- 1School of Psychology, Keele University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

- 2Institute of Psychology, Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Jena, Germany

- 3Faculty of Science, School of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, United Kingdom

People around the globe are affected by disasters far beyond the disaster properties. Given that certain social groups are affected disproportionately, disasters need to be considered as political events which may cause political actions. Therefore, we aim to discuss, from a social psychological perspective, how and why protests might occur during or after a disaster. We argue for an elaborated model of collective action participation suggesting that disasters enhance the predictors of protest mobilization and participation though emerged or enhanced social injustice. We also suggest that disaster properties can be used to delegitimise protests and social movements, limiting the mobilization and collective resilience during and after a disaster. Finally, we discuss the gaps in current research and emphasize the need for more attention to the disaster-protest link as we can expect more disasters due to climate crisis, likely to lead to more protests and political collective action.

Introduction

“Is this a fate? Are these earthquakes, these landslides fate? There is an earthquake in another country with the same magnitude, 2 people faint, but here, 20 thousand people died, is this a fate? Every year, people and animals die here from landslides, is it a fate? No! This is the result of various policies that you have made with malice or incompetence. To protest all this, one must neither be a prophet, nor a philosopher, nor an artist.” (Kazim Koyuncu)1

A disaster is an occurrence or event that seriously disrupts a community in its functioning and normal existence, creating a context where the community resources to cope are insufficient (World Health Organization (WHO), 2002; International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), 2022). According to the World Health Organization (WHO) (2002) and International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) (2022) a disaster is comprised by two components; hazard and vulnerability. A hazard can be either natural (e.g., a storm or drought) or man-made (e.g., environmental pollution or structural collapse) (World Health Organization (WHO), 2002; International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), 2022). However, a hazard alone does not trigger a disaster, for an occurrence or event to be classed as a disaster it needs to have vulnerability present (e.g., poverty, limited access to power systems, lack of local investment, fragile local economy) predisposing suffering of the hazard's damage (World Health Organization (WHO), 2002). Hence, we need to address the function of social inequalities and injustices when discussing disasters. We argue that disasters should be discussed as political events rather than natural phenomena to account for the effect it has on populations, as people who have less financial, social and psychological resources are affected unequally compared to people with resources.

Previous research indicates predictors for political or violent unrest in the aftermath of disasters in relation to human threat, and social and societal mechanisms (in addition to physical and material conditions) (e.g., Nardulli et al., 2015). For example, population characteristics such as size and density of population potentially leading to larger loss of lives, assets etcetera (Ide et al., 2021). Large population areas are more likely to be heterogeneous, which increases the likelihood of some people being in opposition to the state as well as having time to protest. However, most predictors of political or violent unrest after disasters are linked to social and economic inequality. For example, an area's economic development (GDP) affects whether people have the privilege to move to less disaster-prone areas, as well as their ability to prepare for disasters (Nel and Righarts, 2008). Furthermore, restrictions in mobility and preparation (Ide et al., 2021) as well as food and water insecurity (Koren et al., 2021) can lead to collective frustration which in turn elicits political unrest. The societal inequality and exclusion can also prevent certain groups being included in the political power (ethnopolitical exclusion). Finally, a country's state system or leadership can trigger protests both during and after a disaster. Due to systemic injustices, even countries with democratic systems (with low repressive consequences) or countries that are considered rich, can experience unrest in relation to disasters (Tierney et al., 2006; Solnit, 2009; Ide et al., 2021). The unrest is likely to emerge from the authorities' lack of consideration of different groups' different levels of needs and varied disaster support for survival before, during, and after a disaster. The response of the state has a large impact on whether conflict arises, regardless of whether there are other factors present that influences the public to challenge authority (Nel and Righarts, 2008). Taken together, societal factors outweigh the disaster properties in relation to risk of unrest in the aftermath of disasters. Even though not all disasters turn into protests, disasters can be the macro-context for ongoing or emergent protests, due to long-lasting impacts of disasters. For instance, analyzing Black Lives Matter protests after the murder of George Floyd without considering and contextualizing the psycho-social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic will likely result in a reductionist account of events.

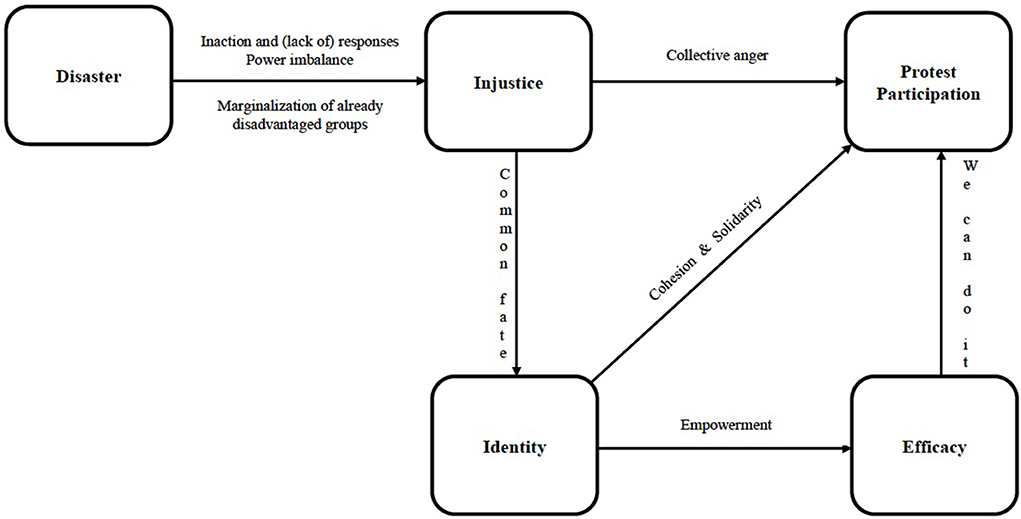

The current paper aims to i) extend social psychological understanding of collective action (e.g., Drury and Reicher, 2000; van Zomeren et al., 2008) in disaster contexts (see Figure 1); and ii) suggest how misuse of disaster properties can be used against the collective, delegitimizing the cause, action and movement, potentially hindering community recovery and resilience in disasters. The COVID-19 pandemic will be used to contextualize these aims, as well as discussed in relation to previous disasters and protests. Understanding the social psychological relationship between disasters and protests is of importance as we can expect an increase in both numbers and severity of climate change related disasters world-wide (e.g., Van Aalst, 2006; Benevolenza and DeRigne, 2019), likely to trigger local and global protests both during and after disasters.

Social psychological research on disasters and collective action: Toward an elaborated model of collective action and disasters

Social psychological research emphasizes that in disasters people are more likely to engage in collective action and cooperative behaviors than panic and engage in selfish behaviors (e.g., Grimm et al., 2014; Drury, 2018). Similar patterns have been observed during the COVID-19 pandemic, where people join mutual aid groups to help their communities with for example dog-walking, shopping, and other things to facilitate reduction in virus transmission (see Fernandes-Jesus et al., 2021; Mao et al., 2021). Research on collective action in the form of cooperation and mutual aid during and after disasters demonstrates that in disasters a shared fate often develops which facilitates a shared identity to emerge (e.g., Cocking et al., 2009; Drury et al., 2009). Through shared fate, people come to see themselves as part of the same group or community, which functions as a base for solidarity, cohesion, and empowerment to emerge (Drury and Reicher, 1999, 2009). The process of collective empowerment can further be achieved with strategic steps, such as reaching out to wider groups of supporters who are not directly affected by the disaster (Tekin and Drury, 2020), hence mobilizing solidarity and support for collective action further. It is not uncommon that collective action, in the form of cooperation, emerges during and after disasters (e.g., Aldrich, 2013; Drury et al., 2016; Alfadhli and Drury, 2018; Ntontis et al., 2018, 2020). However, people do not only act in solidarity in the form of mutual aid, they also take action together to achieve social change through protests. For example, in June 2017 a fire broke out in the Grenfell Tower block in West London, UK. Along with building a community and support, campaigners started protest campaigns to challenge negative stereotypes and injustice through government inaction (Tekin and Drury, 2020, 2021a). The Grenfell community campaigners self-organized and engaged in non-violent protest activities such as petitions and silent walks to seek justice.

Protests during or in the aftermath of disasters are often linked to emergent or increased social injustice as a result of the disaster. The COVID-19 pandemic has, like other disasters, disproportionately affected already marginalized communities (see Templeton et al., 2020). Using data from “The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED)” which tracks demonstrations and political violence globally, Kishi et al. (2021) demonstrated that at the beginning of the pandemic, a decrease in protests could be observed around the world. However, during 2020 the total number of protests increased by 3% compared to 2019 (Kishi et al., 2021). Furthermore, compared to 2019, 2020 saw an increase in peaceful protests, and a decrease in the number of protests met with authority intervention as well as a decrease in the number of fatalities related to protests (Kishi et al., 2021). Social psychological models identify three key psychological antecedents for participating in protests. First, a sense of shared identity (see Tajfel and Turner, 1979), an identification with a relevant group (e.g., Drury and Reicher, 2000; van Zomeren et al., 2008). The shared identification could for example be as a minority community member, a woman, a union member, or an environmentalist. Second, perceived collective injustice, illegitimacy and collective anger as a result of inequalities (e.g., Runciman, 1966; Walker and Smith, 2002; Drury and Reicher, 2005; van Zomeren et al., 2008; Becker et al., 2011). The perceived collective injustice can be in relation to one's own group, or in solidarity with another group (e.g., Subašić et al., 2008). Last, collective efficacy beliefs, a sense of control, agency, strength, and collective effectiveness to challenge the existing power relations predict participation in collective action (e.g., Klandermans, 1984; van Zomeren et al., 2004; Blackwood and Louis, 2012). Even though most models of collective action participation contain the three key variables identification, injustice, and efficacy, they differ in whether they treat identity as a predictor (e.g., SIMCA see van Zomeren et al., 2008, or SIRDE see Grant et al., 2015) or as an outcome (e.g., EMSICA see Thomas et al., 2012, or the Normative Alignment Model see Thomas et al., 2009).

We argue that disasters can offset or increase already existing perceived group-based injustice (e.g., Templeton et al., 2020), create a shared social identity (e.g., Cocking et al., 2009; Drury et al., 2009), as well create or increase perceived collective efficacy (e.g., Drury et al., 2016) through a perception that “we” can be effectful in toppling the power or changing power relations (e.g., changing policy around cladding, increasing transparency in state communication, or shifting the political governance). Increased identification from shared injustice has been emphasized elsewhere both broadly in terms of sharing minority membership or victimhood (see e.g., rejection-identification model by Branscombe et al., 1999) as well as in the disaster literature in terms of common fate (e.g., Drury et al., 2009). Shared injustice can emerge from interaction with others in the same context leading to a shared perception of grievance or injustice resulting in the emergence of a shared identity (e.g., Thomas et al., 2012). As outlined in Figure 1, we suggest that a disaster context can enhance the antecedents for collective action and consequently increase the chances of protests occurring.

Most protests aim to fight perceived societal injustice or inequality, seeking justice or truth. Similarly, most disasters (see examples below) contain societal injustice and inequality in terms of lack of preparation, support, and management in the response and after phase. We argue that the disaster context creates conditions where the collective action predictors are enhanced through exposed, emerged, or increased perceived injustice. To illustrate the relationship between disasters and protests, and the core function of social injustice and/or power imbalance (right to control the narrative) we will discuss a few disasters that have been followed by protests.

Disasters followed by protests—Demonstrating the link through enhanced perceived injustice

After the Hurricane Katrina disaster, in and around the city of New Orleans in the US, in August 2005, several grassroot movements and social movements emerged along with mobilization for existing movements. These movements were mainly focusing on creating a community, while emphasizing inequalities, injustice and restrictions to human rights (Luft, 2009). The relation between systemic injustice and disaster was particularly evident as poorer areas, with a majority Black population, were affected more during the disaster than richer (Whiter) areas. Additionally, while people with more financial funds could both prepare for and acquire disaster support, the authorities responded very late with disaster support and relief to the poorer areas. The late response led to people having to find resources and materials to survive where available, for example from shops, which in turn led to them being described as looters and criminals by some media outlets (Tierney et al., 2006; Solnit, 2009). For at least 2 years after Hurricane Katrina there were protests, against social injustice, on Gretna Bridge—where the police stopped people from evacuating the disaster area (Heldman, 2010). Furthermore, The People's Hurricane Relief Fund organized a demonstration in December 2005 with a focus on human rights and the right to return (Luft, 2009). Even though the area was marginalized before the hurricane, it can be suggested that the disaster enhanced the perceived injustice as well as social identification predicting subsequent protest participation.

Compared to the rapid onset of hurricane Katrina, the Bangkok floods of 2011 in Thailand was a slow onset disaster - the government had a period of about 3 months for disaster management and preparation (Marks et al., 2020). The government decided to protect the inner city by building floodwalls, resulting in outer areas of the city being worse off than if the water had been allowed to flow freely (Marks et al., 2020). In the case of the Bangkok floods, there was, as with Hurricane Katrina, a clear difference in the government's treatment of the rich (inner city) and poor (outer city) areas, demonstrating flood injustice and societal inequality. Based on the social injustice, non-violent protests emerged from about 20 communities outside the floodwall (Marks et al., 2020). Hence, the disaster, through government action and social injustice, created a context where the collective action predictors could flourish, and protesters demanded that the government should see and treat them as citizens of Bangkok as well as question the right of defining justice.

In addition to social injustice in terms of resources, there are also protests linked to the power imbalance in terms of who controls the information and narrative which in turn can create conditions for emergence or enhancing of the collective action predictors of perceived injustice, social identity, and collective efficacy. For example, after the horrific events at the Hillsborough stadium where 96 people lost their lives the victims' families were campaigning to seek truth and justice for the victims (Cronin, 2017). For 27 years the fans were blamed for causing the crush, before it was acknowledged that the police had lied and kept pushing the lie. Similarly, on the 11th March 2004, four bombs went off on trains in Madrid, killing 192 people and leaving many others injured (Flesher Fominaya, 2011). After the disaster, the government was quick to blame ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna) even though there was information pointing elsewhere. The government lies and coverup were perceived to be in relation to the upcoming political election due 3 days later, demonstrating the power imbalance and right to control the narrative. The day before the election, protests and flash mobs called M-13 occurred. These protests were mainly fuelled by the perception that the government, still blaming ETA, was withholding the truth about the bombings, and were involved in a media blackout (Flesher Fominaya, 2011). Activists protested in front of the ruling party's headquarter in Madrid, and quickly grew to become 3,000–5,000 in the crowd. Later that night, protests emerged in other cities across Spain. In both Hillsborough and the Madrid bombing, it can be argued that the government and authorities created a power imbalance by controlling the narrative, which in turn elicited a sense of shared collective injustice, solidarity and cohesion, anger, and empowerment.

In 2011 an earthquake-triggered tsunami caused a shut-down of the cooling systems at Fukushima nuclear plants in Japan, causing a meltdown in three of the plant's six reactors. The tsunami killed 20 000 people (Ikegami, 2012) and devastated coastal towns, shut down business and communication (Funabashi and Kitazawa, 2012). On the backend of this, the Fukushima meltdown caused more than 300 000 people to be evacuated, and many of them faced not being able to return home for a very long time (Aldrich, 2013). There was already an existing anti-nuclear movement in Japan, however, the disaster prompted more people to question the lack of peoples' influence on policy. Hence, the disaster mobilized further support for the anti-nuclear movement while also creating an emerging movement where citizens started measuring the radiation on their own devices as well as organizing marches and protests outside the PM's home and the national parliament (Ikegami, 2012; Aldrich, 2013). The mobilization of the anti-nuclear movement and people's science movement stemmed from discontent with the government's handling of the disaster, lack of transparency, misinformation and suppression of both information and data (Ikegami, 2012; Aldrich, 2013). Once again it was not the disaster itself that caused the protests but rather the government's handling of the disaster along with spreading lies and misinformation that created conditions for protests and collective action to emerge.

The events described above have in common the features of social injustice and inequality, and state inaction and mistrust (power imbalance). They have a narrative of group-based injustice, distinct outgroups (indicating shared identity) as well as shared social group membership as victims or survivors. Hence, it is not the disaster itself that mobilizes various protest movements—it is the lack of preparation, response and management from the authorities and other state actors that provide a platform for the three key predictors (shared identity, group-based injustice, collective efficacy) of collective action to emerge or accelerate. Thus, we suggest that during and post-disaster protests share similar patterns with non-disaster protests in terms of social-psychological predictors. However, disasters are likely to accelerate and amplify those predictors (identity, injustice, and efficacy) through state inaction and unjust interventions. In the next section we will discuss how protests can be understood in the context of the global pandemic COVID-19 using the proposed model of disasters and collective action (see Figure 1).

Protests and social injustice during the COVID-19 pandemic: “We are not in the same boat!”

It is expected that people will take collective action and participate in protests for causes that resonate with their values and worldview during the COVID-19 as in other times. However, compared to non-pandemic times, with the COVID-19 global lockdowns and stay at home restrictions people had more time to spend on social media (e.g., Grant and Smith, 2021). The increased time on social media increased the exposure to messages highlighting social inequalities (Ramsden, 2020; Grant and Smith, 2021). The exposure to social inequalities via social media during the pandemic might increase people's sense of perceived injustice and illegitimacy, in turn, collective anger (e.g., Wlodarczyk et al., 2017). Importantly, protests are useful in raising awareness (e.g., Bugden, 2020) as well as mobilizing and motivating people in other places to take similar action (e.g., Drury et al., 2020), providing an opportunity for more people to get involved (Ramsden, 2020). Seeing others take action, or when there is a perception of many taking action has an impact on the perceived collective efficacy (e.g., Haugestad et al., 2021). Furthermore, the more people that join, the more inclusive the shared category gets, which allows for more people to identify with the group and the causes (Louis et al., 2016). Hence, some elements of the pandemic might have allowed for increased mobilization and collective action activity through exposure to the common predictors of collective action (identity, injustice, efficacy; van Zomeren et al., 2008).

During the pandemic, several areas of protest causes have been observed. For example, BLM protests2 have been a recurring feature worldwide during the pandemic. Similarly, anti-lockdown protests have been reported from various countries such as Italy3, Germany and France4, and the US5 to name a few. The pandemic exposed already existing unequal societal systems, and increased inequalities further in already marginalized communities (Templeton et al., 2020). Iacoella et al. (2021) argues that in the US, counties with existing high inequality were more likely to experience protests in relation to negative consequences of the pandemic. Marginalized communities are often characterized by an existing lack of trust in governmental measures (see Williams, 1998; Murphy and Cherney, 2017). Additionally, enforcement of strict pandemic measures, leading to increase in protest, hit marginalized communities hardest as they lack financial and social buffers, hence restrictions limit their access to basic survival means (Iacoella et al., 2021). People that lost their jobs or had other financial issues because of the pandemic were found to be more likely to participate in the BLM protests, through a wider framework of opposing inequality and police brutality (Arora, 2020). Furthermore, of their surveyed participants, Arora (2020) found that 52% had been affected negatively financially by the pandemic. In terms of ethnicity, 69% of black participants, compared to 46% of white participants, reported financial hardship caused by the pandemic. Although all participants agreed with the wider cause of the protests (i.e., racial injustice), Arora (2020) emphasized that the pandemic was the factor that made them take to the streets. Hence, the management of and response to the COVID-19 pandemic increased the perceived collective injustice, anger, as well as solidarity leading to mobilization for various protests and collective actions. It should be acknowledged that the media, police, and authorities' responses, and safety for protestors, differ with the impact of White privilege. Hence, different responses from the media, police, and authorities to BLM vs. for example anti-lockdown protests are likely based on structural racial injustices and White privilege. The injustice and privilege can create differences to the mobilization process as well as feelings of efficacy and safety of these protests. Relatedly, social injustices and inequalities have increased or been made more visible through the COVID-19 pandemic (Templeton et al., 2020; Iacoella et al., 2021) making the injustice and privilege more transparent.

The worldwide BLM protests, after the killing of George Floyd (May 25th 2020), coincided with the early stages of global outbreak and enforcement of national measures to try to manage the transmission of the corona virus (SARS-CoV-2). During the week after the killing of George Floyd more than 8,700 protests were recorded across 74 countries (Kishi and Jones, 2020). In total in the US, over 10 600 protests were recorded between 24th May and 22nd August 2020 (Kishi and Jones, 2020). In line with general patterns of protest, more than 90% of the protests were peaceful (Kishi and Jones, 2020). In America, 11 Americans were killed while participating in political protests, 9 of these were from BLM and 2 from pro-Trump protests, and an additional 14 were killed in related events (Beckett, 2020). The legitimacy of the protests during the pandemic became the subject of heated discussions. On the one hand, the protests were described as events that accelerated the spread of the coronavirus and were discussed as a public health threat (see Section Protests and virus spread—Delegitimization of protesting social injustice?). On the other hand, governments and state actors (e.g., police) were accused of attacking the right to protest by using lockdowns and pandemic measures as excuses to clamp down on protesters.

The global spread of the virus with accompanying measures to reduce viral transmission put public health and public welfare (societal inequality) at odds. The restrictions to reduce viral spread affected people's perceived freedom of movement, assembly, and expression. “New” legislation to protect public health also provided authorities with more ground to strike down on protests (Kampmark, 2020). For example, in the UK during the early stages of the pandemic (until the end of May 2020) assemblies outdoors of more than three people were unlawful, it was later changed to allowing six people to gather (Kampmark, 2020). Similarly, in New South Wales, Australia, police tried to block demonstrations and threatened potential protesters with fines for breaching health orders, based on the argument (without evidence) that BLM protests had led to high infection rates (Kontominas, 2020). Drawing on the restrictions in mobility allowing only “essential activity” police in both the US (NCAC, 2020) and Australia (O'Sullivan, 2020) dispersed or fined protesters even though they were socially distancing (e.g., being inside their cars). The added public health legislation might also be a factor in police use of force during protests. In 2020 the US authorities intervened in 9% of all protests, compared to 2% in 2019 (Kishi and Jones, 2020). It should also be noted that authorities intervened in 9% of all BLM protests in the US, compared to 2% for other protests, with 5% of BLM protests being met with force compared to <1% for other protests (Kishi and Jones, 2020). This disproportionality, in turn, can further fuel the perception of inequality and societal and racial injustice.

To sum up, inaction and failures by governments to manage the pandemic have functioned to increase existing social injustice, thereby fuelling protests (Kishi et al., 2021) during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is complementary with our argument that previous (pre-COVID) disaster-related protests are triggered not by the destructive impact of nature, but the unequal and ineffective responses by governments creating a platform for the predictors of collective action (see Figure 1). Moreover, in disaster-related protests before and during the COVID-19 people share and enact their social identities around a narrative of social injustice and inequalities. In the next, and final section, we address how disaster characteristics can be used to attempt to delegitimize protest causes, actions and movements.

Protests and virus spread—Delegitimization of protesting social injustice?

During the pandemic, protests around the world, such as BLM protests in the US, farmer resistance in India, protests against violence toward women in the UK, and Bogaziçi resistance in Turkey were subject to heavy-handed policing or police brutality, justified by citing COVID-19 pandemic and health measures (e.g., Stott et al., 2021). Media as well as politicians and others took part in suppressing and delegitimizing social justice protests during the pandemic using arguments of viral transmission rates. However, when exploring the evidence for viral transmission during protests, the picture becomes different to that painted by state actors, media and opposers to the protest causes (e.g., Kampmark, 2020).

One strong proponent of the argument that protests increased viral transmission (without evidence) was the media. For example, the Herald Sun (Australia) blamed the BLM protests for the spike in infections (Tavan, 2020). When it was later shown that there were no new infections related to the protests the accusation changed to the argument that protests encouraged people to come out of their homes—consequently spreading the virus (it was later shown that the spike was related to companies failing to report positive cases within employee groups) (Tavan, 2020). Social injustice and White privilege can also be seen in the media reporting. For example, BLM protests attracted media and politicians' attention in relation to increasing the spread, whereas mainly White anti-lockdown protests did not. This pattern was seen in most Northern American and Western European countries indicating that the perceived viral spread is related to structural injustices and privileges6.

In relation to the BLM protests, it has been argued that there is no clear evidence of a protest-related increase in the transmission of the coronavirus (Berger, 2020). There have even been suggestions that the large BLM protests resulted in a decrease in viral transmission (e.g., Dave et al., 2021a). The lack of viral transmission during protests was linked to protests being held outdoors, often in sunny weather, and in a context where most people were wearing masks and physically moving (Berger, 2020). Using cell-phone data and coronavirus data to assess the viral transmission in relation to BLM protests in large cities in the US, Dave et al. (2021a) suggests that the viral transmission and the growth of the virus, for 35 days post-protests (measured in 242 cities), decreased. They explain the decrease though protesters mainly adhering to mask-wearing and socially distancing coupled with expected behaviors the protesters would have engaged in if not protesting (e.g., meeting up in restaurants or other indoor areas etc.). In cities where there were large protests, indoor venues (e.g., restaurants and smaller shops) closed, and locals not involved in the protests stayed at home rather than going about with their normal day-to-day behaviors which would have been riskier in terms of viral spread. Furthermore, Dave et al. (2021a) noted that in the surrounding areas of the cities with protests, there were no increase in the viral spread—hence, the BLM protest, as well as other protests with similar features, cannot be considered as super-spreader events, or even spreader events. Hence, as the evidence points in an opposite direction to state and others' arguments, we can only postulate the reason for the persisting narrative of spread and endangering the population. A similar tactic has been used previously against social justice protests to delegitimize movement and movement participants (e.g., Tekin and Drury, 2021b). Misrepresentation of disaster properties have been used politically to delegitimize causes and movements. The misrepresentation of disaster properties, such as accusations of viral spread, can increase social injustice as well as be damaging to collective engagement and community resilience and recovery, creating divisions rather than solidarity during and after disasters.

However, some protests (or collective events) have been found to increase viral transmission. Anti-lockdown protests in Germany (“hygiene demo”) increased the viral transmission across the protesters' residential areas post-protests (Lange and Monscheuer, 2021). Lange and Monscheuer (2021) explain the increase in viral transmission through the protesters (e.g., COVID-deniers) being less likely to adhere to protective health measures. Similarly, in mid-August 2020, about 500 000 motorcycle enthusiasts gathered in Sturgis, South Dakota, US for a motorcycle rally. Dave et al. (2021b) found that the event was mainly characterized by non-mask wearing and non-adherence to other protective guidelines, as well as a general opposition to the pandemic “we're being human once again. Fuck that COVID-shit” (p. 770). Through cell-phone data, Dave et al. (2021b) found that indoor venues such as restaurants in the area had an increase in customers by 30–90%. In the month following the rally, viral transmission and positive COVID-19 cases increased substantially in the counties with large numbers of rally participants. Again, there needs to be attention to the difference in reporting between BLM protests on one side and the anti-lockdown protests and Sturgis rally on the other. It can be argued that once again there is an issue with privilege and systemic injustice, blaming one movement but not another.

A key difference between the events described above (BLM, “hygiene demo” and the Sturgis rally) is the behavioral norms within the groups. During the BLM protests, most participants were wearing masks and socially distanced (Berger, 2020; Dave et al., 2021a). Conversely, during the German anti-lockdown protest as well as the Sturgis rally, the crowd was mainly characterized by opposition to COVID-measures, as well as lack of mask wearing and social distancing (Dave et al., 2021b; Lange and Monscheuer, 2021). In crowd events such as protests and rallies a shared social identity often emerges (e.g., Reicher, 1984). The social identity, shared with other protest participants, provides us with definitions of possible and appropriate conduct, and enables people to act collectively in normative ways according to ingroup norms (see Drury and Reicher, 2000; Neville et al., 2021). When a social identity is salient, people will view themselves as a member of that group identity and act according to the identity norms and values. Hence, if part of your social identity is to oppose COVID-restriction, or deny the very existence of COVID-19, then you are less likely to take protective measures while in the protest context of anti-lockdown measures. Conversely, if part of your identity is to protect vulnerable or minoritized people/populations such as the BLM protests (or climate protests which are also characterized by protective measures7,8,9), then you may be more likely to wear a mask and keep social distance during the protest. Importantly, based on the studies provided above, although still very limited in numbers, and the social identity framework of protest participation (see e.g., Drury and Reicher, 2000; Vestergren et al., 2019) we argue that protests with norms of protective behaviors (e.g., mask wearing and social distancing) are unlikely to become “super-spreader” events, or even spreader events. However, if a group norm is to oppose all COVID-19 protective measures, then the protest has a great potential to contribute to widespread viral transmission due to participants acting according to the group norms. Consequently, protests in themselves should not be seen as “super-spreaders”—contextual factors and the salient social identity (with ingroup values and norms that guide behavior) determine whether a protest increases or decreases the spread of the coronavirus. Importantly, as demonstrated through the examples of protests, understanding dimensions of social identity content, such as shared norms can facilitate in harnessing the power of the collective and aid in community recovery and resilience during and after disasters. However, indiscriminately accusing protests of, for example, endangering the population risks delegitimizing the movement, the movement participants, and also the cause of the movement which in turn can increase social injustice.

Conclusion

Disaster-related protests follow the same pattern of social psychological predictors as non-disaster protests. However, disasters are likely to accelerate and amplify those predictors through state inaction making already disadvantaged groups and areas even more disadvantaged (see Figure 1). As disasters often contains the prerequisites for collective action participation—maybe the question that should be asked next is “why do protests not occur after disasters?”. One potential factor to the lack of disaster-related protests could be the need to prioritize the cooperation route (see e.g., Cocking et al., 2009; Drury et al., 2009) to ensure one self's and others' survival. However, we argue that due to the likelihood of an increase in number and severity of disasters due to the climate crisis (e.g., Van Aalst, 2006; Benevolenza and DeRigne, 2019), we need more research on the link between disasters and protest such as protesters' understanding of a protest during a disaster vs. after a disaster to further understand the components of mobilization and resilience.

Slettebak (2013) notes that a storm (or other mass-event) is only a storm until it has human consequences/costs, then it becomes a disaster. The COVID-19 pandemic has become highly politicized (Kishi and Jones, 2020) and through exposing and accelerating social inequalities, the pandemic offered more opportunities to exposure and mobilization to movements. Even though it has been widely argued that protests are “super-spreaders,” this argument cannot be generalized to all protests, and risks delegitimizing movements and causes as well as creating divisions. Protestors or people and their actions affected by the disasters are often blamed or criminalized, delegitimizing their aims and actions, for example by blaming them for virus spread or portraying them as looters. The influence of third-party narratives (e.g., media, politicians) need to be explored to address the way they might hinder community recovery after disasters by delegitimizing (and sometimes criminalizing) the victims, movements, and societal causes leading to increased social injustice. Future research should focus on how these systemic injustices occur and how people take action to fight them or survive in an unjust system amplified by poorly managed disasters. For example, focus on the kind of strategies people use for public safety and seeking justice.

Finally, a limitation with the proposed model (Figure 1) as with most collective action models is the lack of holistic dynamic application. For example, SIMCA (van Zomeren et al., 2008) and SIRDE (e.g., Grant et al., 2015) treat identity as a predictor, and EMSICA (Thomas et al., 2012) and the Normative Alignment Model (Thomas et al., 2009) treat identity as an outcome. However, identity function both as a predictor for mobilization as well as an outcome of that mobilization. In the case of perceived injustice, on the one hand, identity can be an outcome of a sense of shared grievance, on the other, our sense of collective grievance is based on who we think we are (identity). One model that attempts to emphasize a dynamic nature of identity and how it is re-assessed and negotiated based on the everchanging social context is Elaborated Social Identity Model of Crowd Behavior (ESIM; e.g., Stott and Reicher, 1998; Drury and Reicher, 2000). Following suggestions for a need of more dynamic identity theorizing (e.g., Cammaerts, 2021), applications of the proposed model should therefore attempt to account for the dynamic interrelations between the variables, as well as the dynamic social context to capture the dynamic processes of interrelations between the variables.

To sum up, this conceptual piece has argued for an elaborated model of collective action and disasters, emphasizing the link of social injustice between disasters and protests, while also addressed how misinterpretations of disaster properties can damage the movement, community recovery and increase social injustice. As a result of the climate crisis, we can expect an increase in both the number and severity of disasters globally, resulting in further social, ecological, and economical injustice, and consequently increase in protests and collective actions. A key for future research in social movements and collective actions should be how to harness the collective for social change and community resilience and recovery in the context of climate crisis.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

Funding for Open Access Publication is applied from the Thüringer Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek (Thuringian University and State Library; ThULB) which serves as the research library for the Friedrich Schiller University Jena.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Turkish singer and ecological activist who passed away in 2005 from cancer, just 33 years old. Cancer cases triple in the Black Sea region of Turkey just in a decade after the Chernobyl disaster (https://www.aa.com.tr/en/health/chernobyl-health-effects-in-turkey-hotly-debated/164471), he was one of the thousands who developed and passed away from cancer in that area.

2. ^https://www.cntraveler.com/gallery/black-lives-matter-protests-around-the-world

3. ^https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-54701042

4. ^https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/02/latest-coronavirus-lockdowns-spark-protests-across-europe

5. ^https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/world-us-canada-52344540

6. ^https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/07/black-lives-matter-protests-risk-spreading-covid19-says-matt-hancock https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jul/22/trump-coronavirus-briefing-black-lives-matter-protests

7. ^https://grist.org/climate/despite-Covid-19-young-people-resume-global-climate-strikes/

8. ^https://www.dw.com/en/coronavirus-fridays-for-future-fff-Covid-19-pandemic-climate-strike/a-56911641

9. ^https://www.france24.com/en/20200925-masks-up-emissions-down-as-climate-demos-restart

References

Aldrich, D. (2013). Rethinking civil society-state relations in Japan after the Fukushima accident. Polity 45, 249–269. doi: 10.1057/pol.2013.2

Alfadhli, K., and Drury, J. (2018). The role of shared social identity in mutual support among refugees of conflict: an ethnographic study of Syrian refugees in Jordan. J. Commun. Appl. Psychol. 28, 142–155. doi: 10.1002/casp.2346

Arora, M. (2020). How the Coronavirus Pandemic Helped the Floyd Protests Become the Biggest in United States History. Maryland: The Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/08/05/how-coronavirus-pandemic-helped-floyd-protests-become-biggest-us-history/ (accessed December 14, 2021).

Becker, J., Tausch, N., and Wagner, U. (2011). Emotional consequences of collective action participation: differentiating self-directed and outgroup-directed emotions. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 37, 1587–1598. doi: 10.1177/0146167211414145

Beckett, L. (2020). At Least 25 Americans Were Killed During Protests and Political Unrest in 2020. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/31/americans-killed-protests-political-unrest-acled (accessed December 14, 2021).

Benevolenza, M., and DeRigne, L. A. (2019). The impact of climate change and natural disasters on vulnerable populations: a systematic review of literature. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 29, 266–281. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2018.1527739

Berger, M. (2020). Why the Black Lives Matter Protests Didn't Contribute to the COVID-19 Surge. Healthline. Available online at: https://www.healthline.com/health-news/black-lives-matter-protests-didnt-contribute-to-covid19-surge (accessed December 14, 2021).

Blackwood, L., and Louis, W. (2012). If it matters for the group then it matters to me: collective action outcomes for seasoned activists. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 51, 72–92. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02001.x

Branscombe, N., Schnitt, M., and Harvey, R. (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: implications for group identification and well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 77, 135–149. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.135

Bugden, D. (2020). Does climate protest work? Partisanship, protest, and sentiment pools. Socius Sociol. Res. Dyn. World 6, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/2378023120925949

Cammaerts, B. (2021). The new-new social movements: are social media changing the ontology of social movements? Mobil. Int. Quart. 26, 343–358. doi: 10.17813/1086-671X-26-3-343

Cocking, C., Drury, J., and Reicher, S. (2009). The nature of collective “resilience”: survivor reactions to the July 7th (2005) London bombings. Int. J. Mass Emerg. Disast. 27, 66–95.

Cronin, M. (2017). Loss, protests, and heritage: liverpool FC and hillsborough. Int. J. Hist. Sport 34, 251–265. doi: 10.1080/09523367.2017.1369965

Dave, D., Friedson, A., Matsuzawa, K., Sabia, J., and Safford, S. (2021a). Black Lives Matter Protests and Risk Avoidance: The Case of Civil Unrest During a Pandemic. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 27408. Available online at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w27408 (accessed December 14, 2021).

Dave, D., McNichols, D., and Sabia, J. (2021b). The contagion externality of a superspreading event: the Sturgis motorcycle rally and COVID-19. South. Econ. J. 87, 769–807. doi: 10.1002/soej.12475

Drury, J. (2018). The role of social identity processes in mass emergency behaviour: an integrative review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 29, 38–81. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2018.1471948

Drury, J., Brown, R., González, R., and Miranda, D. (2016). Emergent social identity and observing social support predict social support provided by survivors in a disaster: solidarity in the 2010 Chile earthquake. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 46, 209–223. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2146

Drury, J., Cocking, C., and Reicher, S. (2009a). Everyone for themselves? A comparative study of crowd solidarity among emergency survivors. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 487–506. doi: 10.1348/014466608X357893

Drury, J., and Reicher, S. (1999). The intergroup dynamics of collective empowerment: substantiating the social identity model of crowd behaviour. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2, 381–402. doi: 10.1177/1368430299024005

Drury, J., and Reicher, S. (2000). Collective action and psychological change: the emergence of new social identities. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 39, 579–604. doi: 10.1348/014466600164642

Drury, J., and Reicher, S. (2005). Explaining enduring empowerment: a comparative study of collective action and psychological outcomes. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 35, 35–58. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.231

Drury, J., and Reicher, S. (2009). Collective psychological empowerment as a model of social change: researching crowds and power. J. Soc. Issues 65, 707–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01622.x

Drury, J., Stott, C., Ball, R., Neville, F., Bell, L., Biddlestone, M., et al. (2020). A social identity model of riot diffusion: from injustice to empowerment in the 2011 London riots. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 50, 646–661. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2650

Fernandes-Jesus, M., Mao, G., Ntontis, E., Cocking, C., McTague, M., Schwarz, A., et al. (2021). More than a COVID-19 response: sustaining mutual aid groups during and beyond the pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 4809. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.716202

Flesher Fominaya, C. (2011). The Madrid bombings and popular protest: misinformation, counterinformation, mobilisation and elections after '11-M'. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 6, 289–307. doi: 10.1080/21582041.2011.603910

Funabashi, Y., and Kitazawa, K. (2012). Fukushima in review: a complex disaster, a disastrous response. Bull. Atom. Sci. 68, 9–21. doi: 10.1177/0096340212440359

Grant, P., Abrams, D., Robertson, W., and Garay, J. (2015). Predicting protests by disadvantaged skilled immigrants: a test of an integrated social identity, relative deprivation, collective efficacy (SIRDE) model. Soc. Just. Res. 28, 76–101. doi: 10.1007/s11211-014-0229-z

Grant, P., and Smith, H. (2021). Activism in the time of COVID-19. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 24, 297–305. doi: 10.1177/1368430220985208

Grimm, S., Lemay-Hérbert, N., and Nay, O. (2014). ‘Fragile States': introducing a political concept. Third World Quart. 35, 197–209. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2013.878127

Haugestad, C., Duun Skauge, A., Kunst, J., and Power, S. (2021). Why do youth participate in climate activism? A mixed-methods investigation of the #FridaysForFuture climate protests. J. Environ. Psychol. 76, 101647. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101647

Heldman, C. (2010). The Truths of Katrina. Available online at: https://drcarolineheldman.com/2010/08/25/the-truths-of-katrina/ (accessed December 14, 2021).

Iacoella, F., Justino, P., and Martorano, B. (2021). Do Pandemics Lead to Rebellion? Policy Responses to COVID-19, Inequality, and Protests in the USA (WIDER Working Paper No. 2021/57). World Institute for Development Economics Research. Available online at: https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/Publications/Working-paper/PDF/wp2021-57-pandemics-rebellion-policy-responses-COVID-19-inequality-protests-USA.pdf (accessed March 24, 2022).

Ide, T., Kristensen, A., and Bartusevičius, H. (2021). First comes the river, then comes the conflict? A qualitative comparative analysis of flood-related political unrest. J. Peace Res. 58, 83–97. doi: 10.1177/0022343320966783

Ikegami, Y. (2012). People's movement under the radioactive rain. Inter-Asia Cult. Stud. 13, 153–158. doi: 10.1080/14649373.2012.639338

International Federation of Red Cross Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). (2022). What is a Disaster? Available online at: https://www.ifrc.org/what-disaster (accessed April 25, 2022).

Kampmark, B. (2020). Protesting in pandemic times. Contention 8, 1–20. doi: 10.3167/cont.2020.080202

Kishi, R., and Jones, S. (2020). Demonstrations and Political Violence in America: New Data for Summer 2020. Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project. Available online at: https://acleddata.com/2020/09/03/demonstrations-political-violence-in-america-new-data-for-summer-2020/ (accessed December 14, 2021).

Kishi, R., Pavlik, M., Bynum, E., Miller, A., Goos, C., Satre, J., et al. (2021). ACLED 2020: The Year in Review. Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project. Available online at: https://acleddata.com/2021/03/18/acled-2020-the-year-in-review/ (accessed December 14, 2021).

Klandermans, B. (1984). Mobilization and participation: social-psychological expansions of resource mobilization theory. Am. Sociol. Rev. 49, 583–600. doi: 10.2307/2095417

Kontominas, B. (2020). NSW Police Try to Block Sydney Black Lives Matter Protest in Supreme Court Due to Coronavirus Concerns. ABC News. Available online at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-07-20/nsw-police-to-block-sydney-black-lives-matter-protest-in-court/12474464 (accessed December 14, 2021).

Koren, O., Bagozzi, B., and Benson, T. (2021). Food and water insecurity as causes of social unrest: evidence from geolocated Twitter data. J. Peace Res. 58, 67–82. doi: 10.1177/0022343320975091

Lange, M., and Monscheuer, O. (2021). Spreading the Disease: Protest in Times of Pandemics. ZEW Discussion paper, NO.21-009. Available online at: https://ftp.zew.de/pub/zew-docs/dp/dp21009.pdf (accessed March 24, 2022).

Louis, W., Amiot, C., Thomas, E., and Blackwood, L. (2016). The “activist identity” and activism across domains: a multiple identities analysis. J. Soc. Issues 72, 242–263. doi: 10.1111/josi.12165

Luft, R. E. (2009). Beyond disaster exceptionalism: social movement developments in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Am. Quart. 61, 499–527. Available online at: https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/317270

Mao, G., Fernandes-Jesus, M., Ntontis, E., and Drury, J. (2021). What have we learned about COVID-19 volunteering in the UK? A rapid review of literature. BMC Public Health 21, 1470. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11390-8

Marks, D., Connell, J., and Ferrara, F. (2020). Contested notions of disaster justice during the 2011 Bangkok floods: unequal risk, unrest and claims to the city. Asia Pac. Viewpoint 61, 19–36. doi: 10.1111/apv.12250

Murphy, K., and Cherney, A. (2017). “Policing marginalized groups in a diverse society: using procedural justice to promote group belongingness and trust in police,” in Police-Citizen Relations Across the World: Comparing Sources and Contexts of Trust and Legitimacy, eds D. Oberwittler, and S. Roche (New York, NY: Routledge), 153–174. doi: 10.4324/9781315406664-7

Nardulli, P., Peyton, B., and Bajjalieh, J. (2015). Climate change and civil unrest: the impact of rapid-onset disasters. J. Confl. Resol. 59, 310–335. doi: 10.1177/0022002713503809

NCAC. (2020). The Right to Protest During the Pandemic. National Coalition Against Censorship. Available online at: https://ncac.org/news/dissent-protest-pandemic (accessed December 14, 2021).

Nel, P., and Righarts, M. (2008). Natural disasters and the risk of violent civil conflict. Int. Stud. Quart. 52, 159–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00495.x

Neville, F., Templeton, A., Smith, J., and Louis, W. (2021). Social norms, social identities and the COVID-19 pandemic: theory and recommendations. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 15, e12596. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12596

Ntontis, E., Drury, J., Amlôt, R., Rubin, G. J., Williams, R., and Saavedra, P. (2020). Collective resilience in the disaster recovery period: emergent social identity and observed social support are associated with collective efficacy, well-being, and the provision of social support. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 60, 1075–1095. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12434

Ntontis, E., Drury, J., Amlôt, R., Rubin, J. G., and Williams, R. (2018). Emergent social identities in a flood: implications for community psychosocial resilience. J. Commun. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 28, 3–14. doi: 10.1002/casp.2329

O'Sullivan, M. (2020). Is Protesting During the Pandemic an 'Essential' Right that Should be Protected? The Conversation. Available online at: https://theconversation.com/is-protesting-during-the-pandemic-an-essential-right-that-should-be-protected-136512 (accessed December 14, 2021).

Ramsden, P. (2020). How the Pandemic Changed Social Media and George Floyd's Death Created a Collective Conscience. The Conversation. Available online at: https://theconversation.com/how-the-pandemic-changed-social-media-and-george-floyds-death-created-a-collective-conscience-140104 (accessed December 14, 2021).

Reicher, S. (1984). The St. Pauls' riot: an explanation of the limits of crowd action in terms of social identity model. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 14, 1–21. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420140102

Runciman, W. (1966). Relative Deprivation and Social Justice: A Study of Attitudes to Social Inequality in Twentieth-Century England. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Slettebak, R. (2013). Climate change, natural disasters, and post-disaster unrest in India. India Rev. 12, 260–279. doi: 10.1080/14736489.2013.846786

Solnit, R. (2009). A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster. New York, NY: Penguin.

Stott, C., Radburn, M., Pearson, G., Kyprianides, A., Harrison, M., and Rowlands, D. (2021). Police powers and public assemblies: learning from the Clapham Common ‘Vigil' during the Covid-19 pandemic. Polic. J. Policy Pract. 16, 73–94. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/7jcsr

Stott, C., and Reicher, S. (1998). Crowd action as intergroup process: introducing the police perspective. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 26, 509–529. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199807/08)28:4<509::AID-EJSP877>3.0.CO;2-C

Subašić, E., Reynolds, K., and Turner, J. (2008). The political solidarity model of social change: dynamics of self-categorization in intergroup power relations. Person. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 12, 330–352. doi: 10.1177/1088868308323223

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. (1979). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict,” in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds W. G. Austin, and S. Worchel (Salt Lake City, UH: Brooks/Cole), 33–48.

Tavan, L. (2020). Who's to Blame for Victoria's COVID-19 Spike? Redflag: A Publication of Socialist Alternative. Available online at: https://redflag.org.au/node/7252 (accessed December 14, 2021).

Tekin, G. S, and Drury, J. (2020). How do those affected by a disaster organize to meet their needs for justice? Campaign strategies and partial victories following the Grenfell Tower fire. SocArXiv [Preprint]. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/srh4p

Tekin, G. S, and Drury, J. (2021a). Silent walk as a street mobilization: campaigning following the Grenfell Tower fire. J. Commun. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 31, 425–437. doi: 10.1002/casp.2521

Tekin, G. S, and Drury, J. (2021b). A critical discursive psychology approach to understanding how disasters are delegitimized by hostile Twitter posts: racism, victim-blaming, and forms of attack following the Grenfell Tower fire. J. Commun. Appl. Psychol. Early View. doi: 10.1002/casp.2596

Templeton, A., Tekin Guven, S., Hoerst, C., Vestergren, S., Davidson, L., Ballentyne, S., et al. (2020). Inequalities and identity processes in crises: recommendations for facilitating safe response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 59, 674–685. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12400

Thomas, E., Mavor, K. I., and McGarty, C. (2012). Social identities facilitate and encapsulate action-relevant constructs: a test of the social identity model of collective action. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 15, 75–88. doi: 10.1177/1368430211413619

Thomas, E., McGarty, C., and Mavor, K. (2009). Aligning identities, emotions, and beliefs to create commitment to sustainable social and political action. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 13, 194–218. doi: 10.1177/1088868309341563

Tierney, K., Bevc, C., and Kuligowski, E. (2006). Metaphors matter: disaster myths, media frames, and their consequences in Hurricane Katrina. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 604, 57–81. doi: 10.1177/0002716205285589

Van Aalst, M. (2006). The impacts of climate change on the risk of natural disasters. Disasters 30, 5–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2006.00303.x

van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., and Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: a quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychol. Bull. 134, 504–535. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504

van Zomeren, M., Spears, R., Fisher, A., and Leach, C. (2004). Put your money where your mouth is! Explaining collective action tendencies through group-based anger and group efficacy. J. Persoanl. Soc. Psychol. 87, 649–664. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.649

Vestergren, S., Drury, J., and Hammar Chiriac, E. (2019). How participation on collective action changes relationships, behaviours, and beliefs: an interview study of the role of inter- and intragroup processes. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 7, 76–99. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v7i1.903

Walker, I., and Smith, H. J., (eds.). (2002). Relative Deprivation: Specification, Development, and Integration. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, M. S. (1998). Voice, Trust, and Memory: Marginalized Groups and the Failings of Liberal Representation. New York, NY: Princeton University Press.

Wlodarczyk, A., Basabe, N., Paez, D., and Zumeta, L. (2017). Hope and anger mediators between collective action frames and participation in collective mobilization: the case of 15-M. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 5, 200–223. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v5i1.471

World Health Organization (WHO). (2002). Disasters and Emergencies. Definitions. Panafrican Emergency Training Centre. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/disasters/repo/7656.pdf (accessed April 25, 2022).

Keywords: protest, disaster, COVID-19, pandemic, injustice, inequality

Citation: Vestergren S, Uysal MS and Tekin S (2022) Do disasters trigger protests? A conceptual view of the connection between disasters, injustice, and protests—The case of COVID-19. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:836420. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.836420

Received: 15 December 2021; Accepted: 20 July 2022;

Published: 09 August 2022.

Edited by:

Sharon Coen, University of Salford, United KingdomReviewed by:

Jenna Condie, Western Sydney University, AustraliaZira Hichy, University of Catania, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Vestergren, Uysal and Tekin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mete Sefa Uysal, bWV0ZS51eXNhbEB1bmktamVuYS5kZQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Sara Vestergren

Sara Vestergren Mete Sefa Uysal

Mete Sefa Uysal Selin Tekin

Selin Tekin