95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 17 June 2022

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.790575

This article is part of the Research Topic Beyond the Secret Garden of Politics: Internal Party Dynamics of Candidate Selection View all 8 articles

The article explores recent changes in the Italian parliamentary elite thanks to a novel set of data on Italian MPs between 1946 and 2018. After a first discussion on some crucial long-term trends of Italian Lower House MPs (their turnover rate, seniority, gender balance, party-related or institutional experience), we focus on the possible explanations of the profound transformation that occurred in the past decade: the rise of new party actors, the realignment between citizens and the parliamentary elites, or the use of different electoral systems. Subsequently, we point at three MP categories, taken as the most relevant proxies of the innovations in the Italian parliamentary elite. These categories are based on the length of MPs' parliamentary career, their previous party or institutional experience, and their gender. We discuss the changing numerical relevance of these categories, their parliamentary career patterns, and some features related to the institutionalization of MPs belonging to such categories. Two implications clearly emerge from our analysis. First, the changes occurred in the so-called “decade of the crises” (after the 2013 and 2018 Italian general elections) are critical in terms of a new influx of political amateur, female, and young MPs. The magnitude of this renewal can hardly be compared to any other relevant turning point of the Italian republican age and might signal the existence of a pattern of “impossible stability” for the parliamentary elite. Second, and partly in contrast with the first implication, despite such changes, the perspectives of parliamentary career and parliamentary survival remain very much subordinated to belonging to strong parliamentary party groups. This signals that, despite broad discussions about the positive role exerted by new political actors and the demand for a stronger descriptive representation, what seems to matter in the Italian Lower House is the presence of powerful political parties.

This article discusses long-term transformations of political elites in Italy, thanks to an original set of data, including information on profiles and careers of the Italian parliamentary elite since the early days of the Italian Republic (1946). Such a systematic analysis recalls the tradition of comparative studies on political elites (Parry, 1969; Putnam, 1976) that found a fertile ground also among Italian scholars. In this country, it was the study by Sartori and Somogyi (1963) that started a wave of empirical research on parliamentary elites, opening the discussion about the professional qualities of a compound ruling class representing several parties and a fragmented society. Two following generations of scholars (e.g., see Farneti, 1978; Cotta, 1979; Cotta et al., 2000) discussed the relevance of the (different) models of party selection and elite circulation in explaining the stability of the political system in the second half of twentieth century in Italy.

An update of such classical works looks on time after 75 years of uninterrupted democratic representation in Italy. The central goal of the article is two-fold. First, assessing the changes within the Italian parliamentary elite in the context of broader phenomena of malaise and instability of democratic representation (Mair, 2013; Roberts, 2017; Karremans and Lefkofridi, 2020); second, comparing the diffusion of these changes in today's Italian parliamentary elite with those in the Italian parliamentary elites that operated in the past decades.

The abovementioned phenomena have a global range, but studying the Italian case is of great interest for three reasons.

First, Italy has undergone a crisis of the bipolar party system born in the 1994–1996 period, which manifested itself in the electoral success of a populist party, the Five-Star Movement (Movimento Cinque Stelle, M5S) in the 2013 and 2018 general elections. Additionally, the M5S has also been holding governmental positions since 2018.

Second, and consequently, we can compare some relevant parliamentary elite features of the Italian party system between 1946 and the early 1990s (the so-called Prima Repubblica, First Republic), of that between the early-to-mid-1990s and today (the so-called Seconda Repubblica, Second Republic), and even of that comprised in the 2013–2018 period. These party systems are quite different, with distinct relevant actors. Are there noticeable differences in the features of parliamentary elites across these periods? Or, conversely, are we faced with a long-standing continuity in such features?

Third, the massive challenges faced by many European democracies (Bergmann et al., 2021) are of great relevance in Italy. Indeed, all the typical indicators of political instability, from electoral volatility to governmental vulnerability, from distrust toward politicians to several measures of political polarization, have significantly increased or show worryingly low values (e.g., see Chiaramonte and Emanuele, 2017; Ignazi, 2017). From the elite viewpoint, we can certainly include a higher level of parliamentary turnover (Verzichelli, 2018), while a more in-depth analysis of the qualitative changes in the parliamentary elite is just at the beginning (Coller et al., 2018). These phenomena have been extensively studied (Tormey, 2015; Castiglione and Pollack, 2019) and, indeed, alterations and instability in the processes of elite selection and circulation are evident in several countries (Coller et al., 2018; Freire et al., 2020).

Several factors may be considered as determinants of the recent transformations of parliamentary elites. For instance, the declining trust in the actors and institutions underpinning democratic representation—a phenomenon with long-term causes (Newton and Norris, 2000) accelerated by the Great Recession of the 2010s—might have favored the emergence of new parties and the rapid growth of previously marginal parties (Petrarca et al., 2022). At the same time, some established parties have been pushed to adopt more participatory ways to select candidates (Coller and Cordero, 2018), even if some doubt that these changes have meant a true “democratization” of candidate selection methods (e.g., see Cordero et al., 2018).

These two trends may have altered the selection of parliamentary elites and may have also changed elite stability and circulation patterns. Observers can take two different stances toward these phenomena. On the one hand, the renewal of the political class can be seen as a sign that democracies can adapt to new pressures and accommodate new demands. So, the sudden influx of parliamentarians who are different from the typical career politician—male, affluent, middle-aged, and well-rooted along some party professional ways of life (Blondel and Müller-Rommel, 2007)—is welcomed as an improvement of the social representativeness of the Parliament (Tormey, 2015). On the other hand, the crisis of the consolidated means of selection and circulation of the parliamentary elite, especially in the absence of a consolidated alternative model, may be the prelude to a systemic crisis of democracy that, in turn, may reproduce, at least in Italy, the same uncertainty characterizing the political scenario of one century ago before the inception of the Fascist regime (Farneti, 1978).

In a nutshell, are we facing a new era of representative democracy, or, conversely, are we witnessing its demise? Studying the magnitude of changes within the Italian parliamentary elite might help us understand, at the very least, whether we are dealing with a relevant transformation or, conversely, with a much more neglectable evolution. Such a diachronic study is made possible by using a novel longitudinal dataset on Italian parliamentary elites maintained at the CIRCaP1 Observatory on Political Elites in Italy (COPEI)2. This article represents the first outcome of an ambitious plan to systematize the available data on the Italian political elites, which will allow deeper analyses of several recent relevant phenomena, including changes in descriptive representation, gender representation, and political careers.

Although the ambition of the COPEI project is that of measuring the long-term variation in the profiles of the whole ruling class in Italy, in this article, we focus on Lower House MPs, the largest and most significant segment of the Italian political elite, for reasons of size3 but also of comparability with unicameral or weakly bicameral systems.

The article is organized as follows. In Section Lower House Parliamentary Elites in Italy Since 1946: From Marked Stability to Striking Changes, we present some introductory data on the Italian Lower House parliamentary elite from 1946 until today, and we also elaborate on its stability and circulation. Section Mutation or Systemic Adaptations? Interpretations of Parliamentary Elite Changes in Italy briefly connects changes within such parliamentary elite to several possible explanatory factors. Then, Section MPs' Features, Survival, and Careers in the Decade of the Crises: “More of the Same” or “Something New” is devoted to the main descriptive findings we have extracted from the data related to MPs elected to the Italian Lower House, comparing some MP characteristics in the so-called decade of the crises (the 2010s) vis-à-vis previous political eras. More specifically, we focus on two different arrays of MP features: on the one hand, their age, gender, tenure in Parliament, and pre-parliamentary party-related and institutional experience; on the other hand, MP's continuation of parliamentary experience and their parliamentary career. The final section puts forward some preliminary interpretative insights and briefly sketches some possible research paths opened at the end of our exploratory attempt.

After the unification of the country in the second half of the nineteenth century, the Italian political system has crossed three distinguishable historical phases, characterized by different types of representative elites (Farneti, 1978; Cotta and Verzichelli, 2007):

1. The phase of first democratization (1861–1921), largely dominated by a ruling class of liberal notables, who gave way to a first generation of mass-party politicians (Cotta et al., 2000).

2. The phase of democratic interruption (between the early 1920s and the mid-1940s), when the Fascist authoritarian regime was established at the end of a political and institutional crisis characterized by the extreme polarization among party and parliamentary elites.

3. The republican phase, started in 1946 with the election of a Constituent Assembly and then continued with the consolidation of a compound model of parliamentary democracy, which has been undergoing major systemic crises like that ending the First Republic (1992–1994) and the turbulences of the last decade.

In this section, we aim at producing a longitudinal account on the main transformations of the Italian Lower House parliamentary elite. We do not cover the two earlier historical periods, since we focus on the transformations happening after the birth of the Italian Republic, employing the comparable data that are at the core of the COPEI project.

Figure 1 is based on the most common indicator of elite stability, namely, parliamentary turnover (Cotta and Best, 2007). The figure shows the peaks of parliamentary turnover during the decade of crises (2013 and 2018), when the renewal of the ruling class was even higher than the (still remarkable) average level of the 1992–2008 period. Of course, several factors can explain this phenomenon, including different voluntary and involuntary reasons for non-re-election (Matland and Studlar, 2004; Verzichelli, 2018). However, this indicator seems to point at a clear deviant outcome in elite circulation. To find similarly deviant points in time, we have to go back to the 1994 Italian general election or even to the first democratic elections of Republican Italy (the 1946 and 1948 ones).

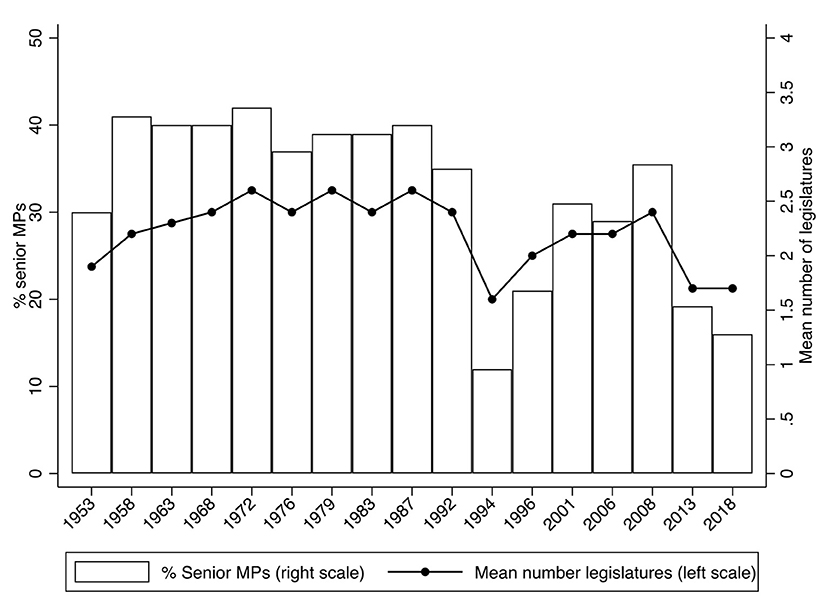

A similar argument applies to the usual indicators of parliamentary seniority (Figure 2): if one looks both at the mean number of legislatures and the percentage of senior members (defined as MPs with an experience of at least two legislatures), a decrease in the percentage of experienced MPs and, consequently, a remarkable decline in the parliamentary life expectancy is patent. Moreover, the trend looks significantly marked during the two elections of the past decade (2013 and 2018), with an alteration of the seniority of the Lower House elite only matched by that of the 1994 general election.

Figure 2. Senior MPs (%) and MPs' mean number of legislatures, Italian Lower House (1953–2018). Senior MPs are those with a tenure of at least two legislatures.

Let us briefly comment on these data: the stability of the parliamentary elite in the 1946–1992 period was due to the continuity of the main actors of the Italian partitocrazia (partycracy) (e.g., see Bardi, 2004, p. 133), specifically, the two most organized parties, the Christian Democracy (Democrazia Cristiana, DC) in the moderate camp and the Italian Communist Party (Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) on the left.

These party actors experienced two somewhat different ways to party professionalization: the clientele-based pattern (DC) promoted career politicians with solid links to social and religious groups, while the apparatus-based pattern (PCI) was mainly relying on politicians with a party milieu (Cotta, 1979). Despite this distinction and other specificities, including a remarkable variance in patterns of representation across Italian subnational territorial units4, Figures 1, 2 show that a certain level of parliamentary institutionalization and seniority used to be the strong feature of the Italian elite until the early 1990s. The dissolution of the classical “polarized multiparty system” (Sartori, 1976) of the First Republic and the subsequent transition in the early-to-mid-1990s to the Second Republic did not completely remove political professionalism (Verzichelli, 1998), but surely started a new process of institutionalization within the Italian parliamentary elite.

How shall we interpret the new political turmoil in terms of elite turnover and seniority happening in the past decade? We have good reasons to envisage relevant elements of systemic change. First, the Italian parliamentary democracy suffered an impasse after the emergence and development of the economic crisis of 2008: the end of the Berlusconi IV government in 2011 and the dissolution of the bipolar party system (with a center-left camp opposed to a center-right camp) established since 1996. Second, the last decade saw two critical general elections (2013 and 2018) and the formation of a “volatile and tripolar” party system (Chiaramonte and Emanuele, 2013) with the rise of the M5S. Third, new personalized, populist, and sovereignist parties, such as the abovementioned Five-Star Movement and the Northern League, have played important roles, even at the executive level (Ivaldi et al., 2017; Albertazzi et al., 2018; Caiani et al., 2021; Vittori, 2021). Fourth, much different governments have appeared in the past few years in Italy: just between 2018 and 2021, three governments, corresponding to three different parliamentary majorities5, including the current technocratic-led government headed by Mario Draghi.

Therefore, the abovementioned elite changes might be connected to a rhetoric of a new model of descriptive representation that, in turn, could have defeated the resilience of a traditional pattern of (parliamentary) elite formation and circulation. Indeed, in the old days of the Italian partycracy, this pattern used to be grounded on a solid control by the national party organizations over a body of people that, in turn, represented the compound territorial and functional constituencies of the Italian society (Wertmann, 1988). We have already underlined that such a traditional model of “local involvement” plus “central control” (ibidem) somehow survived after the collapse of the Italian First Republic (Verzichelli, 1998). However, this model may have significantly evolved after the emergence of the new challenges we have discussed above. In particular, the new populist and leader-based parties may have innovated the processes of elite selection and circulation.

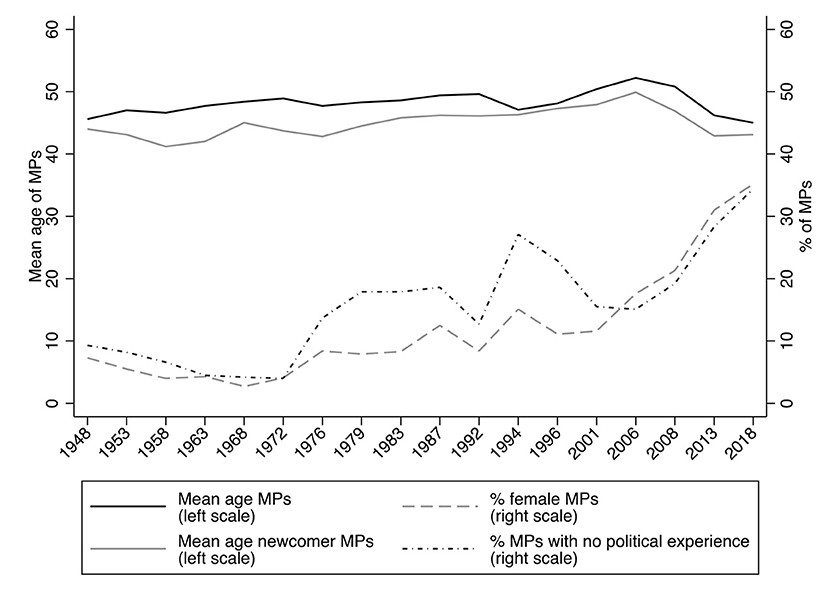

How to empirically support our conjecture? For instance, by analyzing changes in descriptive representation. Figure 3 reports the evolution of three elements of descriptive representation that we have selected for our explorative analysis: MPs' mean age, gender (percentage of women MPs), and what we might call political amateurism (e.g., see Atkinson and Docherty, 1992) (percentage of MPs with no institutional or party-related experience prior to their entrance to Parliament). The figure shows the aggregate values for Italian MPs elected between 1948 and 2018.

Figure 3. Mean age of MPs and newcomer MPs, percentage of female MPs and MPs with no political experience, Italian Lower House (1948–2018).

Three important processes related to the evolution of descriptive representation emerge from Figure 3. First, the acceleration of the increasing trend of female representation. This trend appeared relatively late in Italy compared to other European countries (Cotta and Best, 2007), and the percentage of female MPs remained relatively low until the last decade.

Second, the growing importance of political amateurism. The percentage of MPs with no experience in subnational governments (including both representative and executive offices) or with no experience in party offices at any territorial level prior to their entrance to Parliament6 has increased since 2006. To be fair, this indicator, representing a career opposite to the classical party-rooted professional political career (Cotta and Best, 2007), actually presents remarkable longitudinal variance. For instance, the 1994 peak may be largely explained by the outburst of Forza Italia—at that time, a franchise party (Paolucci, 1999) of “beginners” dominated by its leader, Silvio Berlusconi. Finally, the past decade presents a new and interesting scenario. Indeed, the increase in political amateurism shown in Figure 3 in 2013 and 2018 should be mainly (albeit not exclusively) connected to the sudden electoral success of the M5S, with its inclusive candidate selection rules (at least in 2013), and the related “random” election of MPs with a “politically amateur” background (Tronconi, 2015; Kakepaki et al., 2018; Marino et al., 2019). Let us note that the rhetoric of selecting “ordinary citizens” to become MPs has made its way also within some Italian mainstream parties, that have employed somewhat “open” procedures of political recruitment (e.g., see Cerruto et al., 2016; Marino et al., 2021).

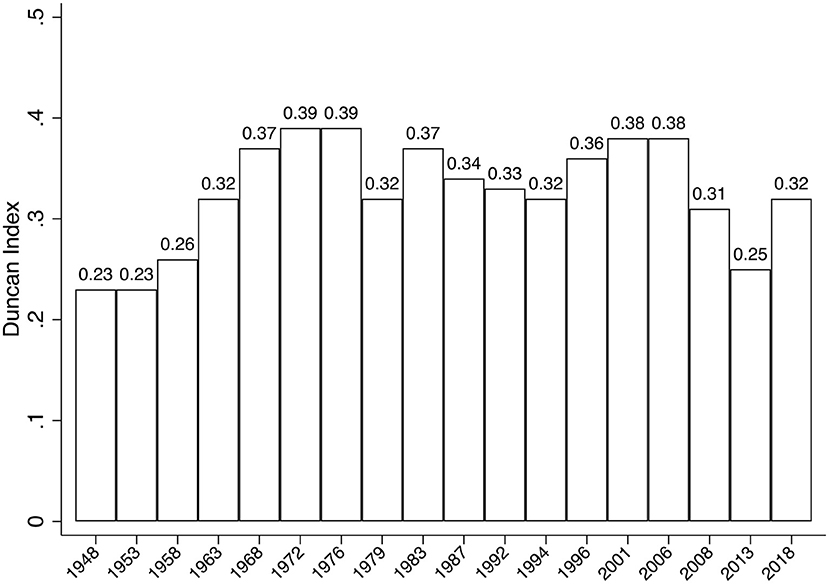

Third, the decreasing mean age of MPs. Figure 3 shows that the passage from the First to the Second Republic in the 1990s did not substantially change the demographic structure of the Italian parliamentary elite, while the general elections of 2013 and 2018 produced a changing scenario. Indeed, since 2013, the mean age of MPs has dramatically collapsed, reaching, in 2018, the lowest value of the whole republican era (45 years). We shall remind that the general decrease in MPs' mean age has paralleled a marked aging of the Italian population7. Let us also note that younger generations are usually underrepresented in parliaments (Stockemer and Sundström, 2018). So, a logical question would be whether the recent entrance of younger MPs has increased the descriptive representation of the Italian Lower House concerning age. To answer this question, we have calculated the dissimilarity between two age structures—that of Italian MPs and that of the Italian population—via the Duncan index of dissimilarity (Duncan and Duncan, 1955)8. Figure 4 shows that, during the first two decades of the Republican era, the Italian Lower House gradually became less and less representative of the Italian over-25 population, at least concerning its age structure. Conversely, in 2013, the Italian Lower House was much more representative than its predecessors. To find such a similarity, we have to go back to 1953, that is, 60 years before the arrival of the M5S in the Lower House. Nonetheless, such representativeness decreased again in 2018.

Figure 4. Duncan index of the dissimilarity between Italian population's age and Italian Lower House MPs' age (Italy, 1948–2018). Elaboration from COPEI dataset, official data from the Lower House (www.camera.it), and ISTAT.

The pictures sketched in the previous section are sufficient to capture the magnitude of the recent changes in some relevant features of the Italian parliamentary elite. Obviously, we have a problem of complexity here: what can account for such changes? There might be different elements to consider. For instance, changes in MPs' social profile can be influenced by a system of opportunities differently shaped by electoral systems (Baumann et al., 2017). Also, party-related factors (such as candidate selection methods, or intra-party power distribution) can directly impact the characteristics of representatives (Hazan and Rahat, 2006). Finally, specific contingent factors can become more and more relevant: e.g., the availability of foreseeable candidates from civil society during an historical phase dominated by mistrust in political professionalism and a return of attention for the educational and professional skills of representatives (Bovens and Wille, 2017).

Some of the changes discussed above may be explained in terms of stochastic or contingent effects, while others could be conceived as long-term processes. For instance, the drastic decrease in MPs' pre-parliamentary institutional or party experience may occur due to two separate paths. Either a sudden and temporary “contagion effect” after the emergence of a party (the M5S) explicitly pushing for a total renewal of the political elite (Kakepaki et al., 2018) or a smoother effect of incremental processes like party organizational changes (Gouglas et al., 2021).

Hence, our task here is to produce a parsimonious reading of all the evidence we have presented so far. We can now refine some propositions about the recent evolution of descriptive representation in Italy (for a broader review, see Russo and Verzichelli, 2020).

A first proposition postulates a radical change in the features of the Italian parliamentary elite because of the failure of the previous mechanisms of elite circulation and the advent of new party actors. After all, both Berlusconi's Forza Italia (at least in its early days) and Beppe Grillo's M5S have put forward a model of representation in sharp contrast with the classical party-centered one (e.g., see Verzichelli, 1994, 1998; Lanza and Piazza, 2002; Pinto and Pedrazzani, 2015). The problem with such an interpretation is predicting if a process of institutionalization will follow or, conversely, there will be an endless influx of new party actors and a consequential “impossible stability” for the Italian parliamentary elite.

A second proposition can conceive the changes in the features of Italian MPs as patent evidence of an existing social process. For instance, a more balanced gender and generational representation would have been realized anyhow, and the sudden collapse of existing elite groups has simply speeded this process up. In this sense, stronger attention to younger generations, female citizens, and “political amateurs” would simply result from such groups' more powerful social and political influence. More specifically, we know that there is a trade-off between an increase in elites' social mirroring and a decline in political professionalism (Cotta and Best, 2007). Consequently, the changes in Italian MPs' features would just be a realignment between citizens and political elites, with the waning of the classical figure of the “career party politician” (King, 1981) balanced by a stronger social mirroring and even by new signs of the impact of meritocracy (Bovens and Wille, 2017).

Some would argue that the problem with these two propositions is that they neglect the role of structural constraints, such as the electoral system in place for the election of MPs. Indeed, some electoral systems could have affected the changes in the Italian parliamentary elites' profile. The extended use of closed-list PR (with a majority bonus) between 2006 and 2013—compared to the open-list PR in place between 1948 and 1992 and to the mixed electoral system used between 1994 and 20019—may have limited innovation efforts in parliamentary elites' profile and background. For instance, between 1994 and 2001, candidates' social profile may have been considered as an advantage compared to a strong party experience, at least in some cases (e.g., see considerations in Galasso and Nannicini, 2011)10.

However, we doubt that the electoral system is the sole determinant to understand the transformations in the Italian Lower House. Indeed, all the relevant changes discussed above and also those discussed in the subsequent pages (that is, the changes after the 1976 general election, after the 1994 one, and after the 2013 and 2018 ones) took place with different electoral systems. Moreover, the relevant changes in the MPs elected in these four general elections are evident also if we compare such elections with the previous and/or subsequent ones, taking place with the same electoral system.

Clearly, we are not arguing that electoral systems do not matter. On the contrary, their role shall be understood in a wider party-system-related and party-related perspective. Indeed, some signs of change may be connected to new relevant actors of the Italian political system (namely, new party organizations and, above all, new party leaders). Moreover, some forms of a “contagion” or “domino” effect, as observed by the classical works on party elites and party organizations by Robert Michels and Maurice Duverger, should be considered as well (e.g., see above and Barnea and Rahat, 2007; Sandri and Venturino, 2020).

Let us stick to our parsimonious reading of the changes in Italian MPs' features. If we assume that the political party has an important role (albeit in connection with electoral systems), we might elaborate on its importance. First, are there relevant differences in some crucial features of Italian Lower House parliamentary party groups (PPGS)? Second, does belonging to different (parliamentary) parties (mainstream ones vs. populist ones; left-leaning ones vs. right-leaning ones) influence Italian MPs' circulation path? Third, is it possible to find a place for an interplay between political parties and electoral systems? In the remaining part of this article, we explore the changing patterns of MPs' features, parliamentary survival, and institutional promotion.

More specifically, we have two main targets. On the one hand, we use some features of the Italian parliamentary elite (e.g., their gender or their previous party-related or institutional experience before entering Parliament) to create three categories of MPs which represent the most evident deviations from the traditional dominant profile of Italian MPs. As already argued above, such a dominant profile was the tenured parliamentarian having had a certain career within a political party or in subnational institutional positions (Cotta, 1992; Verzichelli, 2010). Then, we investigate whether and in which PPG such innovative categories have acquired more relevance.

On the other hand, we tackle MPs' capability to continue their carrier in Parliament and MPs' ability to get relevant parliamentary positions11. We want to understand whether belonging to different MP categories, or different PPGs, or different Lower Houses in the 1970s, 1990s, or 2010s, means something for MPs' survival in Parliament and their parliamentary careers.

To put forward this exploration, we focus on the main PPGs of the Italian republican history. For the 1946–1992 period, the DC and the PCI ones12. For the 1994–2008 period, the FI-PDL-FI13 and Progressives-Olive Tree-PD14 PPGs. Finally, for the 2013–2018 period, we have added the M5S PPG to the FI and PD ones.

Let us start this section with the first task we have just outlined above. We consider four MPs' features: whether they are newcomers or not; their institutional or party-related experience before their entrance to Parliament; their gender; and their age. Then, we categorize MPs into three partially overlapping categories: Intruders (namely, newcomer MPs with no previous party and local institutional experience)—using the categorization by Marino et al. (2019)—Female Beginners (female MPs entering Parliament for the first time), and Young Beginners (under-40 years-old entering Parliament for the first time).

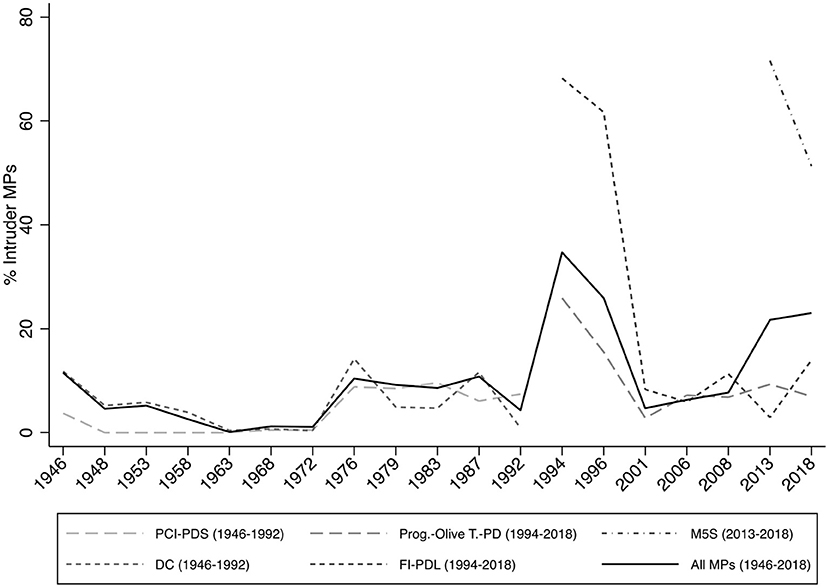

Figure 5 below reports the percentage of Intruder MPs in the Lower House for each PPG under consideration. The figure also reports the percentage of Intruder MPs for the entire Italian Lower House.

Figure 5. Intruder MPs (%), Italian Lower House (selected parliamentary party groups and entire House) (1946–2018).

Figure 5 allows us to focus on some key points. First, between 1946 and 1992, but especially from 1963 onwards, there were almost no relevant differences between the Christian-Democratic parliamentary party group (DC) and the Communist one (PCI). Moreover, outsider MPs remained marginal in the entire Lower House population15, although the 1976 Italian general election confirms to be a turning point in the history of the Italian Parliament (Di Palma, 1977). All in all, in the Italian First Republic, there was quite some homogeneity in terms of entrance to the Lower House of MPs with no institutional or party experience, at least when considering the two biggest PPGs (the DC and PCI ones).

Things changed dramatically in 1994, with the electoral success of Forza Italia. Figure 4 shows a sudden increase in the percentage of Intruders with the entrance to Parliament of Berlusconi's party. A clear distinction between the center-left and the center-right PPGs also emerges, as shown by the different percentages of Intruders in the FI and the Progressives PPGs. All in all, the figure tells us that, given the extraordinary result of Forza Italia and the center-right coalition in the 1994 Italian general election, a significant percentage of “new people” entered the Lower House, so much so that more than one-third of all MPs in 1994 can be categorized as Intruders. This is in line with previous discussions about the longitudinal changes in the features of the Italian MPs during the transition from the old partitocrazia to the new bipolar party system in the mid-1990s (Verzichelli, 1994).

Our story then follows an institutionalization pattern of elite circulation amongst the Italian Lower House PPGs considered here, with an overall declining trend in the percentage of Intruder MPs until 2006. Subsequently, in 2008, the competition between the PD, led by Walter Veltroni, and Berlusconi's PDL was marked by a slight increase in the percentage of Intruders. However, this was just the entree of a much more substantial change.

Indeed, in 2013, the unexpected result of Grillo's M5S led to the entrance of many Intruders to the Italian Lower House (Marino et al., 2019). Consequently, also the percentage of “new people” among the entire population of Italian MPs noticeably increased. Conversely, it is quite interesting to notice that the M5S trend is flanked by a much more traditional pattern of elite circulation for the main center-left and center-right parties. Indeed, in 2013, the PPGs of the PD and FI showed remarkably low percentages of Intruders, with even much lower values than the DC and PCI figures in 1976. In other words, from this specific viewpoint, the “old” and discredited parties of the Italian First Republic were much more innovative than the “new” parties of the Second Republic.

Finally, the 2018 Italian general election returned a Lower House with a peculiar configuration: a still remarkable percentage of Intruders, but with the M5S PPG showing a declining percentage of such MPs. Only time will tell if this is a sign of the institutionalization of its parliamentary elite. In any case, the data reported so far clearly stress the context of an erratic process of elite formation, with relevant party-specific differences to consider (Marino et al., 2019).

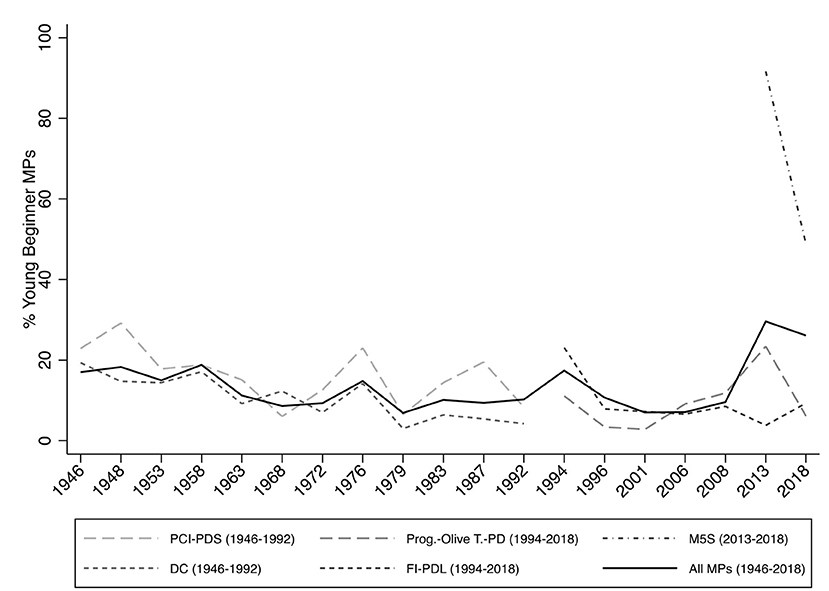

Let us now focus on the evolution of the percentage of Young Beginner MPs (i.e., untenured MPs younger than 40 years-old) shown in Figure 6. The slow decrease in the percentage of Young Beginners, at least until the 1980s, can be understood as a sign of institutionalization of the old PPGs of the Italian First Republic. Then, going forward, the now-usual spikes of 1994 and 2013 confirm the innovative character of these two general elections for the Italian parliamentary elite. Turning to party-related differences, we notice a difference between the PCI PPG, more inclined to recruit younger cohorts of candidates, and the DC PPG (Cotta, 1979). Nonetheless, this pattern was overturned in 1994, when the emergence of Berlusconi's party brought a substantial number of young newcomer MPs to the Lower House, whereas the center-left Progressives had an older and/or more experienced pool of MPs. In 2006, the center-left seemed to turn the table, but we are still talking about marginal changes, especially if one compares the 1946–2008 figures with the 2013–2018 period, when the electoral success of the M5S determined an exceptional rate of rejuvenation of the Italian parliamentary elite. So, the percentage of Young Beginner MPs in 2018 was still the second-highest registered in the Italian Lower House (being the 2013 one the highest ever registered), while the 1976 peak was even lower than the 1994 one. Finally, let us notice that, even when it comes to Young Beginner MPs, the M5S passage from 2013 to 2018 hints at a possible institutionalization of its elite in the Lower House.

Figure 6. Young beginner MPs (%), Italian Lower House (selected parliamentary party groups and entire House) (1946–2018).

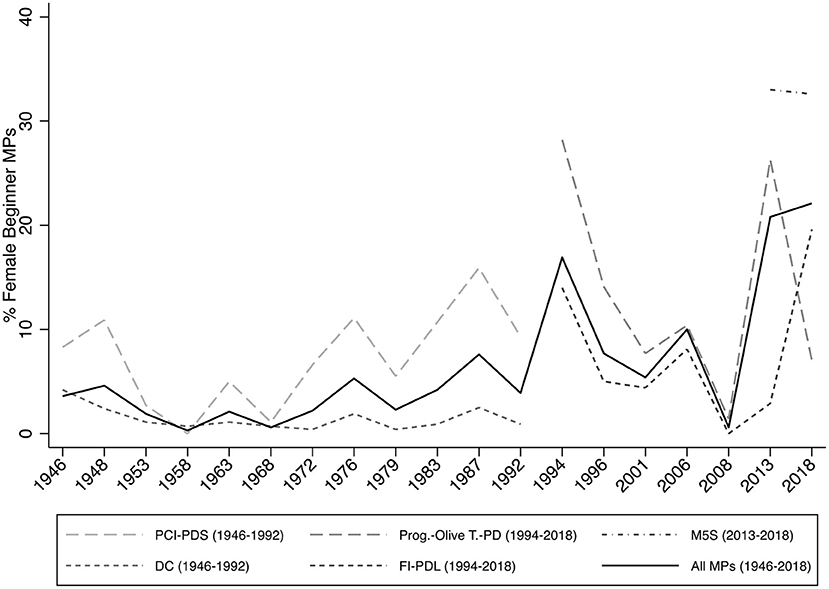

Let us now focus on the third MP category: Female Beginner MPs. Figure 7 below reports the percentage of MPs belonging to such a group for our selected PPGs and the entire House.

Figure 7. Female beginner MPs (%), Italian Lower House (selected parliamentary party groups and entire House) (1946–2018).

The changes in this indicator are particularly relevant to consider, especially in a country where gender representation has always proved to be particularly difficult (Papavero, 2009). As already noticed in Figure 5 and especially Figure 6, there is a general pattern of stability until the 1976 turning point, plus two peaks (the Lower Houses elected in 1994 and 2013).

Here, however, two comments should be made concerning the impact of structural factors, like the electoral system, or party-related factors. First, the (increasing) trend of Female Beginner MPs records several highs and lows, which have become more and more marked since 1992. The 1994 peak should be somehow connected to the rule of the male-female alternation in the closed-list PR arena in the Lower House (Verzichelli, 1994). Such a rule was then abrogated but partially re-established with the 2005 reform of the Italian electoral law (that introduced a minimum quota of female candidate in the multi-member constituencies used since 2006).

Second, the increasing trend of Female Beginner MPs has almost always remained more pronounced in the (center-)left camp than in the Christian-Democratic and the center-right ones. In this regard, the 2018 overtaking of FI at the expenses of the PD needs to be evaluated in the mid-to-long term, given the reduced population of these two groups, which became smaller than the M5S and the Lega Nord (Northern League) PPGs after the 2018 Italian general election (Marino et al., 2019). Finally, also when it comes to Female Beginner MPs, it was the M5S to be the main driver of innovation in the Italian Lower House in the 2013–2018 period.

All in all, there are some general elections that, compared to the previous and the subsequent ones, brought about a robust change in some parliamentary elites' features: the 1976, 1994, 2013, and 2018 ones. Such general elections are not connected to an equal change among the selected parties, but to the impact of some party actors, whose weight is more prominent than others'. Third, and finally, what we have just analyzed seems to point at a complex interaction between electoral systems and political parties, in the sense that both elements shall be jointly considered in the understanding of the changes within the Italian parliamentary elite.

The second task we deal with is the analysis of MPs' parliamentary survival and careers. In particular, we have considered the two most varying MP categories discussed above—Intruder MPs and Female Beginner MPs—to explore whether belonging to such clusters makes a difference in terms of survival and careers in the Lower House. This final analysis can be extremely useful to better understand which actors—if any—can be considered as the main drivers of change in MPs' circulation path.

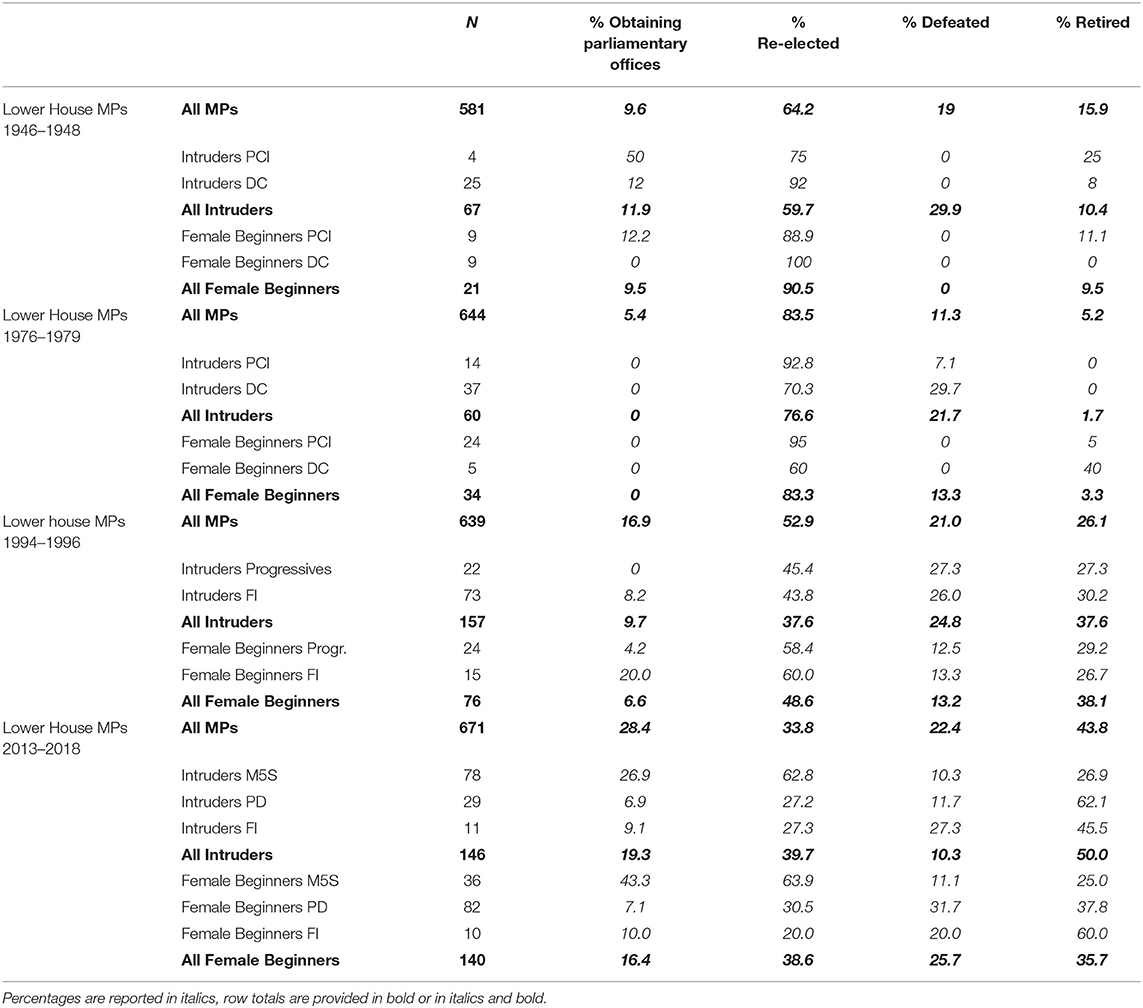

Table 1 below reports our analysis, conducted on different historical junctures: the inception of representative democracy, after a long dictatorship, and three critical elections already discussed in our comments of Figures 5–7. Specifically, we consider all MPs elected in four legislative terms: the one beginning in 1946 (the election of the Constituent Assembly that later would have passed the Italian Constitution in 1947)16, the one beginning in 1976 (where the DC and PCI together collected more than 70% of the votes), the one beginning in 1994 (with the inception of Berlusconi's Forza Italia), and, finally, the one started in 2013 (with the electoral success of the M5S). Moreover, we focus on the parliamentary career and survival of Intruder and Female Beginner MPs both from a general viewpoint and from a (parliamentary) party one.

Table 1. Parliamentary survival and careers (N and %), Italian Lower House (selected MP categories, selected parliamentary party groups, and entire House) (1946, 1976, 2013, and 2018).

All in all, we compare the percentages of Intruder, Female Beginner, and all MPs obtaining parliamentary offices, but also their rate of re-election, electoral defeat, and retirement with the beginning of the subsequent legislative term (so, 1948, 1979, 1996, and 2018). Moreover, such percentages are presented for the main PPGs, the two categories of Intruder and Female Beginner MPs, and the entire House.

This analysis is clearly descriptive, but there are enough data to suggest that the emergence of new generations of Italian MPs has never created revolutionary effects. Indeed, in terms of parliamentary career, belonging to our two categories of MPs does not seem to matter: Intruder and Female Beginner MPs tend to have very limited success in terms of obtaining parliamentary offices (except for M5S MPs in 2013).

Moreover, Intruder MPs seem to have also a limited parliamentary life expectancy. Nonetheless, the situation partly changes if we take a closer look at party-related figures for Intruders and Female Beginners. For instance, in terms of re-election, apart from some noticeable exceptions (e.g., the PD and FI Intruders and Beginners in 2013–2018), belonging to the selected PPGs we have considered increases the chances of re-election, all other things being equal, compared to the entire population of Intruders or Female Beginners but also compared to the entire Lower House.

In other words, belonging to a numerous and strong PPG gives MPs a potential boost for the continuation of their career. Conversely, the picture for MPs' retirements is more puzzling, but we can again argue that—also here, considering some important exceptions—for an MP is important to belong to a powerful PPG to have more chances to continue her/his career, all other things being equal.

For instance, M5S MPs are much younger, less politically experienced, and with a stronger female component than the other relevant Parliamentary Party Groups. Nonetheless, M5S MPs with no previous party or institutional experience or M5S female MPs entering Parliament for the first time are more likely to get parliamentary offices, more likely to get re-elected, less likely to get defeated in the ballot box, and less likely to retire from politics than other politically unexperienced MPs or other female newcomer MPs. What is clear is that the emergence of a new powerful populist actor like the M5S does not seem to have established a clear innovative pattern of elite careers.

In a nutshell, the descriptive data of this last analysis are in line with a classical rule of selection of an inner circle of career politicians (King, 1981): belonging to a strong and powerful parliamentary party group remains important to have more chances to belong to the long-standing parliamentary elite, even when more and more people with no previous political or party-related experience are elected to Parliament. We can also speculate that the activation of some path-dependent practices of parliamentary institutionalization (Cotta, 1992; Verzichelli, 1998) and the importance of being a tenured, male, and party-rooted elite member vis-à-vis outsiders may have helped the persistence of a seniority practice (Polsby, 1968), preventing the representation at the higher institutional level of the most innovative groups of MPs.

Let us conclude by focusing on a final point. The changes in MPs' features and careers brought about by the 2013 Italian general election (and somehow continued with the 2018 general election also thanks to the numerical strength of the M5S PPG) should not simply be wiped off. In this sense, the numerosity of Intruders and Female Beginners in 2013 and 2018 is remarkable, especially if compared to the previous critical junctures described in Table 1.

Our exploration of COPEI data on the Italian Lower House parliamentary elite is only at the beginning. However, the data tackled so far allow us to discuss our conjectures and offer a first general interpretation.

The longitudinal analysis of the features and career of Italian MPs throughout more than 70 years shows that the impact of the changes happened during the recent “decade of the crises” is significantly different from the past, both in terms of magnitude and qualitative mutations. In particular, the 2013 and 2018 Lower Houses, especially thanks to the emergence and consolidation of an innovative party like the M5S, saw a much new pattern of parliamentary elite, with important effects on the overall picture of descriptive representation and parliamentary career paths.

Starting from descriptive representation, it is very likely that the organizational evolution of the M5S (or even its possible future dissolution) will leave important legacies in the pattern of the social representation of Italian MPs. Maybe, a broader form of “domino” or “contagion” has started, and other party actors might bring the evolution of Italian MPs to new levels. Indeed, some other more “traditional” parliamentary party groups have somewhat evolved in a direction like that of the M5S, extending their quota of young untenured (and/or) female parliamentarians or reducing the number of MPs with previous experience within political parties or representative institutions.

However, if the process of parliamentary elite selection seems to be less and less a “secret garden”, in the words of Gallagher and Marsh (1988), because more and more “ordinary citizens” can enter Parliament, our data on elite circulation tell us a different story. Indeed, there is a structural difficulty in providing the fresher generation of MPs with high rates of parliamentary survival, unless MPs belong to a powerful parliamentary party group. Clearly, as already stated, structural factors like party-system-related ones or electoral-system-related ones shall be taken into consideration as well when one evaluates changes in the career features of (specific categories of) MPs.

Finally, a much more uncertain picture emerges if one considers obtaining a parliamentary office: if we exclude the 1946–1948 period (where the Italian Republican parliamentary class was just starting to consolidate after the end of the Fascist dictatorship), there are relevant differences among different parliamentary party groups, possibly because MPs belonging to political parties that have won or lost the previous general election have partially different fates. Moreover, as a general rule of thumb, being an untenured MP without previous party-related or institutional experience is a con when getting parliamentary offices.

The insights from our descriptive study can also pave the way for a new wave of empirical research on parliamentary elites that can depart toward different directions, also thanks to the data on the Italian parliamentary elite provided by the COPEI project. For instance, what are the determinants of the selection of different types of MPs by different political parties? Is it a matter of “populist rhetoric”? Or is there also a “contagion effect” at work here? Which is the role of stronger party leaders in this process? Another potentially yielding road to take would be precisely understanding the determinants of parliamentary elite re-selection and retirement, in line with some works on MPs' re-candidacy for general elections (e.g., see Marino and Martocchia Diodati, 2017). Finally, it would also be interesting to understand whether the descriptive results we have sketched in this article—and hopefully also results from more inferential future pieces of research—are overlapping, and to what extent, to empirical research on other Western European countries.

We believe all these research questions can be of great interest to better understand the features and career of Italian and Western European parliamentary elites, not forgetting the central role of an alleged dying actor—the political party. Indeed, besides the rhetoric of “social mirroring” and descriptive representation brought about by populist parties and their leaders, what seems to play an important (albeit not exclusive) role in fostering Italian MPs' career is belonging to specific powerful parliamentary party groups. As written by Michels (1915[2001], p. 234): “si cambia il maestro di cappella, ma la musica è sempre quella” (the Maestro changes, but the music is still the same).

The data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

LV devised the design of the study. BM and LV performed the data analysis. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^The CIRCaP is the Centre for the Study of Political Change at the University of Siena (https://www.circap.unisi.it/).

2. ^Unless otherwise specified, the data presented in this article come from the COPEI dataset, whose harmonization is currently in progress. The Observatory will include data on Italian political elites such as MPs (from both the Lower and the Upper Houses), the Italian Members of the European Parliament, Ministers, and other members of the government. For more information, see https://www.circap.unisi.it/elites-and-political-leadership/circap-observatory-on-political-elites-in-italy-copei/. The number of MPs used to calculate percentages and absolute numbers for figures and tables includes both MPs elected at the beginning of a legislative term and MPs elected as substitute during a legislative term.

3. ^Such a size is going to be reduced from 630 to 400 seats starting from the next general election (theoretically to be held in 2023) after a confirmatory referendum, held in 2020, approved a constitutional reform aiming at reducing the number of MPs in the two Italian Houses. As for the Italian Upper House, the abovementioned confirmatory referendum approved the constitutional reform that reduced the number of its members from 315 to 200.

4. ^For instance, in the first decades of the First Republic, Southern MPs used to be much less professionalized than the MPs coming from the Northern regions (Cotta, 1979).

5. ^The first one, between 2018 and 2019, was the so-called Conte I government, supported by the Five-Star Movement and the Northern League; the second one, between 2019 and 2021, was the Conte II government, supported by the Five-Star Movement, the Democratic Party and some smaller center and left parties; finally, since March 2021, there has been the Draghi government, supported by a grand coalition of many parties in the Italian Parliament.

6. ^Still building on Best and Cotta (2000), an MP has “no relevant political function” when he/she did not hold any kind of party office or any subnational administrative office before her/his entrance to Parliament.

7. ^E.g., see data on Italians' mean age on http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx (Population and Households/Population).

8. ^We applied the following formula: , where i = 1…15 represents 15 five-year age classes (25–29, 30–35 and so on, up to 100 and older), pi is the proportion of the Italian population older than 25 years old falling within age class i and di is the proportion of MPs falling in age class i. The range of the Duncan index goes from 0, where there is no difference between the two distributions, and 1, where such a difference is maximum.

9. ^Between 1994 and 2001, 75% of Italian MPs were elected in a First-Past-the-Post arena, while the remaining 25% were elected in a closed-list PR arena.

10. ^On the territorial sensibilities of MPs elected in single-member districts compared to the other MPs, see Russo (2022).

11. ^Building on Cotta (1979), for the purpose of this article, we have only considered the dimension of institutional offices in Parliament. The offices covered are those of the Lower House parliamentary bureau (Secretary, Questor, Vice- President, and President), the Chairmanship and Vice-Chairmanship of legislative committees, and the Chairmanship and Vice-Chairmanships of parliamentary party groups (PPGs).

12. ^The PCI line also includes data for the Partito Democratico della Sinistra (PDS, Democratic Party of the Left), which was its main successor in 1992.

13. ^After the 2008 general election, Berlusconi's Forza Italia PPG appears together with that of Alleanza Nazionale (AN, National Alliance), the main heir of the neo-fascist Movimento Sociale Italiano, (MSI, Italian Social Movement). Such a joint group was called Popolo della Libertà (PDL, People of Freedoms), and this latter was also the name of the political party appearing from the merging of FI and AN. However, such an experience was unsuccessful, and Berlusconi's party was renamed Forza Italia after the 2013 general election.

14. ^In the 1994 Italian Lower House, we considered the Progressisti (Progressives) parliamentary group; between 1996 and 2006, we considered the Ulivo (Olive Tree) parliamentary party group; finally, between 2008 and 2018, the Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party) parliamentary party group.

15. ^This should not come entirely as a surprise, given the low percentage of Intruder MPs in the DC and PCI PPGs and the relevant weight of the DC and PCI PPGs in the Italian Lower House from the mid-1940s until 1992. Nonetheless, we shall also remember that there were other non-marginal PPGs between the mid-1940s and the early 1990s [let us just mention the Italian Socialist Party (Partito Socialista Italiano, PSI) one and the MSI one]. In a nutshell, the Italian Lower House was hardly a prototype of a two-party House (see, for instance, data on the Effective Number of Parliamentary Parties in Bardi, 2007).

16. ^Despite not (always) appearing in the discussion of Figures 1–7, we have decided to devote some attention to the 1946-1948 legislature because the 1946 election of the Constituent Assembly was the first democratic election held in Italy after the fall of the Fascist dictatorship and also the first one to be held with universal male and female suffrage.

Albertazzi, D., Giovannini, A., and Seddone, A. (2018). ‘No regionalism please, we are Leghisti!’ The transformation of the Italian Lega Nord under the leadership of Matteo Salvini. Region. Federal Stud. 28, 645–671. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2018.1512977

Atkinson, M. M., and Docherty, D. C. (1992). Moving right along: The roots of amateurism in the Canadian House of Commons. CJPS/RCSP. 25, 295–318. doi: 10.1017/S0008423900003991

Bardi, L. (2004). “Party responses to electoral dealignment in Italy”, in Political Parties and Electoral Change, eds P. Mair, W. C. Müller and F. Plasser (London: Sage), 111–144.

Bardi, L. (2007). Electoral change and its impact on the party system in Italy. West Eur. Polit. 30, 711–732. doi: 10.1080/01402380701500256

Barnea, S., and Rahat, G. (2007). Reforming candidate selection methods: a three-level approach. Party Politics 13, 375–394. doi: 10.1177/1354068807075942

Baumann, M., Debus, M., and Klingelhofer, T. (2017). Keeping one's seat: the competitiveness of MP renomination in mixed-member electoral systems. J Polit. 79, 979–994. doi: 10.1086/690945

Bergmann, H., Bäck, H., and Saalfeld, T. (2021). Party-system polarisation, legislative institutions and cabinet survival in 28 parliamentary democracies, 1945–2019. West Eur Polit. 45, 612–637. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2020.1870345

Best, H., and Cotta, M., (eds.). (2000). Parliamentary Representatives in Europe. 1948-2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Blondel, J., and Müller-Rommel, F. (2007). “Political elites”, in The Oxford Handbook of Political Behaviour, eds R. J. Dalton and H. D. Klingemann (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 818–832.

Bovens, M., and Wille, A. (2017). DIploma Democracy. The Rise of Political Meritocracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Caiani, M., Padoan, E., and Marino, B. (2021). Candidate selection, personalization and different logics of centralization in New Southern European populism: the cases of podemos and the M5S. Govern. Oppos. doi: 10.1017/gov.2021.9

Castiglione, D., and Pollack, M., (eds.). (2019). Creating Political Presence. The New Politics of Democratic Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cerruto, M., Facello, C., and Raniolo, F. (2016). How has the secret garden of politics changed in Italy (1994-2015)? Am. Behav. Sci. 60, 869–888. doi: 10.1177/0002764216632824

Chiaramonte, A., and Emanuele, V. (2013). “Volatile and tripolar: the new italian party system” in The Italian General Election of 2013, eds L. De Sio, V. Emanuele, N. Maggini and A. Paparo (Rome: CISE), 63–68.

Chiaramonte, A., and Emanuele, V. (2017). Party system volatility, regeneration and de-institutionalization in Western Europe (1945-2015). Party Politics 23, 376–388. doi: 10.1177/1354068815601330

Coller, X., and Cordero, G., (eds.). (2018). Democratizing Candidate Selection in Times of Crisis: New Methods, Old Receipts?. London: Palgrave.

Coller, X., Cordero, G., and Jaime-Castillo, A. M., (eds.). (2018). The Selection of Politicians in Times of Crisis. London: Routledge.

Cordero, G., Coller, X., and Jaime-Castillo, A. M. (2018). “The effects of the great recession on candidate selection in America and Europe” in The Selection of Politicians in Times of Crisis, eds X. Coller, G. Cordero and A. M. Jaime-Castillo (London: Routledge), 262–277.

Cotta, M. (1992). “Elite unification and democratic consolidation in italy: an historical overview,” in Elites and Democratic Consolidation in Latin America and Southern Europe, eds J. Higley and R. Gunther (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 146–177.

Cotta, M., and Best, H., (eds.). (2007). The European Representative. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cotta, M., Mastropaolo, A., and Verzichelli, L. (2000). “Italy: parliamentary elite transformations along the discontinuous road of democratization”, in Parliamentary Representatives in Europe. 1948–2000, eds H. Best and M. Cotta (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 226–269.

Cotta, M., and Verzichelli, L. (2007). Political Institutions in Italy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Di Palma, G. (1977). “Christian democracy: the end of hegemony”, in Italy at the Polls: The Parliamentary Elections of 1976. ed H. R. Penniman (Washington: American Enterprise Institute), 123–153.

Duncan, O. D., and Duncan, B. (1955). A methodological analysis of segregation indexes. Am. Sociol. Rev. 20, 210–217. doi: 10.2307/2088328

Farneti, P. (1978). “Social conflict, parliamentary fragmentation, institutional shift and the rise of fascism”, in The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes. ed J. J. Linz (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press), 3–31.

Freire, A., Barragán, M., Coller, X., Lisi, M., and Tsatsanis, E., (eds.). (2020). Political Representation in Southern Europe and Latin America. London: Routledge.

Galasso, V., and Nannicini, T. (2011). Competing on good politicians. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 105, 79–99. doi: 10.1017/S0003055410000535

Gallagher, M., and Marsh, M., (eds.). (1988). Candidate Selection in Comparative Perspective: The Secret Garden of Politics. London: Sage.

Gouglas, A., Katz, G., Maddens, B., and Brans, M. (2021). Transformational party events and legislative turnover in West European democracies, 1945–2015. Party Polit. 27, 1211–1222. doi: 10.1177/1354068820944703

Hazan, R. Y., and Rahat, G. (2006). The Influence of candidate selection methods on legislatures and legislators: theoretical propositions, methodological suggestions and empirical evidence. J. Legis. Stud. 12, 366–385. doi: 10.1080/13572330600875647

Ivaldi, G., Lanzone, M. E., and Woods, D. (2017). Varieties of populism across a left-right spectrum: the case of the front national, the northern league, podemos and five star movement. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 23, 354–376. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12278

Kakepaki, M., Kountouri, F., Coller, X., and Verzichelli, L. (2018). “The socio-political profile of parliamentary representatives in greece, italy and spain before and after the ‘Eurocrisis’: a comparative empirical assessment”, in Democratizing Candidate Selection in Times of Crisis: New Methods, Old Receipts?. eds X. Coller and G. Cordero (London: Palgrave), 175–200.

Karremans, J., and Lefkofridi, Z. (2020). Responsive versus responsible? Party democracy in times of crisis. Party Polit. 26, 271–279. doi: 10.1177/1354068818761199

King, A. (1981). The rise of the career politician in britain and its consequences. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 11, 249–285. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400002647

Lanza, O., and Piazza, G. (2002). I Parlamentari di Forza Italia: un Gruppo a Sostegno di una Leadership? Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica 32, 425–457. doi: 10.1017/S0048840200030379

Marino, B., and Martocchia Diodati, N. (2017). Masters of their fate? Explaining MPs' re-candidacy in the long run: the case of Italy (1987-2013). Elect. Stud. 48, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2017.05.001

Marino, B., Martocchia Diodati, N., and Verzichelli, L. (2019). “Members of the Chamber of Deputies” in The Italian General Election of 2018, eds L. Ceccarini and J. L. Newell (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 271–295.

Marino, B., Martocchia Diodati, N., and Verzichelli, L. (2021). “Candidate selection, personalization of politics, and political careers. Insights from Italy (2006– 2016)”, in New Paths for Selecting Political Elites. Investigating the impact of inclusive Candidate and Party Leader Selection Methods, eds G. Sandri and A. Seddone (London: Routledge), 82–105.

Matland, R. E., and Studlar, D. T. (2004). Determinants of legislative turnover: a cross-national analysis. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 34, 87–108. doi: 10.1017/S000712340300036X

Michels, R. (1915[2001]). Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy. Kitchener: Batoche Books.

Newton, K., and Norris, P. (2000). “Confidence in public institutions: faith, culture or performance?” in Disaffected Democracies: What's Troubling the Trilateral Countries? eds S. J. Pharr and R. D. Putnam (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 52–73.

Paolucci, C. (1999). Forza Italia a livello locale: un marchio in franchising? Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica 29, 481–516. doi: 10.1017/S0048840200028926

Papavero, L. (2009). “Donne e rappresentanza parlamentare nell'Italia repubblicana,” La Cultura Italiana, Quinto volume: Struttura della società, valori e politica, eds A. Bonomi, N. Pasini, and S. Bertolino (Turin: UTET), 296–321.

Petrarca, C. S., Giebler, H., and Weßels, B. (2022). Support for insider parties: the role of political trust in a longitudinal-comparative perspective. Party Polit. 28, 329–341. doi: 10.1177/1354068820976920

Pinto, L., and Pedrazzani, A. (2015). “From ‘citizens’ to members of parliament: the elected representatives in the parliamentary arena”, in Beppe Grillo's Five Star Movement: Organisation, Communication and Ideology. ed F. Tronconi (Farnham: Ashgate), 99–125.

Polsby, N. (1968). The institutionalization of the U.S. house of representatives. Am. Poli. Sci. Rev. 62, 144–168. doi: 10.2307/1953331

Roberts, K. M. (2017). “Populism and political parties,” in The Oxford Handbook of Populism, eds C. Rovira-Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, and P. O. Espejo (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 287–304.

Russo, F. (2022). MPs' Roles and Representation: Orientations, Incentives and Behaviours in Italy. Abingdon and New York, NY: Routledge.

Russo, F., and Verzichelli, L. (2020), “Representation in the Italian parliament,” in Political Representation in Southern Europe Latin America, eds A. Freire, M. Barragán, X. Coller, M. Lisi, E. Tsatsanis (London: Routledge), 50–65.

Sandri, G., and Venturino, F. (2020). Party organization and intra-party democracy in Italy. Contemp. Ital. Polit. 12, 443–460. doi: 10.1080/23248823.2020.1838867

Sartori, G., and Somogyi, S. (1963). Il Parlamento Italiano, 1946-1963. Naples: Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane.

Stockemer, D., and Sundström, A. (2018). Age representation in parliaments: can institutions pave the way for the young? Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 10, 467–490. doi: 10.1017/S1755773918000048

Tronconi, F., (eds.). (2015). Beppe Grillo's Five Star Movement: Organisation, Communication and Ideology. Farnham: Ashgate.

Verzichelli, L. (1994). Gli Eletti. Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica 24, 715–739. doi: 10.1017/S0048840200023261

Verzichelli, L. (1998). The parliamentary elite in transition. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 34, 121–150. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00401

Verzichelli, L. (2010), Vivere di Politica. Come (non) cambiano le carriere politiche in Italia. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Verzichelli, L. (2018). “Degradable elites? Modes and factors of parliamentary turnover in europe in the early twenty-first century,” in The Contested Status of Political Elite: At the Crossroad, eds L. Vogel, R. Gebauer, and A. Salheiser (London: Routledge), 87–107.

Keywords: Italy, parliamentary elites, political careers, descriptive representation, crisis

Citation: Verzichelli L, Marino B, Marangoni F and Russo F (2022) The Impossible Stability? The Italian Lower House Parliamentary Elite After a “Decade of Crises”. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:790575. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.790575

Received: 06 October 2021; Accepted: 27 April 2022;

Published: 17 June 2022.

Edited by:

Guillermo Cordero, Autonomous University of Madrid, SpainReviewed by:

Christoffer Green-Pedersen, Aarhus University, DenmarkCopyright © 2022 Verzichelli, Marino, Marangoni and Russo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Luca Verzichelli, bHVjYS52ZXJ6aWNoZWxsaUB1bmlzaS5pdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.