- 1Research Group Gaspar, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

- 2Research Group Cevipol, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium

Many Western parties have opened up the process of leadership selection to party members under the noble premises to democratize the party. Yet, this might just be window-dressing as party leadership selection is often a coronation rather than an open contest. We argue that the preparation phase preceding the actual election phase is crucial in understanding the balance between the impact of party members and the steering of the party elite. This study compares the preparation phase of two leadership contests after losing elections in one party, the Flemish Christian-democratic party in Belgium: one with a single candidate and one with an exceptionally high number of candidates. Our analysis, based on 22 in-depth elite interviews, demonstrates that leadership elections are influenced by a cluster of different influencing actors, but in particular by what we label the “last person standing” whose candidacy is identified as the most effective mechanism to influence the nomination process. Other (slightly less effective) influencing mechanisms include encouragements, discouragements and the diffusion of an ideal profile for the future party leader.

1. Introduction

Party leaders occupy a central place in Western democracies: they personify the party organization and are in practice the ones who exert great influence on most important decisions in the party, and even in government and parliament (LeDuc, 2001; Poguntke and Webb, 2005). This is especially the case in Belgium, generally labeled as a “partitocracy” (De Winter and Dumont, 2003; Deschouwer, 2009). Hence, the election of a new leader is one of the most important decisions a Belgian party takes. This throws up the questions of who decides on the new party leader and which mechanisms steer this process.

On paper, party members have become more important in this matter as parties in Western democracies increasingly involve them in the selection of their leaders (Pilet and Cross, 2014). But at the same time, the number of (serious) candidates in these contests is in practice often limited (Kenig et al., 2015; Aylott and Bolin, 2021). When party members are only allowed to rubberstamp the nominee of the party elite, their power is heavily restricted. Party leader elections are influenced by party elites who limit the number of candidates, especially during the stages preceding the actual election phase. As this process often takes place behind closed doors, not much is known yet about who is steering and how. This research aims at filling this gap.

More in particular, we investigate which persons try to limit the number of candidates in party leadership contests (RQ1a) and which persons succeed in limiting the number of candidates (RQ1b), which mechanisms are used to influence the process (RQ2a) and which mechanisms are effective in doing so (RQ2b). This adds to the research on party leadership elections in three ways. First the focus is on the informal side of party leadership elections while earlier research has mostly looked at formal rules and their direct effects (Kenig et al., 2015; Pedersen and Schumacher, 2015; Wauters and Kern, 2020). Next we concentrate on the role of elites in these elections and not on the behavior of party members (Seddone et al., 2020). Finally, the burgeoning research on “steering agents” and “influencing actors” (Aylott and Bolin, 2021) is put to the test as well as extended theoretically by unfolding the preparation phase of a leadership election step by step and by introducing additional influencing mechanisms in the process. An abductive research approach allowed us adapting the theoretical model postulated by Aylott and Bolin, and extending their framework to a model enabling to examine multiple types of influencing actors and the mechanisms used.

In order to assess the effectiveness of the influencing mechanisms at work, we analyze two leadership elections within the same party (Flemish Christian-democratic party, CD&V) that were held under very similar circumstances (i.e., the preceding parliamentary elections were lost and the incumbent party leader resigned in both cases), but with a large difference in the number of candidates. We contrast a typical case (the 2003 leadership election with only one candidate, which occurs in 10 out of the 12 leadership elections that have taken place in CD&V until now) with a deviant case (the 2019 election with unusual high number of seven candidates, and a second round to determine the eventual winner). By looking at similarities and differences between these divergent cases, we are able to determine which factors lead to a successful steering or influencing of the candidacy process (resulting in one single candidate).

We draw upon a large set of 22 interviews with elite informants. All official candidates for both elections were interviewed, together with 14 key party actors active during one or both leadership elections. This enables us to get a view on the influential people and the informal mechanisms at work in the party (rules-in-use), which cannot be detected if we only rely on the formal procedures (rules-in-form) (Lowndes et al., 2006). We untangle the idea of parties as unitary actors, demonstrating that the leadership elections were influenced by a cluster of different influencing actors. We distinguish in particular what we label “the last person standing”, whose candidacy is identified as the most effective mechanism to influence the nomination process, much more than encouragements, discouragements or the diffusion of an ideal profile for the future party leader.

2. Theory and hypotheses

2.1. Democratization: Rules-in-form vs. rules-in-use

Over the last decades, political parties in established democracies have increasingly introduced internal democracy, allowing the involvement of rank and file members in important policy and organizational decisions (Pilet and Cross, 2014; Ignazi, 2020). The goals of these reforms were aimed at repairing the linkage between state and society (Wolkenstein, 2016; Borz and Janda, 2020), increasing the party's attractiveness among citizens (Close et al., 2017; Wauters and Kern, 2020) and improving the performance and the image of the party (Scarrow, 1999; Pedersen and Schumacher, 2015). The most prominent change is arguably the democratization of party leadership selection (LeDuc, 2001; Ignazi, 2020).

Most of the existing research pragmatically studies leadership selection based on a party's statutory rules, the so-called “rules-in-form” (Lowndes et al., 2006; Musella, 2015; Radecki and Gherghina, 2015). Scholars often investigate the degree of inclusiveness of the selectorate, i.e., the body that decides who becomes the party leader. Kenig (2009a) developed an inclusiveness continuum on leadership selection procedures, based on a similar approach by Rahat and Hazan (2001) for candidate selection procedures. According to these rules-in-form, many parties including CD&V (Wauters, 2014), have moved from rather exclusive processes, such as a selection exclusively by party elites, toward more open and inclusive methods where each party member has a vote (Pilet and Cross, 2014; Poguntke et al., 2016).

Yet, scholars doubt whether this democratization as formulated in the statutory rules automatically translates into real democratization (Cross and Katz, 2013). Some even utilize the term “fake democratization thesis,” which means that greater inclusiveness masks the consolidation of power among party elites (Aylott and Bolin, 2021). Party elites seek new ways to exercise power, in order to balance the effects of democratizing the selectorate. There are built-in control mechanisms allowing to push the selection process in their preferred direction. Kenig (2009b), for instance, demonstrated that more inclusive procedures attract more (fringe) candidates, but lead to less competitive contests (see also Kenig et al., 2015). And the actual participation of members is often overestimated beforehand. Gauja (2013) calls this the paradox of actual participation: while the opportunities to participate in parties have increased, the willingness to participate actively has eroded. Even party members who evaluate intraparty democracy positively stay less active in the party (Koo, 2020). More in general, these reforms allow the elite to hold more control because the power of activists and middle-rank members is diminished by the participation of a large amorphous group of individual members which can be influenced more easily and which cannot easily renounce its approval to lead the party in between (Katz and Mair, 1995; Wauters, 2014; Radecki and Gherghina, 2015).

As a consequence, looking at the formal rules of leadership elections is not enough to understand the process and the outcome of leadership elections. And granting party members a say in internal decision-making might just be window-dressing. But one could wonder: if the power of the members should be nuanced, then who really has the power in leadership selection processes? (Cross and Katz, 2013). The party elite (who is supposed to hold much power) is a broad concept covering various party actors. Moreover, previous research is rather vague about how elites try to hold a grip on the decision-making processes after the internal democratization. Party rules may suggest that contests are wide-open, but that is unimportant if the party elite is (still) able to limit the level of competition. But which persons (from the party elite) engage in limiting the number of candidates in party leadership contests (RQ1a), which persons are successful in doing so (RQ1b), which mechanisms are used to limit the number of candidates (RQ2a), and which mechanisms are effective in doing so (RQ2b)? To understand this, we must take a look at the rules-in-use, especially during the nomination process preceding the actual election phase. We do so in the next sub-section, in which we also formulate hypotheses that follow the structure of our research questions, i.e. focusing on respectively the presence (a) and the effectiveness (b) of persons and mechanisms who are expected to influence the process.

2.2. Rules-in-use: The preparation phase

The “rules-in-use” refer to both the actual functioning of formal rules and to the presence of informal rules (Lowndes et al., 2006). We rely on Aylott and Bolin (2021)'s analytical framework distinguishing between different stages of a leadership pre-selection procedure in order to gain more insight in these “rules-in-use”: the gatekeeping phase, the preparation phase, and the phase of the actual decision. As we are especially interested in the informal process preceding a leadership contest, we decided not to address the formal rules establishing who can be a candidate (gatekeeping phase) nor the outcome of the election (the actual decision). Hence, this study focuses on the preparation phase of a leadership election which moves away from the official story toward the real story of the nomination process preceding the actual election phase. It consists of three dimensions: precursory delegation, process management and norms as constraints (Aylott and Bolin, 2021), which will be detailed in the next paragraphs.

The first dimension of the preparation phase, precursory delegation, refers to the delegation of the authority to limit the number of candidates to a “steering agent”. According to the model of Aylott and Bolin (2021), the “steering agent” could be defined as an intra-party actor who has the mission and capacity to affect the discretion with which the selectorate makes its formal decision. It is an individual or a group of individuals who try to steer the nomination process preceding the election phase. As stated by Aylott and Bolin (2021), the “steering agent” is an agent acting on behalf of a principle, for instance a party veteran who is working in the best interests of the party executive (Aylott and Bolin, 2017, 2021).

We, however, extend this argument and focus on all actors who try influence the nomination process instead of only focusing on those who receive a mandate inside the party and have thus in fact a monopoly on steering. We assume that different informal influencing actors will be active at the same time, as a party is not a unitary actor but is composed of different factions (Belloni and Beller, 1978; Aylott and Bolin, 2021) or has different leaders in public and central office who do not necessarily share the same interests (Mair and Katz, 2002). There are possibly multiple influencing actors instead of one, and no (formal or informal) mandate is needed to act as an influencing actor. This role can be played, for instance by the national executive committee, the incumbent party leader, the central party staff or the parliamentary party. Note that this is a fluid concept that can go from one of these suggested actors to another during the preparation phase (Jun and Jakobs, 2020). This helps us formulate an hypothesis about who is limiting the number of candidates (RQ1a):

H1a: There are different distinguishable actors trying to influence the leadership contest.

As our research questions also refer to the effectiveness of influencing, we also formulate an hypothesis about this effectiveness. In order to be successful, influencing attempts should not go in all kinds of directions with different kinds of actors, but need some form of coordination. Therefore, it could be expected that in contests with only one candidate, there is a clearly distinguishable person who manages both to resist influencing attempts from influencing actors in contradictory directions and to convince fellow elite members that his/her options are best for the party. Therefore, we expect that while there might be attempts by several influencing actors, for a successful steering, it is best to have one specific person, namely the steering agent, who stands out.

H1b: There is one clearly distinguishable steering agent steering the process in contests with a limited number of candidates.

We now move over to the second group of research questions about which mechanisms lead to a limited number of candidates (RQ2a) and which mechanisms are most effective (RQ2b). We distinguish two mechanisms steering actors and influencing actors can use to steer and influence the process of leadership elections. The first mechanism is based on the second dimension of the preparation phase, namely process management and refers to how aspiring leaders are persuaded to pursue (or to drop) their plans to become the new party leader (Aylott and Bolin, 2021). This can be done either in a positive or negative way. The former refers to encouraging aspirants to formally become a candidate—what likely increases the number of candidates, while the latter denotes discouraging or even obstructing the candidacy of some aspirants, most notably by threatening with sanctions, for instance about the future career of an unwanted aspirant—what will put off potential candidates to run. Since this whole preparation phase is not visible to the public and based on informal processes, it can be expected that effective steering or influencing will take place during this phase. Note that we leave it open who undertakes these encouragements and discouragements as the presence of steering agents or influencing actors is a research question on itself (see above) and that hypotheses cover respectively the presence and the success of these mechanisms.

H2a: Informal encouragements are used as steering and influencing mechanisms in leadership contests.

H2b: Informal encouragements play an important role in increasing the number of candidates.

H3a: Informal threats with sanctions are used as steering and influencing mechanisms in leadership contests.

H3b: Informal threats with sanctions play an important role in limiting the number of candidates.

Norms as constraints are the second group of mechanisms that can be used to influence the leadership election and are also the last dimension of the preparation phase (Aylott and Bolin, 2021). They refer to general expectations about what a new party leader should be like or should do in the next term. In Aylott and Bolin (2021)'s framework, these norms are regarded without any reference to a particular person. For instance, when a party has lost elections, there might be a desire to have a leader who is able to make the party more attractive in electoral terms (Pedersen and Schumacher, 2015), or when a party has been kicked out of government, a more compromise-ready leader might be appropriate. There can be a general feeling in the party about the ideal profile of the next party leader, or this can be decided and communicated by the steering agent or (one of) the influencing actor(s). Evidently, when such a profile of the ideal leader is spread, potential candidacies will be evaluated in this light and potentially also withdrawn by potential candidates themselves. Therefore, we expect that when such a profile is spread, the number of candidates will be lower.

H4a: Spreading the profile of an ideal leader is used as steering and influencing mechanism in leadership contests.

H4b: Spreading the profile of an ideal leader plays an important role in limiting the number of candidates.

We suggest to further the mechanism of norms as constraints (Aylott and Bolin, 2021) by investigating the possibility that the profile of the candidates who already announced their candidacy (or threaten to do so) deters other potential contenders from running for party leadership. The very act of becoming a candidate in a leadership election may steer or influence the process by putting off potential aspirants. For example, two candidates from the same region could get in each other's way as they appeal to the same members to get elected. The aspirant believing that her profile is less promising than her counterpart may withdraw her candidacy. Likewise, the candidacy of a popular politician can stop someone from entering the race because he or she thinks that it is impossible to win against that candidate. We thus expect popular party figures with a large electoral base, from regions where the party is electorally strong, and/or with close ties to civil society organizations to be able to scare off potential aspirants and hereby reduce the number of candidates.

H5a: The candidacy (or the threat of) of promising party figures is used as steering or influencing mechanism in leadership contests.

H5b: The candidacy (or the threat of) of promising party figures plays an important role in limiting the number of candidates.

3. Method and data

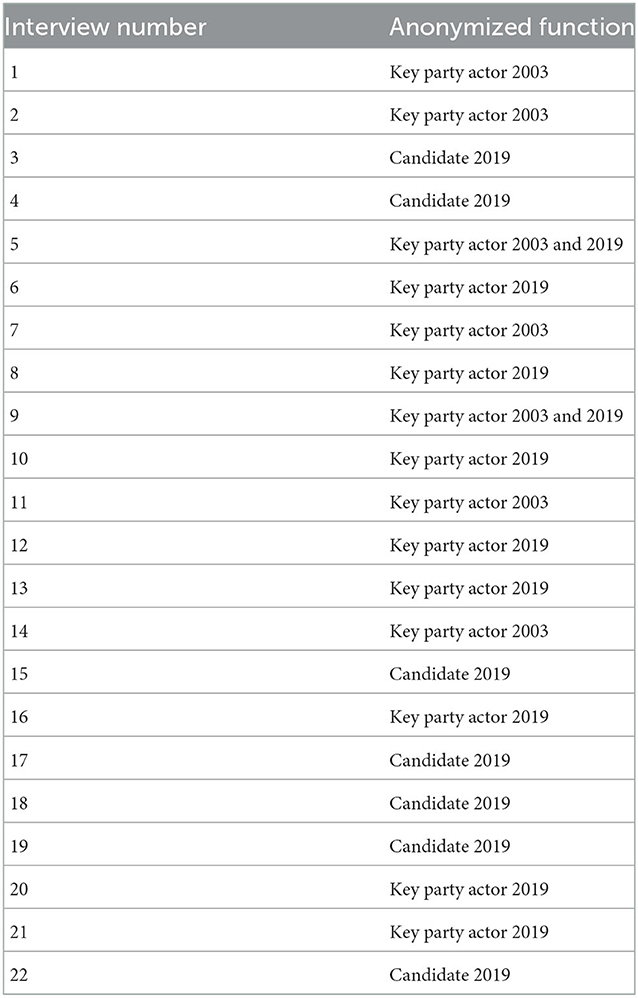

The data this study centrally draws on stem from a total of 22 in-depth elite interviews (see Appendix 1 for details on interviewees). Elite interviews allow us to look at the political reality through the lenses of its central protagonists who can help us reconstruct the contexts of the selection procedures (Lilleker, 2003; Solarino and Aguinis, 2021). The analysis of these interviews cannot provide hard quantitative evidence for the effectiveness of the mechanisms, but they can nevertheless point to more and less effective mechanisms taking into account the context and the nuances associated with each case. We decided to interview party leaders, candidates and key party actors such as party secretaries and spokespersons. This resulted in a total amount of 22 respondents. Seven of them were active during the leadership election of 2003 and 17 during the 2019 leadership election. The data are mechanically skewed toward the latter case because there was only one candidate for the party leadership in 2003 while there were no less than seven candidates in 2019.

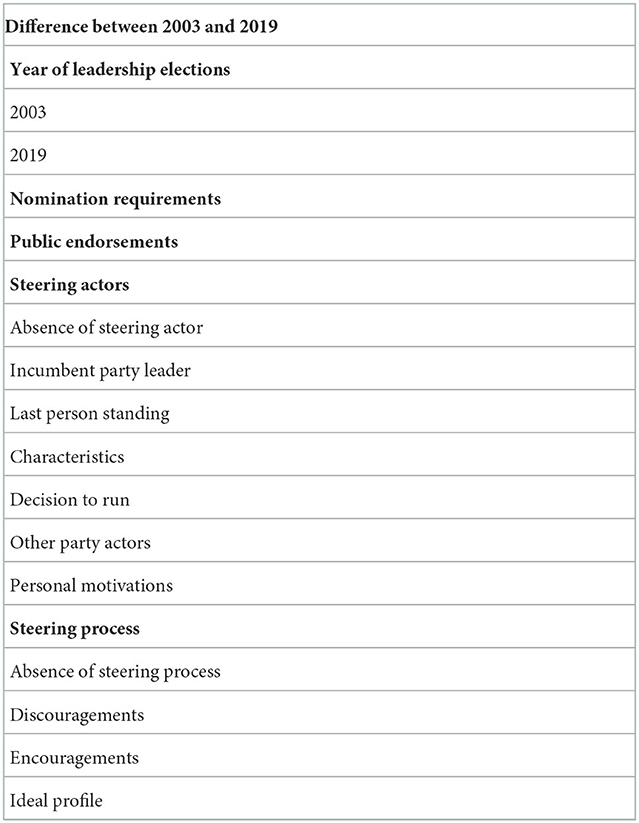

The interviews were conducted by the authors between June and October 2021 and lasted 35 minutes on average. The interviewees were presented an informed consent form, and all interviews were recorded and manually converted into a transcript by a job student. In addition to the interviews, we consulted media reports and internal party documents (party statutes and leadership election rules). The analysis of the interview transcripts has been undertaken in two stages following an abductive research approach. Several researchers first carefully examined the transcripts to assess to what extent the theoretical expectations based on extant literature could hold. Based on this exploratory analysis, we went back to the theory and developed and adapted the model as it is presented in the current study. Afterwards, we investigated our empirical material once again, but this time thanks to a cross-sectional code and retrieve method in NVivo. We applied a systematic categorization of segments of the transcripts into thematic nodes corresponding to our hypotheses (Ritchie and Lewis, 2003), crossing them in the last phase with the election year at hand (2003 or 2019) to investigate patterns according to the number of candidacies. The codebook used in this study to categorize segments of text of our interviews is attached in Appendix 2.

Case selection has two objectives: it must produce (1) a representative sample and (2) a sample with a useful variation on the dimensions of theoretical interest (Seawright and Gerring, 2008). By analyzing leadership elections of CD&V, the first objective is met. As almost all Belgian parties select its party leader in a membership vote (Pilet and Cross, 2014), CD&V is no exception in this respect. Also coronations are usual in Belgium: about half of all leadership contests have only one single candidate (Pilet and Cross, 2014), which makes the 2003 CD&V leadership election a typical case for successful steering of the nomination process. The 2003 leadership elections are not only typical compared to leadership contests in other parties, but also compared to CD&V leadership contests as they stand out with 10 out of 12 contests with only one candidate.

Our two cases also meet the second objective by showing a useful variation on the dimension of interest. As the 2003 elections had a very typical process resulting in only one candidate, the 2019 leadership contest had an unusually high number of seven candidates, which makes it a deviant case. This very different level of competition allows us to clarify which unique elements and actors could be held accountable for successfully limiting the number of candidates in leadership elections. More in particular, we look at (f)actors present in 2003, but not in 2019.

The number of candidates differs between both leadership elections, but the context was kept as constant as possible in order to control for contextual confounders. The contextual differences that we could not control (e.g., the lower electoral score of the party in 2019 than in 2003) were taken into account in the analysis, but other important variables for party leader elections were highly similar. We looked in a single party at elections in which the incumbent party leader did not participate but resigned after an electoral defeat. In 2003, party leader Stefaan De Clerck had to resign following poor electoral results. De Clerck became party leader in 1999 (and was reconfirmed in 2002) and had the difficult task to reform his party after the Christian-democrats were sent to the opposition for the first time in more than 40 years. At the national elections of 2003 and after 4 years of opposition, the party's vote share slightly declined from 22.4% of the Flemish votes to 21% and the party was unable to re-enter government. The reorganization of the party failed to bear fruit and De Clerck resigned. With the prospect of the 2004 regional elections, many Christian-democrats were convinced that they needed a new party leader. Yves Leterme was the only candidate to replace him. He entered parliament in 1997, and moved quickly from backbencher to a prominent party figure. He was elected as party leader with 93.1% of the votes.

Although CD&V was part of both the national and Flemish government (but no longer delivering the government leader) between 2014 and 2019, the electoral context of the 2019 leadership elections was similar to 2003. The Christian-democrats were in decline and achieved actually the worst electoral result in the history of Flemish Christian-democracy. They only got 14.2% of the Flemish votes. Under these conditions the incumbent party leader Wouter Beke did not aspire a fourth term as party leader. Despite a comparable electoral context, the party leader election itself turned out to be totally different, with seven candidates instead of one. Hilde Crevits, regional minister and the leading lady in the campaign of the preceding parliamentary elections, who seemed hand-picked to be the next party leader, did not apply, leaving a power vacuum paving the way for the most open elections ever in the party. None of the candidates had ministerial experience and three of them even had no parliamentary experience. In the first round, no candidate got half of the votes which means that a second round between the two best scoring candidates (Joachim Coens and Sammy Mahdi) was needed. Coens, who played no national role in the party (he was a mayor of a small municipality and CEO of the port of Zeebrugge), won with 53% of the votes.

4. Analysis

We investigate first which party elites strived to influence the process, and second how they influenced or steered the leadership nomination processes resulting in respectively one (2003) and seven (2019) candidates. Our goal is to understand how (un)successful the mechanisms used by a steering agent or influencing actors were in limiting the number of candidates.

4.1 Who is steering or influencing the process?

According to the party statutes, the national party secretary is in charge for the practical organization and the smooth proceedings of the leadership elections, but s/he is not formally authorized to steer the nomination process, nor are any other party elites. From the interviews, it appears that a multitude of people inside the party try to influence the kind and the number of candidates who eventually come forward.

“CD&V is a party where people talk a lot. So you have a lot of things that arise very organically because a lot of people talk to each other. We are not an authoritarian party where there is a brain that decides something and implements it in the organization. Not at all. So that's kind of a game that happens at some point.” (Interview 7)

In line with our first hypothesis, we observe several influencing actors or high-ranked party members trying to weigh on the process. Based on the interviews, we distinguish three kinds of party elites playing a role in determining the number of candidates: the “last person standing,” the incumbent party leader, and other (current and former) prominent party actors.

4.1.1. “Last person standing”

We start with what we label the “last person standing”, or the single person who performed electorally well in parliamentary elections with a general declining trend for the party. Both leadership elections at stake took place after an electoral defeat in parliamentary elections (see above). Many in the party were disappointed about the electoral result and tended to stick to well-performing politicians who against the general tide made electoral progress in the own district and/or limited the electoral damage in that district, in combination with a high number of personal preference votes (Wauters et al., 2020). They are considered as a means of last hope and resort for the party in crisis. In 2003, Yves Leterme was in that position. As number 2 on the list, he obtained an exceptionally high number of preference votes, and in his electoral district, the party lost a minimal share of votes compared to losses elsewhere. The last person standing in 2019 was Hilde Crevits who managed to limit the electoral loss in her electoral district, while obtaining the highest number of preference votes of all candidates of the party.

Both could be considered as “last person standing” in a party in decline and hence, they were seen as the evident person that should take the lead of the party. Thereby party actors hoped that they were able to extend their personal resistance to the general downward trend to the party as a whole. Many inside the party estimated it to be self-evident that they would become the new party leader, and even insisted informally that they should submit their candidacy, expected to be uncontested. We should stress that this is not a coordinated process, but rather a self-steering one in which the evident new leader could spontaneously come forward without much resistance of other partisans.

“After the 2003 parliamentary elections there was a very large consensus around the feeling that the party leadership function would be best taken up by Yves Leterme. As it is in 2019, there would also have been a great consensus if that happened by Hilde Crevits.” (Interview 6)

Our two cases display, however, diverging dynamics around the influence of the “last person standing” on the number of candidates. In 2003, the electorally successful Yves Leterme was solicited by many prominent party members to become a candidate for party leadership, what he eventually did, resulting in a single-candidate leadership election. The fact that he took the plunge resulted in drastically limiting the number of contenders. Hilde Crevits was in 2019 in a similar position as Leterme. As we detail later, her candidacy would probably also have refrained other candidacies, resulting in a similar single-candidate contest. But she declined, giving priority to her (safer) position as deputy prime minister in the regional Flemish government.

“I suspect that she is very happy to do what she does as a minister in the Flemish government. And that she wanted to make that a priority. Otherwise her candidacy would have happened.” (Interview 21)

“I think Hilde likes to be deputy Prime Minister in the Flemish government, so why should she want to be party leader? She's fine where she is. So I don't know if she wanted to take that responsibility. When you have a strong role in the Flemish government, then it is difficult to stand on the shaky ship of CD&V. While you are currently sitting on the rather solid Flemish boat.” (Interview 22)

From the interviews, the electoral strength of the party appears as a central factor as to why in 2019 the “last woman standing” (Crevits) did not enter the leadership contest, while in 2003 the “last man standing” (Leterme) did. While in 2003 CD&V was still one of the major parties in electoral terms with a good prospect of a future leading role in government, it has become a rather small party in 2019 which still makes a chance for government participation, but with minimal odds for the leading role. Also future electoral prospects are not very glorious. Therefore, becoming party leader could be considered a poisoned chalice. This might explain why Hilde Crevits preferred a “safe” position of regional government minister over party leadership.

It is, however, not because the “last woman standing” did not compete that she did not try to influence the candidate nomination process. Hilde Crevits did efforts to gather support for a local politician, but after several informal consultations, that person eventually decided not to run (Interview 7). She also tried to discourage other potential candidates and/or privately expressed her resentment once they were officially a candidate (Interview 17). Her main concern seemed to be a smooth transfer of power to a new party leader with broad support in the party. A contest with many candidates would cancel this scenario. Later on in the process, in the actual election phase, she also expressed in inner party circles her support for Joachim Coens, the candidate who finally won the leadership contest (Interviews 15, 17, 22).

In sum, the “last person standing” can play with different cards to limit the number of candidacies: either running him/herself, what can put off potential contenders, or steer the process from the outside. From our analysis, the first option seems to lead to more success, considering that the 2019 nomination process gathered no less than seven candidates.

4.1.2. Incumbent party leader

A second person that could be influential in limiting the number of candidates is the incumbent party leader. In this respect, the contexts of 2003 and 2019 highly differ. In 2003, the change in party leadership was rather unexpected and a direct consequence of the electoral defeat. Initially, it was the intention of Stefaan De Clerck to continue as party leader, but after the electoral loss, pressure both from within and outside the party was so strong that he had to resign. His resignation was, however, facilitated by the knowledge that Yves Leterme would become his successor. They had a very good personal relationship and similar ideas.

“I think he [De Clerck] indicated quite quickly that he wanted to step aside as party leader. And that he certainly didn't resist as soon as he saw that everyone was heading the way of Leterme. There were also coincidences. They were both from the same region. (…) They commuted to Brussels together. They sat together in the car for hours and so he could experience how Leterme was approached by others. (…) They were friends within a political context, but more than within a political context. So there was a general confidence and I think that was an element that made Stefaan [De Clerck] cooperate more smoothly, in the end he cooperated smoothly with a fairly soft transition.” (Interview 9)

Many interviewees concede that incumbent party leader De Clerck has had some impact on the nomination process. Although Leterme came forward as a natural leader as “last man standing,” the explicit support of his predecessor has definitely facilitated a single-candidate election. Hence, using the words of Jun and Jakobs (2020), Leterme can be seen as the “crown prince” of De Clerck.

In 2019 on the contrary, it was long beforehand clear that Wouter Beke was serving his last term as party leader. His position and the appreciation for his person in the party were seriously weakened after the electoral defeat and due to the contested decision to select himself twice as minister. Consequently, his legitimacy to influence the nomination process was much weaker than the incumbent party leader in 2003.

“You also have to keep in mind that the authority of a party leader is less if you lose elections than if you win elections.” (Interview 9)

“[Wouter Beke]'s succession was not arranged, but he tried everything, including names such as [gives two names of possible aspirants]. No one really wanted to do it. Hence you have seven B candidates, or—with all due respect—maybe C candidates.” (Interview 17)

Taken together, two factors are likely to impact whether or not the incumbent party leader is successful as influencing actor: if he/she is appreciated in the party and if the leadership contest comes rather unexpected. In the latter case, the incumbent party leader is given some impact on who will succeed him/her to smoothen his/her unanticipated departure.

4.1.3. Other party actors

Finally, there are many other party actors striving to influence the number of aspirant party leaders. In 2019, the decision from the party elite was clearly not to officially steer the process, unlike in 2003 when they sat together and practically designated the single candidate.

About 2019: “There was a bit of a search too of: who would be best placed to take over now? […] Is it good to have a guided approach or an open approach? There have also been some conversations around that. For example with Hilde Crevits to take over the leadership.” (Interview 6)

About 2003: “We came together with a limited number of people; with precisely those list pullers, parliamentary party leaders in the Chamber, the Senate and the Flemish Parliament. We were actually going to determine who will be the new chairman there and who the new parliamentary party leaders would be. We then met that afternoon in a tavern that I know well, and there we proposed, and that was not difficult, that Yves Leterme would be our candidate to become the leader.” (Interview 14)

In 2019, the lack of a single steering agent resulted in a chaotic cluster of many informal interactions between prominent party actors and (aspirant) candidates. A lot of discussions were taking place behind the scenes, initiated by both aspirants and current and former party elites. Aspirants asked for advice and tried to weigh their chances; prominent party figures encouraged or discouraged aspirants to enter the contest (Interviews 3, 5, 8, 11, 17, 22).

“I actually did two tests: I did a test with the top of the party: the ministers and the party chairman... And I also did one with some of the MPs and the youth section to investigate whether there was a willingness or the will to create a new team that goes for such a strategy.” (Interview 11)

Our analysis allows us identify different influencing actors and their relative success in limiting the number of candidacies for party leadership (RQ1a and RQ1b). Especially the “last person standing” and the incumbent party leader can be successful in steering the nomination process, but only under certain circumstances. The “last person standing” is likely to succeed if s/he runs for leadership her/himself, rather than trying to stimulate other candidacies. The resigning party leader must still be appreciated and powerful in the party for his influencing endeavor to bear fruit. On top of that, we stress that not steering the process can also be a well-thought-out choice from the party elite. Hence, we can confirm H1a: there are several people from the party elite influencing the nomination process, but we found only partial confirmation for H1b: the last person standing appears to be the single most important influencing actor, but (s)he only succeeds under the right circumstances.

4.2. Which mechanisms are used to steer the process?

After having focused on the actors influencing the process, we now turn to the mechanisms they use to limit the number of candidates (RQ2a) and whether these mechanisms are successful in doing so (RQ2b) relying again on our comparison of two different competitive leadership contests: 2003 (no competition) and 2019 (intense competition).

4.2.1. Encouragements and threats

Almost all aspirants and would-be aspirants experienced informal influences of party actors, trying to stimulate their candidacy, or on the contrary to refrain it. Most attempts were subtly expressed and mostly in private conversations (Interviews 7, 8, 11, 12).

“They [the party top] tried to remain neutral about this, but some people succeeded better than others. But I didn't feel like they were really putting a lot of pressure on it. But I could sense from the way [actor from the party top] approached me that they would rather prefer I hadn't done it.” (Interview 15)

“Those are usually one-on-one conversations that you have and in the best case one-on-two. It's not like we're having a meeting about this.” (Interview 7)

“Eventually then, [two actors from the party top] cautiously approached me in early September and asked me whether I was interested in becoming a candidate for party leadership. I did not answer yes to their question at the time, but I actually said: I'm going to think about it for a while.” (Interview 8)

The interviews clearly demonstrate that most aspirants were encouraged (Interviews 3, 9, 17, 18, 19 and 22). These encouragements either stimulated or confirmed their personal ambition to run for leadership. Some others were discouraged to apply, and at least in one case, it was substantive enough to prevent the candidacy (Interview 5). Yet, not all influencing efforts yielded positive results: many encouragements did not lead to a candidacy, and likewise some threats did not scare off the candidate (Interviews 8, 11, 12, 15 and 22). Most (potential) candidates had a clear idea about whether or not they wanted to enter the competition and why.

“I made that decision myself, but then I got support afterwards.” (Interview 18)

“The party top made an attempt to change my mind, only to not do it anyway. But well, I would have experienced it as a downfall to have to say at the last minute: “yes, after the consultation with the party top I withdrew, I will no longer participate”, how weak are you then? I thought no, I'll stick with it and I'll be a candidate.” (Interview 15)

“The only one who sent me a negative text was [actor from the party top]. (…) In this text message she said not literally that I should not have been a candidate, but clearly related to my candidacy, she said: “you hurt me personally with this”. (Interview 17)

What really made the difference between 2003 and 2019 was the general lack of substantial attempts in the 2019 leadership elections. Interviewees concede that this situation was rather exceptional. The candidates and the party organization were in 2019 apprehensive about too much interference from the party elite, considering that the absence of one obvious candidate paved the way to a real open contest that one should not disturb. The scenario of 2003 is indeed actually much more common in this party, namely forward one candidate, and ward off potential contenders, out of fear of bad publicity.

“It took a very long time for the sides to be chosen [by the party elites in 2019]. And there was also a fear that the wrong person would win. And they were also wary of pushing too much for one person that it would eventually have the opposite effect. It was not like it used to be twenty years ago, where the party chooses the candidate and he would become party leader and if necessary they push it down your throat. It was less easy, it was done much more subtle.” (Interview 17)

“I said we have just lost now, that it is the death knell for the party to have an open election. We were not used to that. That would really expose the divisions openly.” (Interview 14)

In sum, we conclude that both informal encouragements and discouragements or threats happen, but these are not equally and always successful in impacting the number of candidacies. What rather seems to impact the effectiveness of positive or negative attempts to influence the number of candidacies is the willingness from influencing actors to substantively influence the process. This results in a partial confirmation of hypotheses 2a and 2b, and 3a and 3b.

4.2.2. Profile of the ideal leader

Next to encouraging or dissuading candidacies, another mechanism to influence the process is to diffuse norms about what the ideal new leader should look like, or directly facing the candidacy of a promising potential party leader to scare off other aspirants. We first discuss the diffusion of an ideal profile before turning to the (threat of a) candidacy of a candidate matching some ideal characteristics of the projected leader.

A major norm about the “ideal candidate” in 2019 was that it had to be someone from the new generation inside the party, as formulated in an internal analysis after the electoral defeat in the 2019 general elections (Interviews 3, 4 and 7). This criterion downplayed—at least—the ambition of a long serving MP substantively enough to eventually prevent his candidacy (Interviews 5 and 20). They were also looking for someone distant enough from the government cabinets to be able to defend the party line more strictly (Interview 21). Yet, most of the candidates were convinced they had an interesting profile (e.g. being a new figure, representing “the party on the ground,” representing an ideological flank of CD&V) and estimated that they had good chances at winning the general elections in the future (Interviews 3, 15, 17, 18 and 19).

“Looking again in the same circle is not a good signal to the outside world, because it seems that it is all the same people who carry this party and that does not match the reality.” (Interview 7)

In 2003, CD&V was rather looking for someone who was able to sell the party message more convincingly to a large audience. Although the former party leader Stefaan De Clerck had launched a large party reform, he was unable to attract many voters, seemingly due to his poor communication skills. Moreover, given that the regional elections would follow already one year later (in 2004), there was no time for someone new to gain experience. Hence, the general consensus went toward an experienced politician with good communication skills. Yves Leterme almost perfectly matched that profile.

In sum, both in 2003 and 2019, there was a clear idea about the general profile of the new party leader: a new face (2019) vs. an experienced communicator (2003). As such, hypothesis 4a is supported. It seems that not so much the presence of a profile, but rather the kind of profile plays a role in limiting the number of candidates. While the pool of new faces is much larger than that of experienced communicators, more aspirants will recognize themselves in the profile of the former than of the latter. This only leads to a partial confirmation of hypothesis 4b. Not so much the presence of a preferred profile, but the kind of ideal profile can weigh on the number of candidacies.

Further than spreading norms about an ideal profile, some real candidacies might also function as hindrance for other candidacies. When potential aspirants positively assess the candidacy of another party actor, or the threat of a candidacy, they might refrain from entering the race themselves. This candidate could refer to the profile of ideal candidate that was spread in the party. This candidate might coincide with the above described concept of the “last person standing,” as a potential candidacy can only have an impact when the person enjoys a large electoral base, but is not restricted to this person.

In 2019, the “last person standing,” Hilde Crevits, did not become a candidate, nor did another key party actor with more modest electoral success but a serious legitimacy and depicted by some interviewees as a promising potential party leader. As outlined above, several candidates (but not all, see interview quote below) indicated that they would not run for party leader if Crevits had stood as a candidate. In doing so, the candidates were convinced that there was a large consensus around her so that the opposing candidate did not have a chance of becoming leader (Interview 5). Although nor Crevits nor the other prominent party actor did run for party leader, Crevits kept the power of a possible candidacy to steer the process. This became very clear when she used this possibility as a mechanism to make others withdraw from the leadership election. The other actor used his power to stimulate candidacies, and was successful in doing it.

“Had Hilde Crevits been a candidate, I would still have been a candidate. Would I have made it? Probably not, because Hilde is a minister and has a name I don't have. And that makes you start the race with a certain advantage.” (Interview 22)

“It was almost as, if I was candidate, Hilde was going to be candidate as well. If I went for candidacy, Hilde was going to say yes, which meant that I had no chance of winning the elections.” (Interview 5)

In contrast, in 2003, the “last person standing” Yves Leterme did enter the electoral race, which resulted in a coronation. This can be seen as a successful action to steer the process as others indicated that they decided not to officially run because of Leterme's candidacy. Reacting on why he did not enter the leadership election race in 2003, an interviewee reported:

“For the same obvious reason that anyone who might have thought: [being a candidate for leadership] that's something for me, realized very well that there was a much better person placed to do it. Nobody was in the mood to start debating a consensus figure.” (Interview 10)

“You could sense that Leterme who was good with everyone who relied on his thoroughness, but he was also excellent in networking with everyone, he always kept good contacts and so on, he was a figure of dialogue, yes of keeping lines open... and pick up on people's concerns and stuff. You also felt that there was no resistance to it, also in terms of ages and such: from young people to seniors and such (…) Sitting there, nobody came near him to say: I'm going to be a candidate against that.” (Interview 2)

In essence, the possible candidacy of a promising potential party leader such as the “last person standing” can have a serious impact on the number of candidates. One the one hand, if a consensus figure enters the scene, it can prevent other aspirants to announce their candidacy. When such a consensus figure decides not to compete for party leadership, this leads to a power vacuum and eventually boosts the number of candidates. This leads us to mostly confirm hypotheses 5a and 5b.

5. Discussion and conclusion

Parties in Western democracies, including Belgium, increasingly allow their members to select the party leader. Members' impact is, however, often constrained by the limited number of (serious) candidates in these leadership contests (Kenig et al., 2015). Party leadership selection is in practice often a coronation of a single candidate rather than a real contest. Evidently, the nomination process preceding the actual election phase is crucial in understanding by whom and how the number of candidates is successfully or unsuccessfully limited. In order to gain more insight, we analyzed the preparation processes of two leadership contests in one single party, i.e., the Flemish Christian-democratic party (CD&V) in Belgium. We focused on the leadership elections of 2003, with one single candidate (Yves Leterme) who was rubberstamped by the party members, and on those of 2019 with an exceptionally high number of seven candidates (ultimately won in a second round by Joachim Coens) to examine the effectiveness of the different mechanisms influencing actors can use.

Our analysis, based on 22 in-depth elite interviews with (former) prominent party figures including all leadership candidates and several potential candidates, demonstrates that the leadership elections of both 2003 and 2019 were influenced by a cluster of different influencing actors. Both what we labeled the “last person standing” (i.e., the single person who performed electorally well in a general declining context) and the incumbent party leader were, together with other party actors, trying to influence the nomination process successfully in 2003 and rather unsuccessfully in 2019. The lack of success in the latter case is, according to our findings, especially related to the absence of a consensus figure like the “last person standing.” This final mechanism seems a very effective tool to influence the number of candidates in a leadership election. The absence of a consensus candidacy can lead steering agents to purposely not coordinate and let the contest open to who wants to run, or on the contrary bundle around a single candidate.

This research has important implications for the literature on intra-party democratization processes. Recent literature has focused on the difference between rules-in-form and rules-in-use of democratization processes. Our findings display the relevance to account for the many informal influence attempts occurring within parties way before rank-and-file members have a say. Relatedly, we also confirm the thesis that parties are no unitary actors, as many individuals try to influence the process, but that when no consensus can be reached informally, the formal power of party members resurfaces when the final choice is left to them in a competitive contest. Although we focused on a specific case, the Flemish Christian-Democratic party, we expect our results to be representative for other political parties inside and outside the Belgian context. CD&V represents a traditional political party in electoral decline (both in 2003 and 2019). We suspect that our findings can be transposed to (particularly mainstream) parties experiencing electoral decline. However, future research will have to reveal whether multiple steering actors and steering mechanisms are present in other parties' leadership contests in the Belgian and international contexts.

In this article, we also propose an adaptation of Aylott and Bolin (2021)'s theoretical framework to investigate leadership selection procedures. While we put their theoretical expectations to the test on a new case, we also further develop their reasoning on norms as constraints by emphasizing not only the importance of the diffusion of an ideal profile of a future party leader, but also the actual candidacy, or threat of, of a promising potential leader.

We especially encourage researchers of party leadership processes to dig deeper in our inductively derived concept of the “last person standing” to uncover whether and how it operates in other parties and party systems. We have detected this phenomenon in a very specific context, namely in a party that suffered an electoral defeat in the preceding general elections and with an incumbent party leader no longer aspiring another term. It remains to be seen which role a “last person standing” could play when only one of these two conditions is met. For instance, could an incumbent party leader also function as “last person standing” if the party has lost the preceding elections? Or could bad opinion poll results force a party to rely on a “last person standing” even if the preceding general elections were successful? And is there in electorally successful parties logically no “last person standing,” or could it be that some variant occurs there, such as “the most successful candidate,” who is almost automatically solicited as next party leader? Future research in other parties and other contexts should try to formulate an answer to those questions.

The same goes for explaining the success of steering or influencing mechanisms. Apart from the appearance of the “last person standing,” we have detected several other mechanisms to influence the candidacy process (including encouragements, discouragements, and spreading an ideal profile). We came to the conclusion that they are not always effective in limiting the number of candidates. Future research could dig deeper in which factors contribute to a successful steering. Here again, parties in other contexts are interesting to study. For instance, it might be that discouragement is more effective in electorally successful parties because they have the possibility to assign more (attractive) positions in the party, the government and the administration than less successful parties. Also the kind of (potential) candidates could be relevant, in the sense that perhaps young and less experienced politicians benefit more from encouragements than their older and more experienced counterparts.

There is clearly still much more to uncover from the nomination process preceding party leadership elections, but we hope that by this analysis on two divergent cases in one party we have given some inspiration for future research.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they consist of sensitive in-depth interviews among party elites. The interviewees signed an informed consent form ensuring them the data would only be accessible by the authors. Further queries should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JL, LL, NB, AV, and BW contributed to the conception and design of the study, reviewed the literature, and wrote sections of the manuscript. JL, LL, NB, and BW each conducted elite interviews. JL and AV coded and analyzed the 22 elite interviews. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We would like to warmly thank all respondents from CD&V for their time and valuable insights. We are also indebted to Belén Garcia-Guisasola and Ellen VandenBulcke for their work on the interview transcription. We finally express our gratitude to the editors of the Research Topic, Nicholas Aylott and Niklas Bolin, for having launched this collective endeavor and all the coordination work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aylott, N., and Bolin, N. (2017). Managed intra-party democracy: precursory delegation and party leader selection. Party Politics 23, 55–65. doi: 10.1177/1354068816655569

Aylott, N., and Bolin, N. (2021). Managing Leader Selection in European Political Parties. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-55000-4

Belloni, F. P., and Beller, D. C. (1978). Faction Politics: Political Parties and Factionalism in Comparative Perspective. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio.

Borz, G., and Janda, K. (2020). Contemporary trends in party organization: revisiting intra-party democracy. Party Politics 26, 3–8. doi: 10.1177/1354068818754605

Close, C., Kelbel, C., and van Haute, E. (2017). What citizens want in terms of intra-party democracy: popular attitudes towards alternative candidate selection procedures. Political Stud. 65, 646–664. doi: 10.1177/0032321716679424

Cross, W. P., and Katz, R. S. (2013). The Challenges of Intra-Party Democracy. Oxford: OUP. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199661879.001.0001

De Winter, L., and Dumont, P. (2003). Belgium: Delegation and Accountability Under Partitocratic Rule. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/019829784X.003.0006

Deschouwer, K. (2009). The Politics of Belgium: Governing a Divided Society. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gauja, A. (2013). “Policy development and intra-party democracy,” in The Challenges of Intra-Party Democracy, eds B. Cross and R. S. Katz (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 116–135. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199661879.003.0008

Ignazi, P. (2020). The four knights of intra-party democracy: a rescue for party delegitimation. Party Politics 26, 9–20. doi: 10.1177/1354068818754599

Jun, U., and Jakobs, S. (2020). The Selection of Party Leaders in Germany. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 73–94. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-55000-4_4

Katz, R. S., and Mair, P. (1995). Changing models of party organization and party democracy: the emergence of the cartel party. Party Politics 1, 5–28. doi: 10.1177/1354068895001001001

Kenig, O. (2009a). Classifying party leaders' selection methods in parliamentary democracies. J. Elect. Public Opin. Part. 19, 433–447. doi: 10.1080/17457280903275261

Kenig, O. (2009b). Democratization of party leadership selection: do wider selectorates produce more competitive contests? Electoral Stud. 28, 240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2008.11.001

Kenig, O., Rahat, G., and Tuttnauer, O. (2015). “Competitiveness of party leadership selection processes,” in The Politics of Party Leadership: A Cross-National Perspective, eds W. Cross and J.-B. Pilet (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 50–72. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198748984.003.0004

Koo, S. (2020). Can intraparty democracy save party activism? Evidence from Korea. Party Politics 26, 32–42. doi: 10.1177/1354068818754601

LeDuc, L. (2001). Democratizing party leadership selection. Party Politics 7, 323–341. doi: 10.1177/1354068801007003004

Lilleker, D. G. (2003). Interviewing the political elite: navigating a potential minefield. Politics 23, 207–214. doi: 10.1111/1467-9256.00198

Lowndes, V., Pratchett, L., and Stoker, G. (2006). Local political participation: the impact of rules-in-use. Public Admin. 84, 539–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2006.00601.x

Mair, P., and Katz, R. (2002). “The ascendancy of the party in public office: Party organizational change in twentieth-century democracies,” in Political Parties: Old Concepts and New Challenges, Vol. 24, eds R. Gunter, J. R. Montero, and J. J. Linz (Oxford: Oxford Academic Press), 113–136.

Musella, F. (2015). Personal leaders and party change: Italy in comparative perspective. Italian Political Sci. Rev. 45, 227–247. doi: 10.1017/ipo.2015.19

Pedersen, H. H., and Schumacher, G. (2015). “Do leadership changes improve electoral performance?,” in The Politics of Party Leadership: A Cross-National Perspective, eds W. Cross, and J. -B. Pillet (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 149–164. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198748984.003.0009

Pilet, J.-B., and Cross, W., (eds.). (2014). The Selection of Political Party Leaders in Contemporary Parliamentary Democracies: A Comparative Study. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315856025

Poguntke, T., Scarrow, S. E., Webb, P. D., Allern, E. H., Aylott, N., Van Biezen, I., et al. (2016). Party rules, party resources and the politics of parliamentary democracies: How parties organize in the 21st century. Party Politics 22, 661–678. doi: 10.1177/1354068816662493

Poguntke, T., and Webb, P. (2005). “The presidentialization of politics in democratic societies: a framework for analysis,” in The Presidentialization of Politics: A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies, eds T. Poguntke and P. Webb (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1. doi: 10.1093/0199252017.001.0001

Radecki, M., and Gherghina, S. (2015). Objective and subjective party leadership selection: regulations, activists, and voters in Poland. Eur. Polit. Soc. 16, 598–612. doi: 10.1080/23745118.2015.1072342

Rahat, G., and Hazan, R. Y. (2001). Candidate selection methods: an analytical framework. Party Politics 7, 297–322. doi: 10.1177/1354068801007003003

Ritchie, J., and Lewis, J. (2003). Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Scarrow, S. (1999). Parties and the expansion of direct democracy: Who benefits? Party Politics 5, 341–362. doi: 10.1177/1354068899005003005

Seawright, J., and Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection techniques in case study research: a menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Polit. Res. Q. 61, 294–308. doi: 10.1177/1065912907313077

Seddone, A., Sandri, G., and Sozzi, F. (2020). “Primary elections for party leadership in Italy,” in Innovations, Reinvented Politics and Representative Democracy, eds A. Alexandre-Collier, A. Goujon, and G. Gourgues (Abingdon: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9780429026300-5

Solarino, A. M., and Aguinis, H. (2021). Challenges and best-practice recommendations for designing and conducting interviews with elite informants. J. Manage. Stud. 58, 649–672. doi: 10.1111/joms.12620

Wauters, B. (2014). Democratising party leadership selection in belgium: motivations and decision makers. Political Stud. 62, 61–80. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12002

Wauters, B., and Kern, A. (2020). Does it pay off? The effects of party leadership elections on parties' trustworthiness and appeal to voters. Political Stud. 69, 881–899. doi: 10.1177/0032321720932064

Wauters, B., Thijssen, P., and Erkel, P. (2020). Preference voting in the low countries. Political Low Countr. 3, 77–106. doi: 10.5553/PLC/258999292020002001004

Wolkenstein, F. (2016). A deliberative model of intra-party democracy. J. Political Philos. 24, 297–320. doi: 10.1111/jopp.12064

Appendix

Appendix 1: List of interviewees

Appendix 2: Codebook used to categorize nodes in NVivo

Keywords: parties leadership selection, intra-party democratization, steering process, elite interviews, Belgium, last person standing, political parties

Citation: Luypaert J, Lingier L, Bouteca N, Vandeleene A and Wauters B (2022) How many captains for a ship on electoral drift? Limiting the number of leadership candidates in the Flemish Christian-democratic party (CD&V). Front. Polit. Sci. 4:1068207. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.1068207

Received: 12 October 2022; Accepted: 05 December 2022;

Published: 20 December 2022.

Edited by:

Niklas Bolin, Mid Sweden University, SwedenReviewed by:

Vesa Koskimaa, Tampere University, FinlandSergiu Miscoiu, Babeş-Bolyai University, Romania

Copyright © 2022 Luypaert, Lingier, Bouteca, Vandeleene and Wauters. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jasmien Luypaert,  amFzbWllbi5sdXlwYWVydEBVR2VudC5iZQ==

amFzbWllbi5sdXlwYWVydEBVR2VudC5iZQ==

Jasmien Luypaert

Jasmien Luypaert Leen Lingier

Leen Lingier Nicolas Bouteca

Nicolas Bouteca Audrey Vandeleene

Audrey Vandeleene Bram Wauters

Bram Wauters