- 1School of Humanities and Social Science, Chinese University of Hong Kong Shenzhen, Shenzhen, China

- 2Division of Social Science, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China

Drawing data collected in 2021 from a probability sample of Hong Kong residents, we examine their political identity with the former colonists and their post-colonial ruler in China. The data show an expected anti-China sentiment but an unexpectedly lukewarm attitude toward their former colonists. Instead, the survey respondents expressed strong feelings toward indigenization with traditional Chinese culture. For the sources of such sentiment, this paper finds that the anti-Mandarin language policy, the post-1997 anti-establishment education policy, and the anti-China media are particularly important reasons. This study attributes the trend of post-colonial indigenization to the political vacuum left by the departure of the old ruler and the new ruler's inability to indoctrinate the newly ruled under the postcolonial institutional design of One Country Two Systems. This trend of indigenization is likely to tilt toward identity with the Chinese state as China is stepping up its effort to make the territory more China-friendly.

Introduction

In 2020, China passed its National Security Law for Hong Kong, demanding its residents' political loyalty and outlawing any anti-China behavior. The Hong Kong National Security Law marks a turning point, and it symbolized the end of the first stage of postcolonial Hong Kong. This study examines Hong Kong residents' feelings of political identity during the first phase of the postcolonial era. It looks at such identity in three dimensions, Hongkongers' sentiments toward China, to the West, and to traditional Chinese culture. It shows that while Hongkongers are predictably distant from China, they are also surprisingly indifferent toward the West. In the meantime, they show a strong feeling of identity with Chinese traditional culture. This paper further shows how Hong Kong's education system, media freedom, and language policy played important roles in shaping Hongkongers' political identity in the past 23 years since Hong Kong's return to China in 1997.

Competing Theories of Postcolonial Identity

The study of postcolonial societies gained its momentum since the 1980s, following waves of decolonization and the detachment of former colonies from their European colonial powers, together with the rise of post-industrial western intellectual trends of critical race theory, feminism, globalization, and so on (Gandhi, 1998; Elam, 2019). Many studies in this field examine the relationship between people in the former colonies and their former colonial rulers. Others focus more on the relationship between the former colonies and their new regimes and local leaders.

Some studies show the continuity of colonial rule and colonial mentality in postcolonial societies (Fanon, 1967, 2004; Guha, 1982; Spivak, 1988; Said, 1994; Paolini et al., 1999; Brysk et al., 2002; Chatterjee, 2004). These scholars point to the stereotypification of the formerly colonized in the postcolonial present as inferior, “indolent, thoughtless, sexually immoral, unreliable and demented” (Bressler, 2007). Some researchers attribute the identity construction to the colonial system and western culture in light of political discourse and psychoanalytic theory. For example, Fanon (1967) postulates that the formation of identity is the product of a belief system of Western superiority, whereas Said (1994) reminds us that the brainwashing by colonial powers ingrains a lopsided relationship, culture, and a low individual self-regard in the colonized society, resulting in the loss of identity. To restrain from being debased and perceived as primitive, the colonized individuals reduce their native identity by wearing “white masks” to cope with the West, as Dizayi (2019) recapitulated. Other studies examine the dominant class and foreign elite (Guha, 1982; Spivak, 1988), colonial government administration (Scott, 1995; Chatterjee, 2004; Young, 2020), education and language policy (Venn, 2000; Bahri, 2003; Ramanathan, 2005) as determinants for postcolonial identity. In short, these studies highlight the persistent effect of colonial power after its retreat (Spivak, 1988; Said, 1994; Richards, 2010).

Other postcolonial theorists, however, describe postcolonial identity as a hybrid construct (Bhabha, 1994; Young, 2020) that emerges as a new local identity (Ashcroft et al., 1995). They adopt the concept of “cultural identity”, as Hall (1990) suggested, which undergoes a continual renovation according to the interaction between colonial and local cultures. Bhabha (1990, 1994), a leading postcolonial theorist, argues that the hybridization of identities and cultures under colonial rule leads to the emergence of a new socio-political identity of the colonizer and the colonized, despite being wary of such hybridity as signifying an unstable colonized culture, potentially camouflaging the colonial oppression and social inequalities (Gandhi, 1998; Rukundwa and Aarde, 2007). Loomba (1998) and Young (2020) contend that such identity is not entirely new, nor does it replicate the old native culture. Instead, it is “dislocated”, fragmented, and hybrid under the conflictual interactions of the colonial hegemony and the colonized. Therefore, according to the constructivist view, identity is ever-changing and is shaped by externalities, such as international support (Han, 2016, 2019), rather than being settled or internalized completely, and through the related historical negotiation and renegotiation process, as Bammer (1994) and Ang (2001) summarized.

Being a former British colony and reunified with China, its biological parent, Hong Kong has long been one of the atypical subjects of postcolonial identity for scholars (Kuan and Lau, 1989; Lau, 1992; Wong, 1997; So, 2005, 2015) because they observed Hong Kong identity as neither British nor Chinese since the British colonial government had no intention of building a British identity for Hong Kong citizens (Chan, 1994; Wong, 1997) under its laissez-faire and de-ethnicization policy orientation (Leung, 1997; Xiao, 1997). Intellectuals argued that the identity of Hong Kong citizens in the colonial and postcolonial era were therefore ambiguous in a quasi-city state, with high recognition of Chinese cultural or ethnic identity but a weak Chinese national identity (Wong, 1997; Lau, 2017). Dynamic forces, including British colonial legacy, Hong Kong indigenization, and Chinese ideology, are accountable for identity formation in postcolonial Hong Kong.

Some scholars assume that the early Hong Kong identity emerged from its distinctive culture during the 1950s when the border closure policy between Hong Kong and China was enacted (Baker, 1983; Lau and Kuan, 1988; Choi, 1990; Carroll, 2005; Law, 2015). Such immigration policies that restrain Hong Kong from connecting with Mainland China, marked the identity-building departure from China (Ku, 2004; Lau, 2017). British colonial government further constructed a sense of belonging and citizenship of Hong Kong residents through various policy reforms after the 1966 and 1967 riots, such as partially introducing elections, promoting Hong Kong's economic model and its achievement, extending the sense of pride of being Hong Kong citizens, and implanting Western liberal ideas of human rights, judicial independence, and freedom of speech (King, 1975; So, 1999; Lam, 2004; Law, 2015).

As a result, some studies argue that Hong Kong identity was formed far from Chinese identity due to different political, economic, and social experiences (So, 1999; Ku, 2004; Mathews et al., 2008; Lau, 2017; Lam, 2018; Law, 2018). Even though the riots in the 1960s revealed a Chinese ethnic identity, these authors insist that the recognition of Chinese identity could hardly rise due to widespread condemnation of the pro-China leftist riots (Cheung, 2012; Lau, 2017). On the other hand, such condemnation may serve as evidence of the existence of a pro-China sentiment in Hong Kong's social unrest in the 1960s. In this sense, the early anti-colonial movement in Hong Kong was not an indigenous movement but with China's backup from cross the border.

Law (2015), alternatively, analyzed that while the post-colonial government opposed to attaching Hong Kong identity to colonial legacies, it feared that developing a new Hong Kong identity based on the China-backed new governing system would hurt the vested interest of the middle class and elites and create social instability. So, the post-colonial government endeavored to maintain Hong Kong citizens' political neutrality so it can buy time and develop the pro-establishment and patriotic forces, whilst avoiding any alteration of the status quo. Some scholars expected a potential clash of Chinese and Hong Kong identities (Wong, 1997). They noticed a gradual weakening of the identification with China, and predicted the rise of localism, self-determination, direct elections, and even Hong Kong independence as the ultimate political goals (Lam, 2018; Law, 2018; Ma, 2018).

Indigenization of Political Identity in Postcolonial Hong Kong

We define political identity as an individual's sense of belonging to a political entity. Normally, this political identity is embodied by a geographic region and the governing body representing that region. In case the governing body is detached from the region, as in the post-Handover Hong Kong, people may experience a political identity crisis, and see cultural identity as a shelter through which they can find emotional comfort. This is a process that can be described as “indigenization” of political identity.

This study will show that postcolonial Hong Kong has gone through a process of indigenization since its return to China by the United Kingdom (UK) in 1997—a process of returning to traditional Chinese culture as a symbol of political identity. By indigenization this study does not mean to imply primitiveness. Instead, it means the tendency of going back to the native culture. Studies of ethnic and national identities show that native culture and belief systems play an important role in shaping people's sense of community and political identity (Smith, 1995, 1998). The state normally provides the foundation for political identity (Gellner, 1983). Cultural identity can be used as political identity if the state fails to do so, such as in postcolonial Hong Kong.

In a lose sense, indigenization overlaps with localization. This study, however, prefers the concept of indigenization over localization because indigenization focuses more on traditional culture and draws a clearer distinction from both colonialism and the Chinese political identity. Localism in post-Handover Hong Kong, on the other hand, does not draw such distinction, particularly from the territory's colonial past.

Hong Kong's postcolonial indigenization is formulated by several forces. First, it is shaped by the political vacuum left by the departure of the British colonists. Hong Kong was ruled by the UK for 150 some years and thus was used to think they were the subjects of their colonial rulers but now that the colonial ruler is gone, and there is a need to find a new collective identity. The colonial infrastructure may still be in place and functioning well, such as public services, but the sense of collective belonging is lost by the UK's departure, and thus the vacuum was created.

This political vacuum did not exist in some other postcolonial societies. In the cases of India and South Africa, for example, the colonists literally created the modern states and then lost them to the local elites. The local elites as new rulers continued with the same political systems and therefore the same political identity as their colonial rulers, such as in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and many others. In these societies, political power returned to the native people, yet the political system stayed in the colonial legacy. Admittedly even in many of these societies, there is a significant local adaptation of the colonial system, yet the political institutions such as political parties and elections are mostly adopted by the local elites. Hong Kong was not that lucky, in the sense that the UK did not leave a functional political-institutional design for the local elites to adopt.

Second, indigenization was created by the need to resist being identified with their supposedly newly rich but unsophisticated new ruler. Hong Kong is one of those postcolonial societies (together with Macau) where the colonists did not build a modern state. When they left, they returned a piece of land that they “rented” some 150 years ago from its owner, who, at the time of regaining control of the territory, had never lived under the British colonial rule. The new rulers, understandably, demand Hong Kong people's new political identity. China is perceived as powerful but it's a nouveau riche (tucaizhu) and often acts without style (xiangbalao). Among many other things that the Hongkongers are proud of comparing with the mainlanders, Hong Kong has the best and most efficient public transit, the best mixture between the Eastern and the Western cultures, and a rare combination of natural environment and modern high rises, while in China hardware (infrastructure) was indeed developed very fast, but people are still much less exposed to the outside world. Mainland tourists in Hong Kong are often portrayed as loud, dirty, rude, and disorderly (Kaphle, 2013; Li, 2013, 2014).

Third, the One Country Two Systems policy, at least for the first 23 years after Hong Kong's return to China in 1997 and before the National Security Law was passed on July 1, 2020, facilitated the feeling of political distance between Hong Kong and China, and further strengthened the vacuum left by the UK in which indigenization of Hong Kong identity took place. The Two Systems idea and China's relative inability to establish its desired political socialization process in the first 23 years further encouraged Hongkongers to keep the two political systems separate. Many people may think PRC already intervened a lot during this time (Maizland and Albert, 2021), yet by other standards PRC tolerated many things that its leaders would never allow in China, such as the yearly parade on June 4 in memory of the “1989 Tiananmen massacre”, not mentioning the numerous large scale opposition movements and protests. This reluctant hands-off policy further encouraged the growing impact of the anti-China elements who wanted to keep Hong Kong away from Chinese influence (Yan, 2015).

Next, indigenization was further encouraged by the availability of traditional culture. Luckily Hong Kong's native culture is very rich, highly developed, and well preserved. Such culture, unique in some respects, such as the spoken language, local diet, social norms, etc., overlaps with Chinese culture in many other ways such as the written language, literature, philosophy, religious beliefs, traditional holidays, and so on. The difference between Hong Kong and China is that, in China, political identity is based on the Chinese state, while cultural identity in Hong Kong became a political identity due to the lack of other attractive options.

Finally, some studies show that there has always been a tradition of indigenization in Hong Kong under the British rule. For example, the 1967 riot and contention of indigenous villagers were attempts to resist British rule under the slogan of returning to traditional culture (Chan, 1998; Law, 2018). If this is true, indigenization is a continuity from the old rule to the new one. One question is the nature of indigenization. Under British rule, news reports show that such movement had a strong backing from the PRC, and the British colonial government closed down the pro-PRC newspapers and arrested CCP-sympathizers in its effort to crack down the 1967 riots (FCCHK, 2017; Webster, 2021). In the post-colonial era, it remains to be seen if this indigenization process differs from that under colonial rule.

In this environment, being pushed away by the colonialists while trying to resist the pull from China, traditional culture is a natural psychological fallback.

Based on the above discussion, this article will test the following four hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Hong Kong residents are expected to express weak political identity toward the Chinese state;

Hypothesis 2: Hong Kong residents are expected to show lukewarm feelings toward their former colonial rulers;

Hypothesis 3: Hong Kong residents are expected to show strong feelings toward Confucian-based East Asian identity and toward Chinese culture;

Hypothesis 4: The reluctant laissez-faire policies in education, language, and media freedom under the One Country Two Systems are expected to further promote indigenization.

Data and Measures of Political Identity

The empirical evidence for this study is drawn from the Hong Kong Political Culture Survey conducted by Professor Wenfang Tang and his survey research team. The face-to-face questionnaire survey was carried out among 3,744 respondents from late May to mid-September in 2021. The probability sample was drawn from 72 randomly selected electoral districts out of 452 total districts. In each district, 52 respondents were interviewed based on the proportion of demographic information from the census data in terms of gender, age, education, income, and housing type. The interviews were conducted on tablets, and each interview lasted about 30 min. The questionnaire included many questions related to the respondents' political attitudes ranging from political identity, policy satisfaction, political trust, social tolerance and social trust, religious values and behavior, law and order, political participation, media consumption, and embedded survey experiments on social desirability and media effects.

This study will use the following questions from the above survey to test the respondents' political and ethnic identities:

1. Cultural and political nationalisms. Please tell us how much you agree with the following statements (agree strongly, agree, disagree, disagree strongly):

a. Chinese civilization has great vitality;

b. Chinese culture is one of the most advanced in the world;

c. I will support Chinese national teams in sports games;

d. I like Chinese movies and TV shows;

e. China's political system is superior to Western liberal democratic systems;

f. Only the Chinese Communist Party is capable of leading China to be a world power.

2. National images of selected countries and regions. Please tell us your impressions of people from the following countries and regions (very good, good, bad, very bad): Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, the UK, Mainland China, the United States, India, and the Philippines.

3. Political orientation. Which of the following colors best represent your political view (blue = pro-establishment, green = neutral, yellow = pro-democracy): dark blue, blue, light blue, green, light yellow, yellow, and dark yellow.

4. Ethnic identity. Would you call yourself Hongkonger, Chinese, or Chinese Hongkonger?

5. East-West value preference. Please tell us which set of values is more important to you? (Lau, 2017)

a. Freedom, democracy, human rights, and the rule of law;

b. Benevolence, integrity, filial piety, and restraint;

c. Both are important.

6. Immigration intention. In the next 2 years, do you plan to immigrate to Europe, North America, Japan, or Taiwan (yes or no)?

Pioneers of the study of Hong Kong identity during the transitional period suggested the abovementioned as vital elements to map out Hong Kong identity in multiple dimensions such as Chinese civilization, cultural identity, national vs. global values, political values (Lau and Kuan, 1988; Ma and Fung, 2007; Lau, 2017), and immigration intention (Lau, 1997; Zheng and Wong, 2002). For the sources of the above measures of political and ethnic identity, this study will analyze the effects of language, education, age, social class, birthplace, and media.

Language is measured by the respondents' ability to use English and Mandarin Chinese (or Putonghua—the common language). In the survey sample, 88% of the respondents' native language is Cantonese, 3% Mandarin, 1% English, and 7% other languages. Each language ability is an index of the respondent's ability to listen, speak, read, and write in either English or Mandarin. Mandarin is expected to improve China identity, and English is expected to promote pro-West sentiment.

Education level is measured from 0 (lowest) to 1 (highest), ranging from primary or below (0), lower secondary (0.25), upper secondary (0.5), sub-degree (0.75), and degree and above (1). The education sector in Hong Kong allegedly has been at the forefront of the anti-China social movements (Lee, 2021). If this allegation is true, education is expected to promote pro-West and anti-China feelings.

To compare the difference between the colonial era and the postcolonial era, dividing the survey sample into two age groups, 39 and younger in one group, and 40 and older in another group is necessary. Age 16 is considered to be the year when one completes political socialization during which one's political attitudes and values are taught (see Tang and Parish, 2000). If one turned to 16 in or before 1997, by the time of the survey in 2021, that colonial cohort should be 40 or older. The post-colonial cohort turned to 16 in 1998 or later. Twenty-three years later, in 2020, that cohort should be 39 or younger. Given PRC's reluctant hands-off policy in the post-colonial period, the postcolonial generation should be more anti-China than the older cohort.

Social class is measured by a question about the respondents' self-reported social status. It is divided into 5 categories, upper, upper middle, middle, lower middle, and lower classes. It is not immediately clear if the upper classes are more or less pro-China. There are reasons to believe that these people are expected to show their loyalty to China because their economic interests are more tied to the Mainland. Others would argue that these people are more exposed to Western values through their education and economic activities, and therefore expected to be more pro-West.

Place of birth will be included in the analysis. It is expected that those who were born in Hong Kong will be more anti-China than the respondents who were born in the Mainland.

Finally, media effect is measured by the respondents' reported usage of two media outlets, Apple Daily and Oriental Daily News, ranging from never, monthly, weekly, several times a week, daily, and several times daily. These two newspapers are chosen for two reasons. First, they are known for their political orientations. Apple Daily is known for its anti-China view and Oriental Daily News is considered to be pro-China (Yu, 2014). Second, these are the top two most popular paid newspapers among the 19 media outlets included in the Hong Kong Political Culture Survey1. On a scale from 0 (least popular) to 100 (most popular), Oriental Daily News ranks at the top (22%) and Apple Daily is the second most popular at 19%. Apple Daily is expected to encourage anti-China sentiment and Oriental Daily News will have an opposite effect.

Appendices 1, 2 show the coding schemes of the above variables and their summary statistics.

Levels of Political Identities in Hong Kong

This section will analyze the 6 measures of Hong Kong political identity described in the previous section, including (1) perceived identity with traditional Chinese culture and with the Chinese state, (2) preference for people from different countries and regions, (3) ideological orientation measured by political color, (4) perceived ethnicity, (5) preference for Eastern or Western values, and (6) intention to immigrate to the West.

The next section will further examine the sources of these political identity measures.

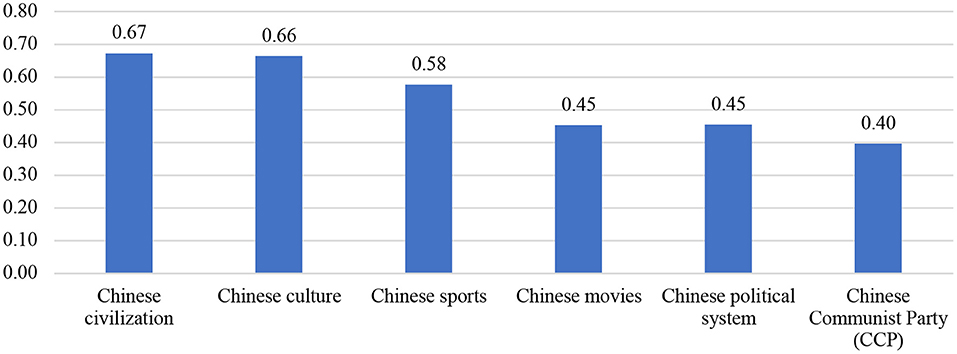

Figure 1 shows the respondents' assessment of 6 items related to China, including Chinese civilization, Chinese culture, Chinese movies/TV shows, Chinese sports, Chinese political system, and Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The top two highest scores are for Chinese civilization (0.67) and Chinese culture (0.66), followed by the other four significantly lower scores of Chinese sports (0.58), Chinese movies (0.45), Chinese political system (0.45), and the CCP (0.40). A factor analysis groups the 6 items into two categories, the first two in one and the remaining four in another. The factor behind the first two items is related to traditional Chinese culture and the factor behind the four items in the second category is related to the Chinese state. As shown in Appendix 2, the mean values are 0.67 for Chinese cultural identity or cultural nationalism (variable named as Cultural Nationalism), which is about 20% higher than the identity to the Chinese state, or political nationalism (0.47, variable named as Political Nationalism).

Figure 1. Respondents' level of support for six China-related items. Hong Kong Political Culture Survey 2021. The chart displays the level of support for six China-related items with the value ranging from 0 to 1, which 1 indicates the highest level of support. Figures are rounded off to the nearest hundredths.

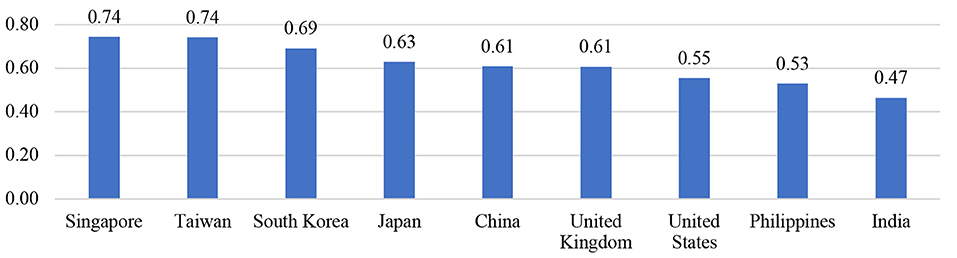

Figure 2 shows the Hong Kong respondents' feelings toward people from 9 countries and regions. The top three are Singapore (0.74), Taiwan (0.74), and South Korea (0.69), followed by Japan (0.63), the United Kingdom (0.61), China (0.61), the United States (0.55), the Philippines (0.53), and at the bottom is India (0.47). This ranking does not seem to rely on the respondents' assessment of the level of political democracy in these countries and regions. For example, the UK and China are ranked at the same level of preference. Similarly, Singapore is by no means a model of western liberal democracy. It is only scored 48 out of 100 and received the status of “Partly Free” on the annual global report on political rights and civil liberties by the Freedom House (2021). Yet Singapore is preferred with Taiwan and South Korea, both have higher levels of democracy. The U.S., the Philippines, and India, all with relatively high levels of democracy, are ranked the lowest among the 9 selected countries and regions. What the top three share is the identification with East Asian Confucian tradition.

Figure 2. Respondents' impression of people from nine countries or regions. Hong Kong Political Culture Survey 2021. The chart shows the impression of people from nine countries or regions with the value ranging from 0 to 1, which 1 indicates the best impression, and 0 means the worst. All differences are statistically significant at p < 0.001, except for the differences between impression of the Singaporen and Taiwanese, and between impression of the British and Mainlanders. Figures are rounded off to the nearest hundredths.

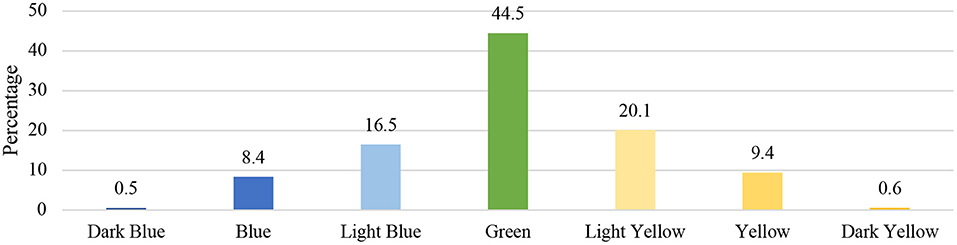

Figure 3 is another bar chart showing political color ranging from the strongest pro-establishment (dark blue) to the strongest anti-establishment (dark yellow) sentiments. The distribution of political colors shows an almost perfect normal curve, and the average value on a 0–1 scale is 0.49, almost right in the middle. For some people, this is somewhat unexpected. For those who have been living in Hong Kong in the past 2 years, it's tempting to conclude that Hong Kong is a highly divided society between the two colors (Beech, 2020). If that is true, the distribution of political colors should be bi-modal around blue and yellow with a few in green (neutral). In a bi-modal distribution of political colors, people's attitudes toward a policy (e.g., NSL), may stay bi-modal by party lines in case they have to take stands, resulting in relative stability and predictability in public opinion. The normal distribution of political color, on the other hand, can create uncertainty and social division if those in the middle have to take stands.

Figure 3. Distribution of respondents by their political leaning. Hong Kong Political Culture Survey 2021. The chart depicts the percentage of respondents by their political leaning that the color blue is used to represent the political leaning of pro-establishment, green neutrality, and yellow anti-establishment. Figures are rounded off to the nearest tenth.

During the anti-China protests in 2019, one would expect that most people would be clustered around yellow with few in green and blue (Gunia, 2019). Alternatively, in the aftermath of the passage of the Hong Kong National Security Law since July 1, 2020, one would expect most people being clustered around blue with relatively few in green and yellow (Wang, 2020). The normal distribution with many people in the middle suggests that most people in Hong Kong society are politically neutral, but they can be pulled into either end depending on which external force is dominant at a given time. Since these people in green do not toe the party line, their political stands may not have consistency, resulting in uncertainty and unpredictability in times of social movements. In sum, it's not how people in Hong Kong are divided by their political colors, and it is the fact that the distribution of their colors is too normal that is unstable.

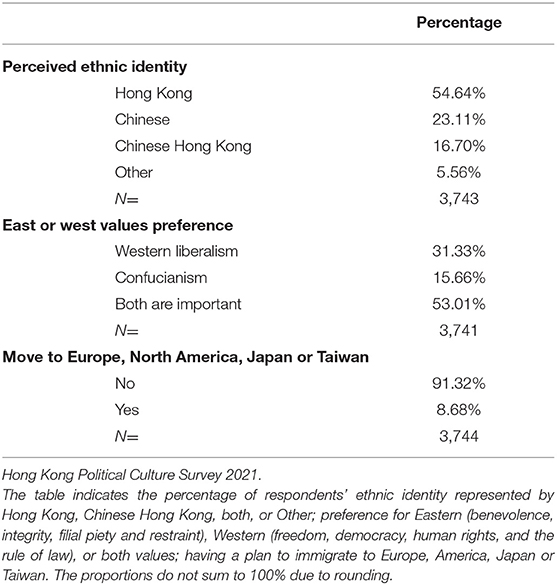

Table 1 includes the remaining three measures of political identity: perceived ethnicity, preference for Eastern and Western values, and intention to immigrate to the West. When asked about their identification with ethnic category, around 55% identified themselves as Hongkongers, 40% as Chinese Hongkongers or Chinese, and 5% as other. Local Hong Kong identity is the strongest, while the percentage of Chinese identity has fluctuated over time according to a local survey (Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, 2021). Even the 40% of Chinese identity is significantly lower than local identity, it is still a sizable group.

For Eastern and Western values, the majority of the survey respondents picked “both are important” (53%), 31% thought Western liberal values are more important, and the remaining 16% identified with Confucian values. Though Western values are more popular than Confucian values, most people are again in the middle, similar to political colors in Figure 3.

The last item in Table 1 is the intention to immigrate to societies that are friendly to Western liberal values, such as Europe, North American, Japan, and Taiwan. Only 9% of the survey respondents expressed their willingness to immigrate to these societies in the next 2 years. This low percentage may be somewhat unexpected since Hong Kong is supposedly in a state of shock by the Hong Kong National Security Law, and many people who were active during the anti-China protests in the past are supposedly feeling scared and unsafe (Needler, 2020; Wazir, 2021).

In summary, the findings in this section show a cold attitude toward the Chinese state among Hong Kong residents. Their view of the Chinese state is significantly less favorable than their view of Chinese culture. Mainland Chinese is generally less preferred than other East Asians, particularly those from Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea. There is no majority in pro-establishment tendence (blue), and the majority don't identify themselves as Chinese.

In the meantime, the sentiment toward the former colonists and their allies is not as high as expected. For example, the UK and the US are not viewed the most favorably; few people are thinking about immigrating to the West; and people's political color is by no means dominated by the pro-yellow, anti-establishment, and pro-democracy group, and only <1/3 support the liberal values at the expense of traditional Confucian values.

Finally, there seems to be a strong preference for traditional Chinese culture and Confucian values. For example, there is a very strong support of traditional Chinese civilization; surprisingly strong preference for people from East Asian societies such as Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea; and around 70% thought that Confucian values as at least just as important as Western liberal values. These findings point to a pattern of indigenization of political identity in postcolonial Hong Kong.

Sources of Political Identity

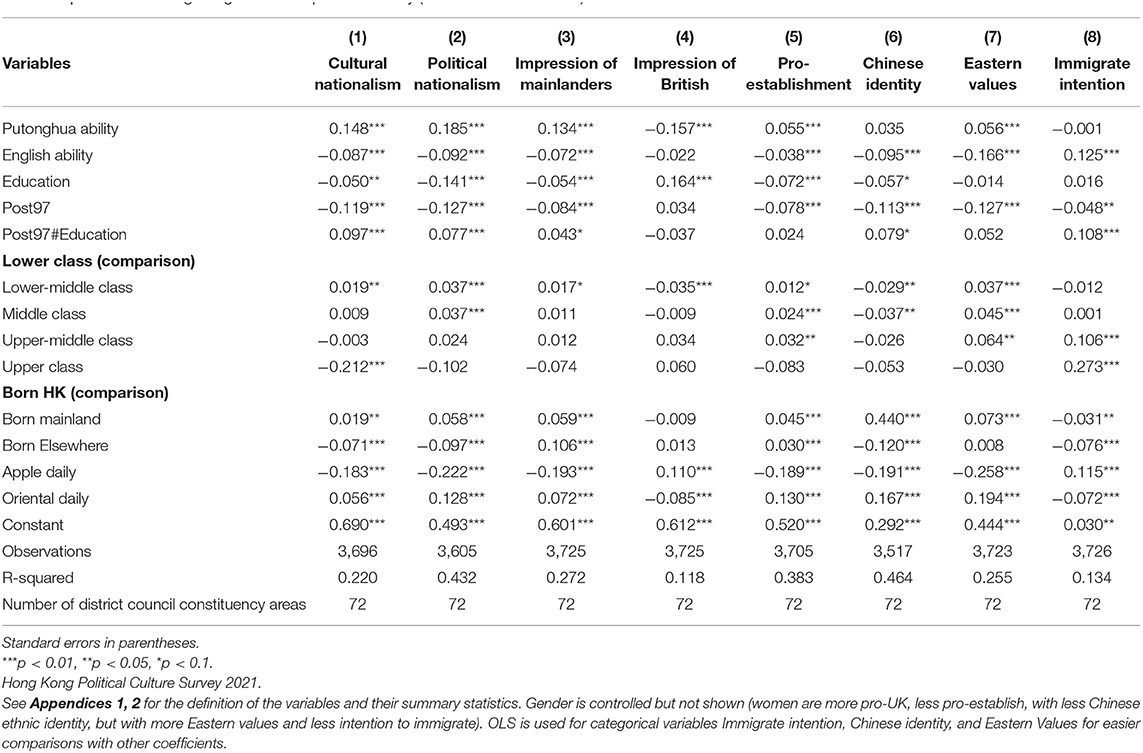

This section analyses the sources of political identity. Specifically, it will examine how the respondents' language ability, education, age, social class, birthplace, and media consumption affect the above measures of political identity. To make the results easier to present, the 6 items in Figure 1 are regrouped into cultural identity and political identity (variables named as Cultural Nationalism and Political Nationalism); only China and the UK are selected for country preferences in Figure 2 (variables named as Impression of Mainlanders and Impression of British), representing old and new rulers; level of Pro-establishment orientation is measured by political color in Figure 3 coded from 0 to 1 scale (variable named as Pro-establishment); Ethnic identity is coded 1 as Chinese, 0.5 as both, and 0 as Hongkonger (variable named as Chinese identity); Preference for Eastern or Western values are coded 1 as Eastern, 0.5 as both and 0 as Western (variable named as Eastern values); Immigration intention is coded 1 and others as 0. Please see Appendices 1, 2 for further details about these variables. To make sure the effects of the above variables are unbiased, the survey respondents' geographic location is controlled by including the 72 electoral districts. The multilevel regression results are presented in Table 2.

In Table 2, Mandarin ability (variable named as Putonghua ability) promotes both Chinese culture and PRC identities (variables named as Cultural Nationalism and Political Nationalism, Impression of Mainlanders, Pro-establishment), but discourages pro-West feelings (variable named as Impression of British). Since all the variables are coded on 0–1 scales (see Appendix 2), except social class and birthplace, the OLS coefficient for each independent variable has a range from −1 to 1, and it can be interpreted as a percentage change. In the case of Mandarin ability, increasing it from minimum (0) to maximum (1) will increase cultural identity by 14.8% and PRC identity by 18.5%. It will improve the image of Mainlanders by about 13.4% but worsen the image of the British by 15.7%. Mandarin ability will also make the respondents about 5.5% bluer or higher orientation to the pro-establishment.

Mandarin education has been one of the controversial policies by the postcolonial Hong Kong government. Before 1997, the British colonists promoted bilingual education of Cantonese and English, while discouraging Mandarin or Putonghua (Wen, 2021). After 1997, trilingual education in schools was first proposed by the then Chief Executive Mr. Tung Chee Hwa in his 1997 Policy Address, aiming at proficient written English and Chinese, and spoken Cantonese, English, and Putonghua for secondary schools' graduates (Tung, 1997) and formulating Putonghua as an elective subject in the Hong Kong Certificate of Education Examinations by year 2000. Putonghua has since 1998 become one of the compulsory subjects at the primary and junior secondary level (CDC, 2017; GHKSAR, 2021), and a non-monetary supporting scheme was launched to make Putonghua a primary medium of instruction for Chinese language courses in 40 schools by the Standing Committee on Language Education and Research between 2008 and 2013 (SCOLAR, 2018).

Such initiative encountered resistance by some local groups (Ng et al., 2017; Wen, 2021). Currently, in Hong Kong's public examination—Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Examination or HKDSE, the core subjects include Chinese, English, Math, Liberal Studies, and Citizenship and Social Development. Putonghua has never been a core subject; students have the option to select Putonghua as a testing language in listening and integrated skill section of their Chinese language examination (HKEAA, 2021a,b). Consequently, Mandarin was only recommended but never required in public exams and teaching medium in the first stage of postcolonial Hong Kong (HKEAA, 2021a,b). This resistance to Mandarin seems to contribute to the overall resistance to Chinese influence in the former colony.

Understandably, English language ability plays the opposite role to Mandarin. Compared with non-English speakers, English speakers identify less with Chinese culture (variable named as Cultural Nationalism) by 8.7%, with Chinese state (variable named as Political Nationalism) by 9.2%, with Mainlanders (variable named as Impression of Mainlanders) by 7.2%, with Pro-establishment orientation (variable named as Pro-establishment) by 3.8%, with Chinese ethnicity (variable named as Chinese identity) by 9.5%, and with Eastern values (Eastern Values) by 16.6%, but are more likely to encourage immigration to the Western-friendly societies (Immigrate intention) by about 12.5%.

Education is another controversial policy in postcolonial Hong Kong. Topics such as the Opium War and Hong Kong's colonial beginning, and the CCP's victory over the Kuomintang (KMT) are resisted by the local teachers' groups from being taught in the common core education (Lam and Zhao, 2017) in postcolonial Hong Kong. Education, moving from the lowest to the highest levels, reduces cultural nationalism, political nationalism, image of Mainlanders, and pro-establishment tendence (blue) by 5%, 14.1%, 5.4%, and 7.2% respectively. In the meantime, it makes the British look better by 16.4%. Some people may think the PRC had intervened enough in Hong Kong's education (Chau, 2020). The findings in this study based on available evidence have shown the opposite effect toward alienation from, but not integration with Mainland China.

Age shows strong and consistent anti-China and pro-West effects. For the age group 39 and younger who completed their political socialization in postcolonial Hong Kong, it is predictably and consistently anti-China, anti-tradition, and pro-West. Comparing with the colonial cohort, the postcolonial cohort is 11.9%, 12.7%, and 8.4% less likely to identify with Chinese culture, the Chinese state, and Impression of Mainlanders. The postcolonial cohort does not show a significant preference for the British, but 7.8% less blue, 11.3% less likely to think they belong to the Chinese ethnicity, and 12.7% less likely to identify with Confucian values. The only exception is immigration intention. The postcolonial cohort is about 4.8% less likely to immigrate to the Western-friendly societies. But as shown below, this immigration effect will change when age is jointly studied with education.

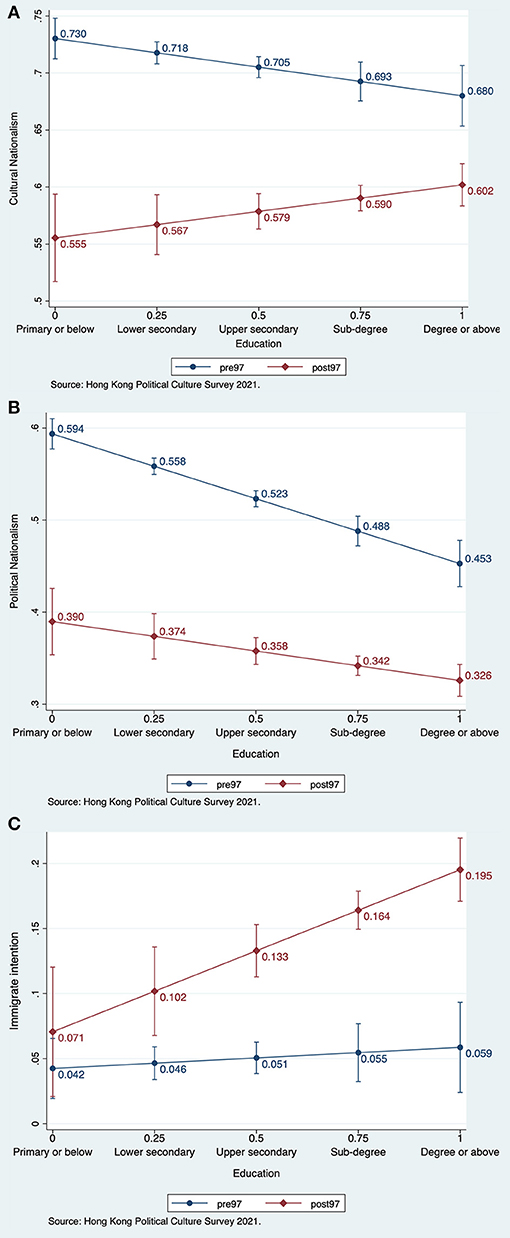

The above discussion treats the effects of education and age separately. Sometimes examining their joint effects may yield clearer patterns of how they interact with each other. The interaction variable of education and age (Post97#Education) shows the joint effects of these two variables on the measures of political identity. It shows that the negative effects of education are significantly stronger for the postcolonial cohort than the pre-1997 cohort in cultural and PRC identities, and for their intention to immigrate.

Figures 4A–C are more intuitive ways to show the interactive effects of education and age cohorts on cultural nationalism (Cultural Nationalism), political nationalism (Political Nationalism), and immigration intention (Immigrate intention). In Figures 4A,B, when education improves from the lowest level (Primary or below) to the highest level (Degree or above), both cultural nationalism and political nationalism decrease by 5% (0.730–0.680 = 0.05 ×100 = 5.0%, Figure 4A) and by 14.1% (0.594–0.453, Figure 4B) for the pre-1997 cohort, suggesting the anti-tradition and anti-PRC effects of education under the British colonial rule. For the post-1997 cohort, education plays the opposite role in promoting cultural nationalism and political nationalism. It promotes cultural nationalism by 4.7% (0.602–0.555, Figure 4A), but suppresses political nationalism by 6.4% (0.39–0.326, Figure 4B). In other words, in post-colonial Hong Kong, education encourages both cultural identity and anti-PRC sentiment. In Figure 4C, education slightly increases the pre-1997 cohort's intention to immigrate to Western friendly societies (0.059–0.042 = 1.7%), but it does so by 12.4% (0.195–0.071, Figure 4C) among the post-1997 cohort. These findings suggest that education experienced a very interesting shift, from suppressing both Chinese tradition and pro-China sentiment under British rule, to promoting Chinese tradition but encouraging anti-China feelings in the post-1997 era. The shifting role of education from anti- to pro-tradition could be a reflection of the education sector's lost colonial mandate and its effort to search for a new focus, while continuing to keep a distance from China. Consequently, education seems to have contributed to the indigenization of the post-Handover generation's political identity.

Figure 4. (A) Effect of education on cultural nationalism by pre- and post-1997 cohorts. (B) Effect of education on political nationalism by pre- and post-1997 cohorts. (C) Effect of education on immigration by pre- and post-1997 cohorts.

Social class also shows an interesting pattern. The top 1% very rich are significantly less pro-Chinese culture. This group is also less pro-PRC, more pro-UK, less blue, with less Chinese ethnic identity, less eastern values but more intention to immigrate than the lower classes. Even some of the regression coefficients are not statistically significant, their values are high enough to notice (model 4, Table 2). The lower middle classes stand out as the least pro-UK among the 5 social classes, perhaps due to the colonial memory of powerlessness. Though the top 5% upper middle class seems to show more pro-establishment sentiment by being more blue or pro-establish, this group is also interestingly more likely to move to the West than the other lower classes. One possibility is that this is their survival strategy. They want to show their support for the regime to protect their vested interest in Hong Kong, while safeguarding themselves by getting ready to leave if things go wrong. This seems to be an opportunistic approach.

Place of birth demonstrates a consistent pattern. Compared with those born in Hong Kong, those born in the Mainland reported stronger sentiments toward Chinese culture, the Chinese state, Mainlanders, blue color, Chinese ethnicity, and Confucian values, and they are less likely to immigrate. These are all expected.

For media consumption, Apple Daily and Oriental Daily News created the opposite results. The former encouraged anti-PRC and anti-Chinese culture feelings consistently across all of the measures. Oriental Daily News, on the other hand, is exactly the opposite. These are again expected, given the political stands of two papers are known. What is interesting, is the different degrees of influence between the two top-circulated newspapers. Apple Daily's negative effects are stronger than Oriental Daily News' positive effects for every single measure of political identity, and Apple Daily's negative effects are the strongest among almost all the independent variables in Table 2. It is understandable why the Hong Kong government recently closed Apple Daily (Chen et al., 2021), given its powerful influence in negatively shaping public opinion in the postcolonial Hong Kong.

To summarize, the above findings show the consequences of stage 1 of Hong Kong's return to China in which China was unable to interfere with Hong Kong's colonial social infrastructure left by the UK, particularly in language policy, education, postcolonial cohort's political socialization, and the media sector.

Robustness Check

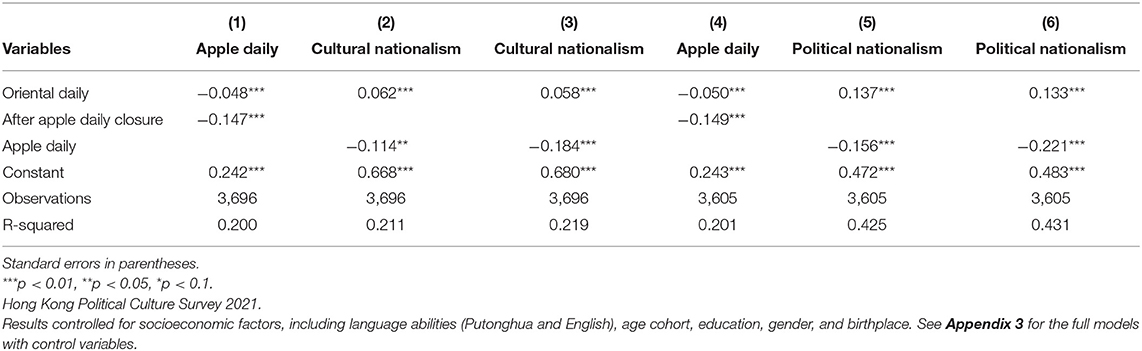

This final section will conduct a further check for the reliability of the media effect in Table 2. Apple Daily, as shown in Table 2, played a strong and negative role in promoting pro-China sentiment in Hong Kong. Is such effect real? Could it be possible that people develop anti-China feelings first, and that makes them read Apple Daily more often? In other words, could the causal direction from Apple Daily to anti-China attitude be in reverse?

How to confirm the causal impact of Apple Daily in anti-China sentiment? One option is to use an instrumental variable (Pokropek, 2016). The instrumental variable (Z) is a variable that is related to X (Apple Daily) but not to Y (anti-China feeling). If X causes Y to change through Z, then the causality from X to Y can be further confirmed. One variable in the survey that can serve as an instrumental variable is the closure of Apple Daily's hardcopy edition on June 24, 2021, halfway through our survey. It is a 0–1 variable (After Apple Daily closure) for before (coded 0) and after (coded 1) the paper's closure. In examining the correlations (not shown), After Apple Daily closure is strongly correlated with the consumption of Apple Daily, but not with the 8 dependent variables in Table 2, thus it is qualified to serve as an instrumental variable.

Table 3 presents the results of the two-stage instrumental variable regression. In the first stage (models 1 and 4), Apple Daily's readership significantly dropped after the closure of its paper edition (After Apple Daily closure). Consequently, its negative effects on cultural nationalism (Cultural Nationalism) and political nationalism (Political Nationalism) are also reduced in models 2 and 5 in Table 3, as compared to Apple Daily's coefficients in models 3 and 6 that are almost the same as in Table 2 without the effects of the instrumental variable. This causal chain from the instrumental variable to X then to Y suggests that Apple Daily does seem to have a causal effect on the anti-China sentiment.

Conclusions

In the beginning section, this paper describes the various theories of postcolonial identity, ranging from continued colonial legacy to a new decolonized identity, as well as the constructivist view of the interaction between the old and the new in identity formation. In Hong Kong's unique postcolonial political vacuum, this study suggests that political identity is formed neither by the colonial legacy nor by the new ruler's ideology. Instead, Hongkongers are going back to their cultural roots and converting such cultural identity into a political one.

The empirical evidence presented in this study supports the hypotheses developed earlier. It shows an overall cold feeling toward the Chinese state and Mainland Chinese people (hypothesis 1). The findings also present an indifferent feeling toward the West and the territory's former colonial rulers (hypothesis 2). In this vacuum left by the old and new rulers, Hong Kong residents are looking for restoring traditional culture for their political identity in a process that can be described as indigenization (hypothesis 3). China's reluctant laissez-faire policies further encouraged the trend of indigenization (hypothesis 4).

Hong Kong's experience with indigenization of political identity suggests that the One Country Two System policy will not work well if there is no unified political identity in the “One Country” part of the institutional design. It's easy to talk about it as a clever institutional design; the implementation of “one country” runs into problems in many branches of Hong Kong society, education, legal system, media, and even the official language policy, resulting in the failure of pro-China identity. The Hong Kong National Security Law of 2020 requires mandatory political identity and loyalty. In another 20 years, it will be time to re-examine political identity in phase 2 of postcolonial Hong Kong.

Finally, this study contributes to the existing studies on “local identity” (Fung, 2001; Veg, 2017; Steinhardt et al., 2018). It further clarifies the meaning of local identity by separating traditional cultural identity from colonial identity and Chinese state identity. It shows how people can fall back to their cultural identity in a political vacuum under One Country Two Systems. In this political vacuum, political anxiety was created by the departure of the colonists and the inability of China as the territory's new ruler to establish its own effective governance. To cope with this political anxiety, indigenization of political identity emerged. To what extend this trend will continue depends on how quickly China can establish its own political reputation among the territory's residents.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available with the approval by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Stuart Gietel-Basten, the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Written informed consent from the participants' legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

WT contributed to the conceptions, design of this study, and wrote the first draft of this paper. JH facilitated the data collection and wrote sections of the manuscript. BH performed the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to data analysis, manuscript revision, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project was supported by a General Research Fund (RGC Ref No. 16601820) and the Anti-Epidemic Fund 2.0, awarded by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.837992/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^If we also include free newspapers, the freely distributed Headline is the most popular (33%), followed by the second most popular Oriental Daily News (22%, paid), and the third most popular Apple Daily at 19% (paid).

References

Ashcroft, B., Griffiths, G., and Tiffin, H. (1995). The Post-Colonial Studies Reader. London: Routledge.

Bahri, D. (2003). Native Intelligence: Aesthetics, Politics, and Postcolonial Literature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bammer, A. (1994). Displacements: Cultural Identities in Question. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Beech, H. (2020). Yellow or Blue? In Hong Kong, Businesses Choose Political Sides. New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/19/world/asia/hong-kong-protests-yellow-blue.html (accessed November 25, 2021).

Bressler, C. E. (2007). Literary Criticism: An Introduction to Theory and Practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Brysk, A., Parsons, C., and Sandholtz, W. (2002). After empire: national identity and post-colonial families of nations. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 8, 267–305. doi: 10.1177/1354066102008002004

Carroll, J. M. (2005). Edge of Empires Chinese Elites and British Colonials in Hong Kong. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

CDC (2017). 中文教育域:普通科程指引(小一至中三)(2017) [Chinese Language Education Key Learning Area: Putonghua Curriculum Guide (Primary One to Secondary Three) (2017)]. Curriculum Development Council. Available online at: https://www.edb.gov.hk/attachment/tc/curriculum-development/kla/chi-edu/curriculum-documents/PTH_Curriculum_guide_for_upload_final.pdf/ (accessed November 25, 2021).

Chan, H. M. (1994). “Culture and identity,” in The Other Hong Kong Report 1994, eds D. H. Mcmillen and S. W. Man (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press), 443–468.

Chan, S. C. (1998). Politicizing tradition: the identity of indigenous inhabitants in Hong Kong. Ethnology 37, 39–54. doi: 10.2307/3773847

Chatterjee, P. (2004). The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Chau, C. (2020). Hong Kong liberal studies to be renamed and reformed - more China content, less focus on current affairs. Hong Kong Free Press. Available online at: https://hongkongfp.com/2020/11/27/hong-kong-liberal-studies-to-be-renamed-and-reformed-more-china-content-less-focus-on-current-affairs/ (accessed November 25, 2021).

Chen, Q. Q., Cui, F. D., and Leng, S. M. (2021). Largest HK opposition group likely to disband; city no longer secessionism hotbed. Global Times. Available online at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202108/1231368.shtml (accessed November 25, 2021).

Cheung, G. K. W. (2012). 六七暴:香港後史的分水 [Hong Kong's watershed : the 1967 riots]. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Choi, P. K. (1990). “Popular culture,” in The Other Hong Kong report: 1990, ed by R. Y. C. Wong and J. Y. S. Cheng (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press), 443–468.

Dizayi, S. A. H. (2019). Locating identity crisis in postcolonial theory: fanon and said. J. Adv. Res. Soc. Sci. 2, 79–86. doi: 10.33422/JARSS.2019.05.06

Elam, J. D. (2019). Postcolonial Theory. Oxford Bibliographies in Literary and Critical Theory. Available online at: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780190221911/obo-9780190221911-0069.xml (accessed November 25, 2021).

FCCHK (2017). Fifty Years on: The Riots That Shook Hong Kong in 1967. Foreign Correspondents' Club Hong Kong. Available online at: https://www.fcchk.org/correspondent/fifty-years-on-the-riots-that-shook-hong-kong-in-1967/ (accessed November 25, 2021).

Freedom House (2021). Freedom in the World 2021: Democracy Under Siege. New York, NY: Freedom House. Available online at: https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/FIW2021_World_02252021_FINAL-web-upload.pdf (accessed November 25, 2021).

Fung, A. (2001). What makes the local? A brief consideration of the rejuvenation of Hong Kong identity. Cult. Stud. 15, 501–560. doi: 10.1080/095023800110046713

GHKSAR (2021). Press Releases: LCQ16: Public's Putonghua Standard. The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Available online at: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202108/18/P2021081800330.htm (accessed November 25, 2021).

Guha, R. (1982). “On Some Aspects of the Historiography of Colonial India,” in Subaltern Studies: Writings on South Asian History and Society, ed R. Guha (New Delhi; New York: Oxford University Press), 1–8.

Gunia, A. (2019). Hong Kong's Democracy Parties Scored Big in Local Elections. Here's What That Means for Their Movement. Time. Available online at: https://time.com/5736896/hong-kong-district-council-elections/ (accessed November 26, 2021).

Hall, S. (1990). “Cultural identity and diaspora,” in Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, ed J. Rutherford (London: Lawrence & Wishart), 222–237.

Han, E. (2016). Contestation and Adaptation: The Politics of National Identity in China. New York: Oxford University Press.

Han, E. (2019). Asymmetrical Neighbors: Borderland State Building between China and Southeast Asia. New York: Oxford University Press.

HKEAA (2021a). Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Examination 2022: Registration for Category A and Category B subjects Instructions to Applicants (School Candidates). Hong Kong: Hong Kong Examinations and Assessment Authority (HKEAA). Available online at: https://www.hkeaa.edu.hk/DocLibrary/HKDSE/Exam_Registration/Instructions_to_Applicants_SepReg_2022_SchoolCand_Eng.pdf (accessed November 26, 2021).

HKEAA (2021b). Hong Kong: HKEAA (Hong Kong Examinations and Assessment Authority). Available online at: https://www.hkeaa.edu.hk/en/hkdse/assessment/subject_information/ (accessed November 26, 2021).

Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute (2021). Categorical Ethnic Identity. Available online at: https://www.pori.hk/pop-poll/ethnic-identity-en/q001.html?lang=en (accessed December 14, 2021).

Kaphle, A. (2013). Chinese tourists' bad manners harming country's reputation, says senior official. Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2013/05/17/chinese-vice-premier-says-chinese-tourists-bad-manners-is-harming-china/ (accessed November 26, 2021).

King, A. Y. (1975). Administrative absorption of politics in Hong Kong: emphasis on the grass roots level. Asian Survey 15, 422–439. doi: 10.1525/as.1975.15.5.01p0076b

Ku, A. S. (2004). Immigration policies, discourses, and the politics of local belonging in Hong Kong (1950-1980). Modern China 30, 326–360. doi: 10.1177/0097700404264506

Kuan, H. C., and Lau, S. K. (1989). “The civic self in a changing polity: the case of Hong Kong,” in Hong Kong: The Challenge of Transformation, eds M. Mushkat and K. Cheek-Milby (Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong), 91–115.

Lam, J., and Zhao, S. (2017). Who's afraid of Chinese history lessons? South China Morning Post. Available online at: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/education/article/2117899/explain-why-do-chinese-history-lessons-get-bad-reputation (accessed November 26, 2021).

Lam, W. M. (2004). Understanding the Political Culture of Hong Kong: The Paradox of Activism and Depoliticization. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

Lam, W. M. (2018). “Hong Kong's fragmented soul: exploring brands of localism,” in Citizenship, Identity and Social Movements in the New Hong Kong Localism after the Umbrella Movement, eds W. M. Lam and L. Cooper (London: Routledge), 72–93.

Lau, S. K. (1992). Indicators of Social Development: Hong Kong, 1990. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Lau, S. K. (1997). “Hong Konger” or “Chinese”: the identity of Hong Kong Chinese 1985-1995. Twenty First Century 41, 43–58.

Lau, S. K. (2017). 香港人的政治心[The Political Mentality of Hong Kong People]. Hong Kong: The Commercial Press (Hong Kong) Limited.

Lau, S. K., and Kuan, H. C. (1988). The Ethos of the Hong Kong Chinese. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press.

Law, W. S. (2015). “告七一嘉年: 自由主到公民共和的後殖主性”[Farewell to the July 1st Carnival: From the Virtual Liberalism to the Postcolonial Subjectivity of the Citizen Republic], in Journal of Local Discourse 2013-2014: The China Factor, ed Editorial Committee of the Journal of Local Discourse and SynergyNet (Taipei: Azoth Books Company Limited), 3–19.

Law, W. S. (2018). “Decolonisation deferred: Hong Kong identity in historical perspective,” in Citizenship, identity and social movements in the new Hong Kong: localism after the Umbrella Movement, eds W. Lam and L. Cooper (London: Routledge), 13–33.

Lee, J. (2021). Official unmasking of the HK Professional Teachers' Union. Chinadailyhk. Available online at: https://www.chinadailyhk.com/article/231559#Official-unmasking-of-the-HK-Professional-Teachers (accessed November 26, 2021).

Leung, S. W. (1997). “Social construction of hong kong identity: a partial account,” in In Indicators of Social Development: Hong Kong 1997, eds S. K. Lau, M. K. Lee, P. S. Wan, and S. L. Wong (Hong Kong: Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, The Chinese University of Hong Kong), 111–134.

Li, A. (2013). Why Are Chinese Tourists so Rude? A Few Insights. South China Morning Post. Available online at: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1251239/why-are-chinese-tourists-so-rude (accessed November 26, 2021).

Li, A. (2014). Rude awakening: Chinese tourists have the money, but not the manners. South China Morning Post. Available online at: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1671504/rude-awakening-chinese-tourists-have-means-not-manners#_ (accessed November 26, 2021).

Ma, E. K., and Fung, A. Y. (2007). Negotiating local and national identifications: Hong Kong identity surveys 1996–2006. Asian J. Commun. 17, 172–185. doi: 10.1080/01292980701306555

Ma, N. (2018). “Changing identity politics: the democracy movement in Hong Kong,” in Citizenship, Identity and Social Movements in the New Hong Kong: Localism After the Umbrella Movement, ed W. M. Lam (London: Routledge), 34–50.

Maizland, L., and Albert, E. (2021). Hong Kong's Freedoms: What China Promised and How It's Cracking Down. Council on Foreign Relations. Available online at: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/hong-kong-freedoms-democracy-protests-china-crackdown (accessed November 26, 2021).

Mathews, G., Ma, E. K. W., and Lui, T. L. (2008). Hong Kong, China: Learning to Belong to a Nation. London: Routledge.

Needler, C. (2020). Scared silent: Hong Kong national security law forces Penn students to rethink future plans. The Daily Pennsylvanian. Available online at: https://www.thedp.com/article/2020/07/hong-kong-students-penn-protest-national-security-law (accessed November 26, 2021).

Ng, A., Yi, Y., and Lee, G. (2017). Cantonese, Putonghua or English? The language politics of Hong Kong's school system. Hong Kong Free Press. Available online at: https://hongkongfp.com/2017/04/09/cantonese-putonghua-english-language-politics-hong-kongs-school-system/ (accessed November 26, 2021).

Paolini, A. J., Elliott, A., and Moran, A. (1999). Navigating Modernity: Postcolonialism, Identity, and International Relations. Boulder, CO: L. Rienner Publishers.

Pokropek, A. (2016). Introduction to instrumental variables and their application to large-scale assessment data. Large Scale Assess. Educ. 4, 1–20. doi: 10.1186/s40536-016-0018-2

Ramanathan, V. (2005). The English-Vernacular Divide: Postcolonial Language Politics and Practice. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Richards, D. (2010). “Framing identities,” in A Concise Companion to Postcolonial Literature, eds S. Chew and D. Richards (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell), 9–28.

Rukundwa, L. S., and Aarde, A. V. (2007). The formation of postcolonial theory. Theol. Stud. 63, 1171–1194. doi: 10.4102/hts.v63i3.237

SCOLAR (2018). Scheme to Support Schools in Using Putonghua to Teach Chinese Language Subject. Standing Committee on Language Education and Research. Standing Committee on Language Education and Research. Available online at: https://scolarhk.edb.hkedcity.net/en/project/2008/scheme-support-schools-using-putonghua-teach-chinese-language-subject?menu=main-menu&mlid=752 (accessed November 26, 2021).

Smith, A. D. (1998). Nationalism and Modernism: A Critical Survey of Recent Theories of Nations and Nationalism. London; New York: Routledge.

So, A. Y. (1999). Hong Kong's Embattled Democracy: A Societal Analysis. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

So, A. Y. (2005). “香港人身份的形成” [The Formation and Transformation of HongKonger's Identity], in 文化,族群社的反思 [Reflections on culture, ethnic group and society] (Kaohsiung City: Liwen Publishing Group), 175–188.

So, A. Y. (2015). “The making of Hong Kong nationalism,” in Asian Nationalisms Reconsidered, ed J. Kingston (New York, NY: Routledge), 195–199.

Spivak, G. C. (1988). “Can the subaltern speak?” in Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader, ed P. Williams (Harlow: Pearson Education), 271–313.

Steinhardt, H. C., Li, L. C., and Jiang, Y. (2018). The identity shift in Hong Kong since 1997: measurement and explanation. J. Contemp. China 27, 261–276. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2018.1389030

Tang, W. F., and Parish, W. L. (2000). Chinese Urban Life Under Reform: the Changing Social Contract. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tung, C. H. (1997). Chief Executive's Policy Address: Building Hong Kong for a New Era. GHKSAR (The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region). Available online at: https://www.policyaddress.gov.hk/pa97/english/patext.htm (accessed November 26, 2021).

Veg, S. (2017). The rise of localism and civic identity in post-handover Hong Kong: questioning the Chinese nation-state. China Q. 230, 323–347. doi: 10.1017/S0305741017000571

Wang, Q. (2020). Increasing number of HK residents support national security law: poll. Global Times. Available online at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1194087.shtml (accessed November 26, 2021).

Wazir, Z. (2021). Activists, Families and Young People Flee Hong Kong. U.S. News. Available online at: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2021-09-16/activists-families-and-young-people-flee-hong-kong (accessed November 26, 2021).

Webster, D. (2021). Meng for the two Michaels: Lessons for the world from the China-Canada prisoner swap. The Conversation. Available online at: https://theconversation.com/meng-for-the-two-michaels-lessons-for-the-world-from-the-china-canada-prisoner-swap-168737 (accessed September 29, 2021).

Wen, T. M. (2021). “快立普通法定言地位” [Establishing the legal status of Mandarin as soon as possible]. Ta Kung Pao. Available online at: http://www.takungpao.com/opinion/233119/2021/0925/636036.html (accessed November 26, 2021).

Wong, T. K. Y. (1997). 公民意民族同: 後渡期香港人的 [Civic Awareness and National Identity: The Experience of the Hong Kong People during the Late-transitional Period]. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Xiao, G. J. (1997). 香港的史文物 [Hong Kong History and Heritage]. Hong Kong: Ming Pao Publications Limited.

Yan, X. J. (2015). 香港治: 2047的政治想像 [Hong Kong order and disorder: political imagination of 2047]. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing Company Limited.

Yu, J. M. (2014). Hong Kong Newspapers, Pro- and Anti-Beijing, Weigh In on Protests. Sinosphere Blog. Available online at: https://sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/10/06/hong-kong-newspapers-pro-and-anti-beijing-weigh-in-on-protests/ (accessed November 26, 2021).

Zheng, V. W.T., and Wong, S. L. (2002). “香港人的身份同:九七前後的” [The Identity of Hong Kong Chinese: Before and After 1997]. Twenty-First Century 73, 71–80. Available online at: https://www.cuhk.edu.hk/ics/21c/media/articles/c073-200207038.pdf

Keywords: ethnic identity, nationalism, postcolonialism, indigenization, Hong Kong

Citation: Tang W, Hung JSY and Ho BYY (2022) Indigenization of Political Identity in Postcolonial Hong Kong. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:837992. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.837992

Received: 17 December 2021; Accepted: 13 May 2022;

Published: 15 July 2022.

Edited by:

Premysl Rosulek, University of West Bohemia, CzechiaReviewed by:

Gigi Lam, Hong Kong Shue Yan University, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaFen Lin, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Copyright © 2022 Tang, Hung and Ho. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jennifer Sin Yu Hung, c3lodW5nYWJAY29ubmVjdC51c3QuaGs=; Brian Ying Yeung Ho, YnJpYW55eWhvQHVzdC5oaw==

Wenfang Tang

Wenfang Tang Jennifer Sin Yu Hung

Jennifer Sin Yu Hung Brian Ying Yeung Ho

Brian Ying Yeung Ho