94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Front. Polit. Sci., 03 February 2022

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.797331

This article is part of the Research TopicOrigins, Foundations, Sustainability and Trip Lines of Good Governance: Archaeological and Historical ConsiderationsView all 14 articles

Among the Indigenous polities of precolonial Mesoamerica, the Aztec empire, headed by a confederation of three city-states, was the largest recorded and remains the best understood, due to its chronicling in Spanish and Nahuatl texts following the Spanish-Aztec war and colonial transformation to New Spain. Yet its political organization is routinely mischaracterized in popular media, and lesser-known contemporaries and predecessors in central Mexico exhibit variability in governing strategies over time and space of interest to comparatively oriented scholars of premodern polities. Common themes in governance tended to draw from certain socio-technological realities and shared ontologies of religion and governing ideologies. Points of divergence can be seen in the particular entanglements between political economies and the settings and scales of collective action. In this paper, I review how governance varied synchronically and diachronically in central Mexico across these axes, and especially in relation to resource dilemmas, fiscal financing, the relative strength of corporate groups versus patron-client networks, and how rulership was legitimated.

The gulf in understanding between popular media coverage and specialist discourse on the political organization of the Aztecs is surely one of the largest among the world’s precolonial, non-Western societies. Popular accounts concentrate disproportionately on the politico-religious spectacle of human sacrifice at the Mexica-Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan—the dominant polity in the Triple Alliance empire—with coverage of new archaeological discoveries of skull-racks and the like serving as online click-bait that is typically decontextualized from practices of Mexica warfare, religion, or other facets of societal organization. An analogy might be depictions of imperial Rome focusing primarily on crucifixions, gladiatorial combat, and episodes of take-no-prisoners or sowing-fields-with-salt warfare to an audience unfamiliar with that society. Stemming from such a skewed representation, a layperson could be excused for thinking that Mexica, or Roman, governance was despotic and repressive, and that assumption may transfer to their lesser-known contemporaries and predecessors.

As other contributions to this issue demonstrate, this was neither the case in early Mesoamerica—comprising roughly the southern two-thirds of Mexico and adjacent countries of Central America—nor in many other parts of the precolonial Americas. Comparative analyses grounded in collective-action theory and its relationship with sources of fiscal financing (e.g., Levi 1988; Blanton and Fargher 2008; Blanton et al., 2020, 2021), and those documenting how barriers to the monopolization, or significant control over, valued external spot resources or extensive plough agriculture in the Americas (e.g., Boix 2015; Kohler et al., 2017; Kohler and Smith, 2018), combine to illuminate the alternative trajectories of societies exhibiting lower measures of social inequality and more pluralistic governance than their Eurasian counterparts. In the United States we use the Algonquin term caucus to refer to a cherished democratic process, and the nation’s founding figures established notions of liberty in a “New World” through symbolic appropriation of Native societies, but we continue to lose sight of the more pluralistic institutions that could exist in systems of governance of the precolonial Americas (Johansen 1996).

In this article, I combine insights from archaeology, history, and ethnography to consider over a millennium of political strategies in precolonial central Mexico, spanning some of the earliest urban centers in the region to it becoming the core of the Aztec empire. Archeology is the discipline that offers the most varied and temporally deep material record of human social change relevant to understanding long trajectories and variability in governance and their relationship to ecological and historical factors. Nevertheless, in its ambitious goal of studying the entirety of the human experience—the evolution of our species to the present day—archaeologists must foster stronger dialog with research from other fields, especially including political scientists, when considering variability in political organization and strategies of governance. I draw here on comparative research by social theorists such as Ostrom et al. (1994) and Levi (1988) in considering how governance varied diachronically in relation to resource dilemmas, fiscal financing, corporate groups, ritual practices, and how rulership was legitimated. This comparative, deep-time perspective also aligns with historical analyses that emphasize political economy and the financial underpinnings of rulership in drawing distinctions between extractive and inclusive political economies or absolutist and pluralistic polities (Acemoglu and Robinson 2013; Boix 2015). I aim to show how such analyses can be furthered through inclusion of the insights derived from the study of human-environment interactions and the material correlates of changes in political and economic organization in deep historical perspective.

With a socio-technological backdrop that included few utilitarian applications of metallurgy and the complete absence of large, domesticated animals, precolonial Mesoamerica contrasts with other world regions of primary state formation. Mesoamericans oversaw profound transformations in the scale and administrative complexity of polities, but these were associated with changes in labor relations and how cooperative networks functioned rather than with major changes in technology or the harnessing of energy (Feinman and Carballo 2018). The ecology and economies of Mesoamerica featured relatively few possibilities for political elites to exploit technological and exchange bottlenecks or to consolidate large tracts of agricultural fields enabled by plough agriculture. This differs significantly from various core regions of early states in Eurasia, where political elites had greater opportunities to monopolize or disproportionately control raw material sources and larger tracts of land, or to take advantage of production bottlenecks in certain industries of craft manufacturing (Carballo 2020a: 9–12, 107–125; Kohler et al., 2017; Morris 1989). Other related pivots in Eurasian political evolution include changes in the relative advantages offered by offensive or defensive military capacities that came with mounted cavalry, chariots, naval technologies, and increasingly elaborate fortifications (Morris 2010; Boix 2015; Turchin et al., 2021), all of which either do not apply at all to Mesoamerica or do but to a much lesser degree. In some cases, Eurasian political elites were able to significantly control military and transportation technologies, fostering more absolutist polities, whereas in others these technologies were distributed widely and provided balances to absolutist power, instead fostering more pluralistic or heterarchical political arrangements.

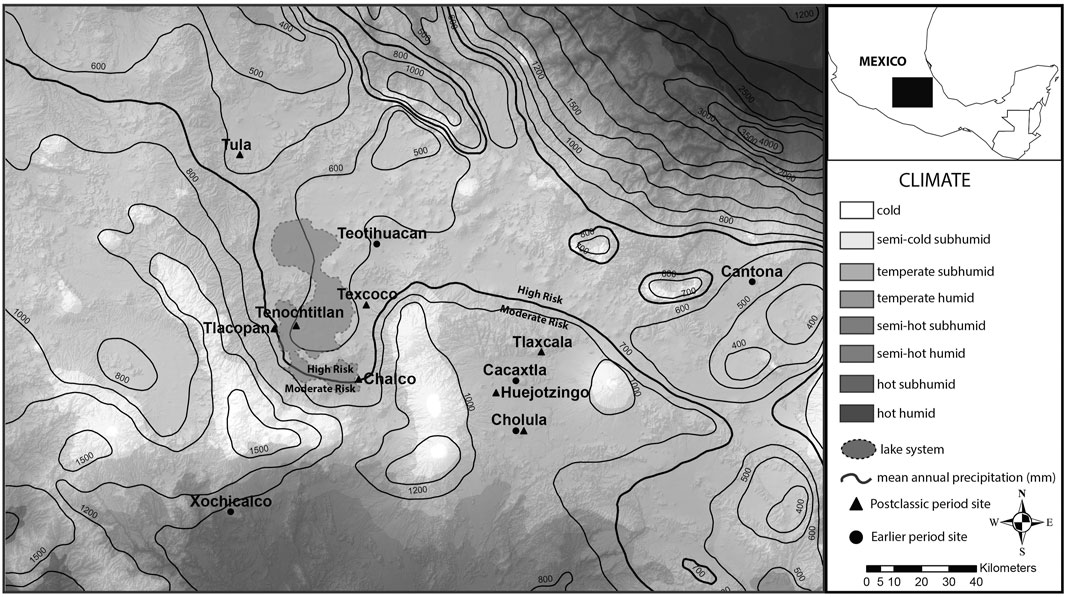

Central Mexico’s ecological setting features a combination of tropical latitudes and mountainous terrain that resulted in the distribution of a diversity of complementary resources in adjacent regions, a situation that scholars have long noted encouraged economic symbiosis and cultural exchanges (Hirth 2013; Sanders 1956). With valley floors typically situated 2,200 m (7,200 ft) or more above sea level, highland lake basins and semiarid plains abut lower and lusher river valleys with adjacent wetlands (Figure 1). Storm systems originating from the coasts can be blocked by mountains in certain regions, resulting in rain shadows and more arid landscapes with precipitation well below the approximately 700 mm/year threshold that distinguishes moderate from high risk areas for rainfed maize agriculture. In others, central Mexico’s highly volcanic landscape resulted in badlands marginal for agriculture, ashy soils especially productive for agriculture, or easily mined rock deposits useful for making stone tools, including abundant obsidian sources. Indigenous peoples thereby confronted three communal resource management issues that stand out as critical for the development of urban society: 1) access to sufficient arable land; 2) access to sufficient water for agriculture, either via rain or irrigation; and 3) periodicities in economic systems created through the effects of high climatic variability, volcanic and tectonic activity, and cultural or historical fluctuations in exchange networks (McClung de Tapia 2012). All three played a role in structuring the possibilities and limitations that central Mexican individuals, groups, and polities faced in their strategies of risk mitigation.

FIGURE 1. Climatological map of central Mexico showing shaded climate zones, mean annual precipitation, and sites mentioned in the text. Data acquired from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI), Mexico.

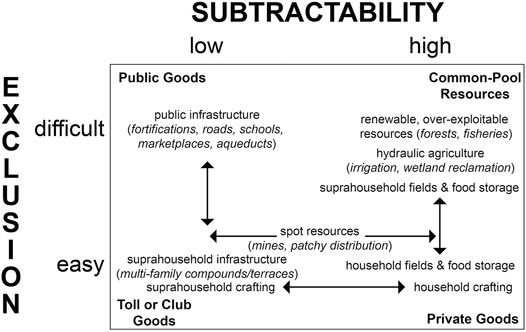

Using the language of collective-action theory (e.g., Ostrom 1990, 1992), irrigation systems within central Mexico’s semiarid environment constitute a common-pool resource involving zero-sum resources, as water going to one field comes at the expense of another’s. The possibility of exclusion of the resource can vary based on the ability to allocate water to particular fields, and not others, as well as how privately or collectively land was managed. Accordingly, the classifications of land, water, and other resources listed in the schematic diagram of Figure 2 should be taken as variable axes, indicated by the presence of bidirectional arrows, rather than immutably fixed types of resource dilemmas. The scale and organization of agricultural work exchanges were impacted by a diverse array of land management regimes, with corporate land tenure representing a well-documented component of precolonial and contemporary Indigenous communities (Hicks 1986: 48–50; Lockhart 1992: 142–149; Sarukhán and Larson 2001). The prevalence of land worked jointly by numerous households means that agricultural fields were often a shared resource as well, and were therefore not as excludable as land that would be classed as “private” in other societies (Offner 2016: 25–27). The sophisticated system of irrigated lakeshore fields called chinampas are known historically from the Aztecs and archaeologically to have originated a few centuries earlier, whereas systems of canal irrigation date some two millennia earlier in both semiarid and more humid regions (Spencer 2000; Nichols et al., 2006). Contrary to the expectations of Marxist inspired models of despotic resource management, there is little empirical support for the notion of centrally controlled irrigation in central Mexico (Offner 1981; Doolittle 1990). Networks of agricultural terraces are also pervasive in this mountainous landscape and likewise present resource dilemmas, which are characterizable as toll or club goods because of their easier exclusion of other users but need for suprahousehold coordination, since mismanagement by one family leads to the degradation in the terraces of their neighbors (Borejsza 2013; Pérez Rodríguez 2016). This backdrop of agricultural strategies, and lack of metal ploughs or animals to pull them, means that successful crop production involved the mobilization of human labor to create landesque capital (Nichols et al., 2006; Morehart 2016).

FIGURE 2. Classification of types of goods (based on Ostrom et al., 1994), with examples of variable axes relevant to precolonial central Mexico.

In the realm of economic goods, Blanton et al. (2005) identify a sequence of political-economic transitions over three millennia of precolonial Mesoamerican history: 1) early interregional exchange centered on prestige goods, particularly between social elites earlier in the Formative period (ca. 1200–500 BCE); 2) the maturation of economies of regional goods associated with a proliferation of urban centers and wide participation on the part of non-elites in the later Formative and Classic periods (ca. 500 BCE—700 CE); and 3) the creation of a macroregional system better integrated through markets that mobilized staples as well as bulk luxuries—finer goods that were widely available throughout the socioeconomic spectrum in the Postclassic period (ca. 1200–1519 CE). For central Mexico more specifically, the scheme should be amended to have the second transition end at around 600 CE, with the collapse of Teotihuacan and start of the Epiclassic period (ca. 600–900 CE). The period saw political balkanization and reconfiguration into smaller city-states featuring hybrid styles of art and architecture and attempts on the part of political elites to create the next Teotihuacan prior to the rise of the Aztec system, in a way analogous to European kingdoms following the collapse of Rome. I focus primarily on Classic through Postclassic governance in central Mexico, which span the regional-goods transformation culminating in Teotihuacan becoming the largest city in the Americas, balkanization and reconfiguration into smaller city-state polities, and the integration of the more commercialized “world” economy beginning with the Toltec capital of Tula and culminating in the Aztec empire.

As one of the key economic commodities of precolonial central Mexico, the trans-Mexican neovolcanic arc represents the largest and most spatially distributed obsidian flows on the globe to have been intensively exploited by humans (Cobean 2002). The obsidians and cherts used as weaponry and for basic food production in Mesoamerica were somewhat clustered on the landscape but were abundantly available and were impossible to completely monopolize (Hirth 2013). In general, central Mexican economies involved resources that were difficult to move in bulk long distances given the transportation infrastructure, so instead circulated through tax and market systems, usually representing internal revenue streams to state fiscal systems. This was particularly true for the regional-goods and macroregional-market transitions identified by Blanton et al. (2005). In a related vein, Mesoamerican warfare never featured the offensive or defensive arms race to match what occurred in Eurasia, such as through major changes in metallurgy and transportation technologies. Mesoamerican warfare generally involved stone weapons accessible to all, a complete lack of cavalry, and limited naval or siege tactics. Success was based on the ability to field more troops than an opponent through some mix of incentivizing through ideology and opportunities for social mobility, by taking captives on the battlefield for sacrifice at the temples of state capitals, and mandatory conscription through labor tax systems, rather than major technological advances in destructive capabilities (Cervera Obregón, 2017; Hassig 1992; Hassig 2016).

The diverse and multiethnic peoples of central Mexico acted strategically within this ecological and economic backdrop to organize labor, exchange networks, corporate groups, and fiscal systems undergirding polities in various ways. Yet, following the logic of deep-time political histories (e.g., Boix 2015), one might predict that barriers to elite control of key military and transportation technologies should have resulted on the whole in more collective or pluralistic polities. What does the historical record of the better documented later societies of central Mexico say?

Textual sources from 16th century central Mexico provide rich detail not available for earlier periods, but they must be read critically because they are replete with the biases of their Spanish, Indigenous, or Mestizo (mixed ancestry) authors. This is especially true for political organization, as Cortés and other conquistadors consistently looked to identify a single leader to deal with diplomatically, both because this was simpler than consulting with multiple individuals and because it better matched their monarchical vision of Castile and other European kingdoms. Contact period central Mexico contained a spectrum of political organization, but power-sharing arrangements are well documented, both as confederations of polities and systems of co-rule within a single polity (Daneels and Gutiérrez Mendoza 2012). Examples include the highly pluralistic system of Tlaxcala (ancient Tlaxcallan), a co-rule structure at Cholula (ancient Cholollan), the confederated altepemeh (city-states or small kingdoms) of the Triple Alliance (Aztec) empire, and the patron-client-like kingdoms of the Mixteca-Puebla and eastern Nahua (Nahuatl-speaking) spheres (Carrasco 1971; van Zantwijk 1985; Fargher et al., 2010, 2011b). Understanding this variability provides opportunities for evaluating under what structural and historical variables “good” governance arises—meaning more pluralistic decision making with greater accountability of principals—and the ways in which it can be undermined. It also helps to identify what archaeological signatures are most appropriate for considering the remains of early civilizations who lacked extensive textual documentation.

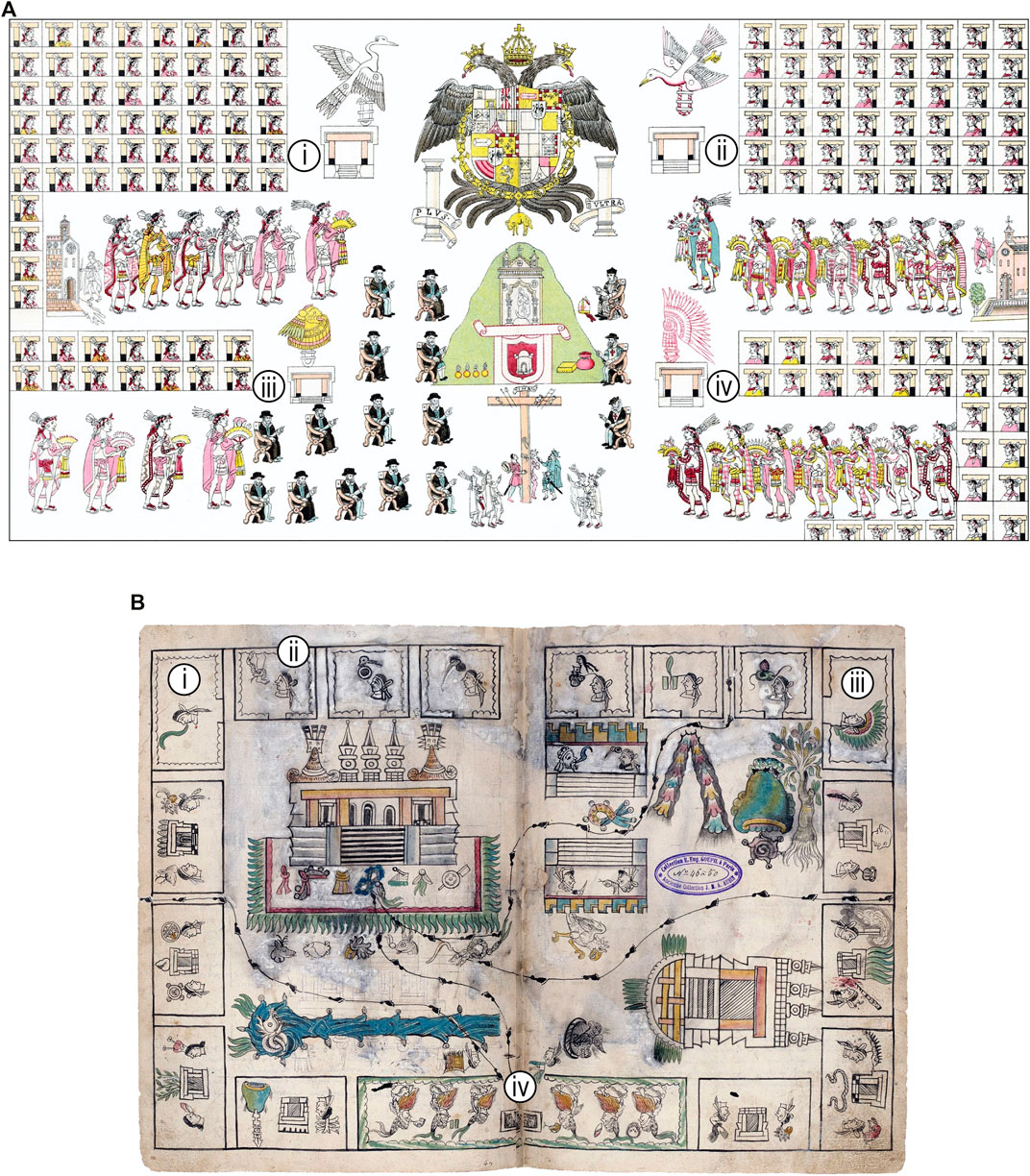

Tlaxcala presents the most pluralistic or even republican governance, with attributes including a distribution of executive power through rotating office holders, rule by a council that included some level of participation on the part of non-elites, and an absence of residences that could be termed palatial (Fargher et al., 2011a). Spanish conquistadors likened Tlaxcala to the Renaissance republics of northern Italy, with [Cortés (1986):68] writing in his second letter: “The orderly manner in which, until now, these people have been governed is almost like that of the states of Venice or Genoa or Pisa, for they have no overlord. There are many chiefs, all of whom reside in this city, and the country towns contain peasants who are vassals of these lords and each of whom holds his land independently; some have more than others, and for their wars they join together and together they plan and direct them.” In the colonial period, the Tlaxcaltecs presented themselves, in texts and pictorial documents such as the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, as a confederation between four nearby city-states: Tizatlan, Ocotululco, Tepeticpac, and Quiahuiztlan (Figure 3A). Texts authored by Spanish conquistadors single out Xicotencatl the elder, from Tizatlan, and Maxixcatzin, who represented the Ocotelulco faction of the confederation. Yet leading figures of other important factions in the governance structure are also named, including Temilotecutli of Tepeticpac and Chichimecatecle of Quiahuitzlan, and it is clear that within this pluralistic system decisions were made by a sizable ruling council that may have numbered in the low hundreds of representatives.

FIGURE 3. Depictions of political organization by Indigenous scribes in 16th century manuscripts: (A) depiction of colonial Tlaxcala from Lienzo de Tlaxcala with toponym of polity in center, Spaniards below, and confederated rulers of (i) Tizatlan, (ii) Ocotolulco, (iii) Tepeticpac, and (iv) Quiahuiztlan, with their large ruling councils; (B) depiction of precolonial Cholula from Historia Tolteca Chichimeca with temple to Quetzalcoatl at center left, calpultin (“big houses”) on border, paramount rulers and high priests the (i) Tlachiach and (ii) Aquiach, ruler of internal affairs the (iii) Chichimecatl teuctli, and (iv) noble council in the Turquoise House. Base images from Wikimedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/) and Bibliothèque Nationale de France (www.gallica.bnf.fr).

A variety of historically named figures were authorized as more prominent speakers in Tlaxcala but did not act as paramount rulers, and the four-part confederation seems a colonial period reconfiguration of what were previously wards or districts of a single, unified city (Fargher et al., 2010). The Tlaxcaltecs combined collective sociopolitical organization and active military resistance in fending off incorporation into the Aztec empire during the century prior to the arrival of the Spaniards. In a political system that permitted common people of non-noble rank to ascend to the ruling council, and which held its multiple rulers accountable in pursuing the collective good, the Tlaxcaltecs used pluralistic governance as a means of motivating their citizenry to defend against the external threat posed by the Mexica of Tenochtitlan in particular. The polity also forged strategic alliances with groups of ethnic Otomis who inhabited the north of Tlaxcala and remained independent from the empire, and for a while held a similar tripartite confederation with the city-states of Cholula and Huejotzingo, polities to the south whose relationships with Tlaxcala eventually soured prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, likely instigated by a pro-Aztec faction among Cholula’s elites (Plunket and Uruñuela 2017: 529–530).

Cholula represents a different model of governance from Tlaxcala (Lind 2012; Plunket and Uruñuela 2017, 2018: 199–237). It was not as pluralistic in the number of key decision-makers but featured a system of co-rulership and the election of principals by a governing council that Cortés equated to how the Great Council of Venice elected its doges. Similar councils were also present in polities such as Huejotzingo and Chalco but, unlike these other polities, Cholula possessed a high level of prestige within Mesoamerica as one of its longest-lived cities. Its origins as an urban center began in the first millennium BCE, but it was during the first millennium CE that the city’s inhabitants oversaw construction of the largest pyramidal-temple by volume in Mesoamerica (perhaps the world). At the time of the Spanish invasion Cholula played a pivotal role in Mexico as a market town and pilgrimage center dedicated to the god Quetzalcoatl. Because of this renown, rulers-elect of other central Mexican polities often traveled to Cholula for ceremonies of investiture.

Sixteenth-century documents provide details on Cholula’s urban and political organization, including a map richly illustrated by an Indigenous scribe from the Historia Tolteca Chichimeca (Figure 3B). Following Mesoamerican cartographic conventions, the city is oriented with East at top. Cholula’s urban epicenter is depicted with the largest structure representing the temple to Quetzalcoatl and the second largest representing the school for the children of nobles and certain non-elites training for the priesthood (the calmecac). A depiction of a grassy hill with a frog on top is a stylized representation of the Classic period Great Pyramid that had fallen into disuse by this time and therefore was not razed by the Spaniards in creating the colonial period city, as were Postclassic structures. The rectangular boxes surrounding the urban epicenter represent the city’s calpoltin (“big houses”), which were a fundamental social unit intermediate between households and the state in most central Mexican polities. Exceptions to this on the map are boxes highlighting the leadership structure of Cholula, including the two high priests who co-ruled the polity and were charged with external affairs—the Tlachiach and Aquiach—depicted at top left and in smaller temples on the map (Lind 2012: 103). Another ruler charged with internal affairs, the Chichimecatl teuctli, is depicted at top right, and a council of six nobles is illustrated at bottom in the council chamber known as the “Turquoise House” (Plunket and Uruñuela 2018: 114). These six are reported to have acted as legislators and judges and were responsible for electing the three rulers in consultation with the larger governing council. The more oligarchic nature of Cholula’s governance, relative to Tlaxcala, is apparent in the fact that the Tlalchiach and Aquiach could only be selected from among the nobility of a single calpolli of the city (Carrasco 1971: 372).

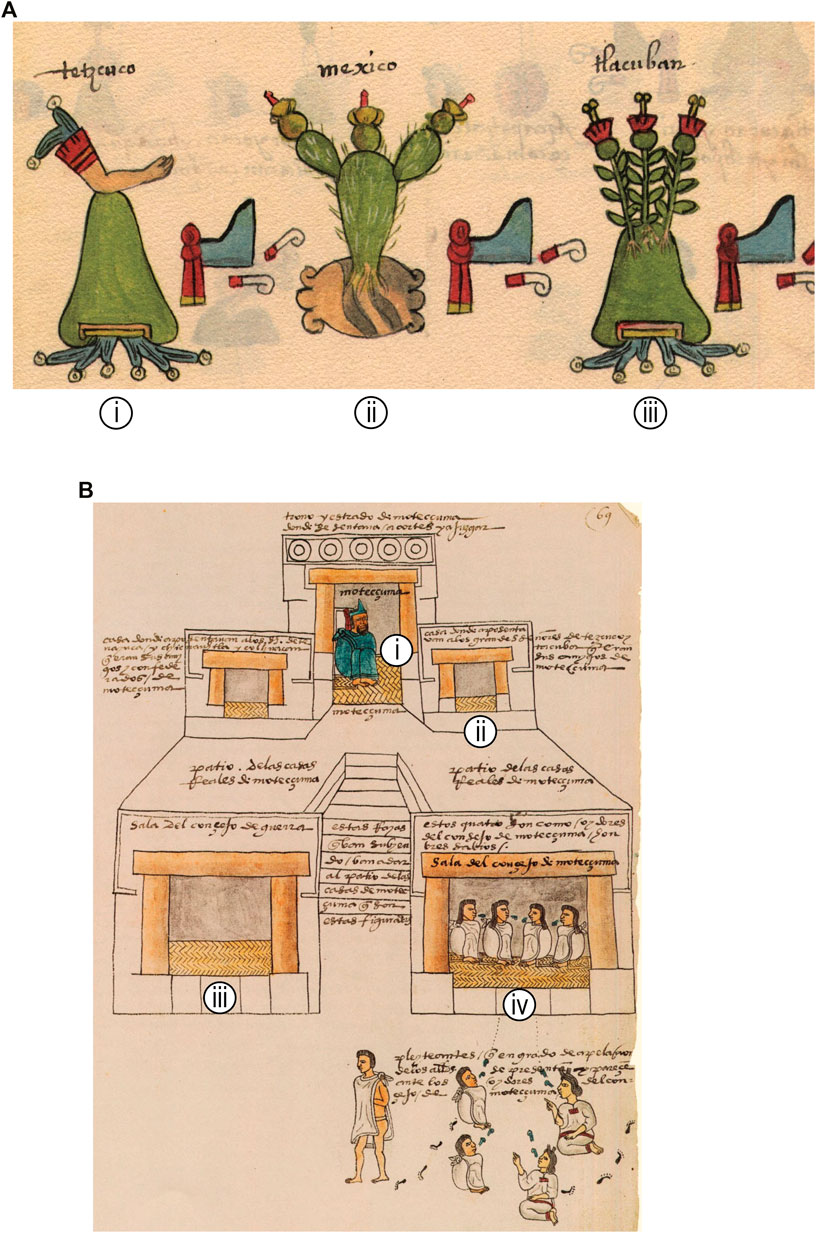

Although clearly not as pluralistic as Tlaxcala, Cholula, and some other historically documented central Mexican polities, the Mexica imperial capital of Tenochtitlan nevertheless presents a mix of pluralistic and absolutist attributes. The Triple Alliance leadership structure involved a confederation between Tenochtitlan, the Acolhua city-state of Tetzcoco (modern Texcoco), and the Tepanec city-state of Tlacopan (modern Tacuba), though Tenochtitlan was clearly the dominant polity of the three (Figure 4A). Viewed in comparative perspective, such alliances, confederations, or leagues represent one pathway for the scaling-up of city-state systems to imperial polities, like was the case with the Athenian empire of the fifth century BCE (Scheidel 2019: 54–55). This pathway tended to result in more indirect governance strategies than the imperial pathway that emphasized more direct means of territorial control (Trigger 2003; Smith 2017). In the case of Tenochtitlan, its paramount ruler (the huey tlatoani or “great speaker”) was chosen based on the consensus of a noble council regarding their suitability for the office, rather than directly succeeding through primogeniture (Blanton and Fargher 2008: 246–248; Fargher et al., 2017; van Zantwijk 1985: 25–26, 178–179, 277–281). The office more frequently moved between brothers or uncles and nephews rather than father to son. Throughout its history, Tenochca society did not feature divine kingship analogous to that institution in pharaonic Egypt, the Inca empire, or the Classic period Maya, though the ruler who fatefully invited Cortés and his Tlaxcaltec allies into the city, Moctezuma, did advertise the divine sanctioning of his rule more forcefully than his predecessors (López Luján and Olivier 2009). Tenochtitlan’s governance structure included secondary leaders who wielded significant power—such as the cihuacoatl, charged with internal affairs—and offered several opportunities for the social promotion of lower nobles and even commoners.

FIGURE 4. Depictions of political organization by Indigenous scribes in 16th century manuscripts: (A) toponyms and great speakers (note turquoise diadems with speech scrolls) of the Triple Alliance between (i) Tetzcoco, (ii) Mexico-Tenochtitlan, and (iii) Tlacopan, constituting the Aztec empire, from Codex Osuna; (bottom)(B) depiction of Moctezuma’s palace from Codex Mendoza showing (i) throne room, (ii) lodgings for visiting dignitaries, (iii) Council Hall of War, and (iv) Moctezuma’s Council Hall. Base images from Biblioteca Nacional de España (www.bne.es) and Wikimedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/).

The fact that Tenochtitlan became Mexico City and the capital of the viceroyalty of New Spain makes the Aztec empire the best documented precolonial Indigenous polity of the Americas, though scholars continue to debate the exact nature of political organization and governance (Berdan and Anawalt, 1997; Rojas 2016; Fargher et al., 2017). An illustration of Moctezuma’s palace in the Codex Mendoza combines an image with alphabetic glosses in Spanish and encapsulates some key attributes of governance at Tenochtitlan (Figure 4B). At the top is the “throne and dais of Motecuhzoma where he sat in audience and to judge” [Berdan and Anawalt 1997: 222–225; see also Offner et al. (2016): 15–17)]. The middle tier depicts quarters for housing visiting leaders of other altepemeh of the Triple Alliance as well as other allies on diplomatic visits. The lower tier depicts a “Council Hall of War” for higher ranked warriors at left and “Motecuhzoma’s Council Hall” at right. The council hall illustration shows four judges sitting in deliberation on appeals originating in commoners’ court with four litigants pleading their cases depicted below. Rooms of the palace not depicted but known from other sources include the Achcuahcalli (“House of Constables”), store-rooms for staple and luxury goods, a jail, and quarters for the palace overseer as well as singers and dancers. In short, the image captures the courtly life of a palace at the apex of Aztec society that was certainly hierarchically organized yet also featured checks on principals and degrees of pluralistic decision-making available to noble councilmembers and high-ranking military officials.

Political organization in later central Mexican societies presents the variable hierarchical and heterarchical arrangements reviewed above but also similarities, since fundamental societal relations that structured fiscal financing and governance were grounded in systems of collective labor and rotary labor tax, largely representing internal revenue streams. The important axis of variability within these later central Mexican societies was the strength of the more collective suprahousehold social units comprised primarily of non-elites, the calpolli and tlaxilacalli, relative to the more exclusionary, noble and palace-based systems, the teccalli, in any given altepetl, and how this balance in societal organization impacted political financing and the labor relations underlying systems of governance (Martínez 2001; Gutiérrez Mendoza 2012; López Corral and Hirth 2012; Johnson 2017). The 16th century chronicler Alonso de Zorita (1963: 203) provided a rosy perspective of collective labor for public works or other forms of community service in Aztec society:

“In the old days they performed their communal labor in their own towns … They did their work together and with much merriment, for they are people who do little work alone, but together they accomplish something … The building of the temples and the houses of the lords and public works was always a common undertaking, and many people worked together with much merriment.”

We should be skeptical that communal labor was always undertaken with “much merriment,” but it was clearly prioritized through a combination of informal social institutions and formal bureaucratic structures capable of mobilizing tax in labor and goods (Carballo, 2013; Rojas Rabiela, 1979; Smith 2015). Even human sacrifice, that most overtly coercive ritual practice of central Mexico, could be said to have formed part of the hegemonic discourse of collective work, in that the rarer sacrifice of citizens involved honoring them as productive, responsible, or even godly, while the more common sacrifice of non-citizen war captives and culturally debased slaves set them apart as non-productive members of society (Kurtz and Nunley 1993). The emphasis on internally derived fiscal financing through collective draft labor and staple goods made even the more hierarchical and imperialistic governance of the Aztec empire land more on the collective side of the comparative spectrum, particularly in regards to distribution of public goods and means of controlling principals (Blanton and Fargher 2008); yet that polity was clearly less pluralistic than the smaller, contemporary states of Tlaxcala, Cholula, and a few others of the period. What of earlier central Mexican societies for whom we possess no written records or relatively brief hieroglyphic texts used to primarily record calendrical cycles, place-names, and titles of office?

In seeking to understand the deeper history of political organization and governance in central Mexico, archaeologists look to material correlates of the later, better documented cases. Architectural variability observed in Postclassic central Mexico suggests a direct correlation between more absolutist rule and the centrality of palaces (teccalli), with palaces often having been of equal or greater size than temples in cities of the Mixteca-Puebla sphere; present, but of a smaller scale than temples at Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Cholula; and minimized or absent in Tlaxcala. Similarly, the mortuary deposits of likely rulers thus far discovered are most elaborate in the Mixteca-Puebla sphere; potentially very elaborate, but involving cremation of the body in the possible case of the penultimate preconquest ruler of Tenochtitlan, Ahuitzotl (López Luján and Balderas, 2010); and absent in Tlaxcala. Precolonial depictions of rulers were present for Tenochtitlan, though decidedly secondary to religious imagery, and are thus far unknown for Tlaxcala. Finally, the distribution of goods and resources, whether part of the built environment of urban centers or artifact distributions among households and mortuary contexts, can be used to gauge key sources of fiscal financing, the organization of labor, and public-goods distribution. Such architectural, artefactual, mortuary, and iconographic variables provide lines of evidence in reconstructions of political organization among earlier central Mexican societies.

As was the case in later central Mexican societies, those of the first millennium BCE through first millennium CE exhibit material correlates consistent with variability in strategies of governance and how these articulated with religious systems and politicized ritual spectacles (Carballo 2016). In general, the initial pulse of urbanization into the region’s first towns and cities during the later Formative period and a second pulse that saw the rise of Classic period cities—such as Teotihuacan, Cholula, and Cantona—archaeologically looks to have involved processes of social integration and the formation of more collective polities. It is during this period that Blanton et al. (2005) identify a regional goods transformation, when utilitarian economies became more robust and more equitably distributed among households of non-elites. Classic period cities, Teotihuacan and Cholula in particular, also grew as the result of rapid migration associated with volcanic activity in the southern Basin of Mexico. Urbanization and state formation therefore necessitated the integration of multiethnic populations, and this appears to have been accomplished through political ideologies that emphasized shared interests such as rain in a semiarid environment, agricultural fertility, cosmic renewal, military success, and generalized social roles rather than powerful dynasts or lineages.

During the first half of the first millennium CE, Teotihuacan became the most populous city of the Americas, with over 100,000 inhabitants, and the most powerful polity in Mesoamerica. Its political organization remains a point of contention among specialists, but most agree that the city and polity it controlled were characterized to a significant degree by collective institutions and political ideology (Carballo 2020b). Teotihuacan was in no way an egalitarian society and signs of social hierarchy are readily apparent in the size and elaboration of households, the distribution of mortuary furnishings, and the attire and hieroglyphic titles of office seen in the city’s rich tradition of mural art. Nevertheless, specialists have characterized Teotihuacano governance as analogous to an oligarch republic, similar to the comparisons drawn by Spaniards for Tlaxcala and Cholula (Cowgill, 1997; Millon 1976), or perhaps organized as a quadripartite system of co-rule (Manzanilla 2002), somewhat analogous to how the Tlaxcaltecs presented their polity in the colonial period. When scholars propose the alternate interpretation, that political organization at Teotihuacan was autocratic or despotic, they rely on simplistic notions not grounded in any comparative understanding of political history, such as a city-wide grid plan (Figure 5A), large public monuments, or a political ideology valorizing success in battle as the basis of their interpretations (see review in Carballo (2020b)). These authors are apparently unaware that all three could characterize the democratic or oligarchic polis of Classical Greece or the Roman Republic (Moragas Segura 2012). This debate also tends to lack any sense of the possibility of diachronic change, as if Teotihuacan and other Indigenous polities were locked into one form of political organization for centuries, even though we know of historical change in later polities of Mesoamerica, the Mediterranean world, and elsewhere.

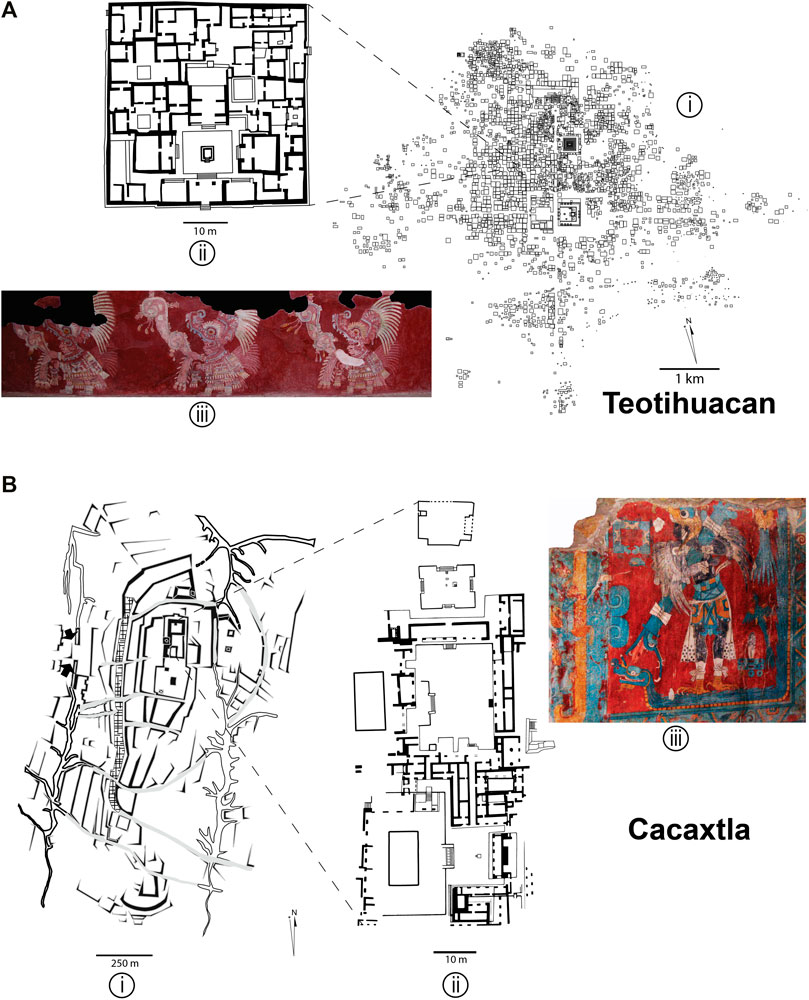

FIGURE 5. Art and architecture from pre-Aztec polities: (A) Classic period Teotihuacan, showing (i) orthogonal urban plan, (ii) plan of the Yayahuala apartment compound, and (iii) mural of processing priests from Tepantitla; (B) Epiclassic period Cacaxtla, showing (i) acropolis-like urban plan, (ii) plan of palatial compound at its summit, and (iii) mural of figure in eagle outfit from doorway in northeast of palace. Photos and illustrations by David Carballo.

Although Teotihuacan is often cited in world archaeology for the scale of its monuments and orthogonal, grid-like urban plan, its most noteworthy attribute was its housing. Teotihuacan may represent the only premodern city of its size where multi-family apartment living was the dominant residential arrangement, and over ninety percent of the city’s occupants appear to have resided in relatively spacious and nicely made apartment compounds (Smith et al., 2019). Apartment living meant that repeat interactions were built into the fabric of daily life, and the intense craft production that appears to have taken place in most excavated compounds suggests that scalar economies were as well. Apartment compounds were grouped into urban neighborhoods and districts featuring the social infrastructure of shared plazas, temples, and other civic spaces (Gómez Chávez 2012; Manzanilla 2015; Carballo et al., 2021). The art of Teotihuacan does not offer any clear depictions of paramount rulers, though this negative evidence does not mean they did not exist for intervals of the polity’s centuries-long existence (Carballo 2020b). It does mean, however, that political power was depicted more abstractly, with reference to notions of the social roles of individuals in keeping the cosmos going and the polity strong.

Following Teotihuacan’s political collapse in the mid to late sixth century, several smaller polities developed in the city’s former realm of hegemony, including Cacaxtla to the southeast and Xochicalco to the southwest. They exhibit hybrid styles of art and architecture suggestive of a period of political experimentation in vying for what the most powerful successor state would be. Cacaxtla has been relatively well studied archaeologically and iconographically, particularly its elaborate murals (Brittenham 2015). As a political capital, Cacaxtla was considerably smaller than Teotihuacan, with an estimated population between 15,000–20,000, and contrasts in the urban organization of the two cities are immediately apparent, such as the major urban construction at Cacaxtla being a restricted access acropolis that served palatial and civic-ceremonial functions (Serra Puche and Lazcano Arce 2003). Comparison of the two plans in Figure 5 highlights the fact that this palatial compound was only somewhat larger than an average-sized apartment compound at Teotihuacan.

Cacaxtla’s vivid murals are painted in a style that is more individualistic in their portrayal of humans than was the case in the mural tradition at Teotihuacan. They likely represent a fusion of central Mexican styles with those from the Gulf of Mexico and Maya lowlands, which both had thriving city-states at this time of balkanization in central Mexico (Brittenham 2015). The three largest murals preserved today depict a battle scene, two individuals richly garbed in eagle and jaguar outfits (Figure 5B), and the Maya god of traders carrying a pack of exotic goods from the lowlands, including the prized feathers of the quetzal bird. While it is not clear if any of the depictions may be of a ruler, their individualized attributes represent a departure from the artistic cannon at Teotihuacan. Economic indicators also suggest different fiscal streams undergirding the polity that Cacaxtla controlled. Large granaries found in the base of the acropolis are suggestive of elite consolidation of staple foods, and long-distance trade items, such as jade from Guatemala and turquoise from the Southwestern US, could indicate more of an elite control of trade in prestigious spot resources (Serra Puche and Lazcano Arce 2003:153–156). Although new finds could change our view of political organization in these two cities, the comparison serves to illustrate how archaeologists reconstruct political organization through material remains and triangulate between those remains and texts from the culture area in concluding, for instance, that Cacaxtla was more palatially and elite-network focused than Teotihuacan. The art, architecture, and artifact distributions of the two cities are indicative of polities with differing fiscal underpinnings, rulership structures, and allocation of public goods.

Through this overview of political organization and governance in precolonial central Mexico I hope to have underscored how the Indigenous peoples of this part of the world developed a spectrum of strategies within the constraints and possibilities offered by time and place. The ecological and economic realities they faced meant that key resources were often more difficult for aspiring political elites to control than in many other world regions that saw premodern state formation. In comparative perspective, such resources in central Mexico were more frequently managed as common-pool resources reliant on collective labor and, when mobilized by political economies, more often constituted internal fiscal streams. Nevertheless, variability in governance is observable both synchronically and diachronically.

On the eve of Cortés’ invasion, textual accounts make clear that the wider Aztec world featured an empire made through the confederation of city-states, other polities with co-rule structures and powerful governing councils such as Cholula, and the most pluralistic, republican form of governance at the imperial rival state of Tlaxcala. Similar variability can be gleaned through archaeological remains in the millennium or so leading up to these societies, indicative of more pluralistic governance at the pre-Aztec metropolis of Teotihuacan and a more exclusionary or patron-client system at the subsequent city-state of Cacaxtla. The region therefore offers compelling cases for examining the conditions within which more pluralistic governance norms and more accountable bureaucratic institutions arise or are suppressed by political elites. They expand the range of non-Western cases that should be part of comparative scholarship on political history.

Reconstructions of premodern polities with little or no textual documentation draw especially on archaeology and iconography and lack the additional support offered by texts but expand the size of the comparative sample pool exponentially. They would greatly benefit from multidisciplinary collaborations between archaeologists and political scientists or other comparatively oriented social scientists. Archaeologists contribute the explanatory power of a materialist lens prioritizing variables of human-environment interactions and the material correlates of political legitimation, governance structures, corporate groups, collective labor, and fiscal streams. In turn, archaeological discourse about politics in the deep past tend to be siloed and would benefit from engagement with more transdisciplinary and comparative studies of political evolution and variability in political organization. Greater interdisciplinary collaborations between would strengthen our models of systems of governance and work towards identifying how humans have created more pluralistic and accountable governance before and how it can best be nurtured and sustained today.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Investigations at Teotihuacan mentioned in this article were made possible by funding from the National Science Foundation (BCS-1321247) and the H. and T. King Grant for Precolumbian Archaeology of the Society of American Archaeology.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

DC thanks Steve Kowalewski, Gary Feinman, Aurelio López Corral, Jennifer Carballo, and two reviewers for their constructive feedback on themes in, and an earlier draft of, this paper.

Acemoglu, D., and Robinson, J. A. (2013). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. New York: Crown Business.

Berdan, F. F., and Anawalt, P. R. (1997). The Essential Codex Mendoza. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Blanton, R. E., Fargher, L. F., Feinman, G. M., and Kowalewski, S. A. (2021). The Fiscal Economy of Good Government. Curr. Anthropol. 62 (1), 77–100. doi:10.1086/713286

Blanton, R. E., Feinman, G. M., Kowalewski, S. A., and Fargher, L. F. (2020). Moral Collapse and State Failure: A View from the Past. Front. Polit. Sci. 2, 568704. doi:10.3389/fpos.2020.568704

Blanton, R. E., Fargher, L. F., and Espinoza, V. Y. H. (2005). “The Mesoamerican World of Goods and its Transformations,” in Settlement, Subsistence, and Social Complexity: Essays Honoring the Legacy of Jeffrey R. Parsons. Editor R. E. Blanton (Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California), 260–294.

Blanton, R., and Fargher, L. (2008). Collective Action in the Formation of Pre-modern States. New York: Springer.

Boix, C. (2015). Political Order and Inequality: Their Foundations and Their Consequences for Human Welfare. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Borejsza, A. (2013). Village and Field Abandonment in Post-Conquest Tlaxcala: A Geoarchaeological Perspective. Anthropocene 3, 9–23. doi:10.1016/j.ancene.2014.02.001

Brittenham, C. (2015). The Murals of Cacaxtla: The Power of Painting in Ancient Central Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Carballo, D. M. (2013). “Labor Collectives and Group Cooperation in Pre-hispanic Central Mexico,” in Cooperation and Collective Action: Archaeological Perspectives. Editor D. M. Carballo (Boulder: University Press of Colorado), 243–274.

Carballo, D. M. (2016). Urbanization and Religion in Ancient Central Mexico. New York: Oxford University Press.

Carballo, D. M. (2020a). Collision of Worlds: A Deep History of the Fall of Aztec Mexico and the Forging of New Spain. New York: Oxford University Press.

Carballo, D. M. (2020b). “Power, Politics, and Governance at Teotihuacan,” in Teotihuacan: The World beyond the City. Editors K. G. Hirth, D. M. Carballo, and B. Arroyo (Washington, D.C: Dumbarton Oaks and Trustees of Harvard University), 57–96.

Carballo, D. M., Barba, L., Ortiz, A., Blancas, J., Hernández Sariñana, D., Codlin, M. C., et al. (2021). Excavations at the Southern Neighborhood Center of the Tlajinga District, Teotihuacan, Mexico. Latin Am. Antiq. 32 (3), 557–576. doi:10.1017/laq.2021.17

Carrasco, P. (1971). “14. Social Organization of Ancient Mexico,” in Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 10: Archaeology of Northern Mesoamerica, Part 1. Editors G. F. Ekholm, and I. Bernal (Austin: University of Texas Press), 349–375. doi:10.7560/701502-014

Cervera Obregón, M. A. (2017). “Mexica War: New Research Perspectives,” in Oxford Handbook of the AztecsDeborah L. Nichols and Enrique Rodríguez-Alegría (New York: Oxford University Press), 451–462.

Cobean, R. H. (2002). A World of Obsidian: The Mining and Trade of a Volcanic Glass in Ancient Mexico. Pittsburgh and Mexico City: University of Pittsburgh and INAH.

Cortés, H. (1986). Letters from Mexico. Edited and Translated by Anthony Pagden. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Cowgill, G. L. (1997). State and Society at Teotihuacan. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 26, 126–161. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.26.1.129

Daneels, A., and Gutiérrez Mendoza, G. (Editors) (2012). El poder compartido: ensayos sobre la arqueología de organizaciones políticas segmentarias y oligárquicas (Mexico City: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social and El Colegio de Michoacán).

Doolittle, W. E. (1990). Canal Irrigation in Prehistoric Mexico: The Sequence of Technological Change. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., and Espinoza, V. Y. H. (2010). Egalitarian Ideology and Political Power in Prehispanic Central Mexico: The Case of Tlaxcallan. Latin Am. Antiq. 21 (3), 227–251. doi:10.7183/1045-6635.21.3.227

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., Espinoza, V. Y. H., Millhauser, J., Xiuhtecutli, N., and Overholtzer, L. (2011a). Tlaxcallan: The Archaeology of an Ancient Republic in the New World. Antiquity 85, 172–186. doi:10.1017/s0003598x0006751x

Fargher, L. F., Heredia Espinoza, V. Y., and Blanton, R. E. (2011b). Alternative Pathways to Power in Late Postclassic Highland Mesoamerica. J. Anthropological Archaeology 30, 306–326. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2011.06.001

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., and Espinoza, V. Y. H. (2017). “Aztec State-Making, Politics, and Empires: The Triple Alliance,” in Oxford Handbook of the Aztecs. Editors D. L. Nichols, and E. Rodríguez-Alegría (New York: Oxford University Press), 143–160.

Feinman, G. M., and Carballo, D. M. (2018). Collaborative and Competitive Strategies in the Variability and Resiliency of Large-Scale Societies in Mesoamerica. Econ. Anthropol. 5 (1), 7–19. doi:10.1002/sea2.12098

Gómez Chávez, S. (2012). “Structure and Organization of Neighborhoods in the Ancient City of Teotihuacan,” in The Neighborhood as a Social and Spatial Unit in Mesoamerican Cities. Editors M. Charlotte Arnauld, L. R. Manzanilla, and M. E. Smith (Tucson: University of Arizona Press), 74–101.

Gutiérrez Mendoza, G. (2012). “Hacia un modelo general para entender la estructura político-territorial del Estado nativo mesoamericano (altepetl),” in El poder compartido: ensayos sobre la arqueología de organizaciones políticas segmentarias y oligárquicas. Editors A. Daneels, and G. Gutiérrez Mendoza (Mexico City: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social and El Colegio de Michoacán), 27–67.

Hassig, R. (1992). War and Society in Ancient Mesoamerica. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hicks, F. (1986). “3. Prehispanic Background of Colonial Political and Economic Organization in Central Mexico,” in Supplement to the Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 4, Ethnohistory. Editors V. Reifler Bricker, and R. Spores (Austin: University of Texas Press), 35–54. doi:10.7560/776043-004

Hirth, K. G. (2013). “The Merchant’s World: Commercial Diversity and the Economics of Interregional Exchange in Highland Mesoamerica,” in Merchants, Markets, and Exchange in the Pre-columbian World. Editors K. G. Hirth, and J. Pillsbury (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks and Trustees for Harvard University), 85–112.

Johansen, B. E. (1996). Native American Political Systems and the Evolution of Democracy: An Annotated Bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Johnson, B. D. (2017). Pueblos within Pueblos: Tlaxilacalli Communities in Acolhuacan, Mexico, Ca. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 1272–1692.

Kohler, T. A., and Smith, M. E. (Editors) (2018). Ten Thousand Years of Inequality: The Archaeology of Wealth Differences (Tucson: University of Arizona Press).

Kohler, T. A., Smith, M. E., Bogaard, A., Feinman, G. M., Peterson, C. E., Betzenhauser, A., et al. (2017). Greater Post-Neolithic Wealth Disparities in Eurasia Than in North America and Mesoamerica. Nature 551 (7682), 619–622. doi:10.1038/nature24646

Kurtz, D. V., and Nunley, M. C. (1993). Ideology and Work at Teotihuacan: A Hermeneutic Interpretation. Man 28 (4), 761–778. doi:10.2307/2803996

Lind, M. (2012). “La estructura político-territorial del altépetl de Cholula,” in El poder compartido: ensayos sobre la arqueología de organizaciones políticas segmentarias y oligárquicas. Editors A. Daneels, and G. Gutiérrez Mendoza (Mexico City: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social and El Colegio de Michoacán), 99–113.

Lockhart, J. (1992). The Nahuas after the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth through Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

López Corral, A., and Hirth, K. G. (2012). Terrazguero Smallholders and the Function of Agricultural Tribute in Sixteenth-Century Tepeaca, Mexico. Mexican Stud./Estudios Mexicanos 28 (1), 73–93.

López Luján, L., and Balderas, X. C. (2010). “Al pie del Templo Mayor: excavaciones en busca de los soberanos mexicas,” in Moctezuma II: Tiempo y Destino de un Gobernante. Editors L. L. Luján, and C. McEwan (Mexcio City: INAH), 294–303.

López Luján, L., and Olivier, G. (2009). La estera y el trono: Los símbolos de poder de Motecuhzoma II. Arqueología Mexicana 98, 38–44.

Manzanilla, L. R. (2002). “Organización sociopolítica de Teotihuacan: lo que los materiales arqueológicos nos dicen o nos callan,” in Ideología y política a través de materiales, imágenes y símbolos. Memoria de la Primera Mesa Redonda de Teotihuacan. Editor M. E. R. Gallut (Mexico City: CONACULTA/INAH), 3–21.

Manzanilla, L. R. (2015). Cooperation and Tensions in Multiethnic Corporate Societies Using Teotihuacan, Central Mexico, as a Case Study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 9210–9215. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419881112

Martínez, H. (2001). “Calpulli ¿Otra acepción de teccalli,” in Estructuras y formas agrarias en México: del pasado y del presente. Editors A. E. Ohmstede, and T. R. Rabiela (Mexico City: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social), 25–44.

McClung de Tapia, E. (2012). “Silent Hazards, Invisible Risks: Prehispanic Erosion in the Teotihuacan Valley, Central Mexico,” in Surviving Sudden Environmental Change: Answers from Archaeology. Editors J. Cooper, and P. Sheets (Boulder: University Press of Colorado), 143–165.

Millon, R. (1976). “Social Relations in Ancient Teotihuacan,” in The Valley of Mexico: Studies in Pre-hispanic Ecology and Society. Editor E. R. Wolf (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press), 205–248.

Moragas Segura, N. (2012). “Modelo de organización compartida en el Mediterráneo: viejos modelos para nuevas ideas sobre el gobierno corporativo en Teotihuacan,” in El poder compartido: ensayos sobre la arqueología de organizaciones políticas segmentarias y oligárquicas. Editors A. Daneels, and G. G. Mendoza (Mexico City: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social and El Colegio de Michoacán), 333–348.

Morehart, C. T. (2016). Let the Earth Forever Remain! Landscape Legacies and the Materiality of History in the Northern Basin of Mexico. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 22 (4), 939–961. doi:10.1111/1467-9655.12498

Morris, I. (2010). Why the West Rules—For Now: The Patterns of History, and what They Reveal about the Future. New York: Picador.

Morris, I. (1989). Circulation, Deposition and the Formation of the Greek Iron Age. Man 24 (3), 502–519. doi:10.2307/2802704

Nichols, D. L., Frederick, C. D., Morett Alatorre, L., and Sánchez Martínez, F. (2006). “Water Management and Political Economy in Formative Period Central Mexico,” in Precolumbian Water Management: Ideology, Ritual, and Power. Editors L. J. Lucero, and B. W. Fash (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press), 51–66.

Offner, J. A. (1981). On the Inapplicability of "Oriental Despotism" and the "Asiatic Mode of Production" to the Aztecs of Texcoco. Am. Antiq. 46, 43–61. doi:10.2307/279985

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, E. (1992). Crafting Institutions for Self-Governing Irrigation Systems. San Francisco: Institute for Contemporary Studies Press.

Ostrom, E., Gardner, R., and Walker, J. M. (1994). Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Pérez Rodríguez, V. (2016). Terrace Agriculture in the Mixteca Alta Region, Oaxaca, Mexico: Ethnographic and Archeological Insights on Terrace Construction and Labor Organization. Cult. Agric. Food Environ. 38 (1), 18–27.

Plunket, P., and Uruñuela, G. (2018). Cholula. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica and Colegio de México.

Plunket, P., and Uruñuela, G. (2017). “Cholula in Aztec Times,” in Oxford Handbook of the Aztecs. Editors D. L. Nichols, and E. Rodríguez-Alegría (New York: Oxford University Press), 523–534.

Rojas Rabiela, T. (1979). “La organización del trabajo para las obras públicas: el coatequitl y las cuadrillas de trabajadores,” in El trabajo y los trabajadores en la historia de México. Editors E. C. Frost, M. C. Meyer, and J. Z. Vázquez (Mexico City and Tucson: El Colegio de México and University of Arizona Press), 41–66.

Sanders, W. T. (1956). The Cultural Ecology of the Teotihuacan Valley. Pennsylvania: Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park.

Sarukhán, J., and Larson, J. (2001). “When the Commons Become Less Tragic: Land Tenure, Social Organization, and Fair Trade in Mexico,” in Protecting the Commons: A Framework for Resource Management in the Americas. Editors J. Burger, E. Ostrom, R. B. Norgaard, D. Policansky, and B. D. Goldstein (Washington, D.C: Island Press), 45–70.

Scheidel, W. (2019). Escape from Rome: The Failure of Empire and the Road to Prosperity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University.

Serra Puche, M. C., and Lazcano Arce, J. C. (2003). “Urban Configuration at Cacaxtla-Xochitecatl,” in Urbanism in Mesoamerica. Editors A. G. Mastache, R. Cobean, Á. G. Cook, and K. G. Hirth (Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia and Pennsylvania State University, Mexico City and State College), Vol. 2, 133–164.

Smith, M. E., ChatterjeeHuster, A., Huster, A. C., Stewart, S., and Forest, M. (2019). Apartment Compounds, Households, and Population in the Ancient City of Teotihuacan, Mexico. Ancient Mesoam 30 (3), 399–418. doi:10.1017/s0956536118000573

Smith, M. E. (2017). Bounding Empires and Political/Military Networks Using Archaeological Data. J. Globalization Stud. 8 (1), 30–47.

Smith, M. E. (2015). “The Aztec Empire,” in Fiscal Regimes and the Political Economy of Premodern States. Editors A. Monson, and W. Scheidel (New York: Cambridge University Press), 71–114.

Spencer, C. S. (2000). “Prehispanic Water Management and Agricultural Intensification in Mexico and Venezuela: Implications for Contemporary Ecological Planning,” in Imperfect Balance: Landscape Transformations in the Precolumbian Americas. Editor D. L. Lentz (New York: Columbia University Press).

Trigger, B. G. (2003). Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Study. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Turchin, P., Hoyer, D., Korotayev, A., Kradin, N., Nefedov, S., Feinman, G., et al. (2021). Rise of the War Machines: Charting the Evolution of Military Technologies from the Neolithic to the Industrial Revolution. PLoS ONE 16 (10), e0258161. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258161

van Zantwijk, R. (1985). The Aztec Arrangement: The Social History of Pre-Spanish Mexico. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Keywords: political organization, collective action, pluralistic governance, common-pool resources, archaeology, Aztecs, Mesoamerica

Citation: Carballo DM (2022) Governance Strategies in Precolonial Central Mexico. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:797331. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.797331

Received: 18 October 2021; Accepted: 04 January 2022;

Published: 03 February 2022.

Edited by:

Stephen A. Kowalewski, University of Georgia, United StatesReviewed by:

Jerome Offner, Houston Museum of Natural Science, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Carballo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David M. Carballo, Y2FyYmFsbG9AYnUuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.