- 1Department of History, School of History and Cultures, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, United States

- 3Departments of Emergency Medicine and Public Health Sciences, Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada

The Vietnam War left a legacy of mostly mixed-race children fathered by American (or other foreign) soldiers and born to Vietnamese mothers. These Vietnamese Amerasian children often had difficulties integrating into their post-conflict societies due to stigmatisation, and they were typically economically severely disadvantaged. This paper compares experiences of Amerasians in Vietnam with those who emigrated to the US as part of various departure programs since the end of the war in 1975. We used SenseMaker®, a mixed-methods data collection tool, to collect 377 narratives from 286 unique participants living in Vietnam and in the US exploring experiences of Amerasians in both countries. These narratives were then self-interpreted by the study participants using a questionnaire that generated a quantitative dataset. In this paper we analyse the self-coded perceptions quantitatively to determine patterns, specifically with view to investigating where experiences of Amerasians living in the US differ statistically from those living in Vietnam. This is complemented with a qualitative analysis of the accompanying narratives. Vietnamese respondents indicated more frequently that experiences were affected by economic circumstances than their US counterparts, and their identified negative experiences were significantly more strongly linked to poverty. Furthermore, Vietnamese respondents relayed that their desire to explore their biological roots was more prominent than US based participants, and they indicated more strongly than US counterparts that their biological parentage impacted their identity. In contrast, US respondents felt that their parentage impacted their physical and mental health in addition to impacting their identity, and they more strongly linked negative experiences in their narratives to their ethnicity.

Introduction

When foreign troops withdrew from Afghanistan in August 2021 (Aljazeera, 2021; Brockell, 2021), images of desperate civilians seeking safe passage out of Kabul in the final days and hours of American/Western protection from a regime that was feared by many not least because of their association with the United States (US)-led coalition in the country, the scenes at the airport were reminiscent of the widely-publicized images of the fall of Saigon almost half a century earlier (BBC, 2021; Guardian, 2021). When foreign troops withdrew from Vietnam in April 1975 after years of engagement and conflict, the soldiers not only left behind a war-torn country; they left behind people with whom they had formed personal and sometimes intimate relationships, a large number of which had resulted in children being born (McKelvey, 1999).

Locally referred to as Bui Doi, Dust of Life1 (Taylor, 1988; US General Accounting Office, 1994, 1–3), the American GI-children, born to Vietnamese women, are among the many groups of children born of war (CBOW), children fathered by foreign soldiers and born to local mothers (Lee et al., 2021, 14–16).

That CBOW have often been exposed to significant childhood and life-long adversities, have frequently experienced discrimination and stigmatisation, and display above average mental and physical ill health, has been well established in recent research (Carpenter, 2007; Glaesmer, 2012; Seto, 2013; Lee, 2017). It is reasonable to assume that hardships experienced by CBOW are particularly pronounced where the end of a given conflict does not present the end of the animosity between the former enemies. The Vietnam War, or the American War as it is often referred to in Vietnam (Rosen, 2015) had been an ideological as much as a military or political conflict. The US Government expected those ideological and political divisions to persist for years to come and therefore association with the ideological foe, the US, was expected to be disadvantageous, if not outright dangerous for those directly linked to the US, among others those visibly linked to American GIs – first and foremost GI children born to local Vietnamese women. Based on this risk assessment, towards the end of the war the US evacuated Vietnamese-Amerasians, as part of the so-called Operation Babylift, a government-backed initiative in which several thousand young children were brought to America, Canada and Europe (The United States Agency for International Development, 1975). This was followed by further waves of migration from Vietnam to the US, as part of the Orderly Departure Programme of 1979 (Kumin, 2008) and the Amerasian Immigration Act (Amerasian Immigration Act, 1982).

By far the most significant migration in terms of numbers, was the so-called Amerasian Homecoming Act of 22 December 1987, which allowed Amerasians (defined as children of American citizens born between January 1, 1962, and January 1, 1976) and their relatives to apply for immigration to the US. Approximately 25,000 Amerasians and between 60,000 to 70,000 of their relatives had immigrated to the U.S. under the Amerasian Homecoming Act by 2009 (Lee, 2015; lii), and it is estimated that the number of Vietnamese Amerasians who have remained in Vietnam is in the region of 400–500 only (Lind, 2016).

Understanding the life courses of Vietnamese Amerasians will enhance our understanding of the challenges of mixed-race children born of war being raised in post-conflict settings where the end of a war does not bring the end of hostilities between the former enemies. Some publications, often of biographical or autobiographical nature, have thrown light on the living conditions of Vietnamese Amerasians (DeBonis, 1994; Bass, 1996; Hayslip, 2003; Yarborough, 2006; Sachs, 2010); and in the 1990s research relating to psychosocial outcomes and mental health pathologies of Vietnamese Amerasians (Felsman, 1989; McKelvey et al., 1992; McKelvey and Webb, 1993, 1995, 1996; Bernak and Chung, 1997) raised awareness of the health challenges faced by those residing in the US. But no comprehensive data has been collected about experiences of Amerasians in Vietnam, about their mental and physical health outcomes or socio-economic circumstances. Most of our knowledge about such experiences in Vietnam is based on records of Amerasians who migrated to the U.S. (Valverde, 1992; Long, 1997; Yarborough, 2006; Lamb, 2009). Notwithstanding the possible selection bias of Vietnamese Amerasians who migrated to the US, according to a 1994 post-migration survey, more than 70% of Amerasians interviewed reported experiences of discrimination in Vietnam, including difficulty in accessing schooling, negative attitudes by teachers, grade discrimination and persistent offensive teasing by peers (US General Accounting Office, 1994, 71). Similarly, post-migration reporting focussed on the discrimination in Vietnam and the contrasting greater opportunities for Amerasians in the U.S. (Taylor, 1988; Valverde, 1992; Gaines, 1995a,b; Sachs, 2010). Yet, autobiographical writing and further research suggest that integration into the father's home country for those who migrated later in life was also challenging. Among the difficulties encountered were the lack of acceptance of Amerasians among the Vietnamese communities in the US, as well as experiences of racism encountered in the United States more generally, the disappointments of not being able to locate biological fathers and their families as well as significant economic hardships after resettling in a foreign country, exacerbated by educational and linguistic disadvantages (DeBonis, 1994; Bass, 1996; Yarborough, 2006, chapters 7-9, Ranard and Gilzow, 1989, 1-3).

The aim of this paper is to provide a comparative analysis of the experiences of Vietnamese Amerasians in both the US and Vietnam. To achieve this we used SenseMaker®, a mixed-methods quantitative-qualitative data collection tool, to collect narratives about experiences of being a Vietnamese American in both the US and Vietnam; the collected storeys were then self-interpreted by study participants to “make sense” of the shared experiences (Brown, 2006; Kellas and Trees, 2006). This paper identifies statistically significant differences in the quantitative data collected in Vietnam and the US and analyses them drawing on the accompanying qualitative data.

Methods

Sensemaker

Sensemaker is a mixed-methods data collection software and research tool developed by Cognitive Edge (2017). Its narrative-based approach involves the collection, in response to their choice of open-ended prompting questions, of short narratives related to a particular phenomenon (here the experiences of Vietnamese Amerasians). These narratives generate qualitative data in the form storeys collected as audio or text files. Following this recording, participants are asked to self-interpret their narratives by responding to a series of pre-defined questions relating to the shared experiences, which are quantitatively coded. Based on complexity theory (Turner and Barker, 2019), SenseMaker uses pattern recognition to understand people's experiences in complex, ambiguous and dynamic situations by identifying common themes. As participants interpret their own narratives using a series of pre-defined questions, the researchers' interpretation bias is reduced. Collectively, the participants' self-interpreted narratives present a nuanced picture of the investigated phenomenon (Girl Hub, 2014).

Research Partners

Our cross-sectional, mixed qualitative-quantitative two-country study was conducted in 2017 (Lee and Bartels, 2019). Data collection in Vietnam occurred in April and May in collaboration with the Department of Anthropology at the University of Social Sciences & Humanities at the Vietnam National University in Ho Chi Minh City. Further, the research was facilitated by the Vietnam chapter of Amerasians Without Borders, a U.S.-based non-profit organisation of Vietnamese Amerasians who support Amerasians, among others through facilitation of DNA tests to support immigration into the US Data collection in the U.S. occurred from February to July of the same year in collaboration with the US chapter of Amerasians Without Borders.

Participant Recruitment

Individuals from the age of 11 were eligible to participate. To capture a wide range of perspectives about the life experiences of Amerasians, we targeted a variety of participant subgroups for recruitment. These subgroups included Amerasians themselves, mothers and spouses of Amerasians, biological fathers and stepfathers of Amerasians, adoptive parents of Amerasians, children of Amerasians, other relatives of Amerasians, and community members in locations where Amerasians lived at the time of interview.

Interview sites in both countries were chosen purposively based on existing data about where Amerasians were thought to be living. In Vietnam, the selected locations were Ho Chi Minh City, Dak Lak, Quy Nhon, and Da Nang. In each of these four study locations, Amerasians Without Borders organised group meetings. Members and their relatives were invited to a designated location to meet with the interview team. The study was introduced to potential participants, and after consenting to participation, Amerasians and their families were asked to privately share a storey about the experiences of Amerasians in Vietnam and to then interpret the storey by completing the SenseMaker survey. The shared experiences could be a first-person storey or a storey about an Amerasian family member.

In the U.S., face-to-face interviews were conducted in San Jose California, Portland Oregon, Santa Ana California and Chicago Illinois. Interviews were pre-arranged through contacts within the Amerasians Without Borders social network, and interviewers travelled to each of the four study locations to meet participants. Interviews in Chicago were arranged to coincide with the Amerasians Without Borders annual meeting in July 2017. In addition to face-to-face interviews, a link to the browser-survey offered in the U.S. was posted on Facebook and Twitter by Amerasians Without Borders, and it was emailed to their members.

Furthermore, in the U.S., data collection was supported by Operation Reunite2, an organisation which aims to raise awareness of the Vietnam War and to provide support to Vietnamese war babies who had been internationally adopted in the U.S. (and other countries like the U.K., France and Australia) among others through Operation Babylift. Information about the study was shared through the organisation's social media platforms and those platforms were used to distribute the browser link to Amerasian children who had immigrated to the U.S.

Survey Instrument

The SenseMaker survey was drafted by the authors iteratively in collaboration with an experienced narrative capture consultant and was reviewed by Vietnamese and Amerasian partners. After selecting one of two open-ended prompting questions and sharing a storey about the life experiences of an Amerasian in Vietnam or in the US, participants were asked to interpret the Amerasian's experience by plotting their perspectives between three variables (triads) or by using sliders (dyads). Subsequently, multiple-choice questions were used to collect demographic data and to help contextualise the shared storey (e.g., emotional tone of the storey, how often do the events in storey happen, who was the storey about, etc.).

The survey was drafted in English, translated to Vietnamese, and then back translated by an independent translator in order to resolve any discrepancies. The Vietnamese and English versions of the survey were uploaded to the Cognitive Edge secure server for use in Vietnam and the US, respectively. Both surveys were reviewed for errors and corrections were made prior to initiation of data collection.

In both countries, data was collected using the SenseMaker app on iPad Mini 4's; in the US, in addition a browser version of the survey was made available. This browser survey, which was identical to that on the SenseMaker app, was circulated through various social networking platforms of Amerasians Without Borders and Operation Reunite.

Data Collection Process

In Vietnam, the data collection team comprised eight interviewers from the Department of Anthropology at the University of Social Sciences & Humanities at the Vietnam National University in Ho Chi Minh City. Members of the team were two faculty members and six graduate students. Immediately prior to data collection, all interviewers participated in a two-day training workshop on narrative capture research ethics, use of an iPad, how to approach participants and obtain informed consent, specific survey questions with multiple role-playing sessions, data management, adverse events, and program referrals. In Vietnam, all data was collected on the SenseMaker app using iPad Mini 4's. Collected data was stored on the iPad until it was possible to connect to the Internet, at which time it was uploaded to Cognitive Edge's secure server. During the upload process, data was automatically deleted from the tablet.

In the U.S., two interviewers identified through Amerasians Without Borders collected data. Both self-identified as Amerasian. Prior to data collection they received individual training on the above topics. During data collection at the Amerasians Without Borders annual meeting in Chicago, they were supported by three additional fully trained interviewers, including a faculty member, a student, and a volunteer (female and male respectively). The browser survey used in the U.S. was posted on Facebook and Twitter by Amerasians Without Borders. Participants completed the survey independently and uploaded the data directly to the Cognitive Edge secure server.

At each of the interview locations, potential participants were identified through the social networks of Amerasians Without Borders. Interviewers introduced the study using a script, and when an individual expressed interest in participating, the interviewer and participant chose a private location for completion of the survey. Participants were asked to tell a storey about the experiences of an Amerasian based on their choice of one of two storey prompts. Shared storeys were audio-recorded on tablets and participants then responded to a series of pre-defined questions. If the participant was uncomfortable having their voice recorded, the interviewer listened to the participant's storey and subsequently recorded the storey in their own voice on behalf of and in the presence of the participant. On completion of the survey, participants were asked if they would like to share a second storey. Several participants shared more than one storey; therefore the number of shared storeys exceeds the number of unique participants. Data collection in Vietnam was overseen by a graduate student who reviewed uploaded data on a weekly basis and performed quality assurance cheques.

Ethical Considerations

All interviews were conducted confidentially, and no identifying information was recorded; therefore the data were anonymous from the start. Participants were asked specifically not to use actual names or any other identifying information when relating their storeys. In cases where such identifying information was recorded, the name or other identifying information was not transcribed. In the face-to-face interviews, informed consent was explained to the participant prior to the interview in either Vietnamese (in Vietnam) or English (in the U.S.); consent was indicated by tapping a consent box on the handheld tablet. In the browser version, the same information was provided prior to entering the survey. Participants read the explanations of informed consent in English and clicked the consent box to indicate their willingness to participate. Only upon giving consent could a participant commence the survey. No monetary or other compensation was offered but expenses incurred to travel to the interview were reimbursed and refreshments or a light meal were provided. The University of Birmingham's Ethical Review Board approved this study protocol (Ethical Approval ERN_15-1430).

Analysis

SenseMaker data were exported to Tableau (V.2020.4) where collective plots (with all participants' responses on the same figure) were analysed visually to identify data patterns such as clusters of responses in one extreme or another, outliers, and so on (Cognitive Edge, 2017). Triad and dyad data were disaggregated based on whether the data had been provided by a participant in Vietnam or the US.

Where, based on visual inspection, the pattern of responses appeared to differ between both groups, triad and dyad questions were selected for statistical analysis. For the dyad data, graphically generated as histograms and presented below as violin plots, SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics V.26.0.0.0) was used to analyse the collective areas under the bars for each subgroup with the Kruskal-Wallis H test and χ2 tests to determine if the bar areas were statistically different between groups (Webster and Carroll, 2014; Webster, 2015). Dyad distributions of responses are presented as violin plots to illustrate the different response patterns, with an asterisk indicating the overall mean for each sub-group.

For the triad data, R Scripts (R V.3.4.0) was used to generate geometric means for both the Vietnamese and US subgroups. R Scripts was also used to generate 95% confidence intervals, which are presented as confidence ellipses around the geometric means (DeLong, 2016a,b). Two geometric means were deemed statistically different if their 95% confidence ellipses did not overlap.

After patterns of perspectives were identified in the quantitative data, accompanying narratives were reviewed to facilitate interpretation of the statistical findings. A series of representative quotes were then chosen for inclusion to illustrate the main quantitative results.

Participants' responses on the storey interpretation (i.e., triads dyads) generate quantitative data in the form of plots, where clusters reveal widely held perspectives on particular issues. If a sufficiently large volume of self-interpreted storeys is captured, SenseMaker helps to ascertain patterns across various subgroups offering insights into mainstream, alternative and diverse perspectives on a topic of interest. These quantitative data are contextualised and interpreted in conjunction with the accompanying narratives, thereby offering a rich mixed methods analysis. The results presented here are focused on the implementation of the research in both Vietnam and the U.S. among three different cohorts of Amerasians3. Quantitative and qualitative data will be presented separately.

Results

A total 319 self-interpreted storeys were collected from 231 unique participants in Vietnam and 58 storeys were collected from 55 unique participants in the U.S.

Demographics

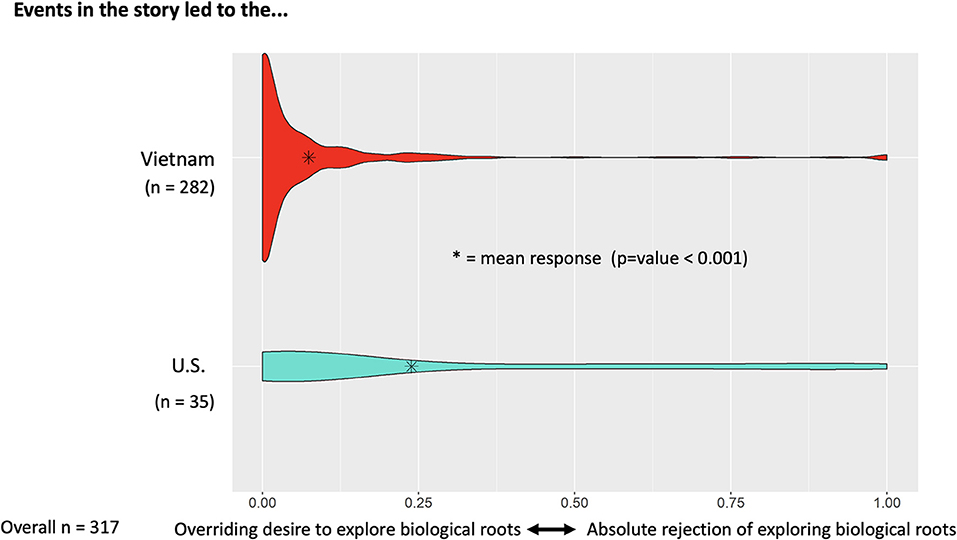

A total of 319 participants were recruited in Vietnam from 231 unique participants and 58 in the U.S. from 55 unique participants. Overall, a majority of participants identified as female (55.70%), were married or living with a partner (72.94%) and shared a narrative about themselves (66.31%). Over half of all participants either had no formal education or had completed only primary school (55.44%). There was a roughly equal split of positive (32.63%) and negative (33.42%) narratives, and almost a third of participants were frequently active in Amerasian support groups (31.03%). Further demographic details are provided in Table 1 disaggregated by participants' location.

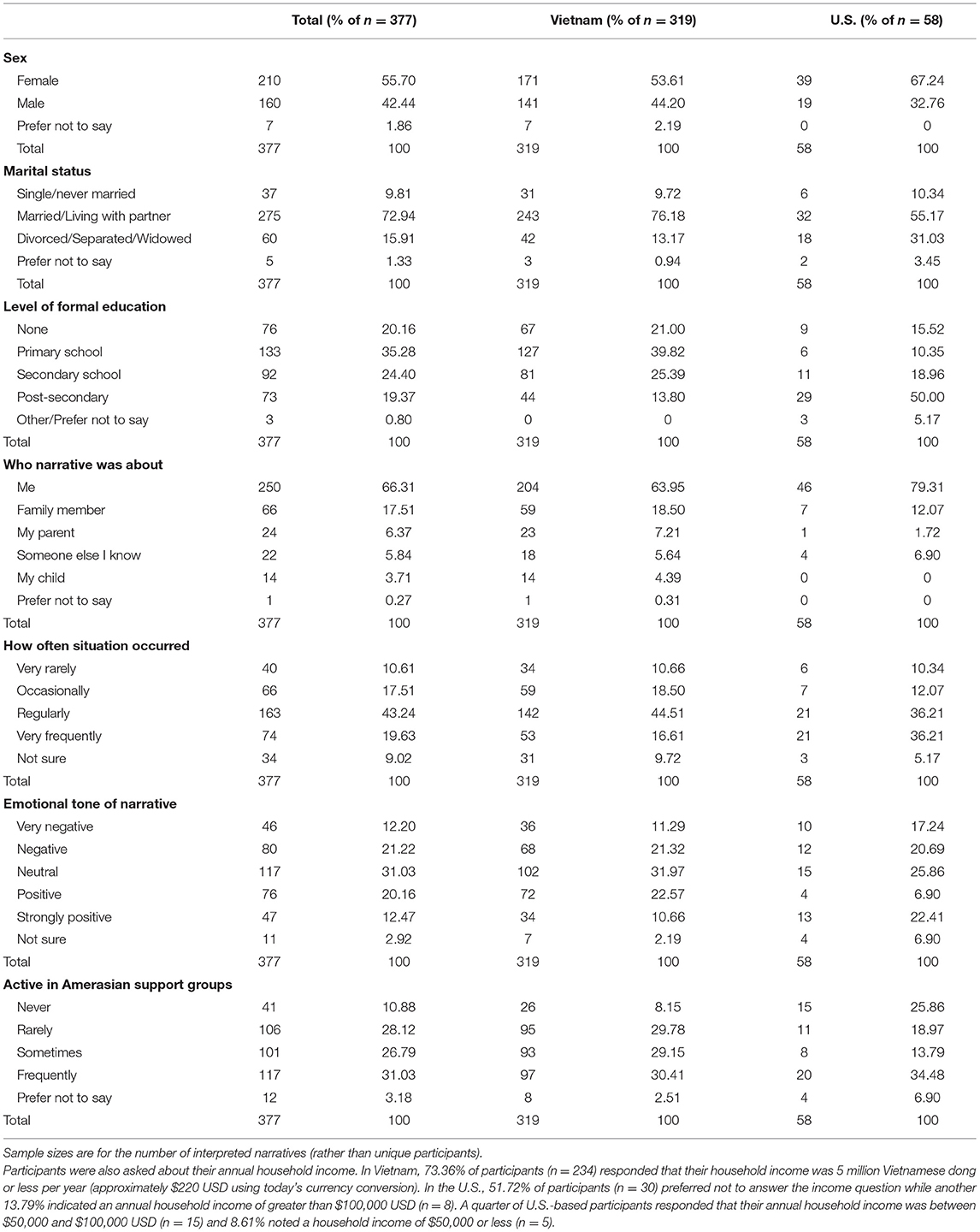

When asked what was responsible for negative experiences in the shared narratives, participants in both Vietnam and U.S. indicated that poverty was a strong contributing factor in comparison to ill health and stigma. As shown in Figure 1, this was particularly true for Vietnam participants with their responses being statistically different from those of U.S. participants.

Figure 1. Triad asking about links to negative experiences shared in participants' narratives. The overall geometric mean is provided on the left with individual geometric means for Vietnam and the U.S. provided on the right. Responses were statistically different between the two countries as demonstrated by the non-overlapping 95% confidence ellipses, with participants in Vietnam indicating that negative experiences were more closely linked with poverty.

Ethnicity

Self-interpreted narratives from Amerasians in Vietnam and the United States indicated the importance of both their ethnicity, understood as a sense of personal belonging, and their racial provenance, visible in their distinct physical appearances that, due to socially-constructed processes, led to those individuals being considered as a separate group in a given context.

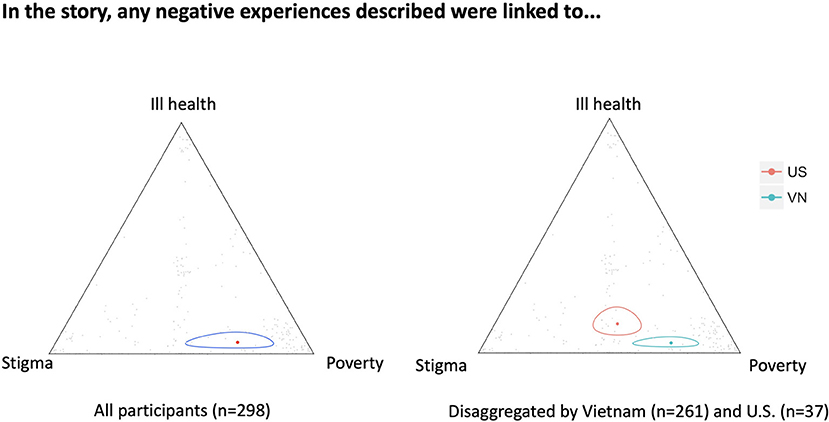

The first presented triad asked participants to consider whether the experiences shared in the storey were affected by (i) domestic arrangements, (ii) ethnicity, or (iii) economic circumstances. As visualised in Figure 2, the geometric mean for all respondents was predominantly in the direction of ethnicity, approximately equidistant from economic circumstances and domestic arrangements. When disaggregated by location of data collection, respondents from the US indicated that Amerasian experiences were more strongly about ethnicity than those narrated and interpreted by Vietnam-based participants.

Figure 2. Triad asking about what affected the experiences in the shared narrative. The overall geometric mean is provided on the left with individual geometric means for Vietnam and the U.S. provided on the right. Responses were statistically different between the two countries as demonstrated by the non-overlapping 95% confidence ellipses, with participants in the US indicating that negative experiences were more closely linked with ethnicity.

While Amerasians in both countries were visibly different to the majority population, with regard to their racial background, Amerasians living in the US more often associated their negative experiences directly with their appearance as a mixed-race person, even if this association in many cases related to experiences of their childhood and youth in Vietnam.

With this getting line position, I knew that my friends differentiated between me and them because I am an Amerasian. My skin colour was different from theirs. Then when in class, no matter how good I was doing, I didn't get fair treatment from the teachers as well as by other classmates, especially those whose parents were communists.

NarrID1003; female, in the US, married, completed secondary school.

Likewise, it was this appearance and the association with ethnicity and “mixed blood” that Amerasians residing in the US remembered vividly even when those experiences of stigmatisation and discrimination happened in their youth in Vietnam. One Amerasian surveyed in the US recalled being falsely accused of stealing as a child in Vietnam, when she picked up a piece of fabric that she believed had been thrown away by a neighbour.

I thought it was thrown away. But when the neighbour saw this, she accused me of stealing her fabric, “you the little stealer.” She shouted at me “Didn't you mom teach you? She who bore you but didn't know how to teach you. She who bore you the Amerasian with mixed up blood didn't know how to teach you, huh? You who have different types of blood.”

NarrID1012; female, in the US, single, completed post-secondary education.

In both narratives above, the narrators associated ethnicity not merely with their own sense of belonging (or lack thereof) to a particular culture or tradition, but they felt strongly about the impact of their physical appearances or their “mixed up blood” in the construction of their “not belonging”.

Ethnicity, however, was felt to be a burden even when it was not associated with discrimination and stigma. Being visibly different singled Amerasians out and participants reported feeling isolated as a result. One participant, who had been transracially adopted at the end of the war, described how this inner conflict was only resolved when visiting her native Vietnam two decades after being adopted in the US.

I grew up longing to be what I wasn't and had no connexion to anyone like me (Asian mixed race Vietnamese short). I internalised self-hatred and struggled to feel good about myself. When I finally returned to Viet Nam in 1996 I felt I had finally come home. I felt at ease and as though I had found my people. I finally felt good enough and whole.

NarrID 1500; female, in the US, married, completed post-secondary education.

Exploring Biological Roots

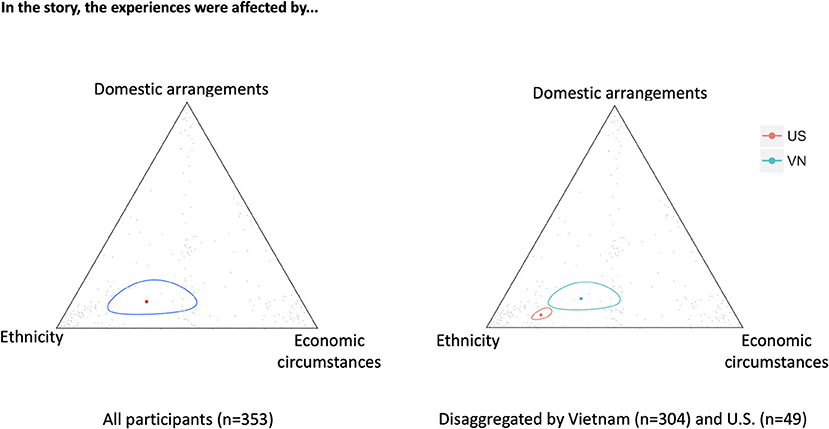

A dyad question asked to what degree the events in the shared narrative influenced the participant to want to explore his/her biological roots. The results are illustrated in Figure 3 and show that Vietnam participants were more likely to indicate a strong desire to explore their biological roots.

Figure 3. Dyad asking how events in the shared narrative influenced desire to explore one's biological roots. Dyad asking how the events in the storey influenced the participants' desire to explore their biological roots. Asterisks indicate the overall mean for each sub-group and highlight that Vietnam participants indicated a stronger desire to explore their biological roots (p < 0.001).

Many Amerasians knew very little about their biological fathers and multiple participants described how families had destroyed letters, photos and other potentially identifying items to avoid persecution in post-war Vietnam for having been associated with the American enemy. Loss of such letters and photos often proved detrimental when Amerasians were applying for immigration to the US as evidence of parentage no longer existed.

My mom told me that after he had gone back to his fatherland in 1970 he still sent us a stipend. Unfortunately, afraid of troubles, she burned all stuffs even letters related to my dad after the war… during the interview, they asked for our supportive evidence of which we had nothing. All burned. Since then, I was really disappointed because I am an Amerasian for real but they didn't accept it… But the thing is I just want to search for my roots.

NarrID54; female in Bẽn Tre, married and without formal education.

Not knowing their fathers had a profound psychological impact on many Amerasians, with many participants describing life dissatisfaction, sadness, frustration, and abandonment. The following man attributed his sadness to not knowing his biological family.

… people say that having a family satisfies us, and there would be no unhappiness, no difficulties in life. In my case, the fact about family and the fact that I have no father, there is a connexion between them. In the society, when a person has a family, he is happier. I don't have a family, so I'm not happy.

NarrID16; male in Ninh Thuận, married with some primary school education.

Some participants also described a sense of abandonment by their fathers and in other cases, felt unloved because of being abandoned, which resulted in a strong desire to be reunited with their fathers. For example, a male participant in Dak Lak explained, “For Amerasians, the most aspiration is to go to their fatherland. They seem lost in this living environment. They often suffer abandonment, discrimination and lack of love.” (NarrID219)

In addition to wanting to know their biological origins, some participants believed that finding their fathers would provide opportunities to live a better life in the U.S., as this female participant reported, “I do not have a father, so I have to work hard a whole day without any supports. I wish I could meet my father in the United States so that he can take care of me and give me a better life.” (NarrID163)

The desire for a better life was also extended by Amerasians to their children with some explicitly stating that they wanted to reunite with their biological fathers to make life easier for their children. One male participant shared, “I heartily wish I could go to America to reunite with my father so that my children's lives would be better. For me, I do not have any wish for myself.” (NarrID77)

Yet other participants were clear that their desire to be reunited with their fathers was focused on emotions and on feeling loved, as the following participant explained.

I hope that because we Amerasians are all grown up now, we are not young anymore, so we just want to find our fathers so that we have some love. It's fine that they don't even have to take us with them. We don't need it anyway. We've already been through hardship. What we need is to find our relatives.

NarrID317, male in Ho Chi Minh City, married with some primary school education.

This participant acknowledged the challenges he has faced as an Amerasian in Vietnam but was not looking for a higher quality of life or for an easier life. For him, it was about emotional needs. Other participants were also explicit in stating that their desire to know their father was not motivated by wanting financial support or a better life but instead was about knowing ones' roots and origins. The following participant shared her perspective that all Amerasians have the same desire to trace their biological roots.

… I have been dying to meet my father. I never wish that my father would change my life or make me better-off when I meet him. I am not afraid of working, and thus I do not necessarily want to go to some other places [go to the US]. This is my aspiration. No matter how miserable Amerasian people like me were, we wish we could find out our biological fathers. We all have the same thoughts; we want to trace our origins.

NarrID65; male in Bình Duong, married and had completed primary school.

Identity

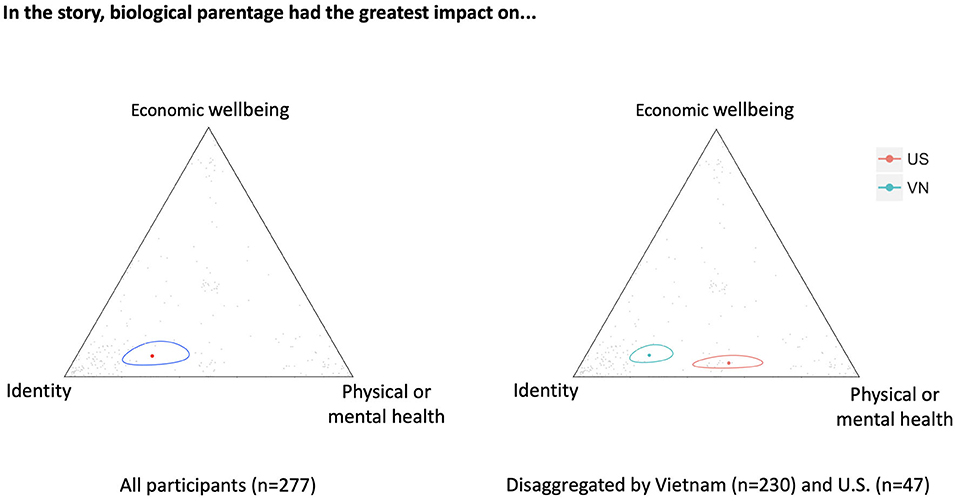

Participants asked about the degree to which biological parentage had impacted economic wellbeing, identity, and physical or mental health. As illustrated in Figure 4, the focus was predominantly on identity especially in Vietnam.

Figure 4. Triad asking about the impacts of biological parentage. The overall geometric mean is provided on the left with individual geometric means for Vietnam and the U.S. provided on the right. Responses were statistically different between the two countries as demonstrated by the non-overlapping 95% confidence ellipses, with participants in Vietnam indicating more strongly that biological parentage impacted their identity.

Some participants expressed a sense of not knowing who they are because of not knowing their biological parents. The following participant was fortunate to have had a loving adoptive family but as an adult, he was left with questions about his identity.

I do not know who I am. My mother left me to a nanny. In the liberation year of Vietnam, the nanny was afraid of having an Amerasian child in her family, so she gave me to a man whom I called uncle [X]… Although I am an adopted child, I was loved by my family members very much. They loved me as their own children because they raised me since I was a baby. I had no difficulties living with my adopted family. My life was easy… My nanny gave me to uncle [X] and he raised me ever since. I don't know who I am.

NarrID299; male in Dong Nai, single and completed primary education.

Not knowing one's biological parents had practical implications for some Amerasians when it came to inheritance and land rights. The following female participant could not inherit property because she was “just an adopted daughter.”

She was the youngest child in her adopted family but she did not get any inheritance such as house, agricultural land and the like because she was just an adopted daughter.

NarrID314; female in Bình Thuận, married with some secondary school education.

The importance in Vietnamese society of knowing one's roots and identity was clear. One female participant recalled that whenever she tried to attend school her neighbours and classmates would say, “Don't allow her to go to school. She is an Amerasian. We don't know her roots.” (NarrID165) Another participant shared his experience that without a father, he was looked down upon in Vietnamese society and was presumed to have not been raised properly.

I wish I could find my biological parents. If someone does not have parents, they will be looked down by surrounding people. Although no one wants a life like me, I still accept it because there is no choice for me. They often say that I do not have a father, it means that I was not brought up very well. They also call me “Amerasian”. The reason of quitting school up was that I was called Amerasian or a fatherless child by my classmates, and thus I was so upset and decided to give up my schooling.

NarrID249; married male in Da Nang, married and without any formal education.

For Amerasians who did not know their mothers or their fathers, the sense of missing identity was often compounded.

I wish I can find and meet my father or mother. I have been living with my adopted mother since I was one month old. So, I do not know where my mother is to find her. I heard that my father was a soldier. He was stationed in Long Binh, Dong Nai province. I wish I could find my father in the future.

NarrID284; male in Da Nang, married and without formal education.

For Amerasians who did not know either parent, it was usually exceedingly difficult to provide the documentation necessarily to apply for immigration to the U.S. The following participant describes his experience with the application process.

They asked me to give evidence about my mother with a picture. I answered that I did not have all these things. How could I have such a thing. I just don't have any photos of my blood parents. I just know that I am a Kinh orphan…They just needed my mother's photos, my father's photos and these are exactly what I don't have.

NarrID136; male in Dak Lak, married and without formal education.

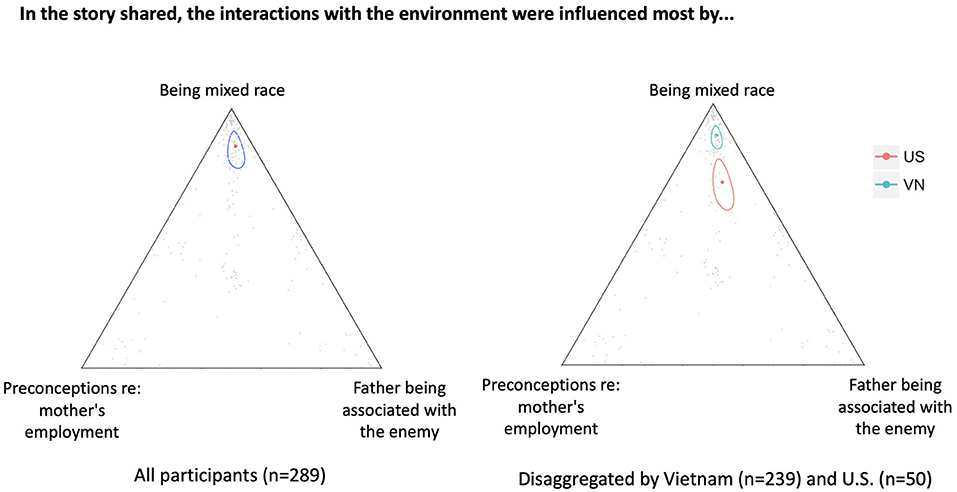

Stigma Due to Being Mixed Race

Participants in both Vietnam and the U.S. spoke about stigmatising attitudes and behaviours experienced due to being Amerasian. One triad question asked participants about influences on interactions with the environment and most participants responded strongly towards being of mixed race, as shown in Figure 5. This trend towards mixed race was particularly strong in Vietnam.

Figure 5. Triad asking what most influenced interactions with the environment. The overall geometric mean is provided on the left with individual geometric means for Vietnam and the U.S. provided on the right. Responses were statistically different between the two countries as demonstrated by the non-overlapping 95% confidence ellipses, with participants in Vietnam indicating more strongly that interactions with the environment were influenced by being mixed race.

Some Amerasians reported that discrimination based on being mixed race started within the family and from the time of birth. One participant in Da Nang explained the reaction to her own birth, “After I was born, my grandma wanted to give me away because I was an Amerasian, but mom rejected; as the result, she was expelled out of her house.” (NarrID260). Another participant explained the circumstances into which Amerasians were born in Long Thanh.

And as you've already known, here in Long Thanh, if people gave birth to Amerasians they would throw them into trash. Yeah, I knew one case when someone gave birth to an Amerasian, they threw it away in a trash bin and a woman picked the child then raised it. That's how it normally goes.

NarrID210; female in Dồng Nai, single and completed primary school education.

Amerasians experienced emotional abuse because of being mixed race and having an American father. One male participant reported that people called him “mixed race person” rather than use his real name, “I am an Amerasian. Nobody knows what my name is. People call me ‘Lai' (literally, mixed race person) instead of my name.” (NarrID214) Another participant experienced physical abuse because of being mixed race.

In the past, I only had my mother, and lived with my stepfather. However, they did not love me and called me Amerasian. They even beat me ruthlessly.

NarrID256; female in Quàng Nam, widowed and without formal education.

Stigma and discrimination based on having American paternal ancestry significantly impeded the ability of most Amerasians to attend school. A female participant described her experience of being forced out of school.

Other kids kept calling me “the American imperialist” and prevented me from studying. They hit me every time I came to school… You see, the dream of my whole life was to have a chance to go to school, but see what I got? Discrimination prevented me from pursuing my dream.

NarrID113; female in Dak Lak, widowed and without formal education.

A discrimination hierarchy was evident with more extreme stigmatising attitudes and behaviours directed towardss Amerasians who had Black fathers. The following participant shares her mother's experience as an Amerasian with a Black father.

Everyone in my neighbourhood has known mom for a long time. They knew she was a Negro. Some played with her, others despised. It would be better if she were a white skin half-blooded; the Vietnamese always have that kind of discrimination against the dark ones. There were many people who despised and hated my mom in the village. They sometimes expelled her. Even my family and my relatives hated her. They said she had black skin, she was a hybrid, why didn't she go to America.

NarrID164; male in Dak Lak, some post-secondary school education.

Ongoing stigma and discrimination resulting from being mixed race naturally impacted the mental health and wellbeing of many Amerasians and some participants reported feeling suicidal and having had suicide attempts.

In general, my life is so hard, so difficult. Others treated me like nothing. They called me that Amerasian, this Amerasian and so on. I was miserable. I felt miserable with my life. I wanted to commit suicide sometimes. I tried committing suicide once by taking pills, but one Korean found and took me to the hospital. Otherwise, I would have died many times.

NarrID119; female in Gia Lai, married with no formal education.

Narratives about stigma occasionally ended with participants aspiring to be reunited with their fathers as a way of removing themselves from the stigmatising environment. The following participant seemed to indicate that he saw two potential routes to end the suffering experienced due to being mixed race: suicide or being reunited with his father.

…he has also been discriminated against by other people, thinking he is a foreigner or the like… Sometimes he feels depressed. When he returns home after work he cries and wants to commit suicide sometimes. I gave him a lot of advice, but he said that if his search for his father results in failure, he would rather overdose himself to death than live in Vietnam.

NarrID129; female in Dồng Nai, married with some secondary school education.

Many Amerasians were married, and an earlier analysis suggested that having happy marriages and families of their own was often a source of strength and satisfaction for Amerasians in Vietnam (Ho et al., 2019). However, the current analysis illustrates how discrimination around being Amerasian mixed race sometimes made it more difficult to find a partner. One male participant reported, “I have an Amerasian wife. When we got married, I heard many bad comments from my neighbours regarding her. They told me I shouldn't marry her, a Negro Amerasian.” (NarrID148) In the following narrative, another participant describes her mother's reaction when she got engaged to an Amerasian man.

My mother called and said “I banned you from dating him! If you do, then get out of my house.” “He is an Amerasian, living with him and nobody will give you any respect! You want to live with him? Go with him then. Don't even think about coming home!”

NarrID130; female in Dồng Nai, married with some secondary school education.

Several Amerasians noted that while stigma and discrimination were severe in their early lives, after the 1987 Amerasian Homecoming Act allowed Amerasian children and their relatives to apply to immigrate to the U.S., there was generally more acceptance of Amerasians. A male participant in Quy Nhon reflected on this change in his life, “when there was a departure program for Amerasians, that was when I started to fit in the life with the Vietnamese” (NarrID143). Another participant similarly described how he became valued in society after the Homecoming Act.

It was very difficult to live in a country where people discriminated against us. I felt like I was a prisoner. People used discriminating words when talking to me… After the Amerasian program, I realised that my life had changed a lot. People in my society turned to value me…No one dishonoured me because I was an Amerasian. My life has become comfortable.

NarrID142; male in Quy Nhon, divorced and completed secondary school education.

Children of Amerasians were also seemingly affected by discrimination based on being mixed race and having American ancestry. One male participant reported the following situation for an Amerasian he knew, “Now he has three children, all having formal education but none of them are able to get a job in government organisations due to his origin. So yeah, his origin does affect his descendants.” (NarrID147) Another participant explained what happened when her son was applying for military school in Vietnam.

I asked the uncle if my son had any chance to enter that military school. He said no because they would cheque and conclude that his background is not good. I asked him how come. He said it was because of my son's father. My son's father was an Amerasian, so his background was bad.

NarrID232; female in Khánh Hòa, married and completed secondary school.

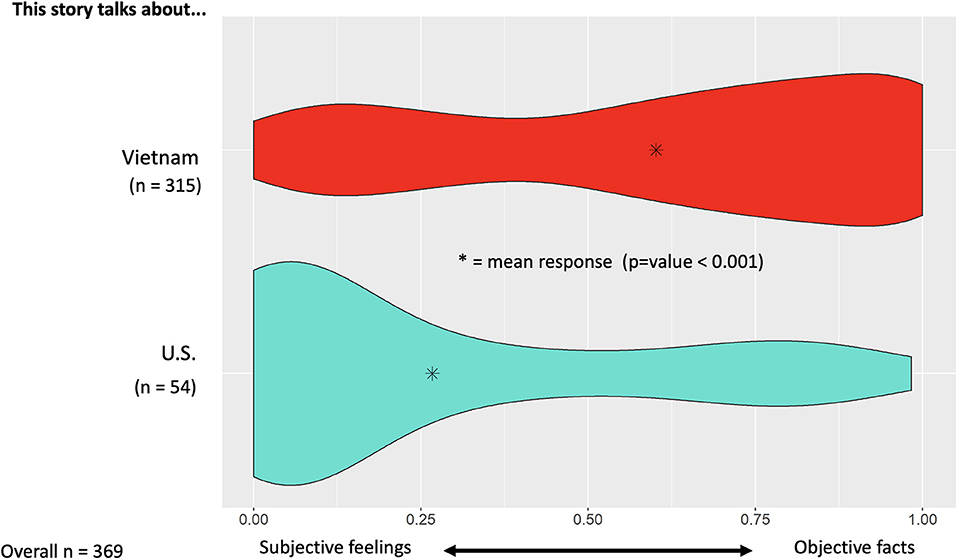

Subjective vs. Objective

A dyad question asked participants to comment on whether the shared experience was about subjective feelings or about objective facts. As Figure 6 demonstrates, participants surveyed in the US more frequently interpreted their storeys as being about subjective feelings than those surveyed in Vietnam.

Figure 6. Dyad asking whether the storey was about subjective feelings or objective facts. The storey talks about. Participants surveyed in the US more frequently signified the storeys as being about subjective feelings than those surveyed in Vietnam. Asterisks indicate the overall mean for each sub-group and highlight that Vietnam participants indicated a stronger desire to explore their biological roots (p < 0.001).

A common sentiment expressed by Amerasians in the US was the feeling to be unwanted.

… at that time I felt unwanted, I felt bad about myself, because the way I looked made my brother not wanting to have me around. …

Things have changed a lot now, my brother's not the same person like he was, but that piece of it, how he made me feel, about myself I don't think I could forget.

NarrID 1050; female, in the US, single, never married, completed post-secondary education.

Another theme prominent particularly among Amerasians who had been transracially adopted at a young age and had never known their roots, culture, language or birth country, was the subjective feeling of not belonging and of feeling like an outsider.

I was transracially adopted into a white tall blue-eyed family in a predominantly white community in California. I grew up longing to be what I wasn't and had no connexion to anyone like me (Asian mixed race Vietnamese short).

NarrID 1500; female, in the US, married, completed post-secondary education.

I wasn't liked much. I didn't like me either. … I was ashamed of who I was when really deep inside I had no clue who I truly was. And still to this day not knowing what exactly happened or who are my parents do I have siblings etc etc......eats me up in side. It's a deep void that will probably never be filled. (57)

NarrID 1507; female, in the US, divorced/separated, some secondary school.

Discussion

The study's primary goal was to characterise differences in the perceptions of Amerasians in Vietnam and the United States about those issues that had most affected their lives. Significant differences were found in the following areas: poverty, ethnicity, the desire to explore one's biological roots, one's sense of identity, and the stigma associated with being of mixed race. These differences are all linked, directly or indirectly, to having foreign, typically non-Asian fathers, who abandoned them and their mothers in a country where their fathers were perceived as the enemy (McKelvey, 1999). Consistent with the literature (Valverde, 1992, 147; McKelvey, 1999, 47-51; Yarborough, 2006, 46) participants of African-American parentage faced very significant additional challenges and hardships. Amerasians were not only mixed-race, which was stigmatised in Vietnam, but were also left without a knowledge of their fathers' backgrounds, or ethnicity, which is central to a sense of identity and belonging. In Vietnam, the father is the key to an individual's future, bestowing not only a name, but also a sense of connexion to the present and the past and, often, opportunities for a more productive and prosperous life. In reviewing the narratives, the concepts of ethnicity, biological roots, identity, and mixed race are frequently intermingled and difficult to tease apart. Key to them all, however, was the participants' sense of being different and not belonging.

Poverty was a dominant theme for Amerasians in both Vietnam and the US. Among respondents in the US the poverty theme, however, was present less frequently as the overriding concern of the narratives than among Amerasians in Vietnam, and it appears from their narratives that their concerns about poverty were linked chiefly to their experiences while still in Vietnam. This can be explained by the fact that, as evidenced in the demographic data, significantly more respondents in the US completed secondary and post-secondary education, which would have enhanced their chances of securing higher paying jobs and thus their chances to escape from the trap of poverty that many of their counterparts who remained in Vietnam found themselves in still at the time of the interviews.

Ethnicity outweighed domestic arrangements and economic circumstances as a factor featuring prominently in the participants' narratives. Based on the narratives, ethnicity was associated with being of mixed-race and so the results of both will be considered here. Interestingly, Amerasians in the US reported ethnicity as significantly more important to their narratives than those in Vietnam. The opposite is true for valuation of being of mixed-race, where Amerasians in Vietnam reported significantly more difficulties. This finding, while counter-intuitive on the surface, can be explained for both subgroups of Vietnamese Amerasians, those adopted in the United States at the end of the War in the mid 1970s and those who immigrated to America following the Amerasian Homecoming Act. Narratives of adoptees who had grown up in America often without childhood contact to their birth country and little or no exposure to its language, culture and traditions, indicated the importance of ethnicity and of “reuniting” with their country of origin; this is consistent with recent research on coping strategies of Vietnamese adoptees and their strategies of family migrations (Varzally, 2017). For Amerasians who migrated to the United States in adolescence, the relative prominence of considerations of ethnicity may be explained by what Thomas (2021, 217), calls racialisation of Amerasians into American and Asian categories once they arrived in the United States.

The narratives of Amerasians both in Vietnam and in the United States reflect how powerful “looking different” to the majority population was in affecting Amerasians' lives. This is supported by prior reports of Amerasians' experiences (Felsman, 1989; Valverde, 1992; McKelvey, 1999). The desire to explore one's biological roots was an important feature identified in the narratives of both groups of Amerasians, but significantly greater for those still in Vietnam. This desire is understandable for people who do not know their fathers and, in many cases, also do not know their mothers. The destruction of photos, letters, and other documents after the end of the war out of fear that they might lead to punitive actions by the victors, left many with no concrete connexion to their past (McKelvey, 1999; Yarborough, 2006, 198). A sense of family is of central importance to people in Vietnam, who practise ancestor veneration and frequently have altars as centrepieces in their homes with photos of the deceased prominently displayed. There was a hope among those still in Vietnam, that if one were able to travel to the land of one's father, one might identify and connect with the father and his family. In some cases, it was hoped that this connexion might also lead to material wellbeing.

Akin to the desire to know one's biological roots was the importance of identity. In the narrative about the impact of biological parentage, identity outweighed economic wellbeing and physical or mental health. At the core of identity is having a sense of who one is. This is derived from family and connexion to a specific cultural tradition. It is also shaped by the reactions of others to oneself. There is no “Amerasian” family tradition in Vietnam, where most are members of the majority Kinh people, and being Amerasian and looking different than everyone else, branded one as being an outsider of diminished value. The importance of identity was weighted more heavily by participants in Vietnam than those in the United States, where one might justifiably argue that it was the home of one's father and that he had served in the nation's military.

One's interactions with the environment were strongly weighted towards being mixed race, especially in Vietnam, outpacing the mother's employment or the father's association with the enemy. This was especially true for those with darker skin, which is stigmatized in Vietnam (470-473). Our data supports the phenomenon reported in the literature, namely that stigmatisation of Amerasians was amplified for those of African American parentage.

The study's major limitation is the marked underrepresentation of Amerasians in the US. While the study was well publicised, especially through the organisation Amerasians Without Borders, there was a perception that the study organisers included “Communists.” This was related to the participation in the study by a university in Ho Chi Minh City. Participation by Amerasians in Vietnam was, on the other hand, very strong and likely represented a large minority of the Amerasians still living there.

The qualitative data points to significant and sustained adversities experienced by Vietnamese Amerasians of African-American parentage. While such discrimination has been reported anecdotally, a systematic intersectional analysis of Vietnamerican discrimination experiences both in the United States and in Vietnam remains an important research gap.

The study also has several notable strengths. To the best of our knowledge, it is the only direct comparative analysis to examine the experiences of Amerasians in Vietnam in relation to those of Amerasians who immigrated to the US. Furthermore, the use of SenseMaker, as a mixed-methods narrative capture tool, offered several advantages, such as open-ended storey prompts, which allowed participants to determine which experiences were most important to share. SenseMaker also allowed participants to interpret their own experiences and in doing so, reduced interpretation bias.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: doi: 10.25500/eData.bham.00000242.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Birmingham Ethical Review Board (ERN_15-1430). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This study was supported by Wellcome Trust under Grant WT110028/Z/15/Z.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all participants who shared their personal storeys in the course of this research. We are also indebted to the Vietnam chapter of Amerasians Without Borders who was instrumental in identifying and recruiting participants as well as to the Faculty of Anthropology at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities at the Vietnam National University in Ho Chi Minh City who implemented the research and conducted the interviews. The authors would specifically like to acknowledge Dr. Truong Thi Thu Hang for her contributions to the in-country implementation of the research project and her contextual insights shared at an analysis workshop in Kingston, Canada, in September 2017.

Footnotes

1. ^Bui Doi is a generic term used in Vietnamese for those living at the margins of society; it is not limited to Amerasian children of the Vietnam War. See McKelvey (1999) p. 5.

2. ^For details about Operation Reunite see http://www.adoptedvietnamese.org/avi-community/other-vn-adoptee-orphan-groups/operation-reunite/. Accessed August 9, 2017.

3. ^For the purposes of this paper, “Amerasian” refers specifically to Vietnamese Amerasians born to Vietnamese mothers and GI-fathers during the Vietnam War.

References

Aljazeera (2021).US Completes Afghanistan Withdrawal as Final Flight Leaves Kabul. Available online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/8/30/us-completes-afghanistan-withdrawal-as-final-flight-leaves-kabul (accessed June 3, 2022).

Amerasian Immigration Act (1982). An act to amend the Immigration and Nationality Act to provide preferential treatment in the admission of certain children of United States citizens. Pub.L. 97-359; 96 Stat. 1716. 97th Congress.

BBC (2021). Why is the Taliban's Kabul victory compared to the fall of Saigon? Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-58234884 (accessed June 3, 2022).

Bernak, F., and Chung, R. C.-Y. (1997). Vietnamese Amerasians: psychosocial adjustment and psychotherapy. J. Multic. Counsel. Develop. 25, 79–88. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1912.1997.tb00317.x

Brockell, G.. (2021). The fall of Saigon. As Taliban seizes Kabul, the Vietnam War's final days remembered. Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2021/08/15/saigon-fall-kabul-taliban/ (accessed June 3, 2022).

Brown, A. D.. (2006). A narrative approach to collective identities. J. Manage. Stud. 43, 731–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00609.x

Carpenter, R. C.. (2007). Born of War: Protecting Children of Sexual Violence Survivors in Conflict Zones. Bloomfield: Kumarian Press.

Cognitive Edge (2017). Sensemaker. Available online at: https://sensemaker.cognitive-edge.com (accessed June 30, 2022).

DeBonis, S.. (1994). Children of the Enemy: Oral Histories of Vietnamese Amerasians and their Mothers. Jefferson: McFarland and Co.

DeLong, S.. (2016a). Statistics in the triad, part I: geometric mean. Available online at: http://qedinsight.com/2016/03/28/geometric-mean/ (accessed June 30, 2022).

DeLong, S.. (2016b). ‘Statistics in the triad, part II: Log-Ratio transformation. Available online at: http://qedinsight.com/2016/03/28/log-ratio-transformation/ (accessed June 30, 2022).

Felsman, J. K.. (1989). Vietnamese Amerasians: Practical Implications of Current Research. Washington DC: Office of Refugee Resettlement, Family Support Administration, Dept. of Health and Human Services.

Gaines, J.. (1995b). 2 Decades after the U.S. carried out “Babylift” in South Vietnam, you should see them now. St. Louis Post Dispatch.

Girl Hub (2014). Using Sensemaker? to understand girls' lives. Available online https://narrate.co.uk/portfolio/girl-hub/ (accessed June 30, 2022).

Glaesmer, H.. (2012). Kinder des Zweiten Weltkrieges in Deutschland. Ein Rahmenmodell für psychosoziale Trauma Gewalt. 6, 318–328.

Guardian (2021). Afghanistan likened to fall of Saigon as officials confirm Taliban taka Kabul. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/13/afghanistan-likened-to-fall-of-saigon-as-us-and-uk-send-troops-to-aid-evacuation (accessed June 3, 2022).

Hayslip, L. L.. (2003). When Heaven and Earth Changed Places: A Vietnamese Woman's Journey from War to Peace. New York, NY: Plume

Ho, B., Bartels, S., and Lee, S. (2019). Life courses of Amerasians in Vietnam: a qualitative analysis of emotional wellbeing. VNU J. Soc. Sci. Human. 5, 563–80. doi: 10.33100/jossh5.5.Ho.etal

Kellas, J. K., and Trees, A. R. (2006). Finding meaning in difficult family experiences: Sense-making and interaction processes during joint family storytelling. J. Family Commun. 6, 49–76. doi: 10.1207/s15327698jfc0601_4

Kumin, J.. (2008). Orderly departure from Vietnam: Cold War anomaly or humanitarian intervention? Refugee Survey Quart. 27, 104–117. doi: 10.1093/rsq/hdn009

Lamb, D.. (2009). Children of the Vietnam War. Smithsonian Magazine, Available online at: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/people-places/Children-of-the-Dust.html?c=yandstory=fullstory (accessed June 30, 2022).

Lee, S.. (2017). Children Born of War in the Twentieth Century. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Lee, S., and Bartels, S. (2019). Self-interpreted narrative capture: A research project to examine life courses of Amerasians in Vietnam and the United States. Methodol. Innov. 12, 2059799119863280. doi: 10.1177/2059799119863280

Lee, S., Glaesmer, H., and Stelzl-Marx, B. (2021). Children Born of War – Past, Present and Future. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429199851

Lind, T.. (2016). Children of the Vietnam War spent decades finding American fathers. The Spokesman-Review Available online at: http://www.spokesman.com/stories/2016/jun/17/children-of-the-vietnam-war-spent-decades-finding-/#/0 (accessed June 30, 2022).

Long, P. D. P.. (1997). The Dream Shattered: Vietnamese Gangs in America. Richmond: Northeastern University Press.

McKelvey, R. S.. (1999). The Dust of Life. America's Children Abandoned in Vietnam. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

McKelvey, R. S., Mao, A. R., and Webb, J. A. (1992). A risk profile predicting psychological distress in Vietnamese Amerasian youth. J. Psychiat. Psychiat. 31, 911–915. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199209000-00020

McKelvey, R. S., and Webb, J. A. (1993). Long-term effects of maternal loss on Vietnamese Amerasians. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiat. 32, 1013–1018. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199309000-00020

McKelvey, R. S., and Webb, J. A. (1995). A pilot study of abuse among Vietnamese Amerasians. Child Abuse Neglect. 19, 545–553. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00014-Y

McKelvey, R. S., and Webb, J. A. (1996). Premigratory expectations and post-migratory mental health. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiat. 35, 240–245. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199602000-00018

Ranard, D. E., and Gilzow, D. F. (1989). The Amerasians. in America. The U.S. Agency for International Development.

Rosen, E.. (2015). The Vietnam War, as Seen by the Victors. How the North Vietnamese remember the conflict 40 years after the fall of Saigon. The Atlantic.

Sachs, D.. (2010). The Life We Were Given. Operation Babylift, International Adoption and the Children of War in Vietnam. Boston: Beacon Press.

Seto, D.. (2013). No Place for a War Baby. The Global Politics of Children Born of Wartime Sexual Violence. Farham: Ashgate.

Taylor, R.. (1988). Orphans of War. Work With Abandoned Children of Vietnam 1967-−1975. London: Collins.

The United States Agency for International Development (1975). Operation Babylift Report (Emergency Movement of Vietnamese and Cambodian Orphans for Intercountry Adoption). Washington, DC: The U.S. Agency for International Development.

Thomas, S.. (2021). Scars of War: The Politics of Paternity and the Responsibility of Amerasians in Vietnam. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1zjgbd4

Turner, J. R., and Barker, R. M. (2019). Complexity theory a: an overview with potential applications for the social sciences. Systems. 4, 4–23. doi: 10.3390/systems7010004

US General Accounting Office (1994). Vietnamese Amerasian Resettlement: Education, Employment, and Family Outcomes in the United States. Washington DC: US General Accounting Office.

Valverde, K.-L. C.. (1992). “From dust to gold: The Vietnamese Amerasian experience,” in ed Root, M. P. P, Racially mixed people in America. (London: Sage Publishers), 144–61.

Varzally, A.. (2017). Children of Reunion: Vietnamese Adoptions and the Politics of Family Migrations. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. doi: 10.5149/northcarolina/9781469630915.001.0001

Webster, L.. (2015). Using Statistics to Help Interpret Patterns: Are My Eyes Tricking Me? Available online at: http://qedinsight.com/2015/06/04/are-my-eyes-tricking-me/ (accessed June 30, 2022).

Webster, L., and Carroll, M. (2014). Webinar: the art and science of story patterns. Available online at: http://qedinsight.com/resources/library/november-2014-webinar/ (accessed November 2014).

Keywords: Amerasians, children born of war, Vietnam war, stigma, discrimination, mixed-methods, SenseMaker®

Citation: Lee S, McKelvey R and Bartels SA (2022) “I Grew Up Longing to Be What I Wasn't”: Mixed-Methods Analysis of Amerasians' Experiences in the United States and Vietnam. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:865717. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.865717

Received: 30 January 2022; Accepted: 22 June 2022;

Published: 28 July 2022.

Edited by:

Vinicius Rodrigues Vieira, Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado, BrazilReviewed by:

Bojan Vranic, University of Belgrade, SerbiaSabrina Thomas, Wabash College, United States

Copyright © 2022 Lee, McKelvey and Bartels. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sabine Lee, cy5sZWVAYmhhbS5hYy51aw==

Sabine Lee

Sabine Lee Robert McKelvey2

Robert McKelvey2 Susan A. Bartels

Susan A. Bartels