95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 16 January 2023

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.1075462

As women increasingly participate in political decision-making around the world, the research emphasizes the need to further understand how informal barriers shape women's political participation. At the same time, the persistent stability of hybrid political regimes calls for additional inquiry into the impact of hybrid regimes on gender politics and its actors. Based on the case of Turkey, a hybrid regime, this study explores how women MPs navigate gendered, informal obstacles in parliament and to what extent their navigation strategies reflect the broader implications posed by the hybrid regime context. This exploratory study draws on qualitative, in-depth semi-structured interviews with eight women MPs in the Turkish parliament from government and opposition parties. The findings illustrate that navigating the informal barriers women MPs experience in the Turkish parliament happens both individually and in collective ways. Individually, women MPs choose to navigate the informal barriers of gender norms by either assimilating or contrasting the masculine way of doing politics. Collective navigation strategies of women MPs in the Turkish parliament illustrate their approaches to representing women's interests, seeking women's solidarity across the parliament, and linkages with civil society to empower women, which also reflect the different positionings of government and opposition within the Turkish hybrid regime dynamics. The findings reveal the need to further research the complex, dynamic interplay of how informal practices and hybrid regime tactics target gender politics and its actors, while also giving more attention to women's agency in tackling and countering obstacles to their political power within and beyond political institutions.

Despite steady increases in women's parliamentary representation around the globe, currently, at 25.5% (Childs and Lovenduski, 2013; Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), 2021),1 political institutions such as parliaments remain mostly gendered spaces that inhibit various formal and informal barriers to women's access, participation, and influence in decision-making (Lovenduski, 2005; Krook and Mackay, 2011; Paxton and Hughes, 2015).

At the same time, trends of democratic decline and rising authoritarianism around the world pose further threats to women's political access, power, and participation in formal institutions, such as parliaments, and beyond (Ilonszki and Vajda, 2019). Hybrid regimes are neither full democracies nor full autocracies, but rather constitute an often continuously stable “gray zone” in between both, and this gray zone has different implications for the opportunities and limitations of gender politics and women's political power (Tripp, 2013).

Politics and gender scholarship have widely explored the active role of women's civil society organizing related to democratic transitions (Waylen, 1994; Alvarez, 1999). Recently, more attention is brought toward a better understanding of the multiple, dynamic facets of hybrid and authoritarian regimes in connection to women's rights. Such studies highlight in what ways women's civic activism and participation in formal politics can also be strategically used by such regimes, for example, as legitimation strategies or to gain voter support, or to allow the certain provision of women's rights as an illusion of democratic practice while covering up other violations or repression, for example, human rights (Lorch and Bunk, 2016; Valdini, 2019; Bjarnegård and Zetterberg, 2022). Yet, women's experiences of parliament as a gendered institution and particularly how informal obstacles influence their political power remains understudied in hybrid regime contexts (Inguanzo, 2020; Højlund Madsen, 2021).

This article departs from a Feminist institutionalism perspective (hereafter FI),2 which is rooted in the notion of gendered political institutions that pose obstacles to women's political power “in the informal” (Krook and Mackay, 2011). For one, the gendered political institution is maintained through certain established practices or unwritten rules that exclude or disadvantage women. Furthermore, it is also through gendered norms, such as stereotypes about women's capabilities or roles as politicians, that informal structures and practices are upheld in political institutions. Moreover, this article responds to calls for increasing FI-oriented investigation of women's narratives on political power in less democratic settings (Waylen, 2011).

Drawing on the case study of Turkey, this article addresses the following research questions:

RQ 1: How do the experiences of women MPs illustrate the gendered informal obstacles in the Turkish parliament and which strategies do they seek to navigate these?

RQ 2: How do women MPs' experience and navigation strategies refer to potential implications of Turkey's hybrid regime?

This exploratory study looks at women's experiences of parliament as gendered institutions and, by centering narratives of women MPs, illustrates how they seek different “navigation strategies.” Providing narratives and experiences of women MPs in the Turkish parliament, this article also aims to take into consideration how such “navigation strategies” within gendered parliament reflect the wider context located in a hybrid regime.

Turkey, a hybrid regime moving further away from democratic structures, increasingly shows a gendered nature of its democratic backsliding that impacts women's political participation, women's rights activism, and contested discursive and normative dynamics on the (perceived) role of women in society (Cinar and Kose, 2018; Arat, 2019; Dogangün, 2020; Eslen-Ziya and Kazanoglu, 2022). The empirical data collected and analyzed in this exploratory study is based on qualitative, in-depth interviews with eight women MPs from main governmental and opposition parties in the current legislative (2018–2023) of the Turkish parliament, the Turkish Grand National Assembly (Grand National Assembly of Turkey, 2018; Grand National Assembly of Turkey (TBMM), 2018).3 The study shows that women MPs identify strategies to navigate informal barriers in parliament both individually and collectively. Individual navigation strategies mostly derive from their experiences of being underrepresented in male-dominated parliamentary settings, where for some women MPs embracing their femininities is perceived advantageous, while for others assimilating to the “masculine way of doing politics” is favored. Collective navigation strategies of women MPs in the Turkish parliament illustrate reflections on representing women's interests, seeking women's solidarity in parliament, and the relevance of civil society linkages as strategies to empower women. The study suggests that accounting for the broader context of Turkey's hybrid regime and the increasingly contested gender politics are useful for the differences found in how government and oppositional women MPs illustrate their collective navigation strategies.

Following this introduction, the article proceeds with a review of scholarship on how gendered political institutions form barriers to women's political power in hybrid and authoritarian regimes. Thereafter, the context of the Turkish case is presented followed by a discussion of the research design, data, and method. Subsequently, findings from interviews are presented and discussed in different thematic sections. Finally, the article's main findings, conclusions, and research outlook are presented.

Although women increasingly enter and influence political institutions, such as parliaments, around the world, various formal barriers—for example, socio-economic factors or political recruitment—continue to impact women's experiences of participation in parliaments and other political institutions (Paxton and Hughes, 2015; Inguanzo, 2020). Even once women have entered political decision-making arenas, for example as political leaders or in cabinet positions, gendered barriers continue to persist (Heath et al., 2005).

Yet, as Feminist institutionalism (FI) research emphasizes, it is equally important to consider and investigate the informal barriers to women's political power and their historically long exclusion from political decision-making. Here, FI takes its entry point to understand political institutions as gendered spaces, where “norms, rules and practices are at work within institutions” in formal and informal arenas (Mackay et al., 2010, p. 573), and thereby shape the “rules of the game” that play out on political outcomes, processes, and actor's behaviors (Krook and Mackay, 2011; Bolzendahl, 2017).

Informal structures and practices may refer to prejudices against women in politics, for example, in public opinion or media, or beliefs about women's competency as political leaders (ibid.). Furthermore, cultural traditions and societal norms, such as religion, socialization, or gender norms, may strongly influence perceptions of women as political actors even though variation across country contexts exists. In sum, FI research reveals that gendered structures, practices, and norms pose informal barriers to women's experiences of participation in political institutions (Krook and Mackay, 2011), adding to the various imbalances that persist in male-dominated political decision-making.

Various empirical studies emphasize how women's narratives of gendered political institutions provide relevant entry points to better understand formal and informal gendered structures at play (Rai, 2012; Prihatini, 2019) and how women employ “navigation strategies” to resist, cope, or bring about change—despite or because of their descriptive underrepresentation or “token positions” (Kanter, 1977; Lowndes, 2020; Niklasson, 2020). Yet, an actor-focused analysis is necessary to better understand how women encounter and strategically tackle formal and informal gendered rules of the political game (Mackay, 2011; Lowndes, 2020).

In conceptualizing approaches to study women's navigation strategies in gendered parliament, also as ways to respond, resist, or contribute to institutional change as FI perspectives suggest (Mackay and Waylen, 2014), incorporating individual narratives and experiences into analyses of gendered political institutions is useful. Research on women's political access and negotiation strategies within parliament offers a wide range of empirical cases, such as South Africa or India, to guide the conceptualization of women's individual and collective navigation strategies in gendered parliaments, reaching from gaining political access (Britton, 2001; Prihatini, 2019) to strategies of “everyday” negotiation and learning (Rai, 2012; Corbett and Liki, 2015), to strategic reflections on femininities or masculinities (Niklasson, 2020).

Analyzing the gendered networking of Swedish diplomats, Niklasson (2020) outlines three tendencies among strategies of women diplomats to approach male-dominated, and at times also gender-segregated, settings: first, to strategically embrace the higher visibility as only a few women diplomats; second, to strategically assimilate—either by embracing femininities and women's (perceived) traditional roles or in contrast blending in through a more masculine-oriented networking approach—and, third, women diplomats may also retreat to contrasting strategies to counter dynamics and perceived stereotypical behavior in large male-dominated contexts.

Following Waylen's (2011) call, FI approaches toward studying gender outcomes of democratic transitions in different contexts require further considerations of institutional arenas in the formal and informal, as well as centralizing the role of political actors within institutions and beyond. In hybrid and authoritarian regimes, women in political institutions may experience additional barriers, formal and informal, such as fraudulent election processes or lack of political rights (Tripp, 2013; Højlund Madsen, 2021).

For example, Højlund Madsen's (2021) comparative study on African countries explores how informal institutions serve or counteract underrepresented women in politics within less democratic settings such as hybrid regimes. It is particularly informal structures or institutions, in various forms and at different stages of political processes, that have a significant influence on women's access to and maintenance of political power. Thus, already existent gendered barriers—ranging from unfair candidate selection, tactical misinformation, clientelism, gender stereotypical representation, or gendered electoral violence—may be reinforced.

Moreover, non-democratic regimes also exert influence over women's political power through legitimation strategies, for example, when strategic advances of women's rights are beneficial for gaining voter's support or maintaining authoritarian resilience (Lorch and Bunk, 2016; Mazepus et al., 2016; Donno and Kreft, 2019; Valdini, 2019). More recently, scholarship addresses the different mechanisms of hybrid and authoritarian regimes in instrumentalizing women's rights as “genderwashing” (Bjarnegård and Zetterberg, 2022). Hence, scholarship identifies a range of additional barriers to women's political power in hybrid regimes. While in many such cases, the formal representation of women in political institutions, for example, as MPs in national parliaments, is not restricted as such and may even be supposedly strengthened through gender quotas, the informal barriers to women in politics are all the more worthy of investigation. Here, FI research serves as a crucial entry point, allowing us to concentrate on both how informal barriers to women in parliament occur and take shape, but also—through actively centering women's experiences and accounts—providing insights on women as political actors seek to resist or change the obstacles they experience in the informal barriers (Bolzendahl, 2017).

As the gray zone of hybrid regimes is increasingly more stable around the world, the FI-oriented call to further explore the implications of hybrid regime contexts for the formal and particularly informal obstacles to women's participation in political institutions is urgent (Waylen, 2011; Tripp, 2013; Valdini, 2019). The case study of Turkey's hybrid regime serves as a relevant case study to provide insights into similar hybrid regimes contexts and to better understand contestations surrounding gender politics and its actors (Verloo, 2018). Turkey's democratic backsliding into a hybrid regime encompasses specific implications on the country's gender politics, women's status, and opportunities for participation in politics and civil society. Technically, Turkey is a multi-party system, yet the increasing hegemony of the AKP government and changes to a presidential system resulted in the regime's manifestation of executive and judicial control within a polarized political landscape that suppresses various forms of opposition in civil society, media, academia, or political parties (Center for American Progress, 2017; Kalaycioglu, 2019). In addition to the increasingly questionable status of free and fair elections, the Turkish electoral system characterizes as close list proportional representation (PR system), multi-member districts hindering voter influence on party lists as well as a prevalent culture of strict party discipline (Bulut and Ilter, 2020).

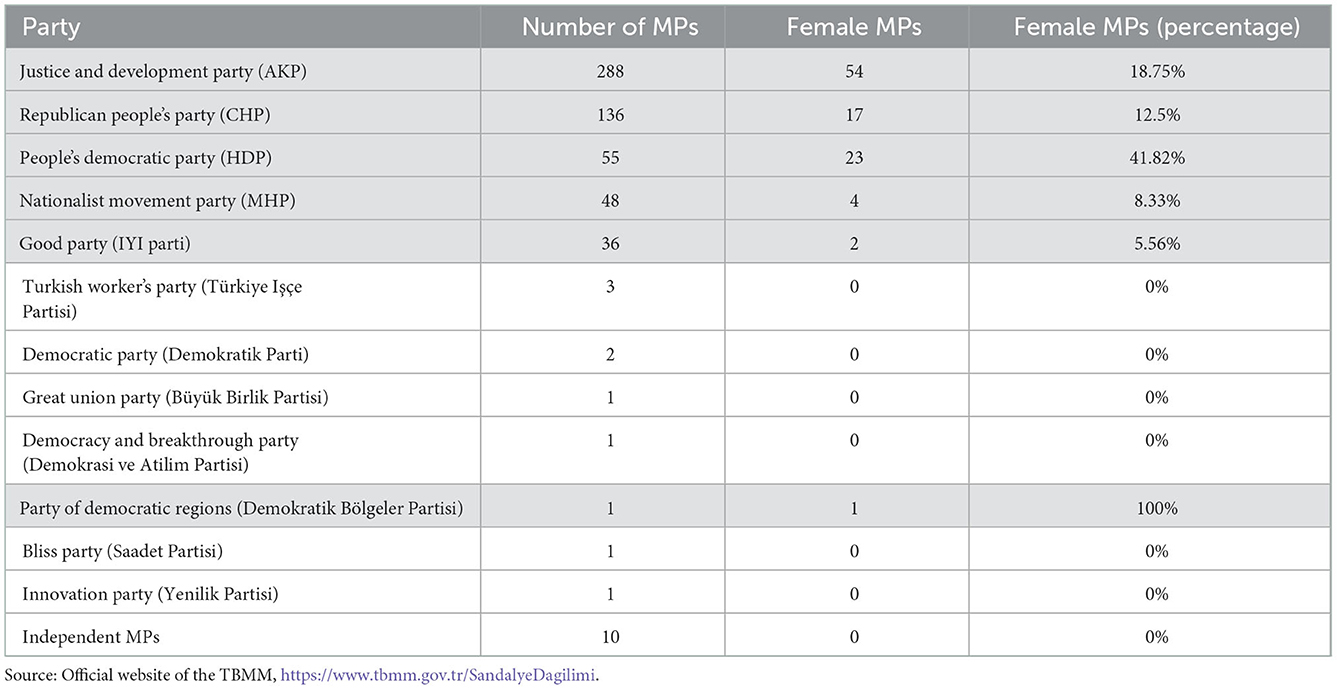

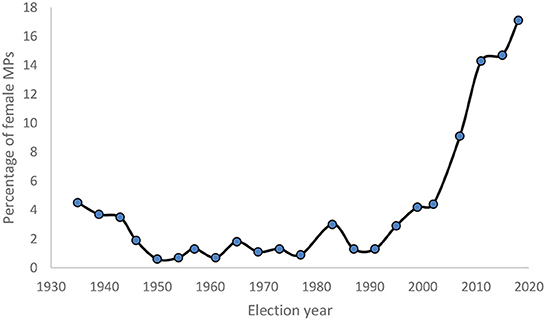

Political decision-making and elected public office in Turkey are continuously and predominantly men's clubs. Despite women's suffrage being granted in the 1930's and long-lasting records of strong women's organizing and mobilization in civil society and women's movements, the path for women's access and political representation remains full of barriers both on the local and national levels (Aydogan et al., 2016; Adak, 2019).4 Currently, as illustrated in Table 1, women stand for 17.3% of MPs in the Turkish Grand National Assembly (TBMM). Yet, historically, Turkey is rather a case of women's political “under-representation” or absence from parliamentary politics, as the percentage of women MPs in the national parliament over time shows in Figure 1. Between 2002 and 2007, women's presence in the Turkish parliament increased from 4.4 to 9.1% (Özdemir, 2018). Following the 2015 general elections, when the Democratic People's Party (HDP) entered the TBMM as a parliamentary group consisting of 40% women MPs, the percentage of women MPs in parliament overall reached a historic peak (Adak, 2019).

Table 1. Overview of women MPs parliamentary parties in the TBMM (current legislative term 2018–2023 after general elections on 24 June 2018).

Figure 1. Women's political representation in Turkey: Percentage of female MPs in TBMM (General elections 1935–2018. Source: Turkish Statistical Institute TURKSTAT, 2021). Available online at: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Istatistiklerle-Kadin-2021-45635.

In the current legislative term of the TBMM (2018–2023), only six out of 13 political parties with parliamentary seats have women MPs. However, it is worth noting that among those political parties without women MPs in the current legislative, most do not constitute a parliamentary group. Among parliamentary parties, the governmental coalition consists of the religious, (neo-) conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) with 18.75% of women MPs, and the right-wing, ethnic Turkish nationalist MPH, the Nationalist Movement Party, with 8.33% of women MPs. In the opposition, the left-wing, pro-Kurdish People's Democratic Party (HDP) with 41.82% and the center-left, Kemalist Republican People's Party (CHP), with 12.5% of female MPs, followed by the liberal, nationalist Good Party (Iyi parti)5 with 5.56%. While Turkey has a voluntary quota for political parties, HDP is the only party that actively practices co-chairmanship (Sahin-Mencutek, 2016).

More than 20 years of the AKP government have impacted the contestations across the intersections of gender politics, civil society activism, and the Turkish political party landscape. Islamist women, along party lines, promote familialism and anti-gender, patriarchal ideas of women's role, and “gender justice” (Diner, 2018; Adak, 2021), while secular feminists understand that women's rights and gender equality is under threat (Simga and Goker, 2017; Çağatay, 2018). Women's activism in a civil society increasingly reflects these discursive and ideological oppositions (Aksoy and Gambetta, 2021; Eslen-Ziya and Kazanoglu, 2022).

These divisions are also evident within parliamentary settings. Women within AKP party structures, including in political leadership positions or women's auxiliaries, are important channels of how Islamist populism of the AKP is forwarded through discourse and policy debates (Ayata and Tütüncü, 2008a). In addition to gender imbalances in parliamentary speeches (Konak Unal, 2021), Bektas and Issever-Ekinci (2019) find notable differences among parliamentary bill sponsorship: while left-wing women MPs in the Turkish parliament tend to sponsor more bills on women's rights and gender equality issues, including health and social affairs, indicating feminist claims, right-wing women MPs tend to prioritize sponsoring bills on children and family issues.

Since the latest national elections on 24 June 2018, currently, 104 women MPs out of 600 members hold elected office in the TBMM, which stands for 17.33% of women's political representation in the national parliament (Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), 2021). While longitudinal analyses of Turkey's political parties demonstrate significant changes and differences toward women's issues (Kabasakal Arat, 2017), all parties give attention to women's rights and issues, though with some variation. However, while conservative, religious, and nationalist parties tend to combine traditionalism with gender equality (or rather, “gender justice”), a more feminist-oriented terminology of women's issues is displayed by social democrat, socialist, and pro-Kurdish parties in the Turkish political landscape (Kabasakal Arat, 2017; Bektas and Issever-Ekinci, 2019). Women continue to be underrepresented in the majority of committees, such as security, intelligence, or defense (Alemdar, 2018). The Committee on Equality of Opportunity for Women and Men (KEFEK)6 currently consists of a total of 26 MPs: four male MPs and 22 female MPs.

This qualitative, exploratory study draws on in-depth semi-structured interviews with eight female national MPs. The interviewees responded to interview questions based on an interview guide that focused on (1) their background and political career, (2) barriers to women's political representation in Turkey, (3) their experiences as female MPs in male-dominated political decision-making, (4) defining representation of “women's interests,” and (5) linkages between women MPs and women's organizations/women's movement. Although the interview guide encompasses a wider range of topics, in this study, not all topical sections of the interview guide are in focus. For example, the topical sections of the interview guide focusing on personal information and entry to a political career were mostly approached as background information toward better-situating narratives and experiences of interviewees, yet not as central components of this study.

Interviews were conducted in two distinct phases with the first phase of interviews conducted in January and February 2020 in Ankara, Turkey. As the emergence of the global COVID-19 pandemic affected data collection in various ways, interviews were postponed and continued in a digital format (Zoom) in a second phase in December 2020, as well as one additional interview in April 2021. All interviews, whether conducted physically or digitally, were held in English and with a Turkish interpreter present to translate during conversations. On average, the interviews lasted around 1 h, yet in three cases, interviews continued longer up to 1.5–2 h. Given the interviewees' consent, all interviews were audio-recorded and transcripts were translated from Turkish into English afterward. The analysis is based on the interview transcripts in English but takes into consideration relevant expressions, references, or proverbs in Turkish original.7 All interviewees are presently elected MPs in the Turkish national parliament during the legislative term 2018–2023 (Table 2). Out of them, four interviewees already were elected MPs during an earlier legislative period and hence serve in their second legislative term. For the other four interviewees, the current is their first legislative term as MP. Despite different party affiliations, the eight interviewees share similar backgrounds: all are university graduates and have been working in non-political professions for some time before or while becoming politically involved. Except for two interviewees, all interviewed women have an existent political path within their respective party before their current election as MP in the national Turkish parliament—in committee functions, on the municipal or regional level, experience in the party's youth or women's branch, or all of the aforementioned. The two interviewed women MPs from HDP, the pro-Kurdish party, explicitly describe themselves as women's rights activists rather than politician, as they see being an MP as just another channel of activism.

Before commencing interviews, possible interview participants8 were approached through email and phone correspondence with their parliamentary offices on multiple occasions to introduce the research and inquire about the respective MPs' possible participation. The initial list of potential interviewees for this study included all female MPs from the five parliamentary parties that have female deputies. Finally, female MPs from three parties (AKP, CHP, and HDP) agreed to participate in the study. To protect their confidentiality, interview participants in this study are kept anonymous.

Interviews are analyzed using narrative analysis, where narratives of women MP's personal experiences are centered (Rai, 2012) and approached by various levels of representation of these experiences in the research and analysis process, such as attending, telling, transcribing, analyzing, and reading (Kohler Riessman, 1993; Squire et al., 2014). Following Lieblich et al. (1998), analysis of women MP's personal experiences followed a categorical-content model that studies pre-defined topics or thematic sections within narratives. In this study, previous research guided definitions of thematic sections focusing on (1) parliament as a gendered institution, (2) interviewees' experiences of barriers to political power, and 3) strategies for change, resistance, and navigation.

Women MPs in the Turkish parliament do not experience formal barriers to their participation; however, their narratives are a rich illustration of how informal structures, practices, and norms permeate their experiences of parliamentary politics as an uneven playing field (Ayata and Tütüncü, 2008b; Krook and Mackay, 2011).

“Today, female representation [in parliament] is 17%, which is very low. […] Men make decisions about women's rights. We [women MPs] being in a minority puts us in a difficult position when they [male MPs] vote and make decisions about us, we also face the difficulty of convincing them.” (MP 5, CHP)

Their experiences illustrate that “we [female MPs] are not able to do politics under the same condition as men” (MP 1, CHP) and reflect the challenges of navigating gendered informal barriers within an overwhelmingly male-dominated institution (Corbett and Liki, 2015; Lowndes, 2020). Evidently, “men dominate policy-making mechanisms in Turkey” (MP 4, AKP) and the “country is run by men” (MP 6, HDP). Thus, not surprisingly, one interviewee reflects that “it requires a transhuman performance for women to participate in politics. They need to be stubborn.” (MP 6, HDP).

Throughout interviews, women MPs share both individual as well as more collectively oriented strategies to navigate the various informal obstacles to their parliamentary participation. Across the different stories of individual navigation strategies presented by the interviewed women MPs in the Turkish parliament, the preeminence of gender norms posing as informal barriers to women's access and influence in parliamentary politics is substantial (Krook and Mackay, 2011; Bolzendahl, 2017; Niklasson, 2020). Although in similar ways, all interviewed women MPs tend to describe their experiences as a woman in Turkish parliament as consistently stemming from their always underrepresented position in a male-dominated sphere. Yet, these narratives are connected to gender norms in different ways and do, at times, coexist (Corbett and Liki, 2015). For example, interviews reveal that, individually, women MPs have different ways of positioning themselves within or against gender norms and stereotypical assumptions on “how politics works.” At the same time, the stories of women MP's navigation strategies to informal barriers are not reflective of the normative contestations between government and opposition in Turkish politics, as is the case in more collective navigation strategies.

For some of the interviewees, the means to navigate the informal obstacles that gender norms in their everyday experience in parliament play is to embrace and display their feminine or “women-first” identities (Niklasson, 2020). Rather than assimilating with the dominant “masculine way of doing politics,” “what is important is running in the politics, fighting and never ever stepping back, but to have a determined and female point of view, without becoming “mannish”' (MP 1, CHP).

Similarly, some women MPs perceive that in certain situations, for example, in traditional family settings or on gender-sensitive issues, their greater visibility as a female politician is advantageous, such as in contexts where women can be granted easier access compared to men: “we [women] go into the families, we sit together with mothers, with the children” (MP 4, AKP). For some of the interviewees, strategically using the position of being a women MP in male-dominated parliament is an advantage:

“So sometimes, when you say something as a woman sitting at the [decision-making] table with men, men can be more respectful. They try to be politer, more thoughtful” (MP 2, CHP)

For other interviewees, individual strategies connecting to assimilation derive from the perception that downplaying femininities and, instead, embracing a more masculine way of doing politics is more successful when facing gendered informal obstacles in parliament. However, it also acknowledges that women in politics, as elsewhere in society, carry a “double burden”:

“[For women] it is maybe like learning to speak Chinese, we [women] need to be able to learn and make ourselves encountered [with the male way of working in parliament] because there will always be people doubting you” (MP 4, AKP).

Similarly, women MPs may acknowledge how women seeking political power face obstacles resulting from gender inequalities characteristic of the political game, but still embrace a more masculine approach like:

“I worked as a man all the time. Actually, I worked more than all the men all the time. Because when they were doing something, doing one thing, I worked on three things at the same time” (MP 2, CHP).

Finally, some interviews also describe how gender stereotypes and discourses occur as informal obstacles to navigate in parliamentary settings (Corbett and Liki, 2015; Sumbas, 2020).

“women [MPs] are exposed to mobbing in politics […] People criticize us for our looks, gender and our bodies. They don't critique what we say. All these obstacles prevent us [women] from getting and being in politics” (MP 6, HDP).

The narratives attest that women MPs in the Turkish parliament are confronted with such experiences of stereotypes, sexism, or violence against women in politics particularly in informal settings. While one of the interviewees describes her strategy to navigate such encounters, for example, sexist language, in direct resistance as “the feminist control officer” (MP 3, HDP), overall narratives tend to indicate less confrontative strategies on the individual level.

From a more collective perspective, divergences between governmental women MPs and oppositional women MPs in navigating parliament and informal barriers are more apparent. For one, these divergences between government and opposition are to be seen as a reflection of the increased political and ideological polarization in Turkey's hybrid regime transformation under the neo-conservative AKP government, all the while the continuous tradition of strong party discipline in Turkey's parliamentary politics is evident (Ayata and Tütüncü, 2008a; Bektas and Issever-Ekinci, 2019). Additionally, considering the wider context of Turkey's hybrid regime and the dynamics intersecting the arena of gender politics, its actors and normative discourses, differences in narratives of oppositional and governmental women MPs are evident (Adak, 2019; Taskin, 2021).

In interviews, this is illustrated, for example, by contrasting approaches to representing “women's issues” in a male-dominated parliament, where governmental women MPs attribute collective strategies to the paradigm, promoting traditional gender norms and valuing family and women's role within Turkish society: “in order to get more men to engage in these “women's issues”, we need to remind them who these women are. Their mothers, their wives, their daughters.” (MP 8, AKP).

Yet, in stark contrast is the understanding of representing “women's voices,” which oppositional women MPs convey in their narratives of collective strategies. As one interviewee from the oppositional party (CHP) describes, considering women's overall parliamentary underrepresentation, acting as representatives of women's issues is also a matter of defending gender equality policies, such as the Istanbul Convention—even when it entails opposing other, governmental women MPs:

“Let's look at today's Turkish parliament […] democracy is not functioning properly due to inequality of female representation. […] If there were 300 female MPs out of the 600 MPs in total, there would be so much public pressure to solve women's problems. Nobody could have mentioned about [withdrawing from] the Istanbul Convention. Women from the AKP know this and their awareness on the convention is very high. They know this convention protects them, too.” (MP 7, CHP)

Stemming from their oppositional positioning within the Turkish party landscape and within parliament, the narratives from these interviewed women MPs are more explicitly alluding to aspects of the Turkish hybrid regime context where clashes between women from the government and opposition occur.

“There was this Las Tesis dance we [CHP] did in the assembly. And when we did that, [it was] more the women from AKP yelling [at us] than the men. So, when we were performing Las Tesis, more women from AKP showed [negative] reactions than men. I cannot understand them.” (MP 2, CHP)

The interviewee refers to the CHP-led protest in parliament in December 2019, where oppositional women MPs together with allied male MPs performed the Chilean “Las Tesis” song protesting Turkey's femicide issue and accused the government of failing to prevent violence against women. What both narratives of CHP women MPs indicate is that they experience the reluctance and inaction of women from the governmental party to address and represent such women's issues as a sign of the contestations around gender politics, which has been characteristic of the Turkish hybrid regime context over the past years (Diner, 2018; Adak, 2019).

While interviews bring attention to how women MPs in the Turkish parliament employ various, more collectively oriented navigation strategies toward the largely informal barriers they experience in parliament, narratives also suggest that differences are evident between how women from the government compared to oppositional women MPs describe these strategies in relation to creating better opportunities for women's political power or institutional change (Britton, 2001; Waylen, 2011).

Differences among governmental and oppositional women MPs on more collectively oriented navigation strategies are also apparent in the approaches to women's solidarity in parliament described. Despite their overall consent on experiences of informal gendered barriers as part of women MPs' parliamentary experiences, party affiliation, and related positioning on gender norms play a role in how collective strategies to creating women's solidarity in parliament are articulated differently between government and opposition sides (Britton, 2001; Sumbas and Dinçer, 2022).

Referring to an anecdotal example to illustrate experiences of gendered, informal practices in parliament, one interviewee shares “they appoint a less experienced woman for a position and when she fails, they say 'She couldn't do the job‘” (MP 4, AKP). Interviewees from the governmental party emphasize how they approach strengthening women's influence particularly through women's branches within the party and as collective strategies to counteract informal obstacles—such as the previously mentioned example where a selected female MP is “set up to fail.” Thus, women's networks in the parties can serve as a collective space where women MPs “both have the political experience and [receive] the support that helps them work in assembly” (MP 4, AKP).

In comparison, interviewees from the oppositional parties reflect on approaches to women's solidarity in parliament from perspectives that go beyond the own party, or even oppositional coalition, lines and perceive commonalities among women MPs and, more broadly, women in Turkish society. While it does not indicate that internal mechanisms, such as women's networks, do not exist within opposition parties, the narratives of opposition women MPs rather emphasize that they perceive cross-party cooperation among women MPs as more relevant means to create women's solidarity. Not the least, in order to “[defend] women's rights, to be on the women's side and defending them is important. We are their voice in the parliament” (MP 3, HDP). Moreover, these interviewees also provided examples of when such cross-party cooperation was successful despite otherwise contested party positions between government and opposition, such as violence against women policies or the early child marriage issue.

At the same time, this finding of divergent approaches to women's solidarity in parliament reflect also the polarized positions of governmental and oppositional sides in Turkey's hybrid regime context, where women's (rights) issues and gender norms have been instrumentalized as mechanisms to promote regime legitimacy, but even more importantly, are contested issues reflective of de-democratization (Eslen-Ziya and Kazanoglu, 2022). In addition, it may not necessarily be possible to conclude whether the divergent approaches to women's solidarity are direct results of the Turkish hybrid regime context per se. However, these narratives allow the conclusion that, within such a context, oppositional women MPs may perceive greater incentives to understand their approaches to solidarity within and beyond parliamentary and institutional settings and also as strategic choices of resistance and countering the incumbent regime's political and normative influence (Waylen, 2011; Højlund Madsen, 2021).

Promoting women's empowerment within and beyond formal, parliamentary settings identifies as another layer of collective navigation strategies of interviewed women MPs in the Turkish parliament. Similar to the illustrations of solidarity within parliament, differences between government and opposition women MPs are also more prominent in narratives on how collective navigation strategies incorporate linkages with civil society. It is particularly the women MPs from the opposition that emphasize such strategic linkages, for example, with women's organizations, in regard to Turkey's hybrid regime context. While the women MPs from the governing party also have indicated that linkages to civil society are an important aspect for advancing women's empowerment, their narrative has mostly focused on civil society and women's organizations for consultative dialogs in policy-making processes, for example, on the Istanbul Convention (MP 3, AKP), as well as increasing the visibility of women MPs in Turkey.

In narratives of the oppositional women MPs in this study, they portray such linkages as crucial for strategically promoting institutional change or resistance to gendered barriers in politics (Højlund Madsen, 2021) and connect it to the broader struggle of advancing women's rights: “we are putting an effort to empower and support the structures that fight for women and are actively involved in advancing women's struggle” (MP 1, CHP).

Another interviewee emphasizes that linkages between women MPs and civil society, including the women's movement, are important mechanisms to strengthen women's political power, describing that, “the reason I dared to be in politics is that there is a women's movement in the party and it supports me […] As a feminist MP, I defend their rights and bring their voice to assembly” (MP 3, HDP). Similarly, another interviewee reasons that collectively, as women MPs, strengthening women's empowerment also goes beyond parliamentary politics and in particular with civil society and the women's movement:

“I don't think that women, especially in the women's movement, are very effective or very powerful […] because of the unfortunate situation in Turkey where the current (government) of the country has closed the democratic channels, and because of the obstacles they have put in front of the women's movement. I am especially considering my own political background, coming from civil society and active in the women's movement (…) (MP 1, CHP)

In sum, the narratives of women MPs in the Turkish parliament do not suggest that differences between government and opposition refer to whether linkages with civil society, beyond the parliament, are perceived of different value or importance for women MPs as such. On the contrary, all interviewed women MPs from government and oppositional parties believe that creating and maintaining fruitful relations with civil society, particularly also women's organizations, is a vital part of being a representative.

However, what the interviews illustrate is that the “women's empowerment” narrative is much more a collective strategy sought by women MPs from the opposition, who themselves tend to have a personal background coming from civil society activism before joining formal politics. In their perceptions, linkages with civil society are relevant in the array of navigation strategies to informal barriers in the Turkish parliament, because it allows them to mobilize and resist authoritarian mechanisms that instrumentalize gender politics and women's rights and as ways to promote institutional change in a gendered Turkish parliament (Tripp, 2013; Bjarnegård and Zetterberg, 2022).

This exploratory study, drawing on the case study of Turkey's hybrid regime, has examined how women MPs in the current legislative encounter and strategically navigate informal obstacles in parliament. Moreover, centering the experiences of women MPs from both government and opposition, the study explored to what extent such navigation strategies may be reflective of the implications posed by the Turkish hybrid regime setting.

Departing from a FI approach to studying women's experiences of parliamentary participation and the gendered, informal barriers women face has proven useful for grasping the complex, dynamic encounters, positionings, and strategic choices that inform different navigation strategies of women MPs in the Turkish parliament (Krook and Mackay, 2011; Højlund Madsen, 2021). Narratives of women MPs in the Turkish case illustrate how navigating—both individually and collectively—informal practices, norms, discourses, and unwritten rules is an essential element of women's efforts in parliament to gain access and influence, despite being largely underrepresented. Individually, women MPs describe that in an uneven playing field of parliamentary politics, as in Turkey, their navigation strategies are particularly a strategic juggling along various gender norms. While for some this reflects assimilation to a “masculine” way of doing politics, for others embracing femininities has proven strategic advantages in overwhelmingly male-dominated parliament (Corbett and Liki, 2015; Niklasson, 2020).

Women MPs also illustrate the variety of collective, strategic approaches that support them in navigating informal barriers in the Turkish parliament. Here, the normative divergences, which have characterized Turkey's de-democratization coupled with an increased interference with gender politics (Adak, 2019; Eslen-Ziya and Kazanoglu, 2022), are most apparent in how women MPs describe their understanding of representing women's interests. What oppositional women MPs believe is representing women's voices in parliament, is entailing government MP's emphasis on representing women's interests.

The study also points to differences among women MPs from government and opposition in their narratives of other collective-oriented navigation strategies. For example, as internal mechanisms to strengthen women MPs in the governmental party are emphasized, the oppositional accounts rather point out the relevance of fostering cross-party alliances. Similar illustrations are evident in how governmental and oppositional women MPs diverge in approaching civil society linkages to empower women as other forms of navigation.

Overall, it is worth considering to what extent these divergences are reflective of the broader Turkish hybrid regime context. In the recent years of Turkey's de-democratization, the increasingly anti-gender, neo-conservative turn in Turkish politics, both on the discursive-normative level and with very concrete targeted actions, such as co-optation of women's organizations, undoubtedly plays a role in how women MPs approach their parliamentary responsibilities of representing women (Yabanci, 2019; Dogangün, 2020). At the same time, some of the government and opposition divergences in collective navigation strategies, for example, linkages with civil society, are not to be taken as direct consequences of the Turkish regime context. However, what narratives indicate is that women MPs from the Turkish opposition parties do more strongly present their collective navigation strategies also as mechanisms of resistance aimed toward institutional, political change (Krook and Mackay, 2011; Arat, 2019; Højlund Madsen, 2021).

Women's political participation is likely to be continuously embedded in contexts that inhibit contestations between gender equality and anti-gender norms, or where in the stable gray zone of hybrid regimes, gender politics, and women's participation faces risks of instrumentalization (Valdini, 2019; Bjarnegård and Zetterberg, 2022). As such, the Turkish case illustrates valuable insights into how women MPs, across party positions and power dynamics, seek to navigate both the gendered political institution and parliament. Future research may take this study—and portrayals of women MPs navigating informal barriers in parliament—as a departure point to further study the gendered obstacles to women's political participation and the additional implications that hybrid regimes constitute for gender politics at large (Waylen, 2011; Tripp, 2013; Verloo, 2018).

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

This research was funded by the Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul (SRII), the Swedish Network for European Studies in Political Science (SNES), and the Theodor Adelswärd Foundation.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.1075462/full#supplementary-material

1. ^Report “Women in parliament in 2020. The year in review”, IPU 2021 (https://www.ipu.org/women-in-parliament-2020) and monthly IPU ranking of women in national parliaments, latest 1 April 2021 (https://data.ipu.org/women-ranking?month=4&year=2021).

2. ^For an overview of most used abbreviations in this paper, see Appendix A.

3. ^Political parties with parliamentary seats in current legislative (2018–2023) and percentage of female MPs (https://www.tbmm.gov.tr/develop/owa/milletvekillerimiz_sd.dagilim).

4. ^The share of women's seats in the Turkish national parliament in global comparison, see the Inter-Parliamentary Union's monthly ranking on women in national parliaments: https://data.ipu.org/women-ranking?month=11&year=2022Monthly ranking of women in national parliaments | Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (last updated November 2022).

5. ^The Good Party (IYI party) was formed by moderate MHP cadres following a split within the party over supporting Erdogan after the 2017 referendum (Esen and Yardimci-Geyikçi, 2020). Following the oppositional alliance with CHP, while leading to the upcoming planned general elections in 2023, the oppositional alliance is increasingly involved with several smaller, new, and splinter parties such as the Future Party, the Democrat Party, or (DEVA) the Democracy and Progress Party (Celep, 2021; Kocadost, 2022).

6. ^KEFEK (Turkish: Kadin Erkek Firsat Eşitligi Komisyonu) was established in 2009. See: https://komisyon.tbmm.gov.tr/komisyon_index.php?pKomKod=865.

7. ^While this study is of an exploratory nature, the interview sample is limited and in addition to the practical barriers to this fieldwork (such as the COVID-19 pandemic), the potential influence of selection bias is worth to reflect on. As a researcher of foreign nationality conducting fieldwork in a politically sensitive context such as Turkey, the lower response rate among women MPs from governmental parties could also partly be due to being perceived as a “threat”. The researcher noted a hesitancy among government party women MPs who were contacted but decided to not participate in interviews. Yet, most rejected interview requests were referring to lack of MP's time availability. Three women MPs, one each from AKP, CHP, and HDP, offered to participate in interviews by email format, yet due to potentially limited data available, the researcher rejected this offer.

8. ^Initially, the whole number of women MPs in the current legislative term (2018–2023) was prioritized to those women MPs across parties who are represented in KEFEK or work on, broadly defined, political issues concerning women and/or gender equality/gender justice. All women MPs across parties were contacted with inquiries for participation in interviews for this study. At a later stage of the fieldwork, it was considered to expand the list of potential interviewees to all remaining women MPs; however, due to practical barriers with fieldwork, this was not followed.

Adak, S. (2019). “Gender politics and the women's movement,” in The Routledge Handbook of Turkish Politics, eds A. Özerdem and M. Whiting (New York, NY: Routledge), 315–327.

Adak, S. (2021). Expansion of the diyanet and the politics of family in Turkey under AKP rule. Turkish Stud. 22, 200–221. doi: 10.1080/14683849.2020.1813579

Aksoy, O., and Gambetta, D. (2021). The politics behind the veil. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 37, 67–88. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcaa035

Alemdar, Z. (2018). Women Count Turkey 2018. Turkey's Implementation of UNSCR 1325. Report published by Operation 1325, Stockholm.

Alvarez, S. (1999). Advocating feminism: the Latin American feminist NGO boom. Int. Fem. J. Polit. 1, 181–209. doi: 10.1080/146167499359880

Arat, Y. (2019). Beyond the Democratic Paradox: The Decline of Democracy in Turkey. GLD Working Paper 21, Program on Global Local Development, University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

Ayata, A. G., and Tütüncü, F. (2008a). Party politics of the AKP (2002–2007) and the predicaments of women at the intersection of the Westernist, Islamist and feminist discourses in Turkey. Br. J. Middle Eastern Stud. 35, 363–384. doi: 10.1080/13530190802525130

Ayata, A. G., and Tütüncü, F. (2008b). Critical Acts without a critical mass: the substantive representation of women in the Turkish parliament. Parliam. Aff. 61, 461–475. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsn012

Aydogan, A., Marshall, M., and Shalaby, M. (2016). Women's Representation across National and Local Office in Turkey. Washington, DC: Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS); Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy. POMEPS Studies 22, Contemporary Turkish Politics, 42–47.

Bektas, E., and Issever-Ekinci, E. (2019). Who represents women in Turkey? an analysis of gender difference in private bill sponsorship in the 2011–15 Turkish parliament. Polit. Gender 15, 851–881. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X18000363

Bjarnegård, E., and Zetterberg, P. (2022). How autocrats weaponize women's rights. J. Demo. 33, 60–75. doi: 10.1353/jod.2022.0018

Bolzendahl, C. (2017). “Legislatures as gendered organizations: challenges and opportunities for women's empowerment as political elites,” in Measuring Women's Political Empowerment Across the Globe: Strategies, Challenges, and Future Research, eds C. Bolzendahl, F. Jalalzai, and A. Alexander (Springer International Publishing).

Britton, H. (2001). New struggles, new strategies: emerging patterns of women's political participation in the South African Parliament. Int. Polit. 38, 173–200. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ip.8892570

Bulut, A., and Ilter, E. (2020). understanding legislative speech in the Turkish parliament: reconsidering the electoral connection under proportional representation. Parliam. Aff. 73, 147–165. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsy041

Çağatay, S. (2018). Women's coalitions beyond the laicism-islamism divide in Turkey: Towards an inclusive struggle for gender equality? Social Inclus. 6, 48–58.

Celep, Ö. (2021). A contemporary analysis of intra-party democracy in Turkey's political parties. J. Balkan Near Eastern Stud. 23, 768–794. doi: 10.1080/19448953.2021.1935069

Center for American Progress (2017). “Trends in Turkish Civil Society”, Report Published By the Center for American Progress, Istanbul Policy Center, and Istituto Affari Internazionali, July 2017. Available online at: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/security/reports/2017/07/10/435475/trends-turkish-civil-society/ (accessed October 15, 2022).

Childs, S., and Lovenduski, J. (2013). “Political representation,” in The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Politics, eds G. Waylen, K. Celis, J. Kantola, and L. S. Weldon (Oxford; New York, NY: University Press).

Cinar, K., and Kose, T. (2018). The determinants of women's empowerment in Turkey: a multilevel analysis. South Eur. Soci. Polit. 23, 365–386. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2018.1511077

Corbett, J., and Liki, A. (2015). Intersecting identities, divergent views: interpreting the experiences of women politicians in the pacific islands. Polit. Gender 11, 320–344. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X15000057

Dogangün, G. (2020). Gender climate in authoritarian politics: a comparative study of Russia and Turkey. Polit. Gender 16, 258–284. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X18000788

Donno, D., and Kreft, A. K. (2019). Authoritarian institutions and women's rights. Comp. Polit. Stud. 52, 720–753. doi: 10.1177/0010414018797954

Esen, B., and Yardimci-Geyikçi, S. (2020). The Turkish presidential elections of 24 June 2018. Mediterr. Politics 25, 682–689. doi: 10.1080/13629395.2019.1619912

Eslen-Ziya, H., and Kazanoglu, N. (2022). De-democratization under the New Turkey? Challenges for women's organizations. Mediterr. Politics. 27, 101–122. doi: 10.1080/13629395.2020.1765524

Grand National Assembly of Turkey (2018). The Committee on Equality of Opportunity for Women and Men (KEFEK), Official website. Available online at: https://komisyon.tbmm.gov.tr/komisyon_index.php?pKomKod=865

Grand National Assembly of Turkey (TBMM) (2018). Available online at: https://www.tbmm.gov.tr/develop/owa/tbmm_internet.anasayfa (accessed October 15, 2022).

Heath, R., Schwindt-Bayer, L. A., and Taylor-Robinson, M. M. (2005). Women on the sidelines: Women's representation on committees in Latin American legislatures. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 49, 420–436. doi: 10.1111/j.0092-5853.2005.00132.x

Højlund Madsen, D. (2021). Gendered Institutions and Women's Political Representation in Africa. London: Zed Books.

Ilonszki, G., and Vajda, A. (2019). Women's substantive representation in decline: the case of democratic failure in hungary. Polit. Gender 15, 240–261. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X19000072

Inguanzo, I. (2020). Asian women's paths to office: a qualitative comparative analysis approach. Contemporary Polit. 26, 186–205. doi: 10.1080/13569775.2020.1712005

Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) (2021). Women in Parliament: Monthly ranking – Turkey. Available online at: https://data.ipu.org/women-ranking?month=4andyear=2021 (accessed April 1, 2021).

Kabasakal Arat, Z. F. (2017). Political parties and women's rights in Turkey. Br. J. Middle Eastern Stud. 44, 240–254. doi: 10.1080/13530194.2017.1281575

Kalaycioglu, E. (2019). “Elections, parties, and the party system,” in The Routledge Handbook of Turkish Politics, eds A. Özerdem, M. Whiting (New York, NY: Routledge), 83–102.

Kanter, R. M. (1977). Some effects of proportions on group life: skewed sex ratios and responses to token women. Am. J. Sociol. 82, 965–990.

Kocadost, B. (2022). Authoritarianism: the need for a democratic alliance in Turkey. Lab. Organ. Author. Regimes 26, 41. doi: 10.5771/9783957104090-41

Konak Unal, S. (2021). The role of gender in Turkish parliamentary debates. Turkish Stud. 22, 530–557. doi: 10.1080/14683849.2020.1838281

Krook, M., and Mackay, F. (2011). Gender, Politics and Institutions. Towards a Feminist Institutionalism. Basingstoke; New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., and Zilber, T. (1998). Narrative Research: Reading, Analysis, and Interpretation, Vol. 47 (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage).

Lorch, J., and Bunk, B. (2016). Gender Politics, Authoritarian Regime Resilience, and the Role of Civil Society in Algeria and Mozambique (October 15, 2016). GIGA - German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Working Paper No. 292. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2863764

Lowndes, V. (2020). How are political institutions gendered?. Polit. Stud. 68: 543–564. doi: 10.1177/0032321719867667

Mackay, F. (2011). “Conclusion: towards a feminist institutionalism, in Gender, Politics and Institutions. Towards a Feminist Institutionalism, eds M. L. Krook and F. Mackay (Basingstoke; New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan).

Mackay, F., Kenny, M., and Chappell, L. (2010). New Institutionalism through a gender lens: towards a feminist institutionalism? Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 31, 573–588. doi: 10.1177/0192512110388788

Mackay, F., and Waylen, G. (2014). Introduction: gendering 'new‘ institutions”, Polit. Gend. 10, 489–494. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X14000385

Mazepus, H., Veenendaal, W., McCarthy-Jones, A., and Trak Vásquez, J. M. (2016). A comparative study of legitimation strategies in hybrid regimes. Policy Studies 37, 350–369. doi: 10.1080/01442872.2016.1157855

Niklasson, B. (2020). The gendered networking of diplomats. Hague J. Diplo. 15, 13–42. doi: 10.1163/1871191X-BJA10005

Özdemir, E. (2018). Gender equality and women's political representation in Turkey. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 5, 558–568 doi: 10.14738/assrj.510.5478

Paxton, P., and Hughes, M. (2015). Women, Politics and Power. A Global Perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA; London; New Delhi; Singapore: Sage.

Prihatini, E. (2019). Women's views and experiences of accessing national parliament: evidence from Indonesia. Women's Stud. Int. Forum 74, 84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2019.03.001

Rai, S. (2012). The politics of access: narratives of women MPs in the indian parliament. Polit. Stud. 60, 195–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00915.x

Sahin-Mencutek, Z. (2016). Strong in the movement, strong in the party: women's representation in the Kurdish party of Turkey. Polit. Stud. 64, 470–487. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12188

Simga, H., and Goker, G. Z. (2017). Whither feminist alliance? Secular feminists and Islamist women in Turkey. Asian J. Women's Stud. 23, 273–293. doi: 10.1080/12259276.2017.1349717

Squire, C., Davis, M., Esin, C., Andres, M., Harrison, B., Hydén, L., et al. (2014). What is Narrative Research? New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic.

Sumbas, A. (2020). Gendered local politics: the barriers to women's representation in Turkey. Democratization 27, 570–587. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2019.1706166

Sumbas, A., and Dinçer, P. (2022). The substantive representation of women parliamentarians of the AKP: The case of maternity leave and part-time work. Politics Groups Identities. 10, 146–151.

Taskin, B. (2021). Political representation of women in Turkey: institutional opportunities versus cultural constraints. Open Gender J.

Tripp, A. M. (2013). “Political systems and gender, in The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Politic, eds G. Waylen, K. Celis, J. Kantola, and L. S. Weldon (Oxford; New York, NY: University Press).

Valdini, M. E. (2019). The Inclusion Calculation: Why Men Appropriate Women's Representation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Waylen, G. (1994). Women and democratization: conceptualizing gender relations in transition politics. World Polit. 46, 327–354. doi: 10.2307/2950685

Waylen, G. (2011). “Gendered Institutionalist analysis: understanding democratic transitions,” in Gender, Politics and Institutions. Towards a Feminist Institutionalism, eds M. L. Krook, F. Mackay (Basingstoke; New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan).

Keywords: women's representation, gendered parliament, navigation strategies, Turkey, de-democratization

Citation: Ehrhart A (2023) Navigating underrepresentation and gendered barriers to women's political power: Narratives and experiences of women parliamentarians in Turkey. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:1075462. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.1075462

Received: 20 October 2022; Accepted: 22 December 2022;

Published: 16 January 2023.

Edited by:

Régis Dandoy, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, EcuadorReviewed by:

Tevfik Murat Yildirim, University of Stavanger, NorwayCopyright © 2023 Ehrhart. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anna Ehrhart,  YW5uYS5laHJoYXJ0QG1pdW4uc2U=

YW5uYS5laHJoYXJ0QG1pdW4uc2U=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.