94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 27 April 2022

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.857597

This article is part of the Research TopicBeyond the Frontiers of Political Science: Is Good Governance Possible in Cataclysmic Times?View all 9 articles

This article poses, and attempts to answer, two correlated questions: (1) Is nationalism, the dominant ideology in our world of nation-states, compatible with the struggle to halt or minimize climate change and related environmental catastrophes? and (2) Which form(s) of government, whether or not informed by nationalist ideology, could better address the most serious threat to human life that currently appears on the horizon? This article puts forward the claim that while the former question has only recently begun to be explored in a few essays and articles devoted to analyzing the linkages between nationalism and climate change, the latter remains unexplored. Attempting to fill this gap, we investigate case studies of exemplary nation-states that periodically scored the highest in the Environmental Performance Index (EPI) and the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI): Scandinavian countries (Norway, Sweden, Denmark), Switzerland, and Germany. Their cities received environmental awards (i.e., the European Green Capital Award) and registered the highest levels in terms of citizen satisfaction. The goal is to identify factors and (pre)conditions that make forms of “green nationalism” possible.

Climate change is rapidly becoming the greatest threat to the stability of contemporary societies in the near, rather than distant, future. It is accompanied by a series of concomitant crises, such as biodiversity loss and mass extinction, interruption of food chains, pandemics, overpopulation, the omnipresence of micro-plastics, and air and water pollution, which seem to require a huge effort of cooperation between nation-states if they are to be tackled. As Ulrich Beck put it when conceptualizing his cosmopolitan imperative: cooperate or fail! (Beck, 2011). Easier said than done. No study has so far theorized, or even described, how this could happen—whether certain preconditions are needed so that said collaboration between the many actors that concur with the climate crisis can successfully be carried out, or how best to address such a complex problem from the various perspectives of local, state, and supranational governments.

We need to start by acknowledging two fundamental postulates: (1) our world is dominated by nationalism as the “dominant mode of political legitimacy and collective subjectivity in the modern era” (Malešević, 2019, p. 17); and (2) the nation-state is “the dominant political reality of our time” (Brubaker, 2015, p. 115). Although nationalism is a predominant force in our societies, no study has addressed climate change from the perspective of nationalism theories till 2020. Before 2020, the geo-historical notion of Anthropocene did not appear in any of the issues of the main journals dedicated to nationalism studies (Nations and Nationalism; Ethnicities; Nationalism and Ethnic Politics; Ethnopolitics; SEN—Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism; Nationalities Papers); the first mention appeared that year in Nationalities Papers (Conversi, 2020b). This lack of attention can be seen across the entire field of nationalism studies, which lags far behind most other (inter)disciplinary fields in the social and political sciences (Conversi, 2020b; Zalasiewicz et al., 2021). At the time of writing, the issue has not been substantially discussed or theorized.

Among the few exceptions, Thomas Eriksen has identified the main outlines of the Anthropocene in the way “the human footprint is visible everywhere owing to an exponential increase of human activities, premised on population growth and technological innovations fuelled by non-renewable energy sources and leading to short-term environmental degradation and long-term climate change”. (Eriksen, 2021a, p. 131).

Another exception is the world historian Prasenjit Duara who, more recently, wrote from a subaltern perspective on nationalism and climate change as part of the interlinked crises of global modernity (Duara, 2021).

The lack of bridges between nationalism theories and climate change studies is relevant for various reasons. First, while climate change affects all forms of life, it has particularly ominous implications for ethnic minorities, which are beginning to be deeply affected in many areas of the world (Doherty and Clayton, 2011), from Indigenous Peoples (Baird, 2008), to the urban poor and peasants (McKeon, 2015), with specific vulnerability spots situated in the Tropics (Loh and Harmon, 2005; Corlett, 2012) and increasingly elsewhere.

A question spontaneously arises: Can the response to the challenge be addressed through the lens of nationalism theories? One of the problems here is that global risks such as climate change (but also pandemics) are fought primarily as national threats within national borders, although they are clearly transnational in nature and consequences. One of the major threats to international treaties on climate change, such as the Paris Agreement adopted in 2015, is undoubtedly what we could call the principle of “national priority”, which means that nation-states principally worry about matters of internal security, domestic homogeneity, and national growth, and less about global issues and other nations' troubles (Posocco and Watson, 2022). This is one of the reasons why climate change is often fought as a national struggle and only secondarily as a global one.

In some cases, national priority suggests not joining the fight on climate change. This is the case when espousing environmental ideology poses a threat to a nation's economic prospects (e.g., to stop using fossil fuels is a direct economic threat to traditional petroleum exporting countries (OPEC) such as Iran, Iraq, and Libya). Here, we are faced with what has been defined as resource nationalism (RN): ‘a form of nationalist rhetoric that uplifts and sacralizes soil-rooted national resources as a common good even though only a tiny minority of the population actually benefits from their extraction and exploitation' (Conversi, 2020b, p. 630). Beside petroleum exporting countries, Brazil's rapid deforestation of Amazonia is another example of RN. This form of nationalism is particularly performative in downplaying the global effects of the exploitation of national resources, claiming that it is done for a greater good (the nation's good) and deemed necessary to keep the economy going. While more studies are needed that investigate the ways in which nations respond to global threats in nationalist rather than international ways, these responses tend to be much more national than international in orientation.1 The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is a good example of how each nation-state responds to global threats differently with the goal of preserving their own health system and wider society above others. It shows how strong nation-states and nationalist discourses are and how pervasive nationalist ideology is. Here, the question is whether nationalism and the nation-state can change, and how climate change can be addressed more effectively so that it is less prone to national priority.

This article is divided into three parts: The first part introduces the general context by highlighting the challenge, whose contours might still be unclear among nationalism scholars. The second part deals with the two key initial questions: whether nationalism is a major obstacle to the adoption of global, effective, and broadly coordinated mitigation strategies; and whether current institutional settings can deliver on these. The third part identifies what we'll call “exemplary” nation-states, those that have achieved the highest levels of sustainability. The study of these nation-states is aimed to identify the factors and preconditions that can make “green” forms of nationalism possible.

Anthropocene is a neologism created to define the effects of human activities on the planet; in particular it indicates how humankind is shaping the Earth's geology in an irreversible way (Crutzen and Stoermer, 2000; Steffen and Crutzen, 2007). The Anthropocene is characterized by the earth-shattering impact of industrial activity, large-scale industrial agriculture, and mass consumption. It is a broad concept in which climate change plays a pivotal role as its primary vector.2 In the 1960s, mass consumerism began to pervade all aspects of life in the West, and then in the East, leading to a sudden acceleration in the noxious gases released into the atmosphere (Syvitski et al., 2020). In the second half of the 20th century and early 21st century, economic growth led to “extraordinary human energy consumption” (Syvitski et al., 2020).

Recent path-breaking research has dated the beginning of the Anthropocene to the years of the economic “boom”, the 1950s and 1960s (McNeill and Engelke, 2016). This path to destruction is based on the imaginary cornucopia of infinite capital expansion, as it spread from the USA to Europe, China, India, and beyond. Its economic core was based on practices of market expansion, which led to the release of more and more megatons of industrial emissions as well as waste onto the Earth's surface.

The unprecedented emergency created by the expansion of the American/Western model of mass consumption is so radical and widespread, and its effects so disastrous on both the short-term and the long-term, that it needs to be tackled with urgency. This has proved impossible to date, because efforts to break away from the current development path are often blocked by a gridlock of nation-state boundaries, whose governments are aligned with interest groups that do not hesitate to use nationalism to advance their interests, for corporate or personal profit.

Finally, the “economic boom” of the post-1960 acceleration can be put into historical perspective by introducing a third concept, the notion of “acceleration of acceleration” (Eriksen, 2009, 2016, 2021a) based on an “extraordinary human consumption of energy” in the second half of the twentieth century and the beginning of the acceleration of acceleration (Syvitski et al., 2020). Although the recently proposed beginning dates back to 1950, the increase in GHGs peaked after 1970 and began to accelerate in the 1980s and even more so in the 1990s, after the fall of the Iron Curtain. More energy has been consumed in the past 70 years than in the entire Holocene, while global average atmospheric temperatures have risen by a staggering 0.9°C over the past 70 years. Less than 1°C seems a trifling amount, but if our own average temperature were to rise by 1°C without us being able to lower it we would all live in perpetual fever! In this case the planet already has a fever, and so far we haven't been able to lower it.

Moreover, the amount of ~ 22 zettajoule (ZJ; one ZJ is equal to one sextillion joules) accumulated over the past 40 years exceeds that of the previous 11,700 Holocene years (~14.6 ZJ), mainly as a result of the consumption of fossil fuels. Over 90% of the excess energy ends up in, and is temporarily absorbed by, the oceans, whose temperatures are rising rapidly. This gigantic amount of heat corresponds to about five Hiroshima atomic bombs per second. In his book Overheating, the Norwegian anthropologist Thomas Hylland Eriksen describes this phenomenon of increasing acceleration well (Eriksen, 2009, 2016, 2021b; Eriksen and Schober, 2017).

The unprecedented emergency created by the expansion of the US model of mass consumption is therefore so critical that it is now necessary to involve all political forces in the establishment of an international simultaneity and synergy to address the problem in a reasonably quick time. However, this has so far been impossible.

Nationalism is arguably the dominant ideology in contemporary society (Conversi, 2010, 2012, 2014; Malešević, 2019), and it seems to be here to stay (Tamir, 2020). Given the ubiquity and endurance of nationalism, we need to explore whether it is conceivable that there are forms of it that can successfully tackle climate change (Conversi and Friis Hau, 2021). The question is legitimate. For Held (2010) the nation-state is inadequate, in its present forms, to handle global commons such as the spread of disease, pandemics, epidemics, poverty, conflicts, toxic disposal, and certainly climate change. Even a superficial look at the current COVID-19 pandemic shows the confusion that reigned: disagreement, little cooperation, and even attempts at discrediting other nation-states for the methods they used to halt the virus. These are evidences largely acknowledged by the World Health Organization (WHO), which warned about signs of stigma and politicization of the pandemic (WHO, 2020). Like the pandemic, climate change also remains a highly politicized phenomenon (Jamieson, 2014). As with the pandemic, marked by rich nation-states racing to buy their way out of the crisis before poor ones by gaining for themselves the first doses of vaccines,3 climate change also threatens the poor first. It isn't difficult to imagine what will happen when catastrophic events hit with more intensity than they already do now—when vast stretches of the earth become uninhabitable, plagued by extreme weather, drought, rising seas, and crop failure (Chomsky and Pollin, 2020). The ‘uninhabitable Earth' is a possibility, in which nations and nation-states will de facto cease to exist (Wallace-Wells, 2019).

The problem is that climate change and other crises cannot be tackled without combining a diversified set of policies at every level of government and governance. Yet, all these spheres are interconnected and nationalism can (and does) pose a major threat and risk to the sine qua non of international coordination and equal access to resources. Is there any way out from the impasse?

Some have pointed to cosmopolitanism (Calhoun, 2003; Beck, 2004, 2016; Beck and Sznaider, 2006), or “survival cosmopolitanism” (Conversi, 2012, 2020b). These authors argue that cosmopolitanism in a political sense, thus including kosmos—meaning “everybody”—and opposing the limitations of éthnos—meaning the nation—would bring a more cooperative, inclusive, coordinated, and solidaristic global order, which is needed to cope with global threats. The augmented capacity in terms of cooperation that a cosmopolitan world of cooperative societies might achieve is a potential answer to the problems posed by nationalism. And yet, evoking a cosmopolitan utopia doesn't solve divisions based on ethnic and national logics; it doesn't make national ideology disappear, nor does it increase nation-states' solidarity. When it comes to climate change, the problem is that it is often seen and discussed as a matter of global concern, but national ideology didn't develop to provide answers to global issues. Indeed, nationalism was born primarily “as a force for mobilizing people and legitimizing their emancipation, as an identity giver, and as an ideology that enhances micro-solidarity, not to solve global issues” (Posocco and Watson, 2022, p. 6). For this reason, nation-states are more concerned about national priorities, and often in the short term, given that most national elections happen every 3–5 years. That said, the available literature on cosmopolitanism doesn't inform us about how this ideology would materially supplant nationalism, national electoral systems, vast and historically grounded national narratives, and myths of descent as well as the many national institutions such as national academies, national theaters and museums, and national sports (just to mention a few). Perhaps alternatives to cosmopolitanism are needed.

One of those alternatives comes from the study of Green Nationalism (GN) (Conversi, 2020b, 2021b, 2022; Conversi and Friis Hau, 2021), a form of nationalism that supports national sustainability. Rather than exploiting nature for nationalistic purposes, GN is characterized by policies that safeguard the environment and ecosystems. One of the problems of GN is that so far it has been identified in sub-state nationalist parties acting in the name of some minority or stateless nations, such as Scotland (Brown, 2017) and Catalonia (Conversi and Friis Hau, 2021)—but not in all of them—and in some case enacting very weak environmental legislation (Conversi and Ezeizabarrena, 2019). The former have championed the environment not only for the environment's sake but also to pursue their own interests. Stateless nations embrace GN and use it as a weapon against those in power, especially by incarnating the habitus of environmental champions and portraying their political antagonist as inefficient and/or careless toward it. One of the features of GN is that it loses its push when its advocates reach their goals, i.e., when they gain political representation (Conversi, 2020b). However, forms of Green Nationalism do exist that, as the case study of Germany shows (Posocco and Watson, 2022), can overcome the limits of resource nationalism as well as forms of ecologism and environmentalism that have proved unsuccessful. Countries such as Switzerland (Salvi and Syz, 2011), Denmark (Ingebritsen, 2012), Sweden (Anselm et al., 2018; Kaijser and Heidenblad, 2018) and Finland (Ridanpää, 2021) have taken paths that seem to be similar to Germany. The comparative study of these countries is functional to identifying elements that characterize Green Nationalism.

The underlying reason for such an endeavor is that, if nationalism is here to stay (Tamir, 2020), we'd better find versions of it that allow for positive developments against climate change. After all, many studies posit that nationalism is not solely about violence (Maleševic, 2013; Harari, 2019). It's appalling reputation might well come from the events that it is most known for: the two world wars that characterized the 20th century, with a huge number dying and unprecedented brutalities in the Holocaust. (Fascism and Nazism, perhaps the two most extreme forms of nationalism, were unthinkable without the previous cataclysm of WW1, which can be described as the nationalist war par excellence).

More recently, nationalist developments in other contexts and regions such as in ex-Yugoslavia and after the collapse of the Soviet Union have meant that when the word “nationalism” is used, it does not evoke positive emotions. Indeed, adjectives such as “extreme” or “violent” are often used to identify nationalism and highlight its negative aspects. Evidence from recent research supports the thesis that bureaucratic pressure and mass mobilization are needed to persuade people to die or kill for their country and fellow countrymen and women (Maleševic, 2013). Nationalism also materializes in common national languages and markets (Gellner, 1983), or in shared institutions, such as national education, national health care, and even democracy (Harari, 2019). National projects that embrace democracy function as branches of a tree that spread far and wide through the national territory, much further than in polities such as tribes or city-states. They provide a greater number of people with, for example, political representation, the right to vote, and other fundamental rights such as the “right to a cure”, the right to live in a safe environment, etc. (OHCHR, 2021). Given that (1) nationalism is a force that supports the nation, and (2) climate change is a threat for all nations, it would be remarkable not to find exemplary nation-states that function as forces strongly committed to stopping or mitigating the effects of this threat.

By “exemplary nation-states” (ENS), we mean those communities that have made forms of sustainable living possible both at a small, community scale (Levene and Conversi, 2014; Conversi, 2021a) as well as at the regional or national level (Posocco and Watson, 2022). The notion of ENS is thus a variety of the previously developed notion of “exemplary ethical communities” (EEC) (Conversi, 2021a). These forms include eco-villages, transition towns, self-sustained communities, renewed spiritual traditions, and individual lifestyle changes that are conceived to exit the market economy, including forms of “food sovereignty” (Conversi, 2016) but also official institutions such as governments committed to and successful in decreasing GHG emissions, incentivising the use of green and renewable energy, promoting advanced forms of waste recycling, and supporting the protection of natural habitats—animal as well as human life. It is true that probably no single remedy can be found to tackle climate change and that a great variety of factors will most likely be needed, within each nation-state and certainly at the international level. Yet, the study of those exemplary communities that have embarked on the journey of environmental protection to fight climate change is needed to highlight the necessary factors in order to mitigate the latter's effects. These communities represent perhaps the only viable options, and certainly sources of inspiration, for 21st century nation-states driven by national ideology.

The choice of focusing on Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Switzerland comes from the evidence that: (1) these countries have often been ranked at the highest levels in two of the most important environmental indexes—the Environmental Performance Index (EPI),4 and the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI)5—and (2) these countries did not renounce nationalism, which not only remains their political ideology but bonds with environmentalism to create distinctive forms of GN, in order to achieve their goals. That said, the goal here is to identify those factors that make the bonding between nationalism and environmentalism possible. This article identifies four of these: (1) a tradition of environmentalist ideals; (2) grassroot environmental activism; (3) environmental policy sustained in the long run; and (4) sustainable practices at various levels of society.

The 1960s occupy a special place in Scandinavian historiography (Kaijser and Heidenblad, 2018; Heidenblad, 2021). What is commonly known as the “environmental turn”, the intense environmental debates that started in 1968 and reached a peak in the 1970s worldwide, occurred earlier in Scandinavia, in the mid-1960s. As previously mentioned, environmental problems began to be felt widely in the 1960s. In 1970, these culminated in the establishment of Earth Day, which has been held annually ever since, on April 22; an Earth Day Network was established, later coordinated by EarthDay.org with the participation of one billion people around the world (Freeman, 2002; Rome, 2010).

The Scandinavian “environmental turn” was due to the work of (numerous) environmental organizations such as Fältbiologerna (Nature and Youth Sweden),6 distinguished by being committed not only to instilling love for nature but to spreading environmental ideals such as being influential and radical when it comes to protection of the environment and engaging in environmental debates and actions where necessary. Fältbiologerna's slogan “keep your boots muddy” didn't mean only to materially “live” nature. The metaphor of “dirt” also meant to fight against environmental problems such as dirty water, air pollution, waste management, and all the dirt linked to the growing number of human activities that exploit the planet's natural resources (Kaijser and Heidenblad, 2018). The slogan materialized in organized demonstrations against projects that risked endangering the environment such as the nationwide demonstration in 1969, held at Sergels Square (Stockholm), against the expansion of hydroelectric power in northern Sweden.

Heidenblad (2021) points to numerous similar demonstrations linked to the relationship with nature that is deeply rooted in Scandinavian culture. The specific Norwegian word friluftsliv translated as ‘free life air', condenses this. Friluftsliv means “a philosophical lifestyle based on experiences of the freedom in nature and the spiritual connectedness with the landscape” (Gelter, 2000, p. 78). As famously highlighted by Eric Fromm, the difference here from the mode of possession in consumer society that commodifies nature is significant (Fromm, 1976). Friluftsliv posits that being in/with nature is not something that can be achieved by means of action, such as conquering a mountain or camping, but identifying with it. The central idea is that human life and natural life are the same, and endangering one results in endangering the other. The concept of friluftsliv is common in Scandinavian countries, the fruit of a long tradition of education that was initially conducted through official institutions such as Fältbiologerna or Friluftsfrämjandet (Swedish Outdoor Organization), the Danish Outdoor Council (Friluftsråde), or the Norwegian Trekking Association (Den norske turistforening). As Gelter (2000) posits, the benefits in terms of environmental awareness include the fact that Scandinavian countries developed a strong environmental identity that bonded with the national one. Identifying with the nation, thus having an image of communion with fellow countrymen and women even if one will never know most of them (Anderson, 2006), is extended to the national environment (mountains, rivers, lakes, forests, etc.). The same fraternity that makes it possible “for so many millions of people not so much to kill, as willingly to die for such limited imaginings” (Anderson, 2006, p. 6–7), is extended to the national environment. This is particularly true for Norway, which gained national autonomy in 1905 and made friluftsliv a matter of national pride, an element that characterizes Norwegian identity (Gelter, 2000).

The bonding between nationalism and environmentalism is thus a cultural trope in Scandinavia, and lies at the roots of people's mobilization against forces that threaten the national environment. That said, it doesn't mean that the lifestyle of many Scandinavian, German, and Swiss people isn't drenched in high-energy activities that contrast with the very basis of a sustainable society. Indeed, in order to enjoy nature, Norwegian elites demand luxury cabins for private use, buy more cars to drive there, use expensive floor heating, etc. As with many other countries, Scandinavians, too, are subject to consumer capitalism. For their outdoor activities they own not just one pair of skis (as they did perhaps in the 1970s), but six or eight pairs, for different purposes.

Germany's environmental history has much in common with Scandinavian countries. As Uekötter (2014) puts it, the network of environmental associations in the Reich in the 19th century were vast and complex. Although the birth of these associations occurred mainly within the framework of the German states, which have historically been keen to maintain internal autonomy, love for the environment followed nationalist dynamics. Indeed, when looking at the names of these associations, one cannot but acknowledge the way environmentalism expressed itself through nationalism, whether in its local, regional, or national specificities—Homeland Protection (Heimatschutz), the Bavarian League for Nature Protection (Bund Naturschutz in Bayern), and the League of Animal Protection Associations of the German Reich (Verband der Thierschutz-Verine des Deutschen Reiches). While similar trends are visible in other countries, the specifics in Germany at the crossroads between the 19th and 20th centuries indicates that the alliance between nature protection organizations and the German state was very strong (Uekötter, 2014, p. 31). In the early 20th century, “The newly created civic organizations had barely begun working when the state administrations were already eagerly searching for ways to pull the new issue into the orbit of state policies” (Uekötter, 2014, p. 32). Whatever logic pushed the state to “domesticate” ecological/environmentalist movements, the tradition of environmental policy in Germany is one of the oldest in Europe, and beyond.

While Norwegians developed the concept of friluftsliv in the 1970s, Germans had the Life Reform (Lebensreform) movement, which took various forms such as hiking groups, naturopathy, nudists, vegetarianism, and others. One of the major elements of Life Reform was the refusal of society born out of the industrial revolution, and the development of a counter-revolution that aimed to “return to nature”. In Germany, this also took mythical forms expressed through literature, art, music, and opera (Schumann, Brahms, Mendelssohn, Wagner, and Mahler are all important representatives of German romanticism, which highlighted and took inspiration from nature). Closeness to nature became one of the elements characterizing the German bourgeoisie. It was also a modus vivendi that other sectors of society, including the lower classes, were pushed to imitate (according to their available resources). Social institutions such as national schools, museums, and outdoor organizations played a role in making this happen, instilling love for the natural wonders of their nation. In Germany, love of nature is thus one of the founding elements of national identity and formed the very pillars of German environmentalism in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

This love of nature took both peaceful and violent forms. In fact, there is a substantial difference with the Völkisch (ethno-nationalist) elements that in the past appropriated this call for land: “reclaiming” the land, seemingly so much at odds with a supposed ecological defense of the territory, was a recurrent practice among expanding European nationalisms. This was clearly shown in the Prussian/German conquest of the “wilderness” of the marshes, as the German state was reframed as the Lord and Master of Nature (Blackbourn, 2006). The 19th century was also a colonizing age of dam-building, social engineering, and a technocratic cult for mechanization. In other words, the nature-loving trend within German nationalism before WW2 was accompanied by a frenzy for the electrification, commodification, and nationalization of the national space (Conversi, 2012). The Janus-faced essence of nationalism allows it to be used for apparently contradictory, even incompatible, purposes: while claiming the beauty of national landscapes and the virtues of peasant life, nationalism was also a tool of bourgeois expansion (HadŽidedi, 2022). Nationalism aimed at the transformation of “peasants into Frenchmen” (Weber, 1976), it institutionalized a perfect congruence between state, people, culture, and territory (Mandelbaum, 2020)—a kind of mystical union converging around the veneration of the patriotic totem.

This doesn't alter the fact that it is difficult to understand environmental activism in West Germany in the second half of the 20th century without considering environmentalism as an ideology shared by Germans prior to that time, which contributed to their will to mobilize for the protection of nature.7 There isn't space here to list the numerous demonstrations in support of the environment that made Germany what Uekötter (2014) calls one of the “greenest” nations. It will suffice to remember some of the events of the 1970s and 1980s: two decades during which the German environmental movement steadily grew. These included the massive protests against the construction of the nuclear plant at Wyhl, on the river Rhine, in 1973 and 1983. Resistance took the form of lawsuits, squatting on the building site, the establishment of a radio broadcasting channel, and many demonstrations (Kunze and Philipp, 2013). In 1983, 30,000 people demonstrated against the nuclear power plant and kept challenging its construction even when official permission had already been granted (Patterson, 1986). In 1975, the Bund für Umwelt und Naturschutz Deutschland (German Federation for the Environment and Nature Conservation) was born and backed most of these and many other environmental grassroots' actions. Balistier (1996) collected data supporting evidence of 9,200 protest actions in 1983 alone, when the environmental movement peaked in Germany. It was irrelevant that, as Wagner (1994) and Dryzek et al. (2002) put it, the environmental movement represented in politics by Die Grünen (the Green Party, which took shape in the early 1980s) was excluded by Helmut Kohl's government. The massive number of protests and media coverage projected environmentalism outside the local bubbles in which it was born to become a nationally debated phenomenon. Eventually, Die Grünen joined the federal government for the first time in 1998, gaining 47 seats.

These events should not be considered in isolation but as parts of a greater narrative of environmentalism that bore many fruits in Germany. These include the first ‘Zone 30' (30 km/h zone, Tempo-30-Zone in German) in Buxtehude, a small town near Hamburg, in 1983 (Colville-Andersen, 2018, p. 58). It should be noted that 1983 was a year of massive green protests in Germany. Even if the Green Party was in government they already exercised enormous pressure at local and regional levels. In time, the example set by Buxtehude was followed by many bigger cities, such as Munich, which today can count 2,300 km of urban roads in Zone 30, while the rest have a limit of 50 km/h. Freiburg and Hamburg have been among the first to extend the 30 km/h limit to large urban areas. Germany was also one of the first countries, if not the first, to create the “Blue Angel”, a label awarded to environmentally friendly products in Germany. Much of these achievements have strengthened the pride of Germans in being German: a nation that is moving toward sustainability, although much more needs to be done to fully achieve it (Posocco and Watson, 2022).

Switzerland's trajectory in terms of environmentalism is similar to Germany's and to the Scandinavian countries discussed here. Fast industrialization in the 19th century also brought environmental problems in Switzerland that sparked nostalgic ideas of the Swiss countryside characterized by “special patriotic overtones” (McNeill, 2000: 329). For example, when railroads were built everywhere in Europe (and beyond) in the 19th century as the distinctive feature of modernisation, the Swiss expressed their dissent, especially when railroads came closer to the Matterhorn, the mountain that is also a symbol of Switzerland and Swiss identity (Walter, 1989).

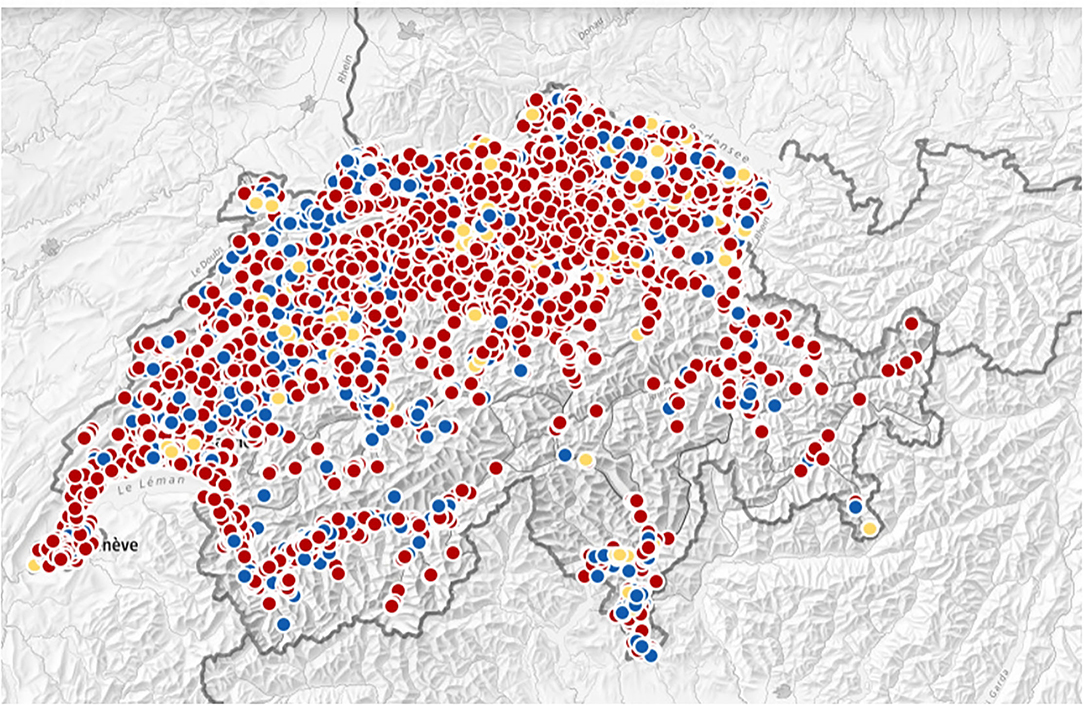

Influenced by Germany, Switzerland also had its Lebensreform, which provided ideological and practical tools to approach the negative consequences of industrialization—in particular, by proposing a return to nature, rejecting alcoholic beverages and tobacco, and preaching a more natural way of life. The physical vicinity of Germany and the fact that part of the Swiss population speaks a dialect of German was probably the basis of the proliferation of Lebensreform in Switzerland. The influence was reciprocal: German advocates of this new lifestyle influenced the Swiss and vice versa. For example, the Swiss painter Gusto Graeser was one of the founders of the community of Monte Verità (Ascona, Switzerland), which attracted many German artists and writers whose work spread the idea that nature is not external to human beings but integral to them (Herman Hesse and Gerhart Hauptmann were among these artists and writers). According to this view, what is true for Germany is also true for Switzerland. As Williams (2007) put it, it would be wrong not to see in these movements the roots of a larger interest in the protection of nature that flourished in the 1970s and 1980s. They emphasized and promoted the idea of the goodness of nature and the harm caused to it by human activities. These ideas became important parts of these communities' collective memory (Halbwachs, 1950) and laid the foundation for environmental activism and good practice. Perhaps it is no coincidence that Marco Salvi and Juerg Syz (Salvi and Syz, 2011) found a strong correlation between green buildings and linguistic affiliation and territoriality in Switzerland. See Figure 1 below. Green building density for German-speaking municipalities is 76.2% higher than for comparable French, Italian, or Romansh speaking municipalities. This data, supported by strong quantitative evidence, shows that culture might exert a major influence on environmental choices. The fact that the number of green buildings increases in alpine resorts, thus in places that were the stronghold of the Lebensreform movement and symbols of a deep connection between nature and Swiss national identity, is further important evidence strengthening this hypothesis.8

Figure 1. Image n. Spatial distribution of Green Buildings in Switzerland. This is a more updated map than Salvi”s and Syz”s study (2011), providing the number and position of green buildings in Switzerland in 2021. Green buildings remain clustered, mostly located in the northern and northeastern part of the country. The Ticino canton (close to the Italian border) exhibits lower green housing activity. Source: Swiss Office of Energy at https://map.geo.admin.ch/?lang=en&topic=energie&bgLayer=ch.swisstopo.pixelkarte-grau&catalogNodes=2419,2420,2427,2480,2429,2431,2434,2436,2767,2441,3206&layers=ch.bfe.minergiegebaeude (accessed January 2, 2022).

“When an idea becomes successful, it easily becomes even more successful: it gets entrenched in social and political systems, which assists in its further spread. It then prevails even beyond the times and places where it is advantageous to its followers” (McNeill, 2000, p. 326). McNeill derives this concept from historians of technology, who refer to analogous situations as ‘technological lock-in': the adoption of certain practices in technology (such as the narrow-gauge railway track adopted in the 19th century) that become standardized. The same applies to ideas. McNeill described as “ideological lock-in” the process characterized by ideas that become orthodoxies: dominant ideas that permeate various levels of society, including social and political institutions. Ideological lock-in can be a positive or a negative development. It is negative when ideas are so entrenched that they are hard to eradicate even when better options are available. It is positive when better ideas, such as that nation-states should take responsibility for the activities that harm living and non-living beings (within or outside their borders), take root and become orthodoxies. Environmentalism is a package of such ideas.

In the nation-states under investigation here, environmental ideas wormed their way through the political institutions and bonded with nationalism, suggesting to the nation's representatives that it is in the interest of the nation (and thus also in their interest) to be concerned about their natural resources, to protect them, to reduce human impact on the national environment, etc. By the 1980s, large sectors of the German, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, and Swiss populations, as well as their political forces, and even polluters, started to espouse these ideas. One of the case studies providing evidence of this comes from Vauban, a district of the city of Freiburg (Germany). It is possibly the most studied model of environmental sustainability and applied to many countries and regions (Buehler and Pucher, 2011; Fraker, 2013; Daseking, 2015). The case of Vauban, which was at the core of recent investigations (Posocco and Watson, 2022), shows what exceptionally positive changes might occur when national institutions fully embrace environmentalism. Vauban has historically been a contested territory between Germany and France. Under the Nazis, it became a military base, and occupied by the French after WW2 (until 1992). Vauban is the expression and symbol of nationalism, a place where France and Germany flexed their military muscles. The former took the territory from the latter, and vice versa, twice. Under the Nazis, Vauban followed Hitler's Recht des Stärkeren (“the right of the stronger”), as Brockers (2016) puts it, that aimed to justify Germany's attempt at supremacy.

After 1992, when the French military left, “Ownership of the district reverted to the German federal government and the City of Freiburg purchased it for some EUR 20 million” (Coates, 2013, p. 2). A few years later, a group of students, architects, and other ecologically minded citizens calling themselves “Forum Vauban” started to meet informally in a bid to save the district from the state of decrepitude in which muscular nationalism had left it. They reinvented Vauban as an ecological island “energy efficient, solar powered and largely car-free urban community. Soon thereafter they began to convert their dreams into reality” (Coates, 2013, p. 2). See Figure 2 as an example of Vauban's car-free street. Their ideas didn't come from nowhere. Indeed, around this area a tradition of environmentalism and environmental activism existed dating back to the late 1960s and especially the 1980s when there were major protests against the nuclear plant at Whyl (see previous section). But the real change was when Freiburg City Council embraced these people's ideas. This was the exact moment in history when nationalism, incarnated in state institutions, took off its clothes as a “violent” ideology, and espoused environmentalism. At this point, Vauban was still a district on the margins of German society, rather poor, its buildings occupied by squatters imbued with countercultural ideals and environmental dreams. The city provided these people with a rental contract and launched an urban planning competition that aimed to meet the demands of its citizens. As Posocco and Watson (2022, p. 15) note: “The competition was won by Kohlhoff/Billinger/Luz, a joint working group of architects, engineers and open space planners that also espoused environmentalism”.

Figure 2. Street view of Vauban, Freiburg. Picture credits: https://emmettrussell.co.uk/news/study-trip-to-vauban-freiburg/ (accessed January 5, 2021).

During the following 30 years, from 1992 to the present, there was a crescendo in environmental projects that spread to neighboring districts, the city of Freiburg, the region of Baden-Württemberg, and beyond. For this to happen, nationalism didn't have to disappear; indeed, it functioned as an important catalyst for environmentalism. Abandoning its violent and extremist forms, which have proved harmful to the German nation (and beyond), nationalism found expression in a more peaceful way as an ideology to protect the national environment. Growing scientific evidence that uncontrolled human activities are at the basis of the climate crisis, possibly the biggest threat that our societies now face, has strengthened the bond between nationalism and environmentalism in Germany. It is not surprising given that one of the elements of nationalism as an ideology is “priority to the nation” (Posocco and Watson, 2022). Nation-states are principally concerned about national matters and less about global issues. And yet, when nation-states where environmentalism is locked in realize that climate change isn't only a threat to some distant island that might disappear due to rising sea levels, but also to them, they act and take (national) pride in doing so.

In Germany, pride in increased national sustainability has taken local, regional, and national forms. National flags are waved and a national language is used in speeches by politicians and scientists that praise national efforts toward sustainability. In Vauban, a regional paper has commented: “The reputation of the “organic and eco-district” is justified […] It is a reputation that we “Vaubanler” [Citizens of Vauban] can be proud of: we lead by example” (Badische, 2014). At the national level, Dirk Messner, President of the Federal Environment Agency, stated “We can be rightly proud of what the new federal states have achieved in terms of environmental protection after 1990. In many rivers, which were ecologically dead at that time, life has returned. The air, which was biting in some regions 30 years ago, is now almost everywhere below the applicable limit values” (Bundesregierung, 2021). “We are proud to be one of the first countries in the world to have adopted a national resource efficiency programme” wrote Reinhard Kaiser, former employee of the Federal Ministry for the Environment (Kaiser, 2018). These are just some examples. There are many others, at all levels of society, where taking care of nature is promoted as something “German” that Germans can be proud of. The many awards such as the title of “European Green Capital” or the “United Nations” Environmental Award” and the increasing number of indexes that rank countries according to environmental criteria all help to encourage nation-states” pride in sustainability. Frankfurt, for example, was a finalist in the “European Greenest City” award supported by the EU. Media (and social media) coverage turn these awards into positive advertisement for “eco” nation-states such as Germany. Environmentalism becomes something commonly understood as good and worth pursuing, which in turn meteorically increases the popularity of green practice. This also has implications at the economic level—for example, many studies have started to investigate the positive effects of ecotourism (Fletcher, 2019; Fennell, 2020), others have highlighted corporate environmentalism as an opportunity for firms to improve brand image, reduce costs, make shareholders happier, and even increase productivity (Chrun and Dolšak, 2016). In Germany, the core of these developments lies in a synergy between political, economic, and social forces that either espouse or abide by environmental regulations, and believe that by acting in support of the environment they also act in the nation's interests.

The same is true for Norway, an actively inclusive state (Dryzek et al., 2002). As such it doesn”t only accept the demands of environmental activists and turn them into state policy, but anticipates them, securing a “desired pattern of interest articulation” (Dryzek et al., 2002, p. 660). It is also “an organizational society” (Selle et al., 2019, p. 5), which means that the range of organizations that form the third sector (including environmental ones) receive substantial financial support from the state. Financial resources follow governmental priorities and these are binding on those that receive them. Thus Dryzek et al. (2002) are right when they state that environmental groups in Norway are the very arms of the Norwegian state. Governments fund them to help draft environmental policy (Smillie and Filewod, 1993). Moreover, these organizations are also called to monitor the enforcement of these policies, identify environmental problems for legislative review, collect and assess information, and recommend courses of action and follow up. It is not surprising that Norway is called “the country of a thousand committees” (Klausen and Opedal, 2019). Environmental committees, a small but solid Norwegian tradition adding to Norway's welfare state, ensure citizens' participation in the political life of their country. In the past, they helped draft and enforce a number of notoriously “problematic” policies, including “eco taxes” in 1991 (Dryzek et al., 2002). In fact, when states are resolute in making polluters pay for harming nature, their polluting activities become financially unsustainable. The only countermeasure they can take is to convert to greener activities, adopt better technologies, or shut down. The state (through its governmental arms) seems to be the only power, when it realizes what a serious threat climate change constitutes, that has the tools (judicial and regulatory on top of symbolic power) to force polluters to stop polluting. The problem is that, although taxation is one of the most effective measures to fight climate change (Cullenward and Victor, 2020), for many reasons governments are often hesitant to use eco taxes. What's interesting about Norway is that such taxes are notoriously very high, which is also the reason why the Norwegian fiscal regime has by far the strongest CO2 abatement effect among all Scandinavian countries (Østli et al., 2021). While it is uncertain whether Norway will triple its national tax on CO2 emissions by 2030 (Reuters, 2021), it is worth mentioning here that certain propositions aren't even thinkable in other countries. From this perspective, Norway is far ahead.

Eco taxes aside, green parties play an important role in pushing environmental policy. This is particularly true in Germany, where the making of a green state came about through the growing power of the Green Party (Uekötter, 2014). The same is true for Norway, although unlike Germany, Norway's green party has until very recently received little or no attention at all by the Norwegian electorate.9 Environmental ideas and sustainability are an orthodoxy in Norway, they have locked in and spread, so much so that most parties have “green” policies in their programmes. This is clear when looking at the Norwegian Green Party (Miljøpartiet Dei Grøne) that gained 3.8% in the 2021 election, which was saluted as a victory. The same is true for the 6.8% gained in the municipal elections in 2019. The Norwegian case study is fundamental to understand that when environmental ideology is a national tradition, a cultural reality shared at many levels in society, environmental policy is the natural consequence of that society. The protection of the national environment isn't a problem that weighs on the nation but a national necessity, and as such is generally accepted (sometimes with some difficulty) even when it represents a burden on the taxpayers' money.

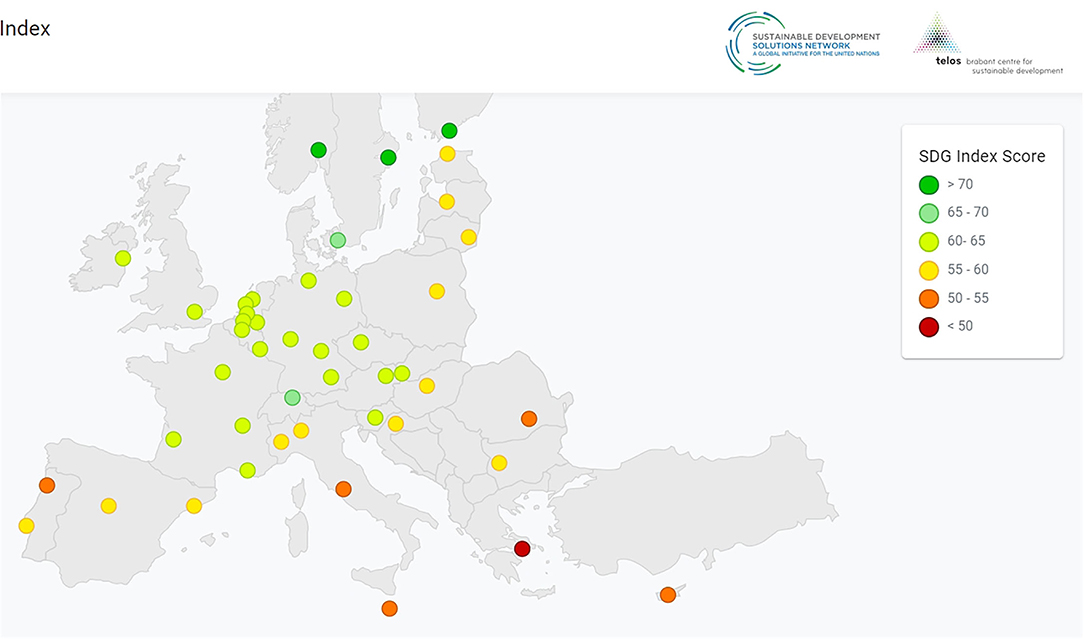

Although much more needs to be done in both Germany and Norway to build a fully sustainable society (the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) left the first three positions empty in its ranking, stating that even those, like Norway and Germany, that are doing better than others, should not ease up), most nation-states lie far behind. This is particularly striking when looking at the examples of Vauban (Freiburg), Munich, or Oslo. All three have developed a car-free city center and aim to achieve a 95% reduction in GHG emissions by 2030, a target that most cities hope to achieve by 2050. Zürich, in Switzerland, doesn't lag behind. In 2016, the Swiss city occupied first place in the Arcadis Sustainable Cities Index, which ranks 100 major cities on 32 indicators across three aspects of sustainability: people, planet, and profit. The 2020 CCPI ranking put it 15th, marking the fact that it remains among the overall high-performing countries. Like other urban centers in this study, see Figure 3 above, factors that determined Zürich's high positions in these rankings are energy, pollution, and emissions. Regarding energy, the number of green buildings is higher in Switzerland than in comparable countries (Salvi and Syz, 2011). According to Salvi and Syz (2011), the public sector played a pivotal role in supporting the market for green buildings. Since the late 1990s, Swiss governments provided many direct incentives including subsidies, grants, favorable loans, tax credits, and rebates that directly supported these buildings. There are numerous case studies in Switzerland that prove how pivotal the role of politics can be (and is) in creating the conditions for successfully developing an environmentally friendly society that also contributes to tackling climate change.

Figure 3. SDG (Sustainable Development Goals) Index Score 2019. Cities in Germany, Switzerland, and Scandinavian countries, among others, are ranked very high in the index–https://euro-cities.sdgindex.org/#/ (accessed December 31, 2021).

Also in Zürich, the Sihlcity megaproject should be highlighted (Theurillat and Crevoisier, 2013), the first big “urban entertainment center” (UEC) in Switzerland (Theurillat and Crevoisier, 2013: 11). See Figure 4 below. While there isn't space here to elaborate (we recommend reading Theurillat and Crevoisser's case study), it will suffice to say that the way this urban entertainment center was built (following the city council's guidelines that aim to drastically reduce traffic, encourage people to use collective passenger transport, and reduce pollution), shows that financial actors do take sustainability into account when political actors force them to do so. The goal of corporations, magnates of industries, etc. is to capitalize on their projects, to realize net profit. When political administrations that espouse environmentalism use their (indeed many) available tools to undermine the possibility of profit unless projects comply with environmental guidelines, fruitful negotiations, as in the case study cited above, lead to a compromise. The traffic model that developed in Zürich following the Sihlcity project became embedded, reducing car traffic by one-half and thus pollution. Many other projects in Zürich, and in Switzerland more widely, have followed this model. One of them is MFO-Park in Zürich, a public park once home to the extensive works of Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon (MFO). See Figure 5 below.

Figure 4. Sihlcity is a shopping mall in Zurich in the Wiedikon district. Source: https://www.greenroofs.com/projects/sihlcity-shopping-centre-living-facade/ (accessed January 9, 2022).

Figure 5. MFO-Park in Zürich–a public park once home to the extensive works of Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon (MFO). It has been rebuilt as a green area. Source: https://www.zuerich.com/en/visit/attractions/mfo-park (accessed December 24, 2021).

On the subject of urban centers, pollution, and traffic, Oslo is an excellent case study of an exemplary sustainable community. Research has shown that the main contributor to nitrogen dioxide (NO2)10 concentration levels in Oslo was diesel exhaust (Santos et al., 2020). Since 2004, the political administrations adopted some countermeasures to lower these levels, but the results were unsatisfactory. In 2015, after Norway was summoned by the ESA (the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) Surveillance Authority) for breaches of the AQD (Air Quality Directive 2008/50/EC, 2008)11 and found guilty by EFTA, attention to NO2 levels grew considerably. The political authorities (both local and national) enacted a number of environmental policies to reduce NO2 levels and comply with AQD, including: (1) increasing tolls that provide access to the inner parts of the city; (2) establishing low emission zones (LEZs); (3) allowing temporary free public transport; (4) allowing odd–even days driving (private cars can only circulate on either odd or even days, based on the last digit of their license plate numbers); (5) defining priority lanes for low-emission vehicles; and (6) imposing higher parking fees. The changes that this policy produced cannot, and should not, be underestimated. In only a few years (2015–2022), Oslo has become one of the cities with the highest air quality in Europe—and beyond. Dropping NO2 levels has also had positive repercussions on the number of zero-emission vehicles. For example, around 59% of new cars sold in Oslo in 2018 were electric vehicles—a fact that is closely linked to high tolls for entering the city center and parking, that owners of electric cars do not pay (they pass and park for free), coupled with state incentives to buy electric cars.12

Santos et al.'s study (Santos et al., 2020) concludes that the most effective measures in Oslo were, in fact, the creation of low-emission zones and parking fees (a measure also taken in other countries such as Amsterdam in the Netherlands). But for this to happen, a synergy between national and local administration was needed. It should be noted that some tensions exist between local and national governments in Norway as well as in most of the other exemplary green nation-states investigated in this study. This is particularly notably when considering that, in stark contrast to the progressive approach of cities such as Oslo, the Norwegian government insists not only on continuing to drill for oil and gas, but has also vowed to explore new oilfields. This does not mean that the national government does not encourage sustainability by supporting municipalities in their efforts. Indeed, these should not be seen as two different entities but as two parts of the same system: the nation-state system. For example, in 2017 the Norwegian Government changed traffic legislation to allow environmentally differentiated toll fees. In this system, vehicles that pollute the most pay more (according to fuel type, Euro standard, type of car, etc.). More attention by the government was complemented by a progressive political coalition in Oslo that understood the importance of a significant transformation of the city with respect to sustainability. Increased attention and focussed policy resulted in Oslo being ranked in the top five most sustainable cities in 2019, and in the same year it was named European Green Capital. Like other awards, European Green Capital is meant to put the city on a pedestal, to represent it as a role model capable of inspiring other cities to promote environmental practices. This inevitably increases people's pride, evidenced by the highest grades of satisfaction for quality of life registered in Oslo's surveys through the years. 13

The environmental emergency and life crisis faced by humankind requires a radical and immediate coordination effort at the global level. In other words, we have to swiftly move from multilateral action to some yet-to-be-born form of simultaneity and synchronicity never previously encountered (Conversi, 2020a,b, 2021b, 2022). However, the world is still divided into nation-states and these provide the building blocks for all international organizations and agreements. Moreover, nearly all states in the world rest on the modern doctrine of nationalism. So, we face a painful contradiction: we want to move fast into a better world able to tackle the ongoing crises, but this world doesn't move quickly enough, largely because it is divided by petty interests dispersed along national gridlocks. It would thus be tempting to dismiss nationalism simply as a fastidious nuisance or an obstacle—which, to a certain extent, it is. This article has attempted to show that there are, however, powerful, inspiring examples of increased sustainability, even among existing nation-states. We have found and identified cases in which a new form of “national pride” has ostensibly emerged as a response to the global crises—yet it is still formulated within the parameters of existing nation-states. This is no longer the sort of pride spurred by interstate competition as has occurred over the last few 100 years. It is a pride based on achievements that can be shared across borders, even while the first beneficiaries are those living within the national boundaries. These achievements instill pride, delight and pleasure about our country's national identity because they move the country ahead of others in a way that can benefit others as well. In many respects, the form of green nationalism identified here marks a departure from the kind of interstate competition that has characterized nationalism until now. Competition has not gone, but in some cases it has moved to a new arena: the country with the lowest carbon footprint and the most progressive climate politics “wins” or gains the most prestige. And competition is not the only element; certainly there is much comparison between countries trying to climb the ladder of environmental indexes and/or win awards for the greenest city and/or nation. One might call this phenomenon the new “green cool”, characterized by local and national polities combining to lower their carbon footprint while promoting themselves as the most progressive communities in terms of climate politics.

The experience of selected European countries, namely Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland, and Germany, seems to indicate that there are viable alternatives to the classical obstructionist form of nationalism that has so far prevailed in the international state system during climate negotiations. Such obstructionist attitudes have emerged, and have often prevailed, in successive Conference of the Parties (COPs), the crucial meetings of representatives of countries that have previously agreed to specific targets, such as the UN Climate Change Conference Conventions, the Convention on Biological Diversity, or the Kyoto Protocol—but also the Chemical Weapons Convention or the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. The positive examples cited here turn out to be in sharp contrast with the worst environmental offenders, such as the USA, Russia, Brazil or, possibly, China and India. The latter have long been run by economic regimes that place primary importance on some sort of resource nationalism that negatively affects their own populations as well as the rest of the world. They are counterexamples of what does—and does not—need to be done. Our selection is limited to European cases, but it would also be instructive to consider non-European examples, both at the state and at the local level. It is indeed part of our long-term plan to look at the exemplarity of specific regions and nation-states in the developing world as well as smaller communities scattered across the globe—elsewhere identified as “exemplary ethical communities” (Conversi, 2021a).

We finally conclude that these forms of sustainable nationalism, whose characterizing elements involve a tradition of environmental ideals, environmental activism, environmental policy, and sustainable practices in the long-run, can function as inspiring lights to be followed, to various degrees and in different ways, by other countries. The idea of “exemplarity” is intended here as a new form of communitarian collaboration constructed around the pillar of environmentalism to achieve sustainable goals along the lines of “exemplary ethical communities”, at local, regional, substate, national, or plurinational levels (Conversi, 2021a). Thus we hope to shape an emerging new field of research that combines sustainability, community-building, and nationalism in a way that can help develop broader participative scenarios during the current green transition.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

DC and LP have made a substantial contribution to the field of nationalism studies and climate change, particularly focusing on the relationship between the two, and have expanded and applied to new cases the novel concept of green nationalism in the face of approaching cataclysms. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^See Goldin's ‘Divided Nations: Why global governance is failing and what can be done about it?' for an exhaustive reading on how international organizations, so far, have failed in tackling climate change.

2. ^The Anthropocene boundary is a ‘formal chronostratigraphic unit – defined by a GSSP, a Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point' (Waters et al., 2016).

3. ^Data shows that in February 2021 over three-quarters of vaccines were available in just 10 countries that account for 60% of global GDP (WHO, 2021).

4. ^The Environmental Performance Index was developed by Yale University (Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy) and Columbia University (Center for International Earth Science Information Network) in collaboration with the World Economic Forum and the Joint Research Center of the European Commission. It is a method of quantifying and numerically marking the environmental performance of a state's policies.

5. ^An index that evaluates and compares the climate protection performance of 63 countries and the European Union, which together are responsible for more than 90% of global greenhouse gas emissions. See https://germanwatch.org/de/19552#CCPI2021 for details (accessed December 25, 2021).

6. ^Fältbiologerna has been active since the 1940s.

7. ^A recent survey by the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) reports that 76% of Germans believe their country rightly committed itself to the preservation of biodiversity, around 90% stated that biodiversity in nature promotes their well-being and quality of life, and 83% inform themselves (or is willing to do so) about current developments in the field of biodiversity and draws the attention of their friends and acquaintances to biodiversity conservation.

8. ^Other factors, i.e., income levels, must also be taken into account. As green buildings still cost more, on average, than traditional ones, income levels play an important role. Evidence collected by Salvi and Syz (2011) support this thesis.

9. ^In 2021, the Norwegian Green Party (Miljøpartiet Dei Grøne) achieved 3.8% of the votes in the general election, becoming the third largest party in major cities like Oslo and Trondheim. Until 2009, the party received very little attention, scoring an insignificant 0.03% (2009), 0.01% (2005), and 0.02% (2001).

10. ^Elevated levels of NO2 are generally known to damage the human respiratory tract and increase a person's vulnerability to, as well as the severity of, respiratory infections and asthma.

11. ^Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on Ambient Air Quality and Cleaner Air for Europe (2008) O.J. L 152/1. Quoted in Santos et al. (2020).

12. ^Oslo has the highest number of electric vehicles per capita in the world, according to the municipal government. See https://www.regjeringen.no/en/topics/transport-and-communications/veg/faktaartikler-vei-og-ts/norway-is-electric/id2677481/ (accessed January 9, 2022).

13. ^Surveys on ‘Quality of life in European cities' are available at https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/maps/quality_of_life/ (accessed 9 January 2022).

Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Anselm, J., Haikola, S., and Wallsten, B. (2018). Politicizing environmental governance – A case study of heterogeneous alliances and juridical struggles around the Ojnare Forest, Sweden. Geoforum 91, 206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.03.003

Badische, Z. (2014). Alles Oeko, oder was? Available online at: https://www.badische-zeitung.de/alles-oeko-oder-was-86895970.html (accessed June 21, 2021).

Baird, R. (2008). The Impact of Climate Change on Minorities and Indigenous Peoples. London: Minority Rights Group International.

Balistier, T. (1996). Straßenprotest: Formen oppositioneller Politik in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland zwischen 1979 und 1989. Münster: Westfälischer Dampfboot.

Beck, U. (2004). Cosmopolitical realism: On the distinction between cosmopolitanism in philosophy and the social sciences. Glob. Netw. 4, 131–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2004.00084.x

Beck, U. (2011). Cosmopolitanism as imagined communities of global risk. Am Behav Sci. 55, 1346–1361. doi: 10.1177/0002764211409739

Beck, U. (2016). The Metamorphosis of the World.. How Climate Change Is Transforming Our Concept of the World. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

Beck, U., and Sznaider, N. (2006). Unpacking cosmopolitanism for the social sciences: A research agenda. Br. J. Sociol. 57, 1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2006.00091.x

Blackbourn, D.å. (2006). The Conquest of Nature: Water, Landscape, and the Making of Modern Germany. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Brockers, W. (2016). Mönchengladbachs Historische Momente. Norderstedt: Studien zur Stadtgeschichte.

Brown, A. (2017). The dynamics of frame-bridging: Exploring the nuclear discourse in Scotland. Scott. Aff. 26, 2, 194–211. doi: 10.3366/scot.2017.0178

Brubaker, R. (2015). Grounds for Difference. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. doi: 10.4159/9780674425293

Buehler, R., and Pucher, J. (2011). Sustainable transport in Freiburg: Lessons from Germany's environmental capital. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 5, 1, 43–70. doi: 10.1080/15568311003650531

Bundesregierung. (2021). Vereint im Schutz von Umwelt und Natur. Available online at: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/suche/30-jahre-umweltschutz-1789792 (accessed June 21, 2021).

Calhoun, C. (2003). ‘Belonging' in the Cosmopolitan Imaginary. Ethnicities. 4, 531–568. doi: 10.1177/1468796803003004005

Chomsky, N., and Pollin, R. (2020). Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet. London: Verso.

Chrun, E.Dolšak, N., et al. (2016). Corporate environmentalism: motivations and mechanisms. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 41, 341–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-090105

Coates, G. J. (2013). The sustainable urban district of Vauban in Freiburg, Germany. Int J Des Nat Ecodynamics. 8, 265–286. doi: 10.2495/DNE-V8-N4-265-286

Colville-Andersen, M. (2018). Copenhagenize: The Definitive Guide to Global Bicycle Urbanism. Washington: Island Press. doi: 10.5822/978-1-61091-939-5

Conversi, D. (2012). Modernism and nationalism. J Political Ideol. 17, 13–34. doi: 10.1080/13569317.2012.644982

Conversi, D. (2014). “Modernity, globalization and nationalism: The age of frenzied boundary-building”, in Nationalism, Ethnicity and Boundaries: Conceptualising and Understanding Identity through Boundary Approaches, Jackson, J. Molokotos-Liederman, L. (eds.). Abingdon, UK: Routledge. p. 57–82.

Conversi, D. (2016). Sovereignty in a changing world: from Westphalia to food sovereignty. Globalizations. 13, 484–498. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2016.1150570

Conversi, D. (2020a). “The future of nationalism in a transnational world”, in The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Race, Ethnicity, and Nationalism, Stone, J., Dennis, R., and Rizova, P. (eds). London: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 43–59. doi: 10.1002/9781119430452.ch3

Conversi, D. (2020b). The ultimate challenge: Nationalism and climate change. Nationalities Papers. 48, 625–636. doi: 10.1017/nps.2020.18

Conversi, D. (2021a). Exemplary ethical communities. A new concept for a livable Anthropocene. Sustainability. 13,5582. doi: 10.3390/su13105582

Conversi, D. (2021b). “Geoethics versus Geopolitics. Shoring up the nation in the Anthropocene cul-de-sac”, in Geo-societal Narratives: Contextualising Geosciences, Bohle, M. Marone, E. (eds). Cham: Springer International. p.135–152. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-79028-8_10

Conversi, D. (2022). “Ernest Gellner in the Anthropocene. Modernity, nationalism and climate change”, in Ernest Gellner Legacy and Social Theory Today, ed Petr Skalník (New York, NY: Springer).

Conversi, D., and Ezeizabarrena, X. (2019). “Autonomous communities and environmental law: The Basque case”, in Minority Self-Government in Europe and the Middle East, Akbulut, O., and Aktoprak, E. B. (eds). Leiden: Brill Nijhoff. p. 106–130. doi: 10.1163/9789004405455_006

Conversi, D., and Friis Hau, M. (2021). Green nationalism. Climate action and environmentalism in left nationalist parties. Environm. Politi. 30, 1089–1110. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2021.1907096

Corlett, R. T. (2012). Climate change in the tropics: The end of the world as we know it? Biol. Conserv. 151, 22–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.11.027

Crutzen, P. J., and Stoermer, E. F. (2000). The ‘Anthropocene', global change. Newsletter. 41, 17–18. doi: 10.12987/9780300188479-041

Cullenward, D., and Victor, D. G. (2020). Making Climate Policy Work. Cambridge: Polity Press /John Wiley & Sons.

Daseking, W. (2015). Freiburg: Principles of sustainable urbanism. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 8, 145–151.

Doherty, T. J., and Clayton, S. (2011). The psychological impacts of global climate change. Am. Psycholog. 66, 265. doi: 10.1037/a0023141

Duara, P. (2021). Nationalism and the crises of global modernity (The Ernest Gellner Nationalism Lecture). Nat. National. 27, 3, 610–622. doi: 10.1111/nana.12753

Dryzek, J. S., Hunold, C., Schlosberg, D., Downes, D., and Hernes, H. K. (2002). Environmental transformation of the state: the USA, Norway, Germany and the UK. Polit. Stud. 50, 659–682. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.00001

Eriksen, T. H. (2009). Living in an overheated world: Otherness as a universal condition. Acta Historica Universitatis Klaipedensis. 19, 9–24.

Eriksen, T. H. (2016). Overheating: An Anthropology of Accelerated Change. London: Pluto Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt1cc2mxj

Eriksen, T. H. (2021a). The loss of diversity in the Anthropocene biological and cultural dimensions. Front. Polit. Sci. 3, 104. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.743610

Eriksen, T. H. (2021b). Standing still at full speed: Sports in an overheated world. Front. Sports Act. Living. 3, 123. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2021.678987

Eriksen, T. H., and Schober, E. (2017). Knowledge and Power in an Overheated World. Oslo: Department of Social Anthropology, University of Oslo.

Fletcher, R. (2019). Ecotourism after nature: Anthropocene tourism as a new capitalist ‘fix'. J. Sustain. Tour. 27, 522–535. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2018.1471084

Fraker, H. (2013). The Hidden Potential of Sustainable Neighborhoods. Lessons from Low-Carbon Communities. New York: Springer. doi: 10.5822/978-1-61091-409-3

Freeman, A. M. (2002). Environmental policy since Earth Day I: What have we gained? J Econ Perspect. 16, 125–146. doi: 10.1257/0895330027148

Gelter, H. (2000). Friluftsliv: The Scandinavian philosophy of outdoor life. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 5, 1, 77–92.

HadŽidedi,ć, Z. (2022). Nations and Capital: The Missing Link in Global Expansion. London: Routledge.

Heidenblad, D. L. (2021). The emergence of the modern environmental movements, 1959–1972, in The Environmental Turn in Postwar Sweden, Heidenblad D. L. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 144–167. doi: 10.7765/9789198557749

Ingebritsen, C. (2012). Ecological institutionalism: Scandinavia and the greening of global capitalism. Scand. Stud. 84, 87–97. doi: 10.1353/scd.2012.0011

Jamieson, D. (2014). Reason in a Dark Time: Why the Struggle against Climate Change Failed – and What It Means for Our Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199337668.001.0001

Kaijser, A., and Heidenblad, D. L. (2018). Young activists in muddy boots. Faltbiologerna and the ecological turn in Sweden, 1959–1974. Scand. J. Hist. 43, 301–323. doi: 10.1080/03468755.2017.1380917

Kaiser, R. (2018). ‘Germany's resource efficiency agenda: Driving momentum on the national level and beyond', in Factor X: Challenges, Implementation Strategies and Examples for a Sustainable Use of Natural Resources. Lehmann, H. (eds). Cham: Springer. p. 213–232. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-50079-9_13

Klausen, J. E., and Opedal, S. (2019). The ‘ifs' and ‘hows' of participation: NGOs and sectoral environmental politics in Norway, in The Nordic Environments: Comparing Political, Administrative and Policy Aspects. Joas, M., and Hermanson, A.-S. (eds). London: Routledge. p. 183–208. doi: 10.4324/9780429443084-9

Kunze, I., and Philipp, A. (2013). The Eco-District of Vauban and the co-housing project GENOVA, case study report. TRANSIT: EU SSH. 2–1.

Levene, M., and Conversi, D. (2014). Subsistence societies, globalisation, climate change and genocide: Discourses of vulnerability and resilience. Int. J. Hum. Rights. 18, 281–297. doi: 10.1080/13642987.2014.914702

Loh, J., and Harmon, D. (2005). A global index of biocultural diversity. Ecol. Indic. 5, 231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2005.02.005

Maleševic, S. (2013). Is nationalism intrinsically violent? Natl. Ethn. Politics. 19, 12–37. doi: 10.1080/13537113.2013.761894

Malešević, S. (2019). Grounded Nationalisms: A Sociological Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108589451

Mandelbaum, M. M. (2020). The Nation/State Fantasy.. A Psychoanalytical Genealogy of Nationalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-22918-4

McKeon, N. (2015). La Via Campesina: The ‘peasants' way' to changing the system, not the climate. J. World-Syst. Res. 21, 241–249. doi: 10.5195/jwsr.2015.19

McNeill, J. R. (2000). Something New under the Sun. An Environmental History of the Twentieth-Century World. New York: Norton.

McNeill, J. R., and Engelke, P. (2016). The Great Acceleration: An Environmental History of the Anthropocene since 1945. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press/Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

OHCHR. (2021). OHCHR and Elections. Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Pages/HRElections.aspx (accessed June 28, 2021).

Østli, V., Fridstrøm, L., Kristensen, N. B., and Lindberg, G. (2021). Comparing the Scandinavian automobile taxation systems and their CO2 mitigation effects. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 1–18. doi: 10.1080/15568318.2021.1949763

Posocco, L., and Watson, I. (2022). Green Nationalism: The Bonding between Nationalism and Environmentalism in Vauban, Sustainable District Near The French-German Border. Nations and Nationalism. doi: 10.1111/nana.12823

Reuters (2021). Norway's plans to raise carbon tax draw oil industry ire. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-climate-change-norway-idUSKBN29D1BD (accessed January 3, 2022).

Ridanpää, J. (2021). ‘Carbon footprint nationalism': Re-conceptualizing Finnish nationalism and national pride through climate change discourse. Natl. Identities. 1–18. doi: 10.1080/14608944.2021.1937974

Salvi, M., and Syz, J. (2011). What drives ‘green housing' construction? Evidence from Switzerland. J. Financ. Econ. Policy. 3, 86–102. doi: 10.1108/17576381111116777

Santos, G. S., Sundvor, I., Vogt, M., Grythe, H., Haug, T. W., Høiskar, B. A., et al. (2020). Evaluation of traffic control measures in Oslo region and its effect on current air quality policies in Norway. Transport Policy. 99, 251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.08.025

Selle, P., Strømsnes, K., Svedberg, L., Ibsen, B., and Skov Henriksen, L. (2019). “The Scandinavian organizational landscape: Extensive and different”, in Civic Engagement in Scandinavia. Volunteering, Informal Help and Giving in Denmark, Norway and Sweden, Skov, L., Strømsnes, H. Svedberg, L. Springer Nature Switzerland. 33–66. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-98717-0_2