's “New Labour” in the United Kingdom (e.g., Adams et al., 2004).

The literature identifies several reasons that led social democratic parties to reduce their programmatic differences vis-à-vis their traditional centre-right opponents (e.g., Keman and Pennings, 2006). For a start, there are strategic considerations related to party competition. Indeed, social democracy had to react to decisive changes in the socio-economic composition of Western societies after World War II (WWII), in which increasing material security and wellbeing meant a blurring of traditional social divides. Within this process, whilst the traditional electoral constituency of the left, e.g., the working class, progressively shrunk in size, other segments of societies expanded: in particular, the “new middle classes” made up of highly-educated, white-collar urban professionals (e.g., Best, 2011). Hence, social democratic parties adopted a more “catch-all” profile (e.g., Evans and Tilley, 2012; on catch-all parties, see Kirchheimer, 1966) to maintain their electoral competitiveness despite the reduction in the size of the working class, catering to these expanding new sectors of society by moderating their ideological profile (e.g., Kitschelt, 1994; Arndt, 2014; Rennwald and Evans, 2014; Gingrich and Häusermann, 2015; Rennwald, 2020). As a consequence, this also entailed the progressive alienation of traditional supporters of the left (Karreth et al., 2013; Schwander and Manow, 2017) that not only decreased in number, but also in their support of social democratic parties, signifying a decline of cleavage politics (e.g., Franklin, 1992; Keman and Pennings, 2006; Evans and Tilley, 2017; Goldberg, 2020). Hence, the strategic reduction of social democracy's ideological baggage was driven by vote- and office-seeking incentives (e.g., Strøm, 1990) in a context of changing societal composition and diminished ideological conflict in Western Europe, also favouring its coalition-building potential (Keman, 2011).

Another key set of considerations behind social democracy's programmatic moderation over time is its progressive affirmation as a “core” component of Western European party systems, that translated its electoral competitiveness into the legitimate expectation and status of being a governing party. Indeed, involvement in government within this region entails the embedment into the “responsibility vs. responsiveness” (RR) dilemma (e.g., Mair, 2009), often resulting in a moderation of economic positions (see, e.g., Wendler, 2013; Closa and Maatsch, 2014; Karyotis et al., 2014; Maatsch, 2014). This posits that parties that are either in government or legitimately aspire to access the executive will be constrained in both their campaign proposals and policy output by responsibility considerations towards the external actors with which states are interconnected (e.g., Karremans and Damhuis, 2020; Romeijn, 2020). Most of the time, within the international institutional framework of the post-WWII globalised world, this equates to conforming to the hegemonic neoliberal policy paradigm (e.g., Cerny, 2010), which in turn means adhering to right-of-centre economic positions. These external pressures are particularly intense for Western European countries: indeed, not only they are embedded and play a key role in the global financial and economic system regulated by institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Organisation for Economic Development and Co-operation (OECD), and the World Bank (WB); but also, they are often members of the European Union (EU).1 Indeed, EU membership adds additional external constraints to national policy-making through its acquis communitaire, that is the provisions in its Treaties (e.g., Rose, 2014), with additional and even more demanding pressures in a neoliberal direction if a country is also part of the Eurozone (e.g., Laffan, 2014). In the face of these international commitments and as a legitimate candidate for being in government, social democracy then ought to be responsible in both its policy proposals and output, and maintain a good fiscal reputation according to the standards set within such frameworks (e.g., Hellwig, 2012; Ezrow and Hellwig, 2014). In practise, this means a rightwards shift towards more economically centrist positions compared to traditional social democratic stances.

Therefore, this strand of works allows deriving the first hypothesis to guide the empirical analysis of this article:

Hp1: After WWII, as time passes, Western European social democratic parties decrease their emphasis on traditional economic left issues.

Yet, other empirical contributions have challenged the illustrated consensus on the evolution and moderation of social democratic economic positions over time. First off, some underline how it is difficult to tell a “one-size-fits-all” storey that applies to all Western European countries over the decades, as the many contextual differences lead to mixed results and the impossibility of identifying universal trends (e.g., Jansen et al., 2013). Furthermore, and even more relevantly, recent works based on MARPOR data come to the opposite conclusion compared to the previous strand. Indeed, these show that, to different extents, Western European social democratic parties have not moved away from traditional economic left positions over time. For instance, Adam and Ftergioti (2019) illustrate that such formations in Western Europe have not significantly changed their economic stances since the 1970's, therefore also considering the key phase of Third Way social democracy. Others go even further, arguing that the salience put by social democracy on traditional left-wing economic issues such as state interventionism and market regulation, the welfare state and support for working-class stances has rather increased over time, especially after the turn of the millennium, in a positional recalibration after the rightwards shift of the Third Way years (e.g., Emanuele, 2021a; Polacko, 2022).

Potential explanations for these results mirror those concerning the strand of works on “moderation” from a substantive viewpoint. For a start, party competition and “responsiveness” dynamics within the RR dilemma could also justify an exacerbation of economic positions on the part of social democracy. Indeed, especially following the Great Recession of the late-2000's, whilst Western European social democratic formations had to be financially responsible in their role as governing parties, they also had to be responsive to progressively more left-wing voters across the continent (e.g., Mair, 2008), and especially so on economic matters traditionally owned (Petrocik, 1996) by the left such as welfare provisions and market regulation (Bremer, 2018). Moreover, whilst it is true that external pressures on national political systems in Western Europe are intense, domestic factors are still able to play an important role in countering these forces with constraints of their own. First, both the longstanding policy orientations and rather large organisational size of social democratic parties impinge their capability to significantly alter their programmatic profiles (e.g., Adams et al., 2009). Second, there is a degree of path-dependency deriving from the key role of such formations in labour-capital bargaining, with different national trajectories: meaning that where there are stronger actors, for instance trade unions, within such processes, it will be more difficult for social democracy to depart from its traditional positions (e.g., Garrett, 1998; Hellwig, 2016). Third, social democrats will also want to defend their historical political and social achievement at the national level, that is the construction of welfare states, vis-à-vis the ongoing processes that threaten to undermine it (e.g., Kriesi et al., 2008).

This leads directly into another key determinant of the potential exacerbation of social democratic economic stances. Indeed, whilst it was shown that economic globalisation could be conducive to economic moderation and convergence to the centre, there are also arguments for the relationship going in the opposite direction. The scholarly debate concerning the effect of economic globalisation on party positions sees two opposite camps: the “efficiency” and the “compensation” theses (e.g., Adam and Kammas, 2007; Hellwig, 2016). Whilst the former aligns with the aforementioned works on moderation and convergence, the latter posits that economic globalisation pushes social democratic parties further to the economic left (e.g., Swank, 2002). This is because this phenomenon entails greater international competition and deregulation, compelling such formations to defend their distinctive policy proposals and tackle these undesired effects with dedicated policies such as taxes on capital (Basinger and Hallerberg, 2004). Moreover, some argue that economic globalisation increases class conflict, which leads social democracy to persist with the economic positions that it traditionally owns if not, in some cases, to make them even more salient (e.g., Garrett, 1998; Swank, 2002; Milner and Judkins, 2004). Hence, economic globalisation is also seen in the literature as conducive to social democratic parties adopting more left-wing positions from an economic viewpoint.

Therefore, the illustrated MARPOR-based empirical evidence and the theoretical sources that explain the potential mechanism of an economic left-wing exacerbation of Western European social democracy over time allow formulating a second hypothesis for the ensuing empirical analysis:

Hp2: After WWII, as time passes, Western European social democratic parties increase their emphasis on traditional economic left issues.

The article now turns to how the two contrasting hypotheses concerning the evolution of social democratic economic positions over time in Western Europe will be tested. In terms of spatial framework, it includes the 20 countries generally considered Western European by the relevant literature.2 Further, from a temporal viewpoint, the article covers the period between the final years of WWII and the contemporary days (1944–2021). This long timespan hides significant variation in terms of years considered by the main source of data employed, the MARPOR, for each country (see Table 1), with data on “third-wave” democracies in Southern Europe (i.e., Cyprus, Greece, Portugal, and Spain; Huntington, 1991) only available from the mid-1970's onwards at the earliest.3 This cross-sectional and longitudinal extension allows for the maximum possible generalisability of the article's findings across the region of interest considering the spatial and temporal coverage of the MARPOR. Furthermore, long-term analyses such as the one presented in the article refrain from issues of “short-termism,” whereby conclusions on political phenomena are drawn by way of comparison with the rather exceptional standards of the mid-twentieth century (Enyedi and Deegan-Krause, 2007).

As to the units of analysis, the task of selecting social democratic parties to analyse is far from straightforward, given the acknowledged heterogeneity of this party family (e.g., Volkens, 2004). Hence, in order to achieve a selection of cases that is as replicable and uncontroversial as possible, the task of identifying which parties classify as social democratic was left to the MARPOR itself, which does so in its dataset under the category “parfam = 30 (social democratic parties).” Amongst these formations, in order to properly capture the aspect of interest here and that is the mainstream left component that has become part of the “core” (Smith, 1989) of Western European party systems (Keman, 2017), the electorally best-performing party for each of the 369 national general elections within the illustrated spatial-temporal framework was selected.4 Hence, this criterion allows considering the main social democratic party of each political system at any given election and, in the very rare cases where this formation changes, the important historical transformations in terms of electoral performance and configuration of the mainstream left's political offer within national party systems. Due to its political peculiarities, the only exception to this criterion is the Italian case, where between 1946 and 1996 the main party of the mainstream left is represented by formations falling outside of the “parfam = 30” category (i.e., the Italian Communist Party between 1946 and 1989 and the Democratic Party of the Left between 1992 and 1996).5 Table 1 recaps the analysed social democratic parties per country and the dates of the elections in which they are considered.

As to the empirical analysis, the relationship between time and social democratic emphasis on traditional economic left issues is tested by operationalising the focal predictor in three ways. First off, to analyse its linear effect on social democratic economic positions, time is considered as a continuous Election date variable representing the date of each analysed general election, which ranges between 17 September 1944 (1944 Swedish general election) and 26 September 2021 (2021 German general election). Additionally, the effects of larger periods on the analysed “explanandum” are tested by employing two categorical variables. Following Emanuele (2021b), the article's time frame is first divided into four Phases of substantive interest: (1) the “Golden Age” of mass parties and party system stability in Western Europe (Mair, 1994; Janda and Colman, 1998), which runs between the beginning of the time frame in 1945 ending in 1967, the year of Lipset and Rokkan's (1967) “freezing hypothesis;” (2) the “Post-L&R” (Lipset and Rokkan) phase, running between the two political watershed years of 1968 and 1989, when the fall of the Berlin Wall occurred; (3) the “Post-Wall” phase, beginning in 1990 and lasting until the beginning of the Great Recession in Europe (2009); (4) and the “Great Recession” phase, running from 2010 until the end of the analysed time frame and coinciding with the years when the economic, political and social consequences of the global financial crisis fully manifested in Western Europe. Moreover, to provide a more fine-grained breakdown of the effect of different historical periods on social democratic economic positioning, the time frame is further divided into the eight analysed Decades through a categorical variable ranging between (1) the 1940's and (8) the 2010's and beyond (“2010+s”), also considering the sole election of the 2020's (Germany, 2021).

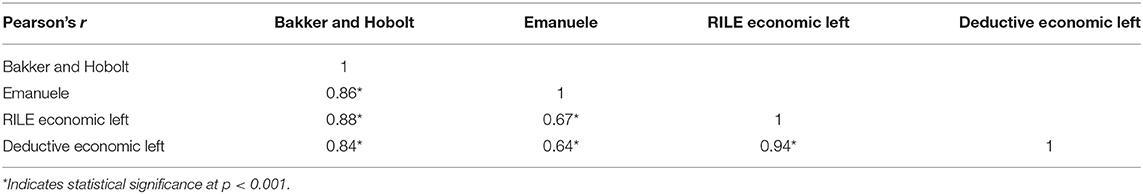

With regard to the dependent variable, i.e., the emphasis of social democracy on traditional left economic issues, this is operationalised by presenting four different aggregations of items from the MARPOR codebook, to ensure the robustness of this article's findings. The focus on electoral manifesto data from the MARPOR to operationalise party positions follows a twofold rationale.6 Indeed, on the one hand, it is arguably the most widely employed data source in comparative investigations of party positions due to its extension across both time and space (e.g., Laver and Garry, 2000). As per above, this unmatched longitudinal and cross-sectional coverage allows for a long and wide investigation of how social democratic emphasis on traditional economic left issues evolves over time in the region, which would not be possible with more idiosyncratic spatial-temporal frameworks. On the other hand, because this source of data is common to both contrasting viewpoints in the literature concerning the moderation or exacerbation of Western European social democracy's economic left stances, relying on it allows both consistency and comparability with available works, with an eye to contributing to and potentially settling this debate. Going into detail with regard to the economic left measures, three out of four of them are the pre-existing indicators of economic left emphasis from Bakker and Hobolt (2013) and Emanuele (2021a), as well as the aggregation of the left items that are economic in nature included in the MARPOR's own left-right index, the “RILE” (Budge and Klingemann, 2001); whilst the fourth one is an original deductive aggregation of MARPOR items that were deemed traditional economic left issues on a theoretical basis. All such measures are cross-validated by virtue of being strongly to very strongly correlated with each other, as demonstrated by the Pearson's r-values reported in Table 2, whilst Table 3 recaps the MARPOR items making them up. Furthermore, to provide a more disaggregated and fine-grained analysis of how the emphasis of social democratic parties on specific traditional economic left issues changes over time, the single MARPOR items reported in the various illustrated aggregations will also be employed as dependent variables in separate analyses.

Table 2. Correlation matrix between different operationalisations of the dependent variable (Pearson's r-values).

Further, as these baseline models only test the impact of the focal predictor, time, on social democratic parties' emphasis on traditional economic left issues, the analyses are replicated by including some control variables that may also have an effect on the dependent variable. For a start, the presence of competitive radical left opponents (henceforth “RLPs”), i.e., parties to the left of social democrats that more strongly advocate traditional economic left stances (e.g., March, 2011), is a relevant factor. Indeed, it may pressure mainstream formations, and especially social democratic parties along the economic issue dimension (e.g., Adams and Somer-Topcu, 2009), into adjusting their policy programs towards more similar and hence left-wing positions (e.g., Pontusson and Rueda, 2010). Therefore, a Radical left strength indicator has been included in the analysis, capturing the percentage shift in votes from the previous election of the radical left bloc in each country, which was considered as made up of all “far left” parties in the “PopuList” dataset (Rooduijn et al., 2019). Moreover, powerful trade unions, i.e., another traditional representative of workers along the class cleavage and focus of strands of literature such as “power resource theory” (e.g., Brady et al., 2016), may exert strong pressures on social democratic parties to maintain a distinctively left-wing economic profile through their direct links with them (e.g., Pierson, 2001). Hence, a Trade union density indicator has also been included, by relying on data from the ICTWSS database (Visser, 2019).7 Finally, as discussed above, “responsibility” considerations (e.g., Mair, 2009) related to social democratic parties' governing status or the realistic prospect of it may exert powerful constraints on these formations' room for political manoeuvre, resulting in a rightwards pressure from an economic viewpoint. This is why a Government status dichotomous variable has also been included, operationalising whether at the time of the election and, hence, during the campaign when the investigated manifesto was drafted, the social democratic party was in the opposition (0) or in government (1).

To correctly estimate the effects of this article's focal predictors on the dependent variables, it is necessary to specify the regression models by taking into account the time-series-cross-section (TSCS) nature of the employed dataset. In particular, the data presents repeated observations over time (369 elections) over the same fixed units (countries) and only just constitutes a cross-sectionally dominant pool (Stimson, 1985), as there are slightly more cross-section (20 countries) than temporal units (on average, 18.45 elections per country). These characteristics might be conducive to statistical issues such as heteroskedasticity and unobserved heterogeneity.8 As diagnostic tests confirm the presence of both such problematic aspects in all models, ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions with panel-corrected standard errors (PCSE) and country fixed effects are performed to adequately account for these issues (Beck and Katz, 1995).9

An initial idea concerning the empirical relationship between the focal and dependent variable can be provided by correlation analyses. Indeed, as reported in Supplementary Table 1, Pearson's r-values indicate that all three focal predictors are positively correlated with all four presented operationalisations of social democratic emphasis on traditional economic left issues, indicating its increase over time at different levels of statistical significance. Hence, this would preliminarily point to both a confirmation of Hp2 and a rejection of Hp1. In particular, a more fine-grained look at what MARPOR items significantly become more salient over time (see Supplementary Table 2) shows that this increase seems mostly driven by issues surrounding the welfare state in its Beveridgean conception (Beveridge, 1942; per504 and per506), as well as equality (per503), market regulation (per403), and labour groups (per701). Interestingly, however, the emphasis on themes traditionally associated with the economic left in its classical conception of state intervention in the economy (e.g., Downs, 1957, p. 116) such as, in particular, economic planning (per404), controlled economy and minimum wages (per412), and nationalisation (per413) seems to decrease with high levels of statistical significance and relatively large coefficients as time goes on. Hence, whilst at the aggregate level there seems to be a rather robust increase of social democratic emphasis on traditional economic left issues, a more differentiated account of substantive interest can be provided by disaggregating the various MARPOR items under consideration.

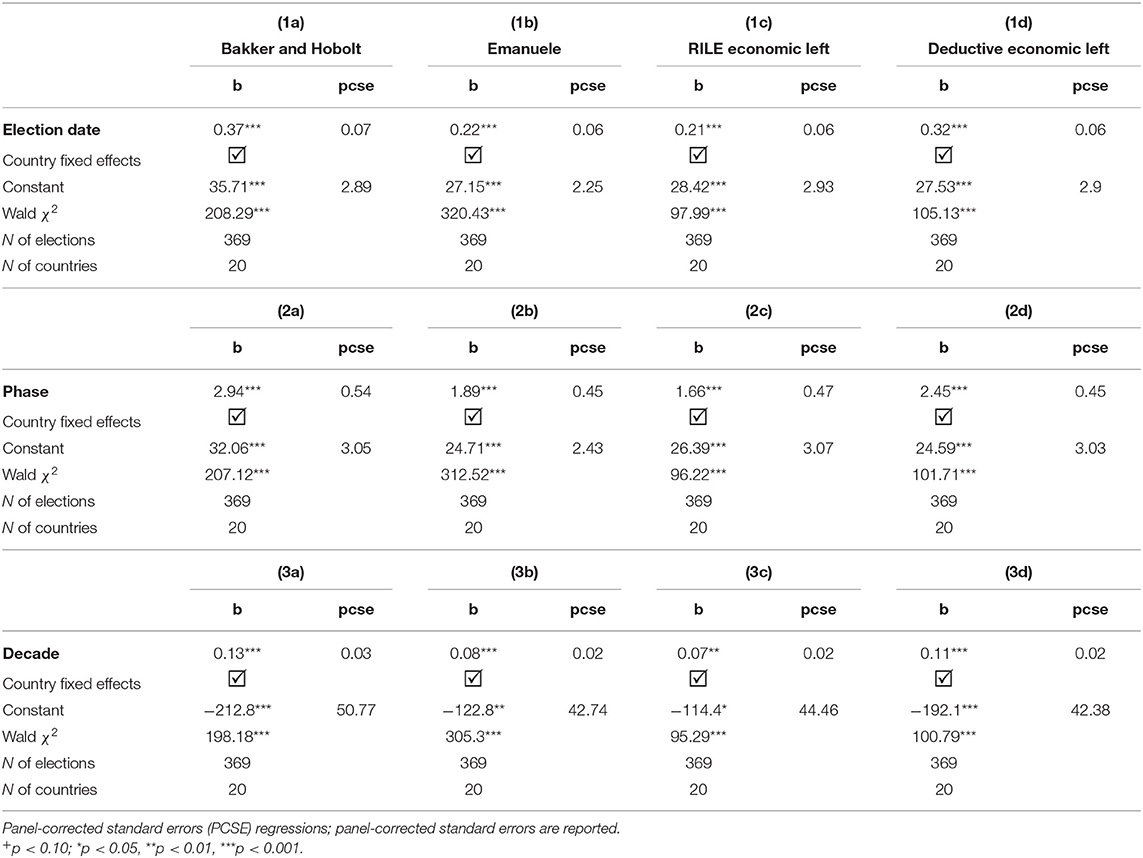

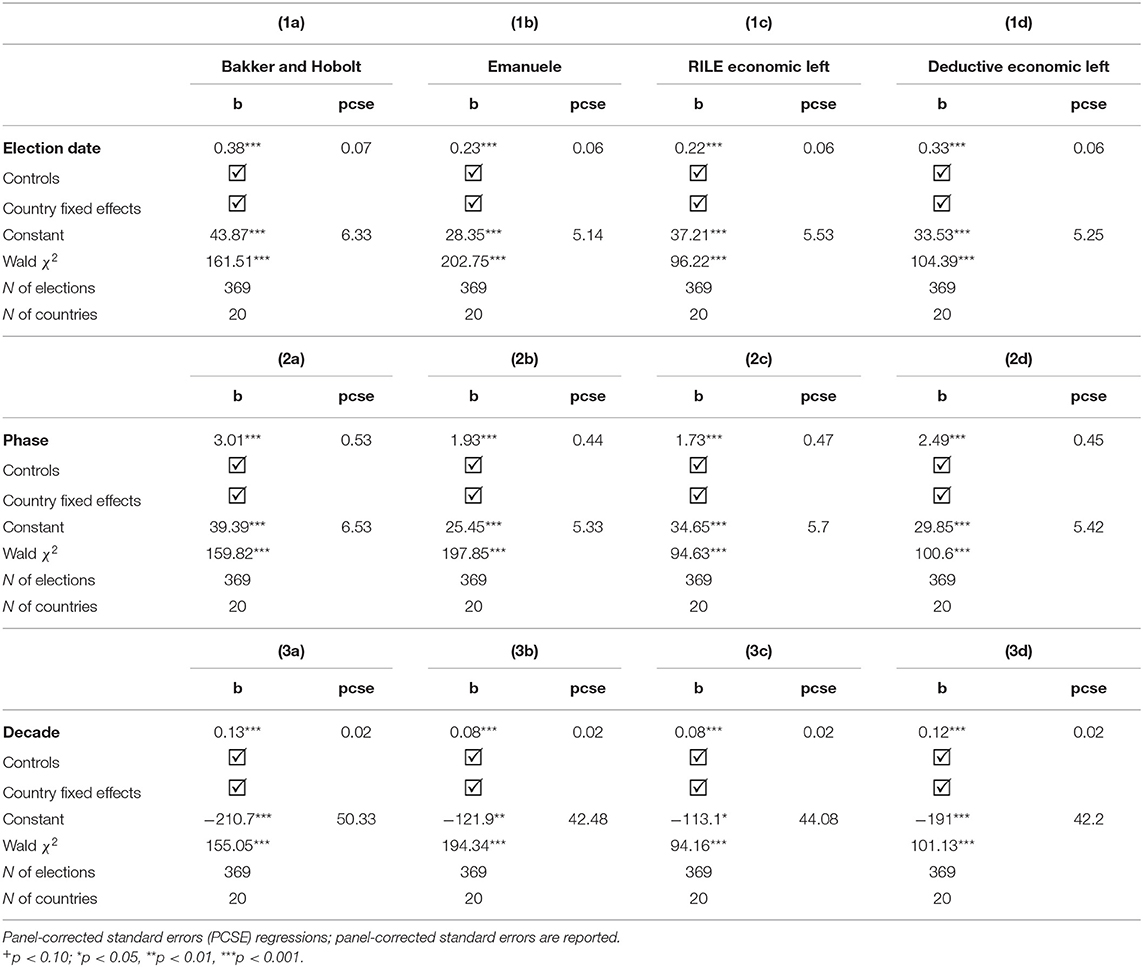

To test whether this picture is confirmed by more demanding statistical analyses, several regression models are presented.10 Table 4 presents the baseline models that test the effects of time in its continuous conception as the Election date (Models 1) and as a categorical variable operationalising Phases (Models 2) and Decades (Models 3), whilst also controlling for country fixed effects. As evident, in all of its operationalisations, time has a positive and statistically significant effect (at p < 0.001 in all but one case, which is significant at p < 0.01) on the four employed dependent variables. This indicates that the emphasis of social democratic parties on traditional economic left issues has, indeed, increased over time. Further, all of these findings are also robust to the inclusion of the controls introduced above, as shown in the full models reported in Table 5. Indeed, by also considering the relative electoral strength of the radical left bloc, trade union density, and the government status of social democratic parties, all focal predictors operationalising time in its different forms have a positive and statistically significant (always at p < 0.001) effect on economic left emphasis in all models. It is noteworthy that, out of the included controls, only being in government has at times statistically significant effects on the economic left emphasis of social democratic parties (either at p < 0.05 or, marginally, at p < 0.10). Interestingly, the negative signs of the coefficients for government status indicate that executive responsibility exercises an important constraint on the ability of social democratic parties to adopt economically left-wing policy positions, hence fully going in the direction of the “responsibility vs. responsiveness (RR) dilemma” literature (e.g., Mair, 2009). Conversely, neither the relative strength of the radical left bloc nor trade union density ever present statistically significant effects on the emphasis that social democratic parties put on traditional economic left issues.11

Table 4. Time (continuous and categorical variables) and measures of social democratic economic left emphasis. Baseline models.

Table 5. Time (continuous and categorical variables) and measures of social democratic economic left emphasis. Full models.

In sum, these findings are robust to the different presented operationalisations of both the explanandum and focal predictor, as well as to the inclusion of relevant control variables and the consideration of national specificities through country fixed effects. Therefore, these regression models demonstrate that social democratic emphasis on traditional economic left issues has increased over time, coming to the same conclusion reached by the illustrated correlation analyses. In light of this evidence, the presented Hp2 is confirmed whilst, conversely, Hp1 must be rejected.

More useful information on the effects of time can be retained by going into greater detail about these findings. Table 6 reports the same full models, but more specifically by looking into the effects of individual Phases (Models 4) and Decades (Models 5) on the various measures of social democratic economic left emphasis. Both models come to the same striking conclusion: that is, the significant increase in social democratic emphasis on traditional economic left issues is driven almost exclusively by the years following the Great Recession of the late 2000's. That is because, as evident from the regression table, in both sets of models the only categories to have statistically significant (at p < 0.001 in all but one case, significant at p < 0.01) and positive effects are the “Great Recession” phase and the “2010+s” decade, which both include the years between 2010 and 2021. Indeed, the levels of statistical significance of such categories clearly show how they account for the vast majority of the variance in the dependent variable, and the strength of the (positive) effects is indicated by the vastly larger coefficients that they take on. These findings are particularly significant from a substantive viewpoint as they indicate how, despite going through very different historical periods and moments of social democratic thought and development such as the Third Way, the emphasis of such formations on traditional economic left issues seems to have remained virtually the same over the six decades following WW2. Already in itself, this is an interesting substantive conclusion that would deserve further exploration, with regard to both the historical assessment of Western European social democracy in the twentieth century and the strategic behaviour of such formations whilst determining their programmatic profiles in the context of domestic party competition. Even more importantly, another important substantive conclusion that emerges from this analysis is the seemingly fundamental role of the Great Recession in a programmatic recalibration of Western European social democracy towards the economic left, as underlined by previous contributions (e.g., Emanuele, 2021a; Polacko, 2022).

Yet, the employed dependent variables are aggregations of several MARPOR items of substantive interest and with vastly different content. Hence, it would be interesting to perform additional regressions by employing individual Manifesto Project items as the dependent variables, to verify specifically which economic left issues are more (or less) emphasised by Western European social democratic parties over time. This might be conducive to different patterns emerging amongst the various individual measures employed in the aggregation, similarly to the initial correlation analyses. Table 7 presents OLS regressions with PCSEs, country fixed effects, and the introduced controls regressing each analysed MARPOR category on the Election date continuous temporal predictor (Models 6).12 Moreover, to make sure that variation in the emphasis put on a specific issue is independent of the variation in the emphasis on all other economic left issues and particularly those that might be substantively associated with it, the replication of the same models by including all other MARPOR categories as additional controls is also reported (Models 7).13

Indeed, a rather differentiated picture emerges from the regressions, whereby whilst some economic left MARPOR items are significantly more emphasised over time, the relationship goes in the opposite direction with other issues, which instead are significantly de-emphasised as time goes on. Additionally, the emphasis put by social democratic parties on the remaining MARPOR categories does not seem to change significantly over time. This general trend is in line with the preliminary correlation analyses, which also seem to be corroborated by a more detailed investigation of specifically which MARPOR items become significantly more or less emphasised over time. In particular, the Models 6 show how it is chiefly the issues surrounding the welfare state and broad questions of equality (per503, per504, and per506) that increase in their salience over time (at p < 0.001); with other themes such as support for labour groups (per701) and market regulation (per403) also more emphasised, but at a lower level of statistical significance (p < 0.01). Conversely, the relationship between time and three traditional economic left issues such as economic planning (per404), controlled economy and minimum wages (per412), and nationalisation (per413) is negative and very statistically significant (at p < 0.001), indicating that Western European social democratic parties significantly decrease their emphasis on state involvement in the economy over time. Furthermore, a marginal negative effect (p < 0.1) of time on the emphasis put on positive attitudes concerning economic protectionism also emerges. This picture is further reinforced when analysing the regressions that include all other economic left MARPOR items as additional controls (Models 7). Indeed, all positive effects are confirmed in their statistical significance (at least p < 0.05) and most remain unchanged, indicating in particular that it is especially the emphasis put by social democratic parties on issues of welfare and equality to increase over time. Likewise, however, significant statistical effects persist for all three MARPOR items for which a strongly statistically significant and negative relationship with time was identified, especially for what concerns the per404 on economic planning and the per412 on controlled economy and minimum wages (p < 0.001). These differentiated and more fine-grained findings have several substantive and, especially, methodological implications, which ought to be discussed at greater length.

Important findings emerge from the empirical analysis of this article. First, from a substantive viewpoint, the results depict a more nuanced picture as to the evolution of Western European social democracy's emphasis on traditional economic left issues if compared to most scholarly accounts. That is, these parties do not follow a unique trend in terms of the salience of all economic left issues over time, but rather they increase the emphasis they put on some whilst decreasing it for others. This seems to be in line with arguments concerning the programmatic ambivalence of contemporary social democracy in Western Europe on economic matters, whereby a greater role is played by issues of welfare and market regulation whilst however other positions are aligned with neoliberal prescriptions (e.g., Bremer, 2018). In this regard, both sides of the debate seem to be at least partially correct if we look at individual economic issues traditionally owned by the left. Yet, staying at the aggregate level analysed by the previous contributions in the literature, one of the two presented hypotheses (Hp2) prevails over the other (Hp1), leading to important conclusions. Indeed, the analysis shows that, overall, after WW2 Western European social democracy increased its emphasis on traditional economic left issues as a whole. Social democracy does not seem to significantly alter its economic positions until the 2010's, that is after the Great Recession, during which it is possible to see a very significant shift towards the economic left. Strikingly, these years singlehandedly drive the entire effect of time on social democratic economic left emphasis at the aggregate level. This confirms the findings of recent empirical accounts (e.g., Emanuele, 2021a; Polacko, 2022) and, as underlined by other authors (e.g., see Meyer and Spiegel, 2010), might signpost that social democracy acknowledged the urgency to distinguish itself from the collapsing international neoliberal economic model, after having enthusiastically endorsed it during the Third Way years (e.g., Giddens, 1998, 2003). Yet, other mechanisms might have also contributed to the resilience of traditional economic left positions in social democratic programmatic platforms. For instance, as electorates across Western Europe have become increasingly left-wing from an economic viewpoint (e.g., Mair, 2008), social democratic parties may have had to strategically be responsive on this front in their electoral supply and hence push their economic agenda further to the left. Furthermore, what might have also contributed to the strengthening of this economically left profile of social democratic formations is the notorious path-dependency that constrains parties in terms of their previous ideological positions (e.g., Strøm, 1990), and especially so for organisationally large ones (e.g., Adams et al., 2009). Finally, social democratic parties are also limited in the capacity to depart from their traditional economic left stances by their key role in national labour-capital bargaining, especially where there are strong trade unions (e.g., Garrett, 1998; Hellwig, 2016). This, for instance, may lead these formations to defend the national welfare state structures they have built over time from international processes, such as economic globalisation, that put them in jeopardy (e.g., Kriesi et al., 2008). Were these substantive findings to be confirmed by additional works, it would mean that these mechanisms are worth exploring further: an effort that can surely build upon the analysis of this article.

Yet, the most important implications of this article's analysis are methodological in nature, as they concern the key source of data employed in this and similar investigations, the MARPOR, and the validity of the inferences drawn when employing it. Indeed, the illustrated disaggregation shows that the significant increase in social democratic economic left emphasis in Western Europe is mostly driven by problematic MARPOR items such as those on equality (per503) and the welfare state in its Beveridgean conception (Beveridge, 1942; per504 on welfare state expansion and per506 on education expansion), which are on average the most emphasised economic left themes.14 In particular, the per503 and per504 categories present notorious issues, such as being formulated in excessively broad terms and capturing several different aspects of substantive importance, which would require breaking them down into meaningful subcategories (e.g., Merz et al., 2016; Horn et al., 2017, p. 413). This problem could also be extended to another MARPOR item that social democracy increasingly emphasises over time and is on average amongst the most salient economic left issues: the per701 on support for labour groups. Indeed, this category is so vast that it not only includes support for workers both in general terms and on specific matters, but also themes traditionally pertaining to the welfare state itself such as pension provisions (e.g., Esping-Andersen, 1990).15

In turn, this is likely to lead to another well-known methodological problem in terms of measurement validity that is encountered by the single human coder behind the generation of MARPOR data for any given manifesto and has also been acknowledged by MARPOR investigators themselves: coding seepage (e.g., Klingemann et al., 2006, p. 112; Mikhaylov, 2009). In essence, this is an issue of coding errors, whereby several pairs of MARPOR items, including the per503 on equality and per504 on welfare state expansion, are prone to systematic misclassification. Still, why would this be problematic for the research strand investigating parties' overall emphasis on traditional economic left issues as a whole, if potential misclassifications at the level of individual categories are washed away when looking at aggregate scores?

This is because there is no guarantee that both such MARPOR items pertain exclusively to the economic domain, given the ambiguous formulation of the per503 on equality. The MARPOR codebook prescribes that quasi-sentences within electoral manifestos should fall under this category if they express the “concept of social justice and the need for fair treatment of all people. This may include: special protection for underprivileged social groups; removal of class barriers; need for fair distribution of resources; the end of discrimination (e.g., racial or sexual discrimination)” (Volkens et al., 2020, p. 18). As evident, this formulation is multidimensional and could refer to both economic and non-economic forms of inequality such as, for instance, racial or sexual discrimination. On this basis, therefore, it is impossible to distinguish which parts of the per503 scores are referred to different forms of inequality, economic or non-economic; and, hence, whether this MARPOR item contributes to inflating parties' emphasis on economic matters in a valid fashion.

These formulation problems, with the little discriminating power resulting in greater misinformation (Sartori, 1970), have already been recognised in the literature (e.g., Zulianello, 2014), particularly with regard to the categories concerning the welfare state (per504 and per506). Here, the strategic element of party competition comes into play, as parties will almost always rather opt to blur (e.g., Rovny, 2012) their opposition to greater welfare and education provisions rather than emphasise it (e.g., Budge, 2001, p. 59). These strategies can be adopted through a variety of rhetorical means in textual discourse, which the MARPOR codebook may not be well-equipped to identify. For instance, Zulianello (2014, p. 1,732) illustrates how a party could be in favour of “improving the quality of welfare” whilst intending to do so by reducing the role of the state in this policy area: hence, distinguishing between policy goals (e.g., D'Alimonte et al., 2020) and the different means to attain them.

This point becomes central for the substantive discussion at hand, i.e., social democratic emphasis on economic left issues, as the MARPOR codebook is unable to distinguish the vastly different views on the welfare state between “classical” and Third Way social democracy that emerge from theoretical sources. Indeed, whilst before the 1990's social democracy pursued and built pervasive welfare states following Keynesian prescriptions (e.g., Giddens, 1998), during the Third Way it still emphasised the importance of providing welfare, but rather in a “positive” and “pro-active” version (e.g., Driver and Martell, 2001, p. 39). It pursued an “overhaul” and “rescuing” of the postwar welfare state (Latham, 2001, p. 27) by reducing deficit spending and creating more opportunities for education and labour market participation, which would have led to economic expansion (Giddens, 2000, p. 166). Hence, within its renewed economic outlook, the Third Way promoted a new vision of welfare in opposition to more traditional social democratic stances (e.g., Merkel, 2001, p. 52). In essence, this flagship stance of Third Way social democracy corresponded to an effective recalibration towards more centre-right, neoliberal economic positions. However, the MARPOR items on welfare (per504 and per506) are unsuited to detect this fundamental theoretical difference, and this may lead to serious issues of measurement validity when including such items in aggregate scores of economic left emphasis.

The illustrated issues point to some important questions. For instance, would the findings of this article hold if the increase in social democratic left emphasis on some very salient MARPOR items (per503, per504, per506, and per701) were not to be considered, in light of the doubts concerning their measurement validity? In that case, the disaggregate viewpoint on which other categories increase or decrease in their salience over time would seem to suggest that there might be either a different effect of time on overall social democratic economic left emphasis or no effect at all. Furthermore, it was also shown how actually, in line with alternative and more mainstream accounts depicting an ideological moderation of social democracy over time, the emphasis put by these parties on traditional left-wing positions concerning state involvement in the economy such as economic planning (per404), controlled economy and minimum wages (per412), and nationalisation (per413) significantly decreases over time. More generally, the bigger question concerns the validity of the inferences based on MARPOR data in light of these limitations, and whether results based on this source may be driven by serious issues of measurement validity. This is a legitimate concern especially when MARPOR-based studies come to a substantive conclusion—i.e., Western European social democratic parties moving further to the economic left over time—that seems to be in stark contrast with the common understanding on this matter, theoretical sources on the Third Way, and the empirical evidence emerging from the vast literature on mainstream and social democratic parties' convergence to the centre.

Does this equate to suggesting that all such MARPOR-based inferences are invalid? This is not the case: for instance, whilst recognising some of the highlighted methodological issues, some provide reassurance as to the general validity of manifesto-based measurements, even for those MARPOR items highlighted as problematic (e.g., Horn et al., 2017). Indeed, it is equally plausible and theoretically sound that, as illustrated by the empirical analyses of this article and comparable contributions, this increase in social democratic economic left emphasis is driven entirely by a post-Great Recession response, with these parties reacting to the crisis and collapse of the previously endorsed neoliberal economic model. Therefore, as a good practise when using manifesto data, the suggestion for future research is to enhance the convergent validity (Drost, 2011) of MARPOR-based results by cross-validating them with other sources of data, including but not limited to expert surveys (e.g., the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, see Bakker et al., 2020), data on policy outcomes (e.g., Comparative Agendas Project, 2022), and more qualitative and case-oriented sources. This more cautious approach would reassure as to the validity of results and inferences based on the MARPOR vis-à-vis its illustrated methodological limitations: especially so when the theoretical “stakes” are high, as with the programmatic evolution of Western European social democracy along the economic left-right issue dimension.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

I thank the two reviewers, whose feedback greatly contributed to improving the article.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.873948/full#supplementary-material

1. ^This passage from Ward et al. (2015) on external constraints in general, and Europeanisation in particular, is exemplary: “Such ‘loss of control’ is particularly explicit in the context of European integration (often referred to as an ‘intense case of globalisation;’ Notermans, 2001; Scharpf, 2002; McNamara, 2003; Haupt, 2010). […] Both the ‘neoliberal pressures of open economy’ (Haupt, 2010, p. 7) and the constraints set by supranational bodies such as the EU (but also the International Monetary Fund [IMF], Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], the World Bank, etc.) are further argued to lead to the convergence of party positions on the economic dimension (Huber and Stephens, 2001; Steiner and Martin, 2012)”.

2. ^The countries that were included are Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

3. ^It is important to acknowledge the peculiarities of these new democracies vis-à-vis the more established ones within the spatial framework of the article. Indeed, in the early stages of these democratic regimes there was a widespread political consensus for the development of welfare policies, which were lagging behind in these countries compared to the rest of Western Europe. This, and the frequent predominance of left-wing parties during such phases, also contributed to strengthening the role of the state in the economy. For these reasons, it is important to also account for the presence and peculiarities of these new democracies in the empirical analysis, because they might drive an overall increase in social democratic emphasis on traditional economic left issues, particularly through the 1970's and 1980's. To do so, all the analyses in the manuscript were replicated with a random-effects specification by including a dichotomous variable Third-wave democracies, taking value 1 if the observation is in Cyprus, Greece, Portugal, or Spain and 0 otherwise. The models, reported in full in Supplementary Tables 4–7, confirm the results of the analysis, whilst also frequently highlighting a statistically significant and negative effect of these new democracies on social democratic parties' economic left emphasis.

4. ^See Figure 1 for the number of considered elections per country.

5. ^These parties are in direct succession with each other, as well as with the other formations falling under the “parfam = 30” category in subsequent Italian general elections (see Table 1).

6. ^Employing MARPOR data necessarily ties the present article and its analysis to the defining ‘saliency theory’ framework of this research project (see Budge and Farlie, 1983), whereby party positions along the various dimensions of political contestation are calculated through issue emphasis. Notice that, albeit frequently employed due to the prominence of MARPOR data, this overlap between emphasis and positions has been widely criticised in the literature (see, for instance, Bakker and Hobolt, 2013; Zulianello, 2014).

7. ^Following Emanuele (2018), given the slow-changing nature of this phenomenon, the trade union density data from the ICTWSS have been linearly interpolated and extrapolated as a constant of the extreme value, to cover for several missing observations that would have otherwise greatly reduced the number of observations in the analysis.

8. ^In particular, LR tests of panel heteroskedasticity and Hausman tests between random and fixed effects were performed. As all such probes were statistically significant, this means that the panels are heteroskedastic and unobserved heterogeneity does not allow using random effects. Additionally, Wooldridge (2002) tests of serial correlation were also performed: as none of them returned statistically significant results, it is possible to conclude that there is no autoregressive process in the models.

9. ^Further, dynamics of path dependency in ideological position-taking may constrain the ability of parties to significantly alter their programmatic outlook between elections (e.g., Strøm, 1990). To account for these, all regression models across the article are replicated with the inclusion of lagged dependent variables. The results, reported in Supplementary Tables 8–11, are all substantively confirmed.

10. ^Notice that in all regression models the Election date has been rescaled for the sake of the coefficients' readability.

11. ^Simplified versions of the regression tables are presented for the sake of readability. The full results are available from the author upon request.

12. ^A replication of diagnostic tests by employing the individual MARPOR categories as the dependent variable confirms that this is the correct model specification.

13. ^Variance inflation factors (VIF) indicate that these models can be estimated correctly, as there are no issues of multicollinearity between the included regressors (e.g., Chatterjee and Hadi, 1986).

14. ^The pooled mean percentages of emphasis put by Western European social democratic parties on individual economic left MARPOR items throughout the analysed time frame are reported in Supplementary Table 3.

15. ^For the MARPOR codebook, see Volkens et al. (2020).

Adam, A., and Ftergioti, S. (2019). Neighbors and friends: how do European political parties respond to globalization? Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 59, 369–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2019.05.002

Adam, A., and Kammas, P. (2007). Tax policies in a globalized world: Is it politics after all? Public Choice 133, 321–341. doi: 10.1007/s11127-007-9190-9

Adams, J., Clark, M., Ezrow, L., and Glasgow, G. (2004). Understanding change and stability in party ideologies: do parties respond to public opinion or to past election results? Br. J. Polit. Sci. 34, 589–610. doi: 10.1017/S0007123404000201

Adams, J., Haupt, A. B., and Stoll, H. (2009). What moves parties? The role of public opinion and global economic conditions in Western Europe. Comparat. Polit. Stud. 42, 611–639. doi: 10.1177/0010414008328637

Adams, J., and Somer-Topcu, Z. (2009). Policy adjustment by parties in response to rival parties' policy shifts: spatial theory and the dynamics of party competition in twenty-five post-war democracies. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 39, 825–846. doi: 10.1017/S0007123409000635

Arndt, C. (2014). Social democracy's mobilization of new constituencies: the role of electoral systems. Party Polit. 20, 778–790. doi: 10.1177/1354068812453372

Bakker, R., and Hobolt, S. B. (2013). “Measuring party positions,” in Political Choice Matters: Explaining the Strength of Class and Religious Cleavages in Cross-National Perspective, eds G. Evans and N. D. De Graaf (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 27–45. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199663996.003.0002

Bakker, R., Hooghe, L., Jolly, S., Marks, G., Polk, J., Rovny, J., et al. (2020). 1999 – 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File. Version 1.2. chesdata.eu. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Basinger, S. J., and Hallerberg, M. (2004). Remodeling the competition for capital: how domestic politics erases the race to the bottom. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 98, 261–276. doi: 10.1017/S0003055404001133

Beck, N., and Katz, J. N. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with Time-Series Cross-Section Data. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 89, 634–647. doi: 10.2307/2082979

Best, R. E. (2011). The declining electoral relevance of traditional cleavage groups. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 3:279. doi: 10.1017/S1755773910000366

Beveridge, W. (1942). Social Insurance and Allied Services. Report. London: H. M. Stationery Office.

Brady, D., Blome, A., and Kleider, H. (2016). “How politics and institutions shape poverty and inequality,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Social Science of Poverty, eds D. Brady and L. M. Burton (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 117–140.

Bremer, B. (2018). The missing left? Economic crisis and the programmatic response of social democratic parties in Europe. Party Polit. 24, 23–38. doi: 10.1177/1354068817740745

Budge, I. (2001). “Validating the manifesto research group approach,” in Estimating the Policy Positions of Political Actors, ed M. Laver (London: Routledge), 50–65. doi: 10.4324/9780203451656_chapter_4

Budge, I., and Farlie, D. J. (1983). Explaining and Predicting Elections: Issue Effects and Party Strategies in Twenty-three Democracies. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Budge, I., and Klingemann, H. D. (2001). “Finally! comparative over-time mapping of party policy movement,” in Mapping Policy Preferences: Estimates for Parties, Electors, and Governments 1945-1998, eds I. Budge, H. D. Klingemann, A. Volkens, J. Bara, and E. Tanenbaum (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 19–50.

Cerny, P. (2010). Rethinking World Politics: A Theory of Transnational Neopluralism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199733699.001.0001

Chatterjee, S., and Hadi, A. S. (1986). Influential observations, high leverage points, and outliers in linear regression. Statist. Sci. 1, 379–393.

Closa, C., and Maatsch, A. (2014). In a spirit of solidarity? Justifying the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) in national parliamentary debates. J. Common Market Stud. 52, 826–842. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12119

Comparative Agendas Project (2022). Comparative Agendas Project – Comparing Policies Worldwide. Available online at: https://www.comparativeagendas.net/ (accessed February 1, 2022).

D'Alimonte, R., De Sio, L., and Franklin, M. N. (2020). From issues to goals: a novel conceptualisation, measurement and research design for comprehensive analysis of electoral competition. West Eur. Polit. 43, 518–542. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2019.1655958

Dalton, R. J. (2013). Citizen Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Washington, DC: Cq Press.

Driver, S., and Martell, L. (2001). “Left, right and the third way,” in The Global Third Way Debate, ed A. Giddens (Cambridge: Polity Press), 147–161.

Drost, E. A. (2011). Validity and reliability in social science research. Educ. Res. Perspect. 38, 105–123. Available online at: https://www.erpjournal.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/ERPV38-1.-Drost-E.-2011.-Validity-and-Reliability-in-Social-Science-Research.pd

Emanuele, V. (2018). Cleavages, Institutions and Competition: Understanding Vote Nationalization in Western Europe (1965–2015). London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Emanuele, V. (2021a). Lost in translation? class cleavage roots and left electoral mobilization in Western Europe. Perspectiv. Polit. 2021, 1–19. doi: 10.1017/S1537592721000943

Emanuele, V. (2021b). “Class cleavage structuring in Western Europe: a sealed fate?,” in Paper presented at the 2021 Italian Political Science Association (SISP) General Conference (London).

Enyedi, Z., and Deegan-Krause, K. (2007). “Cleavages and their discontents,” in Paper presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshops, Helsinki, 7-12 May. Available online at: https://ecpr.eu/Filestore/PaperProposal/e6d4a16e-e8f2-4ffe-a120-99f4631ed6d0.pdf (accessed February 1, 2022).

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Evans, G., and Tilley, J. (2012). How parties shape class politics: explaining the decline of the class basis of party support. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 42, 137–161. doi: 10.1017/S0007123411000202

Evans, G., and Tilley, J. (2013). “Ideological convergence and the decline of class voting in Britain,” in Political Choice Matters: Explaining the Strength of Class and Religious Cleavages in Cross-National Perspective, eds G. Evans and N. D. de Graaf (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 87–113. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199663996.003.0004

Evans, G., and Tilley, J. (2017). The New Politics of Class: The Political Exclusion of the British Working Class. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198755753.001.0001

Ezrow, L., and Hellwig, T. (2014). Responding to voters or responding to markets? Political parties and public opinion in an era of globalization. Int. Stud. Quart. 58, 816–827. doi: 10.1111/isqu.12129

Franklin, M. N. (1992). “The decline of cleavage politics,” in Electoral Change: Response to Evolving Social and Attitudinal Structure in Western Countries, eds M. Franklin, T. Mackie, and H. Valen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 383–405.

Garrett, G. (1998). Partisan Politics in the Global Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511625633

Giddens, A. (2003). The Progressive Manifesto. New Ideas for the Centre-Left. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gingrich, J., and Häusermann, S. (2015). The decline of the working-class vote, the reconfiguration of the welfare support coalition and consequences for the welfare state. J. Eur. Social Pol. 25, 50–75. doi: 10.1177/0958928714556970

Goldberg, A. C. (2020). The evolution of cleavage voting in four Western countries: structural, behavioural or political dealignment? Eur. J. Polit. Res. 59, 68–90. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12336

Haupt, A. B. (2010). Parties' responses to economic globalization: what is left for the left and right for the right? Party Polit. 16, 5–27. doi: 10.1177/1354068809339535

Hellwig, T. (2012). Constructing accountability: party position taking and economic voting. Comparat. Polit. Stud. 45, 91–118. doi: 10.1177/0010414011422516

Hellwig, T. (2016). “The supply side of electoral politics: how globalization matters for party strategies,” in Globalization and Domestic Politics: Parties, Elections, and Public Opinion, eds J. Vowles and G. Xezonakis (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 31–51. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198757986.003.0002

Horn, A., Kevins, A., Jensen, C., and Kersbergen, K. V. (2017). Peeping at the corpus – what is really going on behind the equality and welfare items of the Manifesto project? J. Eur. Soc. Pol. 27, 403–416. doi: 10.1177/0958928716688263

Huber, E., and Stephens, J. D. (2001). Development and Crisis of the Welfare State: Parties and Policies in Global Markets. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226356495.001.0001

Huntington, S. P. (1991). The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Janda, K., and Colman, T. (1998). Effects of party organization on performance during the ‘golden age’ of parties. Polit. Stud. 46, 611–632. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.00157

Jansen, G., Evans, G., and De Graaf, N. D. (2013). Class voting and Left–Right party positions: a comparative study of 15 Western democracies, 1960–2005. Soc. Sci. Res. 42, 376–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.09.007

Karremans, J., and Damhuis, K. (2020). The changing face of responsibility: a cross-time comparison of French social democratic governments. Party Polit. 26, 305–316. doi: 10.1177/1354068818761197

Karreth, J., Polk, J. T., and Allen, C. S. (2013). Catchall or catch and release? The electoral consequences of social democratic parties' march to the middle in Western Europe. Comparat. Polit. Stud. 46, 791–822. doi: 10.1177/0010414012463885

Karyotis, G., Rüdig, W., and Judge, D. (2014). Representation and austerity politics: attitudes of Greek voters and elites compared. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 19, 435–456. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2014.977478

Keman, H. (2011). Third ways and social democracy: the right way to go? Br. J. Polit. Sci. 41, 671–680. doi: 10.1017/S0007123410000475

Keman, H. (2017). Social Democracy: A Comparative Account of the Left-Wing Party Family. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315166247

Keman, H., and Pennings, P. (2006). Competition and coalescence in European party systems: social democracy and Christian democracy moving into the 21st century. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 12, 95–126. doi: 10.1002/j.1662-6370.2006.tb00390.x

Kirchheimer, O. (1966). “The transformation of the Western European party systems,” in Political Parties and Political Development, eds J. La Palombara and M. Weiner (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 177–200. doi: 10.1515/9781400875337-007

Kitschelt, H. (1994). The Transformation of European Social Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511622014

Klingemann, H. D., Volkens, A., Bara, J., Budge, I., and McDonald, M. (2006). Mapping Policy Preferences II: Estimates for Parties, Electors, and Governments in Eastern Europe, European Union and OECD 1990-2003. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., and Frey, T. (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511790720

Laffan, B. (2014). Testing times: the growing primacy of responsibility in the Euro area. West Eur. Polit. 37, 270–287. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.887875

Latham, M. (2001). “The third way: an outline statement,” in The Global Third Way Debate, ed A. Giddens (Cambridge: Polity Press), 25–35.

Laver, M., and Garry, J. (2000). Estimating policy positions from political texts. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 44, 619–634. doi: 10.2307/2669268

Lipset, S. M., and Rokkan, S. (1967). “Cleavage structures, party systems and voter alignments: an introduction,” in Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives, eds S. M. Lipset and S. Rokkan (New York, NY: Free Press), 1–64.

Maatsch, A. (2014). Are we all austerians now? An analysis of national parliamentary parties' positioning on anti-crisis measures in the eurozone. J. Eur. Public Pol. 21, 96–115. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2013.829582

Mair, P. (1994). “Party organizations: from civil society to the state,” in How Parties Organize: Change and Adaptation in Party Organizations in Western Democracies, edsR. Katz and P. Mair (London: Sage), 1.22.

Mair, P. (2008). The challenge to party government. West Eur. Polit. 31, 211–234. doi: 10.1080/01402380701835033

Mair, P. (2009). Representative versus Responsible Government. MPIfG Working Paper 09/8. Cologne: Max Planck Institute for the Study ofSocieties.

Mair, P., Müller, W. C., and Plasser, F. (2004). Political Parties and Electoral Change: Party Responses to Electoral Markets. London: Sage.

McNamara, K. R. (2003). Globalization, Institutions and Convergence, Fiscal Adjustment in Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Merkel, W. (2001). “The third ways of social democracy,” in The Global Third Way Debate, ed A. Giddens (Cambridge: Polity Press),36–62.

Merz, N., Regel, S., and Lewandowski, J. (2016). The Manifesto Corpus: a new resource for research on political parties and quantitative text analysis. Res. Polit. 3:2016. doi: 10.1177/2053168016643346

Meyer, H., and Spiegel, K. H. (2010). What next for European social democracy? The Good Society Debate and beyond. Renewal 18, 1–14. Avilable online at: https://uk.fes.de/fileadmin/user_upload/publications/files/What_next_for_European_social_democracy.pdf

Mikhaylov, V. (2009). “Measurement issues in the comparative manifesto project data set and effectiveness of representative democracy,” in Dissertation Presented to the University of Dublin, Trinity College in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Dublin).

Milner, H. V., and Judkins, B. (2004). Partisanship, trade policy, and globalization: is there a left right divide on trade policy? Int. Stud. Quart. 48, 95–119. doi: 10.1111/j.0020-8833.2004.00293.x

Petrocik, J. R. (1996). Issue ownership in presidential elections, with a 1980 case study. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 40, 825–850. doi: 10.2307/2111797

Pierson, C. (2001). Hard Choices: Social Democracy in the Twenty-First Century. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing.

Polacko, M. (2022). The rightward shift and electoral decline of social democratic parties under increasing inequality. West Eur. Polit. 45, 665–692. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2021.1916294

Pontusson, J., and Rueda, D. (2010). The politics of inequality: voter mobilization and left parties in advanced industrial states. Comparat. Polit. Stud. 43, 675–705. doi: 10.1177/0010414009358672

Przeworski, A., and Sprague, J. (1986). Paper Stones: A History of Electoral Socialism. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Rennwald, L. (2020). Social Democratic Parties and the Working Class: New Voting Patterns. London: Springer Nature. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-46239-0

Rennwald, L., and Evans, G. (2014). When supply creates demand: social democratic party strategies and the evolution of class voting. West Eur. Polit. 37, 1108–1135. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.920981

Romeijn, J. (2020). Do political parties listen to the(ir) public? Public opinion–party linkage on specific policy issues. Party Polit. 26,426–436. doi: 10.1177/1354068818787346

Rooduijn, M., Van Kessel, S., Froio, C., Pirro, A., De Lange, S., Halikiopoulou, D., et al. (2019). The PopuList. Available online at: www.popu_list.org (accessed February 1, 2022).

Rose, R. (2014). Responsible party government in a world of interdependence. West Eur. Polit. 37, 253–269. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.887874

Rovny, J. (2012). Who emphasizes and who blurs? Party strategies in multidimensional competition. Eur. Union Polit. 13, 269–292. doi: 10.1177/1465116511435822

Sartori, G. (1970). Concept misformation in comparative politics. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 64, 1033–1053. doi: 10.2307/1958356

Scharpf, F. W. (2002). The European social model. J. Common Market Stud. 40, 645–670. doi: 10.1111/1468-5965.00392

Schwander, H., and Manow, P. (2017). ‘Modernize and Die’? German social democracy and the electoral consequences of the Agenda 2010. Socio-Econ. Rev. 15, 117–134. doi: 10.1093/ser/mww011

Smith, G. (1989). Core persistence: change and the ‘people's party’. West Eur. Polit. 12, 157–168. doi: 10.1080/01402388908424769

Steiner, N. D., and Martin, C. W. (2012). Economic integration, party polarisation and electoral turnout. West Eur. Polit. 35, 238–265. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2011.648005

Stimson, J. A. (1985). Regression in space and time: a statistical essay. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 29, 914–947. doi: 10.2307/2111187

Strøm, K. (1990). A behavioral theory of competitive political parties. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 1990, 565–598. doi: 10.2307/2111461

Swank, D. (2002). Global Capital, Political Institutions, and Policy Change in Developed Welfare States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511613371

Visser, J. (2019). ICTWSS Database. Available online at: https://www.ictwss.org/downloads (accessed February 1, 2022).

Volkens, A. (2004). “Policy changes of European Social Democrats, 1945–98,” in Social Democratic Party Policies in Contemporary Europe, eds G. Bonoli and M. Powell (Abingdon: Routledge), 39–60.

Volkens, A., Burst, T., Krause, W., Lehmann, P., Matthieß, T., Merz, N., et al. (2020). The Manifesto Project Dataset - Codebook. Manifesto Project (MRG / CMP / MARPOR). Version 2020b. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

Ward, D., Kim, J. H., Graham, M., and Tavits, M. (2015). How economic integration affects party issue emphases. Comparat. Polit. Stud. 48, 1227–1259. doi: 10.1177/0010414015576745

Wendler, F. (2013). Challenging domestic politics? European debates of national parliaments in France, Germany and the UK. J. Eur. Integr. 35, 801–817. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2012.744753

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Keywords: social democracy, Western Europe, electoral manifestos, economic issues, political left, longitudinal analysis

Citation: Trastulli F (2022) More Left or Left No More? An In-depth Analysis of Western European Social Democratic Parties' Emphasis on Traditional Economic Left Goals (1944–2021). Front. Polit. Sci. 4:873948. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.873948

Received: 11 February 2022; Accepted: 23 May 2022;

Published: 20 June 2022.

Edited by:

Jean-Benoit Pilet, Université Libre de Bruxelles, BelgiumReviewed by:

Sorina Soare, University of Florence, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Trastulli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Federico Trastulli, ZnRyYXN0dWxsaUBsdWlzcy5pdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.